Abstract

The synthetic triterpenoid methyl 2-cyano-3,12-dioxoolean-1,9-dien-28-oate (CDDO-Me) is in Phase I clinical trials as a novel cancer therapeutic agent. We previously demonstrated that CDDO-Me induces c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK)-dependent death receptor 5 (DR5) expression and augments death receptor-induced apoptosis. The current study focused on addressing how CDDO-Me induces JNK-dependent DR5 expression. Analysis of DR5 promoter regions defines that the CHOP binding site is responsible for CDDO-Me-induced transactivation of the DR5 gene. Consistently, CDDO-Me induced DR5 expression and parallel CHOP upregulation. Blockade of CHOP upregulation also abrogated CDDO-Me-induced DR5 expression. These results indicate that CDDO-Me induces CHOP-dependent DR5 upregulation. Moreover, the JNK inhibitor SP600125 abrogated CHOP induction by CDDO-Me, suggesting a JNK-dependent CHOP upregulation by CDDO-Me as well. Importantly, knockdown of CHOP attenuated CDDO-Me-induced apoptosis, demonstrating that CHOP induction is involved in CDDO-Me-induced apoptosis. Additionally, CDDO-Me increased the levels of Bip, phosphorylated eIF2α, IRE1α, and ATF4, all of which are featured changes during endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress. Furthermore, salubrinal, an inhibitor of ER stress-induced apoptosis, inhibited JNK activation and upregulation of CHOP and DR5 by CDDO-Me and protected cells from CDDO-Me-induced apoptosis. Thus, ER stress appears to be important for CDDO-Me-induced JNK activation, CHOP and DR5 upregulation, and apoptosis. Collectively, we conclude that CDDO-Me triggers ER stress, leading to JNK-dependent, CHOP-mediated DR5 upregulation and apoptosis.

Keywords: CDDO-Me, ER stress, CHOP, death receptor 5, JNK, apoptosis

Introduction

The novel synthetic triterpenoid methyl-2-cyano-3, 12-dioxooleana-1, 9-dien-28-oate (CDDO-Me) potently induces apoptosis of cancer cells and exhibits antitumor activity in animal models (1–6). Thus, CDDO-Me holds promise as a cancer therapeutic agent and is currently being tested in phase I clinical trials. It is well known that apoptosis can occur through two major apoptotic pathways: the intrinsic mitochondria-mediated pathway and the extrinsic death receptor-induced pathway. These two pathways are linked by the truncated proapoptotic protein Bid (7). Our previous studies have demonstrated that CDDO-Me depletes intracellular gluthione, activates c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and finally leads to upregulation of death receptor 5 (DR5), which contributes to CDDO-Me-mediated activation of the extrinsic apoptotic pathway and augmentation of tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)-induced apoptosis (8, 9). However, the detailed molecular mechanism by which CDDO-Me induces DR5 expression is unknown.

It is known that DR5 expression can be regulated at the transcriptional level through both p53-dependent (10, 11) and -independent mechanisms (12–15). Our previous study suggested that CDDO-Me induces DR5 expression independent of p53 status (8). Thus, we are particularly interested in p53-independent mechanisms. It has been documented that the C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP), also known as growth arrest and DNA damage gene 153 (GADD153), directly regulates DR5 expression through a CHOP binding site in the 5-flanking region of the DR5 gene (16, 17). Thus, certain drugs induce DR5 expression through CHOP-dependent transactivation of the DR5 gene (16–20).

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is the primary organelle for proper protein folding and assembling as well as calcium storage. The accumulation of unfolded protein in the ER lumen leads to the ER stress response known as unfold protein response (UPR). This response ensures coordinate regulation of gene expression at various levels including transcription, translation, and protein degradation to shut down general protein synthesis and to induce the expression of genes including those encoding resident ER proteins with chaperone and folding functions for restoring proper protein folding and ER homeostasis. In addition, this response also activates specific apoptotic pathways to eliminate severely damaged cells, in which the protein folding defects cannot be resolved (21–23).

Inositol requiring kinase 1 (IRE1), double stranded RNA-activated protein kinase-like ER kinase (PERK) and activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) are three critical transmembrane ER signaling proteins that regulate the UPR through their respective signaling cascades. Under resting condition, the chaperone protein Bip binds to the luminal domains of IRE1, PERK, and ATF6, preventing their activation. However, accumulation of unfolded proteins will release Bip, allowing aggregation of these transmembrane signaling proteins, and launching the UPR (21, 23). Although ER stress-induced apoptotic signaling pathways have not been fully uncovered, several mechanisms have been suggested. These include transcriptional induction of CHOP through multiple signaling pathways including PERK/eIF2α-dependent mechanisms, IRE1-mediated JNK activation and cleavage and activation of ER-specific caspase-12 (22–24).

Given that CDDO-Me induces a JNK-dependent DR5 upregulation (8, 9), the current study focused on addressing whether CHOP is involved in JNK-dependent DR5 induction by CDDO-Me and if it does, whether CDDO-Me also induces ER stress. Using human non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells as a model system, we have, for the first time, demonstrated that CDDO-Me indeed induces ER stress and CHOP expression, which participates in JNK-dependent DR5 expression by CDDO-Me.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

CDDO-Me, which was described previously (25) and provided by Dr. M. B. Sporn (Dartmouth Medical School, Hanover, NH), was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at a concentration of 10 mM, and aliquots were stored at −80°C. Stock solution was diluted to the desired final concentrations with growth medium just before use. The specific JNK inhibitor SP600125 was purchased from Biomol (Plymouth Meeting, PA). The ER stress inhibitor salubrinal was purchased from EMD Chemicals, Inc. (San Diego, CA). Rabbit polyclonal anti-DR5 antibody was purchased from ProSci Inc (Poway, CA). Mouse monoclonal anti-CHOP (B-3) and rabbit polyclonal ATF4 (CREB-2; C-20) antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, (Santa Cruz, CA). Mouse monoclonal anti-caspase-3 was purchased from Imgenex (San Diego, CA). Rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho-c-Jun (Ser63), anti-c-Jun, anti-IRE1α, anti-phospho-elF2α (Ser51), anti-caspase-8, anti-caspase-9, and anti-PARP antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Beverly, MA). Mouse monoclonal anti-Bip/GPR78 antibody was purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). Rabbit polyclonal anti-β-actin antibody and N-acetylcysteine (NAC) were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO).

Cell Lines and Cell Culture

The human NSCLC cell lines used in this study were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). These cell lines were cultured in RPMI 1640 containing 5% fetal bovine serum at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air.

Western Blot Analysis

Whole-cell protein lysates were prepared and analyzed by Western blotting as described previously (26, 27).

Cell Survival Assay

Cells were seeded in 96-well cell culture plates and treated the next day with the agents indicated. The viable cell number was estimated using the sulforhodamine B (SRB) assay, as previously described (28).

Detection of Apoptosis

Apoptosis was evaluated by Annexin V staining using the Annexin V-PE apoptosis detection kit purchased from BD Biosciences following the manufacturer’s instructions or by measuring sub-G1 populations using flow cytometry as described previously (29). We also detected caspase activation by Western blotting (as described above) as an additional indicator of apoptosis.

Detection of Cell Surface DR5

The procedure for direct antibody staining and subsequent flow cytometric analysis of cell surface proteins was described previously (19). The mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) that represents antigenic density on a per cell basis was used to represent TRAIL receptor expression level. Phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated mouse anti-human DR5 (DJR2-4) and PE mouse IgG1 isotype control (MOPC-21/P3) were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA).

Gene Silencing using small interfering siRNAs (siRNA)

Silencing of CHOP was achieved by transfecting CHOP siRNA using RNAifect transfection reagent (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Control (i.e., non-silencing) and CHOP siRNAs were described previously (19). Gene silencing effect was evaluated by Western blot analysis as described above after indicated time of treatment.

Construction of DR5 Reporter Plasmids, Transient Transfection, and Luciferase Activity Assay

The reporter constructs containing a 552 bp 5’-flanking region of the DR5 gene with wild-type, mutated CHOP binding site, NF-κB binding site or Elk binding sites were generously provided by Dr. H-G. Wang (University of South Florida College of Medicine, Tampa, FL) (16). The pGL3-DR5(−1400), pGL3-DR5(−810), pGL3-DR5(−420), pGL3-DR5(−373), pGL3-DR5(−240), and pGL3-DR5(−140) reporter constructs were described previously (19, 30). The plasmid transfection and luciferase assay were the same as described previously (19).

Results

CDDO-Me Activates DR5 Transcription in a CHOP-dependent Manner

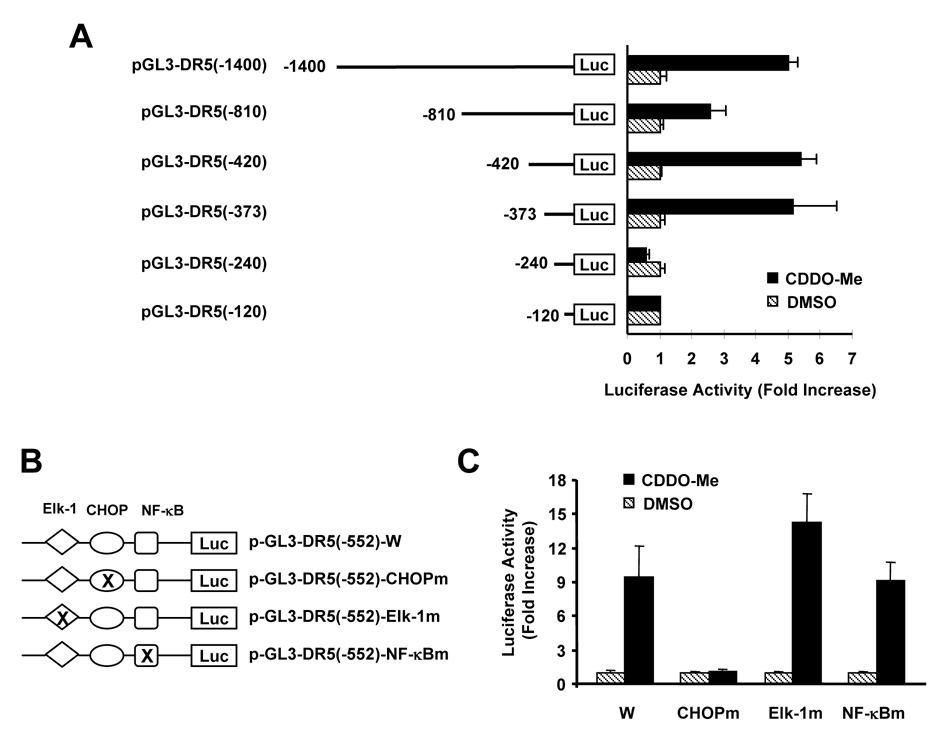

We previously reported that CDDO-Me increases DR5 transcription (8). To determine how CDDO-Me increases DR5 transcription, we began our study by examining the effects of CDDO-Me on the transactivation of reporter constructs with different lengths of DR5 5’-flanking regions (Fig. 1A) to identify the region responsible for CDDO-Me-mediated DR5 transactivation. In this transient transfection and luciferase assay, CDDO-Me did not increase the luciferase activity of pGL3-DR5(−240) and pGL3-DR5(−120), while significantly increasing the luciferase activity of pGL3-DR5(−373), pGL3-DR5(−420), and pGL3-DR5(−1040) (Fig. 1A), indicating that the region between −240 and −373 has essential element(s) responsible for CDDO-Me-induced DR5 transactivation. Since a CHOP binding site is located in this region, we further compared the effects of CDDO-Me on the transactivation of reporter constructs carrying wild-type and mutated CHOP binding sites, respectively. As controls, we also included constructs carrying mutated NF-κB and Elk binding sites, respectively (Fig. 1B). As presented in Fig. 1C, CDDO-Me increased the lucifease activity of the constructs carrying the wild-type DR5 promoter region, or the DR5 promoter region with mutated NF-κB or Elk binding sites. However, CDDO-Me failed to increase the luciferase activity of the construct carrying the DR5 promoter region with a mutated CHOP binding site. These results clearly indicate that the CHOP binding site in the DR5 promoter region is responsible for CDDO-Me-induced DR5 transactivation.

Fig. 1. CDDO-Me induces CHOP-dependent transcription of the DR5 gene.

A) Identification of the region in the DR5 5’-flanking region that is responsible for CDDO-Me-induced DR5 transactivation. The given reporter constructs with different lengths of the 5’-flanking region of the DR5 gene were co-transfected with pCH110 plasmid into H1792 cells. After 24 h, the cells were treated with DMSO or 1 µM CDDO-Me for 12 h and then subjected to luciferase assay. Each column represents a mean ± SD of triplicate determinations. B and C) The CHOP binding site is required for CDDO-Me-induced DR5 transactivation. The given reporter constructs with and without different mutated binding sites (B) were co-transfected with pCH110 plasmids into H1792 cells. After 24 h, the cells were treated with DMSO or 1 µM CDDO-Me for 12 h and then subjected to luciferase assay (C). Each column represents a mean ± SD of triplicate determinations.

CDDO-Me Increases CHOP Expression Leading to DR5 Upregulation

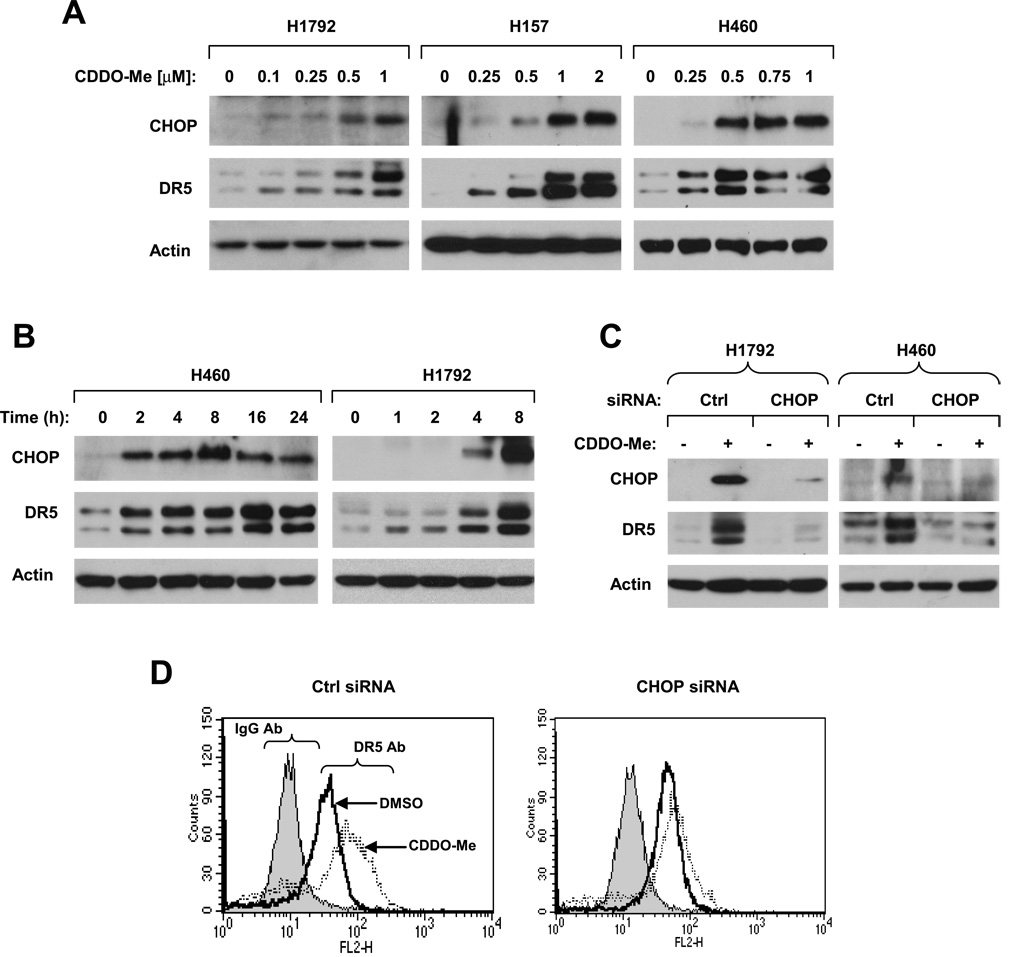

We next determined whether CDDO-Me actually induces CHOP expression. By Western blot analysis, we detected a concentration- and time-dependent CHOP induction accompanied by DR5 upregulation in cells exposed to CDDO-Me (Figs. 2A and 2B). To test whether CHOP induction is involved in mediating CDDO-Me-induced DR5 upregulation, we silenced CHOP expression via siRNA transfection to block CDDO-Me-induced CHOP expression. As presented in Fig. 2C, we detected CHOP induction in cells transfected with the control siRNA, but not or only minimally in CHOP siRNA-transfected cells after exposing to CDDO-Me, indicating a successful silencing of CHOP expression. Accordingly, we detected DR5 upregulation only in control siRNA-transfected cells when treated with CDDO-Me. In agreement, CDDO-Me increased cell surface DR5 levels in control siRNA transfected cells, but only minimally in CHOP siRNA-transfected cells (Fig. 2D). Thus, these data clearly indicate that CDDO-Me-induced DR5 upregulation is secondary to CHOP induction.

Fig. 2. CDDO-Me induces CHOP-dependent DR5 expression.

A) CDDO-Me induces dose-dependent DR5 expression. The indicated cells lines were treated with the indicated concentrations of CDDO-Me for 12 h. B) CDDO-Me induces time-dependent DR5 expression. H460 and H1792 cells were treated with 1 µM CDDO-Me for the times as indicated. C) Blockade of CHOP induction abrogates CDDO-Me-induced DR5 upregulation. Both H1792 and H460 cells lines were transfected with control (Ctrl) or CHOP siRNA. After 48 h, the cells were treated with 1 µM CDDO-Me for 12 h (H1792) or with 0.5 µM CDDO-Me for 8 h (H460). After the aforementioned treatments (A–C), the cells were subjected to preparation of whole-cell protein lysates and subsequent Western blot analysis. D) Blockade of CHOP induction inhibits CDDO-Me-induced increase in cell surface DR5. H1792 cells were transfected with control (Ctrl) or CHOP siRNA. After 48 h, the cells were treated with 1 µM CDDO-Me for 12 h and then subjected to staining of cell surface DR5 and subsequent flow cytometry. Ab, antibody.

We detected two bands for DR5 protein in the blots (Fig. 2). It is noteworthy that the two-band pattern of DR5 protein is consistent with the previously published results on DR5 protein (8, 27, 30)(31)(32). Their specificities were also confirmed by using DR5 siRNA (8, 19, 27) previously and in the current study (Fig. 2). The two bands of DR5 protein may correspond to the products of two isoforms of DR5 gene as described previously (33).

CDDO-Me-induced CHOP Expression is JNK Dependent

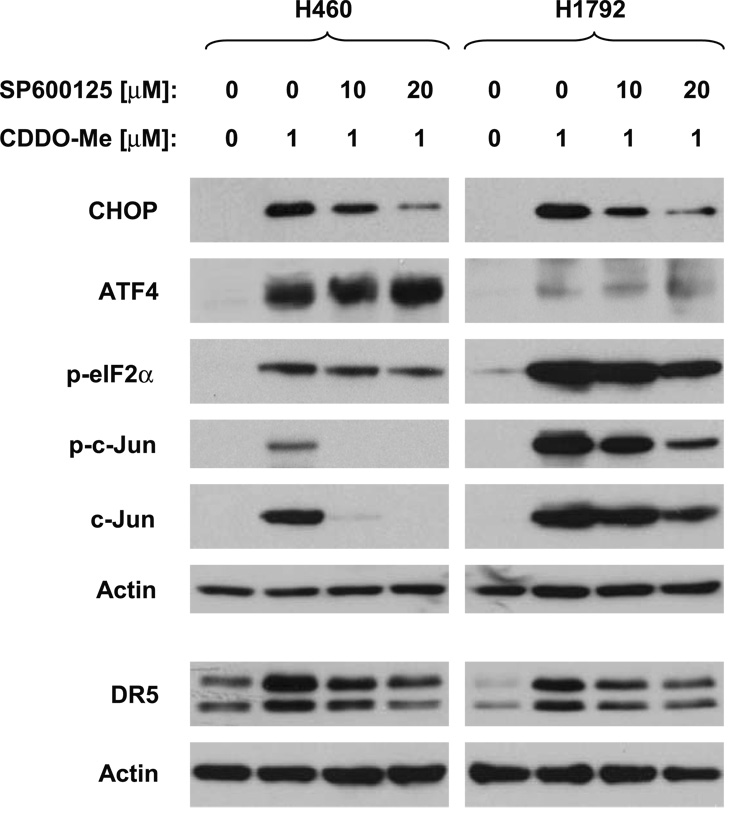

We previously showed that CDDO-Me induces JNK-dependent DR5 upregulation (8). Given that CHOP is also regulated by JNK activation (34), we then examined whether CHOP induction by CDDO-Me involves JNK activation. To this end, we treated cells with CDDO-Me in the absence and presence of the JNK inhibitor SP600125 and then analyzed CHOP and DR5 expression. In agreement with our previous finding (8), the presence of SP600125 abrogated CDDO-Me’s ability to increase p-c-Jun levels and DR5 expression. Concurrently, CDDO-Me-induced CHOP expression was also inhibited by SP600125 (Fig. 3). Thus these results suggest that CDDO-Me induces CHOP-dependent DR5 upregulation involving JNK activation.

Fig. 3. Blockade of JNK activation prevents CDDO-Me-induced upregulation of CHOP and DR5 but not increases in ER stress marker proteins.

The indicated cell lines were pretreated with 10 or 20 µM SP600125 for 30 min and then co-treated with 1 µM CDDO-Me for an additional 6 h. The cells were then harvested and subjected to preparation of whole-cell protein lysates for detection of the indicated proteins by Western blot analysis. SP600125 alone at the tested concentrations did not modulate the levels of CHOP, DR5, ATF4 and p-eIF2α.

CHOP Induction Contributes to CDDO-Me-induced Apoptosis

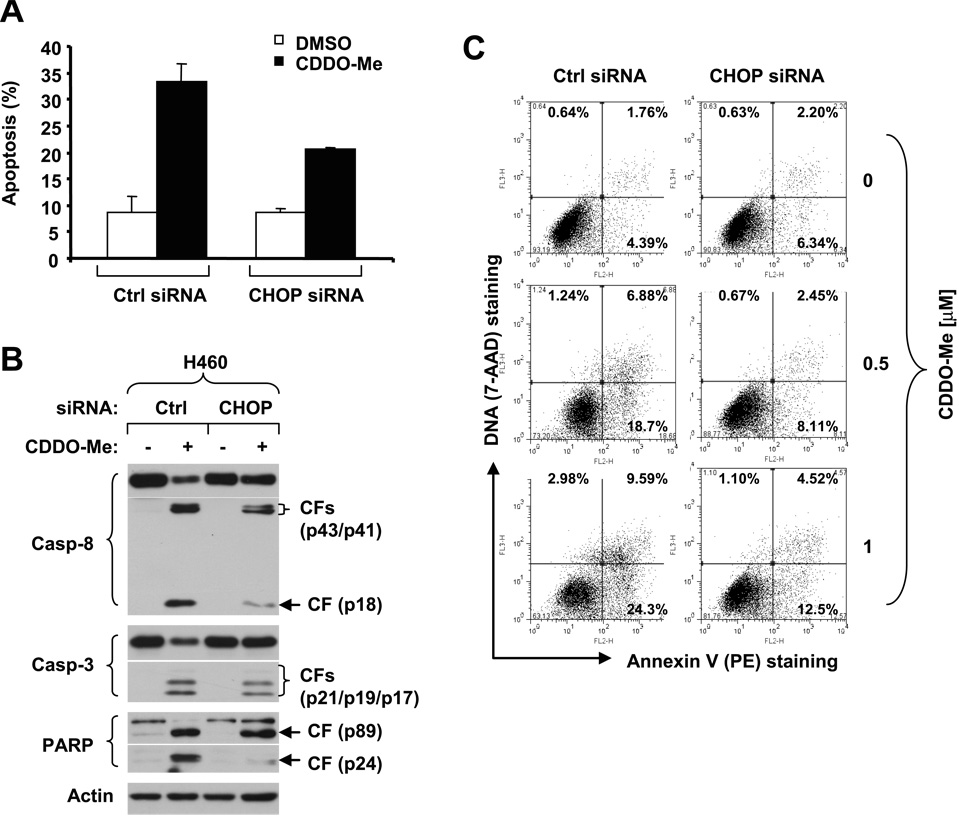

We previously demonstrated that DR5 upregulation contributes to CDDO-Me-induced apoptosis (8). Given that CDDO-Me induces CHOP-dependent DR5 expression, it is plausible to speculate that CHOP induction should also contribute to CDDO-Me-induced apoptosis. Indeed, we found that CDDO-Me induced approximately 35% apoptotic cells in control siRNA-transfected H1792 cells, but only about 20% apoptotic cells in CHOP siRNA-transfected H1792 cells (Fig. 4A). In agreement, we detected striking activation of caspase-8 and caspase-3 in CDDO-Me-treated H460 cells transfected with control siRNA evidenced by decreased levels of pro-forms of caspase-8, caspase-3 and PARP accompanied with appearance of the strong cleaved bands of these proteins. However, we detected only minimal reduction of the pro-forms of these proteins with weaker bands of their cleaved forms in CDDO-Me-treated H460 cells transfected with CHOP siRNA (Fig. 4B). By directly evaluating apoptosis using the annexin V staining, we detected approximately 25% and 34% apoptosis, respectively, in control siRNA-transfected H460 cells but only 11% and 17% apoptosis, respectively, in the CHOP siRNA-transfected cells when exposed to 0.5 and 1 µM CDDO-Me (Fig. 4C). These results collectively indicate that blockade of CHOP induction attenuates CDDO-Me-induced apoptosis. Thus, we conclude that CHOP induction contributes to CDDO-Me-induced apoptosis.

Fig. 4. Blockade of CHOP induction diminishes CDDO-Me’s ability to induce apoptosis.

A) H1792 cells were plated in 6-well cell culture plates and transfected with control (Ctrl) or CHOP siRNA. After 48 h, the cells were treated with the 1 µM CDDO-Me for 12 h and then subjected to flow cytrometric analysis for sub-G1 populations. Columns, means of duplicate assays; Bars, ± SE. B and C) H460 cells were plated in 6-well cell culture plates and transfected with control (Ctrl) or CHOP siRNA. After 48 h, the cells were treated with the 0.5 µM CDDO-Me for 8 h and then subjected to preparation of whole-cell protein lysates and Western blot analysis (B). In addition, the cells were also harvested for annexin V staining and flow cytometric analysis of apoptotic cells (C). The percent positive cells in the upper right and lower right quadrants were added to yield the total of apoptotic cells.

CDDO-Me Induces ER Stress

Given that CHOP is known to be a featured ER stress marker protein involved in ER stress-mediated apoptosis, we further determined whether CDDO-Me induces ER stress. To this end, we detected the levels of several typical ER stress marker proteins, which are usually increased (e.g., Bip, IRE1α, p-eIF2α, and ATF4) during ER stress, in cells exposed to CDDO-Me. As presented in Fig. 5A, CDDO-Me increased the levels of Bip in three NSCLC cell lines (left panel). Moreover, CDDO-Me also elevated the levels of IRE1α, p-eIF2α and ATF4 (right panel). The increase in Bip, IRE1α, p-eIF2α and ATF4 occurred quickly, as early at 1 or 2 h post CDDO-Me treatment. Together, these results suggest that CDDO-Me induces ER stress.

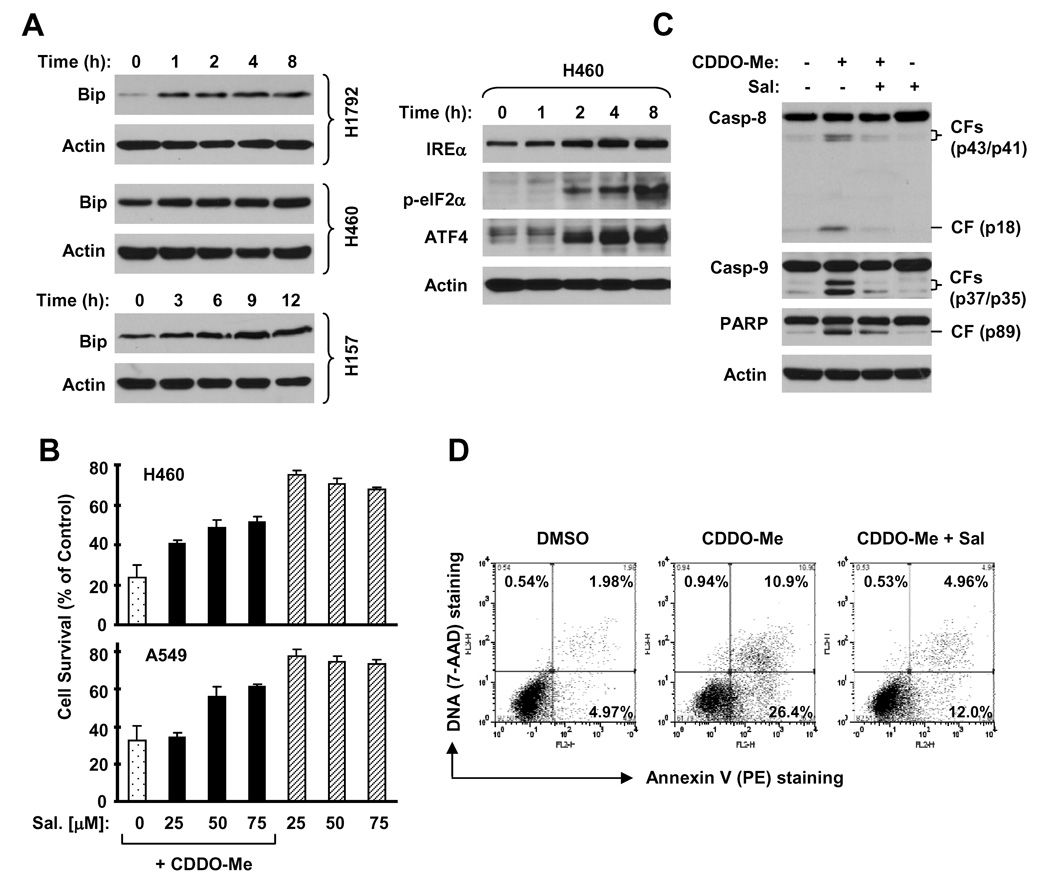

Fig. 5. CDDO-Me increases the levels of ER stress marker proteins (A) and induces ER stress-mediated apoptosis (B–D).

A) The indicated cell lines were treated with 1 µM CDDO-Me. After the indicated times, the cells were harvested and subjected to preparation of whole-cell protein lysates for detection of the indicated proteins by Western blot analysis. B) The indicated cell lines were seeded in 96-well cell culture plates and treated the next day with DMSO, 1 µM CDDO-Me alone, the given concentrations of salubrinal (Sal) alone, and the respective combination of CDDO-Me with each of the given concentrations of salubrinal. After 24 h, the cells were subjected to the SRB assay for estimation of cell numbers. Columns, means of four replicate determinations; Bars, ± SDs; * P < 0.001 compared with CDDO-Me alone by one-way ANOVA analysis using GraphPad InStat 3 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). C and D) H460 cells were seeded in 6-well plates and treated the next day with DMSO, 1 µM CDDO-Me alone, 75 µM salubrinal (Sal) alone, and their combination. After 6 h, the cells were harvested for preparation of whole-cell protein lysates for detection of the indicated proteins by Western blot analysis (C) or for detecting annexin V-positive cells using flow cytometry (D). CFs, cleaved froms.

CDDO-Me-induced ER Stress is Associated with Induction of Apoptosis

To determine the impact of ER stress on CDDO-Me-induced apoptosis, we compared the effects of CDDO-Me on induction of apoptosis in the absence and presence of salubrinal, an inhibitor of ER stress-induced apoptosis. As shown in Fig. 5B, the presence of salubrinal (particularly at 50 and 75 µM) significantly protected lung cancer cells from CDDO-Me-induced cell death. In agreement, CDDO-Me-induced cleavage of caspase-8, caspase-9, and PARP and a increase in Annexin V-positive (i.e., apoptotic) populations were also substantially inhibited by salubrinal (Figs. 5C and 5D). Thus, it appears that ER stress is involved in CDDO-Me-induced apoptosis.

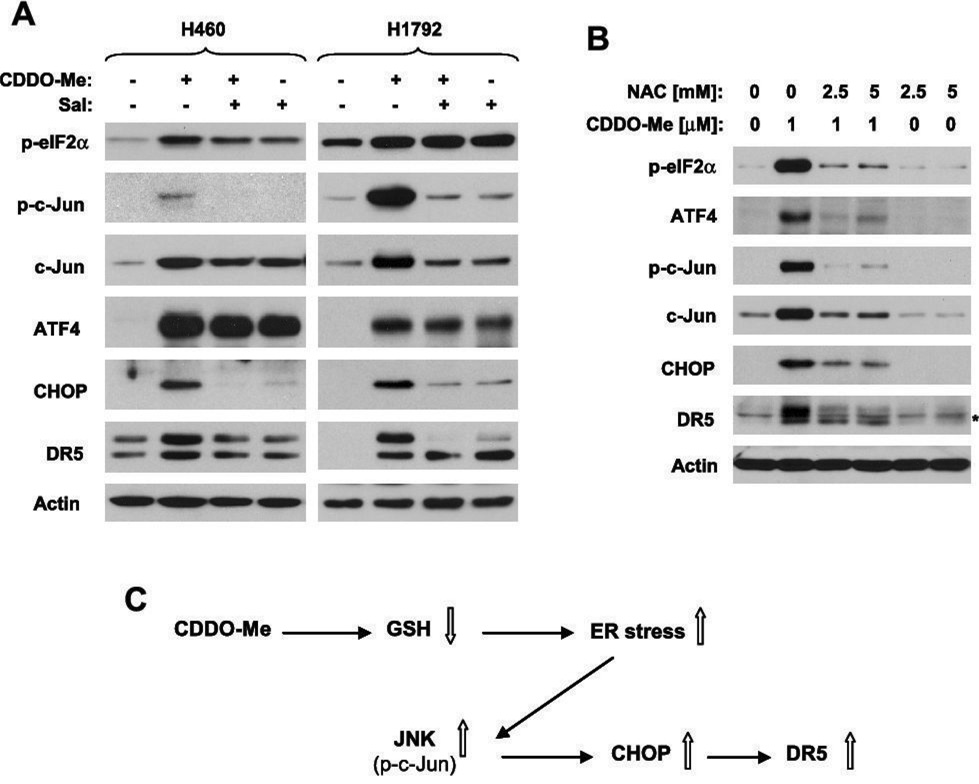

CDDO-Me-induced JNK Activation and Upregulation of CHOP and DR5 is Secondary to ER Stress

To decipher the relationship between ER stress, JNK activation and CHOP-dependent DR5 induction, we compared the effects of CDDO-Me on the levels of p-c-Jun, CHOP and DR5 in the absence and presence of salubrinal. As presented in Fig. 6A, CDDO-Me increased the levels of p-c-Jun, CHOP and DR5 in the absence of salubrinal, but these effects were substantially inhibited in the presence of salubrinal, suggesting that CDDO-Me-initiated increases in the levels of these proteins are all associated with ER stress. Consistently, the JNK inhibitor SP600125 had minimal inhibition on CDDO-Me-induced increase in ATF4 and p-eIF2α while preventing CHOP and DR5 upregulation (Fig. 3), further supporting the notion that the activation of JNK and upregulation of CHOP and DR5 are consequences of ER stress.

Fig. 6. Effects of Salubrinal (A) or NAC (B) on CDDO-Me-induced JNK activation, CHOP and DR5 upregulation and increase in the levels of ER stress marker proteins and a schematic model for CDDO-Me-induced DR5 expression (C).

A and B) Both H460 and H1792 cells (A) or H1792 cells (B) were pretreated with 75 µM salubrinal (Sal) (A) or the indicated concentrations of NAC (B) for 30 min and then co-treated with 1 αM CDDO-Me for an additional 6 h. The cells were then subjected to preparation of whole-cell protein lysates for detection of the indicated proteins by Western blot analysis. The asterisk indicates non-specific bands. C) Schematic model for CDDO-Me-induced DR5 expression. CDDO-Me induces ER stress via depletion of intracellular GSH, leading to JNK activation and subsequent CHOP-dependent DR5 upregulation.

We noted that salubrinal alone strongly increased the levels of p-eIF2α and ATF4, but weakly elevated CHOP levels. When combined with CDDO-Me, salubrinal minimally inhibited the CDDO-Me-induced ATF4 increase while substantially abrogating CDDO-Me-induced CHOP upregulation in both H460 and H1792 cell lines. Similarly, salubrinal did not affect (e.g., H1792) or weakly inhibited (e.g., H460) CDDO-Me-induced elevation of p-eIF2α levels (Fig. 6A).

CDDO-Me Triggers ER Stress through Depletion of Intracellular Glutathione (GSH)

We and others previously demonstrated that GSH depletion plays a critical role in mediating induction of apoptosis including JNK activation and DR5 upregulation by CDDO-Me or its analogs (1, 9, 35, 36). Thus, we further examined the protective effects of NAC, which prevents GSH reduction with an antioxidative property, on CDDO-Me-induced ER stress, JNK activation and upregulation of CHOP and DR5 expression. In agreement with our previous findings (9), NAC attenuated CDDO-Me’s ability to increase p-c-Jun levels and DR5 expression. Besides, CDDO-Me-induced increases in CHOP and ATF4 and phosphorylation of elF2α were all substantially inhibited by NAC (Fig. 6B). Collectively, these results indicate that CDDO-Me induces ER stress through depleting intracellular GSH.

Discussion

Our previous studies have demonstrated that CDDO-Me induces DR5 upregulation, resulting in induction of apoptosis and enhancement of TRAIL-induced apoptosis in human lung cancer cells (8, 9). Moreover, we have shown that CDDO-Me increases DR5 expression at the transcription level (8) secondary to GSH depletion-initiated JNK activation (8, 9). Here we further show that CDDO-Me increases CHOP-dependent transcription of the DR5 gene. It has been well documented that CHOP is an important transcription factor that regulates DR5 expression (16, 17, 19, 20). Through the deletion and mutation analysis of the DR5 5’-flanking region, we revealed that the regions containing the CHOP binding site is essential for CDDO-Me-mediated DR5 transactivation (Fig. 1). Consistently, CDDO-Me induced a time- and dose-dependent CHOP expression, which was accompanied by DR5 upregulation. Moreover, blockage of CDDO-Me-mediated CHOP induction by CHOP siRNA accordingly abrogated CDDO-Me’s ability to upregulate DR5 expression (Fig. 2). Collectively, we conclude that CDDO-Me induces DR5 expression through a CHOP-dependent mechanism.

We previously demonstrated that DR5 induction is involved in CDDO-Me-induced apoptosis (8). In this study, we found that blockade of CDDO-Me-induced CHOP upregulation through siRNA-mediated gene silencing not only abrogated DR5 upregulation by CDDO-Me, but also diminished CDDO-Me’s ability to induce apoptosis (Fig. 4). Thus, we conclude that CHOP induction also participates in CDDO-Me-induced apoptosis. Thus, these findings further highlight the important role of DR5 upregulation in CDDO-Me-induced apoptosis. We noted that blockage of CHOP did not abolish CDDO-Me’s ability to induce apoptosis despite substantially inhibiting DR5 induction (Fig. 2 and Fig. 4). Thus, it is possible that mechanisms other than CHOP/DR5 may also be involved in mediating CDDO-Me-induced apoptosis. It has been documented that NF-κB represses CHOP expression (37), whereas CDDO-Me inhibits NF-κB (38, 39). Thus, future study may investigate whether inhibition of NF-κB is involved in CDDO-Me-induced CHOP/DR5 expression.

It is well known that CHOP is a typical ER stress-regulated protein involved in ER stress-induced apoptosis (24). Thus, our finding on CHOP induction by CDDO-Me suggests that CDDO-Me may trigger ER stress. Indeed, CDDO-Me increased the levels of Bip, IRE1α, p-eIF2α, and ATF4 (Fig. 5), all of which are additional proteins accumulated or increased during ER stress (21, 22). Therefore, it appears that CDDO-Me induces ER stress. Salubrinal is a selective inhibitor of eIF-2α dephosphorylation and ER stress-induced apoptosis (40). The presence of salubrinal apparently protected lung cancer cells from CDDO-Me-induced decrease in cell survival, caspase activation and apoptotic death (Fig. 5). Thus, it appears that CDDO-Me induces apoptosis involving ER stress. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating the involvement of ER stress in CDDO-Me-induced apoptosis.

Both JNK and CHOP are implicated in mediating ER stress-induced apoptosis (23). A recent study suggested that JNK activation during ER stress contributes to CHOP expression (34). We previously demonstrated that CDDO-Me activates JNK leading to DR5 upregulation and apoptosis (8, 9). In the present study, we detected both JNK activation and CHOP induction in cells exposed to CDDO-Me. Moreover, the presence of the JNK inhibitor SP600125 attenuated CDDO-Me-induced CHOP expression in addition to inhibition of DR5 expression, indicating that CDOO-Me-induced CHOP expression is also JNK-dependent. Collectively, we conclude that the JNK activation mediates CHOP-dependent DR5 induction. We noted that SP600125 inhibited CDDO-Me-induced c-Jun phosphorylation completely, but only partially prevented CHOP and DR5 upregulation by CDDO-Me in H460 cells (Fig. 3). Thus, we cannot role out the possibility that other mechanisms also participate in CDDO-Me-induced CHOP-dependent DR5 upregulation.

Although SP600125 inhibited CDDO-Me-induced CHOP and DR5 upregulation, it minimally prevented CDDO-Me-induced increases in p-eIF2α and ATF4 (Fig. 3), suggesting that JNK activation and subsequent upregulation of CHOP and DR5 are secondary to ER stress. This notion was further supported by our findings that salubrinal attenuated CDDO-Me’s ability to increase c-Jun phosphorylation, CHOP induction and DR5 upregulation (Fig. 6A) while inhibiting CDDO-Me induced apoptosis (Fig. 4). Taken together, we conclude that CDDO-Me induces ER stress, leading to JNK activation and subsequent CHOP-dependent DR5 upregulation (Fig. 6C).

It is generally thought that eIF2α/ATF4 signaling pathway is the primary mechanism for the induction of CHOP in ER stress (22, 24). However, other pathways also can regulate CHOP expression in ER stress (22, 24). It has been initially demonstrated that salubrinal protects cells from ER stress-induced apoptosis through increasing p-eIF2α levels by inhibiting eIF2α dephosphorylation. Consequently, CHOP expression is also increased (40). However, salubrinal can also potentiate ER stress and induce apoptosis through such a mechanism involving upregulation of ATF4 and CHOP under certain conditions (41). In our study, salubrinal apparently protects NSCLC cells from CDDO-Me-induced apoptosis as discussed above. Salubrinal itself strongly increased the levels of p-eIF2α and ATF4 while weakly inducing CHOP expression in human NSCLC cells. Interestingly, salubrinal minimally inhibits CDDO-Me-induced elevation of p-eIF2α and ATF4 levels, whereas it strongly abrogated CDDO-Me’s ability to increase p-c-Jun, CHOP expression and DR5 upregulation (Fig. 6A). These results imply that CDDO-Me is unlikely to induce CHOP expression through the p-eIF2α/ATF4-mediated signaling pathway in ER stress. Thus, the mechanism underlying CDDO-Me induced JNK-dependent CHOP upregulation in ER stress needs further investigation.

It has been documented in several studies that depletion of intracellular GSH plays a critical role in initiating apoptosis by CDDO-Me or its analogs (1, 9, 35, 36). This is likely caused by the reversible interaction between CDDO-Me and GSH (42). We previously showed that CDDO-Me depletes intracellular GSH, resulting in JNK-dependent DR5 upregulation and apoptosis in human NSCLC cells (9). In this study, we found that the presence of NAC abrogated CDDO-Me’s effects not only on activating JNK and inducing DR5 expression, but also on increasing the levels of CHOP, ATF4 and p-eIF2α, all of which are typical ER stress marker proteins (Fig. 6B). Thus, it appears that CDDO-Me induces ER stress through depletion of intracellular GSH.

In summary, the present study has demonstrated that CDDO-Me depletes intracellular GSH, resulting in ER stress. Subsequently, it activates JNK, leading to CHOP-dependent DR5 upregulation and apoptosis (Fig. 6C).

Acknowledgement

We are thankful to Dr. M. B. Sporn for CDDO-Me, Dr. H-G. Wang for certain DR5 report constructs and Dr. H. A. Elrod in our lab for editing the manuscript.

Grant Support: Georgia Cancer Coalition Distinguished Cancer Scholar award (to S-Y. S.), Department of Defense VITAL grant W81XWH-04-1-0142 (to S-Y. Sun for Project 4) and NIH/NCI SPORE P50 grant CA128613-01 (to S-Y. Sun for Project 2).

References

- 1.Ikeda T, Sporn M, Honda T, Gribble GW, Kufe D. The novel triterpenoid CDDO and its derivatives induce apoptosis by disruption of intracellular redox balance. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5551–5558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim KB, Lotan R, Yue P, et al. Identification of a novel synthetic triterpenoid, methyl-2-cyano-3,12-dioxooleana-1,9-dien-28-oate, that potently induces caspase-mediated apoptosis in human lung cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2002;1:177–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Konopleva M, Tsao T, Ruvolo P, et al. Novel triterpenoid CDDO-Me is a potent inducer of apoptosis and differentiation in acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 2002;99:326–335. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.1.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liby K, Royce DB, Williams CR, et al. The synthetic triterpenoids CDDO-methyl ester and CDDO-ethyl amide prevent lung cancer induced by vinyl carbamate in A/J mice. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2414–2419. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ling X, Konopleva M, Zeng Z, et al. The novel triterpenoid C-28 methyl ester of 2-cyano-3, 12-dioxoolen-1, 9-dien-28-oic acid inhibits metastatic murine breast tumor growth through inactivation of STAT3 signaling. Cancer Res. 2007;67:4210–4218. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vannini N, Lorusso G, Cammarota R, et al. The synthetic oleanane triterpenoid, CDDO-methyl ester, is a potent antiangiogenic agent. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:3139–3146. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hengartner MO. The biochemistry of apoptosis. Nature. 2000;407:770–776. doi: 10.1038/35037710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zou W, Liu X, Yue P, et al. c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase-mediated up-regulation of death receptor 5 contributes to induction of apoptosis by the novel synthetic triterpenoid methyl-2-cyano-3,12-dioxooleana-1, 9-dien-28-oate in human lung cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7570–7578. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yue P, Zhou Z, Khuri FR, Sun SY. Depletion of intracellular glutathione contributes to JNK-mediated death receptor 5 upregulation and apoptosis induction by the novel synthetic triterpenoid methyl-2-cyano-3, 12-dioxooleana-1, 9-dien-28-oate (CDDO-Me) Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;5:492–497. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.5.2565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu GS, Burns TF, McDonald ER, 3rd, et al. KILLER/DR5 is a DNA damage-inducible p53-regulated death receptor gene. Nat Genet. 1997;17:141–143. doi: 10.1038/ng1097-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takimoto R, El-Deiry WS. Wild-type p53 transactivates the KILLER/DR5 gene through an intronic sequence-specific DNA-binding site. Oncogene. 2000;19:1735–1743. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sheikh MS, Burns TF, Huang Y, et al. p53-dependent and -independent regulation of the death receptor KILLER/DR5 gene expression in response to genotoxic stress and tumor necrosis factor alpha. Cancer Res. 1998;58:1593–1598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ravi R, Bedi GC, Engstrom LW, et al. Regulation of death receptor expression and TRAIL/Apo2L-induced apoptosis by NF-kappaB. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:409–416. doi: 10.1038/35070096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shetty S, Graham BA, Brown JG, et al. Transcription factor NF-kappaB differentially regulates death receptor 5 expression involving histone deacetylase 1. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:5404–5416. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.13.5404-5416.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meng RD, El-Deiry WS. p53-independent upregulation of KILLER/DR5 TRAIL receptor expression by glucocorticoids and interferon-gamma. Exp Cell Res. 2001;262:154–169. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.5073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamaguchi H, Wang HG. CHOP is involved in endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis by enhancing DR5 expression in human carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:45495–45502. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406933200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoshida T, Shiraishi T, Nakata S, et al. Proteasome inhibitor MG132 induces death receptor 20 5 through CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein homologous protein. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5662–5667. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abdelrahim M, Newman K, Vanderlaag K, Samudio I, Safe S. 3,3′-diindolylmethane (DIM) and its derivatives induce apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells through endoplasmic reticulum stress-dependent upregulation of DR5. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:717–728. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun SY, Liu X, Zou W, Yue P, Marcus AI, Khuri FR. The Farnesyltransferase Inhibitor Lonafarnib Induces CCAAT/Enhancer-binding Protein Homologous Protein-dependent Expression of Death Receptor 5, Leading to Induction of Apoptosis in Human Cancer Cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:18800–18809. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611438200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen S, Liu X, Yue P, Schonthal AH, Khuri FR, Sun SY. CHOP-dependent DR5 induction and ubiquitin/proteasome-mediated c-FLIP downregulation contribute to enhancement of TRAIL-induced apoptosis by dimethyl-celecoxib in human non-small cell lung cancer cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72:1269–1279. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.037465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ron D, Walter P. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:519–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Szegezdi E, Logue SE, Gorman AM, Samali A. Mediators of endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:880–885. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malhotra JD, Kaufman RJ. The endoplasmic reticulum and the unfolded protein response. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2007;18:716–731. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oyadomari S, Mori M. Roles of CHOP/GADD153 in endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11:381–389. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Honda T, Rounds BV, Bore L, et al. Novel synthetic oleanane triterpenoids: a series of highly active inhibitors of nitric oxide production in mouse macrophages. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1999;9:3429–3434. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00623-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun SY, Yue P, Wu GS, et al. Mechanisms of apoptosis induced by the synthetic retinoid CD437 in human non-small cell lung carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 1999;18:2357–2365. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu X, Yue P, Zhou Z, Khuri FR, Sun SY. Death receptor regulation and celecoxib-induced apoptosis in human lung cancer cells. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1769–1780. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun SY, Yue P, Dawson MI, et al. Differential effects of synthetic nuclear retinoid receptor-selective retinoids on the growth of human non-small cell lung carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 1997;57:4931–4939. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun SY, Yue P, Shroot B, Hong WK, Lotan R. Induction of apoptosis in human non-small cell lung carcinoma cells by the novel synthetic retinoid CD437. J Cell Physiol. 1997;173:279–284. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199711)173:2<279::AID-JCP36>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin YD, Chen S, Yue P, et al. CHOP-dependent death receptor 5 induction is a major component of SHetA2-induced apoptosis in lung cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5335–5344. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Griffith TS, Rauch CT, Smolak PJ, et al. Functional analysis of TRAIL receptors using monoclonal antibodies. J Immunol. 1999;162:2597–2605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu GS, Burns TF, McDonald ER, 3rd, et al. Induction of the TRAIL receptor KILLER/DR5 in p53-dependent apoptosis but not growth arrest. Oncogene. 1999;18:6411–6418. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Screaton GR, Mongkolsapaya J, Xu XN, Cowper AE, McMichael AJ, Bell JI. TRICK2, a new alternatively spliced receptor that transduces the cytotoxic signal from TRAIL. Curr Biol. 1997;7:693–696. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00297-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li J, Holbrook NJ. Elevated gadd153/chop expression and enhanced c-Jun N-terminal protein kinase activation sensitizes aged cells to ER stress. Exp Gerontol. 2004;39:735–744. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2004.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Samudio I, Konopleva M, Hail N, Jr, et al. 2-Cyano-3,12 dioxooleana-1,9 diene-28-imidazolide (CDDO-Im) directly targets mitochondrial glutathione to induce apoptosis in pancreatic cancer. J Biol Chem. 2005 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507518200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ikeda T, Nakata Y, Kimura F, et al. Induction of redox imbalance and apoptosis in multiple myeloma cells by the novel triterpenoid 2-cyano-3,12-dioxoolean-1,9-dien-28-oic acid. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3:39–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nozaki S, Sledge GW, Jr, Nakshatri H. Repression of GADD153/CHOP by NF-kappaB: a possible cellular defense against endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced cell death. Oncogene. 2001;20:2178–2185. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ahmad R, Raina D, Meyer C, Kharbanda S, Kufe D. Triterpenoid CDDO-Me blocks the NF-kappaB pathway by direct inhibition of IKKbeta on Cys-179. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:35764–35769. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607160200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shishodia S, Sethi G, Konopleva M, Andreeff M, Aggarwal BB. A synthetic triterpenoid, CDDO-Me, inhibits IkappaBalpha kinase and enhances apoptosis induced by TNF and chemotherapeutic agents through down-regulation of expression of nuclear factor kappaB-regulated gene products in human leukemic cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:1828–1838. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boyce M, Bryant KF, Jousse C, et al. A selective inhibitor of eIF2alpha dephosphorylation protects cells from ER stress. Science. 2005;307:935–939. doi: 10.1126/science.1101902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cnop M, Ladriere L, Hekerman P, et al. Selective inhibition of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 alpha dephosphorylation potentiates fatty acid-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress and causes pancreatic beta-cell dysfunction and apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:3989–3997. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607627200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liby KT, Yore MM, Sporn MB. Triterpenoids and rexinoids as multifunctional agents for the prevention and treatment of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:357–369. doi: 10.1038/nrc2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]