Abstract

The present study examined the emergence of flattery behavior in young children and factors that might affect whether and how it is displayed. Preschool children between the ages of 3 and 6 years were asked to rate drawings produced by either a present or absent adult stranger (Experiments 1 and 2), child stranger (Experiments 2 and 3), classmate, or the children’s own teacher (Experiment 3). Young preschoolers gave consistent ratings to the same drawing by the person regardless of whether the person was absent or present. In contrast, many older preschoolers gave more flattering ratings to the drawing when the person was present than in the person’s absence. Also, older preschoolers displayed flattery regardless of whether the recipient was an adult or a child. However, they displayed flattery to a greater extent towards familiar individuals than unfamiliar ones, demonstrating an emerging sensitivity to social contexts in which flattery is used. These findings suggest that preschoolers have already learned not to articulate bluntly their true feelings and thoughts about others. Rather, they are able to manipulate their communications according to social context.

Introduction

For social animals, it is of paramount adaptive importance to establish, maintain, and enhance social relationships with conspecifics. One of the strategies commonly used in the animal world is grooming. By providing grooming services to others, an individual not only buttresses the here-and-now relationship with another conspecific, but also invests in future cooperative interactions (de Waal, 1997; Cheney & Seyfarth, 1990). Extensive social psychological research has shown that humans also use ‘grooming-like’ strategies in their interactions with others (Gordon, 1996; Higgins, Judge & Ferris, 2003). Unlike many nonhuman animals who groom each other physically, except for intimate partners and some family members, humans mainly use social means for grooming purposes. Chief among these social grooming methods are opinion conformity (e.g. agreeing with another’s views), rendering favors (e.g. giving gifts), downward self-presentation (e.g. showing modesty), verbal and nonverbal dissemblance (e.g. telling white lies), and flattery (or a more neutral term, ‘other enhancement’, which is operationally defined as presenting overly positive information about an individual in front of the individual).

These strategies are collectively referred to as ingratiation behaviors because the goal of using them is to please, assuage, and enhance the reputation of, their recipient. The use of ingratiation behavior is thought to be effective in creating positive impressions of the ingratiator on the recipient, which is confirmed by the existing laboratory and field studies with adults (see Gordon, 1996, and Higgins et al., 2003, for meta-analyses). Ingratiation behaviors are frequently used by adults in both formal (e.g. workplace) and informal (e.g. home) social settings as a major strategy of impression management. Further, extensive studies have shown that among all the ingratiation strategies, flattery is the most effective in increasing positive attitudes in its recipient towards the ingratiator. This explains why flattery is widely used by adults in various social settings in spite of the fact that flattery is often perceived negatively by by-standers (see Higgins et al., 2003).

Despite the extensive research on adults’ use of ingratiation behaviors in general and flattery in particular, limited research has examined the development of flattery behavior in children. Little is known about the age at which this behavior emerges, how it develops with age, and what social or personal factors might contribute to the use of flattery. Research on the development of flattery behavior has important theoretical implications for several reasons. First, it offers insight on the origins of adults’ impression management strategies. Learning to use appropriate ingratiation strategies is likely to be an important socialization task for children. After infancy, children’s social milieu expands significantly. They are faced with the tasks of not only maintaining positive relations with their family members, but also forming new ones with peers and other adults outside their home. To succeed in this task, children must learn various social skills that will help them first make and then maintain positive impressions on others. Because ingratiation behavior in general and specifically flattery behavior is one of the most common and effective impression management strategies used in the adult world, understanding children’s use of flattery would provide information about the process by which such strategies are acquired through socialization processes in childhood.

Second, flattery is a form of communication that poses a paradox for children. On one hand, flattery violates the basic rules of interpersonal communication. According to Grice (1980), one of the most fundamental conventions governing interpersonal communication is the Maxim of Quality, which requires speakers to be truthful and to inform, not misinform, their communicative partners. Children are socialized to adhere to this rule from preschool years (Siegal, 1997). Flattery behavior clearly violates this rule because flattery by definition requires one to convey inaccurate, albeit positive, information to the recipient. On the other hand, Lakoff (1973) suggests that there exist equally fundamental rules of communication that require speakers to avoid speaking the truth as they see it. For example, in some situations, speakers are required to adhere to the so-called Politeness Rules and to communicate in ways that are amicable to their communicative partners. In this situation, flattery, rather than blunt truth, is often needed. Thus, studying the emergence and development of flattery behavior provides a unique opportunity for understanding children’s ability to reconcile seemingly contradictory rules of social communication, and more generally, their social problem-solving skills.

Third, studying the development of flattery behavior would also provide information about how children learn to understand and use appropriate verbal display rules. The term ‘display rule’ has been used in the literature mainly to refer to rules that govern nonverbal emotional expressions (Saarni, 1979, 1984). Talwar and Lee (2002) suggested that similar rules also exist for the regulation of verbal behaviors. They defined verbal and nonverbal display rules as rules governing communications between individuals for relaying information, expressing emotion, and conveying attitude. Such rules can guide individuals to modify their public expressions of private information, feeling, and attitude, and help them determine what verbal and nonverbal behaviors are appropriate or inappropriate to display in a given social setting. Individuals need to comply with display rules in situations where empathy, courtesy, and customary etiquette are normally expected. In some situations (e.g. when individuals are asked to comment on another’s appearance, competence, or achievement), they might need not only to suppress their genuine verbal and nonverbal reactions, but also use display rules to simulate verbal and nonverbal behaviors appropriate for the situation. In the case of flattery, they must not display their genuine feelings and views about the recipients when interacting with them face to face. Rather, they need to present overly positive verbal displays to the recipients.

A handful of existing studies suggest indirectly that flattery behavior might emerge in preschool years. There have been a growing number of studies on the development of self-presentation, which concerns how children attempt to manipulate another’s positive views of them (see Banerjee & Yuill, 1999a). These studies reveal that by 4 years of age, children begin to show an understanding that self-presentational displays can influence others (Banerjee & Yuill, 1999b), although such understanding is rudimentary and only matures in later childhood (Aloise-Young, 1993; Banerjee, 2002a, 2002b; Banerjee & Yuill, 1999a; Bennett & Yeeles, 1999a, 1999b; Heyman & Legare, 2005; Juvonen & Murdock, 1995). In addition to understanding, preschoolers also are able to actually use self-presentational strategies, although such strategies tend to be self-serving rather than other-enhancing. For example, 2-year-olds share their successes with others more frequently than they share their failures (Stipek, Recchia & McClintic, 1992), and 3-year-olds presented themselves in overly positive lights when describing their conflicts with siblings (Ross, Smith, Spielmacher & Recchia, 2004). As self-serving and flattery presentations are both impression management strategies, and the latter may also in fact be fundamentally self-serving (Vonk, 2002), these findings suggest that flattery behavior may emerge concurrently with self-serving presentational behaviors.

Another related area of research is children’s verbal and nonverbal dissemblance behaviors. Cole (1986) used an ‘undesirable gift’ paradigm in which children received a disappointing gift from an experimenter (also see Saarni, 1984). She found that even 3-year-olds were able to mask their disappointed emotional expressions when the experimenter was present, but did not do so when they were alone. Talwar and Lee (2002) used a ‘Reverse Rouge’ task in which the experimenter had a conspicuous mark of lipstick on the nose. The child was asked to take a picture of the experimenter, but before the picture was taken the experimenter asked, ‘Do I look okay for the picture?’ They found that most children between 3 and 7 years of age stated that the experimenter looked okay, despite the experimenter’s unflattering appearance. However, when the experimenter left, they told another adult that the experimenter actually did not look okay. The researchers concluded that children as young as 3 years of age are able to dissemble verbal messages about another’s unusual appearance.

These findings suggest that preschool children do not always bluntly convey their true feelings. Rather, they are able to modify their verbal and nonverbal behaviors according to the social situation. Given these findings, one may expect preschoolers to be capable of using flattery because such behaviors also require children to regulate their verbal and nonverbal behaviors that are not consistent with their genuine thoughts and feelings.

In the present study, three experiments were conducted. In Experiment 1, preschool children between 3 and 6 years of age were asked to rate human figure drawings on two occasions, once when the author (an adult stranger) of one of the drawings was absent, and another time when the author was present. This method was adapted for children from the general evaluative paradigm that has been widely used in studies of flattery in adults (e.g. Jones, Gergen, Gumpert & Thibaut, 1965; Kim, Diekmann & Tenbrunsel, 2003; Vonk, 2002). The aim of this experiment was to examine whether children would use the flattery strategy and inflate their ratings of a drawing in front of its author. In Experiment 2, we asked children to rate a drawing by either an adult stranger or a child stranger to examine whether children would be more inclined to flatter the adult than the child stranger. In Experiment 3, children were asked to rate the drawings by four confederates, either in their presence or absence: (a) a familiar adult (children’s own teacher), (b) an unfamiliar adult (a teacher from another class), (c) a familiar child (children’s own classmate), and (d) an unfamiliar child from another class. We investigated whether preschool children’s familiarity with the recipient, whether the recipient is an authority figure, or the interaction between the two would affect their flattery behavior.

Experiment 1

Method

Participants

A total of 159 children participated: 40 3-year-olds (M = 3.75 years, SD = .29; 24 boys), 59 4-year-olds (M = 4.75 years, SD = .31; 32 boys), and 60 5-year-olds (M = 5.72 years, SD = .32; 27 boys). The children were all Han Chinese from families of all walks of life in a large Eastern Chinese city.

Materials and procedure

Children were seen individually in their teacher’s office adjacent to their classroom. They were informed by the Experimenter that they were going to rate drawings and some of them were drawn by children and some by teachers. Before the rating began, children were taught how to use a 7-point Likert scale with the use of a chart. On the chart, three stars represent ‘very good’ (7), two stars ‘good’ (6), one star ‘a little good’ (5), a circle ‘not good not bad’ (4), a cross ‘a little bad’ (3), two crosses ‘bad’ (2), and three crosses ‘very bad’ (1).

The appropriateness of the rating scale for preschoolers was validated with a different group of 3-, 4-, and 5-year-olds (N = 10 per group, five males). The children were given nine human figure drawings to rate. The drawings were chosen from a collection of drawings obtained using the standardized procedure of the Draw-A-Person Test (DAPT) such that three were of poor quality (Type 1 drawings), three were of medium quality (Type 2 drawings), and three were of excellent quality (Type 3 drawings). This classification was confirmed by a trained DAPT specialist who scored the drawings according to the test manual: Type 1 drawings received low raw scores (13, 17, 23), Type 2 received medium scores (25, 26, 27), and Type 3 received high scores (35, 39, 40). The expert’s scores were consistent with the ratings given by the three age groups of children with the use of the 7-point Likert scale. For Type 1 drawings, the means (standard deviations) of the ratings by 3-, 4-, and 5-year-olds are 3.23 (.52), 3.37 (.55), and 3.06 (.72), respectively; the age effect was not significant, F(2, 27) = .62, n.s. For Type 2 drawings, the means (standard deviations) of the ratings by 3-, 4-, and 5-year-olds are 4.53 (.67), 4.37 (.64), and 4.33 (.82), respectively; the age effect was not significant, F(2, 27) = .23, n.s. For Type 3 drawings, the means (standard deviations) of the ratings by 3-, 4-, and 5-year-olds are 5.13 (.65), 6.00 (.74), and 5.30 (.60), respectively; the age effect was significant, F(2, 27) = 4.79, p < .05. Post-hoc analyses (Student-Newman-Keuls tests) showed that although all children gave high ratings to Type 3 drawings, 4-year-olds gave significantly higher ratings than did the other two age groups whose ratings did not significantly differ from each other. These results suggest that overall preschoolers are able to use the 7-point Likert scale appropriately for rating human figure drawings. However, 4-year-olds may give higher ratings than 3- and 5-year-olds to drawings of excellent quality.

After children received training about how to use the rating scale, they were given a stack of ten human figure drawings. The scoring criteria of the DAPT were used to choose ten drawings that ranged across poor to average to excellent. The choice of these ten drawings allowed for sufficient variability in children’s ratings. The Experimenter saw children individually and showed them the drawings one by one, and asked them to give each a rating. After children rated all ten drawings, the Experimenter surreptitiously placed the two drawings that were rated in the middle range (between ‘a little bad’ with a score of 3 to ‘a little good’ with a score of 5) in the 6th and 7th positions of the stack. These drawings served either as a Control or an Experimental Drawing. Then, the Experimenter made an excuse and left the room. Once outside the room, she recorded the ratings to the Control and Experimental Drawings that the children gave.

Shortly after, a Confederate (an adult unfamiliar to the children) came to the room claiming to be a teacher from another class. One male adult and one female adult served as the Confederate and saw approximately half the participants. The Confederate asked the child what he or she was doing. After being informed of the rating task, the Confederate asked the child to rate again the Control Drawing (e.g. the one in the 6th position). After that, the Confederate pretended to discover that the drawing in the 7th position (the Experimental Drawing) was her drawing and told children: ‘I drew this picture. Could you please rate my drawing? How many marks will you give to me?’ Half of the children were asked to rate the two drawings in the opposite order. After the children re-rated the two drawings, the Confederate left the room and reported the ratings to the Experimenter. The Experimenter then returned and debriefed the children about the study. They were given a sticker, and thanked for their participation.

The behavior of interest here was whether children would increase their rating to the Experimental Drawing in front of the Confederate and thus show flattery behavior when compared with their previous rating to the same drawing in front of the Experimenter. The order of the two ratings was fixed because it was impossible to ascertain a priori which drawing would receive a middle range rating by a particular child. At the same time, it was crucial to choose a middle range drawing as the Control and Experimental to allow children’s ratings to increase or decrease flexibly. This strategy also avoided the ‘regression to the mean’ phenomenon that might occur if the drawings with more extreme ratings had been chosen. Further, the validation results suggested that children between 3 and 5 years of age would give similar ratings to middle range drawings, which ensured that age differences in results, if any, could not be attributed to differences in children’s rating biases.

Results and discussion

Children’s ratings of the Control or Experimental Drawing were first converted into the following numbers: ‘Very good’ = 3, ‘Good’ = 2, ‘A little good’ = 1, ‘Not good not bad’ = 0, ‘A little bad’ = -1, ‘Bad’ = -2, and ‘Very bad’ = -3. Then, to better measure whether children had displayed flattery behavior, we followed the conventions of the existing adult research on flattery: children’s first rating to the Control or Experimental Drawing was subtracted from their second rating to the same drawing, resulting in a difference score. A positive difference score between children’s second rating of the same drawing in front of the Confederate and their first rating in her absence was used as an index of flattery behavior.

Preliminary analysis revealed no significant effect of participant and confederate gender. The data for both factors were combined for the subsequent analyses. To ensure that the possibility of ‘regression to the mean’ was ruled out, children’s first ratings of the Experimental or Control drawings (i.e. when the Confederate was absent) were compared for all three age groups using a 3 (age) × condition 2 (experimental vs. control drawing) repeated measures ANOVA with the last factor as a repeated measure. No significant effects were obtained. For the Experimental drawing, the 3-, 4-, and 5-year-olds’ mean first ratings were .38, .07, and .10, respectively. For the Control drawing, the 3-, 4-, and 5-year-olds’ mean ratings were .30, .15, and -.92, respectively. Thus, children’s first ratings were close to the middle point of the rating scale (-3 to +3) as planned.

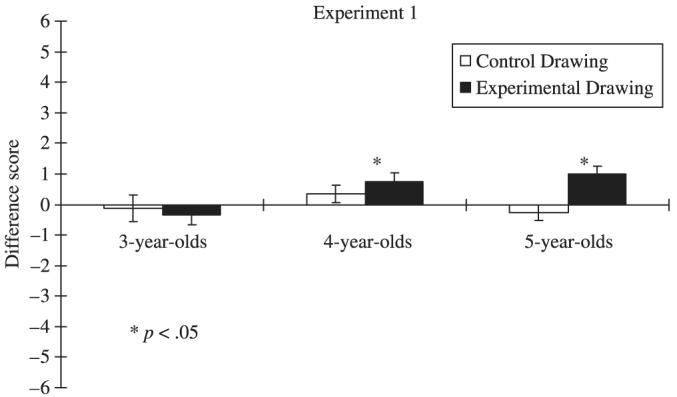

Table 1 shows the means and standard deviations of the difference scores for the Control and Experimental Drawings (see also Figure 1). A 2 (Drawing Type: Control vs. Experimental) × 3 (Age groups) repeated measures ANOVA with the first variable as a repeated measure was performed on the difference scores. The Age effect was not significant, F(2, 156) = 2.64, p > .05. The Drawing Type effect was significant, F(1, 156) = 5.12, p < .05, η2 = 0.032, p = 0.61. The interaction between Age and Drawing Type was also significant, F(2, 156) = 4.00, p < .05, η2 = 0.05, p = 0.71. Post-hoc t-tests (LSD, α = .05) compared the difference scores between Drawing Types and revealed that 5-year-olds’ ratings were significantly greater for the Experimental Drawing than the Control Drawing, t(59) = 3.87, p < .001, whereas the differences between the two types of drawings were not significant for both 3-year-olds and 4-year-olds, t(39) = -.56, p > .05, and t(58) = 1.09, p > .05, respectively.

Table 1.

Means (standard deviations) of difference scores in each experiment

| Experimental drawing | Control drawing | |

|---|---|---|

| Experiment 1 | ||

| 3-year-olds | –0.35 (2.03) | –0.13 (2.78) |

| 4-year-olds | 0.75 (2.14) | 0.34 (2.19) |

| 5-year-olds | 1.00 (1.88) | –0.27 (1.98) |

| Experiment 2 | ||

| Unfamiliar child | 0.93 (1.90) | 0.01 (0.58) |

| Unfamiliar adult | 1.10 (2.28) | 0.17 (1.12) |

| Experiment 3 | ||

| Familiar child | 1.58 (2.67) | |

| Familiar adult | 1.53 (1.86) | |

| Unfamiliar child | 0.67 (2.29) | |

| Unfamiliar adult | 1.03 (2.01) | |

| Control | –0.01 (0.97) |

Figure 1.

Mean difference scores and standard errors between children’s ratings of drawings in the presence and absence of the drawings’ authors in Experiment 1. (* denotes significant difference from zero)

Also, one-sample t-tests compared children’s mean difference scores to zero. Three-year-olds did not significantly change their ratings for the Control and Experimental Drawings between the first and second ratings: t(39) = -.29, p > .05, and t(39) = -1.09, p > .05, respectively. In contrast, while 4- and 5-year-olds’ ratings for the Control Drawing did not differ from zero (t(58) = 1.19, p > .05, and t(59) = -1.04, p > .05, respectively), they increased their ratings significantly to the Experimental Drawing in front of the Confederate when compared with their ratings to the same drawing in the person’s absence, t(58) = 2.68, p < .05, and t(59) = 4.13, p < .001, respectively.

Thus, for 3-year-olds, the results from the ANOVA and one-sample t-tests consistently showed that their ratings of the same drawings did not change regardless of the Confederate being present. For 4-year-olds, the ANOVA results contradicted the results of the one-sample t-tests, which suggests that 4-year-olds might be in a period of transition. For 5-year-olds, both types of analyses consistently revealed that the children inflated their ratings of the Confederate’s drawing when doing the rating task in front of the person. Because the 5-year-olds did not significantly change their ratings for the Control Drawing, the increase in their ratings to the Experimental Drawing in front of the Confederate was also not due to the fact that they had to rate the same drawing twice. Rather, they increased their ratings to the Experimental Drawing specifically for the Confederate. Thus, although the 5-year-olds were highly consistent when rating the Control Drawing, they appeared to lose the consistency when evaluating the drawing by an individual who was in front of them and changed their ratings to the drawing. Given that this change was in the positive direction and consistent with the operational definition of flattery behavior, it is suggestive that the increase in the 5-year-olds’ ratings served as a form of flattery to the recipient.

One could argue that the significant results regarding the 5-year-olds’ ratings of the Experimental Drawing were due to a bias created by a relatively small number of children who made large flattery judgments (i.e. they significantly increased their rating of the Experimental Drawing in front of the Confederate), whereas the rest did not. To address this issue, we counted the number of 5-year-olds who increased their ratings by at least one point and found that 53% of them (32/60) did so. This result suggested that the present finding regarding the 5-year-olds was not unduly influenced by a small number of children in the sample.

However, one potential problem of Experiment 1 was that the confederate was an adult. Children might have felt intimidated and therefore coerced to increase their ratings in front of the confederate. Although adult research has shown that flattery is often shown by an individual at a lower level of social hierarchy to another individual at a higher one and that such upward flattery tends to produce the most positive outcome among all ingratiation behaviors (Gordon, 1996), adults tend to flatter voluntarily and typically do not do so under duress. Thus, it is crucial to ascertain whether young children will continue to display flattery behaviors when the recipient is not an authority figure. Experiment 2 was conducted to address this issue directly.

Experiment 2

In this experiment, two between-subjects conditions were used. The Adult Confederate condition was identical to that in Experiment 1. In the Child Confederate condition, a child who was the same age as the participants and was unfamiliar to them served as a confederate. If children in Experiment 1 inflated their ratings of the confederate’s drawing because they felt intimidated by an adult authority figure, a significant condition effect should result. Children in the Adult Confederate condition should be more likely to inflate their ratings to the confederate’s drawing than those in the Child Confederate condition. Otherwise, no difference in rating increase between the two conditions should be observed.

Method

Participants

A total of 60 6-year-old children participated (M = 6.74 years, SD = .42; 32 boys). The children were all Han Chinese, again from families of all walks of life in a large Eastern Chinese city. The choice of this age group for the present experiment was for two reasons. First, the results of Experiment 1 showed that the display of flattery behavior increased significantly with age, and the increase was mainly at 5 years of age. Thus, to test the hypothesis of the present experiment, it is not necessary to include children in younger age groups because they as a group did not consistently show significant signs of flattery in Experiment 1. Second, in Experiment 1 many but not all 5-year-olds inflated their ratings to the confederate’s drawing. The age pattern obtained in Experiment 1 suggests that with a further increase of age beyond 5 years, more children would display flattery behavior to the confederate, which would make it possible to test factors that may influence children’s decision to display flattery behaviors.

Materials and procedure

Children were randomly assigned to two conditions. The Adult Confederate condition was identical to the procedure used in Experiment 1 in which children were asked to rate a Control Drawing and an Experimental Drawing either in front of the adult or in her absence. In the Child Confederate condition, two 6-year-old child confederates (one male and one female) from another class replaced the adult confederates. Prior to the experiment, the child confederates were taught about how to carry out the experimental procedure and practiced the procedure. Other than the identity of the confederate, the Child Confederate condition was identical to the Adult Confederate condition.

Results

The same scoring procedure as in Experiment 1 was used for the rating response. Preliminary analyses revealed no participant and confederate gender differences in children’s difference scores and thus the data for both factors were combined for subsequent analyses.

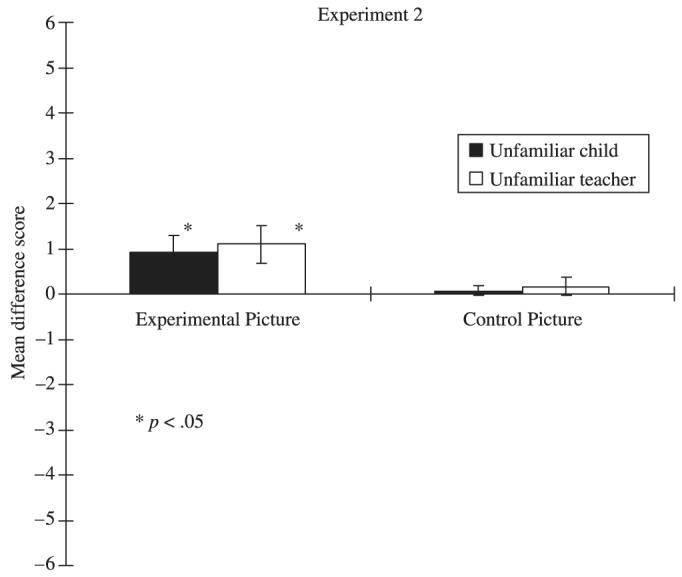

Table 1 shows the means and standard deviations of the difference scores for the Control and Experimental Drawings in the Adult and Child Confederate Conditions (also see Figure 2). A 2 (Drawing Type: Experimental vs. Control) × 2 (Confederate Type: Adult vs. Child) repeated measures ANOVA with the first factor as repeated measures was conducted on the rating difference scores. The Drawing Type effect was significant, F(1, 58) = 11.78, p < .05, η2 = 0.17, p = 0.92: Children increased ratings of the Experimental Drawing but not the Control Drawing in front of the Confederate when compared to their ratings to the same drawings in the Confederate’s absence. Other effects were not significant. When one-sample t-tests compared the difference scores with zero, for the Adult and Child Confederate Condition, the mean difference scores for the Experimental Drawing were significantly above zero, t(29) = 2.64, p < .05, and t(29) = 2.70, p < .05, respectively. In contrast, the mean difference scores for the Control Drawing were not significant, t(29) = .82, p > .05, and t(29) = .63, p > .05.

Figure 2.

Mean difference scores and standard errors between children’s ratings of drawings in the presence and absence of the drawings’ authors in Experiment 2. (* denotes significant difference from zero)

Also, 60% (18/30) of the children made at least one point increase in their ratings for the Experimental Drawing by the adult stranger, whereas 37% (11/30) of them did the same for the Experimental Drawing by the child confederate. A chi-square analysis revealed that the difference in proportion between the two conditions was marginally significant, χ2 (N = 60, df = 1) = 3.27, p = .07. For the Control Drawings, most children did not change their ratings; 73% (22/30) in the Adult Confederate Condition, and 87% (26/30) in the Child Confederate Condition.

The present experiment replicated the findings of Experiment 1. Children inflated their ratings to an adult stranger’s drawing in front of the adult. When the stranger was a child, the child participants also inflated their ratings, suggesting that children’s inflated ratings to the adult confederate’s drawings in Experiments 1 and 2 were not the result of a perceived threat or intimidation by the adult. Whether the stranger was an adult or a child apparently did not affect the extent of children’s flattery behavior because children inflated their ratings to the adult and child confederates’ drawings similarly.

However, the marginally significant difference between the Adult and Child conditions in terms of the proportion of children who increased their ratings by at least one point is worth noting. It is possible that this marginal effect is simply a statistical error. It is also possible that 6-year-olds might flatter a child and an adult differently, but this difference is too small to be detected with the use of the less powerful between-subjects design of the present experiment. Another possibility is that the child participants might have treated the adult and child confederates differently in terms of whether they should receive flattery. However, once the children decided to flatter, they might display the same extent of flattery to the child and adult confederates. This is because flattery is a newly acquired social skill to 6-year-olds who may not have acquired the necessary experience and skill to differentiate the extent to which a child or an adult is flattered.

Yet another possible explanation of these results of Experiment 2 is the fact that the child and adult confederates were total strangers to the participants. Because of the lack of familiarity with either confederate, the children might not have realized the difference between the child and adult strangers or see the need to adjust their flattery behavior accordingly. Had they been someone they were familiar with (e.g. one’s own teacher vs. a classmate), they might have shown greater flattery to the teacher than the classmate because to ensure being liked by one’s own teacher is presumably more valuable than by one’s classmate. This possibility is consistent with several existing studies in the adult self-presentation literature that specifically manipulated familiarity or social status or both. For example, Tice, Butler, Murayen and Stillwell (1995) found that adults responded differently when presenting information about themselves to a friend versus a stranger. Their self-presentation was more modest when the recipient was a friend than when the recipient was a stranger. More relevant to the present study, Bohra and Pandey (1984) found that adults displayed more flattery behaviors to their boss than peers (a friend or a stranger) and more flattery behaviors to a friend than a stranger.

Experiment 3 was conducted to test these possibilities. We not only manipulated children’s familiarity with the confederates in addition to whether the recipient was an adult or a child, but also used the more powerful withinsubjects design.

Experiment 3

In the present experiment, children were asked to give ratings to either their own teacher or classmate, or a teacher or same-aged peer whom they had never met before. Children were expected to be more inclined to display flattery behaviors to familiar recipients than unfamiliar ones. This is because it is highly likely that they have had and will continue to have social interactions with their own teachers and classmates, and flattery is effective for maintaining and enhancing such existing relationships. In contrast, because it is uncertain whether the children will encounter the unfamiliar teacher or peer again in the future, they are expected to flatter the unfamiliar individuals to a lesser extent than they do to the familiar individuals.

Method

Participants

Sixty-six 6-year-olds who did not participate in Experiment 2 were recruited and randomly assigned to two conditions. Thirty-three children participated in the Experimental condition (M = 6.42 years, SD = .27; 18 boys). Thirty-three participated in the Control condition (M = 6.28 years, SD = .30; 17 boys). The children were all Han Chinese, again from families of all walks of life in a large Eastern Chinese city.

Materials and procedure

The procedure for the experimental condition was the same as that used in Experiment 1 except for the following modifications. First, the Experimenter saw children individually and asked them to rate a pile of 14 drawings one by one, after which she surreptitiously put four drawings with medium level ratings on the top of the pile. Then, she made an excuse and left the room and wrote down the child’s ratings to the four drawings. At this point, one of four types of confederates (who were trained before the experiment) entered the room. They were: familiar adult, familiar child, unfamiliar adult, and unfamiliar child. For each confederate type, there was one male and one female confederate, who were randomly assigned to interact with approximately half of the child participants. Upon seeing the drawings, the confederate claimed the first drawing to be his or hers and asked the participant to rate the drawing. Once the rating was done, the drawing was removed from the pile, and the confederate left the room and reported the participant’s rating to the Experimenter. After a short delay, the second confederate entered the room and repeated the first confederate’s procedure with the second drawing. This procedure was repeated until the four confederates’ drawings were rated. To avoid the order of the confederates affecting the results, the order by which the four confederates entered the room was counter-balanced between subjects. Eight participants saw the familiar adult (1) first, followed by the familiar child (2), then the unfamiliar teacher (3), and finally the unfamiliar child (4). Another eight saw the confederates in the order of 2-3-4-1; yet another eight participants saw the confederates in the order of 3-4-1-2. The rest saw the confederates in the order of 4-1-2-3.

Unlike the previous experiments, because participants had to re-rate four drawings, to avoid fatigue they were not asked to rate another four control drawings. Instead, a between-subjects Control condition was used. In the Control condition, after the participant rated a pile of 14 drawings in front of the Experimenter, the Experimenter put four drawings with medium level ratings on the top of the pile and left the room. A confederate then entered and asked the children to re-rate the drawings without indicating the authorship of the drawings.

Results

The same scoring procedure as in Experiment 1 was used for the rating response. Preliminary analyses revealed no effects of confederate and child gender or order on children’s difference scores and thus the data for these factors were combined for subsequent analyses.

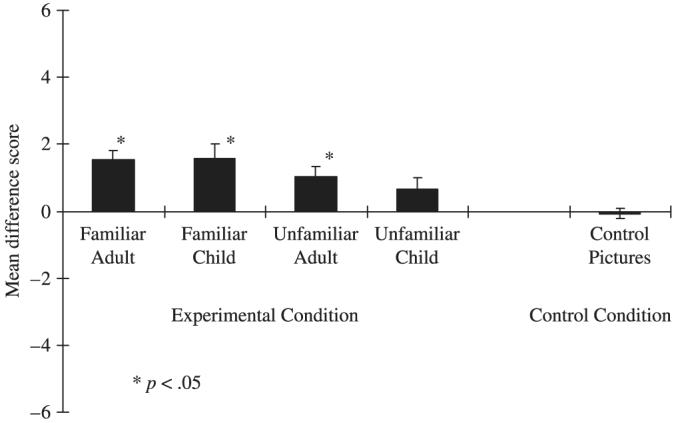

Table 1 shows the means and standard deviations of the difference scores for the Control and Experimental Drawings in the five conditions (also see Figure 3). A 2 (Familiarity: Familiar vs. Unfamiliar) × 2 (Confederate Type: Adult vs. Child) repeated measures ANOVA with the two factors as repeated measures was conducted on the rating difference scores in the Experimental condition. The Familiarity effect was significant, F(1, 32) = 5.21, p < .05, η2 = 0.14, p = 0.60: whereas 6-year-olds showed flattery to both familiar and unfamiliar individuals, they displayed the behavior to a significantly greater extent to familiar individuals than unfamiliar ones. All other effects were not significant. The lack of the Confederate Type effect replicated the results of Experiment 2.

Figure 3.

Mean difference scores and standard errors between children’s ratings of drawings in the presence and absence of the drawings’ authors in Experiment 3. (* denotes significant difference from zero)

We counted the number of children who made at least one point increase in their ratings: For the control drawing, 73% (24/33) of the children did not change their ratings. For the familiar confederates, 70% (23/33) made at least one point increase in their ratings for the drawing by the familiar adult, and 67% (22/33) did so for the drawing by the familiar child (a sign test showed no significant difference between the two conditions). For the unfamiliar confederates, 52% (17/33) of the children made at least one point increase in their ratings for the drawing by the unfamiliar adult, and 48% (16/33) did so for the drawing by the unfamiliar child. A sign test showed no significant difference between the two conditions. This result failed to replicate the marginally significant finding of Experiment 2 and suggests that that finding might be a statistical error.

When one-sample t-tests compared the difference scores with zero, the mean difference score for the control drawings was not significantly different from zero, t(32) = -.17, p > .05, nor was the mean difference score for the unfamiliar child’s drawing, t(32) = 1.32, p > .05. However, the mean difference score for the drawings by the familiar teacher, unfamiliar teacher, and familiar child was significantly above zero, t(32) = 4.54, p < .01, t(32) = 3.93, p < .01, and t(32) = 2.78, p < .01, respectively. These results again suggest that 6-year-olds’ flattery behaviors were influenced by their familiarity with the recipients. They inflated their ratings significantly to drawings by familiar individuals, regardless of whether they were a teacher or a child. However, when the individuals were unfamiliar, they increased their ratings to the adult stranger significantly but failed to do so to the drawings by child strangers. It should be noted that this last finding should be interpreted with caution because the above ANOVA failed to reveal a significant interaction between recipient type and familiarity.

General discussion

The present study examined the emergence of flattery behavior and factors that might affect children’s display of this behavior. Several important findings were obtained. First, there is a significant age difference in children’s display of flattery behavior. Three-year-olds gave consistent ratings to the same drawing by an adult both in front of the adults and in their absence. Five- and 6-year-olds inflated their ratings to the same drawing when the adult author of the drawing was present compared with when the author was absent. The results for 4-year-olds were mixed. They behaved in some ways similar to the older children and in other ways similar to 3-year-olds, suggesting that the 4-year-olds might be in a period of transition. Thus, it appears that the use of flattery emerges during the preschool years. Second, once children begin to display flattery behaviors, they do not limit their flattery to just adults. They flatter other children as well. Third, children’s familiarity with the recipient of their flattery affects the extent to which they display flattery behaviors. They display greater flattery towards familiar individuals than unfamiliar ones, suggesting preschoolers’ emerging sensitivity to social contexts in which flattery behavior is best deployed. However, they are yet to learn to flatter teachers and school mates differentially.

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to investigate the development of flattery behavior in young children. The present findings are in general consistent with existing results concerning children’s use of verbal and nonverbal display rules for prosocial purposes. Evidence to date has shown that during the preschool years, children already are capable of adjusting their emotional expressions according to social contexts. For example, they are capable of faking a positive expression in front of a gift-giver when receiving an undesirable gift from the person. However, when the gift-giver is not present, they show a genuine negative expression of disappointment (Cole, 1986). Young children are also able to tell white lies in front of another person when the person has an unusual physical appearance (Talwar & Lee, 2002). When the person is not present, young children make truthful statements about their negative views about the person’s appearance. In line with these findings, the 5- and 6-year-olds in the present study also appeared to regulate their verbal displays according to social contexts. They gave one rating to a drawing when the author of the drawing was absent and inflated the rating when the author was present. Taken together, these findings suggest that preschoolers do not always bluntly display their genuine emotions and thoughts. Rather, they are able to use such communicative rules as the Maxim of Quality and Politeness Rules adaptively and manipulate their verbal and nonverbal displays according to social contexts. This should be seen as a remarkable feat given that preschoolers have only recently achieved the basic mastery of their native language.

The present findings are also in line with existing evidence regarding the emergence of impression management behaviors in preschool children. Existing studies have shown that young children not only show an emergent understanding of the impact of self-presentation on social interactions (Banerjee & Yuill, 1999b), but also actually use such strategies for self-enhancing purposes (Ross et al., 2004; Stipek et al., 1992). As mentioned earlier, the existing studies with preschool children have mainly focused on their understanding and use of impression management strategies to present themselves in an overly positively light. The present study shows that they are also capable of using strategies to present others over-positively. Given that flattery and self-presentation strategies serve to create positive impressions of oneself on others and are widely used in the adult world, the existing findings taken together suggest that impression management strategies have an early developmental origin.

Many additional questions remain unanswered. One of the major questions is: When children presented overly positive evaluations to the recipient, did they do so with clear awareness that they were not telling the full truth? If the answer is yes, it would suggest that children are not only capable of displaying flattery but are also doing so deliberately with an intent to deceive. The present study could not answer this question because we did not inquire why they inflated their ratings of a drawing in front of its author, nor did we assess whether children were aware of their rating inflations. Future studies could, for example, have the experimenter point out to children the discrepancies in their ratings of the same drawing and ask them to explain the discrepancies. Children can also be assessed in terms of their theory-of-mind understanding. Such additional information should be helpful in understanding the intentional nature or otherwise of children’s flattery behavior.

Another major question concerns the significant age effect. Although the present study showed significant differences between the 5- and 6-year-olds and the younger children, it remains unknown as to why such significant age difference exists. There exist several, not necessarily mutually exclusive, possibilities. One possibility is social learning experience: To learn to flatter, children may need a certain level of exposure to others (e.g. adults and older children) successfully performing flattery behaviors. This social learning hypothesis would suggest that children in certain social environments (e.g. children attending full-time preschool centers) may learn flattery at an earlier age than others (e.g. home cared children). Similarly, children from one culture may also be more inclined to flatter than those from another culture. The present study was conducted in China, a collectivistic society where children have been socialized to protect and enhance the public ‘face’ of another person so as to promote group harmony (Lee, Cameron, Xu, Fu & Board, 1997; Lee, Xu, Fu, Cameron & Chen, 2001; Lee, 2000). One of the common ‘face’ protecting and enhancing methods is ingratiation. Thus, it is possible that Chinese children may have considerably more exposure to flattery behaviors used by others than Western children. Based on the social learning hypothesis, Chinese children then should have an earlier onset of flattery behavior than Western children, a hypothesis that needs direct testing in the future.

Another possible explanation for the significant age effect is that the 5- and 6-year-olds in the present study were more advanced than the younger ones in their social understanding that is necessary for the successful and appropriate deployment of flattery behaviors. One such understanding is that one’s overt expressions of emotions and attitude can be different from what is experienced internally. Although understanding of the appearance—reality distinction in the physical domain begins at 3 years of age (e.g. Sapp, Lee & Muir, 2000), it is well established that this understanding in the social and communicative domains begins to emerge at around 5 and 6 years of age (e.g. Gross & Harris, 1988; Harris, Donnelly, Guz & Pitt-Watson, 1986). Another related understanding is that people do not always strictly adhere to such conversational rules as the Maxim of Quality. Evidence to date suggests that this understanding only begins to emerge during the late preschool years (e.g. Ackerman, 1981; Conti & Camras, 1984). Thus, the emergent nature of such social understandings might have played a crucial role in the current significant age effect.

Social understanding also may play an important role in the further development of flattery behavior beyond 6 years of age. For example, although the present study showed that the older preschoolers were able to adjust their flattery behaviors according to the familiarity of their recipient, it failed to obtain strong evidence as to whether young children would adjust their flattery behavior according to whether the recipient was a teacher or a peer. This null result is in strong contrast to adults’ ability to adjust their flattery behaviors horizontally (e.g. to peers) or vertically (e.g. to superiors; see Gordon, 1996, and Higgins et al., 2003). However, the present finding is in general consistent with the existing studies concerning the development of the understanding of self-presentation and ingratiation that typically focus on children at 6 years of age and above (e.g. Aloise-Young, 1993; Banerjee, 2002a, 2002b; Banerjee & Yuill, 1999a, 1999b; Bennett & Yeeles, 1990a, 1990b; Heyman & Legare, 2005; Juvonen & Murdock, 1995). These studies showed that although 6-year-olds already show some appreciation of another’s attempt at self-presentation or ingratiation, they have difficulty understanding that such attempts need to be modified according to whether the audience is a peer or an adult (e.g. Banerjee, 2002a), and such attempts are motivated by interpersonal reasons (e.g. Bennett & Yeeles, 1990a, 1990b). Understanding interpersonal motivations underlying flattery behaviors may be crucial for children to flatter a teacher or a peer differently (e.g. enhancing friendship when flattering a peer vs. receiving favorable treatments when flattering an adult). It is perhaps due to the lack of this understanding that older preschoolers in the present study failed to differentiate in their flattery behavior between the peer and the adult.

In addition to issues discussed above that are directly related to the present study, research on several other major issues is needed for us to form a comprehensive picture of the development of flattery. For example, it is well established that flattery is a common behavior among adults (Gordon, 1996; Higgins et al., 2003). It is entirely unknown the extent to which children naturally display this behavior in their everyday environment, and whether such naturally occurring behaviors are consistent with the behaviors our children displayed in the present study. It is also well known that flattery tends to lead the recipient of flattery to display positive reactions to, but the by-standers to form negative attitudes about, the flatterer (Gordon, 1996; Higgins et al., 2003). It is unclear whether this phenomenon also exists among children. Also, as suggested by the above discussion, social understanding may play an important role in the development of flattery behavior. However, it is unclear how children’s understanding and evaluation of flattery develops with age, how their understanding and evaluation of flattery influences their actual use of flattery, and vice versa. Empirical research that addresses these questions should eventually add a developmental dimension to the extensive literature on flattery, and provide crucial information about the developmental history of this pervasive, useful and yet ill-reputed human behavior.

References

- Ackerman BP. When is a question not answered? The understanding of young children of utterances violating or conforming to the rules of conversational sequencing. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 1981;31:487–507. [Google Scholar]

- Aloise-Young PA. The development of self-presentation: self-promotion in 6- to 10-year-old children. Social Cognition. 1993;11(2):201–222. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee R. Audience effects on self-presentation in childhood. Social Development. 2002a;11(4):487–507. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee R. Children’s understanding of self-presentational behavior: links with mental-state reasoning and the attribution of embarrassment. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2002b;48(4):378–404. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee R, Yuill N. Children’s understanding of self-presentational display rules: associations with mental-state understanding. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 1999a;17(Pt 1):111–124. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee R, Yuill N. Children’s explanations for self-presentational behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology. 1999b;29(1):105–111. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett M, Yeeles C. Children’s understanding of the self-presentational strategies of ingratiation and self-promotion. European Journal of Social Psychology. 1990a;20(5):455–461. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett M, Yeeles C. Children’s understanding of showing off. Journal of Social Psychology. 1990b;130(5):591–596. [Google Scholar]

- Bohra KA, Pandey J. Ingratiation toward strangers, friends, and bosses. Journal of Social Psychology. 1984;122:217–222. [Google Scholar]

- Cheney DL, Seyfarth RM. How monkeys see the world: Inside the mind of another species. University of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM. Children’s spontaneous control of facial expression. Child Development. 1986;57(6):1309–1321. [Google Scholar]

- Conti DJ, Camras LA. Children’s understanding of conversational principles. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 1984;38:456–463. [Google Scholar]

- de Waal FBM. The chimpanzee’s service economy: food for grooming. Evolution and Human Behavior. 1997;18:375–386. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon RA. Impact of ingratiation on judgments and evaluations: a meta-analytic investigation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;71(1):54–70. [Google Scholar]

- Grice HP. Studies in the way of words. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Gross D, Harris PL. False beliefs about emotion: children’s understanding of misleading emotional displays. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1988;11:475–488. [Google Scholar]

- Harris PL, Donnelly K, Guz GR, Pitt-Watsdon R. Children’s understanding of the distinction between real and apparent emotion. Child Development. 1986;57:895–909. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1986.tb00253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman GD, Legare CH. Children’s evaluation of sources of information about traits. Developmental Psychology. 2005;41:636–647. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.4.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins CA, Judge TA, Ferris GR. Influence tactics and work outcomes: a meta-analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2003;24:89–106. [Google Scholar]

- Jones EE, Gergen KJ, Gumpert P, Thibaut J. Some conditions affecting the use of ingratiation to influence performance evaluation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1965;1(6):613–625. doi: 10.1037/h0022076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juvonen J, Murdock TB. Grade-level differences in the social value of effort: implications for self-presentation tactics of early adolescents. Child Development. 1995;66:1694–1705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim PH, Diekmann KA, Tenbrunsel AE. Flattery may get you somewhere: the strategic implications of providing positive vs. negative feedback about ability vs. ethicality in negotiation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 2003;90(2):225–243. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff R. Language and woman’s place. Language in Society. 1973;1(2):45–80. [Google Scholar]

- Lee K. The development of lying: how children do deceptive things with words. In: Astington JW, editor. Minds in the making. Blackwell; Oxford: 2000. pp. 177–196. [Google Scholar]

- Lee K, Cameron CA, Xu F, Fu G, Board J. Chinese and Canadian children’s evaluations of lying and truth-telling. Child Development. 1997;64:924–934. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb01971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K, Xu F, Fu G, Cameron CA, Chen S. Taiwan and Mainland Chinese and Canadian children’s categorization and evaluation of lie- and truth-telling: a modesty effect. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2001;19:525–542. [Google Scholar]

- Ross H, Smith J, Spielmacher C, Recchia H. Shading the truth: self-serving biases in children’s reports of sibling conflicts. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2004;50:61–85. [Google Scholar]

- Saarni C. Children’s understanding of display rules for expressive behavior. Developmental Psychology. 1979;15(4):424–429. [Google Scholar]

- Saarni C. An observational study of children’s attempts to monitor their expressive behavior. Child Development. 1984;55(4):1504–1513. [Google Scholar]

- Sapp F, Lee K, Muir D. Three-year-olds’ difficulty with the appearance—reality distinction: is it real or apparent? Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:547–560. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.36.5.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegal M. Knowing children: Experiments in conversation and cognition. 2nd Psychology Press; London: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Stipek D, Recchia S, McClintic S.Self-evaluation in young children Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development 1992571, Serial No. 226). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talwar V, Lee K. Emergence of white lie telling in children between 3 and 7 years of age. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2002;48:160–181. [Google Scholar]

- Tice DM, Butler JL, Murayen MB, Stillwell AM. When modesty prevails: differential favorability of self-presentation to friends and strangers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:1120–1138. [Google Scholar]

- Vonk R. Self-serving interpretations of flattery: why ingratiation works. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;82:515–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]