Abstract

The development of a diastereoselective, three-step strategy for the construction of substituted tetrahydrofurans from alkenyl aldehydes based on the tandem Mukaiyama aldol-lactonization process and Mead reductive cyclization of keto β-lactones is reported. Stereochemical outcomes of the TMAL process are consistent with models established for Lewis acid-mediated additions to α-benzyloxy and β-silyloxy aldehydes while reductions of the five-membered oxocarbenium ions are consistent with Woerpel’s models. Further rationalization for observed high diastereoselectivity in reductions of α-silyloxy 5-membered oxocarbenium ions based on stereoelectronic effects are posited. A diagnostic trend for coupling constants of γ-benzyloxy β-lactones was observed that should enable assignment of the relative configuration of these systems.

Introduction

Tetrahydrofurans (THFs) are common heterocyclic motifs in natural products and thus many routes have been developed to access these moieties.1 These approaches can be divided into three major synthetic strategies (Figure 1). In one strategy, an oxygen nucleophile displaces, adds to, or opens an activated group (G) such as a leaving group (e.g. mesylate),2 an olefin (e.g. iodoetherification),3 or a strained ring (e.g. epoxide)4 to form a new C-O bond (Type I). In another strategy, a nucleophile adds to an oxocarbenium intermediate and a new C-C or C-H bond is formed (Type II).5 Finally, several miscellaneous strategies have been developed1 including ring contractions of various six-membered rings such as tetrahydropyrans6 and δ–lactones.7

Figure 1.

General Routes to Tetrahydrofurans

Some of the most elegant and efficient approaches to THFs fall into the last category (Type III). Overman developed the Prins-pinacol route to THFs8 that has been applied to trans-kumausyne and other members of the Laurencia family of marine natural products,9 as well as (−)-citreoviral10 and briarellin E.11 Roush and Micalizio12 refined and expanded the [3+2] annulation of aldehydes and allylsilanes toward THFs first reported by Panek.13 This strategy had been applied to pectenotoxin II,14 amphidinolide F,15 asimicin,16 (+)-bullatacin,17 angelmicin B,18 and haterumalide ND.19 Lee developed a radical cyclization approach to THFs20 and utilized this method in the total synthesis of pamamycin 607,21 (+)-methyl nonactate,22 kumausallene,23 and kumausyne.24 Herein, we report a hybrid of Type I and Type II strategies that involves a Mead reductive cyclization of keto-β-lactones prepared by the tandem Mukaiyama aldol-lactonization (TMAL) process.

β-Lactones continue to gain prominence as versatile intermediates in synthesis,25 to be found as integral components in bioactive natural products,26 and to demonstrate utility as enzyme inhibitors with therapeutic potential.27 We previously reported stereoselective routes to both cis28 and trans29 β-lactones via tandem Mukaiyama aldol-lactonization (TMAL) processes employing substrate control (Scheme 1).28,29 This methodology was applied to total syntheses of (−)-panclicin D,27a tetrahydrolipstatin/orlistat, 27b okinonellin B, 27c and brefeldin A.27d Mead previously demonstrated the utility of simple keto-β-lactones 8 for the synthesis of THFs 9 by a Lewis acid mediated, reductive cyclization process (Scheme 2).30 Building on these precedents, we envisioned a highly diastereoselective synthesis of substituted tetrahydrofurans by combining the TMAL process and Mead reductive cyclization of substituted keto-β-lactones (Scheme 3).

SCHEME 1.

Tandem Mukaiyama Aldol-Lactonization (TMAL) Process

SCHEME 2.

Mead Reductive Cyclization to Tetrahydrofurans

SCHEME 3.

Three-step Strategy Toward Tetrahydrofurans

Results and Discussion

Synthesis of Keto-β-Lactones 12a–f via the Tandem Mukaiyama Aldol Lactonization

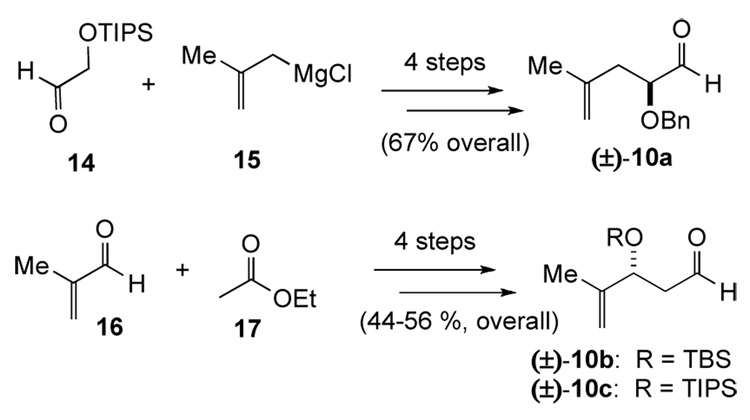

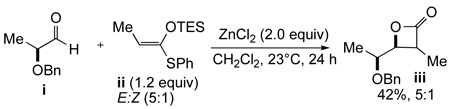

The required aldehydes (±)-10a–c, possessing both α- and β-oxygenation, were prepared in racemic fashion by standard procedures (Scheme 4).31 Application of the TMAL process to α-benzyloxy aldehyde (±)-10a employing propionate ketene acetal 6a proceeded with high diastereoselectivity to give β-lactone 11a based on chelation control (Table 1, entry 1). However, acetate ketene acetal 6b gave low diastereoselectivity as expected with only a slight preference for the Felkin-Ahn derived β-lactone anti-11b (Table 1, entry 2). It is worth noting that both of these TMAL reactions proceeded in comparable yield and diastereoselectivity at 0°C under slightly prolonged reaction times. The sterically demanding, oxygenated ketene acetal 6c delivered moderate yield of anti-11c after prolonged reaction times and proceeded with moderate diastereoselectivity (Table 1, entry 3). In the case of β-silyloxy aldehydes (±)-10b–c, β-lactones 11d–f were obtained with moderate diastereoselectivity and the stereochemical outcome is consistent with Evans’ model32 and our previous studies27 (Table 1, entries 4 and 6). Once again, acetate ketene acetal 6b gave low diastereoselectivity as expected (Table 1, entry 5). Our previous studies suggested that use of thiophenyl acetate ketene acetal 18 with α-benzyloxy aldehyde (±)-10a may lead to a reversal of selectivity toward the chelation controlled adduct, which could be attributed to greater possibility for chelation control due to the monodentate thiophenyl ligand.33 Indeed, this reversal was observed for α-unsubstituted-β-lactones 11b, albeit in diminished ratio (Scheme 5).

SCHEME 4.

Synthesis of Aldehydes (±)-10a–c

TABLE 1.

Alkenyl β-Lactones 11a–f via the TMAL Process from Aldehydes (±)-10a–c

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | aldehyde | ketene acetal | alkenyl-β-lactonea | timeb | % yieldc | drd |

| 1 | 10a |  |

|

14 h | 83 | >19:1e |

| 2 | 10a |  |

|

9 h | 80 | 1.5:1e |

| 3 | 10a |  |

|

12 d | 56f | 4:1e |

| 4 | 10b |  |

|

28 h | 59 | 9:1 |

| 5 | 10b |  |

|

20 h | 69f | 2:1 |

| 6 | 10c |  |

|

10 d | 75 | 5:1 |

With the exception of syn-11c, only trans β-lactones were produced and the major diastereomer is displayed.

Entries 1–2 proceeded efficiently at 0 °C with increased reaction times and delivered comparable yield and diastereoselectivity.

Refers to isolated, purified yield (SiO2) of both diastereomers.

Refers to relative stereochemistry and was determined by analysis of crude reaction mixture by 1H NMR (300 MHz).

Diastereomers were separable by flash column chromatography.

This yield includes the subsequent ozonolysis step.

The minor diastereomer is tentatively assigned as a cis-β-lactone arising from chelation control based on coupling constant analysis (see Table 2).

SCHEME 5.

Reversal of Relative Stereochemistry of Alkenyl-β-Lactone 11b via the TMAL Process with Thiophenyl Ketene Acetal 18

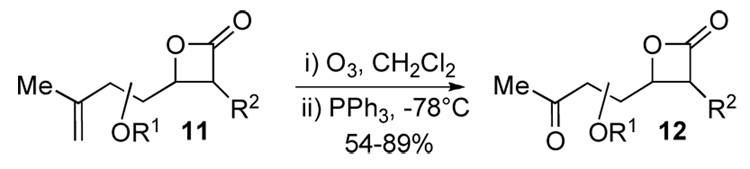

Ozonolysis of alkenyl-β-lactones 11 proceeded smoothly to deliver the required keto-β-lactones 12 for reductive cyclization (Scheme 6). The use of PPh3 to reduce the ozonides proved to be more efficient leading to fewer by-products compared to dimethyl sulfide and therefore simplified purification. Due to some instability noted for keto-β-lactones 12, they were typically rapidly purified and used immediately in subsequent Mead reductive cyclizations.

SCHEME 6.

Synthesis of Keto-β-Lactones 12a–f via Ozonolysis

Stereochemical Assignment of β-Lactones 11–12

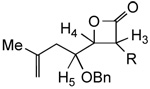

With the exception of β-lactones 11c, bearing a bulky TBDPS group, stereochemical assignment of β-lactones 11a–f obtained via the TMAL process corresponded to previous reports and were subsequently confirmed by nOe analysis of the corresponding THFs 13a–f (vide infra).31 However, the γ-benzyloxy-β-lactones 11a–c and 12a–c displayed a significant trend in coupling constants that may be a predictive tool for assignment of relative (i.e. syn vs. anti) stereochemistry of these systems (Table 2). It is well established that the internal stereochemistry (i.e. cis vs. trans) of β-lactones can be assigned based on coupling constant analysis and this is observed for β-lactones 11–12 (cis: J3,4 = 5.7–6.0 Hz; trans: J3,4 = 3.3–4.5 Hz).34 However, to the best of our knowledge, the determination of relative stereochemistry of these systems has not previously been based solely on coupling constant analysis. In the case of γ-benzyloxy-β-lactones 11a–c and 12a–c, the coupling constants for syn (J4,5 = 4.5–6.0 Hz) and anti (J4,5 = 2.7–3.6 Hz) diastereomers followed a clear trend that is also consistent with our previous studies.27 This is likely due to the conformational rigidity of these systems resulting from torsional strain.35 Although subsequent nOe data for the direct stereochemical assignment of THF 13c was inconclusive, a tentative assignment of the precursor β-lactones anti-11c and anti-12c based on this diagnostic coupling constant trend is plausible.

TABLE 2.

Stereochemical Assignment of γ-benzyloxy-β-lactones 11a–c and 12a–c

| entry |  |

J4,5 (Hz)a | entry |  |

J4,5 (Hz)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

6.0 | 7 |  |

5.1 |

| 2 |  |

3.0 | 8 |  |

NAc |

| 3 |  |

2.7 | 9 |  |

3.3 |

| 4 |  |

5.1 | 10 |  |

4.5 |

| 5 |  |

3.0 | 11 |  |

3.6 |

| 6 |  |

5.7 | 12 |  |

6.0 |

Determined by analysis of chromatographically pure β-lactones by 1H NMR (300 MHz).

Minor diastereomers were carried directly to ozonolysis step and thus not fully characterized.

Not available.

This keto-β-lactone was not prepared.

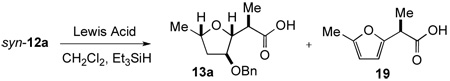

Optimization of Mead Reductive Cyclization

Initial studies of the reductive cyclization of keto-β-lactone syn-12a employing conditions reported by Mead with TiCl4 or BF3•OEt2 as Lewis acid led to the desired THF 13a along with significant quantities of an unexpected by-product, furan 19 (Table 3, entries 1–2). Mead found that silyl triflates also promoted cyclization of keto β-lactones to THFs.36 When triethylsilyl triflate (TESOTf) was added dropwise at −78 °C and then warmed quickly to 0 °C, the ratio of THF to furan did not improve significantly, but this provided the desired THF 13a as the major product (Table 3, entry 3). After extensive experimentation, we found that when TESOTf was added down the side of the flask at −78 °C ("pre-cooled") as a dilute solution in CH2Cl2 and the reaction was allowed to warm to 0 °C slowly over 6 h, this provided the desired THF 13a in 62% yield with only 6% of furan 19 (Table 3, entry 4). Further improvements resulted when a large excess of Et3SiH (20.0 equiv) was employed and THF 13a was isolated in 67% yield as a single diastereomer with only trace amounts of furan 19 (Table 3, entry 5). Finally, a control experiment revealed that furan 19 was the only product formed in the absence of Et3SiH (Table 3, entry 6). Indeed, furan by-products have been observed previously during reductions of 5-membered oxocarbenium ions.37

TABLE 3.

Optimization of the Reductive Cyclization of Keto-β-Lactone syn-12a

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | Lewis Acid | conc. (M)a | methodb | Et3SiH (equiv) | ratio THF 13a/furan 19c | % yieldd |

| 1 | TiCl4 | 0.05 | A | 1.2 | 1/5 | ND |

| 2 | BF3•OEt2 | 0.05 | B | 1.2 | 1/1 | ND |

| 3 | TESOTf | 0.05 | B | 1.2 | 2/1 | 60 |

| 4 | TESOTf | 0.01 | C | 1.2 | 10/1 | 68 |

| 5 | TESOTf | 0.01 | C | 20.0 | 68/1 | 67 |

| 6 | TESOTf | 0.01 | C | 0 | 0/1 | 28 (98)e |

Refers to the final concentration of keto-β-lactone in CH2Cl2.

1.2 equiv of Lewis acid was added to a solution of keto-β-lactone and Et3SiH in CH2Cl2 at −78 °C. Method A: TiCl4 in CH2Cl2 (1.0 M) was added down the side of the flask and stirred for 4 h at −78 °C. Method B: Neat Lewis acid was added dropwise at −78 °C, quickly warmed to 0 °C, and stirred for 4 h. Method C: Lewis acid in CH2Cl2 (0.03 M) was added down the side of the flask and allowed to warm to 0 °C over 6 h.

Ratio determined by crude 1H NMR (500 MHz).

Refers to isolated yield of inseparable mixture of THF and furan.

Significant loss of the furan occurred during purification leading to diminished yields. However, estimated yield based on crude weight and 1H NMR analysis indicated nearly quantitative conversion.

Scope of Mead Reductive Cyclization

Using the optimized conditions, various γ-benzyloxy-keto-β-lactones 12 were converted to THFs 13 with efficient transfer of stereochemistry and only trace quantities of furan were observed (Table 4, entries 1–2). It is interesting to note that a possible stereoreinforcing effect is operative with anti- and syn-β-lactones 12b (dr, 14:1 vs 19:1, respectively) which may be due to a developing 1,3-diaxial interaction of the oxocarbenium intermediate (cf. 24, Scheme 7) leading to greater selectivity for “inside attack.” In the case of keto-β-lactone 12c, TESOTf delivered a complex mixture of products, while BF3•OEt2 provided a cleaner, albeit slower reaction to provide THF 13c (Table 4, entry 3). In the case of δ-silyloxy-keto-β-lactones 12d–f, there was less concern of furan formation based on our proposed mechanism (vide infra). Thus, the strong Lewis acid TiCl4 previously utilized by Mead promoted the reductive cyclization in moderate to good yields with excellent levels of stereochemical transfer using only 1.2 equivalents of Et3SiH (Table 4, entries 4–6). The relative stereochemistry of all ring stereocenters of THFs 13a–f was confirmed by nOe analysis observed for multiple protons of the THF rings,31 which also confirmed invertive ring cleavage during cyclization. The relative stereochemistry between the α-stereocenter and the THF rings is premised on stereochemical invertive cyclization of the trans-substituted (vs. cis) β-lactones, which in turn is based on coupling constants. An exception was THF 13c for which nOe data were inconclusive and thus relative stereochemistry was tentatively assigned based on coupling constants (cf. Table 2). Thus, the stereochemical outcome in each case is consistent with stereochemical invertive alkyl C-O ring cleavage by the pendant ketone followed by reduction of the oxocarbenium to the tetrahydrofuran as predicted by the Woerpel model.38

TABLE 4.

Mead Reductive Cyclization of Keto-β-Lactones 12 Toward Tetrahydrofurans 13a–f

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | keto-β-lactone | Lewis Acid | tetrahydrofuran | % yielda | drb | |

| 1 | anti-12b (>19:1) | TESOTfc |  |

82 | 14:1 | |

| 2 | syn-12b (>19:1) | TESOTfc |  |

78 | >19:1 | |

| 3 | anti-12c (18:1) | BF3•OEt2d |  |

51(35)f | 18:1 | |

| 4 | 12d (9:1) | TiCl4e |  |

84 | 9:1 | |

| 5 | 12e (2:1) | TiCl4e |  |

68 | 2:1 | |

| 6 | 12f (5:1) | TiCl4e |  |

55 | 5:1 | |

Isolated yields of the mixture of diastereomers.

Determined by analysis of crude reaction mixtures by 1H NMR (500 MHz).

TESOTf in CH2Cl2 (0.03 M solution) was added to a solution of keto-β-lactone and Et3SiH (20 equiv) in CH2Cl2 at −78 °C and allowed to warm to 0 °C over 5 h.

BF3•OEt2 in CH2Cl2 (0.03 M solution) was added to a solution of keto-β-lactone and Et3SiH (20 equiv) in CH2Cl2 at −78 °C and allowed to warm to 0 °C over 5 h. This reaction was then stirred for 3 d at 0–10 °C.

TiCl4 in CH2Cl2 (1.0 M) was added to a solution of keto-β-lactone and Et3SiH (20 equiv) in CH2Cl2 for 4 h at −78 °C.

Yield in parentheses refers to recovered keto-β-lactone 12c.

SCHEME 7.

Model for Diastereoselectivity in Reductive Cyclization with γ-Benzyloxy-β-Lactones Based on Woerpel’s Model and a Proposed Mechanism for Formation of Furan 21

Mechanistic Rationale for Mead Reductive Cyclization

Regarding the mechanism of this process for benzyloxy-substituted systems, the reductive cyclization leading to THF 20 and furan 21 is presented as an example (Scheme 7). Ketone cleavage of a silyl activated β-lactone intermediate 22 via alkyl C-O scission in an SN2 fashion delivers the oxocarbenium 23 in line with previous proposals by Mead.30 The stereoelectronically favored envelope conformation 24 places the benzyloxy substituent in the pseudoaxial orientation as proposed by Woerpel and reduction occurs via “inside attack” of Et3SiH.38 Alternatively, a competing pathway leading to furan 21 could involve elimination leading to enol ether 25 which then undergoes acid-mediated elimination of benzyl alcohol to provide oxocarbenium 26. This is followed by rapid aromatization to furan 21 by loss of a second proton, which may occur upon reaction work-up.

In the case of δ-silyloxy-keto-β-lactones 12d–f, based on Woerpel’s findings with related benzyloxy systems which provided diastereomeric ratios of 5–6:1, we expected only moderate selectivity for the reduction of oxocarbeniums 28 (Scheme 8).38b However, we found that the diastereoselectivity of the reduction was >19:1 since the diastereomeric ratio of the THFs 13d–f matched well with the diastereomeric ratio of the substrate β-lactones 12d–f, respectively. There appear to be several factors governing this increase in selectivity. Woerpel has shown that hydrogen atoms prefer to reside in the pseudoaxial position adjacent to an oxocarbenium in both five and six-membered rings for favorable hyperconjugation between the C-H bond and the 2p orbital of the oxocarbenium.38b,39 Less studied by Woerpel were the effects of α-silyloxy oxocarbeniums and both steric and electronic effects could influence the stereochemical outcome. The decreased electron density of the oxygen due to the silyloxy moiety40 leads to lower electron donation compared to a benzyloxy substituent. Thus, compared to the hydrogen atom, the pseudequatorial orientation of the silyloxy substituent is preferred to a greater extent. Steric considerations would also dictate that the more bulky silyloxy group reside in the pseudoequatorial position to a greater degree than a benzyloxy substituent. Additionally, developing gauche interactions between the C5 methyl and the pseudoequatorial silyloxy substituent also favors “inside attack” of Et3SiH (cf. 28, Scheme 8). These effects combine with the preferred “inside attack” leading to high diastereoselectivity for α-silyloxy substituted-oxocarbenium ions.

SCHEME 8.

Model for Diastereoselectivity in Reductive Cyclization with δ-Silyloxy-β-lactones based on Woerpel’s Model.

In summary, we developed a three-step strategy for the diastereoselective synthesis of THFs from alkenyl aldehydes proceeding through β-lactone intermediates. The strategy involves the TMAL process and Mead’s reductive cyclization of keto-β-lactones. The stereoselectivity of the latter process is rationalized by Woerpel’s model for “inside attack” of oxocarbeniums. An increase in selectivity for certain α-silyloxy oxocarbenium ions was observed and is rationalized based on stereoelectronic effects building on Woerpel's findings. The stereoselectivity of the TMAL process for α-benzyloxy and β-silyloxy aldehydes with several thiopyridyl ketene acetals was defined including a reversal in selectivity when a thiophenyl ketene acetal was employed. A correlation between relative stereochemistry and coupling constants was observed that provides a predictive method for the stereochemical assignment of γ-benzyloxy-β-lactones. This strategy should prove useful for the synthesis of tetrahydrofurans found in natural products and the results of these studies will be reported in due course.

Experimental Section

Representative procedure for the TMAL reaction as described for γ-benzyloxy-alkenyl-β-lactone syn-11a

ZnCl2 (273 mg, 2.00 mmol) was freshly fused at ~0.5 mm Hg and subsequently cooled to ambient temperature. Ketene acetal 6a (384 mg, 1.20 mmol) and then aldehyde (±)-10a (204 mg, 1.00 mmol) were each added as a solution in 5 mL of CH2Cl2 (final concentration of aldehyde in CH2Cl2 ~0.1 M). This suspension was stirred for 14 h at 23 °C then quenched with pH 7 buffer, stirred vigorously for 30 min, and poured over Celite with additional CH2Cl2. After concentration under reduced pressure, the residue was redissolved in CH2Cl2 (final concentration of β-lactone in CH2Cl2 ~0.15 M) and treated with CuBr2 (357 mg, 1.60 mmol). After stirring for 2.5 h, the crude β-lactone syn-11a was again poured over Celite and washed with ether (200 mL). The combined organic layers were washed with 10% aq. K2CO3 (3 × 50 mL), H2O (2 × 50 mL), and brine (2 × 50 mL), dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure to deliver crude β-lactone syn-11a as a single diastereomer (>19:1) as judged by analysis of crude 1H NMR (300 MHz). Purification by flash column chromatography (hexanes:ethyl acetate 95:5) delivered pure syn-11a (216 mg, 83%) as a colorless oil: Rf = 0.42 (80:20 hexanes:ethyl acetate); IR (thin film) 3071, 3031, 1827, 1119 cm−1; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.38 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H), 1.78 (dd, J = 0.9, 1.2 Hz, 3H), 2.25 (ddd, J = 0.9, 6.3, 14.1 Hz, 1H), 2.40 (ddd, J = 1.2, 6.9, 14.1 Hz, 1H), 3.43 (dq, J = 4.2, 7.5 Hz, 1H), 3.74 (ddd, J = 6.0, 6.3, 6.9 Hz, 1H), 4.22 (dd, J = 4.2, 6.0 Hz, 1H), 4.66 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 1H), 4.70 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 1H), 4.83–4.86 (m, 1H), 4.88–4.91 (m, 1H), 7.29–7.37 (m, 5H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 12.2, 22.7, 38.7, 47.5, 72.5, 76.8, 80.5, 114.2, 127.78, 127.82(2), 128.4(2), 137.9, 140.9, 171.5; ESI-HRMS Calcd for C16H20O3Li [M + Li] 267.1572, found 267.1591.

Representative procedure for Mead reductive cyclization of γ-benzyloxy-keto-β-lactones as described for THF 13a (Procedure A)

To a solution of γ-benzyloxy-keto-β-lactone syn-12a (262 mg, 1.00 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (50 mL) was added Et3SiH (3.2 mL, 20.0 mmol) slowly at −78 °C followed by TESOTf (274 µL, 1.20 mmol in 40 mL CH2Cl2) down the side of the flask at −78 °C over 10 min to ensure cooling. Upon addition of 10 mL of CH2Cl2 to rinse down any remaining TESOTf, the solution was allowed to warm to 0 °C slowly over 5 h, quenched with pH 4 buffer (50 mL), and warmed to 23 °C with vigorous stirring. The layers were separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 50 mL). The combined organic extracts were dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure to deliver crude THF 13a as a single diastereomer (>19:1) with only trace amounts of furan 19 (68:1) as judged by analysis of crude 1H NMR (500 MHz). Gradient flash column chromatography (hexanes:ethyl acetate 80:20 to 60:40) delivered THF 13a (178 mg, 67%) as a colorless oil. A center fraction from the column was used for characterization: Rf = 0.46 (60:40 hexanes:ethyl acetate); IR (thin film) 3500-2300, 1708, 1091 cm−1; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.23 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H), 1.29 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 3H), 1.54 (ddd, J = 6.5, 10.5, 13.5 Hz, 1H), 2.11 (ddd, J = 1.0, 5.0, 13.5 Hz, 1H), 2.68 (dq, J = 6.0, 7.0 Hz, 1H), 4.01 (ddd, J = 1.0, 3.0, 6.5 Hz, 1H), 4.12 (dd, J = 3.0, 6.0 Hz, 1H), 4.21–4.28 (m, 1H), 4.49 (d, J = 11.5 Hz, 1H), 4.52 (d, J = 11.5 Hz, 1H), 7.27–7.37 (m, 5H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 12.8, 20.5, 40.1, 42.8, 71.4, 75.3, 81.9, 85.4, 127.88(2), 127.95, 128.6(2), 138.1, 178.7; ESI-HRMS calcd for C15H19O4 [M - H] 263.1283, found 263.1271.

Representative procedure for Mead reductive cyclization of γ-benzyloxy-keto-β-lactones as described for THF 13c (Procedure B)

To a solution of γ-benzyloxy-keto-β-lactone 12c (199 mg, 0.40 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (20 mL) was added Et3SiH (1.3 mL, 8.00 mmol) slowly at −78 °C followed by BF3•OEt2 (61 µL, 0.48 mmol in 16 mL CH2Cl2) down the side of the flask at −78 °C over 10 min to ensure cooling. Upon addition of 10 mL of CH2Cl2 to rinse down any remaining BF3•OEt2, the solution was allowed to warm to 0 °C slowly over 5 h, and then stirred at 0–10 °C for 3 d. The reaction was quenched with pH 4 buffer (50 mL), and warmed to 23 °C with vigorous stirring. The layers were separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 50 mL). The combined organic extracts were dried over MgSO4, filtered, concentrated under reduced pressure to deliver crude THF 13c as a mixture of diastereomers (~18:1, ~50% conversion) as judged by analysis of crude 1H NMR (500 MHz). Gradient flash column chromatography (hexanes:ethyl acetate 90:10 to 60:40) delivered recovered 12c (70 mg, 35%, dr 18:1) as a pale yellow oil and THF 13c (102 mg, 51%, dr 18:1) as a pale yellow oil. A center fraction of THF 13c from the column was used for characterization. Characterization data for the major (anti) diastereomer 13c: Rf = 0.30 (70:30 hexanes:ethyl acetate); IR (thin film) 3437-2404, 1731, 1108 cm−1; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.12 (s, 9H), 1.27 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 3H), 1.48 (ddd, J = 6.5, 11.0, 13.5 Hz, 1H), 2.03 (dd, J = 5.0, 13.5 Hz, 1H), 4.07 (dd, J = 2.5, 6.5 Hz, 1H), 4.16 (dd, J = 2.5, 4.5 Hz, 1H), 4.18–4.24 (m, 1H), 4.32 (s, 2H), 4.43 (d, J = 4.5 Hz, 1H), 7.23–7.70 (m, 15H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 19.7, 20.0, 27.2(3), 40.3, 71.5, 72.8, 75.8, 81.0, 86.1, 127.8(2), 127.9, 128.00(2), 128.04(2), 128.6(2), 130.36, 130.40, 132.3, 132.8, 136.0(2), 136.2(2), 138.1, 173.0; ESI-HRMS calcd for C30H35O5Si [M - H] 503.2254, found 503.2241.

Representative procedure for Mead reductive cyclization of δ-silyloxy-keto-β-lactones as described for THF 13d (Procedure C)

To a solution of δ-silyloxy-keto-β-lactone 12d (202 mg, 0.71 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (15 mL) was added Et3SiH (137 µL, 0.85 mmol) dropwise at −78 °C followed by TiCl4 (846 µL, 1.0 M in CH2Cl2) down the side of the flask at −78 °C over 5 min to ensure cooling. Upon addition of 5 mL of CH2Cl2 to rinse down any remaining TiCl4, the solution was stirred at −78 °C for 3 h, quenched with pH 7 buffer (50 mL), and warmed to 23 °C with vigorous stirring. The layers were separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 50 mL). The combined organic extracts were dried over MgSO4, filtered, concentrated under reduced pressure to deliver crude THF 13d as a mixture of diastereomers (9:1) as judged by analysis of crude 1H NMR (500 MHz). Gradient flash column chromatography (hexanes:ethyl acetate 90:10 to 60:40) delivered THF 13d (170 mg, 84%, dr 9:1) as a pale yellow oil: Characterization data for the major (syn) diastereomer 13d: Rf 0.49 (hexanes:ethyl acetate 60:40); IR (thin film) 3475-2460, 1707, 1250 cm−1; 1H NMR (500 MHz, C6D6) δ −0.04 (s, 6H), 0.90 (s, 9H), 1.07 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 3H), 1.14 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H), 1.74 (ddd, J = 6.5, 8.5, 13.0 Hz, 1H), 1.78 (ddd, J = 3.5, 6.5, 13.0 Hz, 1H), 2.47 (dq, J = 7.0, 7.0 Hz, 1H), 3.67 (ddd, J = 3.5, 4.0, 6.5 Hz, 1H), 3.79 (dq, J = 4.0, 6.5 1H), 4.24 (ddd, J = 3.5, 7.0, 8.5 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, C6D6) δ −4.8, −4.6, 13.3, 18.1, 19.1, 25.9(3), 39.0, 45.0, 78.3, 78.7, 82.5, 180.6; ESI-HRMS calcd for C14H27O4Si [M - H] 287.1679, found 287.1611.

Supplementary Material

Experimental details and characterization data (including 1H and 13C NMR spectra) for aldehydes (±)-10a–c and their precursors, alkenyl-β-lactones 11a–b, 11d, and 11f, keto-β-lactones 12a–f, tetrahydrofurans 13a–f (with nOe data), and furan 19. A comparison of key coupling constants for THFs 13a–c. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgment

We thank the NIH (GM-069784) and the Welch Foundation (A-1280) for generous support of this work. We thank Dr. Ziad Moussa (TAMU) for helpful discussions and Dr. Shane Tichy of the Laboratory for Biological Mass Spectrometry supported by the Office of the Vice President for Research (TAMU) for acquiring mass spectral data and helpful discussions.

References

- 1.For reviews on the synthesis of THFs, seeKang JE, Lee E. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:4348. doi: 10.1021/cr040629a.Norcross R, Paterson I. Chem. Rev. 1995;95:2041.Harmange J-C, Figadere B. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1993;4:1711.Boivin T. Tetrahedron. 1987;43:3309.

- 2.(a) Buchanan JG, Dunn AD, Edgar AR. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin. 1974;1:1943. [Google Scholar]; (b) Buchanan JG, Dunn AD, Edgar AR. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin. 1975;1:1191. doi: 10.1039/p19750001191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rychnovsky SD, Bartlett PA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981;103:3963. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chamberlin previously reported a similar route to THFs as Mead, but utilizing epoxides instead of β-lactonesMulholland RL, Chamberlin AR. J. Org. Chem. 1988;53:1082.Fotsh CH, Chamberlin AR. J. Org. Chem. 1991;56:4141.

- 5.Ogawa T, Pernet AG, Hanessian S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1973;37:3543. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michael P, Ting PC, Bartlett PA. J. Org. Chem. 1985;50:2416. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mantell SJ, Ford PS, Watkin DJ, Fleet GWJ, Brown D. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:4503. [Google Scholar]

- 8.For initial disclosure, seeHopkins MH, Overman LE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987;109:4748.For a Perspective, seePennington LD, Overman LE. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:7143. doi: 10.1021/jo034982c.

- 9.(a) Brown MJ, Harrison T, Overman LE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:5378. [Google Scholar]; (b) Grese TA, Hutchinson KD, Overman LE. J. Org. Chem. 1993;58:2468. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanaki N, Link JT, MacMillan DWC, Overman LE, Trankle WG, Wurster JA. Org. Lett. 2000;2:223. doi: 10.1021/ol991315q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corminboeuf O, Overman LE, Pennington LD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:6650. doi: 10.1021/ja035445c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Roush WR, Pinchuk AN, Micalizio GC. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:9413. [Google Scholar]; (b) Micalizio GC, Roush WR. Org. Lett. 2000;2:461. doi: 10.1021/ol9913082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Panek JS, Yang M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:9868. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Micalizio GC, Roush WR. Org. Lett. 2001;3:1949. doi: 10.1021/ol0160250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shotwell JB, Roush WR. Org. Lett. 2004;6:3865. doi: 10.1021/ol048381z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tinsley JM, Roush WR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:10818. doi: 10.1021/ja051986l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tinsley JM, Mertz E, Chong PY, Rarig R-AF, Roush WR. Org. Lett. 2005;7:4245. doi: 10.1021/ol051719k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lambert WT, Roush WR. Org. Lett. 2005;7:5501. doi: 10.1021/ol052321r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoye TR, Wang J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:6950. doi: 10.1021/ja051749i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee E, Tae JS, Lee C, Park CM. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:4831. [Google Scholar]

- 21.(a) Lee E, Jeong EJ, Kang EJ, Sung LT, Hong SK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:10131. doi: 10.1021/ja016272z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jeong EJ, Kang EJ, Sung LT, Hong SK, Lee E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:14655. doi: 10.1021/ja0279646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee E, Choi SJ. Org. Lett. 1999;1:1127. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee E, Yoo S-K, Choo H, Song HY. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:317. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee E, Yoo S-K, Cho Y-S, Cheon H-S, Chong YH. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:7757. [Google Scholar]

- 25.(a) Pommier A, Pons J-M. Synthesis. 1995:729. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wang Y, Tennyson RL, Romo D. Heterocycles. 2004;64:605. [Google Scholar]; For selected recent examples, seeDonohoe TJ, Sintim HO, Sisangia L, Harling JD. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:2293. doi: 10.1002/anie.200453843.Getzle YDYL, Kundnani V, Lobkovsky EB, Coates GW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:6842. doi: 10.1021/ja048946m.Calter MA, Tretyak OA, Flaschenriem C. Org. Lett. 2005;7:1809. doi: 10.1021/ol050411q.Mitchell TA, Romo D. Heterocycles. 2005;66:627.Shen X, Wasmuth AS, Zhao J, Zhu C, Nelson SG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:7438. doi: 10.1021/ja061938g.Henry-Riyad H, Lee C, Purohit VC, Romo D. Org. Lett. 2006;8:4363. doi: 10.1021/ol061816t.Reddy LR, Corey E. J. Org. Lett. 2006;8:1717. doi: 10.1021/ol060464n.

- 26.Lowe C, Vederas JC. Org. Prep. Proced. Int. 1995;27:305. [Google Scholar]

- 27.(a) Yang HW, Zhao C, Romo D. Tetrahedron. 1997;53:16471. [Google Scholar]; (b) Ma G, Zancanella M, Oyola Y, Richardson RD, Smith JW, Romo D. Org. Lett. 2006;8:4497. doi: 10.1021/ol061651o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Schmitz WD, Messerschmidt B, Romo D. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:2058. [Google Scholar]; (d) Wang Y, Romo D. Org. Lett. 2002;4:3231. doi: 10.1021/ol026438g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Y, Zhao C, Romo D. Org. Lett. 1999;1:1197. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang HW, Romo D. J. Org. Chem. 1997;62:4. doi: 10.1021/jo9619488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mead KT, Pillai SK. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:6997. [Google Scholar]

- 31.See Supporting Information for details

- 32.Evans DA, Dart MJ, Duffy JL, Yang MG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:4322. [Google Scholar]

-

33. Zhao C. Ph. D. Thesis. Texas A&M University; 1999.

- 34.Abraham RJ. J. Chem. Soc. B. 1968:173. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Analysis of molecular models for these γ-benzyloxy-β-lactones suggests that there should be a conformational preference due to unfavorable gauche interactions and cancellation of dipoles

- 36.White D, Zemribo R, Mead KT. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:2223. [Google Scholar]

- 37.In the course of the total synthesis of (−)-azaspiracid, a similar by-product was observedEvans DA, Kvaerno L, Mulder JA, Raymer B, Dunn TB, Beauchemin A, Olhava E, Juhl M, Kagechika K. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:4693. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701515.Similar furans were obtained from the corresponding dihydrofuransKatagiri N, Tabei N, Atsuumi S, Haneda T, Kato T. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1985;33:102.

- 38.Larsen CH, Ridgway BH, Shaw JT, Woerpel KA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:12208. doi: 10.1021/ja0524043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Larsen CH, Ridgway BH, Shaw JT, Smith DM, Woerpel KA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:10879. doi: 10.1021/ja0524043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ayala L, Lucero CG, Romero JAC, Tabacco SA, Woerpel KA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:15521. doi: 10.1021/ja037935a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.(a) Keck GE, Boden EP. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984;25:265. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kahn SD, Keck GE, Henre W. J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987;28:279. [Google Scholar]; (c) Keck GE, Castellino S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987;28:281. [Google Scholar]; (d) Shambayati S, Blake J, Wierschke SG, Jorgensen WL, Schreiber SL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:697. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Experimental details and characterization data (including 1H and 13C NMR spectra) for aldehydes (±)-10a–c and their precursors, alkenyl-β-lactones 11a–b, 11d, and 11f, keto-β-lactones 12a–f, tetrahydrofurans 13a–f (with nOe data), and furan 19. A comparison of key coupling constants for THFs 13a–c. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.