Abstract

Stem cell–based cellular cardiomyoplasty represents a promising therapy for myocardial infarction. Noninvasive imaging techniques would allow the evaluation of survival, migration, and differentiation status of implanted stem cells in the same subject over time. This review describes methods for cell visualization using several corresponding noninvasive imaging modalities, including magnetic resonance imaging, positron emission tomography, single-photon emission computed tomography, and bioluminescent imaging. Reporter-based cell visualization is compared with direct cell labeling for short- and long-term cell tracking.

Coronary heart disease accounts for 36% of all cardiovascular death and is the leading cause of heart failure in the U.S. (1). Although post-infarction survival rates have been improved in recent years, cardiac dysfunction due to segmental loss of ventricular mass remains a major problem (2). In fact, progressive left ventricular remodeling occurs in between one third to one half of survivors of acute myocardial infarction with ejection fractions <40% (3), despite optimal medical therapies, none of which is able to effectively reverse the detrimental remodeling process (4). Even when implantable cardioverter-defibrillators are used, 5-year mortality from ischemic cardiomyopathies exceeds 35% (5). Although cardiac transplantation is the most effective therapy, the disparity between organ demand and supply limits its applicability. A novel treatment strategy often referred to as “cellular cardiomyoplasty” includes local (intramyocardial, intracoronary) and systemic (intravenous) delivery of fetal/neonatal cardiomyocytes (6,7), skeletal myoblasts (8–10), embryonic stem cells (11,12), bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) (13–19), or hematopoietic stem cells (20–22). This strategy attempts to enhance cardiac function by repopulating the infarcted region with viable cardiomyocytes and, therefore, bears great promise for restoration of ventricular function after infarction beyond that achievable with current medical therapy (23).

More than 6 phase I clinical trials have been conducted using skeletal myoblasts (24) (for review, see Menasche [25]); these trials identified a proarrhythmic risk associated with myoblast implantation and required implantation of an internal cardioverter-defibrillator in patients participating in the ongoing MAGIC (Magnesium in Coronaries) trial. Clinical trials using bone marrow cells have demonstrated the safety and feasibility of the procedure but have yielded mixed results in terms of therapeutic benefit (Table 1). Although significant improvement of cardiac function has been documented in a few trials (26–29), results from 4 double-blinded randomized and placebo-controlled trials are not as promising, either showing moderate (30), short-term benefits (31), or no improvement (32,33). Attempts to mobilize hematopoietic stem cells (CD34+) from the bone marrow by granulocyte-colony stimulating factor also yielded ambiguous results. Whereas a small-scale FIRSTLINE-AMI (Front-Integrated Revascularization and Stem Cell Liberation in Evolving Acute Myocardial Infarction by Use of Granulocyte-Colony-Stimulating Factor) trial showed improvement of left ventricular function (27), negative results were obtained from a large-scale double-blinded randomized and placebo-controlled trial, REVIVAL (Regenerate Vital Myocardium by Vigorous Activation of Bone Marrow Stem Cells) (34). Issues such as selection of low-risk patients (35) and microvasculature obstruction have been proposed to explain the negative results. However, the elimination of infused cells from the heart might have been a primary culprit. Studies showed that less than 3% of unfractionated bone marrow cells were retained in the infarcted heart within a few hours after intracoronary infusion (36). Both cell type and delivery route (i.e., intracoronary, intramyocardial, or intravenous) have been shown to affect the retention of cells in the heart (36,37). Unfractionated bone marrow cells used in many trials contain various cell populations, some of which may have adverse effect on cardiac repair (38). Critical issues raised from these clinical trials that need to be addressed include 1) the fate of engrafted cells and optimization of cell survival; 2) the optimal cell type; and 3) mechanisms of action (25,38–41). Experts in the field questioned whether sufficient preclinical data have been gleaned to understand pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and mechanism to provide the type of solid support on which clinical trials are built (38). Imaging-based cell-tracking methods can potentially evaluate the short-term distribution of infused cells (discussed in the direct labeling method section) or their long-term survival (discussed in the reporter gene approach section) and cardiac differentiation status (see the section “Optical Imaging”). Therefore, these methods would play an indispensable role in detailed preclinical studies to optimize the cell type, delivery methods, and strategies for enhancing cell survival. Safety and ethical issues imposed on a human study would limit the clinical translation of those methods that require extensive manipulation of cells; however, most direct labeling methods discussed in the sections “Magnetic Resonance Imaging” and “Radionuclide Imaging” have already applied in patients or would be suitable for the clinic.

Table 1.

Clinical Trials Using Autologous Bone Marrow Cells

| Clinical Trial Name

(Reference) |

Patients

(n) |

Major Findings |

|---|---|---|

| TOPCARE-AMI (26,28) | 20 | Significant improvement of LVEF and regional wall motion in the infarct zone in acute MI patients at 4 months after infusion of bone marrow or blood-derived progenitors. |

| ASTAMI* (33), preliminary results (30) | 100 | No improvements of LV function compared with controls in acute MI patients at 6 months after infusion of cells. |

| BOOST* (31) | 60 | No improvement of LV systolic function compared with the controls in acute MI patients at 18 months after intracoronary infusion of cells. |

| STEMI* (32) | 66 | No improvement in LVEF in acute MI patients with relatively well-preserved cardiac function at 4 months after injection of cells. |

| FIRSTLINE-AMI (27) | 30 | G-CSF–induced mobilization of mononuclear CD34+ cells led to improvement in LVEF and prevention of LV remodeling in acute MI patients at 12 months after G-CSF treatment. |

| REVIVAL* (34) | 114 | G-CSF–induced mobilization of mononuclear CD34+ cells had no influence on infarct size, LV function, or coronary restenosis in acute MI patients at 4 to 6 months after G-CSF treatment. |

| REPAIR-AMI* preliminary results (30) | 204 | A 3% improvement in LVEF over controls in acute MI patients at 4 months after infusion of cells. |

| IACT (29) | 18 | Significant improvement in LVEF and increased FDG uptake in the infarcted region in chronic MI patients at 3 months after intracoronary injection of bone marrow mononuclear cells. |

Denotes double-blinded, randomized, and placebo-controlled trials.

FDG = fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose; G-CSF = granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; MI = myocardial infarction.

A number of methods are available to visualize cells; in general, they can be divided into 2 categories: 1) the direct labeling method and 2) the reporter gene approach. The former involves using an imaging-detectable probe that can be loaded into cells and would remain intracellular during tracking. This method does not involve extensive manipulation of the cells and, therefore, is preferred for clinical implementation. It has 2 inherent limitations: labels may be diluted upon cell division, making these cells invisible; and labels may efflux from cells or may be degraded over time. Therefore, this method is suitable for short-term tracking to answer the question: “Where do the cells go?” and may allow monitoring of second or third delivery of cells when previous labels disappear. For clinical application, the primary issue is to identify suitable labels that are safe to cells even when the intracellular label accumulates to a high concentration. Contrast media or agents that already have been approved for clinical use, such as 2-[F-18]-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose for positron emission tomography (PET) (36), [In-111]oxine for single-photon emission computerized tomography (SPECT) (42,43), and superparamagnetic iron oxide (SPIO) particles for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (43), are among the first being tested in various clinical trials of cell tracking.

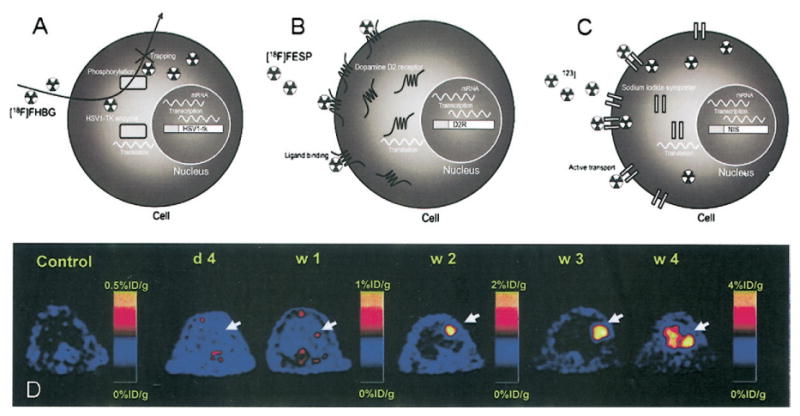

For preclinical applications, in addition to direct labeling, the reporter gene approach is used. This approach involves inserting a reporter gene(s) into stem cells for the purpose of tracking. Products of reporter gene expression generally can be divided into 3 categories, enzymes, receptors, or transporters. Diagrams in Figs. 1A to 1C illustrate how these 3 reporters work for radionuclide imaging modalities.

Figure 1.

Diagrams of detection of (A) enzyme-based (e.g., herpes simple virus type 1 thymidine kinase [HSV1-tk]), (B) receptor-based (e.g., dopamine type 2 receptor [D2R]), and (C) transporter-base (e.g., sodium-iodide symporter [NIS]) reporter genes detected by positron emission tomography using F-18–labeled tracers or by single-photon emission tomography using I-123 (reprinted from Acton and Zhou [44] with permission from Edizioni Minerva Medica). In A, 9-[3-fluoro-1-hydroxy-2-(propoxymethyl)]guanine tracers that are bound and metabolized by the HSV1-TK will be trapped inside the cells, whereas unbound ones will diffuse out of cells. In B, tracers binding to D2R on cell surface will contribute to the imaging signal, whereas unbound ones will be washed out. In C, tracers will be transported into and out of cells by NIS; cells from nonthyroid tissues, however, cannot retain the iodine inside through organification (see the section “Radionucleotide Imaging” for details). (D) In vivo assessment of cell survival and proliferation over time. Ten million (107) murine embryonic stem cells transfected with a truncated version of HSV1-tk were injected into the myocardium of a noninfarcted nude rat; positron emission tomography was performed at day 4 and weeks 1, 2, 3, and 4. Approximately 1 mCi [F-18]9-[3-fluoro-1-hydroxy-2-(propoxymethyl)]guanine was injected intravenously for visualization of HSV1-tk–expressing cells. Positive signal was observed at week 1 in animals receiving cells, but control animals had background activities only. Quantification of imaging signals showed a drastic increase of thymidine kinase activity from week 2 to week 4, corresponding to proliferation of embryonic stem cells into intracardiac and extracardiac tumors, that is, teratoma (reprinted from Cao et al. [45] with permission).

To prevent loss of the reporter upon cell division, a stable transfection, that is, integration of the reporter gene into cell genome, is necessary; thus, extensive molecular manipulation is required (44). Reporter genes would be extremely useful in assessing survival status of the implanted cells because the reporter will be expressed as long as the cells are alive and will be passed to daughter cells upon cell division; this approach has been used to monitor the uncontrolled growth of embryonic stem cells into a tumor (teratoma) when a large number of cells are implanted, as shown in Figure 1D. If a cardiac specific promoter is used to control the expression of the reporter (46,47), then the cardiac differentiation of stem cells in their physiological environment also can be monitored. The reporter gene approach would allow selection for optimal cell type and engraftment sites that promote survival or differentiation of implanted cells.

This review describes methods for cell tracking based on their corresponding imaging modalities: MRI, radionuclide tomographic imaging techniques focusing on PET and SPECT, and optical imaging. For each imaging modality, direct labeling methods as well as reporter gene approaches are discussed, in addition to their utility in clinical and preclinical cell tracking applications.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Superparamagnetic iron oxide particles

Superparamagnetic iron oxide particles are well known for their ability to generate MR contrast. For diagnostic MRI, 2 acronyms are used for iron-based magnetic particles: SPIO particles and ultra-small SPIO (USPIO) particles; both consist of a crystalline iron oxide core coated with polymers such as dextran, polyethylene glycol, and starch; SPIOs, with a hydrodynamic diameter >30 nm, are taken up by the reticuloendothelial system in the liver and spleen, leading to remarkable signal loss in these tissues. The USPIOs (<30 nm diameter) can escape the initial uptake by liver and spleen and reach other targets, such as lymph nodes (48), and can serve as a blood pool agent (49). They are obtained from SPIOs by size exclusion or other fractionation procedures; compared with SPIOs, USPIOs have lower T2 relaxivities and longer blood half life, both as the result of their smaller particle size. Synthesis of SPIO and USPIO particles, their magnetic properties (e.g., relaxivities) and clinical applications are reviewed recently by Lawaczeck et al. (50).

Two compounds within the SPIO family have been approved for clinical use: one compound under the name of Feridex (Berlex Biosciences, Ricmond, Virginia; or ferumoxides) in the U.S. or Endorem in Europe, and the other under the name of Resovist (or SH-U555A; Schering, Berlin, Germany) in Europe and Japan. Both compounds are manufactured for intravenous administration and are targeted at (metastatic) tumors in the liver and spleen.

Besides their role in clinical diagnostic imaging, SPIOs and USPIOs have become a useful tool for cell tracking in the brain (51–53), heart (15,54–56), and other organs (57,58). A recent clinical trial in European Union demonstrated for the first time in humans tracking of therapeutic dendritic cells labeled with Feridex (43). Although it represents a clinically applicable method to label cells using Feridex or other SPIOs approved for clinical imaging (59), this approach will require U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval. Furthermore, when injected intravenously, Feridex or other SPIOs is primarily taken up by the reticuloendothelial system (e.g., Kupffer cells), which metabolizes the excess iron; nonphagocytic stem cells, however, may not have this capability; therefore, effects of iron overloading on stem cell proliferation and differentiation should be investigated before the clinical application of Feridex or other SPIOs.

Endocytosis is a major mechanism for intracellular uptake of SPIO particles into various types of cells such as T cells (60) and macrophages (61). Transfection agents (TAs) such as poly-L-lysine (59), cationic liposome (62), or protamine sulfate (63) forms complexes with SPIO particles in the labeling solution and greatly improve the efficiency of endocytosis in cells that cannot avidly phagocytose SPIOs. In addition, these agents seemed to protect the cells from SPIO particles, which otherwise were found to be toxic to nonphagocytic cells at high concentrations (62). Other ways to enhance endocytosis-mediated intracellular accumulation of SPIO particles include covalent conjugation of SPIOs to antibodies or to cell penetrating peptides such as HIV transactivator (tat) peptide (58,64) or proteins (65). Antibody-linked SPIOs enter into cells via receptor-mediated endocytosis (57,66) whereas an adsorptive endocytosis (67) is thought to mediate the uptake of tat peptide-conjugated SPIOs. Metabolic fate of SPIO particles are expected to be similar after endocytosis-mediated uptake. As demonstrated in the case of SPIO-TA complexes, after being endocytosed, they are localized to endosomes (68,69), which are later fused with lysosomes, where the SPIO is degraded (68). The long-term viability, growth and apoptotic indexes of Feridex-TA–labeled human BMSCs were found unaffected as compared with the unlabeled cells (70). However, it is controversial over whether the differentiation of BMSCs was affected by SPIO particles or by the type of TA used: it has been shown that chondrogenesis of BMSCs was inhibited by Feridex-poly-L-lysine labeling (71) but not by Feridex-protamine labeling (72). No studies on effects of SPIO labeling on cardiac differentiation of stem cells have been reported so far.

In addition to endocytosis, the electroporation procedure (73) has been investigated to achieve instant intracellular delivery of SPIOs, therefore eliminating the need for transfection agents, conjugating antibodies and peptides and cell culture procedures all together. Because the SPIO particles are directly internalized to cytoplasm but not insulated in membrane vesicles such as endosomes, their metabolic fate may not be the same as those being endocytosed.

Recently, micrometer-sized SPIO (MPIO) particles (∼1 to a few micrometers in diameter) have been proposed for more sensitive detection and have been investigated in a number of preclinical studies. These particles contain ∼20% to 60% magnetite by weight and are made by a special process whereby a mixture of magnetite and polystyrene/divinyl benzene is dispersed in water, and the suspension is polymerized to trap the magnetite in the polymer matrix; the magnetite is dispersed throughout the beads. Initially developed for magnetic cell separation (74), MPIO particles are approximately 35-fold larger in diameter and more than 40,000 times larger in volume than the USPIOs; by far, these particles have the highest sensitivity for MRI detection (17,69,75,76).

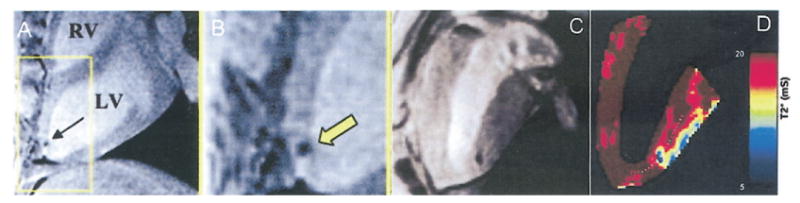

The detectability of labeled cells depends on a number of factors, including magnetic field strength, how much iron accumulates inside each cell (labeling efficiency), the number of cells implanted, relaxivity of the IO particle, and spatial resolution of the image. Feridex-labeled stem cells were readily detected by MRI when 107 to 108 stem cells each containing approximately 16 pg of Fe (59) were injected directly into myocardium of a swine as demonstrated in Figures 2A and 2B, reprinted from Kraitchman et al. (15). For stem cells labeled with MPIO particles, an efficiency of 0.2 ± 0.18 ng iron oxide per cell (equivalent to 143 ± 130 pg Fe per cell) was reported by Hill et al. (77); note that cellular iron oxide content in this work is indirectly quantified through fluorescence label of the particle; detection of 105 cells implanted into a pig heart was reported at a 1.5-T scanner as shown in Figure 2C, reprinted from Hill et al. (77).

Figure 2.

Detection using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at 1.5 T, of Feridex-labeled mesenchymal stem cells (107 to 108 cells) injected into the myocardium of a swine; MRI was performed 24 h after injection. (B) Magnification of view inside the yellow box in A (reprinted from Kraitchman et al. [15] with permission). (C) Detection using MRI at 1.5 T of micrometer-sized superparamagnetic iron oxide–labeled mesenchymal stem cells (105 cells) implanted in the myocardium of a swine (reprinted from Hill et al. [77] with permission). (D) The color map corresponds to T2* values indicated on the scale immediately to the right; T2* values of micrometer-sized superparamagnetic iron oxide–labeled cells are very close to those of lateral myocardial wall at the heart/lung boundary. Obviously, the reduction of T2* at myocardium and air interface is a source of interference for detection of cells. LV = left ventricle; RV = right ventricle.

Using SPIO labels, the detection of a small number of cells or single cells by MRI has been achieved in the rat and mouse brain (53,78,79). In contrast, detection of single or small numbers of cells in the heart by MRI is an even greater challenge because of cardiac motion and limited intracellular concentration of imaging probes. For T2/T2*-based MRI detection, the signal loss at the boundary of heart and lung as the result of susceptibility difference also would pose an interference as demonstrated in Figure 2D: the T2* values of the lateral myocardium wall were very close to those of labeled cells at the injection site. Injections performed under X-ray, NOGA cardiac mapping system, or MR guidance will ensure the mid-myocardium location of implanted cells; however, potential cell migration or wall thinning may push these cells in close proximity to the epicardial side of the lateral wall.

Ferritin and transferrin receptor

Although iron is an indispensable participant in numerous physiological processes and biochemical reactions in the body such as transportation of oxygen in the blood, free iron ions are toxic to cells, and the body has an elaborate set of mechanisms to bind iron in various tissue compartments. Ferritin is such a metalloprotein and is found mainly in the liver, which can store approximately 4,500 iron ions in a hollow shell made of 24 identical subunits. Ferritin genes have been proposed as a reporter gene for MRI detection: through transfection by an adenoviral vector, overexpression of ferritin genes inside cells leads to intracellular iron accumulation and MR contrast as the result of shortening of T2/T2* (80,81).

Transferrin is a plasma protein for iron transport. Each transferrin molecule has the ability to carry two iron ions (Fe3+) and is taken up by a transferrin receptor (TFR) on the cell surface; consequently, iron molecules are transported inside the cell. An engineered TFR (82,83) has been proposed as a reporter gene; this TFR gene expresses an approximate 5-fold excess of transferrin receptors on the cell surface and lacks the iron regulatory region; therefore, TFR expression is not regulated by intracellular iron concentration; for TFR overexpressing cells to accumulate sufficient iron for imaging, transferrin proteins are covalently linked to USPIO particles and the complex is injected intravenously; gradient echo MRI then detects the signal loss (as the result of T2/T2* decrease) induced by uptake of transferrin-USPIO by cells overexpressing TFR. Compared with the ferritin reporter system, the requirement for covalent attachment of USPIOs to transferrin is cumbersome but increases the detection sensitivity because of the larger particle size of USPIOs compared with ferritin. Iron overloading due to the overexpression of a mutated TFR that lacks the iron regulatory region may disrupt cellular metabolism, leading to toxicity as evidenced by elevated reactive oxygen species level in the cell (84). The feasibility of using ferritin and the TFR reporter system for cell tracking in the mouse brain at 1.5-T and 7-T magnetic field strength has recently been investigated (84).

Gadolinium chelates

In contrast to the negative image contrast (hypointensity) generated by USPIO/SPIO/MPIO particles by T2/T2* mechanism, gadolinium III [Gd(III)] produces positive contrast (enhancement) on T1-weighted MR images. Although the relaxivity is very similar among the various small molecular Gd(III) chelates currently in clinical use, they differ in 2 structural features: ionic versus nonionic and linear versus macrocyclic (85), for example, GdDTPA (Magnevist; Berlex Biosciences) is a linear and ionic chelate, whereas gadoteridol (ProHance; Bracco-Byk Gulden, Konstanz, Germany) is a nonionic and macrocyclic chelate. Because of their relatively low longitudinal relaxivity (4 mmol l−1s−1), high intracellular accumulation is the key for the utility of these contrast media as labeling agents. It has been estimated that the number of internalized Gd(III) chelates on the order of 107 to 108 per cell is necessary for MRI visualization of cells (86). The structural features mentioned previously may determine their ability to penetrate the cell membrane and potential toxicities to the cells exposed to high concentrations during incubation. As the result of the nonparticulate nature of the Gd chelates, pinocytosis (used by cells for absorption of extracellular fluids) instead of phagocytosis would be a major mechanism for their cellular uptake; recent studies show that pinocytosis appears to be a very effective way for labeling stem cells by incubating cells with high concentrations of Gd(III) chelates for a period of a few hours (87). Compared with pinocytosis, which is a form of endocytosis (88) and in which Gd(III) chelates are sequestered in membrane vesicles, electroporation procedure results in intracellular distribution of Gd molecules and a greater longitudinal relaxation rate constant (R1) and higher MR signal intensity of labeled cells compared with pinocytosis (89). A class of macrocyclic lanthanide chelates has been synthesized that label cells by inserting 2 hydrophobic alkyl chains into cell membranes with the hydrophilic metal binding site facing the extracellular medium (90). By association only with the cell membranes, these labels are unlikely to be metabolized by cellular enzymes that lead to release of toxic free Gd ions; furthermore, Gd chelate is more accessible by extracellular water resulting in a higher relaxivity.

F-19–based labeling agents

In addition to the nuclei of H-1, some other nuclei, including F-19, P-31, and C-13 also have MR phenomena and can be detected; the multinuclear capability is usually included in research scanners (or spectrometers); for clinical scanners, capability of nucleus other than H-1 is also available as optional packages. The gyromagnetic ratio of F-19 nuclei is approximately 90% of the proton; therefore, it is a sensitive nucleus for MR detection; furthermore, there is no background F-19 signal because F-19 is not a natural metabolite in mammals. The anatomical localization of the F-19 signal is achieved by overlaying F-19 images on H-1 images acquired sequentially. F-19-based compounds such as perfluoropolyether have been used for tracking dendritic cells in animals (91). Preliminary results on F-19 MR imaging of stem cells labeled with perfluoro-nanoparticles are promising (92,93).

Radionuclide Imaging

Because of their exquisite picomolar (10−11 to 10−12 mol/l) sensitivity (94), PET and SPECT imaging modalities are able to detect tracer quantity of radioisotopes for studying biological processes in living subjects. Technological developments of both PET and SPECT have led to the implementation of specialized systems for small animal imaging with much greater spatial resolution (1–2 mm) (95–103), which has dramatically advanced the field of cell tracking in animal models in vivo.

Radioisotope-based cell labels

Radioactive isotopes such as [In-111]oxyquinoline (oxine) (42) and [T-99m] hexamethylprophylene amine oxime (104) have been used in the nuclear medicine clinic for labeling autologous white blood cells, which are subsequently infused back to the patients for localization of inflammatory sites. In general, radioisotopes with a relatively long decay half-life are used to track cells during a period of several hours or even days, for instance In-111 (T1/2 = 2.8 days) for SPECT and Cu-64 (T1/2 = 12.7 h) for PET (105). The isotope is carried into the cells via a lipophilic chelator, which governs the initial extraction of the tracer into the cells. Once inside the cells, a trapping mechanism reduces the lipophilicity of the molecule, and the isotope is retained. After a short incubation period, the cells are washed to remove any unbound activity and are injected into the host. Labeling efficiencies close to 100% are not uncommon, although cellular concentrations of the isotope depend on factors, including cell type, incubation time, and concentrations. For cell tracking in the heart, [In-111]oxine (106–110), [In-111]tropolone (111), [Tc-99m]exametazime (112), and [F-18]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (36) have been used. The biodistribution of In-111-labeled stem cells after intravenous (106), intramyocardial, intracoronary, and interstitial retrograde coronary venous delivery has been reported (37): it was found that most delivered cells were not retained in the heart for each delivery modality, which raised the concern that proangiogenic or other physiological effects conveyed by these cells may have a negative impact on tissues or organs that are not the target of these cells.

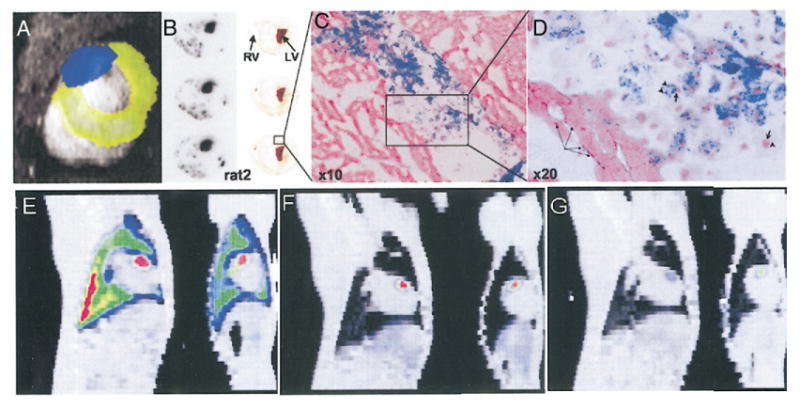

A dual isotope SPECT study of In-111-labeled cardiomyoblasts and [Tc-99m]sestamibi enabled the imaging of both cells and perfusion deficit in the infarcted region simultaneously (109); the SPECT images were registered with the high-resolution MR images, which provides detailed myocardial anatomy for localization of cells, as shown in Figure 3A (113); the autoradiographic confirmation of In-111 signal with the histological staining of stem cells are presented in Figures 3B to 3D. As a step further from detection of a large number of cells implanted in the heart, the monitoring of stem cell homing using SPECT has been achieved in small animals using a Gamma camera (108) and in large animals using a clinical SPECT scanner (110). As shown in Figures 3E to 3G, after being doubly labeled by In-111 and Feridex, BMSCs were intravenously injected into a dog model, and their homing to the heart was detected by the use of SPECT; however, the use of MRI was not able to detect these small numbers of cells. Although the minimal number of In-111-labeled cells that can be detected in the heart in vivo is not known, a recent study using phantom suggested that 10,000 cells could be detected in a 16-min scan with appropriate background correction (111).

Figure 3.

(A) In vivo single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) imaging of In-111–labeled stem cells implanted in the infarcted rat heart; a dual-energy window detects simultaneously Tc-99m (pseudo-colored in yellow) and In-111 (blue) signals; the SPECT images were coregistered on a magnetic resonance image (grey) (reprinted from Shen et al. [113] with kind permission of Springer Science and Business Media). (B) Autoradiographs of heart slices obtained after In-111 and Feridex double-labeled stem cells were implanted in the infarcted heart of a rat; (C and D) Prussian blue staining of iron for localization of stem cells (reprinted by permission of the Society of Nuclear Medicine from Zhou et al. [109]). (E and F) Homing of In-111–labeled bone marrow–derived mesenchymal stem cells to infarcted heart (dog) after intravenous injection at day 1 (E), day 2 (F) and day 7 (G) by SPECT imaging is shown. For each panel, sagittal (left) and coronal (right) view of fused SPECT (color) and CT (grey) images are shown. Initial retention of cells in the lung is indicated by strong In-111 signal in the lung (reprinted from Kraitchman et al. [110] with permission). LV = left ventricle; RV = right ventricle.

One concern of radioactive labeling agents is the potential radiation damage to the cell as demonstrated in a study in which hematopoietic progenitor cells were labeled with [In-111]oxine and injected into the cavity of the left ventricle heart in a rat model of myocardial infarct (108); although gamma imaging revealed homing of the progenitor cells to infarcted myocardium, significant impairment of proliferation and function of labeled cells was observed. A recent study by Jin et al. (111) comparing In-111 incubation activity and cell viability at day 14 suggests that 100% viability can be achieved provided the incubation activity is ≤0.9 MBq.

Rapid efflux of labels out of cells over the course of time (105,109) leads to label loss from viable cells. In a SPECT study using [In-111]oxine-labeled cardiomyoblasts (109), one third of the original In-111 signal was obtained 72 h after injection when corrected for radio decay of In-111. Label loss introduces errors to the detection of surviving cells because one cannot distinguish whether reduction of In-111 signal is due to loss of labels from viable cells or is due to death or remove of cells from the injection site. Therefore, the direct labeling approach is more suitable for the short-term tracking of injected cells whereas a reporter gene approach, discussed next, would allow monitoring of survival of implanted cells over a longer period of time.

Reporter genes for PET/SPECT detection

A number of reporter genes have been developed for PET and SPECT imaging (44,114). Herpes simplex virus type 1 thymidine kinase (HSV1-TK) or its mutant form HSV1-sr39tk (115) expresses a viral thymidine kinase (note that tk represents the gene whereas TK represents the protein). Thymidine kinase phosphorylates a range of substrates, including thymidine (the natural substrate), analogs of pyrimidine, and acycloguanosines. The monophosphates resulted from TK reaction are converted by cellular enzymes to di- and triphosphates, which are trapped inside the cells, as shown in Figure 1A; in contrast, cells not expressing TK will not metabolize or retain the tracer. A variety of pyrimidine analogs and acycloguanosine derivatives, e.g., 9-[3-Fluoro-1-hydroxy-2-(propoxymethyl)]guanine (FHBG), have been designed for better tracer retention and detection by PET and SPECT imaging of HSV1-tk expression (see review by Tjuvajev et al. [116]). The metabolites of TK, if present at a sufficiently high concentration, result in cell death; therefore, HSV1-tk has been used as a suicide gene in many gene therapy protocols (117–119) or as a negative selection marker to eliminate TK-expressing cells in standard molecular biology protocols. By taking advantage of the high sensitivity of PET or SPECT imaging modalities, it is possible to administer tracer quantities of the substrate labeled with a positron or single-photon emitting radioisotope for detection of HSV1-tk expression and, as such, toxicity to TK-expressing cells should be negligible: the feasibility of utilizing HSV1-tk as a reporter (instead of a suicide) gene has been demonstrated (120–127). HSV1-tk reporter gene has been examined in preclinical studies for evaluations of gene therapy directed at the myocardium (128,129).

The concept of reporter gene is applicable to cell tracking. Surviving cells can be tracked when a promoter of viral origin (e.g., the promoter of cytomegalovirus [CMV]) is used to control the expression of the reporter gene; such a reporter gene is constitutively active as long as the cell is alive and is minimally regulated by physiological processes in the cell. Positron emission tomograpic imaging detection of cardiomyoblasts (H9c2 cells) that are transiently transfected with CMV-HSV1-tk and were subsequently injected into rat myocardium has been demonstrated (130). However, to monitor the survival or proliferation of implanted cells over the course of time, it is necessary to stably integrate the reporter gene into genomes of implanted cells. Stable transfection will ensure that the reporter will not be diluted upon cell division (45). However, the reporter protein, when it is of exogenous origin and is exposed outside cells, may induce immune reactions from the host, leading to elimination of reporter signals.

Dopamine type 2 receptor (D2R) is a receptor-based reporter gene and is one of the few systems that could be used for cell tracking in the brain because the reporter probe, for instance, [F-10]fluoroethylspiperone (FESP), readily crosses the intact blood-brain barrier. It binds to the D2R with high affinity and has been shown to provide a quantitative measure of D2R expression in living animals (131). To overcome the potential problems that the occupancy of the ectopic D2R by the endogenous agonist may increase levels of cellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), leading to physiologic consequences on the target tissue/cells (132), mutant strains of the D2R that do not activate the signal pathway have been developed for PET imaging (133). In the brain, the presence of endogenous D2R, particularly in the striatum, would provide a large background signal and make it difficult to resolve the presence of the D2R reporter system. A similar problem may apply to the myocardium, in which expression of a detectable level of D2R is reported (134).

The sodium-iodide symporter (NIS), as shown in Figure 1C, has been proposed as a reporter gene (135–137) and has been applied to cardiac imaging (138,139). The NIS occurs naturally in high concentrations in the thyroid, with lower concentrations in salivary glands, stomach, thymus, breast, and other tissues. The symporter is a membrane glycoprotein and provides an active transport mechanism for sodium and iodine ions into cells. The expression of the symporter can be imaged with radioactive iodine, such as I-123 for SPECT or I-124 for PET, or other tracers, which bind to the same site, such as [Tc-99m]pertechnetate. A broad range of cell types and delivery mechanisms have been used with the NIS reporter. The NIS is not immunogenic, and its endogenous expression is limited to a few tissues, allowing it to be used in a variety of imaging applications. However, the use of NIS as a reporter system has been hampered somewhat by the efflux of the radiotracers from nonthyroid tissues. In the thyroid, organification of the iodine occurs, catalyzed by the enzyme thyroperoxidase, which effectively traps the iodine after it is transported into the tissue. Coexpression of this enzyme with the NIS reporter gene may be required to improve the retention of radioactive iodine in transfected cells (140).

An additional benefit of the reporter gene approach is the possibility of linking a therapeutic gene to the reporter, allowing the system to monitor both cell trafficking and gene therapy simultaneously (141). For example, skeletal myoblasts have been used to deliver a therapeutic gene, such as vascular endothelial growth factor, which may aid in the formation of new vessels in the region being regenerated by the grafted myoblasts (142). Coupling a reporter gene to stem or progenitor cells would allow tracking of not only cell delivery and survival, but also the expression of the therapeutic gene.

A major disadvantage of reporter gene approaches for cell tracking is the requirement for molecular manipulations of the cells under study. When a virus or a viral vector is used for transfection, immune reactions may be induced as a result of the expression of viral proteins or even the reporter protein itself when nonmammalian proteins, such as HSV1-tk, are used, leading to loss of long-term expression of the reporter. Lentiviral vector is preferred for stable integration of reporter genes into stem cells because it can transfect both dividing and nondividing cells and lead to high levels of transgene expression (143,144). Other potential concerns regarding long-term efficacy of the method include reporter gene silencing, in which reporter gene expression decreases over time with progressive cell differentiation. Lentiviral vectors (145) and certain pharmacologic interventions (146) have been proven to reduce the gene silencing problem.

Optical Imaging

Luminescence and fluorescence

Two optical imaging techniques, luminescence and fluorescence, have been used for stem cell tracking in vivo (147–151). Luminescence in the form of light (wave length in the range of 400–700 nm) is generated from an enzymatic reaction catalyzed by, e.g., firefly luciferase (Fluc); when cells expressing Fluc are supplied with D-luciferin, a substrate of the enzyme, cells will emit luminescence. Although weak, this light energy can be captured by a sensitive charge-coupled device camera in a light-sealed box. In addition to Fluc, other luciferases, such as Renilla luciferase with its substrate, coelenterazine, have also been utilized as reporter system (152,153). Because of limited tissue penetration of luminescence and the fact that luciferase is a nonmammalian protein, this imaging modality is limited to small animal models. In addition, luminescence detection relies on a continuous wave technique (154), leading to a diffusive image on the animal surface, unlike PET/SPECT/MR imaging modalities, in which data are acquired in a tomographic fashion. Still, luminescence imaging is extremely useful for high-throughput screening because of its high sensitivity and its straightforward imaging procedures. Increasing the amount of substrate (e.g., D-luciferin) for an enzymatic reaction (e.g., catalyzed by Fluc) will increase the amount of the product (e.g., luminescence) even when the concentration of the enzyme (Fluc) remains the same; therefore, the detection threshold of the luciferase reporter system can be significantly reduced by administering an excess amount of D-luciferin, which does not appear to be toxic to animals even in large doses.

Fluorescence is generated by excitation of a fluorophore; green fluorescent protein (GFP) and its variants are the most commonly used optical reporters. Tomographic detection of fluorescence is feasible; however, because of high photon absorbance and scattering in the visible range, only near infrared (≥700 nm) fluorophores can be detected when located a few centimeters underneath the surface. Shallow penetration is a severe limitation for in vivo detection even in small animals, not to mention in humans. Attachment of a fluorophore to a stem cell would allow detection of stem cells by histology using conventional microscopes. Further developments in optical imaging techniques, such as quantum dots (155), diffuse optical tomography (156,157), and optical coherence tomography (158), offer tremendous enhancements to currently available technology; their applications, however, are primarily limited to preclinical researches.

Stem cell differentiation monitored by cardiac-specific reporter genes

A reporter gene permits longitudinal monitoring of fundamental biological processes (e.g. differentiation) within the context of physiologically authentic environments. Monitoring of cardiac differentiation of stem cells by reporter genes is made possible when the reporter is expressed as a consequence of a cardiac specific gene expression. In practice, this monitoring is achieved by using promoter sequence of the cardiac gene to drive the expression of the reporter, rendering the latter under the transcriptional control of the former. Promoters of ventricular myosin light chain 2 (MLC2v) and cardiac alpha myosin heavy chain gene have been used to convey cardiac specificity to reporter genes (159,160). Meyer et al. (46) used the promoter sequence of MLC2v gene to drive the expression of enhanced cyan fluorescent protein (ECFP, a variant of GFP); when stem cells are transduced with MLC2v-ECFP reporter, their cardiac differentiation as determined by expression of MLC2v gene was found to be parallel to the detection of ECFP fluorescence (46). Cardiac specific GFP reporter (or its variants) would be extremely useful for screening or selection of stem cells undergoing cardiac differentiation by fluorescent microscopy or flowcytometry (161). To monitor stem cells undergoing cardiac differentiation in vivo, luminescent (e.g., Fluc) or NIS reporter under cardiac specific promoters would be suitable; in vivo luminescent imaging of MLC2v-Fluc expression in the mouse heart has been achieved (47), suggesting that this approach is feasible for monitoring cardiac differentiation of stem cells in small animals. Gamma camera and micro-PET imaging of cardiac alpha myosin heavy chain–NIS expression in the heart in a transgenic mouse model has been demonstrated recently (139); this reporter gene is more relevant to clinical application than Fluc because of the nonimmunogenic nature of NIS and the availability of clinical counterparts of the imaging modalities.

Sensitivity and Spatial Resolution: Multimodality Approach

Cell tracking demands high sensitivity and spatial resolution from imaging modalities because of the microscopic targets, that is, stem cells. It is generally thought that optical imaging has the greatest sensitivity: the detectable concentration of the tracer ranges from 10−15 to 10−17 mol/l; this is followed by PET and SPECT imaging (10−11 to 10−12 mol/l) whereas MRI is thought to have the lowest sensitivity (10−5 mol/l) (94). The concentration-based sensitivity assumes the target size is comparable with the image resolution: a 1-cm resolution (equivalent to 1000 μl voxel size) is common for a clinical PET scanner whereas submilimeter resolution (voxel size ranging from 1 μl to 10−3 μl) routinely is obtained on a clinical MRI scanner. When a small number of cells or single cells are the target, the imaging probe is concentrated in a small volume fraction of a voxel; as such, the aforementioned assumption is no longer valid. An estimation of detection limit that includes the contribution of spatial resolution recently was proposed by Heyn et al. (79,162) and leads to the conclusion that the detectability of SPIO-labeled single cells would be similar to micro-PET detection of a few hundred cells labeled with [Cu-64]pyruvaldehyde-bis(N4-methylthiosemicarbazone). However, to the best of our knowledge, detection of a single or a small number of stem cells in the heart has not been reported likely because of various technical challenges discussed in the section “Super Paramagnetic Iron Oxide Particles.” Recent results on detection of MPIO-labeled macrophages that were homed to the heterotypically transplanted heart (76) shed promising light on this issue.

A multimodality reporter system expressing a trifusion protein consisting of red fluorescent protein, Renilla luciferase, and the HSV1-TK enzyme (153) offers the possibility of using the particular imaging technique that best suits the application: fluorescence for microscopy of cells or for cell sorting in vitro, bioluminescence for high sensitivity imaging in vivo in small animals, and PET or SPECT when quantitative accuracy is important, or tomographic localization is necessary. The use of multiple imaging modalities would take advantage of high-detection sensitivity provided by optical and radionuclide imaging and, at same time, superior spatial resolution afforded by MRI or other high-resolution modalities (e.g., CT). The feasibility of localization of stem cells detected by highly sensitive PET or SPECT imaging to the anatomical context described by MRI has been demonstrated in Figure 3A and also in Figures 3E to 3G, in which monitoring of stem cells homing to the heart has been demonstrated using a multimodality approach to achieve high detection sensitivity and high spatial resolution. Because in vivo imaging also plays a significant role in evaluation of cardiac functions, for example, global and regional contractile functions, perfusion, and viability, multimodality imaging would combine stem cell tracking with evaluation of functional recovery resulted from cellular cardiomyoplasty.

Conclusions

The clinical promise for stem cell therapy in ischemic heart disease will not be fully attained without an improved understanding of stem cell biology and mechanisms of repair and regeneration. Early work in cardiac cellular therapy has focused on more fundamental topics, including assessing stem cell survival and optimizing implantation techniques; however, rigorous hypothesis testing and clinical applications will rely heavily on noninvasive imaging techniques to guide these investigations. The development of imaging tools that allow serial assessment of the subject with high spatial resolution and the ability to contemporaneously determine cellular viability represent one of the current goals for these applications. Optical imaging techniques provide high spatial resolution and permit tracking of stem cells but are limited to preclinical use. Nuclear techniques, including reporter genes and direct cellular radiolabeling, afford very good detectability but more limited spatial resolution. Magnetic resonance imaging methods permit good spatial resolution but limited detectability. A multimodality approach using combined PET or SPECT and MRI agents may ultimately prove most useful in clinical settings.

In the September 21, 2006 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine, the results of 3 clinical trials involving stem cell therapy for myocardial infarction were released. The studies reported variable results with respect to improvement in left ventricular function following cellular therapy. In the Schachinger et al. (163) study, a statistically significant—but clinically minimal—benefit in ventriculographic ejection fraction measurement was seen in the group treated with bone marrow cells at 4 months post-therapy. The ASATAMI trial (164) showed no improvement in left ventricular ejection fraction following injection of bone marrow cells, however, infarct size was reduced, and regional wall motion was improved in the treatment group. In the TOPCARE-CHD trial (165), there was a small (2.9%) improvement in left ventricular ejection fraction, but the patients in this study had a history of remote, rather than acute, infarctions which makes the findings even more significant. These reports underscore the need for a greater understanding of the mechanisms underlying stem cell biology and cellular reparative therapy, and their potential uses in the post-infarction state.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grants R01-NS048315 (to Dr. Acton), R21-EB002473 (to Dr. Zhou), and R01-HL081185 (to Dr. Zhou) and by the Pennsylvania State Department of Health Tobacco Block Grant (to Dr. Zhou).

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- BMSC

bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell

- D2R

dopamine type 2 receptor

- ECFP

enhanced cyan fluorescent protein

- Fluc

firefly luciferase

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- HSV1-tk

herpes simplex virus type 1 thymidine kinase

- MLC2v

ventricular myosin light chain 2

- MPIO

micrometer-sized superparamagnetic iron oxide

- NIS

sodium-iodide symporter

- PET

positron emission tomography

- SPECT

single-photon emission computerized tomography

- SPIO

superparamagnetic iron oxide

- TA

transfecting agent

- TFR

transferrin receptor

- TK

thymidine kinase

- USPIO

ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide

References

- 1.Thom T, Haase N, Rosamond W, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2006 Update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2006;113:e85–151. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.171600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Young JB, Dunlap ME, Pfeffer MA, et al. Mortality and morbidity reduction with candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and left ventricular systolic dysfunction: results of the CHARM low-left ventricular ejection fraction trials. Circulation. 2004;110:2618–26. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000146819.43235.A9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.St. John Sutton M, Pfeffer MA, Moye L, et al. Cardiovascular death and left ventricular remodeling two years after myocardial infarction: baseline predictors and impact of long-term use of captopril: information from the Survival and Ventricular Enlargement (SAVE) trial. Circulation. 1997;96:3294–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.10.3294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McMurray J, Pfeffer MA. New therapeutic options in congestive heart failure: part I. Circulation. 2002;105:2099–106. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000014763.63528.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bardy GH, Lee KL, Mark DB, et al. Amiodarone or an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:225–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muller-Ehmsen J, Whittaker P, Kloner RA, et al. Survival and development of neonatal rat cardiomyocytes transplanted into adult myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34:107–16. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reinecke H, Zhang M, Bartosek T, Murry CE. Survival, integration, and differentiation of cardiomyocyte grafts: a study in normal and injured rat hearts. Circulation. 1999;100:193–202. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor DA, Atkins BZ, Hungspreugs P, et al. Regenerating functional myocardium: improved performance after skeletal myoblast transplantation. Nat Med. 1998;4:929–33. doi: 10.1038/nm0898-929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siminiak T, Kalawski R, Fiszer D, et al. Autologous skeletal myoblast transplantation for the treatment of postinfarction myocardial injury: phase I clinical study with 12 months of follow-up. Am Heart J. 2004;148:531–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Menasche P, Hagege AA, Vilquin JT, et al. Autologous skeletal myoblast transplantation for severe postinfarction left ventricular dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1078–83. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Min JY, Yang Y, Sullivan MF, et al. Long-term improvement of cardiac function in rats after infarction by transplantation of embryonic stem cells. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;125:361–9. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2003.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hodgson DM, Behfar A, Zingman LV, et al. Stable benefit of embryonic stem cell therapy in myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H471–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01247.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mangi AA, Noiseux N, Kong D, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells modified with Akt prevent remodeling and restore performance of infarcted hearts. Nat Med. 2003;9:1195–201. doi: 10.1038/nm912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tomita S, Li RK, Weisel RD, et al. Autologous transplantation of bone marrow cells improves damaged heart function. Circulation. 1999;100(Suppl):II247–56. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.suppl_2.ii-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kraitchman DL, Heldman AW, Atalar E, et al. In vivo magnetic resonance imaging of mesenchymal stem cells in myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2003;107:2290–3. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000070931.62772.4E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toma C, Pittenger MF, Cahill KS, Byrne BJ, Kessler PD. Human mesenchymal stem cells differentiate to a cardiomyocyte phenotype in the adult murine heart. Circulation. 2002;105:93–8. doi: 10.1161/hc0102.101442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dick AJ, Guttman MA, Raman VK, et al. Magnetic resonance fluoroscopy allows targeted delivery of mesenchymal stem cells to infarct borders in Swine. Circulation. 2003;108:2899–904. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000095790.28368.F9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dai W, Hale SL, Martin BJ, et al. Allogeneic mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in postinfarcted rat myocardium: short- and long-term effects. Circulation. 2005;112:214–23. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.527937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amado LC, Saliaris AP, Schuleri KH, et al. Cardiac repair with intramyocardial injection of allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells after myocardial infarction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:11474–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504388102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Orlic D, Kajstura J, Chimenti S, et al. Bone marrow cells regenerate infarcted myocardium. Nature. 2001;410:701–5. doi: 10.1038/35070587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jackson KA, Majka SM, Wang H, et al. Regeneration of ischemic cardiac muscle and vascular endothelium by adult stem cells. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:1395–402. doi: 10.1172/JCI12150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murry CE, Soonpaa MH, Reinecke H, et al. Haematopoietic stem cells do not transdifferentiate into cardiac myocytes in myocardial infarcts. Nature. 2004;428:664–8. doi: 10.1038/nature02446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reinlib L, Field L. Cell transplantation as future therapy for cardiovascular disease? A workshop of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Circulation. 2000;101:E182–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.18.e182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hagege AA, Marolleau JP, Vilquin JT, et al. Skeletal myoblast transplantation in ischemic heart failure: long-term follow-up of the first phase I cohort of patients. Circulation. 2006;114(Suppl):I-108–13. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.000521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Menasche P. Stem cells for clinical use in cardiovascular medicine: current limitations and future perspectives. Thromb Haemost. 2005;94:697–701. doi: 10.1160/TH05-03-0218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Assmus B, Schachinger V, Teupe C, et al. Transplantation of Progenitor Cells and Regeneration Enhancement in Acute Myocardial Infarction (TOPCARE-AMI) Circulation. 2002;106:3009–17. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000043246.74879.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ince H, Petzsch M, Kleine HD, et al. Prevention of left ventricular remodeling with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor after acute myocardial infarction: final 1-year results of the Front-Integrated Revascularization and Stem Cell Liberation in Evolving Acute Myocardial Infarction by Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor (FIRSTLINE-AMI) trial. Circulation. 2005;112(Suppl):I-73–80. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.524827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schachinger V, Assmus B, Britten MB, et al. Transplantation of progenitor cells and regeneration enhancement in acute myocardial infarction: final one-year results of the TOPCARE-AMI trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:1690–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strauer BE, Brehm M, Zeus T, et al. Regeneration of human infarcted heart muscle by intracoronary autologous bone marrow cell transplantation in chronic coronary artery disease: the IACT Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:1651–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.01.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cleland JG, Freemantle N, Coletta AP, Clark AL. Clinical trials update from the American Heart Association: REPAIR-AMI, ASTAMI, JELIS, MEGA, REVIVE-II, SURVIVE, and PROACTIVE. Eur J Heart Fail. 2006;8:105–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meyer GP, Wollert KC, Lotz J, et al. Intracoronary bone marrow cell transfer after myocardial infarction: eighteen months' follow-up data from the randomized, controlled BOOST (BOne marrOw transfer to enhance ST-elevation infarct regeneration) trial. Circulation. 2006;113:1287–94. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.575118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Janssens S, Dubois C, Bogaert J, et al. Autologous bone marrow-derived stem-cell transfer in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;367:113–21. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67861-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lunde K, Solheim S, Aakhus S, Arnesen H, Abdelnoor M, Forfang K. Autologous stem cell transplantation in acute myocardial infarction: the ASTAMI randomized controlled trial. Intracoronary transplantation of autologous mononuclear bone marrow cells, study design and safety aspects. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2005;39:150–8. doi: 10.1080/14017430510009131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zohlnhofer D, Ott I, Mehilli J, et al. Stem cell mobilization by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in patients with acute myocardial infarction: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295:1003–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.9.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Penn MS. Stem-cell therapy after acute myocardial infarction: the focus should be on those at risk. Lancet. 2006;367:87–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67895-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hofmann M, Wollert KC, Meyer GP, et al. Monitoring of bone marrow cell homing into the infarcted human myocardium. Circulation. 2005;111:2198–202. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000163546.27639.AA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hou D, Youssef EAS, Brinton TJ, et al. Radiolabeled cell distribution after intramyocardial, intracoronary, and interstitial retrograde coronary venous delivery: implications for current clinical trials. Circulation. 2005;112(Suppl):I-150–6. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.526749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Welt FGP, Losordo DW. Cell therapy for acute myocardial infarction: curb your enthusiasm? Circulation. 2006;113:1272–4. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.613034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chien KR. Lost and found: cardiac stem cell therapy revisited. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1838–40. doi: 10.1172/JCI29050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Torella D, Ellison GM, Dellegrottaglie S. Testing regeneration of human myocardium without knowing the identity and the number of effective bone marrow cells transplanted: are the results meaningful? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:417. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wollert KC, Drexler H. Cell-based therapy for heart failure. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2006;21:234–9. doi: 10.1097/01.hco.0000221586.94490.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peters AM, Saverymuttu SH. The value of indium-labelled leucocytes in clinical practice. Blood Rev. 1987;1:65–76. doi: 10.1016/0268-960x(87)90021-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Vries IJ, Lesterhuis WJ, Barentsz JO, et al. Magnetic resonance tracking of dendritic cells in melanoma patients for monitoring of cellular therapy. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:1407–13. doi: 10.1038/nbt1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Acton PD, Zhou R. Imaging reporter genes for cell tracking with PET and SPECT. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2005;49:349–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cao F, Lin S, Xie X, et al. In vivo visualization of embryonic stem cell survival, proliferation, and migration after cardiac delivery. Circulation. 2006;113:1005–14. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.588954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meyer N, Jaconi M, Landopoulou A, Fort P, Puceat M. A fluorescent reporter gene as a marker for ventricular specification in ES-derived cardiac cells. FEBS Lett. 2000;478:151–8. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01839-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gruber PJ, Li Z, Li H, et al. In vivo imaging of mlc2v-luciferase, a cardiac-specific reporter gene expression in mice. Acad Radiol. 2004;11:1022–8. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2004.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harisinghani MG, Barentsz J, Hahn PF, et al. Noninvasive detection of clinically occult lymph-node metastases in prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2491–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stillman AE, Wilke N, Li D, Haacke M, McLachlan S. Ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide to enhance MRA of the renal and coronary arteries: studies in human patients. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1996;20:51–5. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199601000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lawaczeck R, Menzel M, Pietsch H. Superparamagnetic iron oxide particles: contrast media for magnetic resonance imaging. Appl Organometallic Chem. 2004;18:506–13. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bulte JW, Duncan ID, Frank JA. In vivo magnetic resonance tracking of magnetically labeled cells after transplantation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22:899–907. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200208000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Magnitsky S, Watson DJ, Walton RM, et al. In vivo and ex vivo MRI detection of localized and disseminated neural stem cell grafts in the mouse brain. Neuroimage. 2005;26:744–54. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hoehn M, Kustermann E, Blunk J, et al. Monitoring of implanted stem cell migration in vivo: a highly resolved in vivo magnetic resonance imaging investigation of experimental stroke in rat. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16267–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242435499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Garot J, Unterseeh T, Teiger E, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of targeted catheter-based implantation of myogenic precursor cells into infarcted left ventricular myocardium. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1841–6. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00414-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Himes N, Min JY, Lee R, et al. In vivo MRI of embryonic stem cells in a mouse model of myocardial infarction. Magn Reson Med. 2004;52:1214–9. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kustermann E, Roell W, Breitbach M, et al. Stem cell implantation in ischemic mouse heart: a high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging investigation. NMR Biomed. 2005;18:362–70. doi: 10.1002/nbm.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moore A, Grimm J, Han B, Santamaria P. Tracking the recruitment of diabetogenic CD8+ T-cells to the pancreas in real time. Diabetes. 2004;53:1459–66. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.6.1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moore A, Sun PZ, Cory D, Hogemann D, Weissleder R, Lipes MA. MRI of insulitis in autoimmune diabetes. Magn Reson Med. 2002;47:751–8. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Frank JA, Miller BR, Arbab AS, et al. Clinically applicable labeling of mammalian and stem cells by combining superparamagnetic iron oxides and transfection agents. Radiology. 2003;228:480–7. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2281020638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yeh TC, Zhang W, Ildstad ST, Ho C. Intracellular labeling of T-cells with superparamagnetic contrast agents. Magn Reson Med. 1993;30:617–25. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910300513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rogers WJ, Basu P. Factors regulating macrophage endocytosis of nanoparticles: implications for targeted magnetic resonance plaque imaging. Atherosclerosis. 2005;178:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van den Bos EJ, Wagner A, Mahrholdt H, et al. Improved efficacy of stem cell labeling for magnetic resonance imaging studies by the use of cationic liposomes. Cell Transplant. 2003;12:743–56. doi: 10.3727/000000003108747352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Arbab AS, Yocum GT, Kalish H, et al. Efficient magnetic cell labeling with protamine sulfate complexed to ferumoxides for cellular MRI. Blood. 2004;104:1217–23. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lewin M, Carlesso N, Tung CH, et al. Tat peptide-derivatized magnetic nanoparticles allow in vivo tracking and recovery of progenitor cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:410–4. doi: 10.1038/74464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Reynolds F, Weissleder R, Josephson L. Protamine as an efficient membrane-translocating peptide. Bioconjug Chem. 2005;16:1240–5. doi: 10.1021/bc0501451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ahrens ET, Feili-Hariri M, Xu H, Genove G, Morel PA. Receptor-mediated endocytosis of iron-oxide particles provides efficient labeling of dendritic cells for in vivo MR imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2003;49:1006–13. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fawell S, Seery J, Daikh Y, et al. Tat-mediated delivery of heterologous proteins into cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:664–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.2.664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Arbab AS, Wilson LB, Ashari P, Jordan EK, Lewis BK, Frank JA. A model of lysosomal metabolism of dextran coated superparamagnetic iron oxide (SPIO) nanoparticles: implications for cellular magnetic resonance imaging. NMR Biomed. 2005;18:383–9. doi: 10.1002/nbm.970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hinds KA, Hill JM, Shapiro EM, et al. Highly efficient endosomal labeling of progenitor and stem cells with large magnetic particles allows magnetic resonance imaging of single cells. Blood. 2003;102:867–72. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-12-3669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Arbab AS, Bashaw LA, Miller BR, et al. Characterization of biophysical and metabolic properties of cells labeled with superpara-magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles and transfection agent for cellular MR imaging. Radiology. 2003;229:838–46. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2293021215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kostura L, Kraitchman DL, Mackay AM, Pittenger MF, Bulte JW. Feridex labeling of mesenchymal stem cells inhibits chondrogenesis but not adipogenesis or osteogenesis. NMR Biomed. 2004;17:513–7. doi: 10.1002/nbm.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Arbab AS, Yocum GT, Rad AM, et al. Labeling of cells with ferumoxides-protamine sulfate complexes does not inhibit function or differentiation capacity of hematopoietic or mesenchymal stem cells. NMR Biomed. 2005;18:553–9. doi: 10.1002/nbm.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Walczak P, Kedziorek DA, Gilad AA, Lin S, Bulte JW. Instant MR labeling of stem cells using magnetoelectroporation. Magn Reson Med. 2005;54:769–74. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bangs LB. New developments in particle-based immunoassays: introduction. Pure Appl Chem. 1996;68:1873–9. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shapiro EM, Skrtic S, Sharer K, Hill JM, Dunbar CE, Koretsky AP. MRI detection of single particles for cellular imaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10901–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403918101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wu YL, Ye Q, Foley LM, et al. In situ labeling of immune cells with iron oxide particles: an approach to detect organ rejection by cellular MRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:1852–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507198103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hill JM, Dick AJ, Raman VK, et al. Serial cardiac magnetic resonance imaging of injected mesenchymal stem cells. Circulation. 2003;108:1009–14. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000084537.66419.7A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stroh A, Faber C, Neuberger T, et al. In vivo detection limits of magnetically labeled embryonic stem cells in the rat brain using high-field (17.6 T) magnetic resonance imaging. Neuroimage. 2005;24:635–45. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Heyn C, Ronald JA, Mackenzie LT, et al. In vivo magnetic resonance imaging of single cells in mouse brain with optical validation. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55:23–9. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cohen B, Dafni H, Meir G, Harmelin A, Neeman M. Ferritin as an endogenous MRI reporter for noninvasive imaging of gene expression in C6 glioma tumors. Neoplasia. 2005;7:109–17. doi: 10.1593/neo.04436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Genove G, Demarco U, Xu H, Goins WF, Ahrens ET. A new transgene reporter for in vivo magnetic resonance imaging. Nat Med. 2005;11:450–4. doi: 10.1038/nm1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Weissleder R, Moore A, Mahmood U, et al. In vivo magnetic resonance imaging of transgene expression. Nat Med. 2000;6:351–5. doi: 10.1038/73219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Moore A, Josephson L, Bhorade RM, Basilion JP, Weissleder R. Human transferrin receptor gene as a marker gene for MR imaging. Radiology. 2001;221:244–50. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2211001784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Deans AE, Wadghiri YZ, Bernas LM, et al. Cellular MRI contrast via coexpression of transferrin receptor and ferritin. Magn Reson Med. 2006;56:51–9. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tweedle MF. The ProHance story: the making of a novel MRI contrast agent. Eur Radiol. 1997;7 5:225–30. doi: 10.1007/pl00006897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Aime S, Cabella C, Colombatto S, Geninatti Crich S, Gianolio E, Maggioni F. Insights into the use of paramagnetic Gd(III) complexes in MR-molecular imaging investigations. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2002;16:394–406. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Aime S, Barge A, Cabella C, Crich SG, Gianolio E. Targeting cells with MR imaging probes based on paramagnetic Gd(III) chelates. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2004;5:509–18. doi: 10.2174/1389201043376580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Conner SD, Schmid SL. Regulated portals of entry into the cell. Nature. 2003;422:37–44. doi: 10.1038/nature01451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Terreno E, Geninatti Crich S, et al. Effect of the intracellular localization of a Gd-based imaging probe on the relaxation enhancement of water protons. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55:491–7. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zheng Q, Dai H, Merritt ME, Malloy C, Pan CY, Li WH. A new class of macrocyclic lanthanide complexes for cell labeling and magnetic resonance imaging applications. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:16178–88. doi: 10.1021/ja054593v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ahrens ET, Flores R, Xu H, Morel PA. In vivo imaging platform for tracking immunotherapeutic cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:983–7. doi: 10.1038/nbt1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Chen J, Crowder K, Brant J, Lanza GM, Wickline SA. Fluorine diffusion measurements confirm intracellular labeling of perflurocarbon nanoparticles in therapeutic stem/progenitor cells as tracking agents. Proc Int Soc Magn Reson. 2006;14:359. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chen J, Crowder K, Brant J, et al. Labeling and imaging stem/progenitor cells with multiple unique nanoparticulate fluorine markers: the potential for multispectral stem cell detection with 19F MRI (abstr) Proc Int Soc Magn Reson. 2006;14:187. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Massoud TF, Gambhir SS. Molecular imaging in living subjects: seeing fundamental biological processes in a new light. Genes Dev. 2003;17:545–80. doi: 10.1101/gad.1047403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yang Y, Rendig S, Siegel S, Newport DF, Cherry SR. Cardiac PET imaging in mice with simultaneous cardiac and respiratory gating. Phys Med Biol. 2005;50:2979–89. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/50/13/001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chatziioannou AF, Cherry SR, Shao Y, et al. Performance evaluation of microPET: a high-resolution lutetium oxyorthosilicate PET scanner for animal imaging. J Nucl Med. 1999;40:1164–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Weber DA, Ivanovic M. Ultra-high-resolution imaging of small animals: implications for preclinical and research studies. J Nucl Cardiol. 1999;6:332–44. doi: 10.1016/s1071-3581(99)90046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Acton PD, Kung HF. Small animal imaging with high resolution single photon emission tomography. Nucl Med Biol. 2003;30:889–95. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(03)00112-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yang Y, Tai YC, Siegel S, et al. Optimization and performance evaluation of the microPET II scanner for in vivo small-animal imaging. Phys Med Biol. 2004;49:2527–45. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/49/12/005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Surti S, Karp JS, Perkins AE, et al. Imaging performance of A-PET: a small animal PET camera. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2005;24:844–52. doi: 10.1109/tmi.2005.844078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Liu Z, Kastis GA, Stevenson GD, et al. Quantitative analysis of acute myocardial infarct in rat hearts with ischemia-reperfusion using a high-resolution stationary SPECT system. J Nucl Med. 2002;43:933–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wu MC, Gao DW, Sievers RE, et al. Pinhole single-photon emission computed tomography for myocardial perfusion imaging of mice. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:576–82. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00716-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Acton PD, Thomas D, Zhou R. Quantitative imaging of myocardial infarct in rats with high resolution pinhole SPECT. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2006;22:429–34. doi: 10.1007/s10554-005-9046-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Roddie ME, Peters AM, Danpure HJ, et al. Inflammation: imaging with Tc-99m HMPAO-labeled leukocytes: clinical experience with 99mTc-hexamethylpropylene-amineoxime for labeling leucocytes and imaging inflammation. Radiology. 1988;166:767–72. doi: 10.1148/radiology.166.3.3340775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Adonai N, Nguyen KN, Walsh J, et al. Ex vivo cell labeling with 64Cu-pyruvaldehyde-bis(N4-methylthiosemicarbazone) for imaging cell trafficking in mice with positron-emission tomography. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:3030–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052709599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Aicher A, Brenner W, Zuhayra M, et al. Assessment of the tissue distribution of transplanted human endothelial progenitor cells by radioactive labeling. Circulation. 2003;107:2134–9. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000062649.63838.C9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Chin BB, Nakamoto Y, Bulte JW, Pittenger MF, Wahl R, Kraitchman DL. 111In oxine labeled mesenchymal stem cell SPECT after intravenous administration in myocardial infarction. Nucl Med Commun. 2003;24:1149–54. doi: 10.1097/00006231-200311000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Brenner W, Aicher A, Eckey T, et al. 111In-labeled CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells in a rat myocardial infarction model. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:512–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Zhou R, Thomas DH, Qiao H, et al. In vivo detection of stem cells grafted in infarcted rat myocardium. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:816–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kraitchman DL, Tatsumi M, Gilson WD, et al. Dynamic imaging of allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells trafficking to myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2005;112:1451–61. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.537480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Jin Y, Kong H, Stodilka RZ, et al. Determining the minimum number of detectable cardiac-transplanted 111In-tropolone-labelled bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells by SPECT. Phys Med Biol. 2005;50:4445–55. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/50/19/001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Barbash IM, Chouraqui P, Baron J, et al. Systemic delivery of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells to the infarcted myocardium: feasibility, cell migration, and body distribution. Circulation. 2003;108:863–8. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000084828.50310.6A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Shen D, Liu D, Cao Z, Acton PD, Zhou R. Co-registration of MR and SPECT images for non-invasive localization of stem cells grafted in the infarcted rat myocardium. Mol Imaging Biol. 2006 doi: 10.1007/s11307-006-0062-3. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ray P, Bauer E, Iyer M, et al. Monitoring gene therapy with reporter gene imaging. Semin Nucl Med. 2001;31:312–20. doi: 10.1053/snuc.2001.26209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Gambhir SS, Bauer E, Black ME, et al. A mutant herpes simplex virus type 1 thymidine kinase reporter gene shows improved sensitivity for imaging reporter gene expression with positron emission tomography. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:2785–90. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.6.2785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]