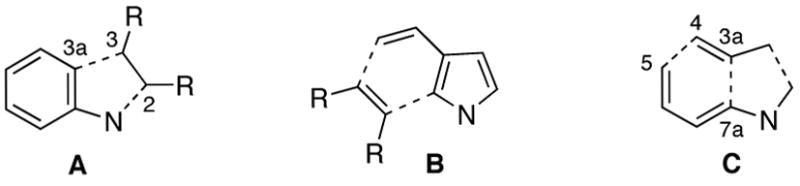

Indoles are arguably the most important of all the privileged structures in drug discovery.1 Accordingly, the development of new methods for the synthesis of indoles has been extensively investigated.2 These strategies can be broadly categorized based upon the order in which the individual aromatic substructures are introduced. By far the most common approach (A, Figure 1) involves beginning the synthesis with a substituted benzene ring. The venerable Fischer indole synthesis is an example of this strategy wherein the indicated C(3)-C(3a) and N-C(2) bonds are sequentially formed. A less common approach to substituted indoles is through the annelation of pyrroles (B, Figure 1), for example, the cycloaddition of 3-vinyl pyrroles with dienophiles.

Figure 1.

Strategies for Indole Synthesis

The third and least explored strategy for the construction of indoles is one in which both aromatic rings of the indole are constructed in consecutive bond forming processes from acyclic precursors. One of many hypothetical disconnections is formulated in structure C. Indeed, the majority of the examples2b of this overall strategy employ the implied intramolecular cycloaddition3 as the key step in the construction of the substituted benzene ring. We report herein a new approach to indoles which exploits a Stille coupling to form the C(3a)-C(7a) bond of C followed by a novel electrocyclic ring closure of the resulting trienecarbamate which effects the connection of C(4) with C(5). Finally, condensation of a C(2) enolate upon a C(3) carbonyl completes the heterocycle construction.

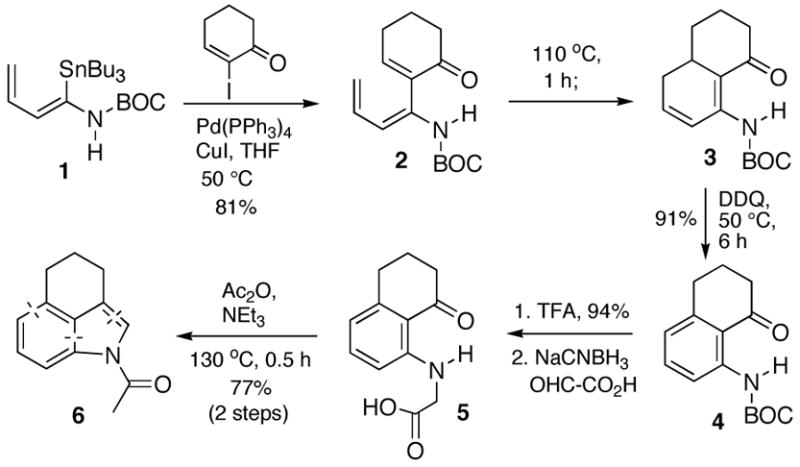

The feasibility of this strategic plan was easily demonstrated and is detailed in Scheme 1. Thus, Stille coupling of α-(tributylstannyl)enecarbamate 14 with 2-iodo-cyclohexenone proceeded smoothly to afford amidotriene 2. More importantly, triene 2 was found to undergo an especially facile electrocyclic ring closure5 (110 °C, 1 h) to furnish cyclohexadiene 3. This closure is most likely facilitated by a push/pull type mechanism of the hydrogen bonded enecarbamate functionality with the proximal carbonyl group en route to the resonance stabilized vinylogous imide product.6 Indeed, we found that the electrocyclic ring closure of a triene analogous to 2 that lacks the carbonyl group and possesses an N-methyl substituent requires higher temperatures and prolonged reaction times (120 °C, 12 h).7 Not surprisingly, the electron rich cyclohexadiene 3 can be easily oxidized to the protected aniline 4 by DDQ. This aromatization can be conveniently accomplished in the same pot once the electrocyclization is observed to be complete by TLC.

Scheme 1.

Removal of the BOC group with TFA was uneventful and a reductive amination of the resultant aniline with glyoxylic acid provided acid 5. It was hoped that this compound would cyclize to an indole upon subjection to conditions (Ac2O, NEt3, 130 °C) that were reported by Råileanu and coworkers8a for the cyclization of the analogously substituted ortho-aminobenzaldehyde to N-acetylindole. Indeed, this underutilized transformation proceeded smoothly to deliver the desired N-acetylindole 6. This cyclization could possibly be proceeding through a Perkin-type reaction of the mixed anhydride derivative of acid 5, or more likely, through a münchnone intermediate generated from the acetylated derivative of aniline 5.8b,c

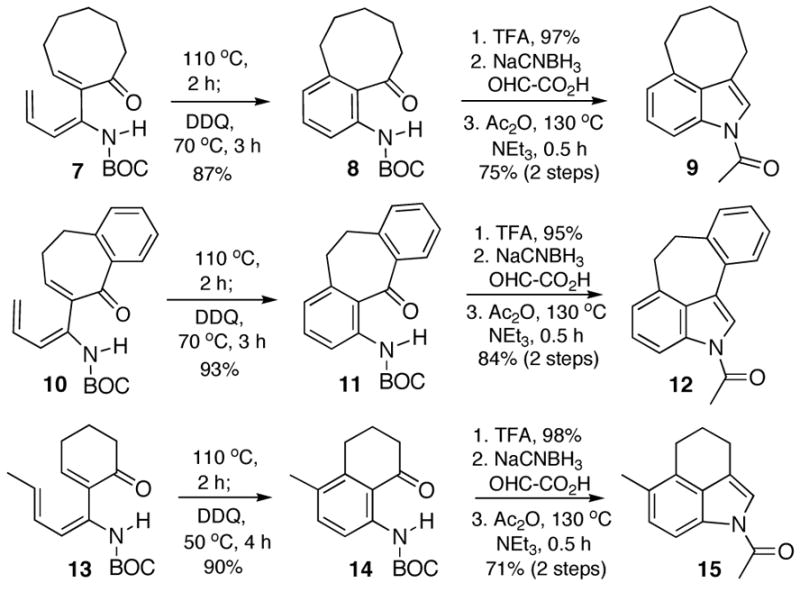

We next directed our attention to delineating the scope and generality of this new indole annelation. Our proof-of-principle example suggested that this method would be especially useful for constructing indoles that are bridged at the C(3) and C(4) positions, a substructure that complicates the synthesis of many indole natural products. To that end, the corresponding α-iodocycloalkenones were coupled with stannane 1 to afford trienecarbamates 7 and 10 (Scheme 2) and these substrates were subjected to the previously described reaction sequence to afford the heretofore unknown indole-containing ring systems 9 and 12, respectively. The trienecarbamate 13 was also prepared from a methylated analog of stannane 1 and transformed to indole 15 in order to demonstrate that additional substitution at C(5) is accessible by straightforward adaptation of this strategy.

Scheme 2.

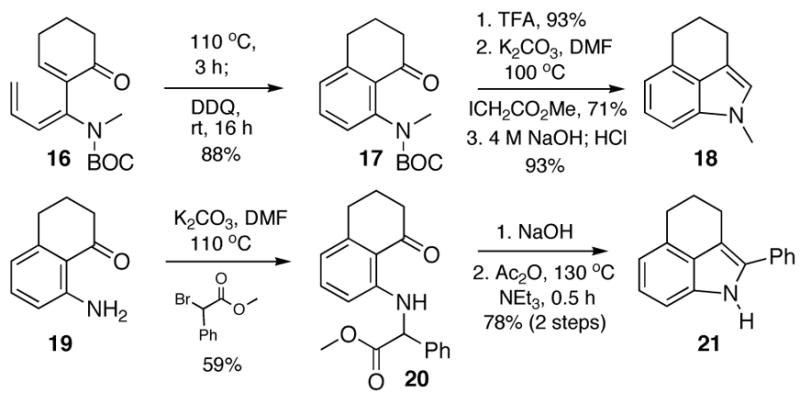

It was also of interest to determine whether the Råileanu closure would tolerate the incorporation of substituents at N or C(2) of the product indole. With respect to the former question, the electrocyclic ring closure of trienecarbamate 16 (Scheme 3) proceeded as expected, although a longer reaction time (110 °C, 3 h) was required in comparison to triene 2, presumably due to a lack of hydrogen bonding of the enecarbamate with the proximal carbonyl. After oxidation, removal of the BOC protecting group, and alkylation with methyl iodoacetate, the resultant ester was hydrolyzed with 4 M NaOH. To our surprise, we obtained clean conversion to the N-methyl indole 18 upon acidic workup with HCl. Preparation of a 2-substituted indole was accomplished through alkylation of the previously prepared aniline 19 (Scheme 1) with methyl α-bromophenylacetate to afford ester 20. Saponification of the ester, followed by subjection of the resultant acid to the Råileanu conditions afforded the desired 2-phenyl indole 21, albeit lacking the acetyl moiety, which suggests that a münchnone intermediate may not be involved in this particular closure.

Scheme 3.

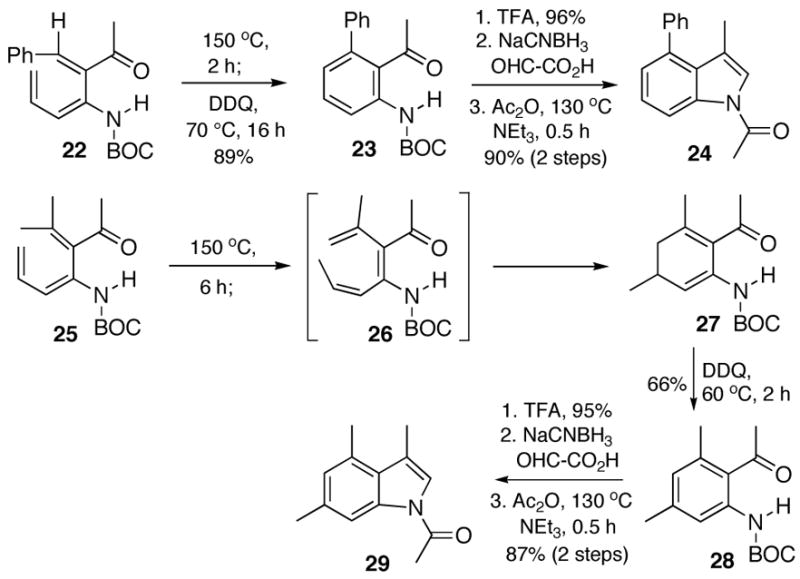

In addition to cyclic α-iodoenones, we have also employed acyclic α-iodoenones as the starting materials in the annelation sequence (Scheme 4). For example, the cis-phenyl ring did not diminish the yield (90%) of the Stille coupling reaction leading to trienecarbamate 22. However, the electrocyclization of trienecarbamate 22 required a higher temperature, perhaps due to a more out of plane carbonyl in comparison to the conformationally locked cyclic trienecarbamates (Schemes 1,2,3).

Scheme 4.

Subsequent transformation of 23 to the desired N-acetyl indole 24 was straightforward. Thermolysis of the β, β-disubstituted acyclic enone 25 provided the cyclohexadiene 27. This result was not entirely unexpected since it is well known that [1,7]-sigmatropic rearrangements are often competitive with 6π-electrocyclic closures, in this case providing the rearrangement product 26 followed by electrocyclic closure to 27. Our standard protocol then furnished the 3,4,6-trisubstituted indole 29.

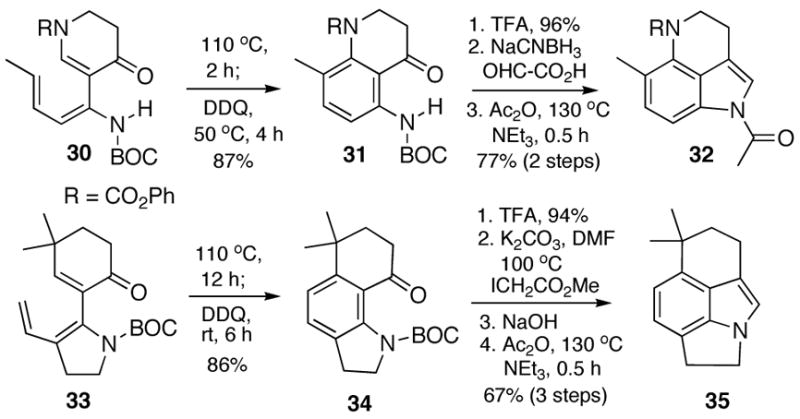

We have also found that additional heterocyclic rings can be incorporated into the product indole by initiating the annelation sequence with heterocyclic α-iodoenones or α-stannylenecarbamates (Scheme 5). Thus, electrocyclization of triene 30 proceeded smoothly with a negligible electronic/steric impact of the additional carbamate substituent to afford a cyclohexadiene that was oxidized (DDQ) in situ to the desired protected aniline 31. Completion of the annelation afforded indole 32, a substructure embodied in several biologically active natural products, e.g., the prianosins.9 Finally, the modularity of this indole construction method is showcased in the preparation of the unusual tetracyclic indole 35 which originates from 4,4-dimethyl-2-iodocyclohexenone and the BOC protected 3-vinyl-2-(trimethylstannyl)pyrroline.

Scheme 5.

In conclusion, we have shown that both of the aromatic rings of indoles can be constructed from readily available α-haloenones and α-(trialkylstannyl)enecarbamates using a 5-step reaction sequence that features facile electrocyclic ring closures of trienecarbamates. The method may prove to be most useful for the preparation of indoles possessing complex or difficult substitution patterns. The syntheses of natural products of this type are underway.

Supplementary Material

Spectroscopic data and experimental details for the preparation of all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the financial support provided by the National Institutes of Health (GM28553).

References

- 1.Horton DA, Bourne GT, Smythe ML. Chem Rev. 2003;103:893. doi: 10.1021/cr020033s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Sundberg RJ. Indoles. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 1996. [Google Scholar]; (b) Gribble GW. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans I. 2000:1045. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dunetz JR, Danheiser RL. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:5776. doi: 10.1021/ja051180l. and reference 2 therein. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.α-(Tributylstannyl)enecarbamate 1 was prepared in three steps from the Overman diene ( Overman LE, Taylor GF, Petty CB, Jessup PJ. J Org Chem. 1978;43:2164.(a) Protection with SEMCl, (b) metallation and stannylation with Bu3SnCl, and (c) deprotection of the SEM group. See supporting information for experimental procedures and spectral data.

- 5.Okamura WH, De Lera AR. In: Comprehensive Organic Synthesis. Trost BM, Fleming I, Paquette LA, editors. Vol. 5. Pergamon Press; New York: 1991. p. 699.(b) For significantly slower (>200 °C) electrocyclic ring closures of 2,3-divinylpyrroles, see: Moskal J, van Stralen R, Postma D, van Leusen AM. Tetrahedron Lett. 1986;27:2173.

- 6.For a more pronounced acceleration of the electrocyclic closure of a related triene by this effect, see: Magomedov NA, Ruggiero PL, Tang Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:1624. doi: 10.1021/ja0399066.

- 7.Nonetheless, this relatively facile electrocyclic ring closure indicates that an electron-donating substituent at C(3) of the triene is beneficial as has been previously suggested, see: Spangler CW, Jondahl TP, Spangler B. J Org Chem. 1973;38:2478.For the closure of a C(2) aminotriene, see: Barluenga J, Merino I, Palacios F. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990;31:6713.For calculations of substituent effects, see: Guner VA, Houk KN, Davies IA. J Org Chem. 2004;69:8024. doi: 10.1021/jo048540s. and references cited therein.

- 8.Tighineanu E, Chiraleu F, Råileanu D. Tetrahedron. 1980;36:1385.For related ring closures leading to pyrroles, see: Gabbutt CD, Hepworth JD, Heron BM, Pugh SL. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 1. 2002:2799.For the generation of a similar münchnone under these conditions, see: Padwa A, Gingrich HL, Lim R. J Org Chem. 1982;47:2447.

- 9.Cheng J, Ohizumi Y, Wälchli MR, Hideshi N, Hirata Y, Sasaki T, Kobayashi J. J Org Chem. 1988;53:4621. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Spectroscopic data and experimental details for the preparation of all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.