Abstract

The glycan determinant Lewis x (Lex/CD15) is a distinguishing marker for human myeloid cells and mediates neutrophil adhesion to dendritic cells. Despite broad interest in this structure, the mechanism(s) underlying Lex/CD15 expression remain relatively uncharacterized. Accordingly, we investigated the molecular basis of increasing Lex/CD15 expression associated with human myeloid cell differentiation. Flow cytometric analysis of differentiating cells together with biochemical studies employing inhibitors of glycan synthesis and of sialidases showed that increased Lex/CD15 expression was not due to de novo biosynthesis of Lex/CD15, but resulted predominantly from induction of α(2,3) sialidase activity, yielding Lex/CD15 from cell surface sLex/CD15s. This differentiation-associated conversion of surface sLex/CD15s to Lex/CD15 occurs predominantly on glycoproteins. Heretofore, modulation of post-translational glycan modifications has been attributed solely to dynamic variation(s) in glycosyltransferase expression. Our results unveil a new paradigm, demonstrating a critical role for post-Golgi membrane glycosidase activity in the “biosynthesis” of a key glycan determinant.

The Lewis x (Lex) antigen, or CD15, is a cell surface glycan consisting of a trisaccharide with the structure Galβ1-4[Fucα1-3]GlcNAc. Initially identified by monoclonal antibodies in the early 1980’s, it was quickly appreciated as a useful marker for human myeloid differentiation1,2, in particular, in identifying granulocyte-series cells. Otherwise known as “the stage-specific embryonic antigen-1” (SSEA-1 antigen), Lex/CD15 also serves as a marker of murine embryonic stem cells3 and of murine mesenchymal stem cells4. Lex/CD15 is related to another structure, sialyl-Lewis x (NeuNAcα2-3Galβ1-4[Fucα1-3]GlcNAc; sLex/CD15s, where “s” refers to “sialylated”), which differs only by the addition of a sialic acid (N-acetyl-neuraminic acid, NeuNAc) in α2,3)-linkage to the galactose in the core Lex trisaccharide5,6. Though apparently subtle, this sialylation has profound implications for immunoreactivity and biologic functions. Although bearing a common trisaccharide core, antibodies to sLex/CD15s do not recognize Lex/CD15, and visa versa. Identification of sLex/CD15s with mAbs such as HECA-452 has been useful in defining subsets of cells that bind E-selectin and display specialized tissue migration patterns, such as dermatotropic lymphocytes7,8 and osteotropic stem cells9,10. Early studies of hematopoietic differentiation showed that expression of the sLex determinant is associated with the most primitive subset of the resident bone marrow cells in humans and that myeloid maturation is accompanied by relative loss of sLex/CD15s and gain of Lex/CD15 expression11,12. These results suggested that, within the bone marrow microenvironment, partitioning of sLex/CD15s and Lex/CD15 expression on immature cells may also have significance in the creation of “hematopoietic niches”. Similarly, upregulation of Lex/CD15 expression on neutrophils has been implicated in modulating innate and/or adoptive immune responses via engagement to the dendritic cell-specific ICAM-3-grabbing nonintegrin (DC-SIGN)13,14.

Despite keen interest in the Lex/CD15 determinant, the molecular regulation of its expression has not been fully elucidated. For essentially all cell surface glycans described to date, expression has been shown to be secondary to induction of specific glycosyltransferases within the endoplasmic reticulum and/or Golgi apparatus15-17. Although surface display of Lex/CD15 has been attributed to transcriptional upregulation of pertinent glycosyltransferases17, the reciprocal variations in sLex/CD15s and Lex/CD15 expression observed in myeloid cell differentiation18,19 prompted us to examine the mechanism(s) regulating membrane expression of these glycans (Fig. 1). For this purpose, we exploited two models of differentiation, one based on the capacity of anti-CD44 mAbs to induce maturation of myeloid leukemic cells20,21 and the other on G-CSF-induced differentiation of native hematopoietic progenitor cells. In both models, our studies revealed that the maturation-associated increases in Lex/CD15 expression are conferred predominantly by induction of cell surface sialidase activity with resultant cleavage of α(2,3)-linked sialic acid, yielding Lex/CD15 from sLex/CD15s. This transformation occurs predominantly on glycoproteins, including two sialomucins serving as selectin ligands, PSGL-18,22 and CD4323,24. These findings offer new perspectives on the molecular basis of glycan expression, revealing that stage-specific cropping of “mature” membrane glycans yields “new” epitopes, highlighting a key role for dynamic induction of post-Golgi glycosidase(s) in the regulation of cell surface carbohydrate decorations.

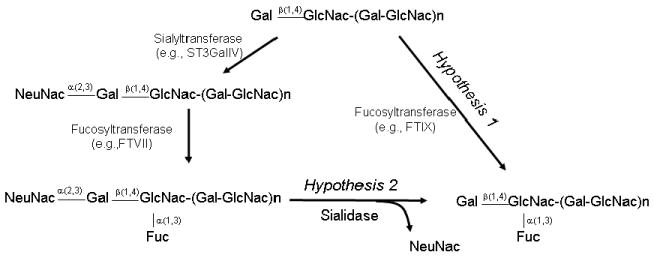

Figure 1. Hypotheses for increased CD15/Lex expression during myeloid differentiation.

Structures are shown in schematic, with relevant chemical steps (arrows) for synthesis of sLex/CD15s and Lex/CD15. Note that the two hypotheses are non-mutually exclusive.

Results

CD44 ligation increases Lex and decreases sLex expression

Prior studies have shown that anti-CD44 mAbs induce differentiation of leukemic cell lines and primary AML blasts20,21. Using this model of induced maturation to investigate Lex/CD15 expression, we cultured HL60 cells and primary AML blasts in presence of anti-CD44 mAb Hermes-1, without mAb, or with isotype control mAb for 72h. CD44 mAb treatment resulted in morphologic changes characteristic of granulocytic differentiation: nuclear condensation and lobulation, increased cytoplasmic granules, and increased cytoplasm-to-nuclear ratio (Supplementary Fig. 1). Anti-CD44 mAb treatment significantly increased Lex/CD15 expression (consistently > 40% increase in Mean Fluorescence Intensity (MFI)) in both HL60 (Fig. 2a, groups 1 and 2; Supplementary Fig. 2) and primary AML cells (Fig. 2b, groups 1 and 2). In all experiments, no changes in morphology nor in Lex/CD15 or sLex/CD15s expression levels were observed between precultured cells (on day 0), compared with cultured untreated or isotype mAb-treated cells on day 3.

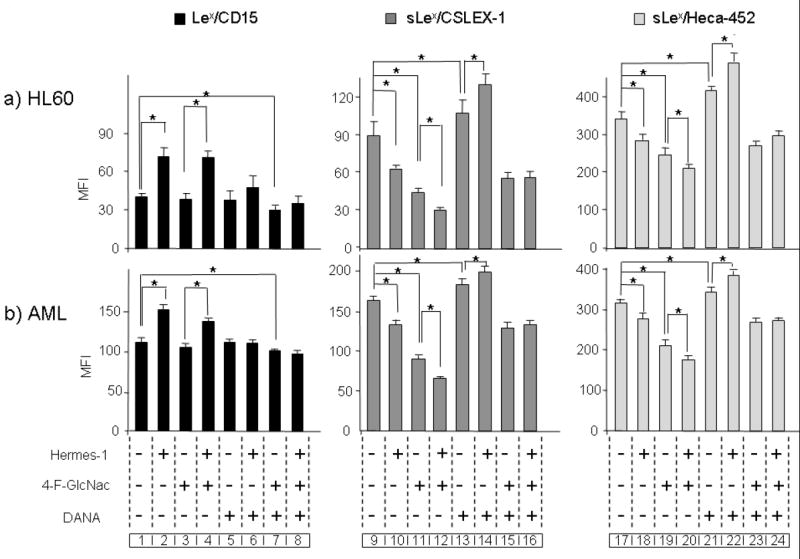

Figure 2. CD44 ligation-induced changes in expression of sLex/CD15s and Lex/CD15.

(a) HL60 cells and (b) primary AML blasts (n=5) were treated with Hermes-1 for 72h in the presence (+) or absence (-) of 4-F-GlcNAc, and/or of DANA. Expression of Lex/CD15 and sLex/CD15s was determined by flow cytometry. (b) is one representative experiment out of 5 AML specimens with analysis in triplicate cultures. Statistical significance (p≤ 0.05) for respective comparison groups is shown by brackets and asterisk.

Using the sLex/CD15s-specific mAb CSLEX-125 to quantify expression of this determinant, we found that increased expression of Lex/CD15 following anti-CD44 mAb-induced myeloid differentiation was accompanied by a decrease in sLex/CD15s levels (Fig. 2a and b, groups 9 and 10; Supplementary Fig. 2); similar results were obtained using mAb HECA-452 (Fig. 2a and b, groups 17 and 18), which recognizes a sLex-like epitope. As with Lex/CD15, incubation of cells with isotype control mAb did not change sLex/CD15s expression (data not shown). The reciprocal changes in Lex/CD15 and sLex/CD15s expression associated with myeloid differentiation prompted us to test two non-mutually exclusive processes that could account for this observation: (1) preferential neo-synthesis of the Lex epitope with concurrent decreased sLex production and/or (2) de-sialylation of cell surface sLex determinants (Fig. 1).

Lactosamine synthesis is not required for increased Lex

To assess whether increased Lex/CD15 expression during CD44-induced differentiation resulted from de novo synthesis, cells were treated with anti-CD44 mAb in the presence of 2-acetamido-1,3,6-tri-O-acetyl-4-fluoro-D-glucopyranose (4-F-GlcNAc, 1). 4-F-GlcNAc incorporates into poly-N-acetyl-lactosamine chains and blocks the formation of neo-synthesized Lex and sLex epitopes: the non-nucleophilic fluorine substitution at the 4-position of GlcNAc terminates polylactosamine synthesis without interfering with homeostatic pathways of protein synthesis and cell growth7. Insofar as all α(2,3)-sialyltransferase enzymes are confined to the Golgi apparatus26, α(2,3)-sialyllactosamine-bearing membrane molecules require intracellular assembly of nascent lactosamine scaffolds. We thus first assessed the inhibitory effect of 4-F-GlcNAc on polylactosamine synthesis on HL60 and AML cells by measuring the recovery of sLex/CD15s expression following sialidase treatment of these cells cultured in the presence or absence of this agent. As previously observed in non-myeloid cells following sialidase treatment7, sLex/CD15s re-expression was markedly diminished in the presence of 4-F-GlcNAc compared to control cells (return of sLex/CD15s consistently < 15% of media control), indicating that 4-F-GlcNAc blunted de novo polylactosamine synthesis required for expression of sLex/CD15s. HL60 and AML blasts were thus cultured with or without anti-CD44 mAbs for 3 days, in the presence or absence of 4-F-GlcNAc. Incubation with 4-F-GlcNAc alone (i.e., in the absence of anti-CD44 mAb treatment) significantly diminished the expression of sLex/CD15s on all cells (Fig. 2a and b, groups 11 and 19; Supplementary Fig. 2) without appreciable effects on Lex/CD15 levels (Fig. 2a and b, group 3; Supplementary Fig. 2), indicating that steady-state synthesis and surface turnover of sLex/CD15s is greater than that of Lex/CD15. Consistent with these results, Hermes-1-associated decreased expression of sLex/CD15s was greater in the presence of 4-F-GlcNAc than that observed with Hermes-1 alone (Fig. 2a and b, groups 11 and 12, and groups 19 and 20; Supplementary Fig. 2). However, when used in combination with Hermes-1, 4-F-GlcNAc did not dampen the increase of Lex/CD15 induced by the anti-CD44 mAb (Fig. 2a and b, compare groups 2, 3 and 4; Supplementary Fig. 2), indicating that the CD44-mediated increase of Lex/CD15 does not require de novo polylactosamine synthesis. Notably, RT-PCR analysis of glycosyltransferases creating sLex-specific modifications (ST3GalIV and FTVII) showed no decrease in transcripts following anti-CD44 treatment, indicating that the observed decrease in sLex/CD15s display was not a consequence of diminished gene expression for such enzymes. Importantly, there was also no appreciable increase in transcripts encoding fucosyltransferases directing Lex/CD15 expression, FTIV and FTIX16, during differentiation induced by anti-CD44 mAbs (Supplementary Fig. 3). Thus, the observed differences in Lex/CD15 and sLex/CD15s were not accompanied by altered gene expression of relevant enzymes that fucosylate terminal lactosamines critical for synthesis of respective glycans17.

Sialidase inhibition blunts increased Lex expression

To assess the contribution of α(2,3) sialidases to the observed increase in Lex/CD15 expression, we inhibited the activity of these enzymes using the potent sialidase inhibitor 2,3-dehydro-2-deoxy-N-Acetyl-neuraminic acid (DANA, 2)27. HL60 cells and AML blasts were treated with anti-CD44 mAbs in the absence or presence of 100 μM DANA and expression of Lex/CD15 and sLex/CD15s was analyzed by flow cytometry. As shown in Figure 2a and b, treatment of cells with DANA significantly abrogated the anti-CD44-induced changes in Lex/CD15 (Fig. 2a and b, compare group 2 to group 6; Supplementary Fig. 2 and sLex/CD15s (Fig. 2a and b compare group 10 to group 14, supplementary Fig. 2 (for CSLEX-1); and group 18 to group 22 (for HECA-452)), indicating that the increased Lex/CD15 and decreased sLex/CD15s expression during myeloid differentiation is sialidase-dependent. Importantly, in the presence of DANA, Hermes-1 treatment induced a slight increase in sLex/CD15s (Fig. 2a and b, compare groups 13 and 14, and groups 21 and 22; Supplementary Fig. 2). Taken together, these results indicate that both sLex/CD15s synthesis and sialidase activity are induced by CD44 ligation, but the increase in sialidase activity dominates, such that the overall expression pattern upon CD44 ligation is a decrease in sLex/CD15s expression with an accompanying increase in Lex/CD15. Consistent with these findings, the CD44 mAb-induced increase in sLex/CD15s in the presence of DANA (Fig. 2a and b, group 14, Supplementary Fig. 2) for CSLEX-1; and group 22 for HECA-452) was abrogated when 4-F-GlcNAc was used simultaneously with anti-CD44 treatment (group 16 for CSLEX-1, and group 24 for HECA-452). Collectively, these data indicate that Lex/CD15 does not undergo heightened synthesis or degradation coincident with differentiation, and exclude a role for the addition of sialic acid onto the core trisaccharide (by action of sialyltransferases) in the creation of sLex/CD15s.

CD44 ligation increases sialidase activity

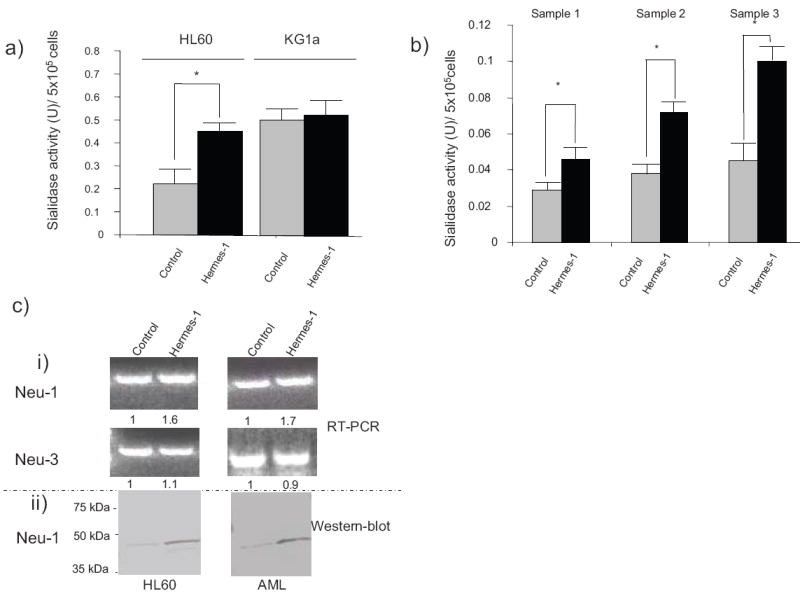

To directly analyze whether CD44-ligation modulates sialidase activity in AML cells, we measured degradation of the exogenous sialidase substrate 2′-(4-Methylumbelliferyl-N-acetyl-α-D-neuraminic Acid) (4MU-NANA, 3)28-30. Cells were treated with Hermes-1 for 48 h prior to measurement of sialidase activity. Cell viability (measured by propidium iodide incorporation and trypan blue exclusion) was preserved. As shown in Figure 3a and b, Hermes-1 induced a significant increase in the surface sialidase activity of HL60 cells and of AML blasts obtained from 3 different donors. These findings provide direct evidence that CD44-induced differentiation causes the elaboration of sialidase(s) that is (are) responsible for the modulation of Lex/CD15 level by converting sLex/CD15s into Lex/CD15. Consistent with this result, treatment of KG1a cells, a human leukemia cell line that does not differentiate with CD44 ligation20, does not induce Lex/CD15 expression nor morphologic changes, and there is no associated increase in sialidase activity (Fig. 3a). Importantly, increased sialidase expression appears to be a consequence of differentiation and not a precipitant for differentiation, as direct addition of α(2,3) sialidases (from either Vibrio Cholerae or Streptococcus Pneumonia) to cultures of leukemia cells and of mobilized hematopoeitic progenitors results in (expected) marked increases in Lex/CD15 and decreases in sLex/CD15s expression (by MFI, consistently >5-fold increase in Lex/CD15 expression and >80% decrease in sLex/CD15s), without inducing any morphologic changes (data not shown). Though four distinct sialidases have been described in mammalian cells (Neu-1 to Neu-4)28-30,31-33 , only Neu-1 and Neu-3 can hydrolyze 4MU-NANA28-30,31,33. To assess whether the increased sialidase activity reflected changes in expression of these enzymes, RT-PCR analysis of transcripts encoding these products was performed. Treatment of HL60 cells with Hermes-1 for 48hrs was associated with increased Neu-1 transcript levels and no change in Neu-3 [Fig. 3c (i)]. Consistent with these findings, western blot analysis showed increased levels of Neu-1 protein for both HL60 and AML blasts [Fig. 3c (ii)], but no changes in Neu-3 were observed.

Figure 3. CD44 ligation increases sialidase activity on myeloid cells.

Cell surface sialidase activity was measured using 4-MU-NANA as substrate on (a) HL60 and KG1a cells, and (b) AML cells from patients (samples 1, 2 and 3), cultured in the presence or absence of Hermes-1 for 48h. Statistical significance (p≤ 0.05) for respective comparison groups is shown by brackets and asterisk. (c) (i): Representative ethidium bromide–stained gels of PCR-amplified RNA encoding sialidases Neu-1 and Neu-3 from HL60 cells and AML blasts treated with isotype-matched mAb (control) or Hermes-1 (48h treatment). Numbers indicate the relative expression of RT-PCR product normalized against GAPDH control.

(ii): Western-blot analysis of Neu-1 protein expression in HL60 cells and AML blasts treated with isotype mAb (control) or Hermes-1 (48h treatment).

CD44-induced Lex/CD15 expression occurs on glycoproteins

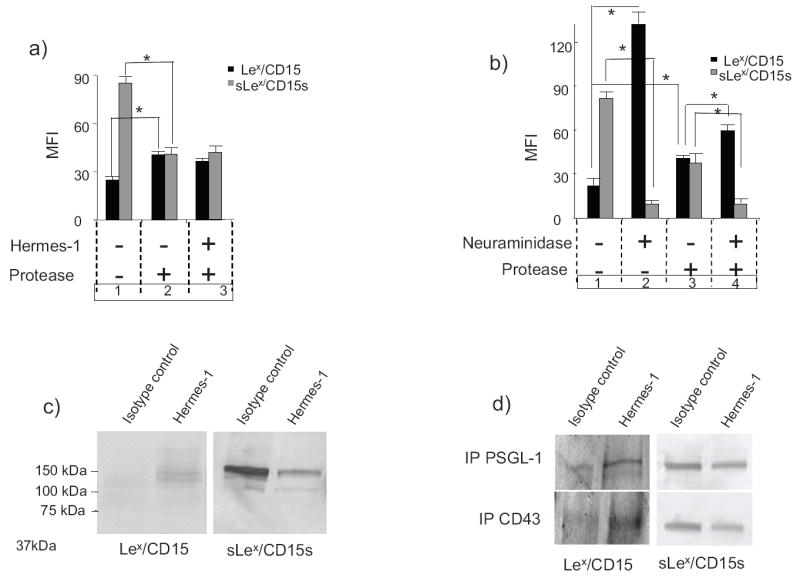

Since Lex/CD15 and sLex/CD15s determinants are present on both glycoproteins and glycoplipids34, and both are potential targets of human sialidases, we sought to determine their relative contribution to the increase of Lex/CD15 and the decrease of sLex/CD15s induced by CD44 mAbs. Two overlapping experimental approaches were taken. In the first set of experiments, HL60 cells untreated or treated with Hermes-1 for 72h were digested with bromelain to cleave surface proteins immediately before flow cytometric analysis of Lex/CD15 and sLex/CD15s levels (Fig. 4a). The efficacy of protein digestion was confirmed by a lack of CD44 expression in the bromelain treated cells compared to control cells. We observed that bromelain treatment on HL60 cells, in the absence of Hermes-1, resulted in paradoxically increased MFI for Lex/CD15 (compare groups 1 and 2), indicating that membrane proteins natively shield display of prominent glycolipid expression of Lex/CD15; the contrary is true for sLex/CD15s, which is markedly diminished following bromelain digestion, indicating dominance of glycoprotein expression of sLex/CD15s (compare groups 1 and 2). To exclude the possibility that these results reflect sialidase contamination of bromelain, we treated cells first with a different protease, proteinase K, and measured Lex/CD15 and sLex/CD15s levels. Subsequent treatment with bromelain showed no further changes in either Lex/CD15 or sLex/CD15s levels. Following protease digestion in the absence of (group 2) or following (group 3) anti-CD44 mAb treatment, there was no difference in membrane Lex/CD15 levels nor in sLex/CD15s levels. Thus, anti-CD44 mAb-induced differentiation does not alter sLex displayed on glycolipids and does not increase Lex/CD15 displayed on glycolipids as measured by flow cytometry.

Figure 4. CD44 ligation increases Lex/CD15 and decreases sLex/CD15s expression on glycoproteins of myeloid cells.

(a) HL60 cells were first cultured with Hermes-1 (+) or isotype control mAb (-) for 72h, then treated with protease (bromelain) (+) or buffer alone (-) immediately before flow cytometric analysis of Lex/CD15 and sLex/CD15s expression. (b) HL60 cells were treated with neuraminidase (+) and/or protease (+) or buffer (-), respectively, before flow cytometric analysis of Lex/CD15 and sLex/CD15s expression. Statistical significance (p≤ 0.05) for comparison groups in (a) and (b) is shown by brackets and asterisks. (c) Western blot analysis of Lex/CD15 and sLex/CD15s expression on HL60 cells treated with isotype control mAb or Hermes-1. (d) Western blot analysis of Lex/CD15 and sLex/CD15s expression on PSGL-1 and CD43 immunoprecipitated from HL60 cells treated with isotype control mAb or Hermes-1. For each experiment, one representative of three is shown.

In the second series of experiments, HL60 cells were treated with exogenous sialidase (V. Cholera neuraminidase at 0.1U/mL). As expected, this treatment resulted in an almost complete abrogation of sLex/CD15s expression on intact cells, with a commensurate profound increase in Lex/CD15 expression (almost 6 fold) (Fig. 4b, groups 1 and 2). To analyze the contribution of membrane glycolipids to the observed increase in Lex/CD15 expression, HL60 cells were digested with bromelain following sialidase treatment; as shown in Fig. 4b (group 2 and 4), sLex expression on bromelain-resistant scaffolds was diminished similar to that of intact cells, indicating that native membrane glycolipids are accessible to exogenous sialidase digestion. However, the associated increase of Lex/CD15 levels on glycolipids is modest (1.4-fold) compared to that observed on intact cells (~6-fold). Collectively, these results show that although both membrane glycoproteins and glycolipids are substrates of exogenous sialidase, the observed increase in Lex/CD15 results predominantly via conversion of sLex/CD15s to Lex/CD15 on glycoproteins.

To examine this issue further, Western blot analysis of Lex/CD15 and sLex/CD15s expression was performed on cell lysates from cells treated with Hermes-1 or isotype mAb (control). Anti-CD44 treatment increases Lex/CD15 expression on multiple glycoproteins, prominently at 130 and 150 kDa, confirming the results of protease studies (Fig. 4c). This increase of Lex/CD15 was accompanied by a decrease in sLex/CD15s on glycoproteins of similar molecular weight (Fig. 4c). Two glycoproteins known to bear sLex substitutions, PSGL-18,22 and CD4323,24, migrate on SDS/PAGE within a 130-150 kDa range. To examine whether these membrane proteins are targets of sialidase digestion, PSGL-1 and CD43 were immunoprecipitated from cell lysates of HL60 before and after anti-CD44 mAb treatment, and western blot analysis was performed using Heca-452 and anti-CD15 mAb. Lex/CD15 expression increases on both PSGL-1 and CD43 after anti-CD44 treatment (Fig 4d). Concomitant with this increase, there was a decrease of sLex/CD15s expression on each of these proteins.

G-CSF increases sialidase activity in myeloid progenitors

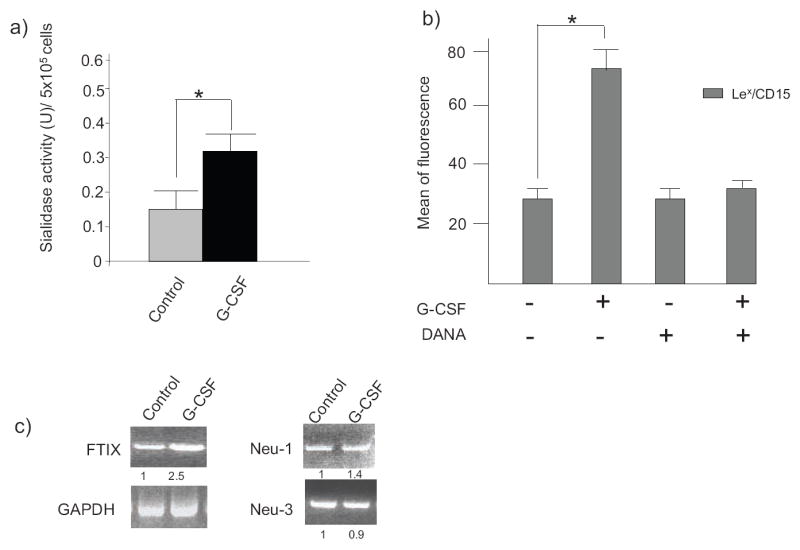

To determine whether conversion of sLex/CD15s into Lex/CD15 by sialidases occurs during differentiation of native myeloid progenitors, immature myeloid cells were obtained from human bone marrow. We compared sialidase activity on myeloid cells before and after treatment with G-CSF. As shown in Fig. 5a, myeloid cells express a ~2-fold increase in sialidase activity after 72h of treatment with G-CSF, coincident with an increase in Lex/CD15 expression (Fig. 5b) and with morphological changes of differentiation (data not shown). Moreover, increased Lex/CD15 expression was blunted by the use of DANA (Fig. 5b), showing the important role played by sialidases in the creation of Lex/CD15 displayed during native myeloid differentiation. Altogether, these data indicate that conversion of immature to mature phenotypes among native myeloid cells is dynamically associated with induction of surface sialidase activity. In keeping with these findings, we observed an increase in transcripts encoding Neu-1 coincident with myeloid differentiation (Fig. 5c).

Figure 5. G-CSF treatment increases sialidase activity on myeloid cells.

(a) Sialidase activity was measured from myeloid progenitor cells, before (control) and after treatment ex-vivo with G-CSF for 72h. (b) Expression of Lex/CD15 of native progenitor cells untreated (-) or treated (+) with G-CSF for 72h and in the presence (+) or absence (-) of DANA was determined by flow cytometry using anti-CD15 mAb. One representative experiment out of three specimens with analysis in triplicate cultures is shown. (c) Typical ethidium bromide–stained gels of PCR-amplified RNA from human hematopoietic progenitor cells with or without (control) G-CSF treatment. Numbers indicate the relative expression of RT-PCR product normalized against GAPDH control.

Discussion

In this study, we sought to determine the molecular mechanism(s) regulating increased expression of Lex/CD15 associated with human myeloid cell differentiation. To date, augmented expression of membrane carbohydrate determinants has been shown to be secondary to induction of specific glycosyltransferases within the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus15-17. Our data indicate, for the first time, that post-Golgi enzymatic glycoside hydrolysis is the predominant mechanism for the enhanced expression of a key cell surface glycan determinant.

The sLex and Lex structures consist of monosaccharide substitutions on a common lactosamine core. We utilized a specific inhibitor of lactosamine synthesis, 4-F-GlcNAc, to define the contribution of de novo glycan synthesis to expression of both Lex/CD15 and sLex/CD15s during myeloid differentiation. CD44 ligation had no effect on Lex/CD15 and sLex/CD15s levels when sialidase and lactosamine synthesis were inhibited simultaneously, demonstrating the importance of lactosamine synthesis for creation of sLex/CD15s and excluding a role for addition of sialic acid onto the core trisaccharide. Additionally, there was no significant change in the expression of fucosyltransferases FucTIV and of FucTIX, indicating that the increase in Lex/CD15 associated with myeloid differentiation did not result from augmented levels of these fucosyltransferases directing Lex/CD15 synthesis17. Collectively, our data show that during anti-CD44-induced myeloid differentiation, both sLex/CD15s synthesis and sialidase activity are increased; however, the increase in sialidase activity dominates, such that the overall expression pattern is an increase in Lex/CD15 and a decrease in sLex/CD15s expression.

We have previously shown that G-CSF increases sLex expression of native myeloid cells35 and we report here concomitant increased expression of CD15/Lex. Importantly, G-CSF-induced maturation of native hematopoietic progenitors was also accompanied by increased cell surface sialidase activity. Notably, despite the fact that G-CSF treatment of native progenitor cells increases FucTIV35 and FucTIX, inhibition of sialidase by DANA abrogated ~90% of the Lex/CD15 increase induced by G-CSF treatment. Thus, differentiation-associated Lex/CD15 expression is dominantly regulated by sialidase digestion of sLex/CD15s in both leukemic blasts and native progenitors. Conversely, anti-CD44 treatment did not induce surface sialidase activity or changes in expression either sLex/CD15s or Lex/CD15 levels on the primitive human leukemic cell line KG1a, which does not differentiate following CD44 ligation. Notably, neither an increase in sialidase activity nor in Lex/CD15 levels drive myeloid cell maturation, as exogenous sialidase treatment strongly increased Lex/CD15 expression and decreased in sLex/CD15s expression, yet with no differentiation-specific morphologic changes.

Four distinct sialidases have been described in mammalian cells (Neu-1 to Neu-4)28-30,31-33. Changes in their expression have been detected in cells that were induced to differentiate or were activated28-31,33. The sialidases can be cytosolic or membrane-associated and possess different substrate specificities. Only Neu-1 and Neu-3 can hydrolyze 4MU-NANA28-30,31,33. Both enzymes are inhibited by DANA. Neu-3 is surface-associated and, though best recognized for cleaving sialic acid expressed on glycolipids (gangliosides), it can also serve as a sialidase for glycoproteins32. Neu-1 is predominantly lysosomal and preferentially cleaves glycoproteins, but it can be translocated to the membrane or secreted by the cell27. The absence of changes in expression for Neu-3 by RT-PCR and western blot is consistent with the observed relative absence of desialylation of glycolipids during myeloid differentiation, while the finding of increased Neu-1 expression by RT-PCR and western blot suggests that myeloid differentiation is associated with induction of this enzyme.

We show here that the bulk of sLex/CD15s to Lex/CD15 transformation on myeloid cells occurs predominantly on glycoproteins, despite the fact that glycolipids express relatively more Lex/CD15 than glycoproteins. Among these glycoproteins was PSGL-1, a sialomucin expressed on most leukocytes and well-recognized to play a critical role in cellular trafficking7,36 and in hematopoiesis37. These functions are mediated by PSGL-1 engagement with E, P and L-selectin, via the presentation of sLex/CD15s on the PSGL-1 protein backbone. We found that increased Lex/CD15 expression, coincident with a decrease of sLex/CD15s, occurs also on CD43, another sialomucin that binds E-selectin24.

There is increasing evidence that modulations in sialic acid display impact normal and pathologic hematopoietic cell development. Aberrantly enhanced sialylation, with concomitant Lex/CD15 “masking”, plays an important role in leukemogenesis and cancer cell metastasis38, and it has also been shown that abnormal sialylation of myeloid cells in chronic myelogenous leukemia inhibits binding to hematopoietic growth factors, which contributes to the block in differentiation39. Consistent with these observations, treatment of HL60 cells with sialidase increases their binding to G-CSF39 and their proliferation in response to GM-CSF40. Accordingly, by increasing sialidase activity in AML cells, CD44 ligation may not only promote their binding to growth factors necessary for their terminal differentiation, but may also prevent their seeding distant sites by decreasing expression of sLex/CD15s, the canonical selectin binding determinant. These notions support future studies for use of anti-CD44 mAbs in differentiation therapy of AML. Moreover, our studies indicate a role for sialidase in regulating Lex/CD15 expression on non-malignant hematopoietic cells, raising the possibility that microenvironment-specific expression of sialidase activity could impact cell adhesion events during cell development. Beyond implications for engagement of PSGL-1 in hematopoiesis, sialylation regulates binding of several myeloid antigens, such as the well-recognized myeloid-specific marker CD33, a member of the siglec family41,42. By modulating binding to siglecs and other lectins, the discrete changes in expression of α(2,3)-linked sialyl residues could significantly impact hematopoiesis by directing localization of progenitors to distinct bone marrow microenvironmental “niches”. Similarly, sialidase expression may regulate Lex/CD15 expression on non-hematopoietic cells and among cells of non-human mammals, with implications for the elaboration of the well-recognized “SSEA-1 antigen” (Lex/CD151), an important marker of embryonic stem cells and neural progenitors in mice43,44. Our results thus support a general model whereby dynamic induction of sialidase activity offers biological versatility to existing cell surface glycan display. Further studies are warranted to elucidate how localized variation(s) in sialidase activity may direct critical cell-cell and cytokine-cell interactions within specialized growth microdomains.

Methods

For Antibodies, Reagents and Sources of human cells please refer to Supplementary Methods online.

Induction of differentiation of AML blasts

AML blasts were seeded in triplicate at 3×105/mL and treated with Hermes-1 (20 μg/mL) or with rat IgG2a (20 μg/mL) for up to 3 days, then analyzed for differentiation as described below.

Treatment with G-CSF

Cells (1×106 cells/ml) were cultured for 72 h in the presence of recombinant human G-CSF (10 ng/ml). In all experiments, L-selectin expression of cells was determined by flow cytometry to test the efficacy of G-CSF treatment (confirmed by loss of L-selectin expression, as previously described)35. After 72h of treatment, cells were used for flow cytometry analysis and sialidase activity assay.

Treatment with sialidase, DANA, 4-F-Glc-NAc

Cells were cultured at 5×106/mL in presence or absence of neuraminidse (0.1U/mL, V. cholerae neuraminidase) at 37°C for 1h and up to 3 days (for differentiation studies, where neuraminidase was added every 24h). For neuraminidase inhibition, cells were treated DANA (0.1 mM), added every 24h to cell cultures. For metabolic inhibitor treatment, cells were incubated with 4-F-GlcNAc (100 μM).

Analysis of myeloid differentiation

Myeloid differentiation was evaluated by cell morphology analysis and by measurement of changes in Lex/CD15 expression. To assess morphological changes, cytospins of treated and untreated cells were stained with May-Grunwald Giemsa for analysis by light microscopy. For all experiments, expression of Lex/CD15 and of sLex/CD15s was measured by flow cytometry before cell culture (t=0) and following 3 days of culture; because HL60 cells and all native human myeloid cells express variable levels of Lex/CD15, the degree of cell differentiation was measured by the relative increase in mean channel fluorescence of CD15-positive cells. Dead cells, labeled by propidium iodide staining, were excluded from the analysis.

Cell extract, immunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis

Cells (5 × 105 to 1 × 107) were solubilized at 4°C for 1h in 50 to 200 μL lysis buffer (50 mM Tris [tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane]-HCl [pH 7.5], 1% Triton, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM sodium fluoride, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl, 10 μg/mL pepstatin, 10 μg/mL leupeptin, and 10 μg/mL aprotinin). The protein content was determined using Bradford assay. PSGL-1 and CD43 were immunoprecipitated using protein-G agarose. For Western blotting, all lanes were normalized for total protein (30μg/sample); samples were diluted in reducing sample buffer and separated in 4-20% gradient SDS/PAGE gels. Resolved proteins were transferred to Sequi-blot polyvinylidine difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Bio-Rad). Blots were blocked with FBS for 2h at room temperature and incubated with anti-CD15 or Heca-452 antibodies (1μg/mL) overnight at 4°C. The membranes were washed and incubated for 1h with an Alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-mouse Ig (for CD15) or goat ant-rat IgM (for Heca-452) at 1:2000 dilution and developed by using Western Blue Stabilized Substrate for Alkaline phosphatase (Promega, Madison, WI). For western blot analysis of Neu-1 and Neu-3, blots were probed respectively with polyclonal anti-Neu-1 Ab (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Ca) and anti-Neu-3 mAb (MBL, Japan).

Measurement of sialidase activity

Sialidase activity was assessed using 4-MU-NANA as substrate. Cells (2×106) resuspended in 200μL of a solution containing 0.05M sodium acetate pH 4.4 and 0.125mM 4-MU-NANA at pH 4.5 and incubated at 37°C for 2 h. The reaction was terminated by adding 1ml of a solution containing 0.133M glycine, 0.06M NaCl and 0.083M Na2Co3 pH 10.7, just prior to the fluorometric determination of released 4-methylumbelliferone (4-MU) at Ex 365 nm and Em 450 nm using a Photon Technologies International Fluorometer (Lawrenceville, NJ). The concentration of 4-MU generated was measured by subtracting the fluorescence reading of the blank from the fluorescence reading of the samples, and comparing the result to a standard curve generated from solutions of 4-MU (Sigma Aldrich). One unit of sialidase is the amount required to release one nmole of 4-MU per 106 cells.

Protease digestion

Cells (5 × 106/mL) were treated for 1h at 37°C with 0.1% bromelain in RPMI 1640 medium or with proteinase K (200μg/mL) in HBSS containing 150 mM NaCl, then washed in 1X PBS, and Lex and sLex expression levels were analyzed by flow cytometry. The efficacy of protein digestion by bromelain was verified by observed decreased expression of CD44.

RT-PCR

Equal amounts of RNA were used as templates for RT-PCR with Titan™ One Tube RT-PCR System (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) and the primers described in supplementary Table 1. Optimal PCR conditions were 94°C for 2 min, 60°C for 45 sec., and 72°C for 1 min on a PTC-200 Peltier Thermal cycler (MJ Research). Amplified bands were visualized after 1% agarose gel electrophoresis of the PCR products.

Statistical Analysis

Results are presented as mean ± SEM for the indicated number of experiments. Statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA and Student’s t test. A value of P ≤ 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Brackets on Fig. legends are shown only for relevant data displaying statistically significant differences.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to D. Floyd, Dr. S. Hamdan, Dr. C. Silvescu and C. Knoblauch for technical support; to Dr. J. Merzaban, Dr. N. Stamatos, Dr. C. Dimitroff and Dr. M. Burdick for helpful discussions of the manuscript, and to Ms I. Galinsky and Drs R. Stone, D. DeAngelo, M. Wadleigh and A. Sirulnik for assistance in procuring leukemia samples. This work was supported by NHBLI grant RO1 HL60528 (RS), NIDDK grant R21 DK075012 (RS), and the Team Jobie Leukemia Research fund (RS).

Abbreviations

- 4MU-NANA

2′-(4-Methylumbelliferyl-N-acetyl-α-D-neuraminic Acid

- 4MU

4-methylumbellyferone

- Lex

Lewis x

- sLex

sialyl Lewis x

- Gal

galactose

- GlcNAc

N-acetyl glucosamine

- NeuNAc

N-acetyl-neuraminic acid or sialic acid

- Fuc

fucose

- CLA

cutaneous lymphocyte antigen

- MFI

Mean Fluorescence Intensity

- 4-F-GlcNAc

2-acetamido-1,3,6-tri-O-acetyl-4-fluoro-D-glucopyranose

- DANA

2,3-dehydro-2-deoxy-N-Acetyl-neuraminic acid

- PSGL-1

P-selectin Glycoprotein Ligand 1

- GAPDH

Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

Footnotes

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Gooi HC, et al. Marker of peripheral blood granulocytes and monocytes of man recognized by two monoclonal antibodies VEP8 and VEP9 involves the trisaccharide 3-fucosyl-N-acetyllactosamine. Eur J Immunol. 1983;13:306–12. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830130407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tao W, et al. Comparative proteomic analysis of human CD34+ stem/progenitor cells and mature CD15+ myeloid cells. Stem Cells. 2004;22:1003–14. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.22-6-1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henderson JK, et al. Preimplantation human embryos and embryonic stem cells show comparable expression of stage-specific embryonic antigens. Stem Cells. 2002;20:329–37. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.20-4-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anjos-Afonso F, Bonnet D. Nonhematopoietic/endothelial SSEA-1+ cells define the most primitive progenitors in the adult murine bone marrow mesenchymal compartment. Blood. 2007;109:1298–306. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-030551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gege C, Geyer A, Schmidt RR. Synthesis and molecular tumbling properties of sialyl Lewis X and derived neoglycolipids. Chemistry. 2002;8:2454–63. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20020603)8:11<2454::AID-CHEM2454>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foxall C, et al. The three members of the selectin receptor family recognize a common carbohydrate epitope, the sialyl Lewis(x) oligosaccharide. J Cell Biol. 1992;117:895–902. doi: 10.1083/jcb.117.4.895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dimitroff CJ, Bernacki RJ, Sackstein R. Glycosylation-dependent inhibition of cutaneous lymphocyte-associated antigen expression: implications in modulating lymphocyte migration to skin. Blood. 2003;101:602–10. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fuhlbrigge RC, Kieffer JD, Armerding D, Kupper TS. Cutaneous lymphocyte antigen is a specialized form of PSGL-1 expressed on skin-homing T cells. Nature. 1997;389:978–81. doi: 10.1038/40166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sackstein R. The bone marrow is akin to skin: HCELL and the biology of hematopoietic stem cell homing. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122:1061–9. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.09301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sackstein R, et al. Ex vivo glycan engineering of CD44 programs human multipotent mesenchymal stromal cell trafficking to bone. Nat Med. 2008;14:181–7. doi: 10.1038/nm1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zannettino AC, et al. Primitive human hematopoietic progenitors adhere to P-selectin (CD62P) Blood. 1995;85:3466–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Terstappen LW, Buescher S, Nguyen M, Reading C. Differentiation and maturation of growth factor expanded human hematopoietic progenitors assessed by multidimensional flow cytometry. Leukemia. 1992;6:1001–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Gisbergen KP, Ludwig IS, Geijtenbeek TB, van Kooyk Y. Interactions of DC-SIGN with Mac-1 and CEACAM1 regulate contact between dendritic cells and neutrophils. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:6159–68. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.09.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Gisbergen KP, Sanchez-Hernandez M, Geijtenbeek TB, van Kooyk Y. Neutrophils mediate immune modulation of dendritic cells through glycosylation-dependent interactions between Mac-1 and DC-SIGN. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1281–92. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kannagi R. Transcriptional regulation of expression of carbohydrate ligands for cell adhesion molecules in the selectin family. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2001;491:267–78. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1267-7_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lowe JB. Glycosylation in the control of selectin counter-receptor structure and function. Immunol Rev. 2002;186:19–36. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2002.18603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakayama F, et al. CD15 expression in mature granulocytes is determined by alpha 1,3-fucosyltransferase IX, but in promyelocytes and monocytes by alpha 1,3-fucosyltransferase IV. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:16100–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007272200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lund-Johansen F, Terstappen LW. Differential surface expression of cell adhesion molecules during granulocyte maturation. J Leukoc Biol. 1993;54:47–55. doi: 10.1002/jlb.54.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kansas GS, Muirhead MJ, Dailey MO. Expression of the CD11/CD18, leukocyte adhesion molecule 1, and CD44 adhesion molecules during normal myeloid and erythroid differentiation in humans. Blood. 1990;76:2483–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Charrad RS, et al. Effects of anti-CD44 monoclonal antibodies on differentiation and apoptosis of human myeloid leukemia cell lines. Blood. 2002;99:290–9. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.1.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gadhoum Z, et al. The effect of anti-CD44 monoclonal antibodies on differentiation and proliferation of human acute myeloid leukemia cells. Leuk Lymphoma. 2004;45:1501–10. doi: 10.1080/1042819042000206687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li F, et al. Post-translational modifications of recombinant P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 required for binding to P- and E-selectin. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:3255–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maemura K, Fukuda M. Poly-N-acetyllactosaminyl O-glycans attached to leukosialin. The presence of sialyl Le(x) structures in O-glycans. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:24379–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fuhlbrigge RC, King SL, Sackstein R, Kupper TS. CD43 is a ligand for E-selectin on CLA+ human T cells. Blood. 2006;107:1421–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fukushima K, et al. Characterization of sialosylated Lewisx as a new tumor-associated antigen. Cancer Res. 1984;44:5279–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Datta AK, Paulson JC. Sialylmotifs of sialyltransferases. Indian J Biochem Biophys. 1997;34:157–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woods JM, et al. 4-Guanidino-2,4-dideoxy-2,3-dehydro-N-acetylneuraminic acid is a highly effective inhibitor both of the sialidase (neuraminidase) and of growth of a wide range of influenza A and B viruses in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:1473–9. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.7.1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stamatos NM, et al. Differential expression of endogenous sialidases of human monocytes during cellular differentiation into macrophages. Febs J. 2005;272:2545–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang P, et al. Induction of lysosomal and plasma membrane-bound sialidases in human T-cells via T-cell receptor. Biochem J. 2004;380:425–33. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Azuma Y, Taniguchi A, Matsumoto K. Decrease in cell surface sialic acid in etoposide-treated Jurkat cells and the role of cell surface sialidase. Glycoconj J. 2000;17:301–6. doi: 10.1023/a:1007165403771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kopitz J, Muhl C, Ehemann V, Lehmann C, Cantz M. Effects of cell surface ganglioside sialidase inhibition on growth control and differentiation of human neuroblastoma cells. Eur J Cell Biol. 1997;73:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Monti E, et al. Identification and expression of NEU3, a novel human sialidase associated to the plasma membrane. Biochem J. 2000;349:343–51. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3490343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pshezhetsky AV, Ashmarina M. Lysosomal multienzyme complex: biochemistry, genetics, and molecular pathophysiology. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 2001;69:81–114. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(01)69045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stroud MR, et al. Myeloglycan, a series of E-selectin-binding polylactosaminolipids found in normal human leukocytes and myelocytic leukemia HL60 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;209:777–87. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dagia NM, et al. G-CSF induces E-selectin ligand expression on human myeloid cells. Nat Med. 2006;12:1185–90. doi: 10.1038/nm1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hirata T, et al. P-Selectin glycoprotein ligand 1 (PSGL-1) is a physiological ligand for E-selectin in mediating T helper 1 lymphocyte migration. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1669–76. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.11.1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levesque JP, et al. PSGL-1-mediated adhesion of human hematopoietic progenitors to P-selectin results in suppression of hematopoiesis. Immunity. 1999;11:369–78. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Varki NM, Varki A. Diversity in cell surface sialic acid presentations: implications for biology and disease. Lab Invest. 2007;87:851–7. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cyopick P, et al. Role of aberrant sialylation of chronic myeloid leukemia granulocytes on binding and signal transduction by chemotactic peptides and colony stimulating factors. Leuk Lymphoma. 1993;11:79–90. doi: 10.3109/10428199309054733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aldape MJ, Bryant AE, Ma Y, Stevens DL. The leukemoid reaction in Clostridium sordellii infection: neuraminidase induction of promyelocytic cell proliferation. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:1838–45. doi: 10.1086/518004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Crocker PR. Siglecs: sialic-acid-binding immunoglobulin-like lectins in cell-cell interactions and signalling. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2002;12:609–15. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00375-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nguyen DH, Ball ED, Varki A. Myeloid precursors and acute myeloid leukemia cells express multiple CD33-related Siglecs. Exp Hematol. 2006;34:728–35. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Capela A, Temple S. LeX is expressed by principle progenitor cells in the embryonic nervous system, is secreted into their environment and binds Wnt-1. Dev Biol. 2006;291:300–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Da Silva JS, Hasegawa T, Miyagi T, Dotti CG, Abad-Rodriguez J. Asymmetric membrane ganglioside sialidase activity specifies axonal fate. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:606–15. doi: 10.1038/nn1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.