Abstract

The p75NTR functions as a tumor suppressor in prostate epithelial cells, where its expression declines with progression to malignant cancer. Previously, we demonstrated that treatment with R-flurbiprofen or ibuprofen induced p75NTR expression in several prostate cancer cell lines leading to p75NTR mediated decreased survival. Utilizing the 2-phenyl propionic acid moiety of these profens as a pharmacophore, we screened an in silico data base of 30 million compounds and identified carprofen as having an order of magnitude greater activity for induction of p75NTR levels and inhibition of cell survival. Prostate (PC-3, DU-145) and bladder (T24) cancer cells were more sensitive to carprofen induction of p75NTR associated loss of survival than breast (MCF7) and fibroblast (3T3) cells. Transfection of prostate cell lines with a dominant negative form of p75NTR prior to carprofen treatment partially rescued cell survival demonstrating a cause and effect relationship between carprofen induction of p75NTR levels and inhibition of survival. Carprofen induced apoptotic nuclear fragmentation in prostate but not in MCF7 and 3T3 cells. Furthermore, siRNA knockdown of the p38 MAPK protein prevented induction of p75NTR by carprofen in both prostate cell lines. Carprofen treatment induced phosphorylation of p38 MAPK as early as within 1 minute. Expression of a dominant negative form of MK2, the kinase downstream of p38 MAPK frequently associated with signaling cascades leading to apoptosis, prevented carprofen induction of the p75NTR protein. Collectively, we identify carprofen as a highly potent profen capable of inducing p75NTR dependent apoptosis via the p38 MAPK pathway in prostate cancer cells.

Keywords: Carprofen, p75NTR, p38 MAPK, MK2, Apoptosis

Introduction

The p75 neurotrophin receptor (p75NTR) is a 75 kD cell surface receptor glycoprotein that shares both structural and sequence homology with the tumor necrosis factor receptor super-family of proteins (1, 2). Some of these proteins (e.g. p75NTR, p55TNFR, Fas, DRs3-6, EDAR) have similar sequence motifs of defined elongated structure (1) designated “death domains” based upon their apoptosis inducing function (2). In the human prostate the p75NTR protein is progressively lost in pathologic cancer tissues (3). The proportion of epithelial cells that have retained p75NTR expression in the organ confined pathological prostate is inversely associated with increasing Gleason's score and pre-operative serum PSA concentrations (4). In addition, immunoblot of human prostate epithelial cell lines derived from metastases exhibit a further reduction of p75NTR expression (5). Significantly, even though expression of the p75NTR protein is suppressed the gene encoding p75NTR appears intact in these prostate cancer cells (6). The loss of p75NTR expression is a result of a loss of mRNA stability (6). Following ectopic re-expression of the p75NTR in these cancer cells their rate of apoptosis increased (7). Additionally, the same ectopically expressing p75NTR cancer cells exhibited a retardation of cell cycle progression characterized by accumulation of cells in G1 phase with a corresponding reduction of cells in the S phase of the cell cycle (7). Consistent with these observations, the p75NTR has been characterized with both tumor suppressor and metastasis suppressor activity in prostate cancer cells (7, 8).

Several studies have demonstrated that non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are effective as anticancer agents for colorectal, breast, pancreatic cancer, squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck, bladder, ovarian, lung and prostate cancer (9,10). With respect to prostate cancer, retrospective studies indicate that there is a significantly reduced risk of prostate cancer associated with regular use of NSAIDs (11-13). In vivo studies using rodents have indicated that NSAIDs can decrease the size of prostate tumors (14, 15) and suppress the metastasis of prostatic cancer (14, 16). There is no common mechanism of action underlying NSAIDs effectiveness against cancer cells. Some NSAIDs inhibit the cyclooxygenases (COX) that convert arachidonic acid to prostaglandins (17). Prostaglandins are thought to contribute to tumor growth by inhibiting apoptosis (18) and by inducing the formation of new blood vessels needed to sustain tumor growth (19). Hence, COX inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis could explain part of the anti-tumor activity of certain NSAIDs. However, NSAIDs can also inhibit tumor formation and growth of COX-null cell lines (20). In addition, NSAIDs that lack COX inhibitory activity can still have significant anticancer effects both in vivo (21) as well as in vitro (22). Similarly, growth of the DU-145 prostate cancer cell line that lacks expression of COX-1 and COX-2 is inhibited by NSAIDs (23). Interestingly, R-flurbiprofen and ibuprofen have been shown to induce p75NTR levels leading to apoptosis in prostate cancer cell lines (23). These profens activated the p38 MAPK pathway leading to stabilization of p75NTR mRNA and increased levels of p75NTR protein that subsequently induced apoptosis of the prostate cancer cells (24). In this report we utilized the 2-phenyl propionic acid moiety of the profens as a pharmacophore for an in silico search of related compounds and identified carprofen as having an order of magnitude greater activity for induction of p75NTR levels and inhibition of cell survival. Carprofen activity occurred through rapid phosphorylation of p38 MAPK which signaled through MK2 to increase levels of p75NTR protein and stimulate apoptosis in the prostate cancer cells.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines and Culture Conditions

PC-3 and DU-145 prostate cell lines were obtained from the tissue culture core facility of the Georgetown University Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center. T24 bladder, MCF7 breast and 3T3 fibroblast cells were obtained from ATCC. All cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Mediatech Inc., Herndon, VA) containing 4.5g/L glucose and L-glutamine supplemented with antibiotic/antimycotic [100 units/mL penicillin G, 100 μg/mL streptomycin and 0.25 μg/mL amphotercin B (Mediatech Inc.)] and 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO). Cells were incubated in the presence of 5% CO2 and air at 37°C.

Drug Preparation, Treatment, Cell Lysis

Using 2-phenyl propionic acid as a pharmacophore we searched an in silico data base of approximately 30 million compounds from which nine aryl propionic acids were selected for further analysis. Stock solutions were prepared by dissolving each aryl propionic acid in dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma Chemical Co. St. Louis, MO) at a concentration of 200 mM. Cells were seeded overnight at 70-80% confluency and were then treated for 48 hours at concentrations of 0, 20, 40, 60, 80 and 100 μM. Cell lysates of treated cells were prepared as previously described (7, 8, 23). The supernatant was retained and protein concentration was determined according to the manufacturer's protocol (BioRad Laboratories, Hercules, CA).

Immunoblot Analysis

Immunoblot analysis was performed as previously described (23). Membranes were incubated in the primary antibody: murine monoclonal anti-p75NTR (1:2000, Upstate Cell Signaling Solutions, Lake Placid, NY), rabbit polyclonal phosphorylated p38 MAPK (1:1000), mouse monoclonal anti-p38α (1:1000 ; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA ), or murine monoclonal anti-β-actin (1:5000, Sigma Chemical Co. St. Louis, MO). Membranes were subsequently incubated in goat-anti-mouse or goat-anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (BioRad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) at a dilution of 1:2000 and immunoreactivity visualized with a chemiluminescence detection reagent (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ). The positive control for p75NTR expression was a whole cell lysate of A875 cells (Dr. Moses Chao, Cornell University, NY).

Cell Survival Assay with p75NTR Dominant Negative Transfection and Hoechst Dye Nuclear Staining

An equal number of viable cells (2 × 103 cells/well) in 96 well culture plates (final volume of 100 μl culture medium per well) were incubated for 4 h at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. Some cells were also transiently transfected with a p75NTR dominant negative vector described previously (24, 25, 26). The ΔICD vector expresses a p75NTR gene product with the intracellular domain (ICD) deleted. The ΔICD is an ecdysone-inducible p75NTR vector, and therefore was co-transfected with the ecdysone receptor plasmid pVgRxR. The transfection was performed with LipofectAMINE reagent (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA) in serum-free medium for 6 hours, after which serum containing medium was added. After 18 subsequent hours, cells were incubated in 1 μM ponasterone A (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA) for 24 hours to drive expression of the dominant negative gene product. Following incubation with ponasterone A, cells were treated with carprofen (0 – 100 μM) for 48 hours and relative cell survival was determined with MTT (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide) labeling reagent (final concentration 0.5 mg/ml, Roche Diagnostics Corporation, Indianapolis, IN). Subsequently, cells were incubated overnight with 100 μl of solubilization solution per well and the samples quantified at 570 nm using a micro titer plate reader (BioRad Laboratories, Richmond, CA). Hoechst dye nuclear (DNA) staining to identify apoptotic nuclei was conducted as described previously (25). PC-3, DU-145, MCF-7 and 3T3 cells were treated for 48 hours with carprofen and then fixed in 10% formalin (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA). Some cells were transfected with the ΔICDp75NTR plus ponasterone A prior to carprofen treatment.

siRNA Transfection

Cells were transfected for 72 hours with non-targeting siRNA or siRNA specific for p38α (J-003512-20), (Dharmacon RNA Technologies, Lafayette, CO) at final concentrations of 100 nM according to the manufacturer's protocol. Transfection reagent DharmaFECT 1 was used for DU-145 cells, and DharmaFECT 2 was used for PC-3 cells (Dharmacon RNA Technologies, Lafayette, CO). After transfection, the cells were treated with carprofen for 48 hours, followed by determination of p75NTR protein expression.

MK2 Dominant Negative Transfection

PC-3 and DU-145 cells were transiently transfected with a MK2 dominant negative vector (MK2-K76R) described previously (27). The transfection was performed with LipofectAMINE reagent (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA) in serum-free medium for 6 hours, after which serum containing medium was added for 24 hours to allow expression of the dominant negative gene product. Cells were treated with carprofen (100 μM) for 48 hours and expression of p75NTR protein determined by immunoblot with mouse monoclonal anti-p75NTR (1:2000; Millipore, Billerica, MA) (1:2000).

Statistical Analysis

The statistical differences between data sets and/or means were analyzed by ANOVA or the Mann-Whitney test using the Prizm program (Graph Pad Software) and the data expressed as the mean ± SEM. Data was considered statistically significant when p≤0.05.

Results

Carprofen Exhibits Superior Efficacy of the Aryl Propionic Acids to Induce p75NTR Levels Associated with Cell Specific Decreased Survival

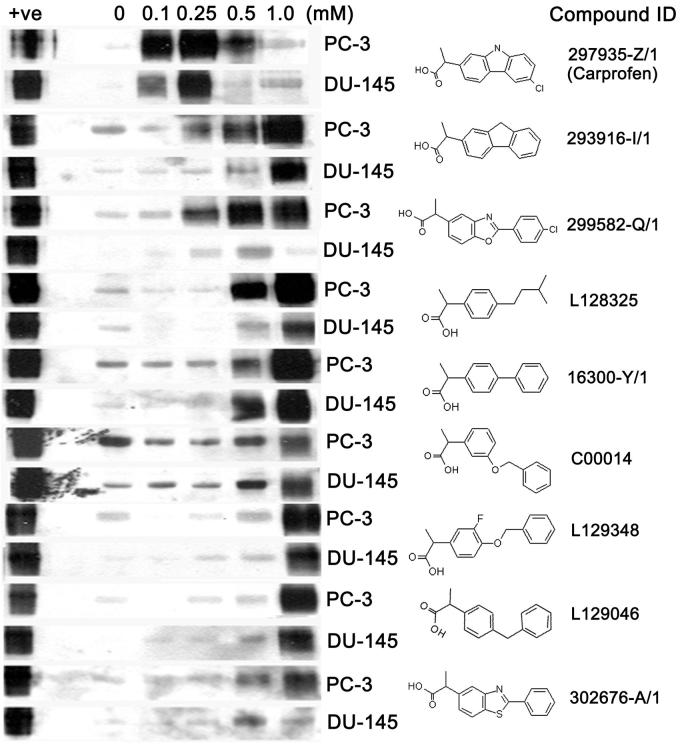

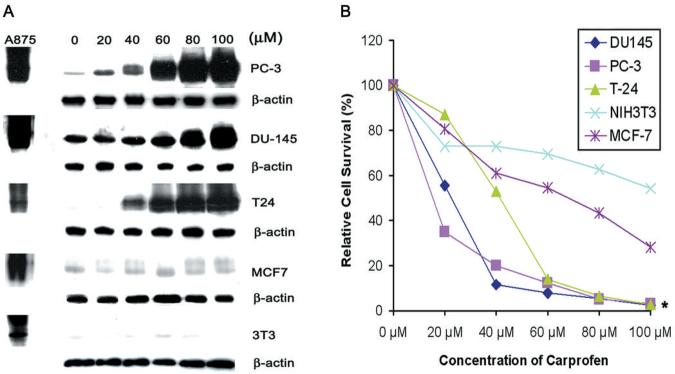

Analysis of the 2-phenyl propionic acid pharmacophore homology search identified nine aryl propionic acids that were screened for activity to induce expression of p75NTR protein in PC-3 and DU-145 human prostate cancer cells. Initially, the PC-3 and DU-145 cell lines were selected since they are the only two prostate tumor cell lines included in the NIH DTP anticancer drug discovery program. The immunoblots demonstrating activity of each compound to induce p75NTR were placed in rank-order (Figure 1). In both cell lines, carprofen exhibited superior efficacy for induction of p75NTR expression at a concentration of 100 μM or less compared with all other aryl propionic acids examined (Figure 1). At lower concentrations, carprofen selectively induced expression of p75NTR protein at approximately 40 μM and above in PC-3 and DU-145 prostate cancer cells, as well as in the T24 bladder cancer cell line, but not in the MCF-7 breast cancer cell line or the 3T3 fibroblast cell line (Figure 2A). The T24 bladder cancer cell line was included as a positive control since they were previously shown to be sensitive to profen (ibuprofen, R-flurbiprofen) induced p75NTR-dependent decreased survival, whereas MCF-7 and 3T3 cells were included as negative controls since they were previously shown not to be sensitive to profen (ibuprofen, R-flurbiprofen) induced decreased survival (25).

Figure 1.

Immunoblots of p75NTR levels in PC-3 and DU-145 cells following 48 hour treatment with 0, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, and 1.0 mM of drug. The compound identification (ID) of each drug is given adjacent to its chemical structure. The A875 melanoma cell line was used as a positive control (+ve) for p75NTR expression.

Figure 2.

A. Immunoblots of p75NTR levels with corresponding α-actin loading controls in PC-3 and DU-145 prostate cancer cells, T24 bladder cancer cells, MCF-7 breast cancer cells and 3T3 fibroblasts after 48 hour treatment with 0, 20, 40, 60, 80 and 100 M carprofen. A875 cell lysates were used as positive controls (+ve) for p75NTR expression. B. A MTT cell survival assay of PC-3 and DU-145 prostate cancer cells, T24 bladder cancer cells, MCF-7 breast cancer cells and 3T3 fibroblasts following 48 hour treatment with 0, 20, 40, 60, 80 and 100 μM carprofen. *p<0.01

Carprofen treatment selectively decreased the survival of cells in rank-order with PC-3 and DU-145 prostate cancer cells exhibiting greatest sensitivity to dose-dependent decreased survival followed by the T24 bladder cancer cells, and with MCF-7 and 3T3 fibroblasts the least sensitive to carprofen induced decreased survival (Figure 2B). Significantly, there was a strong association between the dose-dependent induction of p75NTR levels (Figure 2A) and decreased survival of specific cell types following carprofen treatment (Figure 2B).

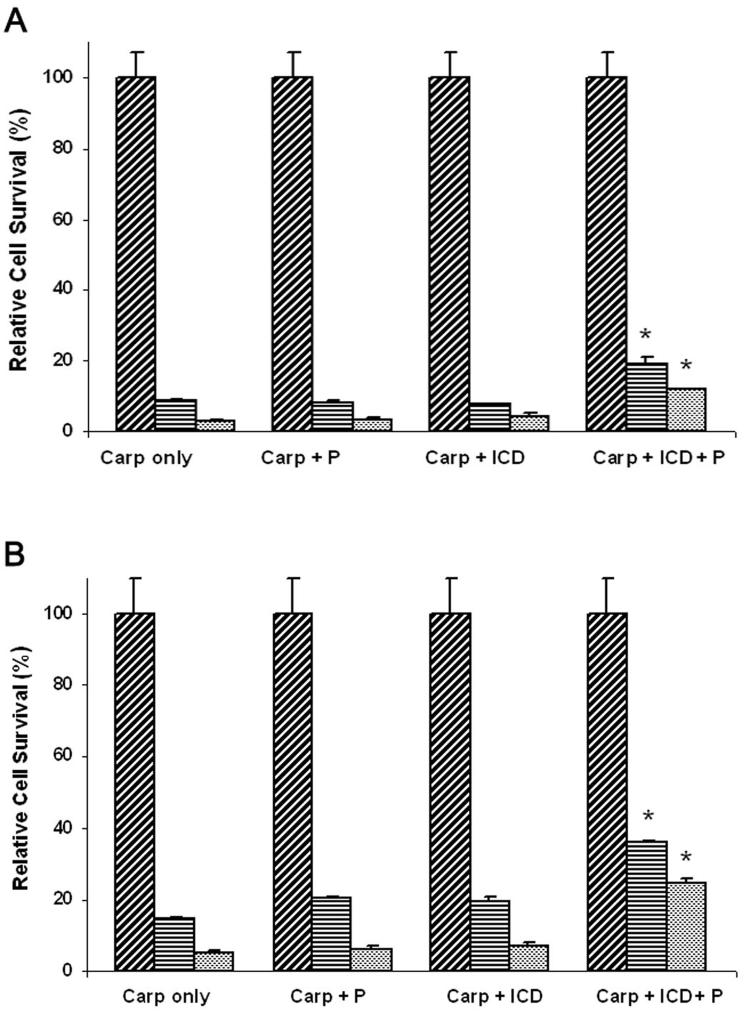

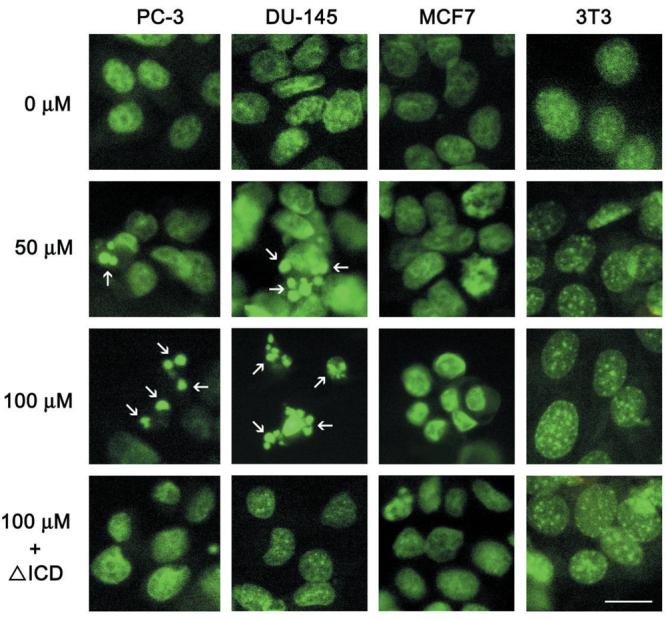

Carprofen Induced Decreased Prostate Cancer Cell Survival is Dependent on p75NTR

In order to establish a causal relationship between carprofen induction of p75NTR protein expression and inhibition of cell survival we utilized a ponasterone A inducible expression vector for p75NTR that exhibits a deletion of the intracellular death domain (ΔICDp75NTR) shown to function as a dominant negative antagonist of the intact p75NTR gene product (23-26). The treatment of both PC-3 and DU-145 cells with carprofen or carprofen plus ponasterone A inhibited cell survival in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 3). However, both PC-3 and DU-145 cell lines induced with ponasterone A to express ΔICDp75NTR exhibited a significant (p < 0.001) partial rescue from carprofen-mediated inhibition of cell survival relative to carprofen treated ΔICDp75NTR cells in the absence of ponasterone A (Figure 3). Subsequently, we examined Hoechst stained nuclear morphology to identify fragmented nuclei typical of apoptotic cells with the exception of T24 bladder cells for which we have previously demonstrated profen induced apoptotic nuclear fragmentation (25). Treatment of the two prostate cancer cell lines (DU-145, PC-3) with carprofen induced a dose-dependent (0 – 100 μM) fragmentation of nuclei (Figure 4). As negative controls, the MCF7 and 3T3 cells that were not induced by carprofen to express p75NTR (Figure 2A) did not undergo carprofen dependent apoptotic nuclear fragmentation (Figure 4). Expression of the ΔICDp75NTR dominant negative vector prior to carprofen treatment partially rescued nuclear fragmentation in the PC-3 and DU-145 prostate cells, whereas the MCF-7 and 3T3 negative control cells did not exhibit fragmented nuclei (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

PC-3 (A) and DU-145 (B) cell survival analysis by MTT assay following 48 hour treatment with 0 μM (cross-hatched), 50 μM (diagonal), or 100 μM (stippled) carprofen (Carp). Prior to treatment, cells were co-transfected with a ponasterone A-inducible ecdysone receptor plasmid pVgRxR and ΔICDp75NTR (ICD). Following transfection, cells were incubated in serum containing medium for 18 hours, and then incubated in 1 μM ponasterone A (P) for 24 hours to drive expression of the dominant negative gene products (ICD). Results are expressed relative to the control (0 μM). *, P < 0.001

Figure 4.

Detection of apoptotic nuclei (arrows) by Hoechst staining of PC-3 and DU-145 prostate cancer cells, MCF-7 breast cancer cells and 3T3 fibroblasts following treatment with 0, 50 or 100 μM carprofen for 48 hr. Prior to treatment, some cells were co-transfected with a ponasterone A-inducible ecdysone receptor plasmid pVgRxR and ΔICDp75NTR (ICD). Following transfection, cells were incubated in serum containing medium for 18 hours, and then incubated in 1 μM ponasterone A (P) for 24 hours to drive expression of the dominant negative gene products and then treated with 100 μM carprofen for 48 hr. Scale bar = 5 μM

Carprofen Induction of p75NTR occurs via the p38 MAPK Pathway

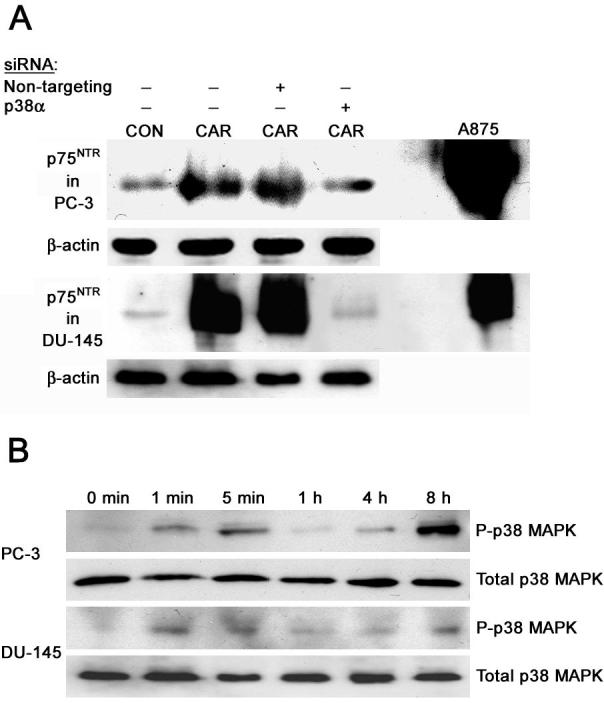

An earlier study from our laboratory (24) implicated the aryl propionic acids, R-flurbiprofen and ibuprofen, in the induction of p75NTR via the p38 MAPK pathway. Since carprofen, an aryl propionic acid, exhibits an order of magnitude greater potency (Figure 2A) than R-flurbiprofen and ibuprofen for the induction of p75NTR expression levels (23, 24) we examined the effect of siRNA knockdown of the p38α MAPK isoform on p75NTR levels following treatment with carprofen. We previously demonstrated that p38α MAPK is the predominant isoform expressed in PC-3 and DU-145 cells (24). Whereas treatment with carprofen induced p75NTR expression levels, transfection of prostate cancer cells with p38α siRNA prior to carprofen treatment prevented induction of p75NTR relative to untransfected cells or cells transfected with non-targeting siRNA (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

A. Knockdown of p38 MAPK prevents induction of p75NTR by carprofen. PC-3 and DU-145 cells were transfected with non-targeting siRNA or siRNA for p38α for 72 hours. Following transfection, cells were treated with 100 μM carprofen (CAR), or DMSO vehicle control (CON) and the cell lysates used for immunoblot analysis. A875 cell lysates were used as a positive control for p75NTR expression. β-actin (β-act) was used as the loading control. B. Activation of the p38 MAPK pathway by carprofen. PC-3 and DU-145 cells were treated with 100 μM carprofen for 0 minutes, 1 minute, 5 minutes, 1 hour, 4 hours, or 8 hours. Cell lysates were prepared for immunoblot analysis using antibodies to phosphorylated p38 MAPK (P-p38). Blots for P-p38 MAPK were stripped and reprobed for total p38 MAPK.

Since the p38 MAPK is activated by phosphorylation we determined the phosphorylation status of p38 MAPK at several time points in PC-3 and DU-145 cells following treatment with carprofen. In both cell lines, carprofen treatment stimulated rapid phosphorylation of p38 MAPK as early as within one minute of treatment, and subsequently led to the sustained activation of the p38 MAPK pathway that could be observed even 8 hours following treatment of each cell line (Figure 5B).

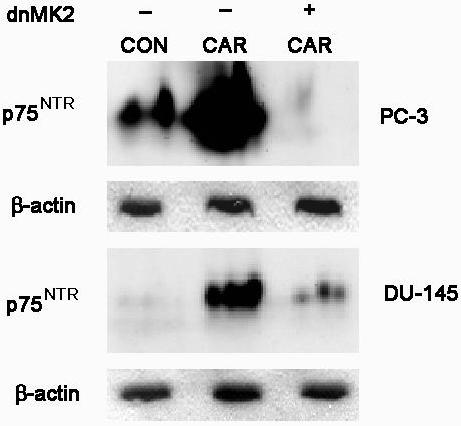

Since the MK2 kinase is downstream of p38 MAPK and was previously shown to be involved in profen induction of p75NTR (24) we used a dominant negative expression vector for MK2 to determine involvement in carprofen induction of p75NTR. Treatment with carprofen alone induced expression of p75NTR in both PC-3 and DU-145 cells, whereas transfection of dnMK2 prior to carprofen treatment decreased the induction of p75NTR (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

PC-3 and DU-145 cells were transfected with dominant negative MK2 (dnMK2), after which serum containing medium was added for 24 hours to allow expression of the dominant negative gene product. Cells were treated with 100 μM carprofen (CAR) for 48 hours. Cell lysates were collected for immunoblot analysis of p75NTR levels. β-actin was used as the loading control.

Discussion

Carprofen is a propionic acid NSAID that induced p75NTR levels in prostate cancer cell lines with an order of magnitude greater efficacy than the related propionic acid NSAIDs, R-flurbiprofen and ibuprofen (23). Concomitant with carprofen's superior efficacy to induce levels of p75NTR was its activity to inhibit cell survival via apoptosis. Our previous studies have demonstrated a strong cause and effect relationship between induced levels of p75NTR and induction of apoptosis in cancer cell lines (23, 25). When expression levels are induced, p75NTR appears to be a robust marker of drug induced apoptosis (23, 25). Since carprofen exhibited some degree of cell specific induction of p75NTR associated apoptosis, we focused on the PC-3 and DU-145 prostate cancer cell lines which were most responsive to carprofen treatment, and coincidently are the only two prostate cancer cell lines included in the NIH DTP anticancer drug discovery program, due to their well characterized aggressive phenotype. Hormone responsive prostate cells were intentionally not included in these studies in order to maintain a focus on potential therapeutics of prostate tumor cells with phenotypes refractory to hormone ablation treatment consistent with poor prognosis. Using the prostate cancer cell lines, PC-3 and DU-145, most responsive to carprofen, we showed that a dominant negative antagonist of p75NTR (ΔICDp75NTR) partially rescued carprofen induced inhibition of cell survival, thereby confirming a cause and effect relationship between carprofen induction of p75NTR levels and p75NTR induction of apoptosis. Partial rather than complete rescue may be attributed to assay conditions or additional effects of carprofen independent of p75NTR.

In prostate cancer cell lines re-expression of p75NTR induces modifications to several down stream signal transduction cascades leading to apoptosis. Initially, p75NTR expression down regulates components of the NFκB and JNK pathways preventing nuclear translocation of both these pro-survival transcriptional effectors (28). Expression of p75NTR also retards cell cycle progression through accumulation of cells in G1 at the expense of S phase cells (7, 26). Down regulation of cyclin/cdk holoenzyme components cyclin E, cyclin A, cdk2 and cdk6 contribute to hypo-phosphorylation of retinoblastoma (Rb), along with elevated levels of p16INK4a in the p75NTR induced cytostatic cells (26). Re-expression of p75NTR also induces elevated expression of the retinoic acid receptor, RAR-β, and retinoid X receptors (RXRα, RXR-β) during partial re-differentiation of PC-3 cells that may also contribute to cytostasis (29). Evidence for p75NTR dependent activation of extrinsic apoptosis in prostate cells has been limited to caspase-8 reductions in RIP, an adaptor protein that interacts with the intracellular domain of p75NTR (28). Evidence for p75NTR dependent activation of the intrinsic mitochondrial pathway includes an increase in pro-apoptotic effectors, Smac, Bax, Bak and Bad and conversely a decrease in the pro-survival effector, Bcl-xl (26) leading to a reduction in XIAP and cleavage of caspase-9 and caspase-7 followed by PARP cleavage and nuclear fragmentation in PC-3 cells (26). Hence, re-expression of p75NTR appears to promote partial re-differentiation, cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in prostate cancer cells thereby providing a rationale for investigation of compounds that may be used for p75NTR dependent therapeutics.

Prostate cancer cells evade the apoptotic effects of p75NTR expression by loss of p75NTR mRNA stability with concomitant suppression of p75NTR protein levels (6). Conversely, R-flurbiprofen and ibuprofen stabilize p75NTR mRNA with concomitant expression of p75NTR protein (24) and induction of apoptosis (23) through the p38 MAPK pathway (24). Indeed, abundant evidence has been reported for the involvement of p38 MAPK in apoptosis induced by a variety of agents such as the profen NSAIDs (23, 24), Fas ligation (30) and NGF withdrawal (31). The later is significant since NGF ligation to the p75NTR acts as a survival signal in prostate cancer cells (26). Conversely, a relative absence of NGF, either by ligand withdrawal, or by up-regulation of p75NTR protein to levels that initially bind residual ligand and then to higher levels that result in unbound (no ligand) p75NTR acts as a stimulus of apoptosis in prostate cancer cells (23, 26, 28). From a potential therapeutic perspective this mechanism of p75NTR dependent apoptosis has the appeal that agents, such as the profens, that elevate p75NTR levels have the same effect as ligand withdrawal leading to apoptosis of cancer cells. Activation of the p38 MAPK signal transduction pathway by carprofen was rapid, within 1 minute, suggesting that carprofen is interacting with a molecule highly proximal to p38 MAPK. The observation that p38 MAPK knockdown prevented carprofen induction of p75NTR levels confirms this pathway as a mechanism responsible for p75NTR regulation. We recently reported similar observations for R-flurbiprofen and ibuprofen activation of p38 MAPK up-regulation of p75NTR dependent apoptosis in prostate cancer cells (24). In this pathway MK2 directly binds to the p38α isoform of MAPK during activation (32). Expression levels of MK2 are relatively robust in both PC-3 and DU-145 prostate cancer cells (24). Indeed, dominant negative antagonism of MK2 prevented carprofen induction of p75NTR levels in prostate cancer cells. These observations suggest that carprofen initiates p75NTR dependent apoptosis through a similar p38 MAPK signal transduction pathway to that of R-flurbiprofen and ibuprofen, albeit at an order of magnitude lower concentration of drug. Additional studies of this mechanism may lead to more potent compounds that induce p75NTR-dependent apoptosis of prostate cancer cells.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor M. Gaestel for providing the dominant negative MK2 construct.

Financial Support: Supported by grants from the NIH (R01DK52626, U56CA101429) and the DOD Prostate Cancer Research Program (PC060409)

References

- 1.Chao MV. The p75 neurotrophin receptor. J Neurobiol. 1994;25:1373–85. doi: 10.1002/neu.480251106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chapman BS. A region of the 75kD neurotrophin receptor homologous to the death domains of TNFR-1 and Fas. FEBS Letters. 1995;374:216–20. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01113-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pflug BR, Dionne CA, Kaplan DR, et al. Expression of the Trk high affinity nerve growth factor receptor in the human prostate. Endocrinology. 1995;136:262–8. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.1.7828539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perez M, Regan T, Pflug B, et al. Loss of the low affinity nerve growth factor receptor during malignant transformation of the human prostate. Prostate. 1997;30:274–9. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(19970301)30:4<274::aid-pros8>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pflug BR, Onoda M, Lynch JH, et al. Reduced expression of the low affinity nerve growth factor receptor in benign and malignant human prostate tissue and loss of expression in four human metastatic prostate tumor cell lines. Cancer Res. 1992;52:5403–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krygier S, Djakiew D. Molecular characterization of p75NTR loss of the expression in human prostate tumor cells. Mol. Carcinogenesis. 2001;31:46–55. doi: 10.1002/mc.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krygier S, Djakiew D. The neurotrophin receptor p75NTR is a tumor suppressor in human prostate cancer. Anticancer Res. 2001;21:3749–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krygier S, Djakiew D. Neurotrophin Receptor p75NTR suppresses growth and nerve growth factor-mediated metastasis of human prostate cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2002;98:1–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taketo MM. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors in tumorigenesis. Part II J Nat Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1609–14. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.21.1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vainio H. Is COX-2 inhibition a panacea for cancer prevention? Int J Cancer. 2001;94:613–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nelson JE, Harris RE. Inverse association of prostate cancer and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): results of a case-control study. Oncol Rep. 2000;7:169–73. doi: 10.3892/or.7.1.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Norrish AE, Jackson RT, McRae CU. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and prostate cancer progression. Int J Cancer. 1998;77:511–4. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980812)77:4<511::aid-ijc6>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberts RO, Jacobson DJ, Girman CJ, et al. A population-based study of daily nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and prostate cancer. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2002;77:219–23. doi: 10.4065/77.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drago JR, Murray C. Control of metastases in the Nb rat prostatic adenocarcinoma model. J. Androl. 1984;5:265–8. doi: 10.1002/j.1939-4640.1984.tb00787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu XH, Kirschenbaum A, Yao S, et al. Inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 suppresses angiogenesis and growth of prostate cancer in vivo. J Urol. 2000;164:820–4. doi: 10.1097/00005392-200009010-00056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pollard M, Chang CF. Investigations on prostatic adenocarinomas in rats. Oncology. 1977;34:129–33. doi: 10.1159/000225205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vane JR. Inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis as a mechanism of action for aspirin-like drugs. Nat New Biol. 971;231:232–5. doi: 10.1038/newbio231232a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheng H, Shao J, Morrow JD, et al. Modulation of apoptosis and Bcl-2 expression by prostaglandin E2 in human colon cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1998;58:362–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Masferrer JL, Leahy KM, Koki AT, et al. Antiangiogenic and antitumor activities of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1306–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang X, Morham SG, Langenbach R, et al. Malignant transformation and antineoplastic actions of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) on cyclooxygenase-null embryo fibroblasts. J Exp Med. 1999;190:451–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.4.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wechter WJ, Kantoci D, Murray ED, Jr, et al. R-flurbiprofen chemoprevention and treatment of intestinal adenomas in the APC(Min)/+ mouse model: implications for prophylaxis and treatment of colon cancer. Cancer Res. 1997;57:4316–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim JT, Piazza GA, Han EK, et al. Sulindac derivatives inhibit growth and induce apoptosis in human prostate cancer cell lines. Biochem Pharm. 1999;58:1097–107. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00200-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quann E, Khwaja F, Zavitz KH, et al. The Aryl Propionic Acid R-Flurbiprofen Selectively Induces p75NTR-Dependent Decreased Survival of Prostate Tumor Cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3254–62. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quann E, Khwaja F, Djakiew D. The p38 MAPK Pathway Mediates Aryl Propionic Acid-Induced messenger RNA Stability of p75NTR in Prostate Cancer Cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:11402–10. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khwaja F, Allen J, Lynch J, et al. Ibuprofen inhibits survival of bladder cancer cells by induced expression of the p75NTR tumor suppressor protein. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6207–13. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khwaja F, Tabassum A, Allen J, et al. The p75(NTR) tumor suppressor induces cell cycle arrest facilitating caspase mediated apoptosis in prostate tumor cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;341:1184–92. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.01.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Engel KH, Schultz F, Martin F, et al. Constitutive activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase-activated protein kinase 2 by mutation of phosphorylation sites and an A-helix motif. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:27213–21. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.27213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Allen J, Khwaja F, Byers S, et al. The p75NTR Mediates a Bifurcated Signal Transduction Cascade through the NFκB and JNK Pathways to Inhibit Cell Survival. Exp Cell Res. 2005;304:69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nalbandian A, Pang AL, Rennert OM, et al. A novel function of differentiation revealed by cDNA microarray profiling of p75NTR-regulated gene expression. Differentiation. 2005;73:385–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2005.00040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Juo P, Kuo CJ, Reynolds, et al. Fas activation of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway requires ICE/CED-3 family proteases. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:24–35. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.1.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xia Z, Dickens M, Raingeaud J, et al. Opposing effects of ERK and JNK-p38 MAP kinases on apoptosis. Science. 1995;270:1326–31. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5240.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gaestel M. MAPKAP kinases – MKs – two's company, three a crowd. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:120–130. doi: 10.1038/nrm1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]