Abstract

The estrogen receptor (ER) subtypes, ERα and ERβ, modulate numerous signaling cascades in the brain to result in a variety of cell fates including neuronal differentiation. We report here that 17β-estradiol (E2) rapidly stimulates the autophosphorylation of α-Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II (αCaMKII) in immortalized NLT GnRH neurons, primary hippocampal neurons, and Cos7 cells co-transfected with ERα and αCaMKII. The E2-induced αCaMKII autophosphorylation is ERα-and Ca2+/calmodulin (CaM)-dependent. Interestingly, the hormone-dependent association of ERα with αCaMKII attenuates the positive effect of E2 on αCaMKII autophosphorylation, suggesting that ERα plays a complex role in modulating αCaMKII activity and may function to fine-tune αCaMKII-triggered signaling events. However, it appears as though the activating signal of E2 dominates the negative effect of ER since there is a clear, positive downstream response to E2-activated αCaMKII; pharmacological inhibitors and RNAi technology show that targets of ERα-mediated αCaMKII signaling include extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2), cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB), and microtubule associated protein 2 (MAP2). These findings suggest a novel model for the modulation of αCaMKII signaling by ERα, which provides a molecular link as to how E2 might influence brain function.

Classification term: Intracellular signal transduction

Keywords: rapid estrogen action, estrogen receptor, Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II, phosphorylation, signal transduction

Introduction

Estrogen is intimately involved in the development and regulation of a variety of tissues, including the brain where it functions as a potent neuroprotective agent (Tang, 1996; Slooter, 1999) and a positive influencer of mood and cognition in both humans and rodents (Duff, 2000; Ahokas, 2001; Estrada-Camarena, 2003; Sandstrom, 2004; Almeida, 2005). Specifically, estrogen replacement in ovariectomized female rats significantly improves spatial memory retention as tested by a delayed matching-to-place water maze task (Sandstrom, 2004), and examination of the ERα knock-out mouse model (ERαKO) demonstrated that ERα is required for learning hippocampal-dependent inhibitory avoidance tasks (Fugger, 2000). Clearly, a connection between estrogen and brain function exists, however, the underlying mechanisms are still an area of fierce investigation.

Estrogen influences cognition primarily by its rapid modulatory effects on multiple signaling pathways. The rapid effects of estrogen refer to those events that occur seconds to minutes after estrogen administration and are not sensitive to inhibitors of transcription or translation (Heldring, 2007). Wu (2005) as well as Zhao (2005) have shown that E2 induces Ca2+ influx in hippocampal neurons within seconds, initiating signaling cascades that result in varied neurotrophic responses including neurite outgrowth and neuroprotection. E2 also rapidly induces c-Src activation in explanted mouse cortical neurons to influence neuronal differentiation (Nethrapalli, 2001). CREB phosphorylation is stimulated by E2 through the activation of ERK1/2 in forebrain cholinergic neurons, which requires ERα but not ERβ (Szego, 2006). Additionally, Sawai (2002) reported that E2 induces αCaMKII activity in hippocampal neurons in an ICI-sensitive manner, implicating the involvement of ER; however, the mechanism was not addressed.

αCaMKII plays an essential role in neuronal differentiation and cognitive processes (Silva, 1992a; Blanquet, 1999; Gaudilliere, 2004), thus defining the relationship between E2 action and αCaMKII signaling is imperative for a better understanding of the mechanism by which E2 exerts its effects on the brain. αCaMKII is a multi-subunit serine/threonine kinase that is exquisitely responsive to Ca2+ levels (Hanson, 1992). Under basal conditions, αCaMKII is kept inactive by its autoinhibitory domain and only the binding of Ca2+/CaM to this domain disrupts autoinhibition, allowing for kinase activity. Autophosphorylation of αCaMKII at residue Thr286 occurs when the duration or magnitude of the Ca2+ signal increases and two neighboring kinase subunits bind Ca2+/CaM. This permits the activation of one subunit while the second subunit undergoes a conformational change, revealing Thr286 to the active subunit for phosphorylation. CaMKII remains actives until it is dephosphorylated, even when Ca2+ levels return to normal (Hanson, 1992; Hudmon, 2002).

In the present study, the hypothesis that CaMKII signaling is modulated by ER action is investigated. We show that E2 rapidly induces the autophosphorylation of αCaMKII in an ERα-and Ca2+ influx-dependent manner in transfected Cos7 cells, immortalized GnRH neurons, and primary hippocampal neurons. Interestingly, the physical interaction of ERα with αCaMKII counteracts the positive effect of E2 on αCaMKII activity suggesting a dual role for ERα in modulating αCaMKII function. Ultimately, the E2-evoked αCaMKII activity results in ERK1/2, CREB, and MAP2 phosphorylation in primary hippocampal neurons.

Results

E2 rapidly induces αCaMKII autophosphorylation in the cytoplasm of NLT cells via a Ca2+-dependent mechanism

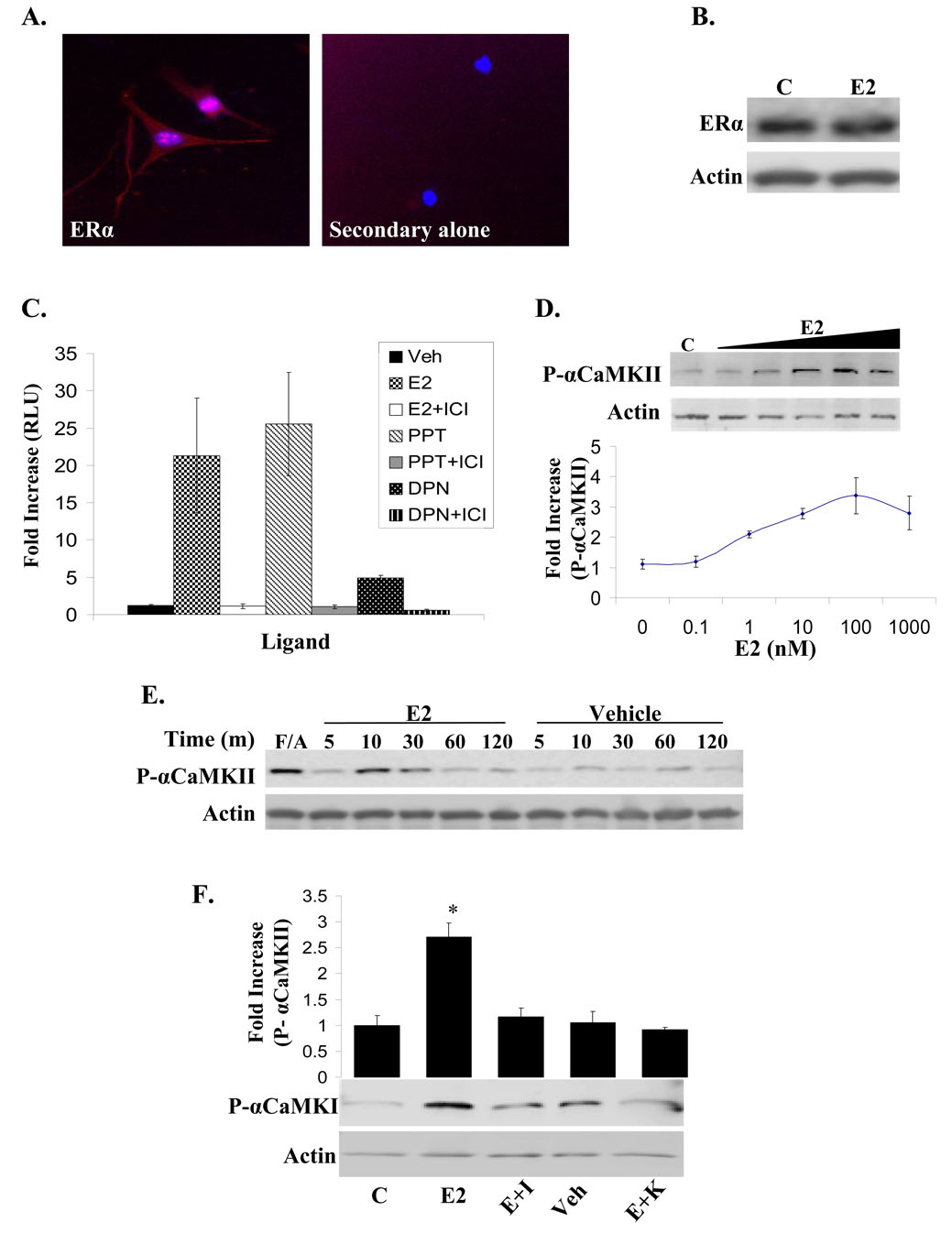

To examine the effect of E2 on αCaMKII activation it was first established that ERα is expressed in NLT immortalized GnRH neurons via immunofluorescence (Fig. 1A) and western blot analysis (Fig. 1B). Additionally, a luciferase reporter assay in which an estrogen response element (ERE) is linked to luciferase (3ERE-Luc) shows that NLT cells transfected with the 3ERE-Luc reporter plasmid have significantly increased luciferase activity when treated with either E2, propyl pyrazole triol (PPT: ERα-selective agonist), or diarylpropionitrile (DPN: ERβ-selective agonist) but not with vehicle or in the presence of ICI 182, 780 (ICI: potent ERα/β antagonist), confirming that NLT cells express functional ERα and ERβ (Fig. 1C). Treatment of NLT cells with increasing concentrations of E2 results in a dose-dependent increase of αCaMKII autophosphorylation (Fig. 1D), and subsequent experiments were performed using a 10nM concentration of E2 unless otherwise stated. The autophosphorylation of αCaMKII was also examined over time, and the peak of E2-induced kinase autophosphorylation occurs at 10 min of treatment. As a positive control a combination of forskolin and A23187 (F/A) was used to ultimately increase intracellular Ca2+ levels (Fig. 1E). This effect is blocked by pre-treatment with KN-62, a CaMKII-specific inhibitor, or ICI as shown by Western blot analysis (Fig. 1F).

Figure 1. NLT cells express functional ERα and ERβ and E2 rapidly induces the autophosphorylation of αCaMKII.

(A) Unstimulated NLT cells were co-stained for ERα (red) and DAPI (blue). Left panel: immunofluorescence performed with primary antibody (MC-20). Right panel: immunofluorescence performed in the absence of primary antibody (B) NLT cells were either unstimulated (C) or treated for 10 min with E2 (10nM), and immunoblotting detected total ERα and pan-Actin. (C) NLT cells were transfected with 3ERE-Luc and β-galactosidase, treated with vehicle (Veh; 0.01% EtOH), E2 (10nM), E2+ICI (10nM, 1uM), PPT (100nM), PPT+ICI (100nM, 1uM), DPN (100nM), or DPN+ICI (100nM, 1uM) for 24 hr, and assayed for both luciferase and β-galactosidase activity. Luciferase activity was normalized for transfection using β-galactosidase and represented as fold increase RLU (relative light units) over vehicle-treated cells. (D) NLT cells were either unstimulated (C) or treated with increasing concentrations of E2 (0.1nM–1000nM) for 10 min, and autophosphorylated αCaMKII and pan-Actin levels were detected by immunoblotting. Representative blot. (E) NLT cells were treated with forskolin and A23187 (F/A) for 2 min and 20 min, respectively, as a positive control, or with E2 (10nM) or vehicle (0.01% EtOH) for the indicated times. Immunoblotting detected autophosphorylated αCaMKII and pan-Actin. (F) NLT cells were either unstimulated (C) or treated with vehicle (Veh; 0.01% EtOH), E2 (10nM), E2+ICI (E+I; 10nM, 1uM), or E2+KN-62 (E+K; 10nM, 10uM) for 10 min. ICI and KN-62 were applied 30 min prior to E2 treatment. Immunoblotting detected autophosphorylated αCaMKII and pan-Actin. Representative blot. Densitometry for phosphorylated kinase was normalized to total protein levels for 3 independent experiments, and presented as the mean fold increase over unstimulated control ± S.D. (*) p < 0.01, E2 relative to other treatment conditions.

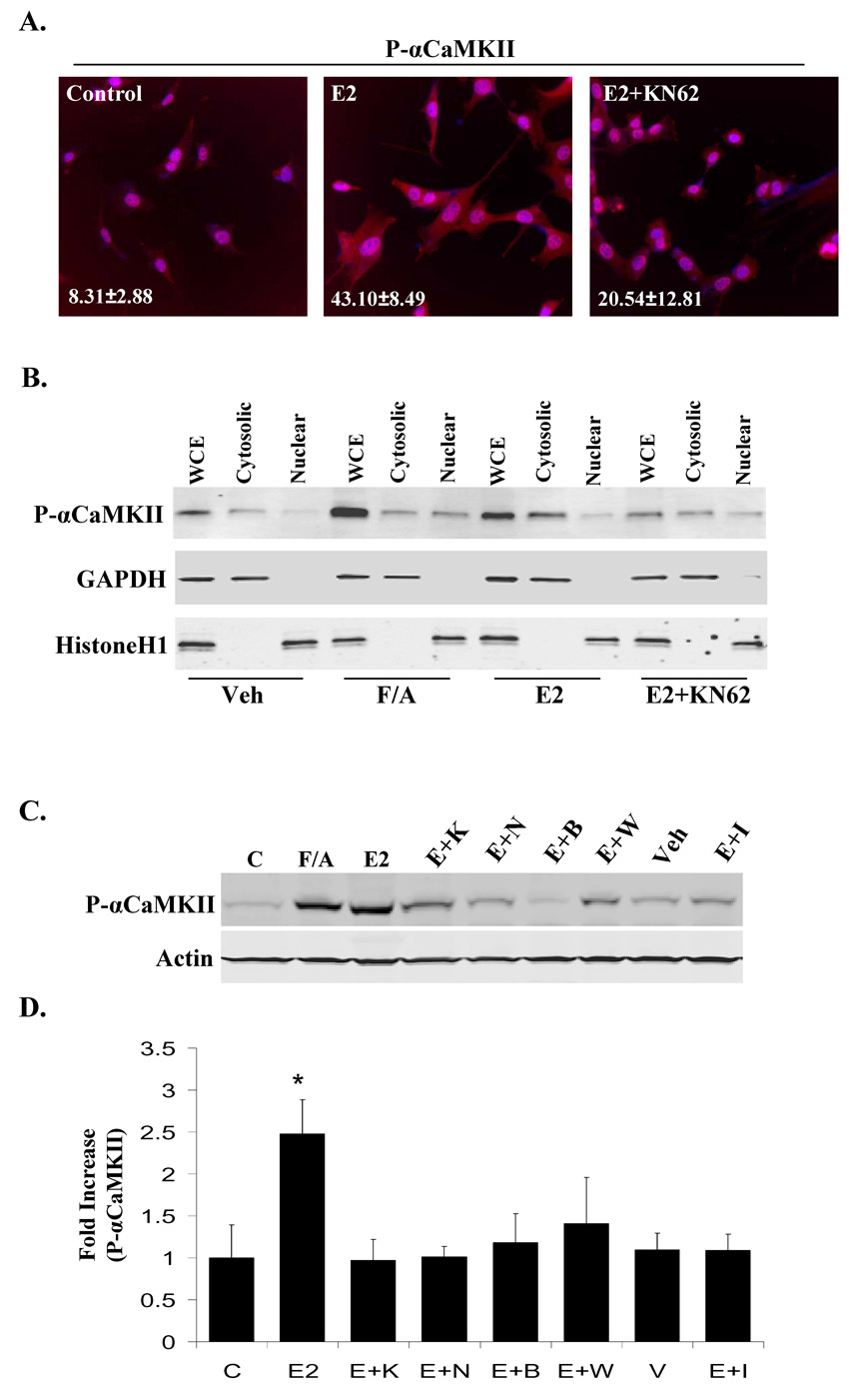

Immunofluorescence studies demonstrates that in NLT cells, E2 stimulates αCaMKII activation in the cytoplasm and cell outgrowths within 10 min compared to unstimulated cells, and KN-62 pre-treatment counteracts the E2 effect (Fig. 2A). Specifically, E2 induces kinase autophosphorylation in 43.10±8.49% of cells, whereas only 8.31±2.88% of unstimulated cells and 20.54±12.81% of E2+KN-62-treated cells have autophosphorylated αCaMKII in the cytoplasm. In contrast, the nuclear pool of αCaMKII in NLT cells appears to be activated regardless of the treatment. Fractionation of NLT cells after 10 min of ligand treatment confirmed that E2-induced αCaMKII autophosphorylation occurs primarily in the cytosolic fraction, which is considerably decreased by KN-62 (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. E2-induced αCaMKII autophosphorylation occurs in the cytoplasm and cell extensions of NLT cells in a Ca2+/CaM-dependent manner.

(A) Cells were either unstimulated (C) or treated with E2 (10nM) or E2+KN-62 pre-treatment (10nM, 10uM) for 10 min and then stained for autophosphorylated αCaMKII (red) and DAPI (blue) to visualize localization of kinase activation. (B) Whole cell extract (WCE), cytosolic, and nuclear fractions were obtained from NLT cells treated with vehicle (Veh; 0.01%EtOH), F/A (0.5mM, 50uM), E2 (10nM), or E2+KN-62 30 min pre-treatment (10nM, 10uM), and analyzed by immunoblotting for autophosphorylated αCaMKII, GAPDH (cytosolic protein), and Histone H1 (nuclear protein). (C) NLT cells were either unstimulated (C) or treated for 10 min with Veh (0.01%EtOH), F/A (0.5mM, 50uM), E2 (10nM), or E2 (10nM) with 30 min pre-treatment of KN-62 (E+K; 10uM), Nifedipine (E+Nif; 10uM), BAPTA-AM (E+B; 10uM), W7 (E+W; 10uM), or ICI (E+I; 1uM). Representative blot. (D) Autophosphorylated αCaMKII was normalized to total protein levels from 3 independent experiments and presented as the mean fold increase over unstimulated control ± S.D. (*) p < 0.03, E2 relative to other treatment conditions.

To begin to understand the mechanism by which E2 influences αCaMKII autophosphorylation we examined the hypothesis that Ca2+ signaling is involved since E2 rapidly triggers Ca2+ influx and mobilization in neuronal cells (Wu, 2005; Zhao, 2005). NLT cells were either unstimulated or treated for 10 min with vehicle, E2 alone, or E2 with 30 min pre-treatment of BAPTA-AM (intracellular Ca2+ chelator), W7 (CaM inhibitor), or Nifedipine (L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channel antagonist) (Fig. 2C/D). Western blot analysis demonstrates that E2-induced αCaMKII autophosphorylation is dependent on both intracellular Ca2+ and CaM action as it is completely blocked by BAPTA-AM and W7 pre-treatment. Ca2+ influx through L-type Ca2+ channels is also clearly involved as Nifedipine significantly decreases αCaMKII autophosphorylation induced by E2. Treatment with BAPTA-AM, W7, and Nifedipine alone had no effect on αCaMKII autophosphorylation (data not shown). These data suggest that E2-induced αCaMKII autophosphorylation is the result of Ca2+ influx via L-type Ca2+ channels, which can then complex with CaM to stimulate αCaMKII activity.

ERα and not ERβ is responsible for E2-induced αCaMKII activity

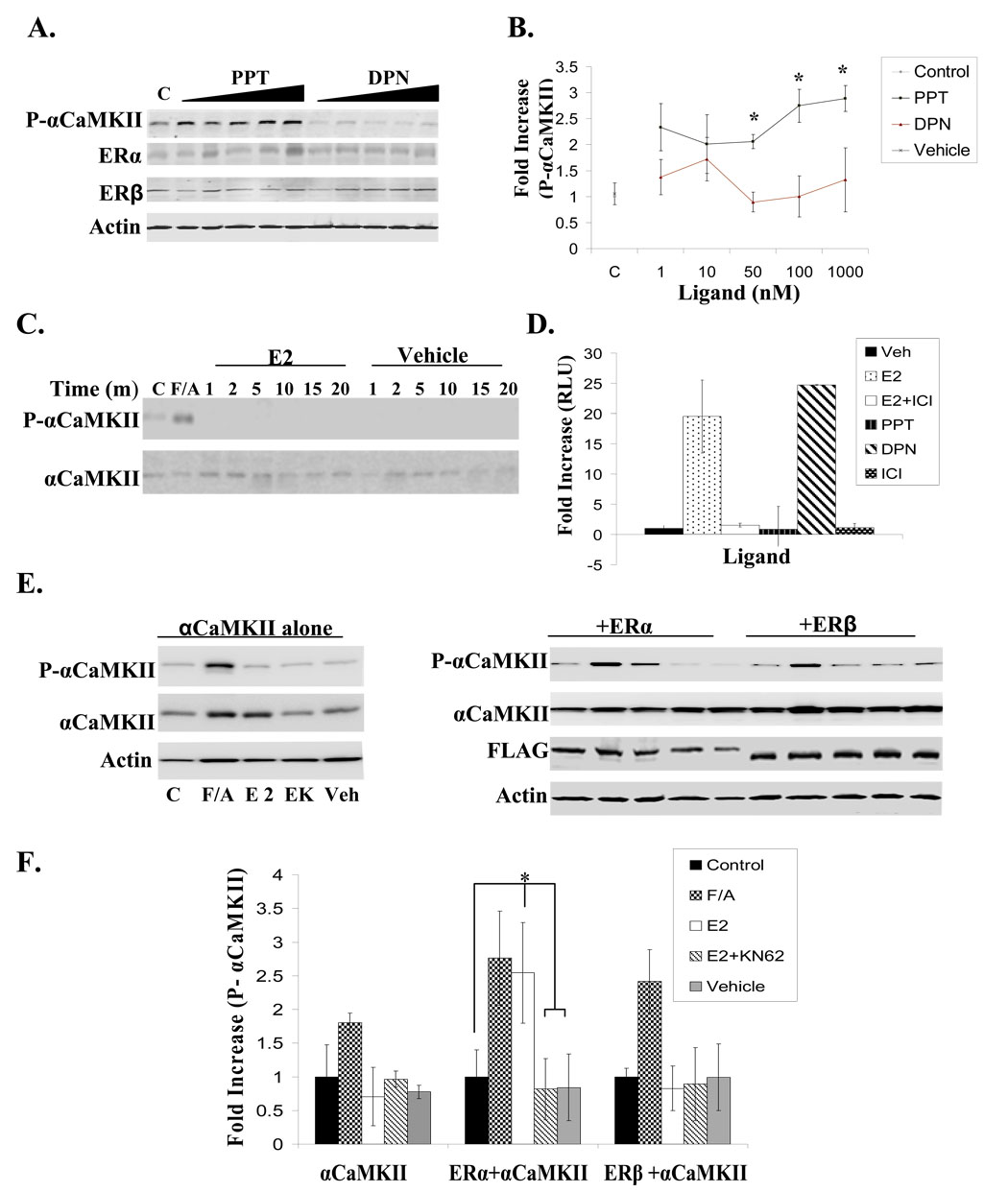

As both ERα and ERβ are expressed in a variety of brain regions (Shughrue, 1997) and in NLT cells (Fig. 1C), it is important to understand if one or both of them could be involved in stimulating αCaMKII autophosphorylation. To address this issue, the effect of two ER-selective ligands, PPT (ERα-selective agonist) and DPN (ERβ-selective agonist), was examined.

Increasing concentrations of the receptor-selective ligands were applied to NLT cells for 10 min, and while PPT is able to induce αCaMKII autophosphorylation in a dose-dependent manner, DPN is unable to elicit the same response even though the levels of ERα and ERβ are relatively similar (Fig. 3A/B). These results suggest that ERβ, while transcriptionally active, does not appear to mediate αCaMKII autophosphorylation in these cells. Additionally, E2 treatment is unable to induce αCaMKII autophosphorylation at any of the time points examined in a neuroblastoma cell line (SK-N-SH) (Fig. 3C) shown to be devoid of ERα but express functional ERβ as evidenced by luciferase assay (Fig. 3D), which is in agreement with previous reports (Ba, 2004; Wen, 2004). Additionally, Cos7 cells transfected with αCaMKII alone or in the presence of either ERα or ERβ, and then treated with E2 confirmed the involvement of ERα. The co-expression of ERα but not ERβ with αCaMKII results in increased kinase autophosphorylation within just 2 min of E2 treatment. This effect is blocked by pre-treatment with KN-62 and is non-existent in the presence of vehicle. In the absence of ERα, E2 is unable to stimulate αCaMKII activity (Fig. 2E/F). These results indicate that ERα mediates the activation of αCaMKII by E2, and ERβ is not involved in the examined cellular contexts.

Figure 3. ERα and not ERβ mediates αCaMKII autophosphorylation.

(A) NLT cells were either unstimulated (C) or treated with Veh (0.01%EtOH) or increasing concentrations of PPT or DPN (1nM–1000nM) for 10 min. Immunoblotting was used to detect autophosphorylated αCaMKII, ERα, ERβ, and pan-Actin levels. Representative blot. (B) Densitometry analysis for phosphorylated kinase was normalized to total protein levels from 3 independent experiments, and presented as the mean fold increase over unstimulated control ± S.D. (*) p < 0.02. (C) SK-N-SH cells were treated with Veh (0.01%EtOH), F/A (0.5mM, 50uM), or E2 (10nM) for the times indicated and immunoblotting was used to detect total and autophosphorylated αCaMKII. (D) SK-N-SH cells were transfected with 3ERE-Luc and β-galactosidase, treated with Veh (0.01% EtOH), E2 (10nM), E2+ICI (10nM, 1uM), PPT (100nM), DPN (100nM), or ICI (1uM) for 24 hours, and assayed for both luciferase and β-galactosidase activity. Luciferase activity was normalized for transfection using β-galactosidase and represented as fold increase RLU over vehicle-treated cells. (E) Cos7 cells co-transfected with αCaMKII and either ERα or ERβ were unstimulated (C) or treated with Veh (0.01%EtOH), F/A (0.5mM, 50uM), E2 (10nM), or E2+KN-62 pre-treatment (E+K; 10nM, 10uM) for 2 min and then subjected to immunoblotting to detect autophosphorylated αCaMKII, total αCaMKII, FLAG-tagged ERα or ERβ, and pan Actin. Representative blot. (F) Densitometry analysis for phosphorylated kinase was normalized to total protein levels for 3 independent experiments, and presented as the mean fold increase over unstimulated control ± S.D. (*) p < 0.02.

ERα interacts with αCaMKII in a hormone-dependent manner to attenuate E2-induced αCaMKII autophosphorylation

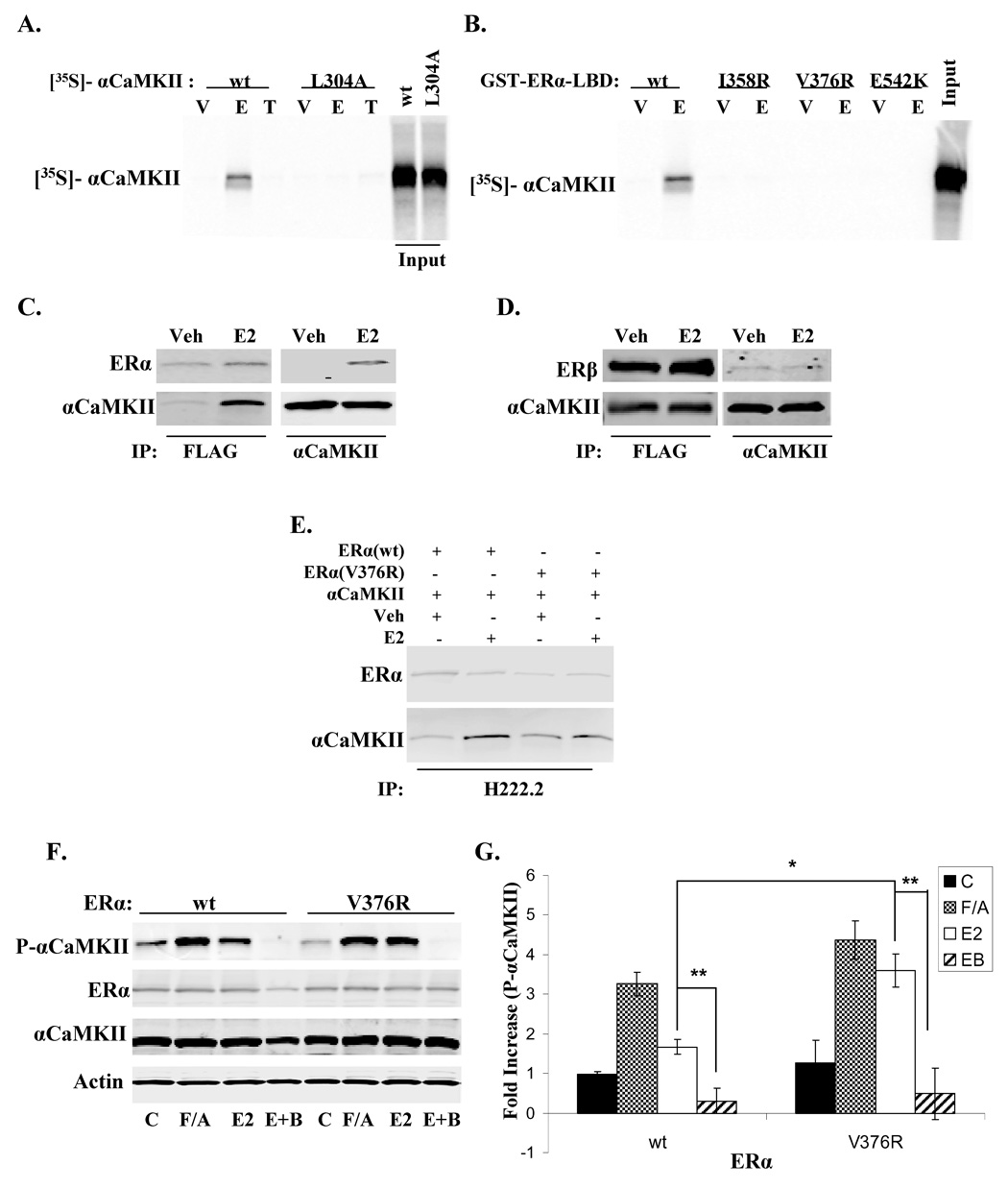

Examination of the αCaMKII amino acid sequence reveals that it contains a nuclear receptor interaction motif, or NR box, within the CaM-binding region of the autoinhibitory domain. If αCaMKII can interact with ERα via this NR box, an LTTML sequence, mutation of the consensus sequence should impair the association. GST pulldown studies show that when the NR box of αCaMKII is disrupted by the mutation L304A, the E2-dependent interaction observed between wild type αCaMKII and GST-ERα-LBD (ligand binding domain) is completely abolished (Fig. 4A). To understand if the kinase binds to ER in a manner similar to that of a typical nuclear receptor coactivator, the ability of αCaMKII to bind various GST-ERα-LBD mutants was examined. It was previously reported that an array of point mutations in the ERα-LBD (ERα-I358R, V376R, and E542K) disrupt the binding of the glucocorticoid receptor interacting protein (GRIP) and steroid receptor coactivator 1 (SRC-1) to the hydrophobic binding pocket of ERα (Feng, 1998). Interestingly, αCaMKII is unable to bind any of the GST-ERα-LBD mutants even in the presence of E2, suggesting that αCaMKII binds to the same hydrophobic pocket as other typical coactivator proteins (Fig. 4B). Additionally, no association is observed in the presence of tamoxifen (T) in Figure 4A because this ligand induces the antagonist conformation of ERα-LBD, thus inhibiting αCaMKII binding.

Figure 4. ERα interacts with αCaMKII in a hormone-dependent manner to attenuate E2-induced αCaMKII activity.

(A) GST-ERα-LBD pulldown of [35S]-αCaMKII (wild-type and L304A). See materials and methods for details. V = vehicle, 1% EtOH; E = E2, 1uM; T = 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen, 1uM. Bound αCaMKII was visualized by autoradiography. (B) GST-ERα-LBD pulldown of wild-type [35S]-αCaMKII using wild type GST-ERα-LBD or GST-ERα- I358R, GST-ERα-V376R, or GST-ERα-E542K. V = vehicle, 1% EtOH; E = E2, 1uM. Bound αCaMKII was visualized by autoradiography. (C) Cos7 cells were co-transfected with FLAG-ERα and αCaMKII, treated with Veh (0.01%EtOH) or E2 (10nM) for 10 min, and ERα and αCaMKII were immunoprecipitated with either anti-FLAG or anti-αCaMKII, respectively. Immunoblotting was used to detect ERα and αCaMKII. (D) Cos7 cells were co-transfected with FLAG-ERβ and αCaMKII, treated with Veh (0.01%EtOH) or E2 (10nM) for 10 min, and ERβ and αCaMKII were immunoprecipitated with either anti-FLAG or anti-αCaMKII, respectively. Immunoblotting was used to detect ERβ and αCaMKII. (E) Cos7 cells were co-transfected with αCaMKII and either wild type ERα or the interaction mutant ERα (V376R), treated with Veh (0.01%EtOH) or E2 (10nM) for 10 min, and ERα was immunoprecipitated with H222.2. Immunoblotting was used to detect ERα and αCaMKII. (F) Cos7 cells were co-transfected with αCaMKII and either wild-type ERα or the interaction mutant ERα (V376R), treated with F/A (0.5mM, 50uM), E2 (10nM), E2+BAPTA-AM pre-treatment (E+B; 10nM, 10uM) for 2 min, or left unstimulated (C). Immunoblotting detected autophosphorylated αCaMKII, total αCaMKII, ERα, and pan-Actin. Representative blot. (G) Density values for autophosphorylated αCaMKII were normalized to total protein levels for 3 independent experiments, and presented as the mean fold increase over unstimulated control ± S.D. (*) p < 0.03, (**) p < 0.02.

To test if the two proteins interact in cells, Cos7 cells were co-transfected with FLAG-ERα and αCaMKII, and the proteins were then immunoprecipitated with either anti-FLAG or anti-αCaMKII, respectively. Western blot analysis for ERα and αCaMKII shows that the proteins associate only in cells treated with E2 but not vehicle for 10 min (Fig. 4C). To determine if the interaction with αCaMKII was selective for ERα over ERβ, Cos7 cells were co-transfected with FLAG-ERβ and αCaMKII, and the proteins were immunoprecipitated with either anti-FLAG or anti-αCaMKII, respectively. Interestingly, in this context, ERβ associates with αCaMKII in a hormone-independent fashion as the interaction occurs in the presence of either vehicle or E2 (Fig. 4D). To confirm that the ERα-LBD mutant, V376R, is incapable of interacting with αCaMKII as demonstrated by GST pulldown experiments, Cos7 cells were co-transfected with αCaMKII and either wild-type ERα or ERα-V376R, and ERα was then immunoprecipitated with the ER-specific antibody, H222.2. Expectedly, the mutation of V376R effectively disrupted the E2-dependent interaction between αCaMKII and ERα in cells (Fig. 4E).

Although data in Figure 2C provides evidence that E2-induced αCaMKII autophosphorylation is dependent on Ca2+ signaling, it is fair to hypothesize that αCaMKII could also be directly activated by ERα through its interaction with the autoinhibitory region of the kinase, which could potentially disrupt its autoinhibition much in the same manner as calmodulin. To test this hypothesis, Cos7 cells were co-transfected with αCaMKII and either wild type ERα or the interaction mutant, ERα-V376R. The cells were unstimulated or treated with E2, or E2+BAPTA-AM pre-treatment, and αCaMKII autophosphorylation was detected by western blot analysis (Fig. 4F/G). Surprisingly, disrupting the interaction of ERα with αCaMKII significantly enhances the ability of E2 to stimulate kinase autophosphorylation (V376R expression versus wild-type expression: ~4-fold increase versus ~2-fold increase in autophosphorylation). Additionally, pre-treatment with BAPTA-AM abolishes E2-induced αCaMKII autophosphorylation when the ERα-αCaMKII interaction is disrupted, implying that E2 can still influence Ca2+ signaling to activate αCaMKII even when its interaction with ERα is impaired. Since the ERα binding site overlaps with the CaM-binding site, these data suggest the possibility that ERα may compete with Ca2+/CaM binding on αCaMKII and decrease its kinase activity, perhaps by locking the kinase subunits in an autoinhibited state. Taken together, these data show that while E2 can stimulate αCaMKII autophosphorylation via Ca2+ influx, the association of ERα with αCaMKII negatively regulates this event, perhaps to keep the amount of active kinase in check.

E2 stimulates ERK1/2 and CREB phosphorylation via a CaMKII-and L-type Ca2+ channel-dependent mechanism in NLT neurons

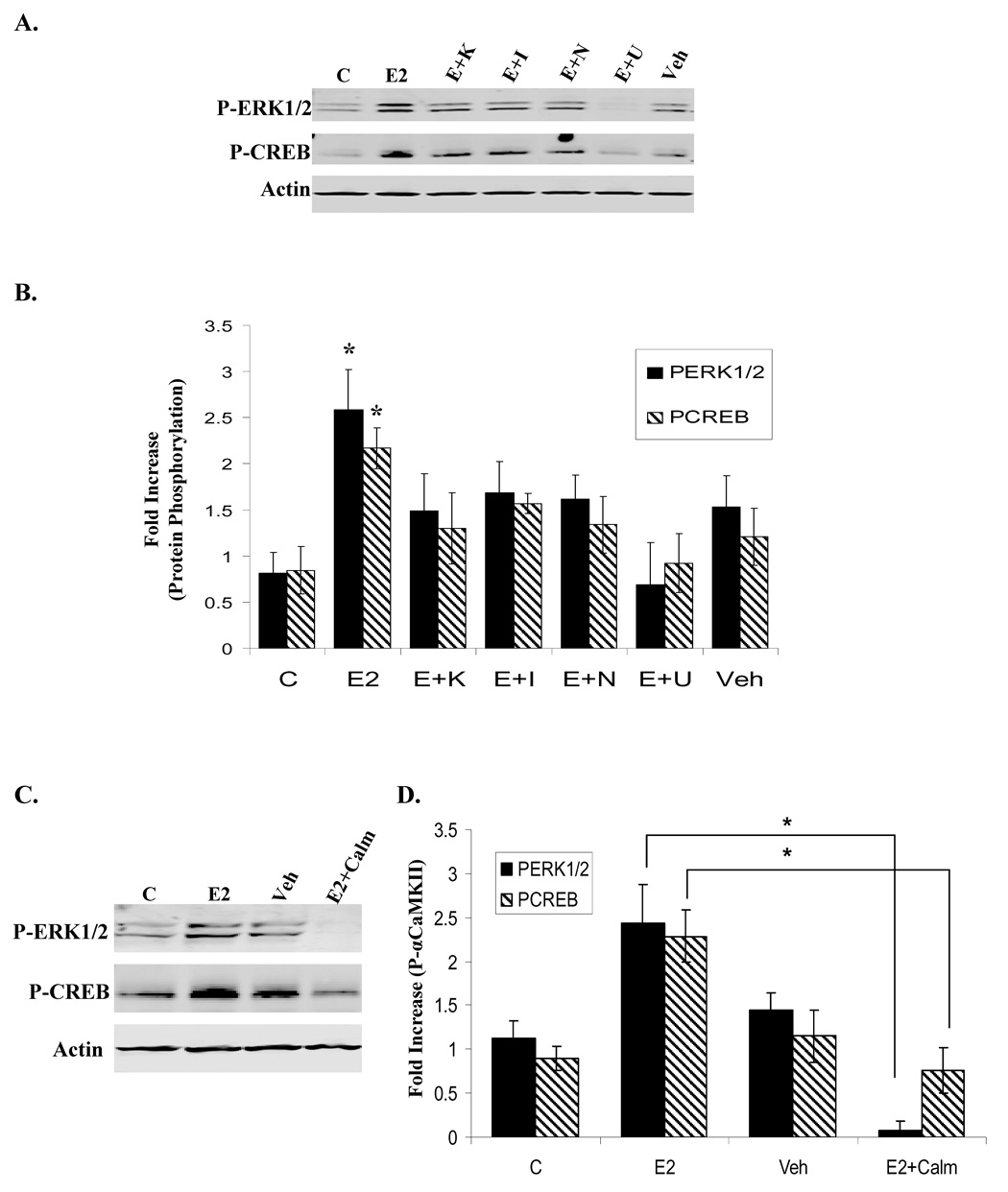

ERK1/2 and CREB have both been shown to play a role in neuronal survival, differentiation, and LTP depending on the stimuli (Winder, 1999; Piiper, 2002; Song, 2005). Furthermore, E2 has been reported to stimulate their activation in various populations of neurons (Lee, 2004; Szego, 2006), although the role of αCaMKII in this activation has not been thoroughly investigated. To examine the effect of E2-induced αCaMKII activity on ERK1/2 and CREB phosphorylation, NLT cells were either unstimulated or treated for 10 min with vehicle, E2, or E2 plus 30 min pretreatment with KN-62, ICI, Nifedipine, or U0126, a commonly used inhibitor of ERK1/2 activity. Western blot analysis shows that E2 treatment rapidly and significantly stimulates ERK1/2 and CREB phosphorylation over control and vehicle-treated cells. This effect is blocked by the inhibition of CaMKII and L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, confirming the involvement of both proteins (Fig. 5A/B). E2-stimulated CREB activity is also decreased by blocking ERK1/2 signaling with U0126, indicating that ERK1/2 is upstream of CREB. The involvement of CaM was also examined and 30 min pre-treatment of NLT cells with calmidazolium (Calm), a potent CaM inhibitor, prior to 10 min of E2 completely blocks the effect of E2 on ERK1/2 and CREB phosphorylation (Fig. 5C/D), revealing that CaM action is, in fact, important for E2-induced ERK1/2 and CREB activation.

Figure 5. αCaMKII and Ca2+/CaM signaling are involved in E2-induced ERK1/2 and CREB phosphorylation.

(A) NLT cells were either unstimulated (C) or treated for 10 min with Veh (0.01% EtOH), E2 (10nM), or E2 (10nM) with 30 min pre-treatment of KN-62 (E+K; 10uM), ICI (E+I; 1uM), Nifedipine (E+N; 10uM), or U0126 (E+U; 10uM). Immunoblotting detected phosphorylated levels of ERK1/2 and CREB as well as pan-Actin. Representative blot. (B) Densitometry analysis for phosphorylated kinase was normalized to total protein levels for 3 independent experiments, and presented as the mean fold increase over unstimulated control ± S.D. (*) p<0.03, E2 compared to all other conditions. (C) NLT cells were either unstimulated (C) or treated for 10 min with Veh (0.01% EtOH), E2 (10nM), or E2 (10nM) with 30 min pretreatment of calmidazolium (E+Calm; 10uM). Immunoblotting detected phosphorylated ERK1/2 and CREB, and pan-Actin. Representative blot. (D) Densitometry for phosphorylated kinase was normalized to total protein levels, and presented as the mean fold increase over unstimulated control ± S.D. (*) p < 0.02.

E2-induced αCaMKII signaling in primary hippocampal neurons

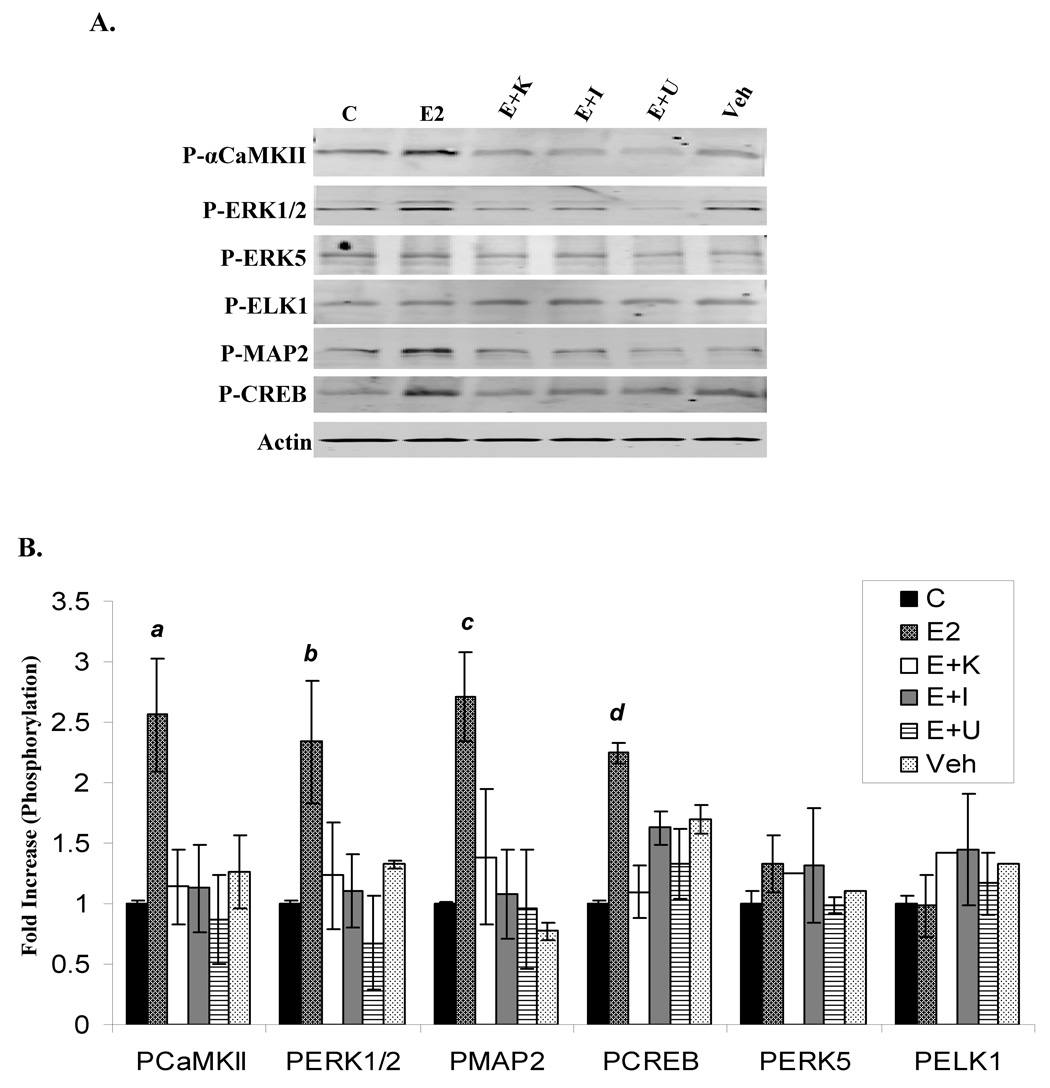

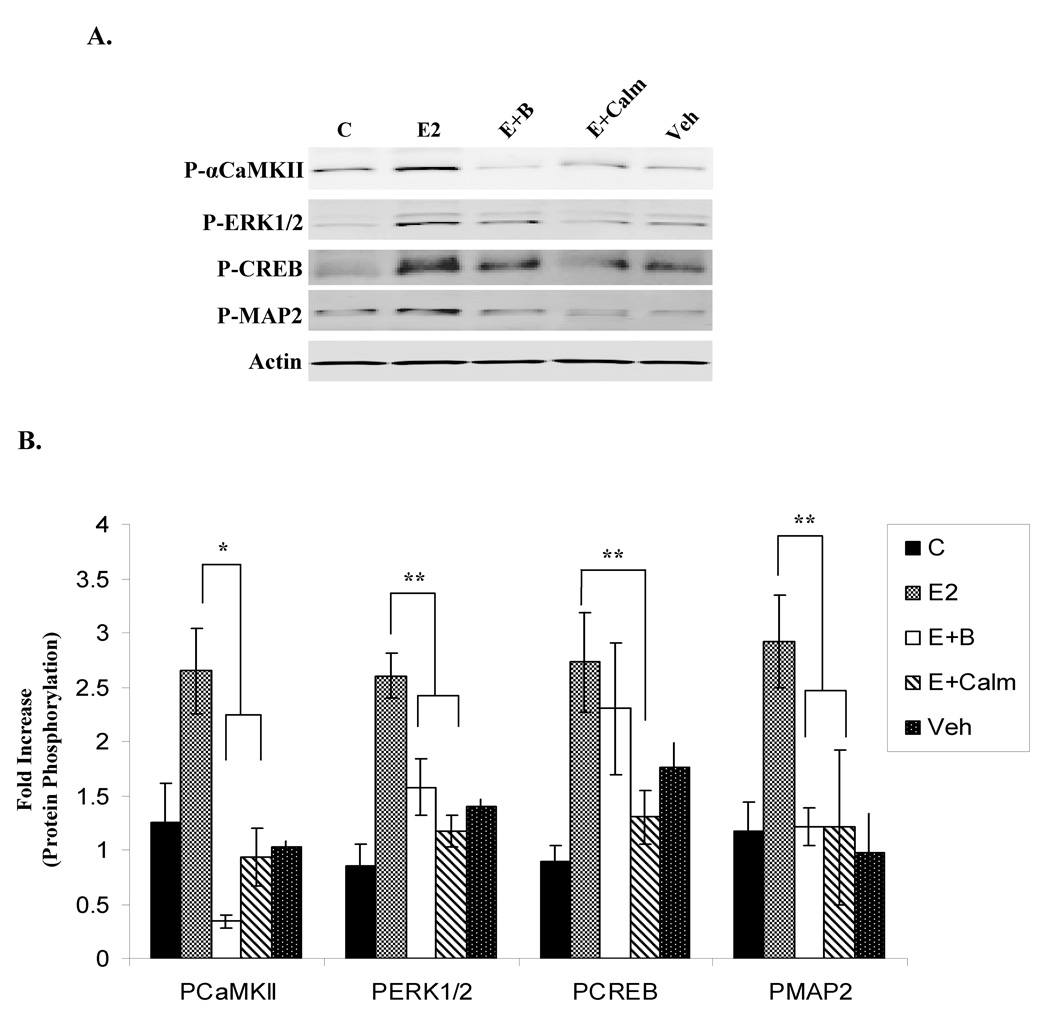

The ability of E2 to signal to αCaMKII as well as downstream target proteins was examined in cultured embryonic primary hippocampal neurons, which were chosen as a model due to the prevalence and functional significance of αCaMKII in these cells, and because we wanted to test our hypothesis in a non-immortalized cell line. Primary hippocampal neurons were either unstimulated or treated for 10 min with vehicle, E2, or E2 plus 30min pre-treatment with KN-62, ICI, or U0126, and western blot analysis was used to detect the phosphorylation status of a variety of proteins (Fig. 6A/B). E2 stimulates the autophosphorylation of αCaMKII as well as the phosphorylation of ERK1/2, CREB, and MAP2. Interestingly, E2 does not induce the phosphorylation of another MAPK family member, ERK5, or the transcription factor, ELK1. Inhibition of either CaMKII or ER activity with KN-62 or ICI, respectively, significantly decreases E2-induced ERK1/2, CREB, and MAP2 phosphorylation, and E2-stimulated CREB and MAP2 phosphorylation is reduced by blocking ERK1/2 action with U0126. Surprisingly, U0126 also inhibits αCaMKII autophosphorylation by E2, implicating MEK1/2 as a positive regulator of this event. Additionally, the effect of Ca2+/CaM signaling was investigated, and figure 7 shows that E2-induced ERK1/2, CREB, and MAP2 phosphorylation is severely compromised when Ca2+ signaling and CaM action were disrupted with BAPTA-AM or calmidazolium pre-treatment, respectively.

Figure 6. Rapid E2 action induces αCaMKII autophosphorylation as well as the phosphorylation of downstream proteins in a αCaMKII-dependent manner in primary hippocampal neurons.

(A) Cultured embryonic primary hippocampal neurons were either unstimulated (C) or treated with Veh (0.01% EtOH), E2 (1nM), or E2 (1nM) with 30 min pretreatment of KN-62 (E+K; 10uM), ICI (E+I; 1uM), or U0126 (E+U; 10uM). Immunoblotting detected phosphorylated levels of αCaMKII, ERK1/2, ERK5, ELK1, CREB, and MAP2 as well as pan-Actin. Representative blot. (B) Densitometry for phosphorylated kinase was normalized to total protein levels for 3 independent experiments, and presented as the mean fold increase over unstimulated control ± S.D. a) p<0.02; b) p < 0.05; c) p<0.04; d) p<0.05, comparing E2 treatment to all other conditions.

Figure 7. Ca2+/CaM action are required for E2-induced ERK1/2, CREB, and MAP phosphorylation in primary hippocampal neurons.

(A) Cultured embryonic primary hippocampal neurons were either unstimulated (C) or treated with Veh (0.01% EtOH), E2 (1nM), or E2 (1nM) with 30 min pre-treatment of BAPTA-AM (E+B; 10uM) or calmidazolium (E+Calm; 10uM). Immunoblotting detected phosphorylated levels of αCaMKII, ERK1/2, CREB, and MAP2 as well as pan-Actin. Representative blot. (B) Densitometry for phosphorylated kinase was normalized to total protein levels, and presented as the mean fold increase over unstimulated control ± S.D. (*) p < 0.01, (**) p < 0.02.

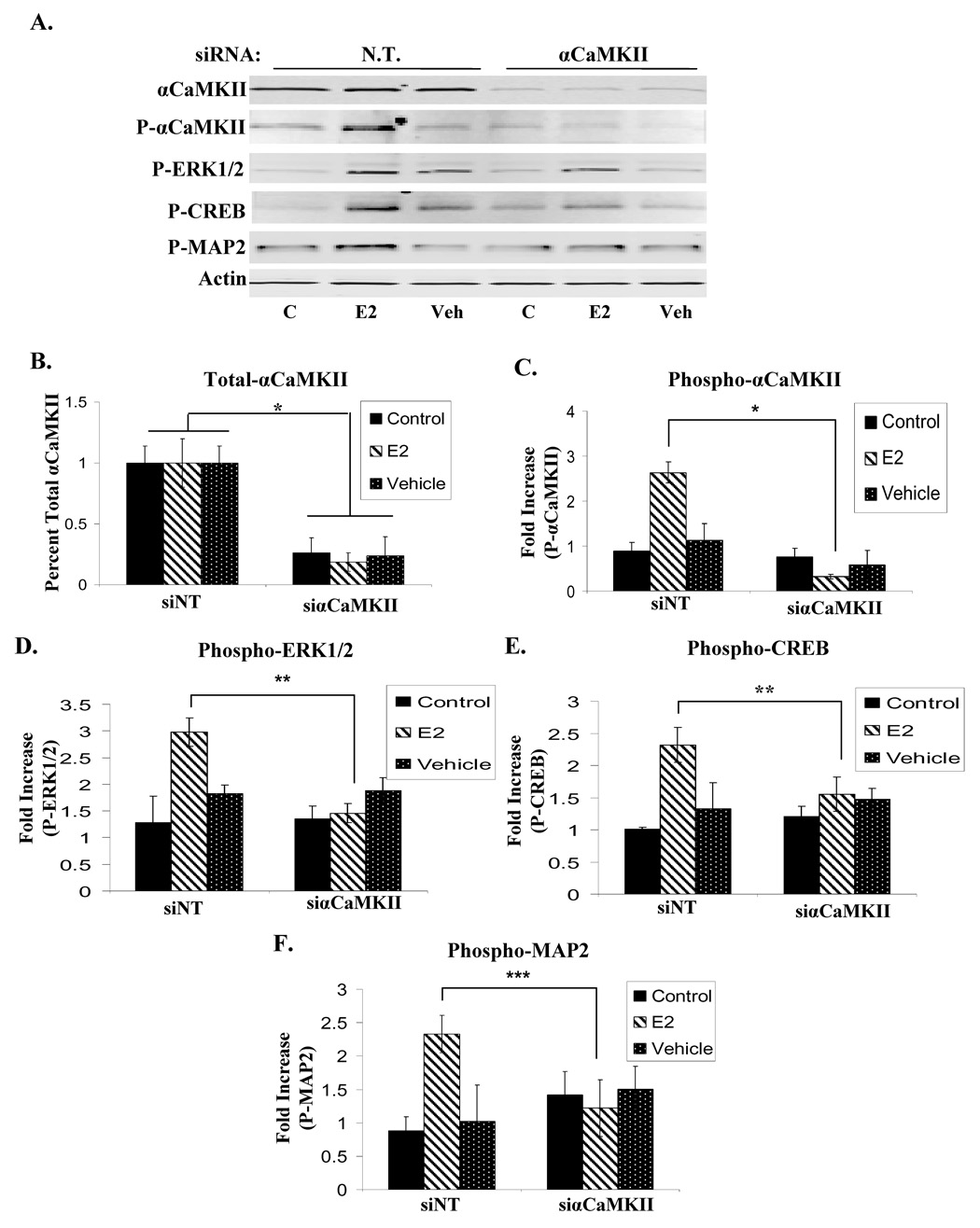

To directly demonstrate the requirement of αCaMKII for the E2-induced phosphorylation of downstream signaling proteins, its protein expression in primary hippocampal neurons was knocked down using specific siRNA oligonucleotides (Fig. 8A). Targeted inhibition of αCaMKII expression was achieved in siαCaMKII-transfected hippocampal neurons as demonstrated by western blot analysis; the total αCaMKII level is knocked down to ~23% of the level in neurons transfected with non-targeting (N.T.) siRNA (Fig. 8B). The siRNA-mediated inhibition of αCaMKII prevents E2-induced αCaMKII autophosphorylation (Fig. 8C) as well as ERK1/2 (Fig. 8D), CREB (Fig. 8E), and MAP2 (Fig. 8F) phosphorylation to the same extent as KN-62 pre-treatment. Together, these results indicate that αCaMKII action mediates the E2-induced phosphorylation of ERK1/2, CREB, and MAP2 in cultured embryonic primary hippocampal neurons.

Figure 8. Targeted inhibition of αCaMKII blocks E2-induced ERK1/2, CREB, and MAP2 phosphorylation.

(A) Cultured embryonic primary hippocampal neurons were transfected with either non-targeting siRNA (siN.T.) or siαCaMKII, and were unstimulated (C) or treated with Veh (0.01%EtOH) or E2 (1nM). Total αCaMKII, autophosphorylated αCaMKII, phosphorylated levels of ERK1/2, CREB, MAP2, and pan-Actin expression were then assayed via immunoblotting . Representative blot. (B) Densitometry for total αCaMKII was normalized to pan-Actin and presented as the mean relative protein expression ± S.D. Additionally, the phosphorylation status of αCaMKII (C), ERK1/2(D), CREB (E), and MAP2 (F) was examined post-siRNA introduction and ligand treatment. Phosphorylated levels of the indicated proteins were normalized to pan-Actin and presented as the mean fold increase over unstimulated control ± S.D. * p < 0.01; **p < 0.03; ***p < 0.05.

Discussion

The ability of E2 to influence signaling pathways in the brain has been examined with increasing interest however its effect on αCaMKII activity has not been described in detail. αCaMKII is a particularly appealing signaling partner for ER since linking the two proteins would provide valuable insight into the mechanism by which E2 influences cognitive function. We report here that E2 rapidly induces αCaMKII autophosphorylation in an ERα-and Ca2+ influx-dependent manner. This signaling is extranuclear and ultimately results in the phosphorylation of a variety of downstream proteins in immortalized GnRH neurons and cultured embryonic primary hippocampal neurons. Interestingly, the association of ERα with αCaMKII negatively impacts the ability of E2 to induce αCaMKII autophosphorylation, suggesting a novel model for the modulation of αCaMKII activity by ERα.

An early indication that ER signaling intersects with that of αCaMKII was first demonstrated in hippocampal neurons where Sawai and colleagues (2002) showed that E2 stimulates the activity of αCaMKII in an ICI-sensitive manner, implicating the involvement of ER. This previous study raises several interesting questions: which ER subtype mediates E2-induced αCaMKII activity and in what cellular compartment does it occur? What is the mechanism by which ER modulates αCaMKII activity? What are the downstream signaling events? We wanted to address these questions as well as others with this work.

We initially studied ER-modulated αCaMKII activity in NLT cells, the immortalized GnRH cell line, and found that the effect of E2 on αCaMKII autophosphorylation was rapid and transient. While E2 allowed for the autophosphorylation of neighboring kinase subunits, it was short-lived, presumably due to the dephosphorylation of the subunits by nearby phosphatases. As such, the stage of long-term/persistent αCaMKII activation by E2 was never reached in NLT cells since the rate of autophosphorylation never exceeded the rate of dephosphorylation. We also used cultured embryonic primary hippocampal neurons as a cellular model because 1) ERα has been found in the hippocampus of rodents and humans (Solum, 2001; Adams, 2002; Hu, 2003), and there are numerous reports detailing the effects of E2 on the rodent hippocampus including its positive role in dendritic spine density and synapse density (Woolley, 1998), and 2) αCaMKII is abundant in the hippocampus and its activity is essential for certain memory processes (Silva, 1992). We found that autophosphorylation of αCaMKII was significantly stimulated by 10 min of E2 and not vehicle treatment, and this increase was blocked by KN-62 pre-treatment in the primary hippocampal neurons. Clearly, rapid E2 action allows for the short-term autophosphorylation of αCaMKII in the 2 cell lines examined.

Numerous studies indicate that E2’s rapid effects in the brain are initiated outside of the nucleus (Kuroki, 2000; Mannella, 2006). Our ERα localization data in NLT neurons corresponds with other groups in that “classical” ERs are positioned not only in the nucleus, but in the cytoplasm and outgrowths as well (Clarke, 2000; Hart, 2007) where they are available to interact with cytoplasmic signaling cascades. Immunofluorescence and cell fractionation showed that E2-induced αCaMKII autophosphorylation in NLT neurons occurs specifically in the cell body and processes, suggesting that the extranuclear pool of ER is responsible for mediating this event. ER action is clearly required as ICI treatment significantly blocks E2-induced αCaMKII autophosphorylation.

Based on our data, ERα and not ERβ mediates E2-induced αCaMKII autophosphorylation in both NLT cells and co-transfected Cos7 cells. Use of the subtype-selective compounds, PPT and DPN, in NLT cells as well as the examination of SK-N-SH neuroblastoma cells (ERα-negative/ERβ-positive cells) allowed us to differentiate the effects of ERα versus ERβ, and show that ERα is responsible for the αCaMKII autophosphorylation induced by E2 in these particular cellular contexts. Additionally, the transient expression of ERβ with αCaMKII in Cos7 cells is unable to mediate kinase autophosphorylation while the co-expression of ERα allows for αCaMKII activity by E2. This result is somewhat surprising because both ER subtypes have been shown to be involved in the rapid induction of Ca2+ oscillations in hippocampal neurons (Zhao, 2007), which would presumably result in αCaMKII autophosphorylation mediated by either ERα or ERβ. However, closer examination of the hormone-independent association of ERβ with αCaMKII may provide insight as to why ERβ is unable to elicit kinase autophosphorylation; the ER binding site on αCaMKII overlaps with the CaM binding site so it is possible that ERβ competes with the binding of Ca2+/CaM and perhaps locks the kinase in an autoinhibited state, thus blocking autophosphorylation by E2. It would be interesting to see if a knock-down ERβ in NLT cells or a mutant of ERβ that cannot interact with αCaMKII would further enhance αCaMKII autophosphorylation by E2. Nonetheless, our finding that ERα is the sole subtype responsible for αCaMKII autophosphorylation supports the notion that ERα and ERβ do not have overlapping roles in brain function. Each subtype has a distinct spatial and temporal expression pattern in the forebrain (Gonzalez, 2007) and they play distinct roles in neuronal function. For example, ERα mediates the neuroprotective effects of E2 against ischemic brain injury (Dubal, 2001) whereas ERβ is responsible for the anti-anxiety and anti-depressive effects of E2 (Walf, 2007). However, it has been reported that ERβ is involved in CA1 LTP and hippocampal-dependent contextual fear conditioning (Day, 2005), so a closer examination of ERβ-selective agonists in the hippocampus is needed to fully appreciate the role of ERβ in the activation of αCaMKII within this brain region.

An understanding of the mechanism underlying E2-induced αCaMKII activity is of great interest, and our data indicates that Ca2+ influx via L-type Ca2+ channels and CaM action are required for αCaMKII autophosphorylation by E2 in both NLT and primary hippocampal neurons. The effects of E2 on Ca2+ are well documented; E2 stimulates Ca2+ influx (Wu, 2005; Zhao, 2005) as well as the release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores (Beyer, 1998). However, the hormone-dependent association of ERα and αCaMKII adds a level of complexity to the signaling. The hypothesis that the ERα-αCaMKII interaction directly activates αCaMKII was proven incorrect and instead, the interaction decreases the ability of E2 to activate αCaMKII by half. Thus, ERα is required initially for the E2-induced αCaMKII activity via Ca2+ influx, while it simultaneously downregulates it. As discussed above with ERβ, it is possible that the association of ERα with αCaMKII locks the kinase in an autoinhibited state however that hypothesis remains to be tested. These findings are in alignment with studies that examined a transgenic mouse model in which a constitutively active αCaMKII, CaMKII-Asp286, is expressed in an inducible and forebrain-specific fashion (Mayford, 1996; Bejar, 2002; Yasuda, 2006). They found that indiscriminate CaMKII activity results in the loss of low-frequency-induced LTP and deficits in spatial memory. Bejar and colleagues (2002) found that high expression of the transgene also affected fear-conditioned memory. Therefore, it is reasonable to imagine that ERα plays both a positive and negative role in E2-induced αCaMKII activation to prevent molecular and behavioral memory impairments. An alternative explanation is that the opposing effects of ER are in place to “prime” αCaMKII; it prevents αCaMKII from ever reaching maximal activity by E2 stimulation, and instead lowers the threshold for subsequent Ca2+ signals, allowing for a more efficient and perhaps, prolonged response. By maintaining sub-maximal activity, the dual role of ERα permits αCaMKII to function as a Ca2+ frequency detector to translate the information encoded by the Ca2+ spikes into various levels of kinase activity that correspond with specific cellular responses. However, there exists an equally legitimate hypothesis for why the ERα interaction mutant (ERα-V376R) significantly enhances E2-induced αCaMKII autophosphorylation compared to wild-type ERα: perhaps activated ERα-V376R increases other stimulatory actions in the cell such as Ca2+ mobilization to a greater degree than wild-type ERα, which would lead to enhanced αCaMKII autophosphorylation overall. We have not sufficiently tested this theory so it must be considered as a possibility. Still, it is enticing to hypothesize instead that the association of ERα with αCaMKII occurs to maintain the sensitivity and selectivity of αCaMKII activity in neurons.

It is known that αCaMKII phosphorylates a wide variety of substrates involved in numerous neuronal processes (McGlade-McCulloh, 1993; Omkumar, 1996; Stefani, 1997; Liu, 2005) and we have identified ERK1/2, CREB, and MAP2 as proteins targeted by E2-induced αCaMKII autophosphorylation in NLT and primary hippocampal neurons. Like αCaMKII, all three proteins are involved in neuronal differentiation, and ERK1/2 and CREB have also been shown to play a role in LTP and memory processes (Trifilieff, 2006). E2 action has previously been linked to ERK1/2 and CREB phosphorylation in various populations of neurons and in vivo (Lee, 2004; Bryant DN, 2005; Szego, 2006), and we have provided evidence that αCaMKII action mediates their phosphorylation by E2 in NLT and primary hippocampal neurons. CREB can be directly phosphorylated by αCaMKII (Wu, 2001), although in our studies it appears that CREB is indirectly affected by αCaMKII-mediated ERK1/2 activity since its phosphorylation by E2 was blocked by U0126 pre-treatment. This finding corresponds with reports demonstrating that CREB is phosphorylated by ribosomal S6 kinase (RSK) family members, which are first activated by ERK1/2 (Cammarota, 2001). To the best of our knowledge we are the first to report that E2 is capable of stimulating MAP2 phosphorylation in primary hippocampal neurons. MAP2 is a direct target of αCaMKII, although it can also be phosphorylated by ERK1/2 (Sanchez, 2000) as we have confirmed in our studies; its phosphorylation by E2 is blocked by U0126 pre-treatment. Expectedly, both Ca2+-influx and CaM signaling are required for E2-induced ERK1/2, CREB, and MAP2 phosphorylation that is mediated by αCaMKII.

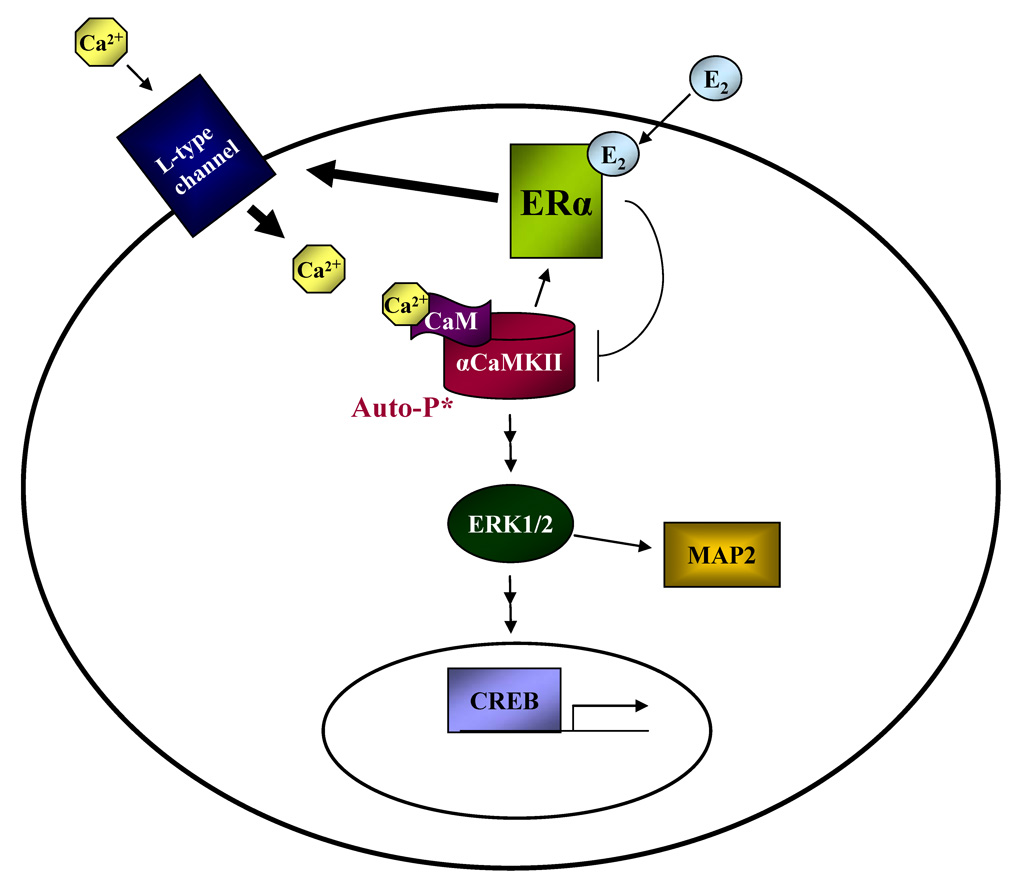

The use of pharmacological inhibitors and RNAi technology allowed us to order the observed E2-induced signaling (Fig. 9). ERα is rapidly activated by E2, which elevates intracellular Ca2+ levels by Ca2+ influx through L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. αCaMKII detects the Ca2+ spike and undergoes autophosphorylation to become transiently active and mediate ERK1/2 activation. ERK1/2 subsequently leads to the phosphorylation of CREB and MAP2. However, the interaction of ERα with αCaMKII decreases E2-induced kinase autophosphorylation even though ER is initially required for this event via Ca2+ influx. It appears as though the activating signal of E2 dominates the negative effect of ER since there is a clear, positive downstream response to E2-activated αCaMKII.

Figure 9. Model of E2-induced αCaMKII signaling.

E2 activates ERα, elevating intracellular Ca2+ levels by inducing Ca2+ influx via L-type Ca2+ channels. The Ca2+ spike is detected by αCaMKII, which indirectly phosphorylates ERK1/2 after being activated. Active ERK1/2 then results in the phosphorylation of CREB and MAP2. The ERα-αCaMKII interaction attenuates the ability of E2 to stimulate kinase autophosphorylation even though the receptor is initially required for E2 to induce αCaMKII activity. However, it appears as though the activating signal of E2 (thick arrows) supercedes the negative effect of ER since there is a clear, positive downstream response to E2-activated αCaMKII.

In summary, E2 rapidly evokes the ERα-dependent autophosphorylation of αCaMKII in co-transfected Cos7 cells, immortalized GnRH neurons, and primary hippocampal neurons. The activity requires Ca2+ influx and CaM action, and is kept in check by the interaction of ERα with αCaMKII, which potentially maintains the sensitivity and selectivity of αCaMKII activity. Ultimately, E2-stimulated αCaMKII activity results in the phosphorylation of ERK1/2, CREB, and MAP2, proteins that are all involved in various aspects of multiple neuronal processes, including proliferation, differentiation, and LTP. The current study increases our understanding of the mechanistic contribution of rapid E2 signaling in the brain, which is necessary for the development of hormonal therapies that specifically target brain function without increasing the risk of breast and uterine cancer in postmenopausal women.

Experimental Procedures

Chemicals and Antibodies

17β-estradiol (E2), trans-4-hydroxytamoxifen (T), KN-62, BAPTA-AM, Nifedipine, W7, U0126, forskolin, and A23187 were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Propyl pyrazole triol (PPT), diarylpropionitrile (DPN), ICI 182, 780 (ICI), and calmidazolium were purchased from Tocris Cookson (Ballwin, MO). Anti-αCaMKII used for immunofluorescence, antiphospho-αCaMKII (T286) used for western blotting, anti-histone H1 and anti-ERα (MC-20) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-phospho-αCaMKII used for IHC, anti-phospho-ERK1/2, anti-phospho-CREB, anti-phospho-MAP2, anti-phospho-ERK5, and anti-phospho-ELK1 were purchased from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA). Anti-αCaMKII used for WB was obtained from Zymed (Invitrogen). Anti-pan actin was obtained from Chemicon (Billerica, MA) and anti-ERβ was purchased from Affinity BioReagents (Golden, CO). Anti-FLAG is from Sigma and the ERα antibody, H222.2, is produced in our lab.

Cell Culture

NLT (mouse gondadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) immortalized neurons) and Cos7 (monkey kidney) cells were routinely cultured in phenol red-free DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). SK-N-SH (human neuroblastoma) cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and grown in EMEM (Cambrex) supplemented with 10% FBS. All cells were maintained at 37 C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Primary hippocampal neurons were prepared and provided by the Center for Mental Retardation and Disability (University of Chicago) and maintained in Neurobasal Media A (Invitrogen) supplemented with B27, L-glutamine, and penicillin/streptomycin at 37 C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Plasmids and Mutagenesis

The wild-type human αCaMKII expression vector, SRα-αCaMKII, was kindly provided by Dr. Howard Schulman (Stanford University, CA). The wild-type human ERα (HEGO) is expressed in the pSG5 vector and was a gift from Dr. Pierre Chambon (Institute de Chimie Biologique, France). pcDNA3.1-αCaMKII was obtained by subcloning SRα-αCaMKII into the pcDNA3.1(-) vector (Invitrogen). FLAG-tagged ERα and ERβ were obtained by subcloning the receptor into pCMV-FLAG expression vector (Sigma). Site-directed mutagenesis was performed to create αCaMKII-L304A and ERα-V376R with the QuickChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Transient Transfections and Luciferase Assays

For transfections, Cos7 cells were seeded in DMEM+10% FBS in 100mm dishes for co-immunoprecipitation (CoIP) and in 6-well dishes for western blot analysis. For CoIP, Polyfect (QIAGEN) was used to transfect Cos7 cells with either wild-type ERα (pSG5-HEGO or FLAG-ERα, depending on the experiment), FLAG-ERβ, or HEGO-V376R and pcDNA3.1-αCaMKII in DMEM+10% dextran-coated charcoal stripped fetal bovine serum (S-FBS). 48 hr posttransfection, the cells were used in CoIP studies. For rapid ligand treatments, cells were transfected with Polyfect in DMEM+10% S-FBS with wild-type pcDNA3.1-αCaMKII in the presence or absence of the following ER constructs: FLAG-ERα, FLAG-ERβ, pSG5-HEGO, or HEGO-V376R. 48 hr post-transfection, treatments were reconstituted in PBS, ethanol or DMSO and cells were treated with the concentrations and times indicated. For luciferase assays, NLT cells were seeded in DMEM+10% FBS in 48-well dishes and transfected Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions in DMEM + 10% S-FBS with 3ERE-Luc (estrogen response element-luciferase) reporter and β-galactosidase (β-Gal) expression plasmid or control vector. Additionally, SK-N-SH cells were seeded in EMEM+10% FBS and transfected with Polyfect in DMEM+10% S-FBS with 3ERE-Luc and β-Gal. The day after transfection, treatments were administered to the cells at the dilution indicated in fresh DMEM+10% S-FBS. The next day, cells were harvested and assayed for both luciferase and β-Gal activity (Microbeta Wallac, Perkin Elmer; Spectra Max 250, Molecular Devices). Luciferase activity was normalized for transfection efficiency using β-Gal and reported as a fold-induction over control.

Cellular Fractionation

Nuclear and cytosolic proteins were extracted as previously described (Sun, 2001). After treatment, NLT cells were washed with ice-cold PBS containing phosphatase inhibitors. The cells were extracted in TNM buffer (10mM Tris, pH 7.4, 100mM NaCl, 2mM MgCl2, 300mM sucrose, 1% thiodiethanol, 1mM Na3VO4, 50mM NaF, 1:1000 PIC), disrupted with a syringe and needle, and centrifuged at 4500 × g for 10 min at 4C. The remaining samples were centrifuged at 4500 × g for 10 min at 4C, and the resulting supernatant was retained as the cytosolic fraction. The pellet (crude nuclear fraction) was resuspended in an equal volume of TNM buffer. Whole cell, cytosolic fraction, and nuclear fraction samples were analyzed for the indicated proteins by western blot analysis.

Western Blot Analysis

For western blotting, cells were washed with ice-cold PBS containing phosphatase inhibitors, lysed in 2x laemelli sample buffer, and boiled for 5 min. Samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and detected by immunoblotting with the indicated primary antibodies and fluorescently-tagged secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) using the Odyssey Infrared System (Li-COR, NE). Both phosphorylated and total protein expression were quantified by densitometry using the Odyssey software (Li-COR). Phosphorylated levels of αCaMKII, ERK1/2, and CREB were all normalized to total protein levels, and to avoid inter-assay variations, the values obtained were normalized with the value measured for the non-treated control samples (C) in each experiment. Data are presented as the mean fold increase ± S.D. for at least 3 independent experiments. Student’s t-test was used to produce P values.

Immunofluorescence

For immunofluorescence, NLT cells were plated in a 96-well black/clear bottom dish in DMEM with 10% FBS for 24 hr, then grown for an additional 16hr in DMEM with 10% S-FBS. Cells were treated as indicated, fixed in buffered formalin (Fisher Scientific) for 15 min, and then ice-cold methanol was applied for 10 min. The cells were blocked in 5% goat serum in PBS/0.3% Triton X-100 and stained overnight at 4C with both anti-ERα (1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and anti-αCaMKII (1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for colocalization, or anti-phospho-αCaMKII (1:200, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) alone to detect kinase activation. Alexa 594-conjugated goat anti-rabbit and Alex 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse (1:2000 and 1:2500 respectively, Molecular Probes) were applied for 1 hr, followed by DAPI staining (Molecular Probes). Images were acquired using the IXMicro imager and analyzed with MetaXpress software (Molecular Devices, CA).

GST Pull-Down Assay

pcDNA3.1-αCaMKII constructs were radiolabeled with 35S-Methionine (Amersham Biosciences) using the TnT Quick Coupled Transcription/Translation System by Promega Corp. (Madison, WI) following the manufacturer’s instructions exactly. The resulting labeled proteins were incubated with either wild-type GST-ERα-LBD or one of the following GST-LBD mutants, GST-ERα-I358R, GST-ERα-V376R, or GST-ERα-E542K bound to glutathione-sepharose beads for 1.5 hr at 4C in the presence of the ligand indicated. Samples were washed 3 times with binding buffer (20mM Tris, pH 7.6; 50mM NaCl; 0.05% Nonidet P-40; 1mM dithiothreitol; 1:1000 protease inhibitor cocktail) and bound proteins were eluted with 2x laemelli sample buffer. After 5 min boiling, the samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by autoradiography on the STORM scanner (GE Healthcare BioSciences).

CoImmunoprecipitation

Cos7 cells were plated and transfected as described above and then treated with either vehicle (0.01% EtOH) or E2 (10nM) for 10 min, washed with ice-cold PBS and extracted in lysis buffer (50mM Tris, pH 8.0, 150mM NaCl, 10mM MgCl2, 1% NP-40, 1mM Na3VO4, 50mM NaF, 1:1000 PIC). The resulting cell lysates were incubated for 1 hr with Protein A/G-PLUS Agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA) at 4C to preclear the lysates. Depending on the experiment ERα was subsequently immunoprecipitated with either 2ug anti-FLAG or 2ug H222.2, ERβ was immunoprecipitated with 2ug anti-FLAG, and αCaMKII was immunoprecipitated with 4ug of anti-αCaMKII in the presence of Protein A/G PLUS agarose overnight at 4 C. The samples were gently washed 3 times in wash buffer (20mM Tris, pH 7.6, 50mM NaCl, 0.05% Nonidet P-40, 1mM dithiothreitol, 1:1000 PIC) and bound proteins were eluted with 2x laemelli sample buffer. Samples were boiled and western blotting was performed to detect ERα, ERβ, and αCaMKII.

siRNA Silencing Experiments

Primary hippocampal neurons were allowed to grow in Neurobasal media supplemented with B27 for 5 days and then the indicated ON-TARGET plus siRNA was introduced using the Dharmafect system according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Dharmacon Inc., CO). Briefly, 200nM of αCaMKII or non-targeting siRNA was transfected into neurons using Dharmafect 3. The cells were incubated at 37 C for 60 hr with the siRNA of interested, treated as indicated, and then assayed for the expression levels of the targeted protein via western blot analysis. Additionally, the phosphorylation status of a variety of proteins including αCaMKII, ERK1/2, CREB, and MAP2 was examined post-siRNA and ligand treatment. Total αCaMKII levels were normalized to Actin and presented as the mean relative protein expression ± S.D. The phosphorylated levels of αCaMKII, ERK1/2, CREB, and MAP2 were normalized to total protein levels, and to avoid inter-assay variations, the values obtained were normalized with the value measured for the non-treated control samples (C) in each experiment. Data are presented as the mean fold increase ± S.D. and P values were calculated with the Student’s t-test.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the NCI through grant CA089489. E.O. was supported by a Department of Defense predoctoral grant W81XWH-05-1-0241. A.B. was supported by a generous donation from Mr. and Mrs. Gordon Segal. We would like to thank Dr. Jeremy Marks and Janice Wang at the Center for Mental Retardation and Disability (The University of Chicago) for the preparation of embryonic primary hippocampal neurons.

Abbreviations

- ER

estrogen receptor

- E2

17β-estradiol

- ERE

estrogen response element

- LBD

ligand-binding domain

- T

tamoxifen

- PPT

propyl pyrazole triol

- DPN

diarylpropionitrile

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adams M, Fink SE, Shah RA, Janssen WG, Hayashi S, Milner TA, McEwen BS, Morrison JH. Estrogen and aging affect the subcellular distribution of ERα in the hippocampus of female rats. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:3608–3614. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-09-03608.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahokas A, Kaukoranta J, Wahlbeck K, Aito M. Estrogen deficiency in severe postpartum depression: successful treatment with sublingual physiologic 17beta-estradiol: a preliminary study. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2001;62:332–336. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v62n0504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida O, Lautenschlager N, Vasikaram S, Leedman P, Flicker L. Association between physiological serum concentration of estrogen and the mental health of community-dwelling postmenopausal women age 70 years and over. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2005;13:142–149. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.2.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ba F, Pang PK, Davidge ST, Benishin CG. The neuroprotective effects of estrogen in SK-N-SH neuroblastoma cell cultures. Neurochem. Int. 2004;44:401–411. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bejar R, Yasuda R, Krugers H, Hood K, Mayford M. Transgenic calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II activation: dose-dependent effects on synaptic plasticity, learning, and memory. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:5719–5726. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-13-05719.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer C, Raab H. Nongenomic effects of oestrogen: embryonic mouse midbrain neurones respond with a rapid release of calcium from intracellular stores. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1998;10:255–262. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanquet P. Identification of two persistently activated neurotrophin-regulated pathways in rat hippocampus. Neuroscience. 1999;95:705–719. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00489-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant D, Bosch MA, Ronnekleiv OK, Dorsa DM. 17-beta estradiol rapidly enhances extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2 phosphorylation in the brain. Neuroscience. 2005;133:343–352. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cammarota M, Bevilaqua LRM, Dunkley PR, Rostas JAP. Angiotensin II promotes the phosphorylation of cyclic AMP-responsive element binding protein (CREB) at Ser133 through an ERK1/2-dependent mechanism. J. Neurochem. 2001;79:1122–1128. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke C, Norfleet AM, Clarke MS, Watson CS, Cunningham KA, Thomas ML. Perimembrane localization of the estrogen receptor alpha protein in neuronal processes of cultured hippocampal neurons. Neuroendocrinology. 2000;71:34–42. doi: 10.1159/000054518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day M, Sung A, Logue S, Bowlby M, Arias R. Beta estrogen receptor knockout (BERKO) mice present attenuated hippocampal CA1 long-term potentiation and related memory deficits in contextual fear conditioning. Behav. Brain Res. 2005;164:128–131. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubal D, Zhu H, Yu J, Rau SW, Shughrue PJ, Merchenthaler I, Kindy MS, Wise PM. Estrogen receptor alpha, not beta, is a critical link in estradiol-mediated protection against brain injury. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:1952–1957. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041483198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duff S. A beneficial effect of estrogen on working memory in postmenopausal women taking hormone replacement therapy. Horm.Behav. 2000;38:262–276. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2000.1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estrada-Camarena E, Fernández-Guasti A, López-Rubalcava C. Antidepressant-like effect of different estrogenic compounds in the forced swimming test. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:830–838. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng W, Ribeiro RC, Wagner RL, Nguyen H, Apriletti JW, Fletterick RJ, Baxter JD, Kushner PJ, West BL. Hormone-dependent coactivator binding to a hydrophobic cleft on nuclear receptors. Science. 1998;280:1747–1749. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5370.1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fugger H, Foster TC, Gustafsson J, Rissman EF. Novel effects of estradiol and estrogen receptor alpha and beta on cognitive function. Brain Res. 2000;883:258–264. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02993-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudilliere B, Konishi Y, Iglesia N, Yao G-I, Bonni A. A CaMKII-NeuroD signaling pathway specifies dendritic morphogenesis. Neuron. 2004;41:229–241. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00841-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez M, Cabrera-Socorro A, Perez-Garcia C, Fraser JD, Lopez FJ, Alonso F, Meyer G. Distribution patterns of estrogen receptor alpha and beta in the human cortex and hippocampus during development and adulthood. J. Comp. Neurol. 2007;503:790–802. doi: 10.1002/cne.21419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson P, Schulman H. Neuronal Ca2+/Calmodulin-dependent protein kinases. Annu Rev. Biochem. 1992;61:559–601. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.61.070192.003015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart S, Snyder MA, Smejkalova T, Woolley CS. Estrogen mobilizes a subset of estrogen receptor-alpha-immunoreactive vesicles in inhibitory presynaptic boutons in hippocampal CA1. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:2102–2111. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5436-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heldring N, Pike A, Andersson S, Matthews J, Cheng G, Hartman J, Tujague M, Ström A, Treuter E, Warner M, Gustafsson JA. Estrogen receptors: how do they signal and what are their targets. Physiol. Rev. 2007;87:905–931. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00026.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, Qin S, Lu YP, Ravid R, Swaab DF, Zhou JN. Decreased ERα expression in hippocampal neurons in relation to hyperphosphorylated tau in Alzheimer patients. Acta. Neuropathol. 2003;106:213–220. doi: 10.1007/s00401-003-0720-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudmon A, Schulman H. Neuronal Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II: The role of structure and autoregulation in cellular function. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2002;71:473–510. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroki Y, Fukushima K, Kanda Y, Mizuno K, Watanabe Y. Putative membrane-bound estrogen receptors possibly stimulate mitogen-activated protein kinase in the rat hippocampus. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2000;400:205–209. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00425-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Campomanes CR, Sikat PT, Greenfield AT, Allen PB, McEwen BS. Estrogen induces phosphorylation of cyclic AMP response element binding (pCREB) in primary hippocampal cells in a time-dependent manner. Neuroscience. 2004;124:549–560. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R, Lambe EK, Aghajanian GK. Somatodendritic autoreceptor regulation of serotonergic neurons: dependence on L-tryptophan and tryptophan hydroxylase-activating kinases. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2005;21:945–958. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.03930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannella P, Brinton RD. Estrogen receptor protein interaction with phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase leads to activation of phosphorylated Akt and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 in the same population of cortical neurons: a unified mechanism of estrogen action. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:9439–9447. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1443-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayford M, Bach ME, Huang YY, Wang L, Hawkins RD, Kandel ER. Control of memory formation through regulated expression of a CaMKII transgene. Science. 1996;274:1678–1683. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlade-McCulloh E, Yamamoto H, Tan SE, Brickey DA, Soderling TR. Phosphorylation and regulation of glutamate receptors by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Nature. 1993;362:640–642. doi: 10.1038/362640a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nethrapalli I, Singh M, Guan X, Guo Q, Lubahn DB, Korach KS, Toran-Allerand CD. Estradiol (E2) elicits SRC phosphorylation in the mouse neocortex: the initial event in E2 activation of the MAPK cascade? Endocrinology. 2001;142:5145–5148. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.12.8546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omkumar R, Kiely MJ, Rosenstein AJ, Min KT, Kennedy MB. Identification of a phosphorylation site for calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in the NR2B subunit of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;279:31670–31678. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.49.31670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piiper A, Dikic I, Lutz MP, Leser J, Kronenberger B, Elez R, Cramer H, Müller-Esterl W, Zeuzem S. Cyclic AMP induces transactivation of the receptors for epidermal growth factor and nerve growth factor, thereby modulating activation of MAP kinase, AKT, and neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:43623–43630. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203926200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez C, Diaz-Nido J, Avila J. Phosphorylation of microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2) and its relevance for the regulation of the neuronal cytoskeleton function. Prog. Neurobiol. 2000;61:133–168. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(99)00046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandstrom N, Williams CL. Spatial memory retention is enhanced by acute and continuous estradiol replacement. Horm. Behav. 2004;45:128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2003.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawai T, Bernier F, Fukushima T, Hashimoto T, Ogura H, Nishizawa Y. Estrogen induces a rapid increase of calcium-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II activity in the hippocampus. Brain Res. 2002;950:308–311. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03186-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shughrue P, Lane MV, Merchenthaler I. Comparative distribution of estrogen receptor-alpha and -beta mRNA in the rat central nervous system. J. Comp. Neurol. 1997;388:507–525. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19971201)388:4<507::aid-cne1>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva A, Stevens CF, Tonegawa S, Wang Y. Deficient Hippocampal Long-Term Potentiation in alpha-Calcium-Calmodulin Kinase II Mutant Mice. Science. 1992;257:201–206. doi: 10.1126/science.1378648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slooter AJ. Estrogen use and early onset Alzheimer's disease: a population-based study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1999;67:779–781. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.67.6.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solum D, Handa RJ. Localization of ERalpha in pyramidal neurons of the developing rat hippocampus. Dev. Brain. Res. 2001;128:165–175. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(01)00171-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J, Wang CX, Song DK, Wang P, Shuaib A, Hao C. Interferon gamma induces neurite outgrowth by upregulation of p35 neuron-specific cyclin-dependent kinase 5 activator via activation of ERK1/2 pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:12896–12901. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412139200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefani G, Onofri F, Valtorta F, Vaccaro P, Greengard P, Benfenati F. Kinetic analysis of the phosphorylation-dependent interactions of synapsin I with rat brain synaptic vesicles. J. Physiol. 1997;504:501–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.501bd.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Chen HY, Davie JR. Effect of estradiol on histone acetylation dynamics in human breast cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:49435–49442. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108364200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szego E, Barabás K, Balog J, Szilágyi N, Korach KS, Juhász G, Abrahám IM. Estrogen induces estrogen receptor alpha-dependent cAMP response element-binding protein phosphorylation via mitogen activated protein kinase pathway in basal forebrain cholinergic neurons in vivo. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:4104–4110. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0222-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang MX. Effect of oestrogen during menopause on risk and age at onset of Alzheimer's disease. Lancet. 1996;348:429–432. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)03356-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trifilieff P, Herry C, Vanhoutte P, Caboche J, Desmedt A, Riedel G, Mons N, Micheau J. Foreground contextual fear memory consolidation requires two independent phases of hippocampal ERK/CREB activation. Learn. Mem. 2006;13:349–358. doi: 10.1101/lm.80206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walf A, Frye CA. Administration of estrogen receptor beta-specific selective estrogen receptor modulators to the hippocampus decrease anxiety and depressive behavior of ovariectomized rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2007;86:407–414. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Y, Perez EJ, Green PS, Sarkar SN, Simpkins JW. nNOS is involved in estrogen mediated neuroprotection in neuroblastoma cells. Neuroreport. 2004;15:1515–1518. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000131674.92694.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winder D, Martin KC, Muzzio IA, Rohrer D, Chruscinski A, Kobilka B, Kandel ER. ERK plays a regulatory role in induction of LTP by theta frequency stimulation and its modulation by beta-adrenergic receptors. Neuron. 1999;24:715–726. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81124-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley C. Estrogen-mediated structural and functional synaptic plasticity in the female rat hippocampus. Horm. Behav. 1998;34:140–148. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1998.1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T, Wang JM, Chen S, Brinton RD. 17beta-estradiol induced Ca2+ influx via L-type calcium channels activates the Src/ERK/cyclic-AMP response element binding protein signal pathway and BCL-2 expression in rat hippocampal neurons: a potential initiation mechanism for estrogen-induced neuroprotection. Neuroscience. 2005;135:59–72. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, McMurray CT. Calmodulin kinase II attenuation of gene transcription by preventing cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) dimerization and binding of the CREB-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:1735–1741. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006727200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda M, Mayford MR. CaMKII activation in the entorhinal cortex disrupts previously encoded spatial memory. Neuron. 2006;50:309–318. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L, Chen S, Ming Wang J, Brinton RD. 17-beta estradiol induces Ca2+ influx, dendritic and nuclear Ca2+ rise and subsequent cyclic AMP response element-binding protein activation in hippocampal neurons: a potential initiation mechanism for estrogen neurotrophism. Neuroscience. 2005;132:299–311. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.11.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L, Brinton RD. Estrogen receptor α and β differentially regulate intracellular Ca2+ dynamics leading to ERK phosphorylation and estrogen neuroprotection in hippocampal neurons. Brain Res. 2007;1172:48–59. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.06.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]