Abstract

Intramolecular Heck reactions of α,β-unsaturated 2-haloanilides derived from azatricyclo[4.4.0.02,8]decanone 5 efficiently install the congested spirooxindole functionality of gelsemine. Depending upon the Heck reaction conditions and the nature of the β-substituent, either products having the natural or unnatural configuration of the spirooxindole group are formed predominantly. Efforts to elaborate the hydropyran ring of gelsemine from the endo-oriented nitrile substituent of pentacyclic Heck product 18 were unsuccessful. Important steps in the ultimately successful route to (±)-gelsemine (1) are: (a) intramolecular Heck reaction of tricyclic β-methoxy α,β-unsaturated 2-iodoanilide 68 in the presence of silver phosphate to form pentacyclic product 69 having the unnatural configuration of the spirooxindole fragment, (b) formation of hexacyclic aziridine 80 from the reaction of cyanide with intermediate 79 containing an N-methoxycarbonyl-β-bromoethylamine fragment, (c) introduction of C17 by ring-opening of the aziridinium ion derived from aziridine 80, and (d) base-promoted skeletal rearrangement of pentacyclic equatorial alcohol 82 to form the oxacyclic ring and invert the spirooxindole functional group to provide hexacyclic gelsemine precursor 83.

Introduction

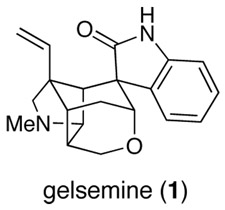

At the time its structure was elucidated,2 the compact hexacyclic cage structure of gelsemine (1) posed implicit challenges to the capabilities of organic synthesis.3 In the intervening 40 years, a number of approaches to gelsemine have been described and much imaginative chemistry has been developed in this context.4–16 The first total syntheses of (±)-gelsemine were disclosed in 1994 by the groups of Johnson,17 Speckamp,18 and Hart (21-oxogelsemine),19 additional total syntheses were subsequently reported from the laboratories of Fukuyama,20 Overman21 and Danishefsky,22 and a total synthesis of (+)-gelsemine was disclosed by Fukuyama and co-workers in 2000.23

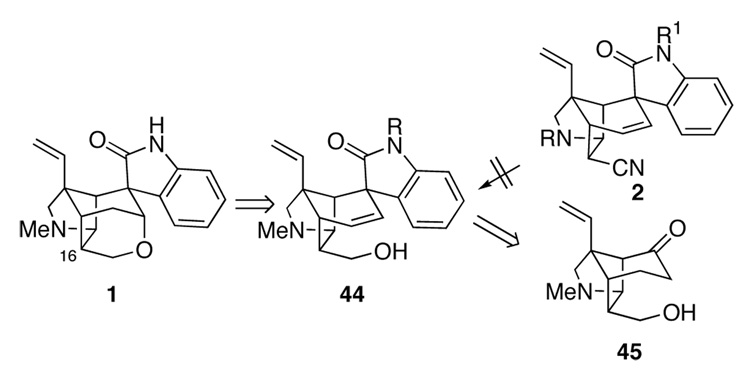

The preceding paper in this series presented full details of the early stages of our gelsemine total synthesis, which resulted in a direct route for preparing azatricyclo[4.4.0.02,8]decanone 5 from 3-methylanisole (6) (Figure 1).24 The bromide functional group of azatricyclodecanone 5 provides a potential handle for fabricating the hydropyran ring, whereas the ketone carbonyl was seen as a locus for generating the spirooxindole unit. At the outset of these studies, we envisaged that this latter elaboration would be particularly demanding as installation of the spirooxindole on the azatricyclodecane framework introduces a 1,3-diaxial interaction between the oxindole carbonyl group and the angular vinyl group. As events developed, elaboration of the spirooxindole proved to be relatively easy as a result of the remarkable ability, first revealed in these studies,9a of intramolecular Heck reactions to form congested quaternary carbon centers.25 Herein we provide full details of our development of Heck cyclization routes to the spirooxindole unit of gelsemine, our unsuccessful efforts to elaborate the hydropyran ring from pentacyclic intermediates 2, and the final endgame strategy that allowed (±)-gelsemine (1) to be fashioned from 3.

Figure 1.

Synthetic strategy.

Results and Discussion

Elaboration of the Spirooxindole Using an Intramolecular Heck Reaction

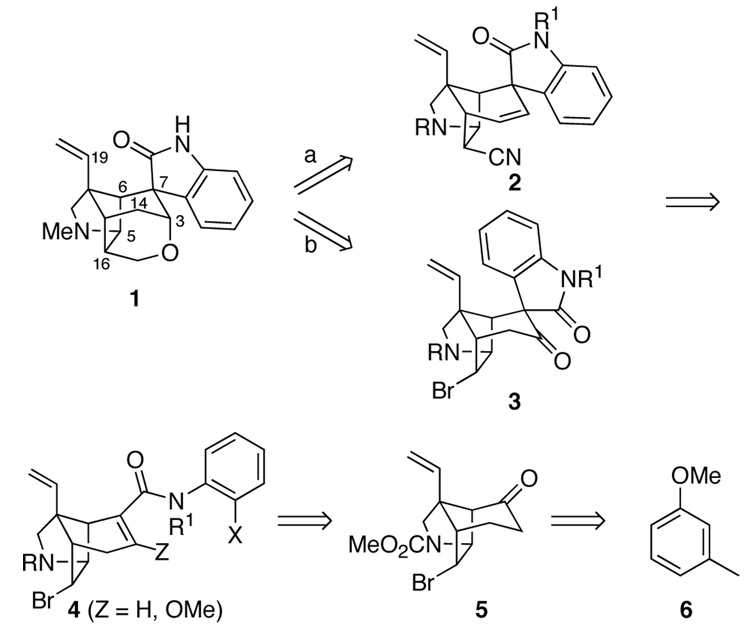

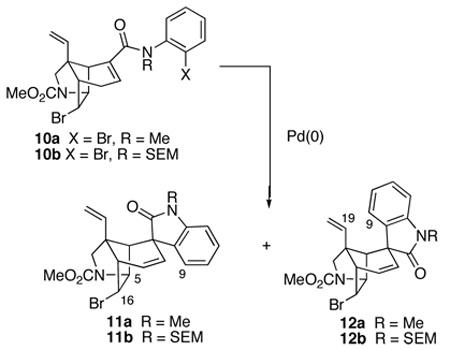

With a workable synthesis of tricyclic ketone 5 in hand,24 the next task was to introduce the α,β-unsaturated anilide functionality that would serve as a precursor of the spirooxindole unit. Intermediates 4 wherein Z = H were chosen for our initial attempts to form the spirooxindole functionality, because the projected cyclization was deemed speculative enough without requiring insertion of tetrasubstituted double bonds.26 To this end, the lithium enolate of ketone 5 was trapped with N-phenylbis(trifluoromethanesulfonimide) (7) to generate enol triflate 8 in 78% yield (Scheme 1). Palladium-catalyzed carbonylative cross-coupling of triflate 8 with 2-bromoaniline gave 2-bromoanilide 9 in 74% yield.27 However, this coupling proceeded in poor yield with 2-iodoaniline or N-benzyl-2-bromoaniline.28 Protection of the amide nitrogen of 9 with a methyl or 2-(trimethylsilyl)ethoxymethyl (SEM) group provided α,β-unsaturated amides 10a and 10b in good yields.

Scheme 1.

We now were ready to explore generating the critical spiro-fused oxindole fragment of gelsemine by intramolecular Heck reaction. At the time these studies began, we had shown that intramolecular Heck reactions could be employed to elaborate spirooxindole units onto simple, unfunctionalized carbocyclic rings.9a However, the projected cyclization of 9 or 10 was far more demanding: these substrates are more highly functionalized, their C-C double bonds are more hindered and two epimeric Heck products could be formed in the Heck cyclizations (equation 1). Migratory insertion from the α-face would lead to spirooxindole 11, whereas insertion from the β-face would provide the undesired epimer 12. Molecular mechanics (MM2) calculations indicated that oxindole 11, wherein the aromatic ring is equatorially disposed, is more stable (~3 kcal/mol); however, it was not clear to what extent at all this preference would be felt in the stereodetermining step.

|

(1) |

Salient results of our extensive studies of Heck cyclizations in the gelsemine series are summarized in Table 1. Initial attempts to cyclize secondary amide 9 failed, giving only reduction product. This result was not unexpected, because cyclization of a secondary amide requires population of a high-energy E amide conformation. In contrast, tertiary anilides 10a,b cyclized under a variety of Heck reaction conditions. Cyclizations were examined initially using (Ph3P)4Pd as the catalyst in refluxing acetonitrile. Changing the amide protecting group from Me to SEM had little effect on the low stereoselectivity observed in the reaction (entries 1 and 2).29 Cyclization was more sluggish in refluxing tetrahydrofuran; however, stereoselectivity remained unaltered (entries 4 and 5). The configuration of oxindole products 11 and 12 was determined readily by 1H NMR NOE experiments. For diastereomer 11, a positive NOE is observed between the hydrogens at C9, C5 and C16, whereas for epimer 12, a positive NOE is seen between the C9 and C19 hydrogens.30

Table 1.

Heck cyclization of 10 Using Different Palladium Catalysts

| Reaction Conditions | Oxindole | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | substrate | catalysta | Additiveb | Solvent | T (°C) | t (h) | Yield, %c | 11:12d |

| 1 | 10a | Pd(Ph3P)4 | Et3N | MeCN | 82 | 18 | 81 | 66:34 |

| 2 | 10b | Pd(Ph3P)4 | Et3N | MeCN | 82 | 15 | 66 | 60:40 |

| 3 | 10b | Pd(Ph3P)4 | Et3N | THF | 66 | 24 | 20f | 60:40 |

| 4 | 10b | Pd(dppe)e | Et3N | THF | 66 | 24 | 46f | 55:45 |

| 5 | 10b | Pd(dppf)e | Et3N | THF | 66 | 36 | (18) | 50:50 |

| 6 | 10b | Pd2(dba)3 | Et3N | THF | 66 | 24 | 75f | 73:27 |

| 7 | 10b | Pd2(dba)3 | Et3N | PhMe | 110 | 1 | 80–95g | 89:11 |

| 8 | 10b | Pd2(dba)3 | Ag3PO4 | THF | 66 | 36 | 77 | 3:97 |

10–20% was employed.

10–15 equiv of Et3N or 2 equiv of Ag3PO4 (per equiv of 10) was employed.

Isolated yields of the isomer mixture, yields in parentheses are % conversion by capillary GC analysis (peak area % without calibration).

Capillary GC or 500 MHz 1H NMR analysis; in contrast to the methyl analog, isomers 11b and 12b could not be separated on silica gel.

Prepared in situ from 1 equiv of Pd2(dba)3 and 2 equiv of the diphosphine.

The majority of the remaining mass was recovered 10b

Multiple experiments conducted with 100–300 mg of 10b.

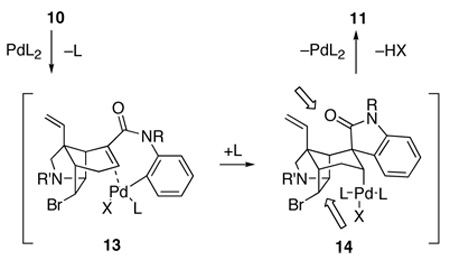

With the aim of reducing the severe steric interactions that exist between the phosphine ligands and the two-carbon bridge of the azatricyclic ring in the presumed precursor of spirooxindole 11, alkylpalladium(II) halide complex 14 (equation 2), we investigated the use of chelating diphosphine ligands. To our surprise, replacing Ph3P with bis(diphenylphosphino)ethane (dppe) in cyclizations of α,β-unsaturated anilide 10b carried out in refluxing THF had little effect on stereoselection (entry 4). Stereoselectivity was also poor when the larger 1,1′-bis(diphenylphosphino)ferrocene (dppf) ligand was employed (entry 5). However, cyclizations of α,β-unsaturated anilide 10b catalyzed by tris(dibenzylideneacetone)dipalladium [Pd2(dba)3] without added phosphine ligands were more selective (entries 6 and 7).31,32,33 Spirooxindoles 11b and 12b were generated in a 9:1 ratio, respectively, and in good yield using 10 mol% of [Pd2(dba)3] as the catalyst in refluxing toluene.

|

(2) |

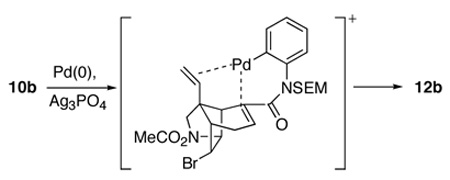

In contrast, Heck cyclization of precursor 10b conducted in the presence of Ag3PO4 without phosphine ligands occurred with virtually complete selectivity to give the epimeric oxindole 12b (entry 8). We attribute the high selectivity (97:3) in this case to coordination of the angular vinyl group during the insertion step (equation 3). Apparently, this coordination is enhanced by the dissociation of the bromide ligand to give a more electrophilic cationic palladium(II) intermediate.9d Consistent with this proposal, Heck cyclization under identical conditions of the analog of α,β-unsaturated anilide 10b in which the angular vinyl group is replaced by an ethyl substituent provided a 1:1 mixture of oxindole diastereomers.9d

|

(3) |

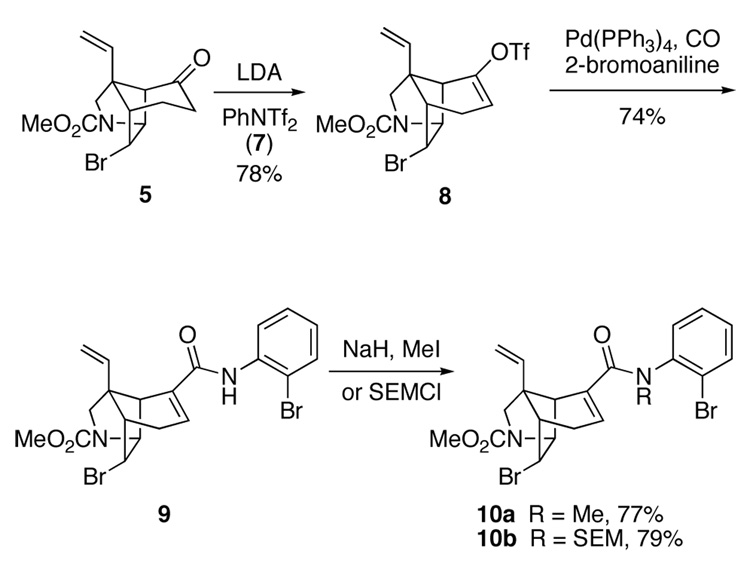

Attempts to Construct the Tetrahydropyran Ring of Gelsemine from Pentacyclic Intermediate 11b

With five of the six rings of gelsemine assembled, what remained was introduction of one carbon and elaboration of the tetrahydropyran ring. Our anticipation that this task would be straightforward turned out to be a remarkably poor assessment. Our initial plan was to displace the bromide substituent of 11b with cyanide anion, convert the resulting endo-oriented nitrile to a primary alcohol and engage this group and the alkene to form the final ring of gelsemine. With this strategy in mind, a 9:1 mixture of pentacyclic oxindoles 11b/12b (formed as described in entry 9 of Table 1) was allowed to react with NaCN in hot dimethylsulfoxide (Scheme 2). To our surprise, this reaction produced aziridines 15/16 in a 9:1 ratio and 85% yield; none of the expected nitrile product was formed. These aziridine epimers could be separated on silica gel, providing the major stereoisomer 15 in 76% yield from the 11b/12b Heck product. Whether this unusual reaction occurs by an SN1 process, a double displacement sequence, or another mechanism has not been determined.

Scheme 2.

The formation of aziridine 15 did not appear to sabotage our plans because the aromatic ring of the oxindole should block backside attack at C5 of this and related intermediates. Thus, we anticipated that nucleophiles would attack an electrophilic aziridinium ion derived from hexacyclic aziridine 15 at the C16 carbon. In practice it was found that reaction of aziridine 15 with methyl trifluoromethanesulfonate at room temperature in CH2Cl2 formed the stable N-methylaziridinium salt 17, which, when exposed to an excess of NaCN in dimethylsulfoxide at 90 °C, produced a single pentacyclic nitrile 18 in 84% yield.

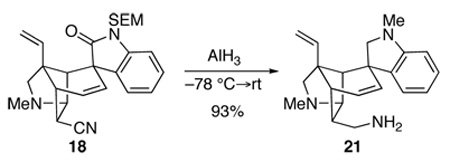

We turned to examine elaboration of the endo-oriented nitrile substituent of pentacyclic intermediate 18 to a hydroxymethyl group. Attempted reduction of the nitrile group of 18 with diisobutylaluminum hydride (DIBALH), sodium bis(2-methoxyethoxy)aluminum hydride (RedAl®), LiAl(OEt)3H, NaBH4 or NaBH4•CoCl2 under a wide variety of reaction conditions resulted either in recovery of starting material or production of unidentifiable products. One exception was the reaction of pentacyclic nitrile 18 with LiAlH4 in Et2O at −78 °C, which delivered indolenine 19 in 80% yield upon aqueous workup (Scheme 2). Further reduction of this product with LiAIH4 in Et2O at −20 °C provided indoline 20. It is remarkable that the endo nitrile group was untouched by LiAIH4 under both conditions. The only reagent that reduced the nitrile group of intermediate 18 cleanly was AlH334 which delivered pentacyclic triamine 21 in 93% yield (equation 4).

|

(4) |

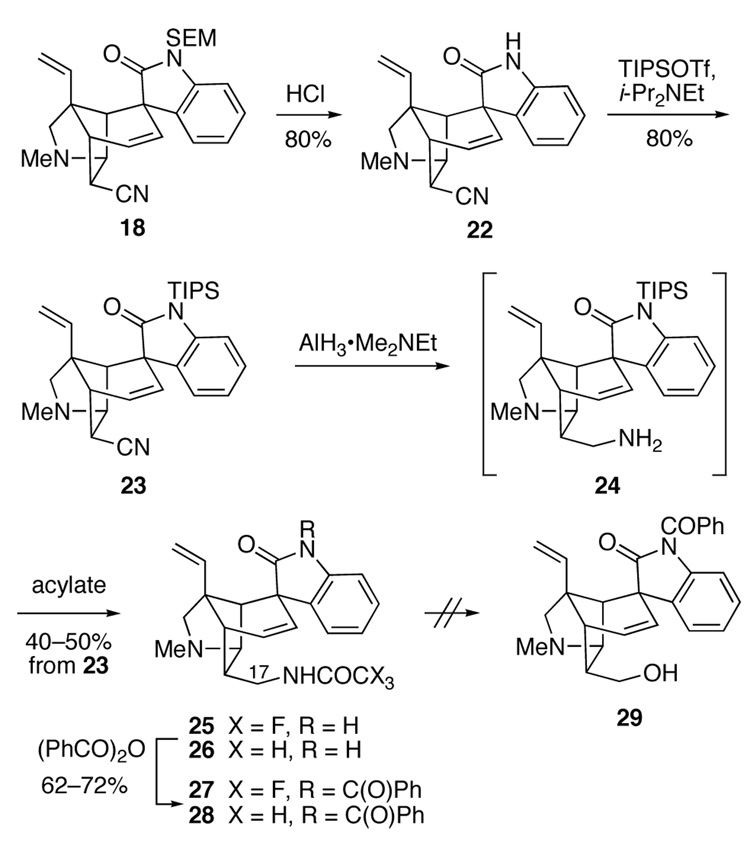

As a primary amine could plausibly serve as a precursor of a primary alcohol,35–37 we explored the use of other oxindole protecting groups in the hopes that the nitrile substituent of a congener of pentacyclic intermediate 18 could be selectively converted to the corresponding primary amine without reduction of the oxindole. To examine this issue, the SEM protecting group of 18 was removed by reaction with 6 M HCl, providing pentacyclic oxindole 22 (Scheme 3). This crystalline product yielded single crystals, allowing its structure and the configuration of the major Heck product to be rigorously established. Reaction of unprotected oxindole 22 with triisopropylsilyl (TIPS) trifluoromethanesulfonate in CH2Cl2 in the presence of diisopropylethylamine cleanly introduced the TIPS group onto the oxindole nitrogen to give intermediate 23 in 80% yield. Subsequent reduction of 23 with AlH3•Me2EtN38 in THF at room temperature generated primary amine 24. As we hoped, the bulky TIPS group had shielded the oxindole carbonyl from reduction.39 This polar intermediate was not purified, but directly acylated with either N-(trifluoroacetoxy)succinimide40 or pentafluorophenyl acetate41 to give trifluoroacetamide 25 or acetamide 26 in 40–50% overall yields from pentacyclic intermediate 23. As the TIPS group had been cleaved during these acylation steps, the oxindole nitrogen was reprotected by reaction of amides 25 and 26 with benzoic anhydride to yield imides 27 and 28.

Scheme 3.

One of the better methods for converting aliphatic primary amines to alcohols involves thermal rearrangement of N-nitrosoamide intermediates. However, all our attempts to convert trifluoroacetamide 27 or acetamide 28 into the corresponding N-nitrosoamide failed. For example, reaction of amides 27 or 28 with NaNO2 in Ac2O-HOAc,35 or with N2O4 in the presence of NaOAc36 or pyridine37 only returned unchanged starting material. Subjecting amide 28 to the more electrophilic reagent NOBF437 under a variety of reaction conditions resulted only in decomposition of this substrate.

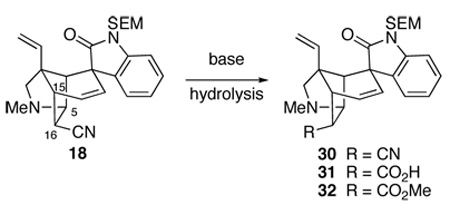

In light of our inability to generate pentacyclic alcohol 29 from an amine precursor, we returned to examine other potentially useful transformations of the nitrile group of pentacyclic intermediate 18. Initially we explored basic hydrolysis. Reaction of 18 with LiOH in refluxing methanol, or NaOH in refluxing ethanol, resulted only in epimerization of the nitrile group of precursor 18 to give mixtures of 18 and its epimer 30 (equation 5).42 Hydrolysis of pentacyclic nitrile 18 under more forcing conditions (5 M KOH in ethylene glycol at 150 °C), followed by treating the crude reaction mixture with diazomethane, provided a single methyl ester product in 63% yield. However, it was readily ascertained that this product was the exo ester 32, most likely resulting from epimerization of the nitrile group prior to hydrolysis. Additionally, treatment of nitrile 18 with basic hydrogen peroxide under phase transfer conditions again yielded an epimerized product, in this case the corresponding primary amide.

|

(5) |

As a last-ditch effort to salvage these intermediates, we explored whether pentacyclic ester 32 could be epimerized by kinetic protonation of its derived enolate.43 Although such a sequence could be realized with a simpler azatricyclo[4.4.0.02,8]decyl ester,44 we never succeeded in accomplishing this epimerization in the pentacyclic series. For example, exposure of ester 32 to excess lithium diisopropylamide (LDA), lithium pyrrolidide, lithium diethylamide, potassium diisopropylamide, potassium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide (KHMDS), lithium hydride or potassium hydride (with or without N,N′-dimethylpropyleneurea, DMPU), followed by quenching with malononitrile failed to produce C16-epi 32.45 In all cases, only the starting ester was obtained. As it was not clear whether deprotonation was taking place, we attempted to prepare the silyl ketene acetal derivative of ester 32. Screening the same set of bases using tert-butyldimethylsilyl chloride as an electrophilic quenching agent also returned only 32, suggesting that the hindered endo proton at C16 was not being removed.

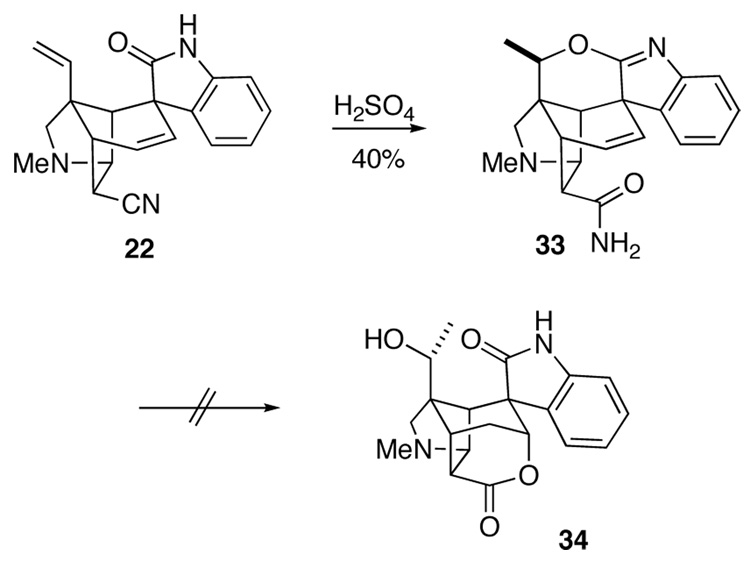

We also examined acidic conditions for elaborating the hindered endo nitrile group of pentacyclic intermediate 22 in the hopes that epimerization at C16 would be less problematic (Scheme 4). Dissolving this precursor in concentrated H2SO4 led, in low yield, to the formation of hexacyclic carboxamide 33, the structure of which was confirmed by X-ray crystallographic analysis. Although the nitrile group had been converted to a carboxamide without epimerization, these strongly acidic conditions had also promoted cyclization of the oxindole onto the C19 terminal vinyl group.46 However, all attempts at promoting the cyclization of the γ,δ -unsaturated carboxamide unit of precursor 33 (or the tetracyclic oxindole derived from 33 upon treatment with aqueous HCl) by reaction with I2,47 PhSeBr,48 Br2,49 Hg(OAc)250 or Hg(OCOCF3)251 were unsuccessful.

Scheme 4.

With these disheartening results in hand, we abandoned attempts to generate the hydropyran ring of gelsemine from a pentacyclic precursor having an endo-oriented C16 nitrile substituent. We returned to aziridinium ion 17 to examine its opening with other one-carbon nucleophiles. Unfortunately, reactions of hexacyclic aziridinium ion 17 with nucleophiles such as (allyldimethylsilyl)methylmagnesium bromide,52 (isopropoxydimethylsilyl)methylmagnesium bromide,53 lithium acetylide, propynyllithium, 1,4-dioxen-2-yl lithium,54 and the Creger–Silbert dianion, LiCH2CO2Li,55 failed to give any identifiable products resulting from ring-opening at C16.

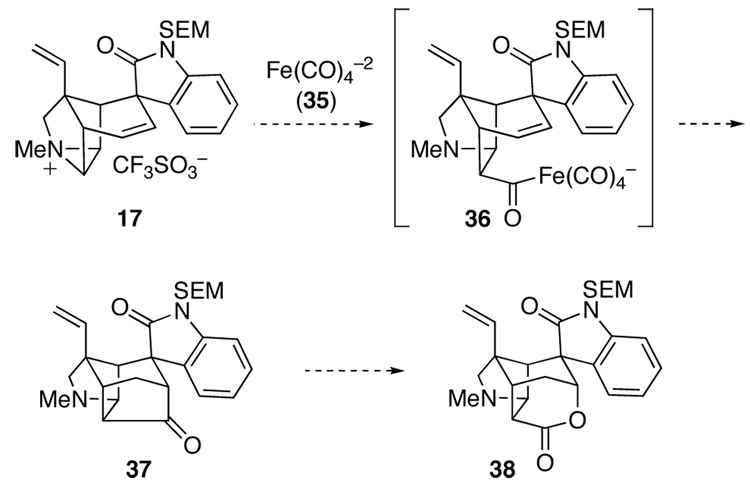

As a final effort to elaborate aziridinium ion 17, we examined its reaction with the potent one-carbon nucleophile, disodium tetracarbonylferrate (35, Collman’s reagent).56 As this reagent reacts with five-and six-carbon unsaturated tosylates and halides to yield cycloalkanones,57,58 the expected product of its union with aziridinium ion 17 was hexacyclic ketone 37 (Scheme 5). We conjectured that Baeyer–Villiger oxidation of this product could lead to lactone 38, which surely would serve as a precursor of gelsemine (1).

Scheme 5.

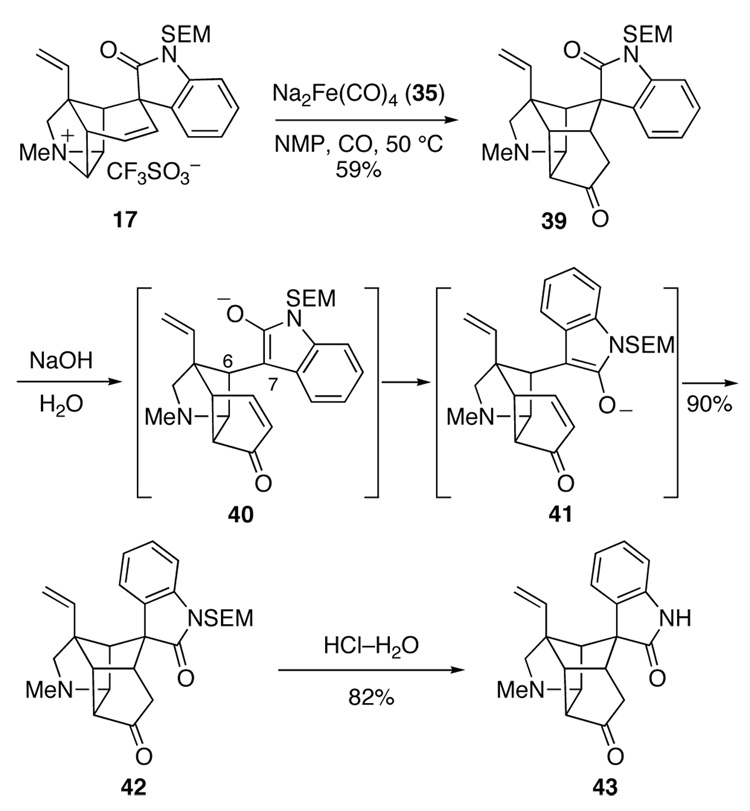

In the event, reaction of hexacyclic aziridinium ion 17 with Collman’s reagent 35 in N-methylpyrrolidinone (NMP) at 50 °C under a CO atmosphere did not yield hexacyclic ketone 37, but instead produced a rearranged product, the isomeric hexacyclic ketone 39, in 59% yield (Scheme 6).9e A possible mechanism for this unexpected and unprecedented reorganization has been suggested.9e Although hexacyclic product 39 was not a useful intermediate en route to gelsemine, it did provide one important insight. Exposure of this material to 1 M NaOH solution in acetone at room temperature caused rapid and complete epimerization at the spiro quaternary center to deliver oxindole epimer 42 in 90% yield. Removal of the SEM protecting group from this product gave hexacyclic oxindole 43, which provided single-crystals suitable for X-ray analysis. Epimerization of the 1,5-dicarbonyl compound 39 likely occurs by retro-Michael fragmentation to generate oxindole enolate 40, rotation about the C6–C7, and Michael ring closure of rotamer 41 to provide epimer 42. The driving force for this epimerization is undoubtedly relief of steric interactions between the aromatic ring of the oxindole and the underside of the cup-shaped azatetracyclic moiety of 39. Base-promoted epimerization of an oxindole intermediate turned out to play an important role in our ultimately successful route to gelsemine (vide infra).59

Scheme 6.

Attempts to Elaborate the Tetrahydropyran Ring Prior to Forming the Spirooxindole

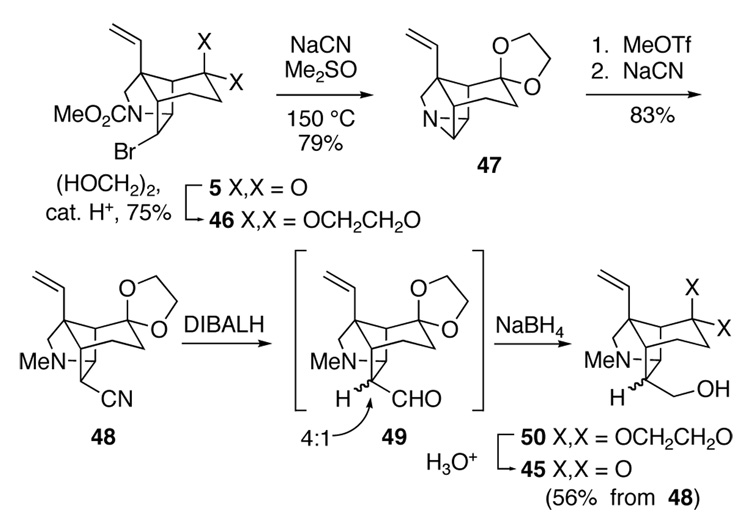

Up to this point, our strategy had been to elaborate a hydroxymethyl group at C16 after the spirooxindole was in place (B → 44, Figure 2). This timing of events had been chosen because we anticipated that the presence of an endo substituent at C16 would compromise the stereoselectivity of the intramolecular Heck reaction by shielding the lower face of the cycloalkene. Much to our surprise, in 1994 Speckamp and co-workers18 reported just such an intramolecular Heck reaction that proceeded with modest stereoselectivity to form the desired spirooxindole using the Pd2(dba)3 conditions we had introduced.9d This disclosure prompted us to investigate installation of the C17 hydroxymethyl group prior to Heck cyclization. We anticipated that the absence of the endo-oriented aryl ring of the oxindole might simplify elaboration of the nitrile to a hydroxymethyl group. Therefore, intermediate 45 became our next sub goal.

Figure 2.

Potential alternate strategy in which spirooxindole formation is accomplished after elaboration at C16.

The preparation of tricyclic ketone 45 is summarized in Scheme 7. Ketone 5 was readily elaborated to nitrile 48 by way of tetracyclic aziridine 47.60 Initial survey experiments showed that reduction of nitrile 48 with diisobutylaluminum hydride (DIBALH) was facile, even at −78 °C. However, hydrolysis of the resulting dialkylaluminum imine was not straightforward, with many standard conditions promoting extensive epimerization of the initially generated endo formyl group. Best results were obtained using aqueous acetic acid. After careful basification, amino aldehyde 49 was obtained as a 4:1 mixture of formyl epimers favoring the desired endo isomer. Reduction of this crude product with NaBH4 and cleavage of the dioxolane group of product 50 gave tricyclic ketone 45 in 56% overall yield from nitrile 48. However, this sequence, particularly the nitrile reduction step, could not be accomplished successfully on anything larger than exploratory scales. This unsatisfactory outcome forced us to abandon this approach.

Scheme 7.

The Final Successful Route to (±)-Gelsemine

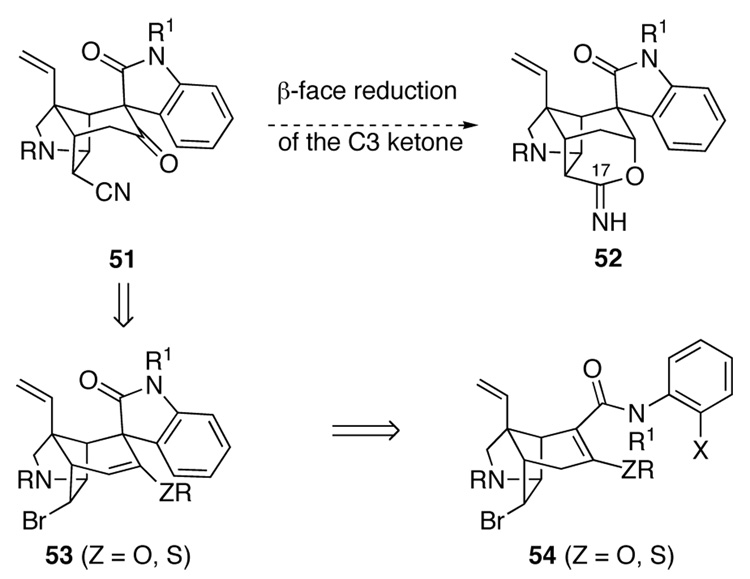

Up to this point, most of the strategies we had investigated for forming the oxacyclic ring of gelsemine envisaged elaboration of pentacyclic nitrile 2 to intermediates that would allow the hydropyran ring to be constructed by forming the C3–O bond (Figure 1). Two factors, both arising from the sterically congested environment of C17 of the gelsemine ring system, had thwarted these efforts: facile epimerization at C16 when C17 is an electron-withdrawing substituent, and the difficulty in accomplishing common functional-group interconversions at C17 in pentacyclic intermediates. We turned to an alternate strategy that would side step these problems by constructing the tetrahydropyran ring of gelsemine by forming the O–C17 bond. Such an approach could allow the critical functionalization of the hindered endo nitrile to be accomplished in intramolecular fashion as suggested in Figure 3 (51 → 52). An attraction of this strategy was the expected ease of reduction of the C3 carbonyl group of intermediates such as pentacyclic keto nitrile 51 as the reductant could approach from the less-encumbered convex β-face. We entertained the possibility of accessing 51 from pentacyclic enol ethers such as 53, which might be available from Heck cyclization of α, β-unsaturated anilide 54 having a heteroatom substituent at C3. A pivotal issue would be whether or not the tetrasubstituted double bond of 54 would participate in an intramolecular Heck reaction. Heck insertions of tetrasubstituted double bonds are rare, and none had been described for a substrate approaching the complexity of 54.26 Moreover, the double bond of 54 might be a particularly poor ligand because it is part of a delocalized vinylogous carbamate or thiocarbamate.

Figure 3.

Revised plan for elaborating the hydropyran ring.

As preliminary scouting experiments had shown that installing an alkoxy group into the α-position of ketone 5 would be difficult, we examined initially this revised plan in the sulfur series (Scheme 8). After failing to cleanly mono-sulfenylate enolate derivatives of 5, we developed a novel route to enol triflate intermediate 56. Tricyclic ketone 5 was initially converted to α,α-dithio derivative 55 by reaction with an excess of potassium hexamethyldisilazide (KHMDS) and methyl methanethiosulfonate. This intermediate was then desulfenylated by reaction with sodium methylmercaptide in THF, and the resulting sodium enolate was trapped with N-phenyltriflimide to give enol triflate 56. Palladium-catalyzed carbonylation of 56 in methanol27 then provided vinylogous thiocarbonate 57. As in other Heck reactions investigated in our laboratories, the presence of the β-sulfur substituent did not have a deleterious effect on this palladium-catalyzed reaction.61 Weinreb aminolysis of ester 5762Error! Bookmark not defined. and protection of the resulting secondary amide with a SEM group generated the highly functionalized Heck cyclization substrate 58 in 30% overall yield from azatricyclic ketone 5.

Scheme 8.

We next examined the propensity of β-methylthio α,β-unsaturated anilide 58 to undergo intramolecular Heck reaction. Cyclization conditions such as those listed in Table 1 that succeed with analogous substituents lacking a β-substituent failed to promote the cyclization of 58. However, the desired intramolecular Heck reaction was accomplished successfully under forcing conditions (150 °C) using (Ph3P)4Pd as the catalyst to give a 1:2 mixture of stereoisomeric tetracyclic products 59 and 60 in a combined yield of 69%. Configurational assignments for these adducts followed from diagnostic signals for the C19 vinyl hydrogens in 1H NMR spectra.30 Attempts to improve the diastereoselectivity of this reaction by using Pd2(dba)3 as the catalyst in the absence of phosphine ligands resulted in no reaction even at 150 °C. At this high temperature, the fine suspension of palladium that is originally present coagulates, a factor that is likely responsible for the unreactivity of substrate 58 under these conditions.

Extensive studies to optimize the Heck cyclization of unsaturated anilide 58 were not carried out because we soon discovered that cleavage of the vinyl sulfide functionality of these adducts would not be straightforward. Preliminary calibration experiments in which 59 was subjected to standard conditions for cleaving a vinylsulfide, for example Hg(OCOCF3)2–aqueous trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) or TFA alone in several different solvents, resulted in either decomposition or cleavage of the SEM group.63 Because of these difficulties, we turned to examine the related sequence in the oxygen series.

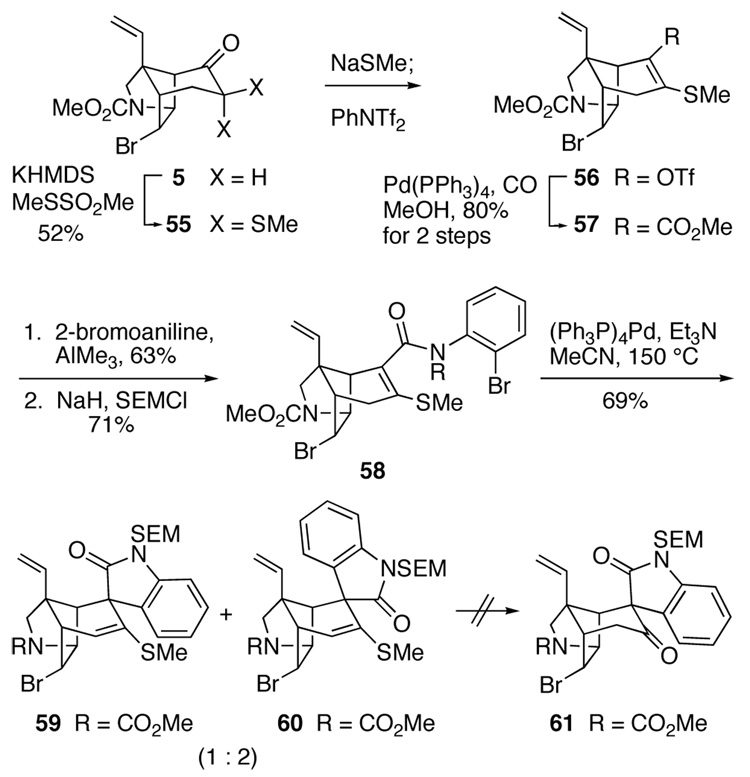

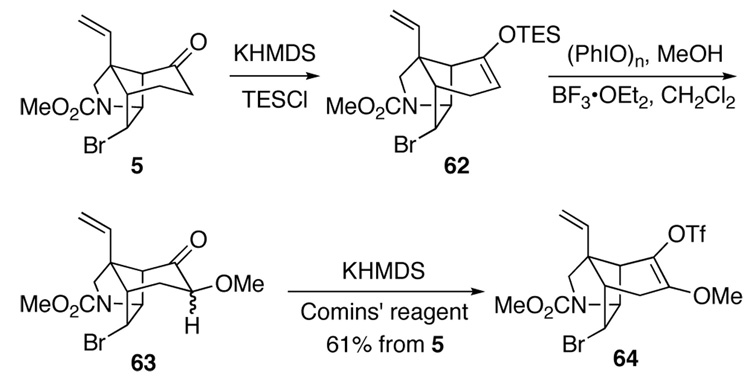

As alluded to earlier, introduction of an alkoxy group into the α position of ketone 5 proved to be extremely challenging (Scheme 9). Enolization of 5 with KHMDS or LDA, followed by quenching the derived enolate with Davis’ oxaziridine64 returned starting material. Likewise, enolization with LDA followed by attempted oxidation with dimethyldioxirane,65 MoO5·pyridine·HMPA66 or LiOOt-Bu67 returned starting material, as did the reaction of ketone 5 with potassium tert-butoxide, molecular oxygen and triethyl phosphite.68 Treatment of ketone 5 with potassium hydroxide and 2-iodosobenzoic acid or iodosobenzene diacetate69 led to unidentifiable products, as did attempted oxidation of 5 with N-chlorosuccinimide. 70 Our attempts to oxidize the enoxytriethylsilane derivative 62 (or trimethyl-, or tert-butyldimethylsilyl analogs) with m-chloroperbenzoic acid (m-CPBA),71 peracetic acid buffered with sodium carbonate, dimethyldioxirane or osmium tetroxide also did not generate the desired α-siloxyketone. We finally discovered that addition of a CH2Cl2 solution of crude enoxytriethylsilane 62 to a solution of iodosobenzene and boron trifluoride etherate in methanol at −78 °C and then allowing the temperature to rise to 0 °C72 produced α-methoxy ketone 63 in useful yield. Although attempted purification of this product on silica gel led to its decomposition, a singlet at δ 3.4 ppm in the 1H NMR spectrum of this crude product left little doubt that a methoxy group had been incorporated. When crude 63 was treated with KHMDS at −78 °C in THF, and the resulting enolate was quenched with 2-[N,N-bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)amino-5-chloropyridine (Comins' reagent),73 β-methoxy triflate 64 was formed in 61% overall yield from ketone 5.74

Scheme 9.

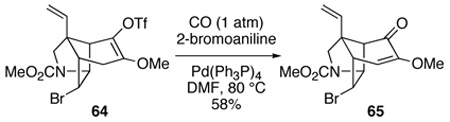

To our initial surprise, reaction of 64 with 2–bromoaniline under an atmosphere of carbon monoxide and a catalytic amount of tetrakis(triphenylphosphine)palladium(0) in DMF at 80 °C gave rise to none of the desired anilide, but instead provided α-methoxy enone 65 in 58% (equation 6). This unusual oxidation, which we have shown to be general for enol triflates having alkoxy or thioalkoxy β-substituents, likely involves solvolysis of the β-methoxy vinyl triflate with loss of trifluoromethanesulfinic acid.75

|

(6) |

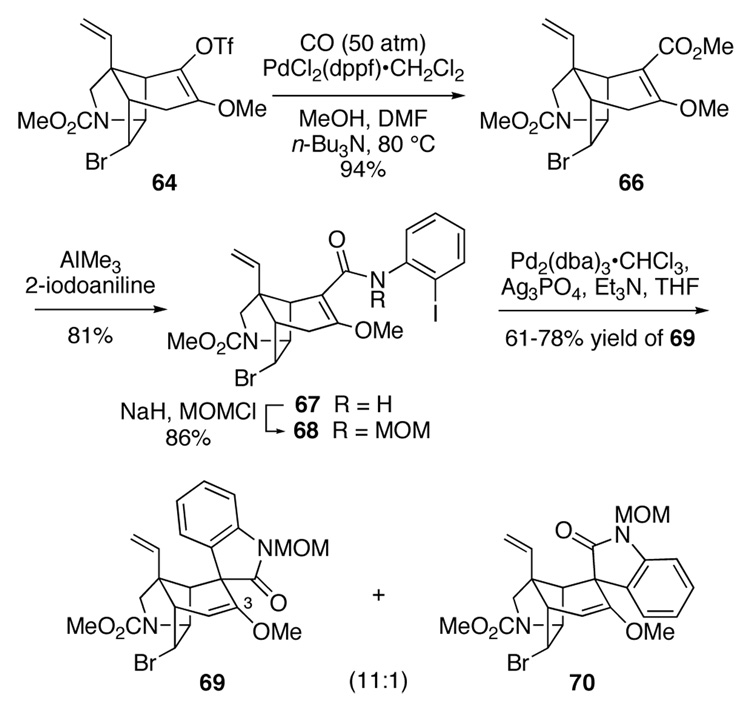

Fortunately, this side reaction could be prevented by carrying out the carbonylation at 80 °C using bis(diphenylphospine)ferrocenylpalladium(II) chloride as the catalyst in DMF-methanol (1:2) under 1 atmosphere of carbon monoxide (Scheme 10). Under these conditions, the crystalline vinylogous carbonate 66 was produced in 94% yield; the structure of this intermediate was confirmed by single-crystal X-ray analysis. Subsequent reaction of vinylogous carbonate 66 with the dimethylaluminum amide of 2-iodoaniline62 in CH2Cl2 at 0 °C and slowly letting the reaction warm to room temperature over a period of 2 hours delivered iodoanilide 67 in 81% yield. It was essential that this reaction be initiated below room temperature, otherwise a significant amount of the vinylogous urea resulting from 1,4 addition of the aluminum amide to 67 was observed as a by-product. Finally protection of the secondary amide with a methoxymethyl (MOM) group provided β-methoxy α,β-unsaturated anilide 68 in 86% yield.

Scheme 10.

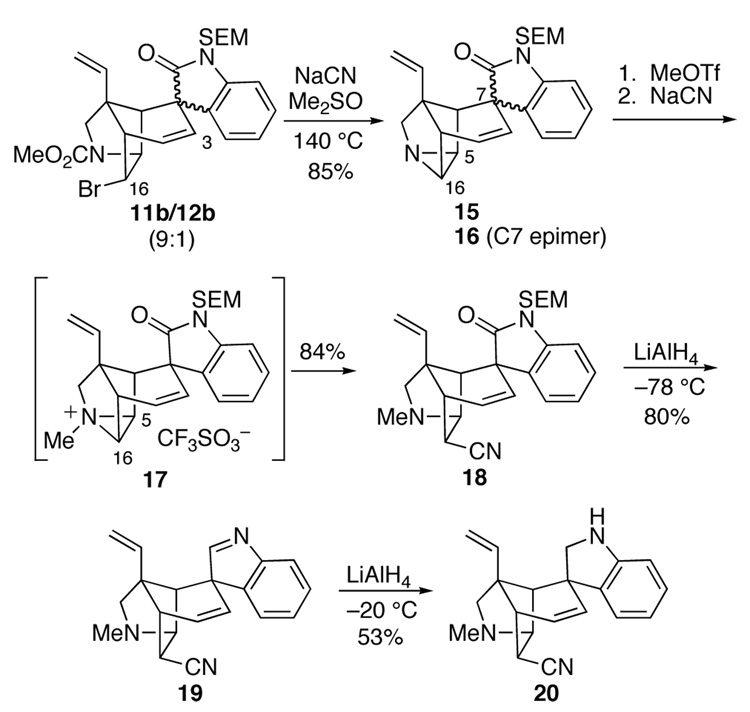

The intramolecular Heck reaction of β-methoxy unsaturated anilide 68 was investigated in detail. We quickly found that Heck cyclization of this intermediate could be accomplished under milder conditions than those required to cyclize the β-methylthio analog 58. For example, reaction of β-methoxy precursor 68 with 20 mol% Pd2(dba)3 at 110 °C in the absence of phosphine ligands (conditions of Table 1, entry 9) provided pentacyclic products 69 and 70 in a 5:1 ratio and 60% yield.30 As was observed in the sulfur series, these conditions favored the formation of the product having the unnatural configuration of the spirooxindole; these results stand in marked contrast to what was observed in the cyclization of the simpler congener having hydrogen as the β substituent (see Table 1).76 Despite considerable effort, we were never able to find Heck cyclization conditions that provided useful amounts of the natural isomer 70. However, the unnatural isomer 69 could be produced in high yields by carrying out the Heck cyclization of 68 in the presence of silver salts. Under optimal conditions, β-methoxy α,β-unsaturated anilide 68 was converted to Heck product 69 in yields ranging from 61–78% using 35 mol% Pd2(dba)3 and 2 equivalents of Ag3PO4 in refluxing THF. The high preference for forming pentacyclic product 69 having the aryl fragment of the oxindole cis to the angular vinyl group presumably arises from coordination of palladium with this latter group (equation 3).9d

To prepare gelsemine from pentacyclic Heck product 69, we needed to invert the configuration of the oxindole as well as fashion the tetrahydropyran ring. Although prospects for the former would have appeared poor at the outset of our investigations, our experience in inverting the spirocyclic oxindole of pentacyclic ketone 39 (Scheme 6), and the significant development of an epimerization strategy by Hart and co-workers,19b suggested that epimerization of the spirooxindole should be possible if the enol ether functionality of pentacyclic Heck product 69 could be converted to a C3 ketone or alcohol.

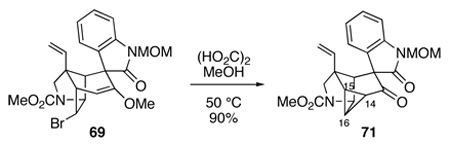

Another example of the unique reactivity engendered by the compact cage structure of gelsemine confronted us when we attempted to hydrolyze pentacyclic enol ether 69 with oxalic acid in MeOH–H2O at 50 °C or 1 M HCl in acetone at 55 °C. These conditions provided the structurally remarkable hexacyclic cyclopropyl ketone 71 in high yield (equation 7). The structural assignment for 71 followed from its mass spectrum, where the parent peak at 394 amu corresponded to loss of HBr from the expected pentacyclic ketone. The 13C NMR spectrum of cyclopropyl ketone 71 could be fully assigned by an HMQC experiment, showing a carbonyl carbon at 201.6 ppm and signals for C14, C15 and C16 at 24.1, 24.5 and 28.1 ppm, respectively. Of most significance, these cyclopropane carbons had diagnostic C–H coupling constants in the range of 166–180 Hz.77

|

(7) |

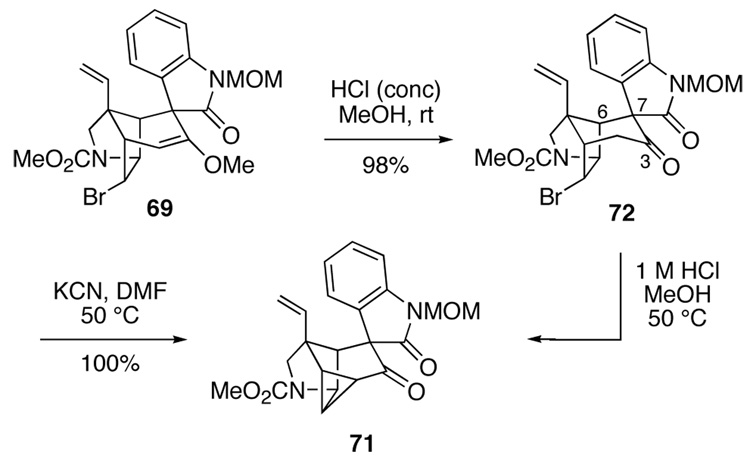

Fortunately, cyclopropane formation could be avoided by carrying out the hydrolysis of enol ether 69 at room temperature using a 1:2 mixture of concentrated HCl and methanol (Scheme 11). In this way, tetracyclic ketone 72 was obtained in 98% yield, with its structure being confirmed by X-ray crystallographic analysis. In light of our earlier results, it was not surprising to find that product 72 lost HBr when heated at 50 °C in 1 M HCl in methanol, presumably via its enol, to form cyclopropyl ketone 71.

Scheme 11.

We were now poised to investigate epimerization of the spirooxindole. Hart had shown that a pentacyclic ketone somewhat analogous to intermediate 72 having a carbonyl group at C3 and the unnatural oxindole stereochemistry undewent epimerization at C7 upon treatment with potassium cyanide.19b The mechanism proposed for this oxindole inversion involves initial formation of the C3 cyanohydrin, retro-aldolization to break the C3–C7 bond, rotation about the C6–C7 σ bond, and acylation to regenerate the C3–C7 bond. However in our case, treating ketone 72 with a catalytic amount of KCN in DMF at 50 °C resulted only in forming hexacyclic cyclopropyl ketone 71. Attempts to form the cyanohydrin derivative of 72 under non-basic conditions by reaction with trimethylsilyl cyanide in the presence of zinc iodide78 also led to hexacyclic product 71, whereas attempted reaction of ketone 72 with diethylaluminum cyanide79 (−30 °C → room temperature in THF) returned starting material.

Influenced by Hart's demonstration that the spirooxindole of a pentacyclic gelsemine precursor having a hydroxyl group at C3 could be inverted by a retro-aldol/aldol process,19b we examined the reduction of pentacyclic ketone 72 (Scheme 12). Reaction of this ketone with sodium borohydride and cerium(III) chloride heptahydrate (Luche conditions)80 in methanol at −10 °C gave a 3:1 ratio of readily separable alcohol epimers 73 and 74 in 85% combined yield. The selectivity of this transformation could be reversed using triisobutylaluminum as the reductant (−50 °C → room temperature in toluene).81 These latter conditions provided a 6.5:1 mixture of alcohol epimers with equatorial epimer 74 predominating; after chromatography on silica gel, pentacyclic equatorial alcohol 74 was isolated in 71% yield.

Scheme 12.

We were once again at a stage to examine the critical epimerization of the spirooxindole fragment. When pentacyclic alcohol 73 or 74 was exposed to 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene (DBU) in CH2Cl2 at room temperature,19b epimerization of the oxindole was not realized, but instead the two alcohol epimers were equilibrated (Scheme 12). However, when this mixture of alcohol epimers was heated with DBU at 110 °C in toluene for 4 h, hexacyclic furan 75 was isolated in 57% yield. No trace of the corresponding product having an epimeric oxindole fragment was seen. The stereostructure of 75 followed unambiguously from diagnostic NOE's between the methine hydrogens at C5 and C9. Epimerization of the oxindole, presumably by a retro-aldol fragmentation/aldol condensation sequence, obviously had taken place prior to cyclization of the axial alcohol epimer to form 75. Why 73 does not undergo similar intramolecular etherification to form the spirooxindole epimer of 75 is less clear. Perhaps the cyclohexyl ring of 73 adopts a boat conformation to minimize steric interaction between the aromatic ring of the oxindole and the neighboring ethenyl group.82 If so, the C3 hydroxyl group would no longer be positioned appropriately to displace the bromide.

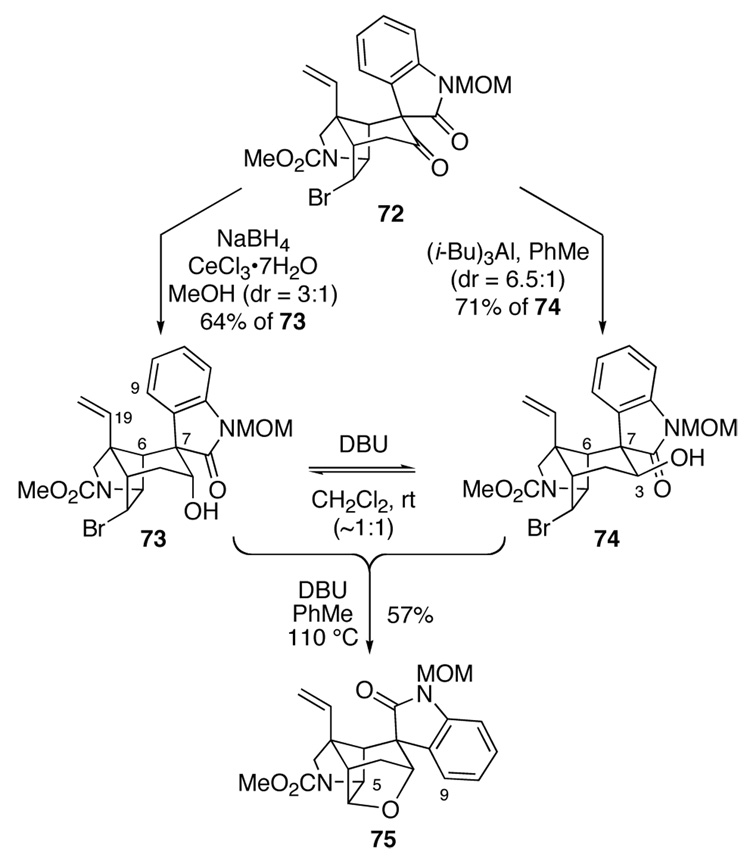

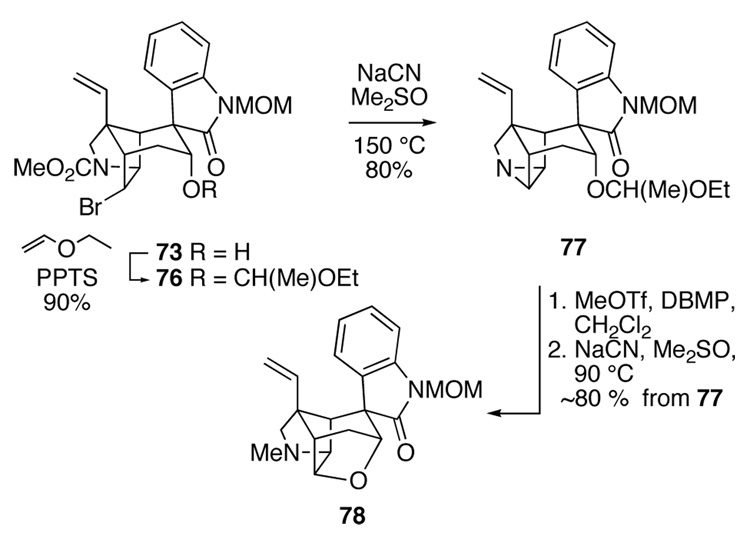

The results summarized in Scheme 12 demonstrated that the nitrile needed to be introduced at C16 prior to attempting epimerization of the spirooxindole. We initially explored this possibility with intermediate 73 after first masking the axial alcohol as an ethoxyethyl ether (Scheme 13). Reaction of this product, 76, with NaCN in dimethylsulfoxide at 150 °C gave rise to hexacyclic aziridine 77 in 80% yield. Conversion of this product to the corresponding methyl aziridinium ion, and reaction of this salt with NaCN at 90 °C produced hexacyclic furan 78 in high yield. Evidently the methyl aziridinium ion reacts more rapidly with the proximal oxygen of the axial acetal substituent than with external cyanide. This result directed us to the ultimately successful solution: employ equatorial alcohol epimer 74 to introduce C19.

Scheme 13.

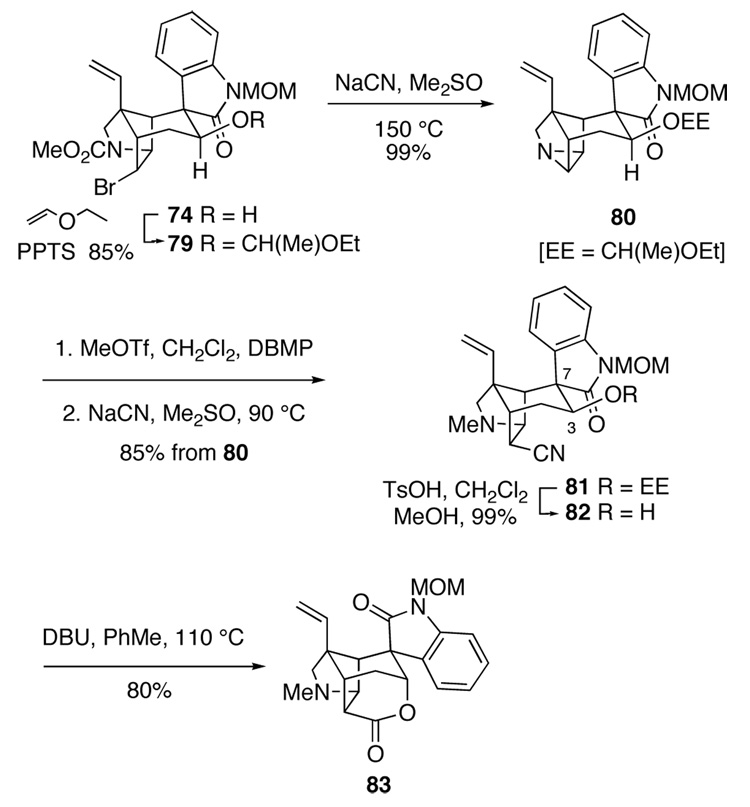

This final sequence began with protection of the equatorial hydroxyl group of pentacyclic intermediate 74 by reaction with pyridinium p-toluenesulfonate and ethyl vinyl ether in CH2Cl2 to give 79 (Scheme 14). Reaction of this product with NaCN in the usual way provided aziridine 80 in nearly quantitative yield. Activation of 80 by reaction with methyl trifluoromethanesulfonate in the presence of 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methylpyridine (DBMP) and opening the resulting methyl aziridinium ion with NaCN delivered nitrile 81 in 85% overall yield from hexacyclic aziridine 80. When the aziridine was activated in the absence of DBMP, the 1-ethoxyethyl group was cleaved prematurely giving hexacyclic tetrahydrofuran 78 as the major product. After removing the 1-ethoxyethyl group of acetal 81 under standard acidic conditions, pentacyclic nitrile 82 was isolated in 71% overall yield from equatorial alcohol 74.

Scheme 14.

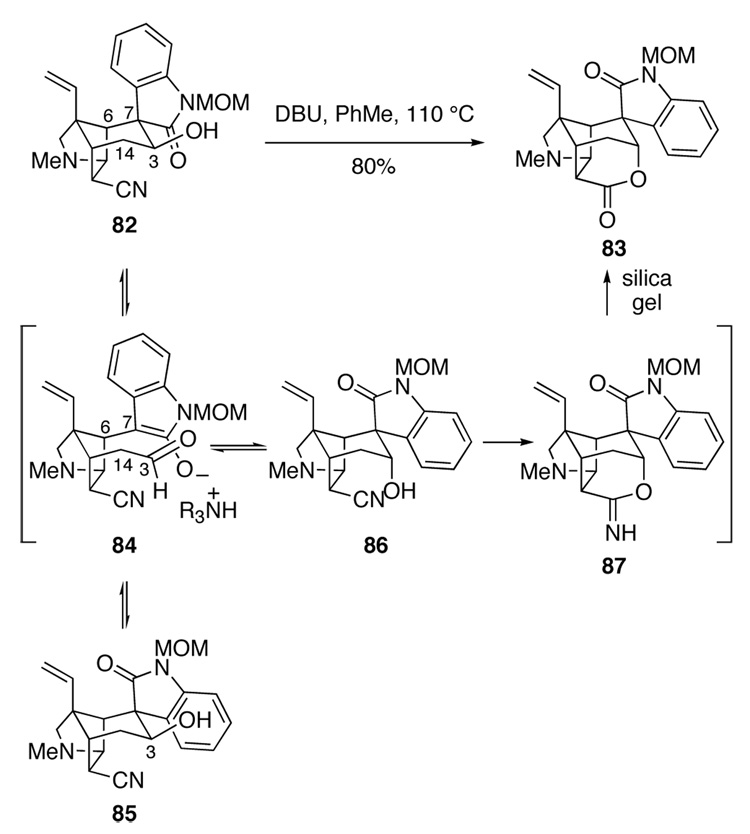

Three critical conversions remained in order to elaborate hydroxy nitrile 82 to gelsemine: epimerization of the spirooxindole stereocenter C7, epimerization of the C3 alcohol, and intramolecular condensation of the C3 axial alcohol with the endo cyanide. To our delight, we quickly found that all three conversions could be realized by simply heating hydroxy nitrile 82 with DBU in toluene at 110 °C (Scheme 14). After silica gel chromatography, hexacyclic lactone 83 was isolated in 80% yield. A likely mechanism for this multi-faceted conversion is suggested in Scheme 15. Retro-aldol cleavage of 82 would generate oxindole enolate 84. Rotation about the C6–C7 σ bond and re-aldolization would form spirooxindole epimer 85, whereas alcohol epimer 86 would be produced by addition of the oxindole enolate to the other prochiral face of the aldehyde. Finally, addition of the axial hydroxyl group of intermediate 86 to the proximal nitrile would generate cyclic imidate 87. Hydrolysis of this product upon purification on silica gel would give the observed product 83. Although intermediate 86 was not detected, its equatorial epimer 85 could be isolated when the reaction was stopped prior to completion.

Scheme 15.

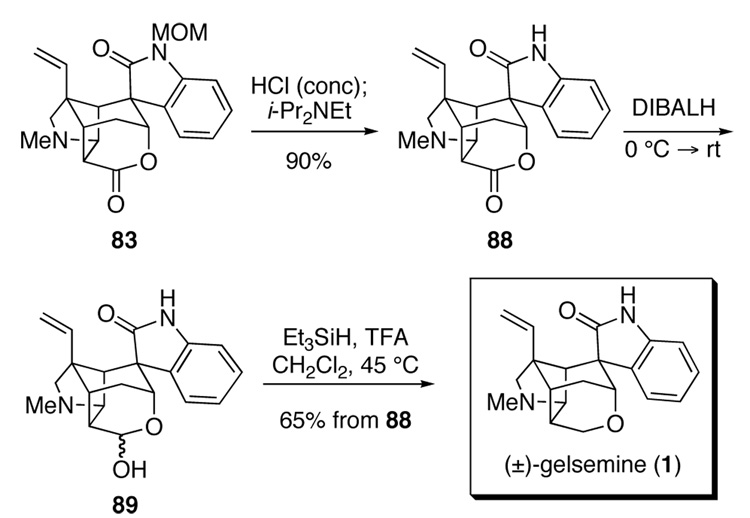

The conversion of hexacyclic lactone 83 to gelsemine (1) was straightforward (Scheme 16). The methoxymethyl group of 83 was first discharged by reaction with concentrated HCl in ethylene glycol dimethyl ether (DME) at 55 °C to give the corresponding N-hydroxymethyl oxindole; exposure of this intermediate to N,N-diisopropylethylamine in methanol at 55 °C furnished oxindole lactone 88 in 90% yield. Reduction of this intermediate with excess diisobutylaluminum hydride generated a mixture of lactols 89, which upon reaction with triethylsilane in trifluoroacetic acid83 produced (±)–gelsemine (1) in 65% yield from hexacyclic lactone 88. The 1H and 13C NMR and IR spectra, and mass spectral fragmentation patterns of 1 were identical to those of an authentic sample of natural gelsemine.

Scheme 16.

Conclusion

Structurally unique natural products have long served to benchmark the existing tools of organic synthesis and stimulate the development of new reagents, reactions and synthetic strategies. As gelsemine has no commercial or medicinal value, it was the opportunity to discover and develop new synthetic chemistry that led us to tackle its total synthesis. Discoveries of new chemistry and new modes of reactivity made during our studies, and those of other laboratories working in the area, have broad implications for organic chemistry that transcend the accomplishment of a gelsemine total synthesis.3f

The extraordinary ability of intramolecular Heck reactions to construct highly congested quaternary carbon centers is a discovery of fundamental importance made during our efforts in the gelsemine area. At the time we first reported in 1988 that palladium-catalyzed insertions could succeed even in the face of numerous developing syn-pentane (1,3-diaxial) interactions,9c Heck reactions were rarely used for ring formation, and never as the key strategic step in the synthesis of complex organic molecules. Today, intramolecular Heck reactions are established as one of the synthetic chemist's most powerful tools for forming C-C bonds in complex, polyfunctional molecules.25

This research program also uncovered unique, unexpected reactivity associated with the enforced functional-group proximity engendered by the cage-like gelsemine ring system. Notable examples are: (1) the formation of aziridines from the reaction of N-methoxycarbonyl-β-bromoethylamines with cyanide by formal front-side displacement, (2) the unprecedented rearrangement of an alkyl iron intermediate,9e (3) the acid-promoted cyclizations of γ-bromoketones to cyclopropyl ketones, and (4) the base-promoted reaction cascade summarized in Scheme 15. Our studies in the gelsemine area revealed also the thermal instability of β-alkoxy enol triflates, providing a caveat to their use in transition metal catalyzed chemistry and foreshadowing our development of a new synthesis of α-thioalkoxy enones.75 As summarized in some detail in the accompanying paper,24 our gelsemine studies also provided greater understanding of the scope and limitations of aza-Cope–Mannich transformations.24

As for our total synthesis of (±)-gelsemine (1), it was accomplished in 1.1% overall yield from 3-methylanisole by the way of 26 isolated intermediates.84 It is among the most efficient total syntheses of racemic gelsemine reported to date,85,86 although it is longer than the Speckamp–Hiemstra synthesis, which proceeded in 23 steps from sorbic acid.18 Despite extensive synthetic work in the gelsemine area over nearly two decades, a short synthesis of gelsemine has yet to emerge.

Supplementary Material

Experimental procedures, spectroscopic and analytical data for new compounds, 1H NMR spectra of selected compounds, and 1H and 13C NMR spectra of synthetic (±)-gelsemine and natural gelsemine (79 pages). This material is free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health (HL–25854). C.J.O. gratefully acknowledges the American Cancer Society for postdoctoral fellowship support (PF-98-002-01). We also thank Dr. John Greaves and Mr. John Mudd of the UCI mass spectroscopy facility, Dr. Joeseph Ziller of the UCI X–ray crystallography laboratory and Dr. Jiejun Wu of the UCI NMR spectroscopy facility for their technical support.

References

- 1.Current addresses: (a) Merck, Sharp & Dohme Laboratories, Terlings Park, Harlow, Essex CM20 2QR, England. (b) Pfizer Inc., Groton/New London Laboratories, Eastern Point Road, 8220-4044, Groton, CT 06340. (c) California State University Northridge, Department of Chemistry, Northridge, CA 91330. (d) Allergan Inc., 2525 DuPont Drive, RD 3D, Irvine, CA 92623. (e) GlaxoSmithKline, 5 Moore Dr., Research Triangle Park, NC 27709.

- 2.(a) Lovell FM, Pepinsky R, Wilson AJC. Tetrahedron Lett. 1959;1(4):1–5. [Google Scholar]; (b) Conroy H, Chakrabarti JK. Tetrahedron Lett. 1959;1(4):6–13. [Google Scholar]

- 3.For general reviews of Gelsemium alkaloids, see: Saxton JE. In: The Alkaloids. Manske RHF, editor. Vol. 8. NY: Academic Press; 1965. pp. 93–117.Bindra JS. In: The Alkaloids. Manske RHF, editor. Vol. 14. NY: Academic Press; 1973. pp. 83–121.Liu Z-J, Lu R-R. In: ibid. Brossi A, editor. Vol.33. San Diego: Academic Press; 1988. pp. 83–140.Saxton JE. Nat. Prod. Rep. 1992;9:393–446.Takayama H, Sakai S-J. In: The Alkaloids. Cordell GA, editor. Vol. 49. NY: Academic Press; 1997. pp. 1–78.For a review of synthetic work in this area, see: Lin H, Danishefsky SJ. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2003;42:36–51. doi: 10.1002/anie.200390048.

- 4.(a) Autrey RL, Tahk FC. Tetrahedron. 1967;23:901–917. [Google Scholar]; (b) Autrey RL, Tahk FC. Tetrahedron. 1968;24:3337–3345. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson RS, Lovett TO, Stevens TS. J. Chem. Soc. C-Organic. 1970;6:796–800. [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Fleming I, Michael JP. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1981;1:1549–1556. [Google Scholar]; (b) Fleming I, Loreto MA, Michael JP, Wallace IHM. Tetrahedron Lett. 1982;23:2053–2056. [Google Scholar]; (c) Fleming I, Loreto MA, Wallace IHM, Michael JP. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1986;1:349–359. [Google Scholar]; (d) Clarke C, Fleming I, Fortunak JMD, Gallagher PT, Honan MC, Mann A, Nubling CO, Raithby PR, Wolff JJ. Tetrahedron. 1988;44:3931–3934. [Google Scholar]; (e) Fleming I, Moses RC, Tercel M, Ziv J. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1991;1:617–626. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stork G, Krafft ME, Biller SA. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987;28:1035–1038. [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Vijn RJ, Hiemstra H, Kok JJ, Knotter M, Speckamp WN. Tetrahedron. 1987;43:5019–5030. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hiemstra H, Vijn RJ, Speckamp WN. J. Org. Chem. 1988;53:3882–3884. [Google Scholar]; (c) Koot W-J, Hiemstra H, Speckamp WN. J. Org. Chem. 1992;57:1059–1061. [Google Scholar]; (d) Dijkink J, Cintrat JC, Speckamp WN, Hiemstra H. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:5919–5922. [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Abelman MM, Oh T, Overman LE. J. Org. Chem. 1987;52:4130–4133. [Google Scholar]; (b) Earley WG, Jacobsen EJ, Meier GP, Oh T, Overman LE. Tetrahedron Lett. 1988;29:3781–3784. [Google Scholar]; (c) Earley WG, Oh T, Overman LE. Tetrahedron Lett. 1988;29:3785–3788. [Google Scholar]; (d) Madin A, Overman LE. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:4859–4862. [Google Scholar]; (e) Overman LE, Sharp MJ. J. Org. Chem. 1992;57:1035–1038. [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Choi J-K, Ha D-C, Hart DJ, Lee C-S, Ramesh S, Wu S. J. Org. Chem. 1989;54:279–290. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hart DJ, Wu SC. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32:4099–4102. [Google Scholar]; (c) Hart DJ, Wu SC. Heterocycles. 1993;35:135–138. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takayama H, Seki N, Kitajima M, Aimi N, Sakai S-I. Nat. Prod. Lett. 1993;2:271–276. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson AP, Luke RWA, Steele RW, Boa AN. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1996;1:883–893. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ng F, Chiu P, Danishefsky SJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:767–770. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sung MJ, Lee C-W, Cha JK. Synlett. 1999:561–562. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Avent AG, Byrne PW, Penkett CS. Org. Lett. 1999;1:2073–2075. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pearson AJ, Wang X. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:13326–13327. doi: 10.1021/ja030407e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Sheikh Z, Steel R, Tasker AS, Johnson AP. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1994:763–764. [Google Scholar]; (b) Dutton JK, Steel RW, Tasker AS, Popsavin V, Johnson AP. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1994:765–766. [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Newcombe NJ, Ya F, Vijn RJ, Hiemstra H, Speckamp WN. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1994:767–768. [Google Scholar]; (b) Speckamp WN, Newcombe NJ, Hiemstra H, Ya F, Vijn RJ, Koot W-J. Pure Appl. Chem. 1994;66:2163–2166. [Google Scholar]

- 19.(a) Kuzmich D, Wu SC, Ha D-C, Lee C-S, Ramesh S, Atarashi S, Choi J-K, Hart DJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:6943–6944. [Google Scholar]; (b) Atarashi S, Choi J-K, Ha D-C, Hart DJ, Kuzmich D, Lee C-S, Ramesh S, Wu SC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:6226–6241. [Google Scholar]

- 20.(a) Fukuyama T, Liu G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:7426–7427. [Google Scholar]; (b) Fukuyama T, Liu G. Pure Appl. Chem. 1997;69:501–505. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Madin A, O’Donnell CJ, Oh T, Old DW, Overman LE, Sharp MJ. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1999;38:2934–2936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.(a) Ng FW, Lin H, Tan Q, Danishefsky SJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:545–548. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hong L, Ng FW, Danishefsky SJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:549–551. [Google Scholar]; (c) Ng FW, Lin H, Danishefsky SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:9812–9824. doi: 10.1021/ja0204675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yokoshima S, Tokuyama H, Fukuyama T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2000;39:4073–4075. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20001117)39:22<4073::aid-anie4073>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.See the preceding paper in this journal.

- 25.For a comprehensive review of the intramolecular Heck reaction, see: Link JT. Org. React. 2002;60:157–534.For reviews of the utility of intramolecular Heck reactions in complex molecule construction, see: Link JT, Overman LE. Chemtech. 1988;28:19–26.Overman LE, Link JT. In: Cross Coupling Reactions. Diederich F, Stang PJ, editors. Weinheim: VCH; 1998. pp. 231–269.Dounay AB, Overman LE. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:2945–2964. doi: 10.1021/cr020039h.

- 26.At the time there was only a single example of successful intramolecular Heck cyclization of a tetrasubstituted double bond.9a Even today, despite the recent intense investigations in this area, there are only a few examples of intramolecular Heck cyclizations of tetrasubstituted olefins, most from various investigations in our laboratories.25a

- 27.Cacchi S, Ciattini PG, Morera E, Ortar G. Tetrahedron Lett. 1986;27:3931–3934. [Google Scholar]

- 28.The analogous iodo amide can be prepared by a two step sequence, involving initial palladium-catalyzed carbonylation of 8 in methanol27 followed by aminolysis of the resulting methyl ester with the dimethylaluminum amide of 2-iodoaniline.

- 29.Similar success in this Heck cyclization was observed when the amide protecting group was a benzyl or methoxymethyl group. The iodide analog of 10a cyclized with similar low stereoselectivity.

- 30.The C19 proton of the terminal vinyl group is observed at lower field in the 1H NMR spectrum of the oxindole isomer that places the carbonyl group proximal to C19 than in its epimer. For example, for epimers 11a/11b this signal is seen at 6.7 ppm, whereas it is seen at 6.2 ppm in isomers 12a/12b.

- 31.In a preliminary description of these studies,9d these conditions were inappropriately described as "ligandless"; however, dba is likely bound to palladium during the Heck insertion sequence.32

- 32.Amatore C, Broeker G, Jutand A, Khalil F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:5176–5185. [Google Scholar]

- 33.These conditions were employed by Speckamp and Hiemstra for construction of the spirooxindole in their early synthesis of (±)-gelsemine.18

- 34.Yoon NM, Brown HC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1968;90:2927–2938. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nikolaides N, Ganem B. J. Org. Chem. 1989;54:5996–5998. [Google Scholar]

- 36.(a) White EH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1955;77:6008–6010. [Google Scholar]; (b) White EH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1955;77:6011–6014. [Google Scholar]; (c) White EH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1955;77:6014–6022. [Google Scholar]; (d) White EH. Organic Syntheses. Collect. Vol. V. New York: Wiley; 1973. pp. 336–339. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Romea P, Urpi F, Vilarrasa J. J. Org. Chem. 1989;54:3209–3211. [Google Scholar]

- 38.This complex was found to be slightly more selective than AlH3, see: Marlett EM, Park WS. J. Org. Chem. 1990;55:2968–2969.

- 39.Attempts to reduce the nitrile group of 22 or 23 with DIBALH or LiAlH4 resulted in unidentifiable products.

- 40.Bergeron RJ, McManis JS. J. Org. Chem. 1988;53:3108–3111. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kisfaludy L, Mohacsi T, Low M, Drexler F. J. Org. Chem. 1979;44:654–656. [Google Scholar]

- 42.The configuration of the nitrile substituent of 18 and 30 was determined by correlating the coupling constants predicted by the Karplus–Conroy equation with the observed coupling constants. In 18 the dihedral angle between the hydrogens at C16 and C5 is ~90° and that between the hydrogens at C16 and C15 is ~15°, so a doublet with a 7 Hz coupling constant is predicted; the observed coupling is 7.2 Hz. Likewise for 30, the dihedral angle between the hydrogens at C16 and C5 is ~30° and that between the hydrogens on C16 and C15 is approximately 90°, so a doublet with a 4 Hz coupling constant is predicted; the observed coupling is 4.2 Hz.

- 43.A related epimerization was employed by Fukuyama and Liu in their synthesis of (±)-gelsemine.20

- 44.For a detailed account of these studies, see: Old DW. Ph.D. Dissertation. Irvine: University of California; 1997.

- 45.For reviews of diastereoselective protonations, see: Zimmerman HE. Acc. Chem. Res. 1987;20:263–268.Fehr C. Chimia. 1991;45:253–261.Krause N, Ebert S, Haubrich A. Liebigs Ann./Recueil. 1997:2409–2418.Eames J, Weerasooriya N. J. Chem. Research (S) 2001:2–8.

- 46.Several examples of electrophile-promoted cyclization of the oxindole and vinyl groups of gelsemine were encountered during early degradation studies.3a

- 47.Knapp S, Levorse AT. J. Org. Chem. 1988;53:4006–4014. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Clive DLJ, Wong CK, Kiel WA, Menchen SM. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1978:379–380. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Craig PN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1952;74:129–131. [Google Scholar]

- 50.(a) Danishefsky S, Taniyama E, Webb RR. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983;24:11–14. [Google Scholar]; (b) Danishefsky S, Taniyama E. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983;24:15–18. [Google Scholar]

- 51.(a) Takacs JM, Helle MA, Takusagawa F. Tetrahedron Lett. 1989;30:7321–7324. [Google Scholar]; (b) Amoroso R, Cardillo G, Tomasini C, Tortoreto P. J. Org. Chem. 1992;57:1082–1087. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tamao K, Ishida N. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984;25:4249–4252. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tamao K, Ishida N, Kumada M. J. Org. Chem. 1983;48:2120–2122. [Google Scholar]

- 54.(a) Fetizon M, Hanna I, Rens J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985;26:3453–3456. [Google Scholar]; (b) Fetizon M, Goulaouic P, Hanna I. Synthesis. 1987:503–505. [Google Scholar]

- 55.(a) Creger PL. J. Org. Chem. 1972;37:1907–1918. doi: 10.1021/jo00977a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Danishefsky S, Schuda PF, Kitahara T, Etheredge SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1977;99:6066–6075. doi: 10.1021/ja00426a066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.(a) Cooke MP., Jr J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1970;92:6080–6082. [Google Scholar]; (b) Collman JP, Finke RG, Cawse JN, Brauman JI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1977;99:2515–2526. [Google Scholar]; (c) Collman JP. Acc. Chem. Res. 1975;8:342–347. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mérour JY, Roustan JL, Charrier C, Collin J, Benaïm J. J. Organomet. Chem. 1973;51:C24–C26. [Google Scholar]

- 58.(a) McMurry JE, Andrus A, Ksander GM, Muser JH, Johnson MA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979;101:1330–1332. [Google Scholar]; (b) McMurry JE, Andrus A, Ksander GM, Muser JH, Johnson MA. Tetrahedron. 1981;37 Supplement No. 1:319–327. [Google Scholar]

- 59.The Hart total synthesis of (±)-21-oxogelsemine also features a base-promoted epimerization of a spirocyclic oxindole intermediate.

- 60.We examined also, without success, opening the methyl aziridinium ion derived from 46 with a variety of one-carbon nucleophiles.

- 61.See, for example: Hynes J, Jr, Overman LE, Nasser T, Rucker PV. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:4647–4650.

- 62.Lipton MF, Basha A, Weinreb SM. Organic Syntheses. Collect. Vol. VI. New York: Wiley; 1988. pp. 492–495. [Google Scholar]

- 63.(a) Corey EJ, Shulman JI. J. Org. Chem. 1970;35:777–780. [Google Scholar]; (b) Trost BM, Stanton JL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1975;97:4018–4025. [Google Scholar]

- 64.(a) Davis FA, Sheppard AC. Tetrahedron. 1989;45:5703–5742. [Google Scholar]; (b) Davis FA, Chen B-C. Chem. Rev. 1992;92:919–934. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Guertin KR, Chan T-H. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32:715–718. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vedejs E, Engler DA, Telschow JE. J. Org. Chem. 1978;43:188–196. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Julia M, Jalmes VP-S, Plé K, Verpeaux J-N, Hollingworth G. Bull. Soc. Chim. Fr. 1996;133:15–24. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bailey EJ, Barton DHR, Elks J, Templeton JF. J. Chem. Soc. 1962:1578–1591. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Moriarty RM, Hou K–C. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984;25:691–694. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vaz ADN, Schoellmann G. J. Org. Chem. 1984;49:1286–1288. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rubottom GM, Vazquez MA, Pelegrina DR. Tetrahedron Lett. 1974;15:4319–4322. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Moriarty RM, Prakash O, Duncan MP, Vaid RK, Musallam HA. J. Org. Chem. 1987;52:150–153. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Comins DL, Dehghani A. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:6299–6302. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Trapping the resulting enolate with N-phenyl-bis(trifluoromethanesulfonimide) was successful, but gave inconsistent yields.

- 75.Hynes J, Jr, Nasser T, Overman LE, Watson DA. Org. Lett. 2002;4:929–931. doi: 10.1021/ol017303y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.At this point, it is unclear why stereoselection in the Heck cyclization varies with the nature of the β-substituent.

- 77.Silverstein RM, Bassler GC, Morrill TC. Spectrometric Identification of Organic Compounds. 5th Edition. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1991. Chapter 5. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Evans DA, Carroll GL, Truesdale LK. J. Org. Chem. 1974;39:914–917. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nagata W, Yoshioka M, Murakami M. Org. Synth. 1972;52:96–99. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Luche J-L, Gemal AL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979;101:5848–5849. [Google Scholar]

- 81.(a) Katzenellenbogen JA, Bowlus SB. J. Org. Chem. 1973;38:627–632. [Google Scholar]; (b) Heinshon GE, Ashby EC. J. Org. Chem. 1973;38:4232–4236. [Google Scholar]; (c) Overman LE, McCready RJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 1982;23:2355–2358. [Google Scholar]

- 82.In product 73, an NOE is observed between the cyclohexyl proton at C3, the vinyl proton at C19, and the aromatic proton at C9. These NOEs are consistent with the cyclohexyl ring of 73 existing in a twist boat conformation.

- 83.Kursanov DN, Parnes ZN, Loim NM. Synthesis. 1974:633–651. [Google Scholar]

- 84.The yield of the largest scale reaction we conducted of each step was used in this calculation. For intramolecular Heck reaction of 68 an average yield of 69% was used as this reaction was only carried out on one scale.

- 85.The first step of our gelsemine synthesis is a Diels–Alder reaction of a 1,3-cyclohexadiene with methyl acrylate.24 As chiral auxiliaries for acrylate dienophiles have been developed and much progress in asymmetric catalysis of Diels–Alder reactions has been recorded, it would appear likely that an enantioselective version of the opening moves of our gelsemine synthesis could be developed.85

- 86.For selected reviews of asymmetric Diels–Alder reactions, see: Oh T, Reilly M. Org. Prep. Proced. Int. 1994;26:129–158.Kagan HB, Riant O. Chem. Rev. 1992;92:1007–1019.Corey EJ. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002;41:1650–1667. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020517)41:10<1650::aid-anie1650>3.0.co;2-b.For a review of the use of the Diels–Alder reaction in natural products total synthesis, see: Nicolaou KC, Snyder SA, Montagnon T, Vassilikogiannakis G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002;41:1668–1698. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020517)41:10<1668::aid-anie1668>3.0.co;2-z.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Experimental procedures, spectroscopic and analytical data for new compounds, 1H NMR spectra of selected compounds, and 1H and 13C NMR spectra of synthetic (±)-gelsemine and natural gelsemine (79 pages). This material is free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.