Abstract

This study identified mechanisms through which child-mother attachment security at 36 months was associated with mother- and teacher-reported friendship quality at third grade. Data from a subsample of 1071 children (536 boys) participating in the NICHD SECCYD were utilized. Separate structural equation models were tested for mother and teacher reports of peer functioning. For both models, the total indirect effect between attachment security and friendship quality was significant. Tests of specific indirect effects indicated that attachment security was associated with friendship quality via greater mother-child affective mutuality and better language ability at 54 months, and fewer hostile attributions (teacher model only) and greater peer competence at first grade. The findings highlight interpersonal and intrapersonal mechanisms of attachment-friend linkages.

Establishing and maintaining close friendships is a central developmental task of middle childhood, yet the quality of children’s friendships varies widely (Hartup, 1996). Although not the only contributor to friendship quality, the intimate, dyadic nature of attachment relationships is posited to be especially germane to children’s close relationships, such as friendships, compared with more general indices of social adjustment (see Belsky & Cassidy, 1994; Sroufe & Fleeson, 1986; Thompson, 1998). In line with this view, child-mother attachment security has been related in theoretically expected ways to children’s friendship quality (e.g., Elicker, Englund, & Sroufe, 1992; McElwain, Cox, Burchinal & Macfie, 2003; McElwain & Volling, 2004; Youngblade & Belsky, 1992), and in a meta-analysis of attachment-peer associations, Schneider, Atkinson, and Tardiff (2001) reported a larger effect size for studies of children’s close friendships versus studies of children’s interactions with unfamiliar peers (also see Lieberman, Doyle & Markiewicz, 1999). We aimed to further this line of inquiry by assessing potential intervening mechanisms of attachment-friend linkages.

Our investigation was guided by attachment theory, in which Bowlby (1969/1982) proposed that children continuously construct “working models” of self, other, and relationships through repeated interactions with caregivers. The internal working model, in turn, mediates associations between early attachment relationships and later outcomes through the formation of expectations or rules for behavior (see Bretherton & Munholland, 1999) and the filtering of the individual’s attention and memory in ways that are consistent with his/her expectations for interpersonal interactions (see Main, 1995; Main, Kaplan, & Cassidy, 1985). Notably, patterns of verbal and nonverbal communication between the caregiver and child, especially about emotions, are considered central to the development and maintenance of working models of attachment (Bolwby, 1969/1982/1988; Bretherton, 1990; Kobak & Duemmler, 1994; Main et al., 1985). From birth, caregivers respond to their infant’s vocal and non-vocal cues, and these caregiver-infant exchanges—repeated over time—lay the foundation for nascent working models of self and other (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters & Wall, 1978). During the preschool years, the attachment relationship is transformed by the child’s burgeoning language and cognitive skills, and Thompson (2000) proposed that it is during this period of representational advance that working models of attachment may be especially influential in predicting child functioning. In light of these propositions, we assessed children’s hostile attribution biases and language ability as intervening mechanisms linking child-mother attachment security at 36 months and children’s friendship quality at grade 3. Furthermore, open emotional communication between mothers and children, which we refer to here as affective mutuality, was examined as an interpersonal process through which child-mother attachment security would be associated with intrapersonal processes (i.e., hostile attributions, language ability) and ultimately friendship quality.

Hostile Attribution Biases

Dodge and colleagues’ (Crick & Dodge, 1994; Dodge, Pettit, McClaskey, & Brown, 1986) model of social information processing (SIP) includes several steps (e.g., encoding and interpreting social cues, generating and evaluating potential responses) that are expected to influence an individual’s response to a social stimulus. We focus here on attributions of hostile intent when interpreting social cues because this SIP construct, in particular, parallels the notion of the internal working model as an interpretative filter (e.g., Main, 1995). The utility of hostile attributions as an intervening mechanism of attachment-friend linkages is also suggested by studies linking hostile attributions to a host of peer-related outcomes, including aggression (see Orobio de Castro, Veerman, Koops, Bosch, & Monshouwer, 2002), peer rejection (Feldman & Dodge, 1987), friendship quality and social competence (Webster-Stratton & Lindsay, 1999).

Importantly, the SIP model highlights “latent mental structures” as the individual’s scripts, schemata or cognitive heuristics of previous experiences that have been integrated into long-term memory and that guide processing of social stimuli (Crick & Dodge, 1994; Dodge & Schwartz, 1997). Reliance on latent mental structures, which is especially likely when social stimuli are ambiguous, allows for more efficient, schema-consistent processing of environmental cues, but may also lead to errors or distortions (Baldwin, 1992; Crick & Dodge, 1994). The SIP notion of latent mental structures echoes Bretherton and Munholland’s (1999) discussion of the internal working model as event schemas or scripts. Thus, the child’s internal working model (or latent mental structures), which emerges from repeated interactions with attachment figures, is expected to guide on-line interpretation of social stimuli. For instance, guided by a working model of the self as worthy of care and others as supportive and trustworthy, a child with a secure attachment history may make benign attributions about negative interpersonal events in which the intent of the other is ambiguous. In contrast, a child with an insecure attachment history, and corresponding working model of the self as unworthy and others as unresponsive, may be more likely to attribute hostile intentions to others. In other words, a child who has received repeated rejection and hostility from attachment figures may come to expect such treatment from others, even when situational cues do not merit such expectations.

Of the few studies investigating associations between attachment and hostile attribution biases, evidence has been mixed. Suess, Grossmann, and Sroufe (1992) reported that an insecure-avoidant infant-mother attachment was associated with attributions of negative peer intent at age five (but see Cassidy, Kirsh, Scolton, & Parke, 1996; Ziv, Oppenheim, & Sagi-Schwartz, 2004, for null findings), and Cassidy et al. (1996) found that attachment security during the early school years was concurrently related to more positive attributions of peer intent. Little is known about preschool attachment security as a predictor of hostile attribution biases. As highlighted by Crittenden (1990), working models move from reliance on procedural memories during infancy to integration of semantic memories during late toddlerhood. Unlike procedural memories, semantic memories are conscious, rely on language for encoding and recall, and are likely to be elicited when information is ambiguous. Because these developmental changes result in more complex and language-mediated working models, attachment security during the early preschool period may be particularly important for setting in motion attributional biases that, in turn, impact later functioning (see also Thompson, 2000).

Only one study, to our knowledge, has tested biases in social information processing as a mechanism of attachment-friend associations: Cassidy et al. (1996, see Study 2) examined a composite of peer representations measured via Dodge and Frame’s (1982) SIP task as a mediator of concurrent associations between child-mother attachment security and number of reciprocal friendships in the kindergarten or first-grade classroom. No evidence of mediation was found. Rather, attachment security and peer representations were each significant predictors of the outcome, but only when entered first in the model. The small sample and concurrent measurement of the predictor, mediator and outcome variables, may have hindered detection of mediation in the Cassidy et al. (1996) study. The current study addressed these limitations.

Language Ability

In highlighting the role of communicative processes for developing attachment relationships, attachment theorists have considered the bidirectional influence of attachment and language: the child’s emerging language skills are expected to transform his/her attachment relationships, and attachment relationships may also forecast the child’s competence in acquiring and using language (Bowlby, 1969/1982; Bretherton, 1990; Main et al., 1985). This latter possibility is further suggested by research underscoring the social foundations of language acquisition (e.g., see Tomasello, 1992), and the notion that, from an evolutionary standpoint, language may be rooted in vocal behaviors aimed at fulfilling relational goals (Locke, 2001). Although few researchers have investigated attachment security as an antecedent of language competence, van IJzendoorn, Dijkstra, and Bus (1995) conducted a meta-analytic review of seven studies and reported a substantial association (r = .28) between infant-mother attachment security and greater language ability. Moreover, examining data from the NICHD Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development (SECCYD), Belsky and Fearon (2002) found that secure infant-mother attachment was associated with language comprehension at 36 months, controlling for contextual risk. Language and attachment researchers alike have suggested that the child’s interactions with a sensitive, responsive caregiver may account, to some extent, for the better language abilities of children with a history of secure attachment (e.g., Cohen, 2001; Fish & Pinkerman, 2003; van IJzendoorn et al., 1995).

Language also underpins key processes of childhood friendship formation and maintenance, including establishing a common ground, constructing joint plans, coordinating play, and negotiating resolutions to conflict (Gottman, 1983; Howes, Droege, & Matheson, 1994; Parker & Gottman, 1989). Not surprisingly, then, language difficulties have been related to lower social competence and poorer quality friendships (see Farmer, 2006), whereas higher levels of expressive and receptive language abilities have been associated with more positive, cooperative peer interactions (e.g., Mendez, Fantuzzo, & Cicchetti, 2002) and more socially connected interactions with friends (e.g., Hebert-Myers, Guttentag, Swank, Smith, & Landry, 2006). Given the importance of verbal communication for children’s relationships with attachment figures and friends, we investigated child language ability as a second intervening mechanism.

Mother-Child Affective Mutuality

Affective mutuality (i.e., the balanced, free-flowing verbal and nonverbal exchange of emotions) is a core characteristic of secure attachment relationships. With the advent of language, open verbal communication about emotions has the potential to foster the child’s feelings of security, exploration of his/her inner world, and effectiveness in coping with negative emotions (Bowlby, 1988; Bretherton, 1990; Kobak & Duemmler, 1994; Main et al., 1985). In contrast, exchanges in which the attachment figure censures, negates, or distorts the child’s emotional experience are expected to have negative consequences for child well-being due to conflicting working models (e.g., what is experienced versus what is said), impoverished exploration of attachment-related thoughts and feelings, and difficulty integrating and updating working models of self and other. Accordingly, infant-mother attachment security has been associated longitudinally with more emotionally open and coherent mother-child communication, whereas a history of insecure attachment has been associated with communication that is rigid, restricted, and less coherent (e.g., Etzion-Carasso & Oppenheim, 2000; Main et al., 1985). Likewise, attachment security assessed during the preschool years has been related to more frequent, elaborative discourse about negative emotions during mother-child talk about past events (Farrar, Fasig, & Welch-Ross, 1997; Laible, 2004). Open emotional exchange between mothers and children, in turn, has been related to children’s higher levels of language and concept development (Pianta, Nimetz, & Bennett, 1997), greater social competence (Pianta et al., 1997), and more constructive coping strategies (Gentzler, Contreras-Grau, Kerns, & Weimer, 2005). In sum, mother-child affective mutuality may be an important interpersonal process through which attachment security is associated with intrapersonal competencies.

The Current Study

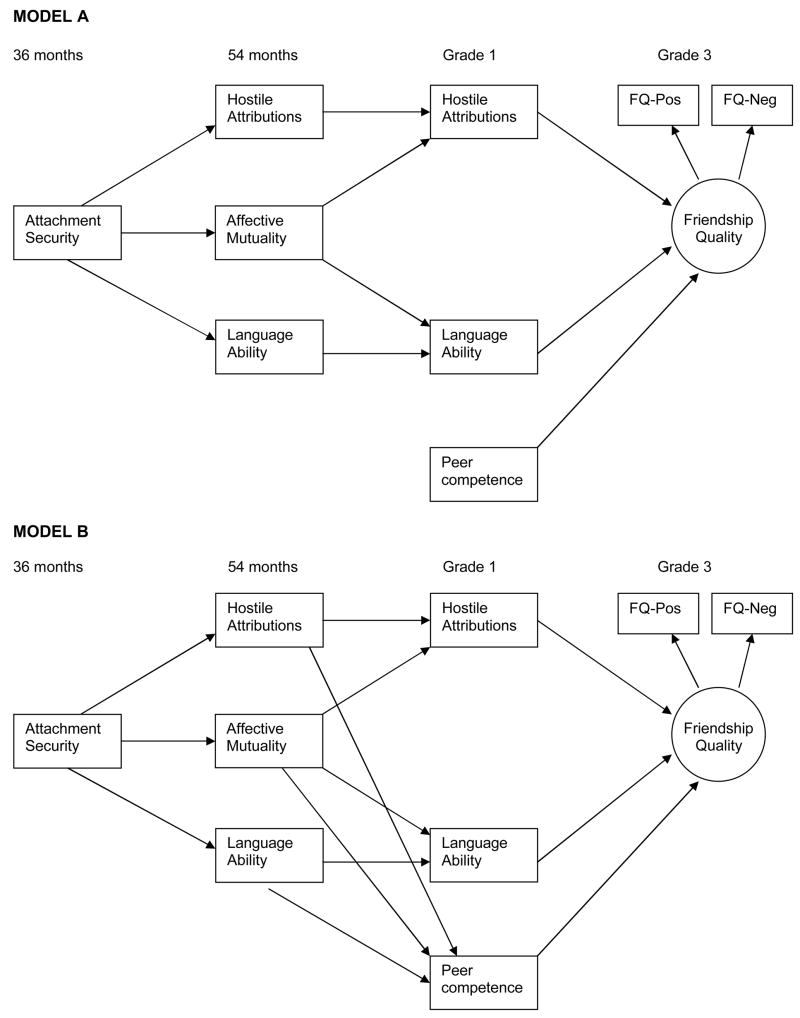

In assessing hostile attributions, language ability, and affective mutuality as mechanisms of attachment-friend linkages, we utilized data from the NICHD SECCYD. Model A in Figure 1 presents the hypothesized process model. This model posits chains of indirect pathways from child-mother attachment security and affective mutuality to hostile attributions and language ability, and from hostile attributions and language ability to friendship quality, which is conceptualized as high levels of positive features and low levels of negative features (Berndt, 2002). We expected that mother-child affective mutuality, as an interpersonal process, would influence friendship quality via intrapersonal processes (i.e., hostile attributions and language ability). Moreover, a secondary aim was to assess the degree to which 36-month attachment security was related to mechanisms in grade 1 via mother-child affective mutuality at 54 months.

Figure 1.

Model A: Children’s hostile attributions and language ability (54 months and Grade 1) and mother-child affective mutuality (54 months) as intervening mechanisms between child-mother attachment at 36 months and friendship quality at Grade 3. Model B: Peer competence at Grade 1 as an additional intervening mechanism.

The model is guided by strong theoretical assumptions regarding the causal nature and temporal ordering of constructs. In real time, the child-mother relationship is expected to precede and shape the child’s attributional biases and language abilities, which in turn are expected to precede and shape the child’s behavior and relationships with others. Further, the longitudinal design and repeated assessments of constructs permit an analysis of change over time, and this “replicative strategy” (Hoyle & Robinson, 2004) is considered optimal when testing intervening mechanisms in non-experimental studies (e.g., see Cole & Maxwell, 2003).

We also examined alternative indirect pathways in which peer competence in grade 1 was part of the chain of intervening mechanisms (see Model B in Figure 1). Fewer hostile attributions (see Crick & Dodge, 1994) and better language skills (see Farmer, 2006) have been associated with social adjustment, and these proposed mechanisms may be associated with friendship quality via peer competence. Further, during interactions with a sensitive, emotionally open caregiver, children may learn skills such as reciprocity and empathy (Elicker et al., 1992; Lieberman, 1977), which foster peer competence and, in turn, high-quality friendships. These alternative indirect paths were added to Model A to examine whether their addition significantly improved model fit.

Mother and teacher reports were used to assess peer competence in grade 1 and friendship quality in grade 3. Mother-teacher agreement on children’s social competence and peer functioning tends to be modest (see Renk & Phares, 2004), and discrepancies may be due, in part, to differences in child behavior and/or peer partners across home and school contexts. Hence, we tested the process model separately for mother and teacher reports, and we explored in follow-up analyses whether the strength of paths predicting peer competence and friendship quality differed by reporter.

Finally, child gender was examined as a moderator of the process model. “Moderated mediation” occurs when an intervening process varies as a function of a third variable (Muller, Judd, & Yzerbyt, 2005). We expected attachment security to relate to hostile attributions and language ability similarly for girls and boys, yet associations between these variables and friendship quality may differ by gender. Because girls tend to be more interpersonally orientated (e.g., Leaper, 1991), the model may be stronger for girls. On the other hand, research on hostile attributions has largely focused on boys, and it is unknown whether associations between hostile attributions and peer outcomes are stronger for boys (Orobio de Castro et al., 2002).

Method

Participants

Participants were a subsample of 1071 families drawn from the larger sample of 1364 families participating in the NICHD SECCYD. Families were recruited from hospitals located in or near 10 sites across the United States and were screened on numerous criteria (e.g., mothers under 18 were excluded from the study; all infants were healthy; see NICHD ECCRN, 1997, 1999, for further details). The subsample examined in the current report had complete data on mother and/or teacher reports of friendship quality in third grade.

The demographic characteristics for the subsample are presented in Table 1. On average, mothers were 28.49 years of age and had received 14.44 years of education, as reported by mothers when study children were one month of age. The income-to-needs ratio (averaged across data collected at 6, 15, 24, and 36 months) was 3.72, indicating that overall family income was, on average, 3.72 times that of the poverty level. In assessing maternal partner status, mothers were asked at 0, 6, 15, 24, and 36 months whether they were currently living with a partner or husband. For 76% of the families, a partner or spouse lived in the home at all time points. Fifty percent of the study children were male. With respect to child ethnicity, 78% were European American non-Hispanic, 11% were African American non-Hispanic, 6% were Hispanic, and 5% were another race or more than one race.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics on Demographic and Study Measures for Cases Included Versus Excluded

| Measures | Cases included | Cases excluded | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic measures | N | M (SD) | N | M (SD) |

| Maternal age | 1071 | 28.49 (5.58) | 293 | 26.74 (5.62) |

| Maternal education | 1071 | 14.44 (2.45) | 292 | 13.47 (2.59) |

| Income-to-needs ratio | 1063 | 3.72 (2.82) | 239 | 3.17 (3.03) |

| N | n (%) | N | n (%) | |

| Child sex (male) | 1071 | 536 (50%) | 293 | 169 (58%) |

| Child ethnicity (EA) | 1071 | 833 (78%) | 293 | 209 (71%) |

| Partner in home (yes) | 1068 | 807 (76%) | 274 | 185 (68%) |

| Study measures (time point, source) | N | M (SD) | N | M (SD) |

| Attachment security (36 months, observed) | 983 | 5.07 (1.70) | 157 | 4.78 (1.83) |

| Affective mutuality (54 months, observed) | 965 | 5.22 (1.25) | 75 | 4.77 (1.54) |

| Hostile attribution bias (54 months, child) | 938 | 1.70 (1.33) | 75 | 1.96 (1.31) |

| Hostile attribution bias (Grade 1, child) | 974 | 4.70 (2.05) | 51 | 4.53 (1.77) |

| Language ability (54 months, child) | 979 | 101.28 (14.61) | 81 | 98.07 (15.89) |

| Language ability (Grade 1, child) | 970 | 106.36 (16.09) | 50 | 105.16 (15.94) |

| Peer Competence (Grade 1, mother) | 980 | 15.67 (2.70) | 49 | 16.08 (2.67) |

| Peer Competence (Grade 1, teacher) | 956 | 15.31 (3.63) | 45 | 15.13 (3.22) |

| Positive friendship (Grade 3, mother) | 1008 | 3.22 (.34) | -- | |

| Negative friendship (Grade 3, mother) | 1008 | 1.97 (.48) | -- | |

| Positive friendship (Grade 3, teacher) | 955 | 3.15 (.39) | -- | |

| Negative friendship (Grade 3, teacher) | 960 | 1.89 (.53) | -- | |

Note. Cases were included in this report if complete data were available for mother- and/or teacher-reported friendship quality in grade 3 (N = 1071). For this reason, no excluded cases had data on the friendship outcomes. Data on maternal age and education were collected at 1 month. Data on income-to-needs ratio were collected at 6, 15, 24, and 36 months and combined across time points. Data on the presence of a partner in the home were collected at 0, 6, 15, 24, and 36 months and combined across time points. EA = European-American, non-Hispanic.

Overview of Procedure

Child-mother attachment was assessed using a modified Strange Situation procedure at 36 months, and mother-child affective mutuality was assessed from a series of mother-child interactive tasks at 54 months. For coding purposes, all videotapes for a given assessment were shipped to a central site, and different coding teams (who were blind to participant characteristics and other study results) assessed child-mother attachment security and affective mutuality. Child interviews were conducted at 54 months and grade 1 to assess hostile attributions and language ability. Mothers and teachers completed questionnaires assessing children’s peer competence at grade 1 and friendship quality at grade 3.

Mother-Child Relationship

Attachment security

At 36 months, the modified 17-minute Strange Situation procedure developed by Cassidy and Marvin (1992) was utilized to assess child-mother attachment security. This procedure took place in a laboratory playroom and consisted of 5 episodes: (a) a 3-minute warm-up period, (b) a 3-minute separation from mother, (c) a 3-minute reunion with mother, (d) a 5-minute separation, and (e) a second 3-minute reunion. Like the Ainsworth et al. (1978) system for coding infant attachment, the Cassidy and Marvin (1992) system emphasizes the child’s behavior during the reunion episodes, and children were classified into groups that parallel the infant classificatory system. In addition to classifying children as secure, avoidant, dependent/resistant, and controlling/disorganized, coders rated global security on a 9-point scale, ranging from 1 (highly insecure; e.g., highly avoidant, ambivalent or disorganized, or displaying a combination of strategies) to 9 (highly secure; e.g., highly at ease in initiating interaction, proximity, or contact; during reunion, child is calm, but pleased to see mother return). Three coders were trained and certified by Jude Cassidy. Prior to official coding, all coders assessed the ABCD classifications on a set of 21 test tapes and achieved at least 75% agreement with Dr. Cassidy. For official coding, interobserver reliability was assessed on 75% of the protocols, and disagreements were resolved by consensus. For the attachment classifications (ABCD), intercoder agreement (before consensus) was 75.7% (kappa = .58). For the global rating of security, intercoder agreement assessed via intraclass correlations (Winer, 1971) was .73.

An assessment of construct validity revealed consistent, albeit modest, associations with multiple indicators of maternal and child functioning (NICHD ECCRN, 2001). Moreover, post-hoc comparisons among the 4 attachment groups revealed differences between the secure group and the various insecure groups; no differences emerged among the insecure groups. Because this measure shows validity in distinguishing between secure and insecure attachment, only the continuous rating of security was utilized in this report. We examined the security continuum (versus binary score) because it provides a more fine-grained assessment of security.

Affective mutuality

During a laboratory visit at 54 months, mother-child interaction was videotaped during a 15-minute semi-structured observation. Mothers and children were presented with three activities: (a) completing a maze using an Etch-A-Sketch, (b) building a series of same-sized rectangular cube towers from variously shaped blocks, and (c) playing with a set of 6 hand puppets. The first two activities aimed to capture mother-child interaction during challenging situations in which the tasks were too difficult for the child to complete on his/her own, and the third activity aimed to capture mother-child play.

Videotapes of the mother-child interactions were coded for mother and child behaviors (see NICHD ECCRN, 2003). Given the emphasis on attachment security in this report, we examined the rating of dyadic affective mutuality, which was based on work by Pianta (1994). Affective mutuality was coded on a 7-point scale, ranging from 1(very low) to 7(very high), and captured the degree to which mothers and children engaged in open verbal and non-verbal exchange of emotions. High affective mutuality characterized dyads in which the mother acknowledged the child’s emotions and vice versa, the mother and child shared positive and negative experiences, and the child was free to express positive or negative feelings. In contrast, low affective mutuality characterized dyads in which the mother dampened the child’s expression of emotion, and mother-child exchanges, especially around negative emotions, were non-reciprocal or stifled. Approximately 23% of the tapes were randomly assigned to two coders. Interobserver reliability, assessed via intraclass correlations (Winer, 1971), was .87. Mother-child affective mutuality as measured here has been related more peer social skills and fewer behavior problems as reported by kindergarten teachers (Pianta et al., 1997).

Hostile Attribution Biases

54 months

Children’s hostile attribution biases were assessed during a 54-month laboratory visit. Children were presented with four stories (without pictures) involving a same-sex peer: (a) having a special toy taken by another child, (b) being hit by a ball, (c) being tripped, and (d) having grape juice spilled on the child. For each story, the intent of the peer was ambiguous, and the child was asked to choose from one of two attributions (e.g., “Did Tom hit you in the back by accident or did Tom want to hit you in the back?”). Children received a score of 1 for indicating that the peer’s action was intended and responses were summed across vignettes to form a hostile attribution score (α = .64). This measure, adapted from the cartoon version developed by Dodge et al. (1986), was modified specifically for use with four-year-old children (Feshbach, 1990). Hostile attributions assessed via this method have been associated with behavior problems, social competence, and child-friend interaction (Feshbach, 1990; Webster-Stratton & Lindsay, 1999).

First grade

During a laboratory visit at first grade, the Attribution Bias Interview was administered (Dodge et al., 1986). Children were presented with 8 cartoon drawings of peer provocations, in which the intent of the peer was ambiguous. For each situation, children were asked how they would interpret the peer’s intent (“Why do you think this happened?”) and how they would respond in such a situation (“What would you do?”). The first question assessed attributions of intent and was coded as don’t know, non-hostile, or hostile. A hostile attribution score was computed by summing hostile responses across stories (α = .64). This measure of hostile attributions has been associated with greater aggressive behavior and peer rejection (e.g., Dodge et al., 1986) and lower levels of prosocial behavior (Nelson & Crick, 1999).

Language Ability

The Woodcock-Johnson Psycho-Educational Battery-Revised (WJ-R) was administered to children during laboratory visits at 54 months and first grade. The WJ-R consists of two batteries: Tests of Cognitive Abilities (WJ-R COG) and Tests of Achievement (WJ-R ACH). The Picture Vocabulary Test (Test 6 of WJ-R COG) was examined for purposes of the current report. The first six items were presented in a multiple-choice format, in which children were asked to point to a named object. For subsequent items, children were asked to name pictured objects. The WJ-R has been normed on a nationally representative sample of 6,359 participants ranging in age from 24 months to 95 years and has shown good internal consistency and test-retest reliability (McGrew, Werder, & Woodcock, 1991). Standardized scores were examined in the analyses.

Peer Competence

The Social Skills Rating Scale (SSRS; Gresham & Elliott, 1990) was administered to mothers (Parent Form) and teachers (Teacher Form) at grade 1. The SSRS consists of 49 items assessing the frequency of social behaviors, and items were rated on a 3-point scale, ranging from 0 (never) to 2 (very often). A peer competence subscale was computed by summing 10 items that tapped children’s prosocial behavior toward peers and appropriate response to negative peer interactions (α = .74 and .85, mothers and teachers respectively). The SSRS has been normed on large samples and shows good construct validity and reliability (Gresham & Elliot, 1990).

Friendship Quality

The Quality of Child’s Friendship questionnaire was administered to mothers and teachers at third grade. This 20-item questionnaire, which assesses the child’s relationship with a best friend, was adapted from the Quality of Classroom Friends questionnaire (Clark & Ladd, 2000). Twelve items assessed positive interaction (α = .88 for both mothers and teachers), and 8 items assessed negative interaction (α = .85 and .86, mothers and teachers respectively). Items were rated on a 4-point scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Subscales were computed by averaging across items. Clark and Ladd (2000) reported that kindergarten children who had more connected parent-child relationships tended to have more harmonious relationships with their closest friend as rated by teachers.

Data Analytic Strategy

Mplus 5.0 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2007) was utilized to test the hypothesized models. Due to missing data (see Table 1 for ns), full-information maximum likelihood (FIML) was used to handle the missing data. FIML offers less biased estimates compared with other methods such as listwise deletion (Enders & Bandalos, 2001; Schafer & Graham, 2002). To avoid inflating predictor-outcome associations, however, only cases with complete data on mother- and/or teacher-reported friendship quality were used in the analyses. The comparative fit index (CFI) and root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) were examined to assess model fit. CFI values of .90 and above indicate an adequate fit, and values of .95 and above indicate a good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1995). RMSEA values less than .08 indicate adequate fit, and values less than .05 indicate a good fit (Browne & Cudeck, 1993). Maternal education and family income-to-needs ratio were included as covariates in all models presented below.

Models A and B depicted in Figure 1 were each estimated for mother and teacher reports of peer functioning (peer competence in grade 1 and friendship quality in grade 3). In testing Model B, 3 paths were added to Model A: 54-month hostile attributions, language ability, and mother-child affective mutuality to grade-1 peer competence. Chi-square values for the two models were compared to determine the more plausible model. Error variances for manifest variables within the 54-month and grade-1 time points were allowed to correlate, although for ease of presentation, the within-time covariances are not shown. For each model, the two subscales of the Quality of Child’s Friendship questionnaire were indicators of a latent variable of friendship quality. Item ratings for the negative interaction subscale were reflected and averaged so that higher scores indicated greater friendship quality. For the more plausible model (Model A versus B), total and specific indirect effects between child-mother attachment security at 36 months and friendship quality at grade 3 were tested in Mplus using the delta method (i.e., Sobel, 1982). Because a secondary objective was to assess whether preschool attachment was associated with the proposed mechanisms via open emotional communication of the mother-child dyad, we also examined indirect effects between 36-month attachment security and grade-1 mechanisms via mother-child affective mutuality at 54 months.

Two sets of follow-up analyses were conducted for the more plausible model. First, to examine child gender as a potential moderator of the indirect effects between attachment security and friendship quality, multi-group analyses were conducted. If a multi-group analysis indicated a significant gender effect, we assessed whether specific indirect effects between attachment security and friendship quality differed for boys and girls. Second, we examined mothers and teachers in the same model to compare path estimates predicting mother- versus teacher-reported peer competence in grade 1 and friendship quality in grade 3.

In assessing the proposed process model, it is important to distinguish between mediated and indirect effects. A mediated effect, which is considered a special case of indirect effects (Holmbeck, 1997; Preacher & Hayes, 2004), requires a significant association between the predictor and outcome (Baron & Kenny, 1986). An indirect effect, in contrast, does not necessitate significance of this path. Rather, a significant indirect effect implies the predictor has an effect on the outcome via the intervening variable (Kenny, Kashy, & Bolger, 1998). An examination of indirect effects may be especially important for developmental researchers examining processes that are distal in time (Shrout & Bolger, 2002). In this vein, we conducted a preliminary test of a “direct effects” model in which 36-month attachment security was the sole predictor of grade-3 friendship quality (controlling for maternal education and family income). These analyses indicated that for both mother- and teacher-reported friendship quality, the direct effect of 36-month attachment security on friendship quality was non-significant. Thus, in the analyses that proceed we refer to indirect rather than mediated effects. Although Baron and Kenny’s (1986) method for assessing mediation has been prevalent in the psychological literature, the importance of indirect effects, especially when examined across a long time span, should not be discounted because it is the predictor-mediator and mediator-outcome associations (versus the predictor-outcome association) that are central to testing hypotheses concerning intervening mechanisms (Kenny et al., 1998).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Cases included in the current report (N = 1071) were compared to cases excluded due to missing data on either mother- and/or teacher-reported friendship quality in third grade (see Table 1 for descriptive statistics). Comparisons indicated that, on average, mothers included in the subsample were older, t(1362) = 4.74, p < .001, and had received more years of education, t(1361) = 5.94, p < .001. Participating families had a higher income-to-needs ratio, t(1300) = 2.67, p < .01, and were more likely to have a partner living in the home, χ2 (1, N = 1342) = 7.32, p < .01. Further, children included in the subsample were more likely to be female, χ2 (1, N = 1364) = 5.37, p < .05, and European American, χ2 (1, N = 1364) = 5.30, p < .05. Comparisons on the study measures indicated that included cases had higher levels of child-mother attachment security at 36 months, t(1138) = 1.96, p = .05, and mother-child affective mutuality at 54 months, t(1038) = 2.94, p < .01 (see Table 1 for means). Cases included versus excluded did not differ significantly on hostile attributions or language ability at 54 months and first grade, nor mother- or teacher-reported peer competence at first grade.

For descriptive purposes, correlations among the study measures are presented in Table 2. Bivariate correlations are shown above the diagonal, and partial correlations controlling for maternal education and family income-to-needs ratio are shown below the diagonal.

Table 2.

Intercorrelations Among Study Measures

| Study measure: time point, source | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Attachment security: 36m, observed | -- | .24*** | −.06 | .17*** | −.09** | .18*** | .12*** | .14*** | .06 | −.02 | .06 | −.08* |

| 2. Affective mutuality: 54m, observed | .21*** | -- | −.10** | .22*** | −.14*** | .26*** | .17*** | .13*** | .15*** | −.17*** | .13*** | −.12*** |

| 3. Hostile attribution bias: 54m, child | −.04 | −.07* | -- | −.05 | .12*** | −.08* | −.02 | −.07* | −.09** | .05 | −.05 | .05 |

| 4. Language ability: 54m, child | .11*** | .13*** | .00 | -- | −.17*** | .67*** | .19*** | .17*** | .19*** | −.15*** | .11*** | −.13*** |

| 5. Hostile attribution bias: G1, child | −.08* | −.12*** | .11** | −.13*** | -- | −.15*** | −.12*** | −.13*** | −.10** | .09** | −.13*** | .14*** |

| 6. Language ability: G1, child | .13*** | .17*** | −.04 | .59*** | −.11*** | -- | .22*** | .18*** | .17*** | −.17*** | .11** | −.14*** |

| 7. Peer Competence: G1, mother | .10** | .13*** | .01 | .10** | −.10** | .14*** | -- | .29*** | .35*** | −.26*** | .18*** | −.15*** |

| 8. Peer Competence: G1, teacher | .12*** | .10** | −.05 | .11*** | −.12*** | .12*** | .26*** | -- | .24*** | −.21*** | .29*** | −.26*** |

| 9. Positive friendship: G3, mother | .02 | .09** | −.06 | .09** | −.08* | .08* | .31*** | .21*** | -- | −.66*** | .22*** | −.20*** |

| 10. Negative friendship: G3, mother | .01 | −.13*** | .03 | −.08* | .07* | −.10** | −.22*** | −.18*** | −.64*** | -- | −.20*** | .20*** |

| 11. Positive friendship: G3, teacher | .03 | .10** | −.04 | .04 | −.11*** | .04 | .15*** | .27*** | .19*** | −.17*** | -- | −.59*** |

| 12. Negative friendship: G3, teacher | −.06 | −.08* | .04 | −.07* | .12*** | −.08* | −.12*** | −.25*** | −.17*** | .18*** | −.58*** | -- |

Note. Bivariate correlations are reported above the diagonal and partial correlations controlling for maternal education and family income-to-needs ratio are reported below the diagonal. 36m = 36 months, 54m = 54 months, G1 = Grade 1, and G3 = Grade 3.

p < .05,

p ≤ .01,

p ≤ .001

Tests of the Process Model

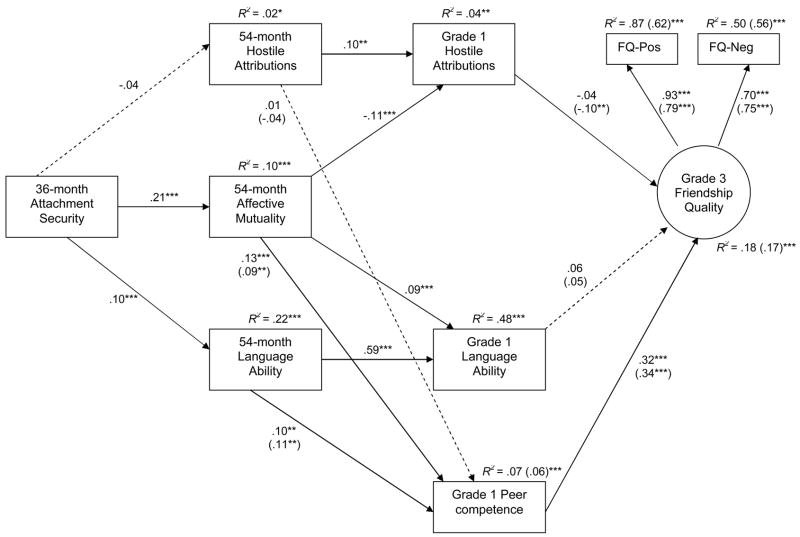

The hypothesized process model depicted in Model A (see Figure 1) was tested separately for mother and teacher reports. Chi-square tests were significant, which would be expected given the large sample size:χ2 (20) = 68.57, p < .001, and χ2 (20) = 54.65, p < .001, mother and teacher models, respectively. Fit indices for Model A indicated good fit: RMSEA = .048 and .040, CFI = .973 and .978, mother and teacher models respectively. Next, we tested Model B (see Figure 1) in which paths from 54-month hostile attributions, language ability and mother-child affective mutuality to grade-1 peer competence were added to Model A. Chi-square tests were again significant: χ2 (17) = 44.08, p < .001, and χ2 (17) = 34.52, p < .01, mother and teacher models, respectively. Fit indices for Model B indicated good fit for both mother and teacher models: RMSEA = .039 and .031, CFI = .985 and .989. Comparisons between Models A and B indicated that Model B showed significantly improved fit over Model A, χ2diff (3) = 24.49 and 20.13, ps < .001, mother and teacher models respectively. Because Model B was the more plausible model, we proceeded by examining the parameter estimates and testing indirect effects for Model B only. Standardized path estimates and R2 values for mother and teacher models are presented in Figure 2. For paths not involving mother or teacher reports (e.g., path from 36-month attachment security to 54-month hostile attributions), path estimates were identical or nearly identical (i.e., differed at the third decimal place) across the mother and teacher models. Thus, for those paths, only one estimate (applicable to both mother and teacher models) is presented in Figure 2. For paths to mother- and teacher-reported peer competence in grade 1 and friendship quality in grade 3, estimates for the mother model are presented outside parentheses, and estimates for the teacher model are presented inside parentheses (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Hostile attributions, language ability, affective mutuality, and peer competence as intervening mechanisms between child-mother attachment at 36 months and friendship quality at Grade 3. Models (N = 1071) were estimated separately for mother and teacher reports of peer functioning using full-information maximum likelihood. FQ-Pos = friendship quality, positive interaction subscale; FQ-Neg = friendship quality, negative interaction subscale. Item ratings for FQ-Neg were reflected and averaged so that higher scores indicated greater friendship quality. For those paths predicting peer competence in grade 1 and friendship quality in grade 3, standardized path estimates for mother reports are presented outside parentheses, and standardized path estimates for teacher reports are presented inside parentheses. For all other paths, estimates were identical across mother and teacher models, and only one estimate is shown. Paths represented by dotted lines were non-significant for both mother and teacher models. R2 estimates are presented for each endogenous variable. Maternal education and family income-to-needs ratio were included as covariates in the models. For ease of presentation, error terms, within-time covariances, and covariates are not shown. A table including these additional parameter estimates is available from the first author.

* p < .05, ** p < .01, ***p < .001.

The test of the total indirect effect (i.e., all specific indirect effects combined) from 36-month attachment security to grade-3 friendship quality was significant for mother (z = 3.72, p < .001) and teacher (z = 3.40, p = .001) models. Below we summarize results for each intrapersonal mechanism in turn, with a focus on the tests of specific indirect effects between (a) attachment security and grade-3 friendship quality, and (b) attachment security and grade-1 mechanisms via mother-child affective mutuality at 54 months.

Hostile attributions

As seen in Figure 2, child-mother attachment security at 36 months did not predict 54-month hostile attributions, although attachment security was indirectly related to grade-1 hostile attributions via mother-child affective mutuality at 54 months (z = −2.87 and z = −2.88, ps < .01, mother and teacher models respectively). Furthermore, grade-1 hostile attributions predicted lower friendship quality as reported by teachers in grade 3, and this specific indirect effect (36-month attachment security –> 54-month affective mutuality –> grade-1 hostile attributions –> grade-3 teacher-reported friendship quality) was significant (z = 1.98, p < .05). In contrast to the teacher model, grade-1 hostile attributions were not significantly related to mother-reported friendship quality in grade 3.

Language ability

Greater child-mother attachment security at 36 months was associated with greater language ability at 54 months, which in turn was associated with greater language ability at grade 1 (see Figure 2). Moreover, 36-month attachment security had an indirect effect on grade-1 language ability via mother-child affective mutuality at 54 months (z = 3.24 and z = 3.26, ps = .001, mother and teacher models respectively). Language ability in grade 1, however, was not associated with friendship quality in grade 3 as reported by mothers or teachers. Therefore, specific indirect effects of attachment security on friendship quality via grade-1 language ability were non-significant.

Peer competence

For both mother and teacher models, affective mutuality and language ability, but not hostile attributions, at 54 months were associated with grade-1 peer competence (see Figure 2). Further, indirect effects of attachment security on peer competence emerged via 54-month affective mutuality (zs = 3.26 and 2.48, ps < .001 and .05, mother- and teacher-reported peer competence, respectively) and 54-month language ability (zs = 2.14 and 2.26, ps < .05). Grade-1 peer competence, in turn, was associated with greater mother- and teacher-reported friendship quality in grade 3 (see Figure 2). Tests of the following indirect effects were significant: (a) 36-month attachment security –> 54-month affective mutuality –> grade-1 peer competence –> grade-3 friendship quality (zs = 3.09 and 2.37, ps < .01 and .05, mother and teacher models, respectively), and (b) 36-month attachment security –> 54-month language ability –> grade-1 peer competence –> grade-3 friendship quality (zs = 2.09 and 2.17, ps < .05).

Follow-Up Analyses

Child gender

We examined gender as a moderator of Model B. Multi-group analyses indicated that the unconstrained versus constrained model provided an improved fit for the mother model only, χ2diff (27) = 45.56, p < .05. Given the effect of child gender for the mother model, we proceeded to examine specific indirect pathways for boys and girls. Comparisons revealed that the following indirect effects were significant for boys but not girls: (a) attachment security –> affective mutuality –> peer competence, χ2diff (2) = 8.68, p < .05 (z = 3.34, p = .001, for boys; z = .85, ns, for girls), and (b) attachment security –> affective mutuality –> peer competence –>friendship quality, χ2diff (3) = 14.47, p < .01 (z = 2.73, p < .01, for boys; z = .85, ns, for girls). Inspection of the individual paths composing these indirect effects indicated that the path from mother-child affective mutuality to mother-reported peer competence was significant for boys only (β = .23, p < .001, for boys; β = .04, ns, for girls).

Mother-teacher comparisons

Next, mother and teacher reports of peer competence and friendship quality were examined in one model to assess whether the strength of the path estimates differed by reporter. For a given predictor-outcome association (e.g., grade-1 hostile attributions to grade-3 friendship quality), mother and teacher paths were constrained to be equal, and we assessed whether model fit showed a significant improvement when the paths were free to vary. Of the six comparisons made (3 paths to mother- versus teacher-reported peer competence in grade 1, and 3 paths to mother- versus teacher-reported friendship quality in grade 3), no significant differences emerged.

Discussion

Early attachment relationships are hypothesized to guide children’s later interactions with others, especially close others, via internal working models of the self, other, and relationships. Despite the centrality of this premise to attachment theory, little is known about mechanisms that may account for associations between child-mother attachment security and children’s subsequent close relationships with peers. To this end, we tested models of attachment-friend linkages utilizing data from the NICHD Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development. Our hypothesized model, guided by attachment theory, posited hostile attribution biases and language ability as intrapersonal mechanisms through which attachment security at 36 months would be associated with children’s friendship quality in third grade (see Model A, Figure 1). An alternative model considered peer competence in grade 1 as part of the chain of intervening mechanisms (see Model B, Figure 1). Models were tested separately for mother- and teacher-reported peer functioning (peer competence and friendship quality), and in each case, the second model (Model B) provided a better fit to the data. Because open emotional communication is viewed as integral to attachment security, a secondary aim was to examine mother-child affective mutuality at 54 months as an intervening interpersonal mechanism between 36-month attachment security and grade-1 intrapersonal mechanisms.

In accord with the notion of the internal working model as an interpretative filter (e.g., Main et al., 1985), we investigated children’s hostile attribution biases as a potential mechanism of attachment-friend linkages. This hypothesis received partial support. Namely, children who experienced greater attachment security with mothers at 36 months tended to engage in more open emotional communication with mothers at 54 months. Open emotional communication at 54 months, in turn, was associated with fewer hostile attributions at grade 1, which predicted greater teacher-reported friendship quality at grade 3. Notably, in addition to controlling for maternal education and family income, the association between 54-month affective mutuality and grade-1 hostile attributions controlled for 54-month hostile attributions, and the association between grade-1 hostile attributions and grade-3 friendship quality controlled for grade-1 language ability and peer competence. As such, our longitudinal, repeated-measures strategy provided a stringent test of hostile attributions as an intervening mechanism and lends confidence to the direction of effects posited by the process model. Moreover, these findings are consistent with prior evidence that child-mother attachment security is associated with fewer hostile attributions (Cassidy et al., 1996; Suess et al., 1992), and that hostile attributions are associated with problematic peer functioning (e.g., Dodge et al., 2003; Feldman & Dodge, 1987; Webster-Stratton & Lindsay, 1999). To our knowledge, the current study is the first to examine hostile attributions as a mechanism linking early child-mother attachment with later friendship quality. For the mother model, this indirect effect was non-significant, and specifically, grade-1 hostile attributions were not associated with mother-reported friendship quality, above and beyond language, peer competence and family demographics. Because vignettes assessing hostile attributions in first grade depicted peer provocations in a school context, grade-1 hostile attributions may be a more robust predictor of teacher-reported friendship quality. That being said, however, a mother-teacher comparison of this path was non-significant.

Surprisingly, attachment security was not associated with 54-month hostile attributions. Likewise, 54-month hostile attributions showed a weak association with grade-1 hostile attributions and no association with mother- or teacher-reported peer competence. Hostile attributions as assessed at 54 months have been associated in expected ways with teacher-reported social competence and observed child-friend interaction (Webster-Stratton & Lindsay, 1999), yet this prior work assessed bivariate associations only, and participants were predominantly male, higher risk, and slightly older (68 months, on average). This measure of hostile attribution biases may be less suitable for younger, lower-risk children. Also recall that the assessments of hostile attributions varied slightly at the 2 time points: at 54 months, no picture cues were provided and a forced-choice response format was used, whereas at first grade, line drawings accompanied the vignettes and an open-ended response format was used. Interestingly, in this respect, Cassidy et al. (1996, see Study 2) reported attachment-related differences when hostile attributions were assessed via an open-ended question (Why did the boy/girl…?), but not a forced-choice question (Do you think that the boy/girl… on purpose or… by accident?). Perhaps children are more likely to rely on their pre-existing knowledge base (i.e., latent mental structures) when asked an open-ended question about an actor’s intent. A forced-choice question, on the other hand, provides children with socially acceptable or even novel response options, and as such, may mask detection of meaningful individual differences.

A second intervening mechanism of interest was child language ability. For mother and teacher models, child-mother attachment security at 36 months predicted greater language ability at 54 months, which predicted greater peer competence at grade 1. Peer competence, in turn, predicted greater friendship quality at grade 3. This indirect effect provides support for language as an intervening mechanism of attachment-friend linkages, but one in which early language ability impacts later friendship quality via more general peer competence. That attachment security predicted language ability above and beyond family demographic variables adds to growing evidence of attachment as a communication system (Bolwby, 1988; Bretherton, 1990; Main et al., 1985) and context for language development (Belsky & Fearon, 2002; van IJzendoorn et al., 1995). The current results also converge with prior work suggesting the importance of language and communicative abilities for children’s social skills and friendship quality (e.g., Farmer, 2006; Gottman, 1983). In short, poor language skills during the preschool years may set children on trajectories of problematic relationships with peers. Notably, grade-1 language ability did not predict mother- or teacher-reported friendship quality above and beyond the other predictors in the model. It may be that language ability as assessed here was not a highly sensitive indicator of the types of language skills that are important for interactions with friends in middle childhood. Researchers should continue to elucidate the role of language as a mechanism of attachment-friend linkages, and adopting more fine-grained assessments of language skills may result in even stronger evidence of language as a critical process linking children’s family and peer relationships.

A secondary aim of this study was to assess whether 36-month attachment security was associated indirectly with grade-1 mechanisms via mother-child affective mutuality at 54 months. Results provided strong support for such processes. Namely, controlling for maternal education and family income, greater child-mother attachment security was associated with more open emotional exchange between 54-month-old children and their mothers. Open emotional exchange, in turn, was associated with fewer hostile attributions in grade 1 (controlling also for hostile attributions at 54 months), greater language ability in grade 1 (controlling also for language ability at 54 months), and greater peer competence in grade 1 (controlling also for hostile attributions and language ability at 54 months). Thus, open emotional communication may be a key interpersonal process through which early attachment security is associated with the development of social-cognitive, linguistic, and social-emotional competencies. We speculate that the “closed” communication style of insecure dyads (especially with regard to negative emotions and events) may result in a hostile attribution bias because the parent explicitly communicates hostile attributions to the child or because the parent does not communicate with the child, and the child is left to make sense of the negative emotions or events on his or her own. Similarly, low levels of affective mutuality of insecure dyads may result in fewer opportunities for children to develop language and socioemotional competencies that will be important for later positive interactions with peers.

Examination of child gender as a moderator of the process model indicated that, on the whole, intervening mechanisms operated similarly for boys and girls. For the mother model, however, the indirect effects from attachment security to grade-1 peer competence and grade-3 friendship quality via 54-month affective mutuality were significant for boys but not girls. Further probing indicated that the path from mother-child affective mutuality at 54 months to peer competence at grade 1 was significant for boys only. Boys, compared with girls, are often socialized to suppress expression of negative emotions (Brody, 1999). Open, mutual exchange of emotions with caregivers, therefore, may be particularly salient for young boys’ learning of social-emotional skills that foster harmonious, effective peer interactions.

Strengths of the current research include the large sample size, independent assessments of constructs, and inclusion of maternal education and family income as covariates. These factors yield increased power and reliability to detect indirect effects (see Frazier, Tix, & Barron, 2004). Most importantly, perhaps, the longitudinal design reflected the theoretically guided temporal ordering of constructs in the process model, and in some instances, the repeated assessment of constructs ruled out the possibility that longitudinal associations were due to stability of constructs across time. Thus, greater confidence in conclusions about the proposed direction of effects was achieved by adopting a “replicative strategy,” which permits an examination of change over time (see Cole & Maxwell, 2003; Hoyle & Robinson, 2004).

Nonetheless, several caveats should be noted. The subsample examined here, although relatively diverse, differed from cases excluded (due to missing data on the grade-3 friendship outcomes) on demographic and study measures. On the whole, children in the subsample tended to show higher functioning, and it is unclear whether the findings extend to more at-risk populations. Given the potential implications of this process model for intervention, inclusion of clinical populations, in particular, will be important. Also, the amount of variance explained was modest. Future studies should expand on the model presented here to examine additional mechanisms, including emotional regulatory processes that are likely to be shaped by attachment relationships (Cassidy, 1994), integrated into the processing of social information (Lemerise & Arsenio, 2000), and vital to peer functioning (Fabes & Eisenberg, 1992; Parker & Gottman, 1989). Moreover, because the quality of child-friend interaction is influenced by characteristics of both relationship partners (McElwain & Volling, 2002), it is likely that explained variance for friendship quality will increase when social-cognitive and language abilities of both children in the friendship dyad are considered. Finally, the proposed processes may emerge for some groups but not others. In this report, child gender was examined as a moderator, although overall, the process model functioned similarly for boys and girls. In considering other moderators, investigation of developmental period may be fruitful. Associations between social cognition and behavioral outcomes become stronger in later childhood and adolescence (e.g., Lansford et al., 2006), and the mechanisms examined here may become more pronounced later in development.

In sum, the current study extends prior work on attachment-friend associations by identifying chains of intervening mechanisms whereby child-mother attachment during the preschool period was associated with children’s relationships with friends during middle childhood. Our findings suggest the utility of investigating such processes at the intersection of social information processing, language, and mother-child communication about emotions.

Acknowledgments

The NICHD Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development is directed by a Steering Committee and supported by NICHD through a cooperative agreement (U10) that calls for a scientific collaboration between the grantees and the NICHD staff. We wish to express our appreciation to the principal investigators, site coordinators, and participants of the NICHD Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development. Correspondence concerning this manuscript may be addressed to the first author at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Department of Human and Community Development, 904 W. Nevada Street, Urbana, IL 61801. E-mail: mcelwn@illinois.edu.

Contributor Information

Nancy L. McElwain, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Cathryn Booth-LaForce, University of Washington.

Jennifer E. Lansford, Duke University

Xiaoying Wu, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

W. Justin Dyer, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

References

- Ainsworth MDS, Blehar MC, Waters E, Wall S. Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin MW. Relational schemas and the processing of social information. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:461–484. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Cassidy J. Attachment: Theory and evidence. In: Rutter M, Hays D, editors. Development through life. Oxford, England: Blackwell; 1994. pp. 373–402. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Fearon R. Infant-mother attachment security, contextual risk, and early development: A moderational analysis. Development and Psychopathology. 2002;14:293–310. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402002067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berndt TJ. Friendship quality and social development. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2002;11:7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Vol. 1 Attachment. New York: Basic Books; 1982. Original work published in 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. A secure base: Clinical applications of attachment theory. London: Routledge; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Bretherton I. Open communication and internal working models: Their role in the development of attachment relationships. In: Thompson RA, editor. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation: Vol.36. Socioemotional development. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press; 1990. pp. 57–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretherton I, Munholland KA. Internal working models in attachment relationships. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical implications. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 89–111. [Google Scholar]

- Brody L. Gender, emotion and the family. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J. Emotion regulation: Influences of attachment relationships. The development of emotion regulation: Biological and behavioral considerations. In: Fox NA, editor. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. Vol. 59. 1994. pp. 228–249. 2–3, Serial No. 240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J, Kirsh SJ, Scolton KL, Parke RD. Attachment and representations of peer relationships. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:892–904. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J, Marvin RS MacArthur Working Group on Attachment. Attachment organization in preschool children: Procedures and coding manual, Unpublished manual. University of Virginia; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Clark KE, Ladd GW. Connectedness and autonomy support in parent-child relationships: Links to children’s socioemotional orientation and peer relationships. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:485–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen NJ. Language impairment and psychopathology in infants, children, and adolescents. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Maxwell SE. Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:558–577. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Dodge KA. A reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in children’s social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;115:74–101. [Google Scholar]

- Crittenden PM. Internal representational models of attachment relationships. Infant Mental Health Journal. 1990;11:259–277. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Frame CL. Social cognitive biases and deficits in aggressive boys. Child Development. 1982;53:620–635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Lansford JE, Burks VS, Bates JE, Pettit GS, Fontaine R, Price JM. Peer rejection and social information-processing factors in the development of aggressive behavior problems in children. Child Development. 2003;74:374–393. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.7402004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Pettit GS, McClaskey CL, Brown MM. Social competence in children. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1986;51 2, Serial No. 213. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Schwartz D. Social information processing mechanisms in aggressive behavior. In: Stoff DM, Breiling J, editors. Handbook of antisocial behavior. New York: Wiley; 1997. pp. 171–180. [Google Scholar]

- Elicker J, Englund M, Sroufe LA. Predicting peer competence and peer relationships in childhood from early parent-child relationships. In: Parke RD, Ladd GW, editors. Family-peer relationships: Modes of linkage. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1992. pp. 77–106. [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, Bandalos DL. The relative performance of Full Information Maximum Likelihood estimations for missing data in structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling. 2001;8:430–457. [Google Scholar]

- Etzion-Carasso A, Oppenheim D. Open mother-preschooler communication. Relations with early secure attachment. Attachment and Human Development. 2000;2:347–370. doi: 10.1080/14616730010007914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabes RA, Eisenberg N. Young children’s coping with interpersonal anger. Child Development. 1992;63:116–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer M. Language and the development of social and emotional understanding. In: Clegg J, Ginsborg J, editors. Language and social disadvantage: Theory into practice. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2006. pp. 74–92. [Google Scholar]

- Farrar MJ, Fasig LG, Welch-Ross MK. Attachment and emotion in autobiographical memory development. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 1997;67:389–408. doi: 10.1006/jecp.1997.2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman E, Dodge KA. Social information processing and sociometric status: Sex, age, and situational effects. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1987;15:211–227. doi: 10.1007/BF00916350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feshbach L. Aggression-conduct problems, attention-deficits, hyperactivity, play, and social cognition in four-year-old boys (Doctoral Dissertation, University of Washington, 1989) Dissertation Abstracts International. 1990;50:5878. [Google Scholar]

- Fish M, Pinkerman B. Language skills in low-SES rural Appalachian children: Normative development and individual differences, infancy to preschool. Applied Developmental Psychology. 2003;23:539–565. [Google Scholar]

- Frazier PA, Tix AP, Barron KE. Testing moderator and mediator effects in counseling psychology research. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2004;51:115–134. [Google Scholar]

- Gentzler AL, Contreras-Grau JM, Kerns KA, Weimer BL. Parent-child emotional communication and children’s coping in middle childhood. Social Development. 2005;14:591–612. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM. How children become friends. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1983;48 3, Serial No. 201. [Google Scholar]

- Gresham FM, Elliott SN. The social skills rating system. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hartup WW. The company they keep: Friendships and their developmental significance. Child Development. 1996;67(1):1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert-Myers H, Guttentag CL, Swank PR, Smith KE, Landry SH. The importance of language, social, and behavioral skills across early and later childhood as predictors of social competence with peers. Applied Developmental Science. 2006;10:174–187. [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck GN. Toward terminological, conceptual, and statistical clarity in the study of mediators and moderators: Examples from the child-clinical and pediatric psychology literatures. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:599–610. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.4.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howes C, Droege K, Matheson CC. Play and communicative processes within long-and short-term friendship dyads. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1994;11:401–410. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle RH, Robinson JC. Mediated and moderated effects in social psychological research: Measurement, design, and analysis issues. In: Sansome C, Morf C, Panter AT, editors. The Sage handbook of methods in social psychology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2004. pp. 213–233. [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Evaluating model fit. In: Hoyle RH, editor. Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995. pp. 76–99. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny D, Kashy DA, Bolger N. Data analysis in social psychology. In: Gilbert DT, Fiske ST, Lindzey G, editors. The handbook of social psychology. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill; 1998. pp. 233–265. [Google Scholar]

- Kobak R, Duemmler S. Attachment and conversation: Toward a discourse analysis of adolescent and attachment security. In: Bartholomew K, Perlman D, editors. Advances in personal relationships: Vol. 5. Attachment processes in adulthood. London: Jessica Kingsley; 1994. pp. 121–149. [Google Scholar]

- Laible D. Mother-child discourse in two contexts: Links with child temperament, attachment security, and socioemotional competence. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:979–992. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.6.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Malone PS, Dodge KA, Crozier JC, Pettit GS, Bates JE. A 12-year prospective study of patterns of social information processing problems and externalizing behaviors. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34:709–718. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9057-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leaper C. Influence and involvement in children’s discourse: Age, gender, and partner effects. Child Development. 1991;62:797–811. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemerise EA, Arsenio WF. An integrated model of emotion processes and cognition in social information processing. Child Development. 2000;71:107–118. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman AF. Preschooler’s competence with a peer: Relations with attachment and peer experience. Child Development. 1977;48:1277–1287. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman M, Doyle AB, Markiewicz D. Developmental patterns in security of attachment to mother and father in late childhood and early adolescence: Associations with peer relations. Child Development. 1999;70(1):202–213. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke JL. First communion: The emergence of vocal relationships. Social Development. 2001;10:294–308. [Google Scholar]

- Main M. Recent studies in attachment. In: Goldberg S, Muir R, Kerr J, editors. Attachment theory: Social, developmental, and clinical perspectives. Hillsdale, NJ: Analytic Press; 1995. pp. 407–474. [Google Scholar]

- Main M, Kaplan N, Cassidy J. Security in infancy, childhood, and adulthood: A move to the level of representation. Growing points of attachment theory and research. In: Bretherton I, Waters E, editors. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. Vol. 50. 1985. pp. 66–104. 1–2, Serial No. 209. [Google Scholar]

- McElwain NL, Cox MJ, Burchinal MR, Macfie J. Differentiating among insecure mother-infant attachment classifications: A focus on child-friend interaction and exploration during solitary play at 36 months. Attachment and Human Development. 2003;5:136–164. doi: 10.1080/1461673031000108513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElwain NL, Volling BL. Relating individual control, social understanding, and gender to child-friend interaction: A relationships perspective. Social Development. 2002;11:362–385. [Google Scholar]

- McElwain NL, Volling BL. Attachment security and parental sensitivity during infancy: Associations with friendship quality and false belief understanding at age four. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2004;21:639–667. [Google Scholar]

- McGrew KS, Werder JK, Woodcock RW. WJ-R Technical Manual. Allen, TX: DLM; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Mendez JL, Fantuzzo J, Cicchetti D. Profiles of social competence among low-income African American preschool children. Child Development. 2002;73:1085–1100. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller D, Judd CM, Yzerbyt VY. When moderation is mediated and mediation is moderated. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;89:852–863. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.6.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 5. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén, & Muthén; 1998–2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DA, Crick NR. Rose-colored glasses: Examining the social information-processing of prosocial young adolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1999;19:17–38. [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. The effects of infant child care on infant-mother attachment security: Results of the NICHD Study of Early Child Care. Child Development. 1997;68:860–879. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb01967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. Child care and mother-child interaction in the first 3 years of life. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:1399–1413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. Child care and family predictors of preschool attachment and stability from infancy. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:847–862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. Early child care and mother-child interaction from 36 months through first grade. Infant Behavior and Development. 2003;26:345–370. [Google Scholar]

- Orobio de Castro B, Veerman JW, Koops W, Bosch JD, Monshouwer HJ. Hostile attribution of intent and aggressive behavior: A meta-analysis. Child Development. 2002;73:916–934. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker JG, Gottman JM. Social and emotional development in a relational context. In: Berndt TJ, Ladd GW, editors. Peer relationships in child development. New York: Wiley; 1989. pp. 95–131. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC. Rating scales for parent-child interaction in preschoolers. Unpublished coding manual. University of Virginia; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC, Nimetz SL, Bennett E. Mother-child relationships, teacher-child relationships, and school outcomes in preschool and kindergarten. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 1997;12:263–280. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers. 2004;36:717–731. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renk K, Phares V. Cross-informant ratings of social competence in children and adolescents. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;24:239–254. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider BH, Atkinson L, Tardiff C. Child-parent attachment and children’s peer relations: A quantitative review. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:86–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In: Leinhart S, editor. Sociological methodology. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1982. pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA, Fleeson J. Attachment and the construction of relationships. In: Hartup WW, Rubin Z, editors. Relationships and development. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1986. pp. 51–71. [Google Scholar]

- Suess G, Grossmann K, Sroufe L. Effects of infant attachment to mother and father on quality of adaptation in preschool: From dyadic to individual organisation of self. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1992;15:43–65. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA. Early sociopersonality development. In: Damon W, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3, Social, emotional, and personality development. 5. New York: Wiley; 1998. pp. 25–104. (Series Ed.), (Vol. Ed.) [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA. The legacy of early attachments. Child Development. 2000;71:145–152. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello M. The social bases of language acquisition. Social Development. 1992;1:67–87. [Google Scholar]

- van IJzendoorn MH, Dijkstra J, Bus AG. Attachment, intelligence, and language: A meta-analysis. Social Development. 1995;4:115–128. [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C, Lindsay DW. Social competence and conduct problems in young children: Issues in assessment. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1999;28:25–43. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2801_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winer BJ. Statistical principles in experimental design. 2. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Youngblade LM, Belsky J. Parent-child antecedents of 5-year-olds’ close friendships: A longitudinal analysis. Developmental Psychology. 1992;28:700–713. [Google Scholar]

- Ziv Y, Oppenheim D, Sagi-Schwartz A. Social information processing in middle childhood: Relations to infant-mother attachment. Attachment & Human Development. 2004;6:327–348. doi: 10.1080/14616730412331281511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]