Abstract

Although the maintenance mechanism of late long-term potentiation (LTP) is critical for the storage of long-term memory, the expression mechanism of synaptic enhancement during late-LTP is unknown. The autonomously active protein kinase C isoform, protein kinase Mζ (PKMζ), is a core molecule maintaining late-LTP. Here we show that PKMζ maintains late-LTP through persistent N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor (NSF)/glutamate receptor subunit 2 (GluR2)-dependent trafficking of AMPA receptors (AMPARs) to the synapse. Intracellular perfusion of PKMζ into CA1 pyramidal cells causes potentiation of postsynaptic AMPAR responses; this synaptic enhancement is mediated through NSF/GluR2 interactions but not vesicle-associated membrane protein-dependent exocytosis. PKMζ may act through NSF to release GluR2-containing receptors from a reserve pool held at extrasynaptic sites by protein interacting with C-kinase 1 (PICK1), because disrupting GluR2/PICK1 interactions mimic and occlude PKMζ-mediated AMPAR potentiation. During LTP maintenance, PKMζ directs AMPAR trafficking, as measured by NSF/GluR2-dependent increases of GluR2/3-containing receptors in synaptosomal fractions from tetanized slices. Blocking this trafficking mechanism reverses established late-LTP and persistent potentiation at synapses that have undergone synaptic tagging and capture. Thus, PKMζ maintains late-LTP by persistently modifying NSF/GluR2-dependent AMPAR trafficking to favor receptor insertion into postsynaptic sites.

Keywords: PKMζ, PKCζ, NSF, GluR2, PICK1, LTP

Introduction

The maintenance mechanism of the late, protein synthesis-dependent phase of long-term potentiation (LTP) is critical for the storage of long-term memory (Pastalkova et al., 2006; Shema et al., 2007). Although the expression of the early induction phase of LTP has been studied extensively (Bliss and Collingridge, 1993), the mechanism for synaptic enhancement during the late phase of LTP is unknown. One approach to identify the expression mechanism of synaptic enhancement during late-LTP is to examine how the molecular mechanism that maintains late-LTP enhances synaptic transmission. A prime candidate for a core molecule maintaining late-LTP is protein kinase Mζ (PKMζ), an autonomously active isozyme of protein kinase C (PKC) (Bliss et al., 2006).

PKMζ maintains synaptic enhancement during late-LTP through its second-messenger-independent and thus persistent kinase activity. PKMζ consists of an independent PKCζ catalytic domain produced from a brain-specific PKMζ mRNA, which, lacking an autoinhibitory PKCζ regulatory domain, is constitutively active (Sacktor et al., 1993; Hernandez et al., 2003). During LTP induction, afferent tetanic stimulation increases the synthesis of PKMζ from its mRNA (Hernandez et al., 2003; Muslimov et al., 2004; Kelly et al., 2007), and the resulting persistent increase in the autonomously active kinase is both necessary and sufficient for maintaining LTP (Ling et al., 2002). Postsynaptic perfusion of PKMζ increases the efficacy of AMPA receptor (AMPAR)-mediated synaptic transmission (Ling et al., 2002, 2006), whereas inhibitors of the kinase activity of PKMζ reverse LTP even when applied hours after the tetanization, without affecting baseline synaptic transmission (Ling et al., 2002; Sajikumar et al., 2005; Serrano et al., 2005; Pastalkova et al., 2006).

PKMζ maintains a stable enhancement of synaptic transmission exclusively by increasing the number of functional postsynaptic AMPARs (Ling et al., 2006); therefore, the kinase may act to upregulate one of the AMPAR trafficking pathways that maintains a constant number of postsynaptic receptors under basal conditions. We therefore began by examining two core pathways that regulate basal AMPAR trafficking: one dependent on the interaction between the chaperone-like protein N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor (NSF) and the intracellular C terminus of the glutamate receptor subunit 2 (GluR2) AMPAR subunit (Nishimune et al., 1998; Osten et al., 1998; Song et al., 1998); the other an exocytotic pathway requiring a membrane fusion event mediated by vesicle-associated membrane protein (VAMP)/synaptobrevin (Lüscher et al., 1999).

Materials and Methods

Animals.

For experiments in Figures 1–4 and supplemental Figures 1–6 (available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material), hippocampi of male, ∼3- to 4-week-old Sprague Dawley rats were removed after decapitation under halothane-induced anesthesia, according to State University of New York Downstate Medical Center Animal Use and Care Committee standards. For tagging experiments in supplemental Figure 7 (available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material), male, 7-week-old Wistar rats were used in accordance with Leibniz Institute for Neurobiology animal care standards.

Figure 1.

PKMζ enhances AMPAR-mediated synaptic transmission through NSF/GluR2 interactions. A, Postsynaptic perfusion of PKMζ through a whole-cell recording pipette enhances AMPAR responses at Schaffer collateral/commissural-CA1 pyramidal cell synapses (black open circles); pep2m (100 μm) together with PKMζ blocks AMPAR potentiation (red filled circles). pep2m alone has minimal effect on baseline synaptic transmission at 0.067 Hz (red filled squares) compared with baseline recordings without pep2m (black open squares). Left insets for all panels show representative traces recorded ∼1 min (left) and ∼13 min (right) after cell breakthrough. Right insets for all panels show the subtraction of baseline responses from responses with PKMζ alone (black open circles) and the subtraction of baseline responses in the presence of the agent from responses with PKMζ together with the agent (red filled circles). The number of experiments for each condition is five to six. B, Inactive scrambled version of pep2m (100 μm) has no effect on PKMζ-mediated potentiation of AMPAR responses (n = 4–5). C, pep-NSF3 (100 μm), which blocks the ATPase activity of NSF, prevents PKMζ-mediated potentiation of AMPAR responses (n = 4). D, Blockade of exocytosis by Botox B (0.5 μm) does not affect PKMζ-mediated potentiation of AMPAR responses (n = 4). Right inset, Responses with baselines subtracted show no significant difference.

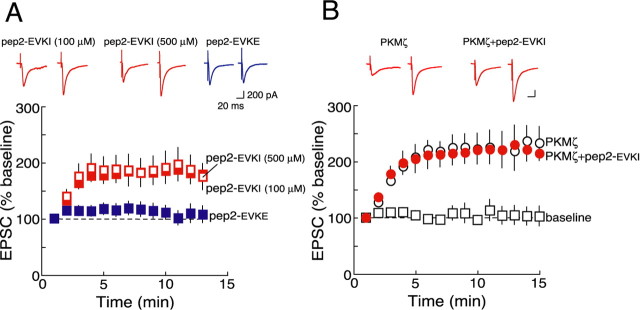

Figure 2.

Disruption of GluR2/PICK1 interactions mimics and occludes PKMζ-mediated AMPAR potentiation. A, Intracellular perfusion of pep2-EVKI with 100 μm (red filled squares; n = 6) and 500 μm (red open squares; n = 3) in the recording pipette produce similar degrees of AMPAR potentiation. Inactive peptide pep2-EVKE did not cause potentiation (100 μm; blue filled squares; n = 5). B, PKMζ alone (black open circles; n = 5) and PKMζ with pep2-EVKI (100 μm; red filled circles; n = 5) show equivalent potentiation.

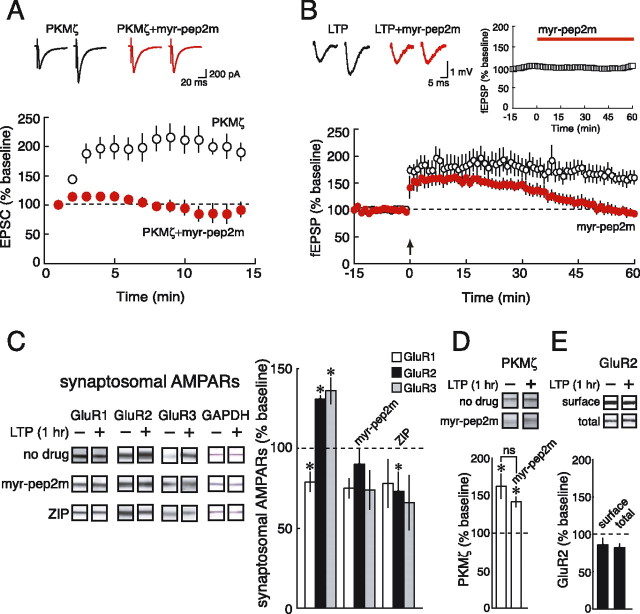

Figure 3.

PKMζ-mediated NSF/GluR2 trafficking is critical for AMPAR potentiation during LTP. A, Bath application of myr-pep2m (10 μm) blocks PKMζ-mediated potentiation of AMPAR responses (red filled circles are responses in the presence of the agent; black open circles in its absence; n = 5). Insets above show representative EPSC responses 1 min (left) and 13 min (right) after cell breakthrough. B, myr-pep2m blocks the persistence of LTP (red filled circles are responses in the presence of myr-pep2m and black open circles in its absence; tetanization is denoted by an arrow; n = 10). Top left insets, Representative field responses 1 min before and 60 min after tetanization. Top right inset, Application of myr-pep2m does not affect baseline synaptic transmission (n = 4; the SEM symbols are all smaller than the mean symbols). C, Synaptosomal GluR2 and GluR3 subunits increase and GluR1 subunits decrease 1 h after tetanization (n = 8–10). Applications of myr-pep2m (10 μm) and the PKMζ inhibitor ZIP (2 μm) block the increase of synaptosomal GluR2 and GluR3 (n = 4). Left, Representative immunoblots; GAPDH was used to normalize AMPAR immunostaining levels with respect to protein loading on immunoblots. Right, Mean data; significant differences denoted by asterisks. D, myr-pep2m does not prevent the increase of PKMζ 1 h after tetanization. Top, Representative immunoblots; bottom, mean data (no drug, n = 10; myr-pep2m, n = 4; asterisks denote significant differences relative to nontetanized slices; ns denotes no significant difference between PKMζ levels with and without myr-pep2m). E, Surface (measured by biotin labeling) and total GluR2 levels do not change 1 h after tetanization. Top, Representative immunoblots; bottom, mean data (surface, n = 4; total, n = 8).

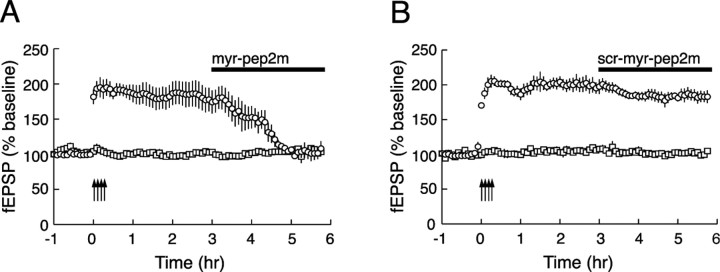

Figure 4.

NSF/GluR2 interactions mediate the persistence of late-LTP. A, myr-pep2m (10 μm) reverses late-LTP when applied 3 h after tetanic stimulation (open circles). The inhibitor has no effect on an independent pathway simultaneously recorded within each slice (open squares) (n = 4). B, An inactive version of myr-pep2m (scr-myr-pep2m; 10 μm) has no effect on potentiation (n = 4).

Hippocampal slice preparation, stimulation, and recording.

For whole-cell recordings, hippocampal slices (400 μm) were prepared using a Vibratome tissue sectioner. The slices were transferred to an incubation chamber at 32°C in oxygenated (95% O 2–5% CO2) physiological saline containing the following (in mm): 124 NaCl, 5 KCl, 26 NaHCO3, 1.6 MgCl2, 4 CaCl2, and 10 glucose, for a minimum of 1.5 h before recording. After incubation, single slices were transferred to a 1.5 ml recording chamber placed on the stage of an upright microscope (Zeiss Axioskop 2; Carl Zeiss) and perfused with warm (31–33°C) saline at ∼5 ml/min. Visualized CA1 pyramidal cells were held at −75 mV, the empirically determined reversal potential of the GABAA receptor (Ling et al., 2002). Synaptic events were evoked every 15 s (or every 2.5 s in supplemental Fig. 1, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material) by extracellular stimulation with bipolar electrodes placed in stratum radiatum. The recording pipettes had tip resistance of 2–4 MΩ and contained 130 mm Cs-MeSO4, 10 mm NaCl, 2 mm EGTA, 10 mm HEPES, 1 mm CaCl2, 2 mm Na-ATP, and 0.5 mm Na-GTP, with or without PKMζ [7–20 nm, 0.5–0.9 pmol · min−1 · μl−1 phosphotransferase activity (Ling et al., 2002)], with or without peptides (100 μm, unless otherwise specified): pep2m (KRMKVAKNAQ; Tocris Bioscience), scr-pep2m (VRKKNMAKQA; Pepsyn), pepNSF3 (TGKTLIARKIGTMLNAREPK; Pepsyn), pep-ΔA849-Q853 (KRMKLNINPS; Quality Control Biochemicals), pep2-EVKI (YNVYGIEEVKI; Tocris Bioscience), pep2-EVKE (YNVYGIEEVKE; Quality Control Biochemicals), or botulinum toxin B light chain (Botox B) (0.5 μm; List Biological Laboratories). (A myristoyl group was added to the N terminal during synthesis of myr-pep2m and scr-myr-pep2m.) The pH value of the pipette solution was adjusted to 7.3 with CsOH. Cs was used to block potassium currents, including GABAB responses. Evoked AMPAR-mediated EPSCs were recorded under voltage-clamp mode with a Warner Instruments PC-501A amplifier and filtered at 2 kHz (−3 dB, four-pole Bessel). Brief voltage steps (−5 mV, 5 or 10 ms) from holding potential were applied during the course of recording to monitor cell access resistance, input resistance, and capacitance. Only cells with an initial input resistance of >100 MΩ and an initial access resistance of <20 MΩ with insignificant change (<20%) during the course of recording were accepted for study. Signals were digitized with Digidata 1322A and acquired and analyzed with pClamp software (Molecular Devices) running on a Pentium microcomputer. The peak amplitude of EPSCs was further analyzed with Excel (Microsoft). The mean ± SEM of 1 min bins of the responses were plotted in the figures.

Field EPSPs (fEPSPs) were recorded using glass microelectrodes with a resistance of 3–8 MΩ, filled with the recording saline, and positioned 200 μm from the stimulating electrodes in stratum radiatum. Current intensity of test stimuli (20–40 μA, 0.1 ms duration) was set to produce one-third maximal fEPSPs (1–2 mV). The frequency of test stimulation was every 15 s and the mean ± SEM of 1 min bins of responses plotted in the figures. The slope of the fEPSP was measured between 10 and 50% of the initial phase of the fEPSP response. The tetanization protocol for biochemical experiments (see Fig. 3) was optimized to produce a relatively rapid onset of a protein synthesis-dependent phase of potentiation (Osten et al., 1996; Tsokas et al., 2005) (supplemental Fig. 4, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material) and consisted of four 100 Hz, 1 s trains, set at 75% of the maximal fEPSP response (15–30 μA above the test stimuli current intensity), delivered at 20 s intertrain intervals. For late-LTP in Figure 4, tetanization was performed as described previously (Serrano et al., 2005) and consisted of four 100 Hz, 1 s trains, set at 75% of the maximal fEPSP response, delivered at 5 min intervals. Control synaptic pathways were shown to be independent by the absence of paired-pulse facilitation between the pathways, as described previously (Serrano et al., 2005). Tagging experiments in supplemental Figure 7 (available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material) were performed with different stimulation and recording techniques as detailed previously (Sajikumar et al., 2005). Briefly, strong tetanization producing late-LTP consisted of three 100 Hz, 1 s trains, duration of 0.2 ms per polarity, delivered at 10 min intervals, using monopolar stainless steel electrodes. Weak tetanization producing early-LTP consisted of one 100 Hz train of 21 biphasic constant-current pulses, 0.2 ms pulse duration per half-wave at the stimulus intensity of the population spike threshold. Test stimulation for tagging experiments consisted of four 0.2 Hz biphasic, constant-current pulses (0.1 ms per polarity), delivered 1, 3, 5, 11, 15, 21, 25, and 30 min after tetanization and thereafter once every 15 min. Data were analyzed with custom-made software (PWIn; HN Magdeburg).

Synaptosome preparation and immunoblotting.

Two CA1 regions per group were homogenized in 100 μl of homogenization buffer containing the following: 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm EGTA, 0.1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 5 mm benzamidine, 17 kallikrein units/ml aprotinin, 0.1 mm leupeptin, and 1% phosphatase inhibitor cocktails 1 and 2. All reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich, and all biochemical experiments were at 4°C, unless otherwise stated. Total protein was measured by bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce). Control slices were from the same hippocampus; in parallel experiments, no changes in AMPAR or PKMζ levels were detected between slices maintained with and without test stimulation (data not shown); therefore unstimulated slices were used for comparisons with LTP. Homogenization was performed in number 19 Kontes glass homogenizing tubes using a Talboy 102 homogenizer (20 strokes at 60 rpm). To measure total AMPARs, 10 μl of this homogenate was spun at 100,000 × g for 30 min, resulting in a membrane pellet that was resuspended in 20 μl of homogenization buffer and heated for 10 min at 90°C with sample buffer. To obtain the synaptosomal fraction (Chin et al., 1989), 90 μl of the homogenate was added to 110 μl of 2 m sucrose (resulting in 200 μl of a 1.1 m sucrose homogenate); 160 μl of 0.8 m sucrose was then layered on the 1.1 m sucrose homogenate, and the preparation spun at 1625 × g for 10 min. The 0.8 m sucrose gradient was collected, added to three times its volume of homogenization buffer, and spun at 15,555 × g for 8 min. The pellet was resuspended in 20 μl of homogenization buffer with sample buffer and heated to 90°C for 10 min. Coenrichment of AMPAR subunits and the postsynaptic marker postsynaptic density-95 protein (PSD-95) (antiserum 1:500; Millipore Bioscience Research Reagents) is shown in supplemental Figure 6 (available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material).

The samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE (20 μl/1 cm lane). After electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and the membrane was blocked for 90 min in 1% bovine serum albumin and 1% hemoglobin in Tris-buffered saline with 1% NP-40 (TBSN) (Sacktor et al., 1993). Multiple proteins from a single band were measured by cutting the lanes into up to eight separate strips and placing strips from different lanes together for probing with specific primary antisera (Sacktor et al., 1993). Primary antisera were GluR1 (1:100; Oncogene), GluR2 (1:500; Millipore Bioscience Research Reagents), and GluR3 (1:500; Millipore Bioscience Research Reagents), incubated overnight at 4°C. Immunostaining for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (1:10,000; Sigma) was used to normalize AMPARs with respect to protein loading. The membrane was then washed in TBSN, followed by a 90 min incubation with secondary antibody coupled to alkaline phosphatase (1:2000). The blots were developed with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate/nitro blue tetrazolium, and optical density was analyzed using NIH Image. Representative images of the bands from these strips are presented in Figure 3C.

Surface GluR2 labeling was adapted from methods described previously (Grosshans et al., 2002). CA1 regions were dissected from the slices and incubated for 45 min in 1 mg/ml biotin in PBS at 4°C. After sonication for 10 s, the surface protein was separated from total protein using streptavidin beads overnight at 4°C, and the surface and total protein were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting, as described above, except development was with chemiluminescence (Supersignal West Femto; Pierce). The relative level of surface GluR2 is expressed as surface/total immunostaining × 100. PKMζ was measured by C-terminal ζ antiserum (1:100) (Sacktor et al., 1993).

Immunoprecipitation.

Immunoprecipitation (IP) of PKMζ from hippocampal homogenates was performed as described previously (Kelly et al., 2007). For IP of protein interacting with C-kinase 1 (PICK1), the hippocampal homogenate was incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-PICK1 antiserum (N-18, 5 μg/200 μl homogenate; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Immunoblots of the immunoprecipitate were performed with the following antisera: PKCα (H-7, 1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), PKCε (E-5, 1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), PKMζ (C-terminal, 1:500) (Kelly et al., 2007), and PICK1 (2 μg/ml; Affinity BioReagents).

Statistics.

Values are presented as mean ± SEM. Within-group differences were determined by paired t test and between-group comparisons by unpaired t test or one-way ANOVA, followed by Sheffé's post hoc test. One-way ANOVA repeated measurements followed by least significant difference and Tukey's post hoc tests were used for comparisons of subunit levels and multiple time points, respectively.

Results

PKMζ enhances AMPAR-mediated synaptic transmission through NSF/GluR2 interactions but not VAMP-mediated exocytosis

Blocking the interaction between NSF and GluR2 by postsynaptic perfusion of pep2m, a peptide that mimics the NSF-binding site in GluR2, causes a rundown of basal AMPAR responses (Nishimune et al., 1998; Song et al., 1998). This rundown is dependent on afferent synaptic activity (Lüscher et al., 1999) and is reversed by periods of synaptic inactivity (Duprat et al., 2003). This contrasts with the enhancement of synaptic transmission by PKMζ, which is independent of afferent stimulation (Ling et al., 2006). Therefore, to isolate an effect of pep2m on PKMζ-mediated potentiation, we minimized the basal rundown induced by the peptide by stimulating at a relatively low rate. Thus, whereas postsynaptic perfusion of pep2m (100 μm) produced baseline rundown with afferent stimulation at a test frequency of every 2.5 s (supplemental Fig. 1, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material), it caused only minimal rundown with test stimulation every 15 s (Fig. 1A) (p = 0.30 between responses at 1 and 13 min of recording; p = 1.0 between responses at 13 min with and without pep2m). Using this test stimulation frequency, we examined the effect of pep2m on PKMζ-mediated AMPAR potentiation.

Perfusion of PKMζ alone into CA1 pyramidal cells doubled the amplitude of AMPAR responses within 5 min of recording, as described previously (Ling et al., 2002, 2006; Serrano et al., 2005) (Fig. 1A) (p < 0.005 between responses at 1 and 13 min). In interleaved experiments, perfusion of pep2m together with the kinase strongly attenuated the potentiation (Fig. 1A) (p < 0.01 between responses at 13 min with PKMζ alone and responses with PKMζ and pep2m, p = 0.20 between 1 and 13 min of recording with PKMζ and pep2m, and p = 0.24 at 13 min between PKMζ with pep2m and pep2m alone). A scrambled, inactive version of the peptide (scr-pep2m) (Liu and Cull-Candy, 2005) had no effect on PKMζ-mediated potentiation (Fig. 1B) (p = 1.0 at 13 min between PKMζ alone and PKMζ with scr-pep2m). PKMζ-mediated AMPAR potentiation required the activity of NSF because pep-NSF3, a peptide that inhibits the ATPase activity of NSF (Lee et al., 2002), also blocked the synaptic enhancement (Fig. 1C) (p < 0.01 between responses at 13 min with PKMζ alone and with PKMζ and pep-NSF3, p = 0.30 between responses at 1 and 13 min with PKMζ and pep-NSF3, p = 0.16 at 13 min between PKMζ with pep-NSF3 and pep-NSF3 alone). In contrast, a peptide that blocks the interaction between the clathrin adaptor AP2 and GluR2 at a binding site that partially overlaps with that of NSF (Lee et al., 2002) did not affect AMPAR potentiation by PKMζ (supplemental Fig. 2, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material) (responses at 13 min with PKMζ alone and with PKMζ and pep-ΔA849-Q853 are not significantly different, p = 0.83).

We then examined the constitutive, exocytotic AMPAR trafficking pathway to the synapse, which is blocked by Botox B that cleaves VAMP/synaptobrevin (Lüscher et al., 1999). As expected, postsynaptic perfusion of Botox B (0.5 μm) depressed baseline AMPAR-mediated transmission (Fig. 1D) (p < 0.05 between responses at 1 and 13 min in the presence of Botox B). In contrast to pep2m, however, the toxin did not prevent PKMζ-mediated AMPAR potentiation (p = 0.36 comparing responses at 13 min with PKMζ alone and PKMζ plus Botox B with baselines subtracted) (Fig. 1D, right inset).

Disruption of GluR2/PICK1 interactions mimics and occludes PKMζ-mediated AMPAR potentiation

These results indicate that PKMζ enhances AMPAR responses selectively through the NSF/GluR2-dependent AMPAR trafficking pathway. A primary action of NSF on GluR2 is to disrupt the interaction between GluR2 and PICK1 (Hanley et al., 2002). We therefore tested whether blocking this interaction mimics and occludes the effect of PKMζ. Perfusing pep2-EVKI, which selectively disrupts GluR2/PICK1 interactions, relative to GluR2 interactions with glutamate receptor AMPAR binding protein (ABP)-interacting protein (GRIP)/ABP (Chung et al., 2000), caused synaptic potentiation (Fig. 2A) (100 μm; p < 0.01 between 1 and 13 min of recording), consistent with kinetics but higher in amplitude than that described previously (Kim et al., 2001) (but see Daw et al., 2000, in which no potentiation was observed). A control peptide (pep2-EVKE) had no effect on basal synaptic transmission (Fig. 2A) (p = 0.8 between 1 and 13 min of recording). Increasing the amount of pep2-EVKI in the pipette from 100 to 500 μm did not augment the synaptic enhancement, indicating that these concentrations of the peptide in the pipette produced a maximal effect (Fig. 2A) (p = 0.9 at 13 min of recording). Adding pep2-EVKI (100 μm) to PKMζ did not increase postsynaptic AMPAR enhancement compared with PKMζ alone (Fig. 2B) (the responses at 13 min of recording with PKMζ alone vs PKMζ and pep2-EVKI was not significantly different, p = 0.2). Although occlusion experiments must be interpreted cautiously, these results suggest that the action of PKMζ and the release of GluR2 from PICK1 enhance postsynaptic AMPAR responses by the same mechanism.

Because PICK1 interacts with PKCα but not other conventional or novel PKC isoforms (Staudinger et al., 1997), we asked whether PICK1 also interacts with PKMζ, which had not been examined previously. PKMζ, as well as PKCα, but not the novel PKCε that is abundant in brain, coimmunoprecipitated from hippocampal extracts (supplemental Fig. 3, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material).

PKMζ-mediated, NSF/GluR2-dependent AMPAR trafficking is critical for LTP expression

Does PKMζ regulate NSF/GluR2-dependent AMPAR trafficking during LTP? To disrupt NSF/GluR2 interactions during recordings of long-term synaptic plasticity, we tested the effect of a cell-permeable, myristoylated version of pep2m (myr-pep2m) (Garry et al., 2003). We first confirmed the effectiveness of bath applications of myr-pep2m to hippocampal slices by testing the ability of the agent to block AMPAR potentiation by postsynaptic perfusion of PKMζ. As with the intracellular application of pep2m, bath applications of myr-pep2m (10 μm) blocked PKMζ-mediated AMPAR potentiation (Fig. 3A) (p < 0.01 between responses at 13 min with PKMζ alone and responses with PKMζ and myr-pep2m; p = 0.58 between responses at 1 and 13 min with PKMζ and myr-pep2m).

We determined whether blocking NSF/GluR2 interactions affects LTP by applying myr-pep2m to the bath and stimulating with a tetanization protocol optimized to produce a relatively rapid onset of the protein synthesis-dependent phase of LTP (Osten et al., 1996; Tsokas et al., 2005), as shown by a rapid decline in potentiated responses in the presence of the protein synthesis inhibitor anisomycin (supplemental Fig. 4, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). myr-pep2m prevented the expression of LTP persistence at 1 h after tetanization (Fig. 3B) (p < 0.0001 between responses in the presence and absence of myr-pep2m 1 h after tetanization; p = 0.35 between responses in the presence of myr-pep2m before and 1 h after tetanization). The agent did not significantly affect potentiation within the first 15 min after tetanization, although a trend for a decrease was observed (for the 15 min after tetanization, repeated-measures ANOVA showed no significant effect with respect to drug (saline vs myr-pep2m) (F(1,16) = 4.37, p = 0.053), time (F(14,224) = 1.56, p = 0.093), and drug × time interaction (F(14,224) = 0.71, p = 0.77)). myr-pep2m also did not affect baseline responses (Fig. 3B, right inset) (p = 1.0 between responses 1 min before and 60 min after myr-pep2m), and a scrambled version of the peptide did not affect LTP (supplemental Fig. 5, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). Interestingly, the decrement in potentiation was somewhat faster with myr-pep2m than with anisomycin (supplemental Fig. 4, inset, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material), suggesting that NSF/GluR2 interactions might play a role in both protein synthesis-independent and protein synthesis-dependent phases of LTP.

To confirm that PKMζ mediates NSF/GluR2-dependent AMPAR trafficking during LTP, we examined the trafficking of AMPARs during LTP maintenance that can be observed by biochemical fractionation techniques (Heynen et al., 2000; Grosshans et al., 2002; Whitlock et al., 2006; Williams et al., 2007). One hour after tetanization, we isolated synaptosomes from the CA1 regions (Chin et al., 1989) (Fig. 3C) (supplemental Fig. 6, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material) and found that the AMPAR subunits GluR2 and GluR3 increased in the synaptosomal fraction (p < 0.02), whereas GluR1 subunits decreased (p < 0.01). myr-pep2m prevented the increases in synaptic GluR2 and GluR3 (Fig. 3C), demonstrating that these changes in distribution of AMPARs during LTP were dependent on NSF/GluR2 interactions.

We then determined the role of PKMζ in mediating the NSF/GluR2-dependent redistribution of AMPARs in LTP maintenance. We first found that myr-pep2m did not block the increase of PKMζ in the hippocampal slices during LTP maintenance, indicating that blocking NSF/GluR2 interactions did not prevent the induction of PKMζ synthesis (Hernandez et al., 2003; Kelly et al., 2007) (Fig. 3D) (p < 0.05 comparing PKMζ levels 1 h after tetanization with levels in control nontetanized slices, in both the presence and absence of myr-pep2m; p = 0.31 between posttetanization PKMζ levels with and without the agent). Conversely, however, inhibiting PKMζ with the selective, cell-permeable, myristoylated ζ inhibitory peptide (ZIP) prevented both the late phase of LTP, as reported previously (Ling et al., 2002; Sajikumar et al., 2005; Serrano et al., 2005) (data not shown), and blocked the NSF/GluR2-dependent increase in synaptic GluR2/3 (Fig. 3C, a significant decrease in GluR2 was observed). Consistent with the lack of effect of PKMζ on the exocytotic pathway of AMPAR trafficking, the total surface expression of GluR2 measured by biotin labeling did not increase 1 h after tetanization (Fig. 3E, bottom left). The total amount of GluR2 (surface and internal) also did not change (Fig. 3E, bottom right). Thus, PKMζ mediates the NSF/GluR2-dependent changes in AMPAR distribution during LTP.

NSF/GluR2-dependent AMPAR trafficking is the persistent expression mechanism of late-LTP and potentiation after synaptic tagging

The hallmark of PKMζ is its unique role in maintaining the persistence of LTP. Indeed, PKMζ inhibitors are the only agents known to reverse established late-LTP (Ling et al., 2002; Sajikumar et al., 2005; Serrano et al., 2005; Pastalkova et al., 2006). We therefore asked whether blocking the expression mechanism of PKMζ-mediated synaptic potentiation by myr-pep2m could also reverse established LTP. To test for a persistent effect on maintenance, we strongly tetanized one synaptic pathway and then applied myr-pep2m 3 h after tetanization (Fig. 4A). myr-pep2m reversed potentiation in the tetanized pathway (p < 0.01 between baseline and 3 h after tetanization and between 3 and 5 h after tetanization; p > 0.05 between baseline and 5 h after tetanization) but did not affect a second, independent nontetanized pathway simultaneously recorded within each of the slices. The inactive scrambled version of myr-pep2m had no effect (Fig. 4B) (p < 0.001 between baseline and 5 h after tetanization; p > 0.05 between 3 and 5 h after tetanization; p < 0.0001 between myr-pep2m and scrambled myr-pep2m at 5 h after tetanization).

PKMζ-mediated late-LTP can also be “captured” by weakly stimulated synapses through the process of synaptic tagging (Frey and Morris, 1997; Sajikumar et al., 2005). Blocking NSF/GluR2-mediated AMPAR trafficking with myr-pep2m reversed persistent potentiation at both the strongly stimulated synapses and the weakly stimulated synapses that underwent synaptic tagging and capture (supplemental Fig. 7, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material).

Discussion

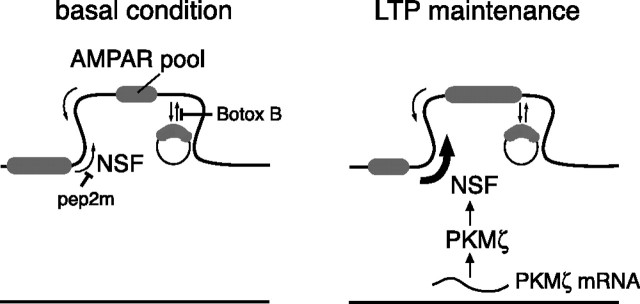

Although late-LTP is dependent on new protein synthesis for its induction, the mechanism of expression of synaptic enhancement during late-LTP has been unknown previously. Because PKMζ is synthesized in LTP induction (Hernandez et al., 2003; Muslimov et al., 2004; Kelly et al., 2007) and is then necessary and sufficient for maintaining synaptic potentiation during late-LTP (Ling et al., 2002; Serrano et al., 2005), our approach was first to determine the mechanism by which the kinase enhances AMPAR-mediated synaptic transmission. We found that PKMζ works selectively through upregulation of an NSF/GluR2-dependent AMPAR trafficking pathway to increase postsynaptic AMPARs. We then showed that PKMζ regulates NSF/GluR2-dependent AMPAR trafficking during LTP maintenance and, finally, that synaptic potentiation during late-LTP maintenance is expressed through this pathway. Because NSF/GluR2-dependent trafficking serves to maintain a constant number of postsynaptic AMPARs under basal conditions, late-LTP maintenance can be viewed as a persistent resetting by an autonomously active kinase of this homeostatic trafficking mechanism to favor an increased number of receptors at postsynaptic sites (Fig. 5). Future work will be required to determine which substrates of PKMζ mediate this transformation.

Figure 5.

In late-LTP maintenance, PKMζ persistently upregulates an AMPAR trafficking mechanism that maintains a constant number of postsynaptic receptors under basal conditions. Left, Illustration of NSF/GluR2-mediated and exocytotic pathways maintaining the postsynaptic AMPAR pool under basal conditions. After afferent activity, NSF acts to traffic AMPARs back to the synapse (or prevent their release from the synapse), which can be blocked by pep2m. The inhibitory action of Botox B on trafficking of AMPARs is shown as blocking exocytosis from a putative internal pool to the synapse. Right, PKMζ maintains LTP through enhancing NSF/GluR2-mediated trafficking of AMPARs to the synapse by releasing receptors from an extrasynaptic pool.

The action of PKMζ to enhance synaptic transmission may be through the ability of NSF to disrupt the binding of GluR2-containing receptors with PICK1, a trafficking protein that is critical for both hippocampal long-term depression (LTD) and LTP (Terashima et al., 2008). A pool of GluR2 appears to be excluded from synapses by binding with PICK1, because disrupting GluR2/PICK1 interactions by pep2-EVKI increases postsynaptic AMPAR responses. Although occlusion experiments are to be interpreted cautiously, PKMζ may act, through NSF, to decrease the size of this extrasynaptic pool of receptors, which are then free to traffic to the synapse. In addition, because PICK1 is critical for endocytosis of AMPARs (Xia et al., 2000; Perez et al., 2001), PKMζ may act to redirect AMPARs away from endocytosis, allowing more to be available for postsynaptic insertion. Interestingly, the AMPAR trafficking driven by PKMζ is opposite in direction to the pathway mediated by PKCα, which directs GRIP/ABP-bound, postsynaptic GluR2-containing receptors away from the synapse to PICK1 and thus to endocytosis during LTD (Xia et al., 2000; Perez et al., 2001). Indeed, we found both PKMζ and PKCα in complexes with PICK1 in hippocampal extracts. Variation in the balance between these PKC isoforms before experimentation may set the level of the PICK1-bound extrasynaptic AMPAR pool and thus contribute to the differences in the response to pep-EVKI seen in the literature (Daw et al., 2000; Kim et al., 2001). An alternative hypothesis for PKMζ-mediated potentiation is that the kinase acts to form and maintain a dynamic postsynaptic “slot” (Shi et al., 2001; McCormack et al., 2006), to which the trafficking of AMPARs requires NSF/GluR2 interactions. Directing AMPARs to the synapse and maintaining a structural slot to receive the receptors are not mutually exclusive mechanisms.

During LTP, PKMζ regulates the trafficking of GluR2/3 receptors through NSF/GluR2-dependent interactions, as measured by changes in the amount of the subunits in synaptosomal fractions. These results are generally consistent with the delayed postsynaptic increase in overexpressed GluR2/3 subunits observed during LTP (Shi et al., 2001; McCormack et al., 2006) and with the protein synthesis-dependent increase in GluR2/3 surface expression in synaptoneurosomes during LTP in vivo (Williams et al., 2007). In our study, the increase in synaptosomal GluR2/3 occurs without a change in the total amount of surface GluR2-containing AMPARs, consistent with previous observations (Grosshans et al., 2002), suggesting a lateral redistribution of the receptors from extrasynaptic to synaptic sites. Local exocytosis near the synapse by a non-VAMP/synaptobrevin-mediated process, however, below our level of detection or compensated by endocytosis elsewhere, cannot be excluded (Beretta et al., 2005). Although these crude fractionation techniques provide only limited information as to receptor location, they demonstrate that an NSF/GluR2-dependent redistribution of AMPARs occurs in LTP maintenance and is mediated by PKMζ activity.

This PKMζ-mediated, NSF/GluR2-dependent AMPAR trafficking is functionally critical for the expression of LTP maintenance. Blocking the trafficking reversed late-LTP at either strongly tetanized synapses or at weakly tetanized synapses that had undergone synaptic tagging and capture. These findings relate late-LTP expression to other forms of synaptic plasticity, particularly in the cerebellum, in which a critical role for NSF/GluR2 interactions has been observed for both synaptic depression and potentiation (Steinberg et al., 2004; Gardner et al., 2005; Kakegawa and Yuzaki, 2005; Liu and Cull-Candy, 2005). These other forms of synaptic plasticity have been studied in their early phase, when second-messenger-dependent protein kinases are typically thought to regulate receptor trafficking as transient mechanisms. Although it is currently unknown whether the persistent increase in PKMζ observed in LTP maintenance (Osten et al., 1996) extends throughout the late phase of LTP (and long-term memory), the only agents known to reverse established late-LTP are inhibitors of PKMζ kinase activity and now an inhibitor of the AMPAR-trafficking expression mechanism of PKMζ-mediated synaptic potentiation. Thus, late-LTP can be viewed as a sustained version of a short-term plasticity mechanism, in which the synthesis of an autonomously active kinase continually drives receptors to postsynaptic sites. This persistent but dynamic mechanism may allow for stable yet flexible storage of information at synapses to be the physiological substrate of long-term memory (Pastalkova et al., 2006; Shema et al., 2007).

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants RO1 MH53576 and MH57068 (T.C.S.), American Heart Association Grant 051226T (P.B.), and German Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung Grant FKZ-01GW0553 (J.U.F.).

References

- Beretta F, Sala C, Saglietti L, Hirling H, Sheng M, Passafaro M. NSF interaction is important for direct insertion of GluR2 at synaptic sites. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2005;28:650–660. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliss TV, Collingridge GL. A synaptic model of memory: long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Nature. 1993;361:31–39. doi: 10.1038/361031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliss TV, Collingridge GL, Laroche S. Neuroscience. ZAP and ZIP, a story to forget. Science. 2006;313:1058–1059. doi: 10.1126/science.1132538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin GJ, Shapiro E, Vogel SS, Schwartz JH. Aplysia synaptosomes. I. Preparation and biochemical and morphological characterization of subcellular membrane fractions. J Neurosci. 1989;9:38–48. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-01-00038.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung HJ, Xia J, Scannevin RH, Zhang X, Huganir RL. Phosphorylation of the AMPA receptor subunit GluR2 differentially regulates its interaction with PDZ domain-containing proteins. J Neurosci. 2000;20:7258–7267. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-19-07258.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daw MI, Chittajallu R, Bortolotto ZA, Dev KK, Duprat F, Henley JM, Collingridge GL, Isaac JT. PDZ proteins interacting with C-terminal GluR2/3 are involved in a PKC-dependent regulation of AMPA receptors at hippocampal synapses. Neuron. 2000;28:873–886. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00160-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duprat F, Daw M, Lim W, Collingridge G, Isaac J. GluR2 protein-protein interactions and the regulation of AMPA receptors during synaptic plasticity. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2003;358:715–720. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey U, Morris RG. Synaptic tagging and long-term potentiation. Nature. 1997;385:533–536. doi: 10.1038/385533a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner SM, Takamiya K, Xia J, Suh JG, Johnson R, Yu S, Huganir RL. Calcium-permeable AMPA receptor plasticity is mediated by subunit-specific interactions with PICK1 and NSF. Neuron. 2005;45:903–915. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garry EM, Moss A, Rosie R, Delaney A, Mitchell R, Fleetwood-Walker SM. Specific involvement in neuropathic pain of AMPA receptors and adapter proteins for the GluR2 subunit. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2003;24:10–22. doi: 10.1016/s1044-7431(03)00134-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosshans DR, Clayton DA, Coultrap SJ, Browning MD. LTP leads to rapid surface expression of NMDA but not AMPA receptors in adult rat CA1. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:27–33. doi: 10.1038/nn779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley JG, Khatri L, Hanson PI, Ziff EB. NSF ATPase and alpha-/beta-SNAPs disassemble the AMPA receptor-PICK1 complex. Neuron. 2002;34:53–67. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00638-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez AI, Blace N, Crary JF, Serrano PA, Leitges M, Libien JM, Weinstein G, Tcherapanov A, Sacktor TC. Protein kinase Mζ synthesis from a brain mRNA encoding an independent protein kinase Cζ catalytic domain. Implications for the molecular mechanism of memory. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:40305–40316. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307065200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heynen AJ, Quinlan EM, Bae DC, Bear MF. Bidirectional, activity-dependent regulation of glutamate receptors in the adult hippocampus in vivo. Neuron. 2000;28:527–536. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00130-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakegawa W, Yuzaki M. A mechanism underlying AMPA receptor trafficking during cerebellar long-term potentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:17846–17851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508910102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly MT, Crary JF, Sacktor TC. Regulation of protein kinase Mzeta synthesis by multiple kinases in long-term potentiation. J Neurosci. 2007;27:3439–3444. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5612-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CH, Chung HJ, Lee HK, Huganir RL. Interaction of the AMPA receptor subunit GluR2/3 with PDZ domains regulates hippocampal long-term depression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:11725–11730. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211132798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SH, Liu L, Wang YT, Sheng M. Clathrin adaptor AP2 and NSF interact with overlapping sites of GluR2 and play distinct roles in AMPA receptor trafficking and hippocampal LTD. Neuron. 2002;36:661–674. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01024-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling DS, Benardo LS, Serrano PA, Blace N, Kelly MT, Crary JF, Sacktor TC. Protein kinase Mζ is necessary and sufficient for LTP maintenance. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:295–296. doi: 10.1038/nn829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling DS, Benardo LS, Sacktor TC. Protein kinase Mzeta enhances excitatory synaptic transmission by increasing the number of active postsynaptic AMPA receptors. Hippocampus. 2006;16:443–452. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu SJ, Cull-Candy SG. Subunit interaction with PICK and GRIP controls Ca2+ permeability of AMPARs at cerebellar synapses. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:768–775. doi: 10.1038/nn1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüscher C, Xia H, Beattie EC, Carroll RC, von Zastrow M, Malenka RC, Nicoll RA. Role of AMPA receptor cycling in synaptic transmission and plasticity. Neuron. 1999;24:649–658. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81119-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack SG, Stornetta RL, Zhu JJ. Synaptic AMPA receptor exchange maintains bidirectional plasticity. Neuron. 2006;50:75–88. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muslimov IA, Nimmrich V, Hernandez AI, Tcherepanov A, Sacktor TC, Tiedge H. Dendritic transport and localization of protein kinase Mzeta mRNA: implications for molecular memory consolidation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:52613–52622. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409240200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimune A, Isaac JT, Molnar E, Noel J, Nash SR, Tagaya M, Collingridge GL, Nakanishi S, Henley JM. NSF binding to GluR2 regulates synaptic transmission. Neuron. 1998;21:87–97. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80517-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osten P, Valsamis L, Harris A, Sacktor TC. Protein synthesis-dependent formation of protein kinase Mζ in LTP. J Neurosci. 1996;16:2444–2451. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-08-02444.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osten P, Srivastava S, Inman GJ, Vilim FS, Khatri L, Lee LM, States BA, Einheber S, Milner TA, Hanson PI, Ziff EB. The AMPA receptor GluR2 C terminus can mediate a reversible, ATP-dependent interaction with NSF and alpha- and beta-SNAPs. Neuron. 1998;21:99–110. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80518-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastalkova E, Serrano P, Pinkhasova D, Wallace E, Fenton AA, Sacktor TC. Storage of spatial information by the maintenance mechanism of LTP. Science. 2006;313:1141–1144. doi: 10.1126/science.1128657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez JL, Khatri L, Chang C, Srivastava S, Osten P, Ziff EB. PICK1 targets activated protein kinase Cα to AMPA receptor clusters in spines of hippocampal neurons and reduces surface levels of the AMPA-type glutamate receptor subunit 2. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5417–5428. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-15-05417.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacktor TC, Osten P, Valsamis H, Jiang X, Naik MU, Sublette E. Persistent activation of the zeta isoform of protein kinase C in the maintenance of long-term potentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:8342–8346. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sajikumar S, Navakkode S, Sacktor TC, Frey JU. Synaptic tagging and cross-tagging: the role of protein kinase Mζ in maintaining long-term potentiation but not long-term depression. J Neurosci. 2005;25:5750–5756. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1104-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano P, Yao Y, Sacktor TC. Persistent phosphorylation by protein kinase Mζ maintains late-phase long-term potentiation. J Neurosci. 2005;25:1979–1984. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5132-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shema R, Sacktor TC, Dudai Y. Rapid erasure of long-term memory associations in cortex by an inhibitor of PKM zeta. Science. 2007;317:951–953. doi: 10.1126/science.1144334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi S, Hayashi Y, Esteban JA, Malinow R. Subunit-specific rules governing AMPA receptor trafficking to synapses in hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Cell. 2001;105:331–343. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00321-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song I, Kamboj S, Xia J, Dong H, Liao D, Huganir RL. Interaction of the N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor with AMPA receptors. Neuron. 1998;21:393–400. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80548-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staudinger J, Lu J, Olson EN. Specific interaction of the PDZ domain protein PICK1 with the COOH terminus of protein kinase C-alpha. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:32019–32024. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.32019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg JP, Huganir RL, Linden DJ. N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor is required for the synaptic incorporation and removal of AMPA receptors during cerebellar long-term depression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:18212–18216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408278102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terashima A, Pelkey KA, Rah JC, Suh YH, Roche KW, Collingridge GL, McBain CJ, Isaac JT. An essential role for PICK1 in NMDA receptor-dependent bidirectional synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2008;57:872–882. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsokas P, Grace EA, Chan P, Ma T, Sealfon SC, Iyengar R, Landau EM, Blitzer RD. Local protein synthesis mediates a rapid increase in dendritic elongation factor 1A after induction of late long-term potentiation. J Neurosci. 2005;25:5833–5843. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0599-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlock JR, Heynen AJ, Shuler MG, Bear MF. Learning induces long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Science. 2006;313:1093–1097. doi: 10.1126/science.1128134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JM, Guévremont D, Mason-Parker SE, Luxmanan C, Tate WP, Abraham WC. Differential trafficking of AMPA and NMDA receptors during long-term potentiation in awake adult animals. J Neurosci. 2007;27:14171–14178. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2348-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia J, Chung HJ, Wihler C, Huganir RL, Linden DJ. Cerebellar long-term depression requires PKC-regulated interactions between GluR2/3 and PDZ domain-containing proteins. Neuron. 2000;28:499–510. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00128-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]