Abstract

Pemphigus foliaceus (PF) is a blistering disease caused by autoantibodies to desmoglein 1 (Dsg1) that cause loss of epidermal cell adhesion. To better understand PF pathophysiology, we used phage display to isolate anti-Dsg1 mAbs as single-chain variable fragments (scFvs) from a PF patient. Initial panning of the library isolated only non-pathogenic scFvs. We then used these scFvs to block non-pathogenic epitopes and were able to isolate two unique scFvs, each of which caused typical PF blisters in mice or human epidermis models, showing that a single mAb can disrupt Dsg1 function to cause disease. Both pathogenic scFvs bound conformational epitopes in the N terminus of Dsg1. Other PF sera showed a major antibody response against the same or nearby epitopes defined by these pathogenic scFvs. Finally, we showed restriction of the heavy-chain gene usage of all anti-Dsg1 clones to only five genes, which determined their immunological properties despite promiscuous light-chain gene usage. These mAbs will be useful for studying Dsg1 function and mechanisms of blister formation in PF and for developing targeted therapies and tools to monitor disease activity.

INTRODUCTION

Pemphigus foliaceus (PF) is a tissue-specific autoimmune disease in which antibodies against the keratinocyte cell surface cause skin blisters (Stanley and Amagai, 2006). These blisters are due to loss of cell adhesion in the superficial living epidermis (that is the granular layer), as shown by the diagnostic histology from biopsies of the skin lesions of these patients. The autoantibodies in this disease were first detected by direct immunofluorescence in patients’ skin and by indirect immunofluorescence in their sera. Subsequently, it was shown that antibodies in these patients bind desmoglein 1 (Dsg1) (Koulu et al., 1984; Eyre and Stanley, 1987), a desmosomal cadherin found predominantly in the superficial layers of stratified squamous epithelia. Desmogleins are believed to function as cell–cell adhesion molecules which, in epidermis, maintain its integrity. Polyclonal anti-Dsg1 antibodies from PF patients have been shown to be pathogenic in organ culture of normal human skin and by passive transfer to neonatal mice, which result in blisters with the typical histology of PF from loss of cell–cell adhesion (Hashimoto et al., 1983; Roscoe et al., 1985; Rock et al., 1989).

Some patients with PF also have anti-Dsg4 antibodies (Kljuic et al., 2003; Nagasaka et al., 2004). Dsg4, similar to Dsg1, is found in the superficial epidermis (Bazzi et al., 2006). However, recent studies in which anti-Dsg4 activity is adsorbed out of PF sera suggest that the anti-Dsg4 activity is not necessary for disease activity of such sera (Nagasaka et al., 2004).

To date, studies of the pathophysiology of anti-Dsg1 antibodies have been performed with polyclonal antibodies from PF patients’ sera. Such studies have shown that in most patients, the predominant antibody response is directed against the N-terminal 161 amino acids of the 496 amino acids in the extracellular domain of Dsg1 and that such antibodies against the N terminus, where the transadhesion binding site is located, are necessary for pathogenicity (Sekiguchi et al., 2001). Furthermore, in the preclinical phase of fogo selvagem, a form of endemic PF in Brazil, patients develop IgG1 antibodies against the C terminus of the extracellular domain of Dsg1. In clinically affected patients, the antibody response switches to an IgG4 antibody against the N terminus of Dsg1 (Aoki et al., 2004). The switch from an IgG1 to an IgG4 response probably indicates a maturation of the immune response. This switch does not implicate the Fc region of IgG as necessary for disease because neither the effector region of IgG nor crosslinking by IgG is necessary for these PF antibodies to cause blisters. The latter conclusion comes from studies that show that PF Fab′ monovalent fragments alone are capable of causing typical disease in neonatal mice (Rock et al., 1990). In summary, these studies have been interpreted to suggest that antibodies are needed against the presumed N-terminal adhesive interface of Dsg1 to cause loss of cell adhesion.

The importance of targeting the N terminus of desmogleins to cause blister formation has also been demonstrated in studies of pemphigus vulgaris (PV), in which autoantibodies target Dsg3 and cause blisters deep in the epidermis. In a study with xenoantibodies against human Dsg3, made in a mouse, one anti-Dsg3 mAb that causes typical PV blisters targeted the adhesive interface of Dsg3 (Tsunoda et al., 2003). In addition, a human mAb cloned by phage display from a PV patient, which causes typical PV lesions in a mouse, is directed against the N-terminal 162 amino acids in mouse Dsg3 (Payne et al., 2005).

The study of PF serum-derived polyclonal antibodies has limitations for addressing many of the remaining questions regarding the pathophysiology of the autoantibodies in this disease. For example, are antibodies directed against the N terminus of Dsg1 both necessary and sufficient for disease? If so, can a single monoclonal, monovalent antibody, without the effector region of IgG, cause disease or are antibodies against multiple epitopes within this region necessary? If an antibody against a single pathogenic epitope is capable of causing disease, is that epitope also present in Dsg4? Do various PF sera have antibodies against the same pathogenic epitope? Finally, to consider the feasibility of developing specific therapy targeted to pathogenic autoantibodies, it is necessary to determine the genetic diversity of PF antibodies and whether specific antibody genes are preferentially used to produce them.

To address these questions, we used an antibody phage display library panning technique to clone monoclonal anti-Dsg1 single-chain variable fragment (scFv) antibodies from a PF patient. Representative initial clones isolated from the library by routine selection on Dsg1 were not pathogenic. To capture pathogenic monoclonal scFv from this library, we employed a non-pathogenic epitope-blocking approach. By panning the library against Dsg1 in the presence of previously isolated non-pathogenic scFvs, we isolated two unique clones of anti-Dsg1 scFv that were pathogenic in mouse and human skin. These human pathogenic mAbs did not crossreact with Dsg4. Binding competition experiments between these recombinant anti-Dsg1 scFvs and multiple PF patients’ sera demonstrated that PF patients show a major antibody response against the same or closely related epitopes, as those defined by the pathogenic scFvs. Genetic, functional, and immunological characterization of all pathogenic and non-pathogenic antibodies isolated from the PF scFv library showed that their heavy-chain gene usage was very restricted, that their immunologic properties correlated with antibody heavy-chain gene usage, and that, although the light-chain gene usage was more promiscuous, it was nevertheless restricted to a small group of 18 light-chain genes.

These data also show that a single monoclonal human antibody can disrupt the biological adhesion function of Dsg1 and cause the pathology characteristic of PF.

RESULTS

Isolation of non-pathogenic anti-Dsg1 scFvs from a PF patient

Peripheral blood lymphocytes from a patient with active PF were used to construct a library in which each phage particle displays an scFv antibody fragment on its surface and contains the cDNA encoding the heavy and light-chain variable regions for that particular scFv within. The library was screened by multiple rounds of panning on immobilized, baculovirus-produced Dsg1 using standard ELISA plate panning methods (Barbas III et al., 2001). From this first screening, we isolated 25 unique clones based on their heavy and light-chain nucleotide sequences. All these clones were derived from only two heavy-chain genes (VH1-18 and VH3-09) but used multiple light-chain genes. Representative antibodies using these heavy-chain genes were non-pathogenic in mice and human organ culture (see below). In order to try to increase the diversity of selected clones to find pathogenic antibodies, we remade the library and tested it again by panning on baculovirus-produced Dsg1 ELISA plates. In this second panning, we found another 30 unique clones, but again all but one used the VH1-18 and VH3-09 heavy-chain genes. In this panning, we found one additional clone that uses the VH1-08 heavy-chain gene (1-08/O12O2), but this clone was also non-pathogenic.

To address the possibility that the Dsg1 used in these initial rounds of selection might lack pathogenic epitopes either because it was produced in baculovirus or because critical epitopes were blocked due to ELISA plate adsorption artifacts, the phage library was panned in solution on mammalian-produced Dsg1 using a magnetic bead approach. However, the clones isolated using this panning method with the alternative form of Dsg1 yielded scFv clones that were again encoded by non-pathogenic VH1-18 and VH3-09 heavy-chain genes.

Table 1 shows the isolated clones and their nomenclature. (The table only lists clones with unique VDJ regions and light chains, but does not list clones that differed only by somatic mutations.)

Table 1.

Anti-Dsg1 clones representing each unique heavy chain (VDJ) and their associated light-chain genes

| IIF

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VH gene | Unique VDJ region1 | D gene | J gene | VL gene | Name of clone | Human skin | Mouse skin | Dsg1IB | Dsg4binding | Pathogenicity | Dsg1epitope |

| VH1 | |||||||||||

| VH1-18 | VDJ1 | D3-10/DXP′1 | JH4b | B3 | 1-18/B3 | + | + | ||||

| L8 | 1-18/L8 | + | − | + | |||||||

| L1 | 1-18/L1 | + | − | + | − | −2 | 164–401 | ||||

| L12 | 1-18/L12 | + | Weak + | + | − | − | 164–401 | ||||

| L2 | 1-18/L2 | ||||||||||

| LFVK431 | 1-18/LFVK431 | + | + | ||||||||

| VH1-08 | VDJ2 | D3-3/DXP4 | JH6b | O12/O2 | 1-08/O12O2 | + | + | − | + | − | 1–161 |

| VH3 | |||||||||||

| VH3-09 | VDJ3 | D2-2 | JH6b | O12/O2 | 3-093/O12O2 | Weak+3 | Weak+ | − | − | ||

| O18/O8 | 3-093/O18O8 | − | |||||||||

| L11 | 3-093/L11 | ||||||||||

| A30 | 3-093/A30 | ||||||||||

| 1c | 3-093/1c | ||||||||||

| 1e | 3-093/1e | ||||||||||

| 1g | 3-093/1g | ||||||||||

| 6a | 3-093/6a | ||||||||||

| VDJ4 | D3-3/DXP4 | JH3a | O18/O8 | 3-094/O18O8 | –4 | Weak+ | − | + | − | 1–161 | |

| VDJ5 | O18/O8 | 3-095/O18O8 | + | + | − | − | 1–161 | ||||

| L11 | 3-095/L11 | ||||||||||

| VDJ6 | L12 | 3-096/L12 | − | ||||||||

| O18/O8 | 3-096/O18O8 | Weak + | |||||||||

| 1c | 3-096/1c | ||||||||||

| VDJ7 | D3-3/DXP4 | JH3b | O12/O2 | 3-097/O12O2 | − | ||||||

| 1c | 3-097/1c | Weak + | Weak + | − | + | − | 1–161 | ||||

| VDJ8 | D3-22/D21-9 | JH4b | L11 | 3-098/L11 | Weak + | − | |||||

| VDJ9 | D2-8/DLR1 | JH2 | L8 | 3–099/L8 | |||||||

| L2 | 3-099/L2 | ||||||||||

| VDJ10 | D1-14/DM2 | JH6b | O18/O8 | 3-0910/O18O8 | |||||||

| VH3-07 | VDJ11 | D3-10/DXP′1 | JH4b | 1e | 3-07/1e | + | + | − | − | Weak+5 | 1–161 |

| VH3-30 | VDJ12 | D5-24 | JH4b | 3h | 3-30/3h | + | + | − | − | + | 1–161 |

Dsg1, desmoglein 1; Dsg1 epitope, amino-acid numbers in Dsg1; IB, immunoblot; IIF, indirect immunofluorescence.

Each VDJ recombinatory region is defined by a CDR3 (the third complimentary-determining region) amino-acid sequence. Because of extensive diversity in VDJ gene rearrangements, clones sharing identical VDJ sequences are considered to have arisen from the same B-cell clones.

Intradermal injection into human foreskin grafted SCID mice (Berking et al., 2001) was used to test pathogenicity for this clone.

One clone with unique light-chain VJ junction also stained epidermal basement membrane.

Showed cytoplasmic staining.

One clone with unique 1e VJ junction was negative.

Isolation of pathogenic anti-Dsg1 scFvs using a non-pathogenic epitope-blocking approach

Given that the use of conventional ELISA plate and in-solution antibody phage library selections yielded only clones of antibodies that were either not pathogenic by direct testing or unlikely to be pathogenic due to their immunologic properties (that is shared heavy-chain usage, binding only to denatured antigen, lack of binding to the cell surface of keratinocytes; see below), we speculated that pathogenic clones, if present in the library, may be there in amounts too low, relative to non-pathogenic antibodies, to easily isolate. We therefore designed a panning strategy to target the isolation of such putative low-abundant clones by blocking non-pathogenic epitopes with a set of previously isolated non-pathogenic clones. To accomplish this, soluble scFvs were expressed from representative clones utilizing heavy chains encoded by VH1-18 (1-18/L1, 1-18/L12) and VH3-09 (3-093/O12O2, 3-094/O18O8). By using this “non-pathogenic epitope blocking” approach, we isolated five additional unique clones that were pathogenic (see below) and were encoded by heavy-chain genes not previously seen in our set of non-pathogenic anti-Dsg1 antibodies (VH3-07 and VH3-30) (see Table 1).

Immunochemical properties of the anti-Dsg1 scFv are associated with their heavy-chain gene usage

ELISA analysis

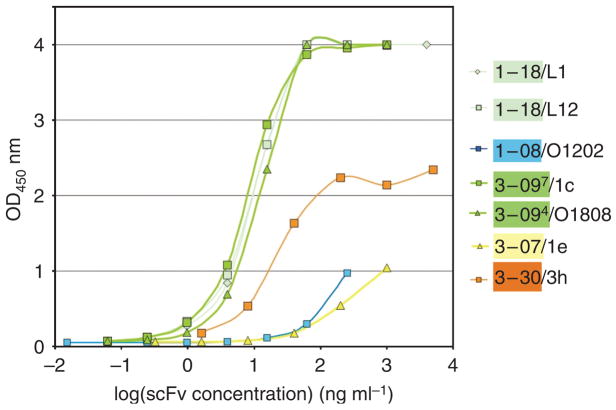

Representative soluble scFvs were tested for binding to Dsg1 (Figure 1) and Dsg3 by ELISA. All scFvs bound Dsg1, as expected, and did not bind Dsg3, except for two 3-07/1e clones (differed from each other only in their light-chain VJ recombination) that showed weak binding to Dsg3 at very high concentrations (data not shown). Six VH1-18 clones bound strongly by ELISA to Dsg1, giving an optical density (OD)450=1 at concentrations from 0.4 to 2.8 ng ml−1 (two clones shown in Figure 1, light green lines). VH3-09 clones also showed good binding to Dsg1; 9 of 12 clones tested gave OD450=1 at 0.5–20 ng ml−1 (dark green lines in Figure 1). The VH1-08 and VH3-07 clones showed much weaker binding, and the VH3-30 clone showed intermediate binding (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Binding curves of representative scFv antibodies against human Dsg1 by ELISA.

Serial dilutions of representative scFvs were measured by Dsg1 ELISA. Clones 1-18/L1 and 1-18/L12 (light green lines) and 3-094/O18O8 and 3-097/1c (dark green lines) show similar binding curves. In contrast, clones 1-08/O12O2 and 3-07/1e showed weak binding to Dsg1 ELISA. Clone 3-30/3h exhibited intermediate binding capacity.

Indirect immunofluorescence on mouse tail and human skin

All VH1-18 clones stained the cell surface of keratinocytes throughout the human epidermis, stronger in the more superficial epidermis, and identical to staining reported with PF serum (Table 1; Amagai et al., 1996; Shirakata et al., 1998). This pattern was also seen when antibodies were injected into human skin organ culture (Figure 5b). These VH1-18 antibodies did not stain mouse skin. In contrast, VH3-09 antibodies stained the cell surface of human keratinocytes weakly, if at all, and also did not bind well to mouse skin. There was a suggestion of some cytoplasmic staining of human epidermis with some of these VH3-09 antibodies, most marked with 3-094/O18O8 (Figure 2). The VH3-07 and VH3-30 clones strongly stained the cell surface of both human and mouse epidermis (3-30/3h shown in Figure 2; also see Figure 5). The staining with 3-30/3h was eliminated when the human skin was preincubated with EDTA (Figure 2), suggesting that the antibody binds a calcium-sensitive epitope.

Figure 5. A monovalent monoclonal anti-Dsg1 scFv causes typical PF blister formation in neonatal mice and human skin.

(a) Passive transfer of anti-Dsg1 scFvs into neonatal mice. Images were taken 6 hours after subcutaneous injection of scFvs. The gross appearance of the mice, and their skin histology and direct immunofluorescence are shown. Injection of 3-30/3h scFv caused gross blisters on the back (arrow), due to blistering in the granular layer of the epidermis. Direct immunofluorescence showed binding of these scFvs to the cell surface of the mouse epidermis (brackets indicate stratum corneum). (b) Pathogenicity assay using human skin. Anti-Dsg1 scFvs were injected into human skin specimens that were then cultured for 24 hours. Histology and direct immunofluorescence of the skin are shown. All scFvs, except 3-94/O18O8, bound to the cell surface of epidermal keratinocytes. 3-7/1e and 3-30/3h caused PF-like superficial epidermal blisters.

Figure 2. Indirect immunofluorescence of anti-Dsg1 scFvs on human skin.

Clone 3-30/3h scFv antibodies stained the cell surface of keratinocytes throughout the human epidermis. Pretreatment of human skin with EDTA prevented cell surface staining by 3-30/3h. Clone 3-094/O18O8 showed cytoplasmic staining in the superficial layers of the epidermis.

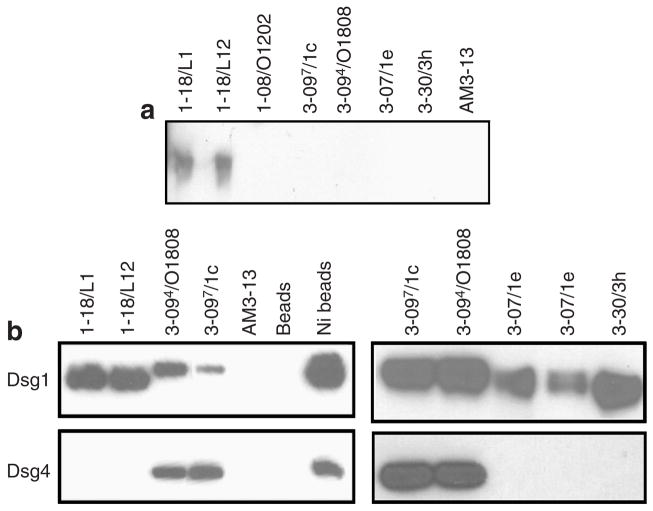

Binding to denatured Dsg1 and to unprocessed Dsg1 proprotein

VH1-18 clones bound denatured Dsg1 on immunoblots unlike any of the other clones tested (Table 1 and Figure 3a). Interestingly, in immunoprecipitation experiments using recombinant human Dsg1 produced by a baculovirus expression system, clones 3-094/O18O8 and 3-097/1c immunoprecipitated a Dsg1 polypeptide with a slightly greater apparent molecular weight on SDS-PAGE than other clones (Figure 3b). As it is known that the insect cells transfected with the recombinant baculovirus produce both the proprotein and mature protein forms of Dsg1 (Hanakawa et al., 2002), this finding suggests that they bind to the proprotein but not to the mature protein. Binding to the proprotein is consistent with the cytoplasmic staining seen by indirect immunofluorescence (Figure 2), because the proprotein is believed to be processed to the mature form as it reaches the cell surface (Wahl III et al., 2003).

Figure 3. Binding of anti-Dsg1 scFvs to denatured Dsg1 and to Dsg4.

(a) The purified ectodomain of human Dsg1 with an E-tag (Dsg1-EHis), produced by baculovirus, was used as an immunoblot substrate. ScFv heavy-chain variable regions encoded by the gene VH1-18, but not other scFvs, bound denatured Dsg1 on immunoblots. (b) Recombinant human Dsg1 or Dsg4 containing an E-tag (Dsg1-EHis or Dsg4-EHis), produced by baculovirus, was immunoprecipitated with representative anti-Dsg1 scFvs, control scFv (AM3-13), or Talon metal affinity resin (Ni-beads) and detected on an immunoblot by anti-E tag antibody.

Binding of Dsg4

Some pemphigus sera bind Dsg4 (Kljuic et al., 2003; Nagasaka et al., 2004), and this binding is thought to be due to antibodies against Dsg1 that crossreact with Dsg4. To determine whether any of our anti-Dsg1 mAbs crossreact with Dsg4, we used scFvs to immunoprecipitate recombinant Dsg4 containing a C-terminal E-epitope tag (Nagasaka et al., 2004), and then identified its presence on an immunoblot stained with anti-E tag antibodies. VH1-18, VH3-07, and VH3-30 antibodies did not bind Dsg4, whereas VH1-08 and VH3-09 antibodies did (Table 1 and Figure 3b).

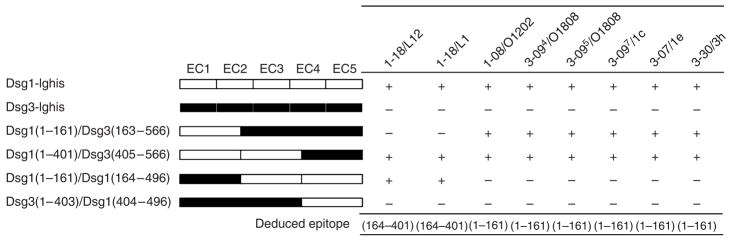

Epitope mapping of anti-Dsg1 antibodies

We used a series of four Dsg1/Dsg3 chimeric molecules to perform competition assays with our various anti-Dsg1 scFvs (Futei et al., 2000). As shown in Figure 4, VH1-18 clones bound to amino acid nos. 164–401, whereas all others mapped to the N terminus of Dsg1 (amino acid nos. 1–161) (Table 1).

Figure 4. Epitope mapping with competition ELISA.

Wild-type and domain-swapped extracellular domains of human Dsg1 and Dsg3 were produced by baculovirus and used as competitors in ELISA as described in the Materials and Methods section. The molecular structure of domain-swapped molecules is shown. “+,” greater than 40% inhibition.

Summary of immunochemical data

These data show that, in general, the properties of our isolated antibodies correlate with heavy-chain gene usage, even if the light chains are encoded by a diversity of variable region genes. Overall, the heavy chains of our anti-Dsg1 clones were encoded by only five different heavy-chain genes belonging to only two heavy-chain gene families (VH1 and VH3), whereas light-chain gene usage was significantly more promiscuous.

Light-chain shuffling shows that only certain light chains can pair with the restricted heavy chains to allow Dsg1 binding

Although the heavy-chain gene usage is generally associated with the immunochemical properties of these scFvs, and the light-chain gene usage is much less restricted, light-chain shuffling experiments show that the pairing of light and heavy chains is not entirely random, as only certain light chains allow binding to Dsg1. To demonstrate the light-chain contribution to Dsg1 binding, we constructed a derivative phage display library using the heavy chain of scFv 3-098/L11 paired with the entire original light-chain repertoire from the PF patient. Analysis of 16 clones from this derivative library before panning showed that none bound to Dsg1 by ELISA, even though all had the VH3-09 heavy chain. The clones did, however, bind an anti-hemagglutinin (HA) tag-coated ELISA plate, showing that the scFv (which is engineered to express the HA tag on its C terminus) was expressed on the phage surfaces. However, when this library was panned against Dsg1 to select anti-Dsg1 clones, these clones used the L11, A30, or 1c light-chain genes, as were found in the anti-Dsg1 clones isolated from the original libraries. These data suggest that only certain light chains permit Dsg1 binding when paired to this heavy chain.

A monoclonal anti-Dsg1 scFv can cause the pathology of PF

Initially, we tested for pathogenicity in the neonatal mouse model of pemphigus. Because VH1-18 and VH3-09 clones did not bind well to mouse skin by indirect immunofluorescence, we did not expect them to bind epidermis or induce pathology, which turned out to be the case (Table 1). However, clones 1-08/O12O2 and 3-07/1e did not induce pathology either, even though they did bind mouse epidermis (Figure 5a). Clone 3-30/3h, however, caused extensive gross blisters with the typical histology and direct immunofluorescence of PF (Figure 5a).

Given the possibility that some monoclonal anti-Dsg1 antibodies might be specific for human rather than mouse pathogenic epitopes, we tested representative scFv clones by injecting them into freshly isolated human skin biopsies, which were then maintained in organ culture for 24 hours. Immunofluorescence of these cultures showed binding of antibodies to the epidermal cell surface (except for VH3-09 antibodies, consistent with their weak binding to the keratinocyte cytoplasm by indirect immunofluorescence), but only 3-30/3h caused extensive histologic blisters (detaching essentially the whole stratum corneum) with features typical of PF, whereas 3-07/1e caused focal blisters (with areas of stratum corneum still attached) with typical histology (Figure 5b).

These findings demonstrate that an anti-Dsg1monoclonal (and monovalent) antibody that does not bind to Dsg4 can cause the pathology of PF. In addition, one clone (3-07/1e) was specific for a human pathogenic epitope not shared in the mouse, but one clone (3-30/3h) caused disease in both humans and mice.

A common pathologic epitope on Dsg1, defined by scFv 3-30/3h, is targeted by multiple PF sera and PV sera that contain anti-Dsg1 antibodies

ELISA inhibition studies, in which patients’ sera were used to inhibit the binding of scFv to Dsg1, were used to determine if antibodies from various patients bind at or near the epitopes bound by the scFv (Table 2). Most strikingly, clone 3-30/3h, the most pathogenic scFv, was inhibited by 6/6 PF sera and 5/5 PV sera that contain both anti-Dsg3 and anti-Dsg1 antibodies but none of the three PV sera that contain only anti-Dsg3 antibodies (Figure 6a). It is known that in mucocutaneous PV, the anti-Dsg1 antibodies are pathogenic (Ding et al., 1999). These results suggest that the pathogenic anti-Dsg1 antibodies in PF and mucocutaneous PV sera inhibit epitopes identical or similar to those defined by scFv 3-30/3h, suggesting that this clone defines an important epitope on Dsg1 that is targeted to cause pathology in many, if not all, PF and mucocutaneous PV patients.

Table 2.

Inhibition of anti-Dsg1 scFv binding by pemphigus sera in ELISA

| scFv

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VH | VL | PF sera | PV (3+1) sera1 | PV (3) sera |

| 1-18 | L1 | 2/62 | 0/5 | 0/3 |

| 1-18 | L12 | 1/6 | 0/5 | 0/3 |

| 1-08 | O12/O2 | 4/6 | 3/5 | 0/3 |

| 3-094 | O18/O8 | 4/6 | 0/5 | 0/3 |

| 3-095 | O18/O8 | 4/6 | 2/5 | 0/3 |

| 3-097 | 1c | 4/6 | 2/5 | 0/3 |

| 3-07 | 1e | 3/6 | 0/5 | 0/3 |

| 3-30 | 3h | 6/6 | 5/5 | 0/3 |

Dsg1, desmoglein 1; PF, pemphigus foliaceus; PV, pemphigus vulgaris; scFv, single-chain variable fragment.

PV(3+1) sera indicate PV sera containing anti-Dsg3 and anti-Dsg1 antibodies, whereas PV(3) sera means PV sera containing only anti-Dsg3 antibody.

The number of sera that inhibit/the number of sera tested.

Figure 6. Multiple pemphigus sera target the same or nearby epitopes defined by anti-Dsg1 scFvs.

(a) Six PF sera, five mucocutaneous PV sera containing Dsg1 and Dsg3 antibodies (PV(3+1)), three mucosal PV sera containing only Dsg3 antibody (PV (3)), and a normal control serum (N) were used to block the binding of pathogenic scFv clone 3-30/3h to Dsg1. All PF sera and all PV(3+1) sera tested inhibit the binding of 3-30/3h. (b) The binding of PF sera to Dsg1 was blocked by poly scFvs P3 (a mixture of scFvs derived from clones that bind Dsg1 after three rounds of routine pannings, and which contain almost all non-pathogenic scFvs as shown from previous characterization of these clones), pathogenic scFvs (3-07/1e and 3-30/3h), or a combination of poly scFvs P3 and pathogenic scFvs. Serum from PF patient 1 from which the phage library was made (PF1-nlib) and four other PF sera were tested. These results show that the scFv isolated by phage display from PF patient 1 block most epitopes bound by other PF sera and that other PF sera bind the epitopes (or nearby epitopes) defined by the two pathogenic clones. Clones 3-07 and 3-30 provide most of the inhibition of PF sera but are minor components of the poly scFv from the third panning (P3), which alone does not inhibit well most of the PF sera.

Other anti-Dsg1 clones were inhibited in their binding to Dsg1 by fewer PF and PV patients’ sera, suggesting that the epitopes defined by these clones were not as well preserved among patients as was that defined by clone 3-30/3h.

Epitopes defined by scFvs isolated from one PF patient comprise major targets of the autoantibody response in other PF patients

A mixture of non-pathogenic and pathogenic scFvs derived from PF patient 1 was tested for its ability to block the binding of various PF patient sera to Dsg1. As shown in Figure 6b, the mixture blocks > 90% of Dsg1 binding by the serum from the patient from whom the antibody phage display library was constructed (PF1-lib). This suggests that the isolated scFvs identify nearly all epitopes targeted by serum IgG from PF patient 1. In addition, this combination of scFvs blocks 70–100% of Dsg1 binding in four other randomly selected PF patient sera.

Furthermore, significant antibody responses against pathogenic epitopes are found across patients as evidenced by the ability of the two pathogenic scFv clones, 3-30/3h and 3-07/1e, to identify major pathogenic epitopes to which antibodies in many other PF sera bind closely. These two scFvs alone block 60% of binding of the serum from PF patient 1; 3-30/3h alone, the most pathogenic antibody, blocks this serum binding by almost 50%. The combination of 3-30/3h and 3-07/1e block the binding of unrelated PF patients’ sera by 46–83%, showing that the epitopes defined by these two scFvs are likely involved in many PF patients, and antibodies that bind to them (or nearby) are a major part of the autoantibody response in PF sera.

DISCUSSION

Utilizing antibody phage display and conventional library panning on Dsg1 isolated only non-pathogenic scFv mAbs from a PF patient. Clones that were repeatedly isolated were encoded by only two heavy chain genes (VH1-18 and VH3-09), although there was a greater diversity in the genetic origin of their light chains (Table 1). By blocking the epitopes defined by these non-pathogenic antibodies with a set of scFvs using these two VH genes, two additional clones were isolated that used distinct heavy-chain genes (VH3-30 and VH3-07) and were pathogenic. These clones show that a single monovalent, monoclonal anti-Dsg1 antibody can cause the formation of blisters that typify PF. Inhibition ELISA studies using these pathogenic scFv mAbs with multiple PF sera suggest that the pathogenic antibody response among patients with PF is limited and directed at similar or identical epitopes on Dsg1. These epitopes are located in the N terminus of Dsg1, an area that includes the transadhesive interface that has been shown to be a target for pathogenic anti-Dsg3 antibodies in PV (Tsunoda et al., 2003). In addition, the epitopes are conformational and calcium-stabilized, similar to pathologic Dsg3 epitopes in PV (Payne et al., 2005).

Analysis of the non-pathogenic and pathogenic clones that we isolated showed that their immunological properties correlated mostly with their heavy-chain gene usage. Very restricted heavy-chain gene usage, limited to only five genes, characterized the anti-Dsg1 antibodies. Although the light-chain gene usage was more promiscuous, light-chain shuffling experiments showed that only certain light chains were permissive for Dsg1 binding. Our findings also suggest that some antibodies may bind the proprotein of Dsg1 and not the mature protein. If so, patients may have a response against intracellular Dsg1 before it is completely processed. These latter findings suggest the intriguing possibility that PF patients might first develop antibodies against the intracellular proprotein to which they would not be expected to have tolerance, and in some susceptible patients the antibody response might extend to the mature molecule through epitope spreading.

Epitope blocking has been used with phage display in other contexts, for example, in finding neutralizing human mAbs against HIV-1 and respiratory synticial virus (Ditzel et al., 1995; Tsui et al., 2002). In our case, the use of blocking to mask non-pathogenic epitopes resulted in finding pathogenic antibodies that represented a major autoantibody response in various PF patients. This approach could be applied to other autoantibody-mediated diseases when routine panning might not be adequate.

Interestingly, VH3-30 gene usage, which defines the major pathologic antibody found here, has also been documented in other autoantibody-mediated diseases, such as auto-immune hemolytic anemia, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, and system lupus erythematosus (Efremov et al., 1996; Roben et al., 1996; Roark et al., 2002).

We previously isolated human anti-Dsg3 mAbs from a PV patient (Payne et al., 2005). Interestingly, some of the anti-Dsg3 antibodies share heavy-chain gene usage with our pathogenic anti-Dsg1 antibodies. For example, the pathogenic anti-Dsg3 antibody (D3)3c/9 was derived from VH3-07, as was one of the two pathogenic anti-Dsg1 antibodies from the PF phage library. Furthermore, this pathogenic anti-Dsg3 antibody, D(3)3c/9, reacted with both Dsg3 and Dsg1 (although weakly to the latter). Similarly, the pathogenic anti-Dsg1 scFv 3-07/1e also bound weakly to Dsg3. Further studies will be necessary to determine how common-shared heavy-chain gene usage is in the pathogenic antibodies from other PV and PF patients.

The findings presented here may have diagnostic and therapeutic implications for PF. For example, if the repertoire of pathogenic antibodies and their idiotypes are limited or are encoded by the same heavy-chain genes across patients, more targeted therapy might be possible (Payne et al., 2007). For example, if VH3-30 gene usage for the most pathogenic antibodies in PF is generalizable to most patients, then the infusion of Staphylococcal protein A might be used to inactivate B cells expressing those genes through a B-cell antigen receptor-induced apoptotic event as described in murine models (Graille et al., 2000; Goodyear and Silverman, 2003; Silverman and Goodyear, 2006) and as suggested for other autoimmune patients treated by extracorporeal protein A immunoabsorption (Silverman et al., 2005).

Another practical implication of our findings is that it may be possible to design “pathogenic antibody ELISAs” by blocking non-pathogenic Dsg1 epitopes with non-pathogenic scFvs, and then measuring anti-Dsg1 serum titers. Alternatively, inhibition by PF sera of binding of pathogenic scFvs to Dsg1 could be determined. It might then become feasible to determine if there is less pathogenic antibody (at least to these two major epitopes defined here) when patients are in remission and increased pathogenic antibody with more active disease.

In conclusion, we have isolated and characterized the first set of human mAbs against Dsg1 from a PF patient and have shown that a monoclonal human scFv can disrupt the function of Dsg1 and cause blistering typical of PF. The two pathologic scFvs from this patient define epitopes that are targets of a major antibody response in this and other PF patients. Finally, these reagents will be useful for understanding the molecular mechanism of blister formation in PF, the function of Dsg1 in adhesion, and may lead to targeted therapy and more accurate diagnostic tools for this severe blistering disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of phage library

Using previously described methods (Barbas III et al., 2001), we constructed separate IgG-κ and IgG-λ phage libraries from 1×107 mononuclear cells isolated from 50 ml of peripheral blood collected from a PF patient, a 76-year-old Caucasian woman with clinically active disease (involving approximately 30% of her body area) for 1 year in spite of being on prednisone 60mg q.d. Briefly, reverse transcriptase-PCR was used to amplify the immunoglobulin variable regions of the heavy (VH) and light chains (VL), and the gene fragments were then cloned into the phagemid vector pComb3X (Scripps Institute, La Jolla, CA). The phagemid library was electropolated into XL-1 Blue suppressor strain of E. coli (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) with superinfection by VCSM13 helper phage (Stratagene). In this system, filamentous phage particles express scFv antibodies (with a C-terminal 6× histidine tag and a HA tag) fused to the pIII bacteriophage coat protein. Recombinant phages were purified from culture supernatants by polyethylene glycol precipitation and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4 with 1% BSA containing1mM CaCl2. The library comprised more than 2 × 108 independent transformants as determined by titering on E. coli XL1-Blue after transformation. To validate library diversity, we analyzed the sequences of 14 phage clones from the unpanned library. We found no duplicate sequences and marked heterogeneity in VH and VL gene usage, similar to that found in normal human peripheral blood lymphocytes (data not shown).

Panning of phage library

Phage selection against Dsg1 absorbed to a solid phase

ELISA plates coated with recombinant Dsg1 (MBL, Nagoya, Japan) were used to isolate phage clones that express anti-Dsg1 scFv as described previously (Payne et al., 2005). Briefly, four wells were incubated with blocking buffer (50mM Tris pH 7.5, 150mM NaCl, 1mM CaCl2[TBS-Ca] with 3% skim milk) at room temperature for 1 hour. The phage library was diluted into blocking buffer and then incubated with Dsg1 on the wells for 2 hours at room temperature. After 5–10 washes with TBS-Ca containing 0.1% Tween 20, adherent phages were eluted with 76mM citric acid, pH 2.0, incubated for 10 minutes at room temperature and then neutralized with 2 M unbuffered Tris. The eluted phages were amplified in XL1-Blue E. coli and rescued by superinfection with VCSM13 helper phage. Phages were harvested from bacterial culture supernatant and then repanned against Dsg1 ELISA plates for three additional rounds. Individual phage clones were isolated from each round of panning and then analyzed for binding to Dsg1 by ELISA using horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-M13 antibody (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden). For epitope-blocked panning, the phage library was first mixed with purified recombinant non-pathogenic scFvs (clones 1-18/L1, 1-18/L12, 3-094/O18O8, and 3-093/O12O2) and then incubated on immobilized Dsg1 for 2 hours at room temperature.

Phage selection against mammalian-produced Dsg1 in solution

cDNA encoding the extracellular region of human Dsg1 fused with the Fc portion of human IgG1 and a histidine tag (six histidine residues) (Dsg1-IgHis) was subcloned into pcDNA3-1 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The resultant construct was transiently transfected into 293T cells using jet PEI (Polyplus-transfection Inc., New York, NY). The recombinant protein was purified from the culture supernatant with Talon metal affinity resin according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Clontech Laboratories Inc., Mountain View, CA).

The PF patient antibody phage library (2×1011 CFU (colony-forming units)) was precleared by incubation with the Fc fragment of human IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc., West Grove, PA), which was then removed by protein G magnetic beads (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA). The precleared phage library was then incubated with recombinant Dsg1-IgHis at room temperature for 20 minutes. Phages bound to Dsg1-IgHis were captured by protein G magnetic beads, washed with Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20, then eluted with 0.2 M glycine-HCl, pH 2.2 and immediately neutralized with 1 M Tris–HCl, pH 9.1. Eluted phages were amplified in XL1-Blue E. coli, followed by superinfection with helper phage as described above. Phages were harvested from bacterial culture supernatant and re-panned against Dsg1-IgHis in solution. Protein G magnetic beads and protein A magnetic beads (New England Biolabs) were used in alternate rounds of panning to avoid isolation of phage that bound non-specifically to protein A or G.

Sequence analysis of scFv antibodies

Recombinant phagemids were purified with a plasmid preparation system (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), and the VH and VL inserts were sequenced using pComb3X-specific primers described previously (Barbas III et al., 2001). The nucleotide sequences were compared with the germline sequences in V Base sequence directory (http://vbase.mrc-cpe.cam.ac.uk/) to determine their germline gene origins and interrelatedness.

Production and purification of soluble scFvs

The Top10 F′ non-suppressor strain of E. coli (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA) was infected with an individual phage clone, and soluble scFvs were purified from the bacterial periplasmic space using sucrose shock or Fastbeak (Promega, Madison, WI) and Talon metal affinity resin (Clontech Laboratories Inc.) as described previously (Payne et al., 2005).

Dsg1 and Dsg3 scFv ELISA

The reactivity of scFv against human Dsg1 and Dsg3 was measured by Dsg1 and Dsg3 ELISA (MBL) using HRP-conjugated anti-HA mAb (clone 3F10, 1:1,000 dilution; Roche Diagnostics Corp., Basel, Switzerland) as a secondary antibody as described (Payne et al., 2005).

Inhibition ELISA

Inhibition of scFv binding by pemphigus sera

Inhibition ELISA to block the binding of scFv to Dsg1 by pemphigus sera was performed as described previously for PV mAbs (Payne et al., 2005). Briefly, scFvs were used at dilutions that resulted in an OD450 reading of approximately 1.0 in the Dsg1 ELISA in the absence of blocking serum. The diluted scFv, mixed with pemphigus or normal control sera (10 μl), was analyzed by Dsg1 ELISA developed with HRP-conjugate anti-HA antibody. Inhibition was calculated according to the following formula: % inhibition=[1−(OD S/B−ODSc/B)/(OD S/Bc−ODSc/Bc)] × 100, where S is the scFv being tested, Sc the scFv-negative control, B the blocking pemphigus serum, and Bc the normal human serum.

Inhibition of PF sera binding by scFvs

PF sera were diluted to result in an OD450 reading of approximately 1.0 in the Dsg1 ELISA without competitors. The diluted PF sera, mixed with scFvs, were analyzed by Dsg1 ELISA developed with HRP-conjugate anti-human Fab antibody. Inhibition was calculated according to the following formula: % inhibition=[1−(OD T/B−ODN/B)/(OD T/Bc−ODN/Bc)] × 100, where T is the PF sera tested, N the normal control serum, B the blocking monoclonal anti-Dsg1 scFvs, and Bc the control scFv (AM3-13).

Epitope mapping by competition ELISA

Extracellular, domain-swapped Dsg1 and Dsg3 recombinant molecules were produced by a baculovirus expression system as described previously (Futei et al., 2000). ScFvs were diluted so that Dsg1 ELISA readings at OD450 were approximately 1.0 in the absence of a competitor. The diluted scFvs were incubated with an excess amount of baculovirus culture supernatant containing the recombinant proteins for 30 minutes at room temperature. Immunoblot analysis confirmed that each culture supernatant contained approximately the same amount of recombinant protein (data not shown). The mixture was subjected to Dsg1 ELISA (MBL) developed with HRP-anti-HA antibody. Inhibition was calculated using the following formula: inhibition (%)=[1−(OD competitor−OD blank)/(OD-negative−OD blank)] × 100, where OD competitor is an OD obtained with scFv incubated with culture supernatant with a recombinant baculoprotein; OD-negative is an OD obtained with sera incubated with culture supernatant of uninfected High Five insect cells; OD blank is an OD obtained with secondary antibody only. Greater than 40% inhibition was considered positive.

Direct and indirect immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence for scFvs was performed on human skin, mouse tail, or neonatal mouse skin as described previously (Payne et al., 2005). Binding was detected with rat monoclonal anti-HA antibody (3F10, 1:100 dilution; Roche Diagnostics) followed by Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated anti-rat IgG (1:200 dilution; Invitrogen).

Immunoblotting

The ectodomain of human Dsg1 tagged with an E-tag and a histidine tag (Dsg1-EHis), produced by a baculovirus expression system, was used as substrate (Ishii et al., 1997). The recombinant proteins were size fractionated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were incubated with scFvs diluted in phosphate-buffered saline/5% milk, followed by HRP-conjugated anti-HA antibody (1:1,000 dilution; Roche Diagnostics) and developed by ECL plus reagent (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences).

Immunoprecipitation–immunoblotting analysis for Dsg4 binding

To determine whether anti-Dsg1 scFvs also bind Dsg4, we used baculovirus-produced recombinant human Dsg4-EHis and human Dsg1-EHis (“EHis” tag defined above) (Nagasaka et al., 2004). Baculovirus-infected insect cell culture supernatants containing recombinant molecules were incubated with scFvs for 30 minutes and then immunoprecipitated with anti-HA agarose (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) at 4°C for 2 hours with gentle rotation. After washing with TBS-Ca, the immunoprecipitates were resuspended in Laemmli sample buffer, separated by SDS-PAGE and then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Membranes were probed with HRP-conjugated anti-E-tag antibody (1:2,000 dilution; GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences).

Neonatal mouse injection

Purified scFv (100 μl) were injected subcutaneously along the back into 1- to 2-day-old neonatal C57Bl/6J mice. The mice were killed at 6 hours, and the skin was harvested for direct immunofluorescence and for histology. All mouse studies were approved by the University of Pennsylvania IACUC Committee.

Human skin organ culture injection

Specimens were obtained from leftover normal skin after excisional surgery. The specimens were trimmed by removing fat tissue and cut into 5-mm diameter pieces. After an intradermal injection of 50 μl of purified scFv using an insulin syringe, skin specimens were put on the insert of transwells (Corning, NY) with defined keratinocyte SFM (Invitrogen) containing 1.2mM CaCl2 in the outer compartment. At 24 hours, the skin was harvested for direct immunofluorescence and for histology.

Institutional review board approvals

All studies involving mice, human blood, and skin were approved by the appropriate University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Masayuki Amagai for critical reading of the manuscript and providing the Dsg constructs, Dr Yasushi Hanakawa for advice on the pathogenicity assay using human skin organ culture, Dr Kazuyuki Tsunoda for advice on epitope mapping, Dr Koji Nishifuji for providing the Dsg4 construct, Dr Aimee S. Payne for helpful discussions, Stephen Kacir for valuable advice regarding antibody phage display library construction, and Hong Li for technical assistance. This work was supported by grants (1RO1AR48223 and 1RO1AR052672) from the National Institute of Arthritis, Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases to J.R.S.

Abbreviations

- Dsg

desmoglein

- HA

hemagglutinin

- HRP

horseradish peroxidase

- PF

pemphigus foliaceus

- PV

pemphigus vulgaris scFv, single-chain variable fragment

- VH

variable region heavy chain

- VL

variable region light chain

- TBS

Tris-buffered saline

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Drs Ishii, Siegel, and Stanley have filed for a provisional patent on the antibodies described herein.

References

- Amagai M, Koch PJ, Nishikawa T, Stanley JR. Pemphigus vulgaris antigen (desmoglein 3) is localized in the lower epidermis, the site of blister formation in patients. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;106:351–5. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12343081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki V, Millikan RC, Rivitti EA, Hans-Filho G, Eaton DP, Warren SJ, et al. Environmental risk factors in endemic pemphigus foliaceus (fogo selvagem) J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9:34–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1087-0024.2004.00833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbas CF, III, Burton DR, Scott JK, Silverman GJ. Phage display: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bazzi H, Getz A, Mahoney MG, Ishida-Yamamoto A, Langbein L, Wahl JK, III, et al. Desmoglein 4 is expressed in highly differentiated keratinocytes and trichocytes in human epidermis and hair follicle. Differentiation. 2006;74:129–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2006.00061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berking C, Takemoto R, Schaider H, Showe L, Satyamoorthy K, Robbins P, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta1 increases survival of human melanoma through stroma remodeling. Cancer Res. 2001;61:8306–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding X, Diaz LA, Fairley JA, Giudice GJ, Liu Z. The anti-desmoglein 1 autoantibodies in pemphigus vulgaris sera are pathogenic. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;112:739–43. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditzel HJ, Binley JM, Moore JP, Sodroski J, Sullivan N, Sawyer LS, et al. Neutralizing recombinant human antibodies to a conformational V2- and CD4-binding site-sensitive epitope of HIV-1 gp120 isolated by using an epitope-masking procedure. J Immunol. 1995;154:893–906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efremov DG, Ivanovski M, Siljanovski N, Pozzato G, Cevreska L, Fais F, et al. Restricted immunoglobulin VH region repertoire in chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients with autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Blood. 1996;87:3869–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyre RW, Stanley JR. Human autoantibodies against a desmosomal protein complex with a calcium-sensitive epitope are characteristic of pemphigus foliaceus patients. J Exp Med. 1987;165:1719–24. doi: 10.1084/jem.165.6.1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futei Y, Amagai M, Sekiguchi M, Nishifuji K, Fujii Y, Nishikawa T. Use of domain-swapped molecules for conformational epitope mapping of desmoglein 3 in pemphigus vulgaris. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:829–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodyear CS, Silverman GJ. Death by a B cell superantigen: in vivo VH-targeted apoptotic supraclonal B cell deletion by a Staphylococcal toxin. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1125–39. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graille M, Stura EA, Corper AL, Sutton BJ, Taussig MJ, Charbonnier JB, et al. Crystal structure of a Staphylococcus aureus protein A domain complexed with the Fab fragment of a human IgM antibody: structural basis for recognition of B-cell receptors and superantigen activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:5399–404. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.10.5399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanakawa Y, Schechter NM, Lin C, Garza L, Li H, Yamaguchi T, et al. Molecular mechanisms of blister formation in bullous impetigo and Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:53–60. doi: 10.1172/JCI15766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K, Shafran KM, Webber PS, Lazarus GS, Singer KH. Anti-cell surface pemphigus autoantibody stimulates plasminogen activator activity of human epidermal cells. A mechanism for the loss of epidermal cohesion and blister formation. J Exp Med. 1983;157:259–72. doi: 10.1084/jem.157.1.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii K, Amagai M, Hall RP, Hashimoto T, Takayanagi A, Gamou S, et al. Characterization of autoantibodies in pemphigus using antigen-specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays with baculovirus-expressed recombinant desmogleins. J Immunol. 1997;159:2010–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kljuic A, Bazzi H, Sundberg JP, Martinez-Mir A, O’Shaughnessy R, Mahoney MG, et al. Desmoglein 4 in hair follicle differentiation and epidermal adhesion: evidence from inherited hypotrichosis and acquired pemphigus vulgaris. Cell. 2003;113:249–60. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00273-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koulu L, Kusumi A, Steinberg MS, Klaus-Kovtun V, Stanley JR. Human autoantibodies against a desmosomal core protein in pemphigus foliaceus. J Exp Med. 1984;160:1509–18. doi: 10.1084/jem.160.5.1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagasaka T, Nishifuji K, Ota T, Whittock NV, Amagai M. Defining the pathogenic involvement of desmoglein 4 in pemphigus and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1484–92. doi: 10.1172/JCI20480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne AS, Ishii K, Kacir S, Lin C, Li H, Hanakawa Y, et al. Genetic and functional characterization of human pemphigus vulgaris monoclonal autoantibodies isolated by phage display. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:888–99. doi: 10.1172/JCI24185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne AS, Siegel DL, Stanley JR. Targeting pemphigus autoantibodies through their heavy-chain variable region genes. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:1681–91. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roark JH, Bussel JB, Cines DB, Siegel DL. Genetic analysis of autoantibodies in idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura reveals evidence of clonal expansion and somatic mutation. Blood. 2002;100:1388–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roben P, Barbas SM, Sandoval L, Lecerf JM, Stollar BD, Solomon A, et al. Repertoire cloning of lupus anti-DNA autoantibodies. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:2827–37. doi: 10.1172/JCI119111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rock B, Labib RS, Diaz LA. Monovalent Fab′ immunoglobulin fragments from endemic pemphigus foliaceus autoantibodies reproduce the human disease in neonatal Balb/c mice. J Clin Invest. 1990;85:296–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI114426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rock B, Martins CR, Theofilopoulos AN, Balderas RS, Anhalt GJ, Labib RS, et al. The pathogenic effect of IgG4 autoantibodies in endemic pemphigus foliaceus (fogo selvagem) N Engl J Med. 1989;320:1463–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198906013202206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roscoe JT, Diaz L, Sampaio SA, Castro RM, Labib RS, Takahashi Y, et al. Brazilian pemphigus foliaceus autoantibodies are pathogenic to BALB/c mice by passive transfer. J Invest Dermatol. 1985;85:538–41. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12277362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekiguchi M, Futei Y, Fujii Y, Iwasaki T, Nishikawa T, Amagai M. Dominant autoimmune epitopes recognized by pemphigus antibodies map to the N-terminal adhesive region of desmogleins. J Immunol. 2001;167:5439–48. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.5439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirakata Y, Amagai M, Hanakawa Y, Nishikawa T, Hashimoto K. Lack of mucosal involvement in pemphigus foliaceus may be due to low expression of desmoglein 1. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;110:76–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman GJ, Goodyear CS. Confounding B-cell defences: lessons from a staphylococcal superantigen. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:465–75. doi: 10.1038/nri1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman GJ, Goodyear CS, Siegel DL. On the mechanism of staphylococcal protein A immunomodulation. Transfusion. 2005;45:274–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2004.04333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley JR, Amagai M. Pemphigus, bullous impetigo, and the staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1800–10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra061111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsui P, Tornetta MA, Ames RS, Silverman C, Porter T, Weston C, et al. Progressive epitope-blocked panning of a phage library for isolation of human RSV antibodies. J Immunol Methods. 2002;263:123–32. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(02)00032-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsunoda K, Ota T, Aoki M, Yamada T, Nagai T, Nakagawa T, et al. Induction of pemphigus phenotype by a mouse monoclonal antibody against the amino-terminal adhesive interface of desmoglein 3. J Immunol. 2003;170:2170–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.4.2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl JK, III, Kim YJ, Cullen JM, Johnson KR, Wheelock MJ. N-cadherin-catenin complexes form prior to cleavage of the proregion and transport to the plasma membrane. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:17269–76. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211452200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]