Abstract

Background

Patients with an accessory pathway (AP) have an increased propensity to develop atrial fibrillation (AF), but the mechanism is unknown.

Objective

Identification of crucial risk factors and testing the hypothesis that reflection and/or microreentry of atrial impulses propagating into the AP may trigger AF.

Methods

We evaluated 534 patients successfully treated with radiofrequency-ablation for AP at two University Hospitals. Patients were separated into those having concealed versus manifest AP in terms of their propensity to develop AF. To investigate AF triggering mechanisms, we simulated linear and branched 2-dimensional models of atrium-to-ventricle propagation across a heterogeneous 1 × 6 mm2 AP using human ionic kinetics.

Results

A history of AF was twice as common in patients with manifest AP vs. concealed AP irrespective of AP location. AF was also more likely to occur in older males, and in patients with larger atria. There was no correlation between AF history and AP refractory measures. However, the electrophysiological properties of APs seemed to fulfill the prerequisites for reflection and/or microreentry of atrially initiated impulses. In the linear AP model, repetitive atrial stimulation resulted in progressively larger delay of atrium-to-ventricle propagation across the passive segment. Eventually, sufficient time for repolarization of the atrial segment allowed for reflection of an impulse that activated the entire atrium, and by wavefront-wavetail interaction with a new atrial stimulus AF reentry was initiated. Simulations using the branched model showed that microreentry at the ventricular insertion of the AP could also initiate AF via retrograde atrial activation as a result of unidirectional block at the AP-ventricle junction.

Conclusions

Propensity for AF in patients with an AP is strongly related to preexcitation, larger atria, male gender and older age. Reflection and microreentry at the AP may be important for AF initiation in patients with manifest (preexcited) Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Similar mechanisms may trigger AF also in patients without an AP.

Keywords: Wolff-Parkinson-White, accessory pathway, preexcitation, atrial fibrillation, reflected reentry, reentry, micro-reentry, computer simulation

INTRODUCTION

Patients with Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome have an increased risk of developing atrial fibrillation (AF). However, the proposed mechanisms for this propensity are largely unproven. Evidence that AF susceptibility is related to the accessory pathway (AP) itself is supported by the fact that successful AP ablation substantially reduces the risk for subsequent AF.1,2 Previous observations suggest that preexcitation and the antegrade conduction properties of the AP play some role in AF initiation, but no mechanistic explanation has been provided.1,3 Factors other than the presence of the AP and its properties, such as age, male gender, and preexisting electrophysiological and structural atrial abnormalities, might promote the triggering and sustenance of AF, and could also contribute to its recurrence even after successful AP ablation.1–3 The pathophysiological background to AF in WPW patients is thus complex, and the topic of this report.

As an initial step to shed light on this intriguing issue, we undertook a de-novo combined anatomical, electrophysiological and numerical approach. First, we assessed non-invasive and invasive electrophysiological measures and echocardiographically defined atrial dimensions in relation to the occurrence of AF. The results led us then to focus on concealed (cWPW) versus manifest (mWPW) APs by comparing the history of AF in >500 WPW patients. This comparison pointed to the importance of antegrade (atrio-ventricular) conduction over the AP. Subsequently, the AP properties were compared in 165 patients with mWPW. The conclusion was that antegrade AP conduction per se seemed to be the crucial feature. We then established a mechanistic hypothesis, in which reflection4,5 along a linear AP and/or micro-reentry at a branched AP-ventricle junction promote AF in mWPW patients. We have developed a realistic 2-dimensional (2-D) mathematical model of atrio-ventricular propagation across a heterogeneous AP in which both alternative mechanisms were explored.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

An overview of the patient groups is presented in Figure 1. Clinical data from 534 patients were evaluated in 3 steps. Patients were divided according to AP location: left-sided (n=331), right-sided (n=78), and postero-septal (n=125; mostly right-sided). In addition, they were divided according to the presence (mWPW) or absence (cWPW) of preexcitation on electrocardiogram (ECG) at sinus rhythm and during incremental atrial pacing. Two subgroups provided electrophysiological data in steps 1 and 3. Please, note that the account below is chronological with regard to how this project developed.

Figure 1.

Overview of the studied patients divided after accessory pathway location and the presence (mWPW) or absence (cWPW) of preexcitation on the surface electrocardiogram.

Step 1

Patient characteristics

Consecutive patients (n=57) with a left-sided AP, who were referred to the electrophysiology (EP) laboratory and underwent successful radiofrequency ablation during a two-year period were included. The AF history was not available in two patients. The remaining 55 patients were divided into two groups: Group I consisted of 15 (13 men) who had a history of AF, while Group II consisted of 40 (22 men) without such a history.

Electrophysiological study

The methodology in steps 1 and 3 follows standard procedures, and details are provided in the Online Supplement.

Study protocol

P-wave duration and its dispersion were determined from the average of 3 consecutive cardiac cycles from all 12 standard ECG leads. Inter-atrial (IACT) and right atrial conduction time (RACT = PA interval) were determined during sinus rhythm as the time from the earliest P wave deflection (in any surface lead) to the first deflection of the latest atrial activation in any coronary sinus- and to the atrial deflection in the distal His-Bundle recordings, respectively. Left atrial conduction time (LACT) was calculated as IACT minus RACT. All measurements were made from the same 3 consecutive beats.

Right and left atrial sizes were measured at end-systole by 2-dimensional echocardiography in the apical four-chamber view. The average of the diameters in two planes (X and Y) was assessed for each atrium, as well as the sum of these averages as a measure of the size of both atria.

Step 2

Patients with left- (n=331) and right (n=78) -sided mWPW and cWPW were identified, and categorized on the basis of a history of AF or not. In addition, a two-center database of 125 patients with posteroseptal mWPW studied for a different purpose was included in this analysis (and as a subgroup in step 3).6 A statistical analysis of the relative importance of age, gender, AP location, and mWPW vs. cWPW was performed.

Step 3

Protocol and definitions

Patient preparations and catheter positioning were as described in Step 1; see Online Supplement.

There were ≤ 3 antegrade and ≤ 2 retrograde measures of AP conduction available for the left-sided pathways (n=88); the shortest in each direction was used in the analyses. In addition, antegrade AP characteristics were available from 77 of the 125 patients with manifest posteroseptal WPW.6

Statistical analyses (Steps 1–3)

Patient related data are expressed as mean ± SD and measured data as mean ± SEM. In step 1, multivariate analysis (Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA) was used to analyze variables that could predict the occurrence of AF (i.e. RACT, LACT, IACT, P-wave duration, and atrial size). In step 2, logistic regression was applied in a forward stepwise mode to identify significant predictors of the occurrence of AF. Factors tested were age, gender, pathway location and WPW-pattern. Interactions were tested using the difference in log likelihood between the logistic model with and without the interaction term in question included. The between group comparisons of differences in measurements in step 3 were analyzed by unpaired t-test. Two-sided chi-square test with Yates’ correction or Fisher’s exact test was used for analysis of categorical data. p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Step 4

A mechanistic hypothesis was proposed based on a literature review; see Online Supplement.

Step 5

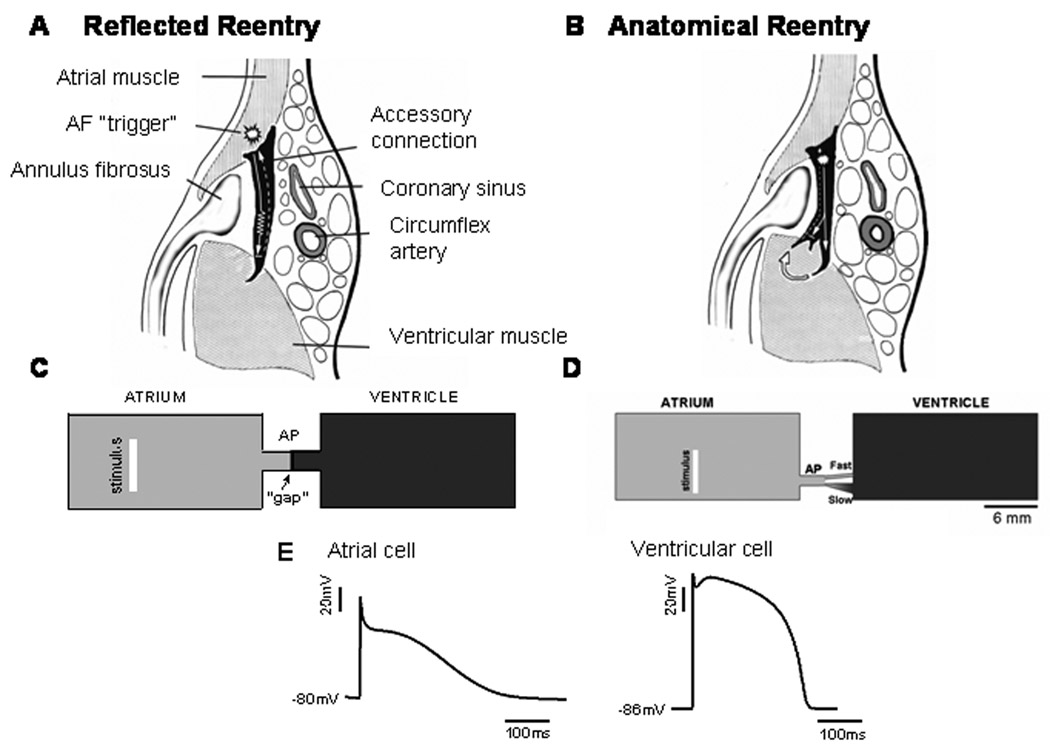

The mechanistic hypothesis for the increased AF propensity in patients with mWPW vs. cWPW was tested using computer simulation. Figure 2 shows schematic representations of two different left-sided APs (black). An AP with single atrial and ventricular epicardial insertions is shown in A, and one with a branched ventricular epicardial insertion is shown in B.

Figure 2.

A. Schematic representation of a left-sided accessory pathway with single atrial and ventricular epicardial insertion and its surroundings, and the mechanistic model of “reflection” or “reflected reentry” within the pathway. B. Schematic representation of a left-sided accessory pathway with single atrial and branched ventricular epicardial insertion and its surroundings. Arrows indicate direction of propagation. C. Two-dimensional computer model of unbranched AP in which the reflected reentry hypothesis was tested. The model consisted of a 2×1 cm2 “atrium”, a 2×1 cm2 “ventricle” and a short 6×2 mm2 accessory pathway (AP). The AP consisted of a 3 mm active atrial segment, an active 2.8 mm ventricular segment, and a 200 µm-long passive element (gap) in between. D. Branched AP with dual pathways used to test for microreentry hypothesis. The dimensions were similar to those in the unbranched AP model with the exception of the presence of the fast and slow pathways. Bottom action potentials recorded from atrial and ventricular segments of the AP. The white vertical bar in the atrium indicates the site of application of atrial stimuli. E. Transmembrane potentials recorded from single model cells in the atrial and ventricular segments.

Computer Model Geometry

1. Reflection Model

Figure 2C illustrates the 2-D anatomical and computer geometry models of an unbranched AP in which the reflected reentry hypothesis was tested. The computer model was constructed with a numeric spatial resolution of 0.1×0.1 mm2; it consisted of a 2×1 cm2 “atrium”, a 2×1 cm2 “ventricle” and a short 6×2 mm2 AP. The AP was further subdivided into a short active atrial segment of length 3 mm (connecting to the atrial side), an active ventricular segment of length 2.8 mm (connecting to the ventricular side) and a 200 µm-long passive element in between.

2. Microreentry Model

A similar 2-D geometry model was implemented for the local micro-reentry model, as illustrated in Figure 2D. In this case, the AP model (composed entirely of atrial cells) was constructed as a 1mm-thick, 2mm-long cable that bifurcated into two branches: a slow conducting and a fast conducting branch. Slow conduction was achieved in two ways: 1. by employing a triangular morphology, which slowed conduction because of gradual decrease in source/sink ratio due to increasing number of downstream cells; 2. by reducing the diffusion coefficient (i.e., electrical coupling) to 1/12 of the nominal value, which essentially reduced conduction velocity by 3.5 and mimicked propagation in the transverse direction of the fibers. The fast branch was constructed of regular atrial cells but was narrow with a constant thickness. Figure 2E shows atrial and ventricular action potentials recorded during pacing at 2.7 Hz in the linear and branched models. See the Online Supplement for details on ionic current kinetics, the equations used in the simulation of electrical propagation and construction of electrograms and for the stimulation protocol.

RESULTS

Step 1 (Table 1)

Table 1.

(Step 1) Characteristics, atrial size and electrophysiologic parameters in study patients with (Group I) and without (Group II) a history of AF, before and after radiofrequency ablation of the accessory pathway.

| Group | I | II | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preexcitation (yes/no) | 10/5 | 13/27 | < 0.05 |

| Age (years) | 45±4 | 37±2 | n.s. |

| Sex (M/F) | 13/2 | 22/18 | < 0.05 |

| Right atrial size (mm) | 43.1±1.3 (10) | 39.1±0.8 (31) | < 0.05 |

| Left atrial size (mm) | 45.1±0.9 (10) | 41.4±0.8 (31) | < 0.05 |

| Both atrial sizes (mm) | 88.1±1.4 (10) | 80.5±1.5 (31) | < 0.01 |

| Before ablation (ms) | |||

| RACT | 37±3 (12) | 36±2 (38) | n.s. |

| LACT | 46±5 (12) | 43±2 (38) | n.s. |

| IACT | 85±6 (13) | 79±3 (39) | n.s. |

| P-wave duration | 137±7 (5) | 133±4 (29) | n.s. |

| P-wave dispersion | 45±8 (5) | 58±4 (29) | n.s. |

| After ablation (ms) | |||

| RACT | 42±4 (11) | 35±2 (34) | n.s. |

| LACT | 41±4 (11) | 43±2 (34) | n.s. |

| IACT | 84±4 (12) | 78±3 (36) | n.s. |

| P-wave duration | 135±3 (14) | 133±2 (38) | n.s. |

| P-wave dispersion | 57±4 (14) | 56±2 (38) | n.s. |

RACT = right atrial conduction time, LACT = left atrial conduction time, IACT = inter atrial conduction time. P < 0.05 denotes significant difference between Group I and II (n.s. = not significant)

Mean age and baseline heart rate were similar in patients with and without an AF history. There were more men in Group I than in Group II (M/F 13/2 vs. 22/18, p<0.05), i.e. 37% of the men and 10% of the women had an AF history. Both right and left atrial sizes were on average 10% larger in Group I patients (p< 0.05 for both comparisons). Preexcitation was significantly more frequent in Group I (67 vs. 32%, p<0.05). However, there were neither any significant difference in intra- or inter-atrial conduction times nor in their heterogeneity. There was a significant correlation between P-wave duration and IACT (after ablation; r=0.60, p<0.01), and, P-wave duration correlated weakly with atrial dimensions (r=0.36, p<0.05).

In summary, male gender, preexcitation (mWPW), and larger atria seemed to predispose for AF.

Step 2

The analysis is summarized in Table 2. Concealed and manifest APs were equally common on the left side, while 85% of the right-sided APs were manifest (Figure 1). In patients with left- and right-sided APs, a history of AF was twice as common in mWPW vs. cWPW. Fifty (30%) of 324 left-sided cases with mWPW had an AF history vs. 24 (15%) with cWPW (p=0.0001). The corresponding numbers for right-sided APs were 24 with AF of 65 (37%) with mWPW vs. 2 of 12 (17%) with cWPW (ns). Taken together, the difference between mWPW and cWPW was highly significant (p = 0.0001).

Table 2.

Comparison of the relative importance of different factors for the occurrence of atrial fibrillation in patients with an accessory pathway (n=526) expressed as odds ratio with 95% confidence interval (CI) within brackets.

| OR | (95% CI) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male gender | 4.72 | (2.85, 7.83) | <0.0001 |

| Manifest WPW | 3.01 | (1.82, 4.96) | <0.0001 |

| Age (per 10 years) | 1.37 | (1.19, 1.57) | <0.0001 |

| Pathway location | n.s. |

Among the 125 patients (70 men) with manifest postero-septal APs, 42 (34%) had documented AF. The mean age (SD) was 35 (15) years for the entire group, without gender related difference, but with a significant difference between patients with and without AF (42±15 vs. 31±14, p=0.0002). Men were more prone to AF than women also in this group (46 vs. 18%, p=0.001).

Step 3

Electrophysiological properties were analyzed in relation to a history of AF in two subgroups from step 2: 85 (of 166, 51%) patients with left-sided mWPW and 77 ( of 125, 62%) with postero-septal mWPW . Results are summarized in the Online Supplement Table 1. Also in this subset, patients with a history of AF were significantly older and more often men, but there was no general gender related difference in age.

The median of the shortest antegrade and retrograde refractory measure of the left-sided pathways was 295 ms for both (mean values 287 and 359 ms, respectively). There was no relation between an AF history and refractory measures below (shorter refractory period) vs. above the median. Furthermore, 3 out 4 (5%) patients with left-sided APs without retrograde conduction had a history of AF. In contrast, the 10 patients with left-sided pathways who had inadvertently induced AF during the ablation procedure, were found among those with shorter antegrade refractoriness than the median vs. those without induced AF (p = 0.0113); there was no relation to retrograde refractoriness or to gender (see Discussion).

Regarding the 77 patients with postero-septal APs and antegrade refractory measures, 23 had while 54 had not a history of AF. Again, there was no relation between an AF history and refractory measures, but there was a relation between AF and both male gender and older age.

Summarizing steps 2 & 3, the pattern was consistent and independent of AP localization with a significantly higher proportion of patients with a history of AF in men vs. women, in mWPW vs. cWPW, and at older vs. younger age; Table 2.

Step 4 See Online Supplement

Step 5 Simulation Results

1. Reflection Model

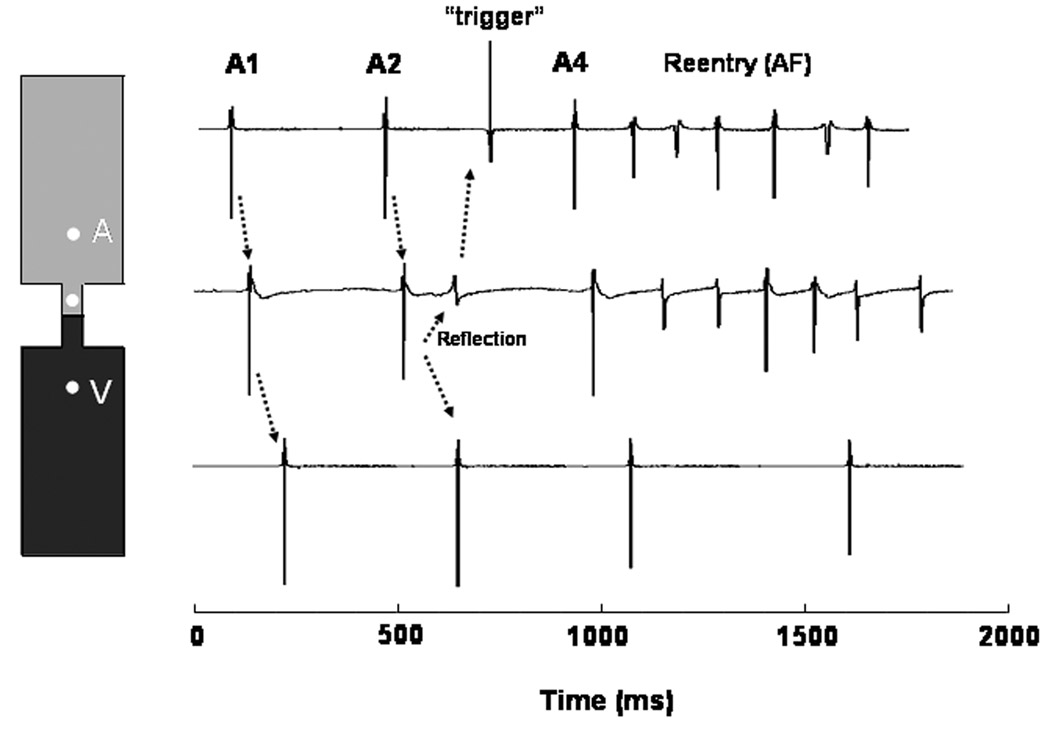

Transmembrane potentials obtained from single cells in the atrial segment, passive element and ventricular segment of the simulated linear AP model are shown in Figure 3A. Electrotonic propagation through the passive element caused delayed ventricular activations. The atrium-to-ventricle delay increased progressively until it was long enough to allow sufficient repolarization of the atrial cells adjacent to the passive element, resulting in a reflected beat that propagated all the way back to the atrium. As demonstrated by the movie presented in the Online Supplement (Movie 1), this retrogradely propagating impulse activated the entire atrium prior to the appearance of a new atrial stimulus (A4) whose wavefront encountered partially recovered atrial tissue with consequent initiation of reentry (AF) that in this case lasted for about 6 full rotations..

Figure 3.

Computer model of reflection and AF initiation induced by and S1S2S3S4 protocol in an unbranched AP. A. Left, diagrammatic representation of the AP with an excitable atrial segment (top), an unexcitable “gap” segment (middle) and a ventricular segment (bottom). Right, transmembrane potentials demonstrate conduction delay, block and electrotonically mediated reflection with retrograde propagation to the atria and initiation of atrial reentry. Two atrial tracings are given at proximal and distal locations to the AP. The proximal tracing (2nd from top) shows an elevated phase 2 resulting from electrotonic influence of the ventricular action potential mediated by the unexcitable gap. B. Time-space plot constructed along the horizontal dashed line in the inset. Green bars show direction and velocity of wavefront propagation. Read areas indicate refractoriness. White vertical bar in inset, stimulus site. A1 and A2 propagated at a constant velocity through the atrial side but became discontinuous upon reaching the gap. The slightly longer delay of A2 allowed for reflection (red arrow), retrograde propagation and initiation of sustained atrial reentry (see online Movie 1).

The time-space plot (TSP) in Figure 3B was constructed along the profile marked by the horizontal dashed line in the inset. As shown by the green bars in the TSP, the A1 and A2 impulses propagated at a constant velocity through the atrium and the proximal segment of the linear AP. However, upon reaching the passive element in the center of the AP, they suffered a discontinuity, reflecting the excessive delay associated with electrotonically-mediated propagation through that element. The slightly longer delay of A2 allowed for reflection (red arrow) and retrograde propagation toward the atrium. Moreover, from this plot it is clear that the interaction between the wave tail of the reflected beat and the wavefront of the subsequent atrial impulse (A4) acted as a trigger for wavebreak and initiation of a figure-of-eight reentry, which activated the atrium at an exceedingly high frequency (~8.2Hz). This in turn resulted in intermittent ventricular activation via the AP yielding a 4:1 AV propagation pattern and a ventricular cycle length of ~2Hz.

Representative bipolar electrograms for the atrium, AP segment and ventricle are shown in Figure 4 to illustrate the manner in which the events leading to AF by this mechanism would manifest in the clinical EP setting. The diagram on the left shows the location of the bipolar electrodes (white balls) and on the right are the electrograms obtained from the atrium AP and ventricle. These recordings show that the A1 impulse would appear to propagate continuously through the linear AP and activate the ventricles without significant delay, despite the presence of the unexcitable element. However, a slightly more delayed A2 impulse would reenter through the AP and set the stage for the initiation of AF by wavetail-wavefront interactions upon A4 stimulation.

Figure 4.

Bipolar electrograms show the events leading to AF by reflection at the AP. Left, location of the bipolar electrodes (white balls). Right, electrograms from atrium, AP and ventricle. Atrium-to-ventricle propagation appears continuous for A1 despite the presence of the unexcitable gap. A slightly more delayed A2 impulse reflects and set the stage for AF initiation.

2. Micro-reentry Model

Figure 5 shows a simulation using the micro-reentry model. Conditions are similar to those used for the reflection model with the exception that the AP bifurcated in its mid-length into two separate pathways (slow pathway, SP; fast pathway, FP - see Methods). As shown in Figure 5A, the A1 atrial impulse (white bar) propagated smoothly through both branches of the AP. However, propagation through the FP was blocked unidirectionally at the transition with the ventricle due to source/sink mismatch. The excitation wave successfully conducted into the ventricle via the SP, and a reentrant wave traveled retrogradely through the now repolarized FP.

Figure 5.

Simulation using the micro-reentry model. A. Conditions are similar to reflection model but the AP bifurcates in slow and fast pathways. A1 impulse in the atrium propagated through both AP pathways but was blocked unidirectionally at the fast pathway-to-ventricle insertion. Slow propagation in the other pathway activated the ventricle and allowed for AP reentry and retrograde conduction to the atrium with subsequent AF initiation. B. Time space plot along the white dashed line in the inset shows slow to fast pathway reentry and subsequent front-tail interaction in the atrium between the reentrant beat and the subsequent atrial impulse resulted in a wavebreak and initiation of sustained reentry (see online Movie 2).

A time space plot of the electrical activity along the white dashed profile is given in Figure 5B and a movie of this microreentry simulation is shown in the Online Supplement (Movie 2). As in the reflection model, a front-tail interaction between the reentrant beat and the subsequent atrial impulse resulted in a wavebreak and initiation of reentry (AF) that rotated for about 6 full cycles at a frequency of ~8.2Hz. A 3:1 propagation pattern resulted in a ~2.7Hz ventricular activation. Representative bipolar electrograms for the atrium, slow conducting branch of the AP and the ventricle are shown in Figure 6 to illustrate the striking similarity in the macroscopic reentry patterns obtained in the micro-reentry and reflection models (compare with Figure 4).

Figure 6.

Simulated bipolar electrograms for the atrium, slow pathway in AP and ventricle demonstrate similarity between reentry patterns in micro-reentry and reflection models (compare with Figure 4).

DISCUSSION

The major findings of this study were as follows: 1. A history of AF was twice as common in patients with manifest AP vs. concealed AP irrespective of the AP location. 2. AF was more likely to occur in older males, and in patients with larger atria. 3. A crucial AP property in relation to the occurrence of AF was its ability to conduct from atrium to ventricle, rather than refractory measures. 4. Furthermore, the electrophysiological properties of APs seemed to fulfill the prerequisites for reflection and/or microreentry of atrially initiated impulses as long as the appropriate AP anatomical structure was present. 5. Computer simulations demonstrated that both reflection and micro reentry are possible important mechanisms for AF initiation in mWPW patients via retrograde impulse propagation to the atrium. Similar mechanisms also may trigger AF in patients without an AP, for example at the pulmonary vein left atrial junction.11

Clinical Characteristics and AF prevalence in WPW

Older age, male gender and larger atrial size were associated with a history of AF in this study. These data are confirmative, but their relative importance (Table 2) has not been defined before. It has been suggested previously that a critical mass of atrial tissue is necessary for the sustenance of AF, based on observations that dilated atria are more prone to fibrillate, that AF is more prevalent in species with larger hearts, and is unusual in children in the absence of severe heart disease. The effect of surgical procedures designed to cure AF by reducing the critical mass so that AF cannot be sustained (MAZE III and similar procedures), as well as some variants of AF catheter ablation techniques are further proof of this important concept.12 The observed difference in atrial size between patients with vs. without a history of AF in step 1 fits with this concept. In the present study, the echocardiographic measurements were not adjusted for body surface or patient weight. It is therefore possible that the observed difference in atrial size between the groups is merely related to gender related differences in body size/mass. Even so, the present results support the notion that AF is more likely to occur in larger atria. Together with the association of AF with increasing age, structural factors are also of importance as previously suggested.13

Electrophysiological AP properties and AF

In the present study, antegrade AP properties only had influence on the occurrence of AF during the procedure, in contrast to the Maastricht report (mWPW=57, cWPW=33), which showed a relation between antegrade pathway properties and both spontaneous and inducible AF. The authors suggested a connection between shorter antegrade refractoriness and a higher ventricular response rate during AF leading to increased atrial stretch and hypoxia, and, as a consequence, sustained AF.3 Neither in their study nor in the present study did the retrograde AP properties seem to have any relevance for the risk for AF.

Reflection vs. circus movement re-entry

Our simulations show that the presence of the AP itself, without significant alterations in the atria or ventricles makeup on its end, is sufficient for a generation of either a reflected or circus movement reentry in the atria. The presence of a region of impaired conduction (but not complete block) in a linear pathway (e.g., an AP, a Purkinje fiber or a thin muscle trabecula) may give rise to reentrant excitation even in the absence of an anatomical circuit (see Figure 3). In the reflection model of AP reentry, back and forth activation occurs over the same pathway. Because of the simplicity of the experimental model, reflection has been used to analyze in detail the effects of various conditions (stimulation rate, antiarrhythmic agents, ischemia, etc.) on the manifestation of reentrant activity, specifically single reentrant excitation or extrasystoles.4,5,14 Conditions of cellular heterogeneity are essential for reflection to be demonstrated, as shown by the linear AP model, when the atrial segment was stimulated and action potential propagated toward the AP center. Since cells in the center were not excitable, the action potential was unable to propagate through these cells. Yet the local circuit current generated at the site where the action potential stopped was sufficient to depolarize passively (i.e., electrotonically) the unexcitable cells near the boundary with the ventricular segment. Electrotonic current decays rapidly with distance.15 Thus, if the length of the gap is relatively small (~1 mm), enough current may reach the distal segment to bring the membrane of those cells to threshold and initiate an action potential after an appreciable delay.4,5 In fact, it is the balance between the amount of electrotonic current generated at the AP center (i.e., the source) and the requirement of current for excitation of the ventricular segment (i.e., the sink) that determines whether propagation will be successful, as well as the time required for excitation of the distal segment. 4,5 When the sink-to-source balance is appropriate, atrium to ventricle conduction is not significantly affected. When the source current is appreciably reduced and/or the sink requirements are too high (i.e., low distal excitability), there may be complete block. On the other hand, as shown in Figure 3 for the linear AP model, when the balance between source and sink is such that slow conduction occurs, atrium to ventricle propagation may be so slow that the ventricular action potential will occur at a time when the atrial AP segment has already recovered from activation. Thus, the ventricular segment becomes the source and reactivates the atrial segment (i.e., there is reflection). Finally, as predicted by the linear AP model, AF initiation by the reflected impulse requires a critical timing between the retrograde activation of the atrium to allow its wave-tail to interact with the wave-front of a subsequent atrially initiated impulse and initiate wavebreak and functional reentry.

As shown by our results, the concept of circus movement reentry can also be successfully applied to the understanding of AF initiation by a retrogradely propagating AP impulse. All conditions required by the original idea of circus movement reentry16 may be found in this mechanism, as follows: First, there is a predetermined anatomical circuit. As suggested by the original observations of Öhnell,8 in the case of the WPW syndrome, various types of AP morphology may be observed, including that shown in the anatomical model (Figure 2B) and used as the basis for construction of our branched AP computer model (Figure 2D). Second, there must be unidirectional block prior to the onset of reentry. In the case of our model, unidirectional block occurs at the junction between the fast pathway and the ventricle and is the result of source/sink mismatch. Third, slow conduction in part of the circuit facilitates reentry. Fourth, the wavelength of the impulse must be shorter than the length of the circuit. As shown in Figure 5, there is always a segment within the circuit that remains excitable during reentrant activity.

Initiation of reflection as well as micro-reentry depends strongly on the spatial and geometrical properties of the AP. For the reflection model, a critical parameter in determining whether or not reflection will occur is the time delay between the proximal and distal excitations due to the passive conductance. Due to the schematic and abstract representation of the APs in our computer models, assessing and quantifying critical values for AP's geometrical characteristics (width, length, angular aperture etc.) that may favor reflection and/or micro-reentry will not be directly meaningful to the clinical setting. Moreover, reflection and micro-reentry are multi-factorial scenarios. In our simulations, we set a fixed geometry for reflection, and another one for micro-reentry. We could have obviously adopted other geometries with different AP structural properties, and find their specific electrophysiological properties (pacing frequency, tissue properties) that promote reentry. However, the above theoretical arguments are based on solid basic dynamical properties of cardiac electrical activity and are therefore valid. A more detailed discussion is found in the Online Supplement.

Which of the two mechanisms of AF initiation predicted by our model prevails in any given patient clearly depends on the structural properties of his/her AP, and cannot be defined in vivo by recording the localized electrical activity (cf. Figure 4 & Figure 6). Some APs have an unexcitable gap– at least on the left side – when crossing the annulus, provided there is no continuous myocardial “wrapping” of the CS in which the AP passes. Other APs are thicker on the atrial side, but sometimes branch on the ventricular side, which increases the area of connection but decreases the safety factor for conduction. Therefore, branching at the ventricular insertion could theoretically provide a substrate for microreentry, provided there is unidirectional antegrade block (A to V) in one of the branches through which electrical activity then returns with enough safety factor for conduction. This alternative would in essence cause an identical situation on the atrial side as reflection, i.e. an atrial extrasystole entering the AP anterogradely could return with some delay retrogradely and become a second triggered atrial extrasystole. Both mechanisms require antegrade AP conduction (mWPW). Finally, it should be noted that atrial remodeling (not studied here) induced by the circus movement tachycardia per se might also be an important pathophysiological mechanism present in both manifest and concealed APs.17 In our cohort there was, however, no evidence of more frequent episodes or longer history of tachycardias in patients with a history of AF.

Limitations

In an individual patient many factors might contribute to the occurrence of AF, including the rate and duration of any single tachycardia, which may lead to atrial remodeling and AF.17 Also alterations in autonomic nervous activity, ingestion of alcoholic and caffeine containing beverages, infections, and other modulating factors might contribute and cannot be controlled for. It is, however, of significance that AF occurring before successful AP ablation in a substantial proportion (≤ 75%) of WPW patients disappears after a successful procedure.1,2 Thus, the AP itself seems crucial.

Finally, we used computer simulations to test our 2 hypothesized mechanisms for AF initiation in mWPW patients. The simulations were aimed at demonstrating conceptual scenarios and several simplifications and ion channel modifications were employed. First, we constructed a 2-D rather than 3-D geometry model. Due to the linear structure of the APs, we consider our 2-D model reasonable, as extending it into 3-D is not expected to significantly change the electrical propagation pattern in the AP cable, but only alter the source-to-sink ratios at the AP interfaces with the atrium and the ventricle. Next, we have slightly modified several ion channels properties in order to increase tissue excitability, and assumed a low concentration of ACh. We found that these changes were required to increase the likelihood of reflection and to increase the stability of the reentrant activity, but still, we cannot exclude other possible alterations that would achieve a similar outcome. Nevertheless, we coordinated these modifications in such a way as to keep global dynamical properties (e.g. action potential duration, conduction velocity and antegrade refractory measure) within the physiological range. And last, our micro-reentry model required a reduced ventricular conduction velocity to allow the fast pathway enough time for repolarization before being retrogradely activated from the ventricle. This velocity is compatible however with the transverse propagation velocity of the electrical wave between the slow and the fast branches’ insertions. Similar results would have been obtained for a longitudinal propagation velocity if the distance between the insertions of the slow and fast branches would have been approximately twice as large compared to the distance set in the model used in this study.

CONCLUSION

In patients with an AP, the propensity for AF is strongly related to preexcitation, larger atria, male gender and older age. We found no correlation between the occurrence of AF and measured electrophysiological properties of the APs in this study. Reflection and micro-reentry at the AP may be important mechanisms for AF initiation in patients with manifest (preexcited) Wolf-Parkinson-White syndrome. Similar mechanisms may trigger AF also in patients without an AP.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The technical assistance of Margareta Arfs R.N and Mats Andersson RN is gratefully acknowledged as is the statistical advice from Thomas Karlsson.

Supported in part by grants from the USA National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (P01-HL39707; R01-HL70074; R01-HL 80159 to J.J.), the Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation (to LB), and Sahlgrenska University Hospital (to LB).

Abbreviations

- A1,2,3,4

atrial impulse number 1, 2 etc.

- AF

atrial fibrillation

- AP

accessory pathway

- cWPW

concealed WPW, i.e. without preexcitation, delta-wave, ventriculo-atrial conduction only

- ECG

electrocardiogram

- EP

electrophysiology, electrophysiological

- FP

fast pathway

- IACT

inter-atrial conduction time

- mWPW

manifest WPW, i.e. with preexcitation, delta-wave

- LACT

left atrial conduction time

- RACT

right atrial conduction time = PA interval

- SP

slow pathway

- TSP

time-space plot

- WPW

Wolff-Parkinson-White

- 2-D

two-dimensional

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

There are no conflicts of interest related to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Oddsson H, Edvardsson N, Walfridsson H. Episodes of atrial fibrillation and atrial vulnerability after successful radiofrequency catheter ablation in patients with Wolff-Parkinson-White. Europace. 2002;4:201–206. doi: 10.1053/eupc.2002.0223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dagres N, Clague JR, Kottkamp H, et al. Impact of radiofrequency catheter ablation of accessory pathways on the frequency of atrial fibrillation during long-term follow-up. High recurrence rate of atrial fibrillation in patients older than 50 years of age. Eur Heart J. 2001;22:423–427. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2000.2429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Della Bella P, Brugada P, Talajic M, et al. Atrial fibrillation in patients with an accessory pathway: importance of the conduction properties of the accessory pathway. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17:1352–1356. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(10)80146-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antzelevitch C, Jalife J, Moe GK. Characteristics of reflection as a mechanism of reentrant arrhythmias and its relation to parasystole. Circulation. 1980;61:182–191. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.61.1.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jalife J, Moe GK. Excitation, conduction, and reflection of impulses in isolated bovine and canine cardiac Purkinje fibers. Circ Res. 1981;49:233–247. doi: 10.1161/01.res.49.1.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aunes-Jansson M, Wecke L, Lurje L, et al. Persistent T wave inversions following successful ablation of 125 posteroseptal accessory pathways: observations on cardiac memory and clinical implications. Int J Cardiol. 2006;106:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2004.12.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuck K-H, Friday KJ, Kunze K-P, et al. Sites of conduction block in accessory pathways. Basis for concealed conduction. Circulation. 1990;82:407–417. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.82.2.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Öhnell RF. Pre-excitation. A cardiac abnormality. Acta Med Scand. 1944 Suppl 152 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson RH, Bekker AE. Anatomy of the conduction tissues and accessory atrioventricular connections. In: Zipes DP, Jalife J, editors. Cardiac electrophysiology: From cell to bedside. Philadelphia WB: Saunders; 1990. pp. 240–248. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spach MS, Dolber PC, Heidlage JF. Interaction of inhomogeneities of repolarization with anisotropic propagation in dog atria. A mechanism for both preventing and initiating reentry. Circ Res. 1989;65:1612–1631. doi: 10.1161/01.res.65.6.1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Atienza F, Jalife J. Reentry and atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2007;4(3 Suppl):S13–S16. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klein GJ, O’Neill MD, Hocini M, et al. Occam's razor and the unravelling of atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2007;18:451–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tanaka K, Zlochiver S, Vikstrom KL, et al. Spatial distribution of fibrosis governs fibrillation wave dynamics in the posterior left atrium during heart failure. Circ Res. 2007;101:839–847. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.153858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cabo C, Barr RC. Reflection after delayed excitation in a computer model of a single fiber. Circ Res. 1992;71:260–270. doi: 10.1161/01.res.71.2.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weidmann S. The electrical constants of Purkinje fibers. J. Physiol (Lond) 1952;118:348–360. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1952.sp004799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mines GR. On dynamic equilibrium in the heart. Journal of Physiology. 1913;46:349–383. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1913.sp001596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wijffels MC, Kirchhof CJ, Dorland R, et al. Atrial fibrillation begets atrial fibrillation. A study in awake chronically instrumented goats. Circulation. 1995;92:1954–1968. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.7.1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.