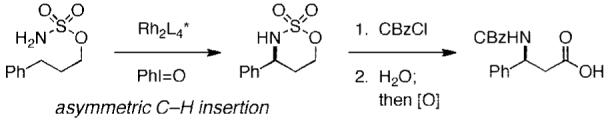

Catalytic intramolecular C—H amination has advanced as a general technology for chemical synthesis.1 The utility of the heterocyclic products fashioned from such processes validates efforts to identify chiral transition-metal complexes capable of effecting asymmetric insertion (Figure 1). On a more fundamental level, the challenges associated with the design of a catalytic system able to support a reactive oxidant that can discriminate between two hydrogen atoms on a prochiral methylene center are significant. Nonetheless, success of this type has been realized in enantioselective C—H insertion reactions of diazoalkane derivatives and in select instances involving intra- and intermolecular C—Hamination.2-5 This report describes the development and performance of Rh2(S-nap)4, a valerolactam-derived dirhodium complex that affords some of the highest levels of asymmetric control to date in cyclization reactions of sulfamate esters. The strong preference of this catalyst for promoting allylic C—H bond insertion is also highlighted.

Figure 1.

Optically active amine derivatives through C—H amination.

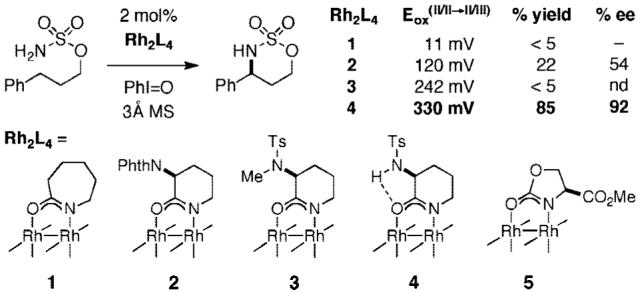

Our earliest efforts to identify chiral catalysts for asymmetric C—H amination focused primarily on dirhodium tetracarboxylate complexes derived from α-amino acids. In all cases examined, cyclized sulfamate products were formed with conspicuously poor enantiomeric induction (0-20% ee). Studies to evaluate % ee as a function of product conversion clearly established that the enantiomeric ratio was decreasing over the reaction time course. Such results are indicative of a change in catalyst structure owing to the lability of the bridging carboxylate groups. Our interest thus turned toward alternative classes of ligands including carboxamide-based designs. In principle, the strongly donating carboxamidate groups increase the capacity of the dirhodium centers for backbonding to the π-acidic nitrene ligand, thus affording a more stable and potentially more discriminating oxidant.6,7 Unfortunately, simple dirhodium tetracarboxamidate complexes such as Rh2(cap)4 1 are ineffective catalysts for C—H amination because of their propensity to undergo facile one-electron oxidation when combined with PhI(OAc)2 or related hypervalent iodine reagents (Figure 2).8 The resulting mixed-valent Rh2+/Rh3+ dimer appears to be catalytically inactive for C—H amination. Accordingly, in order for a dirhodium carboxamide to promote nitrene-mediated insertion, we concluded that its oxidation potential would have to be increased significantly relative to that of Rh2(cap)4.

Figure 2.

Evaluating catalyst performance for C—H amination.

The basis for the design of Rh2(S-nap)4 4 was Rh2(PTPI)4 2, a complex originally developed by Hashimoto for asymmetric alkene cyclopropanation (Figure 2).9 The measured Rh2+/Rh2+→Rh2+/Rh3+ redox potential for Rh2(PTPI)4 is 120 mV vs SCE, marking the rather significant influence of the proximal phthalimide group on the donating strength of the carboxamidate ligand.10 We reasoned that replacement of the phthalimide moiety with a 2° sulfonamide would allow for intramolecular hydrogen bonding between the N-H and the carbonyl oxygen of the amide, further shifting the rhodium oxidation to higher potential. The recorded CV data for both Rh2(S-nap)4 4 and its N-methylated analogue 3 confirm this hypothesis (330 and 242 mV, respectively).

Test reactions with 3-phenylpropylsulfamate, PhI=O, 3 Å molecular sieves, and 2 mol% of the rhodium dimer revealed the importance of the sulfonamide N-H group on catalyst performance (Figure 2). Rh2(S-nap)4 is notably more effective than either Rh2(PTPI)4 2 or the N-methylated complex 3. Although these data appear to show some link between catalyst turnover number and redox potential, other factors are clearly influencing the efficiency of this process. This fact is exemplified with Rh2(4S-MEOX)4 5, a complex that has a relatively high oxidation potential of 742 mV but affords <10% of the cyclized product under standard reaction conditions.7 In comparison to Rh2(S-nap)4, the architecture of the 4S-MEOX ligand severely crowds the axial sites on the rhodium centers. It is our feeling that steric effects between the ligands and substrate are exacerbated in the 4S-MEOX system, thus adversely affecting the rate of the C—H insertion event and, in turn, the overall performance of the reaction.

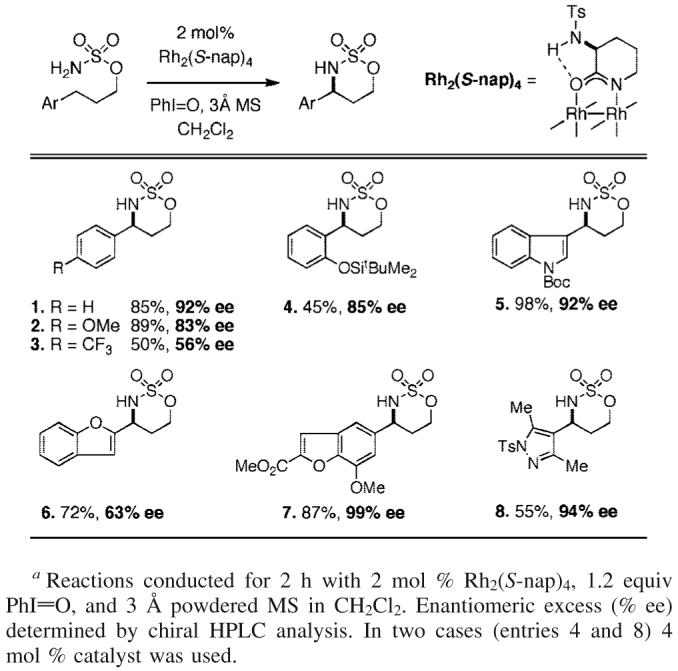

Rh2(S-nap)4, is an effective catalyst for oxidation reactions with 3-aryl-substituted propylsulfamate esters (Table 1). Enantiomeric excesses are generally >80%, and the conditions tolerant of most common functional groups. In one case, the isolated heterocycle (entry 1) has been converted to the corresponding (S)-N-CBz-β-amino acid following a two-step protocol (see Figure 1).11 This correlation establishes the absolute stereochemistry of the product in entry 1 as S.12,13

Table 1.

Enantioselective Cyclization of Sulfamate Estersa

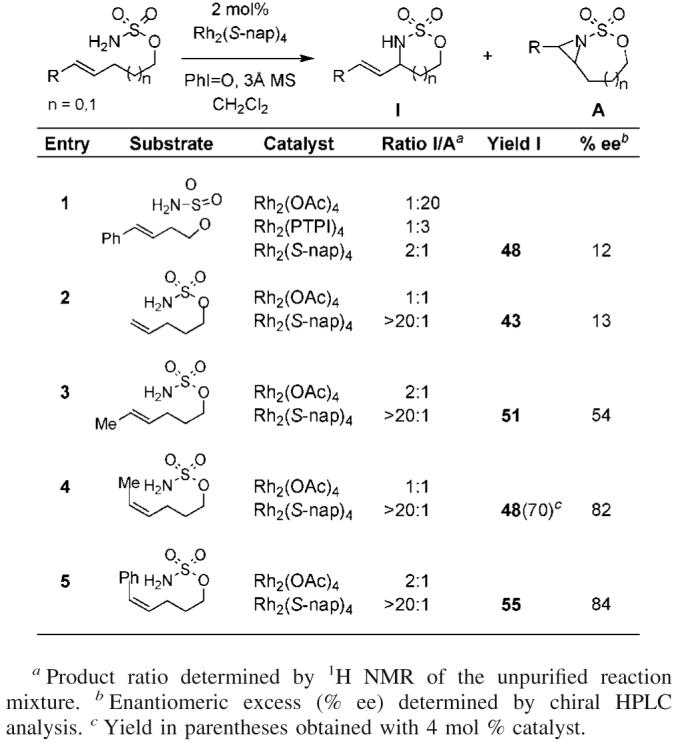

Cognizant of the fact that aziridination of homoallyl sulfamates is highly favored with Rh-tetracarboxylate catalysts, we were surprised to observe the five-membered sulfamidate as the major product in the reaction promoted by Rh2(S-nap)4 (entry 1, Table 2).1b This particular result is striking given the strong preference for sulfamate esters to yield six-membered ring heterocycles and the fact that the closely related Rh2(PTPI)4 catalyst affords primarily the aziridine. The bias for Rh2(S-nap)4 toward allylic insertion appears to be general, occurring with both styrenyl and non-styrenyl olefins. Cis olefins perform optimally in these reactions to give vinyl-substituted oxathiazinanes with enantiomeric excesses >80%. Although levels of asymmetric induction are modest for trans and terminal olefins, allylic C—H insertion is still favored.

Table 2.

Chemoselective Allylic C—H Bond Insertion

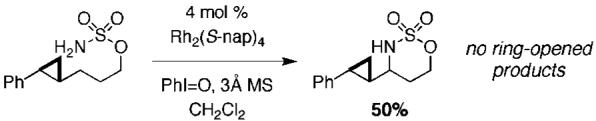

The remarkable influence of Rh2(S-nap)4 on chemoselectivity intimates a possible change in mechanism from the concerted-asynchronous nitrene pathway generally accepted for dirhodium tetracarboxylate-promoted reactions (e.g., Rh2(OAc)4).14,15 To test for the possibility that a stepwise, radical C—H abstraction/rebound may be operative, a cyclopropane clock substrate was submitted to the amination protocol (Figure 3). No products of cyclopropane ring opening are obtained from this reaction, a result consistent with a concerted, nitrene-type oxidation.16

Figure 3.

Results suggestive of a concerted insertion mechanism.

Rh2(S-nap)4 displays unprecedented performance for the enantioselective intramolecular amination of benzylic and allylic C—H bonds. Despite our still nascent understanding of the factors that influence catalyst turnover numbers and asymmetric control, the design and development of this unique dirhodium complex should further advance methods for C—H functionalization. Continued efforts in this laboratory will attempt to elucidate the nuanced relationship between oxidation potential, ligand structure, and substrate design on catalytic function.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

D.N.Z. is supported by an Achievement Rewards for College Scientists (ARCS) Foundation Stanford Graduate Fellowship. This work has been made possible in part by a grant from the NIH and with gifts from Pfizer, Amgen, and GlaxoSmithKline.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: General experimental protocols and characterization data for all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- (1).(a) Davies HML, Manning JR. Nature. 2008;451:417. doi: 10.1038/nature06485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Espino CG, Du Bois J. In: Modern Rhodium-Catalyzed Organic Reactions. Evans PA, editor. Wiley-VHC; Weinheim, Germany: 2005. pp. 379–416. [Google Scholar]

- (2).For a general reference to reactions of diazoalkanes, see: Doyle MP, McKervey MA, Ye T. Modern Catalytic Methods for Organic Synthesis with Diazo Compounds: From Cyclopropanes to Ylides. Wiley and Sons, Ltd.; New York: 1997. .

- (3).(a) Yamawaki M, Kitagaki S, Anada M, Hashimoto S. Heterocycles. 2006;69:527. [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhang J, Chan PWH, Che C-M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005;46:5403. [Google Scholar]; (c) Fruit C, Müller P. Helv. Chim. Acta. 2004;87:1607. [Google Scholar]; (d) Liang J-L, Yuan S-X, Chan PWH, Che C-M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:5917. [Google Scholar]; (e) Liang JL, Yuan S-X, Huang J-S, Yu W-Y, Che C-M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002;41:3465. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020916)41:18<3465::AID-ANIE3465>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Yamawaki M, Tsutsui H, Kitagaki S, Anada M, Hashimoto S. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:9561. [Google Scholar]

- (4).(a) Reddy RP, Davies HML. Org. Lett. 2006;8:5016. [Google Scholar]; (b) Omura K, Murakami M, Uchida T, Irie R, Katsuki T. Chem. Lett. 2003;32:354. [Google Scholar]; (c) Kohmura Y, Katsuki T. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:3339. [Google Scholar]

- (5).For a diastereoselective intermolecular C—H amination catalyzed by a chiral dirhodium complex, see: Liang C, Collet F, Robert-Peillard F, Müller P, Dodd RH, Dauban P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:343. doi: 10.1021/ja076519d.. Liang C, Robert-Peillard F, Fruit M, Müller P, Dodd RH, Dauban P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006;45:4641. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601248..

- (6).Similar arguments have been put forth for rhodium-catalyzed carbene transformations. See Padwa A, Austin DJ, Price AT, Semones MA, Doyle MP, Protopopova MN, Winchester WR, Tran A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:8669..Pirrung MC, Morehead AT. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:8991.

- (7).Doyle MP, Ren T. In: Progress in Inorganic Chemistry. Karlin K, editor. Vol. 49. Wiley; New York: 2001. pp. 113–168. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Similar observations have been made with other types of oxidants, see: Doyle MP. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:9253. doi: 10.1021/jo061411m., and references therein.

- (9).Watanabe N, Matsuda H, Kuribayashi H, Hashimoto S. Heterocycles. 1996;42:537. [Google Scholar]

- (10).By contrast, Rh2(OAc)4 has an oxidation potential of 1150 mV vs. SCE.

- (11).Espino CG, Wehn P, Chow J, Du Bois J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:6935. [Google Scholar]

- (12).All other compounds are assumed to have formed with the same absolute sense of induction.

- (13).Zemlicka J, Bhuta A, Bhuta P. J. Med. Chem. 1983;26:167. doi: 10.1021/jm00356a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).(a) Müller P, Baud C, Naägeli I. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 1998;11:597. [Google Scholar]; (b) Fiori KW, Du Bois J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:652. doi: 10.1021/ja0650450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).A recent DFT study supports a concerted mechanism, see: Lin X, Zhao C, Che C-M, Ke Z, Phillips DL. Chem. Asian J. 2007;2:1101. doi: 10.1002/asia.200700068.

- (16).Recovered starting material accounts for the mass balance. While compelling, these data cannot definitively rule out a stepwise pathway.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.