Abstract

Purpose

To examine the thermal effects of physiological response to heating during exposure to radiofrequency (RF) electromagnetic fields in Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) with a head-specific volume coil.

Materials and Methods

Numerical methods are used to calculate the temperature elevation in MRI of the human head within volume coils from 64 MHz to 400 MHz at different power levels both with and without consideration of temperature-induced changes in rates of metabolism, perspiration, radiation, and perfusion.

Results

At the highest power levels currently allowed in MRI for head volume coils, there is little effect from physiological response as predicted with existing methods. This study does not rule out the possibility that at higher power levels or in different types of coils (such as extremity or whole-body coils) the physiological response may have more significant effects.

Conclusion

In modeling temperature increase during MRI of the human head in a head-sized volume coil at up to 3.0 W/kg head-average SAR, it may not be necessary to consider thermally-induced changes in rates of metabolism, perfusion, perspiration, and radiation.

Keywords: model, SAR, temperature, head, physiology

INTRODUCTION

In an MRI exam, the patient is exposed to numerous pulses of RF energy, which introduce heat into the tissue. Local and average Specific energy Absorption Rates (SAR) are basic parameters often used to evaluate the safety of the sequence of applied pulses. However, local SAR levels are not easy to measure accurately in experiment. Tissue heating is dependent not only on SAR at a given location, but also on thermal and physiological properties there and in surrounding regions, and on heat transfer mechanisms. In order to assess the risk of inducing hyperthermic tissue damage, the temperature increase under RF exposure can be computed (1). The International Electrotechnical Commission currently recommends that for normal operation local temperatures should not exceed 38°C in the head, 39°C in the torso, or 40°C in the extremities, and that the core body temperature not be increased by more than 0.5°C (1).

Calculations of the effects of MRI on temperature for the human head in a volume coil have been presented previously (2, 3). In these works the Finite Difference Time Domain (FDTD) method was used to calculate the field and SAR distributions within specific RF resonators at a variety of frequencies, and then a finite difference implementation of the bioheat equation was used to calculate the resulting increase in temperature for each case. Also in these works a general mechanism for heat loss to the environment was used without explicit consideration of heat losses due to separate mechanisms of convection, respiration, radiation, and evaporation. It was found that when a head-specific volume coil was used to maintain a whole-head average SAR of 3.2 W/kg until a new steady-state temperature distribution was achieved, temperature increases of up to 2.4°C could be seen in muscle within the head, though temperature increases in the brain (with higher perfusion rates) was limited to less than 1°C (2). As expected, lower whole-head average SAR levels for limited time periods caused lower maximum temperature increases (3). In both works, the maximum temperature would exceed 38°C in the head (though not in the brain) after exposure to a whole-head average SAR of 3.2 W/kg for a reasonable time (2, 3). These previous studies for MRI did not consider the effects of thermally-induced changes in metabolic rate and local blood flow. These thermoregulatory mechanisms have been considered in areas other than for MRI. Hand et al. considered thermally-induced physiological changes when investigating the temperature distribution of a three-layer planar model of tissue exposed to RF heating as in diathermy (4) Hoque and Gandhi (5) considered thermally-induced physiological changes when investigating the temperature distribution in the human leg for VLF-VHF exposures, as did Bernardi et al. (6) when analyzing the SAR and temperature of a subject under the exposure of far-field RF sources. Sturesson and Andersson-Engels (7) provided a mathematical model considering thermally-induced physiological changes for predicting the temperature distribution in their laser hyperthermia work. Here we investigate a mathematical model including thermally-induced physiological changes for MRI of a head in a TEM-type volume coil.

In this paper, we present the SAR and temperature of a human head inside a TEM coil operating at 64MHz (1.5T), 200 MHz (4.7T), 300 MHz (7T), 340 MHz (8T) and 400 MHz (9.4T). SAR is calculated using the FDTD method and the temperature distribution is calculated using the Pennes bio-heat equation (8) combined with temperature-dependent formulations for radiated heat, perfusion rates, and metabolic rates. We compared the results with and without these temperature-dependent formulations in a three-dimensional (3D) anatomically realistic human head model.

METHODS

SAR Calculation

The head and coil model used in this work matched those in a previously-published work (9). Briefly, a TEM coil (10) loaded with a model of the human head (11) was modeled using a home-built implementation of the FDTD method (12, 13). The head model included a significant portion of the shoulders extending outside the coil to avoid unrealistic boundary effects within the region of high RF fields. The coil had 16 copper elements, a 30-cm inner diameter, and a 16-cm length. Each rung was 1-cm wide. The diameter and length of the shield were 38 cm and 24 cm, respectively. Current sources were placed in each of four break points of each rung of the MRI coil and a 22.5-degree phase-shift was set between currents in adjacent rungs. Although this method for modeling the drive configuration may not allow for current distribution to be affected by the load (14), it has shown very good agreement with simulations (15) and experiment (16) using a tuned coil driven in quadrature. The degree of agreement may depend on the frequency, type of coil, and degree of asymmetry in the load. In this work, which is focusing on the effects of physiological response to temperature, use of a consistent coil current distribution limits the number of confounding variables. Finally, use of multiple sources in experiment shows great promise for the future of MRI (17–20) and is increasingly seen in experiment (21). All models had a resolution of 3mm in each direction. An eight-layer Berenger’s Perfectly Matched Layer (22) was adopted as the absorption boundary. A 4-Cole-Cole extrapolation technique (23) was used with parameters from the literature (24) to determine values for the dielectric properties of the tissues at each frequency. The SAR was determined at each location from the calculated electric field as

| [1] |

where E is the peak local electric field within the tissue and ρ is the local tissue density. Values for ρ were obtained from the literature (9).

Thermal Modeling

Fundamental algorithm for temperature calculations

The temperature distribution can be modeled by using the bio-heat equation, which takes into account perfusion by blood, heat of metabolism, thermal conduction, and SAR (8)

| [2] |

in combination with a boundary condition that considers convection, evaporation of sweat, and radiation (5, 6).

| [3] |

Here ρ is the tissue density (kg/m3), T = T(x, y, z, t) is the temperature (°C) at location (x, y, z) and time t, Cp is the local specific heat (J/kg/°C), K is the local thermal conductivity (W/m/°C), B is the local blood perfusion coefficient (W/m3/°C), Tb is the blood temperature, Ta is the ambient temperature, Ts = Ts(x, y, z, t) is the local temperature of skin, n indicates a distance in the direction normal to the outer surface of the head, H is the convective heat transfer coefficient (W/m2/°C), A represents the metabolic heat production, SWEAT (W/m2) represents the heat flux due to evaporation, RAD (W/m2) is heat loss from radiation, and SAR (W/kg) is the RF-related heat generation in the tissue. The tissue thermal properties used in this work (such as thermal conductivity, specific heat, basal value of metabolic rate and blood perfusion coefficient) were obtained from the literature (9). These values are taken from published works (4–6, 25–27). Note that the values of A, B, SWEAT, and RAD can change with the temperature of the tissue, as will be described shortly.

A central difference scheme was used to obtain a finite-difference formulation for the bio-heat equation at locations surrounded by tissue. From equation (4) and equation (5), we have

| [4] |

where (i,j,k) is the index of the grid, Δx, Δy, and Δz are the spatial steps in x, y, and z directions, respectively, and Δt is the incremental time step.

The temperature at the object boundary is calculated as

| [5] |

for a surface facing the positive x-direction and as

| [6] |

for a surface facing the negative x-direction. Similar expressions can be obtained along the positive and negative y- and z-directions.

The convective heat-transfer coefficient H is assigned a value of 10.5W/m2/°C, consistent with other works considering the human head in air at room temperature (22). The ambient temperature is set to 24° C and the blood temperature is set to 37° C. It is reasonable to assume that the whole-body SAR is not high enough to affect the core body temperature in MRI of the human head as allowed by current regulatory guidelines (2).

Physiological Response to Temperature

It is well known that the human body has the capability to maintain its core temperature to an almost constant value around 37° C under a variety of circumstances. This is accomplished by various thermoregulatory mechanisms (28, 29). When tissues are heated excessively, regulation mechanisms will result in (among other things) vasodilation and increasing perspiration. These active thermoregulatory mechanisms, in addition to basic physical laws, make it such that the rates of metabolism, radiation, perfusion, and perspiration are all functions of temperature.

Metabolic processes are slightly accelerated when the temperature rises (5, 6). This can be expressed as

| [7] |

Where A0 is the basal metabolism rate in the tissue. T0 is the basal temperature inside the person. Here it is assumed that the metabolic rate only depends on the local tissue temperature.

For internal tissues, the blood perfusion coefficient is assumed to depend on the local tissue temperature. This can be expressed as (5–7)

| [8] |

Where B0 is the basal blood perfusion coefficient. SB is a coefficient and is set to 0.8° C−1. In this equation, the blood perfusion is not changed when the local temperature is below 39° C. It begins to increase linearly with the temperature between 39° C and 44° C in order to remove the heat from the local tissue. As the temperature increases above about 44° C, the blood perfusion coefficient reaches a maximum value.

Two inputs are used to model the regulation of the blood perfusion coefficient in the skin through vasodilatation: 1) hypothalamic temperature rise TH−TH0, and 2) average skin temperature rise ΔTS. Here TH represents hypothalamic temperature at time t and TH0 is the initial hypothalamic temperature. In this work we estimate TH as the temperature of the center of the brain, making TH0 around 37.18 °C. These two inputs are weighted differently in the feedback formula to calculate the blood perfusion coefficient for skin (3–5, 24, 25)

| [9] |

where W1 and W2 are set to 17500 W/m3/°C2 and 1100 W/m3/°C2, respectively. The exponent in the equation accounts for the local temperature effect. It doubles the blood perfusion coefficient for every 6 °C rise in local temperature above the initial temperature and halves the blood perfusion coefficient for every 6 °C drop in temperature.

Sweat regulation is modeled in a manner similar to that for skin perfusion. It is described as (5–7, 30, 31)

| [10] |

where W3 and W4 are weights for hypothalamic and skin temperature rise and set to 140 W/m2/°C and 13 W/m2/°C, respectively. P represents the basal evaporation heat loss from the skin. It is set to 4 W/m2. The exponent has the same meaning as in Eq. 9 except the denominator is 10 instead of 6.

For the calculation of radiated heat, the following equation is adopted:

| [11] |

Where δ is the Stefan-Boltzman constant equal to 5.696×10−8 W/m2/K4, ε is the dimensionless emissivity of skin, approximately equal to 1. Addition of 273.15 converts to absolute temperature.

Following validation of our numerical methods by comparison with published results (12), the computational model was used to obtain SAR and temperature distributions for a human head model in the TEM coil at 64MHz (1.5T), 200 MHz (4.7T), 300 MHz (7T), 340 MHz (8T) and 400 MHz (9.4T), respectively. All field values were normalized so that the average SAR in the head portion of the model (including chin and above) had a value of 3.0 W/kg – equal to the current FDA limit for head-average SAR (30) – before calculations of temperature increase were performed. At 300 MHz temperature calculations were also performed for head-average SAR of 6, 9, and 12 W/kg. In each case, the temperature after 30 minutes at a given SAR level was calculated, as the temperature increase at this time was determined empirically to be at least 95% of its value at two hours. To evaluate the importance of considering many of the temperature-dependant factors, Two temperature calculations were performed for each case: one considering all factors as described above, and one with SWEAT=0, RAD=0, and with A and B held constant at their basal values (9) for each tissue.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

SAR in the Human Head Model

The computed SAR distributions at most frequencies used here are in agreement with those in a previously-published work (9). Generally, the SAR distribution is frequency-dependant, as expected, and the maximum local values increase as the frequency increases. At lower frequencies (64 MHz and 200 MHz), the higher SAR is located in the peripheral regions with the SAR values decreasing towards the center of the head. At increasing frequencies, the B1 homogeneity decreases and the SAR increases. The high-SAR region moves toward the center of the head. This pattern is consistent with that seen in calculations by at least one other investigator for the head in a TEM coil (33), and with the SAR pattern in the upper portion of a sphere in a TEM-type resonator (34). A high-SAR region below the coil center is not as evident in the head model (as it is in a sphere model) because the electrical currents are not as constrained in the neck and shoulders as they are in the upper portion of the head (35).

Temperature Distribution and Elevation

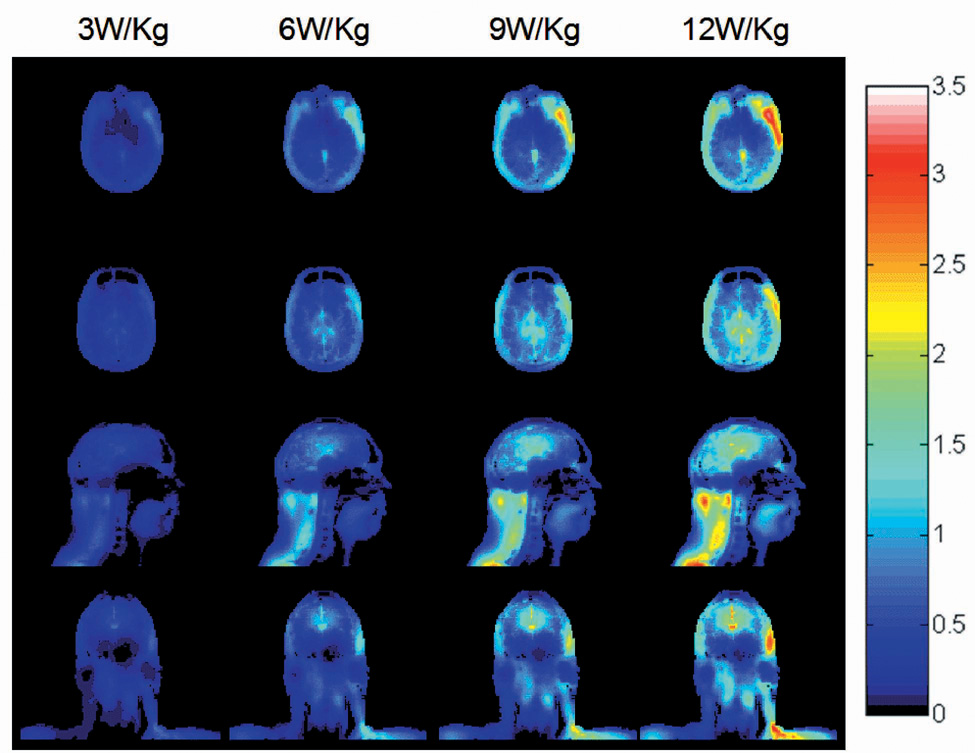

The temperature increase distributions after 30 minutes of heating without consideration of the temperature-dependant factors described here with a head-average SAR of 3.0 W/kg has been published and discussed previously (9). Briefly, it was shown that the SAR and temperature elevation inside the head are greatly influenced by the heterogeneous distribution of tissues. The spatial correlation between SAR and temperature increase is limited, due primarily to the major variation in and effect of perfusion rate between different tissues. Effects of thermal conductivity can also be seen to affect the temperature distribution in regions of relatively low SAR, such as cortical bone. Fig. 1 shows the temperature increase when the applied power is increased to achieve 3, 6, 9, and 12 W/kg head-average SAR at 300 MHz. As expected, the temperature increases become more appreciable with increasing applied power.

Fig. 1.

Calculated distribution of temperature increase (°C) for a human head in a volume coil for 30 minutes at 300 MHz with a head-average SAR of 3.0 W/kg, 6.0 W/kg, 9.0 W/kg, and 12.0 W/kg (left to right) with consideration of physiological response on an axial plane passing through the eyes (top), an axial plane passing through the center of the coil and brain (2nd row), and sagittal and coronal planes passing through the center of the coil and brain (3rd and bottom rows).

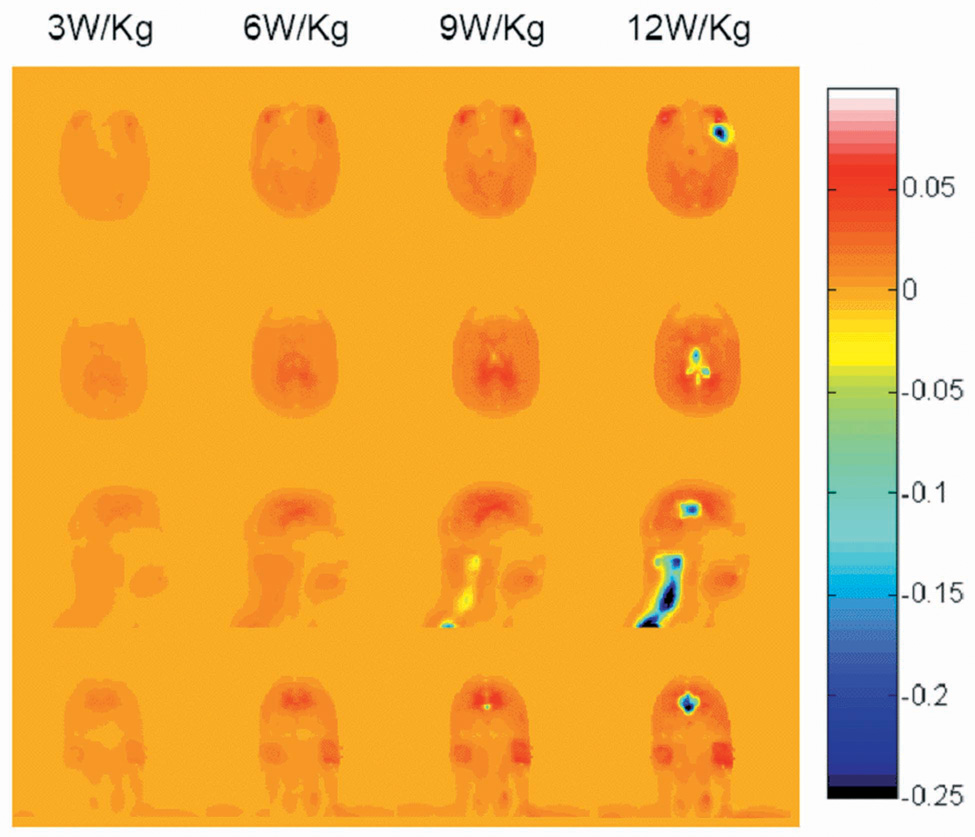

Fig. 2 shows the difference in temperature increase between when considering all factors discussed here, and when neglecting consideration of the temperature-dependant factors by setting SWEAT and RAD to zero, and holding A and B constant at their basal values (8). The temperature rise distributions were not much different between the results with and without consideration of these factors at 3W/kg head-average SAR. At this SAR level, most of the internal tissue temperatures did not exceed 39°C so the blood flow coefficient remained constant. On the other hand, the metabolic rates increased slightly with the temperature rise, resulting in temperature rises slightly greater than those seen when these factors are not considered. The temperature of some tissues when considering all factors is thus 0.01–0.02°C higher than without considering temperature-dependent factors at 3 W/kg head-average SAR. When the head average SAR is increased to 9 and 12 W/kg, the temperature at some locations exceeds 39°C, resulting in an increase in the local rate of perfusion, removing heat from the affected location at a greater rate. The temperature at these locations when considering the temperature-dependant factors are typically lower than when neglecting them. The temperature can be as much as 1.6° C less in some regions when allowing local perfusion rates to change with temperature. Obviously, the presence of thermoregulatory mechanisms can decrease the temperature elevation, especially under high power absorption conditions. However, because 3 W/kg head-average SAR is the highest currently allowed by the FDA, temperature increases as seen in Fig. 4 at greater SAR levels, and physiologic effects like those in the right three columns of Fig. 5 should never be achieved in normal practice.

Fig. 2.

Calculated difference in Temperature increase (°C) with and without consideration of physiological response (with minus without) for a human head in a volume coil for 30 minutes at 300 MHz with a head-average SAR of 3.0 W/kg, 6.0 W/kg, 9.0 W/kg and 12.0 W/kg (left to right) on an axial plane passing through the eyes (top), an axial plane passing through the center of the coil and brain (2nd row), and sagittal and coronal planes passing through the center of the coil and brain (3rd and bottom rows). Positive values generally occur where slight temperature increases cause small increases in metabolic rate, but where the temperature does not exceed 39°C enough to cause a significant thermoreglatory increase in perfusion. Negative values occur where thermoregulatory increases in perfusion have a notable effect.

In conclusion, comparison of temperature increases in the human head within a head-sized TEM coil at several frequencies driven to induce a head-average SAR of 3.0 W/kg (the current maximum allowed by the FDA) indicated that the effect of temperature-induced physiological changes is negligible (0.01–0.02 °C) in this circumstance. This study does not preclude the possibility that when more power or different types of excitation coils are used (such as for whole-body imaging (35) or very localized excitation (36)), consideration of temperature-induced physiologic changes may be more significant.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the U.S. National Institutes of Health under Grants R01 EB 000454 and R01 EB000895.

REFERENCES

- 1.International Electrotechnical Commission. International Electrotechnical Commission. International standard, medical equipment – part 2: particular requirements for the safety of magnetic resonance equipment for medical diagnosis. 2nd revision. Geneva: International Electrotechnical Commission 601-2-33; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collins CM, Liu W, Wang J, et al. Temperature and SAR calculations for a human head within volume and surface coils at 64 and 300 MHz. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2004;19:650–656. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nguyen UD, Brown JS, Chang IA, Krycia J, Mirotznik MS. Numerical evaluation of heating of human head due to magnetic resonance image. IEEE T Bio-med Eng. 2004;51:1301–1309. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2004.827559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hand JW, Ledda JL, Evans NTS. Considerations of radiofrequency induction heating for localized hyperthermia. Phys Med Biol. 1982;27:1–16. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/27/1/001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoque M, Gandhi OP. Temperature distribution in the human leg for VLF-VHF exposures at the ANSI-recommended safety levels. IEEE T Bio-med Eng. 1998;35:442–449. doi: 10.1109/10.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernardi P, Cavagnaro M, Pisa S, Piuzzi E. Specific absorption rate and temperature elevation in a subject exposed in the far-field of radio-frequency sources operating in the 10–900MHz range. IEEE T Bio-med Eng. 2003;50:295–303. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2003.808809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sturesson C, Andersson-Engels S. A mathematical model for predicting the temperature distribution in laser-induced hyperthermia: experimental evaluation and application. Phys Med Biol. 1995;40:2037–2052. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/40/12/003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pennes HH. Analysis of tissue and arterial blood temperature in resting forearm. J Appl Physiol. 1948;1:93–122. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1948.1.2.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Z, Lin JC, Mao W, Liu W, Smith MB, Collins CM. SAR and Temperature: Simulations and Comparison to Regulatory Limits for MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;26:437–441. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vaughan JT, Garwood M, Collins CM, et al. 7T vs. 4T: RF Power, Homogeneity, and Signal-to-Noise Comparison in Head Images. Magn Reson Med. 2001;46:24–30. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collins CM, Smith MB. Signal-to-Noise Ratio and Absorbed Power as Functions of Main Magnetic Field Strength and Definition of “90°” RF Pulse for the Head in the Birdcage Coil. Magn Reson Med. 2001;45:684–691. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Z. Ph.D. Dissertation. The University of Illinois; 2005. MRI RF coil model design and numerical evaluation using the finite difference time domain method. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yee KS. Numerical solution of initial boundary value problems involving Maxwell’s equations in isotropic media. IEEE T Antenn Propag. 1966;14:302–307. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ibrahim TS, Lee R, Baertlein BA, Yu Y, Robitaille P-ML. Computational analysis of the high pass birdcage resonator: finite difference time domain simulations for high-field MRI. Magn Reson Imaging. 2000;18:835–843. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(00)00161-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu W, Collins CM, Smith MB. Calculations of B1 distribution, Specific Energy Absorption Rate, and Intrinsic Signal-to-Noise Ratio for a Body-size Birdcage Coil Loaded with Different Human Subjects at 64 and 128 MHz. Appl. Magn. Reson. 2005;29:5–18. doi: 10.1007/BF03166953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alecci M, Collins CM, Smith MB, Jezzard P. Radio frequency magnetic field mapping of a 3 Tesla birdcage coil: experimental and theoretical dependence on sample properties. Magn Reson Med. 2001;46:379–385. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoult DI. The sensitivity and power deposition of the high field imaging experiment. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2000;12:46–67. doi: 10.1002/1522-2586(200007)12:1<46::aid-jmri6>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ibrahim TS, Lee R, Robitaille PML. Effect of RF coil excitation on field inhomogeneity at ultra high fields: a field optimized TEM resonator. Magn Reson Med. 2001;19:1339–1347. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(01)00404-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Collins CM, Liu W, Swift BJ, Smith MB. Combination of optimized transmit arrays and some parallel imaging reconstruction methods can yield homogeneous images at very high frequencies. Magn Reson Med. 2005;54:1327–1332. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li BK, Liu F, Crozier S. Focused eight-element transceive phased array coil for parallel magnetic resonance imaging of the chest – theoretical considerations. Magn Reson Med. 2005;53:1251–1257. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vaughan JT, DelaBarre L, Snyder C, et al. 9.4T Human MRI: Preliminary Results. Magn Reson Med. 2006;56:1274–1282. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berenger JP. Improved PML for the FDTD solution of wave-structure interaction problems. IEEE T Antenn Propag. 1997;45:466–473. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cole KS, Cole RH. Dispersion and absorption in dielectrics: alternating current characteristics. J Chem Phys. 1941;9:341–351. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gabriel C. Air Force materiel command, Brooks Air Force Base. Texas: 1996. Compilation of the dielectric properties of body tissues at RF and microwave frequencies. AL/OE-TR-1996-0037. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang J, Fujiwara O. FDTD computation of temperature rise in the human head for portable telephones. IEEE T Microw Theory. 1999;48:528–1534. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang J, Fujiwara O. Comparison and evaluation of electromagnetic absorption characteristics in realistic human head models of adult and children for 900MHz mobile telephone. IEEE T Microw Theory. 2003;51:966–971. [Google Scholar]

- 27.VanLeeuwen GMJ, Lagendijk JJW, VanLeersum BJAM, Zwamborn APM, Hornsleth SN, Kotte ANTJ. Calculation of change in brain temperatures due to exposure to a mobile phone. Phys Med Biol. 1999;44:2367–2379. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/44/10/301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wainwright P. Thermal effects of radiation from cellular telephones. Phys Med Biol. 2000;45:2363–2372. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/45/8/321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gandhi OP, Li Q, Kang G. Temperature rise for the human head for cellular telephones and for peak SARs prescribed in safety guidelines. IEEE T Microw Theory. 2001;49:1607–1609. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee DHK. Handbook of physiology-section 9: reaction to environmental agents. Bethesda: American Physiologic Society; 1977. pp. 45–69. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spiegel RJ. A review of numerical models for predicting the energy deposition and resultant thermal response of humans exposed to electromagnetic fields. IEEE T Microw Theory. 1984;32:730–746. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Center for Devices and Radiologic Health. Rockville: Food and Drug Administration; Guidance for the submission of premarket notifications for magnetic resonance diagnostic devices. 1988 http://www.fda.gov/cdrh/ode/guidance/793.html.

- 33.Angelone LM, Tulloch S, Wiggins G, Iwaki S, Makris N, Bonmassar G. New high resolution head model for accurate electromagnetic field computation; Proceedings of the 13th Annual Meeting of ISMRM; Miami. 2005. (abstract 881). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang Z, Collins CM, Smith MB. Toward understanding SAR patterns in the human head at high field (200 to 400 MHz) MRI with volume coils; Proceedings of the 14th Annual Meeting of ISMRM; Seattle. 2006. (abstract 1390). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nadobny J, Szimtenings M, Diehl D, Stetter E, Brinker G, Wust P. Evaluation of MR-Induced Hot Spots for Different Temporal SAR Modes Using a Time-Dependent Finite Difference Method With Explicit Temperature Gradient Treatment. IEEE T Bio-med Eng. 2007;54:1837–1850. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2007.893499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hand JW, Lau RW, Lagendijk JJW, Ling J, Burl M, Young IR. Electromagnetic and thermal modeling of SAR and temperature fields in tissue due to an RF decoupling coil. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1999;42:183–192. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199907)42:1<183::aid-mrm24>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]