Abstract

Over-expression of mutant p53 is a common theme in human tumors, suggesting a tumor-promoting gain of function for mutant p53. To elucidate whether and how mutant p53 acquires its gain of function, mutant p53 is inducibly knocked down in SW480 colon cancer cell line, which contains mutant p53(R273H/P309S), and MIA-PaCa-2 pancreatic cancer cell line, which contains mutant p53(R248W). We found that knockdown of mutant p53 markedly inhibits cell proliferation. In addition, knockdown of mutant p53 sensitizes tumor cells to growth suppression by various chemotherapeutic drugs. To determine whether a gene involved in cell growth and survival is regulated by mutant p53, gene expression profiling analysis was performed and showed that the expression level of Id2, a member of the inhibitor of differentiation (Id) family, was markedly increased upon knockdown of mutant p53. To confirm this, Northern blot analysis was performed and showed that the expression level of Id2 was found to be regulated by various mutant p53 in multiple cell lines. In addition, we found that the Id2 promoter is responsive to mutant but not wild-type p53 and mutant p53 binds to the Id2 promoter. Consistent with these observations, expression of endogenous Id2 was found to be inhibited by exogenous mutant p53 in p53-null HCT116 cells. Finally, we showed that knockdown of Id2 can restore the proliferative potential of tumor cells inhibited by withdrawal of mutant p53. Together, these findings suggest that one mechanism by which mutant p53 acquires its gain of function is through the inhibition of Id2 expression.

Keywords: mutant p53, gain of function, Id2, transcriptional repression, cell transformation

Introduction

Mutation of the p53 tumor-suppressor gene is one of the most frequent genetic alterations in human tumors and poses as a critical event in tumorigenesis, impacting upon tumor development, progression, and responsiveness to therapy. Approximately 50% of human cancers have p53 loss-of-function mutation (1, 2). Interestingly, both in vitro and in vivo studies have demonstrated that in addition to loss of function, mutant p53s contribute to malignant process by enhancing transformed properties of cells and resistance to anticancer therapy (3, 4). Knockin mice that carry one null allele and one mutant allele of the p53 gene (R172H or R270H) developed novel tumors compared to p53-null mice (4–6). Furthermore, mouse embryo fibroblasts from the mutant mice homozygous in R172H displayed enhanced cell proliferation, DNA synthesis, and transformation potential (3). Indeed, mutant p53s seem to be capable of activating promoters of genes that are usually not activated by the wild-type p53 protein, such as MDR1 and c-MYC (7, 8). Recent study also showed that approximate 100 genes involved in cell growth, survival, and adhesion were found to be induced by an over-expressed mutant p53 (9). Since these potential target genes were identified through over-expression of mutant p53, they may not be regulated by physiologically relevant levels of mutant p53 in tumor cells. Therefore, the mechanisms by which a mutant p53 acquires its gain of function remain largely unclear.

Like p53, the inhibitor of differentiation or DNA binding (Id) family proteins are implicated in the regulation of apoptosis and other cellular processes, such as cell fate determination, proliferation, differentiation, and invasion (10). The Id family has four members (Id1-4) and is found to be expressed in a variety of tissues. Interestingly, various Ids appear to play different roles in the same tissue and each Id may have a distinct function in different tissues (10, 11). Id2, one of the Id family proteins, has been postulated to play two opposite functions in the same or different types of cells depending on extracellular signals and microenvironments. For example, over-expression of Id2 has been shown to promote cell survival and proliferation in multiple types of tumors, including ovarian cancer, neuroblastoma, and pancreatic cancer (12–15). In contrast, Id2 is also found to have an anti-oncogenic potential. In murine mammary epithelial cells, Id2 expression is inversely correlated with the rate of proliferation and is able to suppress the proliferative and invasive potentials when reintroduced into aggressive breast cancer cells (16). Furthermore, Id2−/− mice are predisposed to intestinal tumorigenesis (17). These results suggest that Id2 has an activity in tumor suppression.

Here, to address the mechanism underlying mutant p53 gain of function, endogenous mutant p53 was inducibly knocked down in MIA-PaCa-2 and SW480 cells. We found that mutant p53 is required for cell proliferation and survival. Interestingly, we found that Id2 expression is markedly increased upon knockdown of mutant p53. In addition, we found that mutant p53 appears to regulate Id2 by directly binding to the promoter of the Id2 gene. Furthermore, knockdown of Id2 can rescue the proliferative defect induced by knockdown of mutant p53. This finding provides a novel biological insight into mutant p53 gain of function and establishes a unifying framework for understanding the relationship between mutant p53 and Id2, from which tumor patients with mutant p53 may benefit from targeted restoration of Id2 expression.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

Human colon adenocarcinoma cell line SW480, pancreatic cancer cell line MIA PaCa-2, and colon carcinoma cell line HCT116 were cultured in DMEM (Invitrogen) medium supplemented with ~10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone). HCT116(p53−/−) is a derivative of HCT116 (18). SW480-p53-KD and MIA PaCa-2-p53-KD cell lines, in which small interfering RNA (siRNA) targeting p53 is inducibly expressed under the control of the tetracycline-regulated promoter, were generated as described (19). To generate cell lines in which mutant p53 is inducibly knocked down and Id2 is stably knocked down, pBabe-H1-p53siRNA was cotransfected with pBabe-U6-Id2siRNA into SW480 cells by using Lipofectamine™ 2000 (Invitrogen), which expresses a tetracycline repressor by pcDNA6. The resulting p53 and Id2 dual-knockdown cell lines were selected with puromycin. p53 knockdown was confirmed by Western blot analysis with anti-p53 antibody whereas Id2 knockdown was confirmed by Northern blot analysis. To generate cell lines that inducibly over-express mutant p53(R175H), pcDNA4-HA-p53(R175H) was transfected into HCT116(p53−/−) cells as above, which expresses a tetracycline repressor by pcDNA6. The resulting p53(R175H) over-expression cell lines were selected with Zeocin and inducible mutant p53 over-expression was then confirmed by Western blot analysis with anti-p53 antibody.

Plasmids and scrambled shRNA

To generate a construct that expresses p53 siRNA under the control of tetracycline, one pair of oligos was cloned into pBabe-H1 at HindIII and BglII sites and the resulting construct designated as pBabe-H1-p53siRNA. pBabe-H1 is a PolIII promoter-driven plasmid with a tetracycline operator sequence inserted before the transcriptional starting site (20). The siRNA oligonucleotides cloned into pBabe-H1-p53siRNA are sense, 5'-GATCCCCGACTCCAGTGGTAATCTACTTCAAGAGA GTAGATTACCACTGGAGTCTTTTTGGAAA-3', and antisense, 5'-AGCTTTTCCAAAAAGACTCCAGTGGTAATCTACTCTCTTGAA GTAGATTACCACTGGA GTCGGG-3', with the siRNA targeting region underlined. To generate a construct that expresses Id2 siRNA, one pair of Id2 DNA oligonucleotides (sense, 5'-TCGAGGTCCGGATCCAGTATTCAGTCACTTCAAGAGAGTGACTGAATACTGGATCCTTTTTG-3', and antisense, 5'-GATCCAAAAAGGATCCAGTATTCAGTCACTCTCTTGAAGTGACTGAATACTGGATCCGGACC-3'; siRNA targeting region is underlined) was synthesized and cloned into pBabe-U6 at BamH1 and Xho1 sites. The PolIII promoter-driven plasmid pBabe-U6 was previously described (21). A scramble shRNA, 5‵-CAGUGUCUCCACGUACUAdTdT-3‵, was used as a negative control for siRNA knockdown. 20 µM scramble shRNA was transfected into parental SW480 or MIA-PaCa-2 cells with SilentFect™ lipid reagent (Bio-Rad). To generate a construct that expresses mutant p53(R175H), a 1,212-bp DNA fragment containing the entire open reading frame of mutant p53(R175H) was amplified with a forward primer, 5'-AAGCTTACCATGGGCTACCCATACGATGTTCCAGATTACGCTGAGGAGCCGCAGTCA GATCC-3', and a reverse primer, 5'-CTCGAGTCAGTCTGAGTCAGGCCCTTC-3'. The fragment was confirmed by sequencing and then cloned into pcDNA4 and the resulting plasmid designated as pcDNA4-HA-p53(R175H). The luciferase reporter under the control of the p21 promoter, pGL2-p21A, was as previously described (22). To generate luciferase reporter under the control of the Id2 promoter, a 445-bp DNA fragment containing the Id2 promoter (from nucleotide (nt) −412 to +22) was amplified using genomic DNA from SW480 cells with forward primer 5‵-CTCGAGGGCTTGGTCTGGGAACAC-3‵ and reverse primer 5‵-AAGCTTGCTGGAGCTTCCCTTCGTC-3‵. The PCR product, Id2-412, was cloned into pGEM-T-Easy vector and confirmed by DNA sequencing. After digesting with Xho I and Hind III, Id2-412 was cloned into pGL2-Basic vector and the resulting luciferase reporter designated as pGL2-Id2-412. Using pGL2-Id2-412 as a template, several deletion constructs were generated by PCR using the above reverse primer and one of the following forward primers: Id2-355 (5‵-CTCGAGAATTAAGAATGCATATTTAGGC-3‵), Id2-163 (5‵-CTCGAGCACTTACTGTACTGTACTCTAT-3‵), or Id2-89 (5‵-CTCGAGAACGCGGAAGAACCAAGC-3‵).

Microarray, Northern blot and real-time PCR analyses

Total RNA was isolated from cells using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). U133 plus 2.0 Arrays (Affymetrix), which contain oligos representing 47,000 unique human transcripts, were used for microarray assay. Northern blot analysis and preparation of p21 and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) probes were as previously described (23). The Id2 probe was prepared from an EST clone (GenBank no. BC030639). Real-time PCR was conducted using a Realplex2 system (Eppendorf). cDNA was synthesized using IscriptTM cDNA Synthesis kit (Bio-Rad). To quantify the level of Id2 mRNA, real-time PCR was done with forward primer 5'-TCAGCCTGCATCACCAGAGA-3' and reverse primer 5'-CTGCAAGGACAGGATGCTGATA-3'. GAPDH was amplified as an internal control with forward primer 5'-AGCCTCAAGATCATCAGCAATG-3' and reverse primer 5'-ATGGACTGTGGTCATGAGTCCTT-3'.

Luciferase assay

The dual luciferase assay was done in triplicate according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega). Briefly, 0.25 µg of a luciferase reporter, 0.25 µg of pcDNA3 or pcDNA3 that expresses a mutant p53 protein, and 5 ng of Renilla luciferase report (Promega) were co-transfected into p53-null H1299 cells by using ESCORT V™ transfection reagent (Sigma). The fold increase in relative luciferase activity is a product of the luciferase activity induced by a mutant p53 protein divided by that induced by an empty pcDNA3 vector.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay

Chromatin immunoprecipitation was done as previously described (19). Briefly, SW480 or MIA-PaCa-2 cells, which were uninduced (−) or induced (+) to knock down endogenous mutant p53, were cross-linked by 1% formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature. Nuclear extracts were prepared and chromatins were sonicated to generate 200-to 1,000-bp DNA fragments. Protein-DNA complexes were immunoprecipitated with various antibodies. The DNA-protein cross-links were reversed by heating at 65°C for 4 h. After phenol and chloroform extraction, DNA was purified by ethanol precipitation. To amplify the potential mutant p53 binding site from nt −163 to +22 in the promoter of the Id2 gene, PCR was done with the forward primer 5'-GCACTTACTGTACTGTACTCTAT-3' and the reverse primer 5'-GCTGGAGCTTCCCTTCGTC-3'. To amplify the p53-RE from nt −2,312 to −2,131 in the p21 promoter, PCR was done with the forward primer 5'-CAGGCTGTGGCTCTGATTGG-3' and the reverse primer 5'-TTCAGAGTAACAGGCTAAGG-3'. A region within the promoter of the GAPDH gene was amplified by the forward primer 5‵-AAAAGCGGGGAGAAAGTAGG-3‵and the reverse primer 5'-AAGAAGATGCGGCTGACTGT-3‵ to serve as a negative control for nonspecific binding.

Colony formation assay

SW480 or MIA-PaCa-2 cells (1000 per well) in a six-well plate were cultured in the absence or presence of tetracycline (1.0 µg/mL) for 72 h, and then untreated or treated with 50 nM camptothecin for 4 h, followed by one wash with DMEM to remove camptothecin. The cells were maintained in fresh medium for the next 15 to 17 days, then fixed with methanol/glacial acetic acid (7:1) and stained with 0.1% of crystal violet.

Growth curve assay

SW480 or MIA-PaCa-2 cells (10,000 per well) in a six-well plate were cultured in the absence or presence of tetracycline (1.0 µg/mL) for 48 h, and then untreated or treated with 35 nM camptothecin for 4 h, followed by one wash with DMEM to remove camptothecin. Cell culture medium was changed every 3–4 days and the number of cells was counted over a 3–12 day period.

Antibodies

Antibodies against p53 (FL-393), p21 (C-19), and Id2 (C-20) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Antibody against actin was previously described (24).

DNA Histogram Analysis

Cells were seeded at 4×105/10-cm dish, and then induced with or without tetracycline for 72 h. Both floating dead cells in the medium and live cells on the plate were collected and fixed with 10 ml of 70% ethanol for 24 h. The fixed cells were centrifuged and resuspended in 0.5 ml of phosphate-buffered saline solution containing 50 µg/mL each of RNase A and propidium iodide (Sigma). The stained cells were analyzed in a fluorescence-activated cell sorter within 4 h. The percentages of cells in the sub-G1, G1, S, and G2-M phases were determined using the CELLQuest program (BD Biosciences).

Immunofluorescence staining

SW480 cells were grown on a four-well chamber slide and treated as indicated. After washed with phosphate-buffered saline, cells were fixed with 3% of formaldehyde for 45 min, permeabilized with 0.5% of Triton X-100 for 5 min, blocked with 1% of bovine serum albumin for 1 h, and then incubated with primary Id2 antibody for 1–2 h 10 followed by incubation with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated secondary antibody (Molecular Probes). Cells were also stained with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Sigma) to visualize nuclei and then mounted with a solution containing 0.1% of purified protein derivative (Sigma) and 80% of glycerol in phosphate-buffered saline. Intracellular localization of proteins was analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy.

Statistics

All experiments were performed at least in triplicates. Numerical data were expressed as mean ± SD. Two group comparisons were analyzed by two-sided Student's t test. P values were calculated and P ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Knockdown of mutant p53 inhibits cell proliferation

Both in vitro and in vivo studies have demonstrated that in addition to loss of function, mutant p53s contribute to malignant process by acquiring a gain of function, including resistance to anticancer therapy and increased potential of invasion and metastasis (3,4). Despite these observations, the molecular basis for mutant p53 gain of function remains unclear. To test this, we analyzed the requirement of endogenous mutant p53 for cell survival in SW480, which contains mutant R273H/P309S, and in MIA-PaCa-2, which contains mutant R248W. Thus, we generated SW480 and MIA-PaCa-2 cell lines in which endogenous mutant p53 can be inducibly knocked down by siRNA under the control of the tetracycline-regulated promoter. We found that upon induction of siRNA against p53, the levels of mutant p53 protein were markedly reduced in p53-KD SW480 and MIA-PaCa-2 (Fig. 1A, left and middle panels). However, the levels of mutant p53 protein were not altered in parental SW480 cells transfected with scrambled shRNA or induction of tetracycline itself (Fig. 1A, right panel). The levels of actin protein were measured as a loading control. To examine whether mutant p53 knockdown has an effect on SW480 cell proliferation, SW480-p53-KD #11 and #12 were chosen for growth curve assays. We found that upon knockdown of mutant p53, SW480 cell proliferation was markedly inhibited (Fig. 1B, left and middle panels). These data were consistent with previous observation in SW480 cells with stable mutant p53 knockdown (4). In addition, knockdown of mutant p53 sensitized SW480 cells to treatment with camptothecin (CPT), an inhibitor of DNA topoisomerase I (Fig. 1B, left and middle panels). As a negative control, we found that tetracycline itself had no effect on parental SW480 cell proliferation regardless of treatment with CPT (Fig. 1B, right panel). In addition, long-term colony formation assay was performed and showed that cell proliferation was inhibited by mutant p53 knockdown regardless of treatment with CPT (Fig. 1C, left panel). Collectively, these results indicate that mutant p53 is required for SW480 cell survival.

Figure 1. Knockdown of mutant p53 inhibits cell proliferation.

(A) Generation of SW480 (left) and MIA-PaCa-2 (middle) cell lines in which mutant p53 can be inducibly knocked down. Western blots were prepared with extracts from SW480 and MIA-PaCa-2 cells, that were uninduced (−) or induced (+) to knock down mutant p53 for 3 days, and then probed with antibodies against p53 and actin, respectively. Right panel: scrambled shRNA and treatment with tetracycline have no effect on mutant p53 expression. Western blots were prepared with extracts from SW480 cells transfected with a scrambled shRNA, mock-treated (−), or treated with tetracycline for 3 d, and then probed with antibodies against p53 and actin, respectively. (B) Left and middle panels: knockdown of mutant p53 inhibits cell proliferation and sensitizes SW480 cells to camptothecin (CPT). Right panel: treatment with tetracycline has little if any effect on cell proliferation for parental SW480 cells regardless of CPT treatment. (C) Left panel: knockdown of mutant p53 in SW480 cells inhibits colony formation in the absence and presence of camptothecin treatment. Top right panel: knockdown of mutant p53 in SW480 cells leads to cell cycle arrest in G1. SW480 cells were uninduced or induced to knock down mutant p53 for 3 days, and then both floating dead cells in the medium and live cells on the plate were collected, and stained with propidium iodide for DNA histogram analysis. Bottom right panel: tetracycline treatment alone has no effect on the cell cycle in parental SW480 cells. (D) Knockdown of mutant p53 in MIA-PaCa-2 cells inhibits cell proliferation (left panel) and colony formation (right panel).

To uncover the underlying mechanism by which knockdown of mutant p53 is capable to inhibit SW480 cell proliferation, cell cycle was examined by DNA histogram analysis. We found that upon knockdown of mutant p53, the number of cells in G1 phase was increased from 58.19% to 64.92% (Fig. 1C, top right panel). In addition, the number of cells in S and G2/M phases was decreased from 17.48% to 14.88% and from 22.51% to 18.18%, respectively (Fig. 1C, top right panel). As a negative control, tetracycline itself had no effect on the cell cycle in parental SW480 cells (Fig. 1C, bottom right panel). These data are consistent with that obtained from growth rate analysis (Fig. 1B) and colony formation assay (Fig. 1C, left panel).

To confirm the above observations and make sure that mutant p53 gain of function is not cell type-specific, we examined whether mutant R248W is required for cell proliferation in MIA-PaCa-2 pancreatic cancer cells. For this purpose, MIA-PaCa-2-p53-KD #11 was chosen for growth curve and colony formation assays. We found that knockdown of mutant R248W also markedly inhibited MIA-PaCa-2 cell proliferation and colony formation regardless of treatment with camptothecin (Fig. 1D).

Knockdown of mutant p53 up-regulates Id2 expression

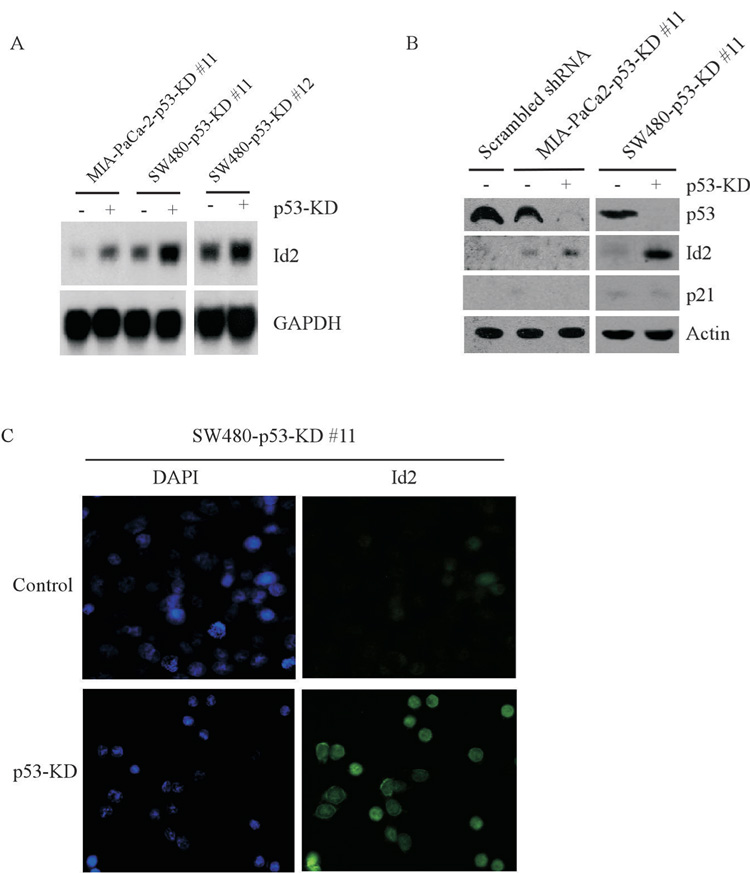

We showed above that knockdown of mutant p53 decreases cell proliferation and resistance to camptothecin in SW480 and MIA-PaCa-2 cells, both of which do not carry an allele of wild-type p53 gene. This suggests that mutant p53 has a gain of function and these tumor cells are addicted to mutant p53. Although mutant p53 in general is not capable of binding to the consensus wild-type p53 responsive element, evidence has emerged that some gain of function p53 mutants have transcriptional activity (25). Thus, to identify potential growth-promoting and/or -suppressing genes responsible for mutant p53 gain of function, microarray analysis was performed to examine the pattern of gene expression in SW480 cells uninduced or induced to knock down endogenous mutant p53. We found that the expression patterns for several genes were altered. Among these is Id2, whose expression was significantly up-regulated upon mutant p53 knockdown. To verify this, Northern blot analysis was performed and showed that the levels of Id2 mRNA were increased upon knockdown of mutant p53 in SW480 cells as well as in MIA-PaCa-2 cells (Fig. 2A). The levels of GAPDH mRNA were examined as a loading control (Fig. 2A). Next, we examined Id2 protein and showed that the level of Id2 protein was also found to be increased in MIA-PaCa-2 and SW480 cells upon knockdown of mutant p53 (Fig. 2B). However, the Id2 protein was not found to be increased in parental MIA-PaCa-2 cells transfected with scrambled shRNA (Fig. 2B). In addition, the level of p21 protein was not altered. The level of actin protein was measured as a loading control (Fig. 2B). Since Id2 is a regulator of basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factors, it has to be expressed in nucleus in order to carry out its activity. Thus, we monitored its cellular localization in SW480-p53-KD #11 cells uninduced (control) or induced (p53-KD) to knock down mutant p53. As seen in Fig. 2C, Id2 was remarkably induced and predominantly located in the nuclear upon knockdown of mutant p53 (lower right panel). In contrast, nuclear Id2 in control cells was much weaker (upper right panel).

Figure 2. Knockdown of mutant p53 up-regulates Id2 expression.

(A) Northern blots were prepared with total RNAs isolated from SW480 and MIA-PaCa-2 cells that were uninduced (−) or induced (+) to knock down mutant p53 for 3 days. The blots were probed with cDNAs derived from the Id2 and GAPDH genes, respectively. The level of GAPDH mRNA was measured as a loading control. (B) Western blots were prepared with extracts from MIA-PaCa-2 cells transfected with scrambled shRNA and from MIA-PaCa-2 and SW480 cells uninduced or induced to knock down mutant p53 for 3 days, and then probed with antibodies against p53, Id2, p21, and actin, respectively. (C) Id2 protein is induced and localized in nucleus. SW480 cells were uninduced or induced to knockdown mutant p53 for 3 days and immunofluorescent staining of SW480 cells with DAPI and anti-Id2 was performed as described in the Materials and Methods.

To further confirm that Id2 is a target gene of mutant p53, Id2 expression was examined in p53-null HCT116 cells that inducibly express tumor-derived mutant R175H under the control of tetracycline-regulated promoter. As seen in Fig. 3A, mutant R175H protein was induced over a 6-day testing period. To examine the effect of mutant p53 on Id2 expression, Northern blot analysis was performed and showed that the level of Id2 mRNA was progressively decreased upon expression of mutant R175H over the 6-day testing period (Fig. 3B, left panel). The level of GAPDH mRNA was examined as a loading control (Fig. 3B, left panel). Furthermore, real-time PCR was performed to quantify the levels of Id2 transcripts. We found that Id2 expression was significantly inhibited by over-expression of mutant p53 at day 6 (P=0.05) (Fig. 3B, right panel). Together, we concluded that Id2 can be specifically induced by knockdown of mutant p53 and is likely to be a repressed target gene of mutant p53.

Figure 3. Over-expression of mutant p53 can inhibit expression of endogenous Id2 in p53-null HCT116 cells.

(A) Western blots were prepared with extracts from p53-null HCT116 cells induced to express mutant R175H for 0, 2, 4, or 6 days and then probed with antibodies against p53 and actin, respectively. (B) Over-expression of mutant R175H inhibits endogenous Id2 expression. Left panel: Northern blots were prepared with total RNAs purified from p53-null HCT116 cells induced to express mutant p53 for 0–6 days and probed with cDNAs derived from the Id2 and GAPDH genes, respectively. Right panel: real-time PCR was performed to quantify the levels of Id2 transcripts in HCT116(p53−/−) cells inducibly expressing mutant p53 (R175H) at day 0, 4, and 6.

The Id2 promoter is responsive to mutant but not wild-type p53

Since the levels of Id2 protein and mRNA were increased upon knockdown of mutant p53, it is likely that Id2 is transcriptionally regulated by mutant p53. Thus, we searched for a potential responsive element for mutant p53 in the promoter of the Id2 gene. To this end, a 445-bp Id2 promoter fragment, which contains a GC-rich region (78% GC), was cloned into the pGL2-Basic promoterless luciferase reporter vector. The resulting vector was designated pGL2-Id2-412 (Fig. 4A, left panel). We also generated several deletion mutants of the Id2 promoter (Fig. 4A, left panel). Each of these luciferase reporters was co-transfected into H1299 cells with either a pcDNA3 control vector or a vector that expresses wild-type p53 or mutant R249S. We found that the luciferase activity for Id2-412 and Id2-355 was significantly inhibited by mutant R249S, but little if any, by wild-type p53 (Fig. 4B, left panel). Interestingly, the GC-rich region was required for mutant p53 to inhibit the Id2 promoter as the luciferase activity for Id2-163 and Id2-89 reporters was not inhibited by mutant R249S (Fig. 4B, left panel). To further demonstrate the requirement of the GC-rich region for mutant p53 inhibition of Id2, reporter Id2-355 was cotransfected into H1299 cells along with either a pcDNA3 control vector or a vector that expresses one of the three hot-spot tumor-derived p53 mutants, R175H, R249S, or R273H. We found that the GC-rich region in the Id2 promoter was responsive to mutant R175H and R273H in addition to R249S (Fig. 4B, right panel). As a control, the luciferase reporter under the control of the p21 promoter was used (Fig. 4A, right panel) and found to be inert to mutant p53 (Fig. 4B, right panel). This suggests that the GC-rich region in the Id2 promoter contains a potential mutant p53 binding site, which needs to be further characterized.

Figure 4. The Id2 promoter is responsive to mutant but not wild-type p53.

(A) Schematic presentation of the Id2 (left) and p21 (right) promoters and luciferase reporter constructs. (B) The Id2 promoter is responsive to mutant p53. Left panel: the luciferase activity under the control of various Id2 promoter fragments was measured in the presence or absence of wild-type p53 or mutant R249S. Right panel: the Id2 promoter is responsive to mutant R175H and R273H in addition to R249S. The response of the p21 promoter to these p53 mutants was measured as a control. (C) Location of a potential mutant p53 binding site in the Id2 gene (left), the p53-REs in the p21 gene (middle), and the GAPDH promoter (right) along with the location of PCR primers used for ChIP assay. (D) Left panel: mutant p53 in SW480 cells binds to the Id2 promoter. Mutant p53-DNA complexes were captured with anti-p53 antibody along with rabbit IgG as a control. The binding of mutant p53 protein to the p21 and GAPDH promoters was measured as a control. Right panel: mutant p53 in MIA-PaCa-2 cells binds to the Id2 promoter.

Next, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay was performed to determine whether mutant p53 binds to the Id2 promoter in vivo. Several primers were made in the GC-rich region, all of which cannot specifically amplify the GC-rich region due to the high GC content. Since ChIP assay was designed to amplify a protein-bound DNA fragment with a length of approximately 200-to 1,000-bp, we designed a pair of primers that can amplify a region near the GC-rich region from nt −163 to +22 (Fig. 4C, left panel). As negative controls, the interaction of mutant p53 with p53-RE1 in the p21 promoter or the GAPDH promoter was determined (Fig. 4C, middle and right panels). To test this, SW480-p53-KD #11 cells were uninduced (−) or induced (+) with tetracycline to knock down mutant p53, followed by cross-linking with formaldehyde and immunoprecipitation with anti-p53 or rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) as a negative control. We found that mutant p53 bound to the promoter of the Id2 gene but not to the p53-RE1 in the p21 gene or the GAPDH promoter (Fig. 4D, left panel). Furthermore, to rule out a possibility that the interaction of mutant p53 with the Id2 promoter in SW480 cells is cell type-specific, we examined the interaction of mutant p53 with the Id2 promoter in MIA-PaCa-2 cells. Like that in SW480 cells, mutant p53 in MIA-PaCa-2 cells was found to interact with the Id2 promoter (Fig. 4D, right panel). Taken together, these findings suggest that Id2 is likely to be a direct target of mutant p53.

Stable knockdown of Id2 restores the proliferative potential of tumor cells inhibited by withdrawal of mutant p53

If Id2 is a direct target of mutant p53, it should be able to mediate the function of mutant p53 in cell proliferation. Thus, we reasoned that targeted knockdown of Id2 would rescue the proliferative defect caused by knockdown of mutant p53. To test this, we generated SW480 cell lines in which Id2 was stably knocked down and mutant p53 can be inducibly knocked down. Two representative cell lines were chosen for further studies. As shown in Fig. 5A, mutant p53 in SW480 cells can be inducibly knocked down as the level of mutant p53 was reduces by ~80–90%. Northern blot analysis was performed to examine the level of Id2 transcript in tumor cells uninduced or induced to knock down mutant p53. Consistent with the result in Fig. 2A, in the absence of stable knockdown of Id2, the level of Id2 mRNA was increased upon knockdown of mutant p53 in SW480-p53-KD #11 cells (Fig. 5B, compare lanes 5–6). However, in Id2 knockdown cell lines, the basal and mutant p53-induced levels of Id2 were markedly reduced in both clones (#3 and #8) compared to that in SW480-p53-KD #11 cells (Fig. 5B, compare lanes1–4 with lanes 5–6). Next, transient cell growth rate was performed to measure the effect of Id2 knockdown on cell proliferation. We found that upon knockdown of Id2, mutant p53 was no longer required for cell survival as mutant p53 knockdown had little if any effect on cell proliferation (Fig. 5C). Consistent with this, long-term colony formation assay showed that Id2 knockdown restored the ability of SW480 cells to form colonies (Fig. 5D, left panel) whereas mutant p53 was required for colony formation (Fig. 1C, left panel). Furthermore, Id2 knockdown also restored the resistance of SW480 cells to treatment with camptothecin (Fig. 5D, right panel). In sum, our data indicate that suppression of Id2 by mutant p53 in tumor cells is one mechanism by which mutant p53 obtains a gain of function.

Figure 5. Stable knockdown of Id2 restores the proliferative potential of SW480 cells upon inducible knockdown of mutant p53.

(A) Identification of inducible mutant p53 knockdown cell lines. Western blots were prepared with extracts from SW480 cells uninduced (−) or induced (+) to knock down mutant p53 for 3 days, and then probed with antibodies against p53 and actin, respectively. (B) Identification of stable Id2 knockdown cell lines. Northern blots were prepared with total RNAs isolated from positive clones identified in (A) that were uninduced or induced to knock down mutant p53 and probed with cDNAs derived from the Id2 and GAPDH genes, respectively. (C) Stable knockdown of Id2 restores the proliferation potential of SW480 cells triggered by mutant p53 knockdown. The growth rate of SW480 cells with stable Id2 knockdown in the presence or absence of mutant p53 knockdown was measured over a 12-day testing period. (D) Left panel: stable knockdown of Id2 restores the colony-forming potential of SW480 cells upon knockdown of mutant p53. Colony formation assay was performed with stable Id2 knockdown SW480 cells uninduced or induced to knock down mutant p53. Right panel: stable knockdown of Id2 confers SW480 cells resistance to camptothecin treatment.

Discussion

In this study, we showed that knockdown of mutant p53, R273H/P309S in SW480 cells and R248W in MIA-PaCa-2 cells, markedly inhibits cell proliferation and survival. In particular, we showed that Id2, a negative regulator of basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factors, is transcriptionally regulated by mutant p53. In addition, we showed that stable knockdown of Id2 can restore the proliferative potential of tumor cells upon inducible p53 knockdown. These findings are consistent with an observation that Id2 promotes cell differentiation and apoptosis and suppresses tumor formation and that Id2−/− mice are prone to early onset of tumors with high penetrance (17). Since the level of Id2 protein was found to be low or undetectable in metastatic cell lines and human biopsies from metastatic carcinomas (26, 27) and loss of the Id2 gene leads to up-regulation of E-cadherin, which in turn promotes anchorage-independent cell growth, a prerequisite for metastasis (26), it suggests that mutant p53 plays a role in tumor progression and metastasis. However, it should also be noted that Id2 is able to enhance cell proliferation and promotes tumor progression (12–14, 28). This is not surprising. As a transcription factor, it is likely that Id2 may have diverse and complex biological effects depending on cell lineage, differentiation state, and microenvironment (29).

Due to the profound ability of mutant p53 to promote tumorigenesis, extensive studies have been performed to determine the mechanism by which mutant p53 obtains its gain of function, particularly its ability to function as a transcription factor to induce growth-promoting and/or inhibit growth-suppressing gene expression (25, 30). Given the fact that mutant p53 in general is unable to bind the consensus wild-type p53 responsive element, several hypotheses are postulated. For example, mutant p53, when over-expressed, was found to cooperate with NF-κB to regulate gene expression (9, 31). In addition, mutant p53 was found to interact with NF-Y to regulate expression of genes necessary for cell cycle progression and DNA synthesis (32). These studies provide an insight into how mutant p53 regulates gene expression. However, some of the potential mutant p53 target genes were identified previously via over-expressed mutant p53, such as c-Myc, cdk1, and cdc25, which have not been confirmed to be regulated by physiologically relevant levels of endogenous mutant p53 in tumor cells. Here, we found that Id2 is regulated by multiple p53 mutants. Most importantly, we showed that the expression level of Id2 was found to be regulated by endogenous mutant p53 in multiple tumor cell lines. Furthermore, we found a potential mutant p53 responsive element in the GC-rich region in the Id2 promoter. While beyond the scope for this study, additional studies are warranted to further characterize this potential mutant p53 responsive element. Considering that Id2 expression can be inhibited by mutant p53 and mutant p53-harboring tumors are aggressive (33), our results suggest that suppression of Id2 is one mechanism by which multiple p53 mutants acquire their gain of function and that tumor patients with mutant p53 might benefit from targeted restoration of Id2 expression.

References

- 1.Poeta ML, Manola J, Goldwasser MA, et al. TP53 mutations and survival in squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2552–2561. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loehberg CR, Thompson T, Kastan MB, et al. Ataxia telangiectasia-mutated and p53 are potential mediators of chloroquine-induced resistance to mammary carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2007;67:12026–12033. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lang GA, Iwakuma T, Suh YA, et al. Gain of function of a p53 hot spot mutation in a mouse model of Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Cell. 2004;119:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bossi G, Lapi E, Strano S, Rinaldo C, Blandino G, Sacchi A. Mutant p53 gain of function: reduction of tumor malignancy of human cancer cell lines through abrogation of mutant p53 expression. Oncogene. 2006;25:304–309. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olive KP, Tuveson DA, Ruhe ZC, et al. Mutant p53 gain of function in two mouse models of Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Cell. 2004;119:847–860. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heinlein C, Krepulat F, Lohler J, Speidel D, Deppert W, Tolstonog GV. Mutant p53(R270H) gain of function phenotype in a mouse model for oncogene-induced mammary carcinogenesis. Int J Cancer. 2007 doi: 10.1002/ijc.23317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frazier MW, He X, Wang J, Gu Z, Cleveland JL, Zambetti GP. Activation of c-myc gene expression by tumor-derived p53 mutants requires a discrete C-terminal domain. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3735–3743. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.3735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Atema A, Chene P. The gain of function of the p53 mutant Asp281Gly is dependent on its ability to form tetramers. Cancer Lett. 2002;185:103–109. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(02)00318-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scian MJ, Stagliano KE, Anderson MA, et al. Tumor-derived p53 mutants induce NF-kappaB2 gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:10097–10110. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.22.10097-10110.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sikder HA, Devlin MK, Dunlap S, Ryu B, Alani RM. Id proteins in cell growth and tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:525–530. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00141-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coppe JP, Smith AP, Desprez PY. Id proteins in epithelial cells. Exp Cell Res. 2003;285:131–145. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rothschild G, Zhao X, Iavarone A, Lasorella A. E Proteins and Id2 converge on p57Kip2 to regulate cell cycle in neural cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:4351–4361. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01743-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lasorella A, Iavarone A. The protein ENH is a cytoplasmic sequestration factor for Id2 in normal and tumor cells from the nervous system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:4976–4981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600168103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Newton TR, Parsons PG, Lincoln DJ, et al. Expression profiling correlates with treatment response in women with advanced serous epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:875–883. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hua H, Zhang YQ, Dabernat S, et al. BMP4 regulates pancreatic progenitor cell expansion through Id2. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:13574–13580. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600526200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Itahana Y, Singh J, Sumida T, et al. Role of Id-2 in the maintenance of a differentiated and noninvasive phenotype in breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:7098–7105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Russell RG, Lasorella A, Dettin LE, Iavarone A. Id2 drives differentiation and suppresses tumor formation in the intestinal epithelium. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7220–7225. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bunz F, Hwang PM, Torrance C, et al. Disruption of p53 in human cancer cells alters the responses to therapeutic agents. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:263–269. doi: 10.1172/JCI6863. [see comments] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yan W, Chen X. Targeted repression of bone morphogenetic protein 7, a novel target of the p53 family, triggers proliferative defect in p53-deficient breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9117–9124. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brummelkamp TR, Bernards R, Agami R. A system for stable expression of short interfering RNAs in mammalian cells. Science. 2002;296:550–553. doi: 10.1126/science.1068999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu G, Xia T, Chen X. The activation domains, the proline-rich domain, and the C-terminal basic domain in p53 are necessary for acetylation of histones on the proximal p21 promoter and interaction with p300/CREB-binding protein. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:17557–17565. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210696200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nozell S, Chen X. p21B, a variant of p21(Waf1/Cip1), is induced by the p53 family. Oncogene. 2002;21:1285–1294. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen X, Bargonetti J, Prives C. p53, through p21 (WAF1/CIP1), induces cyclin D1 synthesis. Cancer Res. 1995;55:4257–4263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu J, Zhou W, Jiang J, Chen X. Identification of a novel p53 functional domain that is necessary for mediating apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13030–13036. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.13030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peart MJ, Prives C. Mutant p53 gain of function: the NF-Y connection. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:173–174. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Onken MD, Ehlers JP, Worley LA, Makita J, Yokota Y, Harbour JW. Functional gene expression analysis uncovers phenotypic switch in aggressive uveal melanomas. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4602–4609. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stighall M, Manetopoulos C, Axelson H, Landberg G. High ID2 protein expression correlates with a favourable prognosis in patients with primary breast cancer and reduces cellular invasiveness of breast cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2005;115:403–411. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lasorella A, Rothschild G, Yokota Y, Russell RG, Iavarone A. Id2 mediates tumor initiation, proliferation, and angiogenesis in Rb mutant mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:3563–3574. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.9.3563-3574.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kowanetz M, Valcourt U, Bergstrom R, Heldin CH, Moustakas A. Id2 and Id3 define the potency of cell proliferation and differentiation responses to transforming growth factor beta and bone morphogenetic protein. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:4241–4254. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.10.4241-4254.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zambetti GP. The p53 mutation "gradient effect" and its clinical implications. J Cell Physiol. 2007;213:370–373. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weisz L, Damalas A, Liontos M, et al. Mutant p53 enhances nuclear factor kappaB activation by tumor necrosis factor alpha in cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2007 67;:2396–2401. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Di Agostino S, Strano S, Emiliozzi V, et al. Gain of function of mutant p53: the mutant p53/NF-Y protein complex reveals an aberrant transcriptional mechanism of cell cycle regulation. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:191–202. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Batista LF, Roos WP, Christmann M, Menck CF, Kaina B. Differential sensitivity of malignant glioma cells to methylating and chloroethylating anticancer drugs: p53 determines the switch by regulating xpc, ddb2, and DNA double-strand breaks. Cancer Res. 2007;67:11886–11895. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]