Abstract

Aim. A total of 329 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma have been treated at our unit since 1990. Following the randomized controlled trial in Hong Kong by Lau et al. in 1999, patients have been offered adjuvant lipiodol I-131. The aim of this study was to determine the effectiveness of adjuvant lipiodol I-131, following potentially curative surgery with resection and/or ablation, on overall and disease-free survival rates. Material and methods. The prospectively updated hepatocellular carcinoma database was analysed retrospectively. A total of 34 patients were identified to have received adjuvant lipiodol I-131 post-curative treatment with surgical resection and/or ablation. Patient demographics, clinical, surgical, pathology, and survival data were collected and analysed. Results. Three patients received ablation alone, 24 resection, and 7 resection and ablation. Of the 34 patients treated, there were 2 possible cases of treatment-related fatality (pneumonitis and liver failure). Potential prognostic factors studied for effect on survival included age, gender, serum AFP concentration, Child-Pugh score, cirrhosis, tumor size, portal vein tumor thrombus, tumor rupture, and vascular and margin involvement. The median follow-up duration was 23.3 months. The overall median survival was 40.1 months, while the overall survival rates at 1, 2, 3, and 4 years were 87.1%, 71.7%, 60.7%, and 49.6%, respectively. Median duration to recurrence was 22.3 months. Conclusion. Administration of adjuvant lipiodol I-131 is associated with good overall survival.

Keywords: hepatocellular carcinoma, adjuvant lipiodol I-131

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fifth most common malignancy with an annual worldwide incidence of over half a million 1. Despite the improvements in surveillance, imaging technology, surgical techniques, and perioperative care, the mortality rate associated with the disease is still on the rise 2,3. In the United States, the mortality rate increased from 1.7 per 100,000 in the period 1981 to 1985 to 2.4 per 100,000 in 1991 to 1995 4. The most effective treatments available for HCC to date are liver transplantation, surgical resection, and ablative therapies 5,6. As the benefits with transplantation are restricted, due partly to the limited availability of organs, surgical resection remains the mainstay of treatment 5.

Results of surgical resections show 5-year survival rates ranging from 16% to 42% in the presence of high tumor recurrence rates post-resection 7,8,9. Recurrence, in particular early occurrence, is associated with poorer long-term survival 9,10,11. This has urged the search for a supplementary treatment for resection, whether neoadjuvant or adjuvant, to further improve the survival outcome by reducing the rates of recurrence 12. A Hong Kong randomized controlled trial using lipiodol I-131 as an adjuvant treatment post-liver resection produced very encouraging results in this regard. Lau and colleagues reported, in their treatment group, 3-year median overall and disease-free survival (DFS) rates of 84.8% (p=0.039) and 74.5% (p=0.037), respectively 13.

The aim of this study was to determine the effectiveness of adjuvant lipiodol I-131 on the overall and DFS rates following potentially curative surgery with resection and/or ablation.

Methods

This is a retrospective review of prospectively collected data. Since 1990, 329 patients with HCC have been looked after at the St. George Hospital Liver Unit. Of those, 97 patients have undergone curative surgical treatment with surgical resection and/or ablation depending on the anatomical location of the tumors. Our selection criteria for curative treatment included absence of extrahepatic disease and preserved liver function. Since macroscopically complete extirpation of tumor would be accepted by many as potentially curative, patients with positive margins on histopathological assessment were included in the study. The presence of cirrhosis, tumor thrombus, and tumor invasion in portal and hepatic veins were not absolute contraindications 7. In patients with cirrhotic livers, a supplementary indocyanine green retention test was performed to determine the extent of resectability. Surgical resection was performed using the Cavitron Ultrasonic Surgical Aspirator (CUSA), and all cryoablated tumors were assessed by ultrasonogram to confirm complete tumor necrosis. Treatment was regarded as potentially curative if the liver was macroscopically clear of all tumors post-surgery.

All patients were offered adjuvant lipiodol I-131 after “curative” surgical treatment provided the disease was not present elsewhere. The lipiodol dosage was administered based on the volume of residual liver parenchyma post-surgery. The median treatment interval was 1.9 months (range 1.1–7.9 months). The patients were later followed up with α-Fetoprotein (α-FP) levels, liver function test, and abdominal CT imaging at 1 month post-discharge and at 3-monthly intervals thereafter.

All files were reviewed by 29 September 2007. Data was extracted for patient demographics, hepatitis status, Child-Pugh scoring, preoperative and postoperative α-FP levels, surgical methods, histopathology of resected specimens, lipiodol uptake, disease course, and survival. Overall survival and DFS were calculated from the date of surgery and were analysed using the Kaplan-Meier program via SPSS version 14.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Ill., USA). Results obtained were compared with those of the original article by Lau et al. published in 1999 and other adjuvant lipiodol I-131 studies identified.

Results

Since 1999, out of a total of 73 who were resected and/or ablated, 33 accepted treatments with lipiodol I-131 as postoperative adjuvant therapy. Another patient treated with adjuvant lipiodol I-131 prior to 1999 was also included in the study. All in all, 3 patients were treated with ablation, 24 with surgical resections, and 7 with combined ablation and resections. A total of 15 segmentectomies, 1 left lateral resection, 3 central, 2 left, 1 extended left, 7 right, and 2 extended right hepatectomies were performed. The dosage of lipiodol I-131 administered varied among individual patients. The mean dosage was 1744.7±89.7 (S.E.) MBq. Median duration of interval from surgery to lipiodol I-131 was 1.9 months (range 1.1–7.9 months).

Patient demographics and details of the disease are briefly summarized in Table I. This study group was made up of 24 males and 10 females aged between 25.6 and 80.7 years (median age 60.4 years). Twenty-four cases were a result of chronic hepatitis B and C infections, chronic alcohol consumption, and hemochromatosis. However, etiologies were indeterminate in 10 cases. Sixteen of these HCCs arose on a background of cirrhosis.

Table I. Summary of individual patient demographics and details.

| Patient | Status | Age | Sex | R/A | Lip I-131dose | Pre-op AFP level | Child's score | Cirrhosis | Tumor size (<5 cm) | Portal Vein Thrombus | Rupture | Vascular involvement | Margin involvement | Recurrence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AR | D | 74.5 | M | A | 2000 | 136 | B | √ | – | – | – | N/A | N/A | √ |

| JA | D | 66.3 | M | A | 1000 | 3 | A | √ | – | √ | – | N/A | N/A | √ |

| OM | D | 69.1 | M | A | 1600 | 1335 | A | √ | – | – | – | N/A | N/A | – |

| TA | D | 41.0 | M | R | 1906 | 11990 | B | √ | √ | – | – | – | √ | √ |

| HN | D | 55.6 | M | R | 2219 | 8 | A | – | – | – | √ | √ | – | √ |

| GB | D | 62.8 | M | R | 1500 | 8 | A | √ | √ | √ | – | √ | – | √ |

| BA | D | 64.9 | F | R | 1400 | 400 | A | – | √ | – | – | √ | – | √ |

| ES | D | 61.8 | M | RA | 1000 | 20 | A | – | √ | – | – | – | – | √ |

| FH | D | 73.5 | M | RA | 2170 | 6 | A | √ | √ | – | – | – | – | √ |

| LT | D | 61.1 | F | RA | 800 | 4 | B | √ | √ | – | – | √ | – | √ |

| TDT | D | 55.0 | F | RA | 2000 | 473 | A | √ | √ | – | – | √ | √ | √ |

| KD | D | 80.7 | M | R | 2000 | 7 | A | √ | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| THA | AWD | 50.6 | M | R | 2050 | 2785 | A | – | √ | – | – | – | – | √ |

| EP | AWD | 79.9 | M | R | 2134 | 2 | B | – | √ | – | – | – | – | √ |

| SW | AWD | 25.6 | M | R | 2000 | 12 | A | – | √ | √ | – | – | – | √ |

| PSY | AWD | 57.0 | F | R | 2280 | 73 | A | √ | – | – | – | √ | – | √ |

| MZ | AWD | 57.2 | F | R | 2053 | 12 | A | √ | – | – | – | – | – | √ |

| RR | AWD | 72.1 | M | R | 1000 | 31 | A | – | √ | – | – | √ | √ | √ |

| CC | AWD | 45.3 | M | R | 2100 | 195 | A | – | √ | – | – | – | – | √ |

| MY | AWD | 62.1 | M | R | 1000 | 33 | A | – | √ | – | – | √ | – | √ |

| BCD | AWD | 41.4 | M | R | 469 | 2150 | A | √ | √ | – | – | √ | – | √ |

| JW | AWD | 70.5 | M | R | 2000 | 4 | A | – | – | – | – | – | – | √ |

| JL | AWD | 65.4 | F | R | 1310 | – | – | – | √ | – | – | – | – | √ |

| KE | AWD | 59.7 | F | RA | 1240 | 6 | B | √ | √ | – | – | – | √ | √ |

| VA | NED | 44.5 | M | RA | 2000 | 168000 | A | – | √ | – | – | √ | – | – |

| GT | NED | 59.6 | M | RA | 2200 | 4 | A | – | – | – | – | – | √ | – |

| MDN | NED | 72.2 | M | R | 2256 | 9 | A | √ | √ | – | – | – | – | – |

| XYP | NED | 42.8 | F | R | 2000 | 205 | A | √ | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| KH | NED | 52.7 | F | R | 2000 | 35000 | A | – | √ | – | – | – | √ | – |

| TK | NED | 72.5 | M | R | 2200 | – | A | – | √ | – | – | – | – | – |

| GW | NED | 71.8 | F | RA | 2000 | <5 | A | – | √ | – | – | √ | – | √ |

| SP | NED | 36.4 | M | R | 1800 | 8 | A | √ | √ | – | – | √ | – | N/A |

| MH | NED | 44.9 | M | R | 201 | 3 | A | – | √ | – | – | – | √ | N/A |

| RD | NED | 45.3 | M | R | 2000 | – | – | – | √ | – | – | √ | – | N/A |

Abbreviations: D, dead; NED, no evidence of disease; AWD, alive with disease; NA, non-applicable; M, male; F, female; A, ablation; R, resection; RA, resection and ablation.

Clinical assessments revealed 27 cases of Child-Pugh A and 5 Child-Pugh B. Liver functions of two other patients could not be established. Preoperative serum α-FP concentration was obtained for all except three patients. The median α-FP level computed was 12 ng/ml with 8 patients having levels of 400 ng/ml and above.

Tumor characteristics were established with radiological imagings and pathohistological analysis of surgically resected specimens only. A majority of patients (23) had solitary tumors, while 11 others had at least 2 lesions. We recorded tumor sizes at the maximal diameter and found that 23 patients had lesions larger than 5.0 cm. The median tumor size was valued at 8.0 cm (range 2.0–20.0 cm). Portal vein thrombosis was evident in three patients. Microvasculature was involved in 13 and margins were microscopically positive in 7 of the 31 resection patients. Three fibrolamellar variants were also identified. With respect to the degree of differentiation, 8 were well-differentiated, 3 well to moderate, 14 moderate, and 1 was poorly differentiated. Tumor differentiation was not reported in 2 patients.

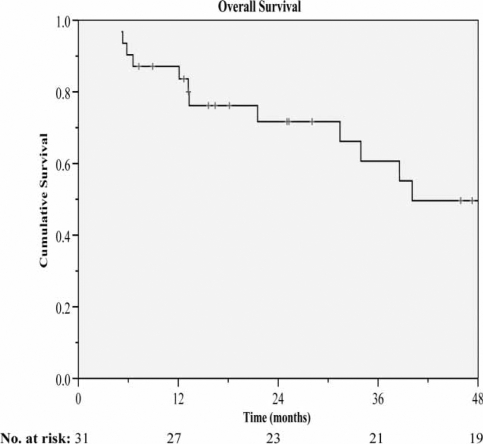

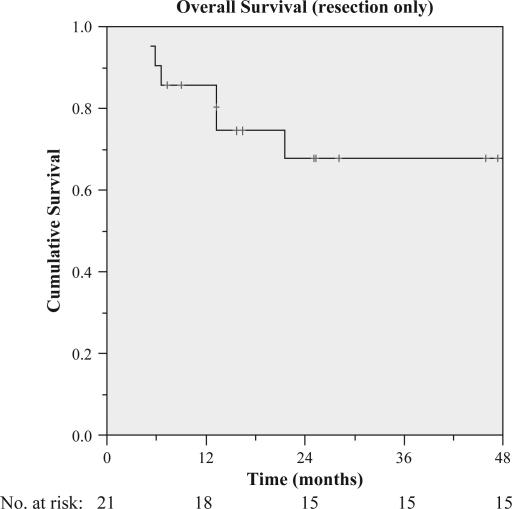

At the time of analysis, three patients were lost to follow-up and were excluded from both overall survival and DFS analysis. The median duration of follow-up was 23.3 months (range 4.9–94.9 months), during which 12 patients died and tumor recurred in 22 others. The median overall survival was 40.1 months (range 5.2–94.9 months), while the overall survival rates at 1, 2, 3, and 4 years were 87.1%, 71.7%, 60.7%, and 49.6%, respectively (Figure 1). As for the resection only group, the overall survival rates at 1, 2, 3, and 4 years were 85.7%, 67.8%, 67.8%, and 67.8%, respectively (Figure 2). A total of two deaths resulted from treatment-related complications. One patient developed pneumonitis after administration of a single lipiodol I-131 dose of 1600 MBq and died 2 months later. Another patient developed radiation hepatitis and died of liver failure 5 months post-treatment with 2000 MBq of lipiodol I-131. This patient had well-preserved liver function (Child-Pugh A) prior to treatment albeit in the presence of cirrhosis. We could not identify any risk factors for radiation injury within patients.

Figure 1. .

Overall survival of all patients receiving adjuvant lipiodol I-131.

Figure 2. .

Overall survival of patients receiving adjuvant lipiodol I-131 post-liver resection only.

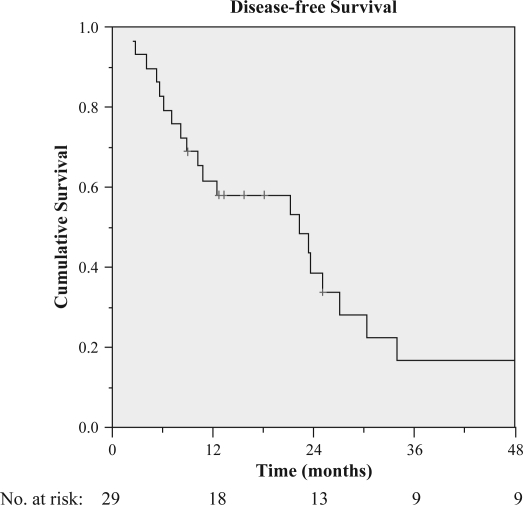

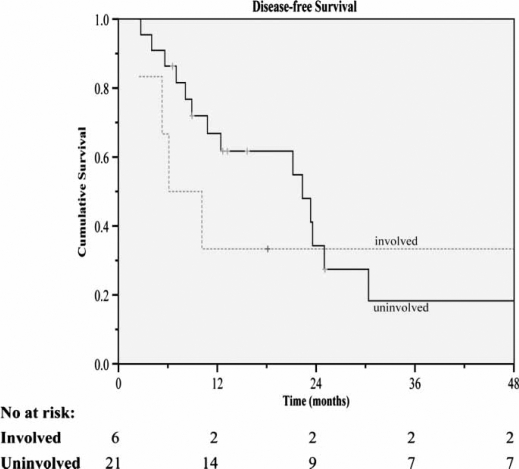

The two treatment-related deaths were excluded from DFS analysis. The DFS rates at 1, 2, 3, and 4 years were 61.7%, 38.7%, 16.9%, and 16.9%, respectively (Figure 3 ). Median time to recurrence was 22.3 months. Within the first postoperative year, tumor recurred in 11 patients. Three patients developed disseminated metastasis. Others with isolated recurrences developed disease progression within the liver (12 patients), lungs (4), bones (2), and pericardial lymph nodes (1). Intrahepatic recurrences were made up of 10 new lesions within the liver remnant and 2 on the edge of resection. Nine of them were further treated, with re-administration of lipiodol I-131 in 4 patients, repeat hepatectomy in 2, RFA in 2, and transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) in 2. On the other hand, extrahepatic metastases were managed with resection, radiotherapy, or systemic chemotherapy (Table III).

Figure 3. .

Disease-free survival rate of all patients receiving adjuvant lipiodol I-131.

Table III. Identified prognostic factors for different patterns of metastases and treatments for 22 patients who developed recurrences.

| Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|

| Intrahepatic metastases | 12 (54.5) |

| Microvascular involvement | 3 |

| Positive margin | 3 |

| Wedge resection | 1 |

| Tumor rupture | 0 |

| Cirrhosis | 5 |

| Multicentricity | 3 |

| Treatment of recurrence | |

| Resection | 1 (8) |

| RFA | 2 (17) |

| Lipiodol I-131 | 4 (33) |

| TACE | 2 (17) |

| No treatment | 3 (25) |

| Extrahepatic metastases | 7 (31.8) |

| Portal vein thrombosis | 2 |

| AFP ≥ 400 ng/ml | 2 |

| Intrahepatic metastases | 3 |

| Treatment of recurrence | |

| Resection | 1 (14) |

| Radiotherapy | 2 (29) |

| Chemotherapy 2 (29) | |

| No treatment | 2 (29) |

| Intra- and extrahepatic metastases | 3 (13.6) |

| Treatment of recurrence | |

| Resection | 1 (33) |

| No treatment | 2 (67) |

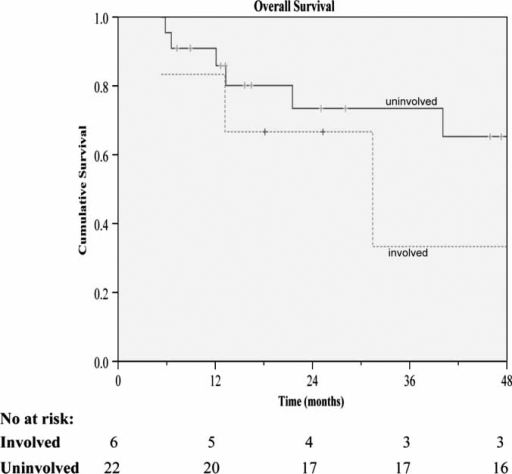

Figure 4. .

Overall survival for resections±ablation receiving adjuvant lipiodol I-131 according to microscopic tumor involvement of resection margins.

Figure 5. .

Disease-free survival for resections±ablation receiving adjuvant lipiodol I-131 according to microscopic tumor involvement of resection margins.

Further analysis of the influence on survival by microscopically positive margins was performed with the log rank test. Included in the analysis were a total of six positive cases. The overall median survival in the positive and negative margins of resection groups were 43.4 months and 60.7 months, respectively. The difference between groups, however, was not significant (p=0.42). The same goes for the median DFS (p=0.90), which, for the respective positive and negative resection margin groups, were 24.0 months and 33.8 months.

Discussion

In a search for studies on adjuvant lipiodol I-131, four were identified and are summarized in Table II13,14,15,16. Surgical resection was used in all four studies as the curative intervention. Our series was a mix of cryoablation and/or surgical resection. Cryoablation has been proven relatively effective and safe, and has a curative role 6,17,18. Zhou et al. achieved a 3-year survival rate of 50% in primary liver cancer (PLC) lesions up to 5 cm in diameter, although they later reported a lower rate of 40.3% in 78 PLCs with cryoablation 17,18. When used in conjunction with liver resection for complete tumor eradication, cryoablation can result in a 3-year survival rate of 52.6% 18. These results are similar to those of treatment with surgical resection alone; hence, justifying our inclusion of this locoregional therapy as a means of curative treatment. In addition, there are established methods of evaluating complete removal of tumors via ablation – ultrasonography for assessments of such is much easier with cryoablated lesions than those radiofrequency ablated. However, the use of adjuvant lipiodol I-131 in the post-ablative setting has not been reported previously.

Table II. Comparison of adjuvant lipiodol I-131 studies.

| Source | Lau et al. 13 | Partensky et al. 14 | Boucher et al. 15 | Tabone et al. 16 | Current study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study design | RCT | Phase II trial | Case-control | Case-control | Retrospective study |

| Lipiodol I-131 dose (MBq) | 1850 | 1110 | 2400 | 1100 | 1744.7±89.7 |

| Interval from surgery to lipiodol I-131 | 6–8 weeks | 3 (1–10) months | 8–12 weeks | 3.4 (2–4.5 months) | 1.9 (1.1–7.9) months |

| No. of patients treated | 21 | 28 | 38 | 10 | 34 |

| Males | 17 | 24 | 37 | 10 | 24 |

| Females | 4 | 4 | 1 | – | 10 |

| Age in years (median/mean) | 51.0 (23–71) | 61.5 (33–75) | 64±7.9 | 67.0 (51–76) | 60.4 (25–81) |

| Tumor size (cm) [median/mean] | 4.4 (1.4–11) | 5.5 (2.5–29.0) | 4.97±0.28 | 5.47 (1.7–10) | 8.0 (2.0–20.0) |

| Median AFP (ng/ml) | 147 (4–13300) | N/A | N/A | 33 (3.9–4584) | 12 (2–168 000) |

| Etiology | HBV | N/A | N/A | HCV | Various |

| Major liver resection (%) | 11 (52) | 18 (64) | 8 (21) | 3 (30) | 15 (48) |

| Cirrhosis | N/A | 7 | 29 | 10 | 15 |

| Vascular invasion | 1 | 2 | 14 | 5 | 16 |

| Positive margin | Nil | Nil | 2 | Nil | 7 |

| No. of recurrences | 6 | 12 | 9 | 6 | 22 |

| No. of deaths | 4 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 12 |

| Median follow-up duration (months) | 34.6 (14.1–69.7) | 51 (5–93) | 15 (minimum) | 38 | 23.3 (4.9–94.9) |

| Overall survival rate (%) | |||||

| 1-year | 90.5 | – | 94.7 | 100.0 | 87.1 |

| 2-year | – | – | 83.7 | 80.0 | 71.7 |

| 3-year | 84.8 | 86.0 | 68.4 | 80.0 | 60.7 |

| 4-year | – | – | – | – | 49.6 |

| 5-year | – | 65.0 | – | – | – |

| Median disease-free survival (months) | 57 | 28 | 16 | 25 | 22 |

| Disease-free survival rate (%) | |||||

| 1-year | 85.2 | – | 94.7 | 100.0 | 61.7 |

| 2-year | – | – | 91.7 | 80.0 | 38.7 |

| 3-year | 74.5 | – | 91.7 | 50.0 | 16.9 |

| 4-year | – | – | – | – | 16.9 |

| 5-year | – | 40.0 | – | – | – |

In the identified studies, variable single dosages of lipiodol I-131 were standardized for all patients irrespective of the extent of resection. While the prudent Italian regulation on radiation exposure allowed a dose of only 1100 MBq, the other studies also successfully achieved tumor effect at much higher dosages without radiation complications 13,14,15,16. In our attempt to tally the I-131 dose with postoperative functional remnant liver volume, two fatal complications arose in two patients with unidentified risk factors. One was among the three who underwent cryotherapy and one in a patient who had a major resection (major resections accounted for 48% of all resections). They each received 1600 and 2000 MBq of I-131.

It is widely known that recurrences after curative treatment of HCCs are the main cause of poor long-term survival. This is further influenced by their time of occurrence 10,19. The earlier the recurrence, the less favorable the outcome 9,10,11,19. However, the definition of early and late is dubious, with some drawing the line at 1 year and others at 2 years 9,10. Multiple studies have attempted to determine the factors predictive of the timing of recurrence and have found the presence of microvascular and macrovascular invasion, non-anatomical resections, serum α-FP ≥ 32 ng/ml, tumor rupture, and cirrhosis more vulnerable to developing recurrences early 9. The outcome of treatment of recurrence is variable 9,10. Of our 22 patients with disease progression, half recurred within the first postoperative year. Only two of them were eligible for potentially curative treatment with resection and radiofrequency ablation (RFA).

Compared to intrahepatic recurrences, the prevalence of extrahepatic metastases in general, is lower; the lungs being the most common site 20. Amid the unavailability of effective systemic treatment for this pattern of recurrence, we observed one patient treated with chemotherapy for lung disease at month 7 post-resection living for another 41.4 months thereafter. A similar scenario was observed in another patient who survived another 25 months after treatment of recurrence. New agents may also improve results. A recent randomized trial with sorafenib used to treat advanced HCCs had shown promising results 21.

Tumor size is another well-established adverse prognostic factor for recurrence and patient survival 22. Historically, large tumors were not surgically managed due to the associated high postoperative morbidity and mortality rates, as major hepatectomies are usually required and their prognosis is usually further worsened in the presence of cirrhosis 12. However, more recent studies show improved long-term survival rates ranging from 16% to 28% when managed aggressively 8,12. Also, their postoperative mortality rate is now comparable to that of lesions smaller than 5 cm 8. From our data, 6 of the 16 patients with lesions exceeding 8 cm were associated with cirrhosis. The actual median survival for patients with large tumors, defined as any lesions more than 8 cm in maximal diameter, was 45.9 months. One patient with a 13.0 cm lesion remained disease-free after 7.5 years post-right hepatectomy with a positive margin.

Large tumor size is also commonly accompanied by markedly elevated serum α-FP concentration 23,24. In fact, our data were contrary to this finding. Eight patients with lesions over 8 cm in size had α-FP levels below 400 ng/ml.

The effect of resection margin size in this cohort is negligible. A study from Germany showed that positive margins with CUSA resection had no influence on local recurrence, although it should be noted that this study looked at liver metastasis from colorectal carcinoma 25. The involvement of margin in a CUSA resection may still mean that there is a 1 cm or so real margin.

Compared with the other adjuvant lipiodol I-131 studies, several of our parameters had been identified to be within their range. These include the lipiodol dosage, interval from time of surgery to lipiodol I-131, age, proportion of major resection, and number of vascular invasions and cirrhosis (Table II). Nonetheless, we have a notable proportion of larger tumors, which may have played a significant role in the higher tumor recurrence rate and much poorer DFS rates of this study. The early recurrences may also have otherwise been attributed to HBV infections. Eleven of the HCCs diagnosed were HBV-related. This number could be higher, because etiology was indeterminate in 10 cases. However, our long-term survival rates were comparable in spite of 45% extrahepatic recurrence. Plus, analysis of the resection-only group showed a 4-year survival rate of 67.8%. It may be argued that treatment of recurrences might have contributed to the resulting good overall survival. However, there is evidence that such treatments have no impact at all 10. Moreover, only 5 patients (22.7%) within this study were eligible for potentially curative treatments (Table III).

Previous attempts at adjuvant therapy have included negative studies with oral carmofur (1-hexylcarbamoyl-5-fluorouracil (HCFU)) and a combination of uracil and tegafur 26,27. Postoperative TACE showed no benefits either 26,27,28. In addition, a study on preoperative TACE reduced the long-term survival 29. On the other hand, Muto et al. 30 reported reduction of multicentric recurrences with polyprenoic acid (retinoid) after surgical resection or percutaneous ethanol injection (PEI), but the effect on DFS was not significant. Later, an RCT using adoptive immunotherapy adjuvantly resulted in prolonged time to development of recurrence and improved DFS rates but not long-term survival 31. A more recent trial with adjuvant PI-88, a heparanase and VEGF activity inhibitor, also suggested similar benefits on disease progression 32. Suppression of viral replication with postoperative treatments using interferon α and β had successfully reduced the rate of recurrences in HBV and HCV-related HCCs, respectively 33,34,35.

Although the use of adjuvant lipiodol I-131 post-surgical treatments may not have prevented recurrences or prolonged the DFS, it has significantly improved the rates of intrahepatic recurrence. Compared to a study previously reporting an intrahepatic recurrence rate of 88% 22, our rates were much lower (Table III). In conclusion, our trial with adjuvant lipiodol I-131 has proven beneficial on overall survival in the short term.

References

- 1.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Mini review – Estimating the world cancer burden: Globocan 2000. Int J Cancer. 2001;94:153–6. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hong SS, Kim TK, Sung KB, Kim PN, Ha HK, Kim AY, et al. Extrahepatic spread of hepatocellular carcinoma: a pictorial review. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:874–82. doi: 10.1007/s00330-002-1519-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fan ST, Lo CM, Liu CL, Lam CM, Yuen WK, Yeung C, et al. Hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma: towards zero hospital death. Ann Surg. 1999;229:322–30. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199903000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El-Serag HB, Mason AC. Rising incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:745–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903113401001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Margarit C, Charco R, Hidalgo E, Allende H, Castells L, Bilbao I. Liver transplantation for malignant diseases: selection and pattern of recurrence. World J Surg. 2002;26:257–63. doi: 10.1007/s00268-001-0214-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adam R, Akpinar E, Joann M, Kunstlinger F, Majno P, Bismuth H. Place of cryosurgery in the treatment of malignant liver tumors. Ann Surg. 1997;225:39–49. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199701000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chu F, Morris DL. Single centre experience of liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients outside transplant criteria. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006;32:568–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yeh CN, Lee WC, Chen MF. Hepatic resection and prognosis for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma larger than 10 cm: two decades of experience at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:1070–6. doi: 10.1245/aso.2003.03.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Portolani N, Coniglio A, Ghidoni S, Giovanelli M, Benetti A, Tiberio GA, et al. Early and late recurrence after liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: prognostic and therapeutic implications. Ann Surg. 2006;243:229–35. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000197706.21803.a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poon RT, Fan ST, Ng IO, Lo CM, Liu CL, Wong J. Different risk factors and prognosis for early and late intrahepatic recurrence after resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2000;89:500–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shimada M, Takenaka K, Gion T, Fujiwara Y, Kajiyama K, Maeda T, et al. Prognosis of recurrence hepatocellular carcinoma: a 10-year surgical experience in Japan. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:720–6. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8780578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pandey D, Lee KH, Wai CT, Wagholikar G, Tan KC. Long-term outcome and prognostic factors for large hepatocellular carcinoma (10 cm or more) after surgical resection. Ann Surg. 2007;14:2817–23. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9518-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lau WY, Leung TW, Ho SK, Chan M, Machin D, Lau J, et al. Adjuvant intra-arterial lipiodol-iodine-131 for resectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;353:797–801. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)06475-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Partensky C, Sassolas G, Henry L, Paliard P, Maddern GJ. Intra-arterial iodine 131-labeled lipiodol as adjuvant therapy after curative liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Arch Surg. 2000;135:1298–300. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.135.11.1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boucher E, Corbinais S, Rolland Y, Bourguet P, Guyader D, Boudjema K, et al. Adjuvant intra-arterial injection of iodine-131-labeled lipiodol after resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2003;38:1237–41. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tabone M, Vigano L, Ferrero A, Pellerito R, Carbonatto P, Capussotti L. Prevention of intrahepatic recurrence by adjuvant 131iodine-labeled lipiodol after resection for hepatocellular carcinoma in HCV-related cirrhosis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006;33:61–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2006.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou XD, Tang ZY, Yu YQ, Ma ZC. Clinical evaluation of cryosurgery in the treatment of primary liver cancer: report of 60 cases. Cancer. 1988;61:1889–92. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19880501)61:9<1889::aid-cncr2820610928>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou XD, Tang ZY. Cryotherapy for primary liver cancer. Semin Surg Oncol. 1998;14:171–4. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2388(199803)14:2<171::aid-ssu9>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen WT, Chau GY, Lui WY, Tsay SH, King KL, Loong CC, et al. Recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatic resection: prognostic factors and long-term outcome. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2004;30:414–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2004.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang Y, Nagano H, Ota H, Morimoto O, Nakamura M, Wada H, et al. Patterns and clinicopathologic features of extrahepatic recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after curative resection. Surgery. 2007;151:196–202. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2006.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Llovet J, Ricci S, Mazzaffero V, Hilgard P, Raoul J, Zeuzem S, et al. Sorafenib improves survival in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): results of a phase III randomized placebo-controlled trial (SHARP trial) J Clin Oncol ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings Part I. 2007;25(18S):A1. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shah SA, Cleary SP, Wei AC, Yang I, Taylor BR, Hemming AW, et al. Recurrence after liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: risk factors, treatment, and outcomes. Surgery. 2007;141:330–9. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2006.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tangkijnavnich P, Anukulkarnkusol N, Suwangool P, Lertmaharit S, Hanvivatvong O, Kullavanijaya P, et al. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: analysis based on serum alpha-fetoprotein levels. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;31:302–8. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200012000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farinati F, Marino D, Giorgio M, Baldan A, Cantarini M, Cursaro C, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic role of a-fetoprotein in hepatocellular carcinoma: both or neither? Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:524–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bodingbauer M, Tamandl D, Schmid K, Plank C, Schima W, Gruenberger T. Size of surgical margin does not influence recurrence rates after curative liver resection for colorectal cancer liver metastases. Br J Surg. 2007;94:1133–8. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takenaka K, Yoshida K, Nishizaki T, Korenaga D, Hiroshige K, Ikeda T, et al. Postoperative prophylactic lipiodolization reduces the intrahepatic recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Surg. 1995;169:400–5. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)80184-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ono T, Yamanoi A, El-Assal ON, Kohna H, Nagasue N. Adjuvant chemotherapy after resection of hepatocellular carcinoma causes deterioration of long-term prognosis in cirrhotic patients: metaanalysis of three randomized controlled trials. Cancer. 2001;91:2378–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Izumi R, Shimizu K, Iyobe T, Ii T, Yagi M, Matsui O, et al. Postoperative adjuvant hepatic arterial infusion of lipiodol containing anticancer drugs in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 1994;20:295–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sasaki A, Iwashita Y, Shibata K, Ohta M, Kitano S, Mori M. Preoperative transcatheter arterial chemoembolization reduces long-term survival rate after hepatic resection for respectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006;32:773–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muto Y, Moriwaki H, Ninomiya M, Adachii S, Saito A, Takasaki KT, et al. Prevention of second primary tumours by an acyclic retinoid, polyprenoic acid, in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;334:1561–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199606133342402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takayama T, Sekine T, Makuuchi M, Yamasaki S, Kosuge T, Yamamoto J, et al. Adoptive immunotherapy to lower postsurgical recurrence rates of hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomized trial. Lancet. 2000;356:802–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02654-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gautam AM, Wilson EA, Chen PJ, Lee PH, Lin DY, Wu CC, et al. A novel heparanase inhibitor, as adjuvant therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: a large randomized phase II clinical trial. Proc AACR Ann Meet. 2007;232:2650. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun HC, Tang ZY, Wang L, Qin LX, Ma ZC, Ye QH, et al. Postoperative interferon a treatment postponed recurrence and improved overall survival in patients after curative resection of HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomized clinical trial. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2006;132:458–65. doi: 10.1007/s00432-006-0091-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ikeda K, Arase Y, Saitoh S, Kobayashi M, Suzuki Y, Suzuki F, et al. Interferon beta prevents recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after complete resection or ablation of the primary tumor – a prospective randomized study of hepatitis C virus-related liver cancer. Hepatology. 2000;32:228–32. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.9409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lo CM, Liu CL, Chan SC, Lam CM, Poon RT, Ng IO, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of postoperative adjuvant interferion therapy after resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2007;245:831–42. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000245829.00977.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]