Abstract

Several diseases are characterized by the presence of point mutations, which are amenable to molecular detection using a number of methods including PCR. However, certain mutations are particularly difficult to detect due to factors such as low abundance or the presence of special (e.g. oligo-nucleotide repeat) sequences. The mutation 7A in the oligoA sequence of the exon 7 of the gene encoding La autoantigen is difficult to detect at the DNA and even RNA level due to both its estimated low abundance and its differentiation from the wild type 8A sequence. This paper describes a technique in which amplification of the excess wild type 8A La sequence is suppressed by a peptide nucleic acid (PNA) during a nested PCR step. Detection of the amplified 7A mutant form was then performed by simple electrophoresis following a final primer extension step with an infrared dye-labeled primer. This technique allowed us to detect the mutation in 3 of 7 individuals harboring serum IgG antibodies reactive with a B cell neo-epitope in the 7A-mutant protein product. We propose that this method is a viable screening test for mutations in regions containing simple poly-nucleotide repeats.

INTRODUCTION

Various diseases can be identified and characterized by simple molecular biological techniques such as PCR, sequencing, restriction fragment length polymorphism and ligase chain reaction. Detection of a mutation can aid in disease diagnoses or make possible differential diagnoses. Most autoimmune diseases are characterized by the presence of certain autoantibodies. Several studies indicate that the La autoantigen [1–3] may play a role not only in diagnosis but also in the pathomechanisms of certain autoimmune diseases such as Sjögren’s syndrome (Ss) [4], systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) [5], or complete congenital heart block [6–7].

In previous studies, Bachmann et al. [8–9] have described a rare simple oligo-adenine (A) somatic deletion at nt 1050–1057 within an oligo8A stretch of the La gene (Exon 7) in a cDNA library generated from peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) of an index patient diagnosed with SLE and Ss. Importantly, deletion of a single A nucleotide generated a codon frameshift that placed 12 novel aa before an early truncation codon at aa 204 thus creating a neo-C terminus. Transgenic overexpression of the 7A mutant form of La in mice resulted in an autoimmune phenotype [8], suggesting that this mutation can result in processes that lead to autoimmune reactions. Bachmann et al. [8] tested sera from SLE and Ss patients and approximately 30% of anti-La autoantibody positive SLE patients, including the index patient, produce IgG antibodies to a B cell neo-epitope created as a consequence of the 7A frameshift, suggesting immunologic exposure to the 7A mutant protein product [8].

Screening for the 7A mutation in large populations by simple molecular biological techniques, including PCR, has been hampered by the rarity of this mutation in comparison to the wild type allele (estimated from biochemical protein studies to occur in less than 0.01% of PBL (M. Bachmann, unpublished studies), and by a tendency of the poly(A) sequence to loop out during primer binding. A molecular test is needed to identify human populations harboring the mutation without the confounding possibility of serologic cross-reactivity that could potentially lead to false positives.

Several different methods have been used to detect rare mutations in the presence of vast excesses of competing wild type sequences [9–11]. The advent of modified oligonucleotides exhibiting high specificity and discriminating potency has made possible the identification of even “hard-to-detect” mutation types [12]. Among them there are solutions such as suppression of amplification of unwanted sequences with peptide nucleic acids (PNA) [13] or enhanced primer specificity mediated through the use of locked nucleic acids (LNA) [14]. Indeed, PNA oligonucleotides, which cannot be extended by polymerases but which exhibit measurably higher melting temperatures than standard oligonucleotides, have been used successfully for the detection of several clinically relevant mutations [15–17].

We propose that there is a significant need to develop improved molecular tests that will identify human populations harboring single poly-nucleotide mutations. Herein, we describe the development of an assay for detection of the 7A La mutation in La cDNAs of individuals demonstrating serologic reactivity with the 7A neo-B cell epitope. We demonstrate that our mutant enrichment amplification strategy utilizing nested PCR in combination with PNA technology to suppress amplification of the wild type 8A sequence, followed by an infrared dye-labeled primer extension step is amenable to high-throughput screening strategies. Using this technique, we detected the mutation in 43% of individuals testing positive for IgG anti-7(A) neo-epitope antibodies, and suggest that this technique would be a valuable method for screening of other similar disease-associated mutations within regions containing simple poly-nucleotide repeats.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human subjects

Matched serum and RNA samples of a preliminary sample group containing 22 individuals were from the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, and consisted of 10 samples from normal healthy controls (Cohort 1) and 12 samples from individuals with clinically confirmed sicca symptoms including salivary flow reduction (11 of 12), swollen salivary glands (4 of 12) and positive Schirmer’s tests (4 of 12) (Cohort 2). An additional 17 serum samples from normal healthy controls were obtained from the same repository. All samples were obtained and used under approved protocols at the University of Minnesota and the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation.

7A mutant La peptide ELISA

Serum of an index patient was previously shown to contain IgG antibodies reactive with the 7A hLa neo-B cell epitope AKKMKKENKIKWKLN (non-templated mutant amino acids translated following the point deletion-induced frameshift are underlined) [8]. Cohorts 1 and 2 were screened for IgG antibodies against the neo-B cell epitope and a control sequence from a corresponding region of wild type human La, hLa189–204 (FAKKEERKQNKVEAK), using multiple antigenic peptide (MAP™) ELISA methods as described previously [8]. Samples were tested in duplicate and normalized to eliminate inter-assay variation.

Primers and plasmids

HPLC- and gel-purified standard oligonucleotide primers were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). The 8A PNA primer was obtained from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA), and the infrared dye (IRD700)-labeled extension primer was purchased from LI-COR Biosciences (Lincoln, NE). All primer sequences are indicated in Fig. 1. As reference plasmids we used pGEM-T clones containing either the native (8A residues in exon 7; pLa-native) or mutant (7A residues in exon 7; pLa-mutant) La gene. Cloning of the plasmids was described previously [8].

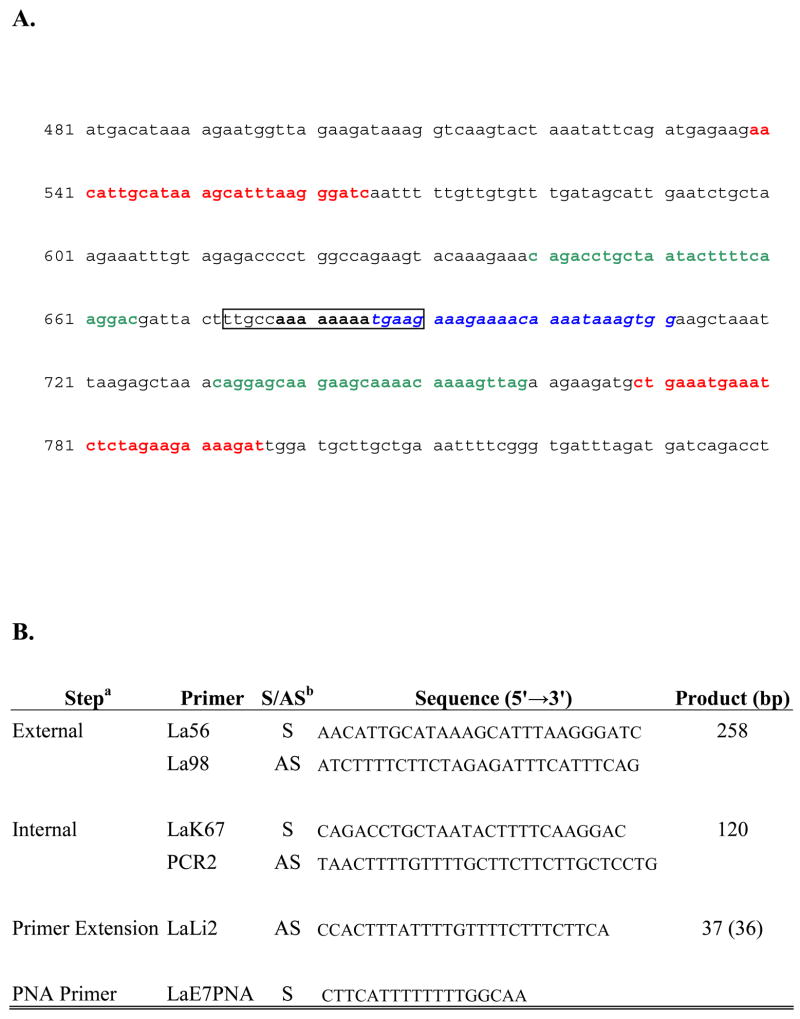

Figure 1.

Location of primer sequences used in mRNA (cDNA) detection of a human La/SS-B oligo 7A mutation.

A. Oligo (A) DNA sequence mutation site is located in the box, with the PNA primer binding region indicated in bold black letters. The external primer regions are indicated in red letters, and the internal primer regions used in the nested PCR reaction are designated in green. The binding location of the infrared dye 700-labeled primer used in the primer extension step is denoted in blue letters.

B. Primer sequences used in amplification and extension. a Refer to the text and Figure 1a. b S=sense; AS=anti-sense.

RNA isolation and reverse transcription into cDNA

Total RNA was isolated from stored frozen PBL of the index 7A mutant La positive patient [3] using Trizol reagent. Total RNA of 22 individuals (Cohort 1 and 2) were isolated from peripheral blood cells using PAXgene blood RNA tubes (Quiagen, Valencia, CA). Total peripheral blood cell RNA (3 μg) was transcribed into cDNA using the Superscript reverse transcriptase system according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Invitrogen) in a final volume of 21 μl.

Amplification of the mutation

Nested PCR was used to amplify the region within the cDNA that contained the oligoA sequence of interest. In the first PCR reaction the DNA from 1 μl cDNA solution was amplified using 0.33 μM of primers by AmpliTaq polymerase (Applied Biosystems) at 2.5 mM MgCl2 concentration in a final volume of 25 μl. The amplification conditions were: 94°C 5 min then 40 cycles of 94 °C 30 sec, 61 °C 30 sec, 72 °C 30 sec followed by a 72 °C at 5 min closing step. In the second PCR reaction 1 μl of the first PCR mixture was used as a template under the same reaction conditions used in the first step except 5 mM of MgCl2 was used. During both PCR reactions the 8A PNA oligonucleotide was added to the reaction mixture in a final concentration of 5 μM.

Detection of the mutated 7A form by infrared dye primer extension

To remove the unnecessary primers and nucleotides before the primer extension step, 10 μl of the final nested PCR reaction was treated with ExoSAP-IT (USB, Cleveland, OH) at 37 °C for 1 hr followed by a heat inactivation. The cleaned PCR product of about 300 ng/μl was the template in the primer extension step where the IRD700 primer (Fig. 1) concentration was 0.5 μM. The primer extension was performed with 1U AmpliTaq polymerase in a solution containing 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 50 μM of dTTP, dGTP and dATP each in a final volume of 10 μl. The conditions of the extension were: 10 cycles of 94 °C for 30 sec; 61 °C for 30 sec and 72 °C for 30 sec. The products were electrophoresed in a 10% polyacrylamide sequencing gel using a LI-COR 4200 infrared detection instrument.

Sequencing of primer extension products

Primer extension products were cloned into a TA cloning vector (TOPO TA Cloning Kit, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) per manufacturer’s suggested guidelines, amplified in XL-1 Blue E. coli and purified using a Plasmid mini-prep kit (Qiagen). Plasmids were resuspended at a concentration of 100 ng/μl in sterile water and sequenced at the OMRF sequencing core facility using T7 primer sets.

RESULTS

IgG antibodies directed to a 7A-mutant La neo-B-cell epitope occur in individuals with sicca symptoms

Based on the identification of serum IgG antibodies directed to a multiple antigenic peptide (MAP™) containing the 7A La neo-B cell epitope identified in an index patient with SLE and secondary Ss, we sought to screen for the presence of this antibody in a preliminary cohort of 27 serum samples from normal, healthy control individuals who lacked any reported pathologic conditions and 12 serum samples from individuals with clinically confirmed sicca symptoms. None of the 27 control samples exhibited measurable IgG antibodies reactive with the mutant peptide and only 1 had reactivity to the corresponding wild type one (data not shown). Of the 12 samples obtained from individuals with sicca symptoms (Cohort 2), 7 contained IgG antibodies reactive with the mutant La neo-B cell epitope at a level >2SD above the mean of the 27 normal, healthy controls (Table 1), and none of the 12 sera reacted with the corresponding wild type human La peptide.

Table 1.

IgG anti-7(A) mutant La antibody status in the sera of study subjects with matching sera and RNA samples

| Cohort 1 | Cohort 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | OD405 | #SDa Above Controls | Sample | OD405 | #SDa Above Controls |

| 1 | 0.206 | <2 | 1 | 0.597 | 5.18 |

| 2 | 0.224 | <2 | 2 | 0.680 | 6.28 |

| 3 | 0.207 | <2 | 3 | 0.053 | <2 |

| 4 | 0.347 | <2 | 4 | 0.418 | 2.83 |

| 5 | 0.215 | <2 | 5 | 0.240 | <2 |

| 6 | 0.127 | <2 | 6 | 0.378 | 2.3 |

| 7 | 0.224 | <2 | 7 | 1.324 | 14.7 |

| 8 | 0.182 | <2 | 8 | 0.368 | 2.2 |

| 9 | 0.092 | <2 | 9 | 0.240 | <2 |

| 10 | 0.199 | <2 | 10 | 0.378 | 2.3 |

| 11 | 0.270 | <2 | |||

| 12 | 0.120 | <2 | |||

Optical Density (OD405) and number of standard deviations (SD) above the mean of 27 normal, healthy controls reporting no pathologic conditions is shown. Values ≥ 2SD above the mean value of 27 normal healthy controls were considered positive. All samples typed negative for IgG antibodies to the wild type human La 189–204 peptide (not shown). The median OD405 value of Cohort 2 was significantly greater than that of Cohort 1 (p=0.0018; Mann Whitney U-test)

Nested PCR and a PNA oligonucleotide enhance detection of a rare 7A molecular somatic mutation within an oligoA-repeat of the La gene in the presence of excess 8A wild type allele

The ability to identify and amplify poly-nucleotide repeat sequences has proven useful in the study of disease, but it is difficult to screen for in large populations due to technical limitations. Using plasmid constructs containing cDNA of either the wild-type (oligo 8A) or the mutant (oligo7A) human La sequences in concert with a peptide nucleic acid (PNA) primer, we were able to develop a nested PCR amplification/primer extension procedure. Both the wild type 8A and mutant 7A alleles were efficiently and specifically amplified and detected by gel electrophoresis using this procedure; the mutant 7A form was not detected using the standard 8A template (Fig. 2; 8) and the wild-type 8A form was not detected using the standard 7A template (Fig. 2; 7). As expected, amplification of cDNA from the index patient (Fig. 2; I) yielded extension products containing both wild-type and mutant alleles.

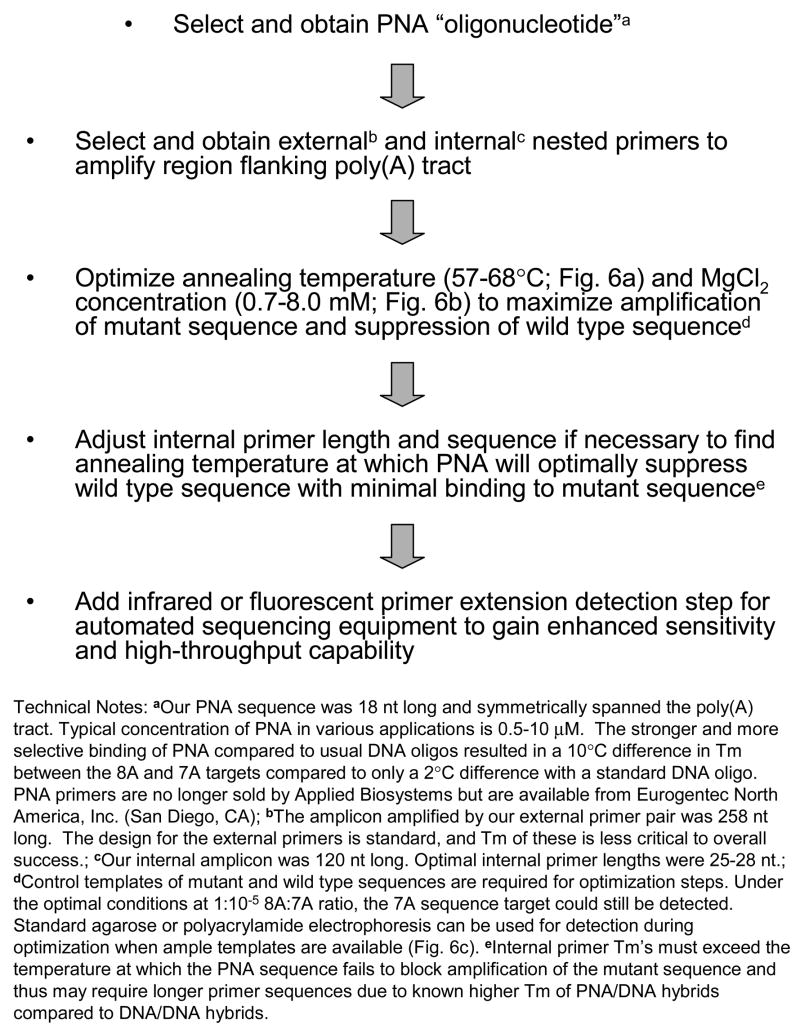

Figure 2.

Detection of the wild-type and the mutant sequence in the exon 7 of the La gene. Images of infrared signals from polyacrylamide sequencing gels were generated by the LI-COR 4200 software. Lanes in which control templates were used (Standards) are indicated at bottom of the gel and were either a wild type 8A standard plasmid (denoted 8), a mutant 7A standard plasmid (denoted 7) or cDNA taken from frozen PBL of the index patient (denoted I). Lanes in which template was cDNA from Cohort 1 donors are denoted with the identifiers 1 through 10, which correspond to identifiers in Table 1. The 7A and 8A primer extension products are indicated by the arrows. Both 7A and 8A bands were detected in the index patient (I), whereas only the wild type 8A form was detected in the healthy control donors.

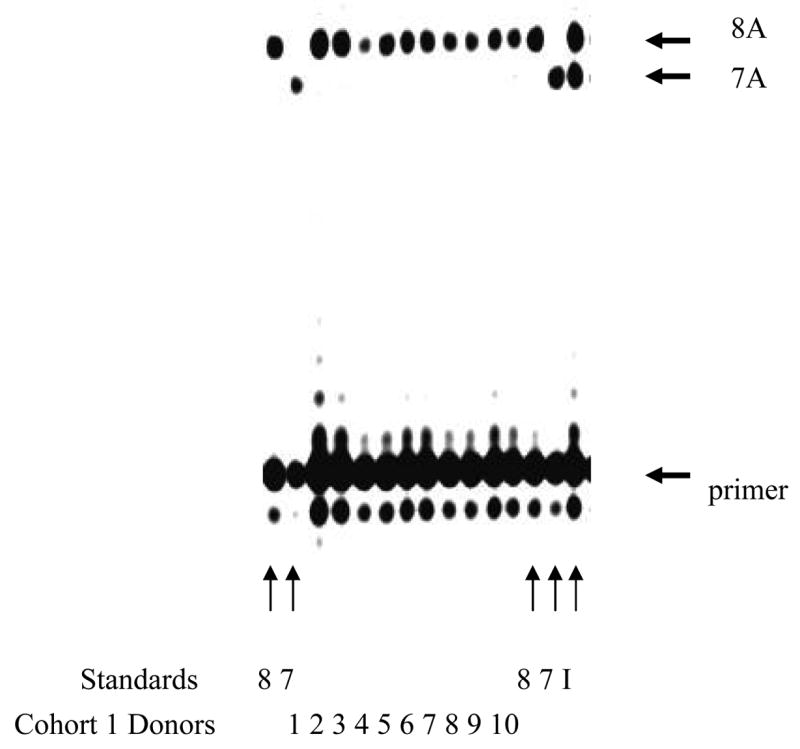

Individuals from Cohorts 1 and 2 were screened for molecular evidence of the mutant 7A allele. Of the 10 healthy donors (Cohort 1) tested for molecular evidence of the mutation, 10 of 10 (100%) tested positive for the wild type 8A allele only (Fig. 2; 1 to 10), and 0 of 10 (0%) tested positive for anti-neo-epitope antibodies (Table 1). Of the 12 individuals with sicca syndromes included in Cohort 2, 7 of 12 (58%; sicca-reporting individuals 1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 8 and 10, Table 1) individuals tested positive for anti-7A neo-epitope antibodies and 3 of those 7 testing positive for antibody production (43%; Sicca 2, 6 and 10) were positive for both 7A mutant and 8A wild type alleles (Fig. 3; 1 to 12). In these individuals, the 7A product dominated. Significantly, the 7A mutant allele was clearly absent in samples 4, 9, 11 and 12. Strong 8A and faint 7A bands were observed in samples 1, 3, 5 and 8, and these results were considered equivocal. Due to insufficient amplification material from sample 7, we were unable to assess La mutation status.

Figure 3.

Detection of the mutation in the exon 7 of the La gene. Images of infrared signals from polyacrylamide sequencing gels were generated by the LI-COR 4200 software. Lanes in which control templates were used (Standards) are indicated at bottom of the gel and were either a wild type 8A standard plasmid (denoted 8) or a mutant 7A standard plasmid (denoted 7). Lanes in which template was cDNA from Cohort 2 donors, who displayed clinical sicca symptoms, are denoted with the identifiers 1 through 12, which correspond to identifiers in Table 1. The 7A and 8A primer extension products are indicated by the arrows.

To confirm the identities of the sequences amplified during PCR, primer extension products were cloned and sequenced. Sequences obtained from 10 or more clones obtained from three 7A positive and three 7A negative individuals tested confirmed the specificity of the 7A mutant and 8A wild type amplification (Data not shown).

Association of serologic and molecular evidence of the 7A somatic mutation

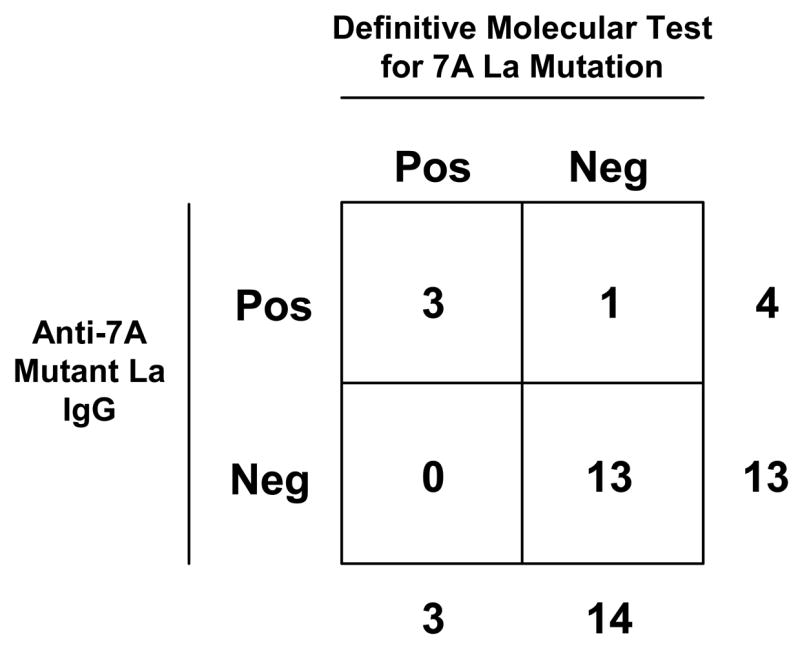

In total, 13 of 14 (93%) individuals we assessed who definitively lacked the 7A mutation (10 in Cohort 1 and 4 in Cohort 2) also lacked antibodies to the 7A neo-epitope MAP. In contrast, 3 of 3 (100%) individuals unequivocally positive for the 7A mutation also produced the IgG anti-neoepitope antibodies. Therefore, given this preliminary cohort of individuals with a definitive molecular typing outcome, a significant association existed between the presence of the anti-neo-epitope antibody and molecular evidence of the mutation (p = 0.006, Fisher’s Exact Test; Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Positive association of serologic and molecular evidence of the 7A somatic mutation. The 2 × 2 contingency table shown depicts the frequency of detectable IgG antibodies to the 7A mutant La MAP™ among individuals with a definitive molecular typing outcome. A two-tailed Fisher’s Exact Test revealed a significant positive association between the two parameters at p = 0.006.

DISCUSSION

Somatic point mutations are associated with disease and can aid in differential disease diagnosis. These mutations can be synonymous, in which they do not change the structure and function of their cognate gene products, or they can be non-synonymous and can alter sequences that change gene expression, tertiary protein structure, folding or function. These changes can be induced by non-conservative amino acid substitution or codon frame shifting due to inappropriate insertions or deletions of non-coded nucleotides.

Initially we attempted to detect the 7A La mutation in the PBL of patients suffering from different autoimmune diseases using a PCR-single strand conformational polymorphism (SSCP) method. Although differentiating between the wild type 8A and the mutant 7A sequences was possible using this technique, the sensitivity of the assay was extremely low due to the rarity of the mutant allele relative to the wild type. In the present work, we have employed a mutant enrichment amplification strategy based on the use of peptide nucleic acid (PNA) to further enhance sensitivity of the assay.

Peptide nucleic acids are synthetic DNA analogs in which the phosphodiester backbone has been replaced by an electrically neutral pseudopeptide backbone [18]. Owing to this structure, PNAs have unique hybridization characteristics that allow them to hybridize to their target nucleic acids with higher specificity and stringency. This is due to a lack of electrostatic repulsion that results in a higher melting temperature for PNA-DNA duplexes compared to that of DNA-DNA duplexes [19]. Moreover, PNAs can specifically block primer annealing or chain elongation, are resistant to nucleases and proteases and are not recognized by polymerases. All of these characteristics make PNAs ideal for suppressing amplification of unwanted sequences, resulting in a higher degree of discrimination between normal and mutated sequences [20–22]. Due to the enhanced specificity and avidity of the PNA to the wild type allele, we were able to successfully amplify as low as an estimated 1×10−6 copies of the 7A allele relative to 8A alleles by PCR amplification.

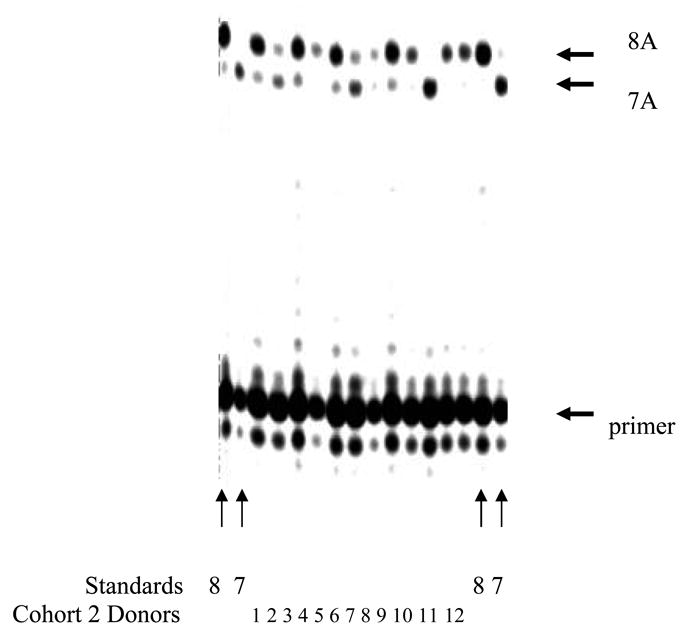

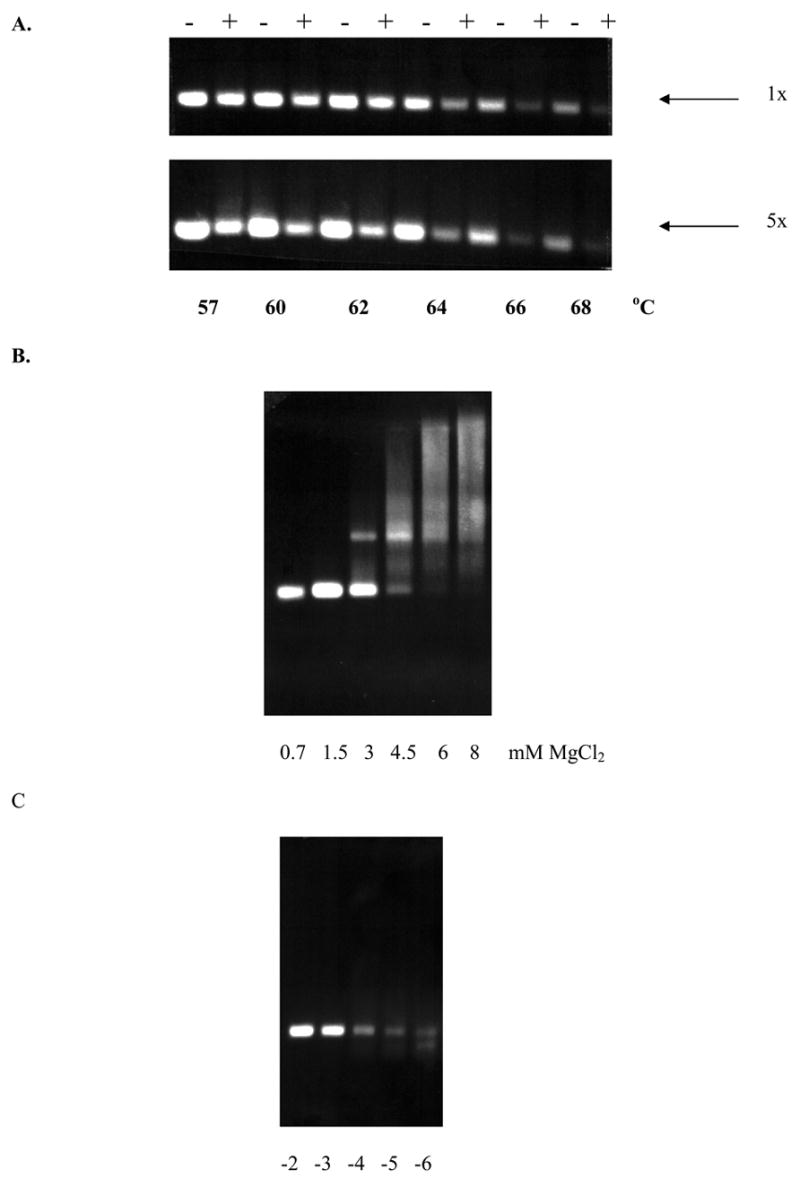

PCR and nested PCR are multi-purpose techniques that can be used for gene amplification and expression, mRNA quantification, cloning and sequencing. They are particularly useful as diagnostic tools in the identification of hard-to-detect sequences [23–25]. The most significant factor in developing a PCR-based assay is the molecular optimization of the procedure so it will be functional even with a diverse sample base. We determined that the most critical functional parameter in our assay was the melting temperature difference between the two duplexes that were formed by the PNA:wild-type and PNA:mutant alleles. Sequence length and composition of various internal primer sets were serially analyzed using primer design software followed by PCR-based optimization to determine the annealing temperature at which the PNA optimally bound the wild-type allele only. The concentrations of MgCl2 and PNA primer also significantly influenced our ability to fully discriminate between the 7A and 8A alleles. The concentration of MgCl2 in the presence and absence of PNA was titrated to enhance binding of the wild-type allele by the PNA without negatively affecting amplification of the mutant allele. The procedure was validated using splenocytes of mice transgenic for the wild type 8A form of La [26] and mice transgenic for the 7A mutant form of La [8], which allowed us to specifically and sensitively amplify the rare human La 7A mutant target sequence in the presence of excess 8A wild-type sequence (not shown). Fig. 5 outlines a general approach for developing a PNA-based suppression assay for the detection of rare poly(A) tract mutations, and Fig. 6 shows examples of the optimization steps used in the present study. We believe that this technique can be used to detect and amplify sequences possibly as rare as a single copy. We have determined that a combination of nested PCR and PNA-mediated suppression is a powerful tool for detecting a rare 7A mutant allele in the presence of excess wild type 8A sequence.

Figure 5.

Suggested PNA-mediated suppression assay development procedure for the detection of rare poly(A) tract mutations.

Figure 6.

Optimization of the procedure.

A. An example of the effects of different temperatures on the PCR yields using the wild type 8A template at 1x and 5x PNA concentration is shown. − = without PNA; + = with PNA.

B. An example of the effects of MgCl2 concentrations on the PCR yields is shown.

C. Effects of 8A to 7A ratio on the detection of PCR products. 7A long products were detected using PNA suppression. -2 to -6 represent log dilutions of 100 to 1 000 000 times dilution of the 7A standard in presence of 1 unit of the 8A standard.

Allelic alterations resulting from poly-nucleotide insertions or deletions in various genes are becoming increasingly associated with disease processes [27–29]. Thus, in addition to advancing our understanding of the La 7A mutation, we propose that the technical approach reported herein is useful for screening and detection of simple poly-nucleotide mutations in larger cohorts for multiple diseases and we believe that this test will facilitate additional studies assessing biologic consequences of this mutation in human subjects.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01-GM63497, R01-AI048097, P50-AR048940 and K02-AI051647) and through the support of Dr. Imre Semsei as a Greenberg Scholar of the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation. The authors express gratitude to Dr. Kenneth Kaufman, Dr. John Harley, Parvathi Vinod and Billy Herring for use and assistance with the Li-Cor sequencers. Dr. Kavit A. Desouza assisted with TA cloning.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Wolin SL, Steitz JA. The Ro small cytoplasmic ribonucleoproteins: identification of the antigenic protein and its binding site on the Ro RNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:1996–2000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.7.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bachmann M, Pfeifer K, Schröder HC, Müller WEG. Characterization of the autoantigen La as a nucleic acid dependent ATPase/dATPase with melting properties. Cell. 1990;60:85–93. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90718-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grölz D, Laubinger J, Wilmer F, Tröster H, Bachmann M. Transfection analysis of expression of mRNA isoforms encoding the nuclear autoantigen La/SS-B. J Biol Chem. 1997;18:12076–12082. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.18.12076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mok CC, Lau CS. Pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56:481–490. doi: 10.1136/jcp.56.7.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Venables PJ, Shattles W, Pease CT, Ellis JE, Charles PJ, Maini RN. Anti-La (SS-B): a diagnostic criterion for Sjögren’s syndrome? Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1989;7:181–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buyon JP. Neonatal lupus syndromes. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1992;28:259–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1992.tb00810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buyon JP. Neonatal lupus and autoantibodies reactive with SSA/Ro-SSB/La. Scand J Rheumatol. 1998;107:23–30. doi: 10.1080/03009742.1998.11720702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bachmann MP, Holger B, Gross JK, Maier SM, Gross TF, Workman JL, James JA, Farris AD, Jung B, Franke C, et al. Autoimmunity as a result of escape from RNA surveillance. J Immunol. 2006;177:1698–1707. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.3.1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Behn M, Schuermann M. Sensitive detection of P53 gene mutations by a “mutant enriched” PCR-SSCP technique. Nucl Acids Res. 1998;26:1356–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.5.1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun X, Hung K, Wu L, Sidransky D, Guo B. Detection of tumor mutations in the presence of excess amounts of normal DNA. Nature Biochem. 2002;19:186–9. doi: 10.1038/nbt0202-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dominguez PL, Kolodney MS. Wild-type blocking polymerase chain reaction for detection of single nucleotide minority mutations from clinical specimens. Oncogene. 2005;24:6830–68304. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Egholm M, Buchardt O, Christensen L, Behrens C, Freier SM, Driver DA, Berg RH, Kim SK, Norden B, Nielsen PE. PNA hybridizes to oligonucleotides obeying Watson-crick hydrogen bonding rules. Nature. 1993;365:566–8. doi: 10.1038/365566a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thiede C, Bayerdörffer E, Blasczyk R, Wittig B, Neubauer A. Simple and sensitive mutations in the ras proto-oncogenes using PNA mediated PCR clamping. Nucl Acids Res. 1996;24:983–4. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.5.983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vester B, Wengel J. LNA (Locked Nucleic Acid): High-affinity targeting of complementary RNA and DNA. Biochemistry. 2004;43:13233–41. doi: 10.1021/bi0485732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen CY, Shiesh SC, Wu SJ. Rapid detection of K-ras mutations in bile by peptide nucleic acid-mediated PCR clamping and melting curve analysis: Comparison with restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. Clin Chem. 2004;50:481–9. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2003.024505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fiandaca MJ, Hyldig-Nielsen JJ, Gildea BD, Coull JM. Self-reporting PNA/DNA primers for PCR analysis. Genom Res. 2001;11:609–613. doi: 10.1101/gr.170401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braasch DA, Corey DR. Synthesis, Analysis, Purification, and Intracellular Delivery of Peptide Nucleic Acids. Methods. 2001;23:97–107. doi: 10.1006/meth.2000.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Porcheddu A. Peptide nucleic acids (PNAs), a chemical overview. Curr Med Chem. 2005;12:2561–2599. doi: 10.2174/092986705774370664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nielsen PE. Targeting double stranded DNA with peptide nucleic acid (PNA) Curr Med Chem. 2001;8:545–550. doi: 10.2174/0929867003373373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paulasova P, Pellestor F. The peptide nucleic acids (PNAs): a new generation of probes for genetic and cytogenetic analysis. Ann Genet. 2004;47:349–358. doi: 10.1016/j.anngen.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luo JD, Chan AC, Shih CL, Chen TL, Liang Y, Hwang TL. Chiou, Detection of rare mutant K-ras DNA in a single-tube reaction using peptide nucleic acid as both PCR clamp and sensor probe. Nucl Acids Res. 2006;34:e12. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnj008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Demidov VV. PNA and LNA throw light on DNA. Trends Biotech. 2003;21:4–7. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(02)00008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geng L, Zhonghua Y, Xue Y, Chuan Xue, Za Zhi. Cloning the 5′ end fragment of ST13 cDNA by nested PCR. Chin J Med Genet. 1999;16:174–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watzka M. An optimized protocol for mRNA quantification using nested competitive RT-PCR. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1997;231:813–817. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Husnjak K. Comparison of five different polymerase chain reaction methods for detection of human papillomavirus in cervical cell specimens. J Virol Meth. 2000;88:125–34. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(00)00194-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keech CL, Farris AD, Beroukas D, Gordon TP, McCluskey J. Cognate T cell help is sufficient to trigger anti-nuclear autoantibodies in naïve mice. J Immunol. 2001;166:5826–34. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.9.5826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Furuta K, Misao S, Takahashi K, Tagaya T, Fukuzawa Y, Ishikawa T, Yoshioka K, Kakumu S. Gene mutation of transforming growth factor beta 1 type II receptor in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 1999;81:851–853. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990611)81:6<851::aid-ijc2>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ali IU, USchriml LM, Dean M. Mutational spectra of PTEN/MMAC1 gene: a tumor suppressor with lipid phosphatase activity. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1922–1932. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.22.1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang YT, Liu HN, Shiao YM, Lin MW, Lee DD, Liu MT, Wang WJ, Wu S, Lai CY. A study of PSORS1C1 gene polymorphisms in Chinese patients with psoriasis. Brit J Dermatol. 2005;153:90–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]