Abstract

Phagocytosis of apoptotic cells, also called efferocytosis, is an essential feature of immune responses and critical to resolution of inflammation. Impaired efferocytosis is associated with unfavorable outcome from inflammatory diseases, including acute lung injury and pulmonary manifestations of cystic fibrosis. HMGB1, a nuclear non-histone DNA-binding protein, has recently been found to be secreted by immune cells upon stimulation with LPS and cytokines. Plasma and tissue levels of HMGB1 are elevated for prolonged periods in chronic and acute inflammatory conditions, including sepsis, rheumatoid arthritis, acute lung injury, burns, and hemorrhage. In this study, we found that HMGB1 inhibits phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils by macrophages in vivo and in vitro. Phosphatidylserine (PS) is directly involved in the inhibition of phagocytosis by HMGB1, as blockade of HMGB1 by PS eliminates the effects of HMGB1 on efferocytosis. Confocal and FRET demonstrate that HMGB1 interacts with PS on the neutrophil surface. However, HMGB1 does not inhibit PS-independent phagocytosis of viable neutrophils. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid from Scnn+ mice, a murine model of cystic fibrosis lung disease, which contains elevated concentrations of HMGB1 inhibits neutrophil efferocytosis. Anti-HMGB1 antibodies reverse the inhibitory effect of Scnn+ BAL on efferocytosis, showing that this effect is due to HMGB1. These findings demonstrate that HMGB1 can modulate phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils and suggest an alternative mechanism by which HMGB1 is involved in enhancing inflammatory responses.

Keywords: HMGB1, Phagocytosis, Neutrophils, Cystic fibrosis

Introduction

Phagocytosis of apoptotic cells, also known as efferocytosis, is an essential feature of the immune response. Rapid clearance of apoptotic cells by professional phagocytes is critical in protecting the surrounding tissue from harmful exposure to the inflammatory or immunogenic contents of dying cells (1). In addition, ingestion of apoptotic cells by macrophages results in the release of antiinflammatory mediators, including TGF-β1 and PGE2, and suppresses the production of proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-8 and TNF-α, as well as other proinflammatory mediators, including TXA2, by macrophages (2, 3). Defects in the clearance of dying cells have been shown in patients with acute lung injury (4, 5), cystic fibrosis (6, 7), as well as those with chronic autoimmune diseases (8, 9).

The initial event in efferocytosis is the recognition of an “eat me” signal on the target cell by a broad set of receptors localized on the surface of the phagocyte. Phosphatidylserine (PS) is the best-explored “eat me” signal on apoptotic cells (10). In the early stages of apoptosis, PS redistributes from the inner to the outer membrane leaflet in a process involving inhibition of aminophospholipid translocase and activation of lipid scramblase (10). Interaction of PS with annexin V results in shielding of the PS “eat me” signal and inhibition of apoptotic and necrotic cell uptake by macrophages (11, 12).

High mobility group protein-1 protein (HMGB1), originally described as a nuclear non-histone DNA-binding protein, has more recently been shown to act as an extracellular mediator of inflammation (13, 14). Experiments in mice found that HMGB1 levels in serum are increased at late time points after endotoxin exposure and also that delayed administration of antibodies to HMGB1 attenuates endotoxin lethality (13, 15). However, recent studies have demonstrated that HMGB1 itself has weak proinflammatory activity, and only develops the ability to induce cytokine production from macrophages and other cell populations after binding to DNA or bacterially derived materials (16, 17). Because there is evidence that HMGB1 can bind to PS in vitro (16, 18), we hypothesized that HMGB1 may inhibit recognition of apoptotic cells by phagocytes through covering PS on the apoptotic cell’s surface. Thus, in this study, we not only confirmed that HMGB1 binds to PS on apoptotic neutrophils, but additionally demonstrated that HMGB1 has an inhibitory effect on efferocytosis.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Custom cocktail antibodies and negative selection columns for neutrophil isolation were from StemCell Technologies. Penicillin-streptomycin and Brewer thioglycollate were from Sigma-Aldrich. Annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide were from R&D. Phosphatidylserine, phosphatidylcholine, and NBD-phosphatidylserine were from Avanti Polar Lipids. Rabbit anti-HMGB1 polyclonal antibodies were from Abcam. Mouse anti-CD47 monoclonal antibodies were from BD Biosciences. Chromeo 546 and Chromeo 642 fluorescent labeling kits were from Active Motif. Purified recombinant annexin V was from BD Biosciences.

Purified recombinant human HMGB1 was produced by Kevin Tracey’s laboratory (The Feinstein Institute for Medical Research). The methods of purification and the purity of recombinant HMGB1 protein were described in detail (19). HMGB1 was over 90% pure and LPS content in the HMGB1 protein was less than 3 pg/µg protein

Isolation and induction of apoptosis in neutrophils

All of the animal protocols have been reviewed and approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of University of Alabama at Birmingham. Mouse neutrophils were purified from bone marrow cell suspensions as described previously (20). Briefly, bone marrow cells were incubated with 20 µl of primary antibodies specific to the cell surface markers F4/80, CD4, CD45R, CD5, and TER119 for 15 minutes at 4°C. Anti-biotin tetrameric Ab complexes (100 µl) were then added, and the cells incubated for an 15 minutes at 4°C. Following this, 60 µl of colloidal magnetic dextran iron particles were added and incubated for 15 minutes at 4°C. The entire cell suspension was then placed into a column, surrounded by a magnet. The T cells, B cells, RBC, monocytes, and macrophages were captured in the column, allowing the neutrophils to pass through by negative selection. The cells were then pelleted and washed. Neutrophil purity, as determined by HEMA 3® stained cytospin preparations, was greater than 97%. Cell viability, as determined by trypan blue exclusion, was consistently greater than 98%.

Apoptosis was induced by heating at 42°C for 60 min and followed by incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 3 h. To monitor apoptosis, 106 cells were stained with annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were analyzed without fixation by flow cytometry within 30 min of staining.

Culture of mouse peritoneal macrophages

Peritoneal macrophages were elicited in 8–10-week-old mice by intraperitoneal injection of 1 ml of 3% Brewer thioglycollate. Cells were harvested 5 days later by peritoneal lavage. Cells were plated on 96-well plates at a concentration of 2×105 cells/well. After 2 h at 37°C, non-adherent cells were removed by washing with medium. Fresh medium was added to the cells and changed approximately every 3 days. One hour prior to the phagocytosis assay, the medium was replaced by Opti-MEM medium with 5% mouse serum.

In Vitro Phagocytosis assays

Phagocytosis was assayed by adding 106 pre-incubated apoptotic neutrophils suspended in 100 ul Opti-MEM medium to each well of the 96-well plate containing adherent macrophage monolayers at 37°C for 90 min. For studies investigating inhibition of phagocytosis, apoptotic neutrophils were pre-incubated with HMGB1, lipid vesicles, anti-HMGB1 antibodies, annexin V (supplemented with 2 mM CaCl2), or BAL fluid from WT or Scnn+ mice in Opti-MEM medium at 37°C for 30 min before the phagocytosis assay. Mouse serum was included at a final concentration of 2.5% during the co-incubation, as phagocytosis has been shown to be dependent on serum (21). Neutrophil cultures were then washed three times with ice-cold PBS and trypsinized. The detached cells were collected and cytospin was performed at 500 rpm for 5 min. Cytospin slides were fixed in 100% methanol and stained with HEMA 3®. Phagocytosis was evaluated by counting 200–300 macrophages per slide from triplicate experiments. The phagocytosis index is represented as the percentage of macrophages containing at least one ingested neutrophil.

In vivo efferocytosis assay

10 × 106 apoptotic neutrophils were incubated with 4 µg HMGB1 or mouse albumin in 50 µl PBS for 30 min and then intratracheally injected into isofluorane anesthetized mice. After 90 min, the mice were sacrificed and bronchial-alveolar lavage performed with a total volume of 3 ml PBS. Cytospin slides were prepared using 250 µl of the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. The phagocytosis index was scored as described for the in vitro efferocytosis assays.

Production of lipid vesicles

PS and PC were initially dissolved in chloroform at a concentration of 10 mg/ml. To obtain the vesicles, the lipids were resuspended at 1:1000 in PBS by vigorous vortexing followed by sonication using a bath-type sonicator for 3 repetitions, each for 30 sec. The final lipid concentration was adjusted to 30 ng/ml.

Confocal microscopy and fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) analysis

Following apoptosis induction, NBD-PS and Chromeo546 labeled HMGB1 were added to the apoptotic neutrophils at a final concentration of 1 µg/ml and incubated at 37°C for 3h. The cells were washed and then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min and cytospin slides were prepared.

FRET analysis was performed as previously described (22). Briefly, proximity of cell surface proteins was investigated for FRET measurements by the acceptor photobleaching technique. An excitation wavelength of 450 nm and an emission wavelength of 525–550 nm were used for donor probes (NBD), and an excitation wavelength of 530 nm and an emission wavelength of 570–625 nm were used for the acceptor (Chromeo546). FRET-positive pixels and efficiencies were calculated by directly subtracting images obtained before acceptor photobleaching from images acquired immediately after acceptor photobleaching to reveal the increased fluorescence of the donor. After an initial confocal image was acquired, a portion of a single cell was masked, and the acceptor fluorescence (Chromeo546) in the masked area was bleached with a pumped dye laser to < 30%. The remaining area of the same cell was left un-bleached and used as a control. After pixel alignment between the pre- and post-bleach images was ensured, individual pixel FRET efficiencies were calculated by expressing the increased donor fluorescence as a fraction of the post-bleach intensity. The noise level in unbleached areas was eliminated to identify FRET-positive areas and calculate image statistics.

Statistical analysis

For each experimental condition, the entire group of animals was prepared and studied at the same time. Data are presented as mean ± SD (in vitro experiments) or mean ± SEM (in vivo experiments) for each experimental group. One-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey-Kramer analysis was performed for comparisons among multiple groups and Student’s t test was used for comparisons between two groups. A value of p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Phosphatidylserine is necessary for phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils

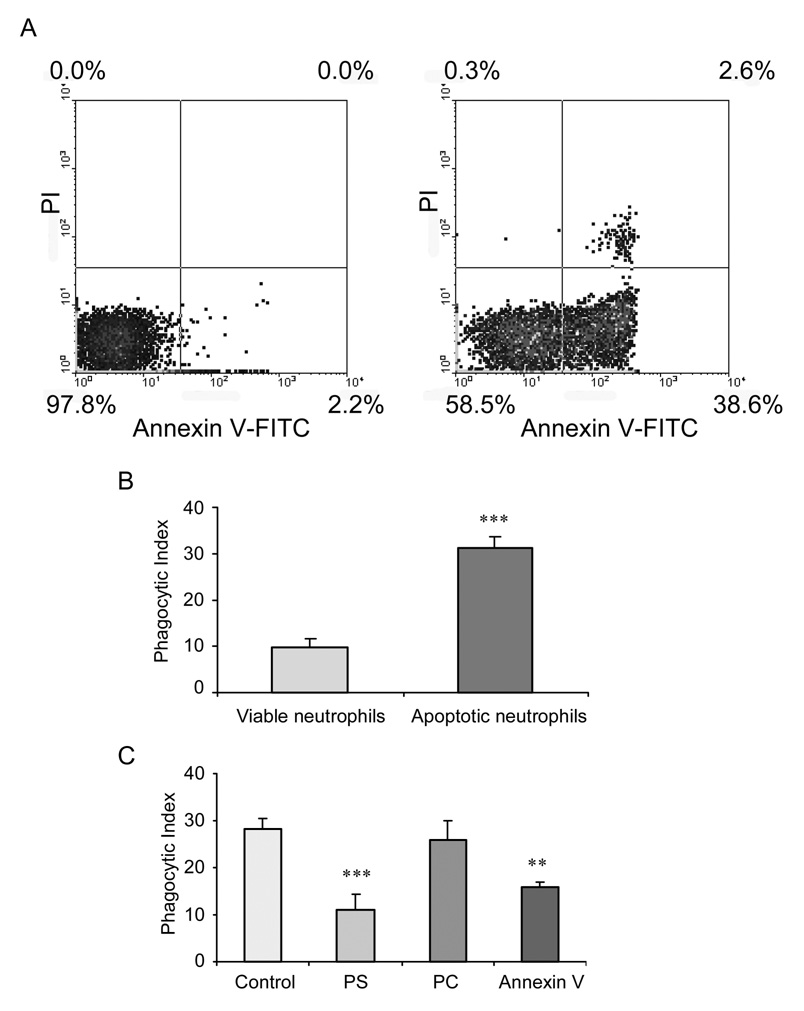

To confirm apoptosis of the neutrophils after heating and incubation at 37°C for 3 hours. the cells were stained with annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide (PI) for flow cytometry. As shown in Figure 1A, after heating for 60 minutes, constantly more than 40% of the neutrophils were apoptotic (i.e., annexin V+). Phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils obtained after 60 minutes heating was approximately 3-fold higher than that found with viable, non-apoptotic neutrophils (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Phosphatidylserine is necessary for phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils.

(A) Induction of neutrophil apoptosis. Bone-marrow derived neutrophils were heated at 42°C for 60 min and then incubated for 3 hours at at 37°C. Apoptosis was analyzed by flow cytometry after annexin V and PI staining. (B) Phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils is significantly increased as compared to that of viable neutrophils. In these experiments, 106 viable or apoptotic neutrophils were added onto peritoneal macrophage monolayers and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. The phagocytosis index was calculated as the percentage of macrophages containing at least one ingested neutrophil. *** p < 0.001 compared to viable neutrophils. (C) PS and Annexin V, but not PC, inhibit phagocytosis of neutrophils. Apoptotic neutrophils were pre-treated with 30 nM phosphatidylserine (PS), 30 nM phosphatidylcholine (PC), or 3 ug/ml annexin V (AV) for 30 min prior to phagocytotic assay. *** p < 0.001 compared to control. ** p < 0.01 compared to control.

Previous studies have demonstrated that PS expressed on the surface of apoptotic lymphocytes is required for phagocytosis by macrophages (23). To test whether the appearance of PS on the surface of apoptotic neutrophils was also associated with the development of the ability to efficiently phagocytose apoptotic cells, phagocytosis assays were performed using apoptotic bone marrow neutrophils and peritoneal macrophages. PS vesicles were used to compete with the PS presented on apoptotic neutrophils (24). The lipid phosphatidylcholine (PC), which is present on both the viable and apoptotic cell surface and is not involved in recognition of apoptotic cells, was used as a negative control for PS. Due to its ability to bind to PS with high affinity, annexin V was also employed to examine the role of neutrophil PS expression on phagocytosis (25). As shown in Figure 1C, both PS vesicles and annexin V, but not PC vesicles, significantly decreased efferocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils. These results indicate that exposed PS on the apoptotic neutrophils serves as a signal for phagocytosis.

HMGB1 inhibits phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils

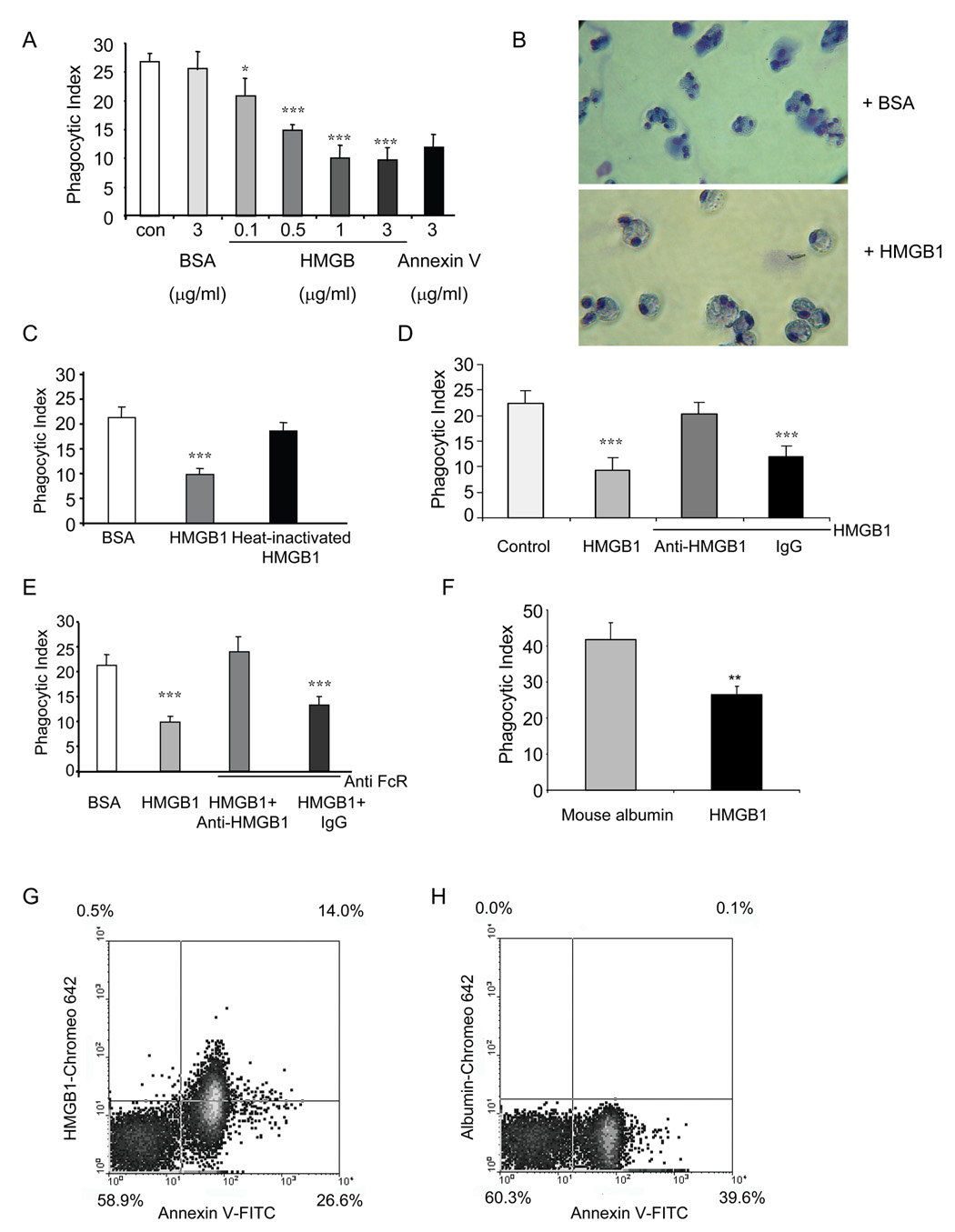

To determine whether extracellular HMGB1 can modulate efferocytosis, apoptotic neutrophils were incubated with HMGB1 for 30 minutes before being exposed to macrophages for phagocytosis assays. As shown in Figure 2A, HMGB1 does-dependently inhibits phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils. with diminished phagocytosis apparent at 0.1 µg/ml HMGB1 and maximal effects present at 1 µg/ml HMGB1. As a positive control, annexin V also was able to inhibit phagocytosis, whereas BSA had no effects. Figure 2B showed representative images of phagocytosis of neutrophils treated with control BSA or HMGB1.

Figure 2. HMGB1 inhibits phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils.

(A) HMGB1 significantly inhibits phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils. Phagocytosis assays were performed in the presence of 0, 0.1, 0.5, 1, and 3 µg/ml recombinant HMGB1. Annexin V or BSA at 3 µg/ml were used as a positive or negative control, respectively. * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001 compared to control with no addition of proteins. (B) Representative images of phagocytosis of neutrophils treated with control BSA or HMGB1. (C) Boiled HMGB1 is unable to inhibit the phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils. HMGB1 protein was not or was boiled for 15 min before being incubated with neutrophils. The phagocytosis assays were performed as in A. *** p < 0.001 as compared to cells incubated with BSA or heat-inactivated HMGB1. (D) Anti-HMGB1 antibodies abolish the inhibition of phagocytosis by HMGB1. Phagocytosis assays were performed in the presence of 1 µg/ml HMGB1 alone or in combination with 1 µg/ml anti-HMGB1 antibodies or rabbit IgG. *** p < 0.001 compared to control. (E) Anti-HMGB1 antibodies efficiently eliminate the inhibitory effect of HMGB1 on phagocytosis after blockade of FcR. Macrophages were pre-treated with 1 µg/ml anti-FcR antibody before the addition of apoptotic neutrophils that had been incubated with either HMGB1 or HMGB1 plus anti-HMGB1 antibodies or IgG . Phagocytosis assays were performed as in D. *** p < 0.001 compared to control BSA treated neutrophils. (F) HMGB1 inhibits phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils by alveolar macrophages in vivo. Apoptotic neutrophils were incubated with 4 µg mouse albumin or recombinant HMGB1 in 50 µl PBS for 30 min and then were intratracheally injected into isofluorane anesthetized mice. BAL fluid was harvested 90 min later and cytospin slides prepared to determine phagocytic indices of mouse alveolar macrophages engulfing apoptotic neutrophils. ** p < 0.01 compared to apoptotic neutrophils treated with mouse albumin. (G–H) Apoptotic neutrophils bind to extracellular HMGB1, but not mouse albumin. Apoptotic neutrophils were incubated with 1 µg/ml Chromeo 642 labeled HMGB1 (G) or Chromeo 642 labeled mouse albumin (H) for 1 h. Cells were then washed with PBS and stained with annexin V-FITC for 15 min. Two-color flow cytometry assay was performed.

To demonstrate that the inhibitory effect of HMGB1 on phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils is not due to contaminants, such as LPS, presented in the purified protein preparation, the HMGB1 protein was boiled for 15 minutes before being incubated with neutrophils. The boiled protein no longer inhibited phagocytosis, indicating that the active form of HMGB1 is required to modulate phagocytosis (Figure 2C).

To determine whether the inhibition of phagocytosis by HMGB1 is a specific effect, we added anti-HMGB1 antibodies to the phagocytosis assays. As shown in Figure 2D, anti-HMGB1 antibodies abolished the inhibitory effects of HMGB1 on engulfment of apoptotic neutrophils by macrophages. In contrast, control rabbit IgG had no effect on HMGB1 associated decreases in efferocytosis (Figure 2D). To rule out the possibility that abrogation of the inhibitory effect of HMGB1 by anti-HMGB1 antibodies is due to anti-body associated secondary stimulation of FcR on the macrophages, macrophages were pre-treated with anti-FcR antibodies before the addition of neutrophils to the cultures. As shown in Figure 2E, even after FcR blockade, anti-HMGB1 antibodies still efficiently eliminated the inhibitory activity of HMGB1 on macrophage phagocytosis of neutrophils.

To demonstrate that HMGB1 inhibits phagocytosis in vivo, apoptotic neutrophils incubated with mouse albumin or recombinant HMGB1 were injected intratracheally into mice and BAL fluid harvested 90 minutes later for determination of alveolar uptake of neutrophils. As shown in Figure 2F, incubation of apoptotic neutrophils to HMGB1, but not mouse albumin, before administration into the lungs resulted in diminished phagocytosis by alveolar macrophages in vivo. To determine if HMGB1 binds to the surface of apoptotic neutrophils, HMGB1 was labeled with Chromeo 642 fluorescent dye and then incubated with the apoptotic neutrophils that subsequently were injected intratracheally. Chromeo 642 labeled HMGB1, but not Chromeo 642 labeled mouse albumin, bound to the apoptotic cell surface (Figure 2G–H).

Phosphatidylserine is involved in the inhibition of phagocytosis by HMGB1

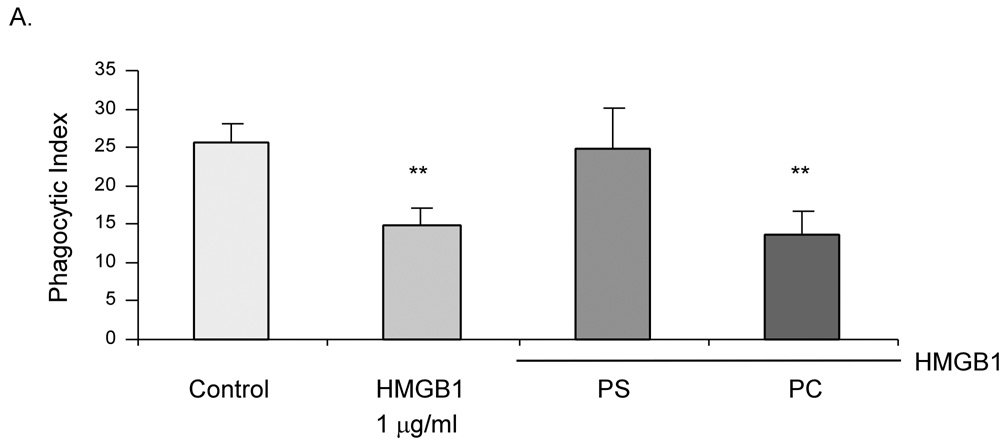

PS exposure on the cell surface is essential for efferocytosis of apoptotic cells (7, 11, 12, 23). Because HMGB1 can bind to PS in vitro (16), we therefore hypothesized that the inhibitory effect of HMGB1 on neutrophil phagocytosis involves PS. Thus, we examined if PS can abolish the inhibitory effect of HMGB1 or vice versa. As shown in Figure 3, preincubation of HMGB1 with PS abrogated the inhibitory activity of either HMGB1 or PS on efferocytosis. In contrast, PC was unable to block the inhibitory effects of HMGB1 neutrophil phagocytosis.

Figure 3. Phosphatidylserine is involved in the inhibition of phagocytosis by HMGB1.

Phagocytosis assays were performed in the presence of HMGB1 alone or in combination with 30 nM PS or PC. ** p < 0.01 compared to control.

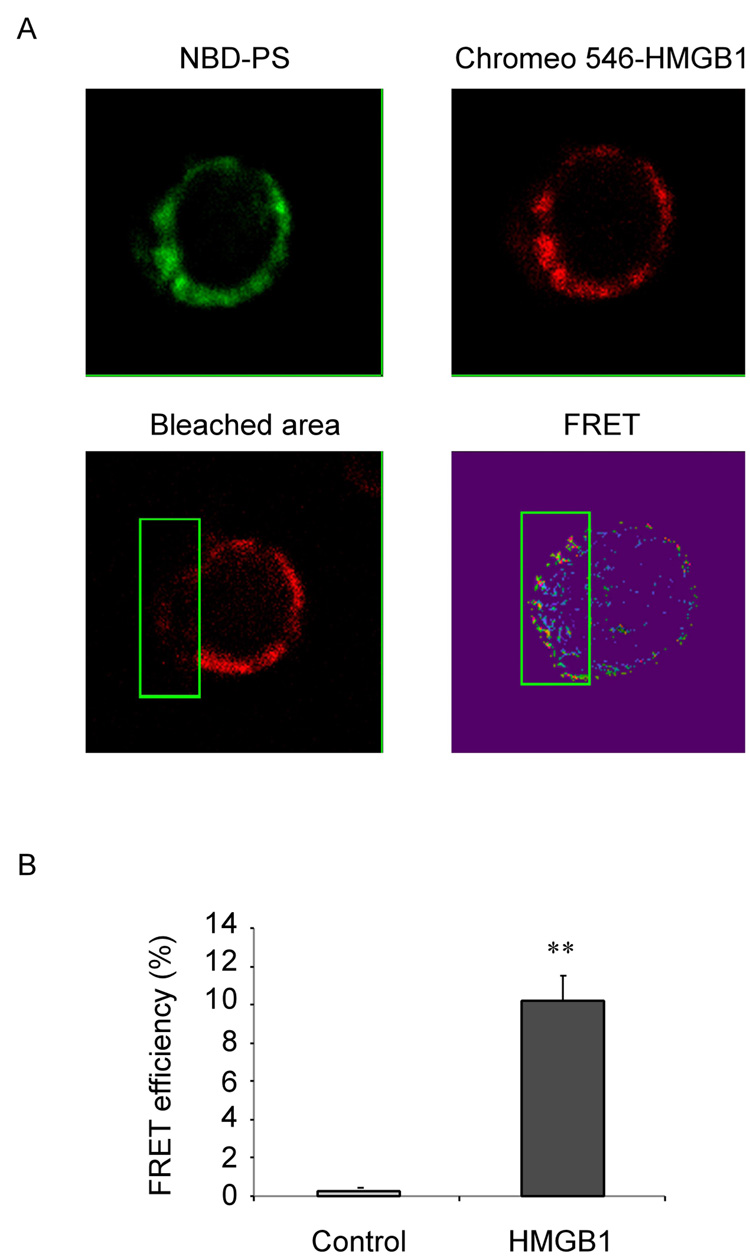

HMGB1 binds to phosphatidylserine on apoptotic neutrophils

It has been shown that HMGB1 can bind to the PS in vitro (16, 18). Additionally, as shown in Figure 3, we found that PS can abolish the inhibitory effect of HMGB1. Thus, we investigated whether HMGB1 can interact with PS on intact cells. For these experiments, apoptotic neutrophils were incubated with PS (NBD-PS) and Chromeo 546 labeled HMGB1. The distribution of PS and HMGB1 protein on the cell surface was then determined by confocal imaging, and the molecular interaction of HMGB1 and NBD-PS measured by FRET.

As shown in Figure 4A, both PS and HMGB1 were localized to the surface of apoptotic neutrophils. FRET spots, demonstrating interaction between HMGB1 and PS, appeared on the cell surface with the Acceptor (Chromeo 546-HMGB1, red fluorescence) being photo-bleached. In contrast, fewer FRET spots were observed on the cell surface of the same neutrophils that were not photo-bleached (Figure 4A). The FRET efficiency between PS and HMGB1 was significantly greater in the bleached area of the cell membrane as compared to the unbleached area (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. HMGB1 binds to phosphatidylserine on apoptotic neutrophils.

(A) HMGB1 binds to PS on the surface of apoptotic neutrophils. After heating at 42°C for 1 hr, neutrophils were incubated with 1 ug/ml Chromeo 546 labeled HMGB1 and 1 ug/ml NBD-PS for 3h at 37°C, and cytospin slides prepared. Chromeo 546 (acceptor) on the cell surface of a neutrophil (region within the green square) was photo-bleached and the remaining area of the same cell was left un-bleached. Images of the donor (NBD-PS, green), the acceptor (HMGB1, red), the area bleached, and the FRET spots are shown. (B) FRET efficiency between PS and HMGB1 is significantly increased after incubation with HMGB1. %FRET efficiency = (Donorpost – Donorprevious)/ Donorpost × 100. ** p < 0.01 versus control.

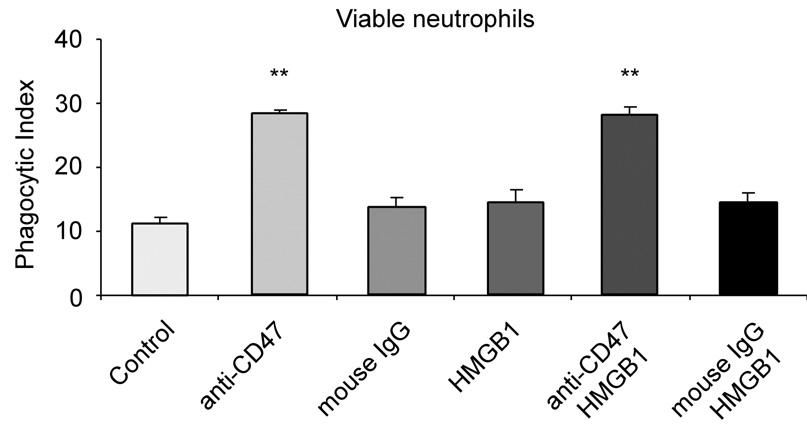

HMGB1 does not inhibit phosphatidylserine-independent phagocytosis

CD47 acts as a “don’t eat me” signal on the surface of viable cells, blocking phagocytosis by binding to SIRPα, a heavily glycosylated transmembrane protein with an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif (26). To test whether HMGB1 inhibits phagocytosis specifically through interactions with PS or whether CD47 might also be involved, we used anti-CD47 antibodies to block CD47 function, which induced the engulfment of functional, non-apoptotic neutrophils by macrophages (Figure 5). There was no effect of HMGB1 on the phagocytosis of viable neutrophils following treatment with CD47 antibodies, indicating the specificity of the interaction between PS and HMGB1 in inhibiting efferocytosis.

Figure 5. HMGB1 does not inhibit phosphatidylserine-independent phagocytosis.

Viable neutrophils were pre-treated with 1 µg/ml mouse anti-CD47 antibody or 1 µg/ml mouse IgG for 30 minutes, followed by washing with PBS. Phagocytosis assays were performed in the presence of 1 µg/ml HMGB1 or mouse IgG. ** p < 0.01 compared to control.

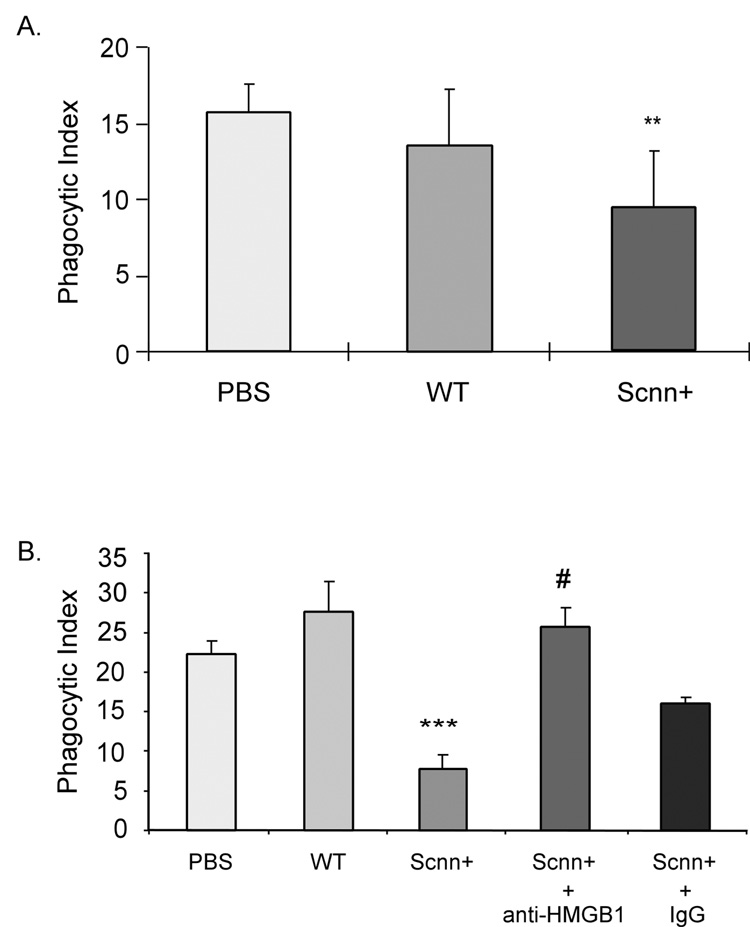

Contribution of increased pulmonary HMGB1 to alterations in neutrophil efferocytosis

Cystic fibrosis is associated with the accumulation of large numbers of neutrophils into the lungs, as well as a higher percentage of apoptotic neutrophils among the population of pulmonary neutrophils (7, 27). Previous studies have indicated that the increased percentage of apoptotic neutrophils in the airways of patients with cystic fibrosis reflects decreased efferocytosis (7). In recent studies, we found elevated levels of HMGB1 in bronchoalveolar lavages from Scnn+ mice, a murine model for cystic fibrosis, and also in sputum from patients with this disorder (28). Given the findings of the present experiments which showed that HMGB1 inhibits phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils, we hypothesized that the elevated pulmonary concentrations of HMGB1 associated with cystic fibrosis contribute to the decreased efferocytosis present in this condition. To examine this issue, we measured phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils exposed to bronchoalveolar lavage samples from control and Scnn+ mice.

As shown in Figure 6A, phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils was significantly reduced after incubation with bronchoalveolar lavage from Scnn+ mice, but not after exposure to bronchoalveolar lavage from control mice. Measured concentrations of HMGB1 in Scnn+ bronchoalveolar lavages were 1.36 ± 0.03 µg/ml, and were 0.76 ± 0.05 µg/ml in bronchoalveolar lavages from control mice. Incubation of bronchoalveolar lavages from Scnn+ mice with anti-HMGB1 antibodies restored the phagocytic index to control levels (Figure 6B), indicating that HMGB1 contained in these bronchoalveolar lavages was responsible for their inhibitory effects on efferocytosis.

Figure 6. Increased bronchoalveolar lavage HMGB1 contributes to alterations in neutrophil efferocytosis.

(A) BALF of Scnn+ mice significantly inhibits phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils by macrophages. Phagocytosis assays were performed in the presence of 12 µl of PBS, BALF from WT mice (n = 4), or BALF from Scnn+ mice (n = 5). Data are presented as mean ± SD. ** p < 0.01 compared to PBS and WT groups. (B) Anti-HMGB1 antibody abolishes increased phagocytosis of neutrophils induced by exposure to Scnn+ BALF. 12 µl of PBS, WT mouse BALF, Scnn+ BALF, Scnn+ BALF pre-incubated with 1 µg mouse anti-HMGB1 monoclonal antibodies for 30 min, or Scnn+ BALF pre-incubated with 1 µg mouse IgG was added to cultures of macrophages and apoptotic neutrophils. Phagocytosis assays were performed and the phagocytic index determined. *** p < 0.001 compared to WT; # p < 0.05 compared to Scnn+.

Discussion

Extracellular release of HMGB1 has potent proinflammatory effects and contributes to acute lung injury as well as other organ failures after pathophysiologic events such as endotoxemia, bacterial peritonitis, hemorrhage, ischemia/reperfusion injury, and burns (13, 29–36). In these settings, blockade of the actions of HMGB1 through administration of anti-HMGB1 antibodies or through the use of inhibitory fragments of HMGB1, such as the A box, decreased organ injury and improved survival. However, since recent studies (16, 37) have found that highly purified HMGB1 loses much of its ability to activate cells to produce cytokines and other proinflammatory mediators, determination of the mechanisms by which HMGB1 contributes to organ injury remains an important question.

The present experiments demonstrate that HMGB1 can diminish the phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils by macrophages both in vitro and in vivo. The mechanism of such inhibitory actions of HMGB1 appears to be through interaction with phosphatidylserine on the neutrophil membrane, thereby blocking an important ligand involved in phagocytosis. The ability of HMGB1 to bind to phosphatidylserine has previously been demonstrated under in vitro conditions (16), and the present experiments extend those findings to the intact cell. Of note, since HMGB1 was unable to affect the ability of anti-CD47 antibodies to increase phagocytosis of viable neutrophils, its role in efferocytosis appears to be specific and directly linked to interaction with phosphatidylserine. While previous studies (22, 38–40) have found that HMGB1 is capable of interactions with multiple intracellular and extracellular molecules, the present results, showing direct association between HMGB1 and phosphatidylserine by FRET as well as blockade of HMGB1’s inhibitory effects on neutrophil phagocytosis by exogenous phosphatidylserine, indicate that its role in efferocytosis is specifically due to interactions with phosphatidylserine.

Acute lung injury is characterized by the accumulation of activated neutrophils in the lungs (41). These pulmonary neutrophils produce proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β and TNF-α, and release reactive oxygen species as well as other mediators capable of damaging adjacent cell populations and contributing to tissue injury. Pulmonary levels of HMGB1 are increased in the setting of acute lung injury, and HMGB1 itself can produce pulmonary injury (30, 36). Therefore, interaction of elevated tissue concentrations of HMGB1 with phosphatidylserine exposed on the surfaces of neutrophils that have entered into early apoptosis, but remain activated to produce proinflammatory mediators, may diminish engulfment and removal of such neutrophils, allowing them to continue to contribute to and exacerbate the proinflammatory milieu associated with acute lung injury. In addition, inhibition by HMGB1 of phagocytosis of neutrophils in late apoptosis may exacerbate pulmonary inflammation by permitting these cells to release their intracellular contents directly into the lungs, rather than being neutralized within macrophages. Therefore, even if HMGB1 itself is unable to directly activate neutrophils, macrophages, and other cellular populations involved in acute lung injury, its ability to diminish phagocytosis and clearance of neutrophils from the lungs would provide an important mechanism enhancing the severity of acute lung injury. Such inhibitory actions of HMGB1 on efferocytosis would also explain the beneficial effects of anti-HMGB1 therapies in acute lung injury.

Recent studies have shown that elevated circulating and tissue concentrations of HMGB1 are present in chronic inflammatory conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis and cystic fibrosis (15, 28, 42–46). While the role of activated neutrophils is not well defined in chronic autoimmune disorders, neutrophils have been demonstrated to play a central role in contributing to lung injury in cystic fibrosis (6, 27). Neutrophils are also involved in other pulmonary inflammatory conditions, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), pneumonia, and chronic bronchiectasis (47, 48). Recent data have found elevated HMGB1 levels in cystic fibrosis and in patients with severe pneumonia (28, 49). In the present studies, HMGB1 in bronchoalveolar lavages from Scnn+ mice, a murine model for cystic fibrosis, was shown to be directly involved in inhibiting phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils. The ability of HMGB1 to inhibit neutrophil clearance in cystic fibrosis and other pulmonary conditions associated with ongoing neutrophil dependent inflammation would be expected to contribute to ongoing pulmonary injury, suggesting a role for anti-HMGB1 therapies in these settings.

Acknowledgments

We thank Albert Tousson of the UAB imaging microscopy core facility for preparation of the FRET images. We thank Drs. Steven Rowe and Jaroslaw Zmijewski for insightful suggestions. We also thank Youhong Zhang for general assistance.

This work was supported by grants P01 HL068743 and P50 GM049222 (to E.A.) from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- 1.Haslett C. Granulocyte apoptosis and its role in the resolution and control of lung inflammation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:S5–S11. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.supplement_1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Voll RE, Herrmann M, Roth EA, Stach C, Kalden JR, Girkontaite I. Immunosuppressive effects of apoptotic cells. Nature. 1997;390:350–351. doi: 10.1038/37022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fadok VA, Bratton DL, Konowal A, Freed PW, Westcott JY, Henson PM. Macrophages that have ingested apoptotic cells in vitro inhibit proinflammatory cytokine production through autocrine/paracrine mechanisms involving TGF-beta, PGE2, and PAF. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:890–898. doi: 10.1172/JCI1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ishii Y, Hashimoto K, Nomura A, Sakamoto T, Uchida Y, Ohtsuka M, Hasegawa S, Sagai M. Elimination of neutrophils by apoptosis during the resolution of acute pulmonary inflammation in rats. Lung. 1998;176:89–98. doi: 10.1007/pl00007597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cox G, Crossley J, Xing Z. Macrophage engulfment of apoptotic neutrophils contributes to the resolution of acute pulmonary inflammation in vivo. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1995;12:232–237. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.12.2.7865221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bianchi SM, Prince LR, McPhillips K, Allen L, Marriott HM, Taylor GW, Hellewell PG, Sabroe I, Dockrell DH, Henson PW, Whyte MK. Impairment of Apoptotic Cell Engulfment by Pyocyanin, a Toxic Metabolite of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007 doi: 10.1164/rccm.200612-1804OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vandivier RW, Fadok VA, Hoffmann PR, Bratton DL, Penvari C, Brown KK, Brain JD, Accurso FJ, Henson PM. Elastase-mediated phosphatidylserine receptor cleavage impairs apoptotic cell clearance in cystic fibrosis and bronchiectasis. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:661–670. doi: 10.1172/JCI13572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herrmann M, Voll RE, Zoller OM, Hagenhofer M, Ponner BB, Kalden JR. Impaired phagocytosis of apoptotic cell material by monocyte-derived macrophages from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:1241–1250. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199807)41:7<1241::AID-ART15>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baumann I, Kolowos W, Voll RE, Manger B, Gaipl U, Neuhuber WL, Kirchner T, Kalden JR, Herrmann M. Impaired uptake of apoptotic cells into tingible body macrophages in germinal centers of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:191–201. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200201)46:1<191::AID-ART10027>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lauber K, Blumenthal SG, Waibel M, Wesselborg S. Clearance of apoptotic cells: getting rid of the corpses. Mol Cell. 2004;14:277–287. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00237-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kenis H, van Genderen H, Deckers NM, Lux PA, Hofstra L, Narula J, Reutelingsperger CP. Annexin A5 inhibits engulfment through internalization of PS-expressing cell membrane patches. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312:719–726. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Munoz LE, Franz S, Pausch F, Furnrohr B, Sheriff A, Vogt B, Kern PM, Baum W, Stach C, von Laer D, Brachvogel B, Poschl E, Herrmann M, Gaipl US. The influence on the immunomodulatory effects of dying and dead cells of Annexin V. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:6–14. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0306166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang H, Bloom O, Zhang M, Vishnubhakat JM, Ombrellino M, Che J, Frazier A, Yang H, Ivanova S, Borovikova L, Manogue KR, Faist E, Abraham E, Andersson J, Andersson U, Molina PE, Abumrad NN, Sama A, Tracey KJ. HMG-1 as a late mediator of endotoxin lethality in mice. Science. 1999;285:248–251. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5425.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scaffidi P, Misteli T, Bianchi ME. Release of chromatin protein HMGB1 by necrotic cells triggers inflammation. Nature. 2002;418:191–195. doi: 10.1038/nature00858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ulloa L, Batliwalla FM, Andersson U, Gregersen PK, Tracey KJ. High mobility group box chromosomal protein 1 as a nuclear protein, cytokine, and potential therapeutic target in arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:876–881. doi: 10.1002/art.10854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rouhiainen A, Tumova S, Valmu L, Kalkkinen N, Rauvala H. Pivotal advance: analysis of proinflammatory activity of highly purified eukaryotic recombinant HMGB1 (amphoterin) J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:49–58. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0306200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tian J, Avalos AM, Mao SY, Chen B, Senthil K, Wu H, Parroche P, Drabic S, Golenbock D, Sirois C, Hua J, An LL, Audoly L, La Rosa G, Bierhaus A, Naworth P, Marshak-Rothstein A, Crow MK, Fitzgerald KA, Latz E, Kiener PA, Coyle AJ. Toll-like receptor 9-dependent activation by DNA-containing immune complexes is mediated by HMGB1 and RAGE. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:487–496. doi: 10.1038/ni1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rouhiainen A, Imai S, Rauvala H, Parkkinen J. Occurrence of amphoterin (HMG1) as an endogenous protein of human platelets that is exported to the cell surface upon platelet activation. Thromb Haemost. 2000;84:1087–1094. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li J, Wang H, Mason JM, Levine J, Yu M, Ulloa L, Czura CJ, Tracey KJ, Yang H. Recombinant HMGB1 with cytokine-stimulating activity. J Immunol Methods. 2004;289:211–223. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2004.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yum HK, Arcaroli J, Kupfner J, Shenkar R, Penninger JM, Sasaki T, Yang KY, Park JS, Abraham E. Involvement of phosphoinositide 3-kinases in neutrophil activation and the development of acute lung injury. J Immunol. 2001;167:6601–6608. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Licht R, Jacobs CW, Tax WJ, Berden JH. An assay for the quantitative measurement of in vitro phagocytosis of early apoptotic thymocytes by murine resident peritoneal macrophages. J Immunol Methods. 1999;223:237–248. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(98)00212-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park JS, Gamboni-Robertson F, He Q, Svetkauskaite D, Kim JY, Strassheim D, Sohn JW, Yamada S, Maruyama I, Banerjee A, Ishizaka A, Abraham E. High mobility group box 1 protein interacts with multiple Toll-like receptors. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;290:C917–C924. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00401.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Callahan MK, Williamson P, Schlegel RA. Surface expression of phosphatidylserine on macrophages is required for phagocytosis of apoptotic thymocytes. Cell Death Differ. 2000;7:645–653. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fadok VA, Voelker DR, Campbell PA, Cohen JJ, Bratton DL, Henson PM. Exposure of phosphatidylserine on the surface of apoptotic lymphocytes triggers specific recognition and removal by macrophages. J Immunol. 1992;148:2207–2216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krahling S, Callahan MK, Williamson P, Schlegel RA. Exposure of phosphatidylserine is a general feature in the phagocytosis of apoptotic lymphocytes by macrophages. Cell Death Differ. 1999;6:183–189. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gardai SJ, McPhillips KA, Frasch SC, Janssen WJ, Starefeldt A, Murphy-Ullrich JE, Bratton DL, Oldenborg PA, Michalak M, Henson PM. Cell-surface calreticulin initiates clearance of viable or apoptotic cells through trans-activation of LRP on the phagocyte. Cell. 2005;123:321–334. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watt AP, Courtney J, Moore J, Ennis M, Elborn JS. Neutrophil cell death, activation and bacterial infection in cystic fibrosis. Thorax. 2005;60:659–664. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.038240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rowe SM, Solomon GM, Livraghi A, Jackson PL, O'Neal WK, McQuaid DB, Gaggar A, Clancy JP, Sorscher EJ, Abraham E, Liu G. Evidence for a pathogenic role of HMGB1 in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:A448. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200712-1894OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sitia G, Iannacone M, Muller S, Bianchi ME, Guidotti LG. Treatment with HMGB1 inhibitors diminishes CTL-induced liver disease in HBV transgenic mice. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:100–107. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0306173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ogawa EN, Ishizaka A, Tasaka S, Koh H, Ueno H, Amaya F, Ebina M, Yamada S, Funakoshi Y, Soejima J, Moriyama K, Kotani T, Hashimoto S, Morisaki H, Abraham E, Takeda J. Contribution of High Mobility Group Box-1 to the development of ventilator-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006 doi: 10.1164/rccm.200605-699OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qin S. Role of HMGB1 in apoptosis-mediated sepsis lethality. J. Exp. Med. 2006;203:1637–1642. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsung A, Sahai R, Tanaka H, Nakao A, Fink MP, Lotze MT, Yang H, Li J, Tracey KJ, Geller DA, Billiar TR. The nuclear factor HMGB1 mediates hepatic injury after murine liver ischemia-reperfusion. J. Exp. Med. 2005;201:1135–1143. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang H, Ochani M, Li J, Qiang X, Tanovic M, Harris HE, Susarla SM, Ulloa L, Wang H, DiRaimo R, Czura CJ, Roth J, Warren HS, Fink MP, Fenton MJ, Andersson U, Tracey KJ. Reversing established sepsis with antagonists of endogenous high-mobility group box 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:296–301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2434651100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fang WH, Yao YM, Shi ZG, Yu Y, Wu Y, Lu LR, Sheng ZY. The significance of changes in high mobility group-1 protein mRNA expression in rats after thermal injury. Shock. 2002;17:329–333. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200204000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim JY, Park JS, Strassheim D, Douglas I, Diaz Del Valle F, Asehnoune K, Mitra S, Kwak SH, Yamada S, Maruyama I, Ishizaka A, Abraham E. HMGB1 contributes to the development of acute lung injury after hemorrhage. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;288:L958–L965. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00359.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abraham E, Arcaroli J, Carmody A, Wang H, Tracey KJ. HMG-1 as a mediator of acute lung inflammation. J Immunol. 2000;165:2950–2954. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.6.2950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tian J, Avalos AM, Mao S-Y, Chen B, Senthil K, Wu H, Parroche P, Drabic S, Golenbock D, Sirois C, Hua J, An LL, Audoly L, La Rosa G, Bierhaus A, Naworth P, Marshak-Rothstein A, Crow MK, Fitzgerald KA, Latz E, Kiener PA, Coyle AJ. Toll-like receptor 9-dependent activation by DNA-containing immune complexes is mediated by HMGB1 and RAGE. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:487–496. doi: 10.1038/ni1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tian J, Avalos AM, Mao SY, Chen B, Senthil K, Wu H, Parroche P, Drabic S, Golenbock D, Sirois C, Hua J, An LL, Audoly L, La Rosa G, Bierhaus A, Naworth P, Marshak-Rothstein A, Crow MK, Fitzgerald KA, Latz E, Kiener PA, Coyle AJ. Toll-like receptor 9-dependent activation by DNA-containing immune complexes is mediated by HMGB1 and RAGE. Nat Immunol. 2007 doi: 10.1038/ni1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu M, Wang H, Ding A, Golenbock DT, Latz E, Czura CJ, Fenton MJ, Tracey KJ, Yang H. HMGB1 signals through toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 and TLR2. Shock. 2006;26:174–179. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000225404.51320.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dintilhac A, Bernues J. HMGB1 interacts with many apparently unrelated proteins by recognizing short amino acid sequences. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:7021–7028. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108417200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abraham E. Neutrophils and acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:S195–S199. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000057843.47705.E8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Czura CJ, Yang H, Amella CA, Tracey KJ. HMGB1 in the Immunology of Sepsis (Not Septic Shock) and Arthritis. Adv Immunol. 2004;84:181–200. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(04)84005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang H, Yang H, Tracey KJ. Extracellular role of HMGB1 in inflammation and sepsis. J Intern Med. 2004;255:320–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2003.01302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Andersson U, Erlandsson-Harris H. HMGB1 is a potent trigger of arthritis. J. Intern. Med. 2004;255:344–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2003.01303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taniguchi N, Kawahara K, Yone K, Hashiguchi T, Yamakuchi M, Goto M, Inoue K, Yamada S, Ijiri K, Matsunaga S, Nakajima T, Komiya S, Maruyama I. High mobility group box chromosomal protein 1 plays a role in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis as a novel cytokine. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:971–981. doi: 10.1002/art.10859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sadikot RT, Christman JW, Blackwell TS. Molecular targets for modulating lung inflammation and injury. Curr Drug Targets. 2004;5:581–588. doi: 10.2174/1389450043345281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yoshikawa T, Dent G, Ward J, Angco G, Nong G, Nomura N, Hirata K, Djukanovic R. Impaired neutrophil chemotaxis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:473–479. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200507-1152OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Quint JK, Wedzicha JA. The neutrophil in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2007;119:1065–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.12.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Angus DC, Yang L, Kong L, Kellum JA, Delude RL, Tracey KJ, Weissfeld L. Circulating high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) concentrations are elevated in both uncomplicated pneumonia and pneumonia with severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1061–1067. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000259534.68873.2A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]