Abstract

Objective

Instability of ocular alignment may cause surgeons to delay surgical correction of childhood esotropia. We investigated the stability of ocular alignment over 18 weeks in children with infantile esotropia (IET), acquired non-accommodative esotropia (ANAET), or acquired partially-accommodative esotropia (APAET).

Design

Prospective observational study

Participants

Two hundred thirty-three children aged 2 months to <5 years with IET, ANAET, or APAET of less than 6 months duration

Methods

Ocular alignment was measured at baseline and at six-week intervals for 18 weeks.

Main Outcome Measure

Using definitions derived from a nested test-retest study and computer simulation modeling, ocular alignment was classified as ‘unstable’ if there was a change of ≥ 15 prism diopters (PD) between any two of the four measurements, as ‘stable’ if all four measurements were within ≤ 5 PD of one another, or as ‘uncertain’ if neither criteria was met.

Results

Of those who completed all three follow-up visits within time windows for analysis, 27 (46%) of 59 subjects with IET had ocular alignment classified as unstable (95% confidence interval (CI) = 33 to 59%), 20% as stable (95% CI = 11 to 33%), and 34% as uncertain (95% CI = 22 to 47%). Thirteen (22%) of 60 subjects with ANAET had ocular alignment classified as unstable (95% confidence interval (CI) = 12 to 34%), 37% as stable (95% CI = 25 to 50%), and 42% as uncertain (95% CI = 29 to 55%). Six (15%) of 41 subjects with APAET had ocular alignment classified as unstable (95% CI = 6 to 29%), 39% as stable (95% CI = 24 to 56%), and 46% as uncertain (95% CI = 31 to 63%). For IET, subjects who were older at presentation were less likely to have unstable angles than subjects who were younger at presentation (risk ratio for unstable vs. stable per additional month of age = 0.85, 99% CI = 0.74 to 0.99).

Conclusions

Ocular alignment instability is common in children with IET, ANAET and APAET. The impact of this finding on the optimal timing for strabismus surgery in childhood esotropia awaits further study.

Introduction

Three types of childhood esotropia often requiring surgery are infantile esotropia (IET), acquired non-accommodative esotropia (ANAET) and acquired partially-accommodative esotropia (APAET). IET is defined as an esotropia with onset prior to 6 months and which is not fully accommodative. ANAET is an esodeviation that develops at 6 months of age or later in a child whose alignment does not improve significantly with hypermetropic refractive correction. APAET is defined in this study as an esodeviation that develops at 6 months of age or later in a child whose alignment responds partially to hypermetropic spectacle correction but for whom there is a residual deviation of at least 10 prism diopters (PD). A recent population-based retrospective study of esotropia type indicated that 8.1% of children with esotropia have IET, 16.6% have ANAET and 10.1% have APAET.1

The optimum timing of surgery for these three types of esotropia is controversial. Early surgery to minimize the duration of misalignment has been associated with better sensory and motor outcomes, particularly in infantile esotropia.2-8 Nevertheless, there may be reluctance to operate within weeks of presentation if there is a high likelihood that the ocular alignment may change substantially over time.9 In subjects with unstable ocular alignment, it is possible that waiting for stability might result in better motor alignment after surgery and better long-term sensory outcomes.

Randomized clinical trials to address the optimal timing of initial surgery in children with IET, ANAET or APAET might involve randomization to immediate surgery for the angle at presentation versus delayed surgery after stability of angle has been confirmed. As a prelude to designing such randomized trials, it is important to know 1) how often the angle of misalignment is unstable and 2) whether children could be enrolled early enough in the disease course so that the immediate and delayed treatment groups would be sufficiently different in terms of total duration of constant misalignment. The present study provides prospective data to address these issues.

Subjects and Methods

The Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group (PEDIG) conducted this study at 35 community- and university-based clinical sites, with funding provided through a cooperative agreement with the National Eye Institute of the National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services. The respective institutional review boards approved the protocol and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act-compliant informed consent forms. The parent or guardian of each study participant gave written informed consent. The major aspects of the protocol are summarized herein. The complete protocol is available at http://public.pedig.jaeb.org (date accessed: 5/20/08).

The major eligibility criteria included age 2 months to less than 5 years, no prior extraocular muscle surgery or intraocular surgery, a constant esotropia (in contrast to intermittent esotropia) with onset in the preceding 6 months, and willingness of the investigator and parent to wait at least 18 weeks before performing surgery. The esotropia was required to be between 20 and 50 PD in subjects who had IET, defined as esotropia with onset before 6 months of age, and between 15 and 50 PD in subjects who had acquired esotropia (AET), defined as onset at 6 months of age or later. Ocular alignment was measured in primary position at near fixation using the prism and alternate cover test (PACT) or by using a modified Krimsky test in subjects in whom PACT could not be completed. Subjects with IET were required to have no history of spectacle wear. AET subjects who had significant refractive error (as defined below) were required to have been wearing the full hyperopic correction, determined by cycloplegic refraction, for at least 2 weeks prior to enrollment. Major exclusion criteria included prematurity (defined as less than 34 weeks gestational age), significant developmental delay, or any known neurological disease.

All ocular alignment measurements were taken by study-certified examiners. Measurements were taken with spectacles if the subject was wearing spectacles. Acquired esotropia subjects who were wearing spectacles also had a PACT measurement performed a second time at the enrollment visit, but without spectacles, in order to classify the esotropia as ANAET or APAET. Acquired esotropia subjects whose angle of esotropia decreased less than 10 prism diopters (PD) by PACT while wearing refractive correction and those who did not require spectacle correction were classified as having ANAET whereas subjects whose angle of esotropia decreased 10 or more PD by PACT while wearing refractive correction were classified as having APAET.

The duration of constant esotropia at enrollment was recorded as the investigator's best estimate based on discussion with the parents and on additional documentation (if available) such as photographs and reports from other clinicians. If a deviation was intermittent prior to becoming constant, this period of intermittency was not counted towards duration. Also, because it is often not clear whether esotropia presenting in the first two months of life is truly pathologic, as it often resolves spontaneously,9 the time period with esotropia prior to 2 months of age was not counted in the duration determination.

Additional assessments performed at enrollment were an ocular motor examination and an assessment for presence of amblyopia. A cycloplegic refraction was performed at enrollment or within the two prior months. Significant refractive error was defined as the cycloplegic refraction indicating one or more of the following: 1) spherical equivalent in one or both eyes: ≥+3.00 D for subjects with IET and ≥+2.00 D for subjects with AET, 2) astigmatism in one or both eyes: ≥ +3.50 D for subjects with IET and ≥ +2.50 D for subjects with AET, or 3) anisometropia ≥ 2.00 D in spherical equivalent. At enrollment, subjects with IET who had significant refractive error were prescribed spectacles with the full cycloplegic refraction. Such subjects returned in 2 weeks and had the same ocular alignment measurements as were taken at enrollment, but while wearing the new spectacles, with the results of this later visit being considered the baseline alignment for the study.

The 18 weeks following the baseline visit served as the protocol-specified observation period during which esotropia surgery could not be performed. During this period, subjects had follow-up visits every 6 weeks (±1 week). Each follow-up visit included alignment measurement, an ocular motor examination, and an assessment of fixation preference. Throughout follow up, alignment measurements were to be taken by the same examiner who took the enrollment measurements (usually the investigator) and without reviewing the subject's alignment history in advance. For each subject, alignment was measured using the same method(s) as at baseline and with the subject wearing the same correction as at baseline (if applicable). During the 18-week observation period, spectacle correction could not be changed, discontinued, or initiated.

Presence of amblyopia was assessed at each visit by optotype visual acuity if possible, with amblyopia considered present if two logMAR lines or more difference existed in visual acuity between the eyes. An assessment of fixation preference was made to determine presence of amblyopia in subjects in whom optotype testing was not possible. The examiner recorded whether fixation preference was present and if it was, whether the non-preferred eye maintained fixation for a) <1 second, b) 1 to <3 seconds, or c) ≥3 seconds or through a blink or through a smooth pursuit. Amblyopia was considered present if the subject was unable to maintain fixation with the non-preferred eye for ≥3 seconds or through a blink or through a smooth pursuit. Subjects who had amblyopia upon entering the study or who developed amblyopia during the study could be treated with patching at investigator discretion but neither atropine nor any other amblyopia treatment other than patching and spectacles (if already worn) could be used.

Alignment Testing Procedures

Measurements of alignment were taken in the primary position at near fixation by PACT or if PACT testing was not possible, by a modified Krimsky test. For the PACT, examiners placed a plastic prism in the frontal plane position before one eye and alternately occluded the eyes with a cover, observing the re-fixation movement of the just-uncovered eye on an accommodative target. The amount of prism was gradually increased until the direction of the re-fixation movement of the just-uncovered eye reversed. The prism power was then reduced until no re-fixation movement of the fellow eye was seen (i.e., neutralization). The magnitude of prism that either neutralized the deviation or was closest to neutralization was recorded. If the esotropia was constant but the angle varied during testing, at either distance or near fixation, the investigator recorded the alignment as “variable.” For deviations greater than 50 PD, examiners split the prisms between eyes such that the prism power was approximately equal over each eye. For the modified Krimsky measurement, using a light at 1/3 meter, prisms of increasing power were placed before the fixating eye until the corneal light reflex was symmetrical to that of the corneal light reflex seen in fixating eye. In addition to the standard prism set, additional prisms of 22.5 PD, 27.5 PD, 32.5 PD, 37.5 PD, 42.5 PD, and 47.5 PD were manufactured for use in the study, allowing the measurements to be made to the nearest 2.5 PD for angles of esotropia measuring over 20 PD (Gulden Ophthalmics, Elkins Park, PA).

The ocular motor examination included version testing with attention to incomitance such as “A,” “V,” “Y,” ‘lambda,” or “X” patterns and assessment for presence of inferior oblique muscle overaction, superior oblique muscle overaction, vertical deviation, dissociated vertical deviation, and nystagmus.

Classification of Stability

Ocular alignment over the 18-week observation period was classified as stable, unstable, or uncertain. The definitions for this classification were based on test-retest data collected as part of the study, (PEDIG, unpublished data; Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 49 [E-Abstract]:1804, 2008) which found the 95% limits of agreement for a difference between PACT measurements at near to be ±11.7 PD for angles larger than 20 PD and to be ±4.7 PD for angles between 10 and 20 PD (PEDIG, unpublished data). We then conducted 10,000 Monte Carlo computer simulations for subjects with “no ocular alignment change” over 4 visits where the only changes in ocular alignment would be due to measurement error sampled from a distribution of measurement errors (Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 49 [E-Abstract]:1804, 2008). Additional simulations were conducted for a “defined ocular alignment change” (10,000 simulations each for changes of 5 PD, 10 PD, 15 PD and 20 PD) over 4 visits, where the changes in ocular alignment were modeled as the sum of measurement error and actual change (Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 49 [E-Abstract]:1804, 2008). We then estimated sensitivities and specificities for specific pragmatic classification rules for stability and instability (all measurements within 5 PD, or 10 PD, or 15 PD, or 20 PD) (Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 49 [E-Abstract]:1804, 2008). For the current 18-week observation study, we wanted the rate of false positives for classifying subjects as ‘stable’ or ‘unstable’ to be less than 20%. Based on the simulation data and on our goal to minimize false positive classifications, the following definitions were established: if the absolute value of the difference between the largest and smallest of the four measurements obtained was within 5 PD inclusive, the subject's ocular alignment was classified as stable; if it was 15 PD or greater, the subject's ocular alignment was classified as unstable; and if neither of these criteria were met, the subject's ocular alignment was classified as uncertain (Table 1). The rule for stability was estimated to have >=85% specificity for ocular alignment changes of ±10 PD or more, and sensitivity of 43% (Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 49 [E-Abstract]:1804, 2008). The rule for instability was estimated to have a sensitivity of >=46% for ocular alignment changes of ±15 PD or more and a specificity of 87% (Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 49 [E-Abstract]:1804, 2008).

Table 1. Definitions of Ocular Alignment Classification.

| Classification | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Stable | If the absolute value of the difference between the largest and smallest measurement over the four visits was less than or equal to 5 PD |

| Unstable | If the absolute value of the difference between the largest and smallest measurement over the four visits was greater than or equal to 15 PD |

| Uncertain | If neither stable nor unstable |

PD = prism diopter

Statistical Methods

Point estimates for the probability of ocular alignment being classified as stable, uncertain, or unstable were calculated along with 95% confidence intervals. Subjects were included in the analyses if they completed all three follow-up visits, had the 6-week and 12-week visits performed within ±3 weeks, had the 18-week visit performed between 15 weeks and 24 weeks, and if the measurements were taken by the same method as at baseline with the subject wearing the same spectacle correction as at baseline.

Risk ratios and 99% confidence intervals were calculated using Poisson regression models with robust variance estimation10 to evaluate for the association of baseline factors with the probability that subjects' ocular alignment was classified as unstable versus stable. Given that numerous factors were evaluated, the 99% confidence level was used instead of 95% to reduce the chance of making a Type 1 error (i.e., detecting an association where no association truly exists). A risk ratio was considered statistically significant if the 99% confidence interval excluded the value 1.00, a value that indicates no difference in risk of instability vs. stability between the two levels of the factor. Subjects whose ocular alignment stability was classified as uncertain were not included in these analyses. Duration of esotropia at baseline was evaluated as a continuous variable, and age and angle size were evaluated as both continuous and categorical variables. Factors were assessed in unadjusted models using the factor as the only covariate, and in adjusted models with the factor of interest and any factor that was associated with the risk of stability vs. instability.

All analyses were conducted separately for subjects with IET, ANAET, and APAET. All reported P values are two-tailed. Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Between June 2004 and May 2007, 233 subjects with ET of less than 6 months duration were enrolled in the study at 35 clinical centers: 81 with IET, 94 with ANAET, and 58 with APAET. The mean age was 6.0 months ± 1.7 for subjects with IET, 27.1 ± 12.0 months for subjects with ANAET and 30.1 ± 13.3 months for subjects with APAET. The number of subjects with constant esotropia for less than three months prior to enrollment was 41 (51%) for IET, 50 (53%) for ANAET, and 26 (45%) for APAET. Among subjects with IET, alignment was measured at baseline and throughout the study using PACT at near in 57 (70%) subjects and using a modified Krimsky at near in the 24 (30%) subjects in whom PACT testing could not be performed. Baseline characteristics appeared similar comparing subjects with IET who were measured using PACT and subjects with IET who were measured with the Krimsky method, except that subjects measured with the Krimsky method were younger (mean age 5.2 versus 6.3 months) and had esotropia for a shorter duration (2.5 versus 3.2 months). All subjects with ANAET and all subjects with APAET had alignment measured exclusively with PACT at near throughout the study (no Krimsky measurements). Additional baseline characteristics for the cohorts for each esotropia type are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics.

| IET

(N=81) |

ANAET

(N=94) |

APAET

(N=58) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Characteristic | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) |

| Female Gender | 40 (49) | 49 (52) | 26 (48) |

|

| |||

| White Race | 64 (79) | 77 (82) | 51 (88) |

|

| |||

| Age at Enrollment, in months | |||

| Mean (SD) | 6.0 (1.7) | 27.1 (12.0) | 30.1 (13.3) |

| Range | 2.4 to 9.5 | 8.4 to 58.8 | 9.6 to 58.3 |

| 2 to <3 months | 6 (7) | ---- | ---- |

| 3 to <6 months | 31 (38) | ---- | ---- |

| 6 to <9 months | 42 (52) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) |

| 9 to <12 months | 2 (2) | 5 (5) | 2 (3) |

| 12 to <24 months | ---- | 35 (37) | 21 (36) |

| 24 to <36 months | ---- | 31 (33) | 18 (31) |

| 36 to <48 months | ---- | 14 (15) | 9 (16) |

| 48 to <60 months | ---- | 7 (7) | 8 (14) |

|

| |||

| Duration of Constant Esotropia At Enrollment*, in months | |||

| Mean (SD) | 3.0 (1.5) | 3.1 (1.4) | 3.3 (1.4) |

| Range | 0.4 to 5.8 | 0.2 to 5.8 | 0.5 (5.9) |

| 0 to <1 month | 8 (10) | 4 (4) | 1 (2) |

| 1 to <2 months | 15 (19) | 17 (18) | 11 (19) |

| 2 to <3 month | 18 (22) | 29 (31) | 14 (24) |

| 3 to <4 month | 14 (17) | 17 (18) | 11 (19) |

| 4 to <5 month | 17 (21) | 14 (15) | 10 (17) |

| 5 to <6 month | 9 (11) | 13 (14) | 11 (19) |

|

| |||

| Angle of Deviation, in prism diopters | |||

| Mean | 34.5 (9.8) | 30.1 (8.8) | 28.4 (9.2) |

| Range | 20.0 to 50 | 16.0 to 50.0 | 16.0 to 50.0 |

| 15 to 30 PD | 35 (43) | 56 (60) | 45 (78) |

| 31 to 40 PD | 23 (28) | 29 (31) | 6 (10) |

| 41 to 50 PD | 23 (28) | 9 (10) | 7 (12) |

|

| |||

| Measurement Method | |||

| PACT at Near | 57 (70) | 94 (100) | 58 (100) |

| Krimsky at Near | 24 (30) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

|

| |||

| Esotropia Character | |||

| Constant | 73 (90) | 89 (95) | 56 (97) |

| Variable** | 8 (10) | 5 (5) | 2 (3) |

|

| |||

| Significant Refractive Error*** | 13 (16) | 41 (44) | 55 (95) |

|

| |||

| Spectacle Correction | 23 (28) | 51 (54) | 58 (100) |

|

| |||

| Amblyopia**** | 20 (25) | 37 (40) | 23 (40) |

|

| |||

| Method of Assessing For Amblyopia | |||

| Fixation preference | 76 (94) | 74 (80) | 39 (67) |

| Visual Acuity | 0 (0) | 13 (14) | 18 (31) |

| Unknown | 5 (6) | 6 (6) | 1 (2) |

|

| |||

| Inferior oblique overaction | 1 (1) | 14 (15) | 10 (17) |

|

| |||

| Superior oblique overaction | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

|

| |||

| Dissociated vertical deviation | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

|

| |||

| Nystagmus | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

|

| |||

| Vertical pattern present***** | 2 (2) | 10 (11) | 5 (9) |

IET = infantile esotropia, ANAET = acquired non-accommodative esotropia, ANAET = acquired partially-accommodative esotropia, PD = prism diopters, SD = standard deviation, PACT = Prism and Alternate Cover Test

Time with esotropia prior to 2 months of age did not count towards the calculation of duration.

Variable refers to a deviation that changed in magnitude during the examination but was not intermittent.

- Spherical equivalent in one or both eyes ≥ +3.00 D for IET or ≥ ±2.00 D for ANAET and ANAET

- Astigmatism in one or both eyes ≥ +3.50 D for IET or ≥ ±2.50 D for ANAET and APAET

- Anisometropia ≥ 2.00D in spherical equivalent

Presence of amblyopia was assessed by optotype visual acuity if possible, with amblyopia considered present if two lines or more difference existed in visual acuity between the eyes. For subjects in whom optotype testing was not possible, an assessment of fixation preference was made, with amblyopia considered present if the subject had a preferred eye and if the nonpreferred eye could not maintain fixation for ≥3 seconds or through a blink or through a smooth pursuit.

For IET, 2 subjects had a V pattern present; for ANAET, 8 subjects had a V pattern and 2 had an A pattern; for APAET, 5 subjects had a V pattern

Visit Completion

Of the 81 subjects with IET enrolled in the study, 62 (77%) subjects completed all three follow-up visits (6, 12, and 18 weeks), 8 (10%) completed two visits, 8 (10%) completed one visit, and 3 (4%) did not complete any follow-up visits. Of the 14 subjects with IET who did not complete the 18-week visit, 2 subjects ended follow up early to have surgery before 18 weeks, one of whom increased from 35 PD at baseline to 50 PD at the 12-week visit before surgery. Subjects who did not complete the study tended to have slightly larger baseline angles than subjects who completed the study (36 PD vs. 30 PD respectively), but were similar with regard to age and duration of esotropia.

Of the 94 subjects with ANAET enrolled in the study, 66 (70%) subjects completed all three follow-up visits (6, 12, and 18 weeks), 9 (10%) completed two visits, 10 (11%) completed one visit, and 9 (10%) did not complete any follow-up visits. Of the 19 subjects with ANAET who did not complete the 18-week visit, 2 subjects ended follow up early to have surgery before 18 weeks, neither of whom increased more than 10 PD from baseline before surgery. Subjects who did not complete the study were similar subjects to who completed the study with regard to age, baseline angle size, and duration of esotropia.

Of the 58 subjects with APAET enrolled in the study, 44 (76%) subjects completed all three follow-up visits (6, 12, and 18 weeks), 8 (14%) completed two visits, 5 (9%) completed one visit, and 1 (2%) did not complete any follow-up visits. Of the 11 APAET subjects who did not complete the 18-week visit, 1 subject whose angle had increased from 25 PD at baseline to 50 PD at the 12-week visit ended follow up early to have surgery before 18 weeks. Subjects who did not complete the study were similar subjects to who completed the study with regard to age, baseline angle size, and duration of esotropia.

Amblyopia Treatment Over 18 Weeks

Of subjects who completed at least one visit, the number who received amblyopia treatment with patching at any time during follow up, was 53 (68%) of 78 for IET, 59 (69%) of 85 for ANAET, and 38 (67%) of 57 for APAET. One (1%) subject with IET, one (1%) subject with ANAET, and one (2%) subject with APAET received treatment with atropine at some point during follow up and were excluded from all outcome analyses.

IET - Ocular Alignment Change Over 18 Weeks

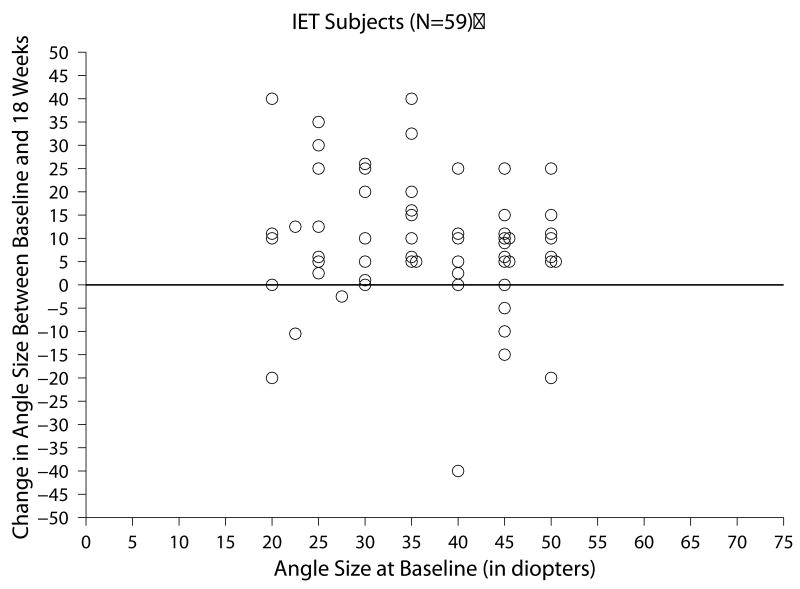

Of the 59 subjects with IET who completed all three follow-up visits within the time window for analysis, the change in ocular alignment measurements between baseline and the 18-week visit ranged from -40 to +40 PD (Figure 1a) and the mean absolute change between these two visits was 13.0 ±10.7 PD. At 18 weeks, subjects' angles were within ±9 PD for 22 (37%), had increased from baseline by 10 PD or more in 31 (53%), and had decreased by 10 or more PD in 6 (10%), (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Table 3. Angle Change Between Two Timepoints.

| Change Between Two Timepoints | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 to 6 Wks | 6 to 12 Wks | 12 to18 Wks | 0 to 18 Wks | |

| IET Subjects (N=59) | ||||

| Mean of absolute change (SD), in PD | 7.5 (7.5) | 8.4 (8.0) | 3.7 (5.9) | 13.0 (10.7) |

| Range of change, in PD* | - 40 to 25 | -25 to 30 | -20 to 30 | -40 to 40 |

| Amount of change, in PD, N (%)** | ||||

| Increased >=20 PD | 5 (8) | 5 (8) | 1 (2) | 13 (22) |

| Increased 15-<20 PD | 0 (0) | 6 (10) | 1 (2) | 4 (7) |

| Increased 10-<15 PD | 13 (22) | 10 (17) | 2 (3) | 14 (24) |

| Increased 5-<10 PD | 16 (27) | 11 (19) | 10 (17) | 13 (22) |

| Within ±<5 PD | 14 (24) | 17 (29) | 37 (63) | 8 (14) |

| Decreased 5-<10 PD | 8 (14) | 6 (10) | 4 (7) | 1 (2) |

| Decreased 10-<15 PD | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 2 (3) |

| Decreased 15-<20 PD | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 2 (3) | 1 (2) |

| Decreased >=20 PD | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | 1 (2) | 3 (5) |

|

| ||||

| ANAET Subjects (N=60) | ||||

| Mean of absolute change (SD), in PD | 5.9 (5.7) | 4.1 (4.9) | 3.8 (4.6) | 8.0 (7.9) |

| Range of change, in PD* | -25 to 20 | -12 to 25 | -16 to 17.5 | -25 to 50 |

| Amount of change, in PD, N (%)** | ||||

| Increased >=20 PD | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 3 (5) |

| Increased 15-<20 PD | 3 (5) | 3 (5) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) |

| Increased 10-<15 PD | 8 (13) | 1 (2) | 3 (5) | 16 (27) |

| Increased 5-<10 PD | 11 (18) | 9 (15) | 13 (22) | 11 (18) |

| Within +<5 PD | 25 (42) | 33 (55) | 33 (55) | 16 (27) |

| Decreased 5-<10 PD | 7 (12) | 11 (18) | 5 (8) | 7 (12) |

| Decreased 10-<15 PD | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | 3 (5) | 3 (5) |

| Decreased 15-<20 PD | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 2 (3) | 1 (2) |

| Decreased >=20 PD | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (3) |

|

| ||||

| APAET Subjects (N=41) | ||||

| Mean of absolute change (SD), in PD | 3.4 (3.4) | 4.2 (4.2) | 3.8 (3.5) | 6.1 (5.6) |

| Range of change, in PD* | -6.5 to 17 | -10 to 17.5 | -10 to 15 | -18.5 to 19.5 |

| Amount of change, in PD, N (%)** | ||||

| Increased >=20 PD | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Increased 15-<20 PD | 1 (2) | 2 (5) | 1 (2) | 4 (10) |

| Increased 10-<15 PD | 1 (2) | 2 (5) | 1 (2) | 7 (17) |

| Increased 5-<10 PD | 9 (22) | 7 (17) | 10 (24) | 6 (15) |

| Within +<5 PD | 23 (56) | 22 (54) | 21 (51) | 17 (41) |

| Decreased 5-<10 PD | 7 (17) | 7 (17) | 7 (17) | 4 (10) |

| Decreased 10-<15 PD | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 2 (5) |

| Decreased 15-<20 PD | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) |

| Decreased >=20 PD | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

IET = infantile esotropia, ANAET = acquired non-accommodative esotropia, ANAET = acquired partially-accommodative esotropia,

PD = prism diopters

Positive values reflect increasing in angle; negative values represent decrease in angle.

Ocular alignment was classified as stable (all four measurements within 5 PD of one another) in 20% (95% CI = 11 to 33%) of subjects with IET, as unstable (difference between at least two of the four measurements is 15 PD or more) in 46% (95% CI = 33 to 59%), and as uncertain in 34% (95% CI = 22 to 47%) (Table 4 available at http://aaojournal.org).

Table 4. Angle Stability Overall and According to Baseline Characteristics.

| Characteristic | N | Ocular Alignment Stability | Risk Ratios for Unstable Versus Stable (99% Confidence Interval)* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stable | Uncertain | Unstable | ||||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||

| SUBJECTS WITH IET (N=59) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Overall | 59 | 12 (20) | 20 (34) | 27 (46) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||

| Age at Baseline, in months | ||||||

| 0-<6 months | 32 | 3 (9) | 12 (38) | 17 (53) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 6-<12 months | 27 | 9 (33) | 8 (30) | 10 (37) | 0.62 (0.34 to 1.14) | 0.62 (0.34 to 1.14) |

| Per additional month of age | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.85 (.074 to 0.99) | 0.85 (.74 to 0.99) |

|

| ||||||

| Measurement Method | ||||||

| PACT at Near | 41 | 9 (22) | 17 (41) | 15 (37) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Krimsky At Near | 18 | 3 (17) | 3 (17) | 12 (67) | 1.28 (0.76 to 2.17) | 1.06 (0.63 to 1.77) |

|

| ||||||

| Esotropia at Baseline, in prism diopters | ||||||

| 20-30 PD | 22 | 4 (18) | 7 (32) | 11 (50) | 1.10 (0.64 to 1.90) | 1.23 (0.73 to 2.05) |

| 31-50 PD | 37 | 8 (22) | 13 (35) | 16 (43) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||

| Duration of Constant Esotropia at Baseline | ||||||

| 0-<3 month | 32 | 5 (16) | 8 (25) | 19 (59) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 4-<6 month | 27 | 7 (26) | 12 (44) | 8 (30) | 0.67 (0.34 to 1.33) | 1.00 (0.41 to 2.43) |

| Per additional month of age | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.83 (0.67 to 1.04) | 0.95 (0.67 to 1.35) |

|

| ||||||

| Spectacle Wear | ||||||

| Yes (initiated at enrollment) | 15 | 6 (40) | 4 (27) | 5 (33) | 0.58 (0.24 to 1.41) | 0.66 (0.30 to 1.44) |

| No | 44 | 6 (14) | 16 (36) | 22 (50) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||

| Amblyopia at Baseline | ||||||

| Yes | 15 | 3 (20) | 7 (47) | 5 (33) | 0.88 (0.41 to 1.89) | 0.87 (0.48 to 1.58) |

| No | 44 | 9 (20) | 13 (30) | 22 (50) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||

| Amblyopia Anytime During 18 Weeks | ||||||

| Yes | 28 | 6 (21) | 11 (39) | 11 (39) | 0.89 (0.50 to 1.57) | 0.84 (0.50 to 1.41) |

| No | 31 | 6 (19) | 9 (29) | 16 (52) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Patching Anytime During 18 Weeks | ||||||

| Yes | 36 | 7 (19) | 11 (31) | 18 (50) | 1.12 (0.61 to 2.05) | 1.12 (0.64 to 1.95) |

| No | 23 | 5 (22) | 9 (39) | 9 (39) | ----- | ----- |

|

| ||||||

| SUBJECTS WITH ANAET (N=60) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Overall | 60 | 22 (37) | 25 (42) | 13 (22) | ----- | |

|

| ||||||

| Age at Baseline, in months | ||||||

| 6 to <24 months | 27 | 11 (41) | 9 (33) | 7 (26) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 24 to <60 months | 33 | 11 (33) | 16 (48) | 6 (18) | 0.91 (0.29 to 2.83) | 1.10 (0.38 to 3.19) |

| Per additional month of age | --- | --- | --- | --- | 1.01 (0.96 to 1.05) | 1.01 (0.97 to 1.05) |

|

| ||||||

| Esotropia at Baseline, in prism diopters | ||||||

| 15 to 30 PD | 38 | 13 (34) | 15 (39) | 10 (26) | 1.74 (0.42 to 7.24) | 1.51 (0.36 to 6.29) |

| 31 to 50 PD | 22 | 9 (41) | 10 (45) | 3 (14) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||

| Duration of Constant Esotropia at Baseline | ||||||

| 0-<3 months | 31 | 11 (35) | 10 (32) | 10 (32) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 4-<6 months | 29 | 11 (38) | 15 (52) | 3 (10) | 0.45 (0.11 to 1.91) | 0.45 (0.11 to 1.91) |

| Per additional month of duration | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.64 (0.46 to 0.89) | 0.64 (0.46 to 0.89) |

|

| ||||||

| Spectacle Wear | ||||||

| Yes | 36 | 13 (36) | 16 (44) | 7 (19) | 1.14 (0.37 to 3.54) | 0.72 (0.23 to 2.24) |

| No | 24 | 9 (38) | 9 (38) | 6 (25) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||

| Amblyopia at Baseline | ||||||

| Yes | 21 | 7 (33) | 9 (43) | 5 (24) | 1.20 (0.38 to 3.77) | 1.39 (0.44 to 4.45) |

| No | 39 | 15 (38) | 16 (41) | 8 (21) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||

| Amblyopia Anytime During 18 Weeks | ||||||

| Yes | 35 | 14 (40) | 13 (37) | 8 (23) | 0.95 (0.30 to 3.01) | 1.06 (0.36 to 3.11) |

| No | 25 | 8 (32) | 12 (48) | 5 (20) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||

| Patching Anytime During 18 Weeks** | ||||||

| Yes | 39 | 16 (41) | 15 (38) | 8 (21) | 0.73 (0.24 to 2.27) | 0.86 (0.30 to 2.49) |

| No | 21 | 6 (29) | 10 (48) | 5 (24) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||

| SUBJECTS WITH APAET (N=41) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Overall | 41 | 16 (39) | 19 (46) | 6 (15) | 1.00 | ----- |

|

| ||||||

| Age at Baseline, in months | ||||||

| 6 to <24 months | 15 | 3 (20) | 9 (60) | 3 (20) | 1.00 | ----- |

| 24 to <60 months | 26 | 13 (50) | 10 (38) | 3 (12) | 0.38 (0.07 to 2.06) | ----- |

| Per additional month of age | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.99 (0.91 to 1.08) | ----- |

|

| ||||||

| Esotropia at Baseline, in prism diopters | ||||||

| 15 to 30 PD | 33 | 11 (33) | 16 (48) | 6 (18) | not estimable | ----- |

| 31 to 50 PD | 8 | 5 (63) | 3 (38) | 0 (0) | 1.00 | ----- |

|

| ||||||

| Duration of Constant Esotropia at Baseline | ||||||

| 0 to <3 months | 17 | 6 (35) | 8 (47) | 3 (18) | 1.00 | ----- |

| 4 to <6 months | 24 | 10 (42) | 11 (46) | 3 (13) | 0.69 (0.12 to 4.11) | ----- |

| Per additional month of duration | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.77 (0.41 to 1.43) | ----- |

|

| ||||||

| Amblyopia at Baseline | ||||||

| Yes | 14 | 5 (36) | 5 (36) | 4 (29) | 2.89 (0.42 to 19.92) | ----- |

| No | 27 | 11 (41) | 15 (52) | 2 (7) | 1.00 | ----- |

|

| ||||||

| Amblyopia Anytime During 18 Weeks | ||||||

| Yes | 19 | 6 (32) | 8 (42) | 5 (26) | 5.00 (0.37 to 67.26) | ----- |

| No | 22 | 10 (45) | 11 (50) | 1 (5) | 1.00 | ----- |

|

| ||||||

| Patching Anytime During 18 Weeks | ||||||

| Yes | 28 | 10 (36) | 13 (46) | 5 (18) | 2.33 (0.18 to 30.29) | ----- |

| No | 13 | 6 (46) | 6 (46) | 1 (8) | 1.00 | ----- |

IET = infantile esotropia, ANAET = acquired non-accommodative esotropia, ANAET = acquired partially-accommodative esotropia,

Risk ratios and 99% confidence intervals are from Poisson regression models using a dichotomous variable unstable versus stable as the dependent variable. Subjects whose ocular alignment stability was classified as uncertain are not included in these analyses. The reference level of the given factor is indicated by 1.00. Unadjusted models contain the factor of interest as the only covariate. For subjects with IET, adjusted models include continuous age and the factor of interest as covariates. For subjects with ANAET, adjusted models include continuous duration of esotropia at baseline and the factor of interest as covariates. There are no adjusted models for subjects with APAET because no factor was found to be related to instability vs. stability in unadjusted models.

Among subjects with IET, 53% of subjects <6 months of age at baseline had unstable angles and 37% of subjects 6 to <12 months of age had unstable angles (risk ratio for instability = 0.85 per additional month of age, 99% CI = 0.74 to 0.99) (Table 4 available at http://aaojournal.org). We found no evidence that any of the other factors assessed in subjects with IET (measurement method [PACT versus Krimsky], angle size, duration of esotropia, spectacle wear, amblyopia, and patching treatment) were associated with instability vs. stability (Table 4 available at http://aaojournal.org).

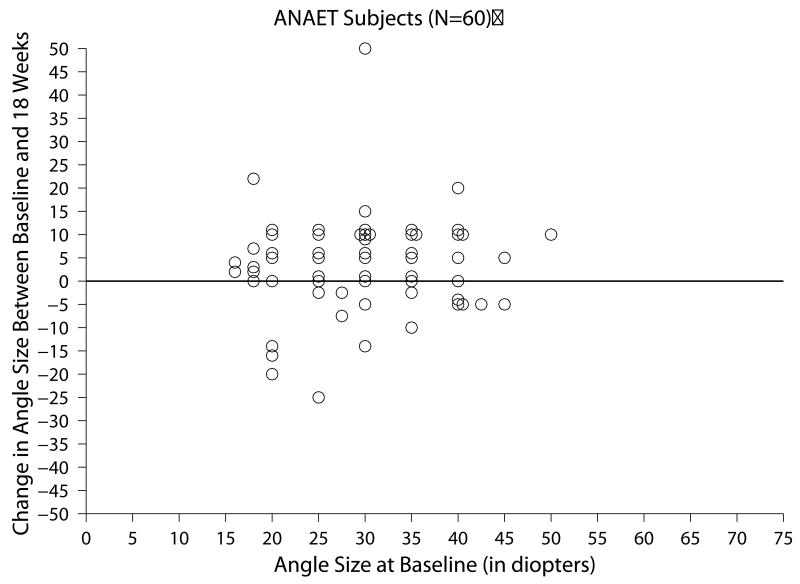

ANAET - Ocular Alignment Change Over 18 Weeks

Of the 60 subjects with ANAET who completed all three follow-up visits within the time window for analysis, the change in ocular alignment measurements between baseline and the 18-week visit ranged from -25 to +50 PD (Figure 1b) and the mean absolute change between these two visits was 8.0 ±7.9 PD. At 18 weeks, subjects' angles were within ±9 PD in 34 (57%), had increased 10 PD or more PD in 20 (33%), and had decreased 10 PD or more in 6 (10%) (Table 3).

Ocular alignment was classified as stable (all four measurements within 5 PD of one another) in 37% of subjects with ANAET (95% CI = 24 to 50%), as unstable (at least two of the four measurements differ by 15 PD or more) in 22% (95% CI = 12 to 34%), and uncertain (neither stable nor unstable) in 42% (95% CI = 29 to 55%) (Table 4 available at http://aaojournal.org).

Among subjects with ANAET, 32% of those who had esotropia for less than three months at baseline had unstable angles and 10% of those who had esotropia for between 4 to <6 months at baseline had unstable angles (risk ratio for instability = 0.64 per additional month of duration, 99% CI = 0.46 to 0.89) (Table 4 available at http://aaojournal.org). We found no evidence that age, angle size, spectacle wear, presence of amblyopia, or patching treatment were associated with instability vs. stability, in subjects with ANAET (Table 4 available at http://aaojournal.org).

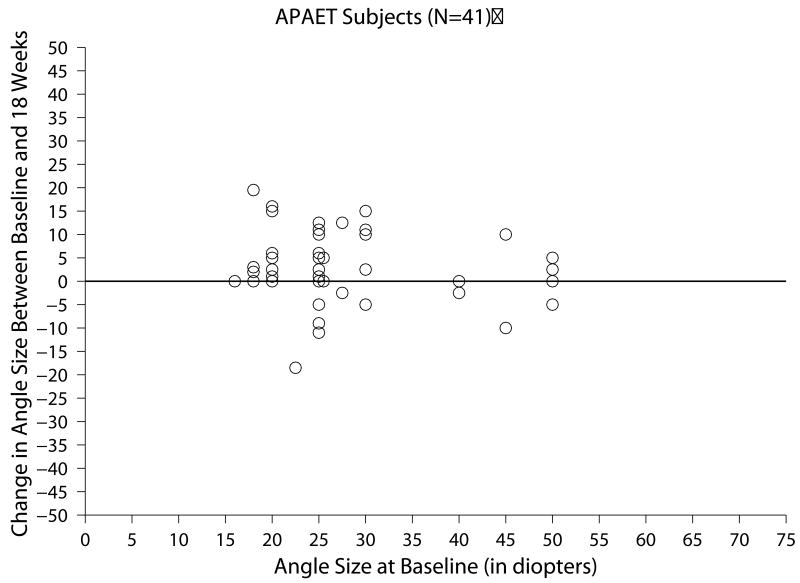

Ocular Alignment Change Over 18 Weeks in APAET Subjects

Of the 41 subjects with APAET who completed all three follow-up visits within the time window for analysis, the change in ocular alignment measurements between baseline and the 18-week visit ranged from -18.5 to 19.5 PD (Figure 1c) and the mean absolute change between these two visits was 6.1 ±5.6 PD. At 18 weeks, subjects' angles were within ±9 PD in 27 (66%), had increased 10 PD or more in 11 (27%), and had decreased 10PD or more in 3 (7%) (Table 3).

The proportion of subjects with APAET who were classified as stable was 39% (95% CI = 24 to 56%), as unstable was 15% (95% CI = 6 to 29%), and as uncertain was 46% (95% CI = 31 to 63%) (Table 4 available at http://aaojournal.org).

Among subjects with APAET, we could not calculate a risk ratio for instability for angle size as none of the patients with larger angles were classified as unstable. We did not find evidence that either age, duration of esotropia, presence of amblyopia, or patching treatment were associated with instability vs. stability (Table 4 available at http://aaojournal.org).

Discussion

In this prospective study of children with esotropia, we found that instability of ocular alignment is common, especially in the youngest children with IET. Using a conservative criterion for instability of ≥15 PD difference between any two measurements over four visits in an 18-week observation period, 46% of children with IET were classified as having unstable alignment. An additional 34% of children with IET were classified as having “uncertain” stability. Angle instability was present in 22% of children with ANAET and 15% of children with APAET, with an additional 42% and 46%, respectively, being classified as uncertain.

To compare our results to previous reports of angle instability, we found 53% of our subjects with IET had an increase in angle of esotropia of 10 PD or more, whereas 10% had a decrease of 10 PD or more. By comparison, in a retrospective study, Ing reported that 61% of subjects with IET had an increase of 10 PD or more between the initial visit (mean age 6.0 months) and the visit immediately prior to surgery (mean age 8.9 months).11 In contrast, the PEDIG group reported that for slightly younger infants (mean age = 14 weeks) with onset of constant esotropia prior to 20 weeks of age, the angle increased by 10 PD or more in 27% and decreased by 10 PD or more in 24% at the outcome visit at 28-32 weeks of age.9 In a prospective study of 187 infants 8 to 36 weeks of age at their initial visit, Birch et al reported that the angle of esotropia increased 10 PD or more in 33% of infants and decreased by 10 PD or more in 11%.12 For a subgroup of 127 patients who had three examinations, the angle increased between the second and third examinations in 31% and decreased in 7%.12 Direct comparison among these studies is difficult because observation periods differed, the subjects were different ages, and some studies were prospective while others were retrospective, but there appears to be consensus that angle instability in IET is common.

There are few data with which to compare our estimates of angle instability in acquired esotropia. For children with ANAET, Kitzmann et al.13 reported that 33% increased by 10 PD or more over a 3 month period, which is similar to our finding of 33% increasing by 10 PD or more. We found that 27% of patients were within ±4 PD over the 18-week observation period, compared with 33% changing within -5 PD to +4 PD in the study of Kitzmann et al.13 Kitzmann's study13 was based on a retrospective review of case records in a single institution whereas our study involved prospective data collection across multiple sites. We are not aware of previous studies of angle instability in APAET with which to compare our results. We were somewhat surprised by the high frequency of angle instability and uncertainty regarding angle stability, in children with esotropia.

While the impact of preoperative alignment instability on postoperative motor or sensory outcomes is not clear,12 the high frequency of instability and uncertain stability raises an important clinical question about the timing of surgery for each of the three types of esotropia. Should surgery be performed immediately to minimize the duration of esotropia, because shorter duration of misalignment has been associated with better sensory and motor outcomes?2-8 Or should surgery for esotropia be delayed until stability is achieved and an accurate surgical dosage could be determined? One might speculate that performing surgery in the face of a changing misalignment might reduce the chance of an optimum motor and sensory result. This argument might provide a rationale for waiting for a stable angle before performing surgery. Nevertheless, it is not known whether the angle of misalignment would continue to change after surgery in the same way that it might have with further follow up before surgery. The issue of optimal timing of surgery would best be addressed in randomized clinical trials for each type of esotropia, randomizing children to immediate surgery for the angle at presentation versus delayed surgery after stability of angle had been confirmed.

In the present study, the mean duration of misalignment for each of the three types of esotropia at presentation was approximately three months. The relatively brief duration of esotropia at presentation in these cohorts suggests that it is feasible to recruit children with esotropia early in the course of their disease into a future randomized clinical trial. In such a trial, a short duration of esotropia prior to enrollment would be essential to ensure that the two randomized groups were sufficiently different in terms of total duration of misalignment once the delayed-surgery cohort reached stability. In addition, the fact that the majority of children with all three types of esotropia had a deviation that was either unstable or of uncertain stability indicates that there is a need to evaluate the optimal timing of surgery.

Of the baseline factors we analyzed in infantile esotropia, only age at baseline was associated with instability versus stability, with younger children having a higher frequency of instability. This association has also been reported in other studies of children with ANAET.13 It is possible that poorer attention or poorer control of accommodative convergence in younger children might be responsible for the association of younger age with instability, but it is difficult to quantitatively assess these factors. Prior to the study, we might have expected the Krimsky method of measurement to be associated with greater measured angle instability than the PACT method, because we found greater test-retest variability with that method (PEDIG, unpublished data). Nevertheless, we found no association of instability with the Krimsky method.

We found little evidence of association of baseline factors with instability versus stability in either type of acquired esotropia, although an association of shorter duration of esotropia with alignment instability was found among children with ANAET, similar to a finding reported by Kitzmann.13 Our failure to detect other associations of baseline factors with instability versus stability may have been due to a relatively small sample sizes.

The presence of amblyopia at the baseline examination was not associated with greater angle instability in any of the three types of esotropia. Therefore, data for children with amblyopia were combined with data from children without amblyopia for the primary analysis. A weakness of this study is that amblyopia was diagnosed based on fixation preference (always in IET and often in AET) and was defined as the inability to hold fixation with the non-preferred eye for ≥3 seconds or through a blink or through a smooth pursuit. The nearly exclusive use of fixation preference to determine amblyopia may have resulted in substantial misclassification due to poor sensitivity and specificity of the test 14 (Cotter SA, et al. IOVS 2007;48:ARVO E-Abstract 2380) of amblyopia in our study.

There are other potential weaknesses of our study. Investigators did not enroll consecutive subjects but only those they felt comfortable following for 18 weeks prior to surgery and whose parents agreed to an extended observation period. This may have resulted in a selection bias towards subjects whose angle of esotropia seemed variable at the initial visit or who had amblyopia and would need patching treatment prior to surgery. Nevertheless, because we only had a small percentage of subjects classified as having “variable” angles at the enrollment exam (10% for IET, 5% for ANAET and 3% for APAET), we believe that such subjects are not overrepresented in our cohort. An additional weakness of the study design is that investigators may not have been completely masked to their previous measurements. Although investigators were instructed to measure alignment before consulting the subject's chart, it is impossible to completely mask an investigator to the subject's previous measures. If such a bias were present, it would increase the frequency of similar alignment measurements, making it unlikely that we overestimated instability in the present study.

Applying our definitions of unstable, uncertain, and stable alignments directly to clinical practice, and applying them to a future clinical trial, is problematic. We used longitudinal data from four visits across an 18-week period to classify stability or instability, whereas in clinical practice and in a clinical trial, classification of an individual child would need to be based on the current visit in light of the preceding visits. In order to define angle instability or stability in clinical practice and for future clinical trials, a new set of rules needs to be developed, incorporating data from successive measurement, rather than using a fixed duration of follow up. Further modeling is needed to define such rules for categorizing angle stability or instability in an ongoing fashion.

In conclusion, angle instability is common in IET, ANAET and APAET. In IET, angle instability appears particularly common in infants younger than 6 months of age. The effect of unstable alignment on the timing of surgery and on motor or sensory outcomes following surgery is worthy of further study. In each of these types of esotropia, randomized controlled trials are needed to compare outcomes following immediate surgery versus waiting for alignment stability.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services (EY011751).

Writing Committee

Lead authors: Stephen P. Christiansen, M.D; Danielle L. Chandler, MSPH; Jonathan M. Holmes BM, BCh. Additional writing committee members (alphabetical): Robert W. Arnold MD; Eileen Birch, PhD; Linda R. Dagi, MD; Darren L. Hoover, M.D.; Deborah L. Klimek, MD; B. Michele Melia, ScM; Evelyn Paysse, MD; Michael X. Repka, MD; Donny W. Suh, MD; Benjamin H. Ticho, MD; David K. Wallace, MD; Richard Grey Weaver, Jr., MD.

The Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group

Clinical Sites that Participated in this Protocol:

Sites are listed in order by number of subjects enrolled into the study. Personnel are listed as (I) for Investigator

Anchorage, AK - Ophthalmic Associates (61)

Robert W. Arnold (I)

Erie, PA - Pediatric Ophthalmology of Erie (26)

Nicholas A. Sala (I)

Cranberry TWP, PA - Everett and Hurite Ophthalmic Association (23)

Darren L. Hoover (I)

Nashville, TN - Vanderbilt Eye Center * (19)

Sean Donahue (I); David G. Morrison (I)

Lancaster, PA - Family Eye Group (16)

David I. Silbert (I); Eric L. Singman (I)

West Des Moines, IA - Wolfe Clinic (14)

Donny W. Suh (I)

Chicago Ridge, IL - The Eye Specialists Center, L.L.C. (13)

Benjamin H. Ticho (I); Alexander J. Khammar (I)

Minneapolis, MN - University of Minnesota* (13)

C. Gail Summers (I); Erick D. Bothun (I); Stephen P. Christiansen (I)

Dallas, TX - Pediatric Ophthalmology, P.A. (10)

David R. Stager, Sr. (I)

Rockville, MD - Stephen R. Glaser, M.D., P.C. (9)

Stephen R. Glaser (I)

South Charleston, WV - Children's Eye Care & Adult Strabismus Sugery (9)

Deborah L. Klimek (I)

Durham, NC - Duke University Eye Center (8)

Laura B. Enyedi (I); Sharon F. Freedman (I); David K. Wallace (I); Terri L. Young (I)

Houston, TX - Texas Children's Hospital (7)

Evelyn A. Paysse (I); David K. Coats (I); Kimberly G. Yen (I); Jane Covington Edmond (I); Paul G. Steinkuller (I)

Sharon, MA - Daniel M. Laby, M.D. (6)

Daniel M. Laby (I)

Winston-Salem, NC - Wake Forest University (6)

Richard Grey Weaver, Jr. (I)

Durham, NC - North Carolina Eye Ear & Throat (5)

Joan Therese Roberts (I)

Portland, OR - Casey Eye Institute* (5)

David T. Wheeler (I); Daniel J. Karr (I); Ann U. Stout (I)

Saint Paul, MN - Associated Eye Care (5)

Susan Schloff (I)

Wilmette, IL - Pediatric Eye Associates (5)

Deborah R. Fishman (I)

Albuquerque, NM - Children's Eye Center of New Mexico (4)

Todd A. Goldblum (I)

Boston, MA - Department of Ophthalmology, Children's Hospital Boston (4)

Linda R. Dagi (I)

Baltimore, MD - Wilmer Institute* (3)

Michael X. Repka (I)

Milford, CT - Eye Physicians & Surgeons, PC (3)

Darron A. Bacal (I)

Rochester, MN - Mayo Clinic* (3)

Jonathan M. Holmes (I); Brian G. Mohney (I)

St. Louis, MO - Cardinal Glennon Children's Hospital (3)

Oscar A. Cruz (I); Bradley V. Davitt (I)

Boise, ID - Katherine Ann Lee, M.D., PA. (2)

Katherine A. Lee (I)

Grand Rapids, MI - Pediatric Ophthalmology, P.C. (2)

Patrick J. Droste (I); Robert J. Peters (I)

Indianapolis, IN - Indiana University Medical Center (2)

Daniel E. Neely (I)

Pinehurst, NC - Family Eye Care of the Carolinas (2)

Michael John Bartiss (I)

Atlanta, GA - The Emory Eye Center (1)

Scott R. Lambert (I)

Brighton, MI - University of Michigan (1)

Erika M. Levin (I)

Indianapolis, IN - Midwest Eye Institute (1)

Derek T. Sprunger (I); Gavin J. Roberts (I)

Sacramento, CA - University of California, Davis Dept. of Ophthalmology (1)

Mary O'Hara (I)

Springfield, MO - St. John's Clinic - Eye Specialists (1)

Scott Atkinson (I)

Waterbury, CT - Eye Care Group, PC (1)

Andrew J. Levada (I)

Footnotes

No conflicting relationships exist for any author

Center received support utilized for this project from an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness Inc., New York, New York.

This article contains online-only material. The following should appear online-only: Table 4.

References

- 1.Greenberg AE, Mohney BG, Diehl NN, Burke JP. Incidence and types of childhood esotropia: a population-based study. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:170–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.05.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ing MR. Early surgical alignment for congenital esotropia. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1981;79:625–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ing MR. Outcome study of surgical alignment before six months of age for congenital esotropia. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:2041–5. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(95)30756-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright KW, Edelman PM, McVey JH, et al. High-grade stereo acuity after early surgery for congenital esotropia. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994;112:913–9. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1994.01090190061022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birch EE, Stager DR, Everett ME. Random dot stereoacuity following surgical correction of infantile esotropia. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1995;32:231–5. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19950701-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Birch E, Stager D, Wright K, Beck R. The natural history of infantile esotropia during the first six months of life. J AAPOS. 1998;2:325–9. doi: 10.1016/s1091-8531(98)90026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birch EE, Stager DR., Sr Long-term motor and sensory outcomes after early surgery for infantile esotropia. J AAPOS. 2006;10:409–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Birch EE, Fawcett S, Stager DR. Why does early surgical alignment improve stereoacuity outcomes in infantile esotropia? J AAPOS. 2000;4:10–4. doi: 10.1016/s1091-8531(00)90005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. Spontaneous resolution of early-onset esotropia: experience of the Congenital Esotropia Observational Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;133:109–18. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(01)01316-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zou G. A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;59:702–6. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ing MR. Progressive increase in the angle of deviation in congenital esotropia. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1994;XCII:117–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Birch EE, Felius J, Stager S DR, et al. Pre-Operative Stability of infantile esotropia and post-operative outcome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;138:1003–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.07.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kitzmann AS, Mohney BG, Diehl NN. Progressive increase in the angle of deviation in acquired nonaccommodative esotropia of childhood. J AAPOS. 2003;7:349–53. doi: 10.1016/s1091-8531(03)00216-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sener EC, Mocan MC, Gedik S, et al. The reliability of grading the fixation preference test for the assessment of interocular visual acuity differences in patients with strabismus. J AAPOS. 2002;6:191–4. doi: 10.1067/mpa.2002.122364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.