Abstract

Purpose

To determine whether improved self-gating (SG) algorithms can provide superior synchronization accuracy for retrospectively gated cine MRI.

Materials and Methods

First difference, template matching and polynomial fitting algorithms were implemented to improve the synchronization of MRI data using cardiac SG signals. Cine datasets were acquired during short-axis, two-, three-, and four chamber cardiac MRI scans. The root-mean-square (RMS) error of SG synchronization positions compared to detected R-wave positions were calculated along with the mean square error (MSE) and peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR) comparing SG to ECG gated images. Overall image quality was also compared by two expert reviewers.

Results

RMS errors were highest for the first difference method for all orientations. Improvements for both template matching and cubic polynomial fitting methods were significant for two, three, and four chamber scans. MSE values were lower and PSNR were significantly higher for the cubic method compared to the first difference method for all orientations. Reviewers scored the images to be of comparable quality.

Conclusion

Template matching and polynomial fitting improved the accuracy of cardiac cycle synchronization for two, three, and four chamber scans; improvements in SG synchronization accuracy were reflected in improvements in analytical image quality. Implementation of robust post-processing algorithms may bring SG approaches closer to clinical utilization.

Keywords: Self-gating, cardiac MRI, retrospective gating

INTRODUCTION

Cardiac MRI can be technically challenging because data acquisition must be synchronized with the cardiac cycle to avoid motion artifacts. Artifacts due to respiratory motion can be prevented by either having subjects perform breath-holds during scanning procedures or alternatively using navigator echoes to trigger data acquisition at expiration. For cardiac MRI, the spatial frequency domain, commonly referred to as k-space, is typically filled over multiple cardiac cycles in order to capture all the data needed to create images at each cardiac phase. Retrospective gating for cardiac cine MRI is accomplished by repeatedly sampling each region of k-space for a length of time equal to the maximum expected cardiac cycle length; after the scan these datasets are temporally aligned based upon electrocardiogram (ECG) data sampled during the scan. Alternatively, real-time imaging can be used to fill k-space in a single cardiac cycle, but the temporal and spatial resolution of gated, segmented approaches are generally superior.

The R-wave of the ECG is mostly commonly detected for synchronization of MRI data acquisition to the cardiac cycle. For a normal ECG signal, the QRS complex has the highest amplitude peak and sharpest upstroke, which simplifies detection. However, the ECG is often corrupted in the MR environment, due to gradient switching (1,2), radiofrequency interference (3,4), and the magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) effect (5,6). These sources of interference can cause false detection of temporal synchronization positions, leading to poor MR image quality particularly in patients with severe heart disease. Improvements over the state-of-the-art which reduce patient setup time can increase patient throughput, subsequently reducing the cost of MRI scans, which may potentially broaden the use of cardiac MRI for routine clinical exams. Consequently, other techniques for gating have been investigated, including cancellation of MHD (7), vectorcardiography (VCG) (8,9) and self-gating (10,11).

Self-gating (SG) is a technique in which changes in the raw MR data over time are used to form a signal that may be used for retrospective synchronization of data to the cardiac cycle. The SG signal is typically produced by sampling the center of k-space repeatedly during cine data acquisition by interleaving the collection of non-phase encoded k-space lines (kpe = 0). For bright-blood gradient-echo and steady-state free-precession imaging approaches, changes in the SG signal over time are primarily related to changes in through-plane blood flow velocity and the amount of blood present in the imaging plane, though other moving structures may also contribute. Due to the nature of the SG signal, it does not suffer from the multiple sources of interference that corrupt the ECG and VCG. SG also has the advantage that no lead system is required, resulting in reduced patient setup time. In principle, SG also may be advantageous in situations when the electrical activity and mechanical activity do not correlate, since in SG, data synchronization is dependent upon the intrinsic motion of the heart rather than the electrical activity.SG is not currently used in the clinical setting for cardiac MRI. One reason may be the lack of robust post-processing algorithms for derivation of synchronization triggers from SG signals. Initial SG approaches used a simple first difference algorithm to detect signal peaks for retrospective gating (10,11). While the ultimate goal of this research area is for SG to one day be used clinically, the purpose of our current study was to test whether a more complex algorithm, such as template matching or polynomial fitting, may be employed to improve the accuracy of retrospective cardiac synchronization.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study protocol was approved by our institutional review board, and written informed consent was obtained from each subject. The subject population consisted of fourteen healthy subjects, twelve males and two females. The age among the subject population ranged from 25 to 53 years (mean ± standard deviation, 37 ± 10 years). Subjects underwent cardiac cine MRI scans at four different orientations using a Siemens Magnetom Sonata 1.5 Tesla whole-body clinical MRI scanner. These scans included two chamber (n=14), three chamber (n=11), four chamber (n=14), and short-axis (n=12) views. SG signals were recorded during each scan from the same 3–4 surface receiver coils used for reception of MR imaging data. For each study a conventional multi-element spine array and two-channel chest array were used for signal reception. Breath-hold cine MRI scans were performed using a conventional SSFP pulse sequence modified to collect additional raw data samples at the center of k-space following the acquisition of each line of imaging data, as described by Crowe et al (11). Specific sequence parameters included: TR(includes both gating and imaging echoes) = 3.4 ms, TE = 1.2 ms, FOV = 300–360mm, 60° flip-angle, 192 matrix, 15 lines/segment. Using the ECG monitoring system of the MR scanner, QRS complexes were detected, and for each k-space line, the time after each previously detected QRS complex was stored. These time stamps facilitate offline retrospective synchronization to the cardiac cycle for the reconstruction of cine image series.

The SG signals were derived from the sum of the magnitudes of the 32 points sampled at the center of k-space (no phase encoding). MATLAB (The Math Works, Inc., Natick, MA) code was written to perform the signal processing tasks. The first 0.75 seconds of each SG signal was discarded to allow the signal to first reach steady state prior to detection of cardiac cycle synchronization positions; SG signals were inverted. Of the multiple channels available for each scan, the channel with minimal noise (lowest high frequency power), minimal baseline drift (lowest slope of line fit to troughs), and highest amplitude (greatest average difference between peaks and troughs) was chosen for analysis.

Cardiac cycle synchronization positions were determined by three different methods: first difference, template matching, and polynomial fitting. The first difference method consisted of low-pass filtering the signal with a 60-tap FIR filter with cut off frequency of 10Hz; SG signals were filtered both in the forward and reverse directions in order to have zero phase distortion. The first derivative was computed, and positive-to-negative sign changes of the derivative were identified as synchronization positions. Template matching consisted of creating a median template with length equal to half the median R-R interval computed by the first difference method. The cross-correlation of the median template and original signal was computed, and the peaks of the cross-correlation signal were determined by identifying positive-to-negative sign changes of the derivative of the cross-correlation signal; these peaks were used as the synchronization positions. A similar procedure to template matching was used for polynomial fitting, except that polynomials (absolute value, parabolic, and cubic) were used as the templates. The length of each polynomial was also equivalent to the median R-R interval, as determined by the first difference method.

The SG synchronization positions identified from these methods were compared with ECG QRS positions. The total number of synchronization positions and the number of missed synchronization positions for each detection method were recorded. The range, mean, and standard deviation of propagation delay for each SG synchronization position relative to each QRS position was computed. The performance metric used to make the comparison was the root-mean-square (RMS) error, defined as variability relative to the mean difference between SG synchronization positions and detected QRS positions. The RMS error was calculated using the following equations, where N is the number of detection synchronization positions, SG(i) is the ith detected SG synchronization position and ECG(i) is the position of the ith QRS complex:

Variability relative to this mean was chosen as our performance metric to account for constant phase differences between the synchronization schemes. The differences in RMS errors between the methods were analyzed by paired t-tests to determine if the differences in SG synchronization positions were statistically significant.

Cardiac MR images were reconstructed from the computed retrospective synchronization methods; sum-of-squares was used to combine image data from different channels. The mean delay between ECG synchronization times and SG synchronization times was used to synchronize each SG image series with the ECG-gated image series to facilitate proper image comparison. Mean squared error (MSE) and peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR) of the images were calculated to analytically compare image quality. MSE and PSNR are standard global image quality metrics involving the comparison of two images; in this study, the ECG-gated images were used as the “gold standard” images, and the SG images were treated as the modified images. MSE is the cumulative squared error between the two images (12). Therefore, a low MSE value indicates less error, meaning high correlation between the images. It is calculated as:

where I1(x,y) is the original image, I2(x,y) is the modified image, and M,N are the dimensions of the images. The calculation of PSNR involves the value of MSE; it is computed as:

The units of PSNR are in decibels (dB); higher PSNR indicates better image quality. While PSNR is calculated based upon image MSE, the PSNR metric additionally considers the maximum pixel value within the image.

Images were also compared subjectively and independently by two expert reviewers, with over 10 years combined experience in cardiac MRI, blinded to the quantitative results and to the gating method used to produce the images. Each image series for the entire cardiac cycle was compiled into a cine loop at a rate of 15 frames/second. For each subject and each scan orientation, the three sets of image series (ECG, first difference, cubic) were displayed simultaneously, with slide placement randomized. We used an absolute image scoring system, described by White et al. for a previous SG study (13), with the following point assignments: 1 point = poor image quality, precluding adequate visualization of structures for interpretation, 2 points = image quality adequate at best for interpretation, 3 points = good image quality, and 4 points = excellent image quality and definition of fine anatomic structures. The expert reviewers also ranked the image series, with the possibility for ties when image series were deemed of the same quality. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) tests were applied to both the absolute image quality scores and comparative rankings for each reviewer to determine if differences in scores and/or ranks were statistically significant among the different retrospective synchronization methods.

RESULTS

SG Signal Characteristics

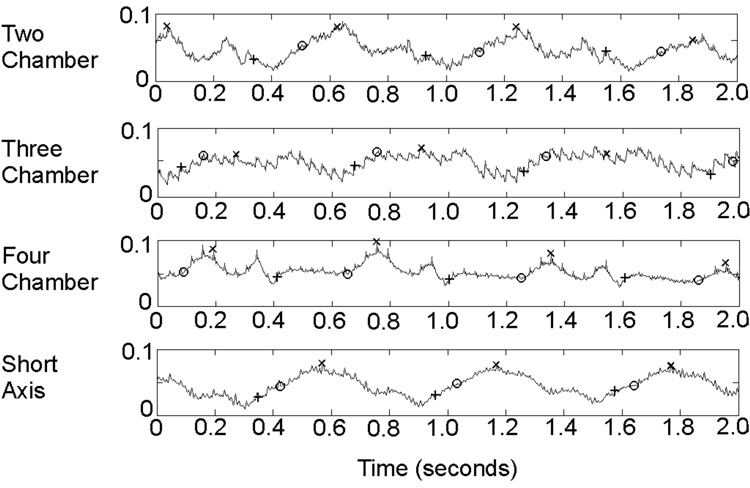

The duration of the signals used for analysis ranged from 5.67 to 7.35 seconds (7.04 ± 0.64 seconds). The signal duration varied between the subjects due to the different resting heart rates within the subject population; these heart rates ranged from 63.0 to 104.9 bpm (82.2 ± 12.6 bpm). The signal morphology also varied from one subject to the next, and also within the same subject, signal morphology varied between the channels. Representative SG signals from a single channel for each of the four scan orientations are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Raw, unfiltered two-second segments of self-gating signals for a single channel at each of the four imaging orientations; amplitude shown on the y-axis is in arbitrary units. ECG and SG synchronization positions are identified on the signals; “+” = ECG, “O” = Cubic polynomial fitting, and “X” = First difference method.

Synchronization Position Data

Synchronization positions are shown on sample SG signals in Figure 1. A total of 724 cardiac cycles from 14 volunteers were examined in this study. Of those cardiac cycles, the number of missed synchronization positions for each method arranged by scan type are shown in Table 1. For all the methods, no false positives were detected. The propagation delay for each method varied. These data are also shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

For each scan type, the left column is the number of missed synchronization positions for each method; the right column is the propagation delay for each method (mean ± standard deviation and range).

| Two Chamber | Three Chamber | Four Chamber | Short Axis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Missed | Prop. Delay (ms) | Missed | Prop. Delay (ms) | Missed | Prop. Delay (ms) | Missed | Prop. Delay (ms) | |

| First Difference | 0 | 276 ± 37 | 0 | 232 ± 45 | 0 | 290 ± 105 | 0 | 209 ± 27 |

| 228–373 | 152–275 | 184–511 | 137–246 | |||||

| Template Matching | 2 | 360 ± 78 | 1 | 391 ± 51 | 0 | 299 ± 84 | 0 | 344 ± 37 |

| 153–439 | 318–476 | 168–452 | 279–417 | |||||

| Absolute Value | 1 | 295 ± 64 | 1 | 280 ± 97 | 0 | 216 ± 56 | 1 | 231 ± 17 |

| 243–439 | 135–512 | 141–297 | 200–260 | |||||

| Parabola | 1 | 307 ± 69 | 5 | 255 ± 57 | 0 | 217 ± 57 | 0 | 232 ± 18 |

| 243–446 | 136–322 | 140–297 | 199–259 | |||||

| Cubic | 1 | 156 ± 71 | 0 | 137 ± 33 | 1 | 135 ± 96 | 0 | 95 ± 22 |

| 86–374 | 100–186 | 39–389 | 64–128 | |||||

RMS Errors

The mean and standard deviation of the RMS errors were computed for each of the four orientation scans for all synchronization methods; these data as well as the ranges of the RMS errors are summarized in Table 2. For all scan types, the first difference method produced the highest mean and highest standard deviation of the RMS errors.

Table 2.

Mean ± standard deviation of RMS errors for all four scan types; all values given in ms. P-values, shown below in parentheses, are calculated to compare the first difference method with template matching and three polynomial fitting self-gating synchronization methods.

| Two Chamber | Three Chamber | Four Chamber | Short Axis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Difference | 24.9 ± 11.5 | 17.3 ± 10.9 | 20.6 ± 7.8 | 10.9 ± 4.9 |

| Template Matching | 17.4 ± 5.7 (p=0.006) |

12.8 ± 7.5 (p=0.015) |

14.9 ± 5.0 (p=0.026) |

9.1 ± 3.3 (p=0.358) |

| Absolute Value | 16.8 ± 7.0 (p=0.015) |

15.8 ± 8.4 (p=0.463) |

15.0 ± 5.0 (p=0.012) |

7.4 ± 3.0 (p=0.066) |

| Parabola | 17.1 ± 9.1 (p=0.036) |

16.0 ± 8.8 (p=0.750) |

15.1 ± 5.6 (p=0.013) |

8.6 ± 3.1 (p=0.228) |

| Cubic | 13.6 ± 9.0 (p=0.007) |

9.8 ± 4.8 (p=0.016) |

13.2 ± 7.3 (p=0.026) |

9.5 ± 3.9 (p=0.136) |

P-values from the paired t-test evaluating statistical significance between RMS errors from first difference and the other methods are also shown in Table 2. No SG synchronization method produced p-values below 0.05 for all scan types. However, there was a statistically significant improvement for two, three, and four chamber cardiac MRI scans when using the template matching and cubic polynomial fitting methods compared with the first difference method. However, there was no statistically significant improvement for the short axis scan for either method. The lowest set overall of p-values was for the cubic polynomial fitting method, so this method was chosen for image comparison with the first difference method.

Analytical Image Comparison

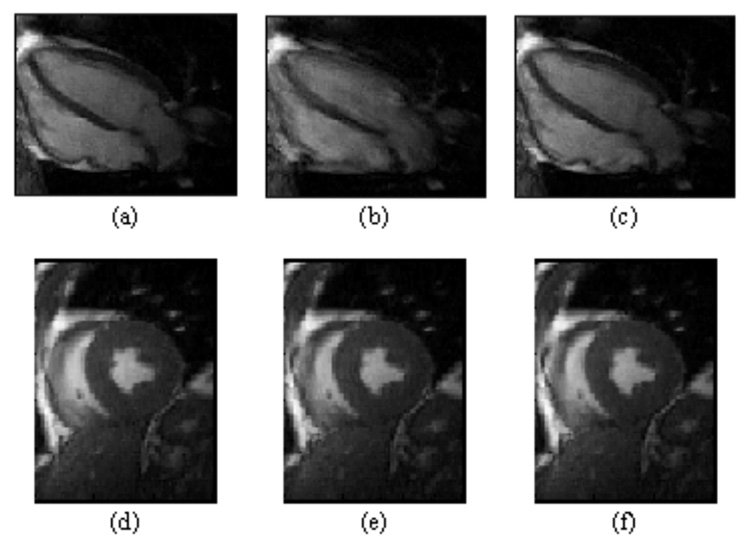

Sample MR images reconstructed using the different retrospective methods are shown in Figure 2. The MSE and PSNR values from the image comparison are shown in Table 3. The MSE values for the cubic polynomial fitting method were lower than those for the first difference method for all scan types. Similarly, the PSNR values for the cubic method were higher than the first difference method for all scan types.

Figure 2.

Upper row of mid-systolic four-chamber orientation images were reconstructed using retrospective ECG gating (a) and self-gating with first-difference (b) and cubic polynomial fitting (c) synchronization algorithms. Image (b) is clearly blurred, while (a) and (c) are of similar quality. Lower row of mid-systolic short-axis images were reconstructed using retrospective ECG gating (d) and self-gating with first-difference (e) and cubic polynomial fitting (f) synchronization algorithms. Each of these representative short-axis images is of similar quality.

Table 3.

Mean ± standard deviation of MSE (left) and PSNR (right) for all scan types. P-values for MSE and PSNR for all scan types are also shown in order to observe if differences between MSE and PSNR values for first difference compared with cubic polynomial fitting are statistically significant.

| MSE | PSNR | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scan Type | First Difference | Cubic | P-value | Scan Type | First Difference | Cubic | P-value |

| Two chamber | 11.3 ± 8.2 | 9.1 ± 5.8 | 0.0317 | Two chamber | 38.9 ± 3.0 | 39.8 ± 2.8 | 0.0007 |

| Three chamber | 18.4 ± 12.8 | 15.2 ± 12.1 | 0.0002 | Three chamber | 36.9 ± 3.6 | 37.8 ± 3.5 | 0.0014 |

| Four chamber | 16.2 ± 8.8 | 12.0 ± 9.4 | 0.0188 | Four chamber | 37.1 ± 2.7 | 38.7 ± 3.2 | 0.0111 |

| Short Axis | 9.7 ± 5.4 | 8.4 ± 4.8 | 0.0059 | Short Axis | 39.7 ± 3.0 | 40.0 ± 3.0 | 0.0418 |

The p-values, also shown in Table 3, indicate that the lower MSE and higher PSNR values for the cubic method were statistically significant for all scan orientations. Therefore, according to analytical methods, the cubic polynomial fitting algorithm produced better quality images in comparison with the ECG-gated images than did the first difference method.

Expert Reviewer Scoring

The absolute image quality scores and image series comparison ranks for both reviewers are shown in Table 4. For Reviewer #1, the mean absolute image quality score was the same for ECG and SG cubic polynomial synchronization methods, and the score for first difference was slightly lower. This reviewer gave ECG the highest mean ranking, cubic received the second highest, and first difference received the lowest ranking. For Reviewer #2, the mean quality score was highest for ECG, second highest for cubic method, and lowest for first difference method. The rankings for this reviewer followed the same pattern with ECG receiving the best ranking and first difference receiving the worst ranking. However, through ANOVA tests we found that none of these differences were statistically significant for either of the reviewers.

Table 4.

Absolute quality scores and comparative rankings from two independent reviewers.

| Absolute Quality Scores | Comparative Rank | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reviewer #1 | Reviewer #2 | Reviewer #1 | Reviewer #2 | |

| ECG | 2.31 ± 0.86 | 2.96 ± 0.66 | 1.12 ± 0.33 | 1.36 ± 0.64 |

| First Difference | 2.29 ± 0.86 | 2.72 ± 0.80 | 1.31 ± 0.58 | 1.77 ± 0.81 |

| Cubic Polynomial Fitting | 2.31 ± 0.86 | 2.87 ± 0.68 | 1.14 ± 0.35 | 1.62 ± 0.68 |

DISCUSSION

The main findings of this work were that both template matching and cubic polynomial fitting improved the accuracy of retrospective cardiac cycle synchronization compared to the first difference method for two, three, and four chamber scans; improved synchronization was reflected in improvements in analytical image quality, but subjective image quality was similar.

For two, three, and four chamber scans, SG cardiac cycle synchronization was improved by using template matching and cubic polynomial fitting rather than the first difference method. This improvement probably arises since SG signals are highly dependent upon in-plane and through-plane blood flow patterns; therefore, two, three, and four chamber orientations may result in more complex signal morphologies. The increased complexity signals may present the need for more advanced trigger detection methods.

There was no statistically significant improvement for either template matching or cubic polynomial fitting for the short axis scan. Nevertheless, trigger jitter in ECG gating was shown to be 10–15ms in (14), and all SG algorithms implemented for this study produced results in agreement with this error. Due to the simplistic view of the anatomy in short axis scans, less complex SG signals result; consequently, first difference, template matching, and polynomial fitting methods all performed well.

There were several limitations in this study. One limitation was the method by which the SG signal was derived. We used the magnitude sum of 32 samples at the center of k-space; however, a different set of magnitude points or the phase rather than the magnitude could conceivably provide additional and/or superior motion information, though this investigation will be the focus of future work. Another limitation was that ECG gating was used as the gold standard for computation of the RMS errors as well as MSE and PSNR, but, as discussed in the Introduction, QRS detection errors can occur due to the multiple sources of interference which corrupt the ECG within the MR environment. Therefore, in order to confirm accurate ECG gating during each of the volunteer studies, the ECG waveform was visualized in real-time along with the system derived trigger positions for each. In one study where there was a missed trigger on the ECG, the acquisition was repeated. We did not separately obtain the ECG and perform our own post-processing for QRS detection. This remained a limitation for the study as we relied entirely upon the vendor provided QRS detection system for accurate ECG gating.

Certain heart disease states can result in diminished QRS amplitude or altered QRS morphology, such as disease of the pericardial sac or right heart overload, which, when coupled with the sources of interference in the MR environment, can make QRS detection extremely difficult. In these circumstances, SG may be advantageous because it does not rely on electrical activity. Nevertheless, the dependence of SG on mechanical motion may prove to be disadvantageous in other circumstances, such as patients with reduced heart wall motion and cardiac output.

A limitation of SG as a gating technique in general is that it has not yet been shown to be a feasible technique for prospective gating. The methods presented here to identify the cardiac synchronization positions cannot be used prospectively, so additional investigation must be performed in order to use SG for prospective triggering.

Analytical comparison of the images by MSE and PSNR indicated that improvements in SG synchronization were similarly reflected by improvements in image quality. However, expert reviewer evaluation indicated that there were no statistically significant subjective differences between the images using the different SG algorithms. Consequently, though analytical methods revealed differences in image quality when comparing SG methods, the differences in the images were not discernible to the reviewers. This apparent discrepancy may result because the differences in the images were not clinically relevant features which the reviewers examined. It is important to note that expert reviewers scored the looping image series, while MSE and PSNR are computed for the individual images which comprised the image series. The discrepancy may also result due to the sample size of the study; further tests with larger sample sizes could determine if this is the cause.

Future work should include comparison of SG with VCG gating methods. VCG has recently proven to be a more robust gating technique than conventional ECG gating methods.

In conclusion, from both analytical and subjective analyses, we can reasonably conclude that cubic polynomial fitting presents a synchronization algorithm for SG that produces image series that are of comparable good quality to ECG-gated images. Though SG is not currently used in clinical practice, implementation of these more robust post-processing algorithms should bring SG approaches closer to clinical feasibility.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: This material is based upon work supported under a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship, in part by National Institutes of Health grant number NHLBI HL079148, and in part by a grant from the Dr. Scholl Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Polson MJR, Barker AT, Gardiner S. The effect of rapid rise-time magnetic fields on the ECG of the rat. Clin Phys Physiol Meas. 1982;3:231–234. doi: 10.1088/0143-0815/3/3/008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wendt RE, Rokey R, Vick W, Johnston DL. Electrocardiographic gating and monitoring in NMR imaging. Magn Reson Imaging. 1988;6:89–95. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(88)90528-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Damji AA, Snyder RE, Ellinger DC, Witkowski RX, Allen PS. RF interference suppression in a cardiac synchronization system operating in a high magnetic field NMR imaging system. Magn Reson Imaging. 1988;6:637–640. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(88)90086-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shetty AN. Suppression of radiofrequency interference in cardiac gated MRI: a simple design. Magn Reson Med. 1988;8:84–88. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910080110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Togawa T, Okai O, Oshima M. Observation of blood flow e.m.f. in externally applied strong magnetic field by surface electrodes. Med Biol Eng. 1967;5(2):169–170. doi: 10.1007/BF02474505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tenforde TS. Magnetically induced electric fields and currents in the circulatory system. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2005;87:279–288. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nijm GM, Swiryn S, Larson AC, Sahakian AV. Extraction of the magnetohydrodynamic blood flow potential from the surface electrocardiogram in magnetic resonance imaging. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s11517-008-0307-1. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fischer SE, Wickline SA, Lorenz CH. Novel real-time R-wave detection algorithm based on the vectorcardiogram for accurate gated magnetic resonance acquisitions. Magn Reson Med. 1999;42:361–370. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199908)42:2<361::aid-mrm18>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chia JM, Fischer SE, Wickline SA, Lorenz CH. Performance of QRS detection for cardiac magnetic resonance imaging with a novel vectorcardiographic triggering method. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2000;12:678–688. doi: 10.1002/1522-2586(200011)12:5<678::aid-jmri4>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larson AC, White RD, Laub G, McVeigh ER, Li D, Simonetti OP. Self-gated cardiac cine MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2004;51:93–102. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crowe ME, Larson AC, Zhang Q, et al. Automated rectilinear self-gated cardiac cine imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2004;52:782–788. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gonzales RC, Woods RE. Digital image processing. 3rd edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall; 2008. Image restoration and reconstruction; p. 354. [Google Scholar]

- 13.White RD, Paschal CB, Clampitt ME, Spraggins TA, Lenz GW. Electrocardiograph-independent, “wireless” cardiovascular cine MR imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1991;1:347–355. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880010313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thompson RB, McVeigh ER. Flow-gated phase-contrast MRI using radial acquisitions. Magn Reson Med. 2004;52:598–604. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]