Abstract

The immunological response to influenza virus infection, like many other viruses, is characterized by robust production of proinflammatory cytokines, including type I and II interferon (IFN), which induce a number of antiviral effects and are essential for priming the innate and adaptive cellular components of the immune response. Here, we demonstrate that influenza virus infection induces the expression of functional TRAIL on human peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) populations. Consistent with previous studies examining TRAIL upregulation, increased TRAIL expression correlated with increased type I and II IFN levels in PBMC cultures. Interestingly, dilution of these cytokines resulted in decreased expression of TRAIL, TRAIL upregulation was not dependent on active viral infection, and TRAIL was observed on NS-1 negative cells. Furthermore, influenza virus infection of lung adenocarcinoma cells (A549) resulted in increased sensitization to TRAIL-induced apoptosis compared to uninfected A549. Infected PBMC expressing TRAIL preferentially killed infected A549, while not affecting uninfected cells, and the addition of soluble TRAIL-R2:Fc blocked the lysis of infected cells, demonstrating TRAIL-dependent killing of infected cells. Collectively, these data show that TRAIL expression is induced on primary human innate and adaptive immune cells in response to cytokines produced during influenza infection, and that TRAIL-sensitivity is increased in influenza virus-infected cells. These data also suggest that TRAIL is a primary mechanism used by influenza-stimulated human PBMC to kill influenza-infected target cells and reinforce the importance of cytokines produced in response to TLR agonists in enhancing cellular immune effector functions.

Keywords: TRAIL, influenza, ssRNA, Toll-like receptor

INTRODUCTION

Influenza virus infection of the respiratory tract induces both innate and adaptive immune responses that are targeted to control and eliminate the viral infection. Studies investigating the protective immunity induced by primary influenza virus infection revealed that the clearance of infected epithelial cells by CD8+ T cells utilizes either Fas- or perforin-dependent direct killing mechanisms [1–3]. These CD8+ T cells first appear in the lung around day 4-post infection [4–6], where their continued expansion and accumulation correspond with virus clearance [6]. Interestingly, in a subset of animals deficient in both perforin and Fas, decreased influenza virus titers were observed on day 14 relative to day 10 post infection [1], suggesting the existence of an additional mechanism by which CD8+ T cells kill influenza-infected target cells.

In addition to the Fas-FasL and perforin-granzyme B pathways, CD8+ T cells can also utilize a TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)/TRAIL receptor-dependent mechanism to eliminate virally-infected cells [7–13]. TRAIL is one of several TNF family members capable of inducing apoptosis [14, 15], and does so in humans through interactions with TRAIL-R1 or -R2 [16]. Subsequent to their ligation, both TRAIL-R1 and –R2 stimulate apoptosis through Fas-associated death domains (FADD) recruitment to the trimerized receptor and caspase activation [16]. While TRAIL has received great attention in cancer therapy contexts because it selectively induces apoptosis in tumor cells but not normal cells, it is also proving to be a potent inducer of apoptosis in virally-infected cells that are normally TRAIL-resistant when uninfected [7, 8, 13].

More recent reports have implied roles for TRAIL in the immune response to influenza virus infection. A plasmacytoid dendritic cell (pDC) cell line (GEN2.2) showed marked upregulation of TRAIL, as well as increased sensitivity to TRAIL, following influenza virus infection [17]. Additionally, primary human macrophages infected with H5N1 or H9N2 influenza virus strains upregulate TRAIL expression and are able to induce apoptosis in Jurkat T cells using a TRAIL-dependent mechanism [18]. The importance of TRAIL in the elimination of influenza virus has been suggested in an animal model where administration of a blocking anti-TRAIL mAb significantly delayed clearance of influenza virus in the lungs [19]. This study also demonstrated that TRAIL expression was increased on a fraction of bulk CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, as well as NK cells, following influenza virus infections. Together, these results suggest a possible role for TRAIL-dependent apoptosis of influenza virus-infected cells. However, none of these studies have directly examined TRAIL expression on primary human cells that comprise the innate and adaptive cellular immune response to influenza virus infection.

Based on these previous studies, we hypothesized that human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) would respond to influenza in vitro by increasing TRAIL expression and show enhanced TRAIL-specific killing. Our data demonstrate that TRAIL expression is upregulated on multiple PBMC populations in response to influenza virus stimulation, and this upregulation is dependent on the proinflammatory cytokines [specifically type I and II interferon (IFN)] produced in response to influenza virus infection or stimulation with influenza virus genome, but is not dependent on direct infection. Importantly, our data also show for the first time that TRAIL sensitivity is increased in alveolar epithelial cells infected with influenza virus, as demonstrated with either recombinant TRAIL or TRAIL-expressing, influenza-stimulated PBMC. Our findings suggest that TRAIL-induced apoptosis is an additional effector pathway utilized by the cellular immune response to influenza virus infections, and that sensitivity to TRAIL-induced apoptosis is specifically increased in influenza-infected cells compared with uninfected cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and mAb

Reagents and sources were as follows: UCHT1, FITC-conjugated IgG1 anti-human CD3; M5E2 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA), FITC-conjugated IgG2a anti-human CD14 (BD Bioscience, San Diego, CA); HIB19, FITC-conjugated IgG1 anti-human CD19 (eBioscience); NCAM16.2, FITC-conjugated IgG2b anti-human CD56; RIK-2, IgG1 anti-human TRAIL (a gift from Dr. H. Yagita, Juntendo University, Tokyo, Japan); IgG1-biotin isotype control (Caltag Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA); 4SB3, PE-conjugated IgG1 anti-human IFN-γ (BD Bioscience, San Diego, CA); IgG1-PE isotype control (Caltag Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA); 1A7, mouse anti-NS1 (a gift from Dr. Jonathan Yewdell, NAIAD); and APC-labeled goat F(ab′)2 anti-mouse IgG (Caltag Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA). The soluble fusion proteins TRAIL-R2:Fc and Fas:Fc were purchased from Alexis Biochemicals (San Diego, CA). CpG ODN 2216 (ggGGGACGATCGTCgggggG) was synthesized by Sigma Genosys (The Woodlands, TX), and the sequence is 5′-3′, lower case letters are 5′ of phosphothiorate linkages, and upper case letter are 5′ of phosphodiester linkages. Poly I:C and ssRNA/LyoVec [a single-stranded GU-righ oligonucleotide (5′GCCCGUCUGUUGUGUGACUC-3′ with all phosphothioate linkages) complexed with LyoVec] were purchased from Invivogen (San Diego, CA).

Virus preparation

Influenza A viruses A/PuertoRico/8/34 (PR8; H1N1) was grown in the allantoic fluid of 10 d old embryonated chicken eggs for 2 d at 37°C, as previously described [6]. Allantoic fluid was harvested and stored at −80°C. For UV inactivation, virus preparations were dialyzed overnight and subsequently exposed to a UV lamp at 15cm for 30 minutes at room temperature.

Tumor cell lines

The human melanoma cell line WM 793 was obtained from Dr. M. Herlyn (Wistar Institute, Philadelphia, PA), and cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin, streptomycin, sodium pyruvate, non-essential amino acids, and HEPES (hereafter referred to as complete DMEM). The human lung adenocarcinoma cell line A549 was purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA) and cultured in RPMI-1640 supplemented as above (complete RPMI).

Isolation of influenza genome

Samples of stock virus were spun twice (3000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C) to remove debris. Supernatants were collected and then spun in an ultracentrifuge to pellet virions (27,000 rpm for 3 h at 4°C in a SW60 rotor). Virions were lysed in detergent (Igepal/Triton X100/PBS) by passing through a syringe and suspended in TRIZOL (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at a 2:1 TRIZOL:detergent ratio. RNA was then harvested according to manufacturer’s protocol.

Preparation of PBMC

PBMC were isolated from normal, healthy donors by standard density gradient centrifugation over Ficoll-Paque Plus (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden). PBMC (5 X 106 cells/2 ml/well in a 6 well plate) were cultured in complete RPMI 1640 alone or in complete RPMI containing CpG ODN (1 μg/ml), poly I:C (1 μg/ml), ssRNA (1 μg/ml) for 24 h. PBMC infection with influenza (1 pfu/cell) was performed by first incubating the cells with virus in PBS on ice for 30 min, then at 37°C for 30 min. Cell were washed twice with PBS, and then cultured for 24 h in complete RPMI. In some experiments, PMBC were infected using the protocol described, then decreasing numbers of infected or uninfected cells were cultured in equivalent volumes of media. In some experiments, plasmacytoid DC (pDC) were depleted from the PBMC using the CD304 (BDCA-4/Neutropilin-1) microbead kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn CA). pDC depletion was verified by measuring the presence of CD123+CD303+ (BDCA-2) cells in the PBMC using FITC-conjugated anti-CD123 and PE-conjugated anti-CD303 mAb (Miltenyi Biotec). In every experiment, there were no detectable CD123+CD303+ cells remaining in the PBMC (data not shown).

PBMC culture and supernatant transfer

PBMC were depleted of pDC, infected with influenza virus (or not infected), and cultured as described above at a cell density of 106 cells/well in 1 ml media. After 24 h, supernatants from infected cultures were collected and transferred to freshly-isolated uninfected PBMC. After another 24 hour culture, the PBMC were harvested and analyzed by flow cytometry as described below. In some culutures, IFN-α and/or IFN-γ were neutralized using 1μg/ml anti-IFN-α (PBL Biomedical, Piscataway, NJ) or 5μg/ml anti-IFN-γ (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) Ab or isotype control Ab for 30 min prior to supernatant transfer. As a positive control for inducing TRAIL expression, uninfected PBMC were treated with 500ng/ml IFN-α (Cell Signaling Technologies, Danvers, MA) for 24 h.

Flow cytometry

Cell analysis was performed on a FACScan (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) with >104 cells analyzed per sample. For multi-color cell analysis, cells were combined in a 96-well round-bottom plate with 2 μl each of the direct FITC-labeled and biotin-labeled mAb and then incubated at 4°C for 30 min. Following three washes with PBS containing 2 mg/ml BSA and 0.02% NaN3 (FACS buffer), 40 μl of PE-labeled streptavidin (1:100 dilution; Caltag Laboratories) was added for an additional 30 min. Cells were either analyzed immediately or fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde until analysis. For intracellular stain of NS1 protein, cells were labeled with surface markers as described, fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde, permeablized in FACS buffer with 0.5% saponin, and incubated with anti-NS1 or isotype control at 4°C for 30 min. Following three washes with FACS buffer with saponin, 2 μl of APC-labeled anti-mouse IgG was added for an additional 30 min. Cells were either analyzed immediately or fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde until analysis. For intracellular cytokine staining for IFN-γ, brefeldin A was added to the last 5 h of the 24 h cell culture after influenza infection or TLR stimulation; subsequently, cells were labeled with surface markers as described, fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde, permeablized in FACS buffer with 0.5% saponin, and incubated with anti-IFN-γ or isotype control at 4°C for 30 min. Cells were either analyzed immediately or fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde until analysis.

PBMC-mediated killing

Unstimulated or stimulated PBMC were cultured as described above. WM 793 tumor cells were labeled with 100 μCi of 51Cr for 1 h at 37°C, washed three times, and resuspended in complete medium. To determine TRAIL-induced death, 51Cr-labeled tumor cells (104/well) were incubated with varying numbers of effector cells for 14 h. In some cultures, TRAIL-R2:Fc or Fas:Fc (20 μg/ml) were added to the PBMC 15 min prior to adding tumor cell targets. All cytotoxicity assays were performed in 96-well round-bottom plates and the percent specific lysis was calculated as: 100 X (experimental c.p.m. - spontaneous c.p.m.)/(total c.p.m. - spontaneous c.p.m.). Spontaneous and total 51Cr release were determined in the presence of either medium alone or 1% NP-40, respectively. The presence of TRAIL-R2:Fc or Fas:Fc during the assay had no effect on the level of spontaneous release by the targets.

IFN-α and IFN-γ ELISA

Human IFN-α and –γ protein levels produced after influenza virus infection or TLR agonist stimulation were quantified using a sandwich ELISA purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN).

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using ANOVA to assess differences among the study groups using SigmaStat 3.5 (Systat Software, Richmond, CA), and statistical significance was determined as p ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

Influenza virus infection of human PBMC induces the expression of functional TRAIL

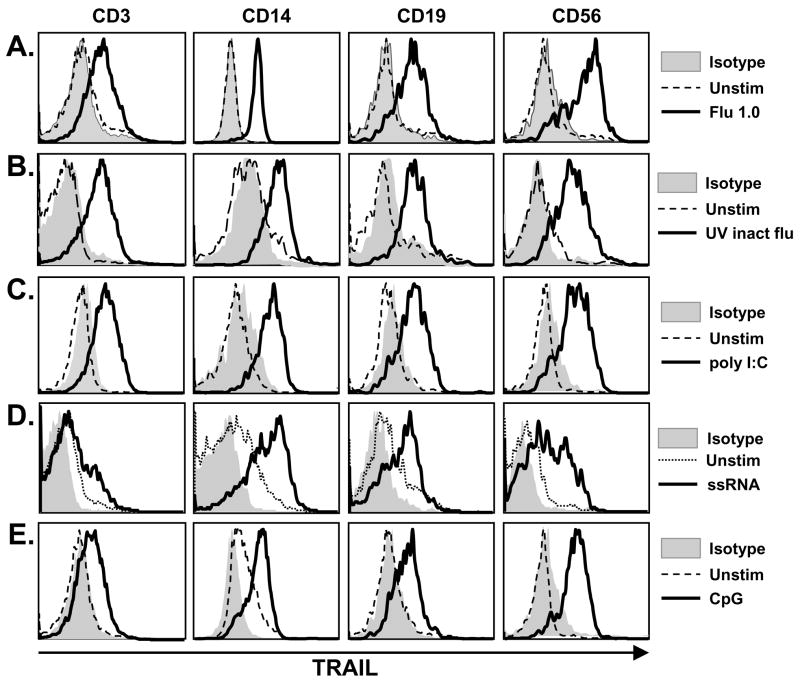

Influenza virus infection induces a robust inflammatory reaction, hallmarked by the production of the anti-viral cytokines type I and type II IFN [13, 20, 21]. The TRAIL promoter contains IFN-response elements, resulting in the IFN-driven expression of TRAIL on multiple human PBMC populations [13, 22]. Thus, our initial experiments were designed to examine TRAIL expression on human PBMC after influenza virus infection. Peripheral blood T cells (CD3+), Mφ (CD14+), B cells (CD19+), and NK cells (CD56+) can express functional TRAIL [23–25]; thus, these populations within bulk PBMC were examined by two-color flow cytometry for TRAIL expression 24 h after influenza virus infection. When infected, significant TRAIL expression was observed on all four major PBMC populations (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

TRAIL expression on human PBMC after influenza virus infection or TLR agonist stimulation. PBMC were infected with (A) viable or (B) UV-inactivated influenza (as described in the Materials and Methods) or stimulated with the TLR agonists (C) poly I:C, (D) ssRNA, or (E) CpG ODN. Surface TRAIL expression was analyzed 24 h later on CD3+, CD14+, CD19+, and CD56+ cells using two-color flow cytometry. Representative results are shown in histograms based on 104 gated cells in all conditions, and cell viability was >95%, as assessed by propidium iodide exclusion. Similar results were observed using at least 4 different PBMC donors.

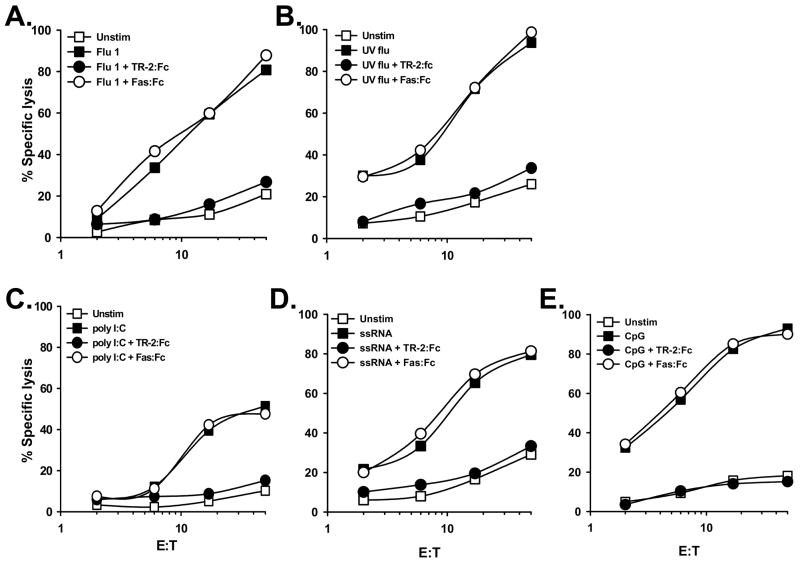

Concurrent experiments were performed to determine whether the TRAIL expressed on the influenza-infected cells was functional. Thus, human PBMC were isolated from normal healthy volunteers and infected with influenza. After culturing for 24 h, the PBMC were then incubated with the TRAIL-sensitive human melanoma tumor cell line WM 793 [26]. Uninfected PBMC demonstrated minimal cytotoxic activity toward WM 793, whereas influenza-infected PBMC were efficient killers of these TRAIL-sensitive target cells over a range of effector-target cell ratios (Figure 2A). These data were reproducible using PBMC from multiple donors (data not shown). To confirm that the observed PBMC cytotoxic activity was indeed TRAIL-dependent, influenza-infected PBMC were incubated with either TRAIL-R2:Fc [27] or Fas:Fc prior to their incubation with the target cells. Under these conditions, TRAIL-R2:Fc reduced target cell death to control (uninfected PBMC effectors) levels, whereas Fas:Fc did not inhibit the ability of the influenza-infected PBMC to mediate target cell lysis (Figure 2A). Similar results were also observed when infecting the PBMC with UV-inactivated influenza (Figures 1B & 2B), indicating that infection with a replication-competent influenza virus was not required to induce TRAIL expression. Collectively, these results demonstrate that PBMC mediate TRAIL-induced cell lysis following influenza virus infection.

Figure 2.

TRAIL-mediated cytotoxicity by human PBMC occurs after influenza virus infection or stimulation with TLR agonists. PBMC were infected with (A) viable or (B) UV-inactivated influenza (as described in the Materials and Methods) or stimulated with the TLR agonists (C) poly I:C, (D) ssRNA, or (E) CpG ODN. After 24 h, the PBMC were harvested and cultured for 14 h with 51Cr-labeled WM 793 target cells at the indicated effector-target cell ratios. For each condition, TRAIL-R2:Fc (20 μg/ml) inhibited target cell killing, while Fas:Fc (20 μg/ml) did not. Data points represent the mean of triplicate wells, and experiments were repeated at least three times using different donor PBMC with similar results. For clarity, SD bars were omitted from the graphs, but were <10% of the value of all points.

Nucleic acid TLR agonists induce functional TRAIL expression on PBMC

The Toll-like receptors (TLR) serve as first-line receptors for innate immune cell detection of pathogenic infections by recognizing conserved molecular motifs, which are known as pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) [28, 29]. Ten human TLR have been identified that recognize unique PAMPs from bacteria, viruses, fungi, and protozoa. Viruses that enter endocytic compartments, such as influenza, are recognized by TLR3 (specific for double-stranded RNA (dsRNA)), TLR7 (specific for single-stranded RNA (ssRNA)), and TLR9 (specific for CpG motifs in unmethylated DNA) [28, 29]. With this in mind, we next tested the ability of TLR3 (poly I:C), TLR7 (ssRNA), and TLR9 (CpG ODN) agonists to induce TRAIL on PBMC. PBMC stimulation with either the poly I:C or ssRNA led to TRAIL upregulation on multiple PBMC populations, with CD14+ Mφ showing the highest increase in expression (Figure 1C & D). The broad expression of TRAIL induced by poly I:C and ssRNA also resulted in substantial target cell lysis that was completely inhibited upon inclusion of soluble TRAIL-R2:Fc, but not Fas:Fc (Figure 2C & D). Consistent with previous reports from our laboratory [30, 31], CpG ODN was a potent inducer of TRAIL on all four PBMC populations examined (Figure 1E), resulting in significant TRAIL-specific cytotoxic activity (Figure 2E).

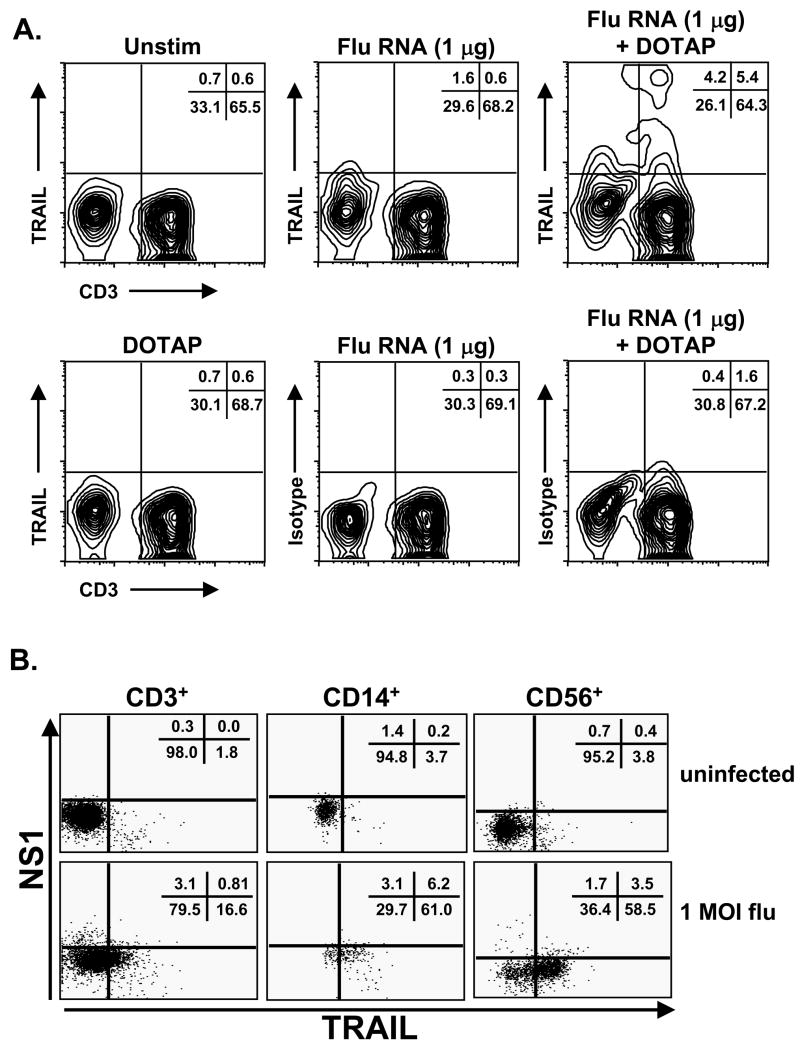

Stimulation with influenza genome is sufficient to induce TRAIL expression on PBMC

In vitro influenza infection of PBMC could stimulate TRAIL upregulation through a number of different mechanisms. To determine the ability of influenza virus genome to stimulate TRAIL induction, the genetic material from UV-inactivated influenza was isolated and used to stimulate PBMC. The influenza ssRNA genome was a competent TRAIL-inducing agent, as TRAIL was expressed on T cells (Figure 3A), as well as other PBMC populations (data not shown), following 24 h culture with influenza RNA mixed with DOTAP. In contrast, stimulation of PBMC with influenza proteins was not sufficient to induce TRAIL expression (data not shown). While our UV inactivation protocol prevents new virion production [6], it is possible that influenza viral coat proteins could be modified with some UV inactivation protocols that would alter viral immunogenicity. Interestingly, an examination of TRAIL expression coincidental with influenza virus proteins following infection suggested that TRAIL expression was not dependent on direct infection of the TRAIL-expressing cell, as populations of NS1-negative CD3+, CD14+, and CD56+ cells expressed TRAIL (Figure 3B). This is based on the lack of detectable NS-1 by flow cytometry, a nonstructural protein not expressed in the virion and only expressed in cells with replicating virus. Thus, these results demonstrate that upregulation of functional TRAIL on multiple PBMC populations occurs in response to stimulation with the influenza virus genome, but this upregulation does not appear to be dependent on direct infection of the TRAIL-expressing cell.

Figure 3.

Influenza RNA stimulates TRAIL expression on human T cells. (A) RNA was isolated from UV-inactivated influenza particles (as described in the Materials and Methods), and used to stimulate PBMC at the indicated concentrations. To facilitate uptake, RNA was mixed with DOTAP. As controls, PBMC were incubated with DOTAP alone or influenza RNA without DOTAP. After 24 h, cells were collected, and processed to examine TRAIL expression on CD3+ T cells. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments using different donor PBMC. (B) PBMC were infected with influenza and cultured for 24 hours. Surface TRAIL expression and intracellular NS1 expression were analyzed on CD3+, CD14+, and CD56+ cells using three-color flow cytometry. Representative results are shown in histograms based on 104 gated cells in all conditions, and cell viability was >95%, as assessed by propidium iodide exclusion. Similar results were observed using 2 different PBMC donors.

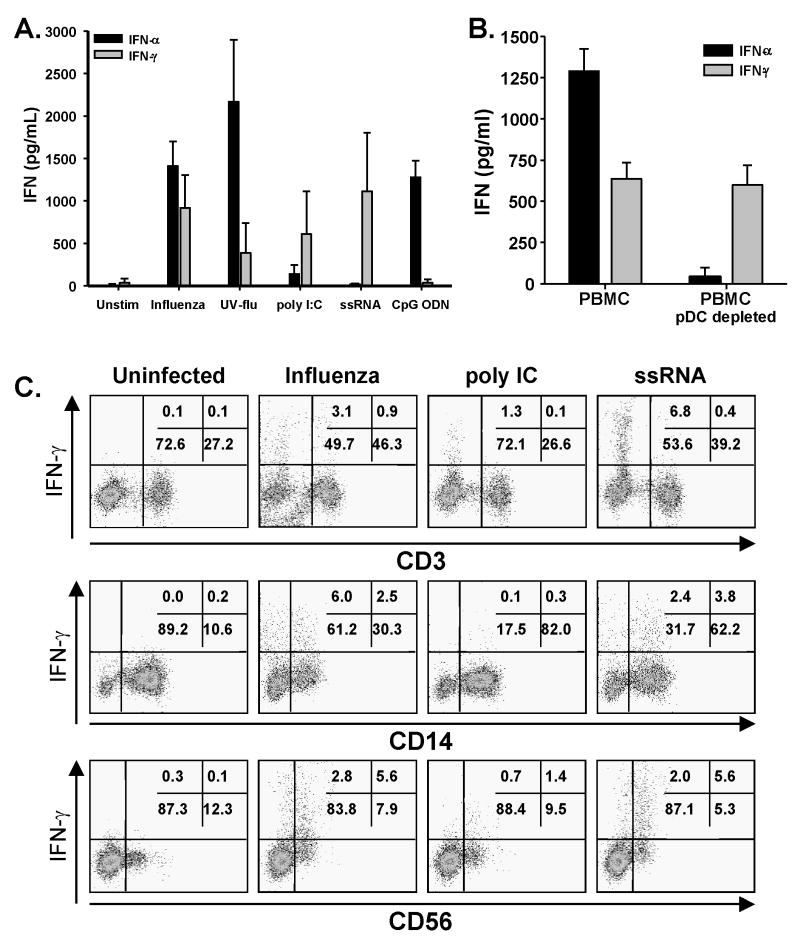

Influenza stimulates IFN-α and -γ production, which induces TRAIL expression on human PBMC

A large proportion of the signaling events in influenza-infected cells, be it epithelial cells or antigen presenting cells, is geared toward the generation of cellular responses designed to limit or prevent the spread of the invading virus in the tissue and the establishment of a persistent infection. The recognition of viral components, particularly the viral genetic material, directly triggers signaling pathways that induce IFN-α production [20, 29], as well as production of IFN-γ [21]. Thus, we measured the amount of IFN-α and -γ in the supernatants of PBMC stimulated with influenza or the TLR agonists used in Figures 1 and 2. Our analysis revealed that influenza-infected human PBMC produced ~1500 and 1000 pg/ml IFN-α and IFN-γ, respectively (Figure 4A). As predicted, CpG ODN-stimulated PBMC only produced IFN-α. Stimulation with ssRNA only led to measurable levels of IFN-γ, which is consistent with previous reports [32]. This lack of IFN-α production might be explained by the lack of TLR8 on plasmacytoid DC (pDC), which is the human TLR targeted by the ssRNA/LyoVec used. Stimulation of PBMC by poly I:C produced low, but measurable amounts of both IFN-α and –γ. All of these levels of IFN are well within the range of concentrations (100 ng/ml – 10 pg/ml) that induce TRAIL expression on human PBMC [23]. Plasmacytoid DC (pDC) are the predominant cell within the peripheral blood to produce type-I IFN [33–37]. Depletion of pDC significantly decreased the amount of IFN-α produced by PBMC after influenza virus infection (as well as CpG stimulation), but did not alter IFN-γ production, suggesting that pDC are the sole source of IFN-α after influenza virus stimulation (Figure 4B). Additionally, intracellular cytokine staining revealed that T cells, Mφ, and NK cells produced IFN-γ after influenza virus stimulation (Figure 4C). Together, these data demonstrate that influenza virus infection of PBMC stimulates multiple cell types to produce type I and II IFN.

Figure 4.

Influenza stimulates IFN-α and –γ production from PBMC. (A) PBMC were infected with viable or UV-inactivated influenza (UV-flu) or stimulated with the TLR agonists poly I:C, ssRNA, or CpG ODN. After 24 h, IFN-α and –γ levels were quantitated in the culture supernatant by ELISA. Cytokine levels represent the average amount measured from at least four independent experiments using different donors. (B) IFN-α is made by pDC within PBMC after influenza virus infection. PBMC or PBMC depleted of pDC were infected with influenza. After 24 h culture, IFN-α and –γ levels in the culture supernatants were then determined by ELISA. Results represent the average amount measured from 3 independent experiments using different donors. (C) IFN-γ expression by PBMC after influenza virus infection or TLR agonist stimulation. PBMC were infected with viable influenza or stimulated with the TLR agonists poly I:C or ssRNA. Intracellular IFN-γ levels were analyzed 24 h later in CD3+, CD14+, and CD56+ cells using two-color flow cytometry. Representative results are shown based on 104 gated cells in all conditions, and cell viability was >95%, as assessed by propidium iodide exclusion. Similar results were observed using at least 3 different PBMC donors.

Interferon stimulation, not direct infection, causes TRAIL upregulation

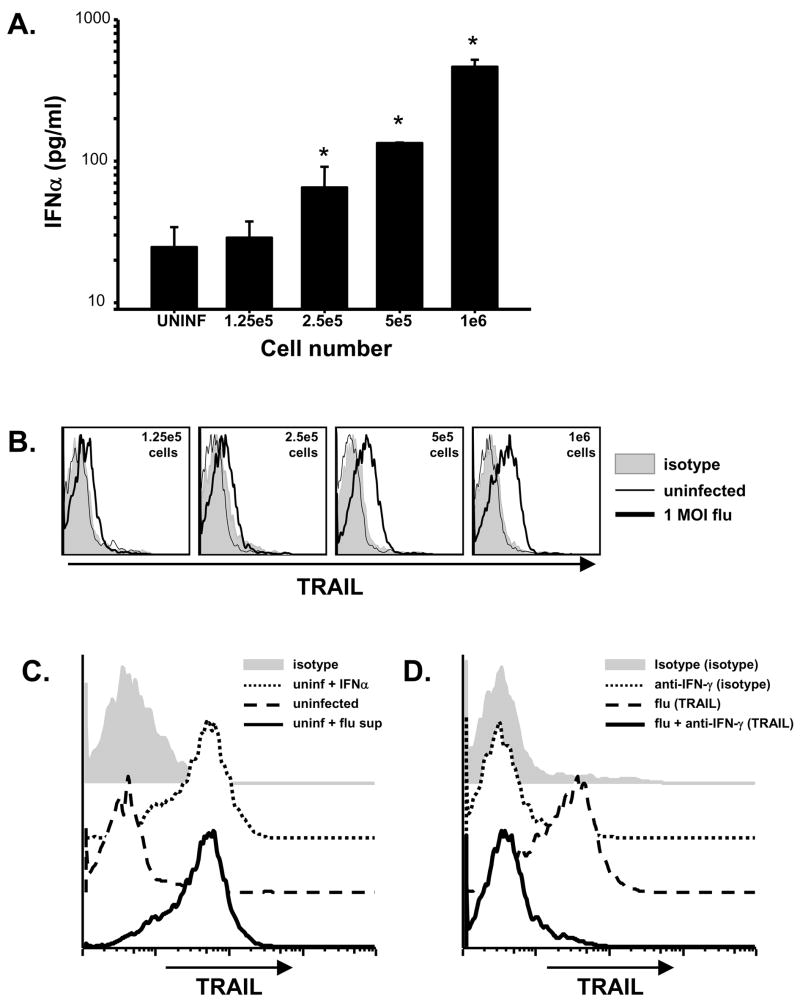

While the upreglation of TRAIL in response to stimulation by type I and II IFN has been widely described in tumor models [23, 25, 38], the mechanism of induction in viral systems has not been well-characterized. Examining the coexpression of TRAIL with NS1 demonstrated that a significant population of PBMC expressed TRAIL that did not have detectable levels of NS1 (Figure 3B), indicating direct infection was not necessary for TRAIL expression. To determine the relative importance of cytokine action on cells versus infection, PBMC were infected as described previously, but the infected cells were then split into cultures containing decreasing numbers of cells in an equivalent volume. As expected, diluting the number of cells in equivalent volumes of culture media caused a cell number-dependent decrease in IFN-α (Figure 5A) and IFN-γ (data not shown) detected in the cultures. Interestingly, the decreased IFN correlated with decreased TRAIL expression on the CD56+ populations (Figure 5B), as well as other PBMC populations (data not shown). To verify that TRAIL expression was driven by interferon stimulation in this experimental setting, supernatants from influenza-infected PBMC cultures were transferred to uninfected cells. As expected, transfer of supernatant from influenza-infected PBMC cultures lead to TRAIL upregulation by uninfected CD56+ cells (Figure 5C) as well as other PBMC populations (data not shown). To confirm the necessity of IFN to drive TRAIL expression, we infected pDC-depleted PBMC with influenza virus for 24 h, and then transferred the supernatant to uninfected PBMC. This conditioned media, as well as conditioned media containing an isotype mAb, also stimulated TRAIL expression (Figure 5D). In contrast, use of conditioned media treated with a neutralizing IFN-γ mAb prior to transfer failed to induce TRAIL expression. These data collectively demonstrate that the upregulation of TRAIL on influenza-infected PBMC is induced by IFN-α and IFN-γ signaling rather than the transfer of virus or direct infection of the cells.

Figure 5.

TRAIL induction is driven primarily by cytokines. (A) PBMC were infected with influenza. After infection, decreasing numbers of cells (106 – 1.25 × 105 cells) were aliquoted into 2 ml of media. After 24 h culture, IFN-α levels in the culture supernatants were determined by ELISA. Results represent the average amount measured from 2 independent experiments using different donors. * p < 0.05 compared to uninfected level. (B) After infection and 24 h culture (as described in 5A), PBMC from cell dilution cultures were analyzed for surface TRAIL expression on CD3+ cells using two-color flow cytometry. Representative results are shown in histograms based on at least 5 × 103 gated cells. Similar results were observed using 2 different PBMC donors. (C) After infection and 24 h culture (as described in 5A), supernatants from 106-cell PBMC cultures were transferred to uninfected cells from the same donor. After 24 h incubation, TRAIL expression on uninfected cells (uninfected), uninfected cells with supernatants from influenza-infected cells (Flu supe), or receiving media plus IFN-α (IFN-α) was determined. Representative results for CD3+ cells are shown in histograms based on at least 104 gated cells. Similar results were observed using 2 different PBMC donors. (D) PBMC were depleted of pDC, infected with influenza virus, and cultured for 24 h (as described in 5A). Supernatants from 106-cell cultures were incubated with an anti-IFN-γ neutralizing mAb, and then transferred to uninfected cells from the same donor. TRAIL expression on uninfected cells cultured with isotype or anti-IFN-γ mAb only, or in supernatants from influenza-infected cells treated with anti-IFN or isotype antibody. Representative results for CD3+ cells are shown in histograms based on at least 104 gated cells. Similar results were observed using 2 different PBMC donors.

Influenza-stimulated PBMC utilize TRAIL to kill influenza-infected lung cells, but not uninfected cells

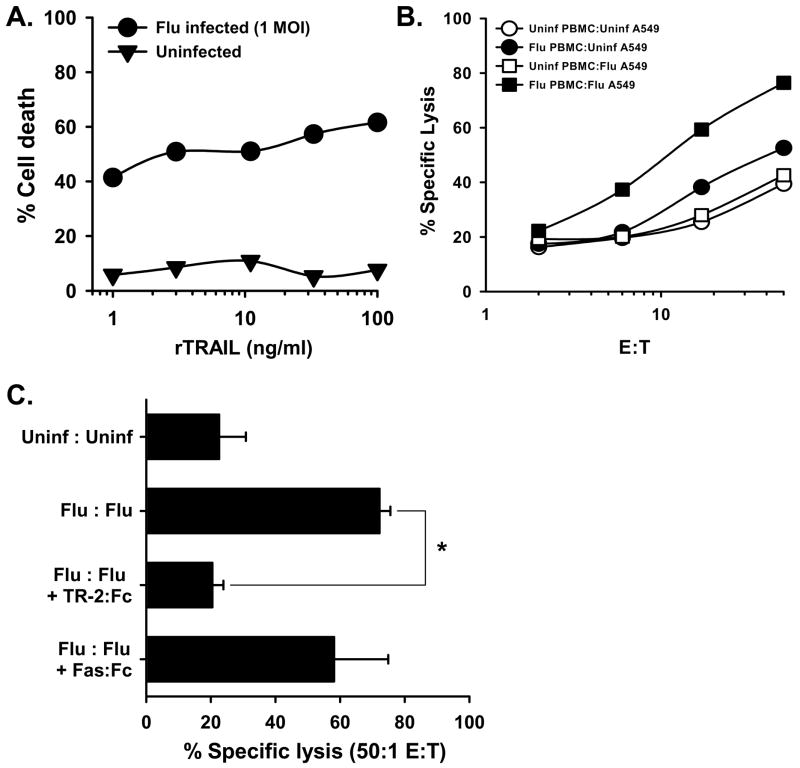

Epithelial cells derived from multiple organs can be sensitized to TRAIL-mediated apoptosis after viral infection. We hypothesized that TRAIL plays an important role in the elimination of influenza-infected lung epithelial cells, and the aforementioned results clearly demonstrate that influenza-stimulated PBMC gain TRAIL-mediated cytotoxic activity. Thus, the following experiments were performed to investigate the sensitization of influenza-infected human lung epithelial cells to TRAIL. We began our analysis by testing the responsiveness of the human lung adenocarcinoma cell line A549 to TRAIL before and after influenza virus infection. As previously reported, uninfected A549 were not readily killed by recombinant TRAIL [8], but the cells displayed a significant increase in sensitivity after influenza virus infection (Figure 6A). Next, we examined the ability of influenza-stimulated PBMC to kill influenza-infected A549. Uninfected target cells were killed at similar levels by both unstimulated and influenza-stimulated PBMC (Figure 6B). However, a significant increase in the lysis of infected target cells by influenza-stimulated PBMC was observed. Further analysis found that the addition of soluble TRAIL-R2:Fc blocked target cell lysis (Figure 6C), whereas the addition of Fas:Fc did not significantly inhibit killing, suggesting that TRAIL is the primary mechanism used by influenza-stimulated PBMC to kill influenza-infected target cells.

Figure 6.

Influenza virus infection alters cell sensitivity to TRAIL. (A) The lung adenocarcinoma cell line, A549, was infected with influenza (1 MOI) for 24 h. The cells were then added to 96-well microtiter plates (4 × 105 cells/well) and cultured with increasing concentrations of recombinant TRAIL (rTRAIL) at the indicated concentrations. Cell death was measured 24 h later. Uninfected A549 cells were tested at the same time. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments, where each data point is the average of 3 wells. (B) Influenza-infected PBMC readily kill influenza-infected A549 cells, but not uninfected A549 cells. PBMC were infected with influenza. After 24 h, the PBMC were harvested and cultured for 14 h with 51Cr-labeled uninfected or influenza-infected (1 MOI for 24 h) A549 target cells at the indicated effector-target cell ratios. (C) Inhibition of influenza-infected PBMC killing of influenza-infected A5499 target cells is blocked by TRAIL-R2:Fc (20 μg/ml), while Fas:Fc (20 μg/ml) did not significantly inhibit killing. The effector:target cells ratio was 50:1. Data points represent the mean of triplicate wells, and experiments were repeated at least three times using different donor PBMC with similar results. * p < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Each year in the United States, approximately 36,000 people die from influenza virus infection, and more than 200,000 people are hospitalized from influenza complications [39]. The World Health Organization estimates that ~5–15% of the entire global population are infected annually, with the elderly and very young most at risk for severe complications [40]. Influenza virus infection is immunogenic, stimulating cytotoxic T cells (CTL) to kill infected airway epithelial cells that are primary targets of the influenza virus, and the initial recognition of the viral infection by the innate immune system typically triggers an antiviral immune response. In particular, type I and type II IFN are the key cytokines produced after influenza virus infection that help activate the innate and adaptive immune responses [41]. Among the multitude of events that occur after IFN stimulation, the acquisition of effector molecules on/in various immune cells is vital for controlling influenza virus infection and eliminating infected cells. To our knowledge, our data show for the first time that human PBMC stimulated with influenza virus upregulate TRAIL, which can then be used to kill influenza-infected cells, thus expanding the number of known effector molecules used by human immune cells to deal with this infectious pathogen.

Influenza is a single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) virus that infects both the upper and lower respiratory tracts of humans. While various components of the viral coat are strong antigens that can be recognized by the adaptive immune system, the ssRNA of the influenza genome is also immunostimulatory and is what is initially recognized by the host pattern-recognition receptors that lead to the production of IFN [42]. TLR3, expressed in pulmonary epithelial cells, can also recognize the dsRNA intermediate produced during viral replication and mRNA synthesis [43–45], resulting in the production of a number of proinflammatory cytokines by bronchial epithelial cells. Additionally, recognition of ssRNA viral genome bearing a 5′ triphosphate end by the RNA helicase RIG-I also stimulates type I IFN production [46], which is similarly regulated by the influenza NS1 protein [47, 48]. The influenza virus NS1 protein binds to dsRNA and inhibits various antiviral pathways in infected cells [49]. Despite this, innate and adaptive immune cells can still respond to influenza by producing IFN-α through TLR7 recognition of ssRNA. Within the blood, pDC express TLR7, and secrete large amounts of IFN-α in response to viral infection [50]. The IFN-α produced by pDC upon viral stimulation is critical in the subsequent response of T cells, NK cells, and other DC to the virus.

Our results show that both IFN-α and –γ are produced by human PBMC after influenza virus infection. In our in vitro infection system, the pDC are the primary source of IFN-α, while T cells, monocytes, and NK cells are responsible for IFN-γ production. This observation is consistent with recent report underscoring the role of pDCs as the respiratory DC subset responsible for producing IFN-α and other cytokines in response to influenza virus infection [51]. Interestingly, these observations conflict with a recent study of IFN-α production after infection with RNA-viruses, which concluded that alveolar macrophages and conventional DC – but not pDC – are the primary producers of IFN-α in response to RNA-virus infection [52]. While Kumagai and colleagues convincingly demonstrated that pDC played a minimal role in IFN-α production to Newcastle disease virus and Sendai virus, their study did not examine the immune response to influenza virus. Taken together, these studies support the notion that immune responses to similar pathogens can be induced by unique mechanisms; further, they reinforce the need to determine the relative contributions of alveolar macrophages and DC subsets to IFN production during the in vivo immune response to influenza virus infection.

Among the multitude of IFN-responsive genes present in human PBMC, the induced expression of TRAIL on multiple cell types occurs rapidly. The human TRAIL promoter contains multiple transcriptional binding elements, including an IFN sensitive response element [22, 53]. Furthermore, human T cells, B cells, NK cells, Mφ, and DC all can be induced to express functional TRAIL by IFN (either type I or II IFN) [23–25, 31, 54]. We observed functional TRAIL expressed on multiple PBMC populations after influenza virus infection; further, these cells could kill influenza-infected target cells in vitro. This TRAIL expression is dependent on cytokine signaling, as cells given equivalent infections showed decreasing levels of TRAIL expression when cell number and cytokine levels were diluted. Given the past studies relating TRAIL expression to IFN stimulation and the data presented in this report, we can easily speculate that the type I and II IFN produced in response to influenza infection causes the TRAIL upregulation, and that many of the inflammatory cells responding to an influenza virus infection in the lungs will be induced to express TRAIL as they enter the IFN-rich pulmonary microenvironment or the draining lymph nodes where influenza antigens would be presented. Interestingly, animals infected with the pandemic 1918 influenza A virus showed aberrant IFN production and signaling [55] and disrupted expression of TRAIL message [56]. These observations, coupled with the dysregulated IFN responses observed in H5N1 infections [20, 57–59], suggest that altered IFN signaling and aberrant TRAIL upregulation during the immune response to highly pathogenic influenza strains might significantly contribute to the pathogenicity of these infections.

In addition to the Fas/FasL and perforin/Granzyme B pathways for killing, CD8+ T cells can also utilize a TRAIL/TRAIL receptor-dependent mechanism to induce apoptosis of infected cells during viral infections. TRAIL is upregulated on CD8+ T cells, CD4+ T cells, and NK cells following virus infection [7, 13, 19] or during inflammatory responses marked by increases of IFNγ or TNFα [13, 60]. TRAIL induces apoptotic cell death [14, 15, 61, 62] by recruiting and aggregating caspase 8 upon binding to either TRAIL-R1 or -R2 [62–65]. This aggregation in turn leads to a caspase cascade and eventually to apoptotic death of the TRAIL-R1/-R2-expressing cell [16, 62–64]. Many viruses have a significant impact on host cell metabolism; hence, it might be predicted that cells infected with viruses would acquire sensitivity to TRAIL. Indeed, normal cells upregulate TRAIL-R1 and –R2 expression after viral infection and become susceptible to TRAIL-mediated killing [8, 10, 13, 66]. IFN-γ and TNF also downregulate TRAIL receptor expression on uninfected cells [13]. These previous reports are consistent with our results demonstrating enhanced killing of influenza-infected cells relative to the killing of uninfected cells. Specifically, we found the TRAIL-resistant human lung adenocarcinoma cell line, A549, could be sensitized to TRAIL following influenza virus infection – much like that seen by Kotelkin et al. who showed that A549 could be rendered TRAIL sensitive after RSV infection [8].

Overall, our results demonstrate that TRAIL-induced apoptosis plays a key role in clearance of virus-infected cells. Understanding of the relative contributions of apoptosis-inducing ligands and other factors that determine the outcome of virus infection in vitro and in vivo will help design treatment strategies for highly-pathogenic viruses in which the balance of these contributions is disrupted. Interestingly, aberrant TRAIL signaling might contribute to viral pathology in highly-pathogenic infections [18]. Hence, treatment strategies of highly-pathogenic influenza viruses should seek to optimize TRAIL-induced viral clearance while minimizing the detrimental effects associated with highly-pathogenic infections.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine Collaborative Pilot Grant (KLL and TSG), the NIH (R21 AI072032; KLL), and a predoctoral fellowship from the American Heart Association (ELB).

References

- 1.Topham DJ, Tripp RA, Doherty PC. CD8+ T cells clear influenza virus by perforin or Fas-dependent processes. J Immunol. 1997;159:5197–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doherty PC. Cytotoxic T cell effector and memory function in viral immunity. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1996;206:1–14. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-85208-4_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lukacher AE, Braciale VL, Braciale TJ. In vivo effector function of influenza virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte clones is highly specific. J Exp Med. 1984;160:814–26. doi: 10.1084/jem.160.3.814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lawrence CW, Braciale TJ. Activation, differentiation, and migration of naive virus-specific CD8+ T cells during pulmonary influenza virus infection. J Immunol. 2004;173:1209–18. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lawrence CW, Ream RM, Braciale TJ. Frequency, specificity, and sites of expansion of CD8+ T cells during primary pulmonary influenza virus infection. J Immunol. 2005;174:5332–40. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.9.5332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Legge KL, Braciale TJ. Lymph node dendritic cells control CD8+ T cell responses through regulated FasL expression. Immunity. 2005;23:649–59. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clarke P, Meintzer SM, Gibson S, Widmann C, Garrington TP, Johnson GL, et al. Reovirus-induced apoptosis is mediated by TRAIL. J Virol. 2000;74:8135–9. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.17.8135-8139.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kotelkin A, Prikhod’ko EA, Cohen JI, Collins PL, Bukreyev A. Respiratory syncytial virus infection sensitizes cells to apoptosis mediated by tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand. J Virol. 2003;77:9156–72. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.17.9156-9172.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lund JM, Alexopoulou L, Sato A, Karow M, Adams NC, Gale NW, et al. Recognition of single-stranded RNA viruses by Toll-like receptor 7. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:5598–603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400937101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vidalain PO, Azocar O, Lamouille B, Astier A, Rabourdin-Combe C, Servet-Delprat C. Measles virus induces functional TRAIL production by human dendritic cells. J Virol. 2000;74:556–9. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.1.556-559.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Washburn B, Weigand MA, Grosse-Wilde A, Janke M, Stahl H, Rieser E, et al. TNF-Related Apoptosis-Inducing Ligand Mediates Tumoricidal Activity of Human Monocytes Stimulated by Newcastle Disease Virus. J Immunol. 2003;170:1814–21. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.4.1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zeng J, Fournier P, Schirrmacher V. Induction of interferon-alpha and tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand in human blood mononuclear cells by hemagglutinin-neuraminidase but not F protein of Newcastle disease virus. Virology. 2002;297:19–30. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sedger LM, Shows DM, Blanton RA, Peschon JJ, Goodwin RG, Cosman D, et al. IFN-gamma mediates a novel antiviral activity through dynamic modulation of TRAIL and TRAIL receptor expression. J Immunol. 1999;163:920–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pitti RM, Marsters SA, Ruppert S, Donahue CJ, Moore A, Ashkenazi A. Induction of apoptosis by Apo-2 ligand, a new member of the tumor necrosis factor cytokine family. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:12687–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.22.12687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wiley SR, Schooley K, Smolak PJ, Din WS, Huang CP, Nicholl JK, et al. Identification and characterization of a new member of the TNF family that induces apoptosis. Immunity. 1995;3:673–82. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90057-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Griffith TS, Lynch DH. TRAIL: a molecule with multiple receptors and control mechanisms. Curr Opin Immunol. 1998;10:559–63. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(98)80224-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaperot L, Blum A, Manches O, Lui G, Angel J, Molens JP, et al. Virus or TLR agonists induce TRAIL-mediated cytotoxic activity of plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2006;176:248–55. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.1.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou J, Law HK, Cheung CY, Ng IH, Peiris JS, Lau YL. Functional tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand production by avian influenza virus-infected macrophages. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:945–53. doi: 10.1086/500954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishikawa E, Nakazawa M, Yoshinari M, Minami M. Role of tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand in immune response to influenza virus infection in mice. J Virol. 2005;79:7658–63. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.12.7658-7663.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan MC, Cheung CY, Chui WH, Tsao SW, Nicholls JM, Chan YO, et al. Proinflammatory cytokine responses induced by influenza A (H5N1) viruses in primary human alveolar and bronchial epithelial cells. Respir Res. 2005;6:135. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-6-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Graham MB, Dalton DK, Giltinan D, Braciale VL, Stewart TA, Braciale TJ. Response to influenza infection in mice with a targeted disruption in the interferon gamma gene. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1725–32. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.5.1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Q, Ji Y, Wang X, Evers BM. Isolation and molecular characterization of the 5′-upstream region of the human TRAIL gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;276:466–71. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Griffith TS, Wiley SR, Kubin MZ, Sedger LM, Maliszewski CR, Fanger NA. Monocyte-mediated tumoricidal activity via the tumor necrosis factor-related cytokine, TRAIL. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1343–54. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.8.1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kayagaki N, Yamaguchi N, Nakayama M, Eto H, Okumura K, Yagita H. Type I interferons (IFNs) regulate tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) expression on human T cells: A novel mechanism for the antitumor effects of type I IFNs. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1451–60. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.9.1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zamai L, Ahmad M, Bennett IM, Azzoni L, Alnemri ES, Perussia B. Natural killer (NK) cell-mediated cytotoxicity: differential use of TRAIL and Fas ligand by immature and mature primary human NK cells. J Exp Med. 1998;88:2375–80. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.12.2375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Griffith TS, Chin WA, Jackson GC, Lynch DH, Kubin MZ. Intracellular regulation of TRAIL-induced apoptosis in human melanoma cells. J Immunol. 1998;161:2833–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Degli-Esposti MA, Smolak PJ, Walczak H, Waugh J, Huang C-P, DuBose RF, et al. Cloning and characterization of TRAIL-R3, a novel member of the emerging TRAIL receptor family. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1165–70. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.7.1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noppert SJ, Fitzgerald KA, Hertzog PJ. The role of type I interferons in TLR responses. Immunol Cell Biol. 2007;85:446–57. doi: 10.1038/sj.icb.7100099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thompson AJ, Locarnini SA. Toll-like receptors, RIG-I-like RNA helicases and the antiviral innate immune response. Immunol Cell Biol. 2007;85:435–45. doi: 10.1038/sj.icb.7100100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kemp TJ, Elzey BD, Griffith TS. Plasmacytoid dendritic cell-derived IFN-alpha induces TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand/Apo-2L-mediated antitumor activity by human monocytes following CpG oligodeoxynucleotide stimulation. J Immunol. 2003;171:212–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.1.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kemp TJ, Moore JM, Griffith TS. Human B Cells Express Functional TRAIL/Apo-2 Ligand after CpG-Containing Oligodeoxynucleotide Stimulation. J Immunol. 2004;173:892–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barchet W, Krug A, Cella M, Newby C, Fischer JA, Dzionek A, et al. Dendritic cells respond to influenza virus through TLR7- and PKR-independent pathways. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:236–42. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jarrossay D, Napolitani G, Colonna M, Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A. Specialization and complementarity in microbial molecule recognition by human myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:3388–93. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200111)31:11<3388::aid-immu3388>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hornung V, Rothenfusser S, Britsch S, Krug A, Jahrsdorfer B, Giese T, et al. Quantitative expression of toll-like receptor 1–10 mRNA in cellular subsets of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells and sensitivity to CpG oligodeoxynucleotides. J Immunol. 2002;168:4531–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krug A, Rothenfusser S, Hornung V, Jahrsdorfer B, Blackwell S, Ballas ZK, et al. Identification of CpG oligonucleotide sequences with high induction of IFN-alpha/beta in plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:2154–63. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200107)31:7<2154::aid-immu2154>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bauer M, Redecke V, Ellwart JW, Scherer B, Kremer JP, Wagner H, et al. Bacterial CpG-DNA triggers activation and maturation of human CD11c-, CD123+ dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2001;166:5000–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.8.5000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krug A, Towarowski A, Britsch S, Rothenfusser S, Hornung V, Bals R, et al. Toll-like receptor expression reveals CpG DNA as a unique microbial stimulus for plasmacytoid dendritic cells which synergizes with CD40 ligand to induce high amounts of IL-12. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:3026–37. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(2001010)31:10<3026::aid-immu3026>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kayagaki N, Yamaguchi N, Nakayama M, Kawasaki A, Akiba H, Okumura K, et al. Involvement of TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand in human CD4+ T cell-mediated cytotoxicity. J Immunol. 1999;162:2639–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.CDC: Fact Sheet: Kay facts about influenza and influenza vaccine. Department of Health and Human Services; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 40.WHO: Influenza. World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Katze MG, He Y, Gale JM. Viruses and interferon: A fight for supremacy. Nat rev Immunol. 2002;2:675–87. doi: 10.1038/nri888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kato H, Takeuchi O, Sato S, Yoneyama M, Yamamoto M, Matsui K, et al. Differential roles of MDA5 and RIG-I helicases in the recognition of RNA viruses. Nature. 2006;441:101–5. doi: 10.1038/nature04734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guillot L, Le Goffic R, Bloch S, Escriou N, Akira S, Chignard M, et al. Involvement of toll-like receptor 3 in the immune response of lung epithelial cells to double-stranded RNA and influenza A virus. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:5571–80. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410592200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li S, Min JY, Krug RM, Sen GC. Binding of the influenza A virus NS1 protein to PKR mediates the inhibition of its activation by either PACT or double-stranded RNA. Virology. 2006;349:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Min JY, Krug RM. The primary function of RNA binding by the influenza A virus NS1 protein in infected cells: Inhibiting the 2′-5′ oligo (A) synthetase/RNase L pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:7100–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602184103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Le Goffic R, Pothlichet J, Vitour D, Fujita T, Meurs E, Chignard M, et al. Cutting Edge: Influenza A virus activates TLR3-dependent inflammatory and RIG-I-dependent antiviral responses in human lung epithelial cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:3368–72. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.6.3368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mibayashi M, Martinez-Sobrido L, Loo YM, Cardenas WB, Gale M, Jr, Garcia-Sastre A. Inhibition of retinoic acid-inducible gene I-mediated induction of beta interferon by the NS1 protein of influenza A virus. J Virol. 2007;81:514–24. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01265-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Opitz B, Rejaibi A, Dauber B, Eckhard J, Vinzing M, Schmeck B, et al. IFNbeta induction by influenza A virus is mediated by RIG-I which is regulated by the viral NS1 protein. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:930–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cella M, Facchetti F, Lanzavecchia A, Colonna M. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells activated by influenza virus and CD40L drive a potent TH1 polarization. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:305–10. doi: 10.1038/79747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ito T, Wang YH, Liu YJ. Plasmacytoid dendritic cell precursors/type I interferon-producing cells sense viral infection by Toll-like receptor (TLR) 7 and TLR9. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 2005;26:221–29. doi: 10.1007/s00281-004-0180-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hao X, Kim TS, Brachiale TJ. Differential response of respiratory dendritic cell subsets to influenza virus infection. J Virol. 2008;82:4908–19. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02367-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kumagai Y, Takeuchi O, Kato H, Kumar H, Matsui K, Morii E, et al. Alveolar macrophages are the primary interferon-alpha producer in pulmonary infection with RNA viruses. Immunity. 2007;27:240–52. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gong B, Almasan A. Genomic organization and transcriptional regulation of human Apo2/TRAIL gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;278:747–52. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fanger NA, Maliszewski CR, Schooley K, Griffith TS. Human dendritic cells mediate cellular apoptosis via tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) J Exp Med. 1999;190:1155–64. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.8.1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kobasa D, Jones SM, Shinya K, Kash JC, Copps J, Ebihara H, et al. Aberrant innate immune response in lethal infection of macaques with the 1918 influenza virus. Nature. 2007;445:319–23. doi: 10.1038/nature05495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kash JC, Tumpey TM, Proll SC, Carter V, Perwitasari O, Thomas MJ, et al. Genomic analysis of increased host immune and cell death responses induced by 1918 influenza virus. Nature. 2006;443:578–81. doi: 10.1038/nature05181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hsieh SM, Chang SC. Insufficient perforin expression in CD8+ T cells in response to hemagglutinin from avian influenza (H5N1) virus. J Immunol. 2006;176:4530–3. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.8.4530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Seo SH, Hoffmann E, Webster RG. Lethal H5N1 influenza viruses escape host anti-viral cytokine responses. Nat Med. 2002;8:950–4. doi: 10.1038/nm757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tumpey TM, Lu X, Morken T, Zaki SR, Katz JM. Depletion of lymphocytes and diminished cytokine production in mice infected with a highly virulent influenza A (H5N1) virus isolated from humans. J Virol. 2000;74:6105–16. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.13.6105-6116.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Takeda K, Smyth MJ, Cretney E, Hayakawa Y, Yamaguchi N, Yagita H, et al. Involvement of tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand in NK cell-mediated and IFN-gamma-dependent suppression of subcutaneous tumor growth. Cell Immunol. 2001;214:194–200. doi: 10.1006/cimm.2001.1896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nagata S. Apoptosis by death factor. Cell. 1997;88:355–65. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81874-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ashkenazi A, Dixit VM. Death receptors: signaling and modulation. Science. 1998;281:1305–8. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sheridan JP, Marsters SA, Pitti RM, Gurney A, Skubatch M, Baldwin D, et al. Control of TRAIL-induced apoptosis by a family of signaling and decoy receptors. Science. 1997;277:818–21. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5327.818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Baize S, Kaplon J, Faure C, Pannetier D, Georges-Courbot MC, Deubel V. Lassa virus infection of human dendritic cells and macrophages is productive but fails to activate cells. J Immunol. 2004;172:2861–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.2861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wu GS, Burns TF, Zhan Y, Alnemri ES, El-Deiry WS. Molecular cloning and functional analysis of the mouse homologue of the KILLER/DR5 tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) death receptor. Cancer Res. 1999;59:2770–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sato K, Hida S, Takayanagi H, Yokochi T, Kayagaki N, Takeda K, et al. Antiviral response by natural killer cells through TRAIL gene induction by IFN-alpha/beta. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:3138–46. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200111)31:11<3138::aid-immu3138>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]