Abstract

In order to overcome some of the limitations of an implantable coil, including its invasive nature and limited spatial coverage, a three element phased array coil is described for high resolution magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of rat spinal cord. This coil allows imaging both thoracic and cervical segments of rat spinal cord. In the current design, coupling between the nearest neighbors was minimized by overlapping the coil elements. A simple capacitive network was used for decoupling the next neighbor elements. The dimensions of individual coils in the array were determined based on the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) measurements performed on a phantom with three different surface coils. SNR measurements on a phantom demonstrated higher SNR of the phased array coil relative to two different volume coils. In-vivo images acquired on rat spinal cord with our coil demonstrated excellent gray and white matter contrast. To evaluate the performance of the phased array coil under parallel imaging, g-factor maps were obtained for two different acceleration factors of 2 and 3. These simulations indicate that parallel imaging with acceleration factor of 2 would be possible without significant image reconstruction related noise amplifications.

Keywords: MRI, spinal cord, phased array coil, parallel imaging, capacitive decoupling, g-factor

Introduction

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with its excellent soft tissue contrast is the radiologic modality of choice for non-invasively following pathological changes in experimental spinal cord injury (SCI) and other spinal cord pathologies. Rats are commonly used in experimental spinal cord injuries. Due to the small size of rat spinal cord, high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) is needed to achieve sufficient image resolution. In order to overcome the SNR problems, implanted coils are often used (1-3). While implanted coils provide high SNR, they have several limitations. Coil implantation is an invasive procedure. Also, the resonance frequency of an implanted coil can drift with time, and it is almost impossible to reverse this frequency drift. This results in loss of SNR over time. In experimental SCI, the spinal cord is generally injured at the thoracic level. Because of the spatial and temporal progression of the secondary injury, it is important to image regions at and away from the site of injury, including the cervical region. Cervical spinal cord section is located relatively deep from the surface and the surgical procedure involved in implanting a coil in this region could damage important surrounding structures. Thus, there is a critical need for developing external coils for imaging both thoracic and cervical spinal cord with high SNR. Single element external surface coils have recently been reported to non-invasively acquire diffusion tensor maps from rodent spinal cord (4,5). However, these coils provide limited SNR and spatial coverage both along the length and depth of the spinal cord.

In contrast to a single surface coil, phased array coils offer extended coverage and high SNR (6,7). In addition, phased array coils offer parallel imaging capabilities (8-12). Parallel imaging techniques at high field have several advantages(13-15). They can reduce the scan times, blurring, geometric distortions, radio frequency related heating, and acoustic noise at the expense of some SNR loss.

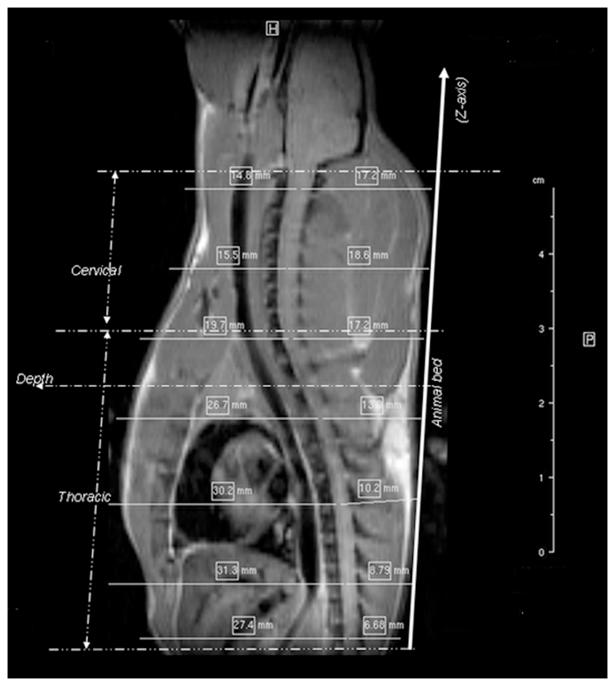

Several phased array coils for imaging rodents at high fields have been described in the literature. These include a four channel coil for imaging cat spine at 4.7T (16), a four channel array coil for mouse brain imaging at 14.1T (17), a four channel coil for imaging scirius-griseus at 14.1T (18), and a four channel coil for mouse imaging at 7T (19). However, their performance in imaging rat spinal cord was not addressed. A four channel array coil was developed for imaging rat spinal cord at 7T and its SNR performance was compared with implantable coils (20). These comparisons were made at the T10 thoracic segment, which is about 7-9 mm deep from the surface (Fig. 1). The performance of this coil was not addressed in imaging the deeper regions of the spinal cord. As can be seen from Fig. 1, different segments of the spinal cord are located at different depths. Thoracic segments are about 7-17 mm deep and cervical segments are about 17-20 mm deep. The variable depths of different segments of the spinal cord from the surface pose technical challenges in determining the appropriate dimensions of the elements in the array for imaging both thoracic and cervical regions of the spinal cord.

Figure 1.

Sagittal MRI of an adult male Sprague-Dawley rat demonstrating the distances of various segments of the spinal cord from the surface.

Several challenges have to be overcome in designing phased array coils. Minimizing coupling between different coil elements is perhaps technically most challenging. The coupling between neighboring coils is most commonly minimized by overlapping the elements of the coil (6,7). To minimize coupling between the next neighboring elements, matching networks have been developed and applied (6,7,16,21). These matching networks require low impedance preamplifiers to minimize currents in the coil loops. Some of the difficulties with such an approach include obtaining low impedance preamplifiers at high fields as well as tuning and matching the coils for different loading conditions. Four element phased array coils were developed at high fields with capacitive decoupling networks that do not require low impedance preamplifiers (17,18). In this study we focused on a three element phased array coil since the decoupling between the next neighbors can be achieved with a simple capacitive decoupling network and need neither low impedance preamplifiers nor complicated capacitive decoupling networks. This makes the design simple and easy to reproduce. At the same time, by judiciously choosing the dimensions of the individual elements, a three element array coil can provide sufficient SNR for imaging both thoracic and cervical segments of the spinal cord in rats.

Theory

The physical layout of the coil designed in the current study is shown in Fig. 2(a). When coupling between the neighboring elements in the array is minimized by overlapping, the equivalent circuit model of the next neighboring coils is shown in Fig. 2(b).

Figure 2.

Three element phased array coil and circuit model for the next neighbors. The phased array coil is shown in (a) and the circuit model of the next neighbor coil loops in (b). V1 and V3 are the induced voltages; I1 and I3 are the currents in the loops; R1 and R3 are the loaded resistances; L1 and L3 are the self inductances; M13 is the mutual inductance between the next neighbors; Cbreq1 and Cbreq3 are the breaking capacitors; C1 and C2 are the capacitors in the decoupling network. The circuit model of a single coil is shown in (c) and a detailed description of different components is provided in Table 1.

Applying mesh analysis to the circuit in Fig. 2(b), the mesh equations can be written as,

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

where, V1 and V3 are the induced voltages and I1 and I3 are the currents in the loops as shown in Fig 2(b). To achieve decoupling between the next neighboring coils, coupling voltage terms, in Eq. (1) and in Eq. (2), have to be minimized. Equation (3) can be rewritten as,

| (4) |

Substituting Eq. (4) in Eqs. (1) and. (2) yields,

| (5) |

| (6) |

Finally, the coupling terms in Eqs. (5) and (6) are minimized when,

| (7) |

| (8) |

where, .

Methods

All MR studies were performed on a Bruker 70/30 USR scanner (Bruker Biospec, Karlsruhe, Germany) with BGA-20/BS-30 gradient/shim system. The phased array coil was used in the receive-only mode and a 154 mm diameter volume coil (linear birdcage resonator, provided by the MR scanner manufacturer) was used for transmitting the RF power. To simulate the loading properties of the rat, a 45 mm diameter plastic bottle ( 8 cm long) filled with phosphate buffered saline solution (pH of 7.4) was used.

Male Sprague-Dawley rats, weighing between 300 and 350 g, were used for acquiring invivo images. The animals were placed in the supine position for stable breathing.

A RARE sequence with the following parameters was used to acquire all images in this study: TR/TE = 1835.9/23.8 ms, ETL = 4, NEX = 8, slice thickness = 1 mm, in plane resolution = 0.17 mm × 0.17 mm and total imaging time = 15 m 21s. Sum-of-squares (SOS) technique was used to reconstruct composite images from the individual coil images. When SNR comparisons were made between different single element receive coils , the SNR of the coil at a particular depth was calculated as the signal at the given depth divided by the standard deviation within a circular ROI in the background. The SNR of the array was determined by measuring the SNR in each magnitude image of the array and then taking the square root of the sum-of-squares of the individual SNRs (16).

Single coil geometry selection

In designing the array coil, the selection of the geometry of the single coil plays a critical role in the final SNR. Varying depths of different segments of the spinal cord from the coil pose technical difficulties in selecting the optimal geometry. In the current studies, three different saddle shaped coils were prepared on a flexible planar surface with the following dimensions: 1) 10 mm × 50 mm; 2) 15 mm × 50 mm; and 3) 20 mm × 50 mm; where 50 mm was the length of the coil along the z-axis (along the length of the spinal cord). This 50 mm length covers the spinal cord segments of interest. The coils were wrapped around an acrylic tube (of dimensions 57 mm OD × 51 mm ID) that fits the rat body in the supine position. Phantom images were acquired with these coils and the SNR of these coils was quantified at different depths (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Depth vs. SNR profiles of three different coils 10 mm × 50 mm, 15 mm × 50 mm and 20 mm × 50 mm. 100 % SNR corresponds to SNR from 10 mm × 50 mm coil at the surface of the phantom. Depth 0 mm corresponds to the surface of the phantom which is separated from the coil by the tube thickness of 3.5 mm.

Based on the results shown in Fig. 3, 15 mm × 50 mm and 20 mm × 50 mm coils provide higher SNR than the 10 mm × 50 mm coil in the thoracic and cervical regions (depths range between 7-20 mm). Though 15 mm × 50 mm and 20 mm × 50 mm coils were observed to have similar SNR in these regions, the 20 mm × 50 mm coil geometry was chosen in the current design for its increased lateral coverage.

Array design

In the current design, wrap-around phased array geometric configuration was chosen over a linear array (along z-axis) configuration for two reasons 1) high SNR from the deeper regions of the spinal cord and 2) parallel imaging capabilities for acquiring axial images.

Each coil in the array had 20 mm × 50 mm dimensions on a planar surface. The coils were milled on a flexible PCB (R/flex 1000, copper weight – 2 oz./ft.2; Rogers Corp, Chandler, AZ) with an LPKF ProtoMat®-M60 milling machine (LPKF Laser & Electronics, Wilsonville, OR). With the coils wrapped around a 57 mm OD × 51 mm ID acrylic tube, their measured selfinductance was 89 nH and the loaded resistance was 4.9 Ω. These measurements were based on the S21 measurements (made with HP 4396B network analyzer) between two well decoupled pick up coils that were placed on top of the phantom.

The adjacent elements in the array were arranged with an overlap of 2.75 mm to minimize the coupling between the neighbors. The decoupling between next neighbors was minimized by a simple capacitive decoupling network shown in Fig. 2(b). The capacitor C1 (12 pF) in Fig. 2(b) was a fixed capacitor and capacitor C2 (1-5 pF) was a variable capacitor. The capacitorC2 was varied until coupling between the next neighboring coils was minimized. No S11 peak splitting was observed on the network analyzer when a proper value for C2 was realized.

The circuit model of a single coil with matching and tuning networks is shown in Fig. 2(c). The description of different components and their values are summarized in Table.1. Each element in the array was decoupled from the volume coil both actively and passively. The passive decoupling was achieved by connecting a pair of crossed diodes in parallel to one of the breaking capacitors (Fig. 2(c)). The active coupling was achieved by applying 4.6V during transmit and -32.5V during receive to a PIN diode. These voltages were derived from the scanner’s decoupling unit. To reduce the shield currents on the coaxial cable, a bridge balun (22) was designed that satisfied the following Eq. (9-10). The values for the balun inductor Lb and capacitor Cb can be found in Table. 1.

| (9) |

| (10) |

Table 1.

Description of different components in Fig. 2(c) and their values

| Component | Value | Description | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coil-1 | Coil-2 | Coil-3 | ||

| L | 89.5 nH | 89.5 nH | 89.5 nH | Self-inductance of the coil |

| Rc | 4.9 Ω | 4.9 Ω | 4.9 Ω | Loaded resistance of the coil |

| Cbr1 | 12 pF | 12 pF | 12 pF | Breaking capacitor to which a crossed diode was connected for passive decoupling from the volume coil. |

| Cbr2 | 10 pF | 8 pF | 10 pF | Equivalent capacitance of the remaining three breaking capacitors on the coil |

| Cd | 16-52 pF | None | 16-52 pF | Additional capacitance added from the decoupling network |

| Ct | 5-10 pF | 5-10 pF | 5-10 pF | Tuning capacitor |

| Cm | 1-5 pF | 1-5 pF | 1-5 pF | Matching capacitor |

| Ldc | 28 nH | 28 nH | 28 nH | Inductor added to the diode for active volume coil decoupling |

| Cdc | 470 pF | 470 pF | 470 pF | DC blocking capacitor |

| Lch | 820 nH | 820 nH | 820 nH | AC blocking inductor |

| Cb | 10.6 pF | 10.6 pF | 10.6 pF | Bridge balun capacitor |

| Lb | 26.5 nH | 26.5 nH | 26.5 nH | Bridge balun inductor |

Isolation between different coils was measured after connecting all the electronics including tuning, matching, decoupling and balun electronics. The S21 measurements indicate -15 dB isolation between the neighboring coils and -22 dB isolation between the next neighboring coils.

Results

Initial performance evaluations of the phased array coil were performed on a phantom. This includes SNR comparison between a single element of the array coil with the phased array coil and SNR comparison between the phased array coil with two different volume coils of diameters 72 mm and 154 mm (provided by the MR scanner manufacturer). Later, the in-vivo performance of the phased array coil was evaluated subjectively. Finally, the performance of the phased array coil under parallel imaging was evaluated by simulations.

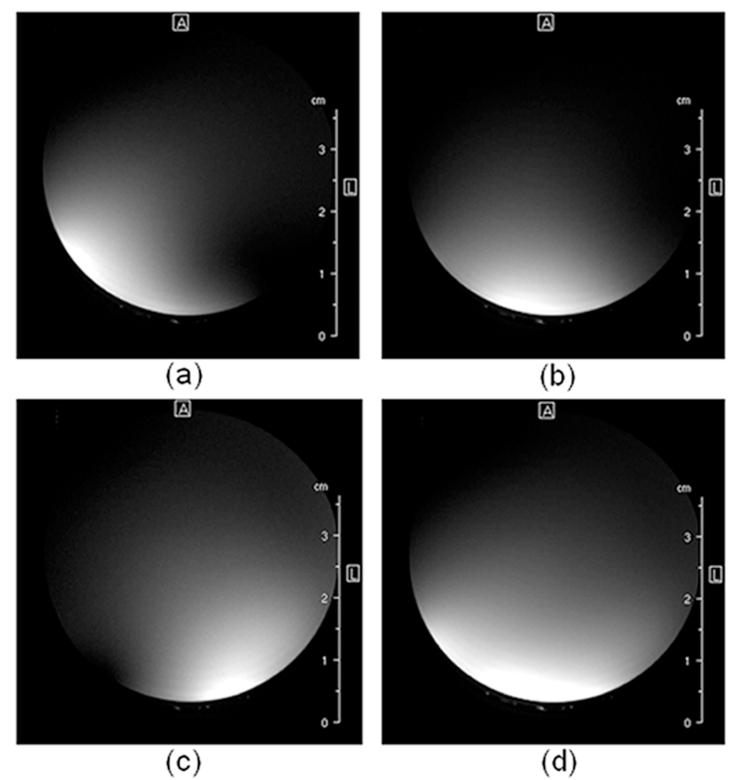

Single element vs. phased array SNR comparison

To compare the SNR of a single element coil (in the array) with the phased array coil, RARE images were acquired from a water phantom using the phased array coil. Individual coil images and a composite image are shown in Fig. 4(a)-(d). SNR was measured at different depths in Fig. 4(b) and Fig. 4(d) and results are shown in Fig. 5. It can be observed from Fig. 5 that the SNR with phased array coil was 32-62 % higher than a single element coil in the thoracic and cervical regions. Also, the phased array coil offers extended coverage laterally. In Fig. 5, it can also be observed that the phased array coil has higher SNR in the thoracic region compared to the cervical region. This is important since the cross-section of the thoracic section is smaller than the cervical section and requires higher SNR for high resolution imaging.

Figure 4.

Individual coil images and the composite image. Individual images from the three different coils are shown in (a), (b), (c) and the composite SOS image is shown in (d).

Figure 5.

SNR comparisons between single and phased coils at different depths. The depth of the thoracic region ranges from 7 ∼ 17 mm and the cervical region from 17 ∼ 20 mm. 100 % SNR corresponds to SNR from the phased array coil at the surface of the phantom.

Phased array vs. volume coil SNR comparison

The performance of the phased array coil was also compared to Bruker’s (vendor’s) volume coils with 72 mm and 154 mm diameters. The SNR comparisons were performed at different depths and the results are shown in Fig. 6. It can be observed from Fig. 6 that phased array coil offered higher SNR than the volume coils in the thoracic and cervical regions (depths 7 - 20 mm). This figure also demonstrates that beyond 22 mm depth the SNR from 72 mm volume coil is higher than the phased array coil, and beyond 28 mm, the SNR from both the volume coils is higher than the phased array coil.

Figure 6.

SNR comparisons between phased array coil and two different volume coils at different depths. 100% SNR corresponds to the SNR from the phased array coil at the surface of the phantom.

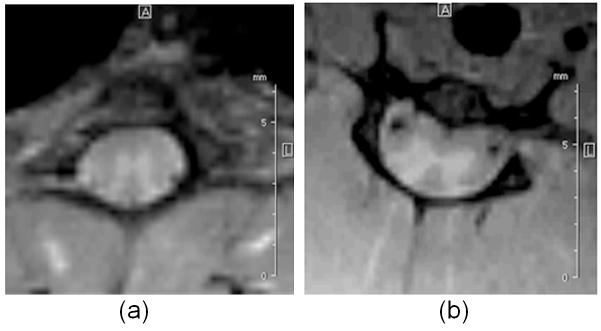

In-vivo images from thoracic and cervical regions

In-vivo spinal cord images are acquired from thoracic and cervical regions and the composite SOS images are shown in Fig. 7. Images in Fig. 7 were subjectively assessed to have sufficient SNR for clear visualization of gray and white matter in the spinal cord.

Figure 7.

In-vivo SOS rat spinal cord images: (a) thoracic and (b) cervical regions.

Phased array coil under parallel imaging

Simulations were performed to evaluate the performance of the phased array coil under parallel imaging. The g-factor reflects the suitability of the coil array for distinguishing signal contributions from the originally aliased locations (11,23). In our simulations, the g-factor maps were derived for acceleration factors of 2 and 3.

Full field-of-view (FOV) images were under-sampled by factors of 2 and 3 in the left-to-right (L-R) direction to generate the reduced FOV images. To derive coil sensitivities, low resolution data was generated from 32 central lines in the k-space of the full FOV images. To remove the proton density and relaxation weightings from the low resolution data, each coil image was divided by the SOS image. The background noise in the resulting images was minimized by simple thresholding and the sensitivity images were smoothed by a 5 × 5 mean filter. The resulting in-vivo coil sensitivity images are shown in Fig. 8(a)-(c).

Figure 8.

SENSE image reconstruction. Individual coil sensitivities are shown in (a)-(c). Simulated g-factor maps for acceleration factors of 1, 2, and 3 are shown in (d), (e) and (f), respectively. SENSE reconstructed images for acceleration factors of 1, 2, and 3 are shown in (g), (h) and (i), respectively. Regions-of-interest (ROI) was drawn at the spinal cord locations in the full FOV image and the g-factor values are quantified in the ROI for acceleration factors of 2 and 3.

To reconstruct the full FOV images from the reduced FOV images, SENSE (11) reconstruction was performed. To analyze the image reconstruction related noise amplifications, g-factor maps (11) were derived for each acceleration factor (Fig. 8(d)-(f)). The SENSE reconstructed images are shown in Fig. 8(g)-(i). An ROI was drawn in Fig. 8(e) and 8(f) to estimate the g-factor statistics in the spinal cord locations. Based on the simulations for an acceleration factor of 2, the following statistics for the g- factor were estimated: mean=1.1; median=1.1; min=1.0; and max=1.7. Since all these statistics were below 2, any severe SENSE image reconstruction-related noise amplifications were not expected in the spinal cord region for acceleration factor 2 (23). However, for an acceleration factor of 3, the statistics for g-factor in the ROI were: mean=2.5; median=2.3; min=1.0; and max=7.0. These statistics indicate that reconstruction-related noise amplifications could be expected in the spinal cord region for acceleration factor of 3 (23).

Discussion

We have described a three element phased array coil for imaging both thoracic and cervical segments of rat spinal cord at 7 T, currently the commonly used field strength for rodent imaging. Different segments of the spinal cord are located at different depths. This poses technical difficulties in selecting an optimal geometry that can be used for imaging both thoracic and cervical regions. In our studies, the dimensions of a single coil in the array were determined based on the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) measurements performed on a phantom with three different surface coils. By selectively choosing the dimensions of the individual elements, we have shown that a three element array coil can provide sufficient SNR for imaging both thoracic and cervical segments. In designing this phased array coil, the most challenging part was to isolate the next neighboring coils. This problem was solved by designing a simple capacitive decoupling network.

Two aspects of our design differentiate our approach from the other published designs: 1) the dimensions of a single coil in the array were chosen to provide high SNR from both superficial (thoracic) and deeper (cervical) regions and 2) low impedance preamplifiers or complicated capacitive decoupling networks were not required for next neighbor decoupling. Thus, this design is simple and easy to reproduce.

As described above, the RARE scan in the current studies takes 15 minutes and 21 seconds to produce sufficient SNR for clear visualization of gray- and white matter in the cord (in-plane resolution = 175 μm). In comparison with implanted coils, it was possible to acquire high resolution spin-echo images (in-plane resolution = 107 μm) with an acquisition time of 9 minutes (2) at 7T. Thus both imaging time and resolution are compromised by using the phased array coils. However, phased array coils offer several advantages that include 1) completely noninvasive imaging, 2) imaging both superficial (thoracic) and deeper (cervical) segments and 3) stable tuning and matching for longitudinal studies. The phased array coils also offer parallel imaging capabilities. Under parallel imaging, it is possible to reduce the imaging time at the expense of some SNR. If reduced SNR can be tolerated, phased array coils under parallel imaging offer additional advantages(13-15). The most significant advantages for animal studies include reduced blurring and geometric distortions. Considering these trade-offs, one can choose a coil based on the requirements of a particular study.

Conclusions

A three element phased array coil is designed for high resolution imaging of rat spinal cord. By judiciously choosing the dimensions of a single element, we have demonstrated that high resolution images can be obtained from both thoracic and cervical regions. This phased array coil employs a simple decoupling network for next neighbor decoupling and the design is easily reproducible. Simulations indicate that the phased array coil can be used for parallel imaging up to an acceleration factor of 2 with potential to the reduce scan times, blurring and geometric distortions. The ability to obtain high resolution spinal cord images with extended spatial coverage relative to implanted coils would allow non-invasive and longitudinal investigations of spinal cord trauma and other pathologies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Marc. S. Ramirez, MSEE, for his help with the electronic design and Chirag B. Patel, MBE, for his help with the animal handling. These studies are supported by NIH/NINDS (Grant # NS045624) to PAN.

References

- 1.Fenyes DA, Narayana PA. In vivo diffusion tensor imaging of rat spinal cord with echo planar imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1999;42(2):300–306. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199908)42:2<300::aid-mrm12>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bilgen M, Elshafiey I, Narayana PA. In vivo magnetic resonance microscopy of rat spinal cord at 7 T using implantable RF coils. Magn Reson Med. 2001;46(6):1250–1253. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ford JC, Hackney DB, Joseph PM, Phelan M, Alsop DC, Tabor SL, Hand CM, Markowitz RS, Black P. A method for in vivo high resolution MRI of rat spinal cord injury. Magn Reson Med. 1994;31(2):218–223. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910310216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ellingson BM, Kurpad SN, Li SJ, Schmit BD. In vivo diffusion tensor imaging of the rat spinal cord at 9.4T. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;27(3):634–642. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim JH, Loy DN, Liang HF, Trinkaus K, Schmidt RE, Song SK. Noninvasive diffusion tensor imaging of evolving white matter pathology in a mouse model of acute spinal cord injury. Magn Reson Med. 2007;58(2):253–260. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roemer PB, Edelstein WA, Hayes CE, Souza SP, Mueller OM. The NMR phased array. Magn Reson Med. 1990;16(2):192–225. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910160203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wright SM, Wald LL. Theory and application of array coils in MR spectroscopy. NMR Biomed. 1997;10(8):394–410. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1492(199712)10:8<394::aid-nbm494>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blaimer M, Breuer F, Mueller M, Heidemann RM, Griswold MA, Jakob PM. SMASH, SENSE, PILS, GRAPPA: how to choose the optimal method. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2004;15(4):223–236. doi: 10.1097/01.rmr.0000136558.09801.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Griswold MA, Jakob PM, Heidemann RM, Nittka M, Jellus V, Wang J, Kiefer B, Haase A. Generalized autocalibrating partially parallel acquisitions (GRAPPA) Magn Reson Med. 2002;47(6):1202–1210. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kyriakos WE, Panych LP, Kacher DF, Westin CF, Bao SM, Mulkern RV, Jolesz FA. Sensitivity profiles from an array of coils for encoding and reconstruction in parallel (SPACE RIP) Magn Reson Med. 2000;44(2):301–308. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200008)44:2<301::aid-mrm18>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pruessmann KP, Weiger M, Scheidegger MB, Boesiger P. SENSE: sensitivity encoding for fast MRI. Magn Reson Med. 1999;42(5):952–962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sodickson DK, Manning WJ. Simultaneous acquisition of spatial harmonics (SMASH): fast imaging with radiofrequency coil arrays. Magn Reson Med. 1997;38(4):591–603. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910380414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neuberger T, Webb A. Radiofrequency coils for magnetic resonance microscopy. NMR Biomed. 2008 doi: 10.1002/nbm.1246.; Epub ahead of print; DOI:10.1002/nbm.124614.

- 14.Pruessmann KP. Parallel imaging at high field strength: synergies and joint potential. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2004;15(4):237–244. doi: 10.1097/01.rmr.0000139297.66742.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wiesinger F, Van de Moortele PF, Adriany G, De Zanche N, Ugurbil K, Pruessmann KP. Potential and feasibility of parallel MRI at high field. NMR Biomed. 2006;19(3):368–378. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beck BL, Blackband SJ. Phased array imaging on a 4.7T/33cm animal research system. Rev Sci Instrum. 2001;72(11):4292–4294. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sutton BP, Ciobanu L, Zhang X, Webb A. Parallel imaging for NMR microscopy at 14.1 Tesla. Magn Reson Med. 2005;54(1):9–13. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang X, Webb A. Design of a capacitively decoupled transmit/receive NMR phased array for high field microscopy at 14.1T. J Magn Reson. 2004;170(1):149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gareis D, Wichmann T, Lanz T, Melkus G, Horn M, Jakob PM. Mouse MRI using phased-array coils. NMR Biomed. 2007;20(3):326–334. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yung AC, Kozlowski P. Signal-to-noise ratio comparison of phased-array vs. implantable coil for rat spinal cord MRI. Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;25(8):1215–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reykowski A, Wright SM, Porter JR. Design of matching networks for low noise preamplifiers. Magn Reson Med. 1995;33(6):848–852. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910330617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cripps SC.RF Power Amplifiers for Wireless Communications 1999Artech House Publishers; Norwood, MA: 02062: [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weiger M, Pruessmann KP, Leussler C, Roschmann P, Boesiger P. Specific coil design for SENSE: a six-element cardiac array. Magn Reson Med. 2001;45(3):495–504. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200103)45:3<495::aid-mrm1065>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]