Abstract

A combined proton relaxivity and dynamic light scattering study has shown that aggregates formed in aqueous solution of water-soluble gadofullerenes can be disrupted by addition of salts. The salt content of fullerene-based materials will strongly influence properties related to aggregation phenomena, therefore their behavior in biological or medical applications. In particular, the relaxivity of gadofullerenes decreases dramatically with phosphate addition. Moreover, real biological fluids present a rather high salt concentration which will have consequences on fullerene aggregation and influence fullerene-based drug delivery.

Water-soluble fullerene derivatives possess potential for biomedical applications as antioxidants,1 anti-HIV drugs,2 X-ray contrast agents,3 bone-disorder drugs4,5 and photosensitizers for photodynamic therapy.6 In addition, endohedral metallofullerenes (M@C2n) have been suggested as nuclear medicines (M = Ho3+)7,8, fluorescent tracers (M = Er3+)9 and MRI contrast agents (M = Gd3+)10-13 largely because the closed fullerene cage insures against toxic metal-ion release in vivo. Water-soluble members of the Gd@C60 family of metallofullerenes have recently been shown to achieve their large proton relaxivities (r1) though pH-controlled self-aggregation.13,14 In fact, self-aggregation may well be a common feature of all water-soluble fullerene chemistry,15-17 and its understanding is, therefore, of general importance for fullerene-based drug delivery. In this communication, we report that proton relaxivity measurements for the water-soluble metallofullerenes, Gd@C60[C(COOH)2]10 and Gd@C60(OH)x (x≈27), can be used as a reporter to probe the aggregation (or disaggregation) characteristics of water-soluble fullerene materials in the presence of physiologically-encountered agents.

The proton relaxivity, r1, which is the gauge of contrast agent efficiency, is remarkably higher (up to 10 times) for gadofullerenes than for typical clinical agents (r1 is the paramagnetic longitudinal relaxation rate enhancement of water protons, referred to 1 mM concentration).10-13 The electronic structure of Gd@C60 involves the transfer of three electrons from the Gd atom to the cage resulting in seven unpaired electrons on the Gd3+ center and one unpaired electron on the cage. The large relaxivity of the gadofullerenes has been attributed to their slow tumbling in solution and to the large number of surrounding water molecules.13 This slow tumbling/rotation is related to aggregation phenomena in aqueous solution, and recently, in a variable-pH proton relaxation and dynamic light scattering (DLS) study, we confirmed a pH-dependent aggregation of the gadofullerenes and proposed them as pH-responsive MRI contrast agents.13

With the aim of assessing the interaction between the aggregated gadofullerenes, Gd@C60(OH)x and Gd@C60[C(COOH)2]1011,13 and physiologically encountered agents, we have carried out relaxivity measurements in the presence of human serum albumin (HSA) (4.5%) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4) at 60 MHz. The Solomon-Bloembergen-Morgan theory predicts that at this field r1 is mainly determined by molecular rotation and tumbling and thus an interaction with HSA should lead to slower rotation and a subsequent relaxivity increase.18 Surprisingly, the relaxivity decreased strongly in phosphate-buffered HSA in comparison to salt-free gadofullerene solutions (r1=43.1 vs. 83.2 mM-1 s-1 for Gd@C60(OH)x; r1=17.2 vs. 24.0 mM-1 s-1 for Gd@C60[C(COOH)2]10). We attribute this relaxivity decrease to the disaggregation of the gadofullerene aggregates due to the presence of the salt.

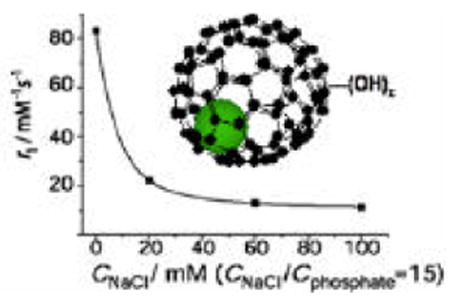

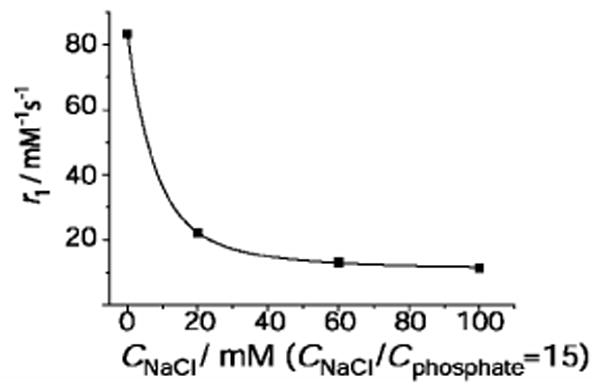

Relaxivity is an ideal reporter of aggregation phenomena in paramagnetic solutions, as previously demonstrated in micellization of amphiphilic Gd3+ chelates.19 Disaggregation of the gadofullerenes leads to smaller and more rapidly tumbling entities, which will directly translate into lower relaxivities. On increasing PBS concentration in a gadofullerene solution, the relaxivity, indeed, decreases dramatically, indicating aggregate disruption (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

1H relaxivity of Gd@C60(OH)x at variable PBS concentration; pH 7.4, 37°C and 60 MHz (cGd=0.5 mM). The curve is a guide to the eye.

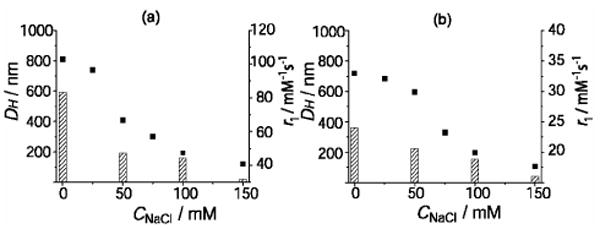

In order to separate the disaggregating effect of phosphate and sodium chloride in PBS, we have performed a relaxometric and DLS study of gadofullerene solutions at variable NaCl concentration (no phosphate). As Figure 2 shows, the relaxivity decrease on NaCl addition is also accompanied by a decrease of the hydrodynamic diameter, DH, thus confirming disaggregation as the most likely reason for the decrease in relaxivity.

Figure 2.

Hydrodynamic diameters (left y-axis, ■) and 1H relaxivities (right y-axis, histograms) of Gd@C60(OH)x (cGd=0.5 mM) (a) and Gd@C60[C(COOH)2]10 (cGd=0.4 mM) (b) aqueous solutions at variable NaCl concentration; pH 7.4, 37°C, 60MHz.

The potential of NaCl to disrupt aggregation is limited in comparison to phosphate. Disaggregation is not exclusively related to ionic strength, but rather it is more efficient in 10 mM phosphate than in 150 mM sodium chloride (r1=14.1 mM-1s-1 and DH=90.9 nm vs. r1=31.6 mM-1s-1 and DH=120.8 nm, respectively for Gd@C60(OH)x, and r1=16.0 mM-1s-1 and DH=107.0 nm vs. r1=6.80 mM-1s-1 and DH=31.6 nm for Gd@C60[C(COOH)2]10).

Halide anion size also seems to be unimportant since identical relaxivities were obtained with NaCl, NaBr and NaI. Although the disaggregation mechanism remains unclear, the specific effect of phosphate might be related to the intercalation of H2PO4- and HPO42- ions (pH 7.4) into the hydrogen-bond network around the malonate or OH-groups of the gadofullerenes. Phosphate has a tendency to create strong hydrogen bonds. If fullerenes aggregation is mainly due to hydrophobic forces, the intercalation with phosphate may separate the molecules and inhibit those interactions.

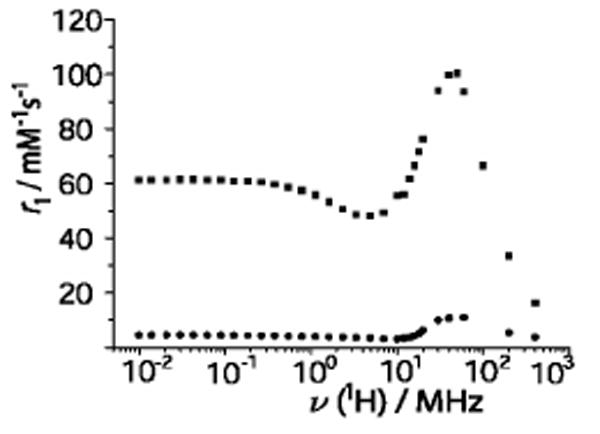

A Nuclear Magnetic Relaxation Dispersion (NMRD) profile measures relaxivities as a function of magnetic field, and is widely used to characterize MRI contrast agents.18 At all magnetic fields, r1 of Gd@C60(OH)x (and Gd@C60[C(COOH)2]10) is remarkably lower in 100 mM phosphate than in pure water (Figure 3). In addition to the diminution of the rotational correlation time, disaggregation might also affect other parameters influencing relaxivity, such as electronic relaxation, or proton exchange between sites in the proximity of the paramagnetic center and the bulk. The relaxivity hump at ∼60 MHz, characteristic of slow tumbling, largely decreases in intensity in phosphate solution, but does not disappear completely.

Figure 3.

1H NMRD profiles of Gd@C60(OH)x without (upper plot) and with 100 mM phosphate (lower plot); pH 7.4 and 25°C (cGd=0.5 mM).

Disruption of the gadofullerene aggregates is not instantaneous upon salt addition. In PBS or mice serum, r1 of gadofullerenes is still changing even after one day following sample preparation. Although the kinetic curves could not be fit by monoexponential functions, disaggregation half-lives were estimated as 30 and 45 min at 37 °C for Gd@C60(OH)x in PBS and serum, respectively, and 25 min at 37 °C for Gd@C60[C(COOH)2]10 (in both media). These long half-lives imply that a gadofullerene contrast agent injected into the blood stream will be mainly present in aggregated (high relaxivity) form during the time of a typical MRI examination. The phosphate concentration in human blood plasma is only 0.38mM, much lower than that used in this study.20 In conclusion, a 1H NMRD/DLS study has shown that aggregates formed in aqueous solution of water-soluble gadofullerenes can be disrupted by addition of salts. In this respect, phosphate is much more efficient than sodium halides. The different synthetic methods of preparing water-soluble gadofullerenes may involve varying amounts of salts and some may remain in the sample after purification. This could influence the observed relaxivities and may explain the diversity of r1 values reported in the literature (e.g. Zhang et al. reported 47 mM-1 s-1 (25°C, 9.4 T),21 Wilson et al. 20 mM-1 s-1 (40 °C, 0.47 T),22 and Shinohara et. al. 81 mM-1 s-1 (25°C, 1.0 T)12 for Gd@C82(OH)x). The present study has important implications not only for the development of gadofullerene-based MRI contrast agents, but for biological or medical application of fullerene-based materials. Phosphate buffers, widely used for in vitro tests to mimic biological conditions, will strongly influence properties related to aggregation phenomena. Moreover, real biological fluids present a rather high salt concentration which will also modify the behavior of fullerene aggregation and thereby influence fullerene-based drug delivery.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation and the Office for Education and Science, and was carried out in the EC COST Action D18 and the European-funded EMIL program. Research at Rice University and TDA, Inc. was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (Grant NIH 1 R01 EB00703-01) and the Robert A. Welch Foundation (Grant C-0627/LJW).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental relaxivity and DLS data as a function of PBS, NaCl and phosphate concentration, kinetics in PBS and serum, NMRD profiles of aggregated and disaggregated form. Figures (S1-S3) of kinetic measurements of Gd@C60(OH)x.

References

- 1.Jin H, Chen WQ, Tang XW, Chiang LY, Yang CY, Schloss JV, Wu JY. J Neurosci Res. 2000;62:600–607. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20001115)62:4<600::AID-JNR15>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedman SH, DeCamp DL, Sijbesma RP, Srdanov G, Wudl F, Kenyon GL. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:6506–6509. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wharton T, Wilson LJ. Biorg Med Chem. 2002;10:3545–3554. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(02)00252-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gonzalez KA, Wilson LJ, Wu W, Nancollas GH. Biorg Med Chem. 2002;10:1991–1997. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(02)00049-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mirakyan AL, Wilson LJ. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans II. 2002;6:1173–1176. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamakoshi Y, Umezawa N, Ryu A, Arakane K, Miyata N, Goda Y, Masumizu T, Nagano T. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:12803–12809. doi: 10.1021/ja0355574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cagle DW, Kennel SJ, Mirzadeh S, Alford JM, Wilson LJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:5182–5187. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.5182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thrash TP, Cagle DW, Alford JM, Wright K, Ehrhardt GJ, Mirzadeh S, Wilson LJ. Chem Phys Lett. 1999;308:329–336. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Macfarlane RM, Wittmann G, van Loosdrecht PHM, de Vries M, Bethune DS, Stevenson S, Dorn HC. Phys Rev Lett. 1997;79:1397–1400. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kato H, Kanazawa Y, Okumura M, Taninaka A, Yokawa T, Shinohara H. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:4391–4397. doi: 10.1021/ja027555+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bolskar RD, Benedetto AF, Husebo LO, Price RE, Jackson EF, Wallace S, Wilson LJ, Alford JM. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:5471–5478. doi: 10.1021/ja0340984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mikawa M, Kato H, Okumura M, Narazaki M, Kanazawa Y, Miwa N, Shinohara H. Bionconjugate Chem. 2001;12:510–514. doi: 10.1021/bc000136m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tóth É, Bolskar RD, Borel A, Gonzalez G, Helm L, Merbach AE, Sitharaman B, Wilson LJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:799–805. doi: 10.1021/ja044688h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sitharaman B, Bolskar RD, Rusakova I, Wilson LJ. Nano Lett. 2004;4:2373–2378. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeng US, Lin TL, Chang TS, Lee HY, Hsu CH, Hsieh YW, Canteenwala T, Chiang LY. Prog Colloid Polym Sci. 2001;118:232–237. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rudalevige T, Francis AH, Zand R. J Phys Chem A. 1998;102:9797–9802. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guldi DM. J Phys Chem A. 1997;101:3895–3900. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tóth É, Helm L, Merbach AE. Relaxivity of Gadolinium(III) Complexes: Theory and Mechanism. In: Tóth É, Merbach AE, editors. The Chemistry of Contrast Agents in Medical Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Wiley; Chichester: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nicolle GM, Tóth É, Eisenwiener KP, Mäcke HR, Merbach AE. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2002;7:757–769. doi: 10.1007/s00775-002-0353-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.May PM, Linder PW, Williams DR. J Chem Soc, Dalton Trans. 1977;6:588–595. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang S, Sun D, Li X, Pei F, Liu S. Fullerene Sci Technol. 1997;5:1635–1643. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilson LJ. J Interface. 1999;8:24–28. [Google Scholar]