Summary

Smad proteins are key signal transducers for the TGF-β superfamily and are frequently inactivated in human cancers, yet the molecular basis of how their levels and activities are regulated remains unclear. Recent progress, discussed herein, illustrates the critical roles of Smad post-translational modifications in the cellular outcome to TGF-β signaling.

1. Introduction

TGF-β superfamily signaling controls a diverse set of cellular responses, including cell proliferation, differentiation, extracellular matrix remodeling, and embryonic development [1]. Consequently, when not strictly controlled, TGF-β signaling can play a key role in the pathogenesis of cancer and fibrotic, cardiovascular and autoimmune diseases [2–5]. Much progress in the field has been made since the discovery of Smad proteins as the transcription factors that transduce TGF-β signals. Thus, it is now possible to articulate a comprehensive model for how conceptually simple Smads control this broad range of cellular outcomes, in response to a large family of TGF-β ligands including TGF-βs, activins and BMPs [6, 7]. Recent data, some of which seem controversial, suggest that Smad signaling is fine-tuned to regulate diverse TGF-β-mediated biological responses through post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation, ubiquitination, SUMOylation and acetylation, as discussed in detail in this review. Critical roles of Smad post-translational modifications are underscored by their functional consequence on TGF-β anti-proliferative and transcriptional responses.

2. Phosphorylation and Dephosphorylation of R-Smads at the C-terminal SXS Motif

The Smad family comprises 8 Smad proteins which are classified into three subgroups: receptor-activated Smads (R-Smads), the common Smad (Smad4), and the inhibitory Smads (I-Smads; Smad6 and Smad7). Among R-Smads, Smad2 and Smad3 are thought to be specific for TGF-β and activin ligand signaling, whilst Smads 1, 5 and 8 transduce BMP signals. As its name suggests, Smad4 is common to both branches of TGF-β superfamily signaling.

TGF-β superfamily members signal through heteromeric complexes of type II (TβRII) and type I (TβRI) transmembrane serine/threonine kinases (Figure 1). Within this receptor complex the cytoplasmic domain of TβRII is constitutively active, and phosphorylates TβRI on serine and threonine residues in the GS domain in response to ligand binding. Activated TβRI then phosphorylates R-Smads in the distal C-terminal SXS motif, which is the key step in these signaling pathways. The specificity for Smad phosphorylation lies in distinctive structural features in paired type I receptors and R-Smads [6–8]. It is remarkable how Smad2/3 SXS phosphorylation subsequently controls a cascade of ligand-specific downstream events, including their hetero-oligomeric complex formation with Smad4, and the nuclear accumulation of this complex which regulates gene transcription in conjunction with a variety of transcriptional cofactors [9, 10] (Figure 1). The interactions of Smads with DNA-binding transcription factors and transcriptional co-activators and co-repressors, as well as the target genes and resulting biological responses, have been recently reviewed in detail [9, 11]. Perhaps the most commonly referred to TGF-β transcriptional response is the up-regulation of cyclin dependent kinase inhibitors p15 [12, 13] and p21 [14, 15] in epithelial cells, following TGF-β-induced Smad2/3 SXS phosphorylation, which results in TGF-β-mediated growth arrest. Although TβRs can also signal via non-Smad targets, such as p38 and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) MAPKs [6, 16], most of the TGF-β-regulated cellular responses are mediated through the transcriptional functions of Smads. Furthermore, whilst it is accurate to say that R-Smad SXS phosphorylation is essential for their transcriptional activation, additional post-translational modifications clearly work in concert to control their final ability to transduce TGF-β signals.

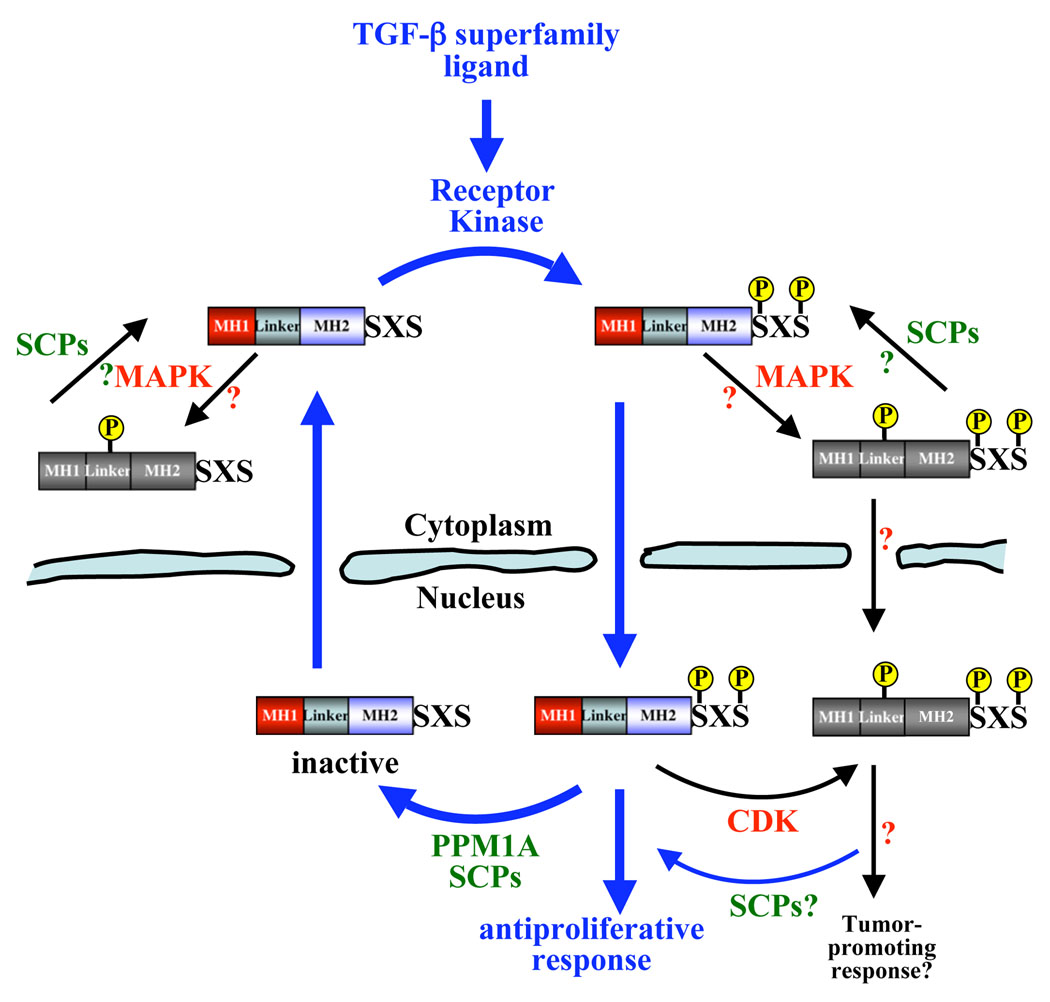

Figure 1. Regulation of R-Smads by (de)phosphorylation.

The type I receptor kinase phosphorylates the C-terminal distal SXS motif of R-Smads in response to ligand. This is the key step in initiating signal transduction. PPM1A has recently been identified as the serine/threonine phosphatase that dephosphorylates the phospho-SXS in Smad1/2/3, and SCPs 1, 2 and 3 as phosphatases that can dephosphorylate the phospho-SXS in Smad1 as well as the Smad1/2/3 linker. The exact localization of R-Smad linker phosphorylation by MAPK, and linker dephosphoryation by SCPs, is not known.

As TGF-β superfamily signaling activates a broad range of cellular responses, it stands to reason that signaling via the activated Smad complex must be stringently controlled to allow for normal cellular responses and the maintenance of tissue homeostasis. As R-Smad C-terminal SXS phosphorylation is the key step in activating Smad-mediated transcription, two possible mechanisms to terminate Smad functions in the nucleus can be envisioned: phosphatase-mediated dephosphorylation or ubiquitination-dependent degradation of phosphorylated R-Smads. The nuclear export of R-Smads has been shown to depend on their dephosphorylation and the subsequent dissociation of Smad complexes [7, 17–19]. There is also experimental support that activated R-Smads undergo faster degradation in the nucleus [20–22] (discussed later), although phospho-Smad degradation alone as a signal termination mechanism does not account for the constant level of total R-Smads, or the nuclear export of inactive Smad molecules. Indeed, as a result of several recent and significant studies it is now possible to describe how dephosphorylation, by specific phosphatases, can act as a critical regulatory mechanism in the termination of Smad signaling.

Using a functional genomic approach, Lin et al. identified PPM1A/PP2Cα as a Smad2/3 SXS-motif specific phosphatase. PPM1A/PP2Cα over-expression abolished Smad2/3 phosphorylation induced by constitutively active TβRI, whereas shRNA-mediated depletion of PPM1A/PP2Cα increased the durability of Smad2/3 SXS-phosphorylation. Importantly, this was reflected by the TGF-β-mediated biological response with PPM1A/PP2Cα over-expression abolishing, and PPM1A/PP2Cα depletion enhancing, TGF-β-induced anti-proliferative and transcriptional outcomes. Furthermore, PPM1A/PP2Cα was shown to bind (phospho-)Smad2/3, having higher affinity for the phospho-species, and to promote nuclear-export of phospho-Smad2/3 to the cytosol [23]. Although PPM1A/PP2Cα remains the only Smad2/3-SXS-motif-directed phosphatase identified thus far, it is possible that others remain unknown. Indeed, although PPM1A/PP2Cα has also been shown to dephosphorylate the C-terminal SXS of phospho-Smad1 [24], with PPM1A/PP2Cα over-expression and depletion abolishing and enhancing BMP responses respectively, it is not unique in its ability to do so. In Xenopus embryos Small C-terminal Domain Phosphatases (SCPs) 1, 2 and 3 were found to cause selective SXS dephosphorylation of phospho-Smad1, as compared with phospho-Smad2, inhibiting Smad1-dependent transcription and altering normal embryo development [25]. Additionally an RNAi screen for the Drosophila MAD phosphatase in D. melanogaster S2 cells identified Protein Pyruvate Phosphatase (PDP) as such, and PDP was shown to inhibit DPP signal-transduction [26]. In human cells RNAi-mediated depletion of SCP1 and SCP2 [25], and PDP [26], increased the level (and duration in the case of SCPs) of Smad1 phosphorylation. However, over-expression of mammalian SCPs and PDPs did not reduce Smad1 SXS phosphorylation when compared with PPM1A/PP2Cα [24], thus these phosphatases may require additional cofactors in over-expression studies.

Regardless of how many R-Smad C-terminal SXS phosphatases are identified in the future, the exciting discovery of the phosphatases thus far opens up an entirely new and critical level of TGF-β superfamily signaling research in both normal cells and diseases.

3. Phosphorylation and Dephosphorylation of R-Smads in the Linker

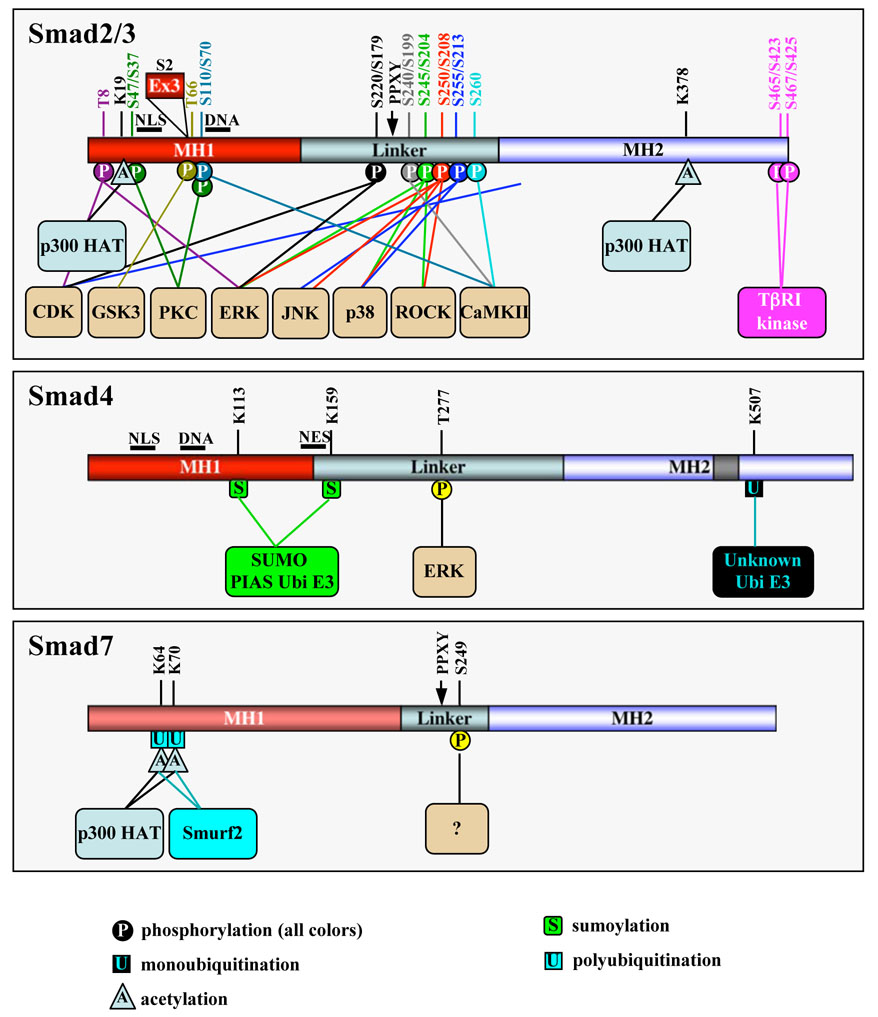

Although C-terminal SXS phosphorylation by the type I receptor is the key post-translational modification in Smad activation, phosphorylation by intracellular protein kinases can also positively and negatively regulate Smads. R-Smads contain two conserved polypeptide segments, the MH1 (N) and MH2 (C) domains, joined by a less conserved linker region. R-Smad linker regions are serine/threonine-rich and contain multiple phosphorylation sites for proline-directed kinases. They are phosphorylated by mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) and cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), which exhibit some preference for specific serine residues in the linker [6, 9, 16] (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Known post-translational modifications of Smads.

In the Smad2/3 box, amino acid residues are numbered in the Smad2/Smad3 order. All amino acid numbers are based on human sequences for Smad2 (NP_005892), Smad3 (NP_005893), Smad4 (NP_005350) and Smad7 (NP_005895). Note that the Smad3 sequence is incorrectly numbered in many publications. Smad2 exon 3, inserted between the NLS and DNA-binding domain is shown. Several other kinases such as CKIε and MEKK also phosphorylate R-Smads at unidentified sites. ERK also phosphorylates the linker region of BMP-activated Smad1 and perhaps Smad5/8. Smad4 contains a NES.

In the nucleus CDK2/4-mediated phosphorylation of Smad3 occurs mostly at Thr8, Thr179, and Ser213 [27]. CDK-dependent phosphorylation of Smad3 inhibits its transcriptional activity, negating the anti-proliferative action of TGF-β and serving as a novel means by which CDKs promote aberrant cell cycle progression and confer cancer cell resistance to the growth-inhibitory effects of TGF-β. Interestingly MAPK-mediated linker phosphorylation appears to have a dual role in Smad2/3 regulation. Mitogens and hyperactive Ras result in ERK-mediated phosphorylation of Smad3 at Ser204, Ser208, and Thr179, and of Smad2 at Ser245/250/255 and Thr220. Mutation of these sites increases the ability of Smad3 to activate target genes, suggesting that MAPK phosphorylation of Smad3 is inhibitory [28]. However, in contrast, ERK-dependent phosphorylation of Smad2 at the N-terminal Thr8 enhances its transcriptional activity [29]. Phosphorylation of Smad3 by p38 MAPK and ROCK (Ser204, Ser208, and Ser213) and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) (Ser208 and Ser213; analogous Ser250 and Ser255 in Smad2) may also enhance Smad2/3 transcriptional activity, suggesting that Smads and the p38/ROCK/JNK signaling pathways might cooperate in generating a more robust TGF-β response [30–32]. In accordance, a significant increase in Ser208/Ser213 phosphorylation of Smad3 is associated with late stage colorectal tumors, suggesting that the linker-phosphorylated Smad3 may mediate the tumor-promoting role of TGF-β in late tumorigenesis [33]. In BMP signaling, activated MAPK-directed phosphorylation of the Smad1 linker causes the nuclear exclusion of Smad1 even in the presence of BMP, and consequently desensitizes cells to BMP and promotes neural induction in Xenopus embryos [34]. Notably, mutant mice carrying mutations in the six potential MAPK sites of Smad1 support the inhibitory role of linker phosphorylation, and also point to additional important functions of MAPK-dependent linker phosphorylation [35]. Additional kinases, e.g. MEKK-1, CaMKII, protein kinase C, and CKε, target R-Smads and regulate Smad-dependent transcriptional responses [36–39], and TGF-β may also induce Smad phosphorylation in the linker region as well as at the SXS motif [31, 32]. Thus, the Smad linker region is emerging as an important and critical regulatory platform in the fine-tuning of TGF-β signaling.

Despite growing evidence showing phosphorylation in the linker, the exact mechanism(s) underlying how this phosphorylation regulates Smad signaling remains to be clearly elucidated. Phosphorylation in the linker may allosterically regulate intramolecular interactions between the MH1 and MH2 domains, and/or intermolecular interactions between Smads and other molecules (e.g. cytoplasmic anchors or cofactors). Which Ser/Thr residues, and to what extent they are phosphorylated, will largely be defined by accessible kinases to Smads in a specific location and at a specific time. The variety of linker kinases, regulated by many signaling pathways and even by TGF-β family members themselves, further contribute to the complex pattern of phosphorylation in the linker. The combination of sites phosphorylated may have different or even opposite consequences, and may well explain why Smad phosphorylation by the same kinase, for example ERK, can lead to opposite effects on Smad signaling in different experimental settings. Use of phospho-specific antibodies against each individual phospho-Ser/phospho-Thr residue is critical in determining both the responsible kinases, and how each single phosphorylation event contributes to Smad regulation [27]. In addition, phosphorylation in the cells cytoplasmic or nuclear compartment may have conceptually different effects even though the phosphorylation can take place on the same Ser/Thr residues. It is also conceivable that some phosphorylation may require priming kinases, and conversely, one phosphorylation may prevent other phosphorylation events. Therefore, the physiological outcome of the regulatory phosphorylation by intracellular kinases is largely context-dependent. Caution must be taken to interpret how different kinases work independently, or in concert, to regulate Smad activity in normal cells and diseases.

An additional level of complexity comes from the recent discovery of R-Smad linker phosphatases, highlighting the need to consider Smad-linker (de)phosphorylation as a dynamic and tightly controlled event. The SCP phosphatases 1, 2 and 3 were found to specifically dephosphorylate certain sites in the Smad2 (Ser245/250/255 and Thr8) and Smad3 (Ser204/208/213 and Thr8) linker/N-terminus, but to have no effect on Smad2/3 C-terminal SXS-phosphorylation [40]. It is intriguing that SCPs were unable to dephosphorylate Smad2/3 at Thr220/179, given that these sites can be phosphorylated by the same kinases as other linker/N-terminal sites, and perhaps suggests that phosphorylation at these analogous Smad2/3 sites may have a unique role which excludes them from dephosphorylation by SCPs. In fact, of 40 phosphatases screened in this study none had phosphatase activity towards Smad2/3 at Thr220/179. As well as their role in Smad1 SXS dephosphorylation SCPs also dephosphorylate Smad1 in the linker at Ser206, and presumably Ser187 and Ser195, in both mammalian cells and Xenopus embryos [41]. Importantly Sapkota et al. show that SCPs can mediate dephosphorylation of the Smad1 and Smad2 linker in mammalian cells regardless of whether the phosphorylation has occurred in response to BMP, TGFβ or EGF-activated kinases [41]. Smad2/3 linker dephosphorylation clearly results in enhanced TGF-β signaling [40, 41] consistent with earlier findings that mutation of CDK2/4 and ERK phosphorylation sites in the Smad2/3 linker increases the TGF-β response [27, 28, 42]. However, by dephosphorylating Smad1 at both the C-terminus and in the linker, SCPs terminate BMP signaling [25, 41]. The opposing role of SCPs on TGF-β and BMP signaling outcomes fits with the role of Xenopus SCP2 in promoting secondary axis development in embryos [43]; simultaneously promoting Activin signaling (via dephosphorylation of the Smad2/3 linker) and inhibiting BMP signaling (via dephosphorylation of the Smad1-SXS and linker). Thus, this biological need to differentially regulate Activin and BMP signaling in parallel seemingly explains the interesting specificity of SCPs for the Smad1, but not Smad2/3 SXS motif, and yet the more generalized role of SCPs in Smad1/2/3 linker dephosphorylation.

It is possible that additional understanding of the regulatory role of R-Smad linkers in TGF-β superfamily signaling may come from firmly connecting specific linker kinases and phosphatases in vivo, and from discovering under which physiological conditions these (de)phosphorylation events occur.

4. Regulation of R-Smads by the Ubiquitin-Proteasome Pathway and Acetylation

The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway has emerged as a common mechanism to control the turnover of many regulatory proteins involved in critical cellular processes. Ubiquitination occurs through a three-step process involving ubiquitin-activating (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating (E2), and ubiquitin-ligating (E3) enzymes, and results in covalent attachment of ubiquitin to a substrate and its subsequent degradation via the 26S proteasome. Ubiquitination can regulate TGF-β signaling by targeting components of the pathway for degradation on multiple levels.

Smurf (Smad ubiquitination-related factor) family members, namely Smurf1 and Smurf2, have been identified as C2-WW-HECT domain ubiquitin E3 ligases that target R-Smads (as well as I-Smads and associated proteins, see section 7) for proteasomal degradation [22]. Originally discovered in a yeast two-hybrid screen using Smad1 as bait, Smurf1 can ubiquitinate BMP-specific Smads 1 and 5, but not TGF-β-specific Smads 2 and 3, targeting them for degradation [44, 45]. A recent report by Sapkota et al. elegantly demonstrates how different Smad post-translational modifications can converge in regulating Smad signaling, by revealing interplay between Smad1 linker phosphorylation and Smurf1-dependent ubiquitination [46]. Smurf1 was found to selectively bind to linker-phosphorylated Smad1. Not only did this result in the ubiquitination and specific degradation of linker-phosphorylated Smad1, Smurf1 binding also blocked nucleoporin-Smad1 interactions and subsequent Smad1 nuclear translocation [46]. These data finally provide one firm mechanism as to how linker phosphorylation can restrict Smad1 activity. It will be interesting to see if Smad2/3 linker phosphorylation is also involved in the selective binding of any such regulatory factors.

Unlike Smurf1, Smurf2 appears to have broader substrate specificity, and interacts with both TGF-β and BMP regulated R-Smads. Specifically, Smurf2 has been shown to physically associate with Smad1 and Smad2 and consequently can target them both for degradation [47, 48]. Interestingly two of the R-Smads, Smad3 and Smad8, are not targeted for destruction by Smurf proteins. Whilst Smad8 lacks a PPXY motif which is required for Smurf binding, Smad3 actually has a high binding affinity for Smurf2. Thus, it seems at least for Smad3, Smurf2 E3 ligase binding alone is not sufficient to trigger ubiquitin-mediated degradation.

A role for Smurf-mediated post-translational modifications in the regulation of Smad signaling is evolutionarily conserved, and the Drosophila E3 ligase dSmurf plays an important role in signaling by Decapentaplegic (DPP), the Drosophila ortholog of human BMP. dSmurf targets the Drosophila R-Smad MAD for ubiquitin-mediated degradation and consequently causes disruption of DPP-dependent development [49, 50]. The DPP pathway is also negatively regulated by the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4A (eIF4A) which mediates activation-dependent degradation of the DPP signaling components R-Smad MAD and common Smad MEDEA [51]. Although eIF4A-mediated degradation of phosphorylated MAD was found to be independent of dSmurf, these proteins are thought to work synergistically to control the degradation of Drosophila Smad homologues. Thus, eIF4A may function as an adaptor that links Smad proteins to a degradation system independent of dSmurf.

In addition to Smurfs, distantly related WW-containing HECT E3 ligases, WWP1/Tiul1, NEDD4-2, and Itch, can also regulate the stability or activity of Smads. Whilst studies concur that WWP1/Tiul1 alone does not induce the degradation of R-Smads, but rather TβRI (see section 7), to negatively regulate TGF-β-signaling [52, 53], Seo et al. reveal that WWP1/Tiul1 can interact with the TGF-β/Smad transcriptional repressor TGIF to induce ubiquitin-dependent degradation of Smad2 [53]. Intriguingly NEDD4-2, like Smurf2, was found to bind to Smad2/3 in a ligand dependent manner, but only to induce degradation of Smad2 [54]. Finally, of particular interest, Itch provides a rarer example of how a R-Smad E3 ligase can positively regulate TGF-β signaling, as it appears to enhance Smad2 SXS phosphorylation [55]. Whilst it is proposed that Itch augments Smad2 phosphorylation by facilitating Smad2-receptor complex formation in an E3 ligase-dependent, yet proteolysis-independent manner, it cannot be ruled out that Itch promotes degradation of inhibitory Smad7, the Smad2/3 C-terminal SXS phosphatase PPM1A/PP2Cα, or the proposed type I receptor phosphatase PP1c (see section 7).

Whilst a single WW domain suffices for other HECT E3 ligases to bind PPXY motifs, the requirement of two tandem WW domains in Smurfs for Smad binding is rather intriguing. It is also known that, in addition to PPXY motifs, phospho-Ser/Thr-containing motifs can bind to WW domains. Even though there is no direct proof that the phospho-SXS motif directly binds the WW domains, Smurf family members predominately interact with ligand-activated Smads. Thus, it is tempting to speculate that the phospho-SXS motif is required for Smurf-Smad association in cells. However, inhibitory Smad7 does not have a phospho-SXS motif, but is still able to interact strongly with Smurf proteins, suggesting that this is not necessarily the case.

Despite the binding to but absence of Smad3 degradation by Smurf2 and NEDD4-2, Smad3 is still regulated by proteasomal degradation and is targeted for ubiquitination via different classes of ubiquitin E3 ligase. The first of these involves the Skp1-Cul-F-box protein (SCF) E3 ligase, an example of a multi-subunit complex that can initiate ubiquitination of a target protein. SCFs are composed of Skp1, Cul-1, a Roc/Rbx RING finger protein that interacts with Cul-1 and the E2 enzyme, and an F-box protein such as Skp2 or TrCP that confers specificity for substrate recruitment. Interaction of TGF-β-activated Smad3 with Rbx1 (also called ROC1 and Hrt1), a RING-containing component of the SCFβTrCP complex (also called SCFFbw1a), is partly responsible for Smad3 degradation [56]. Since Rbx1 is a common subunit of many SCF E3 ligases, it raises a specificity issue as to whether more than one SCF E3 ligase targets Smad3, and perhaps Smad2, for degradation. Additionally, carboxyl terminus of Hsc70-interacting protein (CHIP) serves as a U-box dependent E3 ligase that can directly mediate the ubiquitination and degradation of Smad3 [57] and also Smad1 [58]. Of note, unlike for Smurf family proteins and Rbx1, early studies indicate that CHIP may stimulate the degradation of Smad proteins independently of ligand activation. However a very recent study, which identifies lysine residues 116, 118 and 269 as CHIP-mediated ubiquitin acceptor sites in Smad1, hints that CHIP may preferentially ubiquitinate phospho-Smad1 and Smad5 [59]. As CHIP is most well known for degrading Hsp90 chaperone clients, studies suggesting it ubiquitinates Smad1 and Smad3 raise the intriguing possibility that CHIP-degraded Smads could be Hsp90 client proteins.

Although CHIP may or may not stimulate Smad degradation independently of ligand activation, a recent study evidently reveals that non-activated Smad3 does indeed undergo proteasomal degradation in response to the scaffold protein Axin and its associated kinase glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) [60]. Smad3, but not Smad2, interacts with Axin/GSK3β only in the absence of TGF-β, resulting in GSK3β dependent phosphorylation of non-activated Smad3 at Thr66 and its subsequent ubiquitination and degradation. Accordingly, Smad3 Thr66 mutants show increased protein stability and transcriptional activity [60]. This study suggests that the stability of non-activated Smad3, as well as the level of phospho-Smads, may be important in the potential of cells to respond to TGF-β.

It stands to reason that an absence of phospho-R-Smads, as a result of ubiquitination, will prevent any new activation of TGF-β signaling responses. A link between active signaling termination and ubiquitination has also been proposed in a study demonstrating that TGF-β induces proteasomal degradation of phosphorylated Smad2 in the nucleus [20]. Given its nuclear presence and interaction with phosphorylated Smad2, Smurf2 seemed a strong candidate for the E3 ligase that removes phospho-Smad2 from the nucleus. However, the isolated MH2 domain of Smad2, which lacks the linker containing the PPXY motif required for Smurf binding, also undergoes proteasomal degradation in the nucleus [20]. This suggested that an E3 ligase in addition to Smurf2 may reside in the nucleus and control degradation of activated Smad2. Indeed, the nuclear RING-domain ligase Arkadia has recently been found to directly ubiquitinate phospho-Smad2/3 in embryonic cells, leading to their proteasomal degradation, and this is coupled with their high activity [21]. As Arkadia was found never to repress, and in some cells even to enhance, signaling, the authors of this elegant study propose that Arkadia provides a mechanism for signaling termination after gene transcription. In short, they suggest that the link between activity and degradation ensures that only phospho-Smad2/3 that have already initiated gene transcription are degraded, implying a further level of sophistication on the already intricate R-Smad-ubiquitin relationship. Given the recent progress on R-Smad phosphatases as a critical mechanism for terminating TGF-β signaling it will be interesting to see how the ubiquitin-mediated degradation and dephosphorylation events of “used” phospho-R-Smads work together or independently, in any given context, to control the overall duration of Smad signaling.

Whilst the regulation of R-Smads by ubiquitination clearly has a strong negative impact on TGF-β-Smad signaling, very recent progress illustrates that R-Smad modification by acetylation may strengthen the TGF-β-mediated cellular response. Smad2/3 have been known to interact with the transcriptional co-activators p300/CBP for some time, resulting in the enhancement of Smad-mediated transcription [61–65]. A new function for this interaction has now been revealed, with several groups demonstrating that Smad2 and Smad3 are acetylated by p300/CBP in a TGF-β-dependent manner [66–68]. p300/CBP-mediated acetylation transfers acetyl coenzyme A’s acetyl moiety to a lysine residue in the acceptor protein. Smad2 acetylation may also be stimulated by P/CAF [67]. Lysines 19, 20 and 39 in the MH1 domain are required for the efficient acetylation of Smad2 [67, 68] (Figure 2). Although mutation of Lys19 also reduced p300-mediated acetylation of Smad3 [67], a major acetylation site for Smad3 appears to be Lys378 in the MH2 domain [66]. Acetylation of Smad2 was found to be significantly higher than Smad3 by two of the groups [67, 68], and all three studies indicate that Smad2/3 acetylation has a positive influence on TGF-β/Smad signaling, perhaps by improving Smad2 DNA binding, increasing Smad association with promoters, and/or facilitating Smad nuclear accumulation. Given that the degradation of inhibitory Smad7 appears to be regulated by a balance between acetylation, deacetylation and ubiquitination (see below), it seems possible that further studies could also reveal cross-talk between these lysine modifications in the regulation of R-Smads. Although mutation of Smad2 at the major acetylation site Lys19 did not affect the stability of Smad2 in a pulse-chase study [68], further experiments directly addressing Smad2 acetylation in the context of ubiquitination are needed to completely rule this out.

5. Modifications of Smad4 in Normal Cells

Smad4 is known as the common Smad as it is central to TGF-β superfamily ligand signaling, interacting with R-Smads from both major branches (TGF-β/activin and BMP) to help transduce the signal from the receptor to the nucleus. Smad4 is constitutively phosphorylated in cells [69] and although not all of the phosphorylation sites are known, ERK has been shown to phosphorylate Smad4 specifically at Thr277 (equivalent to mouse Thr276) [70]. Substitution of Thr277 to Ala results in reduced nuclear localization of Smad4 through an unknown mechanism [70]. Given the location of Thr277 in the Smad4 activation domain (SAD), and the fact that the transcriptional co-activator p300/CBP has been shown to interact with Smad4 in the SAD [71], it seems possible that Thr277 phosphorylation could also regulate Smad4-p300/CBP interactions. Importantly, despite the fact that p300/CBP-interacting R-Smads have recently been shown to undergo p300/CBP-dependent acetylation, there are no firm reports of Smad4 acetylation thus far. However, Tu et al. did observe potential Smad4 acetylation in a p300 in vitro acetylation assay comparing Smads 2, 3 and 4, although the level was much less noteworthy than that observed for Smad2. Further studies are required to establish if Smad4 is significantly acetylated or not.

Recent evidence clearly demonstrates that Smad4 is also modified by SUMO-1. Attachment of SUMO (Small-Ubiquitin-related Modifier) to a lysine residue(s) in target proteins usually alters target protein function through changes in protein stability, transcriptional activity or subcellular localization. Covalent attachment of SUMO to substrates requires an E1 activating enzyme and an E2 conjugation enzyme. Unlike for ubiquitination, an E3 enzyme is not always strictly necessary, although several classes of SUMOylation E3 enzymes are likely to contribute to SUMOylation substrate specificity and efficiency. Smad4 is modified by SUMO-1 on lysines 159 and 113 in/near the MH1 domain (Figure 2), and this SUMOylation has been shown to require the PIAS (Protein Inhibitors of Activated STAT) family member PIASy [72], PIAS1 [73, 74] or PIASxβ [74] as an E3 ligase. Smad4 SUMOylation has largely been shown to increase its stability in the nucleus and/or decrease its nuclear export, ultimately stimulating TGF-β signaling [72, 74–76]. However, SUMOylation has also been shown to decrease Smad4s transcriptional activity in some reporter assays [77], and the transcriptional co-repressor Daxx can suppress Smad4-mediated transcriptional activity by directly interacting with SUMOylated-Smad4 in a lys159 (but not lys113) SUMO dependent manner [78]. Thus, to some degree the effect of SUMOylation on Smad4 transcriptional activity may depend on the promoter and cell type, and even the SUMO E3 ligase involved. Interestingly, as well as exerting specificity in Smad4 SUMOylation, PIAS proteins can also have SUMOylation-independent functions in TGF-β signaling [79, 80]. PIAS3 can form a complex with Smads and p300/CBP to activate Smad transcriptional activity [79], whereas PIASy can inhibit TGF-β/Smad transcriptional responses through interactions with Smad proteins and histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) [80, 81]. Thus, PIAS E3 ligases have dual regulatory effects on TGF-β signaling, and this must be taken into account when studying the effect of PIAS-mediated SUMOylation on the final cellular response to TGF-β superfamily ligands.

In addition to SUMOylation, ubiquitination plays a critical role in regulating Smad4 stability and activity. Smad4 is monoubiquitinated at Lys507 in the MH2 domain L3 loop of Smad4 involved in R-Smad phospho-serine recognition. Mutational analysis indicates that Lys507 monoubiquitination enhances Smad4/R-Smad oligomerization, leading to an increase in Smad-mediated transcription [82]. In this study, as well as others, Smad4 was also found to be directly polyubiquitinated. In fact, wild type Smad4 can be degraded by the proteasome after polyubiquitination by the E3 ligase complexes Jab1 [83] and SCFβTrCP [84]. The SCF E3 ligase containing the F-box protein Skp2 (SCFSkp2) can also polyubiquitinate Smad4. Interestingly, however, whilst SCFβTrCP–mediated ubiquitination promotes degradation of Smad4, SCFSkp2 seems not to affect the stability of wild-type Smad4 but only to promote degradation of cancer-derived Smad4 mutants (discussed below). It has also been proposed that Smad4 degradation can be mediated by Smurfs via Smad2 or Smad6/7 as adaptors [85], and by the E3 ligase CHIP that can also ubiquitinate Smad1 and Smad3 [58].

As well as the role of Smad4 ubiquitination in cancer, as outlined below, a critical role for Smad4 ubiquitination in development has recently been proposed. Dupont et al. identified Ectodermin as a RING-type ubiquitin ligase for Smad4 which acts to control TGF-β and BMP signaling in Xenopus embryo development, ensuring correct developmental cell fate [86]. Depletion of Ectodermin or over-expression of Smad4 in the embryo marginal zone results in the same developmental phenotype, in agreement with the idea that Smad4 is a key Ectodermin target. Strong biochemical evidence confirms Ectodermin is a ubiquitin E3 ligase for Smad4, and the authors further demonstrate a role for this ligase in limiting TGF-β-induced anti-proliferative responses in human adult cells [86].

In short it seems that ubiquitination of Smad4 may serve several purposes. Monoubiquitination positively regulates Smad4/R-Smad oligomerization and signaling strength, whilst polyubiquitination facilitates degradation of wild-type and mutant Smad4 in both developmental and tumorigenic contexts. The importance of Smad4 regulation by phosphorylation, SUMOylation and ubiquitination events is underscored by interplay between these Smad4 post-translational modifications in cancer.

6. Interplay of Smad4 Post-Translational Modifications in Cancer Cells

Alterations in Smad4 frequently occur in human cancers. Whereas many mutations in the MH2 domain render Smad4 inactive in its signaling activity, a number of missense mutations identified in the MH1 domain provide a mechanism for tumorigenesis by causing accelerated ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis of Smad4. This provides a key example of how aberrant Smad post-translational modifications can contribute to the pathogenesis of certain diseases, including cancer (Table 1).

Table 1.

Aberrant post-translational modifications of Smads, and of proteins involved in the regulation of TGF-β superfamily signaling, are associated with various diseases. At present most of these appear to be connected with the ubiquitination and stability of the protein in question. More examples are likely to be identified in the future.

| TGF-β signaling pathway protein | Aberrant Modification | Disease Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smad2 | Increased ubiquitination of R133C. | Increased instability in colorectal cancer. | [92] |

| Increased ubiquitination and Smurf2 level. | Increased instability in nephritic glomeruli (rats). | [120] | |

| High Smurf2 expression; Low pSmad2. | Poor survival rate in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. | [121] | |

| Smad3 | Increased linker phosphorylation at Ser208/Ser213. | Correlates with late stage colorectal tumors. | [33] |

| Smad4 | Increased JNK/p38 MAPK-mediated phosphorylation of L43S and R100T; Subsequent increased ubiquitination by Skp2/βTrCP containing SCF E3 ligases. | Increased instability in pancreatic cancer cells. | [82,88,90] |

| Increased JNK/p38 MAPK-mediated phosphorylation of G65V and P130S; Subsequent increased ubiquitination by Skp2/βTrCP containing SCF E3 ligases. | Increased instability in colorectal cancer cells. | [82,88,90] | |

| Increased SCFβTrCP-mediated ubiquitination of P102L and truncation mutant. | Increased instability in acute myelogenous leukemia. | [87] | |

| Smad7 | Protected from ubiquitination by increased acetylation. | Increased stability in inflamed human gut from Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis patients. | [122] |

| Enhanced ubiquitination and degradation of Smad7; increased Smurf1/2. | Progression of kidney tubulointerstitial fibrosis (mouse model). | [123] | |

| Ski/SnoN | Enhanced ubiquitination of Ski/SnoN mediated by Smurf2. | Correlates with obstructive nephropathy. | [124,125] |

| SnoN: Resistance to TGF-β induced ubiquitin-mediated degradation. | Resistance to TGF-β induced growth arrest in esophageal cancer cells. | [126] |

Although it was initially reported that the E3 ligase complex SCFβTrCP can promote the degradation of wild type Smad4 [84], later works demonstrate a critical role for SCFβTrCP in the degradation of Smad4 mutants in acute myelogenous leukemia cells, and in pancreatic and colorectal cancer. In acute myelogenous leukemia a missense mutation in the MH1 domain (P102L) and a frameshift mutation resulting in termination of the MH2 domain, cause rapid SCFβTrCP-mediated proteasomal degradation of Smad4 [87]. Smad4 point mutations identified in pancreatic (L43S and R100T) and colorectal (G65V and P130S) cancers have a higher affinity for the βTrCP F-box protein, and consequently also show enhanced SCFβTrCP-mediated polyubiquitination and degradation as compared to wild-type Smad4 [82, 88, 89]. Significantly, Liang et al. demonstrated that R100T, G65V, and L43S mutations result in massive phosphorylation of Smad4 by JNK/p38 MAPK, causing an increased affinity of mutant Smad4 not only for βTrCP, but also for Skp2 [90]. This confirms and extends on the important role of SCF-complexed F-box proteins in mutant Smad4 hyper-degradation. Hyperactive Ras has also been shown to promote degradation of Smad4 in intestinal epithelial cells [91]. As this was dependent on ERK/MAPK activity it further highlights a link between Smad4 phosphorylation and degradation, although no ubiquitin ligase was identified in this study. Of note, Smad2 increased instability as compared to the wild-type protein is associated with an Arg133 to Cys substitution (R133C) in colorectal cancer, which is the site analogous to R100T in Smad4 [92]. It will be worth testing if a SCF E3 ligase might also contribute to increased turnover of R133C given SCFs role in the turnover of Smad4 R100T, and the fact that both SCFSkp2 and SCFβTrCP are oncogenic and often up-regulated in cancer cells. Xu et al. also found R133C and R100T ubiquitination to involve the UbcH5 family of E2 enzymes, further suggesting these Smad mutants may be ubiquitin-modified via the same enzymatic pathway and E3 ligase [92].

Interestingly, TGF-β has recently been shown to initiate the ubiquitination and degradation of Skp2, in a Smad3-dependent manner, via the anaphase promoting complex [93]. This leads to the intriguing possibility that the resistance of wild-type Smad4 to SCFSkp2-mediated degradation could be controlled, at least in part, by diminished Skp2 levels in the presence of an efficient TGF-β signal. Additionally, JNK/p38-mediated phosphorylation is apparently low or absent in wild-type Smad4, perhaps also helping to explain why Smad4 is such a stable protein in normal cells. Regardless, the existence of multiple Smad4 ubiquitin E3 ligases favoring mutant Smad4 may be a mechanism to ensure complete removal of residual Smad4 tumor suppressor activity from cancer cells, thus providing them a proliferative advantage. Of significant clinical interest, siRNA against βTrCP increases the level of both pancreatic cancer and myelogenous leukemia Smad4 mutants [87, 89], implicating βTrCP, and Smad4 E3 ligases, as potential therapeutic targets in cases of Smad4 hyper-degradation.

Whereas phosphorylation appears to be a prerequisite for the ubiquitination of Smad4 mutants, another layer of post-translational modification complexity comes from the observation that cancer-associated mutations in the MH1 domain switch Smad4 from being SUMOylated to ubiquitinated [75]. This supports the notion that the SUMOylation sites (i.e. Lys113 and/or Lys159) might also be ubiquitination sites, providing a competitive modification between these pathways. Indeed, concurrent mutations of Lys113/159 increase the stability of the R100T mutant. However, these studies do not rule out the possibility that loss of SUMOylation is attributed to an allosteric change induced by JNK/p38-mediated phosphorylation, and conversely, that the presence of a SUMO moiety in normal Smad4 prevents JNK/p38-mediated phosphorylation and subsequent SCF-mediated ubiquitination. Thus, Lys113/159 are not necessarily direct ubiquitin acceptors in Smad4. Further identification of Smad4 phospho-Ser residues and ubiquitination sties should allow us to gain further insight into the important relationship between these modifications in Smad4 stability and beyond.

7. Indirect Regulation of Smad Activity by Post-translational Modification

As well as modification of the R-Smads and Co-Smad4 directly responsible for transducing TGF-β family signals, post-translational modifications indirectly modulate Smad activity by regulating the stability and activity of other proteins involved in controlling TGF-β signaling. These proteins include inhibitory Smads, the TGF-β superfamily receptors, and transcriptional co-repressors of TGF-β signaling.

7.1 I-Smads and T β Rs

Inhibitory Smads (I-Smads) 6 and 7 function as intracellular antagonists of TGF-β signaling by forming stable interactions with active TGF-β receptors, preventing them from initiating R-Smad SXS-phosphorylation [94–96]. Smad6 is also thought to interfere with Smad1-Smad4 complex formation [97], and a role for Smad7 in recruiting the PP1C phosphatase to dephosphorylate, and thus inactivate, TβRs has been implied [98]. However, perhaps most well established is the role of Smad6/7 in initiating ubiquitin-mediated degradation of TβRs, via Smurf ubiquitin E3 ligases which can concomitantly target I-Smads and TβRs for degradation.

Smurfs 1 and 2 are thought to interact with I-Smads in the nucleus, forming a complex which is exported to the cytoplasm and recruited to TGFβ-activated receptors in lipid raft vesicles. Smad7 serves as an adaptor for Smurf2 ubiquitin ligase activity by presenting the ubiquitin E2 conjugating enzyme UbcH7 to the HECT domain of Smurf2 [99]. Recently, Wiesner et al. presented impressive data suggesting that Smad7-Smurf2 binding also relieves an intra-molecular interaction between Smurf2s HECT and C2 domains which normally serves to protect steady state levels of this ubiquitin E3 ligase and its substrates in cells [100]. The association of the Smad7-Smurf complex with active TGF-β receptors results in the ubiquitination and degradation of Smad7, the receptor, and Smurf itself, via proteasomal and lysosomal pathways [101–103]. Smurf1 has also been shown to bind to BMP-ligand type I receptors, via Smad6 and 7, to induce their ubiquitination and degradation [45], and Smurf2 may down-regulate BMP receptor complexes via Smad6 [101]. Thus, this is an interesting situation in which Smad7, and presumably Smad6, undergoes post-translational modification itself, whilst working as an adaptor to enable Smurfs to initiate the ubiquitination of TGF-β superfamily receptors and ultimately the termination of signaling upstream of R-Smads. Like Smad2, TβRI can also be degraded by the Smurf-like proteins NEDD4-2 [54] and WWP1/Tiul1 [52, 53]. Similar to Smurfs, WWP1/Tiul1 associates with Smad7 to induce its nuclear export and enhance Smad7-TβRI association, and thus ubiquitination and degradation of the receptor [52, 53]. However, unlike for Smurfs, WWP1/Tiul1 is thought to induce TβRI degradation without affecting the expression level of Smad7 [53].

It is interesting that Smurfs and Smurf-like proteins have evolved to target the TGF-β pathway at multiple levels to terminate signaling. It is possible that R-Smads are mainly ubiquitinated in their phospho-form to contribute to the termination of already initiated signaling, whereas ubiquitination of TβRs could be a mechanism for blocking signaling before it has begun. It is also an appealing idea that ubiquitination of (phospho)-R-Smads but not receptors prior to functional signaling could ensure the termination of Smad-dependent signaling, whilst allowing TβRs to signal via non-Smad targets such as p38 and ERK MAPKs [6].

In addition to Smurfs and Smurf-like molecules the nuclear RING-domain ubiquitin ligase Arkadia has been shown to degrade Smad6/7 in cooperation with the scaffold protein Axin [104, 105]. Jab1/CSN5, a component of the COP9 signalosome complex, also associates with Smad7 to cause its translocation from the nucleus to the cytoplasm and promote its ubiquitination and degradation [106]. As Jab1/CSN5 is not an E3 ubiquitin ligase itself, it must serve as an adaptor in promoting Smad7 ubiquitin-mediated degradation. In the case of Arkadia and Jab1/CSN5, degradation of inhibitory Smad7 can actually promote TGF-β signaling as, in contrast to the effect of Smurf-like proteins, Smad7 appears to be degraded independently of TβRs. Thus, this eliminates I-Smads from their inhibitory role on R-Smad-TβR interactions, whilst preserving TβRs themselves.

It is also interesting to note that the deubiquitinating enzyme UCH37 has been found to interact strongly with Smad7, leading to the deubiquitination and stabilization of TβRI and upregulation of TGF-β-dependent transcription [107]. These data implicate a role for deubiquitination in the regulation of TGF-β signaling. Given the recent headway in the reversal of Smad phosphorylation by specific phosphatases, and the fact that R-Smads, Co-Smad4, I-Smads and TβRs are all regulated by ubiquitination, this is an interesting area for future research.

Gronroos and coworkers have elegantly demonstrated that Smad7 is also subject to acetylation, on Lys64 and Lys70, as a result of interaction with the transcriptional co-activator p300 [108] (Figure 2). This acetylation antagonizes Smurf-mediated ubiquitination of Smad7, resulting in a higher concentration of Smad7 available to bind receptors and block TβR-R-Smad interactions, and possibly to increase receptor turnover as Smad7 acetylation did not alter its nuclear export and may thus not prevent Smad7/Smurf mediated degradation of the receptor. Conversely, the same group more recently found that HDAC1-mediated deacetylation of Smad7 decreases the stability of Smad7 by enhancing its ubiquitination [109]. Thus, Smad7 degradation, and TβR level and activity as a consequence, appear to be regulated by a balance between acetylation, deacetylation and ubiquitination. Another important implication of Smad7 acetylation by p300 is the possibility that Smad7 may have a role as a transcription factor in the nucleus. Indeed, Smad7 exhibits TGF-β-independent transactivation activity that is regulated by phosphorylation at Ser249 by an as yet unidentified kinase [110]. Thus, although post-translational modifications clearly regulate Smad7s stability, and subsequently its ability to regulate the ubiquitination and activity of TβRs and inhibit TGF-β signaling, further studies are needed to fully establish their role in Smad7-mediated TGF-β-independent transcription.

7.2 Transcriptional Co-Repressors

Ski and SnoN are transcriptional co-repressors of TGF-β signaling which interact with Smad2, Smad3 and Smad4, and are recruited to the Smad-binding element in many TGF-β-responsive promoters in a ligand-dependent manner [111]. Interaction of Ski/SnoN with Smads can prevent formation of the heteromeric complex between Smad2/3 and Smad4, block Smad binding to the transcriptional co-activator p300/CBP, and recruit a transcriptional repressor complex involving NCoR/mSin3A to TGF-β-target promoters. Ski/SnoN are degraded by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in response to TGF-β to allow successful signaling when necessary, but up-regulated in response to prolonged TGF-β treatment as part of a negative feedback loop. Deregulation of Ski/SnoN ubiquitination can result in its hypo-or hyper-degradation, both of which have clinical implications (Table. 1). SnoN is also SUMO-modified, although this does not influence SnoNs role as a TGF-β transcriptional suppressor, instead negatively influencing its myogenic potential in a TGF-β-independent manner [112, 113].

Several studies indicate that R-Smads act as adaptors to stimulate the ubiquitination and degradation of SnoN, thus revealing a level on which they help regulate their own signaling by triggering post-translational modification of their own repressor. Specifically, Smad3, and to a lesser extent Smad2, recruits the anaphase-promoting complex to cause the ubiquitination and degradation of SnoN [114, 115], and TGF-β has been shown to induce assembly of a Smad2-Smuf2 ubiquitin ligase complex which targets SnoN for degradation in order to allow TGF-β signaling [116]. Ski has been shown to be degraded by the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme Cdc34, in a cell cycle-dependent manner, with overexpression of dominant-negative Cdc34 stabilizing Ski and enhancing its ability to antagonize TGF-β signaling [117].

In addition to its role as an ubiquitin E3 ligase for phospho-Smad2/3 and I-Smads, Arkadia has recently been found to regulate Smad signaling by controlling Ski/SnoN stability. In a siRNA screen of 289 well-annotated human E3 ubiquitin ligases and related proteins, Levy and co-workers found that only knockdown of Arkadia abolished TGF-β-induced transcription to the same extent as knocking down the essential Smad3 and Smad4 proteins. Their data further suggest that Arkadia promotes transcription via Smad3/Smad4 binding sites, in the presence of phospho-Smad2 or phospho-Smad3, by inducing SnoN ubiquitination and degradation in response to TGF-β signaling [118]. In keeping with this idea Nagano and co-workers found that Arkadia enhanced TGF-β signaling even when its established I-Smad target Smad7 was knocked-down, suggesting that it positively influenced TGF-β signaling at another level in addition to initiating Smad7 degradation. Subsequently they also found Arkadia to target SnoN, and its family member Ski, for ubiquitination and degradation, and found Arkadia to interact with both free and Smad-complexed Ski/SnoN [119]. Thus, R-Smads can function as adaptors to initiate ubiquitination and degradation of the Ski and SnoN co-repressors, via several ubiquitin E3 ligases. Consequently they can enhance TGF-β signaling by channeling the ubiquitin proteasome pathway, in addition to their more traditional role in regulating gene transcription via complex formation with Smad4 and transcriptional co-factors.

8. Conclusion

In summary, accumulating evidence illustrates the important roles of post-translational modifications in regulating Smad functions, and ultimately the critical cellular response to TGF-β ligands. Recent advancements, such as the discovery of long sought-after Smad phosphatases throughout 2006, emphasize the importance of considering Smad post-translational modifications as dynamic and tightly controlled events. The identification of Arkadia as an E3 ligase regulating the stability of inhibitory Smad7, phospho-Smad2/3, and the TGF-β transcriptional repressors Ski/SnoN, highlights how several proteins in the TGF-β pathway may be controlled, at least in part, by the same regulator. The same is true for Smurf E3 ligases which regulate ubiquitin-mediated degradation of R-Smads, I-Smads, TGF-β receptors and TGF-β signaling co-repressors. Exactly how these multi-regulatory ligases decide which of their clients in the pathway to target, at any given time, is likely to be complex and to vary between cell type and situation.

Despite great progress in the Smad signaling field, much work is still needed to explore other types of modification such as methylation, lipidation, nitrosylation, and neddylation. Precise post-translational modification sites need to be identified, using mutagenesis, mass spectrometry, and modification-specific antibodies, and synergistic or opposing effects of modifications in a physiological setting need to be investigated. Since post-translational modifications are reversible, identification of enzymes that counteract modifications, such as phosphatases and ubiquitin and SUMO proteases, will allow further insight into the role of Smads in TGF-β physiology and disease development.

Understanding how post-translational modifications regulate Smads in normal cells, and identifying how this contributes to aberrant Smad activities in disease, may lead to novel disease treatments. Indeed, reversal of hyper-ubiquitination of Smad4 mutants from solid tumors and leukemia, using siRNA against their βTrCP E3 ligase in cell culture, highlights the genuine possibility that understanding Smad post-translational modifications has true potential for translation to the clinic.

Acknowledgements

We apologize to those whose work we could not cite due to space limitations. Work in our laboratory is supported by NIH grants to X.-H.F. (R01GM63773, R01CA108454, P50HL083794, P50DK064233), and carried out in collaboration with Dr. Xia Lin (R01DK073932). X.-H.F. is a Leukemia & Lymphoma Society Scholar.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Whitman M, Raftery L. Development. 2005;132:4205–4210. doi: 10.1242/dev.02023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akhurst RJ. Nat Genet. 2004;36:790–792. doi: 10.1038/ng0804-790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blobe GC, Schiemann WP, Lodish HF. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1350–1358. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Massague J, Blain SW, Lo RS. Cell. 2000;103:295–309. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waite KA, Eng C. Nat Rev Genet. 2003;4:763–773. doi: 10.1038/nrg1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Derynck R, Zhang YE. Nature. 2003;425:577–584. doi: 10.1038/nature02006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shi Y, Massague J. Cell. 2003;113:685–700. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00432-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dijke PT, Heldin C-H, editors. Smad Signal Transduction. New York: Springer; 2006. pp. 177–191. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feng X-H, Derynck R. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:659–693. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.022404.142018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Massague J, Seoane J, Wotton D. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2783–2810. doi: 10.1101/gad.1350705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rahimi RA, Leof EB. J Cell Biochem. 2007;102:593–608. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feng X-H, Lin X, Derynck R. EMBO J. 2000;19:5178–5193. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.19.5178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seoane J, Pouponnot C, Staller P, Schader M, Eilers M, Massague J. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:400–408. doi: 10.1038/35070086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pardali K, Kurisaki A, Moren A, ten Dijke P, Kardassis D, Moustakas A. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:29244–29256. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909467199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seoane J. Cancer Biol Ther. 2004;3:226–227. doi: 10.4161/cbt.3.2.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moustakas A, Heldin C-H. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:3573–3584. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inman GJ, Nicolas FJ, Hill CS. Mol Cell. 2002;10:283–294. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00585-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmierer B, Hill CS. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:9845–9858. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.22.9845-9858.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu L, Kang Y, Col S, Massague J. Mol Cell. 2002;10:271–282. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00586-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lo RS, Massague J. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:472–478. doi: 10.1038/70258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mavrakis KJ, Andrew RL, Lee KL, Petropoulou C, Dixon JE, Navaratnam N, Norris DP, Episkopou V. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e67. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Izzi L, Attisano L. Oncogene. 2004;23:2071–2078. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin X, Duan X, Liang YY, Su Y, Wrighton KH, Long J, Hu M, Davis CM, Wang J, Brunicardi FC, Shi Y, Chen YG, Meng A, Feng X-H. Cell. 2006;125:915–928. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duan X, Liang YY, Feng X-H, Lin X. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:36526–36532. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605169200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knockaert M, Sapkota G, Alarcon C, Massague J, Brivanlou AH. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11940–11945. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605133103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen HB, Shen J, Ip YT, Xu L. Genes Dev. 2006;20:648–653. doi: 10.1101/gad.1384706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsuura I, Denissova NG, Wang G, He D, Long J, Liu F. Nature. 2004;430:226–231. doi: 10.1038/nature02650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kretzschmar M, Doody J, Timokhina I, Massague J. Genes Dev. 1999;13:804–816. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.7.804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Funaba M, Zimmerman CM, Mathews LS. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:41361–41368. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204597200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Engel ME, McDonnell MA, Law BK, Moses HL. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:37413–37420. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.52.37413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mori S, Matsuzaki K, Yoshida K, Furukawa F, Tahashi Y, Yamagata H, Sekimoto G, Seki T, Matsui H, Nishizawa M, Fujisawa J, Okazaki K. Oncogene. 2004;23:7416–7429. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kamaraju AK, Roberts AB. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:1024–1036. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403960200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamagata H, Matsuzaki K, Mori S, Yoshida K, Tahashi Y, Furukawa F, Sekimoto G, Watanabe T, Uemura Y, Sakaida N, Yoshioka K, Kamiyama Y, Seki T, Okazaki K. Cancer Res. 2005;65:157–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Massague J. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2993–2997. doi: 10.1101/gad.1167003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aubin J, Davy A, Soriano P. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1482–1494. doi: 10.1101/gad.1202604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown JD, DiChiara MR, Anderson KR, Gimbrone MA, Jr, Topper JN. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:8797–8805. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wicks SJ, Lui S, Abdel-Wahab N, Mason RM, Chantry A. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:8103–8111. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.21.8103-8111.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yakymovych I, Ten Dijke P, Heldin C-H, Souchelnytskyi S. Faseb J. 2001;15:553–555. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0474fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Waddell DS, Liberati NT, Guo X, Frederick JP, Wang XF. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:29236–29246. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400880200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wrighton KH, Willis D, Long J, Liu F, Lin X, Feng X-H. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:38365–38375. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607246200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sapkota G, Knockaert M, Alarcon C, Montalvo E, Brivanlou AH, Massague J. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:40412–40419. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610172200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Matsuura I, Wang G, He D, Liu F. Biochemistry. 2005;44:12546–12553. doi: 10.1021/bi050560g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zohn IE, Brivanlou AH. Dev Biol. 2001;239:118–131. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu H, Kavsak P, Abdollah S, Wrana JL, Thomsen GH. Nature. 1999;400:687–693. doi: 10.1038/23293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murakami G, Watabe T, Takaoka K, Miyazono K, Imamura T. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:2809–2817. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-07-0441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sapkota G, Alarcon C, Spagnoli FM, Brivanlou AH, Massague J. Mol Cell. 2007;25:441–454. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lin X, Liang M, Feng X-H. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:36818–36822. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000580200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang Y, Chang C, Gehling DJ, Hemmati-Brivanlou A, Derynck R. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:974–979. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.3.974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liang YY, Lin X, Liang M, Brunicardi FC, ten Dijke P, Chen Z, Choi KW, Feng X-H. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:26307–26310. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300028200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Podos SD, Hanson KK, Wang YC, Ferguson EL. Dev Cell. 2001;1:567–578. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00057-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li J, Li WX. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1407–1414. doi: 10.1038/ncb1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Komuro A, Imamura T, Saitoh M, Yoshida Y, Yamori T, Miyazono K, Miyazawa K. Oncogene. 2004;23:6914–6923. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Seo SR, Lallemand F, Ferrand N, Pessah M, L'Hoste S, Camonis J, Atfi A. EMBO J. 2004;23:3780–3792. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kuratomi G, Komuro A, Goto K, Shinozaki M, Miyazawa K, Miyazono K, Imamura T. Biochem J. 2005;386:461–470. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bai Y, Yang C, Hu K, Elly C, Liu YC. Mol Cell. 2004;15:825–831. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fukuchi M, Imamura T, Chiba T, Ebisawa T, Kawabata M, Tanaka K, Miyazono K. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:1431–1443. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.5.1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xin H, Xu X, Li L, Ning H, Rong Y, Shang Y, Wang Y, Fu XY, Chang Z. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:20842–20850. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412275200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li L, Xin H, Xu X, Huang M, Zhang X, Chen Y, Zhang S, Fu XY, Chang Z. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:856–864. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.2.856-864.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li RF, Shang Y, Liu D, Ren ZS, Chang Z, Sui SF. J Mol Biol. 2007;374:777–790. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.09.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guo X, Ramirez A, Waddell DS, Li Z, Liu X, Wang XF. Genes Dev. 2008;22:106–120. doi: 10.1101/gad.1590908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shen X, Hu PP, Liberati NT, Datto MB, Frederick JP, Wang XF. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:3309–3319. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.12.3309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nishihara A, Hanai JI, Okamoto N, Yanagisawa J, Kato S, Miyazono K, Kawabata M. Genes Cells. 1998;3:613–623. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1998.00217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pouponnot C, Jayaraman L, Massague J. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:22865–22868. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.36.22865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Feng X-H, Zhang Y, Wu RY, Derynck R. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2153–2163. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.14.2153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Janknecht R, Wells NJ, Hunter T. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2114–2119. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.14.2114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Inoue Y, Itoh Y, Abe K, Okamoto T, Daitoku H, Fukamizu A, Onozaki K, Hayashi H. Oncogene. 2007;26:500–508. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Simonsson M, Kanduri M, Gronroos E, Heldin C-H, Ericsson J. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:39870–39880. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607868200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tu AW, Luo K. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:21187–21196. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700085200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nakao A, Imamura T, Souchelnytskyi S, Kawabata M, Ishisaki A, Oeda E, Tamaki K, Hanai J, Heldin C-H, Miyazono K, ten Dijke P. EMBO J. 1997;16:5353–5362. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.17.5353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Roelen BA, Cohen OS, Raychowdhury MK, Chadee DN, Zhang Y, Kyriakis JM, Alessandrini AA, Lin HY. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2003;285:C823–C830. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00053.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.de Caestecker MP, Yahata T, Wang D, Parks WT, Huang S, Hill CS, Shioda T, Roberts AB, Lechleider RJ. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:2115–2122. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.3.2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lee PS, Chang C, Liu D, Derynck R. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:27853–27863. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301755200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liang M, Melchior F, Feng X-H, Lin X. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:22857–22865. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401554200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ohshima T, Shimotohno K. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:50833–50842. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307533200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lin X, Liang M, Liang YY, Brunicardi FC, Feng X-H. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:31043–31048. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300112200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lin X, Liang M, Liang YY, Brunicardi FC, Melchior F, Feng X-H. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:18714–18719. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302243200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Long J, Wang G, He D, Liu F. Biochem J. 2004;379:23–29. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chang CC, Lin DY, Fang HI, Chen RH, Shih HM. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:10164–10173. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409161200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Long J, Wang G, Matsuura I, He D, Liu F. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:99–104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307598100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Long J, Matsuura I, He D, Wang G, Shuai K, Liu F. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9791–9796. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1733973100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Imoto S, Sugiyama K, Muromoto R, Sato N, Yamamoto T, Matsuda T. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:34253–34258. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304961200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Moren A, Hellman U, Inada Y, Imamura T, Heldin C-H, Moustakas A. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:33571–33582. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300159200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wan M, Cao X, Wu Y, Bai S, Wu L, Shi X, Wang N. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:171–176. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wan M, Tang Y, Tytler EM, Lu C, Jin B, Vickers SM, Yang L, Shi X, Cao X. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:14484–14487. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400005200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Moren A, Imamura T, Miyazono K, Heldin C-H, Moustakas A. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:22115–22123. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414027200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dupont S, Zacchigna L, Cordenonsi M, Soligo S, Adorno M, Rugge M, Piccolo S. Cell. 2005;121:87–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yang L, Wang N, Tang Y, Cao X, Wan M. Hum Mutat. 2006;27:897–905. doi: 10.1002/humu.20387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Moren A, Itoh S, Moustakas A, Dijke P, Heldin C-H. Oncogene. 2000;19:4396–4404. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wan M, Huang J, Jhala NC, Tytler EM, Yang L, Vickers SM, Tang Y, Lu C, Wang N, Cao X. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:1379–1392. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)62356-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Liang M, Liang YY, Wrighton K, Ungermannova D, Wang XP, Brunicardi FC, Liu X, Feng X-H, Lin X. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:7524–7537. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.17.7524-7537.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Saha D, Datta PK, Beauchamp RD. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:29531–29537. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100069200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Xu J, Attisano L. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:4820–4825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.9.4820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Liu W, Wu G, Li W, Lobur D, Wan Y. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:2967–2979. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01830-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Nakao A, Afrakhte M, Moren A, Nakayama T, Christian JL, Heuchel R, Itoh S, Kawabata M, Heldin NE, Heldin C-H, ten Dijke P. Nature. 1997;389:631–635. doi: 10.1038/39369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Imamura T, Takase M, Nishihara A, Oeda E, Hanai J, Kawabata M, Miyazono K. Nature. 1997;389:622–626. doi: 10.1038/39355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hayashi H, Abdollah S, Qiu Y, Cai J, Xu YY, Grinnell BW, Richardson MA, Topper JN, Gimbrone MA, Jr, Wrana JL, Falb D. Cell. 1997;89:1165–1173. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80303-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hata A, Lagna G, Massague J, Hemmati-Brivanlou A. Genes Dev. 1998;12:186–197. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.2.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Shi W, Sun C, He B, Xiong W, Shi X, Yao D, Cao X. J Cell Biol. 2004;164:291–300. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200307151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ogunjimi AA, Briant DJ, Pece-Barbara N, Le Roy C, Di Guglielmo GM, Kavsak P, Rasmussen RK, Seet BT, Sicheri F, Wrana JL. Mol Cell. 2005;19:297–308. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wiesner S, Ogunjimi AA, Wang HR, Rotin D, Sicheri F, Wrana JL, Forman-Kay JD. Cell. 2007;130:651–662. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kavsak P, Rasmussen RK, Causing CG, Bonni S, Zhu H, Thomsen GH, Wrana JL. Mol Cell. 2000;6:1365–1375. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00134-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ebisawa T, Fukuchi M, Murakami G, Chiba T, Tanaka K, Imamura T, Miyazono K. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:12477–12480. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100008200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Di Guglielmo GM, Le Roy C, Goodfellow AF, Wrana JL. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:410–421. doi: 10.1038/ncb975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Liu W, Rui H, Wang J, Lin S, He Y, Chen M, Li Q, Ye Z, Zhang S, Chan SC, Chen YG, Han J, Lin SC. EMBO J. 2006;25:1646–1658. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Koinuma D, Shinozaki M, Komuro A, Goto K, Saitoh M, Hanyu A, Ebina M, Nukiwa T, Miyazawa K, Imamura T, Miyazono K. EMBO J. 2003;22:6458–6470. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kim BC, Lee HJ, Park SH, Lee SR, Karpova TS, McNally JG, Felici A, Lee DK, Kim SJ. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:2251–2262. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.6.2251-2262.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wicks SJ, Haros K, Maillard M, Song L, Cohen RE, Dijke PT, Chantry A. Oncogene. 2005;24:8080–8084. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Gronroos E, Hellman U, Heldin C-H, Ericsson J. Mol Cell. 2002;10:483–493. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00639-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Simonsson M, Heldin C-H, Ericsson J, Gronroos E. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:21797–21803. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503134200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Pulaski L, Landstrom M, Heldin C-H, Souchelnytskyi S. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:14344–14349. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011019200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Luo K. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2004;14:65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wrighton KH, Liang M, Bryan B, Luo K, Liu M, Feng X-H, Lin X. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:6517–6524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610206200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hsu YH, Sarker KP, Pot I, Chan A, Netherton SJ, Bonni S. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:33008–33018. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604380200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Wan Y, Liu X, Kirschner MW. Mol Cell. 2001;8:1027–1039. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00382-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Stroschein SL, Bonni S, Wrana JL, Luo K. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2822–2836. doi: 10.1101/gad.912901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Bonni S, Wang HR, Causing CG, Kavsak P, Stroschein SL, Luo K, Wrana JL. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:587–595. doi: 10.1038/35078562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Macdonald M, Wan Y, Wang W, Roberts E, Cheung TH, Erickson R, Knuesel MT, Liu X. Oncogene. 2004;23:5643–5653. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Levy L, Howell M, Das D, Harkin S, Episkopou V, Hill CS. Mol Cell Biol. 2007 doi: 10.1128/MCB.00664-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Nagano Y, Mavrakis KJ, Lee KL, Fujii T, Koinuma D, Sase H, Yuki K, Isogaya K, Saitoh M, Imamura T, Episkopou V, Miyazono K, Miyazawa K. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:20492–20501. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701294200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Togawa A, Yamamoto T, Suzuki H, Fukasawa H, Ohashi N, Fujigaki Y, Kitagawa K, Hattori T, Kitagawa M, Hishida A. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:1645–1652. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63521-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Fukuchi M, Fukai Y, Masuda N, Miyazaki T, Nakajima M, Sohda M, Manda R, Tsukada K, Kato H, Kuwano H. Cancer Res. 2002;62:7162–7165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Monteleone G, Del Vecchio Blanco G, Monteleone I, Fina D, Caruso R, Gioia V, Ballerini S, Federici G, Bernardini S, Pallone F, MacDonald TT. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1420–1429. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Fukasawa H, Yamamoto T, Togawa A, Ohashi N, Fujigaki Y, Oda T, Uchida C, Kitagawa K, Hattori T, Suzuki S, Kitagawa M, Hishida A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:8687–8692. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400035101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Tan R, Zhang J, Tan X, Zhang X, Yang J, Liu Y. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2781–2791. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005101055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Fukasawa H, Yamamoto T, Togawa A, Ohashi N, Fujigaki Y, Oda T, Uchida C, Kitagawa K, Hattori T, Suzuki S, Kitagawa M, Hishida A. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1733–1740. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Edmiston JS, Yeudall WA, Chung TD, Lebman DA. Cancer Res. 2005;65:4782–4788. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]