Abstract

We present the design, guided by theory to eighth order, and the first evaluation of a Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance (FT-ICR) compensated trap. The purpose of the new trap is to reduce effects of the non-linear components of the trapping electric field; those non-liner components introduce variations in the cyclotron frequency of an ion based on its spatial position (its cyclotron and trapping mode amplitudes). This frequency spread leads to decreased mass resolving power and signal-to-noise. The reduction of the spread of cyclotron frequencies, as explicitly modeled in theory, serves as the basis for our design. The compensated trap shows improved signal-to-noise and at least a three-fold increase in mass resolving power compared to the uncompensated trap at the same trapping voltage. Resolving powers (FWHH) as high as 1.7 × 107 for the [M + H]+ of vasopressin at m/z 1084.5 in a 7.0-Tesla induction can be obtained when using trap compensation.

Introduction

Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry (FT-ICR MS) offers the highest mass resolving power and mass accuracy, permitting determination of elemental compositions of unknowns and more certain identification of peptides in proteomics [1, 2]. Despite its high performance, the highest performance capabilities of FT-ICR MS are still limited by trap design.

Various designs and approaches to trap compensation can be categorized according to their trapping electric-field shape, electrode design, and design goal [3]. The two most common electric-field shapes correspond to the particle-in-a-box and the 3D quadrupolar potential well. The particle-in-a-box configuration minimizes Er/r and can be approximated by electrical [4–7] or mechanical [8] means. This configuration, however, inevitably introduces a strong trapping electric field non-linearity at the edges of the trap (the extremes of the ion z-mode oscillation). The quadrupolar potential well, on the other hand, aims at constant Er/r and can be produced by using accurate electrode shapes, such as those of hyperbolic traps [9–11]. An instrument with a hyperbolic trap, however, suffers at least from inefficient use of the magnet bore and a relatively inaccessible trap interior. The quadrupolar potential well can also be approximated in a cylindrical or cubic trap by using simple electrode shapes and by optimizing the aspect ratio [12, 13] or by segmenting the electrodes [12] [14–18]. Compensating a cubic trap by using simple electrode segmentation is was achieved previously and is not difficult [19]. A third design goal, which we use here, is to seek a constant frequency surface over a range amplitudes for all oscillation modes [20].

In this paper, we describe the design and preliminary evaluation of a cylindrical trap electrically compensated in theory to eighth order. We chose to conduct the evaluation using MALDI as it tends to produce singly charged ions, allowing us to work at high m/z if desired, an advantage because working at high m/z provides a stringent test for FT-ICR performance. MALDI is a pulsed ionization method and it offers the advantage of repeated, in-depth analysis of a sample without waste. MALDI also does not constrain the time scale in which the FT-ICR experiment must be completed.

Tolmachev [21] recently announced a compensated cylindrical trap design that is outwardly similar to that presented here, but it differs in the goal used to motivate the design. Tolmachev sought to reduce the variation in Er/r over a range of ion positions; his and our goals would produce, in the limit, the same outcome of a quadrupolar potential. For practical application, however, the outcomes are necessarily approximate, and different goals lead to different outcomes as can be seen by the difference between Tolmachev’s design and ours. The approach used here is distinguished by the feature that it more correctly reflects the desired outcome by specifying properties for the modeled cyclotron frequency explicitly rather than specifying a property of the electric field without evaluating the connection of that property to the cyclotron frequency in the approximate case.

Experimental

The analytes, [Arg]8-Vasopressin and cytochrome C, were mixed with 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid in ratios of 1:1500 to 1:5000, prior to spotting on a standard 192-spot stainless steel sample plate. All materials were obtained from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Spectra were acquired with a 7.0-Tesla IonSpec ProMALDI FTMS (Lake Forest, CA), equipped with an external hexapole for accumulation of ions from multiple laser shots and collisionally cooling them. The ions were subsequently transferred to the custom-built ICR trap (Figure 1) via a quadrupolar ion-transfer guide. The trap was switched between operating in the compensated and uncompensated modes by changing the voltages supplied to the electrodes that generate the compensating field. In the compensated mode, the voltages supplied to the three compensation electrodes are nonzero values determined by tuning, whereas in the uncompensated mode the voltages are set to zero potential. In the compensated mode, the same potential was applied to both the inner rings and end-cap electrodes, whereas in the uncompensated mode the inner rings were at a constant non-zero potential, and the end caps were at zero. The inner rings and end-cap electrodes discussed here have the same meaning as used elsewhere [22, 23], not to be confused with the compensation electrodes that were added to the modified trap. The trapping well was set to a nominal depth of either 0.4 or 1.0 V. The compensation electrodes and the inner rings of the modified trap were segmented and capacitively coupled to the excite plates to minimize axial ejection during excitation[24].

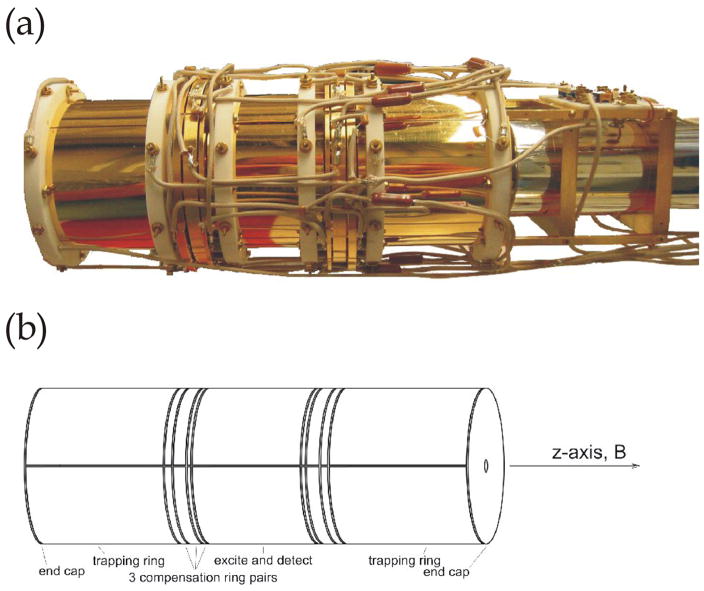

Figure 1.

(a) Photograph of compensated trap mounted on quadrupole ion guide (b) Diagram of compensated trap.

The z-mode amplitude distribution of an ion cloud was manipulated by collisionally cooling the ions with pulses of N2 gas, followed by z-mode re-excitation, driven by applying +35 volts to the entrance end-cap and −35 volts to the filament side end-cap; the duration of the end-cap pulse controlled the extent of re-excitation in the z-direction.

Digitized time domain signals of 2048 K and 1024 K data points were acquired in the narrowband mode for vasopressin and cytochrome C, respectively. The ADC rate was set at 10 kHz, which corresponded to an acquisition time of ~210 s or 105 s per detection event. Following acquisition, the data were imported into a Fortran program for the calculation of the complex FFT, magnitude mode frequency centroid, complex area, and mass resolving power.

The trap compensation design process relies on goals set for the explicit expression of the cyclotron frequency versus amplitudes of all of the single ion motion modes. The design degrees of freedom were defined by four gap positions that isolate three compensating electrode pairs, and three compensation voltages that are applied to the isolated electrode pairs. The trapping-electric potential for a closed cylindrical trap at an ion position was expressed by forcing the z-derivatives of the spherical harmonic expansion to eighth order of the potential to match the z-derivatives of the modified Bessel function series solution for the Laplace equation with Dirichlet boundary conditions. To get from the electric potential, expressed at a point, to a cyclotron frequency for a single ion, expressed at a set of mode amplitudes, the expression for the electric potential was used in the Hamiltonian for a single ion moving in uniform magnetic induction. The Hamiltonian, converted to a function of action-angle coordinates, was simplified to remove the angle coordinates by using a canonical transform computed by the Deprit perturbation series to third order. The derivatives with respect to the mode actions of the cyclotron frequency (itself the derivative of the simplified Hamiltonian with respect to the cyclotron mode action) were then computed as functions of the z-mode, magnetron-mode and the cyclotron-mode amplitudes. The cyclotron frequency as a function of z-mode and cyclotron-mode amplitudes gave a frequency surface. The design parameters of the trap, four gap positions and three voltages, were then systematically changed until the three cyclotron frequency derivatives were minimized, indicating that the frequency surface had become at the least locally “flat” with an approximate first-order, triple-frequency focus. The minimization made use of the root sum of squares (RSS) of the cyclotron frequency derivatives evaluated at 0.4, 0.0 and 0.6 for the cyclotron-mode, magnetron-mode, and z-mode amplitudes, respectively, all normalized to the trap inside radius.

In this context the design process produced many solutions; for each, the fourth, sixth, and eighth-order spherical harmonic contributions to the electric potential as originally expressed were effectively removed giving solutions that are compensated to eighth order in terms of the potential. From the many solutions, the design with gap positions greater or equal to 0.7 as normalized to the trap inside radius, minimum compensation voltages and the smallest possible electric field along the z-axis near the trapping plate apertures was selected. Details of the design process will be published later.

Results and Discussion

The compensated trap was constructed from 0.51 mm thick gold electroplated OFHC copper with gap sizes of 0.51 mm between the plates. The gap positions normalized to the inside radius of the trap (31.24 mm) as determined by theory, were 0.7000, 0.7660, 0.9437, and 1.0580 from the trap center in the z-direction. The positions of the gaps in the final trap were specified as 21.87, 23.93, 29.49 and 33.04 ± 0.03 mm. Theory indicates that small variations in the gap positions can be overcome by appropriate tuning of the compensation voltages. The thicknesses of the compensation electrodes were 1.55, 5.05, and 3.05 ± 0.03 mm for compensation ring one, two, and three, respectively. The theoretical compensation voltages were 9.608, −7.608, and 9.608 volts, applied to rings one, two, and three, affording a nominal well depth of one volt. The experimental compensation voltages were determined by tuning at m/z 1084.5 to be 8.412, −7.516, and 10.819 volts. The tuning process will be described more fully in a subsequent publication.

Discrepancies between theory and experiment arise because the manufacturing process cannot be executed in full accord with theory (i.e., imperfections occur in electrode thicknesses and spacings). Furthermore, theory does not account for the work functions of the metal surfaces within the trap. Starting from the theoretical voltages, the tuning process enabled us to find efficiently a set of compensation ring voltages that produced a nearly constant frequency surface for a range of cyclotron and z-mode amplitudes.

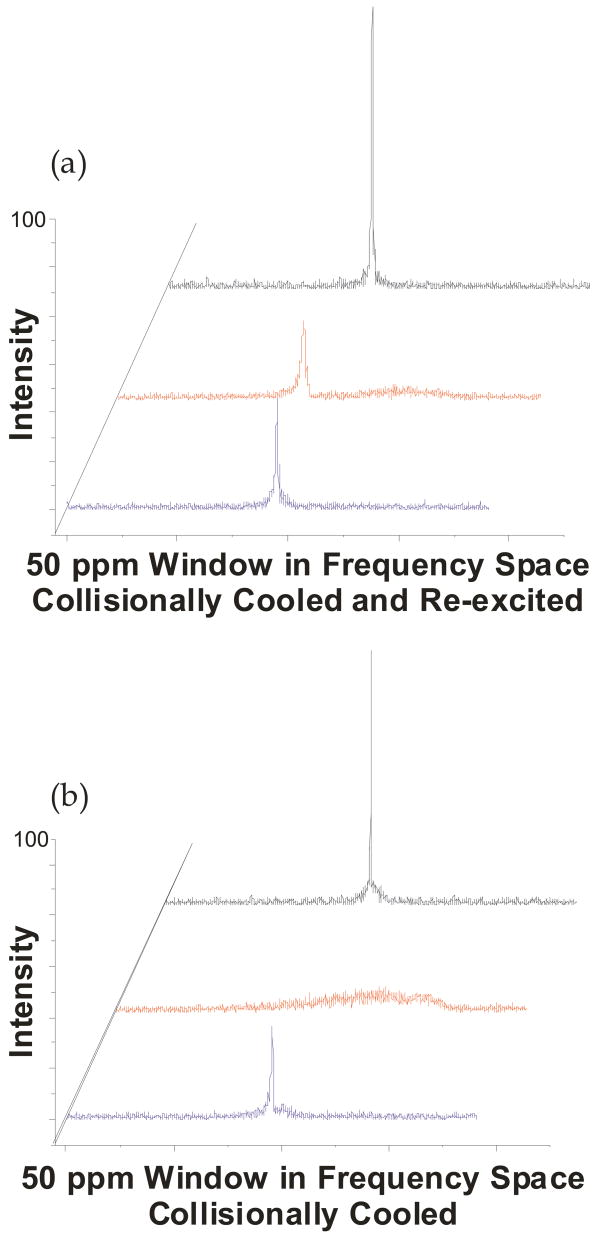

One set of mass spectra that illustrate the difference in performance between compensated and uncompensated modes (Figure 2a) are of an ion cloud that was collisionally cooled with a pulse of nitrogen gas, and its z-mode amplitude was re-excited by pulsing the trapping plates; we refer to the outcome as a “hot” cloud. The other spectra are of a collisionally cooled cloud (i.e., one without z-mode re-excitation) appropriately designated the “cool” cloud (Figure 2b). A collisionally cooled cloud without re-excitation was considered to have an average z-position closer to the center of the trap than one that had been excited by pulsing the endcaps.

Figure 2.

Comparison of (a) hot clouds and (b) cool clouds in the compensated mode at 1.0 volts (black) to the uncompensated mode at 1.0 volts (red) and 0.4 volts (blue). *The spectrum acquired in the uncompensated mode at 1.0V has ~7 times the number of ions as and the intensity scale is 20% of the other spectra shown here.

Out of an ensemble of spectra, those with similar complex areas were selected for comparison. Owing to the lack of shot-to-shot reproducibility of MALDI, the complex area was used as the best measure of the number of ions in the trap. That number for each spectrum, as determined by the complex area of the peak, was nearly the same, except for acquisition of the mass spectrum of a cool cloud in an uncompensated (1.0 V trap), which required a complex area approximately seven times greater than the other spectra in order for a spectral feature to be visible above the noise. The complex area is a measure of the initial amplitude of the time domain signal envelope attributable to the peak of interest and is proportional to the number of ions of a specific m/z in the trap.[25] The spectral intensities were normalized with respect to the peak complex areas to allow comparison of spectra as signal per ion.

At either trapping voltage and with either a hot or cool ion cloud, the compensated mode clearly produces improved mass resolving power and signal-to-noise ratio. The mass resolving power of the uncompensated mode with inner rings at 0.4 V approaches that of the compensated mode at a nominal well depth of 1.0 V, but because the well depth is cut by more than half, the capacity of the uncompensated trap is also reduced.

The maximum achievable mass resolving power in the compensated mode is at least three times that of the trap operated in the uncompensated mode, when both are run with nominal well depths of 1.0 V. Given that the non-linearities in the electric field are reduced by the effect of the compensation voltages, ions of the same m/z within a cloud that has different axial and radial mode amplitudes oscillate with nearly the same cyclotron frequency. Because the distribution of frequencies for a given m/z within the cloud becomes narrower, the mass resolving power increases. Resolving powers (FWHH) as high as 1.7 × 107 for vasopressin at m/z 1084.5 in a 7.0-Tesla magnetic induction have been observed in the compensated mode; this is the theoretical limit under these conditions when no spectral apodization is employed.

The ability of an ion cloud to phase lock depends on the frequency spread (Δf) across the cloud and the ion density within it [26]. Given that the compensation voltages reduce the nonlinearities in the electric field, thereby making Δf small, the number of ions required for phase locking in the compensated mode decreases. This means a smaller number of ions are required to produce a well-defined, detectable signal, affording a higher signal-to-noise ratio for an equivalent number of ions (outcome also illustrated by the spectra in Figure 2).

FT-ICR MS has difficulty detecting high m/z ions. As m/z increases, the magnet force decreases, leaving the ions more vulnerable to nonlinearities in the electric field. Clouds composed of high m/z ions are axially and radially diffuse compared to clouds of low m/z ions [27]. Therefore, higher m/z ions sample a larger volume of the trap than do low m/z ions, and consequently sample a greater extent of both electric and magnetic-induction inhomogeneity.

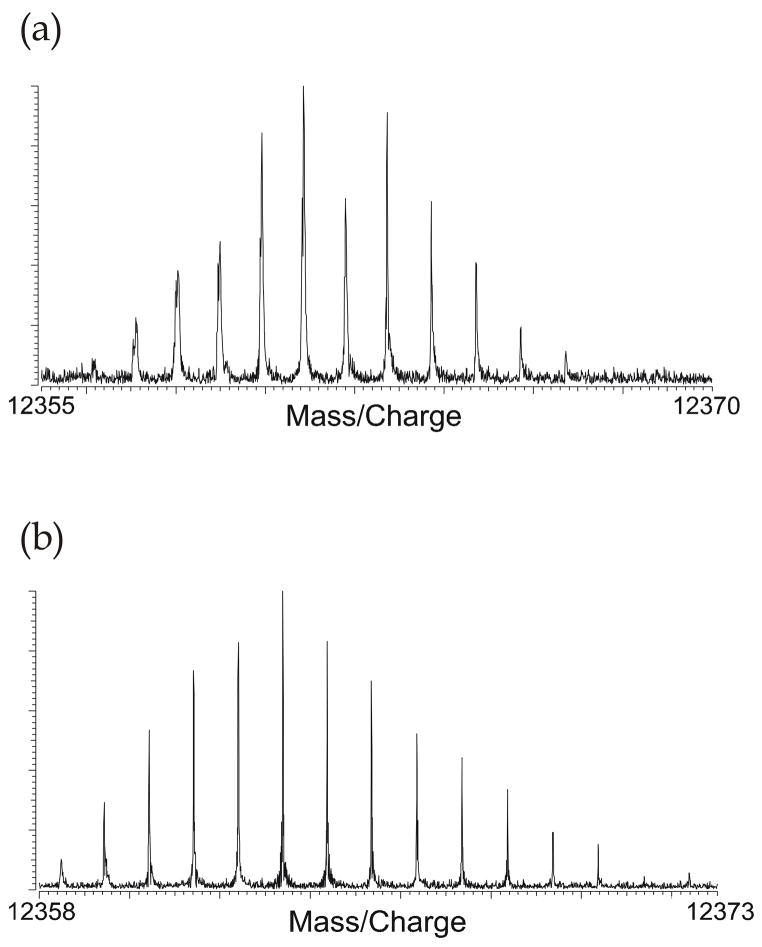

The mass spectra of cytochrome C in both the uncompensated and compensated modes (Figure 3) show that the mass resolving power in the compensated mode is nearly three times that of the uncompensated mode. (The difference in m/z assignment occurred because the instrument was not calibrated for the compensated mode.) Given the above considerations, we had expected the performance enhancement afforded by trap compensation to be greater for ions of higher m/z. This was not realized in these first experiments, indicating that the uncompensated mode is performing artificially well due to phase locking, that tuning of the compensation voltages should be further improved, or that magnetic induction inhomogeneities or other factors are operative, or possibly to a combination of these factors.

Figure 3.

Spectra of Cytochrome C in the (a) uncompensated mode and (b) compensated mode at 0.4 volts.

Conclusions

Electrical compensation produces a nearly flat frequency surface in an ICR trap, affording improved mass resolving power and signal-to-noise ratio for a given number of ions. As the electric field is made more nearly quadrupolar, the role of the imperfections in the magnetic induction may become more significant, requiring more frequent and precise shimming of those fields, as is done in NMR. This preliminary evaluation will be followed by future publications covering the design, tuning, and performance of the compensated trap, as well as the possible role of the magnetic induction inhomogeneities.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Centers for Research Resources of the NIH (Grant 2P41RR000954). The authors would also like to thank Robert McIver for his help in the construction and installation of the compensated trap.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Easterling ML, Mize TH, Amster IJ. Routine part-per-million mass accuracy for high-mass ions: space-charge effects in MALDI FT-ICR. Analytical Chemistry. 1999;71(3):624–632. doi: 10.1021/ac980690d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim S, Rodgers RP, Marshall AG. Truly “exact” mass: Elemental composition can be determined uniquely from molecular mass measurement at .apprx.0.1mDa accuracy for molecules up to .apprx.500Da. International Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 2006;251(2–3):260–265. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guan S, Marshall AG. International Journal of Mass Spectrometry and Ion Processes. 146/147. 1995. Ion traps for Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry: principles and design of geometric and electric configurations; pp. 261–96. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naito Y, Fujiwara M, Inoue M. Improvement of the electric field in the cylindrical trapped-ion cell. International Journal of Mass Spectrometry and Ion Processes. 1992;120(3):179–92. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vartanian VH, Hadjarab F, Laude DA. Open cell analog of the screened trapped-ion cell using compensation electrodes for Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry. International Journal of Mass Spectrometry and Ion Processes. 1995;151(23):175–87. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaiser NK, Bruce JE. Observation of Increased Ion Cyclotron Resonance Signal Duration through Electric Field Perturbations. Analytical Chemistry. 2005;77(18):5973–5981. doi: 10.1021/ac050606b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaiser NK, Bruce JE. Reduction of ion magnetron motion and space charge using radial electric field modulation. International Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 2007;265(2–3):271–280. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hunter RL, Sherman MG, McIver RT., Jr An elongated trapped-ion cell for ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry with a superconducting magnet. International Journal of Mass Spectrometry and Ion Physics. 1983;50(3):259–74. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Dyck RS, Jr, Schwinberg PB. Preliminary proton/electron mass ratio using a compensated quadring Penning trap. Physical Review Letters. 1981;47(6):395–8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Dyck RS, Jr, et al. High mass resolution with a new variable anharmonicity Penning trap. Applied Physics Letters. 1976;28(8):446–8. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rempel DL, et al. Parametric mode operation of a hyperbolic Penning trap for Fourier transform mass spectrometry. Analytical Chemistry. 1987;59(20):2527–32. doi: 10.1021/ac00147a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gabrielse G, MacKintosh FC. Cylindrical Penning traps with orthogonalized anharmonicity compensation. International Journal of Mass Spectrometry and Ion Processes. 1984;57(1):1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vartanian VH, Laude DA. Optimization of a fixed-volume open geometry trapped ion cell for Fourier transform ion cyclotron mass spectrometry. International Journal of Mass Spectrometry and Ion Processes. 1995;141(3):189–200. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knobeler M, Wanczek KP. Theoretical investigation of improved ion trapping in matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry: independence of ion initial velocity. International Journal of Mass Spectrometry and Ion Processes. 1997;163(12):47–68. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jackson GS, et al. Matrix-shimmed ion cyclotron resonance ion trap simultaneously optimized for excitation, detection, quadrupolar axialization, and trapping. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry. 1999;10(8):759–769. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bruce JE, et al. A novel high-performance Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance cell for improved biopolymer characterization. Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 2000;35(1):85–94. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9888(200001)35:1<85::AID-JMS910>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marshall AG. Milestones in Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry technique development. International Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 2000;200(13):331–356. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barlow SE, Tinkle MD. \“Linearizing\” an ion cyclotron resonance cell. Review of Scientific Instruments. 2002;73(12):4185–4200. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holliman CL, Rempel DL, Gross ML. Detection of high mass-to-charge ions by Fourier transform mass spectrometry. Mass Spectrometry Reviews. 1994;13(2):105–32. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gooden JK, Rempel DL, Gross ML. Evaluation of different combinations of gated trapping, RF-only mode and trap compensation for in-field MALDI Fourier transform mass spectrometry. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry. 2004;15(7):1109–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tolmachev AV, et al. Trapped-Ion Cell with Improved DC Potential Harmonicity for FT-ICR MS. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry. 2008;19(4):586–597. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McIver JR, McIver RT., Jr . Fourier Transform Mass Spectrometry: Principles and Appications. IonSpec Corporation; Lake Forest: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jebanathirajah JA, et al. Characterization of a New qQq-FTICR Mass Spectrometer for Post-Translational Modification Analysis and Top-Down Tandem Mass Spectrometry of Whole Proteins. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry. 2005;16(12):1985–1999. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beu SC, Laude DA., Jr Elimination of axial ejection during excitation with a capacitively coupled open trapped-ion cell for Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry. Analytical Chemistry. 1992;64(2):177–80. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haung SK, Rempel DL, Gross ML. Problems With Quantification of Ion Abundances and a Proposed Solution in presented at the 32nd Annual Conference on Mass Spectrometry and Allied Topics; May 27 –June 1, 1984. San Antonio, TX. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mitchell DW. Realistic simulation of the ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometer using a distributed three-dimensional particle-in-cell code. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry. 1999;10(2):136–152. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wood TD, Schweikhard L, Marshall AG. Mass-to-charge ratio upper limits for matrix-assisted laser desorption Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry. Analytical Chemistry. 1992;64(13):1461–9. [Google Scholar]