Abstract

The binding of nucleic acids by water soluble cobalt(II) tetrakis-N-methylpyridyl porphyrin, (TMPyP)Co and its highly electron deficient derivative, cobalt(II) tetrakis-N-methyl pyridyl-β-octabromoporphyrin, (Br8TMPyP)Co was investigated by UV-visible absorption, circular dichroism (CD), electrochemical and gel electrophoresis methods. The changes of the absorption spectra during the titration of these complexes with polynucleotides revealed a shift in the absorption maxima and a hypochromicity of the porphyrin Soret bands. The intrinsic binding constants were found to be in the range of 105 – 106 M−1. These values were higher for more electron deficient (Br8TMPyP)Co. Induced CD bands were noticed in the Soret region of the complexes due to the interaction of these complexes with different polynucleotides and an analysis of the CD spectra supported mainly external mode of binding. Electrochemical studies revealed the cleavage of polynucleotide by (TMPyP)Co and (Br8TMPyP)Co in the presence of oxygen preferentially at the A-T base pair region. Gel electrophoresis experiments further supported the cleavage of nucleic acids. The results indicate that the β-pyrrole brominated porphyrin, (Br8TMPyP)Co binds strongly and cleaves nucleic acids efficiently as compared to (TMPyP)Co. This electrolytic procedure offers a unique tool in biotechnology for cleaving double-stranded DNA with specificity at the A-T regions.

INTRODUCTION

Macrocyclic compounds which bind and cleave nucleic acids have gained importance as reagents to retrieve structural and genetic information and also to develop efficient chemical nucleases (1, 2). Several metal ions and complexes have been attached to DNA-interactive groups to produce DNA chain scission. For example, Fe(II)-EDTA covalently bound to methidium as an intercalator (3) to oligonucleotides (4, 5) and to oligopeptides/proteins (6, 7) in the presence of dioxygen and a reducing agent efficiently cleaves DNA. Nuclease activity has been observed for complexes of porphyrins of Fe(III), Mn(III), Co(III), Cu(II) and Zn(II) under chemical and photochemical conditions (2, 8–17). Hence, the porphyrin and its metal complexes have been extensively studied as models of DNA-reactive complexes (18,19). The majority of reports have concentrated on meso-tetra(4-N-methylpyridyl)porphyrin (TMPyP) and its metal complexes by spectroscopic methods. The cationic TMPyP has a high binding affinity for anionic DNA strands with association constants ranging 105–107 M−1 (20–22). The DNA binding mechanism is dependent on both the sequence of the DNA strands and the structure perturbation of the porphyrin molecules (23, 24). Additionally, the ionic strength of the solution is also known to influence the binding modes (25, 26).

The interaction of porphyrins with DNA can occur through three types of binding modes viz., intercalation, outside binding in the groove and outside binding with self-stacking along the DNA surface. DNA footprinting investigations have revealed that Mn3+, Fe3+, Zn2+ and Co2+ metal complexes of TMPyP bind to the A-T rich regions of DNA in the minor groove while Ni2+ and Cu2+ complexes of TMPyP intercalate in the G-C rich regions and bind in the A-T rich regions by outside binding mode (27, 28). These metal derivatives of TMPyP were found to cleave DNA in the presence of oxygen and either a reducing or an oxidizing agent, viz., ascorbate, superoxide, and iodosobenzene (27). Fie1 et al. (29) have reported that FeIII-TMPyP can nick DNA without any added activating agent while the studies by Praseuth et al. (13) have indicated that the photoactivation of CoIII-TMPyP (but not MnIII-TMPyP) in the presence of O2 can induce DNA cleavage. They have also demonstrated that FeIII-TMPyP can degrade DNA in few minutes without light irradiation, but that the extent of degradation increased with exposure to light. The possible mechanism of the chemically activated cleavage process includes the generation of a reduced form of oxygen produced in a redox reaction of the metal ion with oxygen.

Among the different porphyrins employed for DNA binding studies, the positively charged (TMPyP)M is the most efficient in terms of binding and cleaving DNA as compared to either of the neutral or negatively charged porphyrins. One way of improving the processes of binding and cleavage of DNA by porphyrins is by making the porphyrin ring more electrophilic while keeping the positive charges on the porphyrin macrocyle for its intrinsic affinity for DNA. This can be achieved by introducing one or more peripheral electron withdrawing substituents like halogens at the β-pyrrole positions of the TMPyP macrocycle. The first part of this study addresses this issue by employing a highly electron deficient, water soluble, β-brominated cobalt porphyrin (30–32) as DNA binding and cleaving agent (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Structure of the water soluble cobalt porphyrins utilized in the present study.

Electrochemical methods can also be used to study binding and cleavage of DNA (33). Electrochemical methods offer several advantages for probing metalloporphyrin binding and DNA cleavage and can provide a useful complement to the widely used spectroscopic methods. These advantages include: (i) Metal ion complexed macrocyclic compounds which are not amenable to spectroscopic methods, either because of weak absorption bands or because of overlap of electronic transitions with those of the DNA molecule, can potentially be studied via electrochemical techniques. (ii) Multiple oxidation states of the same species as well as mixtures of several interacting species can be observed simultaneously by electrochemical methods. (iii) Equilibrium constants (K) for the interaction of the metal complexes with DNA can be obtained from the shifts of peak potentials. (iv) Electrochemical analysis is a cleaner method which does not require addition of a reductant and hence, makes the analysis of the reaction products easier. (v) Electrochemical methods also offer a wider range of potentials to activate molecules with different binding specifications which may not be activated by chemical methods and may also be useful in following the formation and consumption of electroactive species to study reaction mechanisms. (vi) Finally, the activation process can be studied using metalloporphyrin or DNA modified electrode surfaces. The modified electrodes offer distinct advantages of requiring smaller amounts of samples and well understood surface electrochemical phenomenon. In spite of all these advantages, utilization of electrochemical techniques to the study of DNA interaction and cleavage studies has been scarce (33–36). In the present study we have also explored electrochemical methods to activate and cleave DNA by cobalt porphyrins. As shown here, the β-pyrrole brominated porphyrin exhibits better binding and cleavage of DNA under electrochemical conditions.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Chemicals and reagents

(TMPyP)Co as tetrachloride salt was purchased from Mid-Century Chemicals Co. Illinois, and used as received while (Br8TMPyP)Co as tetrachloride salt was prepared by following the reported procedure (30). Calf thymus DNA (CT-DNA), ds poly d(G.C) and ds poly d(A.T), sodium dihydrogen phosphate, sodium phosphate dibasic and cacodylic acid were obtained from Sigma Aldrich while Phi X 174 DNA was purchased from Promega. Trisbase, boric acid and EDTA were received from Fischer scientific chemicals Ltd. USA.

Stock solution of CT-DNA was prepared by sonication at 0–5 0C. Concentration of DNA was determined by UV absorbance at 260 nm (ε260 = 6.6 × 103 M−1cm−1). Stock solutions of double stranded (ds) poly d(G.C) and ds poly d(A.T) were prepared in different buffers as mentioned in the text. A 0.05 M phosphate buffer of pH 10.5 and cacodylic buffer of pH 7.0 were used in the study. Tris borate-EDTA buffer of pH 8.3 was used as a loading buffer in electrophoresis experiment. Stock solutions of 1 µM each of (TMPyP)Co and (Br8TMPyP)Co were prepared separately in deionized water. High purity nitrogen was used for deaeration.

Instrumentation

Electrochemical measurements were performed on a PAR electrochemical Instrument model PARSTAT 2273 (EG & G, USA). The standard cell consisted of three electrodes that include the working electrode (Platinum or glassy carbon electrode), the reference electrode (Ag/AgCl/3 M KCl) and an auxiliary electrode (Pt wire). In order to obtain reproducible results, the electrodes were cleaned with soft emery paper (600 A), polished with 0.05 µm alumina, then sonicated (ultrasound bath) for 3 min and rinsed with deionized water before making a measurement.

The CD measurements were made on a 70 JASCO-J-810 spectropolarimeter (Tokyo, Japan) using a 0.1 cm cell at 0.2 nm intervals, with 5 scans averaged for each CD spectrum.

The absorption spectra were recorded on a double beam UV-visible spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-1650 PC).. A quartz cell of 1.00 cm was used for measurements.

Gel electrophoresis experiments were carried out on a mini sub cell GT from Bio-Rad and Bio-Rad Power PAC 1000 as power source.

Hypochromicity and evaluation of binding constant

The hypochromicity in the Soret band of the cationic porphyrins caused by their interaction with CT-DNA/ds poly dpoly d(A.T)/ ds poly dpoly d(G.C) was determined by performing absorption titration experiments wherein the concentration of the metal porphyrin complex is kept constant and the concentration of nucleic acid/poly nucleotide was varied in cacodylic buffer of pH 7. Absorbance values were recorded at room temperature after each successive addition of CT-DNA/ ds poly dpoly d(A.T)/ds poly dpoly d(G.C) [0.25–0.3 µl CT-DNA or 1 µl ds poly dpoly d(A.T)/ ds poly dpoly d(G.C)] to (TMPyP)Co (0.005 µM for ds poly dpoly d(A.T) and ds poly dpoly d(G.C) or 0.05 µM for CT-DNA) or (Br8TMPyP)Co (0.083 µM for ds poly dpoly d(A.T) and ds poly dpoly d(G.C) or 0.01 µM for CT-DNA) and equilibration (ca. 0.5 min). Buffer blanks were used to compensate for the dilution effect. The percentage of hypochromicity was determined from equation (1).

| (1) |

where If and Ib represent the optical density of the free porphyrin complex and the mixture of free porphyrin complex and bound to DNA/ds poly dpoly d(A.T)/ds poly dpoly d(G.C), respectively. The absorbance data were fit to Benesi-Hildebrand plot (37) of I/ΔI versus 1/C to evaluate the binding constant of (TMPyP)Co/(Br8TMPyP)Co-DNA/ ds poly dpoly d(A.T)/ ds poly dpoly d(G.C).

Circular dichroism measurements

CD spectra of CT-DNA/ ds poly dpoly d(A.T)/ ds poly dpoly d(G.C) were recorded in the presence of increasing amounts of (TMPyP)Co and (Br8TMPyP)Co complexes (0.005–0.03 µM), separately in cacodylic buffer of pH 7.

Modification of glassy carbon electrode

Stock solutions of CT-DNA, ds poly dpoly d(G.C) and ds poly dpoly d(A.T) were prepared in Tris-HCl buffer of pH 7.3 containing 0.1 M NaCl. These solutions were used for making the CT-DNA and ds poly dpoly d(A.T)/ds poly dpoly d(G.C) modified electrodes. To prepare a drop coated electrode, 5 µl of CT-DNA solution was transferred to cover the glassy carbon electrode’s surface, and then warm air (about 50° C) was blown from a distance of 10 cm to dry the electrode’s surface to make a film. Later, (TMPyP)Co/(Br8TMPyP)Co was transferred on the DNA film modified electrode and dried by warm air. Electrochemical deposition was performed by holding the potential at a suitable reduction potential for the metalloporphyrin film. Stable GC/ DNA/metalloporphyrin films can also be prepared by keeping the potential of the DNA-modified electrode at −40 mV (versus Ag/AgCl) in a metalloporphyrin aqueous solution as is done in consecutive cyclic voltammetry (38).

Solutions were thoroughly deoxygenated, unless otherwise indicated, by bubbling with nitrogen that had been previously saturated with water. During the data acquisition, a nitrogen atmosphere was maintained over the solution in the cell.

Bulk electrolysis

In order to conserve the nucleic acid and ds poly d(A.T)/ ds poly d(G.C), it becomes essential to carryout the bulk electrolysis experiments on a small scale. A home made microcell assembly consisting of an outer working electrode compartment and an inner compartment with a porous Vycor plug containing the reference and counter electrodes was used to electrolyze different amounts of the metalloporphyrins with Phi X 174 DNA, ds poly d(G.C) and ds poly d(A.T) concentration of 0.6 µg. The reaction mixture was placed in the working electrode compartment. The other compartment consisted of supporting electrolyte, phosphate buffer of pH 10.5. The working solution compartment volume was maintained at 120 µl. The electrolysis was carried out in the dark for 10 h at −450 mV in the presence of (TMPyP)Co or (Br8TMPyP)Co. During electrolysis, O2 was bubbled into the solution. The working, counter and reference electrodes used were Pt foil, Pt wire and Ag/AgCl, respectively.

Gel Electrophoresis

A sample (120 µl) of either Phi X 174 DNA or ds poly d(G.C) or ds poly d(A.T) and (TMPyP)Co or (Br8TMPyP)Co was electrolyzed for 10 h in the presence of oxygen. From this, a fraction of the reaction mixture (20 µl) containing Phi X 174 DNA (0.1 µg), (TMPyP)Co (8.3 µl, 1 µM) and phosphate buffer of pH 10.5 (10 µl) was added followed by 2 µl of the loading dye (bromophenol blue dye and sucrose) into the wells of a 1 % horizontal agarose gel containing 1 µg/ml ethidium bromide. The gel electrophoresis was carried out at 4 V/cm for 1 h in 89 mM Tris-base, 89 mM boric acid, 2 mM EDTA buffer of pH 8.3. After electrophoresis, the DNA bands were visualized and photographed under ultraviolet light.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Absorption studies

Absorption spectroscopy is one of the convenient tools for examining the interaction between ligands and nucleic acids. The different modes of interaction of a metal complex with DNA can be studied not only by this technique but also by circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy. Binding of (TMPyP)Co or (Br8TMPyP)Co to native and synthetic polynucleotides induces changes of the absorption spectrum in the Soret band. The extent of the shift and hypochromism depends on the nature of the polynucleotide, porphyrin and the binding mode. Generally, the change is large for intercalation and small for groove binding or stacking mode. The absorption spectra of both (TMPyP)Co or (Br8TMPyP)Co were recorded separately in the presence of increasing amounts of nucleic acid/ds poly d(G.C)/ds poly d(A.T) in cacodylic buffer of pH 7. The representative absorption spectra of (TMPyP)Co-ds poly d(A.T) and (Br8TMPyP)Co-ds poly d(A.T) are shown in Figure 1.a and 1.b, respectively. Upon successive addition of ds poly d(A.T), ds poly d(G.C) and CT-DNA, the Soret bands of (TMPyP)Co were red shifted from 433.9 to 440.3 nm, 434 to 436 nm and 433.5 to 437.4 nm, respectively, while in the case of (Br8TMPyP)Co, blue shift in Soret band was observed from 468.5 to 462.7 nm, 467.8 to 464.7 nm and 469.8 to 468.2 for ds poly d(A.T), ds poly d(G.C) and CT-DNA, respectively. (TMPyP)Co exhibited 9.25–13.58%, 3.71–24.18 % and 2.94–46.93 % while (Br8TMPyP)Co showed 3.43–6.49%, 3.50–35.0 % and 4.05–36.85% hypochromism with CT-DNA, ds poly d(A.T), ds poly d(G.C), respectively. These results reveal that both porphyrin complexes interact with nucleic acid, ds poly d(G.C) and ds poly d(A.T).

Figure 1.

UV-visible spectrum of (a) (TMPyP)Co and (b) (Br8TMPyP)Co on increasing addition of ds poly d(A.T) (0.004 µM each addition). The Figure inset shows Benesi-Hildebrand plot of I/ΔI versus 1/C constructed for the determination of binding constant.

In order to compare quantitatively the binding strength of the complexes, the intrinsic binding constants, Kb of (TMPyP)Co and (Br8TMPyP)Co with ds poly d(A.T), ds poly d(G.C) and CT-DNA, respectively were determined from their spectral changes monitored in the Soret region. The intrinsic binding constants as evaluated from Benesi Hildebrand plot (37) (see Figure 1 inset) were found to be 1.5 × 105 M−1, 7.0 ×105 M−1 and 8.0 × 105 for (TMPyP)Co and 8.0 × 105 M−1, 9.0 × 105 M1 and 7.0 × 106 M−1 for (Br8TMPyP)Co with ds poly d(A.T), ds poly d(G.C) and CT-DNA, respectively. These results indicate that the (Br8TMPyP)Co binds strongly to ds poly d(A.T), ds poly d(G.C) and CT-DNA as compared to (TMPyP)Co.

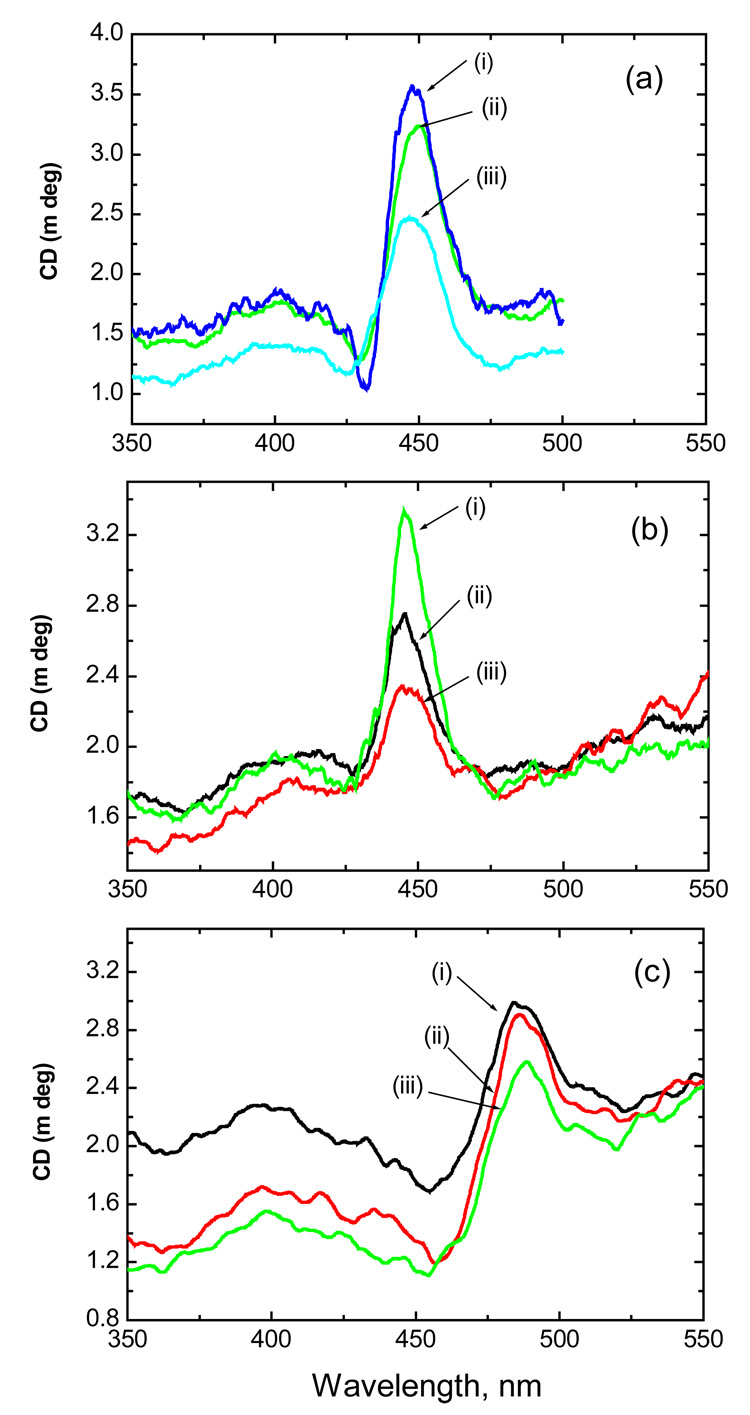

Circular Dichroism Studies

Circular dichroism is a powerful technique for distinguishing the three main DNA-binding modes, namely intercalation (negative CD), outside groove binding (positive CD), and outside stacking (bisignate CD) (39, 40). The metalloporphyrin derivatives considered here do not display CD spectra in the absence of nucleic acid/ds poly d(G.C)/ds poly d(A.T), but CD spectra are induced in the Soret region, when they are bound to nucleic acids/ds poly d(G.C)/ds poly d(A.T) due to the interaction between the transition moments of the achiral porphyrin and chirally arranged DNA base transitions. Representative induced CD spectra in the visible region for unbrominated and brominated cobalt porphyrins recorded in the presence of CT-DNA and ds poly d(A-T) are shown in Figures 2a–2c. The mole ratio of porphyrin to DNA base pairs, R value was varied from 6.3 to 19. (TMPyP)Co examined in the present study displayed two positive induced CD signals in the Soret region at 402 and 447nm in presence of CT-DNA (Figure 2.a); at 400 and 444 nm in presence of ds poly d(A.T) DNA (Figure 2.b) and at 397 and 485 nm for ds poly d(G.C). The CD spectra of (Br8TMPyP)Co exhibited positive bands at 398 and 487 nm for CT-DNA; at 398 and 485 nm for ds poly d(A.T) (Figure 2.c) and at 397 and 483 nm for ds poly d(G.C). These results reveal that the interaction is not through intercalation (41) but through external binding mode at these investigated R values. It is important to note that although the macrocycle of the brominated cobalt porphyrin is severely distorted (up to 2 Å as estimated from computational calculations), it effectively interacts with CT-DNA/ ds poly d(A.T).

Figure 2.

Circular dichroism spectrum of (a) CT-DNA interacting with (TMPyP)Co (i–iii represents 0.01µM each addition) (b) poly [d(A-T)2] interacting with (TMPyP)Co (i–iii represents 0.01µM each addition), and (c) poly [d(A-T)2] interacting with (Br8TMPyP)Co (i–iii represents 0.01µM each addition). All the spectra were recorded in cacodylic acid buffer of pH 7.0.

The CD spectrum of CT-DNA (not shown) recorded in the absence of the porphyrin complex shows a positive band at 275 nm due to base stacking and a negative band at 245 nm due to helicity and is characteristic of DNA in the right-handed B form (42). The conformational changes observed in the UV region may be due to the effect of nucleobase or porphyrin (since porphyrin has weak absorption in the same region where nucleobase moiety absorbs). In the presence of (TMPyP)Co or (Br8TMPyP)Co, the negative band at 245 nm decreases while the positive band at 275 nm disappears and a negative peak appears at the same wavelength. These observations also indicate that the CT-DNA interacts with both (TMPyP)Co and (Br8TMPyP)Co through an external binding mode. Both porphyrin complexes exhibited a strong negative band around 280 nm region when bound to ds poly d(A.T) and a positive peak around 275 nm when bound to ds poly d(G.C). These observations are in agreement with the reported literature (43).

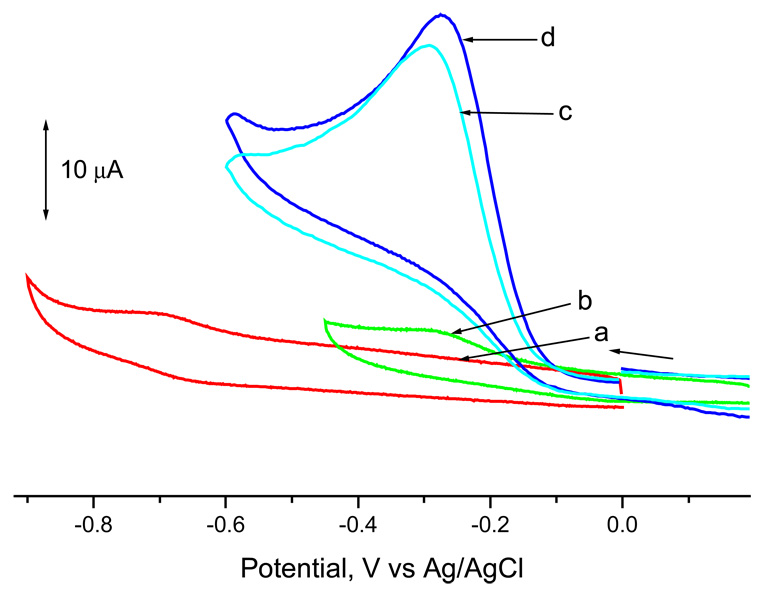

Electrochemistry of (TMPyP)Co and (Br8TMPyP)Co

Both cyclic voltammetry (CV) and differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) were employed to probe the binding of metalloporphyrins to DNA in solution. The selection of CV and DPV techniques is based on their different time scales (44). The time scale, τ for typical CV experiment is around 250 ms (τ ~ RT/νF, R = molar gas constant, F = faraday constant, ν = scan rate and T = temperature) while for a DPV under the same conditions this value is 17 ms. As a result, the reversibility of heterogeneous electron transfer kinetics will be different for these two techniques. DPV data were used to obtain quantitative information about the interaction of these metalloporphyrins with CT-DNA and Phi X 174 DNA.

Figures 3.a–3.d show the cyclic voltammograms of (TMPyP)Co and (Br8TMPyP)Co in the absence and presence of oxygen. The electroreduction behavior of these porphyrins is reversible to quasireversible. The potentials corresponding to the reduction processes are located at E1/2 = − 0.67 and Epc = − 0.29 V vs Ag/AgCl, respectively, for (TMPyP)Co and (Br8TMPyP)Co under the given solution conditions of pH 10.5. It is evident that the redox potentials for the brominated porphyrin are shifted positively as compared to that of the corresponding unbrominated derivative. Bothmetalloporphyrins reduce dioxygen as shown by the voltammograms in Figures 3.c and 3.d. In a previous study, we have shown the occurrence of a two-electron reduction leading to the formation of H2O2 by these porphyrins (30). The peak potentials for the catalytic reduction are located at Epc = − 0.29 and − 0.27 V vs. Ag/AgCl for (TMPyP)Co and (Br8TMPyP)Co, respectively, while that of free O2 is observed at − 0.56 V. That is, the dioxygen reduction was easier by 20 mV by the more electron deficient β-pyrrole brominated cobalt porphyrin. It may be mentioned here that a similar electrocatalytic reduction of dioxygen was observed when electrodes modified by drop coating the cobalt porphyrins were used.

Figure 3.

Cyclic voltammograms of (a) (TMPyP)Co, (b) (Br8TMPyP) in nitrogen atmosphere, and (c) (TMPyP)Co, (d) (Br8TMPyP)Co in oxygen atmosphere. Solution composition: phosphate buffer of pH 10.5. San rate = 50 mVs−1.

As shown in Figure 4, DNA binding to metalloporphyrins yield diminished currents as a result of reduced diffusion of the porphyrin-DNA complex. This change is also accompanied by a shift in the redox potential values as a result of complex formation. The magnitude of this potential shift is dependent upon the oxidation state of the metal ion. That is, a cathodic shift of ~0.1 V is observed for Co3+ (oxidized species) binding to DNA while this shift is < 20 mV for Co+ (reduced species) binding to DNA in Figure 4.a–4.b. These results indicate a higher binding power of porphyrins having metal ions in higher oxidation state, a novel property that could be probed easily by electrochemical techniques.

Figure 4.

Differential pulse voltammograms for (a) the first oxidation and (b) the first reduction of (TMPyP)Co in the absence (curve i) and presence of ~10 eq. of calf thymus DNA (curve ii) at pH 7.4 buffer solution. Ionic strength = 0.1 M. Scan rate = 2 mV/s, pulse width = 0.50 s, and pulse height = 0.025 V.

DNA cleavage by electrochemical method

The DNA cleavage studies were performed by drop coating the electrode surfaces with the catalyst and DNA in order to conserve the catalyst and the substrate. In a typical cleavage experiment, a modified electrode of GC/ DNA/(Br8TMPyP)Co or (TMPyP)Co was immersed in phosphate buffer of pH 10.5 and voltammograms were recorded under nitrogen atmosphere. Then the modified electrode was taken out of the solution. A stream of oxygen was bubbled through the phosphate buffer for 2 min. The electrode was then dipped into the aerated buffer and voltammograms were recorded.

Figures 5.a and 5.b show representative CV and DPVs for (TMPyP)Co in the presence of CT-DNA in oxygen saturated solution, and (Br8TMPyP)Co in the presence of ds poly d(A.T) in oxygen saturated solution, respectively. The potential of the cyclic voltammogram was scanned, first, in the negative direction, and after crossing the potential corresponding to the catalytic reduction of dioxygen the scan direction was changed into the positive direction. That is, oxygen was in-situ reduced and its effect on the DNA cleavage was simultaneously monitored by following oxidative waves corresponding to the cleavage products. Two oxidative cleavages were noticed at the potentials of + 0.72 and + 1.01 V for CT-DNA (Fig. 5.a), at + 0.73 and + 1.02 V for Phi X 174 DNA and at + 0.69 and + 1.09 V for ds poly d(A.T) in presence of (TMPyP)Co, and at + 0.67 and + 1.02 V for CT-DNA, at + 0.65 and + 0.99 V for Phi X 174 DNA and at + 0.71 and + 0.99 V for ds poly d(A.T) (Fig. 5.b) with (Br8TMPyP)Co. Almost similar behavior was observed for rest of nucleic acids and ds poly d(A.T)/cobalt porphyrins. In all of these experiments currents of the second oxidation wave were found to be much larger than the first one suggesting occurrence of other oxidation processes at this potential. In order to identify the nucleobase pair of nucleic acid at which the cleavage has occurred, in a control experiment we recorded the voltammograms by external addition of monomer nucleobases (adenine, guanine, thymine and cytosine) into the electrochemical cell used above. Addition of adenine increased the intensity of the peak at ~ 0.67 while thymine increased the intensity of the peak at ~1.0 V suggesting that the DNA cleavage takes place at adenine and thymine base pairs. It may be mentioned here that when the potential was scanned initially in the positive direction no wave ~ 0.67 V corresponding to the oxidation of adenine was observed. However, the wave at ~1.0 V was observed with diminished currents. These results suggest that the wave at ~1.0 V might involve currents from re-oxidation of the peroxide generated during the catalytic reduction of oxygen and/or direct oxidation of the nucleic acid and polynucleotide at this potential. Further, it was noticed that the ds poly d(G.C) did not show any cleavage with (TMPyP)Co and (Br8TMPyP)Co. That is, no peaks corresponding to guanine or cytosine were observed indicating cleavage preference over ds poly d(A.T) by the cobalt porphyrins. These results were further confirmed by gel electrophoresis experiments of electrolyzed ds poly d(A.T) and ds poly d(G.C) with (TMPyP)Co and (Br8TMPyP)Co, discussed below.

Figure 5.

Cyclic (blue lines) and differential pulse (red lines) voltammograms of (a) (TMPyP)Co in the presence of CT-DNA in oxygen saturated solution, (b) (Br8TMPyP)Co in the presence of ds poly d(A.T) in oxygen saturated solution. Conditions: phosphate buffer (pH 10.5), scan rate = 50 and 5 mVs−1 for CV and DPV, respectively.

In order to understand the role of the electro-active cobalt in the DNA cleavage process, control experiments were performed utilizing free-base porphyrin, (TMPyP)H2 and zinc porphyrin, (TMPyP)Zn (zinc is electro-inactive metal) in the presence of oxygen and DNA. Under these experimental conditions, no peak corresponding to DNA oxidation products around +0.7 V was observed suggesting absence of DNA cleavage by these porphyrins (see SI for figures). Similarly, the electrolysis products of the above reaction mixture revealed no DNA fragments by the agorose gel electrophoresis indicating absence of DNA cleavage process.

Electrophoresis study - Cleavage of DNAs and polynucleotides

Samples containing Phi X 174 DNA and (TMPyP)Co in aphosphate buffer of pH 10.5 were submitted to voltammetric electrolysis at −0.45 V for 10 h with continuous oxygen purging. Figure 6 shows the gel electrophoresis of Phi X 174 DNA with (TMPyP)Co. Bromophenol blue dye (2 µl) was injected at lanes 1–4 and non-electrolyzed DNA was injected at lane 1. At lanes 3 and 4, 0.1 and 0.125 µg of electrolyzed reaction mixture of DNA and (TMPyP)Co were injected, respectively. After gel electrophoresis experiments, Though no separations of Phi X 174 DNA were observed in lane 1, there was prominent band representing a - supercoiled form of DNA at position (a). A dark band in lane 2 is caused by the run dye -. In lanes 3 and 4, form I of DNA (supercoiled form) of Phi X 174 DNA is observed at position (a) gradually disappeared and form II (relaxed circular form) at position (b) was observed. It was only when the number of single-strand breaks become-sufficient that the band corresponding to form III (linear form) was seen on electrophoresis gels. Thus, the double-strand breaks in DNA responsible for these linear forms of DNA have to be considered as resulting from coincidence of two random single-strand breaks. More predominant bands were observed with larger amount of electrolyzed reaction mixture (lane 3).

Figure 6.

Electrophoresis results showing cleavage of Phi X 175 DNA by electrolysis carried out in the presence of (TMPyP)Co and oxygen. Lanes: 1- Non-electrolyzed Phi X 174 DNA, 0.1 µg; 2- Bromophenol blue dye (2 µl); 3- Electrolyzed plasmid Phi X 174 DNA, 0.1 µg and 4- Electrolyzed Phi X 174 DNA, 0.125 µg; Conditions: Agarose gel: 1.0%, ethidum bromide: 10 µl (1 µg/ml), potential applied = 40 V, loading dye: 2 µl, electrophoresis time: 1 h. Bulk electrolysis conditions: Phi X 174 DNA with (TMPyP)Co and 0.05 M phosphate buffer of pH 10.5 +10 µl of 10% of SDS at − 0.45 V with continuous oxygen purging for 10 h.

Figures 7a and 7b show the cleavage of ds poly d(A.T) by (TMPyP)Co and (Br8TMPyP)Co, respectively. In Figure 7a, the electrolysis was carried out at the potential of −0.45 V for 30 and 45 min separately with continuous oxygen purging. A broad band was observed with the reaction mixture which was electrolyzed for 30 min indicating incomplete cleavage of ds poly d(A.T) by (TMPyP)Co. However, complete cleavage of ds poly d(A.T) was noticed with the reaction mixture electrolyzed for 45 min. Hence, the electrolysis was carried out for 45 min in all subsequent experiments. Further, the band intensity varied with the concentration of ds poly d(A.T) in lanes. Similar behavior was observed with ds poly d(A.T) in the presence of (Br8TMPyP)Co as shown in Figure 7b. A comparison between the cleaving behavior of (TMPyP)Co and (Br8TMPyP)Co in Figure 7b (lanes 3 and 4) clearly shows that (Br8TMPyP)Co is as good if not better than (TMPyP)Co. Similar experiments carried out for ds poly d(G.C) in the presence of either (TMPyP)Co or (Br8TMPyP)Co revealed no cleavage products corresponding to guanine or cytosine. This confirms the earlier electrochemical claim that the cleavage of Phi X 174 DNA and CT-DNA occur at A.T bases but not at G.C bases.

Figure 7.

(a) Electrophoresis results showing cleavage of ds poly d(A.T) by electrolysis carried out in the presence of (TMPyP)Co and oxygen. Lanes: 1- Non-electrolyzed ds poly d(A.T), 0.05 µg; 2- ds poly d(A.T), 0.075 µg, electrolyzed for 30 min; 3- ds poly d(A.T), 0.075 µg, Electrolyzed for 45 min, and 4- ds poly d(A.T) [0.05 µg] electrolyzed for 45 min. Conditions: Agarose gel: 1.0 %, ethidum bromide: 10 µl. (1 µg/ml), potential applied = 40 V, loading dye: 1 µl, electrophoresis time: 1 h. (b) Electrophoresis results showing cleavage of ds poly d(A.T) by electrolysis carried out in the presence of (Br8TMPyP)Co and oxygen. Lanes: 1- Non-electrolyzed ds poly d(A.T), 0.05 µg; 2- Loading dye, 2 µL, 3- Electrolyzed [ds poly d(A.T), 0.075 µg + (TMPyP)Co, 1 µM + phosphate buffer(pH 10.5)], 4- Electrolyzed [ds poly d(A.T), 0.075 µg + (Br8TMPyP)Co, 1 µM + phosphate buffer (pH 10.5)]. Electrolysis time = 45 min. Conditions: Agarose gel: 1.0 %, ethidum bromide: 10 µl. (1 µg/ml), potential applied = 40 V, loading dye: 1 µl, electrophoresis time: 1 h.

A possible mechanism for binding and cleavage of dsDNA (natural or synthetic) - -by the studied cobalt porphyrins is shown in Scheme 2. The initial step involves electroreduction of cobalt porphyrin to a reduced state. Based on the electrochemical data in Figure 3, one could assign CoII as the species responsible for dioxygen binding in the case of (TMPyP)Co while a CoI species is responsible for dioxygen binding in the case of (Br8TMPyP)Co. The reduced cobalt porphyrin binds dioxygen and catalytically reduces to hydrogen peroxide. The hydrogen peroxide thus generated reacts with the reduced cobalt porphyrins generating hydroxyl radicals which in turn cleave the DNA/ds poly d(A.T) at the A.T region. Although the present investigation could not fully explain the observed A.T selectivity, previous studies have also confirmed such behavior of metalloporphyrin in the presence of chemical reducing agents (27, 28). Currently, we are involved in covalently linking intercalators such as acridine to the β-brominated metalloporphyrins to probe the binding and cleavage studies by electrochemical techniques.

Scheme 2.

Proposed mechanism of electrochemically activated cobalt porphyrindioxygen induced DNA cleavage.

CONCLUSIONS

Cobalt(II) tetrakis-N-methylpyridyl porphyrin, and its β-pyrrole brominated derivative have been successfully utilized for nucleic acid/ds poly d(G.C)/ds poly d(A.T) binding studies. UV-Vis and CD studies have been carried out to determine the nature of binding between metalloporphyrin complexes and nucleic acid/ds poly d(G.C)/ ds poly d(A.T). The shift in the wavelength maxima, percent hypochromicity and the binding constant values indicate that the behavior of both cobalt porphyrins with nucleic acid/ds poly d(G.C)/ds poly d(A.T) is same, however, the more electron deficient brominated porphyrin binds strongly when compared to unbrominated porphyrin. Circular dichroism studies revealed that the mode of binding is the same for both porphyrins and it is through an external binding mode. Electrochemical studies revealed that the cobalt porphyrins bind and catalytically reduce dioxygen to hydrogen peroxide and indicated that they complex with the employed nucleic acid, ds poly d(G.C) and ds poly d(A.T) as evidenced by the shift in the potentials and reduced peak currents. In the presence of dioxygen, the cobalt porphyrins electrochemically cleave nucleic acid and ds poly d(A.T). Gel electrophoresis experiments were carried out to investigate the cleavage of DNA base pairs, ds poly d(G.C) and ds poly d(A.T). The electrochemical studies coupled with the gel electrophoresis results unanimously suggest that the cleavage occurs at the A.T base pairs and not at the G.C base pairs. The procedure offers a unique tool to cleave dsDNA as A-T specific bonds in molecular biology.

Supplementary Material

Cyclic voltammograms of calf thymus DNA in the presence of free-base and zinc porphyrins. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Support from the National Institutes of Health, the Petroleum Research Fund administered by the American Chemical Society, and the West Memorial Foundation is gratefully acknowledged.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Sigman DS. Chemical Nucleases. Biochem. 1990;29:9097–9105. doi: 10.1021/bi00491a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sashikumar M, Munson BR, Pandey RK. DNA interaction and photocleavage properties of porphyrins containing cationic substituents at the peripheral position. Bioconjugate Chem. 1999;10:94–102. doi: 10.1021/bc9800872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hertzberg RP, Dervan PB. Cleavage of DNA with methidiumpropyl-EDTA-iron (II): reaction conditions and product analyses. Biochem. 1984;23:3934–3945. doi: 10.1021/bi00312a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chu BCF, Orgel LE. Nonenzymic sequence-specific cleavage of single-stranded DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S A. 1985;82:963–967. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.4.963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moser HE, Dervan PB. Sequence-specific cleavage of double helical DNA by triple helix formation. Science. 1987;238:645–650. doi: 10.1126/science.3118463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Youngquist RS, Dervan PB. Sequence-specific recognition of B-DNA by oligo(N-Methylpyrrolecarboxamides) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1985;82:2565–2569. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.9.2565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sluka JP, Horvath SJ, Bruist MF, Simon MI, Dervan PB. Synthesis of a sequence-specific DNA-cleaving peptide. Science. 1987;238:1129–1132. doi: 10.1126/science.3120311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trung LD, Perrouault L, Nguyen TT, Helene C. Sequence-targeted chemical modifications of nucleic acids by complementary oligonucleotides covalently linked to porphyrins. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:8643–8659. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.21.8643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ford KG, Neidle S. Perturbations in DNA structure upon interaction with porphyrins revealed by chemical probes, DNA footprinting and molecular modeling. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 1995;3:671–677. doi: 10.1016/0968-0896(95)00052-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fiel RJ, Beerman TA, Mark EH, Datta-Gupta N. DNA strand scission activity of metalloporphyrins. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commu. 1982;107:1067–1074. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(82)90630-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aft RL, Mueller GC. Hemin-mediated DNA strand scission. J. Biol. Chem. 1983;258:12069–12072. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Groves JT, Farrell TP. DNA cleavage by a metal chelating tricationic porphyrin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:4998–5000. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Praseuth D, Gaudemer A, Verlhac JB, Kraljic I, Sissoeff I, Guille E. Photocleavage of DNA in the presence of synthetic water-soluble porphyrins. Photochem. Photobiol. 1986;44:717–724. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1986.tb05529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chatterjee SR, Shetty SJ, Devasagayam TPA, Srivastava TS. Photocleavage of plasmid DNA by the prophyrin meso-tetrakis[4-(carboxymethyleneoxy)phenyl]porphyrin. J. Photochem. Photobil. B. 1997;41:128–135. doi: 10.1016/s1011-1344(97)00094-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.James BR, Meng GG, Posakony JJ, Ravensbergen JA, Ware CJ, Skov KA. Porphyrins and metalloporphyrins: potential hypoxic agents. Metal-based drugs. 1996;3:85–90. doi: 10.1155/MBD.1996.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krijt J, Stranska P, Maruna P, Vokurka M, Sanitrak J. Herbicide-induced experimental variegate porphyria in mice: tissue porphyrinogen accumulation and response to porphyrogenic drugs. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1997;75:1181–1196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng Q, Nanqiang L, Yu-Yang J. Electrochemical studies of CuTMAP Interaction with DNA and Determination of DNA. Microchem. J. 1998;58:39–51. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berlin K, Jain KR, Simon DM, Richert C. A porphyrin embedded in DNA. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:1527–1535. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang CZ, Li KA, Tong SH. Determination of nucleic acids by a resonance light-scattering technique with α,β,γ,δ -Tetrakis[4-trimethylammoniumyl)phenyl]porphine. Anal. Chem. 1996;68:2259–2263. doi: 10.1021/ac9511105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anantha NV, Azam M, Sheardy RD. Porphyrin binding to quadruplexed T4G4. Biochem. 1998;37:2709–2714. doi: 10.1021/bi973009v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gray TA, Yue KT, Marzilli LG. Effect of N-alkyl substituents on the DNA binding properties of meso-tetrakis (4-N-alkylpyridinium-4-yl)porphyrins and their nickel derivatives. J. Inorg.Biochem. 1991;41:205–219. doi: 10.1016/0162-0134(91)80013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feng Q, Nan-Qiang L, Yu-Yang J. Electrochemical studies of NiTMpyP and interaction with DNA. Talanta. 1998;45:787–793. doi: 10.1016/s0039-9140(97)00154-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feng Q, Nan-Qiang L, Yu-Yang J. Electrochemical studies of porphyrin interacting with DNA and determination of DNA. Anal. Chim. Acta. 1997;344:97–104. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brian PH, Jenny S, Daniel J, David R, McMillin Luminescence studies of the intercalation of Cu(TMpyP4) into DNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:8997–9002. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mestre B, Jakobs A, Pratviel G, Meunier B. Structure/Nuclease activity relationships of DNA cleavers based on cationic metalloporphyrin-oligonucleotide conjugates. Biochem. 1996;35:9140–9149. doi: 10.1021/bi9530402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilson WD, Lynda R, Zhao M, Lucjan S, Boykin D. The search for structure-specific nucleic acid-interactive drugs: Effects of compound structure on RNA versus DNA interaction strength. Biochem. 1993;32:4098–4104. doi: 10.1021/bi00066a035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ward B, Skorobogaty A, Dabrowiak JC. DNA cleavage specificity of a group of cationic metalloporphyrins. Biochem. 1986;25:6875–6883. doi: 10.1021/bi00370a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bromley SD, Ward B, Dabrowiak JC. Cationic porphyrins as probes of DNA structure. Nucl. Acids Res. 1986;14:9133–9148. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.22.9133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fiel RJ. Porphyrin-nucleic acid interactions A Review. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 1989;6:1259–1274. doi: 10.1080/07391102.1989.10506549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.D’Souza F, Deviprasad RG, Hsieh YY. Synthesis and studies on the electrocatalytic reduction of molecular oxygen by non-planar cobalt(II) tetrakis- (N-methyl pyridyl)-β-octabromoporphyrin. J. Electroanal.Chem. 1996;411:167–171. [Google Scholar]

- 31.D’Souza F, Hsieh YY, Deviprasad RG. Four-electron electrocatalytic reduction of dioxygen to water by an ion-pair cobalt porphyrin dimer adsorbed on a glassy carbon electrode. Chem. Comm. 1998;9:1027–1028. [Google Scholar]

- 32.D’Souza F, Hsieh YY, Deviprasad RG. Electrochemical and spectroelectrochemical characterization of water-soluble, β-pyrrole-brominated cobalt porphyrins. J. Porphy. Phthalo. 1998;2:429–437. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rogriguesz M, Kodadek T, Torres M, Bard AJ. Cleavage of DNA by electrochemically activated Mn(III) and Fe(III) complexes of meso-tetrakis(N-methyl-4-pyridyniumyl)porphine. Bioconjugate Chem. 1990;1:123–131. doi: 10.1021/bc00002a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Basile LA, Raphael AL, Barton JK. Metal-activated hydrolytic cleavage of DNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987;109:7550–7551. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sequaris JM, Valenta P. AC voltammetry: a control method for the damage to DNA caused in vitro by alkylating mutagens. J. Electroanal. Chem. 1987;227:11–20. and references cited therein. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Atta RB, Long EC, Hecht SM. Electrochemical activation of oxygenated Fe-bleomycin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:2722–2724. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Benesi HA, Hildebrand JH. A spectrophotometric investigation of the interaction of iodine with aromatic hydrocarbons. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1949;71:2703–2707. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Armistead PM, Thorp HH. Modification of indium tin oxide electrodes with nucleic acids: detection of attomole quantities of immobilized DNA by electrocatalysis. Anal. Chem. 2000;72:3764–3770. doi: 10.1021/ac000051e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pasternack RF. Circular dichroism and the interactions of water soluble porphyrins with DNA-a mini review. Chirality. 2003;15:329–332. doi: 10.1002/chir.10206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dalgleish DG, Feil MC, Peacocke AR. The circular dichroism of complexes of 2,7-di-tertiary-butyl proflavine with DNA. Biopolymers. 1972;11:2415–2422. doi: 10.1002/bip.1972.360111204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Qu J, Shen Y, Qu X, Dong S. Electrocatalytic reduction of oxygen at multi-walled carbon nanotubes and cobalt porphyrin modified glassy carbon electrode. Electroanal. 2004;16:1444–1450. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ivanov VI, Minchenkova LE, Schyolkina AK, Poletayev AI. Different conformations of double-stranded nucleic acid in solution as revealed by circular dichroism. Biopolymers. 1973;12:89–110. doi: 10.1002/bip.1973.360120109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yun BH, Jeon SH, Cho Tae-Sub, Yi SY, Sehlstedt U, Kim SK. Binding mode of porphyrins to poly[d(A-T)2] and poly[d(G-C)2] Biophy Chem. 1998;70:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(97)00031-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bard AJ, Faulkner LR. Electrochemical Methods Fundamentals And Applications. 2nd Ed. New York: John Wiley; 2001. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Cyclic voltammograms of calf thymus DNA in the presence of free-base and zinc porphyrins. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.