Abstract

Pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD), once carried high morbidity and mortality, is now a routine operation performed for lesions arising from the pancreatico-duodenal complex. This study reviews the outcome of 101 pancreaticoduodenectomies performed after formalization of HepatoPancreatoBiliary (HPB) unit in the Department of Surgery.

A prospective database comprising of patients who underwent PD was set up in 1999. Retrospective data for patients operated between 1996 and 1999 was included. One hundred and one cases accrued over 10 years from 1996 to 2006 were analysed using SPSS (Version 12.0).

The mean age of our cohort of patients was 61±12 years with male to female ratio of 2:1. The commonest clinical presentations were obstructive jaundice (64%) and abdominal pain (47%). Majority had malignant lesions (86%) with invasive adenocarcinoma of the head of pancreas being the predominant histopathology (41%). Median operative time was 315 (180–945) minutes. Two-third of our patients had pancreaticojejunostomy (PJ) while the rest had pancreaticogastrostomy (PG). There were five patients with pancreatico-enteric anastomotic leak (5%), three of whom (3%) were from PJ anastomosis. Overall, in-hospital and 30-day mortality were both 3%. The median post-operative length of stay (LOS) was 15 days. Using logistic regressions, the post-operative morbidity predicts LOS following operation (p<0.005). The strategy in improving the morbidity and mortality rates of pancreaticoduodenectomies lies in the subspecialization of surgical services with regionalization of such complex surgeries to high volume centers. The key success lies in the dedication of staffs who continues to refine the clinical care pathway and standardize management protocol.

Keywords: pancreaticoduodenectomy, Whipple operation

Introduction

Since the first successful removal of a periampullary carcinoma with a sleeve of duodenum by William Halsted in 1898 1, many developments have taken place with significant improvement in outcome of pancreaticoduodenal surgery. Pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) was subsequently popularized by Dr Allen O. Whipple after his success in the initial three cases in 1935. He published the operation in a landmark paper and this is now commonly known as “Whipple's operation” 2.

Previously, this surgery was criticized by many as it carried high rates of morbidity and mortality 3. However, in recent years, the morbidity and mortality associated with PD have dropped significantly due to the development of subspecialization, regionalization of this complex operation and creation of high volume centers. Advancement in the operative techniques, improvement in peri-operative care and standardization of post-operative care using clinical care pathway have also contributed significantly to the improved outcome of this operation.

In our institution, we restructured and reorganized the Department of General Surgery into subspeciality-based surgical practice in 1996. Hepatopancreatobiliary (HPB) Surgery Unit was formalized and HPB surgeons and nurses were recruited. In the last decade, pancreaticoduodenectomy was performed by our HPB and upper gastrointestinal tract (UGIT) surgeons. This study analyses our institution's outcome with the 101 pancreaticoduodenectomies performed over the last 10 years.

Methods

A prospective database comprising of patients who underwent PD was set up in our institution in 1999. Through our hospital operation record book, we included retrospective data of patients operated between 1996 and 1999. From 1996 to 2006, a total of 101 pancreaticoduodenectomies were performed. The data was analysed using SPSS (Version 12.0) and Stata version 9.2 (Stata Corp, Texas, USA). We analysed the morbidity, mortality and length of stay (LOS) after surgery. The linear regression model was used to examine factors associated with LOS. We analyzed LOS on the natural logarithmic scale, as we found the residuals from the model to be not normally distributed. Logistic regression was used to identify predictors for morbidity and mortality. The data was also divided into two periods, from 1999 to 2001 and from 2002 to 2006 for comparison. Year 2002 was selected as the cut-off as it coincided with the year when HPB unit started implementing standardized management protocol in our institution.

Cases that are indicated for PD are discussed at our weekly multi-disciplinary Pancreato-Biliary Management Conference. Cases are deemed suitable for resection when there is no evidence of liver or peritoneal metastases, no gross involvement of major blood vessels. We would consider trial of resection of portal or superior mesenteric vein if pre-operative assessment showed close abutment of tumor to these veins and venous reconstruction was possible. Prior to operation, patients with significant cardiac and respiratory conditions are assessed by cardiologists and respiratory physicians respectively. All patients would then undergo pre-operative chest physiotherapy and incentive spirometry to minimize post-operative respiratory morbidity. Smokers are advised to cease smoking two weeks prior to the operation for the same reason mentioned above.

Prior to 2006, only classical Whipple's operation was performed in our institution. Pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (PPPD) was added to our operative repertoire in early 2006. Our classical Whipple's operation is defined as resection of distal third of stomach with transection of common hepatic duct just proximal to the junction with cystic duct. Lymph node clearance is confined to the hepatoduodenal ligament and retropancreatic areas up to superior mesenteric vessels 4,5. The posterior pancreatic resection margin is at the plane posterior to portal vein and lateral to superior mesenteric vessels. Jejunum is transected at the first jejunal mesenteric branch. The choice for the type of pancreatic-enteric anastomosis is based on surgeon's preference. End-to-side hepaticojejunostomy, about 10 cm distal to pancreaticojejunostomy, constructed using interrupted 4/0 or 5/0 Polydiaxanone (PDS® Ethicon, Inc, Johnson & Johnson) suture is our usual practice 6,7. Gastrojejunostomy is performed with an omega loop in end-to-side fashion. For PPPD, the distal stomach and pylorus are preserved and duodenojejunostomy is reconstructed with an antecolic omega jejunal loop, 70 cm from the hepaticojejunostomy.

A standard post-operative care pathway is used for post-operative management in the wards. Patients are kept nil by mouth with nasogasteric tube to passive drainage and aspiration at four hourly intervals. A single dose of 200 mcg of subcutaneous sandostatin is administered during pancreatic transection and this is continued for one week post-operatively. The dose is dependent on the consistency of the pancreatic tissue assessed during operation. If the pancreas is soft or pancreatic duct is <3 mm, 200 mcg at eight hourly dosing interval is administered, otherwise 100 mcg eight hourly is given 6. Patients are allowed non-milk feeds if nasogastric output is <100 ml on first post = operation day (POD) and nasogasteric tube is removed on second POD if the output remains <100 ml. Feeding is graduated as tolerated. In general, by third to fourth POD, patients will be taking full diet.

Drain fluid and serum amylase are performed on first, third and fifth POD. The drain fluids from surgical tubes placed in the subhepatic space and left infracolic compartment are assayed. We defined pancreatico-enteric anastomotic leakage when the drain fluid amylase level is more than 3X serum amylase and drainage from pancreatic bed is more than 100 ml per day from the fifth post-operative day 8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. All complications were documented clearly and graded according to the classification proposed by Clavien et al. in 1992. 17,18,19,20.

All histology specimens were examined and reported by our in-house pathologists. When the origin of the cancer at the ampullary region could not be convincingly demonstrated, peri-ampullary carcinoma is reported. Our post-discharge follow-up schedule comprises of three monthly clinic reviews in the first two years, half-yearly review in the subsequent three years and yearly follow-up if patient is disease free after five years from the surgery. Routine CT imaging is not mandatory unless patient is symptomatic or has elevated serum tumor marker level on follow-up.

Results

Demography

The mean age of our cohort of 101 patients was 61±12 years. Sixty-two percent were male. Seventy-eight percent of them were Chinese; Malay and Indian comprised 6% and 9%, respectively. Two-third of them had one or more comorbidities. The two most common comorbidities were hypertension (29%) and diabetes mellitus (18%). All the patients had ASA grade ≤3, slightly more than half (53%) of the patients were graded ASA 2.

Presentation and pre-operative procedure

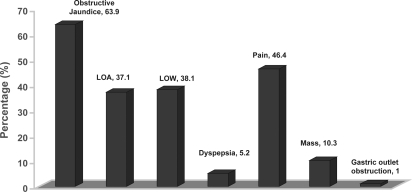

The commonest clinical presentations were obstructive jaundice (64%) and abdominal pain (47%) for a variety of diagnoses (Figure 1). Majority of patients had malignancy arising from the pancreaticoduodenal complex (83%).

Figure 1. .

Clinical presentation of patients prior to surgery.

About one-third of our patients underwent pre-operative endobiliary stenting (29%) for either infective or non-infective obstructive biliopathy. This represented half of our patients who presented with obstructive jaundice.

Operative data

All pancreaticoduodenectomies were performed by either HPB or UGIT surgeon in our institution. All were elective cases except for one patient who underwent emergency PD for a traumatic pancreatic transection following motor-vehicle accident. Ten patients (10%) underwent pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (PPPD).

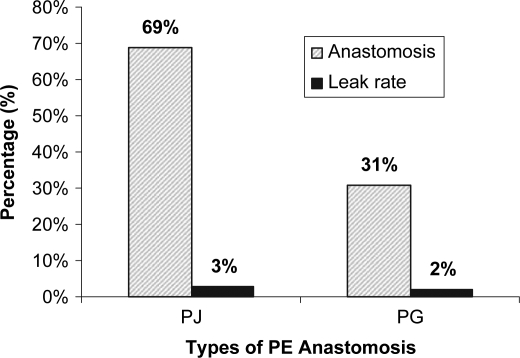

The median length of operation was 315 (180–945) minutes. The outlier of the operation duration was a man with chronic pancreatitis who developed carcinoma of the head of pancreas. Because of his two previous upper abdominal operaions and chronic pancreatitis, 3–4 hours were spent on adhesiolysis prior to pancreaticoduodenectomy. Median estimated intra-operative blood loss was 500 (150–6400) ml. The median blood transfusion was 1.6 (0–7.0) units. The same patient mentioned above had 6400 ml of intra-operative blood loss due to prolonged and extensive dissection. Two-third of our patients (69%) had pancreaticojejunostomy (PJ) while the rest (31%) had pancreaticogastrostomy (PG). Prior to 2003, subcutaneous sandostatin was administered selectively and this practice was embedded as part of our standardized peri-operative care protocol only from 2003 onwards.

Pathology

Malignancies arising from the head of pancreas (32%) and ampulla of Vater (32%) were the two commonest pathology (Table I). Seventy-two percent of them were moderately differentiated in histological grade. The median tumor size for malignant lesions was 27 (5–160) mm.

Table I. Pathological diagnoses of patients who underwent PD in our institution.

| Site of lesion | No. | (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Head of pancreas | |||

| Benign | Serous cystadenoma | 2 | |

| Mucinous cystadenoma | 1 | ||

| Cavernous lymphangioma | 1 | ||

| Inflammatory | Chronic pancreatitis | 4 | |

| Inflammatory pseudocyst | 1 | ||

| Malignant | IPMT | 4 | |

| Neuroendocrine tumour | 2 | ||

| Invasive adenocarcinoma | 32 | 46.6 | |

| Ampulla of Vater | |||

| Benign | Dysplastic adenoma | 2 | |

| Malignant | Invasive adenocarcinoma | 32 | 33.7 |

| Periampullary | |||

| Malignant | Invasive adenocarcinoma | 6 | 5.9 |

| Duodenal | |||

| Benign | AVM | 1 | |

| Malignant | Invasive adenocarcinoma | 5 | 5.9 |

| Distal CBD | |||

| Malignant | Cholangiocarcinoma | 3 | 3.0 |

| Others | 5 | 5.0 | |

Post-operative outcome

Most of the patients were monitored in the surgical high dependency (SHD) ward for a median of 3 (1–10) days. The median post-operative LOS was 11 (4–90) days. One-third (37%) of our patients had peri-operative morbidity. The majority of these are complications arising from wound infections, intra-abdominal complications, intestinal complications, bleeding, respiratory complications and anastomotic leak (Table II). Most of these morbidities were Grade 2 complications (24%). There were five pancreatico-enteric anastomotic leaks (5%) of which three (3%) were from PJ anastomosis (Figure 2). There was one bile leak from hepaticojejunostomy dehiscence.

Table II. Table of comparison for morbidities after PD surgery.

| n = 101 cases | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Wound complication | ||

| Wound infection | 4 | 4 |

| Burst abdomen | 1 | 1 |

| Intra-abdominal complication | ||

| Intra-abd sepsis | 5 | 5 |

| Peripancreatic collection | 1 | 1 |

| Other intra-abd collection | 3 | 3 |

| Anastomotic leak | ||

| PJ leak | 3 | 3 |

| PG leak | 2 | 2 |

| HJ leak | 1 | 1 |

| Intestinal complication | ||

| Ileus | 4 | 4 |

| Prolonged biliary to bowel transit | 1 | 1 |

| Delayed gastric emptying | 5 | 5 |

| IO – efferent loop partial obstruction | 1 | 1 |

| Gastric outlet obstruction | 1 | 1 |

| Dumping syndrome | 1 | 1 |

| Bleeding complication | ||

| BGIT | 3 | 3 |

| Intra-abd bleeding | 3 | 3 |

| Chest complication | ||

| Pneumonia | 4 | 4 |

| Pleural effusion | 3 | 3 |

| Pulmonary oedema | 1 | 1 |

| Prolonged ventilation | 2 | 2 |

| Atelectasis | 2 | 2 |

| Other complication | ||

| Enterocutaneous fistula | 1 | 1 |

Figure 2. .

Types of pancreaticoenteric anastomosis and anastomotic leak rate.

Eight patients (8%) in our series required unplanned re-operations within two weeks after PD due to various complications (Table III). Five re-operations were performed to address complications arising from anastomotic leak.

Table III. Reasons for repeat exploratory laparotomy in patients after pancreaticoduodenectomy.

| Operation and findings | |

|---|---|

| Anastomotic leak related | 1. PG leak with laparotomy and refashioning of PG and CJ/repair of burst abdomen |

| 2. Exploratory laparotomy and evacuation of hemoperitoneum | |

| 3. Take down of PJ, drainage of collection, revision of HJ | |

| 4. Take down of PG and partial gastrectomy | |

| 5. DJ stenting across HJ leak and T-tube | |

| Not related to leak | 6. Gastric outlet obstruction with laparotomy and adhesiolysis done |

| 7. Exploratory laparotomy for delayed gastric emptying | |

| 8. Resection of tumor margin due to tumor involvement |

Overall, in-hospital and 30-day mortality were both 3%. There were two mortalities, one from acute renal failure following postoperative sepsis, while another from acute myocardial infarction in the first week of operation. The third patient passed away from pancreaticoduodenal artery haemorrhage on the fifth post-operative day. The diagnosis was made promptly but patient adamantly declined surgical intervention after failed attempts at angiographic dearterialization.

Predictors of outcome

Using logistic regression, age (p>0.05) and gender (p>0.05) did not influence post-operative LOS (Table IV). However, the presence of any morbidity significantly prolongs the post-operative LOS (p<0.05). As the post-operative LOS was not normally distributed, log transformation was performed and subsequent linear regression showed that Grade 2 (p<0.001) and 3 (p=0.003) complications were significantly associated with longer post-operative LOS (Table V). When analyzing anastomotic leak as an independent variable, it did not significantly increase the LOS in Surgical Intensive Care Unit (SICU), SHD or post-op LOS (Table IV). This could be due to the small sample size in our cohort of patients.

Table IV. Predictors of outcome for pancreaticoduodenectomies.

| Variables | P-value |

|---|---|

| Post-op LOS vs. | |

| Age | 0.59 |

| Gender | 0.33 |

| Anastomotic Leak vs. | |

| Somatostatin administration | 0.40 |

| PJ vs. PG | 0.90 |

| SICU LOS | 0.56 |

| SHD LOS | 0.38 |

| Post-op LOS | 0.20 |

| Pre-op endobiliary stenting vs. | |

| Infective complication | 0.73 |

Note: P-value <0.05 as statistically significant. PJ, pancreaticojejunostomy; PG, pancreaticogastrostomy; SICU, Surgical Intensive Care Unit; SHD, Surgical High Dependency Unit; LOS, length of stay.

Table V. Linear regression of post-operative LOS vs. grade of complications (GOC).

| Log post-op LOS | P-value | Median | p25 | p75 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GOC Grade 0 vs | 9.5 | 8 | 12 | |

| GOC 1 | 0.056 | 17 | 11 | 31 |

| GOC 2 | <0.001 | 18 | 11.5 | 27.5 |

| GOC 3 | 0.003 | 17 | 9 | 41 |

| GOC 4 | 0.82 | 10 | 6.5 | 22 |

Note: p25, 25th percentile; p75, 75th percentile. GOC, Grade of complications based on Clavien et al. [17]. P-values obtained from linear regression model with LOS analyzed on the logarithmic scale.

In our series, the use of pre-operative endobiliary stent in obstructed biliary track was also not found to increase post-operative infective complications (p=0.73). However, low post-operative hemoglobin level (p=0.04) and elevated pre-operative (p=0.03) bilirubin level at presentation significantly correlated with higher morbidity. Although half of the patients had somatostatin analogue administration peri-operatively, this had not been shown to decrease the rate of anastomotic leak (p=0.40) (Table IV). We also did not find a significant difference in anastomotic leak rate between PJ and PG anastomosis techniques (p=0.90). Again, the small sample size is a plausible explanation to this observation.

Comparing outcomes of two periods

To analyze the outcome after standardized peri-operative PD management protocol was implemented in 2002, we divided the data into two periods, first five years (1996–2001) and second five years (2002–2006). While there were more PJ (n=37) than PG (n=7) performed after year 2002, there was no difference in terms of age, gender, race, ASA grade, operative time and intra-operative blood loss between the two periods.

Further analysis of this data using student's t-test showed that the LOS in terms of total LOS and post-operation LOS were significantly shorter for PD done after year 2002 (Table VI). Comparing the mortality and morbidity between these two periods, the mortality has dropped from 5 to 0% while overall morbidity dropped from 42 to 25%. The leak rate has also decreased from 7 to 2%. Using Fisher's exact test, these differences did not reached statistical significance.

Table VI. Comparison of LOS before and after year 2001.

| Median |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables (Days) | Before 2001 | After 2001 | P-value |

| LOS in SICU | 0 | 0 | 0.27 |

| LOS in HD | 3 | 3 | 0.84 |

| Total LOS | 20 | 10 | <0.001 |

| Post-op LOS | 13.5 | 9 | 0.001 |

(p<0.05 as statistically significant)

Discussion

Operative outcomes of pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) have been widely published in the western countries in the past decade but literatures from Asian centers are limited. There is paucity of outcome data for Whipple's operation in Singapore. In this study, we share our one decade of experience in pancreaticoduodenectomy and review the outcome of PD in a tertiary teaching hospital.

In our institution, this operation was initially performed by general surgeons. However, as we progress toward subspecialization, this operation is now commonly performed by specialized trained HPB surgical team since 1996 in our institution. This trend is in tandem with the global phenomenon of subspecialty-based surgical practice and regionalization of major and complex operations to high-volume centers 21. This has resulted in significant improvement in mortality and morbidity rates. Singapore is a small island country with an average population of about three million people. With the influx of immigrants after the millennium, the population now is about four million people. Our hospital has a healthcare catchment area of 1–1.5 million of people, serving the Northern and North-eastern part of the country.

Our overall in-hospital and 30-day mortality rate of 3% is comparable to other specialized centers in this region. Poon et al. from Hong Kong reported a hospital mortality rate of 2.9% in 140 patients over a 12-year- period 22. Simliarly, these numbers were also consistent with the mortality rate quoted from various high-volume centers around the world 23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32. Birkmeyer et al. noticed that there was a trend toward regionalizing pancreaticoduodenectomy to high-volume centers in the USA due to better results and lower in-hospital mortality rate. They divided the hospital's average annual volume of pancreatocoduodenectomies into four categories: very low (<1/year), low (<1–2/year), medium (2–5/year) and high (>5/year). They observed that in-hospital mortality rates at low and very low-volume hospitals were three to fourfold higher than at high-volume hospitals 31. This was supported by Gordon et al who found that centers with high volume (>20 cases per year) had lower mortality rate for PD at 2.2% while low-volume centre (1–5 cases per year) had higher mortality rate at 19.1% 32. By Birkmeyer's definition, our institution falls into the high-volume center (medium volume by Gordon's definition), and the mortality rate correlates well with the operative volume.

Many high-volume centers reported overall morbidity rate of PD of about 41–50% 22,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41. In our series, 35% of our patients had one or more morbidities and this was again comparable to that reported by Poon et al. from Hong Kong (38.6%) 22. Majority of our morbidity was grade 2 complication. However, implementation of a standardized management protocol and care pathway has been shown to significantly decrease the risk of complications. Many centers have shown that protocolized management by an experienced team comprising of surgeons, nurses and anesthesia medical staffs can effectively improve clinical outcome. In specialized centers, post-operative and overall LOS decreased with increased experience of the specialized team. Operation performed by a dedicated team helps to minimize leak rate and shorten LOS. This is due to familiarity with the operation and better surgical techniques.

As mentioned earlier, the choice of pancreatico-enteric anastomosis, i.e. PJ or PG, is entirely based on surgeon preference in our center. Randomized controlled trials revealed no significant difference between PJ and PG regarding overall postoperative complications, pancreatic fistula, intra-abdominal collection or mortality 42,43,44. Although non-randomized observational clinical studies showed significant results in favor of PG in terms of reduction in pancreatic fistula and mortality rate 45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57, meta-analysis concluded no significant difference between the two techniques 58,59. In our series, we did not observe any difference in outcome between PJ and PG.

The other strength of a matured surgical team is that, as the team gathers more experience and momentum in performing PD, it allows them to explore and introduce improved modifications to the techniques of Whipple's operation. Over the years, there have been many creative modifications to performing PD. One such technique that has gained popularity as well as controversy is the pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (PPPD). Our institution started to perform this operation in early 2006, nine years after our subspecialized hepatobiliary surgery service was formalised. We have also developed new modifications to the technique of pancreatic anastomosis as we continue to explore this operation. Our current preferred PJ technique is duct-to-mucosa in two layers.

Our 10 years of audited data has helped us to reshape the patient care protocol and refine the surgical techniques required in performing PD. As we strive to improve the outcome of our patients undergoing PD, we periodically review our database to explore further opportunity to improve our surgical techniques and care protocol. With the management protocol that was implemented, the outcome has improved remarkably.

Conclusion

The strategy in improving the morbidity and mortality rates of pancreaticoduodenectomies lies in the subspecialisation of surgical services with regionalization of such complex surgeries to high-volume centers. The key success lies in the dedication of staffs who continue to refine the clinical care pathway and standardize management protocol. Given such safety profile, it is therefore justified to extend the indication of PD to benign conditions and presumed malignant pathology arising from pancreaticoduodenal complex.

References

- 1.Halsted WS. Contributions to the surgery of the bile passages, especially of the common bile duct. Boston Med Surg J. 1899;141:645–54. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whipple AO, Parsons WB, Mullins CR. Treatment of carcinoma of ampulla of Vater. Ann Surg. 1935;102:763–79. doi: 10.1097/00000658-193510000-00023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janes RH, Niederhuber JE, Chmiel JS, Winchester DP, Ocwieja KC, Karnell LH. National patterns of care for pancreatic cancer: results of a survey by the commission on cancer. Ann Surg. 1996;223:268–72. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199603000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pedrazzoli S, Beger HG, Obertop H, Andren-Sandberg A, Fernandez-Cruz L, Henne-Bruns D. A surgical and pathological based classification of resective treatment of pancreatic cancer. Summary of an international workshop on surgical procedures in pancreatic cancer. Dig Surg. 1999;16:337–45. doi: 10.1159/000018744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ishikawa O, Ohhigashi H, Sasaki Y, Kabuto T, Fukuda I, Furukawa H. Practical usefulness of lymphatic and connective tissue clearance for the carcinoma of the pancreas head. Ann Surg. 1998;208:215–20. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198808000-00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friess H, Ho CK, Kleeff J, Buchler MW. 2007. Pancreaticoduodenectomy, distal pancreatectomy, segmental pancreatectomy, total pancreatectomy, and transduodenal resection of the papilla of Vater: surgery of the liver, biliary tract, and pancreas. Fourth Edition. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Warshaw A, Thayer SP. Pancreaticoduodenectomy: how I do it. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8(6):733–41. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, et al. For the international study group on pancreatic fistula definition. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surg. 2005;138(1):8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schinchi H, Wada K, Traverso W. The usefulness of drain data to identify a clinically relevant pancreatic anastomotic leak after pancreaticoduodenectomy? J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10(4):490–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2005.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aranha GV, Aaron JM, Shoup M, Pickleman J. Current management of pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surg. 2006;140(4):561–9. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cullen JJ, Sarr MG, Ilstrup DM. Pancreatic anastomotic leak after pancreaticoduodenectomy: incidence, significance and management. The Am J of Surg. 1994;168:295–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80151-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poon RTP, Lo SH, Fong D, Fan ST, Wong J. Prevention of pancreatic anastomotic leak after pancreaticoduodenectomy. The Am J of Surg. 2002;183:42–52. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00829-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grobmyer SR, Rivadeneira DE, Goodman CA, Mackrell P, Lieberman MD, Daly JM. Pancreatic anastomotic failure after pancreaticoduodenectomy. The Am J of Surg. 2000;180:117–20. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(00)00423-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shrikhande SV, Qureshi SS, Rakneesh N, Shukla PJ. Pancreatic anastomoses after pancreaticoduodenectomy: do we need further studies? World J of Surg. 2005;29:1642–849. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0137-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kazanjian KK, Hines OJ, Eibl G, Reber HA. Management of pancreatic fistulas after pancreaticoduodenectomy: results in 437 consecutive patients. Arch of Surg. 2005;140:849–55. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.140.9.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ho CK, Kleeff J, Friess H, Buchler MW. Complications of pancreatic surgery. HPB. 2005;7:99–108. doi: 10.1080/13651820510028936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clavien P, Sanabria J, Strasberg S. Proposed classification of complication of surgery with examples of utility in cholecystectomy. Surg. 1992;111:518–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clavien P, Sanabria J, Mentha G. Recent results of elective open cholecystectomy in a North American and a European center. Ann Surg. 1992;216:618–26. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199212000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clavien P, Camargo C, Croxford R. Definition and classification of negative outcomes in solid organ transplantation. Ann Surg. 1994;220:109–20. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199408000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien P. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240(2):205–13. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson EVA. Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1128–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poon RTP, Fan ST, Chu KM, Poon JTC, Wong J. Standards of pancreaticoduodenectomy in a tertiary referral centre in Hong Kong: retrospective case series. Hong Kong Med J. 2002;8(4):249–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Winter JM, Cameron JL, Campbell KA, Arnold MA, Chang DC, Coleman J, et al. 1423 pancreaticoduodenectomies for pancreatic cancer: a single-institution experience. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10(9):1199–211. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2006.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chew DKW, Attiyeh FF. Experience with the Whipple procedure (Pancreaticoduodenectomy) in a University-affliated community hospital. The Am J of Surg. 1997;174:312–15. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(97)00110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crist DW, Sitzmann JV, Cameron JL. Improved hospital morbidity, mortality and survival after the Whipple procedure. Ann Surg. 1997;206(3):358–65. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198709000-00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lieberman MD, Kilburn H, Lindsey M, Brennan MF. Relationship of perioperative deanths to hospital volume among patients undergoing pancreatic resection for malignancy. Ann Surg. 1995;222(5):638–45. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199511000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sosa JA, Bowman HM, Gordon TA, Bass EB, Yeo CJ, Lillemoe KD, et al. Importance of hospital volume in the overall management of pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg. 1998;228(3):429–38. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199809000-00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neoptolemos JP, Russel RCG, Bramhale S. Low mortality following resection for pancreatic and periampullary tumours in 1026 patients. Br J Surg. 1997;84:1370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Afsari A, Zhangdoug Z, Young S, Feruson L, Silapaswam S, Mittal V. Outcome analysis of pancreaticoduodenectomy at a community hospital. Am Surg. 2002;68(3):281–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Birkmeyer JD, Stukel TA, Siewers AE, Goodney PP, Wennberg DE, Lucas FL. Surgeon volume and operative mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;329(22):2117–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa035205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Birkmeyer JD, Finlayson SRG, Tosteson ANA, Sharp SM, Warshaw AL, Fisher ES. Effect of hospital volume on in-hospital mortality with pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surg. 1998;125(3):250–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gordon TA, Burleyson GP, Tielsch JM, Cameron JL. The effects of regionalization on cost and outcome for one general high-risk surgical procedure. Ann Surg. 1995;221(1):43–9. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199501000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trede M, Schwall G, Saeger HD. Survival after pancreatoduodenectomy: 118 consecutive resections without an operative mortality. Ann Surg. 1990;221:447–58. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199004000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fernandez DC, Rattner DW., Warshaw AL. Standards for pancreatic cancer resection in the 1990s. Arch Surg. 1995;130:295–300. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1995.01430030065013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Imperato PJ, Nenner RP, Starr HA, Will TO., Rosenberg CR, Dearie MB. The effects of regionalization on clinical outcomes for a high-risk surgical procedure: a study of the Whipple procedure in New York State. Am J Med Qual. 1996;11:193–7. doi: 10.1177/0885713X9601100407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gouma DJ, van Geenen RCI, van Gulik TM, de Haan RJ, de Wit LT, Busch ORC, Obertop H. Rates of complications and death after pancreaticoduodenectomies: risk factors and the impact of hospital volume. Ann Surg. 2000;232(6):786–95. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200012000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cameron JL, Riall TS, Coleman J, Belcher KA. One thousand consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies. Ann Surg. 2006;244(1):10–15. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000217673.04165.ea. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miedema BW, Sarr MG, van Heerden JA, Nagorney DM, McIlrath DC, Ilstrup D. Complications following pancreaticoduodenectomy. Current management. Arch of Surg. 1992;127(8):945–949. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1992.01420080079012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Sohn TA, Lillimoe KD, Pitt HA, Talamini MA, et al. Six hundred fifty consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies in the 1990s. Ann Surg. 1997;226(3):248–57. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199709000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schimdt CM, Powell ES, Yiannoutsos CT, Howard TJ, Wiebke EA, Wiesernauer CA, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy: a 20-year experience in 516 patients. Arch Surg. 2004;139:718–27. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.7.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dimick JB, Pronovost PJ, Cowan JA., Jr., Lipsett PA, Stanley JC, Upchurch GR., Jr. Variation in postoperative complication rates after high-risk surgery in the United States. Surg. 2003;134:534–41. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(03)00273-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Maher MM. A prospective randomized trial of pancreaticogastrostomy versus pancreaticojejunostomy after PD. Ann Surg. 1995;222:580–8. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199510000-00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Duffas JP, Suc B, Msika S. A controlled randomized multicenter trial of pancreaticogastrostomy or pancreaticojejunostomy after PD. Am J Surg. 2005;189:720–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bassi C, Falconi M, Molinari E. Reconstruction by pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy following pancreatectomy: results of a comparative study. Ann Surg. 2005;242:767–71. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000189124.47589.6d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ramesh H, Thomas PG. Pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy in reconstruction following PD. Aust N Z J Surg. 1990;60:973–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1990.tb07516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miyagawa S, Makuuchi M, Lygidakis NJ. A retrospective comparative study of reconstructive methods following PD – pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy. Hepatogastroenterol. 1992;39:381–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morris DM, Ford RS. Pancreaticogastrostomy: preferred reconstruction for Whipple resection. J Surg Res. 1993;54:122–25. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1993.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mason GR, Freeark RJ. Current experience with pancreatogastrostomy. Am J Surg. 1995;169:217–9. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(99)80140-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gvalani AK. Pancreaticogastrostomy versus pancreaticojejunostomy following PD for periampullary carcinoma. Indiana J Gastroenterol. 1996;15:132–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim SW, Youk EG, Park YH. Comparison of pancreaticogastrostomy and pancreaticojejunostomy after PD performed by one surgeon. World J Surg. 1997;21:640–3. doi: 10.1007/s002689900286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Arnaud JP, Tuech JJ, Cervi C, Bergamaschi R. Pancreaticogastrostomy compared with pancreaticojejunostomy after PD. Eur J Surg. 1999;165:357–62. doi: 10.1080/110241599750006901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Takano S, Ito Y, Watanabe Y. Pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy in reconstruction following PD. Br J Surg. 2000;87:423–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fujino Y, Suzuki Y, Ajiki T. Risk factors influencing pancreatic leakage and the mortality after PD in a medium-volume hospital. Hepatogastroenterol. 2002;49:1124–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schlitt HJ, Schimdt U, Simunec D. Morbidity and mortality associated with pancreatigastrostomy and pancreatojejunostomy following partial pancreaticoduodenectomy. Br J Surg. 2002;89:1245–51. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aranha GV, Hodul P, Golts E. A comparison of pancreaticogastrostomy and pancreaticojejunostomy following PD. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:672–82. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(02)00432-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hoshal VL, Benedict MB, David LR, Kulick J. Personal experience with the Whipple operation: outcomes and lessons learned. Am Surg. 2004;70:121–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oussoultzoglou E, Bachellier P, Bigourdan JM. Pancreaticogastrostomy decreased relaparotomy caused by pancreatic fistula after PD compared with pancreaticojejunostomy. Arch Surg. 2004;139:327–35. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wente MN, Shrikhande SV, Müller MW, Diener MK, Seiler CM, Friess H, Büchler MW. Pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy: systematic review and meta-analysis. The Am J of Surg. 2007;193:171–83. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McKay A, Mackenzie S, Sutherland FR, Bathe OF, Doig C, Dort J, Vollmer CM, Dixon E. Meta-analysis of pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy reconstruction after pancreaticoduodenectomy. BJS. 2006;93:929–36. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]