Abstract

Matrix metalloproteinase-7 (MMP-7) is a small secreted proteolytic enzyme with broad substrate specificity. Its expression has been shown to be associated with tumor invasion, metastasis, and survival for a variety of cancers. We systematically evaluated single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in this gene in relation to breast cancer survival in a large follow-up study. This study included 1,079 breast cancer patients, recruited from 1996 to 1998, that were followed for a median of 7.1 years as part of the Shanghai Breast Cancer Study (SBCS). Eleven SNPs, including two known functional promoter SNPs, were analyzed using the Affymetrix Targeted Genotyping System. Associations with survival were evaluated by Cox proportional hazards regression and Kaplan-Meier functions. Statistically significant associations with disease-free (DFS) and/or overall survival (OS) were found for 5 polymorphisms; these associations were explained primarily by two SNPs (rs11568818 and rs11225297) that were in high linkage disequilibrium (LD) with the others. Patients homozygous for the rs11568818 rare allele (G) had a significantly worse prognosis (OS HR: 6.7, 95% CI: 2.4–18.6) than patients homozygous for the common allele (A). Significantly improved survival was seen for patients with the rs11225297 T allele, and this association occurred in a dose-response manner; patients with AT (OS HR: 0.7, 95% CI: 0.5–0.9) and TT (OS HR: 0.3, 95% CI: 0.1–0.8) fared better than patients with AA (p-value for trend: 0.001). Thus, common MMP-7 genetic polymorphisms were found to be significant determinants of survival among Chinese women with breast cancer.

Keywords: MMP-7, SNPs, breast cancer prognosis

Introduction

Matrix-metalloproteinases (MMPs) are zinc-dependent enzymes responsible for the degradation of components of the basal membrane and extracellular matrix (ECM). While necessary for normal processes such as tissue remodeling during development, MMPs also facilitate pathologic states, such as tumor invasion and metastasis. Although MMP-7 (matrilysin-1 or PUMP-1) is a minimal domain member of the MMP family, it has broad substrate specificity against ECM components such as elastin, proteoglycans, fibronectin, type IV collagen, and E-cadherin (1–3), as well as several non-ECM molecules including insulin-like growth factor binding proteins (IGFBPs), heparin-binding epidermal growth factor (HB-EGF), and Fas ligand (4–7). MMP-7 is primarily expressed in the epithelium of many organs, including the ductal and glandular epithelium of the breast (8). Overexpression of MMP-7 has been shown to occur in a wide variety of cancers, including tumors of the esophagus, stomach, colorectum, kidney, and breast (9–15). Further, MMP-7 expression has been shown to be associated with metastasis, disease progression, and decreased survival among esophageal, gastric, colorectal, pancreatic, renal, ovarian, and breast cancer patients (13–27).

Two functional single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have been identified in the promoter of MMP-7, rs11568818 (−181 A/G) and rs11568819 (−153 C/T), which have been shown to modulate transcription by influencing the binding of nuclear proteins (28). In transient transfection assays, the rare alleles together conferred an approximately 2- to 3-fold greater level of protein expression (28). Recent studies have begun to evaluate these common genetic variants in association with cancer survival. In a small study of 58 colorectal carcinoma patients, MMP-7 −181 G homozygosity was significantly associated with distant metastasis and lymph node involvement (29). Another study of 79 gastric carcinoma patients found that the −181 AG and GG genotypes were marginally associated with an increased risk of death (HR: 1.7, 95% CI: 1.0–3.1) (30). Recently, in a study of 221 breast cancer patients, Hughes et al. reported that Caucasians with rs11568818 GG tended to have increased nodal involvement and patients of mixed ethnicity with rs11568818 GG tended to be more likely to die (31). To the best of our knowledge, no large scale studies of common MMP-7 polymorphisms and cancer survival have yet been undertaken. In this study, we selected SNPs to comprehensively capture common variation throughout the MMP-7 gene, such that 11 polymorphisms, including the two promoter polymorphisms discussed above, were evaluated for their association with survival among 1,079 breast cancer patients who participated in the Shanghai Breast Cancer Study (SBCS).

Methods

Study population

Study subjects were participants of the Shanghai Breast Cancer Study, a population-based case-control study of women in Shanghai; detailed information on the study design and data collection procedures have been previously described (32–35). Cases were identified through a rapid case ascertainment system supplemented by the Shanghai Cancer Registry, which has virtually complete ascertainment of all incident cancer cases diagnosed among residents or urban Shanghai. Briefly, cases were diagnosed with breast cancer between August 1996 and March 1998, without a previous cancer diagnosis, and alive at the time of interview. A total of 1,602 eligible breast cancer cases were identified; of which 1,459 (91.1%) completed in-person interviews. Structured questionnaires were used to obtain detailed information on demographic, reproductive, and other factors. The mean time from cancer diagnosis to interview was only 66 days. Reasons for nonparticipation included refusal (N=109, 6.8%), death before interview (N=17, 1.1%), and inability to be located (N=17, 1.1%). Cancer diagnoses were confirmed by two senior pathologists. Clinical characteristics and patient treatment information was abstracted from medical records using a standard protocol. Patients were followed through July 2005 by active follow-up surveys, as well as death certificate linkage with the Vital Statistics Unit of the Shanghai Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Of the 1,459 breast cancer cases, 1,378 (94.4%) patients were directly contacted, or if deceased, contact was made with the next of kin (N=266, 19.3%). Status of the remaining 77 patients was determined by death registry linkage; 47 of these were found be deceased. The 30 patients remaining were assumed to be alive six months prior to the date of the death certificate linkage to allow for the possible delay of record entry. Four subjects had insufficient information for record linkage, and were considered to be lost to follow-up.

SNP selection

Polymorphisms were selected by searching Han Chinese data from the HapMap Project (36) using the Tagger program (37). Haplotype tagging SNPs (htSNPs) were selected to cover SNPs with an r2 of 0.90 or greater in the MMP-7 gene ± 5 kb that had a minor allele frequency (MAF) of at least 0.05. Known or potentially functional SNPs were forced into the htSNP selection process; SNP selection was finished in December of 2005. Using this haplotype tagging approach, twelve MMP-7 SNPs were selected, including two previously reported to affect promoter activity rs11568818(−181 A/G), and rs11568819 (−153 C/T) (28). Of the selected htSNPS, design of the assay for one failed (rs10502001), leaving 11 SNPs that were genotyped (rs660197, rs17098318, rs11568818, rs11568819, rs11225307, rs17352054, rs495041, rs10895304, rs7935378, rs12184413, and rs11225297).

DNA extraction and SNP genotyping

Of the 1,455 participants eligible to be included in the survival study, 1,193 (82.0%) donated a peripheral blood sample (10mL) which was processed within 6 hours of collection and then stored at −70°C. Genomic DNA was extracted from buffy coats using Puregene DNA Purification kits (Gentra Systems, Minneapolis, Minnesota) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Genotypes were assed with the Targeted Genotyping System (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA), using an advanced Molecular Inversion Probe (MIP) method (38). Briefly, 2 µg of genomic DNA was annealed to the assay panel overnight at 58°C. After annealing, the samples were split into 4 equal aliquots, each of which was gap filled with a different dNTP. These were ligated to produce padlocked probes, and digested with exonucleases to remove any remaining linear DNA. The padlocked probes were then specifically cleaved, causing them to invert; these inverted probes were used as the substrate for two rounds of PCR. During the second round of PCR, allele-specific labeling occurred. This was followed by cleavage of the tag from the amplified DNA. High resolution agarose gels were used for quality control (QC) assessment, and then samples were hybridized to the Affymetrix array. Arrays were then washed and stained; results were detected using an Affymetrix scanner according to manufacturer’s instructions. Blinded QC (N=39) and HapMap samples (N=12) were included with the genotyping; the average consistency rates for these samples was 99.6%. Laboratory staff was blinded to the case-control status of all samples.

Statistical analysis

Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) was evaluated by comparing observed and expected genotype frequencies (χ2 test). Associations between SNPs and patient or clinical characteristics were evaluated with the χ2 test. Survival time was defined as beginning at the time of cancer diagnosis, and ending at either relapse or death for progression-free or overall survival, respectively, or else censored at the date of last contact. Kaplan-Meier survival functions were constructed; differences between genotypes were evaluated by the log-rank test. Hazard ratios and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (HR, 95%CI) were determined by Cox proportional hazards regression. Covariates included age at diagnosis, stage of disease, steroid hormone receptor status, menopausal status, and patient treatment, including chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and tamoxifen. Indicator variables were used for patients with missing covariate data so that all patients were included in the regression models. The linkage disequilibrium (LD) structure of the polymorphisms was determined using Haploview (39). Haplotype frequencies and their associations with breast cancer survival were analyzed with HAPSTAT software (40). All other analysis was conducted with SAS v 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary NC), and all tests were based on two-tailed probability distributions. All p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Table 1 presents patient and clinicopathological characteristics of the 1,079 breast cancer cases genotyped for the MMP-7 gene. Their average age at diagnosis was 47.5 years (standard deviation 7.9), and 67.4% (N=727) were pre-menopausal. Over 93% of the cases were staged (N=1008, 93.4%), and of these, only 11% (N=111) had late stage disease (stage III or IV). Additionally, only 2.7% (N=29) of the cases had in situ disease carcinomas (data not shown). Information on steroid hormone receptor status was available for approximately 70% of the patients; of those with information, 63.2% (N=475) were estrogen receptor positive, and 64.3% (N=478) were progesterone receptor positive. The vast majority of the patients (N=1,073, 99.4%) had surgery (data not shown); additional treatments included chemotherapy (N=1,009, 94.7%), radiotherapy (N=403, 43.8%), and tamoxifen (N=684, 76.9%). The mean and median follow-up times were 6.4 and 7.1 years, respectively. Of the 1,079 MMP-7 genotyped breast cancer cases, 898 (83.2%) were reported to be ductal, and 181 (16.8%) were reported to have non-ductal (lobular, mucinous, papillary, and others) tumors (data not shown).

Table 1.

Patient and Clinicopathological Characteristics of 1,079 Breast Cancer Cases with MMP-7 Genotypes

| Mean (standard error) / N (%)* |

|

|---|---|

| Age at Diagnosis, years | 47.5 (7.9) |

| Premenopausal | 727 (67.4) |

| TNM Stage of Disease | |

| 0–I | 269 (24.9) |

| IIa | 389 (36.1) |

| IIb | 239 (22.2) |

| III–IV | 111 (10.3) |

| Unknown | 71 (6.6) |

| Estrogen Receptor Status | |

| Positive | 475 (44.0) |

| Negative | 277 (25.7) |

| Unknown | 327 (30.3) |

| Progesterone Receptor Status | |

| Positive | 478 (44.3) |

| Negative | 265 (24.6) |

| Unknown | 336 (31.1) |

| Chemotherapy | |

| Yes | 1009 (93.5) |

| No | 57 (5.3) |

| Unknown | 13 (1.2) |

| Radiotherapy | |

| Yes | 403 (37.4) |

| No | 518 (48.0) |

| Unknown | 158 (14.6) |

| Tamoxifen | |

| Yes | 684 (63.4) |

| No | 205 (19.0) |

| Unknown | 190 (17.6) |

| Disease-Free Survival Time, years | 5.9 (2.3) |

| Overall Survival Time, years | 6.4 (1.8) |

Column percents may not sum to 100 due to rounding error.

Descriptive information for the 11 MMP-7 SNPs is presented in Table 2. One SNP, rs11568819 (−153 C/T), was found not to be polymorphic in this population. None of the genotype distributions deviated from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. Further, none of the SNPs were found to be significantly associated with patients’s age, stage of disease, menopausal status, or hormone receptor status (data not shown).

Table 2.

MMP-7 SNP Information and Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE) Tests among 1,079 Breast Cancer Cases

| gene | Refered to in | Major/Minor | Genotype Frequency (%)* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP | region | Literature | Allele | AA 1 | AB 1 | BB 1 | HWE p-value |

| rs880197 | promoter | A/T | 38.7 | 47.8 | 13.6 | 0.521 | |

| rs17098318 | promoter | G/A | 82.9 | 16.7 | 0.4 | 0.108 | |

| rs11568818 | promoter | −181 A/G | A/G | 82.7 | 16.9 | 0.5 | 0.184 |

| rs11568819 | promoter | −153 C/T | C/T | 99.9 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.988 |

| rs11225307 | intron #3 | A/G | 56.7 | 36.9 | 6.4 | 0.684 | |

| rs17352054 | intron #5 | A/C | 77.9 | 20.6 | 1.5 | 0.758 | |

| rs495041 | 3′ UTR | C/T | 25.6 | 51.0 | 25.4 | 0.515 | |

| rs10895304 | 3′ UTR | A/G | 53.4 | 39.7 | 7.0 | 0.709 | |

| rs7935378 | 3′ UTR | T/C | 54.7 | 38.9 | 6.4 | 0.637 | |

| rs12184413 | 3′ UTR | C/T | 54.3 | 40.3 | 5.5 | 0.062 | |

| rs11225297 | 3′ UTR | A/T | 66.8 | 29.8 | 3.3 | 0.995 | |

Among breast cancer cases genotyped

AA refers to major allele homozygotes, BB refers to minor allele homozygotes, and AB refers to heterozygotes

Table 3 shows the associations of the MMP-7 polymorphisms with disease-free and overall survival. Estimates of association are shown without and with adjustment for age at diagnosis, stage of disease, hormone receptor status, menopausal status, and treatment, (chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and tamoxifen). Two SNPs, rs17098318 and rs11568818, were strongly and significantly associated with increased hazards of death in a recessive fashion. While only a small number of patients were homozygous for the variant allele of rs11568818 (N=5) which had been previously shown to be associated with increased MMP-7 expression (28), these patients had an approximate 7-fold elevated risk of death (HR: 6.7, 95% CI: 2.4–18.6) compared to those with the common genotype. A similar association was found for rs17098318. Four other SNPs, rs11225307, rs17352054, rs12184413, and rs11225297, were significantly or marginally associated with reduced hazards of death. Two of these, rs12184413 and rs11225297, showed a dose-response association for both disease-free and overall survival. Patients with rs12184413 CT had a reduced hazard of death (HR: 0.8, 95 % CI: 0.6–1.1) compared to those with CC, while TT individuals were significantly less likely to die (HR: 0.4, 95% CI: 0.2–0.9), p-value for trend: 0.016. Similarly, patients with rs11225297 AT had a reduced hazard of death compared to AA individuals (HR: 0.7, 95% CI: 0.5–0.9), and patients TT homozygous had the best survival (HR: 0.3, 95% CI: 0.1–0.8), p-value for trend: 0.001. All Kaplan-Meier survival functions for the effects of individual SNPs (data not shown) were in agreement with results from proportional hazards regression.

Table 3.

MMP-7 SNPs and Survival among 1,079 Breast Cancer Cases

| SNP |

Disease Free Survival HR (95% CI) |

Overall Survival HR (95% CI) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | genotype | Cases | Events | Unadjusted | Adjusted* | Cases | Events | Unadjusted | Adjusted* |

| rs880197 | A/A | 407 | 108 | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | 416 | 86 | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) |

| A/T | 498 | 141 | 1.1 (0.8–1.4) | 1.1 (0.8–1.4) | 514 | 108 | 1.0 (0.8–1.3) | 1.0 (0.8–1.4) | |

| TT | 142 | 43 | 1.2 (0.8–1.7) | 1.3 (0.9–1.9) | 146 | 38 | 1.3 (0.9–1.9) | 1.4 (1.0–2.1) | |

| p-value** | 0.387 | 0.141 | 0.260 | 0.135 | |||||

| rs17098318 | G/G | 871 | 239 | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | 894 | 189 | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) |

| G/A | 174 | 50 | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) | 1.1 (0.8–1.6) | 180 | 40 | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) | 1.1 (0.8–1.6) | |

| A/A | 4 | 3 | 4.4 (1.4–13.8) | 4.2 (1.3–13.4) | 4 | 3 | 5.8 (1.8–18.1) | 7.0 (2.2–22.8) | |

| p-value** | 0.227 | 0.144 | 0.217 | 0.155 | |||||

| rs11568818 | A/A | 869 | 238 | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | 892 | 188 | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) |

| A/G | 176 | 50 | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) | 182 | 40 | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) | |

| G/G | 5 | 4 | 5.5 (2.1–14.8) | 5.2 (1.9–14.4) | 5 | 4 | 5.8 (2.1–15.0) | 6.7 (2.4–18.6) | |

| p-value** | 0.166 | 0.111 | 0.157 | 0.120 | |||||

| rs11225307 | A/A | 592 | 172 | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | 610 | 140 | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) |

| A/G | 389 | 106 | 0.9 (0.7–1.2) | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 397 | 78 | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | 0.9 (0.7–1.2) | |

| G/G | 66 | 14 | 0.7 (0.4–1.2) | 0.5 (0.3–0.9) | 69 | 14 | 0.9 (0.5–1.5) | 0.6 (0.3–1.1) | |

| p-value** | 0.173 | 0.022 | 0.249 | 0.079 | |||||

| rs17352054 | A/A | 818 | 234 | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | 847 | 187 | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) |

| A/C | 216 | 55 | 0.9 (0.6–1.2) | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | 222 | 42 | 0.8 (0.6–1.2) | 0.8 (0.6–1.2) | |

| C/C | 16 | 3 | 0.6 (0.2–1.8) | 0.4 (0.1–1.2) | 16 | 3 | 0.8 (0.3–2.4) | 0.5 (0.1–1.4) | |

| p-value** | 0.198 | 0.057 | 0.249 | 0.110 | |||||

| rs495041 | C/C | 268 | 72 | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | 274 | 57 | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) |

| C/T | 536 | 162 | 1.3 (1.0–1.8) | 1.3 (1.0–1.8) | 549 | 131 | 1.4 (1.0–2.0) | 1.4 (1.0–1.9) | |

| T/T | 244 | 58 | 1.1 (0.8–1.6) | 1.2 (0.9–1.7) | 254 | 44 | 1.2 (0.8–1.8) | 1.4 (0.9–2.0) | |

| p-value** | 0.540 | 0.279 | 0.399 | 0.147 | |||||

| rs10895304 | A/A | 558 | 158 | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | 576 | 132 | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) |

| A/G | 420 | 115 | 1.0 (0.7–1.2) | 0.9 (0.7–1.2) | 428 | 85 | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | |

| G/G | 72 | 19 | 0.9 (0.6–1.5) | 1.2 (0.7–1.9) | 75 | 15 | 0.9 (0.5–1.5) | 1.1 (0.7–1.9) | |

| p-value** | 0.958 | 0.954 | 0.260 | 0.534 | |||||

| rs7935378 | T/T | 562 | 159 | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | 581 | 133 | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) |

| T/C | 405 | 105 | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 413 | 78 | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | |

| C/C | 66 | 19 | 1.0 (0.6–1.6) | 1.3 (0.8–2.1) | 68 | 15 | 0.9 (0.6–1.6) | 1.2 (0.7–2.1) | |

| p-value** | 0.609 | 0.891 | 0.270 | 0.600 | |||||

| rs12184413 | C/C | 572 | 167 | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | 585 | 133 | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) |

| C/T | 421 | 114 | 0.9 (0.7–1.2) | 0.8 (0.6–1.0) | 434 | 91 | 0.9 (0.7–1.2) | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | |

| T/T | 56 | 11 | 0.6 (0.3–1.1) | 0.5 (0.3–0.9) | 59 | 8 | 0.6 (0.3–1.1) | 0.4 (0.2–0.9) | |

| p-value** | 0.142 | 0.009 | 0.148 | 0.016 | |||||

| rs11225297 | A/A | 708 | 205 | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | 721 | 169 | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) |

| A/T | 307 | 81 | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | 322 | 58 | 0.7 (0.6–1.0) | 0.7 (0.5–0.9) | |

| T/T | 35 | 6 | 0.5 (0.2–1.2) | 0.4 (0.2–0.8) | 36 | 5 | 0.6 (0.2–1.3) | 0.3 (0.1–0.8) | |

| p-value** | 0.099 | 0.007 | 0.024 | 0.001 | |||||

Adjusted for age, disease stage, ER, PR, menopausal status, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and tamoxifen treatment

p-value for trend

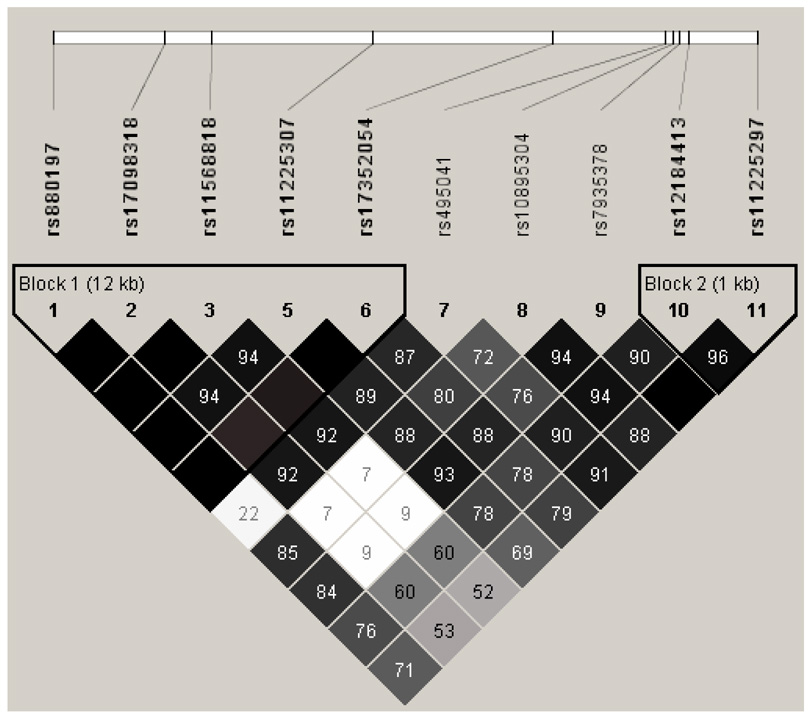

Haplotypes of the MMP-7 polymorphisms were constructed and analyzed. The LD structure of the polymorphisms among the 1,079 breast cancer cases revealed two haplotype blocks (Figure 1). Block 1 included all three promoter SNPs, as well as two intronic SNPs, and yielded five common haplotypes that included 99.8% of the study population (Table 4). One haplotype (H5: AAGAA), comprising 8.7% of the study population, included the rare alleles for both rs17098318 and rs11568818, and was associated with a significantly increased risk of death (HR: 4.4, 95% CI: 1.1–17.0) in a recessive fashion. These two SNPs, rs17098318 and rs11568818, were found to always segregate together (D′=1.0, r2=0.97). Three SNPs were in the region between Blocks 1 and 2, and together yielded three common haplotypes that included 94.2% of the study population. One haplotype (H2: CAT) consisted of all three common alleles, and was marginally associated with an increased hazard in recessive models (HR: 1.5, 95% CI: 1.0–2.3). Finally, block 2 consisted of two 3′ FR SNPs (rs12184413, and rs11225297) and yielded three common haplotypes covering 99.5% of the study population. One haplotype (H2: TT) included the variant alleles for both SNPs, and included 17.8% of the study population; this haplotype was associated with a significantly reduced risk of death (HR: 0.7, 95% CI: 0.6–1.0) in an additive model (p= 0.027).

Figure 1. LD Structure of MMP-7 SNPs among 1,079 Chinese Breast Cancer Cases.

Values shown are D′, blank cells indicate that D′=1. Blocks were defined by the methods of Gabriel et al., 2002.

Table 4.

Haplotype Analysis of MMP-7 SNPs and Survival among 1,079 Breast Cancer Patients

| Additive Model |

Recessive Model |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haplotype |

Frequency |

HR* |

95% CI* |

p-value |

HR* |

95% CI* |

p-value |

|

MMP-7 Block 1: rs880197, rs17098318, rs11568818, rs11225307, and rs17352054 | |||||||

| H1: TGAAA | 37.5 | 1.0 | reference | 1.0 | reference | ||

| H2: AGAAA | 28.8 | 0.9 | 0.7–1.1 | 0.199 | 1.0 | 0.6–1.6 | 0.884 |

| H3: AGAGA | 13.1 | 0.9 | 0.7–1.2 | 0.430 | 0.2 | 0.0–1.2 | 0.082 |

| H4: AGAGC | 11.7 | 0.7 | 0.5–1.0 | 0.069 | 0.5 | 0.2–1.8 | 0.326 |

| H5: AAGAA | 8.7 | 1.1 | 0.8–1.5 | 0.671 | 4.4 | 1.1–17.0 | 0.035 |

|

MMP-7 SNPs in between Blocks 1 and Blocks 2: rs495041, rs10895304, and rs7935378 | |||||||

| H1: TAT | 45.2 | 1.0 | reference | 1.0 | reference | ||

| H2: CAT | 27.0 | 1.2 | 0.9–1.5 | 0.166 | 1.5 | 1.0–2.3 | 0.053 |

| H3: CGC | 22.0 | 0.9 | 0.7–1.2 | 0.673 | 1.0 | 0.5–1.9 | 0.964 |

|

MMP-7 Block 2: rs12184413, and rs11225297 | |||||||

| H1: CA | 73.9 | 1.0 | reference | 1.0 | reference | ||

| H2: TT | 17.8 | 0.7 | 0.6–1.0 | 0.027 | 0.5 | 0.2–1.2 | 0.123 |

| H3: TA | 7.8 | 1.1 | 0.7–1.5 | 0.774 | NA1 | NA1 | NA1 |

|

MMP-7: Minimal SNPs to define risk: rs11568818 and rs11225297 | |||||||

| H1: AA | 73.6 | 1.0 | reference | 1.0 | reference | ||

| H2: AT | 17.5 | 0.7 | 0.6–1.0 | 0.025 | 0.6 | 0.2–1.4 | 0.215 |

| H3: GA | 8.1 | 1.2 | 0.9–1.7 | 0.186 | 5.3 | 1.4–19.6 | 0.013 |

Estimates adjusted for age at diagnosis and stage of disease

Estimate unstable due to small counts

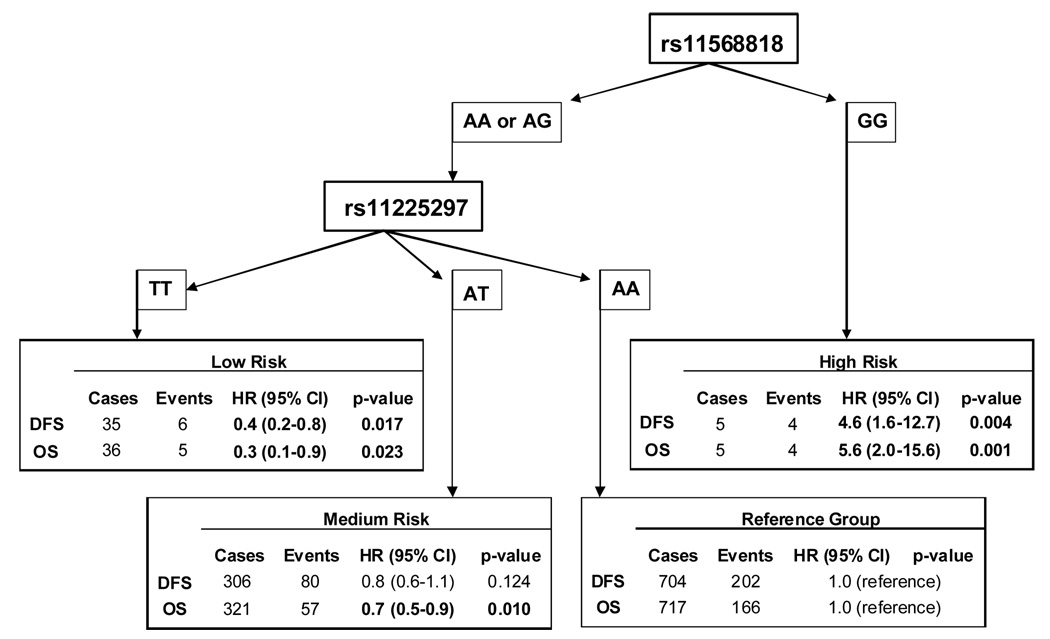

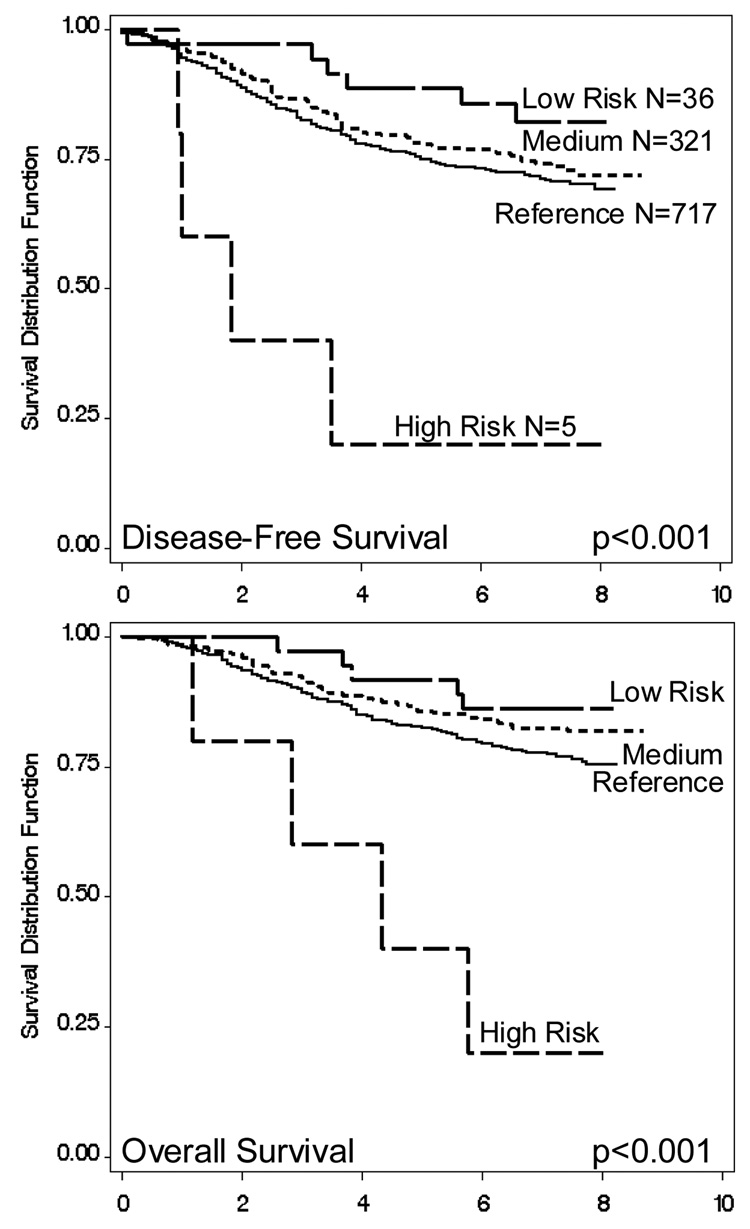

Further analysis was conducted to determine the minimal number of polymorphisms that defined the patients’ prognosis. As rs17098318 and rs11568818 provided identical information, only rs11568818 was included since it had previously been shown to have functional importance (16). Also in Block 1, both haplotypes with rs11225307 G tended to have decreased risk, so this SNP was considered. The three SNPs in between blocks 1 and 2 were also considered as one haplotype tended to have increased risk. Block 2 haplotype analysis indicated that rs11225297 defined risk better than rs12184413, so this SNP was also chosen. These six polymorphisms were then used to construct haplotypes and their associated hazards (data not shown). One haplotype had the G allele for rs11568818, and was associated with a significantly increased risk in a recessive fashion; similarly, only one haplotype had the rare allele T for rs11225297 and was associated with decreased hazard in a dose-response manner (data not shown). When only these two SNPs were included in the analysis, three haplotypes resulted, covering 99.2% of the study population. Compared to the reference group (H1: AA) with both common alleles, the second haplotype (H2: AT) had the rare allele for rs11225297 and was associated with a significantly reduced hazard of death (HR: 0.7, 95% CI: 0.6–1.0) in a dose-response manner (p=0.025). The third haplotype (H3: GA) had the rare allele for rs11225297 and was associated with a significantly worse prognosis (HR: 5.3, 95% CI: 1.4–19.6) in a recessive model (p=0.013). The hazards associated with MMP-7 polymorphisms for these breast cancer cases could thus be summarized by two SNPs, rs11568818 and rs11225297 (Figure 2). These two SNPs were used to categorize the women, by first, whether rs11568818 GG was present, and second, by how many rs11225297 T alleles were present. No women were found to have both the rs11568818 GG and rs11225297 TT genotypes. Four groups of patients resulted; the reference category had rs11568818 AA or AG and rs11225297 AA, and included 717 patients. The high risk group were those with rs11568818 GG, this small group of patients had a significantly worse prognosis (DFS HR: 4.6, 95% CI: 1.6–12.7; OS HR: 5.6, 95% CI: 2.0–15.6). The medium risk category included 321 patients who had rs11568818 AA or AG and rs11225297 AT; these women had decreased disease-free and overall survival (DFS HR: 0.8, 95% CI: 0.6–1.1; OS HR: 0.7, 95% CI: 0.5–0.9). Finally, 36 women were categorized as low risk; patients with rs11568818 AA or AG and rs11225297 TT had a significantly better prognosis (DFS HR: 0.4, 95% CI: 0.2–0.8; OS HR: 0.3, 95% CI: 0.1–0.9). These results are reflected in the Kaplan-Meier survival functions of the four patient groups, as shown in Figure 3. These associations remained unchanged when analyses were limited to only ductal cancers, or adjusted for non-ductal tumors in the regression models.

Figure 2. MMP-7 rs11568818 and rs11225297 Genotype Combinations and associated Hazard Estimates.

MMP-7 SNPs rs11568818 and rs11225297 were used to categorize hazards among 1,079 Chinese breast cancer patients. DFS: disease-free survival; OS: overall survival. All estimates adjusted for age, stage, ER, PR, menopausal status, and patient treatment.

Figure 3. Survival Functions determined by MMP-7 rs1568818 and rs11225297 Genotypes.

Kaplan-Meier survival functions determined by two SNPs: rs1568818 (A/G) and rs11225297 (A/T). Reference category: AA or AG, and AA; Medium risk: AA or AG, and AT; Low risk: AA or AG, and TT; High Risk GG, and AA or AT.

Discussion

We evaluated the association between MMP-7 polymorphisms and breast cancer survival using a large, population-based study of 1,079 Chinese breast cancer patients that were followed for a median of 7.1 years. Common genetic variations of the MMP-7 gene were found to be significantly associated with prognosis. Two polymorphisms in the promoter, rs17098318 and rs11568818, were in high LD, and found to be associated with increased hazards of disease progression and death in recessive models. One of these SNPs, rs11568818 had been previously reported to affect promoter activity, with the rare allele associated with increased MMP-7 expression (28). Additionally, we found a significant dose-response relationship between the rare allele for a SNP located in the 3′ flanking region of the gene, rs11225297, and reduced hazards. This novel finding supports the hypothesis that MMP-7 polymorphisms may be significant predictors of breast cancer prognosis.

Previous studies on MMP-7 have focused on expression data and immunohistochemical analyses. Constitutive expression has been shown to be present in both the ductal and glandular epithelium of the breast (8). Northern blot analysis demonstrated that MMP-7 mRNA was present in primary breast cancer specimens as well as uninvolved adjacent tissue samples, although tumors had significantly higher levels than surrounding tissues (9). Similarly, a small study of paired normal and tumor breast tissues found that MMP-7 staining was significantly stronger in cancer compared to normal cells (41). Associations between MMP-7 expression and breast cancer prognosis are less consistent. Two studies found significant associations with survival (41;42), while two studies found no association (9;43). The smallest study included only 81 cases and found no association with death, although survival time analysis was not conducted (9). The largest study, of 172 breast cancer cases, also found no association between MMP-7 expression and survival, although an inverse association between MMP-7 expression and tumor grade was reported (43). High MMP-7 expression was found to be associated with high grade tumors, advanced disease stage, and decreased survival in a study of 120 patients followed for a median of 120 months (41), and in a study of 131 women, each with a minimum of 5 years of follow-up (42). In addition, breast cancer patients that developed bone metastases were shown to have higher levels of circulating MMP-7 than patients without such metastases (44).

In the current study, polymorphisms in two regions of the MMP-7 gene were found to be associated with breast cancer survival. Increased hazards of disease progression and death were found to be associated with rs11568818, a SNP previously shown to directly affect MMP-7 expression (28). Although homozygotes for the variant alleles occurred at low frequencies, their resulting risks did reach statistical significance. Studies among Caucasians, or other populations with higher MAFs, will be interesting to see if this finding is replicated. Notably, all women found to have the rs11568818 GG genotype were premenopausal in this study population. In a recent study, Hughes et al. found that among Caucasian women in the study population, those with the rs11568818 GG genotype tended to have more lymph node metastases than women with other genotypes, and among all women in the study, GG homozygotes tended to have worse overall survival (31). These results, although not statistically significant, perhaps due to a small sample size, are, in general, consistent with our finding. Another promoter SNP shown to influence MMP-7 expression, rs11568819, was not found to be polymorphic in our study population; again, additional studies will prove interesting. In addition to the promoter SNPs, two polymorphisms 3′ of the MMP-7 gene were also found to be associated with breast cancer outcomes, and in contrast to the promoter SNPs, the associations were protective, and occurred in dose-response fashions. One of these SNPs, rs11225297, seemed to be the more informative for breast cancer survival as indicated by haplotype analysis. However, the other SNP, rs12184413, shares high linkage disequilibrium (D′=0.96), and moreover, we recently found it to be associated with a reduced risk of breast cancer (45). In silico analyses indicated that this region was enriched with CTCF binding factor binding sites (45). We also conducted in vitro experiments which showed that the rare allele reduced binding of nuclear protein extracts, further indicating a functional significance for this SNP (45). We can hypothesize that sequences surrounding and possibly including these downstream SNPs may function as a regulatory region that either directly influences MMP-7 expression, or else acts as an insulating element, separating the MMP gene cluster from the rest of chromosome 11.

A relationship between MMP-7 and breast cancer survival is well supported by several lines of evidence. First, the MMPs are best known as mediators of tumor metastasis, including tumor cell invasion, tumor-induced angiogenesis, degradation of the ECM and entry into the vasculature, and extravication at metastatic sites (46). For example, breast cancer cells made to over-express MMP-7 were found to have significantly increased levels of invasion (47). Further, when Jiang et al. designed retroviral transgenes to specifically target MMP-7 mRNA in breast cancer cells, transfection resulted in a significantly decreased degree of invasion, as well as significantly slower tumor growth after injection into mouse models (41). The MMPs have also been implicated in tumor cell survival (46); when MMP-7 was constitutively expressed, cultures were found to be enriched for cells with reduced sensitivity to apoptosis (48). By selecting for cells with decreased risks of death, tumors are more likely to grow and metastasize (46;48). The mechanism underlying this ability has been found to be attributable to a non-ECM proteolytic target of MMP-7, specifically cleavage of FasL (4). In addition to preventing Fas-mediated apoptosis, MMP-7 degradation of FasL has also been found to augment cytotoxic drug resistance in tumor cells (47;49). Similarly, when breast cancer cells were treated with the isoflavone, genistein, which has been shown to inhibit tumor growth and metastasis, MMP-7 was found to be significantly down-regulated (50).

MMP-7 is a small metalloproteinase with a large repertoire of downstream effects. While ECM degradation is essential for cancer progression and tumor metastasis, MMP-7 proteolysis of non-ECM targets has also been shown to play a role in disease pathology (46;51). Genetic variation in the promoter of MMP-7 has been shown to affect gene expression (28), and we have hypothesized that variation in the 3′ FR may also influence gene expression. Here, we report, for the first time, that individual molecular variation in both the promoter and 3′ FR of MMP-7 culminated in measurable survival differences among participants of the Shanghai Breast Cancer Study.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by USPHS grants R01CA64277, R01CA90899, and R01CA118229. The authors wish to thank the participants and research staff of the Shanghai Breast Cancer Study for their contributions and commitment to this project, and Brandy Venuti for clerical support in the preparation of this manuscript. We also wish to thank Shawn Levy and Melanie Robinson at the Vanderbilt Microarray Shared Resource, where genotyping was done. The Resource is supported by the Vanderbilt Ingram Cancer Center (P30 CA68485), the Vanderbilt Diabetes Research and Training Center (P60 DK20593), the Vanderbilt Digestive Disease Center (P30 DK58404) and the Vanderbilt Vision Center (P30 EY08126).

Abbreviations used

- MMP-7

Matrix metalloproteinase-7

- SNPs

single nucleotide polymorphisms

- OS

overall survival

- DFS

disease-free survival

- LD

linkage disequilibrium

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- IGFBPs

insulin-like growth factor binding proteins

- HB-EGF

heparin-binding epidermal growth factor

- SBCS

Shanghai Breast Cancer Study

- htSNPs

Haplotype tagging SNPs

- MAF

minor allele frequency

- QC

quality control

- HWE

Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium

- HR

Hazard ratios

- 95%CI

95% confidence intervals

Footnotes

Novelty: We conducted a large study to systematically evaluate individual MMP-7 genetic variation and breast cancer survival; two common SNPs were found to be significantly associated. First, a promoter variant that had been previously shown to affect MMP-7 transcription was shown here to be associated with decreased survival. Second, a 3′ polymorphism was found to be associated with improved survival in a dose-response manner, and may indicate a regulatory region downstream of the MMP-7 gene.

References

- 1.Quantin B, Murphy G, Breathnach R. Pump-1 cDNA codes for a protein with characteristics similar to those of classical collagenase family members. Biochemistry. 1989;28(13):5327–5334. doi: 10.1021/bi00439a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson CL, Matrisian LM. Matrilysin: an epithelial matrix metalloproteinase with potentially novel functions. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1996;28(2):123–136. doi: 10.1016/1357-2725(95)00121-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noe V, Fingleton B, Jacobs K, Crawford HC, Vermeulen S, Steelant W, Bruyneel E, Matrisian LM, Mareel M. Release of an invasion promoter E-cadherin fragment by matrilysin and stromelysin-1. J Cell Sci. 2001;114(1):111–118. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Powell WC, Fingleton B, Wilson CL, Boothby M, Matrisian LM. The metalloproteinase matrilysin proteolytically generates active soluble Fas ligand and potentiates epithelial cell apoptosis. Current Biology. 1999;9(24):1441–1447. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)80113-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu WH, Woessner JF, Jr, McNeish JD, Stamenkovic I. CD44 anchors the assembly of matrilysin/MMP-7 with heparin-binding epidermal growth factor precursor and ErbB4 and regulates female reproductive organ remodeling. Genes Dev. 2002;16(3):307–323. doi: 10.1101/gad.925702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haro H, Crawford HC, Fingleton B, Shinomiya K, Spengler DM, Matrisian LM. Matrix metalloproteinase-7-dependent release of tumor necrosis factor-{alpha} in a model of herniated disc resorption. J Clin Invest. 2000;105(2):143–150. doi: 10.1172/JCI7091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakamura M, Miyamoto S, Maeda H, Ishii G, Hasebe T, Chiba T, Asaka M, Ochiai A. Matrix metalloproteinase-7 degrades all insulin-like growth factor binding proteins and facilitates insulin-like growth factor bioavailability. Biochem Biophys Res Com. 2005;333(3):1011–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saarialho-Kere UK, Crouch EC, Parks WC. Matrix metalloproteinase matrilysin is constitutively expressed in adult human exocrine epithelium. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;105(2):190–196. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12317104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pacheco MM, Mourao M, Mantovani EB, Nishimoto IN, Brentani MM. Expression of gelatinases A and B, stromelysin-3 and matrilysin genes in breast carcinomas: clinico-pathological correlations. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1998;16(7):577–585. doi: 10.1023/a:1006580415796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mori M, Barnard GF, Mimori K, Ueo H, Akiyoshi T, Sugimachi K. Overexpression of matrix metalloproteinase-7 mRNA in human colon carcinomas. Cancer. 1995;75(6 Suppl):1516–1519. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950315)75:6+<1516::aid-cncr2820751522>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamashita K, Azumano I, Mai M, Okada Y. Expression and tissue localization of matrix metalloproteinase 7 (matrilysin) in human gastric carcinomas. Implications for vessel invasion and metastasis. Int J Cancer. 1998;79(2):187–194. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980417)79:2<187::aid-ijc15>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohashi K, Nemoto T, Nakamura K, Nemori R. Increased expression of matrix metalloproteinase 7 and 9 and membrane type 1-matrix metalloproteinase in esophageal squamous cell carcinomas. Cancer. 2000;88(10):2201–2209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kitoh T, Yanai H, Saitoh Y, Nakamura Y, Matsubara Y, Kitoh H, Yoshida T, Okita K. Increased expression of matrix metalloproteinase-7 in invasive early gastric cancer. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39(5):434–440. doi: 10.1007/s00535-003-1316-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luo HZ, Zhou ZG, Yang L, Yu YY, Tian C, Zhou B, Zheng XL, Xia QJ, Li Y, Wang R. Clinicopathologic and Prognostic Significance of MMP-7 (Matrilysin) Expression in Human Rectal Cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2005;35(12):739–744. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyi195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miyata Y, Iwata T, Ohba K, Kanda S, Nishikido M, Kanetake H. Expression of Matrix Metalloproteinase-7 on Cancer Cells and Tissue Endothelial Cells in Renal Cell Carcinoma: Prognostic Implications and Clinical Significance for Invasion and Metastasis. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(23):6998–7003. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamamoto H, Itoh F, Adachi Y, Fukushima H, Itoh H, Sasaki S, Hinoda Y, Imai K. Messenger RNA expression of matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1999;29(2):58–62. doi: 10.1093/jjco/29.2.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adachi Y, Yamamoto H, Itoh F, Hinoda Y, Okada Y, Imai K. Contribution of matrilysin (MMP-7) to the metastatic pathway of human colorectal cancers. Gut. 1999;45(2):252–258. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2.252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yonemura Y, Endou Y, Fujita H, Fushida S, Bandou E, Taniguchi K, Miwa K, Sugiyama K, Sasaki T. Role of MMP-7 in the formation of peritoneal dissemination in gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2000;3(2):63–70. doi: 10.1007/pl00011698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Masaki T, Matsuoka H, Sugiyama M, Abe N, Goto A, Sakamoto A, Atomi Y. Matrilysin (MMP-7) as a significant determinant of malignant potential of early invasive colorectal carcinomas. Br J Cancer. 2001;84(10):1317–1321. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamamoto H, Itoh F, Iku S, Adachi Y, Fukushima H, Sasaki S, Mukaiya M, Hirata K, Imai K. Expression of Matrix Metalloproteinases and Tissue Inhibitors of Metalloproteinases in Human Pancreatic Adenocarcinomas: Clinicopathologic and Prognostic Significance of Matrilysin Expression. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(4):1118–1127. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.4.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zeng ZS, Shu WP, Cohen AM, Guillem JG. Matrix Metalloproteinase-7 Expression in Colorectal Cancer Liver Metastases: Evidence for Involvement of MMP-7 Activation in Human Cancer Metastases. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8(1):144–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tanioka Y, Yoshida T, Yagawa T, Saiki Y, Takeo S, Harada T, Okazawa T, Yanai H, Okita K. Matrix metalloproteinase-7 and matrix metalloproteinase-9 are associated with unfavourable prognosis in superficial oesophageal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2003;89(11):2116–2121. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ajisaka H, Yonemura Y, Miwa K. Correlation of lymph node metastases and expression of matrix metalloproteinase-7 in patients with gastric cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51(57):900–905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones LE, Humphreys MJ, Campbell F, Neoptolemos JP, Boyd MT. Comprehensive Analysis of Matrix Metalloproteinase and Tissue Inhibitor Expression in Pancreatic Cancer: Increased Expression of Matrix Metalloproteinase-7 Predicts Poor Survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(8):2832–2845. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-1157-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Y, Jin X, Kang S, Wang Y, Du H, Zhang J, Guo W, Wang N, Fang S. Polymorphisms in the promoter regions of the matrix metalloproteinases-1, -3, -7, and -9 and the risk of epithelial ovarian cancer in China. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;101(1):92–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.09.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee KH, Shin SJ, Kim KO, Kim MK, Hyun MS, Kim TN, Jang BI, Kim SW, Song SK, Kim HS, Bae SH, Ryoo HM. Relationship between E-cadherin, matrix metalloproteinase-7 gene expression and clinicopathological features in gastric carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2006;16(4):823–830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang WS, Chen PM, Wang HS, Liang WY, Su Y. Matrix metalloproteinase-7 increases resistance to Fas-mediated apoptosis and is a poor prognostic factor of patients with colorectal carcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27(5):1113–1120. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jormsjo S, Whatling C, Walter DH, Zeiher AM, Hamsten A, Eriksson P. Allele-Specific Regulation of Matrix Metalloproteinase-7 Promoter Activity Is Associated With Coronary Artery Luminal Dimensions Among Hypercholesterolemic Patients. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21(11):1834–1839. doi: 10.1161/hq1101.098229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghilardi G, Biondi ML, Erario M, Guagnellini E, Scorza R. Colorectal Carcinoma Susceptibility and Metastases Are Associated with Matrix Metalloproteinase-7 Promoter Polymorphisms. Clin Chem. 2003;49(11):1940–1942. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2003.018911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kubben FJ, Sier CF, Meijer MJ, van den Berg M, van der Reijden JJ, Griffioen G, van de Velde CJ, Lamers CB, Verspaget HW. Clinical impact of MMP and TIMP gene polymorphisms in gastric cancer. Br J Cancer. 2006;95(6):744–751. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hughes S, Agbaje O, Bowen RL, Holliday DL, Shaw JA, Duffy S, Jones JL. Matrix Metalloproteinase Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms and Haplotypes Predict Breast Cancer Progression. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(22):6673–6680. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gao YT, Shu XO, Dai Q, Potter JD, Brinton LA, Wen W, Sellers TA, Kushi LH, Ruan Z, Bostick RM, Jin F, Zheng W. Association of menstrual and reproductive factors with breast cancer risk: results from the Shanghai Breast Cancer Study. Int J Cancer. 2000;87(2):295–300. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20000715)87:2<295::aid-ijc23>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shu XO, Gao YT, Cai Q, Pierce L, Cai H, Ruan ZX, Yang G, Jin F, Zheng W. Genetic polymorphisms in the TGF-beta 1 gene and breast cancer survival: a report from the Shanghai Breast Cancer Study. Cancer Res. 2004;64(3):836–839. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu H, Shu XO, Cui Y, Kataoka N, Wen W, Cai Q, Ruan ZX, Gao YT, Zheng W. Association of genetic polymorphisms in the VEGF gene with breast cancer survival. Cancer Res. 2005;65(12):5015–5019. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang X, Shu XO, Cai Q, Ruan Z, Gao YT, Zheng W. Functional Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor-1 Gene Variants and Breast Cancer Survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(20):6037–6042. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.The International HapMap Project. Nature. 2003;426(6968):789–796. doi: 10.1038/nature02168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Bakker PI, McVean G, Sabeti PC, Miretti MM, Green T, Marchini J, Ke X, Monsuur AJ, Whittaker P, Delgado M, Morrison J, Richardson A, et al. A high-resolution HLA and SNP haplotype map for disease association studies in the extended human MHC. Nat Genet. 2006;38(10):1166–1172. doi: 10.1038/ng1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hardenbol P, Yu F, Belmont J, Mackenzie J, Bruckner C, Brundage T, Boudreau A, Chow S, Eberle J, Erbilgin A, Falkowski M, Fitzgerald R, et al. Highly multiplexed molecular inversion probe genotyping: Over 10,000 targeted SNPs genotyped in a single tube assay. Genome Res. 2005;15(2):269–275. doi: 10.1101/gr.3185605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(2):263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin DY, Zeng D, Millikan R. Maximum likelihood estimation of haplotype effects and haplotype-environment interactions in association studies. Genet Epidemiol. 2005;29(4):299–312. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jiang WG, Davies G, Martin TA, Parr C, Watkins G, Mason MD, Mokbel K, Mansel RE. Targeting Matrilysin and Its Impact on Tumor Growth In vivo: The Potential Implications in Breast Cancer Therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(16):6012–6019. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vizoso FJ, Gonzalez LO, Corte MD, Rodríuez JC, Vázquez J, Lamelas ML, Junquera S, Merino AM, García-Muñiz JL. Study of matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2007;96(6):903–911. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mylona E, Kapranou A, Mavrommatis J, Markaki S, Keramopoulos A, Nakopoulou L. The multifunctional role of the immunohistochemical expression of MMP-7 in invasive breast cancer. APMIS. 2005;113(4):246–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2005.apm_02.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Voorzanger-Rousselot N, Juillet F, Mareau E, Zimmermann J, Kalebic T, Garnero P. Association of 12 serum biochemical markers of angiogenesis, tumour invasion and bone turnover with bone metastases from breast cancer: a crossectional and longitudinal evaluation. Br J Cancer. 2006;95(4):506–514. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beeghly-Fadiel AC, Long J, Gao YT, Li C, Qu S, Cai Q, Zheng Y, Ruan ZX, Levy SE, Deming SL, Snoddy JR, Shu XO, et al. Common MMP-7 polymorphisms and breast cancer susceptibility: a multi-stage study of association and functionality. Cancer Res. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0636. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Deryugina EI, Quigley JP. Matrix metalloproteinases and tumor metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2006;25(1):9–34. doi: 10.1007/s10555-006-7886-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang FQ, So J, Reierstad S, Fishman DA. Matrilysin (MMP-7) promotes invasion of ovarian cancer cells by activation of progelatinase. Int J Cancer. 2005;114(1):19–31. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fingleton B, Vargo-Gogola T, Crawford HC, Matrisian LM. Matrilysin [MMP-7] expression selects for cells with reduced sensitivity to apoptosis. Neoplasia. 2001;3(6):459–468. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mitsiades N, Yu WH, Poulaki V, Tsokos M, Stamenkovic I. Matrix metalloproteinase-7-mediated cleavage of Fas ligand protects tumor cells from chemotherapeutic drug cytotoxicity. Cancer Res. 2001;61(2):577–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee WY, Huang SC, Tzeng CC, Chang TL, Hsu KF. Alterations of metastasis-related genes identified using an oligonucleotide microarray of genistein-treated HCC1395 breast cancer cells. Nutr Cancer. 2007;58(2):239–246. doi: 10.1080/01635580701328636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Egeblad M, Werb Z. New functions for the matrix metalloproteinases in cancer progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2(3):161–174. doi: 10.1038/nrc745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]