Abstract

Substantial evidence indicates that the experience of both clinical and experimental pain differs among ethnic groups. Specifically, African Americans generally report higher levels of clinical pain and greater sensitivity to experimentally induced pain; however, little research has examined the origins of these differences. Differences in central pain-inhibitory mechanisms may contribute to this disparity. Diffuse noxious inhibitory controls (DNIC), or counterirritation, is a phenomenon thought to reflect descending inhibition of pain signals. The current study assessed DNIC in 57 healthy young adults from two different ethnic groups: African Americans and non-Hispanic whites. Repeated assessments of the nociceptive flexion reflex (NFR) as well as ratings of electrical pain were obtained prior to, during and after an ischemic arm pain procedure (as well as a sham procedure). The DNIC condition (i.e. ischemic arm pain) produced substantial reductions in pain ratings as well as electrophysiologic measures of the NFR for all participants when compared with the sham condition (p < .001). The DNIC condition produced significantly greater reductions in verbal pain ratings among non-Hispanic whites when compared with African Americans (p = .02), while ethnic groups showed comparable reductions in NFR. The findings of this study suggest differences in endogenous pain inhibition between African Americans and non-Hispanic whites and that additional research to determine the mechanisms underlying these effects is warranted.

Perspective

This study adds to a growing literature examining ethnic differences in experimental pain perception. Our data suggest that these variations may be influenced by differences in descending inhibition.

Keywords: Experimental Pain, Diffuse Noxious Inhibitory Controls, DNIC, Nociceptive Flexion Reflex, NFR: Ethnic Differences

Introduction

Understanding the relationship between race, ethnicity and pain is a topic of growing interest and importance. The term “race” distinguishes major groups of people according to a supposed biological disposition, it is focused on ancestry and a combination of physical characteristics, while “ethnicity” encompasses culture, history, experience, ancestry, and beliefs as well as biology and physical characteristics (see Edwards et al., 200112 for review). In recent years considerable evidence has shown that both clinical and experimental pain responses vary across ethnic groups, with African Americans (AA) generally demonstrating increased clinical pain and greater sensitivity to experimentally-induced pain when compared to non-Hispanic whites21. In a variety of clinical conditions, African Americans report higher levels of pain and disability13,39, greater pain unpleasantness, and more pain-related emotional distress relative to non-Hispanic whites21,39. Laboratory studies have shown AA to have lower heat pain thresholds and tolerances6,44, and higher ratings of heat pain unpleasantness14, as well as lower cold pressor pain tolerances50 when compared to non-Hispanic whites. Additionally, AA reported greater intensity and unpleasantness in response to a modified ischemic task relative to non-Hispanic whites, using a standardized rating scale5. Therefore, ethnic differences in both clinical and experimental pain have been widely reported, with the most robust differences in experimental pain found for suprathreshold measures3,36.

Differences in central pain-inhibitory mechanisms could potentially contribute to the differences in pain reports by African American and non-Hispanic white individuals; however, standard laboratory pain measures do not directly assess pain inhibitory mechanisms. DNIC, or counterirritation, refers to the process whereby one noxious stimulus inhibits the perception of a second painful stimulus and is thought to reflect descending inhibition of pain signals26,35. DNIC is presumed to operate through activation of descending supraspinal inhibitory pathways initiated by release of endogenous opioids8,24,27,41.

DNIC has been examined extensively in non-human animals, with early studies focused on the mechanisms involved in the process of DNIC; however, more recent studies in humans have utilized DNIC to examine possible deficiencies in descending inhibitory processes in certain populations. For example, sex differences45, and age differences15 have been observed in DNIC, suggesting differing endogenous pain inhibition across certain groups. The clinical relevance of DNIC has previously been demonstrated17,23,55. Clinical pain conditions such as fibromyalgia22,25,46, osteoarthritis23, trapezius myalgia29, rheumatoid arthritis30, and peripheral nerve injury2 also show evidence of impaired DNIC responses; suggesting a possible role for dysregulation of pain inhibitory systems in the acquisition or maintenance of the condition47. Interestingly, recent research suggests it may identify patients at risk for developing post-operative pain55.

This study was designed to further elucidate the nature of ethnic differences in pain perception by investigating responses to DNIC using the nociceptive flexion reflex (NFR); an electrophysiological procedure based on the measurement of stimulus-induced spinal reflexes51. This methodology permits assessment of both self-reported pain and quantification of an individual’s electrophysiological response.

Materials and Methods

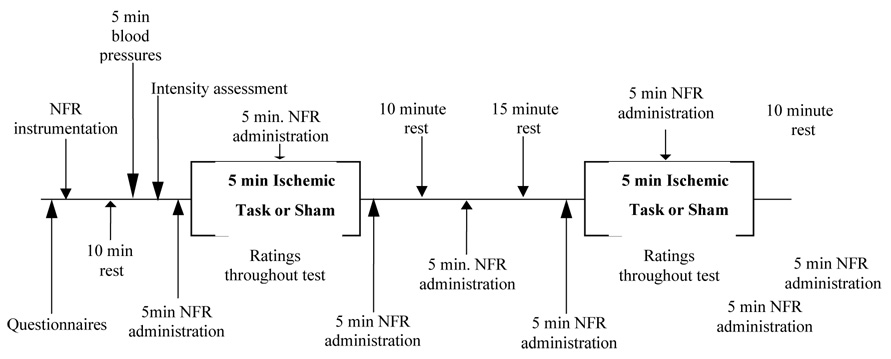

A total of 57 healthy young adults (29 African American 51.7% female, 28 non-Hispanic white, 57.7% female) were recruited through flyers dispersed throughout a large Southeastern university community. Stringent inclusion criteria assured that all individuals were in good health, had no prior history of pain problems or psychiatric disorders. Participants completed two experimental sessions, each lasting up to 2 hours. Upon arrival for the first session, verbal and written informed consent was obtained. Participants were then instrumented (see procedure below), and rested for 10 minutes, after which their blood pressure was measured for five minutes using an automated blood pressure cuff. Next, their baseline NFR threshold was determined as described below. During the second session, an additional evaluation and tailoring of electrical stimulation was performed as well as one DNIC assessment and one sham DNIC (S-DNIC) assessment, conducted in randomized order (see Figure 1 for timeline). All study procedures were approved by the University of Florida Institutional Review Board.

Figure 1.

Timeline for Session 2

TESTING PROCEDURES

Nociceptive Flexion Reflex Assessment

All stimulating and recording sites were cleaned and gently abraded to achieve an impedance of less than 10,000 Ohms prior to electrode placement. Electrical stimulation was delivered via a Nicolet bar electrode applied to the left sural nerve, using a Digitimer, DS7A constant-current stimulator (Herfordshire, UK). The nociceptive withdrawal reflex was assessed using two electrodes, one placed over the left biceps femoris muscle, the other placed over the reference site, the left lateral epicondyle of the femur with a DelSys, Bagnoli-2 differential amplifier. EMG was recorded and processed using a CED Micro1401 analog-to-digital converter and Spike2 software. Participants were seated in a reclining chair in order to maintain a 60-degree angle of the left knee. The nociceptive flexion reflex was operationally defined according to Rhudy and France37 as a mean rectified EMG response in the 90–150 ms post-stimulus interval that exceeded mean rectified EMG activity during a 60 ms pre-stimulus baseline interval (–65 to –5 ms) by at least 1.5 SD. This criterion was used both throughout NFR threshold assessment (conducted during the first session only and reported elsewhere4) and in use of the NFR as a test stimulus for DNIC assessment. Participants rated the perceived intensity of each pulse using a 0 to 100 rating scale (0=no sensation and 100=strongest imaginable sensation of any kind). This intensity scale, which uses general sensory anchors rather than pain-specific anchors, was selected for two primary reasons. First, it allows ratings of both painful and nonpainful electrical stimuli. Second, it has been argued that between subject and between group comparisons may be more valid when using general labeled scales such as this one1,10. We have previously found that a rating of approximately 30 on this scale corresponds to the pain threshold (unpublished data).

Test Stimulus

At the start of the second session, an electrical stimulation analysis was conducted in order to identify the intensity at which participants rated electrically induced pain as a “45” on a 0–100 scale, chosen in order to yield a customized, moderately intense, tailored stimulus level. Electrical stimulation began at the intensity of the participant’s nociceptive flexion reflex threshold, then increased until a rating of 50 was obtained, following which stimulation was reduced by 2 mA until a rating of 30 was reached. In order to identify an electrical stimulus that produced moderate pain, the stimulation intensity at a rating of 45 was calculated for each participant and used in all subsequent testing; consisting of several five minute blocks of electrical stimulation described in Figure 1. Participants rated each stimulus (one per minute) on the 0 – 100 scale; these ratings were averaged over each five minute block of stimulation. This yielded four separate ratings of the electrical stimulus for each condition: a baseline rating, a rating during the conditioning (or sham) stimulus ,a rating 5 minutes after the conditioning (or sham) stimulus (post 1 rating), and a rating 15 minutes after the conditioning (or sham) stimulus (post 2 rating).

Conditioning Stimulus

Ischemic pain was induced using a modified submaximal effort tourniquet procedure31,32,33, as this has been shown to increase participant safety, has a brief exposure time and reduces participant attrition18. Following five minutes of baseline NFR testing, the 10 cm wide straight segmental blood pressure cuff (model SC-10) was applied to the participant’s right arm. They completed 2 minutes of handgrip exercises, after which time their arm was elevated for 30-seconds. The arm was then occluded by inflating the blood pressure cuff to a pressure of 240 mm Hg (or not in the sham procedure) using a Hokanson cuff inflator and air source (Bellevue, WA). Five minutes of ischemic arm pain was conducted with concurrent NFR administration. At 30-second intervals, participants rated the intensity of their arm pain on a 0 to 20 validated box scale, which includes verbal descriptors between neutral and extremely intense 7. After five minutes of arm occlusion (or the sham procedure), the cuff was deflated and NFR assessment continued for an additional 5 minutes (post 1). After a ten minute break, an additional five minutes of NFR was repeated (post 2).

An identical sequence occurred during the sham assessment. Specifically, five minutes of baseline NFR testing was observed, then 2 minutes of handgrip exercises were completed (the blood pressure cuff was applied to the arm, the machine was on and the participant’s arm raised for 30 seconds; however, the cuff was not inflated). Five minutes of NFR testing occurred while the ischemic cuff was loosely wrapped around the participant’s arm. The post 1 and post 2 assessments for sham were conducted as described above. These conditions were randomized and a 15 minute break was observed between each condition.

Cardiovascular Assessment

After participants were instrumented, seated and positioned, a ten minute rest period was observed, after which five minutes of baseline blood pressure readings (systolic, diastolic, mean arterial pressure and heart rate) were measured with a Dinamap (Critikon, Tampa, FL) blood pressure cuff applied to the left arm. Cardiovascular measures were also assessed once per minute for five minutes during the DNIC and S-DNIC segments.

Attention Questions

Participants were asked to rate their level of attention focused on the arm and also asked to rate their attention toward their ankle on a 0 – 100 scale (where 0 = no attention and 100 = complete attention), as well as the degree to which the sensation in their ankle differed due to the cuff on a −100 – 0 – 100 scale (where −100 = complete reduction in ankle pain, 0 = no difference and 100 = complete increase in ankle pain) immediately after the DNIC and S-DNIC portions of testing, prior to the post 1 NFR assessments.

Data Reduction and Analysis

To examine differences in reflex activity during DNIC, the total number of reflexes occurring during the five minute pre-DNIC (or sham) and DNIC (or sham) assessment periods was computed. A difference score (total number of pre-DNIC reflexes minus during DNIC reflexes) was calculated for each subject. A 2 (group) X 2 (condition: DNIC vs. sham) mixed model ANOVA was then conducted to determine the reliability of differences in DNIC between ethnic groups, using the change score as the dependent variable. Analysis of electrical pain ratings was conducted in a similar fashion. Specifically, the average electrical pain rating was computed for each time period (pre-DNIC or pre-sham, during DNIC or during sham), and these change scores were used as dependent measures in mixed model ANOVAs, as described for reflex activity.

The time course of post-DNIC effects was examined by averaging reflexes and ratings separately for the two post-DNIC periods (i.e. 5-minutes post-DNIC and 15-minutes post-DNIC). Mixed model ANOVAs were conducted in order to characterize the after effects of DNIC as described above for the DNIC analyses. Mixed model ANOVAs were used to examine cardiovascular responses across experimental conditions and ethnic groups. Correlational analyses were conducted to examine associations between attentional variables and the magnitude of DNIC, including DNIC change scores for both reflex measures and pain ratings.

Results

Demographic data for each ethnic group are presented in Table 1; there were no significant differences in age, sex, BMI, or baseline cardiovascular measures. As previously reported in this cohort4, African Americans (M = 14.99 mA, SD = 8.98) demonstrated an NFR reflex threshold at a lower stimulus intensity relative to non-Hispanic whites (M = 20.95 mA, SD=10.45).

Table 1.

Demographic information, means (SD) for pre-testing and cardiovascular measures by ethnicity

| Variable | AA (n=29) | Whites (n=28) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (SD) | 23.7 (7.1) | 25.3 (8.6) |

| Sex (% female) | 51.7 | 57.7 |

| BMI (SD) | 23.66 (5.19) | 23.34 (3.36) |

| BL Systolic Blood Pressure | 108.3 (10.1) | 108.7 (8.4) |

| BL Diastolic Blood Pressure | 62.1 (7.6) | 61.2 (6.9) |

| BL Heart Rate | 67.3 (11.3) | 64.6 (9.4) |

| DNIC Systolic Blood Pressure | 112.5 (11.6) | 114.0 (9.7) |

| DNIC Diastolic Blood Pressure | 67.2 (8.7) | 66.9 (7.5) |

| DNIC Heart Rate | 67.2 (11.1) | 65.1 (10.1) |

| S-DNIC Systolic Blood Pressure | 110.0 (9.1) | 110.5 (8.1) |

| S-DNIC Diastolic Blood Pressure | 64.3 (8.9) | 63.9 (7.8) |

| S-DNIC Heart Rate | 66.8 (9.7) | 64.7 (8.7) |

DNIC Findings

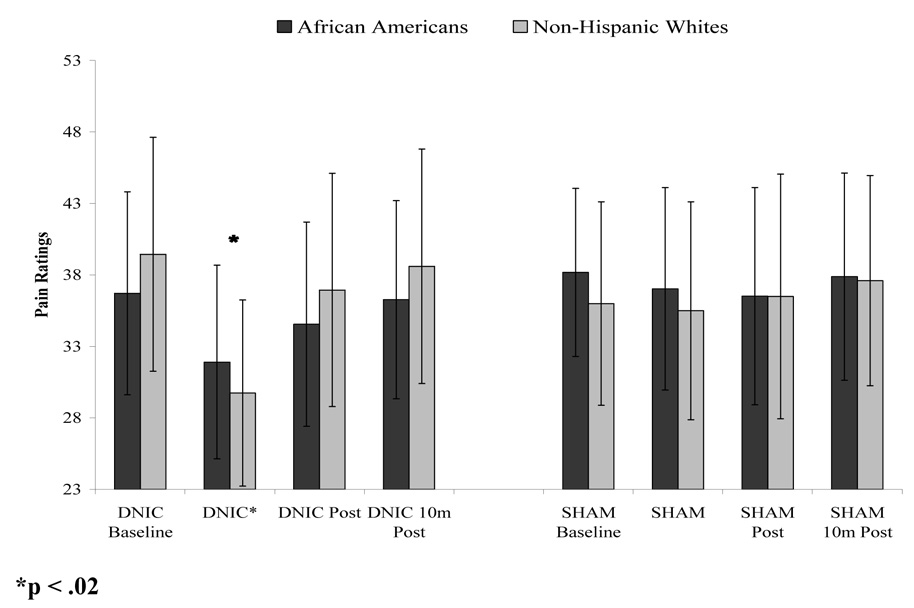

For the electrical stimulus, the intensity at which participants reported moderate pain, identified by a rating of 45, differed significantly by ethnic group (F (1,54)=5.77, p < .05); therefore, African Americans (M = 18.6 mA, SD = .96) received significantly lower levels of electrical stimulation during the DNIC procedures compared to non-Hispanic whites (M = 24.6 mA, SD = .92). A main effect of DNIC condition (i.e. DNIC vs. S-DNIC) on ratings of electrical pain emerged, indicating that the conditioning stimulus produced significant reductions in pain ratings for both ethnic groups during the DNIC condition when compared with the S-DNIC condition (F (1,54)=8.56, p < .005). However, there was also a significant ethnic group X DNIC condition interaction, such that the DNIC condition produced significantly greater reductions in pain ratings among non-Hispanic whites when compared with African Americans (F (1,54)=4.03, p = .02), while no group differences were found for DNIC-S. These data are presented graphically in Figure 2. The ethnic difference in DNIC remains significant even after controlling for sex and the difference in stimulus intensity (p < .012). While the pre-DNIC ratings did not significantly differ by group, they were slightly higher in the non-Hispanic white group and were somewhat lower during the DNIC period. ANCOVA revealed that during DNIC pain ratings differed significantly by groups (p = 0.018) after controlling for pre-DNIC pain ratings.

Figure 2.

DNIC and S-DNIC electrical pain stimuli ratings averaged across each testing segment.

A main effect of DNIC condition also emerged for the number of reflexes observed over the 5 minute conditioning period, with a significantly lower number of reflexes during DNIC versus S-DNIC stimulation (F (1,42) = 8.35, p < .01). No main effect of ethnic group or interaction was found for the number of EMG reflexes (ps > .10). ANOVAs revealed no group differences in ratings of ischemic pain during the DNIC condition. Analysis of variance was conducted in order to characterize the after effects of DNIC and the possible influence of ethnicity. No significant differences were observed at the post DNIC and S-DNIC measurements, with both African Americans and non-Hispanic whites returning to baseline pain ratings and baseline reflex activity during the 5-minute period following DNIC stimulation.

Cardiovascular responses were evaluated to examine changes in blood pressure and heart rate reactivity during DNIC and S-DNIC. No significant group or condition effects emerged for any of the cardiovascular responses. These data are presented in Table 1. Change scores were computed for each cardiovascular measure by subtracting the baseline value from the response during DNIC. These change scores were then correlated with the DNIC differences scores for pain ratings and reflex activity. None of these correlations were significant (all ps > .05).

Ratings of attention focused on the arm, ankle and the degree to which the sensation in their ankle differed due to the cuff did not differ by group. These ratings were not correlated with magnitude of DNIC among African Americans; however, among non-Hispanic whites, increased attention to the arm predicted greater reductions in electrical pain during DNIC (r=0.46, p < .05). In order to determine whether attention to the arm accounted for the ethnic group difference in DNIC-induced reduction in electrical pain, these data were re-analyzed with an ANCOVA using attention ratings as the covariate. Ethnic group differences in DNIC remained significant even when controlling for subjects ratings of attention to the arm along with the electrical stimulation intensity (p < .05).

Discussion

The findings of this study indicate that concurrent ischemic pain produced significant reductions in the number of EMG reflexes in both groups, and the magnitude of this effect was similar across groups. However, ischemic pain produced greater reductions in electrical pain ratings among non-Hispanic whites compared to African Americans. This suggests that for self reported pain, African Americans experienced reduced DNIC relative to non-Hispanic whites, which implies differences in endogenous pain inhibition between African Americans and non-Hispanic whites. This may be one factor contributing to observed ethnic differences in clinical and experimental pain responses. DNIC is thought to reflect influences of complex descending inhibitory systems, potentially mediated by endogenous opioids. However, opioid antagonism reverses DNIC in some53 but not all16,28 human studies, suggesting that nonopioid mechanisms may underlie some forms of DNIC.

Other physiological processes that may contribute to ethnic group differences in endogenous pain modulation have received scant attention. A recent study34 examined regulatory mechanisms involving stress-induced increases in blood pressure, norepinephrine, and cortisol functioning on pain response in African Americans and a primarily non-Hispanic white group (Caucasian/Other), and found these physiological changes to be more strongly associated with reduction of pain responses among Caucasian/Other participants. While our results are generally consistent with Mechlin in observations of more effective endogenous pain inhibition among non-Hispanic whites, cardiovascular reactivity was not associated with the magnitude of DNIC in either ethnic group in the current study. This may be due to the low level of cardiovascular reactivity observed during the tourniquet in our study. This low level of reactivity is likely due to the fact that we assessed cardiovascular responses to DNIC and DNIC-S after the handgrip exercise had been completed, and the most robust cardiovascular response to the ischemic procedure occurs during the handgrip exercise31.

The effects of DNIC are thought to be intensity-dependent and long-lasting when a conditioning stimulus is applied to heterotopic areas of the body9,26,49. In humans, heterotopic noxious stimuli inhibit the spinal nociceptive flexion reflex (NFR), which is controlled by spinal transmission of nociceptive signals52,54. In our sample, while the conditioning stimulus reduced the frequency of NFR reflexes for the group as a whole, no ethnic differences in reduction of reflexes were evident. It remains unclear why the conditioning stimulus reduced ratings to a greater extent in non-Hispanic whites, while EMG activity did not differ between groups. While the NFR threshold differed in electrical intensity level between the two groups, it is possible that the ratings of supra-threshold electrical pulses used as the test stimulus may reflect the more affective-motivational aspect of pain perception as has previously been suggested14,39,44. Moreover, that ethnic group differences in pain inhibition were reflected in reduced pain ratings but not in reflex responses may indicate that ethnic group differences in pain modulation are not related to descending inhibition of spinal nociceptive transmission. Rather, perhaps ethnic group differences can be attributed to higher cortical mechanisms of pain inhibition38. Additionally, the effects of DNIC in this study were relatively brief, as pain ratings and NFR frequency returned to baseline immediately after the cessation of the conditioning stimulus.

One potential explanation of the DNIC response is that the conditioning stimulus serves as a distraction from the test stimulus. One of the most common counterarguments is that the analgesic effects of DNIC outlast the conditioning stimulus by several minutes and up to several days28,53. However, this was not the case in our study, as electrical pain responses returned to baseline immediately after the conditioning stimulus. Thus, distraction may have contributed to DNIC in our study. Consistent with this, ratings of distraction by the conditioning stimulus predicted greater DNIC-induced reductions in electrical pain ratings (but not reductions in NFR frequency), but only among non-Hispanic whites. However, the ethnic group difference in DNIC remained significant after controlling for distraction ratings. Thus, distraction may have contributed to the DNIC effect on electrical pain ratings, but does not appear to account for the ethnic group difference in DNIC.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of the present study. First, all of the tasks were acute painful laboratory experiences over which the participants had control; therefore, these results may be less generalizable to a clinical pain population. However, the clinical relevance of DNIC has previously been demonstrated by multiple investigators17,23,55. Another possible limitation may result from our decision to tailor the test stimulus based on participants’ verbal pain ratings. Most studies examining DNIC using the NFR use 120% of an individual’s NFR threshold; however, in our sample this would have caused great differences in individual’s pain ratings of the stimuli. Due to the wide variability in NFR threshold between African Americans and non-Hispanic whites, a stimulus tailored based on ratings of perceived intensity was used. Adapting stimulus intensity to perceptual levels has been used in other DNIC studies20,48 and has the distinct advantage of reducing floor and ceiling effects19, thus making it quite appropriate for use in examination of pain responses when wide individual differences may be observed. Additionally, the tailored stimulus intensity was between approximately 117 – 124% of NFR thresholds, suggesting that the two groups did not receive drastically different levels of stimulation relative to their NFR thresholds. Further, when intensity level was used as a covariate, our findings remained significant. Nevertheless, our choice to tailor the test stimulus based on perceived intensity may have contributed to our observation of ethnic differences in DNIC being reflected in reduced pain ratings but not in reflex responses. Additionally, a potential limitation may include the scale used to assess pain perception of the test stimulus. This scale excludes conventional anchors (i.e. no pain, worst pain imaginable) which may vary as a result of individual differences in their use5,40. However, cross-modality matching techniques have shown that pain assessments using scales anchored by “most intense sensation of any kind” as opposed to “most intense pain” specifically, are thought to reduce variability between groups11. While the scale does not mention pain per se, several studies have shown that a close relationship exists between the NFR reflex threshold and pain threshold42. As we used a stimulation intensity greater then the NFR reflex threshold level we believe these ratings correspond to an individual’s pain level. Moreover, our only data directly relating this scale to the pain threshold are as yet unpublished, which is a limitation. Another limitation may be the possibility of habituation with frequent use of the NFR stimuli, one per minute; however, previous results show habituation to be highly dependent on the interstimulus interval, and observed habituation with stimulation every 5 seconds, but no habituation with stimulation 25 seconds apart43.

These limitations notwithstanding, our findings provide evidence of ethnic group differences in endogenous pain modulation as measured by DNIC. The current findings provide further evidence for the existence of ethnic differences in pain processing. Though this type of endogenous pain modulation has received extensive attention in recent years and considerable evidence has amassed for its experimental utility, the current findings of ethnic differences in DNIC does not necessarily explain clinical or experimental differences observed in pain perception. Future studies should focus on the clinical relevance and implications for care, such as studying ethnic differences in DNIC in clinical pain models. Future studies may also pursue a better understanding of the mechanisms involved in ethnic differences in DNIC by using opioid blockade, in order to characterize the extent to which endogenous opioids are mediating ethnic differences.

Acknowledgements

This material is the result of work supported by NIH/NINDS grant NS42754, General Clinical Research Center Grant RR00082 and T32 MH75884.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bartoshuk LM. Psychophysics: a journey from the laboratory to the clinic. Appetite. 2004;43:15–18. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bouhassira D, Danziger N, Attal N, Guirimand F. Comparison of the pain suppressive effects of clinical and experimental painful conditioning stimuli. Brain. 2003;126:1068–1078. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell CM, Edwards RR, Fillingim RB. Ethnic differences in responses to multiple experimental pain stimuli. Pain. 2005;113:20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell CM, France CR, Robinson ME, Logan HL, Geffken GR, Fillingim RB. Ethnic differences in the nociceptive flexion reflex (NFR) Pain. 2008 May 3;134:91–96. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell TS, Hughes JW, Girdler SS, Maixner W, Sherwood A. Relationship of ethnicity, gender, and ambulatory blood pressure to pain sensitivity: Effects of individualized pain rating scales. J.Pain. 2004;5:183–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.02.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chapman WP, Jones CM. Variations in cutaneous and visceral pain sensitivity in normal subjects. J.Clin.Invest. 1944;23:81–91. doi: 10.1172/JCI101475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coghill RC, Gracely RH. Validation of combined numerical-analog descriptor scales for rating pain intensity and pain unpleasantness. Proc Amer Pain Soc. 1996;15:86. [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Broucker T, Cesaro P, Willer JC, Le Bars D. Diffuse noxious inhibitory controls in man. Involvement of the spinoreticular tract. Brain. 1990;113:1223–1234. doi: 10.1093/brain/113.4.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dickenson AH, Le Bars D. Diffuse noxious inhibitory controls (DNIC) involve trigeminothalamic and spinothalamic neurones in the rat. Exp.Brain Res. 1983;49:174–180. doi: 10.1007/BF00238577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dionne RA, Bartoshuk L, Mogil J, Witter J. Individual responder analyses for pain: does one pain scale fit all? Trends Pharmacol.Sci. 2005;26:125–130. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dionne RA, Bartoshuk L, Mogil J, Witter J. Individual responder analyses for pain: does one pain scale fit all? Trends Pharmacol.Sci. 2005;26:125–130. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edwards CL, Fillingim RB, Keefe FJ. Race, ethnicity and pain: a review. Pain. 2001;94:133–137. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00408-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edwards RR, Doleys DM, Fillingim RB, Lowery D. Ethnic differences in pain tolerance: clinical implications in a chronic pain population. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2001;63:316–323. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200103000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edwards RR, Fillingim RB. Ethnic differences in thermal pain responses. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1999;61:346–354. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199905000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edwards RR, Fillingim RB, Ness TJ. Age-related differences in endogenous pain modulation: a comparison of diffuse noxious inhibitory controls in healthy older and younger adults. Pain. 2003;101:155–165. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00324-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edwards RR, Ness TJ, Fillingim RB. Endogenous opioids, blood pressure, and diffuse noxious inhibitory controls: a preliminary study. Percept.Mot.Skills. 2004;99:679–687. doi: 10.2466/pms.99.2.679-687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edwards RR, Ness TJ, Weigent DA, Fillingim RB. Individual differences in diffuse noxious inhibitory controls (DNIC): association with clinical variables. Pain. 2003;106:427–437. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.France CR, Suchowiecki S. A comparison of diffuse noxious inhibitory controls in men and women. Pain. 1999;81:77–84. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(98)00272-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Granot M, Granovsky Y, Sprecher E, Nir RR, Yarnitsky D. Contact heat-evoked temporal summation: tonic versus repetitive-phasic stimulation. Pain. 2006;122:295–305. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Granot M, Weissman-Fogel I, Crispel Y, Pud D, Granovsky Y, Sprecher E, Yarnitsky D. Determinants of endogenous analgesia magnitude in a diffuse noxious inhibitory control (DNIC) paradigm: Do conditioning stimulus painfulness, gender and personality variables matter? Pain. 2007 Aug 27; doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Green CR, Anderson KO, Baker TA, Campbell LC, Decker S, Fillingim RB, Kaloukalani DA, Lasch KE, Myers C, Tait RC, Todd KH, Vallerand AH. The unequal burden of pain: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in pain. Pain Med. 2003;4:277–294. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4637.2003.03034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kosek E, Hansson P. Modulatory influence on somatosensory perception from vibration and heterotopic noxious conditioning stimulation (HNCS) in fibromyalgia patients and healthy subjects. Pain. 1997;70:41–51. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(96)03295-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kosek E, Ordeberg G. Lack of pressure pain modulation by heterotopic noxious conditioning stimulation in patients with painful osteoarthritis before, but not following, surgical pain relief. Pain. 2000;88:69–78. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00310-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kraus E, Le Bars D, Besson JM. Behavioral confirmation of "diffuse noxious inhibitory controls" (DNIC) and evidence for a role of endogenous opiates. Brain Research. 1981 Feb 16;206:495–499. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(81)90554-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lautenbacher S, Rollman GB. Possible deficiencies of pain modulation in fibromyalgia. Clinical.Journal.of.Pain. 1997;13:189–196. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199709000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Le Bars D, Dickenson AH, Besson JM. Diffuse noxious inhibitory controls (DNIC). I. Effects on dorsal horn convergent neurones in the rat. Pain. 1979;6:283–304. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(79)90049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Le Bars D, Dickenson AH, Besson JM. Diffuse noxious inhibitory controls (DNIC). II. Lack of effect on non-convergent neurones, supraspinal involvement and theoretical implications. Pain. 1979;6:305–327. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(79)90050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Le Bars D, Villanueva L, Bouhassira D, Willer JC. Diffuse noxious inhibitory controls (DNIC) in animals and in man. Patol.Fiziol.Eksp.Ter. 1992;55–65:65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leffler AS, Hansson P, Kosek E. Somatosensory perception in a remote pain-free area and function of diffuse noxious inhibitory controls (DNIC) in patients suffering from long-term trapezius myalgia. Eur.J Pain. 2002;6:149–159. doi: 10.1053/eujp.2001.0312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leffler AS, Kosek E, Lerndal T, Nordmark B, Hansson P. Somatosensory perception and function of diffuse noxious inhibitory controls (DNIC) in patients suffering from rheumatoid arthritis. Eur.J Pain. 2002;6:161–176. doi: 10.1053/eujp.2001.0313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maixner W, Humphrey C. Gender differences in pain and cardiovascular responses to forearm ischemia. Clinical Journal of Pain. 1993;8:16–25. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199303000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maurset A, Skoglund LA, Hustveit O, Klepstad P, Oye I. A new version of the ischemic tourniquet pain test. Methods Find.Exp.Clin.Pharmacol. 1991;13:643–647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maurset A, Skoglund LA, Hustveit O, Oye I. Comparison of ketamine and pethidine in experimental and postoperative pain. Pain. 1989;36:37–41. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(89)90109-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mechlin MB, Maixner W, Light KC, Fisher JM, Girdler SS. African Americans show alterations in endogenous pain regulatory mechanisms and reduced pain tolerance to experimental pain procedures. Psychosom.Med. 2005;67:948–956. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000188466.14546.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Price DD, McHaffie JG. Effects of heterotopic conditioning stimuli on first and second pain: a psychophysical evaluation in humans [see comments] Pain. 1988;34:245–252. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90119-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rahim-Williams FB, Riley JL, III, Herrera D, Campbell CM, Hastie BA, Fillingim RB. Ethnic identity predicts experimental pain sensitivity in African Americans and Hispanics. Pain. 2007;129:177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rhudy JL, France CR. Defining the nociceptive flexion reflex (NFR) threshold in human participants: a comparison of different scoring criteria. Pain. 2007;128:244–253. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rhudy JL, Maynard LJ, Russell JL. Does in vivo catastrophizing engage descending modulation of spinal nociception? J.Pain. 2007;8:325–333. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Riley JL, Wade JB, Myers CD, Sheffield D, Papas RK, Price DD. Racial/ethnic differences in the experience of chronic pain. Pain. 2002;100:291–298. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00306-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Robinson ME, George SZ, Dannecker EA, Jump RL, Hirsh AT, Gagnon CM, Brown JL. Sex differences in pain anchors revisited: further investigation of "most intense" and common pain events. Eur.J.Pain. 2004;8:299–305. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roby-Brami A, Bussel B, Willer JC, Le Bars D. An electrophysiological investigation into the pain-relieving effects of heterotopic nociceptive stimuli. Brain. 1987;110:1497–1508. doi: 10.1093/brain/110.6.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sandrini G, Serrao M, Rossi P, Romaniello A, Cruccu G, Willer JC. The lower limb flexion reflex in humans. Prog.Neurobiol. 2005;77:353–395. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sandrini G, Serrao M, Rossi P, Romaniello A, Cruccu G, Willer JC. The lower limb flexion reflex in humans. Prog.Neurobiol. 2005;77:353–395. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sheffield D, Biles PL, Orom H, Maixner W, Sheps DS. Race and sex differences in cutaneous pain perception. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2000;62:517–523. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200007000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Staud R, Robinson ME, Vierck CJ, Jr, Price DD. Diffuse noxious inhibitory controls (DNIC) attenuate temporal summation of second pain in normal males but not in normal females or fibromyalgia patients. Pain. 2003;101:167–174. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00325-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Staud R, Robinson ME, Vierck CJ, Jr, Price DD. Diffuse noxious inhibitory controls (DNIC) attenuate temporal summation of second pain in normal males but not in normal females or fibromyalgia patients. Pain. 2003;101:167–174. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00325-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Staud R, Robinson ME, Vierck CJ, Jr, Price DD. Diffuse noxious inhibitory controls (DNIC) attenuate temporal summation of second pain in normal males but not in normal females or fibromyalgia patients. Pain. 2003;101:167–174. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00325-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tuveson B, Leffler AS, Hansson P. Time dependent differences in pain sensitivity during unilateral ischemic pain provocation in healthy volunteers. Eur.J.Pain. 2006;10:225–232. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Villanueva L, Le Bars D. The activation of bulbo-spinal controls by peripheral nociceptive inputs: diffuse noxious inhibitory controls[Review] [96 refs] Biological Research. 1995;28:113–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Walsh NE, Schoenfeld L, Ramamurthy S, Hoffman J. Normative model for cold pressor test. American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1989;68:6–11. doi: 10.1097/00002060-198902000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Willer JC. Comparative study of perceived pain and nociceptive flexion reflex in man. Pain. 1977;3:69–80. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(77)90036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Willer JC, De Broucker T, Le Bars D. Encoding of nociceptive thermal stimuli by diffuse noxious inhibitory controls in humans. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1989;62:1028–1038. doi: 10.1152/jn.1989.62.5.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Willer JC, Le Bars D, De Broucker T. Diffuse noxious inhibitory controls in man: involvement of an opioidergic link. Eur.J Pharmacol. 1990;182:347–355. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(90)90293-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Willer JC, Roby A, Le Bars D. Psychophysical and electrophysiological approaches to the pain-relieving effects of heterotopic nociceptive stimuli. Brain. 1984;107:1095–1112. doi: 10.1093/brain/107.4.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yarnitsky D, Crispel Y, Eisenberg E, Granovsky Y, Ben-Nun A, Sprecher E, Best LA, Granot M. Prediction of chronic post-operative pain: Pre-operative DNIC testing identifies patients at risk. Pain. 2007 Dec 11; doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]