Abstract

(a) Background

The development of youth psychopathology may be associated with direct and continuous contact with a different culture (acculturation) and to distress related to this process (cultural stress). We examine cultural experiences of Puerto Rican families in relation to youth psychiatric symptoms in two different contexts: one in which migrant Puerto Ricans reside on the mainland as an ethnic minority and another in which they reside in their place of origin.

(b) Methods

Sample

Probability samples of 10 to 13 year old youth of Puerto Rican background living in the South Bronx, New York City (SB) and in the San Juan Metropolitan area in Puerto Rico (PR) (N=1,271) were followed over time.

Measures

Three assessments of internalizing psychiatric symptoms (elicited through the DISC-IV) and of antisocial behaviors (ASB) quantified through a six-point index were carried out. Independent variables included scales of adult and child acculturation and cultural stress, and other putative correlates.

Data Analysis

Within each study site, multilevel linear regression models were examined.

(c) Results

Parental acculturation was associated with ASB in youth at both sites, but youth acculturation itself was not related to psychiatric symptoms. At both contexts, cultural stress was a more consistent correlate of youth psychiatric symptoms than acculturation after controlling for nativity, maternal education, child gender, stressful life events and parental psychopathology. However, the strength of the youth cultural stress association decreased over time.

(d) Conclusion

The association between cultural factors and child psychiatric symptoms is not restricted to contexts where an ethnic group is a minority.

Keywords: antisocial behaviors, internalizing symptoms, child, youth, acculturation, cultural stress, Latino, Puerto Ricans

Introduction

The effect that cultural change has on psychopathology is highly relevant in a world where individuals move from one cultural context to another with increasing frequency. Much of what is known about the relationship between culture and psychopathology is based on studies that compare levels of symptoms across different ethnic groups, both for adults (King et al., 2005; Grant et al., 2004; Patel, Delbello, & Strakowski, 2006; Breslau et al., 2007) and youth (Shrout et al., 1992; Canino & Roberts, 2001; Tolmac & Hodes, 2004; Goodman & Richards, 1995; Beiser, Hou, Hyman, & Tousignant, 2002) living in the same context. In such studies, it is tempting to make attributions about the influence of the context on the cultural experiences of the groups being compared. Such inferences, however, can only be made if the same cultural group is studied in contrasting contexts.

Integrating to a different culture (acculturation) and the possible distress generated by this process (cultural stress) are distinct, though related, aspects of an individual's cultural experience. Acculturation may be defined as the change resulting from direct and continuous contact of individuals to a culture different from their own (Redfield, Linton, & Herskovits, 1936). Acculturation has been associated to depression in children (Canabal & Quiles, 1995; Kaplan & Marks, 1990). Conflicting evidence, however, suggests that acculturation can also be associated with better mental health outcomes (Bhui et al., 2005; Fichter et al., 1988). The collective contribution of parental and youth acculturation to the risk of psychopathology in children is yet to be determined.

The second aspect of cultural experience is cultural stress, or acculturative stress, which is the degree to which individuals become distressed by pressures to adapt to cultural norms and values other than their own. Most work on cultural stress has focused on the effect that discrimination has on negative health outcomes, and more specifically on psychiatric problems (Karlsen & Nazroo, 2002; Lindstrom, 2007), including child psychopathology (Fisher, Wallace, & Fenton, 2000; Montgomery & Foldspang, 2007; Sam & Berry, 1995). Among Latino adolescents, cultural stress has been associated to mental health problems, mainly depression and anxiety (Hovey & King, 1996; Szalacha et al., 2003).

The current study

Exposure to cultures different from one's own is no longer restricted to persons who migrate to new countries. Global media and the domination of societies such as the U.S. in the world make it increasingly common that persons living, for example, in Latin America are exposed to Anglo culture and norms. These trends make it possible to separate the impact of minority status from general processes of acculturation and cultural distress when considering developmental risk for psychopathology.

We report longitudinal data from a unique study of families of Puerto Rican background living in the South Bronx, New York (SB) and the standard metropolitan area in San Juan, Puerto Rico (PR). Our goal is to examine the association between family cultural experience (acculturation and cultural stress) and child psychiatric symptoms (antisocial behaviors and internalizing symptoms) in each of these two contexts.

A special focus is the examination of acculturation and cultural stress among youth residing in PR. Given the political and economic dominance of the U.S. over the island, Puerto Rican youth living in PR may have a need to integrate to the Anglo/US culture, and thus may experience a significant level of acculturation and possibly of cultural stress even as they reside in their place of origin.

Examining an ethnic group both in its native environment and when it relocates to a different cultural context provides a unique opportunity to assess whether the relationships between cultural factors and child psychopathology that have been reported in the past are specific to a context in which the group is a minority. In this study we address two important questions: (1) Are youth and/or parent acculturation and cultural stress related to youth psychiatric symptoms, taking into account potential confounders, such as place of birth, age, gender, maternal education, stressful life events and parental psychopathology? And (2) Is the relationship between cultural factors and psychiatric symptoms constant or does it change over time?

Methods

Sample

The sample was drawn from the Boricua Youth Study (BYS) whose detailed design and methodology have been reported by Bird et al. (2006a). In brief, participants were recruited through probability sampling of households in the SB and PR. Eligibility for the original study required that at the time of enumeration a child 5-13 years and their parent/caretaker in the selected household. self-identify as being of Puerto Rican background. Up to three eligible children per household were selected to participate. The Institutional Review Boards of the New York State Psychiatric Institute and the University of Puerto Rico School of Medicine approved study procedures. Participants provided informed consent to participate in the study and could respond to the interview in English or Spanish. In the SB, 75% of the parents and 97% of the children chose English. All of the respondents in PR preferred Spanish. For the entire sample (N=2,951, age 5-13), baseline compliance rates were 80.5% for the SB and 88.7% in PR (Bird et al., 2006b). Site-specific sample retention in the two follow-ups one year apart was over 85% and has been described elsewhere (Bird et al., 2007).

The participants included in the analyses for this report are all the youth in the study aged 10 to 13 years (N=1,271) at the time of enumeration (SB n=598; PR n=673) and their parents. In this age stratum full data were available for both youth and parent. Information on study outcomes (ASB and internalizing symptoms) was available for 83.1% of the children in the SB at the second follow-up, and for 90% in PR.

Measures

Child Psychiatric Symptoms

Antisocial Behaviors (ASB) are assessed using parental responses to items from the conduct and oppositional defiant disorder schedules of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC-IV) (Shaffer, Fisher, Lucas, Dulcan, & Schwab-Stone, 2000), and child responses to the Elliot Delinquency Scale (Elliott, Huizinga, & Ageton, 1985). Using this information, Bird et al. (2005) developed an ordinal measure of antisocial behavior severity that takes into account frequency of antisocial behaviors, the seriousness or severity of those behaviors and whether multiple behaviors occur at one time. This measure, the Antisocial Behavior Severity Index (ASBSI), classifies children at one of six levels (0-5) at each wave. It has been used in previous reports (Bird et al., 2007), and is considered particularly appropriate for longitudinal analysis, as it allows a more subtle tracking of change than a diagnostic dichotomous indicator.

Internalizing symptoms are operationalized through symptom counts of the number of positive DISC-IV (Shaffer et al., 2000) symptoms of 6 psychiatric disorders (generalized anxiety, specific phobia, PTSD, separation anxiety, social phobia, major depression). The DISC-IV is a structured diagnostic instrument that ascertains DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) diagnostic criteria for different diagnoses.

Parent and youth information (Piacentini, Cohen, & Cohen, 1992) was used to calculate the internalizing symptom count. When both parent and child information was available, the symptom count for that disorder was the number of positive symptoms reported by the parent plus those reported by the child divided by two. The final symptom count was the sum of all positive symptoms across the 6 disorders. As a comprehensive examination of the longitudinal relationship between cultural factors and youth psychiatric problems, our choice was not to focus on specific psychiatric disorders, but on symptom level.

Acculturation

To measure adult and youth acculturation we used an adaptation of the Cultural Life Style Inventory (CLSI) (Mendoza, 1989; Magana et al., 1996). Whereas other scales of acculturation rely almost exclusively on language, the CLSI is more comprehensive. The original instrument is a 29-item scale administered to both parents and youth that has been used in both Spanish and English with Mexican-Americans. For the current study the scale was shortened (6 items for children and 9 items for parents applied at all study waves). The child scale include questions about language preference, ethnic origin of television programs watched, type of music preferred, the ethnicity of favorite artists or friends, and pride related to their ethnic background, with each item response ranging from only-Latino to only-Anglo. The parent measure additionally include questions about the ethnicity of people they admired; to whom they would like their child to get married; language(s) they would like their child to speak; and positive impact of cultural influences. Items were reworded from the Mexican version to be appropriate for Puerto Ricans. The scorable response options were: 1) Only Spanish/Puerto Rican or Latino; 2) Mostly Spanish/ PR or Latino; 3) Equally English/ Anglo or U.S. and Spanish/ PR or Latino; 4) Mostly English/ Anglo or U.S.; and 5) Only English/ Anglo or U.S.. A few persons specified cultural preferences other than Latino or Anglo, but these were coded as missing. The final scale score was the average of the items. The internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha) of the youth acculturation scale was 0.60 in the SB and 0.66 in PR. The one year test-retest reliabilities over waves (waves 1-2 and waves 2-3) were 0.52, 0.56 for SB and 0.63, 0.67 for PR. For the parental acculturation scale, alphas were 0.83 in the SB and 0.77 in PR at baseline, and the test-retest reliabilities were 0.71, 0.74 in SB and 0.66, 0.71 in PR.

We examine child and parent acculturation in two different ways: (a) as a continuous variable (in multiple regression analyses we use the average of the three time points centered by site-specific means); (b) as a 3-level categorical variable (baseline only), defined using cutoffs based in the within-site distribution of the acculturation scale scores: Latino/PR cultural orientation (less than one standard deviation below mean site value), Bicultural orientation (mean site value ± standard deviation), and Anglo/US cultural orientation (more than one standard deviation above mean site value). Site-specific cut scores were used because relative degree of acculturation may be context specific and because we carried out site-specific analyses.

Cultural Stress

Cultural stress is measured using a scale derived from the Hispanic Stress Inventory (Cervantes, Padilla, & Snyder, 1990) (13 items for the youth and 15 items for the parent). It taps different aspects of stress associated with the thrust towards acculturation. Because the scale was designed for a minority facing the challenge to relate to a different culture, some of the items may not apply to Puerto Ricans living in PR (e.g., people have treated you badly because you are Puerto Rican/Latino). Therefore, we selected four cultural stress items that would be applicable both to Puerto Ricans in the SB or in PR: (1) problems at school related to understanding English, (2) family conflicts about cultural customs, (3) difficulty mixing both cultures and (4) a feeling of not belonging to either culture. Each stress was endorsed as either being absent or present and was coded 0 or 1, and the scale score was the average of the four items. Items assessing cultural stress related to discrimination were not included in order to apply the same measure in both contexts. For the four item cultural stress scale, alphas at baseline were, for the youth version, 0.43 in the SB; 0.38 in San Juan; and for the parent version, 0.51 for both sites. For the full cultural stress scale, alphas were, for the youth version, 0.80 in SB and 0.75 in PR and for the parent version, 0.86 in SB and 0.82 in PR at baseline. The cultural stress measure used in multiple regression analyses is averaged across the three study time points and centered by the site-specific mean.

Other variables

Other variables are included in the analysis because they could be associated with either psychiatric symptoms or cultural factors. Since the values obtained on these variables were highly correlated across the three waves, for these additional variables, only baseline values are included. We define youth nativity as the youth's place of birth (PR/other Latin country or US/other non-Latin country) and parent nativity as the place of birth of the biological parents (both parent born in PR or at least one parent born in the US/other non-Latin country).

Stressful life events are measured by the Stressful Life Event Scale (Goodman et al., 1998) which is derived from the Stress Scale (Johnson & McKutcheon, 1980). This scale is administered to the child and includes past-year occurrence of 26 stress events. To be scored positive the event must be experienced as stressful and affecting the child ‘a lot’. The variable is dichotomized at two or more events.

Demographics included maternal education, measured by the highest educational level among maternal figures living in the home, as well as child age and gender.

Parental psychopathology is assessed by means of the Family History Screen for Epidemiologic Studies (FHE) (Lish, Weissman, Adams, Hoven, & Bird, 1995; Weissman et al., 2000), which screens for lifetime history of psychiatric illness in primary caregivers The conditions that were screened were depression, substance use, antisocial behavior and suicide attempts. Parental psychopathology was defined as possibly present if paternal or maternal figure screened positive on any condition included in the FHE. The psychometric study of the FHE (Weissman et al., 2000) revealed satisfactory test-retest reliability for self-report of the psychiatric illnesses included (kappa≥0.56, for self-reports 15 months apart) and sensitivity ranging from 56.0 to 86.8 and specificity ranging from 65.0 to 93.5 for best estimate diagnosis (8 clinicians).

Data Analysis

We first provide descriptive information for both sites on antisocial and internalizing symptoms, acculturation, cultural stress, demographics and other correlates of interest. Next we employ multilevel models (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002) to examine the relationship between cultural factors and child symptoms (antisocial or internalizing) over the three study waves (expressed as a linear trajectory) adjusting for correlates. To examine changes over time, we test the interaction of each cultural variable with time (baseline was coded as zero and subsequent assessments as 1 and 2). These analyses are site specific because the meaning of acculturation and cultural distress might differ in these two contexts. We assessed the robustness of our results in relation to loss to follow-up, different definition of cultural variables and source of information about psychiatric symptoms by examining alternative sets of models: 1) restricting the sample only to youth who had complete outcome data in the three study waves; employing alternative definitions of 2) acculturation; and 3) cultural stress; and 4) relying exclusively on child informed symptoms (possible for internalizing symptoms only). The data were weighted to account for the sampling design. Descriptive analyses are conducted using the statistical software SUDAAN Version 8.0 (Research Triangle, 2001) to account for clustering of the data. Multilevel models are carried out using the MIXED procedure of SAS with restricted maximum likelihood estimation, to take into account both sample weights and the multiple levels of nesting of the data.

Results

Table 1 shows the distribution of the study variables in the two sites. Children did not differ by site on the overall level of antisocial or internalizing symptoms in any study wave. As expected, a higher level of child and parental acculturation was evident in the SB compared to PR in all three waves. Results in the cultural stress scale were more varied: The children in PR reported higher levels of cultural stress on the 4 item scale than those in the SB in two waves, while parental levels of cultural stress did not differ by site.

Table 2 displays the correlations of antisocial and internalizing symptoms with selected baseline cultural variables for each wave and each site. Correlations are less than r=0.26, across site, type of disorder and wave. Acculturation associations are stronger for parent than youth acculturation: Youth acculturation is not significantly correlated with ASB or internalizing symptoms, whereas parent acculturation has a positive correlation with youth ASB across all waves (not statistically significant in the SB at wave 3). When cultural stress is considered, associations with youth cultural stress experiences appear to be stronger at baseline than at waves 1 and 2. Youth experiences have a positive correlation with ASB and internalizing symptoms at baseline, but in subsequent waves the only statistically significant correlation is with internalizing symptoms at wave 2 in PR. Parental cultural stress is positively correlated with internalizing symptoms in both sites at all three waves. Parental cultural stress is significantly correlated with ASB in PR only.

We used multilevel linear regression models to assess the association between cultural variables and patterns of child psychiatric symptoms over time. Table 3 displays the results of these analyses for ASB and internalizing symptoms. Analyses were conducted in the SB and PR separately. All models are adjusted by the levels of youth and parental acculturation and cultural stress averaged across waves as well as by baseline values of nativity, youth gender and age, maternal education, other stressful life events and parental psychopathology. Interactions of all cultural variables with time were tested and the interaction terms were included in the model when statistically significant.

Table 3 shows that ASB levels decreased over the two years of follow-up in both sites (b=-0.07, se=0.03, p=0.029 in the SB and b=-0.19, se=0.02 and p<0.0001 in PR), consistent with the previous report (Bird et al., 2007). The adjusted model shows that parent acculturation is related to youth ASB in both sites (b=0.20, se=0.09, p=0.023 in the SB and b=0.21, se=0.09 and p=0.024 in PR), and there was no evidence that these effects varied across time. In contrast, youth acculturation had virtually no association with ASB in either site. With the exception of parental cultural stress in the SB, cultural stress is positively associated with ASB.

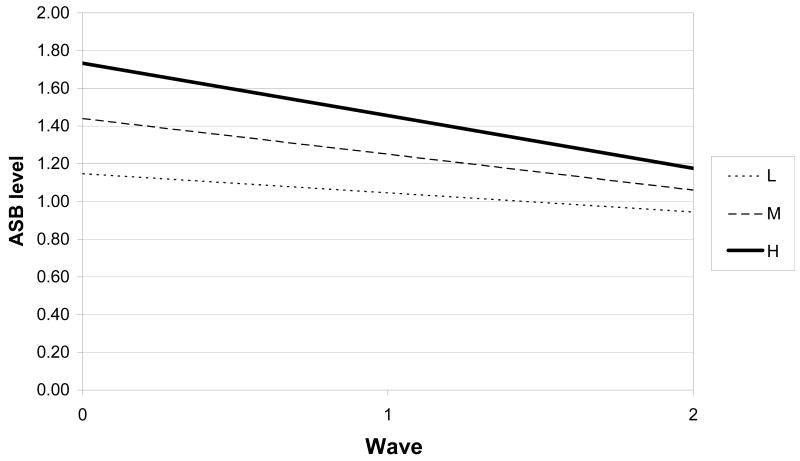

Parental cultural stress is significantly related to ASB in PR, but not in the SB. However, the SB effect is in the same direction as in PR, and the two estimates are not significantly different from each other (Z=0.55, ns); thus the SB results are inconclusive about the overall association. In PR youth cultural stress has a different impact on ASB over time (interactive effect between ASB and time is significant in PR: b=-0.63; se=0.20; p=0.0001). The overall effect is that at baseline (wave 0), high youth cultural stress levels predict higher ASBI scores with progressively weaker associations over the next two waves (Figure 1a).

Figure 1a. Trajectory of ASB among Puerto Rican Youth living in PR by Level of Youth Cultural Stress.

For internalizing symptoms a time trend was also found such that fewer symptoms were reported over time (see Table 3) (b=-1.98, SE=0.17, p<0.0001 in the SB and b=-2.72, se=0.13 p<0.0001 in PR). Unlike the results for ASB, neither acculturation variable was related to internalizing symptoms1, although results in PR were marginally significant (b=0.70, SE=0.42, p=0.082).

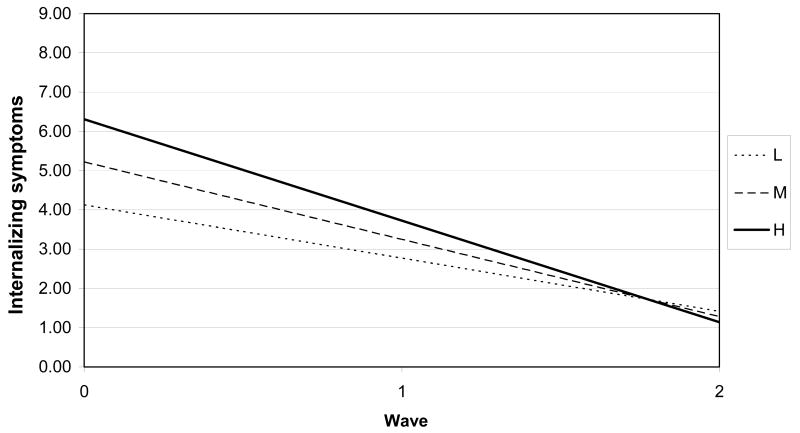

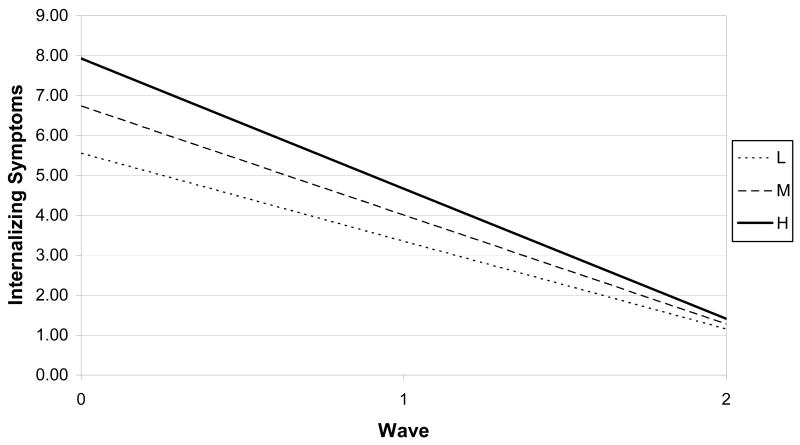

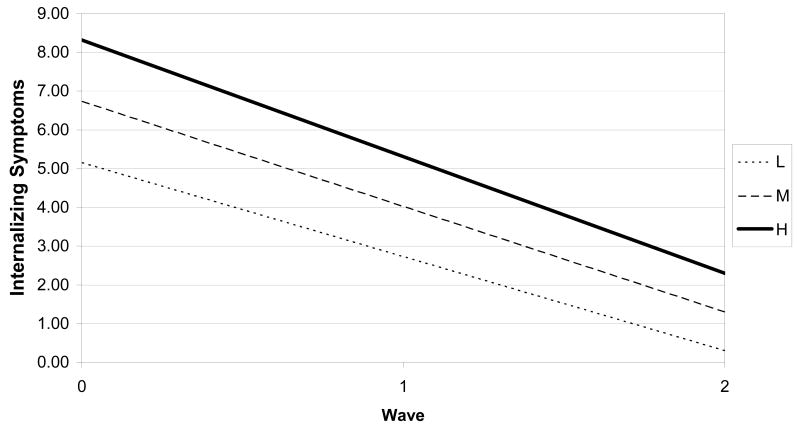

The association of youth cultural stress with internalizing symptoms over time follows the same pattern described above for ASB, with significant effects at baseline that diminish over time as indicated by interactive effects between time and youth cultural stress in both sites (Figures 1b, 1c) considerably weakening the effect of youth cultural stress in the SB and in PR. Somewhat differently from what was observed for ASB, the association between baseline parental cultural stress and internalizing symptoms over the three time points is positive in both sites, varying with time in PR, where it becomes weaker over time, although still positive at wave 2 (Figure 1d).

Figure 1b. Trajectory of Internalizing Symptoms among Puerto Rican Youth living in SB by Level of Youth Cultural Stress.

Figure 1c. Trajectory of Internalizing Symptoms among Puerto Rican Youth living in PR by Level of Youth Cultural Stress.

Figure 1d. Trajectory of Internalizing Symptoms among Puerto Rican Youth living in PR by Level of Parental Cultural Stress.

To be sure that the temporal effects were not due to dropout, we carried out the analyses restricting the sample to children in the sample who had complete data for all three study waves. The same pattern of results was obtained.

Because the notion of acculturation as a linear process has been questioned, we replaced the continuous variable indicating acculturation in the models by categorical definitions of acculturation (Latino/PR, Bicultural and Anglo/US), for the child and parent. This analysis was performed using baseline cultural variables only. Using bicultural orientation as the reference group, children of Anglo/US cultural orientation in PR had less ASB than Bicultural children (b=-0.37; se=0.12; p=0.0016). Also, in the SB we observed a trend f (p=0.06) for children of parents who defined themselves as more Latino oriented, to have less internalizing symptoms when compared with children of Bicultural parents.

When we examined the effect of cultural stress using the original full cultural stress scale, the same pattern of associations obtained with the abbreviated cultural stress measure was observed, with regression coefficients increasing substantially when the full measure was used (e.g., in the final model predicting internalizing symptoms, b=21.05; se=2.28; p<0.0001 in the SB and b=19.51; SE=2.25; p<0.0001 in PR).

Discussion

We assessed, over time, the relationship between cultural factors and youth psychiatric symptoms among Puerto Rican children by examining parental and youth acculturation and cultural stress in two contexts: the SB and PR. The results indicate that (a) certain cultural factors are correlated with specific psychiatric symptoms in youth at both sites, even though the magnitude of the correlations is modest; (b) Youth acculturation is not associated with any type of symptoms at either site; (c) Parent acculturation is associated with youth ASB symptoms at both sites; (d) Youth cultural stress level is associated with psychiatric symptoms (ASB and internalizing) in children at both sites, and, in general, the strength of these associations decrease over time; (e) Parental cultural stress level is also related to both types of psychiatric symptoms across sites (the exception is ASB symptoms in the SB) with the effect decreasing over time for internalizing symptoms in PR only. (f) There are no indications that findings are a consequence of loss to follow-up, of the definitions of acculturation or cultural stress employed, or of symptom informant (except in the case of youth acculturation).

The current investigation has the advantage of having clearly operationalized acculturation and cultural stress and also of including well defined outcomes based on parent and youth information about youth psychiatric symptoms ascertained by means of a structured diagnostic interview. The study design, only executed previously in a smaller scale (Velez & Ungemack, 1995; Anagnostopoulos et al., 2004), permitted the evaluation of youth of the same ethnicity in two different contexts, identified through similar probabilistic sampling strategies, and assessed with the same measures longitudinally.

The focus on cultural factors in two distinct contexts presented the challenge of choosing between an universalistic versus a localized approach to define different aspects of the cultural experience in a meaningful way (Lewis-Fernandez & Kleinman, 1995). A case-by-case approach was adopted to respond to this challenge; for example, the same questions to measure acculturation were employed at both sites, but site-specific cut-points were used to define three cultural orientation categories (Latino, Bicultural and Anglo/US). In the case of cultural stress, a more universalistic approach was employed by selecting four items that would be applicable to the SB and the PR, but we also report results based on the full cultural stress scale, which includes cultural experiences whose meaning in PR is not clear (e.g., ethnic discrimination).

Higher levels of parent acculturation were related to more youth ASB symptoms over time, a finding that is consistent with studies describing an increase in psychopathology with greater acculturation among adults (Vega et al., 1998) or lower levels of mental health problems in ethnic minority adolescents compared to non-minority (Fichter et al., 1988; Stansfeld et al., 2004). It is possible that low parental acculturation among Puerto Ricans represents identification with Latino values associated with key protective factors such as family stability and cohesiveness (Gil & Vega, 1996). Such identification could indicate specific parental behaviors that may prevent the escalation of youth antisocial behaviors in both sites.

The lack of an association of youth acculturation with either ASB or internalizing symptoms may be due in part to the limited reliability of the acculturation measure in youth. Both internal consistency and test-retest estimates of reliability were approximately 0.60 for this measure in both sites, and this suggests that the strength of the associations were attenuated by measurement error. However, the correlations of youth acculturation were very small, therefore it is unlikely that such correlations corrected for attenuation would be substantial. Thus our findings do not support the notion that acculturation is related to youth mental health. In addition, when we considered categorical definitions of acculturation, our results do not support the hypothesis that bicultural orientation is associated with better outcomes, a formulation that has conceptual support (Rudmin, 2003). Quite the opposite was observed in PR, where youth biculturality being related to elevated youth ASB compared to youth Anglo/US cultural orientation.

Cultural stress explains child psychiatric symptoms among Puerto Rican children more consistently than acculturation. This finding suggests that it is not necessarily the level of involvement with another culture that might have adverse consequences, but the extent to which this involvement is experienced as distressing. While this notion may be oversimplified, it has not been clearly articulated in studies concerned with the issue of acculturation. Quite the contrary, some believe that because of its conceptual and measurement imprecision (Cabassa, 2003; Lara, Gamboa, Kahramanian, Morales, & Bautista, 2005), the notion of acculturation in health research has in many cases diverted attention from the actual causes of disparities (Hunt, Schneider, & Comer, 2004). Our results indicate that to understand children's psychiatric symptoms in relationship to cultural adaptation, it is critical to consider the stress that may be involved in the acculturative process, as well as the fact that such influence may decrease over time.

The role of cultural stress as a possible determinant of psychiatric symptoms in PR can be understood within the broader context of the relationships between PR and the US. PR has been in a colonial relationship with the United States for over 100 years. It has been traditionally postulated in this interaction that despite the pressure to adopt the values of the dominant power among the colonized at the expense of self-reproach (Fanon, 1969; Memmi, 1971; Bird, 1982), the clash between two dominant cultures within the Puerto Rican context has not resulted in the absorption and disappearance of the Puerto Rican culture. Recent years have evidenced an increase in the proportion of adherents to the view that PR's political future should be to become a State in the American Union. Nevertheless, even the proponents of this view express their cultural ambivalence by promulgating a multicultural “state”, different from any other state in the union. Our findings suggest that the pressure towards assimilation seems to exert some degree of cultural stress among children in PR that is in turn related to the levels of psychiatric symptoms in the youth population.

Limitations of the present study include the low reliability of the youth acculturation measure employed. It is possible, therefore, that the lack of association between youth acculturation and psychiatric symptoms reflects measurement error rather than the actual relationship between the two constructs examined. The measurement of different dimensions of cultural experience in different contexts is certainly a challenge and future studies should devote considerable effort to use measures capable of assessing a broad range of cultural experiences.

Another limitation is that it is unclear whether these findings will generalize to children from other Latino populations or from other cultural groups. Studying the Puerto Rican population has the advantage of not confounding the stress related to legal status with other cultural issues. Puerto Ricans, although a culturally distinct group, are U.S. citizens who can move freely between the island of PR and mainland U.S. This same fact however, may make Puerto Ricans quite unique compared to illegal immigrants from other Latino subgroups or other immigrant groups in the US. These results, however, may still apply to other ethnic groups legally admitted in a country, as they are be exposed to a different culture and such exposure may become a source of distress. Migration is a ubiquitous and growing phenomenon, that involves millions of individuals. Driven by increased globalization and dramatic demographic changes its effects are felt in both highly developed and underdeveloped nations. More dynamic policy responses are necessary to keep pace with the different issues related to this phenomenon. From a public health perspective, if our results were to replicate in other ethnic groups, it would be interesting to determine if interventions targeted to those individuals with high levels of cultural stress can be successful in curtailing youth's psychiatric symptoms. In less developed settings, such as Puerto Rico, where immigration to a more developed context is a frequent event, it is important to consider the participation of cultural distress in determining youth psychopathology.

In conclusion, the current analyses indicate that cultural factors, particularly cultural stress appear to contribute similarly to psychiatric symptoms among Puerto Rican youth in two contexts, one in which they are a minority group and another in which they live in their place of origin. Therefore, the impact of stressful cultural experiences on youth mental health may not be limited to youth who are part of a minority cultural group, but may extend to those who, not being a minority, live in a globalized world, where different cultures are trying to coexist.

Acknowledgments

An earlier version of this paper was awarded the Outstanding Oral Presentation Award when it was presented at the Conference “Culture and Psychiatric Diagnosis: Towards DSM-V”, Critical Research Issues in Latino Mental Health; November 7th & 8th, 2003, Princeton, NJ. The authors acknowledge helpful comments made by Dr. William Vega. Data for this study was obtained through NIMH grant: Antisocial Behaviors in U.S. and Island Puerto Rican Youth (MH56401) (Hector R. Bird, M.D., Principal Investigator).

Abbreviations

- DSM-IV

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Version IV

- DISC-IV

Diagnostic Schedule for Children, Version IV

- SB

South Bronx

- PR

Standard Metropolitan Area in San Juan, Puerto Rico

- BYS

Boricua Youth Study

- ASB

Antisocial behaviors

Footnotes

Auxiliary analyses revealed a different pattern of results in PR only for the association between youth acculturation and internalizing symptoms: youth acculturation was significantly positively related to youth reports of internalizing (b=1,77;se=0.49; p<0.05) but significantly negatively related to parental reports of internalizing symptoms (b=-1,27; se=0.52; p<0.05).

Reference List

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Anagnostopoulos DC, Vlassopoulou M, Rotsika V, Pehlivanidou H, Legaki L, Rogakou E, et al. Psychopathology and mental health service utilization by immigrants' children and their families. Transcult Psychiatry. 2004;41:465–486. doi: 10.1177/1363461504047930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beiser M, Hou F, Hyman I, Tousignant M. Poverty, family process, and the mental health of immigrant children in Canada. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:220–227. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.2.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhui K, Stansfeld S, Head J, Haines M, Hillier S, Taylor S, et al. Cultural identity, acculturation, and mental health among adolescents in east London's multiethnic community. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59:296–302. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.014456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird HR. The cultural dichotomy of colonial people. Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis. 1982;10:195–209. doi: 10.1521/jaap.1.1982.10.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird HR, Canino GJ, Davies M, Duarte CS, Febo V, Ramirez R, et al. A study of disruptive behavior disorders in Puerto Rican youth: I. Background, design, and survey methods. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006a;45:1032–1041. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000227878.58027.3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird HR, Davies M, Canino GJ, Loeber R, Rubio-Stipec M, Shen S. Classification of antisocial behaviors along severity and frequency parameters. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2005;14:325–341. [Google Scholar]

- Bird HR, Shrout PE, Davies M, Canino G, Duarte CS, Shen S, et al. Longitudinal development of antisocial behaviors in young and early adolescent Puerto Rican children at two sites. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46:5–14. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000242243.23044.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird HR, Shrout PE, Davies M, Canino GJ, Duarte CS, Sen S, et al. Longitudinal Trends in the Development of Antisocial Behaviors In Young And Early Adolescent Puerto Rican Children at Two Sites. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000242243.23044.ac. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau J, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Borges G, Castilla-Puentes RC, Kendler KS, Medina-Mora ME, et al. Mental disorders among English-speaking Mexican immigrants to the US compared to a national sample of Mexicans. Psychiatry Res. 2007;151:115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabassa LJ. Measuring acculturation: Where we are and where we need to go. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2003;25:127–146. [Google Scholar]

- Canabal ME, Quiles JA. Acculturation and Socioeconomic-Factors As Determinants of Depression Among Puerto-Ricans in the United-States. Social Behavior and Personality. 1995;23:235–246. [Google Scholar]

- Canino GJ, Roberts RE. Suicidal behavior among Latino youth. Suicide and Life-threatening Behavior. 2001 31:122–131. doi: 10.1521/suli.31.1.5.122.24218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes RC, Padilla AM, Snyder NS. Reliability and validity of the Hispanic Stress Inventory. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1990;12:76–82. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DS, Huizinga D, Ageton S. Explaining Delinquency and Drug Use. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Fanon F. Los Condenados de la Tierra. [Les Damnes de la Terre]. Mejico: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Fichter MM, Elton M, Diallina M, Koptagel-Ilal G, Fthenakis WE, Weyerer S. Mental illness in Greek and Turkish adolescents. Eur Arch Psychiatry Neurol Sci. 1988;237:125–134. doi: 10.1007/BF00451279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher CB, Wallace SA, Fenton RE. Discrimination distress during adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2000;29:679–695. [Google Scholar]

- Gil AG, Vega WA. Two different worlds: Acculturation stress and adaptation among Cuban and Nicaraguan families. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1996;13:435–456. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R, Richards H. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Presentations of 2Nd-Generation Afro-Caribbean in Britain. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;167:362–369. doi: 10.1192/bjp.167.3.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Hoven CW, Narrow WE, Cohen P, Fielding B, Alegria M, et al. Measurement of risk for mental disorders and competence in a psychiatric epidemiologic community survey: the National Institute of Mental Health Methods for the Epidemiology of Child and Adolescent Mental Disorders (MECA) Study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 1998;33:162–173. doi: 10.1007/s001270050039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Hasin DS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Anderson K. Immigration and lifetime prevalence of DSM-IV psychiatric disorders among Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic whites in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:1226–1233. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.12.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovey JD, King CA. Acculturative stress, depression, and suicidal ideation among immigrant and second-generation Latino adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35:1183–1192. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199609000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt LM, Schneider S, Comer B. Should “acculturation” be a variable in health research? A critical review of research on US Hispanics. Social Science & Medicine. 2004;59:973–986. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JH, McKutcheon SM. Assessing life stress in older children and adolescents: preliminary finding with Life Events Checklist. In: Sarason IG, Spielberger CD, editors. Stress and anxiety. Washington DC: Hemisphere; 1980. pp. 111–125. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan MS, Marks G. Adverse-Effects of Acculturation - Psychological Distress Among Mexican-American Young-Adults. Social Science & Medicine. 1990;31:1313–1319. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(90)90070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsen S, Nazroo JY. Relation between racial discrimination, social class, and health among ethnic minority groups. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:624–631. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.4.624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King M, Nazroo J, Weich S, McKenzie K, Bhui K, Karlsen S, et al. Psychotic symptoms in the general population of England--a comparison of ethnic groups (The EMPIRIC study) Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2005;40:375–381. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0900-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara M, Gamboa C, Kahramanian M, Morales LS, Bautista DH. Acculturation and Latino health in the United States: A review of the literature and its sociopolitical context. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26:397. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Fernandez R, Kleinman A. Cultural psychiatry. Theoretical, clinical, and research issues. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 1995;18:433–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindstrom M. Social capital, anticipated ethnic discrimination and self-reported psychological health: A population-based study DOI. Social Science & Medicine. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lish JD, Weissman MM, Adams PB, Hoven CW, Bird H. Family psychiatric screening instruments for epidemiologic studies: pilot testing and validation. Psychiatric Research. 1995;57:169–180. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(95)02632-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magana JR, delaRocha O, Amsel J, Magana HA, Fernandez MI, Rulnick S. Revisiting the dimensions of acculturation: Cultural theory and psychometric practice. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1996;18:444–468. [Google Scholar]

- Memmi A. Retrato del Colonizado. [Portrait of the Colonized]. Madrid: 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza RH. An empirical scale to measure type and degree of acculturation in Mexican-American adolescents and adults. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1989;20:372–385. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery E, Foldspang A. Discrimination, mental problems and social adaptation in young refugees. The European Journal of Public Health. 2007 doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckm073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel NC, Delbello MP, Strakowski SM. Ethnic differences in symptom presentation of youths with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8:95–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piacentini JC, Cohen P, Cohen J. Combining discrepant diagnostic information from multiple sources: are complex algorithms better than simple ones? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1992;20:51–63. doi: 10.1007/BF00927116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SA, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. 2nd. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Redfield R, Linton R, Herskovits MJ. American Antropologist. 1936;38:149–152. [Google Scholar]

- Rudmin FW. Critical history of the acculturation psychology of assimilation, separation, integration, and marginalization. Review of General Psychology. 2003;7:3–37. [Google Scholar]

- Sam DL, Berry JW. Acculturative Stress Among Young Immigrants in Norway. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. 1995;36:10–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.1995.tb00964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, Schwab-Stone ME. NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): Description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Canino GJ, Bird HR, Rubio-Stipec M, Bravo M, Burnam MA. Mental health status among Puerto Ricans, Mexican Americans, and non- Hispanic whites. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1992;20:729–752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stansfeld SA, Haines MM, Head JA, Bhui K, Viner R, Taylor SJ, et al. Ethnicity, social deprivation and psychological distress in adolescents: school-based epidemiological study in east London. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185:233–238. doi: 10.1192/bjp.185.3.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szalacha LA, Erkut S, Garcia CC, Alarcon O, Fields JP, Ceder I. Discrimination and Puerto Rican children's and adolescents' mental health. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2003;9:141–155. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.9.2.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolmac J, Hodes M. Ethnic variation among adolescent psychiatric in-patients with psychotic disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:428–431. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.5.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, Kolody B, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alderete E, Catalano R, Caraveo-Anduaga J. Lifetime prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders among urban and rural Mexican Americans in California. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:771–778. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.9.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velez CN, Ungemack JA. Psychosocial correlates of drug use among Puerto Rican youth: generational status differences. Social Science & Medicine. 1995;40:91–103. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)e0062-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Wickramaratne P, Adams P, Wolk S, Verdeli H, Olfson M. Brief screening for family psychiatric history: the family history screen. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57:675–682. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.7.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]