Abstract

Exposure to certain viruses and parasites has been shown to prevent the induction of transplantation tolerance in mice, via generation of cross-reactive memory T cell responses or induction of bystander activation. Bacterial infections are common in the peri-operative period of solid organ allograft recipients in the clinic, and correlations between bacterial infections and acute allograft rejection have been reported. However, whether bacterial infections at the time of transplantation have any effect on the generation of transplantation tolerance remains to be established. We used the Gram-positive intracellular bacterium Listeria monocytogenes (LM) as a model pathogen, as its effects on immune responses are well described. Peri-operative LM infection prevented cardiac and skin allograft acceptance induced by anti-CD154 and donor-specific transfusion (DST) in mice. LM-mediated rejection was not due to the generation of cross-reactive T cells and was largely independent of signaling via MyD88, an adaptor for most toll-like receptors (TLRs), IL-1 and IL-18. Instead, transplant rejection following LM infection was dependent on the expression of the phagosome-lysing pore-former listeriolysin O (LLO) and on IFNα/βR signaling. Our results indicate that bacterial exposure at the time of transplantation can antagonize tolerogenic regimens by enhancing alloantigen-specific immune responses, independent from the generation of cross-reactive memory T cells.

Keywords: Rodent, T cells, Tolerance, Transplantation

Introduction

Clinical data support a correlation between viral infections and acute rejection of established allografts (1-4). Experimental animal models have revealed that the exposure of hosts to viral or parasitic agents prior to transplantation can result in the development of memory T cells (5-7) that are resistant to the effects of anti-CD154 therapy (8, 9). A subset of these pathogen-specific memory T cells has been shown to cross-react, by molecular mimicry, with alloantigen presented by donor or recipient MHC molecules (10). In addition to viral infections prior to transplantation, acute or persistent viral infections at the time of transplantation can prevent the induction of tolerance by costimulation-targeting regimens (11-14). This is thought to occur via direct activation of cross-reacting alloreactive T cells by viral antigens (7, 9) or upon bystander activation of allospecific T cells (9, 12). We and others have also shown that engagement of single TLRs, receptors that recognize molecular patterns expressed by viruses, fungi, parasites and bacteria, is sufficient to prevent transplantation tolerance by anti-CD154 mAb (15-17). Conversely, elimination of the TLR adaptor MyD88 facilitated the induction of transplantation tolerance to skin allografts (15, 17). Together, these experiments underscore the importance of the TLR/MyD88 pathway in the ability to prevent transplantation tolerance (18). Whether different classes of live microorganisms can all trigger acute rejection and utilize the TLR/MyD88 pathway to do so remains to be investigated.

Bacterial infections occurring during the peri-operative or early post-operative period have been reported to occur in liver, kidney and heart transplant recipients and are especially prevalent in lung, small bowel and bone marrow transplants in both adult and pediatric recipients (19-21). The incidence of these early bacterial infections can reach 20-80% of patients and activation by diverse microorganisms of the innate and adaptive immune system is likely to trigger multiple immune consequences. However, it is not clear whether bacterial infections interfere with allograft acceptance in the clinic or whether they could hinder the development of transplantation tolerance.

LM is an intracellular Gram-positive bacterium that has been used extensively to study the mammalian immune responses to infection (22). The natural route of LM infection is through the gastrointestinal tract, and food-borne LM infections have been reported to occur in transplanted patients within the first 6 months after transplantation (23, 24), although their consequences on alloimmune responses and transplant fate are not known. Following ingestion, LM traverses the epithelial-cell layer and disseminates in the blood stream to other organs, such as liver and spleen. LM is phagocytosed by splenic and hepatic macrophages, as well as by hepatocytes and escapes the phagosome by secreting listeriolysin O (LLO), which destroys the phagosomal membrane. LM then propels itself though the cytosol and infects neighboring cells using the actin-assembly-inducing protein (ActA). The invasion of the cytosol triggers early inflammatory responses and, ultimately, protective immunity that depends both on innate and adaptive immune responses. Innate immune events include the production of MCP-1 (CCL2) and Type I IFNs in a MyD88-independent but NF-κB-dependent, manner (25). The secretion of MCP-1 by LM-infected cells results in the emigration of neutrophils and blood CD11b+ monocytes out of the bone marrow (26). The monocytes then differentiate in a MyD88-dependent manner into a unique population of TNFα- and iNOS-producing DCs (TipDC). Nitric oxide, reactive oxygen radicals and TNFα produced by neutrophils and TipDCs are the principal mediators of early LM clearance. TipDCs (CD11bint/CD11cint/Mac-3high) are not required for the priming of LM-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses (26). Instead, CD8+ DCs are reported to be the principal DC subset that initiates LM-specific CD8+ T cell responses in vivo (27), although in vitro-generated CD8- DC subsets can also stimulate LM-specific CD8+ T cells (28).

In this study, we have investigated whether LM infection at the time of transplantation can prevent the induction of tolerance by anti-CD154/DST. We here report that infection with LM potently antagonizes the induction of allograft tolerance in a largely MyD88-independent, but LLO- and type I IFN-dependent, manner. These results draw attention to the potential impact of peri-operative bacterial infections in transplant recipients in the clinic and highlight novel potential molecular mechanisms of prevention of tolerance.

Materials and Methods

Mice

C57BL/6 (B6, H-2b), BALB/c (B/c, H-2d), C3H/HeJ (H-2k), CD4-/-, and CD8-/- mice on the B6 background were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. MyD88-/- mice on a B/c and a B6 background were kindly provided by Dr. S. Akira (Osaka University, Japan) (29). MyD88+/- littermates were used as wildtype control mice. IFNαR1-/- mice (8 generation backcrosses to B6) that lack IFN-α and IFN-β receptor signaling were obtained from Albert Bendelac (University of Chicago), OTII-Tg mice on a RAG-/-/B6/CD90.1 background whose T cells recognize ovalbumin (OVA) peptide presented by I-Ab were a gift from Yang-Xin Fu (University of Chicago). Animals were kept in a biohazard facility and used in agreement with our Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, according to the National Institutes of Health guidelines for animal use.

Bacterial preparations

LM strains LM-wildtype (LM), LM-LLO-, and LM-ActA- were grown in brain-heart infusion broth (BD Biosciences). Log phase cultures of LM were washed twice and diluted in PBS. Titers were determined following optical density adjustment and colony forming unit (cfu) assessment in spleens from infected mice. All mice receiving LM were infected intraperitoneally (i.p.) on the day of transplantation. For infection experiments in MyD88-/- mice or when indicated in wildtype mice, ampicillin (25mg/mouse/day) was administered i.p. for 5 days, starting on day 2 post-transplantation or cefazolin (10mg/mouse) was injected i.p. on the day of transplantation.

Transplantation

Abdominal heterotopic cardiac transplantation was performed using a technique adapted from Corry and colleagues (30). Cardiac allografts were transplanted in the abdominal cavity by anastomosing the aorta and pulmonary artery of the graft end-to-side to the recipient's aorta and vena cava, respectively. Recipient mice were treated with anti-CD154 (MR1; 1mg/dose, i.v. on d0, and i.p. on d7, and d14 post-transplantation) in combination with DST (107 donor splenocytes on the day of transplantation). Some animals received an i.p. injection of different bacterial strains of LM at the indicated doses. For parental LM, an LD50 dose of 5×105 was chosen for subsequent experiments because all transplanted mice survived an injection of 105 cfu, while most died when injected with 106 cfu. Some animals received an i.p. injection of IFN-β (2×104 U on d0 or d0 and d2). The day of rejection was defined as the last day of a detectable heartbeat in the graft. In some animals, depletion of CD8+ T cells was performed by i.v. injection of rat anti-mouse CD8 mAb (YTS-169.4, 1mg/mouse), on day -2 and day -1 prior to transplantation. CD8 depletion was confirmed by flow cytometry on spleen and peripheral blood in pilot experiments.

Full thickness skin grafts (~1 cm2) were obtained from the dorsal flank of OVA transgenic B/c mice, and transplanted onto the dorsal flank of B6 or IFNαR1-/- recipient mice. The recipient mice were treated with anti-CD154 and DST, as described for the heart transplantation experiments.

Detection of donor-specific alloantibodies

Donor-specific alloantibody titers were determined by flow cytometry. Briefly, 1/100 dilution of mouse sera from transplanted mice were incubated with B/c lymph node cells for 1h at 4°C, before the addition of phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-mouse IgM (Jackson Immunoresearch) or fluoresceinconjugated (FITC) anti-mouse IgG (Southern Biotechnology). The geometric mean channel fluorescence (MCF) of the stained samples was determined by flow cytometry and analyzing the binding of antibodies to non-B cells.

IFNγ ELISPOT Assays

Splenocytes (106/well, in triplicate) were stimulated with irradiated (2000 rads) donor (B/c), syngeneic (B6), or third party (C3H/HeJ) splenocytes (5×105/well) for 12 hours. The ELISPOT assay was conducted according to the instructions of the manufacturer (BD Biosciences), and the numbers of spots per well were enumerated using the ImmunoSpot Analyzer (CTL Analyzers LLC).

Immunohistochemistry

Grafts were removed on the day of rejection or day 30 post transplantation for syngeneic grafts, embedded in O.C.T. (Tissue-Tek Miles Inc), and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Cryostat sections were stained with anti-CD4, and anti-CD8, anti-IgG and anti-IgM antibodies as previously described (31).

Colony counting assay

Wildtype B6 mice were infected i.p. with LM (105) or LM-LLO- (5×107) bacteria. Mice were sacrificed on day 2 after infection and spleens were homogenized in PBS. One hundred μg of serially diluted homogenates were plated on BHI agar plates and incubated at 37°C overnight. Bacterial colonies were counted and total number of bacteria/spleen was calculated.

Serum IFN-β and IFN-α

B6, B6/MyD88-/- and B6/IFNαR1-/- mice were infected with LM (105 cfu i.p.). Blood was collected by retro-orbital puncture at the indicated time points and serum isolated and frozen at -20°C for subsequent use. Concentrations of IFN-β and IFN-α were measured by ELISA according to the instructions of the manufacturer (PBL Interferon Source).

OT-II proliferation assays

OT-II cells were prepared by negative selection over magnetic beads (Stem Cell Technologies) from lymph nodes of male Rag-/-/OTII-Tg mice. Stimulator cells were splenocytes isolated from B6 mice that were either naïve or infected 2 days prior with LM (105 bacteria/mouse) in the presence or absence of anti-CD154/DST regimen, as described for transplanted animals. Stimulator cells were prepared by depleting T cells using anti-Thy1.2 mAb and rabbit complement. CFSE (5μM)-labeled OTII cells (106) were mixed with stimulator cells (0.5×106) in the presence or absence of OVA peptide (AA323-339, 1μg/well). Cells were cultured for 5 days, stained with anti-CD4, anti-V2α and anti-Vβ5 (BD PharMingen) to identify OTII cells and analyzed by flow cytometry. Transfer of live LM organisms from infected splenocytes to the culture dishes was excluded, as we verified that the concentration of penicillin/streptomycin contained in our standard culture medium effectively killed LM (data not shown).

Statistical Methods

Comparisons of means were performed using the two-tailed Student's t test or ANOVA and the post-hoc Tukey test for multiple comparisons, when appropriate. Graft mean survival time (MST) and p-values were calculated using Kaplan-Meier/log rank test methods.

Results

LM infection prevents allograft acceptance in recipients treated with anti-CD154/DST

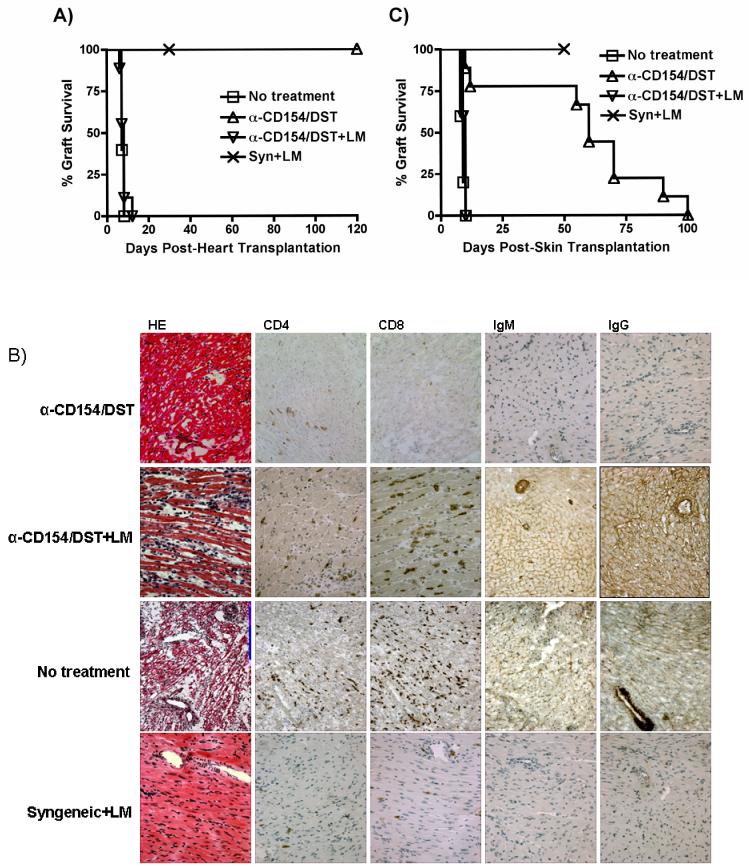

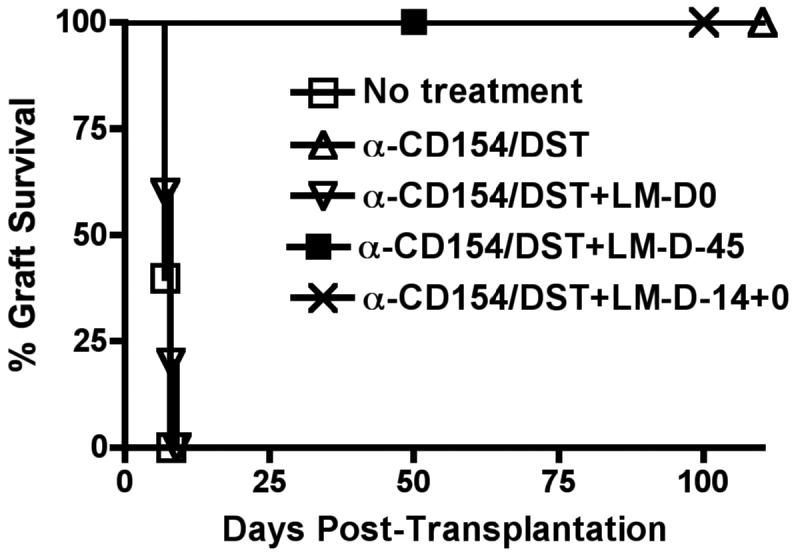

To test whether bacterial infection prevents the induction of allograft tolerance, we used a fully mismatched model of heterotopic heart transplantation with B/c mice (H-2d) as donors and B6 mice (H-2b) as recipients. Tolerance was induced by administration of anti-CD154 and DST. An i.p. injection of LM (105/mouse) on the day of transplantation prevented anti-CD154/DST-mediated graft acceptance, with all the grafts being rejected within 10 days (Figure 1A). Comparable results were also observed with B/c recipients of B6 heart grafts treated with anti-CD154/DST and infected with LM (data not shown). LM infection did not affect the survival of syngeneic heart grafts, demonstrating that LM infection did not interfere with wound healing, and suggesting that the effect of LM infection in anti-CD154/DST-treated recipients was due to an alteration in the alloimmune response. Histological and immunohistochemical analysis of grafts from untreated and LM-infected mice revealed infiltration by CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and IgM/IgG deposition consistent with acute rejection in allografts but not syngeneic grafts (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. LM infection prevents anti-CD154/DST-mediated allograft acceptance.

(A) LM infection prevents anti-CD154/DST-mediated cardiac allograft acceptance. B6 recipients of B/c heterotopic heart grafts were left untreated (n=5) or were treated with anti-CD154 (1mg/mouse on days 0, 7 and 14 post-transplantation) and DST (5×106 splenocytes, i.v. on the day of transplantation) in the absence (n=6) or presence (n=8) of an infection with LM (105 cfu i.p. on the day of transplantation). Recipients of syngeneic hearts were untreated but received the same dose of LM as the anti-CD154/DST groups (n=4). p<0.01 for anti-CD154/DST vs no treatment; p<0.001 for anti-CD154/DST vs anti-CD154/DST+LM. (B) Histology and immunohistochemistry of cardiac allografts isolated at the time of rejection from an untreated mouse and from mice treated with anti-CD154/DST and anti-CD154/DST+LM, as well as from a syngeneic graft harvested on day 30 from a mouse infected with LM. Cellular infiltration of CD4+ and CD8+ cells is observed, as well as alloantibody deposition, in rejecting but not syngeneic grafts. This result is representative of 3 allografts analyzed/group (magnification 200X). (C) LM infection prevents anti-CD154/DST-mediated skin allograft acceptance. B6 mice were transplanted with B/c or B6 skin and treated as indicated (no treatment, n=5; anti-CD154/DST, n=8; anti-CD154/DST+LM, n=5; syngeneic+LM, n=5). Skin grafts were considered rejected when fully scabbed and necrotic. p<0.001 for anti-CD154/DST vs no treatment and vs anti-CD154/DST+LM.

Similar experiments were performed using skin grafts from B/c mice transplanted into B6 recipients. In this case, administration of anti-CD154/DST results in long-term acceptance of skin allografts but not in transplantation tolerance and skin grafts are eventually rejected between days 50 and 100 (Figure 1C). LM infection at the time of transplantation completely abrogated the ability of anti-CD154/DST to prolong skin graft survival.

LM infection restores alloreactive B and T cells responses in recipients treated with anti-CD154/DST

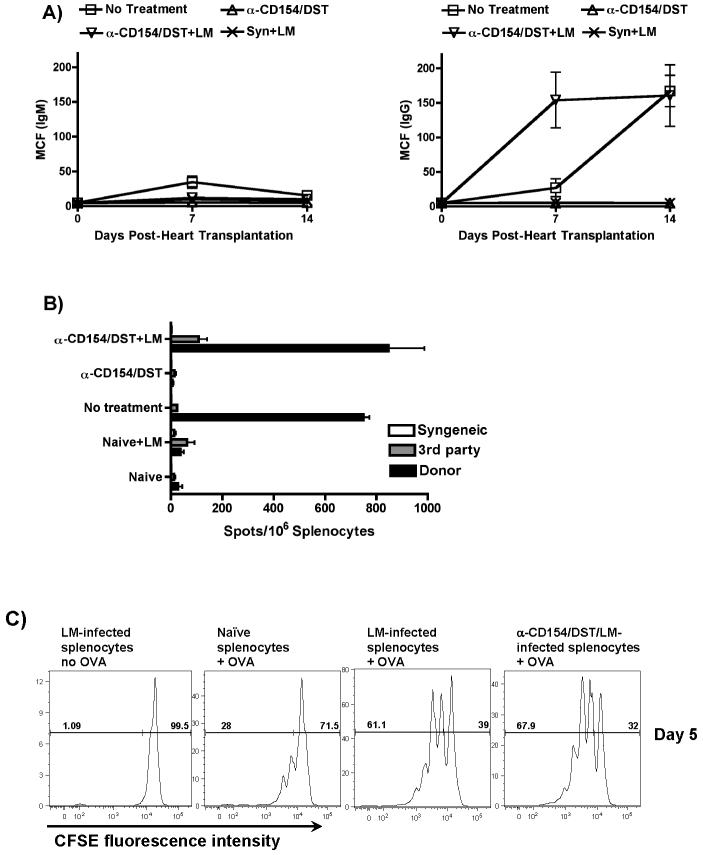

LM-mediated rejection correlated with elevated serum levels of donor-specific IgG but not IgM antibodies (Figure 2A), suggesting that alloreactive T helper and B cell responses were restored in anti-CD154/DST-treated recipients by LM infection. The absence of detectable circulating allo-IgM but presence in the allograft (Figure 1B) may be due to the ability of LM infections to enhance class-switching from IgM to IgG. Primed donor-specific IFN-γ-producing cells were detected in the spleen of LM-infected anti-CD154/DST-treated recipients of cardiac allografts (Figure 2B). LM-mediated rejection of skin allografts also correlated with an increased frequency of donor-specific IFN-γ-producing splenocytes (data not shown). Together, these data are supportive of LM infection overriding the immunosuppressive activity of anti-CD154/DST and resulting in enhanced donor-specific immune responses.

Figure 2. LM infection restores B and T cell alloreactivity in anti-CD154/DST-treated recipients.

(A) Restoration of allo-IgG responses. Serum from transplanted mice was collected at the indicated time points and concentrations of allo-reactive IgM and IgG antibodies was determined by flow cytometry. Results represent the mean and standard deviation of 4 determinations per group. p<0.05 for Allo+anti-CD154/DST+LM vs no treatment, vs Syn+LM and vs Allo+anti-CD154/DST. (B) Restoration of primed allo-specific IFN-γ-producing cells. Splenocytes from transplanted or naïve mice treated as indicated were isolated 2-3 weeks post transplantation and stimulated with syngeneic (B6), donor (B/c) or third party (C3H/HEJ) irradiated splenocytes. The frequency of IFN-γ-producing cells was analyzed as indicated in the Materials and Methods. Results represent the mean and standard deviation of 4 determinations per group. p<0.001 for Allo+anti-CD154/DST+LM vs Allo+anti-CD154/DST, vs naïve+LM and vs naïve; not significant vs no treatment. (C) LM infection results in increased APC capacity to prime T cells. B6 mice were infected with LM and either untreated or treated with anti-CD154/DST. The splenocytes were isolated 48h after infection and depleted of T cells using anti-Th1.2 mAb and rabbit complement. T cell-depleted splenocytes either unpulsed or pulsed with OVA peptide were used to stimulate CFSE-labeled OVA-specific B6/RAG1-/-/OTII-Tg T cells that had been enriched by negative selection over magnetic beads. Cultures were harvested after 5 days and analyzed by flow cytometry. Results represent CFSE fluorescence intensity of CD4+/Vα2+ cells and are representative of 3 independent experiments. p<0.01 for LM-infected+OVA and LM-infected/anti-CD154/DST+OVA vs naïve+OVA.

We hypothesized that LM infection promoted APC maturation/activation, which in turn resulted in enhanced stimulation of alloreactive T cells. Using antigen-specific T cells, splenocytes from control, LM-infected or LM-infected and anti-CD154/DST-treated mice were isolated 48h post-infection, T-depleted, irradiated, pulsed with OVA peptide and used to stimulate CFSE-labeled syngeneic naïve OTII-Tg OVA-specific T cells for 5 days. As shown in Figure 2C, OTII T cells proliferated more vigorously to OVA presented by splenocytes from LM-infected mice, whether initially immunosuppressed with anti-CD154/DST or not, compared to splenocytes from control uninfected mice. These data are consistent with the conclusion that splenocytes from LM-infected mice have a greater antigen-presentation capacity than control splenocytes which resulted in enhanced T cell priming in LM-infected animals. Consistent with this hypothesis, we observed statistically significant increases in expression levels of CD80 and CD86 but not MHC class II in CD11c+ dendritic cells from LM-infected mice (data not shown).

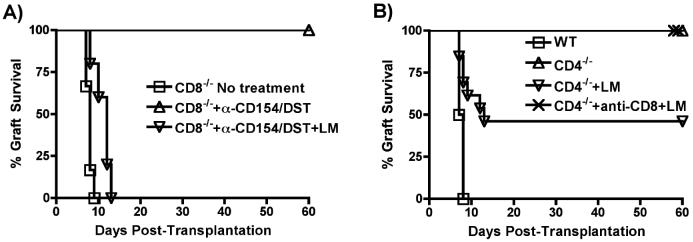

CD4+ or CD8+ T cells can mediate allograft rejection in LM-infected recipients

To determine whether LM-triggered rejection was T cell-mediated, CD8-/- and CD4-/- mice were utilized. CD8-/- mice rejected B/c heart grafts at a rate comparable to wildtype mice, while treatment with anti-CD154/DST resulted in long-term graft survival for >60 days. LM infection in anti-CD154/DST-treated CD8-/- mice resulted in acute rejection (Figure 3A), associated with an increased frequency of donor-specific IFNγ-producing T cells and elevated alloantibody titers (data not shown). Thus, LM-induced rejection in anti-CD154/DST treated recipients is not dependent on the presence of alloreactive CD8+ cells.

Figure 3. CD4+ or CD8+ T cells can mediate allograft rejection in LM-infected recipients.

(A) B6/CD8-/- mice were transplanted with BALB/c hearts and treated as described for Figure 1 (n=5 mice/group). p,0.01 for CD8-/-+anti-CD154/DST vs no treatment and vs CD8-/-+anti-CD154/DST+LM. (B) B6/CD4-/- mice were used as recipients of B/c hearts. Mice were left untreated, or infected with LM. In one group, CD8+ cells were depleted with anti-CD8 mAb (n=4-5 mice/group). p<0.01 for wildtype (WT) vs CD4-/-, vs CD4-/-+anti-CD8+LM and vs CD4-/-+LM; p<0.05 for CD4-/-+LM vs CD4-/- and vs CD4-/-+anti-CD8+LM.

As previously described, CD4-/- mice spontaneously accepted B/c heart allografts (31). LM infection resulted in acute rejection in 60% of CD4-/- recipients of cardiac allografts (Figure 3B). To confirm that the rejection in LM-infected CD4-/- mice was due to activated CD8 cells, CD4-/- recipients were depleted of CD8+ cells (Figure 3B). In the absence of CD4+ and CD8+ cells, none of the LM-infected recipients rejected their grafts. Together, these results demonstrate that rejection of the allografts in LM infected recipients can be mediated by either CD4+ or CD8+ T cells and that LM infection renders alloreactive CD4+ T cells resistant to the immunosuppressive effects of anti-CD154/DST, and the activation of CD8+ T cells largely independent of CD4+ T cells.

The ability of LM infection to prevent transplantation tolerance is not due to the stimulation of cross-reactive T cells

Previous studies demonstrating the ability of lymphocytic choriomeningitis (LCMV) and pichinde, but not murine cytomegalovirus and vaccinia, viral infections to prevent the induction of tolerance (7, 11, 12) have led to the suggestion that the acquired resistance to tolerance is due to generation of cross-reactive memory T cells co-recognizing viral peptides and alloantigens. To test whether LM's ability to prevent the induction of tolerance is due to LM-specific T cells cross-reacting with alloantigen, we tested whether prior generation of anti-LM memory responses resulted in resistance to subsequent transplantation tolerance. Recipients pre-immunized with live LM two weeks before heart transplantation successfully accepted cardiac allografts when treated with anti-CD154/DST, even if they were re-infected with LM at the time of heart transplantation and anti-CD154/DST treatment (Figure 4). This indicates both successful generation of protective anti-LM immune responses (as otherwise peri-transplant LM infection would have prevented transplantation tolerance) and insufficient generation of cross-reacting allospecific memory T cell responses to mediate allograft rejection. Similarly, infection with LM seven weeks before transplantation, to ensure more time for the development of memory responses, did not prevent the ability of anti-CD154/DST to induce transplantation tolerance (Figure 4). Together, these data suggest that generation of cross-reactive allospecific T cell responses is not the mechanism by which LM prevents transplantation tolerance.

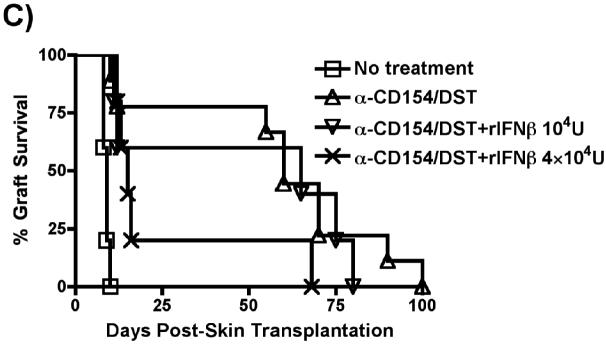

Figure 4. The ability of LM infection to prevent transplantation tolerance is not due to the stimulation of cross-reactive T cells.

B6 mice were infected with LM only on day -45 (n=5), or on days -14 and +0 (n=4), or only on day +0 (n=7) relative to transplantation with B/c hearts and initiation of the anti-CD154/DST treatments. p<0.001 for no treatment vs anti-CD154/DST, vs anti-CD154/DST+LM-D-45 and vs anti-CD154/DST+LM-D-14+0.

LLO but not ActA expression is required for LM to prevent transplantation tolerance

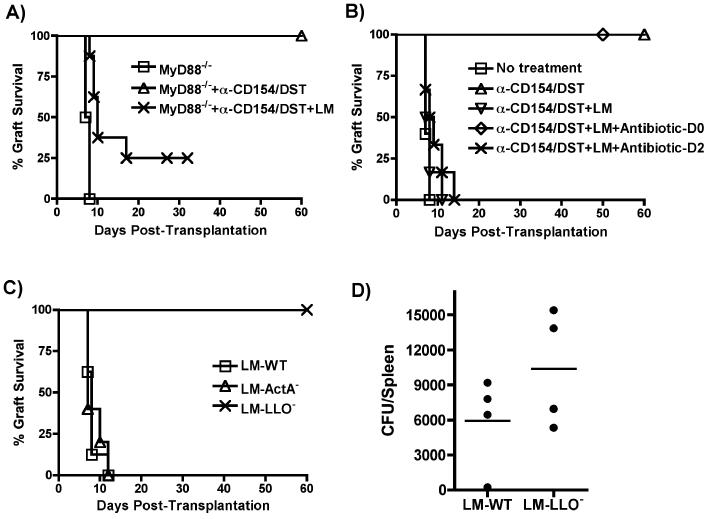

We next focused on the features of LM that conferred its ability to trigger acute allograft rejection despite treatment with anti-CD154/DST. Common molecular patterns expressed by LM can potentially engage various TLRs and several immune responses elicited by LM are dependent on expression in host cells of the TLR adaptor MyD88 (22). The pro-rejection effect of live LM was mostly independent of MyD88-mediated signaling as LM infection induced acute rejection in the majority of anti-CD154/DST-treated B6/MyD88-/- recipients of B/c/MyD88-/- allografts (Figure 5A).

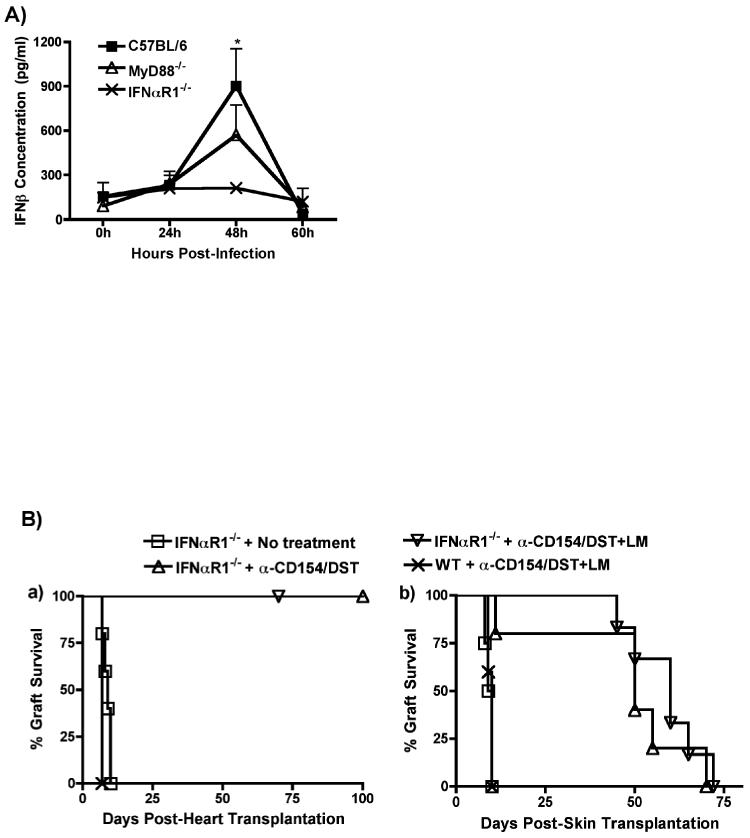

Figure 5. Mechanisms of acute rejection by LM.

(A) B6/MyD88-/- recipients of B/c/MyD88-/- hearts were treated as in Figure 1 (untreated, n=3; anti-CD154/DST, n=6; anti-CD154/DST+LM, n=10). p<0.01 for MyD88-/- vs MyD88-/-+anti-CD154/DST+LM and vs MyD88-/-+anti-CD154/DST; p<0.01 for MyD88+anti-CD154/DST vs MyD88-/-+anti-CD154/DST+LM. (B) B6 recipients of B/c cardiac allografts were treated as in Figure 1. Some groups received ampicillin (Amp, 25 mg/mouse for 5 days) or cephazolin (10 mg/mouse) starting on the day of LM infection (n=6) or 2 days later (n=6). p<0.001 for WT+anti-CD154/DST vs WT+anti-CD154/DST+LM and vs WT+anti-CD154/DST+LM+antibiotic-D2. (C) LM (105 cfu, n=7), ActA-deficient LM (LM-Act-, 107 cfu, n=5), or LLO-deficient LM (LM-LLO-, 5×107 cfu, n=9) were used on the day of transplantation to infect B6 recipients of B/c hearts treated with anti-CD154/DST as for Figure 1. p<0.001 for LM-LLO- vs LM-WT and vs LM-ActA-. (D) Number of LM-WT and LM-LLO- bacteria recovered from the spleen 2 days after infection (n=4/group), as described in Materials and Methods. p=0.2096, not significant.

We observed that live bacteria needed to be present for only a short time after transplantation, as treatment with high doses of the anti-LM antibiotic ampicillin on day 0 but not day 2 [as performed by others to isolate early molecular events triggered by LM (32)] post infection and transplantation prevented LM-induced allograft rejection (Figure 5B). These observations suggest that early events of LM infection, including LLO-dependent escape from the phagosome and cytosolic invasion, as well as ActA-dependent infection of neighboring cells by LM, may be critical. To test whether cellular invasion by live LM was necessary for the inhibition of tolerance induction, LLO-deficient and ActA-deficient LM strains were utilized. Whereas maximally tolerated numbers of ActA-deficient bacteria (107 cfu) were as effective as parental LM at preventing anti-CD154/DST-mediated transplantation tolerance, LLO-deficient bacteria even at high titers (5×107) were unable to inhibit transplantation tolerance (Figure 5C). The failure of LLO-deficient LM to promote acute rejection was not due to its inability to replicate to sufficient bacterial titers, as splenic bacterial counts in mice infected with LLO-deficient (5×107) and parental (105) LM were similar on day 2 post-infection (Figure 5D), a time after which the elimination of LM with ampicillin has no effect on graft outcome (Figure 5B).

Prevention of tolerance by LM infection is mediated by Type I IFNs

The LLO-mediated phagosomal lysis and cytosolic propagation by LM is known to result in IFN-β production by infected cells, in a MyD88-independent manner (26). To test for the role of type I IFN in the rejection process, we first analyzed the kinetics of production of IFN-β and IFN-α following LM infection. As shown in Figure 6A, LM infection resulted in increased serum levels of IFN-β that peaked at 48h after infection and were similar in wildtype and MyD88-/- mice, confirming previous reports that IFN-β production by LM is MyD88-independent (25). IFN-β serum levels were not increased in LM-infected IFNαR1-/- mice (Figure 6A), consistent with the notion that IFNα signaling provides an amplification loop for type I IFN production (33). In contrast to IFN-β, LM infection did not result in detectable serum levels of IFN-α in any of these 3 mouse strains (data not shown). These data reveal a correlation between rejection and the production of IFN-β by LM-infected mice.

Figure 6. Prevention of tolerance by LM infection is mediated by Type I IFNs.

(A) In vivo production of IFN-β by B6, B6/MyD88-/- and B6/IFNαR1-/- mice infected with LM (105 cfu). Animals were bled at the indicated time points and the concentration of serum IFN-β was measured by ELISA. *p<0.05 between serum from LM-infected B6 mice at 48h and all other time points and with serum from LM-infected IFNαR1-/- mice at 48h. (B) Prevention of tolerance by LM infection is dependent on Type I IFNs. B6/IFNαR1-/- mice were used as recipients of B/c heart (Left Panel) or skin (Right Panel) allografts. Mice were left untreated or were treated with anti-CD154/DST or with anti-CD154/DST/LM (n=4-6 mice in all groups). (Left Panel) p<0.05 for IFNαR1-/-+anti-CD154/DST+LM vs IFNαR1-/- no treatment and WT+anti-CD154/DST+LM. (Right Panel) p<0.01 for IFNRαR1-/-+no treatment vs IFNRαR1-/-+anti-CD154/DST and +anti-CD154/DST+LM. (C) IFN-β is sufficient to prevent anti-CD154/DST-mediated graft survival. B6 mice were transplanted with B/c skin and left untreated or treated with anti-CD154/DST. Two groups of mice received i.p. injections of IFN-β (104U on day 0, n=5 or 2×104 U/mouse on days 0 and 2 post-transplant, n=5). P<0.05 between IFN-β-treated and anti-CD154/DST alone groups.

To test whether the pro-rejection effect of LM was dependent on type I IFN signaling, we used IFNα1-/- B6 mice as recipients of B/c heart and skin transplants. Anti-CD154/DST induced similar prolongation of heart and skin allograft survival in IFNα1-/- and wildtype B6 animals (Figure 6B). Whereas LM infection prevented anti-CD154/DST-mediated prolongation of heart and skin allograft survival in wildtype recipients (Figures 1A and 1C), administration of LM to IFNα1-/- mice failed to prevent anti-CD154/DST-mediated long-term graft acceptance of both heart (Figure 6B, Left Panel) and skin allografts (Figure 6B, Right Panel). These results indicate that type I IFN signaling is necessary for LM infection to induce acute rejection.

Finally, we demonstrate that the administration of IFN-β, in a dose-dependent manner, was sufficient to prevent anti-CD154/DST-mediated prolongation of skin allograft survival (Figure 6C). Together, these experiments show a correlation between LM-induced IFN-β production and prevention of allograft acceptance, necessity of IFNα1 signaling for LM to prevent anti-CD154/DST-induced graft survival and sufficiency of type I IFN to prevent anti-CD154/DST-mediated graft survival, thus fulfilling Koch's postulate for a role of type I IFN in the prevention of allograft acceptance.

Discussion

Our results show that infection with the intracellular Gram-positive bacterium LM at the time of transplantation prevents cardiac transplant tolerance and long-term skin allograft acceptance induced by anti-CD154/DST. LM-mediated acute graft rejection is dependent on its expression of LLO and on type I IFN signaling, but mostly independent of MyD88 expression. Our data suggest that live LM infection results in the activation of APCs that promote the stimulation of alloreactive T cells rather than activation of T cells cross-reactive to LM and alloantigen.

We and others have previously shown that the administration of single TLR agonists can prevent the induction of cardiac transplantation tolerance or of long-term skin allograft acceptance by anti-CD154/DST (15-17). However, several pieces of evidence indicate that the mechanisms by which TLR ligands and LM prevent transplantation tolerance can be distinct. First, the kinetics of acute rejection induced by TLR ligands are slower than those triggered by LM. In fact, TLR-induced acute rejection of cardiac allografts did not occur until discontinuation of the anti-CD154 therapy on day 21 post transplantation (15). In contrast, LM infection completely eliminated the protective effects of anti-CD154/DST resulting in similar rejection kinetics as those in untreated animals. This suggests more a vigorous enhancement of adaptive immune responses by LM compared to TLR agonists. Additionally, whereas cardiac allograft rejection following injection of CpG in anti-CD154/DST- treated mice is dependent on MyD88 (unpublished results), LM-driven acute rejection could proceed largely independently of MyD88 expression. This result is consistent with the demonstration that CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses to LM can be elicited independently of TLR2, TLR4 and MyD88 (32). Similarly in our study, the enhancement of allogeneic T cell responses and antagonism of transplantation tolerance by LM is mostly independent of MyD88. Because LM may also trigger signals dependent on other receptors for microbial molecular patterns (22), it is conceivable that non-MyD88-dependent receptors mediate signals playing a role in LM's ability to prevent transplantation tolerance.

Anti-CD154-mediated immunosuppression has been shown to operate via different mechanisms, including inhibition of T cell activation, induction of T cell anergy, facilitation of deletion of alloreactive T cells and promotion of donor-specific regulation (34). The latter has been ascribed to both conversion of conventional T cells into FoxP3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) (35), and chemokine-driven recruitment of Tregs into cardiac allografts from tolerant animals (36). We have shown that CpG-mediated rejection coincides with reduced anti-CD154-induced recruitment of Tregs into cardiac allografts, perhaps because of decreased expression of CCL17 (TARC) and CCL22 (MDC), two chemokines that attract CCR4-expressing cells (15). Because CCR4 is preferentially expressed on Tregs (36), a reduction of intra-graft CCL17 and CCL22 in CpG-treated recipients results in an increased ratio of effector T cells to Tregs in the graft (15). This supports a hypothesis of reduced suppression by Tregs of effector responses within the allograft, leading to acute rejection. The rapid rejection kinetics induced by LM is incompatible with a similar mechanism of prevention of tolerance. Indeed, LM-induced rejection occurs within the first ten days after transplantation, a time point prior to recruitment of Tregs into cardiac allografts in anti-CD154-treated animals. Therefore, acute rejection induced by LM is unlikely to be due to reduced Treg recruitment to cardiac allografts. Instead, our results support a model in which increased activation of alloreactive T cells results in escape from suppression by Tregs at the priming rather than at the effector stage of the response. Whether LM infection also prevents conversion of conventional T cells into Tregs remains to be investigated.

The pro-rejection effect of LM is dependent on expression of LLO, a pore-former molecule that is specific to LM, and that is necessary for the cytosolic invasion and subsequent production of type I IFNs. Indeed, our results indicate that LM-mediated acute rejection depends on IFNαR1 expression and that exogenous IFN-β can prevent the induction of transplantation tolerance.

The interplay between type I IFN signaling and tolerance is becoming recognized in the autoimmunity field as evidence suggests that type I IFNs may interfere with tolerance and promote autoimmunity both in experimental models and in the clinic. In NOD mice, IFN-β accelerates autoimmune diabetes and breaks the tolerance to b cells in non diabetes-prone mice (37). In humans, increased serum levels of type I IFNs have been described in lupus patients, where type I IFN signaling is thought to promote maturation of DCs, resulting in enhanced T cell activation (38). Finally, increase circulating levels of type I IFNs, and polymorphisms in the type I IFN pathway are associated with systemic lupus erythematosus disease susceptibility (39).

The consequences of IFNα/β signaling in transplantation are less well established. Type I IFN-mediated signaling appears to play a major role in ischemia/reperfusion injury (IRI) (40, 41). Recently, type I IFNs have been reported to mediate the prevention of skin allograft acceptance by LPS and poly I:C by reducing the deletion of alloreactive CD8+ T cells necessary for graft acceptance (42). We have extended these findings to a microbial infection and demonstrate a correlation between LM-induced IFN-β production and prevention of allograft acceptance, the necessity of IFNαR1 signaling for LM to prevent anti-CD154/DST-induced graft survival and sufficiency of type I IFN to prevent anti-CD154/DST-mediated graft survival. These data taken together support the hypothesis that Listeria infections prevent long-term allograft survival mediated by anti-CD154 through the secretion of IFN-β.

LM infection also enhanced the ability of splenic APCs to present antigen to naïve T cells in vitro, and enhanced antigen-specific differentiation/effector function as determined by the augmented production of IFN-γ by alloreactive T cells and the restored allo-IgG response. These results are consistent with known properties of type I IFNs, which induce upregulation of B7 costimulatory molecules (43) and facilitate the expansion and survival of T cells (44, 45). Furthermore, the production of type I IFN after LM infection has been reported to enhance the capacity of CD4+ T cells to produce IFN-γ (46). Several cell types have been shown to produce IFN-β after LM infection, including NK cells, DCs and macrophages (47, 48). The specific cell types producing IFN-β in LM-infected recipients of cardiac allografts remains to be elucidated.

In summary, our results point to type I IFNs as interesting potential targets for facilitating transplantation tolerance. Type I IFNs can be induced by many viral and bacterial infections (49) and can occur downstream of MD88-dependent and -independent events (50, 51). We therefore speculate that infections occurring during the peri-operative period that are capable of inducing Type I IFNs may be capable of enhancing alloreactivity and preventing transplantation tolerance. IFN-a was the first biotherapeutic drug to be approved for clinical use and type I IFNs are routinely employed for the treatment of hepatitis B and C and of multiple sclerosis (52-54). This use of type I IFNs has been reported to precipitate episodes of acute rejection (55, 56). Our results prompt the speculation that such treatments in transplant recipients may additionally antagonize transplantation tolerance. Finally, our data draw attention to an important potential impact of peri-operative bacterial infections in transplanted patients and their impending interference with the induction of transplantation tolerance or the long-term acceptance of allografts. Of note are our preliminary observations that injection of Staphylococcus aureus also prevents anti-CD154/DST-mediated acceptance of skin allografts (Ahmed et al, manuscript in preparation). However, the mechanisms by which this is accomplished appear to be distinct from those of LM infection. Thus investigations into the impact of infections on the induction of transplantation tolerance are likely to identify new approaches that facilitate the induction of tolerance.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Drs. Akira, Bendelac and Fu for generously providing us with genetically altered animals.

This work is supported by grants from American Heart Association Fellowship #0620026Z to LC, NIH RO1-AI052352-01 to MLA, NIH R01 AI072630 and ROTRF #280559271 to ASC and a AST Branch-Out Faculty Grant to ASC and CRW.

Glossary

Abbrevations

- ActA

actin assembly-inducing protein

- DST

donor-specific transfusion

- LLO

listeriolysin O

- LM

Listeria monocytogenes

- TLR

toll-like receptor

References

- 1.Reinke P, Fietze E, Ode-Hakim S, Prosch S, Lippert J, Ewert R, Volk HD. Late-acute renal allograft rejection and symptomless cytomegalovirus infection. Lancet. 1994;344:1737–1738. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92887-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McLaughlin K, Wu C, Fick G, Muirhead N, Hollomby D, Jevnikar A. Cytomegalovirus seromismatching increases the risk of acute renal allograft rejection. Transplantation. 2002;74:813–816. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200209270-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sageda S, Nordal KP, Hartmann A, Sund S, Scott H, Degre M, Foss A, Leivestad T, Osnes K, Fauchald P, Rollag H. The impact of cytomegalovirus infection and disease on rejection episodes in renal allograft recipients. Am J Transplant. 2002;2:850–856. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2002.20907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vilchez RA, Dauber J, McCurry K, Iacono A, Kusne S. Parainfluenza virus infection in adult lung transplant recipients: an emergent clinical syndrome with implications on allograft function. Am J Transplant. 2003;3:116–120. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2003.00024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pantenburg B, Heinzel F, Das L, Heeger PS, Valujskikh A. T cells primed by Leishmania major infection cross-react with alloantigens and alter the course of allograft rejection. J Immunol. 2002;169:3686–3693. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.7.3686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adams AB, Pearson TC, Larsen CP. Heterologous immunity: an overlooked barrier to tolerance. Immunol Rev. 2003;196:147–160. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-065x.2003.00082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brehm MA, Markees TG, Daniels KA, Greiner DL, Rossini AA, Welsh RM. Direct visualization of cross-reactive effector and memory allo-specific CD8 T cells generated in response to viral infections. J Immunol. 2003;170:4077–4086. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.8.4077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valujskikh A, Pantenburg B, Heeger PS. Primed allospecific T cells prevent the effects of costimulatory blockade on prolonged cardiac allograft survival in mice. Am J Transplant. 2002;2:501–509. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2002.20603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adams AB, Williams MA, Jones TR, Shirasugi N, Durham MM, Kaech SM, Wherry EJ, Onami T, Lanier JG, Kokko KE, Pearson TC, Ahmed R, Larsen CP. Heterologous immunity provides a potent barrier to transplantation tolerance. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1887–1895. doi: 10.1172/JCI17477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hudrisier D, Riond J, Burlet-Schiltz O, von Herrath MG, Lewicki H, Monsarrat B, Oldstone MB, Gairin JE. Structural and functional identification of major histocompatibility complex class I-restricted self-peptides as naturally occurring molecular mimics of viral antigens. Possible role in CD8+ T cell-mediated, virus-induced autoimmune disease. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:19396–19403. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008864200. Epub 12001 Mar 19398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Welsh RM, Markees TG, Woda BA, Daniels KA, Brehm MA, Mordes JP, Greiner DL, Rossini AA. Virus-induced abrogation of transplantation tolerance induced by donor-specific transfusion and anti-CD154 antibody. J Virol. 2000;74:2210–2218. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.5.2210-2218.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Welsh RM, McNally JM, Brehm MA, Selin LK. Consequences of cross-reactive and bystander CTL responses during viral infections. Virology. 2000;270:4–8. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams MA, Tan JT, Adams AB, Durham MM, Shirasugi N, Whitmire JK, Harrington LE, Ahmed R, Pearson TC, Larsen CP. Characterization of virus-mediated inhibition of mixed chimerism and allospecific tolerance. J Immunol. 2001;167:4987–4995. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.4987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams MA, Onami TM, Adams AB, Durham MM, Pearson TC, Ahmed R, Larsen CP. Cutting edge: persistent viral infection prevents tolerance induction and escapes immune control following CD28/CD40 blockade-based regimen. J Immunol. 2002;169:5387–5391. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.10.5387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen L, Wang T, Molinero L, Shen J, Phillips T, Akira S, Fairchild RL, Alegre ML, Chong A. TLR signaling prevents transplantation tolerance. Am J Transplant. 2006 doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01489.x. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thornley TB, Brehm MA, Markees TG, Shultz LD, Mordes JP, Welsh RM, Rossini AA, Greiner DL. TLR Agonists Abrogate Costimulation Blockade-Induced Prolongation of Skin Allografts. J Immunol. 2006;176:1561–1570. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.3.1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walker WE, Nasr IW, Camirand G, Tesar BM, Booth CJ, Goldstein DR. Absence of innate MyD88 signaling promotes inducible allograft acceptance. J Immunol. 2006;177:5307–5316. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.8.5307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gangappa S, Larsen CP, Pearson TC. Alloimmunity: no toll exemption. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:3–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Villacian JS, Paya CV. Prevention of infections in solid organ transplant recipients. Transpl Infect Dis. 1999;1:50–64. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3062.1999.10106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Afessa B, Peters SG. Major complications following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;27:297–309. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-945530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Danziger-Isakov LA, Sweet S, Delamorena M, Huddleston CB, Mendeloff E, Debaun MR. Epidemiology of bloodstream infections in the first year after pediatric lung transplantation. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24:324–330. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000157089.42020.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pamer EG. Immune responses to Listeria monocytogenes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:812–823. doi: 10.1038/nri1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patel R, Paya CV. Infections in solid-organ transplant recipients. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:86–124. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.1.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fishman JA, Rubin RH. Infection in organ-transplant recipients. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1741–1751. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199806113382407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Connell RM, Vaidya SA, Perry AK, Saha SK, Dempsey PW, Cheng G. Immune activation of type I IFNs by Listeria monocytogenes occurs independently of TLR4, TLR2, and receptor interacting protein 2 but involves TNFR-associated NF kappa B kinase-binding kinase 1. J Immunol. 2005;174:1602–1607. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.3.1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Serbina NV, Kuziel W, Flavell R, Akira S, Rollins B, Pamer EG. Sequential MyD88-independent and -dependent activation of innate immune responses to intracellular bacterial infection. Immunity. 2003;19:891–901. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00330-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Belz GT, Shortman K, Bevan MJ, Heath WR. CD8alpha+ dendritic cells selectively present MHC class I-restricted noncytolytic viral and intracellular bacterial antigens in vivo. J Immunol. 2005;175:196–200. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.1.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Badovinac VP, Messingham KA, Jabbari A, Haring JS, Harty JT. Accelerated CD8+ T-cell memory and prime-boost response after dendritic-cell vaccination. Nat Med. 2005;11:748–756. doi: 10.1038/nm1257. Epub 2005 Jun 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adachi O, Kawai T, Takeda K, Matsumoto M, Tsutsui H, Sakagami M, Nakanishi K, Akira S. Targeted disruption of the MyD88 gene results in loss of IL-1- and IL-18-mediated function. Immunity. 1998;9:143–150. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80596-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Corry RJ, Winn HJ, Russell PS. Primarily vascularized allografts of hearts in mice. The role of H-2D, H-2K, and non-H-2 antigens in rejection. Transplantation. 1973;16:343–350. doi: 10.1097/00007890-197310000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Szot GL, Zhou P, Rulifson I, Wang J, Guo Z, Kim O, Newel KA, Thistlethwaite JR, Bluestone JA, Alegre ML. Different mechanisms of cardiac allograft rejection in wildtype and CD28-deficient mice. Am J Transplant. 2001;1:38–46. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2001.010108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kursar M, Mittrucker HW, Koch M, Kohler A, Herma M, Kaufmann SH. Protective T cell response against intracellular pathogens in the absence of Toll-like receptor signaling via myeloid differentiation factor 88. Int Immunol. 2004;16:415–421. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takaoka A, Taniguchi T. New aspects of IFN-alpha/beta signalling in immunity, oncogenesis and bone metabolism. Cancer Sci. 2003;94:405–411. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01455.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alegre ML, Najafian N. Costimulatory molecules as targets for the induction of transplantation tolerance. Curr Mol Med. 2006;6:843–857. doi: 10.2174/156652406779010812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ochando JC, Homma C, Yang Y, Hidalgo A, Garin A, Tacke F, Angeli V, Li Y, Boros P, Ding Y, Jessberger R, Trinchieri G, Lira SA, Randolph GJ, Bromberg JS. Alloantigen-presenting plasmacytoid dendritic cells mediate tolerance to vascularized grafts. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:652–662. doi: 10.1038/ni1333. Epub 2006 Apr 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee I, Wang L, Wells AD, Dorf ME, Ozkaynak E, Hancock WW. Recruitment of Foxp3+ T regulatory cells mediating allograft tolerance depends on the CCR4 chemokine receptor. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1037–1044. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alba A, Puertas MC, Carrillo J, Planas R, Ampudia R, Pastor X, Bosch F, Pujol-Borrell R, Verdaguer J, Vives-Pi M. IFN beta accelerates autoimmune type 1 diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice and breaks the tolerance to beta cells in nondiabetes-prone mice. J Immunol. 2004;173:6667–6675. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.11.6667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Banchereau J, Pascual V. Type I interferon in systemic lupus erythematosus and other autoimmune diseases. Immunity. 2006;25:383–392. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kyogoku C, Tsuchiya N. A compass that points to lupus: genetic studies on type I interferon pathway. Genes Immun. 2007;21:21. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhai Y, Shen XD, O'Connell R, Gao F, Lassman C, Busuttil RW, Cheng G, Kupiec-Weglinski JW. Cutting edge: TLR4 activation mediates liver ischemia/reperfusion inflammatory response via IFN regulatory factor 3-dependent MyD88-independent pathway. J Immunol. 2004;173:7115–7119. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.12.7115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsuchihashi S, Zhai Y, Bo Q, Busuttil RW, Kupiec-Weglinski JW. Heme oxygenase-1 mediated cytoprotection against liver ischemia and reperfusion injury: inhibition of type-1 interferon signaling. Transplantation. 2007;83:1628–1634. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000266917.39958.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thornley TB, Phillips NE, Beaudette-Zlatanova BC, Markees TG, Bahl K, Brehm MA, Shultz LD, Kurt-Jones EA, Mordes JP, Welsh RM, Rossini AA, Greiner DL. Type 1 IFN mediates cross-talk between innate and adaptive immunity that abrogates transplantation tolerance. J Immunol. 2007;179:6620–6629. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.10.6620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cho HJ, Hayashi T, Datta SK, Takabayashi K, Van Uden JH, Horner A, Corr M, Raz E. IFN-alpha beta promote priming of antigen-specific CD8+ and CD4+ T lymphocytes by immunostimulatory DNA-based vaccines. J Immunol. 2002;168:4907–4913. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.10.4907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ahonen CL, Doxsee CL, McGurran SM, Riter TR, Wade WF, Barth RJ, Vasilakos JP, Noelle RJ, Kedl RM. Combined TLR and CD40 triggering induces potent CD8+ T cell expansion with variable dependence on type I IFN. J Exp Med. 2004;199:775–784. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031591. Epub 2004 Mar 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Curtsinger JM, Gerner MY, Lins DC, Mescher MF. Signal 3 availability limits the CD8 T cell response to a solid tumor. J Immunol. 2007;178:6752–6760. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.6752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Way SS, Havenar-Daughton C, Kolumam GA, Orgun NN, Murali-Krishna K. IL-12 and type-I IFN synergize for IFN-gamma production by CD4 T cells, whereas neither are required for IFN-gamma production by CD8 T cells after Listeria monocytogenes infection. J Immunol. 2007;178:4498–4505. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nakane A, Minagawa T. The significance of alpha/beta interferons and gamma interferon produced in mice infected with Listeria monocytogenes. Cell Immunol. 1984;88:29–40. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(84)90049-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Feng H, Zhang D, Palliser D, Zhu P, Cai S, Schlesinger A, Maliszewski L, Lieberman J. Listeria-infected myeloid dendritic cells produce IFN-beta, priming T cell activation. J Immunol. 2005;175:421–432. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.1.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pietras EM, Saha SK, Cheng G. The interferon response to bacterial and viral infections. J Endotoxin Res. 2006;12:246–250. doi: 10.1179/096805106X118799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sun S, Zhang X, Tough DF, Sprent J. Type I interferon-mediated stimulation of T cells by CpG DNA. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2335–2342. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.12.2335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stetson DB, Medzhitov R. Type I interferons in host defense. Immunity. 2006;25:373–381. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pestka S, Krause CD, Walter MR. Interferons, interferon-like cytokines, and their receptors. Immunol Rev. 2004;202:8–32. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Clerico M, Contessa G, Durelli L. Interferon-beta1a for the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2007;7:535–542. doi: 10.1517/14712598.7.4.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Santantonio T. Treatment of acute hepatitis C. Curr Pharm Des. 2004;10:2077–2080. doi: 10.2174/1381612043384222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Carbognin SJ, Solomon NM, Yeo FE, Swanson SJ, Bohen EM, Koff JM, Sabnis SG, Abbott KC. Acute renal allograft rejection following pegylated IFN-alpha treatment for chronic HCV in a repeat allograft recipient on hemodialysis: a case report. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:1746–1751. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Braun M, Vierling JM. The clinical and immunologic impact of using interferon and ribavirin in the immunosuppressed host. Liver Transpl. 2003;9:S79–89. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2003.50257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]