Abstract

Contrast agents targeted to molecular markers of disease are currently being developed with the goal of identifying disease early and evaluating treatment effectiveness using non-invasive imaging modalities such as MRI. Pharmacokinetic profiling of the binding of targeted contrast agents, while theoretically possible with MRI, has thus far only been demonstrated with more sensitive imaging techniques. Paramagnetic liquid perfluorocarbon nanoparticles were formulated to target αvβ3-integrins associated with early atherosclerosis in cholesterol-fed rabbits in order to produce a measurable signal increase on magnetic resonance images after binding. In this work, we combine quantitative information of the in vivo binding of this agent over time obtained via MRI with blood sampling to derive pharmacokinetic parameters using simultaneous and individual fitting of the data to a three compartment model. A doubling of tissue exposure (or area under the curve) is obtained with targeted as compared to control nanoparticles, and key parameter differences are discovered that may aid in development of models for targeted drug delivery.

Keywords: nanoparticles, αvβ3-integrin, pharmacokinetic, binding

Introduction

The ability to track drug delivery and disposition is critical to the development and assessment of new therapeutic agents. Detailed analysis of absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) is required by regulatory agencies that govern the approval process. Traditional pharmacokinetic studies for pharmaceutical agents involve blood and tissue sampling to determine concentrations, which serve as inputs to compartmental or mechanism-based models for calculation of dose/effect relationships (1). The underlying assumption in this approach for soluble agents is that sequestration of the agent at the intended site of effect is driven by concentration gradients in the blood, interstitial space, or tissue of interest.

The recent emergence of new platforms and paradigms for drug delivery with the use of high-payload, molecularly-targeted nanoparticle drug/gene carriers represents a challenge to the application of these conventional modeling approaches. Such vehicles carry large payloads of drug and ideally are designed to preferentially release the active therapeutic agent only when bound to the target (2). For these carrier-borne agents, blood and tissue concentrations may not provide the most accurate depiction of in vivo pharmacokinetics and dynamics, because the intermediate step of binding is a prerequisite for drug release. Accordingly, the ability to accurately model the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of these systems will require new approaches that account for the binding and delivery steps, which introduces more complexity than is considered in modeling freely diffusible substances.

Our lab has developed one such delivery nanovehicle that can be targeted to early molecular biomarkers of vascular disease (3,4). The system comprises a 200 nm diameter nanoparticle composed of a liquid perfluorocarbon core material surrounded by a lipid monolayer that can be functionalized to attach targeting ligands, imaging agents, and drugs (2,5). A major area of interest for use of this particle has been the identification and site-targeted therapy of pathological angiogenesis. For example, it has been shown that the earliest stages of atherosclerosis are characterized by penetration of neovasculature developing around the existing vasa vasorum into the arterial media and intima to support plaque development by establishing new supply avenues (6–9). To detect the development of this critical neovasculature noninvasively, we have combined an αvβ3-integrin binding ligand with an MR-sensitive imaging agent (gadolinium) that can be carried together on this long-circulating liquid perfluorocarbon nanoparticle. When injected intravenously into atherosclerotic rabbits, the nanoparticles target the aortic neovasculature, resulting in specific enhancement of MRI signal from early plaques (10). When drugs capable of inhibiting this vascularization, such as fumagillin, are included in the nanoparticle formulation, the nanoparticles can be used for serial evaluation of drug efficacy non-invasively using imaging (5).

Fortuitously, the signals emanating from these MR images can be quantitatively related back to T1, T2, and proton density, allowing model-based calculation of the concentration of nanoparticles bound to vessels in particular imaging voxels (11,12). We propose that by combining such information with traditional pharmacokinetic (PK) analysis, the distribution and binding of the targeted nanoparticles might be further clarified with compartmental analysis. Although indexes derived from compartmental modeling of dynamic contrast enhanced MRI have been correlated with the presence of leaky tumor vasculature and other disease markers (13,14), as of yet no specifically targeted contrast agents for MRI have been quantitatively modeled to characterize specific molecular binding in vivo. This is due in part to the limited availability of signal-rich target-specific magnetic resonance contrast agents, which has hampered MR pharmacokinetic approaches for application to molecular imaging; however, the lack of ionizing radiation and ability to perform high resolution anatomical localization of binding present as major advantages to this technique. Perfluorocarbon nanoparticles, which can carry up to 90,000 gadolinium chelates each, can achieve the necessary sensitivity for use in vivo (12) and thus might be useful for determining binding information with MRI. Accordingly, in this study, we sought to demonstrate and model the in vivo pharmacokinetic and receptor binding properties of these αvβ3-targeted nanoparticles in a cholesterol-fed rabbit model of early atherosclerosis. This information is expected to offer a powerful tool for defining in vivo ADME and targeting features for this class of dual molecular imaging and targeted drug delivery agents.

Methods

Overview

Cholesterol-fed rabbits, which develop atherosclerosis and display αvβ3-integrin expression in their adventitia, were injected with either αvβ3 targeted or non-targeted nanoparticles, both of which contained gadolinium. Blood samples were drawn periodically throughout the study to determine the bulk pharmacokinetic behavior of the nanoparticles and T1-weighted MR imaging of a section of the descending aorta of each rabbit was performed over a 24 hour period to ascertain the binding characteristics. The blood concentrations and MR signal enhancement served as inputs to a 3-compartment pharmacokinetic model that was intended to differentiate the targeted and non-targeted nanoparticles.

Nanoparticle formulation

Two different nanoparticle formulations were used in this study, one of which was targeted and one not targeted for use as a control nonbinding agent. All agents were formulated as described previously (4). Briefly, nanoparticles were composed of 20% (v/v) perfluorooctylbromide (PFOB), 2% (w/v) of a surfactant comixture, and 2.3% (w/v) glycerin, with water comprising the balance. The surfactant comixture included 69 mole% lecithin (Avanti Polar Lipids Inc), 1 mole% phosphatidylethanolamine (Avanti Polar Lipids Inc), and 30 mole% gadolinium diethylene-triamine-pentaacetic acid-bisoleate (Gateway Chemical Technologies) in chloroform:methanol (3:1), which was dried to a lipid film under vacuum. The targeted nanoparticle formulation included 0.1 mole% peptidomimetic vitronectin antagonist (the αvβ3-integrin targeting ligand, US Patent 6,322,770) (15–17) conjugated to polyethylene glycol (PEG)2000-phosphatidylethanolamine (Avanti Polar Lipids Inc), which was added to the surfactant mixture with a concomitant reduction in lecithin. The surfactant components were prepared as published elsewhere (5), combined with PFOB and distilled deionized water, and emulsified (Microfluidics Inc) at 20,000 psi for 4 minutes. Particle sizes were determined at 37°C with a laser light scattering submicron particle analyzer (Malvern Instruments).

To determine the relationship between signal enhancement and concentration of nanoparticles present, a series of phantoms was created by mixing different concentrations of targeted nanoparticles into anticoagulated human blood samples. T1 and T2 values for each phantom were determined at 1.5 T at room temperature from a mixed inversion recovery and spin echo sequence (18) that is resident on the clinical scanner for this purpose (TE = 30 ms, eight echoes, two averages per scan, slice thickness =4 mm, SE TR =1000 ms, IR TR =1500 ms, inversion time = 500 ms, and in-plane resolution = 0.35 mm x 0.35 mm). These samples were then imaged with the same TSE sequence that was used for the in vivo imaging (see below) to determine contrast characteristics. Signal enhancement was calculated as the percent increase in signal observed after nanoparticle accumulation as compared to the baseline (no nanoparticles). Average gadolinium content for both targeted and non-targeted nanoparticles was determined using neutron activation analysis (see below).

Pharmacokinetic studies of nanoparticle distribution in rabbits with MRI

Male New Zealand White rabbits were fed 0.25% cholesterol (n=10) for approximately 115 days prior to imaging to induce atherosclerosis (19). Total blood cholesterol levels and liver enzymes were monitored with periodic sampling, and the dietary levels of cholesterol were modified if animal health appeared to decline from the cholesterol load (cholesterol > 1500 mg/mL and bilirubin > 3.5 mg/dL). Two groups of cholesterol-fed rabbits were used to characterize the binding of the particles in vivo. One group received αvβ3-targeted, paramagnetic nanoparticles (n=6), while the other received nontargeted, paramagnetic nanoparticles (n=4). Each one was anesthetized with an intramuscular injection of 30 mg/kg and 6 mg/kg of ketamine/xylazine respectively and intubated. An injection catheter was placed in each ear, one in the vein for nanoparticle injection and one in the artery for blood sampling. The animal was maintained with 1.5-3% isoflurane in oxygen on a ventilator for approximately 3 hours during the duration of the six dynamic scans, which included a baseline (pre-injection scan), followed by scans at 30, 60, 90, 120, and 150 minutes post-injection of 1 mL/kg of the chosen nanoparticle agent. During this time, approximately 1 mL of blood was sampled at 9 different times (pre-injection and 1, 5, 10, 20, 30, 45, 90, and 150 minutes post-injection) followed by saline replacement. After the duration of scanning, the animal was allowed to recover until the next imaging time points at 8.5, 12.5, and 24 hours post-injection. For each of these individual scans, the animal was anesthetized with 2–3% isoflurane via nosecone (no intubation), and a single 1 mL sample of blood was removed, followed by saline replacement. The actual times of blood removal and scanning were recorded. After completion of all imaging, the animal was euthanized with 1 mL of Euthasol (Delmarva Laboratories Inc). The experimental protocol was approved by the Animal Studies Committee of the Washington University School of Medicine.

At each imaging time point, cross-sectional images of the descending thoracic aorta of each rabbit were obtained using a 1.5 T clinical magnet (Acheiva, Philips Medical Systems) and a quadrature birdcage radiofrequency receive coil. Multislice, T1-weighted, turbo spin-echo, fat-suppressed, black-blood imaging of the aorta was performed over a 4 cm section of the aorta (repetition time=380 ms, echo time=11 ms, TSE factor= 4, 250x250-hm in-plane resolution, 4-mm slice thickness, number of signals averaged=8). To null the blood signal, sliding saturation bands were imposed proximal and distal to the region of aortic image acquisition and then moved with each selected imaging plane. A fiduciary marker comprised of Omniscan® doped water was included in the imaging field of view to normalize the signal intensity of each set of images. Signal enhancement was quantified using a manual segmentation algorithm custom developed in MatLab. The signal enhancement of the aortic wall and adjacent muscle was calculated slice by slice with respect to the baseline images. The aortic wall signal was normalized to the adjacent muscle signal to correct for coil sensitivity and intensity scaling, and the average value of all ten contiguous slices were compared to the average baseline signal to generate a percent enhancement value. Consistency in slice positioning between each set of time points was accomplished via a series of scans prior to the enhancement scans, including a standard 3-plane scout, a multi-2D time of flight (TOF) scan, and a phase contrast angiography scan designed to depict flow in the aortic arch. The T1-weighted scans used for analysis were placed such that the center of the most cranial slice was placed at the caudal edge of the aortic arch in the maximum intensity projection of the PC angiography scan and oriented to be perpendicular to the flow in the descending aorta.

Neutron activation analysis for tissue gadolinium concentration

Calibration samples of both targeted and non-targeted emulsions and all blood samples were sent for neutron activation analysis to precisely determine gadolinium content. Samples were weighed and lyophilized before being analyzed at the University of Missouri Research Reactor as described previously (12).

Pharmacokinetic models

A standard two compartment pharmacokinetic model was used to describe the blood concentrations when modeled without taking into account any imaging data. The closed-form solution to this model is the well-described bi-exponential equation:

| [1] |

with constants A and α describing the distribution phase, and B and β describing the clearance phase.

For simultaneous modeling of the blood and aortic wall concentrations, a three-compartment pharmacokinetic model was developed to describe the behavior of the nanoparticles in vivo (Fig 1). Compartments 1 and 2 represent the bulk distribution of nanoparticles throughout the blood stream, with transfer constants k12 and k21 and distribution volumes v1 and v2. An elimination constant, ke, is used to describe clearance of the nanoparticles from the blood via the reticuloendothelial system (20). The vasa vasorum of the aortic wall is assumed to be a small volume third compartment where specific binding to αvβ3-integrins can occur. The constants that describe the transfer into and out of this compartment, k13 and k31, are lumped parameters that are used to describe both passive transfer and active binding.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the three compartment model used to describe the data. Compartments 1, 2, and 3 are blood, peripheral, and aortic wall, respectively. The model is entirely determined by the values of the six constants, k12 (hr−1), k21 (hr−1), k13 (hr−1), k31 (hr−1), v1 (L/kg), and ke (hr−1).

The ordinary differential equations that govern this model are:

| [2] |

| [3] |

| [4] |

where yn is the amount of nanoparticles in compartment n. The other variables have already been identified above. Conversion between the absolute amount of nanoparticles and the concentration in a particular compartment is accomplished via another fitted parameter, vn, which represents the volume of compartment n (normalized to body weight). The pharmacokinetic data were represented as , with .

Preliminary regression results showed that v3 was highly positively correlated with k13 with little change in the “goodness of fit” criteria. Therefore, to adequately analyze the effect of active targeting, v3 was fixed at the reasonable value determined from this preliminary fitting of 1x10−3 L·kg−1. The bolus dose administered for each rabbit was 1 mL/kg emulsion, which equates to 4.6 μmol Gd/kg body weight.

Algorithm for simultaneous fitting

The pharmacokinetic analysis for the biodistribution of gadolinium in both the blood and the aortic wall was performed using the 2- and 3-compartment open models described above. The maximum likelihood estimate of the model parameters is obtained by minimizing the sum of squared residuals, termed “chi-square”:

| [5] |

where N is the number of data point, M is the number of fitted parameters a, and σ is the measurement error. The downhill simplex method (21) was used to minimize chi-square using 200 simulations with randomly selected, but bounded, initial guesses designed to escape any local minima in the chi-square surface.

The fitting of the pharmacokinetic data was performed in two steps. First, the pharmacokinetic parameters that describe the gadolinium concentration in the blood (k12, k21, ke, v1) and aortic wall (k12, k21, ke, v1, k13, k31) of individual rabbits were fit separately using the 2- or 3- compartmental model, respectively. The values obtained are then used as initial guesses for the simultaneous fitting, which is performed by minimizing the sum of the blood and aortic wall chi-square functions for a given rabbit.

Statistical Analysis

Differences between the treatment groups and parameters were evaluated for significance using analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the Statistical Analysis System (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). A two-tailed p-value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Nanoparticle Characterization and MR Signal Modeling

Nanoparticles were nominally 213 and 247 nm in diameter (non-targeted and targeted respectively), and contained an average of 4.6 mM gadolinium, which correlates with approximately 63,000 and 99,000 gadolinium chelates per particle. Each nanoparticle in the targeted emulsions contained ~500 copies of the αvβ3 peptidomimetic ligand.

Six phantoms containing nanoparticles mixed with blood (0, 6.4, 13.8, 22.1, 32.2, and 44.6μM gadolinium) were used to determine the relationship between nanoparticle concentration and signal enhancement. The calculated r1 relaxivity based on T1 values obtained from the mixed MRI pulse sequence was 12.7 ± 1.7 mM−1s−1 (r2 = 0.94), which is similar in magnitude to previously reported values (22). However, the low T2 values measured in the blood due to iron content resulted in a less reliable calculation of an r2 relaxivity (10. 4 ± 10.6 mM−1s−1; r2 = 0.2). The calculated percent enhancement was approximately linear with gadolinium concentration at these low concentrations (slope = 1.40 ± 0.21; 95% confidence interval), which is consistent with simulations using the signal modeling equations for a TSE sequence with the parameters used. The slope of line of best fit to the phantom data was therefore utilized for calculating gadolinium concentrations from the in vivo signal intensity data (Fig 2). This essentially assumes that the nanoparticles exhibit the same relaxivity in vitro (unbound) as that measured in vivo (bound), an assumption which was examined in a previous study (12).

Figure 2.

Relating MR signal enhancement to the concentration of gadolinium contained on nanoparticles. The diamonds represent the experimental data acquired using phantoms, the solid line shows the results of least squared regression of the data (slope = 1.40, intercept = 1.68, r2=0.99), and the dotted lines represent the confidence intervals on the fit.

PK analysis of blood concentrations

The concentration of gadolinium in the blood over time followed a bi-exponential decay typical of these perfluorocarbon nanoparticle agents (Fig 3) (23). In all ten animals, the standard two compartment model resulted in very good fits to the data, with R2 > 0.98. The fitted parameters did not differ significantly between the rabbits treated with targeted versus non-targeted nanoparticles (Table I), although a trend toward a higher elimination rate constant (ke) was observed in the αvβ3-targeted group. The half-life for the distribution phase was 20.2 ± 4.1 minutes (mean ± standard error), while the elimination half-life was 11.9 ± 2.7 hours.

Figure 3.

Gadolinium concentration in the blood of a single representative rabbit over time (circles), and the line of best fit to a two compartment pharmacokinetic model (solid line).

Table I.

Comparison of fitted parameters from the two compartment model of blood concentration of gadolinium in rabbits given targeted or non-targeted nanoparticles

| Parameter | Units | Targeted Group (Mean ± St. Error) | Non-Targeted Group (Mean ± St. Error) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| k12 | hr−1 | 1.22 ± 0.17 | 0.948 ± 0.30 | 0.37 |

| k21 | hr−1 | 1.29 ± 0.18 | 1.10 ± 0.33 | 0.59 |

| ke | hr−1 | 0.126 ± 0.0084 | 0.0984 ± 0.0099 | 0.09 |

| v1 | L/kg | 0.0611 ± 0.0051 | 0.0632 ± 0.0043 | 0.79 |

MR imaging of the aorta

All animals survived the 24 hour imaging and blood sampling protocol. A dynamic scanning protocol was used for the first six time points while the rabbit remained sedated in the scanner, which ensured consistent slice positioning and avoided need for re-shimming, re-scaling, or gain adjustments (example images shown in Fig 4). Therefore, these data points represent the most consistent and reproducible information, and they reveal some interesting patterns (Fig 5 A). The first scan acquired immediately after nanoparticle injection manifests a substantial and reproducible increase in signal intensity within the aortic wall, with no significant difference in intensity between the two groups. This intensity spike likely represents a bolus or first-pass effect of the contrast agent before it becomes thoroughly mixed with the blood. This feature produces a “delta function” in both the signal enhancement and concentration data, which is difficult to fit using a simple three compartment model. Because this spike is uninteresting for purposes of compartmental kinetics in our first order approximation and to reduce the number of required fitted parameters this initial data point was discarded from the simultaneous fitting model. The next imaging time point at 30 minutes post-injection demonstrates that while the signal intensity in the group receiving non-targeted nanoparticles has nearly returned to its baseline value, the signal remains high in the targeted group, indicative of binding and retention in the neovasculature. The subsequent scanning time points demonstrate a relatively steady increase in signal in both groups, an effect which is consistent with the relatively slow transfer from the main blood compartment into the small, abnormal capillary buds that branch out from the expanding vasa vasorum of the aorta.

Figure 4.

A) A screen capture of the scan planning utilized for the T1-enhancement scans of the aorta acquired each time the animal was placed in the scanner. A maximum intensity projection of a time of flight acquisition (left) and phase contrast angiography (right) of the aortic arch was used to place the saturation bands (blue slabs) for black blood imaging and the T1-weighted slices of the descending aorta (yellow and red lines). B) A series of images of the aortic wall (arrow, zoomed in) from a rabbit given targeted nanoparticles at the same anatomic slice location at the indicated time points.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the average signal enhancement in the aortic wall as a function of time between the rabbits given targeted or non-targeted nanoparticles. A) Early time points acquired with dynamic scanning. B) Entire data set. Data points represent the mean ± standard error. Annotations at a particular time point indicate whether the non-targeted and targeted signals were statistically different (t indicates a trend p<0.08, * p<0.05, ** p<0.005).

The later imaging time points indicate that both groups have reached their maximum signal enhancement value between 2.5 and 8 hours, with the targeted group returning to its baseline value at 12.5 hours (Fig 5 B). The two last time points acquired for the non-targeted group actually demonstrate a paradoxical negative signal enhancement, meaning that the average signal in the aortic wall has decreased below the initial starting value, for reasons that remain undetermined. For purposes of signal modeling, these intensities would generate negative values for contrast agent concentration, which is a physical impossibility. However, because the targeted group does not demonstrate this behavior, the difference between the two groups is likely real regardless of the cause. Therefore, to maintain objectivity for the fitting procedure, the negative contrast agent values were retained in the simultaneous fitting. If image quality was deemed insufficient (due to motion or radiofrequency noise, for instance), the data from that time point was not included in the average values shown in Fig 4 and was discarded from the simultaneous pharmacokinetic fit. One rabbit receiving non-targeted nanoparticles was removed from the individual fit entirely due to a poor quality baseline scan, leaving nine rabbits total (n=5 targeted, n=4 non-targeted), of which an average of 4.2 and 3.8 rabbits (targeted and non-targeted, respectively) were used per time point, with never fewer than 3.

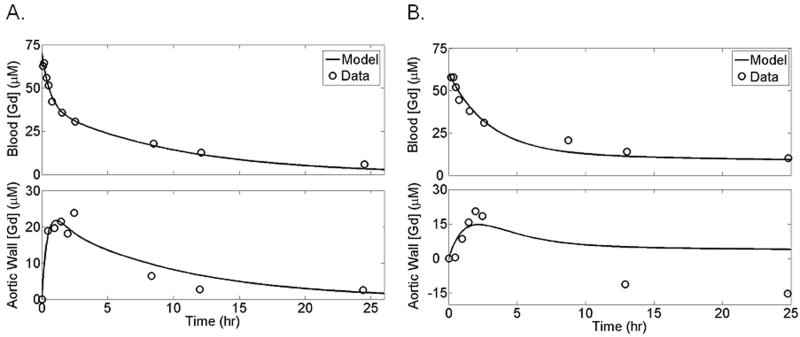

Simultaneous fitting of blood and aortic wall concentrations

Example plots illustrating the results of simultaneous fitting of both the blood and aortic wall as separate compartments for an individual rabbit are shown for a rabbit given targeted (Fig 6 A) versus non-targeted (Fig 6 B) nanoparticles. The adjusted R2 value for the combined fits ranged from 0.89 to 0.97, although the goodness-of-fit to the blood data was substantially higher than that for the noisier and less frequently sampled aortic wall signal (unadjusted range of R2 values of 0.93-0.91 for blood compartment and 0.37–0.91 for aortic wall compartment).

Figure 6.

Simultaneous pharmacokinetic fitting of nanoparticles containing gadolinium in the blood and binding within the aortic wall of one example rabbit given targeted (A) or non-targeted (B) nanoparticles. Individual measurements (circles) and the determined fit (solid line) are shown.

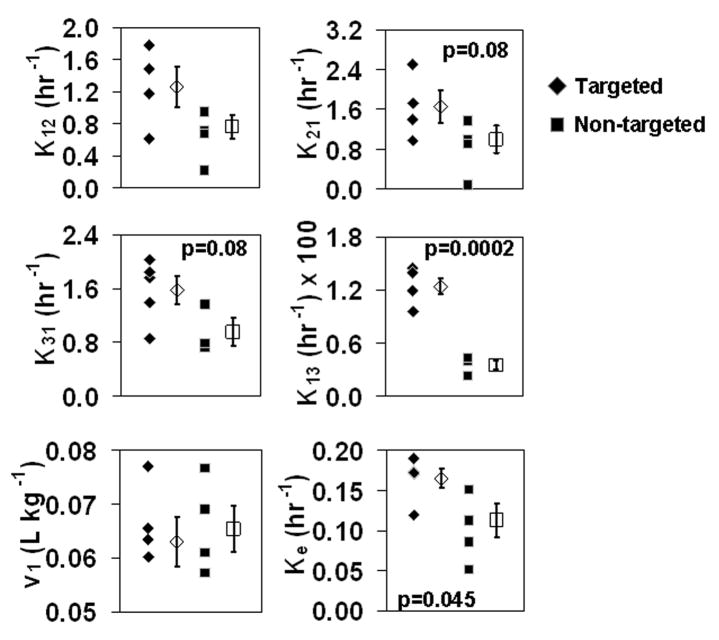

Scatter plots for each of the six pharmacokinetic parameters that were fit with this three compartment model are shown in Fig 7. One outlier in the targeted group was removed from the k12 and k21 parameters, while one in the non-targeted group was removed from k13 and k31 due to a deviation from the mean of the other values of greater than 5 standard deviations. While no significant differences were observed in k12, k21, v1, or k31, differences did emerge among the groups for the parameters of k13 (transfer into the aortic wall compartment from the blood) and ke. Interestingly, while a trend toward higher ke was observed for targeted nanoparticles when the blood compartment alone was fit (see Table I), this difference only became significant when both sets of data were fit simultaneously.

Figure 7.

Scatter plots showing the distribution of fitted parameters from the simultaneous fitting using the three compartment model (filled symbols represent parameters from individual rabbits, whereas open symbols show the mean ± standard error of each group).

Discussion

These experimental observations and model-derived PK indexes demonstrate the concept of using magnetic resonance imaging as a method for noninvasive quantification of the binding of a molecularly targeted contrast agent, which is an approach heretofore rendered practical only for nuclear and optical imaging methods (24,25). Here, we have combined the image-based MR signal quantification of nanoparticle binding with traditional blood sampling measurements in individual animals and we have shown that simultaneous fitting of multi-compartmental pharmacokinetic parameters can be accomplished, thereby providing insight into the compartmentalization and mechanism of action for targeted nanoparticle agents.

When the average pharmacokinetic parameters obtained from each of the two groups of rabbits are used to calculate a traditional index of availability, the area under the curve (AUC), we confirm that site concentration as a function of time is doubled with targeted nanoparticles as compared with non-targeted particles (1.64 vs. 0.84 nmol Gd/g tissue·hr, respectively). This augmentation of local availability occurs despite the fact that the AUC for blood concentrations are very similar (3.28 vs. 3.60 nmol Gd/mL blood·hr). The maximum amount of gadolinium that reached the targeted site was 0.18% of the total dose given when non-targeted and 0.38% of the dose with targeted nanoparticles. The fairly small percentage of the dose that reaches the site is a reflection of the small volume of that compartment.

Despite the low relative proportion of material that is retained in the vascular wall, it is sufficient to yield a significant tissue signal increase and offers proof of efficacy for molecular imaging with targeted agents. We also point out that this signal increase is achieved in the face of the very low serum doses of gadolinium used (4.6x10−3 mmol Gd/kg body weight) as compared with doses of conventional gadolinium agents (0.1 mmol/kg), representing a factor of 20x less gadolinium for nanoparticle-based delivery. The potential safety advantages of this feature are compelling in that large intravenous boluses of gadolinium are not required to produce a measurable signal at the targeted tissue site. Of course, in the case of nanoparticles, some of the effect occurs by trapping of particles via EPR-like mechanisms (“endothelial permeability and retention”), but targeting still augments the signal as indicated in the AUC24 calculations.

The primary mechanism for this increase in exposure is the statistically higher k13 parameter in the pharmacokinetic model, leading to an increase in concentration of nanoparticles at the relatively early time points. In fact, the maximum difference in signal intensity between targeted and non-targeted groups is predicted to occur at approximately 1 hour according to a simulation using the average fitted parameters. While in the standard definition of a three compartment model, k13 represents the passive transfer of material from the blood to the third compartment, the nanoparticles are not just passively transferring but also actively binding. These two effects can not be differentiated with this model and combine together, resulting in an apparent increase in k13. While more sophisticated models might be developed to tease apart the two effects, we chose to use this simplified approach to reduce the number of fitted parameters and to aid in interpretation of the results. The decision to disregard the initial peak in intensity that occurs in the aortic wall immediately after nanoparticle injection may also influence the interpretation of the data. Because the intensity in the targeted group remains high after this initial spike while the non-targeted group almost returns to baseline, the difference between them might actually be a difference in specific retention of targeted nanoparticles as the initially high concentration drives more binding. Future pharmacokinetic modeling of this data may incorporate this effect.

Statistical significance was not achieved in the parameter k31, transfer from the third compartment back into the blood, as might be expected if the nanoparticles remained trapped in the third compartment, which must be the case since the MR image signal remains elevated as compared to the blood signals. It is possible that the nanoparticles remain in the third compartment for a similar length of time whether they are specifically or non-specifically bound, so that k31 is the same in either case. Furthermore, determination of k31 also may have reflected: 1) infrequent sampling of the decreasing aortic wall concentrations than was performed for the early time points; and 2) the use of a slightly different imaging protocol (non-dynamic, animal removed from scanner, etc.) during the downward portion of the aortic wall concentration curve, which made it difficult to accurately determine the low concentrations at those times. Because one of the major goals of this study was to track blood concentrations and binding over time in the same animals, this difference in protocol was unavoidable to ensure the health of the subjects. The reduction in signal intensity at the 8.5, 12.5, and 24 hour time points below baseline in the non-targeted group represents another source of potential error in determining k31. While the exact cause is not intuitively obvious, technical possibilities have been ruled out or corrected for, including changes in scanner gain or scaling, and the use of the adjacent muscle tissue for intensity correction. However, the variety of physiological changes that occurred during the study as a consequence of multiple anesthetizations, repeated blood sampling, and reduced water and food intake, could underlie a true shift in innate proton density, T1, and/or T2 of the tissue, an effect which this study was not designed to measure. Future inclusion of a sham injection group would be advantageous for this purpose.

In this study, we chose to track the gadolinium on the nanoparticle surface as a surrogate marker for nanoparticle presence and binding. It is possible that the gadolinium becomes disassociated from the nanoparticle surface, particularly when bound to a cell surface or after interacting with blood lipoproteins. While methods exist for tracking other components of the nanoparticle, such as the perfluorocarbon core (26,27), the gadolinium likely acts as a surrogate marker for the components of the lipid monolayer, which may be useful for tracking drug delivery with this agent (5). The effect of the nanoparticles’ gadolinium when mixed in solution in vitro was assumed to parallel its effect in vivo, which is the same as assuming that the relaxation rates do not change between these two conditions. In the case of a targeted agent, where local concentrations of gadolinium may exceed this linear regime because of bulk susceptibility or binding to sites with poor water access, more sophisticated models could be developed. However, prior work in vitro has indicated that many of these effects are not significant in the case of our nanoparticles because relaxometric measures of targeted concentrations agreed well with analytical values (12).

One potential application of this technique is for development of pharmacodynamic models for site-targeted nanoparticle agents. The lipophilic gadolinium chelate used in this nanoparticle formulation can be envisioned as a surrogate marker for any drugs that might be incorporated into the lipid layer, such as doxorubicin, paclitaxol, or fumagillin (2,5). Standard methods for pharmacodynamic modeling use systemic blood concentrations of drug as an input to an Emax or other nonlinear pharmacodynamic model to analyze its effects (28,29). Noninvasive imaging techniques, however, allow monitoring of the actual concentration of the drug at the site (30), potentially serving as a more accurate parameter to predict subsequent effects. This feature should become increasingly important as more site-targeted nanoparticle agents are developed to carry a large drug payload, and the need arises to accurately define site concentration of drug beyond that offered by simple predictions from standard multi-compartmental modeling of blood concentrations.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded through the National Institute of Health’s Bioengineering Research Partnership (R01 HL073646-03), the National Cancer Institute’s Siteman Cancer Center for Nanotechnology Excellence (U54 CA119342-02), and the Olin Fellowship for Women.

References

- 1.Jang GR, Harris RZ, Lau DT. Pharmacokinetics and its role in small molecule drug discovery research. Med Res Rev. 2001;21(5):382–396. doi: 10.1002/med.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lanza GM, Yu X, Winter PM, Abendschein DR, Karukstis KK, Scott MJ, Chinen LK, Fuhrhop RW, Scherrer DE, Wickline SA. Targeted antiproliferative drug delivery to vascular smooth muscle cells with a magnetic resonance imaging nanoparticle contrast agent: implications for rational therapy of restenosis. Circulation. 2002;106(22):2842–2847. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000044020.27990.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flacke S, Fischer S, Scott MJ, Fuhrhop RJ, Allen JS, McLean M, Winter P, Sicard GA, Gaffney PJ, Wickline SA, Lanza GM. Novel MRI contrast agent for molecular imaging of fibrin: implications for detecting vulnerable plaques. Circulation. 2001;104(11):1280–1285. doi: 10.1161/hc3601.094303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lanza GM, Wallace KD, Scott MJ, Cacheris WP, Abendschein DR, Christy DH, Sharkey AM, Miller JG, Gaffney PJ, Wickline SA. A novel site-targeted ultrasonic contrast agent with broad biomedical application. Circulation. 1996;94(12):3334–3340. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.12.3334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winter PM, Neubauer AM, Caruthers SD, Harris TD, Robertson JD, Williams TA, Schmieder AH, Hu G, Allen JS, Lacy EK, Zhang H, Wickline SA, Lanza GM. Endothelial alpha(v)beta3 integrin-targeted fumagillin nanoparticles inhibit angiogenesis in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26(9):2103–2109. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000235724.11299.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cornily JC, Hyafil F, Calcagno C, Briley-Saebo KC, Tunstead J, Aguinaldo JG, Mani V, Lorusso V, Cavagna FM, Fayad ZA. Evaluation of neovessels in atherosclerotic plaques of rabbits using an albumin-binding intravascular contrast agent and MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;27(6):1406–1411. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoshiga M, Alpers CE, Smith LL, Giachelli CM, Schwartz SM. Alpha-v beta-3 integrin expression in normal and atherosclerotic artery. Circ Res. 1995;77(6):1129–1135. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.6.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kerwin WS, Oikawa M, Yuan C, Jarvik GP, Hatsukami TS. MR imaging of adventitial vasa vasorum in carotid atherosclerosis. Magn Reson Med. 2008;59(3):507–514. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson SH, Herrmann J, Lerman LO, Holmes DR, Jr, Napoli C, Ritman EL, Lerman A. Simvastatin preserves the structure of coronary adventitial vasa vasorum in experimental hypercholesterolemia independent of lipid lowering. Circulation. 2002;105(4):415–418. doi: 10.1161/hc0402.104119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Winter PM, Morawski AM, Caruthers SD, Fuhrhop RW, Zhang H, Williams TA, Allen JS, Lacy EK, Robertson JD, Lanza GM, Wickline SA. Molecular imaging of angiogenesis in early-stage atherosclerosis with alpha(v)beta3-integrin-targeted nanoparticles. Circulation. 2003;108(18):2270–2274. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000093185.16083.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahrens ET, Rothbacher U, Jacobs RE, Fraser SE. A model for MRI contrast enhancement using T1 agents. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(15):8443–8448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morawski AM, Winter PM, Crowder KC, Caruthers SD, Fuhrhop RW, Scott MJ, Robertson JD, Abendschein DR, Lanza GM, Wickline SA. Targeted nanoparticles for quantitative imaging of sparse molecular epitopes with MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2004;51(3):480–486. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee L, Sharma S, Morgan B, Allegrini P, Schnell C, Brueggen J, Cozens R, Horsfield M, Guenther C, Steward WP, Drevs J, Lebwohl D, Wood J, McSheehy PM. Biomarkers for assessment of pharmacologic activity for a vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor inhibitor, PTK787/ZK 222584 (PTK/ZK): translation of biological activity in a mouse melanoma metastasis model to phase I studies in patients with advanced colorectal cancer with liver metastases. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2006;57(6):761–771. doi: 10.1007/s00280-005-0120-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muruganandham M, Lupu M, Dyke JP, Matei C, Linn M, Packman K, Kolinsky K, Higgins B, Koutcher JA. Preclinical evaluation of tumor microvascular response to a novel antiangiogenic/antitumor agent RO0281501 by dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI at 1. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5(8):1950–1957. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris TD, Kalogeropoulos S, Nguyen T, Liu S, Bartis J, Ellars C, Edwards S, Onthank D, Silva P, Yalamanchili P, Robinson S, Lazewatsky J, Barrett J, Bozarth J. Design, synthesis, and evaluation of radiolabeled integrin alpha v beta 3 receptor antagonists for tumor imaging and radiotherapy. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2003;18(4):627–641. doi: 10.1089/108497803322287727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meoli DF, Sadeghi MM, Krassilnikova S, Bourke BN, Giordano FJ, Dione DP, Su H, Edwards DS, Liu S, Harris TD, Madri JA, Zaret BL, Sinusas AJ. Noninvasive imaging of myocardial angiogenesis following experimental myocardial infarction. J Clin Invest. 2004;113(12):1684–1691. doi: 10.1172/JCI20352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sadeghi MM, Krassilnikova S, Zhang J, Gharaei AA, Fassaei HR, Esmailzadeh L, Kooshkabadi A, Edwards S, Yalamanchili P, Harris TD, Sinusas AJ, Zaret BL, Bender JR. Detection of injury-induced vascular remodeling by targeting activated alphavbeta3 integrin in vivo. Circulation. 2004;110(1):84–90. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000133319.84326.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.In den Kleef JJ, Cuppen JJ. RLSQ: T1, T2, and rho calculations, combining ratios and least squares. Magn Reson Med. 1987;5(6):513–524. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910050602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kolodgie FD, Katocs AS, Jr, Largis EE, Wrenn SM, Cornhill JF, Herderick EE, Lee SJ, Virmani R. Hypercholesterolemia in the rabbit induced by feeding graded amounts of low-level cholesterol. Methodological considerations regarding individual variability in response to dietary cholesterol and development of lesion type. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1996;16(12):1454–1464. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.16.12.1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flaim SF. Pharmacokinetics and side effects of perfluorocarbon-based blood substitutes. Artif Cells Blood Substit Immobil Biotechnol. 1994;22(4):1043–1054. doi: 10.3109/10731199409138801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Press WH, Teukolsky SA, Vetterling WT, Flannery BP. Numerical Recipes in C. Cambridge University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Winter PM, Caruthers SD, Yu X, Song S-K, Fuhrhop RW, Scott MJ, Chen J, Miller B, Bulte JWM, Gaffney PJ, Wickline SA, Lanza GM. Improved molecular imaging contrast agent for early detection of unstable atherosclerotic plaques. Magn Reson Med. 2003;50(2):411–416. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu G, Lijowski M, Zhang H, Partlow KC, Caruthers SD, Kiefer G, Gulyas G, Athey P, Scott MJ, Wickline SA, Lanza GM. Imaging of Vx-2 rabbit tumors with alpha(nu)beta3-integrin-targeted 111In nanoparticles. Int J Cancer. 2007;120(9):1951–1957. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kwon S, Ke S, Houston JP, Wang W, Wu Q, Li C, Sevick-Muraca EM. Imaging dose-dependent pharmacokinetics of an RGD-fluorescent dye conjugate targeted to alpha v beta 3 receptor expressed in Kaposi’s sarcoma. Mol Imaging. 2005;4(2):75–87. doi: 10.1162/15353500200505103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang X, Xiong Z, Wu Y, Cai W, Tseng JR, Gambhir SS, Chen X. Quantitative PET imaging of tumor integrin alphavbeta3 expression with 18F-FRGD2. J Nucl Med. 2006;47(1):113–121. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McGoron AJ, Pratt R, Zhang J, Shiferaw Y, Thomas S, Millard R. Perfluorocarbon distribution to liver, lung and spleen of emulsions of perfluorotributylamine (FTBA) in pigs and rats and perfluorooctyl bromide (PFOB) in rats and dogs by 19F NMR spectroscopy. Artif Cells Blood Substit Immobil Biotechnol. 1994;22(4):1243–1250. doi: 10.3109/10731199409138822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reickert C, Pranikoff T, Overbeck M, Kazerooni E, Massey K, Bartlett R, Hirschl R. The pulmonary and systemic distribution and elimination of perflubron from adult patients treated with partial liquid ventilation. Chest. 2001;119(2):515–522. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.2.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bruno R, Riva A, Hille D, Lebecq A, Thomas L. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of docetaxel: results of phase I and phase II trials. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1997;54(24 Suppl 2):S16–19. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/54.suppl_2.S16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harashima H, Tsuchihashi M, Iida S, Doi H, Kiwada H. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modeling of antitumor agents encapsulated into liposomes. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 1999;40(1–2):39–61. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(99)00039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Viglianti BL, Ponce AM, Michelich CR, Yu D, Abraham SA, Sanders L, Yarmolenko PS, Schroeder T, MacFall JR, Barboriak DP, Colvin OM, Bally MB, Dewhirst MW. Chemodosimetry of in vivo tumor liposomal drug concentration using MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2006;56(5):1011–1018. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]