Abstract

Background

The purpose of this study was to test the hypothesis that periodontal pathogens associated with aggressive periodontitis persist in extracrevicular locations following scaling and root planing, systemic antibiotics, and anti-microbial rinses.

Methods

Eighteen aggressive periodontitis patients received a clinical exam during which samples of subgingival plaque and buccal epithelial cells were obtained. Treatment consisted of full-mouth root planing, systemic antibiotics, and chlorhexidine rinses. Clinical measurements were repeated along with sampling at 3 and 6 months. Quantitative PCR determined the number of plaque Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, Prevotella intermedia, Porphymonas gingivalis, Tannerella forsythensis, and Treponema denticola. Fluorescence in situ hybridization and confocal microscopy determined the extent of intracellular invasion in epithelial cells.

Results

Clinical measurements significantly improved following treatment. All bacterial species except P. gingivalis were significantly reduced in plaque from baseline to 3 months. However, all species showed a trend to repopulate between 3 and 6 months. This increase was statistically significant for log T. denticola counts. All species were detected intracellularly. The percentage of cells infected intracellularly was not affected by therapy.

Conclusions

The 6-month increasing trend in levels of plaque bacteria suggests that subgingival re-colonization was occurring. Since the presence of these species within epithelial cells was not altered after treatment, it is plausible that re-colonization may occur from the oral mucosa. Interestingly, systemic antibiotics and topical chlorhexidine did not reduce the percentage of invaded epithelial cells. These data support the hypothesis that extracrevicular reservoirs of bacteria exist, which might contribute to recurrent or refractory disease in some patients.

Keywords: intracellular bacteria, aggressive periodontitis, extracrevicular reservoir, antibiotic, Treponema denticola

Introduction

Periodontitis is a condition that is characterized by inflammation of the supporting tissues of the tooth. Certain bacterial species have been shown to be the main etiologic factors in the initiation and the progression of periodontal disease. 1,2 These organisms include the Gram negative anaerobes Porphymonas gingivalis, Prevotella intermedia, Treponema denticola and Tannerella forsythensis, and a facultative anaerobe Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans. 3,4 These bacteria are able to produce virulence factors that act locally within the sulcus, and result in tissue destruction. Examples of virulence factors include proteolytic enzymes produced by P. gingivalis, leukotoxins produced by A. actinomycetemcomitans, and a cysteine protease produced by T. forsythensis. 5-7 The presence of these bacteria in the gingival sulcus has been strongly associated with the diagnosis of progressive periodontal disease.

Previous studies have shown that some periodontal pathogens are able to invade oral epithelial cells. 8-12 The ability of bacteria to invade host cells and evade treatment may constitute another virulence factor. P. gingivalis has shown the ability to invade human gingival fibroblasts in cell culture while P. gingivalis, A. actinomycetemcomitans, and T. forsythensis have all demonstrated the ability to invade human oral epithelial cells in cell culture. 11, 13 A recent series of studies has reported the presence of A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis, T. forsythensis, P. intermedia, and T. denticola in buccal epithelial cells in vivo. 5, 14-16

Individual subjects vary with regard to the extent of bacterial invasion of epithelial cells. It has been previously hypothesized that epithelial invasion may serve as a mechanism for pathogenic bacteria to evade traditional therapy. 14-16 Eick and Pfister reported that epithelial invasion might allow bacteria to withstand systemic antibiotic therapy. 17 This is important because invasion of epithelial cells by periodontal pathogens may constitute an intracellular reservoir of bacteria in some individuals, and may lead to re-colonization of the periodontal pocket after treatment.

Standard non-surgical treatment for periodontal disease typically involves scaling and root planing that diminishes plaque and calculus deposits from the roots, and alters the microbial composition in the sulcus. 18, 19 However, standard non-surgical therapy alone does not completely eliminate certain subgingival periodontal pathogens. 20 Clinical measurements of pocket depth, attachment loss, and gingival indices do not respond as favorably after standard non-surgical therapy in certain subsets of patients. Individuals who do not show reversal of attachment loss may exhibit progressive disease or recurrence shortly after treatment. Many of these patients fall into the diagnostic categories of early onset or aggressive periodontitis. 20-22

Aggressive periodontitis is generally found in younger patients who are otherwise systemically healthy. A recent study found a prevalence of aggressive periodontitis to be 5.9% among young adult military recruits. 23 These patients experience episodic destruction of the attachment apparatus caused by a distinct subset of pathogenic bacteria. 24, 25 Subjects with aggressive periodontitis may exhibit an immunologic deficiency that can potentiate the disease process via defective polymorphonuclear leukocytes or monocytes. Aggressive periodontitis tends to progress rapidly as compared to chronic periodontitis. 26 A familial tendency and possible inherited component have been noted among aggressive periodontitis patients. 27, 28

Treatment of aggressive periodontitis frequently involves scaling and root planing and the use of systemic antibiotics. Antibiotic regimens have been used to improve the prognosis when used in conjunction with non-surgical therapy. 29 Antibiotics may enhance gains in attachment level and alter the subgingival bacterial profiles. 30 Full mouth scaling and root planing, systemic amoxicillin and metronidazole, and anti-microbial rinses have been advocated for patients with aggressive periodontitis. 31, 32

Given the rapid rate of progression and the high risk for recurrence among aggressive periodontitis patients, it is important to know whether the stringent protocols used to treat these patients have any effect in reducing the prevalence of intracellular bacteria as potential reservoir sites. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to test the hypothesis that periodontal pathogens associated with aggressive periodontitis could persist in extracrevicular locations following scaling and root planing, systemic antibiotics, and anti-microbial rinses.

Materials and Methods

Eighteen patients ranging in age from age 16 to 67 years with a median of 36 years (11 male and 7 female; 8 current smokers) were recruited from the Advanced Education Program in Periodontology clinic at the University of Minnesota School of Dentistry. This clinic sees a high proportion of patients from underserved populations, thus the patients recruited for this study may have presented for treatment at an older age compared to populations that routinely seek dental care. All participants exhibited clinical criteria consistent with a diagnosis of aggressive periodontitis as defined by the 1999 International Workshop for a Classification of Periodontal Diseases and Conditions. 21 One subject (age 67) had previously been diagnosed with aggressive periodontitis and treated years previously. This subject subsequently showed recurrence of aggressive periodontitis, including rapid loss of attachment, and was included in the study. Subjects were excluded if they were immunocompromised, had received antibiotic treatment within 6 months of baseline, required antibiotic prophylactic premedication, or were allergic to both amoxicillin and metronidazole. Participants were asked to read and sign a consent form that explained the risks and benefits of the study in compliance with the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board/Human Subjects Committee.

Buccal epithelial cells were collected using a cytological brush. 14 Subgingival plaque was collected with a sterile curette after the supragingival plaque had been removed. The sampled sites were selected based on radiographic evidence of the four deepest bony defects prior to the baseline exam. Plaque samples for each patient were pooled for each time point and stored in 1 ml of phosphate buffered saline. The buccal epithelial cells collected from the cytological brushes were also stored in phosphate buffered saline. All plaque and buccal cells were frozen after collection at −80° C.

Microbiological sampling and clinical measurements were performed at baseline, 3 months, and 6 months. A single calibrated examiner using a UNC #15 periodontal probe performed all clinical measurements. Measurements included bleeding on probing, probing depth, and clinical attachment loss at six sites per tooth. The clinical data was analyzed for both the four plaque sampled sites and for the whole mouth.

Treatment included full mouth scaling and root planing performed over two appointments, scheduled within 3 days. Patients were provided with systemic antibiotics and a prescription mouth rinse at the end of the second appointment. The antimicrobial regimen included 500 mg of amoxicillin and 250 mg of metronidazole taken three times daily for seven days and 0.12% chlorhexidine oral rinse used twice daily for 30 days. Oral hygiene instructions and aids were given during instrumentation appointments.

PCR and Confocal Microscopy

Microbial DNA for each patient time point was extracted from the pooled subgingival plaque using Masterpure tissue kits *. Total DNA was quantified with Picogreen ™ Quantitation kits †. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) assays were run for T. forsythensis, A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis, P. intermedia, and T. denticola using methods previously described. 15, 16, 33 Briefly, species specific 16S RNA primers with a manufacturer designed Z tail on the 5′ end were used for amplification. This Z tail also constitutes the 3′ end of a universal primer containing a quenched fluorescein molecule. As the reaction proceeded and complement strands to the universal primer Z tail were extended, fluorescein was forced away from the quencher molecule. The final amount of fluorescence was proportional to the original amount of microbial DNA in the sample. The amount of fluorescence was then compared to a standard curve containing known quantities of species-specific DNA, to quantitate the number of bacteria present. All amplification reactions were confirmed in agarose gels.

Epithelial cells were tested for intracellular invasion through the use of fluorescence in situ hybridization and confocal microscopy as previously described. 15 Briefly, custom-ordered fluorescent probes for species-specific sequences of bacterial 16S rRNA were obtained ‡ and hybridized with buccal epithelial cells obtained from the study subjects. A red fluorescent universal probe and a green fluorescent species-specific conjugate for either T. forsythensis, A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis, P. intermedia, or T. denticola were used in pairs. Red and green conjugates of the complement to the universal probe were used as a negative control.

Confocal microscopy was used to visualize the epithelial cells in order to determine whether labeled bacteria were present intracellularly. A 10X objective was used to count the number of invaded cells and a 60X oil immersion objective was used to confirm that the bacteria were located intracellularly. Three fields were analyzed per slide at 10X magnification. Buccal epithelial cells were counted in stored images of those fields, as were the number of cells positive for each species-specific probe. The percentage of invasion was determined by dividing the number of buccal epithelial cells containing a particular species of bacteria by the total number of buccal epithelial cells.

Statistics

All clinical data was analyzed for both all sites and for the four sampled plaque sites. Clinical and microbial measurements were compared across time points using one-way repeated measures ANOVA, followed by the Student-Newman-Keuls test (alpha = 0.05). For each time point, one-way repeated measures ANOVA and Duncan's test were used to compare the relative prevalence of the different species of bacteria.

Results

All eighteen subjects included in the analysis successfully completed the treatment and recall schedule. One individual originally enrolled in the study was not able to adhere to the recall schedule and therefore was not included in the analysis. One patient was allergic to penicillin and therefore received only metronidazole. Eight study participants were active smokers while the remaining subjects were either non-smokers or former smokers.

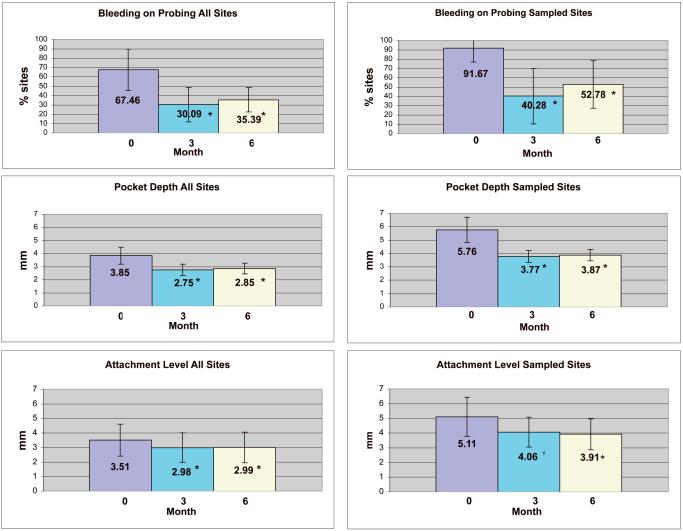

The mean probing depth was significantly reduced from baseline at both 3 month and 6 month evaluations both for all sites and the subset of sites sampled for subgingival plaque (p <0.05). The mean probing depth was reduced from 3.85 mm to 2.75 mm for all sites at 3 months and from 5.76 mm to 3.77 mm for the sampled sites. From baseline to 6 months pocket depth was reduced from 3.85 mm to 2.85 mm for all sites and from 5.76 mm to 3.87 mm for the sampled sites (Fig 1).

Figure 1.

Clinical measurements for baseline, 3 months, and 6 months for all sites and for the four plaque sampled sites. Mean values are indicated by the top of each bar. The error bars denote standard deviations. Asterisks ( * ) denote a significant difference from baseline at alpha = 0.05. (p <0.001, for all measurments).

Bleeding on probing was significantly reduced from baseline at both 3 month and 6 month evaluation both for all sites and sampled sites (p<0.05). The mean bleeding on probing percentage for all sites was reduced by 37% at 3 months and 52% for the sampled sites. At 6 months the mean bleeding on probing percentage for all sites was reduced by 32% and by 39% for the sampled sites (Fig. 1).

Attachment level gains were significant both for all sites and for sampled sites at 3 and 6 months (p<0.05). Mean clinical attachment level improved from 3.51 mm at baseline to 2.98 mm for all sites at 3 months and 5.11 mm to 4.06 mm for the sampled sites. At 6 months the improved mean attachment level remained stable as 2.99 mm for all sites while the sampled sites improved to 3.91mm (Fig 1).

Microbiological Results

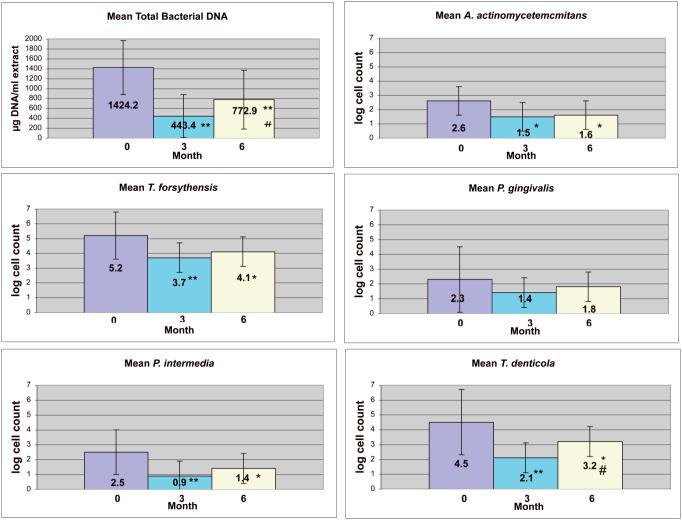

Total bacterial DNA and all individual species of bacteria were significantly reduced from baseline to 3 months in the subgingival plaque, with the exception of P. gingivalis. Total bacterial DNA and all of the individual species showed a trend to repopulate from 3 months to 6 months. This increase was statistically significant for total bacterial DNA (p<0.05) and log T. denticola counts (B= 4.5±1.9, 3M=2.1±1.7, 6M=3.2±2.2; p<0.0003, expressed as mean log count + standard deviation). T. forsythensis (B=5.2± 1.6, 3M= 3.7±1.1, 6M= 4.1±1.6) was the most prevalent bacteria at all time points. P. gingivalis (B=2.3±1.9, 3M=1.4±2.0, 6M=1.8±2.2) was the least prevalent bacteria at baseline. P. intermedia (B=2.5± 1.9, 3M=0.9±0.6, 6M=1.4±1.5) was the least prevalent at both 3 and 6 months (Fig 2).

Figure 2.

Analyses of subgingival plaque at baseline, 3 months, and 6 months. Total plaque DNA (a proxy for total bacteria) was expressed as μg/ml of DNA extract. Subgingival bacterial prevalence for each species are given as the log of the bacterial cell count per μg of DNA. Mean values are indicated by the top of each bar. Error bars represent standard deviations. The error bars denote standard deviations. Asterisks denote a significant difference from baseline at alpha = 0.05 (* p, 0.05; **p <0.001). # indicates a significant difference between 3 months and 6 months at alpha = 0.05 (p <0.05).

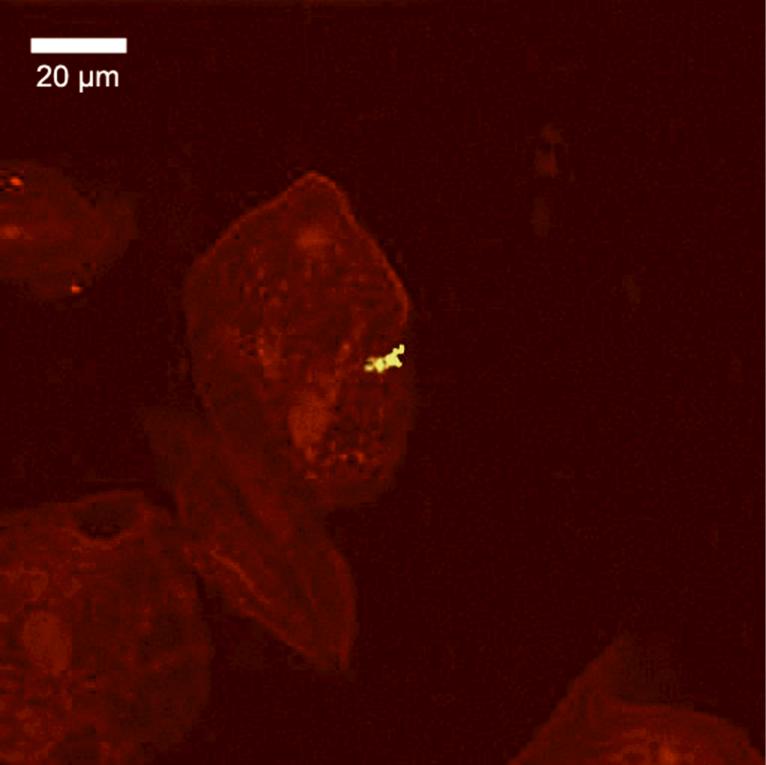

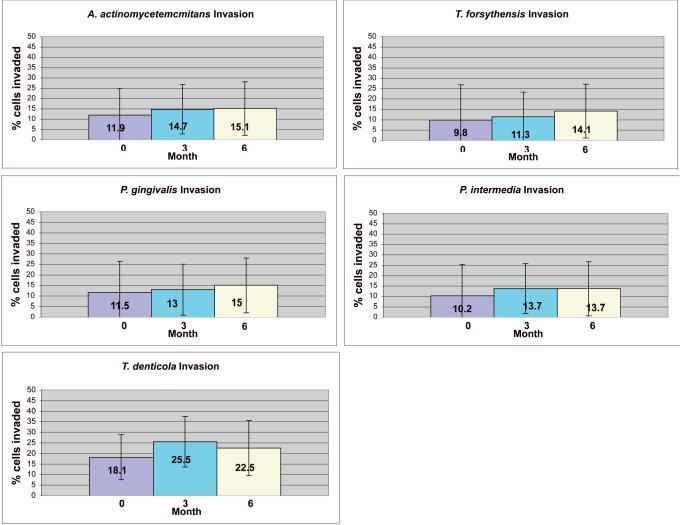

A representative confocal image of invaded cells is provided in Fig. 3. The mean percent of buccal cells invaded by any species, as detected by the universal bacterial probe, was 90% ± 5 (not shown). All target periodontal pathogens were found intracellularly with a mean prevalence ranging from 9.8% ± 10 of epithelial cells for T. forsythensis at baseline to 25.5% +±13.1 for T. denticola at 6 months. The prevalence of intracellular T. denticola was significantly higher than all of the other species at every time point. There were no significant differences in the percentage of cells invaded at any of the time points. The percentage of invasion was not significantly affected by therapy, although there was an insignificant trend for a slightly higher percentage of invasion for all species at 3 and 6 months compared to baseline (Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

A single z-section of a confocal microscope image, showing a buccal epithelial cell invaded by T. denticola. The yellow color results from positive signals from both the red-labeled universal probe for all bacteria, and the green-labeled species-specific probe for T. denticola. The distinctive spirochete morphology was clearly visible through the microscope, but is less apparent in this image due to loss of resolution with the 512 × 512 pixel CCD sensor.

Figure 4.

Percentage of buccal epithelial cells sampled showing bacterial invasion. The values given in the table are the percentage of epithelial cells showing intracellular invasion by each species, averaged over three fields. Mean values are indicated by the top of each bar. Error bars represent standard deviations. Error bars represent standard deviations. There were no significant differences.

Discussion

It has been previously established that certain species of bacteria are the main etiologic factor in periodontal disease and that scaling and root planing is able to reduce the prevalence of these bacteria within the sulcus. 19, 20, 29 Antimicrobial therapies, including both systemic antibiotics and topical antimicrobials, have been used as adjuncts to scaling and root planing. Enhanced gains in clinical attachment level, reduction in probing depth, and decreased bleeding on probing following scaling and root planing have been reported when using adjunctive antimicrobials. 30-32, 34-38

The present study found similar improvements in clinical outcomes to those previously reported. Full mouth mean clinical attachment levels for both all sites and for the four sampled sites significantly improved at 3 and 6 months following treatment. Probing depths and bleeding on probing were also significantly reduced at 3 and 6 months for all sites and for the four sampled sites. All of the clinical measurements showed a slight rebound toward baseline values from 3 to 6 months, although none of these were statistically significant. In contrast, clinical attachment levels at the four sampled sites continued to improve from 3 to 6 months.

Previous studies have shown that scaling and root planing along with systemic amoxicillin and metronidazole suppresses A. actinomycetemcomitans, T. forsythensis, P. gingivalis, and P. intermedia below levels of detection in most patients, as determined by microbial culture. 35-37 For example, Feres et al. 38, 2001 reported T. forsythensis, P. gingivalis, and T. denticola counts were significantly reduced for up to one year after the use of amoxicillin or metronidazole. Ehmke et al. 30 was able to suppress levels of A. actinomycetemcomitans detection in a significant number of patients for up to 18 months. In the present study, total bacteria and individual species were significantly reduced in plaque from baseline to 3 months, with the exception of P. gingivalis. Complete suppression was not observed, probably due to the differences in sensitivity of PCR when compared to bacterial culture 39.

Plaque T. denticola had significantly increased at 6 months, when compared to the reduction obtained at 3 months. There was also a non-significant trend for all other plaque bacterial species levels to increase at 6 months, when compared to the 3 month levels. This rebound is consistent with other full mouth disinfection studies that showed short-term reductions in the number of subgingival pathogenic bacteria.30, 32, 35, 36, 38, 40 It should be noted that these studies employed different methods for bacterial quantification, had varying time points for collection, and tested different strains of bacteria.

Although full-mouth disinfection may improve the clinical and bacterial parameters, it may not prevent re-colonization to the sulcus from other sources. P. gingivalis was able to re-colonize subgingival sites in which it had been previously suppressed shortly after active periodontal treatment. 41 It also has been previously shown that there is rapid colonization by pathogenic bacteria in ‘pristine’ peri-implant sites. 42 The fact that ‘pristine’ implant sites become colonized, suggests that subgingival sites have the potential to become re-colonized from extracrevicular sources after treatment.

One of the potential sources for re-colonization might be intracellular bacteria that reside within epithelial cells. The ability of pathogenic bacteria to invade epithelial cells has been demonstrated previously. 5, 8, 9, 14-16 Furthermore, it has been recently demonstrated with confocal microscopy that individuals with periodontal disease have significantly greater numbers of intracellular bacteria in both crevicular and buccal epithelium when compared to healthy controls. 43 The ability of the bacteria to remain in this extracrevicular reservoir despite treatment could allow for re-colonization of the sulcus and recurrence of disease.

To our knowledge, this is the first study of the impact of a comprehensive periodontal treatment protocol, including scaling and root planing, antimicrobial rinses, and systemic antibiotics, on the prevalence of extracrevicular intracellular pathogens. Although treatment resulted in improved clinical parameters and decreased plaque bacteria, extracrevicular epithelial cell invasion by bacteria was not affected by the antimicrobial protocol used to treat aggressive periodontitis. We found that the percentages of invaded buccal epithelial cells did not change with antimicrobial therapy, which suggests that intracellular bacteria may be protected from systemic antimicrobial therapy. A recent tissue culture study compared antibiotics that are capable of entering eukaryotic cells, including clindamycin, doxycycline, and moxifloxacin. Metronidazole also was used. The results suggested that while intracellular A. actinomycetemcomitans may be susceptible to very high concentrations of antibiotics, intracellular P. gingivalis was resistant. 17 Such in vitro models may not simulate the availability of systemically administered antibiotics within mucosal cells in-vivo. This may explain why no effect was seen on intracellular A. actinomycetemcomitans (or any other species) in this clinical study.

Tissue penetration by amoxicillin and metronidazole has not been extensively studied in periodontal infections, and it is possible that the combination of amoxicillin and metronidazole may not be effective in treating intracellular bacterial infections. An antibiotic with superior tissue penetration, such as azithromycin 44, may have more benefit in treating intracellular bacteria. However, methods for evaluating tissue penetration do not address the question of whether antibiotics actually are taken into epithelial cells. Further research is necessary to determine the ability of antibiotics alone or in combination to act effectively against intracellular bacteria at concentrations found in patient tissues.

Recolonization of the sulcus could occur from a number of different sources including extracrevicular sites or other infected crevicular sites. 45 Bacterial genotyping studies also are consistent with transmission of periodontal pathogens from one cohabitant to another. 46 Since there is presently no way to track the course of individual bacteria within patients, the origins of bacteria in the sulcus cannot be determined definitively. The increase in sulcular plaque T. denticola from 3 months to 6 months combined with the unchanged high levels of intracellular T. denticola in buccal mucosa epithelial cells in this study suggests that re-colonization might have occurred from that source. Re-colonization from any extracrevicular reservoir within the oral cavity may ultimately lead to recurrence of periodontal disease despite treatment. Consequently, further research is needed to determine appropriate strategies for reducing numbers of intracellular bacteria throughout the mouth, and not just those in the gingival crevice or pocket.

Acknowledgments

This investigation was supported by NIH grant DE 14214 (Dr. Joel Rudney, Principal Investigator). The authors have no financial relationships related to any product used in this study. The authors wish to thank Drs. Massimo Costalonga, Bryan Michalowicz, and Larry Wolff of the University of Minnesota School of Dentistry, Division of Periodontology, for helpful comments.

Supported by NIH Grant DE 14214

Footnotes

Summary: Despite improved clinical measurements and a decrease in plaque bacteria, treatment of aggressive periodontitis does not affect the prevalence of intracellular bacterial pathogens in extracrevicular mucosa.

Epicentre, Madison, WI

Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR

Oligos Etc., Wilsonville, OR

References

- 1.Haffajee AD, Socransky SS. Microbial etiological agents of destructive periodontal diseases. Periodontol 2000. 1994;5:78–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1994.tb00020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolff LF, Aeppli DM, Pihlstrom B, et al. Natural distribution of 5 bacteria associated with periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 1993;20:699–706. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1993.tb00694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Norskov-Lauritsen N, Kilian M. Reclassification of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Haemophilus aphrophilus, Haemophilus paraphrophilus and Haemophilus segnis as Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans gen. nov., comb. nov., Aggregatibacter aphrophilus comb. nov. and Aggregatibacter segnis comb. nov., and emended description of Aggregatibacter aphrophilus to include V factor-dependent and V factor-independent isolates. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2006;56:2135–2146. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64207-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sakamoto M, Suzuki M, Umeda M, et al. Reclassification of Bacteroides forsythus (Tanner et al. 1986) as Tannerella forsythensis corrig., gen. nov., comb. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2002;52:841–849. doi: 10.1099/00207713-52-3-841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andrian E, Grenier D, Rouabhia M. In vitro models of tissue penetration and destruction by Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infect Immun. 2004;72:4689–4698. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.8.4689-4698.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fives-Taylor PM, Meyer DH, Mintz KP, et al. Virulence factors of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Periodontol 2000. 1999;20:136–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1999.tb00161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tan KS, Song KP, Ong G. Bacteroides forsythus prtH genotype in periodontitis patients: occurrence and association with periodontal disease. J Periodontal Res. 2001;36:398–403. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0765.2001.360608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saglie R, Newman MG, Carranza FA, et al. Bacterial invasion of gingiva in advanced periodontitis in humans. J Periodontol. 1982;53:217–222. doi: 10.1902/jop.1982.53.4.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saglie FR, Carranza FA, Jr, Newman MG, et al. Identification of tissueinvading bacteria in human periodontal disease. J Periodontal Res. 1982;17:452–455. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1982.tb02024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christersson LA, Albini B, Zambon JJ, et al. Tissue localization of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in human periodontitis. I. Light, immunofluorescence and electron microscopic studies. J Periodontol. 1987;58:529–539. doi: 10.1902/jop.1987.58.8.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meyer DH, Lippmann JE, Fives-Taylor PM. Invasion of epithelial cells by Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans: a dynamic, multistep process. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2988–2997. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.2988-2997.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duncan MJ, Nakao S, Skobe Z, et al. Interactions of Porphyromonas gingivalis with epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2260–2265. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.2260-2265.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amornchat C, Rassameemasmaung S, Sripairojthikoon W, et al. Invasion of Porphyromonas gingivalis into human gingival fibroblasts in vitro. J Int Acad Periodontol. 2003;5:98–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rudney JD, Chen R, Sedgewick GJ. Intracellular Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and Porphyromonas gingivalis in buccal epithelial cells collected from human subjects. Infect Immun. 2001;69:2700–2707. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.4.2700-2707.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rudney JD, Chen R, Sedgewick GJ. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Porphyromonas gingivalis, and Tannerella forsythensis are components of a polymicrobial intracellular flora within human buccal cells. J Dent Res. 2005;84:59–63. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rudney JD, Chen R, Zhang G. Streptococci dominate the diverse flora within buccal cells. J Dent Res. 2005;84:1165–1171. doi: 10.1177/154405910508401214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eick S, Pfister W. Efficacy of antibiotics against periodontopathogenic bacteria within epithelial cells: an in vitro study. J Periodontol. 2004;75:1327–1334. doi: 10.1902/jop.2004.75.10.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tagge DL, O'Leary TJ, El-Kafrawy AH. The clinical and histological response of periodontal pockets to root planing and oral hygiene. J Periodontol. 1975;46:527–533. doi: 10.1902/jop.1975.46.9.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hinrichs JE, Wolff LF, Pihlstrom BL, et al. Effects of scaling and root planing on subgingival microbial proportions standardized in terms of their naturally occurring distribution. J Periodontol. 1985;56:187–194. doi: 10.1902/jop.1985.56.4.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mombelli A, Schmid B, Rutar A, et al. Persistence patterns of Porphyromonas gingivalis, Prevotella intermedia/nigrescens, and Actinobacillus actinomyetemcomitans after mechanical therapy of periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 2000;71:14–21. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Armitage GC. Development of a classification system for periodontal diseases and conditions. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:1–6. doi: 10.1902/annals.1999.4.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tonetti MS, Mombelli A. Early-onset periodontitis. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:39–53. doi: 10.1902/annals.1999.4.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levin L, Baev V, Lev R, Stabholz A, et al. Aggressive periodontitis among young Israeli army personnel. J Periodontol. 2006;77:1392–1396. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee JW, Choi BK, Yoo YJ, et al. Distribution of periodontal pathogens in Korean aggressive periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2003;74:1329–1335. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.9.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takeuchi Y, Umeda M, Ishizuka M, et al. Prevalence of periodontopathic bacteria in aggressive periodontitis patients in a Japanese population. J Periodontol. 2003;74:1460–1469. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.10.1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garlet GP, Martins W, Jr, Ferreira BR, et al. Patterns of chemokines and chemokine receptors expression in different forms of human periodontal disease. J Periodontal Res. 2003;38:210–217. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0765.2003.02012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diehl SR, Wu T, Michalowicz BS, Brooks CN, et al. Quantitative measures of aggressive periodontitis show substantial heritability and consistency with traditional diagnoses. J Periodontol. 2005;76:279–288. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.2.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lopez NJ. Clinical, laboratory, and immunological studies of a family with a high prevalence of generalized prepubertal and juvenile periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1992;63:457–468. doi: 10.1902/jop.1992.63.5.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haffajee AD, Socransky SS, Gunsolley JC. Systemic anti-infective periodontal therapy. A systematic review. Ann Periodontol. 2003;8:115–181. doi: 10.1902/annals.2003.8.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ehmke B, Moter A, Beikler T, et al. Adjunctive antimicrobial therapy of periodontitis: long-term effects on disease progression and oral colonization. J Periodontol. 2005;76:749–759. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.5.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Winkelhoff AJ, Tijhof CJ, de Graaff J. Microbiological and clinical results of metronidazole plus amoxicillin therapy in Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans-associated periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1992;63:52–57. doi: 10.1902/jop.1992.63.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Flemmig TF, Milian E, Karch H, et al. Differential clinical treatment outcome after systemic metronidazole and amoxicillin in patients harboring Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and/or Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Clin Periodontol. 1998 May;25:380–387. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1998.tb02459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rudney JD, Chen R, Pan Y. Endpoint quantitative PCR assays for Bacteroides forsythus, Porphyromonas gingivalis, and Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. J Periodontal Res. 2003;38:465–470. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0765.2003.00670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guerrero A, Griffiths GS, Nibali L, et al. Adjunctive benefits of systemic amoxicillin and metronidazole in non-surgical treatment of generalized aggressive periodontitis: a randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32:1096–1107. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Winkel EG, van Winkelhoff AJ, van der Velden U. Additional clinical and microbiological effects of amoxicillin and metronidazole after initial periodontal therapy. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25:857–864. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1998.tb02382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Winkel EG, Van Winkelhoff AJ, Timmerman MF, et al. Amoxicillin plus metronidazole in the treatment of adult periodontitis patients. A doubleblind placebo-controlled study. J Clin Periodontol. 2001;28:296–305. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2001.028004296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pavicic MJ, van Winkelhoff AJ, Douque NH, et al. Microbiological and clinical effects of metronidazole and amoxicillin in Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans-associated periodontitis. A 2-year evaluation. J Clin Periodontol. 1994;21:107–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1994.tb00287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feres M, Haffajee AD, Allard K, et al. Change in subgingival microbial profiles in adult periodontitis subjects receiving either systemically-administered amoxicillin or metronidazole. J Clin Periodontol. 2001;28:597–609. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2001.028007597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lau L, Sanz M, Herrera D, et al. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction versus culture: a comparison between two methods for the detection and quantification of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Porphyromonas gingivalis and Tannerella forsythensis in subgingival plaque samples. J Clin Periodontol. 2004;12:1061–1069. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2004.00616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bollen CM, Mongardini C, Papaioannou W, et al. The effect of a one-stage full-mouth disinfection on different intra-oral niches. Clinical and microbiological observations. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25:56–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1998.tb02364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fujise O, Miura M, Hamachi, et al. Risk of Porphyromonas gingivalis recolonization during the early period of periodontal maintenance in initially severe periodontitis sites. J Periodontol. 2006;77:1333–1339. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Quirynen M, Vogels R, Pauwels M, et al. Initial subgingival colonization of ‘pristine’ pockets. J Dent Res. 2005;84:340–344. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Colombo AV, da Silva CM, Haffajee A, et al. Identification of intracellular oral species within human crevicular epithelial cells from subjects with chronic periodontitis by fluorescence in situ hybridization. J Periodontal Res. 2007;42:236–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2006.00938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gomi K, Yashima A, Nagano T, et al. Effects of full-mouth scaling and root planing in conjunction with systemically administered azithromycin. J. Periodontol. 2007;78(3):422–429. doi: 10.1902/jop.2007.060247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Christersson LA, Slots J, Zambon JJ, et al. Transmission and colonization of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in localized juvenile periodontitis patients. J Periodontol. 1985;56(3):127–131. doi: 10.1902/jop.1985.56.3.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Asikainen S, Chen C, Slots J. Likelihood of transmitting Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and Porphyromonas gingivalis in families with periodontitis. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1996;11(6):387–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1996.tb00200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]