Abstract

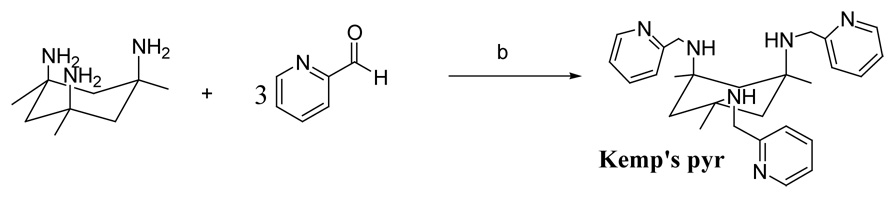

Pre-organized tripodal ligands such as the N-picolyl derivatives of cis,cis-1,3,5-triamino-cis,cis-1,3,5-trimethylcyclohexane (Kemp’s triamine) were prepared as analogs to N,N’,N”- tris(2-pyridylmethyl)-cis,cis-1,3,5-triaminocyclohexane (tachpyr) in hopes of enhancing the rate of formation and stability of the metal complexes. A tricyclic bisaminal was formed via the reduction of the Schiff base while the tri(picolyl) derivative was synthesized via reductive amination of pyridine carboxaldehyde. Their cytotoxicities to the HeLa cell line were evaluated and directly compared to tachpyr and N,N’,N”- tris(2-pyridylmethyl)-tris(2-aminoethyl)amine (trenpyr). Results indicate that N,N’,N”-tris(2-pyridylmethyl)-cis,cis-1,3,5-triamino-cis,cis-1,3,5-trimethylcyclohexane (Kemp’s pyr) exhibits cytotoxic activity against the HeLa cancer cell line comparable to tachpyr (IC50 ~ 8.0 µM). Both Kemp’s pyr and tachpyr show higher cytotoxic activity over the aliphatic analogue of trenpyr (IC50 ~ 14 µM) suggesting that the major contributor to the activity is the ligand’s ability to form a stable and tight complex and that the equatorial/axial equilibrium impacting the complex formation for the cyclohexane-based ligands is not significant.

Introduction

Iron is the most abundant transition metal element in the human body (34–60 mg/kg body weight) 1;2 and has involvement in acid-base reactions, oxidation-reduction catalysis, and bioenergetics. 1 It is essential in all living organisms, yet at the same time highly toxic being implicated in oxidative stress through the production of free radicals such as hydroxyl radical, 3;4 apoptosis, 5;6 and even cancer. 3–5;7 To circumvent the hazardous effects of acquiring redox active iron in the environment, special transport and storage proteins have been developed by nature. Examples of these transport and storage proteins are p97, transferrin, transferrin receptors, and ferritins. 1;8–10

An increased level of expression for these iron transport proteins such as transferrin and its receptor in actively proliferating cells such as hematopoietic cells 11;12 has been shown in a number of studies.11–13 This suggests a heightened need for iron 7;11;13;14 presumably for use in the M2 subunit of the ribonucleotide reductase, 8 the rate-controlling enzyme in DNA synthesis. 11;15 As iron is essential in cell growth, deficiency and deprivation of iron in cell lines such as human lymphocytes, 11;16 HeLa, 17 and erythroblasts 18–20 have been shown to impair DNA synthesis by inhibiting ribonucleotide reductase 13 12;20–22thus preventing cell proliferation. Depletion of iron has also been shown to exert an anti-proliferative effect in various cell lines such as neuroblastoma 23 and lymphocytes, 11 to induce in cell cycle arrest at various stages, and to induce apoptosis. 11;15;24–27

A distinct feature of cancer cells that investigators have exploited in the search for effective chemotherapeutic agents is that tumor cells grow at a rate faster than most normal cells. Hann and coworkers 28 have shown that tumor cells grow better in an iron-rich environment. Consequently, iron deprivation by using metal chelators seems a logical strategy for designing new anticancer drugs to inhibit tumor growth. Effective therapies for human iron-overload diseases such as hemochromatosis, thalassemias, and sickle cell disease demonstrate that metal chelators act as iron-deprivation agents in vivo. Examples of metal chelators that have been considered for cancer therapy are desferrioxamine (DFO), 29–33 pyridoxal isonicotinoyl hydrazones (PIHs) 15;34 and the tripodal amine N,N’,N”-tris(2-pyridylmethyl)-cis,cis-1,3,5-triaminocyclohexane (tachpyr). 27 Tachpyr has been shown to be cytotoxic towards mouse bladder tumor cultured cells (MBT2) with an IC50 ~ 5 µM. 27 In addition to exhibiting a significant cytotoxic effect through the induction of apoptosis, tachpyr’s effects are independent of p53-activated apoptosis 35 offering an advantage over numerous chemotherapeutic drugs.

Tachpyr is based on cis,cis-1,3,5-triaminocyclohexane (tach), which can readily flip from an open all-equatorial conformation into a closed all-axial conformation to encapsulate metal ions (Figure 1). The metal complexes formed with +2 first row transition metals such as copper, zinc and iron show a regular octahedral structure with all three cyclohexane amines in the axial position. 36;37 Synthesis of similar tripodal-based ligands that are pre-organized may enhance the rate of formation and the stability of the metal complex 38–40 formed thereby improving the iron-depleting activity. In this study, use of Kemp’s triamine (cis,cis-1,3,5-triamino-cis,cis-1,3,5-trimethylcyclohexane) which has the same cyclohexane base as tach, was investigated as a platform for new chelation agents. However, unlike tach, the cis amino groups are predisposed in an all-axial conformation by the presence of the three cis methyl groups analogous to Kemp’s acid (Figure 1). 41 The additional pre-organization was hypothesized to increase the rate of formation and stability of the metal complex because less conformational change, i.e., no transition from equatorial to axial configuration, would be required to form the metal complex. In turn, increased biological activity was anticipated. The preference for a triaxial geometry should suppress dechelation, increasing the overall complex stability. As an additional comparison to the pre-organization strategy, the cyclohexane-based ligands of tach and Kemp’s are compared to the more open configuration of the tris(2-aminoethyl)amine (tren) (Figure 1) based analog wherein all three amines and the three pyridyl donors are assembled in more open and flexible aliphatic chains. Synthesis of the tri(picolyl) derivative of Kemp’s triamine (Kemp’s pyr) as an analogue to tachpyr and its cytotoxic activity to HeLa cell lines in comparison to both tachpyr and trenpyr are described in this paper.

Figure 1.

Conformational changes in structures of the tripodal ligands trenpyr, tachpyr, and Kemp’s pyr.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis

Synthesis of Kemp’s pyr began with the preparation of the Kemp’s triamine base framework. The triamine was prepared from the commercially available Kemp’s triacid as described in the literature. 41 A modification of the reported method was employed for the synthesis of the azide intermediate wherein a saturated solution of the sodium azide was used along with a shorter reaction time to obtain yields comparable to those previously reported. For the syntheses of both tachpyr and trenpyr, 5;6;42 the picolyl derivatives were prepared by first forming their corresponding imines (Schiff bases) which were subsequently reduced to the corresponding substituted amines using sodium borohydride. This approach was applied first towards the synthesis of Kemp’s pyr from the respective triamine, however, the expected Schiff base imines were not isolated in the first step of the reaction. Treatment of this product mixture using sodium borohydride afforded no change in composition which indicated that reducible imine groups were not present and that neither was the major product in equilibrium with an imine. Varying the reaction ratio of the starting triamine to the pyridine-2-carboxaldehyde from a 1:3 to 1:2, and even to a 1:1 gave the same major product. Isolation by column chromatography and characterization of the major product yielded a m/z of 350.4 suggesting this product to have only two picolyl arms; proton NMR confirmed this inequivalency as well. Proton NMR also indicated two types of methyl group with a ratio of 2:1 (6H:3H) and a unique CH group (2H) suggesting a plane of symmetry. NOESY experiments indicated no correlation for the methine proton to any methyl or methylene protons and only a weak one to an aromatic proton suggesting that this unique proton was directed away from all other groups. Based on the mass spectral data and 1D and 2D NMR spectroscopic analyses, the major product of this specific route is proposed to be the tricyclic bis(aminal), KP1/2 (Figure 2). The formation of KP1/2 presumably originates from the formation of a mono-imine initially, the double bond of which is then attacked by the neighboring nucleophilic amine producing an aminal. A second imine forms from the third free amine and is then nucleophilically attacked by the neighboring secondary amine forming the third fused ring (Figure 5). This proposed mechanism is probably promoted by the framework of the cyclohexane base of Kemp’s triamine placing the three primary amines in close proximity. Menger and coworkers observed similar behavior with the formation of the cyclic anhydride/acid chloride in the first step of Kemp’s triamine synthesis from the triacid, 41 with the neighboring carboxyl groups acting as amide catalysts. 43

Figure 2.

Synthesis of the tricyclic amine KP1/2; a) benzene, reflux, 12 hr.

Figure 5.

Scheme for the proposed mechanism for the formation of the tricyclic product KP ½.

Due to these complications, the stepwise tris-imine hydride reduction route to synthesize Kemp’s pyr that had been successful for both tachpyr and trenpyr was abandoned. Instead, reductive amination of the pyridine carboxaldehyde using cyanohydridoborate was investigated. 44;45 Reaction of the triamine with the aldehyde afforded a near quantitative yield (85%) of Kemp’s pyr with less than 5% of the tricyclic amine (KP1/2) byproduct (NMR). Isolation and subsequent characterization of Kemp’s pyr by mass spectra and NMR confirmed the product. As expected, the three pyridyl rings and the “benzylic” methylene protons were spectroscopically equivalent as expected for a C3-symmetric substance.

Structural Analysis: Cu(II) and Zn(II)

To confirm the structure of Kemp’s pyr and investigate its metal complexing properties, the Cu(II) and Zn(II) complexes were prepared. Two independent complexes (a and b) were found in the asymmetric unit for the Cu(II) complex of Kemp’s pyr (Figure 6), both consisting of a mononuclear [Cu(II)-Kemp’s pyr] cation each with two BF4− anions and three ethanol solvents associated with it. Selected bond distances and bond angles are listed in Table 2.

Figure 6.

ORTEP drawing of the two isomers of the copper(II) complex of Kemp’s pyr (a and b) showing 30% probability thermal ellipsoids, and the atom-labeling scheme.

Table 2.

Selected distances (Å) and angles (°) for the isomers of the copper(II) complexes of the Kemp’s pyr (a and b).

| A | B | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Bond lengths | Bond lengths | ||

| Cu1-N1 | 2.028(4) | Cu2-N7 | 2.044(4) |

| Cu1-N2 | 2.017(4) | Cu2-N8 | 2.135(4) |

| Cu1-N3 | 2.051(4) | Cu2-N9 | 2.188(4) |

| Cu1-N4 | 2.174(4) | Cu2-N10 | 2.168(4) |

| Cu1-N5 | 2.705(8) | Cu2-N11 | 2.218(4) |

| Cu1-N6 | 2.090(4) | Cu2-N12 | 2.066(4) |

| Bond angles | Bond angles | ||

| N2-Cu1-N1 | 83.48(16) | N7-Cu2-N12 | 167.85(16) |

| N2-Cu1-N3 | 174.40(17) | N7-Cu2-N8 | 81.74(16) |

| N1-Cu1-N3 | 93.78(16) | N12-Cu2-N8 | 90.69(15) |

| N2-Cu1-N6 | 91.55(16) | N7-Cu2-N10 | 96.58(16) |

| N1-Cu1-N6 | 163.20(16) | N12-Cu2-N10 | 92.95(16) |

| N3-Cu1-N6 | 92.42(17) | N8-Cu2-N10 | 90.43(15) |

| N2-Cu1-N4 | 94.93(15) | N7-Cu2-N9 | 93.58(16) |

| N1-Cu1-N4 | 104.16(16) | N12-Cu2-N9 | 95.65(15) |

| N3-Cu1-N4 | 80.98(16) | N8-Cu2-N9 | 167.75(15) |

| N6-Cu1-N4 | 92.22(17) | N10-Cu2-N9 | 78.81(15) |

| N2-Cu1-N5 | 93.80(17) | N7-Cu2-N11 | 91.52(16) |

| N1-Cu1-N5 | 87.97(17) | N12-Cu2-N11 | 80.22(16) |

| N3-Cu1-N5 | 90.97(17) | N8-Cu2-N11 | 99.00(15) |

| N6-Cu1-N5 | 76.32(17) | N10-Cu2-N11 | 168.37(15) |

| N4-Cu1-N5 | 165.77(17) | N9-Cu2-N11 | 92.41(15) |

Isomer b is a six-coordinate complex that can be described as an antitrigonal geometry (ideal φ = 60°) distorted towards trigonal prism (ideal φ = 0°). 46 The three cyclohexyl amino Ncy atoms and the three Npy atoms form two staggered equilateral triangles (φ= 46.2°) with the Cu(II) metal located between the two triangles. This isomer also shows the tetragonal distortion that is typical for a hexacoordinate Cu(II) causing a Jahn-Teller effect. In this structure, the two axial bonds (Cu2-N7 and Cu2-N12) have shorter bond lengths (2.057 Å) than the rest of the Cu-N bond distances (2.18 Å) opposite of the elongated axial bonds found in the Cu[tachpyr] complex. 47

Isomer a, on the other hand, is a five-coordinate complex that can be described as a distorted square pyramidal geometry with one pyridyl arm unbound to the Cu(II). The average coordinated Cu-Ncy and Cu-Npy are 2.100 Å and 2.039 Å, respectively. The third Cu-Npy distance is 2.704 Å and is longer than the corresponding sum of van der Waals radii (2.46 Å) 48 indicating that it is not coordinated to the Cu(II) ion. However, unlike the Cu(II) complex of tach-6-Me-pyr wherein the third pyridine ring is entirely twisted away from the copper center due to the steric effects of three methyl groups on the pyridine rings, 47 the third pyridine group on a still faces the Cu(II) center potentially blocking access to the sixth coordination site.

Surprisingly, the average torsion angle for isomer a (47.8°) is smaller than that for isomer b (49.2°) indicating that there is possibly more strain in the five-coordinate complex than there is on the six-coordinate. This may indicate that the six-coordinate is the favored isomer. Also, as expected, these torsional angles are smaller than those found in different complexes of tach derivatives, which typically average from 49° to 53°. 49 Presumably this is due to the presence of the trimethyl groups on the equatorial positions for the Kemp’s based ligand. In accordance with what is observed for the tach-based ligands, we would expect that complexation of a larger ionic radius metal ion would spread the amines further apart and flatten the cyclohexyl ring. We also would expect that such a complex of a very large metal ion would concomitantly form a less stable complex with Kemp’s pyr than tachpyr due to the strain in the cyclohexyl ring.

To observe the lability of the metal in aqueous solution, a solution of the complex was studied by RP-HPLC using a gradient of 100% aqueous buffer of 0.05M HOAc/NEt3 (pH 6.5) to 100% MeOH in 25 minutes. A single peak was observed (Rt = 16.3 min vs Rt = 18 min for Cu[tachpyr]) with no visible free ligand (Rt = 24.95 min) under these conditions indicating that the complex stays intact.

The Zn(II) complex of Kemp’s pyr was also synthesized to further confirm structural details as well as to test the ability of the Kemp’s pyr to form stable metal complexes with other metals. The stability of the corresponding Zn(II) complex of Kemp’s pyr was observed in both the NMR (D2O) and the RP-HPLC. However, unlike the Cu(II) complex of Kemp’s pyr, the Zn(II) complex forms a six-coordinate complex in solution as observed from the equivalency of the pyridine rings in the proton NMR of the complex.

Cytotoxicity studies indicate that Kemp’s pyr (ave. IC50 = 8.0 µM) has comparable activity to tachpyr (ave. IC50 = 8.8 µM), indicating that while an equilibrium may exist between the two isomers, Kemp’s pyr still chelates and sequesters essential metals. Presumably, this is the cause of the cytotoxicity. 27 In comparison, both these complexes are somewhat more cytotoxic than that measured for the more open, acyclic configuration of trenpyr (IC50 = 13.5 µM). This may be attributed to the differences in rate of formation for the trenpyr metal complex, since this ligand must undergo a larger entropic change than either the cyclohexane-based tachpyr or Kemp’s pyr. Ultimately, small differences in their stability constants, currently being studied, may also contribute to the differences in their cytotoxicity.

As expected, the starting material, Kemp’s triamine (ave. IC50 = 658 µM), has little or no cytotoxicity as was also observed for the base tach amine. 36 This is due to the inability of the ligand to form a tight complex with the metal. This is observed in the RP-HPLC of the metal complex solution wherein no peak was observed for the complex.

The tricyclic KP½ (ave. IC50 = 834 µM) also shows little or no cytotoxicity, as it is likely limited to forming the more open four or five coordinate complex making it more labile. This is not unlike the Cu(II) complex with tach-6-Me-pyr,47 which is unable to sequester metal ions effectively in an in vitro cell culture milieu.

Conclusions

The geometry and conformational locking of the cyclohexane framework of Kemp’s triamine increases the availability and thus nucleophilicity of the three triaxial primary amines as compared to the tach analogue. This favors formation of tricyclic KP½ over Kemp’s pyr as the thermodynamic product. Though the cytotoxicity of this tricyclic ligand is not significant in this arena, this intermediate may be used in the development of other novel metal chelators, as this triamine provides a novel platform/base for design of metal chelators. Direct reductive amination provides the desired kinetic product, Kemp’s pyr, with minimal production of KP½.

Preorganization of the pyridyl substituted amines of the tripod into the triaxial conformation appears not to increase the cytotoxicity of the ligand. Although both these ligands show higher cytotoxicity as compared to the aliphatic analogue trenpyr (IC50 = 13.5 µM), we surmise that the ability of the ligand to form a stable complex is a major contributor in the cytotoxicity of these ligands. Kemp’s pyr is able to form stable complexes with both copper and zinc and may be able to form stable complexes with other metals such as iron. As there seems to be more strain in the cyclohexyl ring on complex formation, larger metal cations may be unable to form stable complexes with Kemp’s pyr.

Additionally, substitution at the equatorial position, i.e., addition of the three methyl groups in Kemp’s pyr, also appears not to measurably impact the cytotoxicity of tachpyr. This position may be suitable for further derivatization to create novel tachpyr/ Kemp’s pyr derivatives altering lipophilicity, pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics, as well as furthering the design of bifunctional ligands for conjugation to potential drug delivery systems.

In terms of evaluating these potential chelating agents for the development of new chemotherapeutic drugs, tachpyr remains superior to Kemp’s pyr with the overall yield for synthesis of the latter being low (~25%) as compared to tachpyr (~60%) from the respective triacid starting materials.

Experimental Section

General Experimental Procedures

Proton and 13C NMR spectra were obtained by using a Gemini or a Mercury 300 MHz spectrometer. Chemical shifts are reported in ppm on the δ scale relative to TMS or TSP for 1H NMR spectra and relative to the solvent (CDCl3) or an external standard (methanol for D2O) for 13C NMR spectra. Proton chemical shifts are annotated as follows: ppm (multiplicity, integration, coupling constant in Hz). The positive-ion mode FAB/MS spectra were obtained using a JEOL SX 102 GC/direct probe. Time-of-flight mass spectra using an electrospray ionization mode (ESI/TOF/MS) were obtained using Waters' LCT Premier with the Waters’1525 microliter binary HPLC pump. Elemental analyses were obtained from the Department of Chemistry University of Florida Spectroscopic Services (Gainesville, FL).

Analytical HPLC were performed using a Beckman system equipped with Model 114M pumps controlled by System Gold software and a Model 165 dual wavelength UV detector (254 and 280 nm). Chromatography was performed on a Beckman Ultrasphere ODS C18 reversed phase column (5µm particles, 4.6 × 250 mm) with a guard column (8 µm particles, 4.6 × 7.5 mm) using a binary solvent (A = 0.05M Et3N-HOAc pH ~6.5, B = MeOH) linear gradient (100 % B over 25 min) at a rate of 1.00 mL/min. A secondary system using a linear gradient of acetonitrile (A = water, B = MeCN, 100% B over 25 min) at a rate of 1.00 mL/min was also used to confirm purity.

Materials

All solvents and reagents were obtained from Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), Mallinckrodt Chemicals (Philipsburg, NJ), Fisher Scientific (Atlanta, GA), Lancaster (Windham, NH), Fluka (Ronkonkoma, NY), or Alfa (Danvers, MA) and were used as received.

Tachpyr and trenpyr were prepared as previously reported. 4–6;42 Kemp’s triamine was synthesized according to the scheme developed by Menger and coworkers. 41

Aluminum Oxide Type T (Activity I) gel for column chromatography (70–230 mesh ASTM), silica gel for column chromatography (230–400 mesh ASTM), aluminum oxide Type T pre-coated plates for TLC, and silica gel 60 F pre-coated plates for TLC were obtained from EM Science (Gibbstown, NJ).

Synthesis of 3,5-bis(2-pyridyl)-cis,cis-1,7,9-trimethyl-2,4,6-triazatricyclo[5.3.1.0~4,9~]undecane (KP 1/2)

Kemp’s triamine (HCl)3 (0.10 g, 0.32 mmole) was dissolved in a solution of NaOH (0.04 g, 0.95 mmole) in H2O (1.0 mL). Benzene (25 mL) was added to the aqueous solution and water was removed by refluxing the mixture using a Dean-Stark apparatus for 4 hours. The solution was then cooled to room temperature after which 2-pyridinecarboxaldehyde (0.040 mL, 0.32 mmole) was added. The mixture was refluxed overnight and solvent removed in vacuo to give a brown oil. The product was purified by column chromatography using a slow gradient of MeOH (1–10%) in CH2Cl2 (0.07 g, 75% yield). The HCl acid form was isolated by bubbling HCl into a solution of KP 1/2 in dioxane. FAB/MS: m/z [C21H27N5 + H]+ calcd: 350.2, found: 350.3. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 1.23 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.52 (d, 2H, J 16 Hz, CH2), 1.65 (s, 6H, CH3), 1.76 (d, 2H, J 20 Hz, 11 CH2), 2.42 (d, 2H, J 16 Hz, CH2), 3.85 (s, 2H, CH), 6.80 (q, 1H, J 3.5 Hz, Ar), 7.15 (dd, 2H, J 6, 1 Hz, Ar), 7.28 (t, 1H), 7.75 (dt, 1H, J 8.1, 2.3 Hz, Ar), 8.12 (dd, 1H, J 4.6, 2.3 Hz, Ar), 8.29 (dd, 1H, J 4.6, 2.3 Hz, Ar), 9.24 (d, 1H, J 8.1 Hz, Ar), 10.0 (broad, 2H, NH). 13C NMR with DEPT (CDCl3): δ(CH3) 27.2, 29.8; (CH2) 42.6, 47.1, 47.9; (CH) 68, 121.0, 123.0, 124.8, 127.1, 136.0, 138.0, 148.0, 148.1; (Cquat) 51.8, 53.5, 159, 160.3. Analysis calculated for C21H27N5•3.75HCl•C4H4O2: C, 52.56; H, 7.11; N, 10.58. Found (C21H27N5•3.75HCl•2C4H8O2): C, 52.65; H, 6.69; N, 10.76.

Synthesis of cis,cis-1,3,5-trimethyl-N,N’,N’-tris(2-pyridylmethyl)-cis,cis-1,3,5-triaminocyclohexane (Kemp’s pyr)

Triethylamine (~ 210 µL) was added to a suspension of Kemp’s triamine (HCl)3 (0.16 g, 0.51 mmole) in MeOH (3.0 mL) adjusting the pH of the solution to 6.0 to 6.5. Sodium cyanoborohydride (0.10 g, 1.63 mmole) and 2-pyridinecarboxaldehdye (0.05 mL, 1.53 mmole) were then added to the solution and the mixture stirred at room temperature for 3 days. The pH of the solution was checked regularly and maintained at ~6.5 by addition of either glacial acetic acid or triethylamine. The solvent was then removed in vacuo and the solid taken up in CH2Cl2 (25 mL). The mixture was then washed with cold H2O (3 × 10 mL) and the organic layer dried over MgSO4 for 30 min. The organic layer was filtered and the solvent was removed in vacuo to give a brown oil. The product was purified on a basic alumina column eluted using a slow gradient of MeOH (1–10%) in CH2Cl2 (0.19 g, 85% yield). The HCl acid form is isolated as by adding a HCl(g) saturated solution of dioxane to a solution of the Kemp’s pyr in dioxane. FAB/MS: m/z [C27H36N6 + H]+ calcd: 445.3, found: 445.4. 1H NMR of the free base (CDCl3): δ 1.20 (s, 9H, CH3), 1.27 (s, 2H, CH2), 1.25 (d, 2H, J 13.3 Hz, CH2), 2.34 (d, 2H, J 13.3 Hz, CH2), 3.95 (s, 6H, CH2), 6.98 (dt, 3H, J 6.0, 1.7 Hz, Ar), 7.06 (d, 3H, J 8.6 Hz, Ar), 7.33 (dt, 3H, J 8.6, 1.7 Hz, Ar), 8.08 (dt, 3H, J 5.1, 1.7 Hz, Ar); 13C NMR (CDCl3): 30.5, 45.7, 48.6, 54.2, 121.3, 122.2, 136.1, 148.8, 160.8. Analysis calculated for C27H36N6•6HCl•4H2O: C, 44.07; H, 6.86; N, 11.43. Found: (C27H36N6•6HCl•4H2O) C, 44.31; H, 6.99; N, 11.24.

Synthesis of the Cu(II) complex of Kemp’s pyr

A solution of Kemp’s pyr (0.10 g, 0.23 mmole) in MeOH (2.0 mL) was added dropwise to a stirred solution of copper(II) tetrafluoroborate (0.08 g, 0.23 mmole) in MeOH (1.0 mL) under Argon. The mixture was then stirred for 3 hours at 0°C. The green precipitate that formed was then filtered off, washed with cold MeOH, and dried in vacuo (0.09 g, 60% yield). Single crystals were grown by diffusing Et2O in the EtOH solution of the Cu(II) complex. FAB/MS: m/z [(C27H36N6)Cu(OH2)(OH)]+ calcd: 542.8, found: 542.8, m/z [C27H36N6 + H]+ calcd: 445.3, found: 445.2. Analysis calculated for (B2C27CuF8H36N6•1.75H2O) C, 45.44; H, 5.58; N, 11.79. Found: (B2C27CuF8H36N6•1.75 H2O) C, 45.428; H, 5.292; N, 11.688.

Synthesis of Zn(II) complex of Kemp’s pyr

The zinc complex of Kemp’s pyr was synthesized as described above of the analogous Cu(II) complex using an equimolar amount zinc(II) chloride. ESI/TOF/MS: m/z [(C27H36N6)ZnCl]+ calcd: 544.3, found: 543.1, m/z [(C27H36N6)Zn(HCO2−)]+ calcd: 554.3, found: 553.2. H NMR (D2O, TSP): δ 1.35 (s, 9H, CH3), 1.68 (d, 2H, J 27.6 Hz, CH2), 2.35 (d, 2H, J 15.6 Hz, CH2), 3.85 (t, 2H, J 8.4 Hz, CH2), 4.28 (d, 6H, J 8.4 Hz, CH2), 7.38 (t, 3H, J 6 Hz, Ar), 7.51 (d, 3H, J 6 Hz, Ar), 7.55 (d, 3H, J 8 Hz, Ar ), 8.02 (t, 3H, J 8 Hz, Ar). 13C NMR (D2O): 29.6, 43.9, 46.0, 56.2, 125.0, 125.2, 141.5, 147.3, 158.0.

Crystallographic Data

Crystal data and refinement details are reported in Table 1. A single crystal of Cu(II)-Kemp’s pyr (0.40 × 0.20 × 0.15 mm), crystallized by diffusion of diethyl ether into a solution in ethanol, was mounted using Paratone® oil onto a glass fiber and cooled to the data collection temperature of 120° K. Data were collected on a Brüker-AXS APEX CCD diffractometer with 0.71073 Å Mo-Kα radiation. Unit cell parameters were obtained from 60 data frames, 0.3° ω, from three different sections of the Ewald sphere. No symmetry higher than triclinic was evident from the diffraction data. Solution in the centrosymmetric space group P-1 yielded chemically reasonable and computationally stable results of refinement. The data-set was treated with SADABS adsorption corrections based on redundant multiscan data 50 Tmax/Tmin = 1.143. Two symmetry-unique isomers were located in the asymmetric unit yielding Z = 2, and Z’ = 2. Data set was treated with Squeeze filter (Platon) 51 consistent with initial solutions showing three ethanol molecules co-crystallized for every two copper complexes. All non-hydrogen atoms were refined with anisotropic displacement parameters. All hydrogen atoms were treated as idealized contributions. Structure factors are contained 13 in the SHELXTL 6.12 program library 52. The CIF is available from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center.

Table 1.

Crystallographic data and refinement details for copper(II) complexes of Kemp’s pyr (a and b).

| Cu(II) Kemp’ pyr | |

|---|---|

| Formula | C30H45B2CuF8N6O1.50 |

| Molecular Weight | 750.88 |

| Crystal system, space group | Triclinic, P-1 |

| a (Å) | 13.0824(17) |

| b (Å) | 14.0531(19) |

| c (Å) | 19.298(3) |

| α (°) | 71.371(2) |

| β (°) | 76.996(2) |

| γ (°) | 87.301(2) |

| V (Å3) | 3274.6(8) |

| Z, Z’ | 2, 2 |

| Dcalc (mg/m3) | 1.523 |

| Absorption coefficient (mm−1) | 0.751 |

| Parameters | 799 |

| Goodness-of-fit on F2 | 1.025 |

| Final R indices [I>2σ(I)] | R1=0.0694, wR2=0.1475 |

| R indices (all data) | R1=0.1117, wR2=0.1623 |

Quantity minimized=R(wF2) = {Σ[w(Fo2 −Fc2)2]/Σ(wFo2)2}1/2 : R(F) = ΣΔ/Σ(Fo), Δ = |(Fo − Fc)| : w = [σ2(Fo2) + (aP)2 + bP]−1 : P = [2Fc2 + Max(Fo,0]/3

In vitro cell proliferation assay

HeLa cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection and grown in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C in DME medium (Gibco BRL) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and penicillin/streptomycin. Cells (2 × 103) were plated in 96 well tissue culture dishes and allowed to attach overnight before test compounds were added. Six replicate cultures were used for each point. After 72 h, viability was assessed using an MTT assay, in which (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide is added to the medium and the formation of a reduced product is assayed by measuring the optical density at 560/650 nm after 3 hours. Color formation is proportional to viable cell number 53.

Supplementary Material

Characterization data for the compounds are available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Figure 3.

Synthesis of Kemp’s pyr via reductive amination; b) NaCNBH3 in methanol at pH 6.5, 3 days at room temperature.

Figure 4.

MTT assay for the HeLa cell treatment with the different triamines after 72 hours. (•) tachpyr, (◦) trenpyr, (▼) Kemp’s pyr, (■) KP1/2, and (◊) Kemps’ triamine.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported in part by grant No.DK 57781 (S.V.T.) from the National Institutes of Health and in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH (National Cancer Institute).

References

- 1.Kaim W, Schwederski B. Bioinorganic Chemistry: Inorganic Elements in the Chemistry of Life. An Introduction and Guide. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.; 1996. Historical Background, Current Relevance and Perspectives; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Helmut Beinert. Development of the Field and Nomenclature. Lovenberg, Walter. [1], 1–36. 1973. In: Horecker, Bernard, Kaplan, Nathan O, Marmur, Julius, Scheraga, Harold A, editors. New York, Academic Press, Inc. Molecular Biology, An International Series of Monographs and Textbooks. 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halliwell B, Gutteridge JMC. Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine. Third ed. New York: Oxford University Press Inc.; 1999. The chemistry of free radicals and related 'reactive species'; pp. 36–104. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deroche A, Morgenstern-Badarau I, Cesario M, Guilhem J, Keita B, Nadjo L, Houée-Levin C. A seven-coordinate manganese(II) complex formed with a single tripodal heptadentate ligand as a new superoxide scavenger. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:4567–4573. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morgenstern-Badarau I, Lambert F, Renault JP, Cesario M, Maréchal J-D, Maseras F. Amine conformational change and spin conversion induced by metal-assisted ligand oxidation: from the seven-coordinate iron(II)-TPAA complex to the oxidized iron(II)-(py)3 tren isomers. Characterization, crystal structures, and density functional study. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2000;297:338–350. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoselton MA, Wilson LJ, Drago RS. Substituent effects on the spin equilibrium observed with hexadentate ligands on iron(II) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1975;97:1722–1729. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brittenham GM, Weiss G, Brissot P, Lainê F, Guillygomarc'h A, Guyader D, Moirand R, Deugnier Y. Clinical consequences of new insights in the pathophysiology of disorders of iron and heme metabolism. Am. Soc. Hematol. 2000:39–50. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2000.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cazzola M, Bergamaschi G, Dezza L, Arosio P. Manipulation of cellular iron metabolism for modulating normal and malignant cell proliferation: Achievements and prospects. Blood. 1990;75:1903–1919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richardson DR. Mysteries of the transferrin-transferrin receptor 1 interaction uncovered. Cell. 2004;116:486–485. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00165-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Torti, Suzy V, Planalp, Roy P, Brechbiel, Martin W, Park, Gyungse, Torti, Frank M. Abraham, Nadar. [6] New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. Molecular Biology of Hematopoiesis; 1999. Iron chelation in cancer therapy; pp. 381–389. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lederman HM, Cohen A, Lee JWW, Freedman MH, Gelfand EW. Desferrioxamine: A reversible S-phase inhibitor of human lymphocyte proliferation. Blood. 1984;64:748–753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffbrand AV, Ganeshaguru K, Hooton JWL, Tattersall MHN. Effect of iron deficiency and desferrioxamine on DNA synthesis in human cells. Br. J. Hematol. 1976;33:517–526. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1976.tb03570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown NC, Elliasson R, Reichard P, Thelander L. Spectrum and iron content of protein B2 from ribonucleotide diphosphate reductase. Eur. J. Biochem. 1969;9:512. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1969.tb00639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schafer AI, Bunn HF. Iron-deficiency and Iron-loading Anemias. In: Petersdorf RG, Adams RD, Braunwald E, Isselbacher KJ, Martin JB, Wilson JD, editors. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. Tenth ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company; 1983. pp. 1848–1853. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao J, Richardson DR. The potential of iron chelators of the pyridoxal isonicotinoyl hydrazone class as effective antiproliferative agents, IV: The mechanisms involved in inhibiting cell-cycle progression. Blood. 2001;98:842–850. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.3.842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joynson DHM, Jacobs A, Murray-Walker D, Dolby AE. Defect of cell-mediated immunity in patients with iron-deficiency anaemia. Lancet. 1972;300:1058–1059. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(72)92340-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robbins E, Pederson T. Iron: Its intracellular localization and possible role in cell division. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1970;66:1244–1251. doi: 10.1073/pnas.66.4.1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hill RS, Petitt JE, Tattersall MHN, Kiley N, Lewis SM. Iron deficiency and dyserythropoiesis. Br. J. Haematol. 1972;23:507–512. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1972.tb07085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hershko CH, Karsai A, Eylon L, Izak G. The effect of chronic iron deficiency on some biochemical functions of the human hemopoietic tissue. Blood. 1970;36:321–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van der Weyden M, Rother M, Firkin B. Megaloblastic maturation masked by iron deficiency: A biochemical basis. Br. J. Haematol. 1972;22:299–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1972.tb05676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brockman RW, Shaddix S, Stringer V, Adamson D. Enhancement by desferrioxamine of inhibition of DNA synthesis by ribonucleotide reductase inhibitors. P. Am. Assoc. Canc. Res. 1972;13:88. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laster WR, Jr, Brockman RW. Enhancement of the activity of 5-hydroxypyridine-2-carboxaldehyde thiosonicarbazone (HCT) by desferrioxamine mesylate (Desferal(R)) in vivo. Proceedings of the American Association of Cancer Research. 1973;14:18. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Le NTV, Richardson DR. The role of iron in cell cycle progression and the proliferation of neoplastic cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2002;1603:31–46. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(02)00068-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richardson DR. Analogues of pyridoxal isonicotinoyl hydrazone (PIH) as potential iron chelators for the treatment of neoplasia. Leuk. Lymphoma. 1998;31:47–60. doi: 10.3109/10428199809057584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rakba N, Loyer P, Gilot D, Delcros JG, Glaise D, Baret P, Piere JL, Brissot P, Lescoat G. Antiproliferative and apoptotic effects of O-Trensox, a new synthetic iron chelator, on differentiated human hepatoma cell lines. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:943–951. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.5.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aouad F, Florence A, Zhang Y, Collins F, Henry C, Wad RJ, Crichton RR. Evaluation of new iron chelators and their therapeutic potential. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2002;339:470–480. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Torti SV, Torti FM, Whitman SP, Brechbiel MW, Park G, Planalp RP. Tumor cell cytotoxicity of a novel metal chelator. Blood. 1998;92:1384–1389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hann H-WL, Stahlhut MW, Blumberg BS. Iron nutrition and tumor growth: Decreased tumor growth in iron-deficient mice. Cancer Research. 1988;48:4168–4170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blatt J, Stitely S. Antineuroblastoma activity of desferrioxamine in human cell lines. Cancer Research. 1987;47:1749–1750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Becton DL, Bryles P. Desferioxamine inhibition of human neuroblastoma viability and proliferation. Cancer Research. 1988;48:7189–7192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Donfrancesco A, Deb G, Dominici C, leggi D, Castello MA, Helson L. Effects of a single course of desferioxamine in neuroblastoma patients. Cancer Research. 1990;50:4929–4930. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Donfrancesco A, Deb G, Dominici C. Desferioxamine, cyclophosphamide, etoposide, carboplatin, and thiotepa (D-CECal): A new cytoreductive chelation-chemotherapy regimen in patients with advanced neuroblastoma. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 1992;15:319–322. doi: 10.1097/00000421-199208000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Donfrancesco A, de Bernardi B, Carli M. Desferioxamine (D) followed by cytoxan (C), etoposide (E), carboplatin (Ca), thio-TEPA (T), induction regimen in advanced neuroblastoma. Eur. J. Cancer. 1995;31A:612–615. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(95)00068-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Richardson DR. Analogues of pyridoxal isonicotinoyl hydrazone (PIH) as potential iron chelators for the treatment of neoplasia. Leuk. Lymphoma. 1998;31:47–60. doi: 10.3109/10428199809057584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abeysinghe RD, Greene BT, Haynes R, Willingham MC, Turner J, Planalp RP, Brechbiel MW, Torti FM, Torti SV. p53-Independent apoptosis mediated by tachpyridine, an anti-cancer iron chelator. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22:1607–1614. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.10.1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park G, Lu FH, Ye N, Brechbiel MW, Torti SV, Torti FM, Planalp RP. Novel iron complexes and chelators based on cis,cis-1,3,5-triaminocyclohexane: iron-mediated ligand oxidation and biochemical properties. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 1998;3:449–457. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park G, Ye N, Rogers RD, Brechbiel MW, Planalp RP. Effect of metal size on coordination geometry of N,N′, N″-tris(2-pyridylmethyl)- cis,cis-1,3,5-triaminocyclohexane: synthesis and structure of [MIIL](ClO4)2 (M = Zn, Cd and Hg) Polyhedron. 2000;19:1155–1161. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hancock RD, Martell AE. Ligand design for selective complexation of metal ions in aqueous solution. Chem. Rev. 1989;89:1875–1914. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Busch DH. The compleat coordination chemistry - one practioner's perspective. Chem. Rev. 1993;93:847–860. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hou Z, Stack TDP, Sunderland CJ, Raymond KN. Enhanced iron(III) chelation through ligand predisposition: syntheses, structures and stability of tris-catecholate enterobactin analogs. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 1997;263:341–355. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Menger FM, Bian J, Azov VA. A 1,3,5-triaxial triaminocyclohexane: The triamine corresponding to Kemp's triacid. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002;41:2581–2584. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020715)41:14<2581::AID-ANIE2581>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bowen T, Planalp RP, Brechbiel MW. An improved synthesis of cis,cis-1,3,5-triaminocyclohexane. Synthesis of novel hexadentate ligand derivatives for the preparation of gallium radiopharmaceuticals. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1996;6:807–810. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Menger FM, Ladika M. Fast hydrolysis of an aliphatic amide at neutral pH and ambient temperature: A peptidase model. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988;110:6794–6796. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Borch R, Durst HD. Lithium cyanohydridoborate, a versatile new reagent. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1969;91:3996–3997. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Borch RF, Bernstein MD, Durst HD. The cyanohydridoborate anion as a selective reducing agent. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1971;93:2897–2904. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fleischer EB, Gebala AE, Swift DR, Tasker PA. Trigonal prismatic-coctahedral coordination. Complexes of intermediate geometry. Inorg. Chem. 1972;11:2775–2784. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Park G, Dadachova E, Przyborowska A, Lai S, Ma D, Broker G, Rogers RD, Planalp RP, Brechbiel MW. Synthesis of novel 1,3,5-cis,cis-triaminocyclohexane ligand based Cu (II) complexes as potential radiopharmaceuticals and correlation of structure and serum stability. Polyhedron. 2001;20:3155–3163. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bondi A. van der Waals volumes and radii. J. Phys. Chem. 1964;68:441–451. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hilfiker KA, Brechbiel MW, Rogers RD, Planalp RP. Tricationic metal complexes ([ML][NO3]3, M = Ga, In) of N,N′,N″-tris(2-pyridylmethyl)-cis-1,3,5-triaminocyclohexane: Preparation and structure. Inorg. Chem. 1997;36:4600–4603. doi: 10.1021/ic9614024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sheldrick GM. SADABS adsorption corrections program. Bruker-AXS; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vandersluis P, Spek AL. Bypass - An effective method for the refinement of crystal structures containing disordered solvent regions. Acta Crystallogr., A. 1990;46:194–201. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sheldrick GM. SHELXTL version 6.12 program library. Bruker-AXS; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mossman T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: Application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Characterization data for the compounds are available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.