Abstract

The present study examined trajectories of paternal support and maternal depressive symptoms over the first two years after the birth of a child. First time mothers (N= 582) were assessed 6 times during the first 24 months of their child's life. At each assessment they reported on a number of ways in which their child's father provided support, and at three of the assessments, their own depressive symptomatology was assessed. Latent growth curve models revealed that while higher support was related to lower depressive symptomatology, both paternal support and maternal depression tended to decrease over time. The relationships between paternal support and maternal depression are complex and suggest the importance of considering the multiple ways that parents influence one another over time.

The birth of a child is often associated with many new challenges for a young couple. The additional stresses of parenting have been related to decreases in psychological well-being for new parents in generally stable relationships (Salmela-Aro, Aunola, Saisto, Halmesmaki, & Nurmi, 2006). The effects of the transition to parenting on parental well-being may be even more profound among unmarried parents. Given the dramatic increase in the number of children born to unmarried parents in the last several decades (from 5.3 percent in 1960 to 36.8 percent in 2005; Hamilton, Martin, & Vetura, 2006; Ventura & Bachrach, 2000), it is important for researchers to understand the correlates of parental well-being and the nature of the interactions that occur between parents as they negotiate the task of raising a child. This paper focuses specifically on the ways that paternal support and maternal depression are related to one another during the first two years after the birth of a child in a sample of predominately young, economically-disadvantaged mothers.

Paternal Support

Fathers may provide support to their families and children in a number of different ways. For instance, fathers can be involved with their children by having physical proximity, taking financial and emotional responsibility for their well-being, and/or engaging in direct activities with their children (Lamb, 1987). Each of these types of support has been linked to positive outcomes for both mothers (Kalil, Ziol-Guest, & Coley, 2005) and children (Downer & Mendez, 2005; McBride, Schoppe-Sullivan, & Ho, 2005).

The support that fathers provide to the mothers of their children can be categorized as either emotional or instrumental. Emotional support typically refers to help received when someone acts as a confidant or a “listening ear.” In contrast, instrumental support usually reflects tangible assistance such as providing childcare or transportation. Although both types of social support have been demonstrated to be important for new mothers (Kroelinger & Oths, 2000), emotional support may be less likely to be received by mothers who are not romantically involved with the father of her child. In contrast, instrumental support - often implied within the definition of “father involvement” - is not as explicitly linked to the couple relationship. For instance, the ability to provide economic support to families has been found to be an important aspect of paternal identity for disadvantaged, non-resident fathers (Amato & Gilbreth, 1999; Furstenburg, 1995) as well as for married men (Marsiglio, Day, & Lamb, 2000). In addition to economic support for families, fathers often provide instrumental supports such as diapers and food or assistance with childcare (Marsiglio et al., 2000). Overall, the evidence suggests that instrumental support is a central component of father involvement that is not necessarily biased toward married or resident fathers.

Support and Depression

A number of studies have examined the effects of paternal support in both instrumental and emotional domains in predicting outcomes such as maternal smoking during pregnancy, children's birth outcomes, and breastfeeding (Elsenbruch et al., 2007; Kiernan & Pickett, 2006). In general, higher levels of support are linked to more positive outcomes for mothers. Paternal support and involvement have also been related to maternal depression. For example, Malik et al. (2007) examined predictors of maternal depression using a sample of families who participated in Early Head Start. They found that lower levels of emotional support from partner and lower levels of relationship satisfaction were predictive of higher levels of maternal depression, though they only examined these relationships at a single point in time. Jackson (1999) found that among single, African-American mothers, lower levels of instrumental support were associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms. Similar relationships were observed with a more diverse community sample as well (Mezulis, Hyde, & Clark, 2004).

The present study builds on these findings by examining the relationship between paternal instrumental support and maternal depression at multiple times over the first two years after the birth of a child. In addition to utilizing a longitudinal perspective, the present study examined bidirectional influences. Although previous research has suggested a causal link between fathers' provision of support and maternal depression (Beach, 2000; Malik et al., 2007), it may be the case that mothers with low levels of depressive symptoms elicit support more effectively than mothers with high levels of symptomatology. For instance, a mother with depressive symptoms may have a more strained relationship with her child's father, making him less likely to provide financial supports or help with child care. Conversely, the benefits of a father providing resources for his child may ease financial burdens on the mother, thus reducing her overall stress and improving well-being. This type of bidirectional influence between mothers and fathers is consistent with family systems theory, which suggests that family members influence each other in a myriad of ways, even across a variety of living arrangements (Scanzoni, Polonko, Teachman, & Thompson, 1989).

Although paternal support is related to a number of family and maternal factors across the life span such as children's socioemotional and academic functioning, and maternal well-being (Downer & Mendez, 2005; Elsenbruch et al., 2007; McBride et al., 2005), social support from fathers could be especially important for a mother's well-being in the first few years after giving birth. Borrowing from a developmental psychopathology perspective (Cummings & Davies, 1994), it may be normative for a new mother to experience depressive symptoms surrounding the birth of her child. Particularly for women who experienced traumatic deliveries, childbirth can be associated with an increase in depressive symptoms that will likely subside with time and do not predict later depression (Fatoye, Oladimeji, & Adeyemi, 2006). Paternal support is one factor that potentially influences the rate at which maternal depressive symptoms decline after the birth of a child.

Present Study

Although many researchers have identified child, family, and maternal characteristics that are associated with paternal support, few have identified a link between paternal support and maternal depression and none have explicitly explored how these processes interrelate over time. The present study contributes to this literature by examining these processes in detail over the first 24 months after the birth of a child. Rather than simply investigating support at one point and depression at the next, a longitudinal approach allows for a better understanding of the developmental processes at work in the dynamics between new parents. In the present study there were six waves of data concerning provision of paternal support and three waves of data on maternal depressive symptomatology. Given the unique nature of our sample (primarily young, single mothers) and that the maternal grandmother often influences both father involvement and maternal well-being (Kalil et al., 2005), the present study utilized grandmother co-residence and father co-residence as covariates of support and depression over time. This longitudinal perspective will provide insights into the patterns of change for both paternal instrumental support and maternal depressive symptoms in isolation as well as in combination with each other.

The present study tested three specific hypotheses. First, it was expected that paternal instrumental support would decrease over time. This is consistent with a research suggesting decreases in father involvement over the first years of a child's life among both nonresident fathers (Lerman & Sorensen, 2000; Rangarajan & Gleason, 1998; Seltzer, 1991) and residentia fathers (Hofferth, 2003). Second, it was also hypothesized that maternal depressive symptomatology would decrease over time. Although for some women the birth of a child is associated with post-partum depression (Fatoye et al., 2006), most new mothers do not experience clinical depression. Even so, depressive symptoms such as lack of energy and irritability may be more common among new mothers (Wisner, Parry, & Piontek, 2002). Successful adaptation to parenting is likely connected with a decrease in these symptoms of depression. Finally, it was expected that paternal support and maternal depression would be inversely related such that more paternal support would be associated with lower maternal depression. Moreover, it was anticipated that the relationships between paternal support and maternal depression over the first two years after the birth of a child would be constant across levels of maternal age, educational attainment, father residence, and grandmother residence.

Method

Participants

Participants were 582 mother-infant dyads from the Parenting for the First Time Project, a multi-site, longitudinal study following primiparous mothers and children from the prenatal period through the third year of life. Mothers were recruited from hospitals, health clinics, social service agencies, and school-aged mothers programs in South Bend, IN, Washington, D.C., Kansas City, KS, and Birmingham, AL. The sample consisted of 338 adolescent mothers and 244 adult mothers with a wide range of educational backgrounds. Mothers ranged in age from 15 to 35 years (mean age = 21.28) at time of childbirth and were ethnically diverse (65% African-American, 16% Caucasian, 15% Latina, and 4% Multi-Ethnic). During the prenatal period, the majority of mothers were single (63%), although many mothers were living with their partner (21%) or married (16%). In terms of educational attainment, 44% of mothers had not completed high school, 25% had a high school diploma or equivalency, and 31% had some college or vocational education. Similarly, 30% of fathers had not completed high school, 41% had a high school diploma or equivalency, and 28% had some college or vocational education. Fifty-six percent of mothers were living with their own mothers when children were 4 months old. Approximately 70% of families reported annual incomes below $20,000 (37% below $10,000) and only 13% earned more than $40,000 annually when children were 6 months old.

Participants were included in analyses if they had data from any one of the time points of interest. Full Information Maximum Likelihood Estimation was utilized to address missing data. The 4, 6, 8, 12, 18, and 24 month assessments had 18%, 27%, 27%, 24%, 29% and 37% missing data, respectively, on the father support variable. This level of missing data is comparable to other longitudinal studies of high-risk populations (e.g., Hansen, Tobler, & Graham, 1990; Kilpatrick, Acierno, Resnick, Saunders, & Best, 1997). Participants with missing data did not differ from those with complete data in terms of annual family income, F(1, 314) = 2.52, p > .05. However, mothers with complete data were older, F(1, 579) = 4.87, p < .05, and had higher educational attainment, F(1, 577) = 10.49, p < .01, than mothers with missing data. Subsequently, maternal age and educational attainment were included as covariates in the longitudinal analyses.

Design and Procedure

The present study utilized data gathered from mothers during their third trimester of pregnancy and when children were 4, 6, 8, 12, 18, and 24 months of age. Multiple efforts were taken to protect the rights of participants in accordance with IRB requirements. Consent forms were signed at the prenatal assessment and mothers were informed that they had the right to refuse any part or all of the subsequent assessments. For mothers who were younger than 18 years of age, parental consent forms were signed in addition to participant assent forms. Consent forms were resigned at each additional interview.

During the prenatal assessment, mothers were interviewed in the university laboratory. For assessments occurring when children were 4, 8, and 18 months of age, mothers were interviewed in their homes. When children were 6, 12, and 24 months of age, mothers and their children were invited to come to the university setting. Interviews typically lasted up to two hours; transportation was provided for participants when requested. Although the majority of laboratory-based assessments occurred in the university setting, in cases where the mother was unable to come to the university, the interview occurred in her home.

For the initial interview during the third trimester of pregnancy, each mother provided basic demographic information about herself and the father of her child, including age, education level, and father residential status. As part of a larger assessment protocol at each time point (4, 6, 8, 12, 18, and 24 months), mothers reported on the amount of support they received from their baby's father. In addition, at the 6-, 12-, and 24-month measurement points, mothers responded to self-report items measuring depressive symptomatology. At every interview, families were compensated for their participation with Wal-Mart gift cards. Participants were also contacted via telephone between interviews to maintain rapport and reduce attrition.

Measures

Social support from father

Social support from fathers was assessed utilizing 6 items drawn from the Life History Interview, an informal interview developed for the larger study. For each item, mothers indicated with a yes (coded as 1) or no (coded as 0) response whether the father of their baby provided support. Items were as follows: (1) “Does child's father provide financial or part-financial support?” (2) “Does child's father provide diapers, gifts, food, etc?” (3) “Does child's father provide help with childcare on a regular basis?” (4) “Does child's father visit the child?” (5) “Does child's father provide help with transportation?” and (6) “Does child's father provide by his family helping take care of the baby?” The dichotomous responses for each item were summed, creating a possible range of scores from 0 to 6, with higher scores indicating greater levels of support from fathers. Cronbach's alphas for the 6 items ranged from .87 to .89 across the 6 time points.

Depression

The BDI-II (Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996) is a new edition of the widely used Beck Depression Inventory (Beck & Steer, 1984) and has items that relate to depression criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders—Fourth Edition (DSM-IV). The measure consists of 21 items assessing the intensity of depression. For each item, respondents choose one of four statements relating to a particular depressive symptom, thus indicating severity of the symptom. A total score of 0-13 is considered minimal range, 14-19 is mild, 20-28 is moderate, and 29-63 is severe. The BDI-II was found to have better clinical sensitivity than the original version of the BDI with reliability coefficient alphas of .92 and .86, respectively (Beck et al., 1996). It is important to note that the BDI-II is a measure of depressive symptomatology and does not constitute a diagnosis of clinical depression.

Results

The present study utilized latent growth curve (LGC) modeling to examine paternal support and maternal depressive symptoms over time in a diverse sample of first-time parents. First, two unconditional growth models were evaluated, one for paternal support and one for maternal depression. Next, the two processes were analyzed together in a joint model. Finally, a conditional model was tested including maternal age at time of childbirth as well as prenatal educational level and father residence (living apart from child's father vs. married/cohabiting with child's father), and four-month grandmother residence (living apart from child's grandmother vs. living with child's grandmother) as static covariates.

Overview of Latent Growth Curve Modeling

The present study utilized LGC modeling to investigate changes in paternal instrumental support and maternal depressive symptoms during the 24 months following the birth of the mother's first child. Unconditional models of support and depression were evaluated separately. After confirming the fit of these models, a multivariate LGC was assessed in which the associations between the two processes were modeled simultaneously. Maternal age, education level, father residence, and grandmother residence were included as covariates.

LGC modeling is an approach that integrates individual growth modeling (i.e. hierarchical linear modeling) and structural equation modeling (SEM; Willet & Sayer, 1994). This method is well-suited for answering questions about how a process changes over time. LGC modeling provides estimates of mean structure (mean initial level and mean growth), reflecting the average starting point for all individuals (intercept) and the average rate of change (slope). Estimates of covariance structure are also given, indicating the degree of variability around the intercepts and slopes. If there is a significant amount of variability around the average values for these factors, it is appropriate to look for other variables which might explain the individual differences in initial status and pattern of change (Bollen & Curran, 2006).

It is also possible to model nonlinear change. Adding a quadratic parameter to a model which already includes an intercept and linear slope allows the growth trajectory to be curvilinear. In contrast to a purely linear model where the rate of change is presumed to be constant over time, a quadratic latent curve model allows the rate of change either to increase or decrease over time. For example, the magnitude of change in repeated measures may be larger in earlier years than in later years (Bollen & Curran, 2006). The addition of a quadratic trend also alters the interpretation of the linear slope, such that the linear slope coefficient now reflects the instantaneous rate of change at a specific point in time (Willet & Sayer, 1994). If the coefficient for the quadratic factor is negative, then the trajectory is concave to the time axis. Conversely, the presence of a positive quadratic trend indicates that the trajectory is convex to the time axis (Willet & Sayer, 1994).

Because LGC utilizes structural equation modeling techniques, the intercept and slope of a construct can be related to variables of interest, such as exogenous predictors, outcomes, or covariates (Duncan, Duncan, Strycker, Li, & Alpert, 1999). It is also possible to estimate the latent growth curves of two related processes and relate these processes to one another in one model; this is called a multivariate latent curve model (Bollen & Curran, 2006). Other benefits of growth curve analysis in an SEM framework include the ability to evaluate overall fit of measurement and structural components, to account for measurement error, and to address missing data. Most SEM software packages have an option for Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) estimation, which computes the likelihood function for each case utilizing all data available for that case (Bollen & Curran, 2006).

Evaluating model fit

Models were evaluated in terms of measures of goodness of fit, parameter estimates and standard errors using the Mplus modeling program (Muthen & Muthen, 2001). Generally, a satisfactory fit is indicated by a comparative fit index (CFI) close to one (Bentler, 1990) and a root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) less than or equal to .08 (MacCallum, Browne, & Sugawara, 1996). Significant parameter estimates and small standard errors likewise indicate good fit.

Descriptive Information

Paternal support

When children were 4, 6, 8, 12, 18, and 24 months of age, mothers reported on the amount of social support they received from their baby's father. Initially, mothers reported high levels of support in the form of financial assistance (75%), diapers (76%), childcare (64%), transportation (59%), visits (79%), and help from extended family (59%) at 4 months. Furthermore, when examining the amount of total support received (sum of all types of support), 57% of mothers reported that their baby's father provided 5 or more forms of support (out of 6) when their child was 4 months of age. However, on average, the total amount of support was decreasing over time. By 24 months, only 45% of mothers indicated that their baby's father provided 5 or more forms of support. Support at each time point was significantly correlated with support at all other time points, with coefficients ranging from .60 to .84.

Maternal Depression

When children were 6, 12, and 24 months of age, mothers reported on their depressive symptomatology using the BDI-II. The majority of mothers did not have elevated levels of depression symptoms: only 8%, 5%, and 8% of mothers were in the moderate to severe range at 6, 12, and 24 months, respectively. On average, depression scores were also decreasing over time. Depressive symptomatology at each time point was significantly correlated with ratings of symptoms at all other time points, with coefficients ranging from .41 to .56. The means, standard deviations, and ranges of paternal support and maternal depressive symptoms are presented in Table 1. Intercorrelations among all variables are presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Descriptive Information for Paternal Support and Maternal Depressive Symptoms

| Paternal Support | Maternal Depressive Symptoms | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean (SD) | Range | n | Mean (SD) | Range | |

| 4 Months | 476 | 4.05 (2.18) | 0-6 | |||

| 6 Months | 424 | 3.78 (2.26) | 0-6 | 384 | 8.74 (7.77) | 0-56 |

| 8 Months | 423 | 3.85 (2.28) | 0-6 | |||

| 12 Months | 441 | 3.61 (2.30) | 0-6 | 402 | 7.43 (6.77) | 0-50 |

| 18 Months | 416 | 3.41 (2.37) | 0-6 | |||

| 24 Months | 369 | 3.35 (2.33) | 0-6 | 351 | 7.26 (7.81) | 0-37 |

Table 2.

Inter-correlations Among Study Variables

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Support 4 | 1 | |||||||||||

| (476) | ||||||||||||

| 2. Support 6 | .82*** | 1 | ||||||||||

| (384) | (424) | |||||||||||

| 3. Support 8 | .77*** | .84*** | 1 | |||||||||

| (381) | (354) | (423) | ||||||||||

| 4. Support 12 | .71*** | .78*** | .83*** | 1 | ||||||||

| (373) | (360) | (355) | (441) | |||||||||

| 5. Support 18 | .67*** | .76*** | .76*** | .80*** | 1 | |||||||

| (351) | (326) | (331) | (350) | (416) | ||||||||

| 6. Support 24 | .60*** | .66*** | .68*** | .73*** | .79*** | 1 | ||||||

| (307) | (279) | (279) | (303) | (311) | (369) | |||||||

| 7. Depression 6 | −.11* | −.21*** | −.21*** | −.19** | −.18** | −.20** | 1 | |||||

| (347) | (377) | (320) | (322) | (295) | (257) | (384) | ||||||

| 8. Depression 12 | −.10† | −.09 | −.13* | −.13* | −.05 | −.08 | .53*** | 1 | ||||

| (342) | (327) | (322) | (399) | (320) | (280) | (296) | (402) | |||||

| 9. Depression 24 | −.05 | −.13* | −.15* | −.03 | −.03 | −.13* | .41*** | .56*** | 1 | |||

| (292) | (269) | (267) | (287) | (299) | (351) | (247) | (266) | (351) | ||||

| 10. Maternal Age | .16*** | .19*** | .16** | .18*** | .20*** | .24*** | −.22*** | −.02 | −.07 | 1 | ||

| (475) | (424) | (423) | (441) | (415) | (369) | (384) | (402) | (351) | (581) | |||

| 11. Maternal Education | .17*** | .16*** | .19*** | .18*** | .15** | .21*** | −.19*** | −.03 | −.06 | .59*** | 1 | |

| (476) | (424) | (423) | (441) | (416) | (369) | (384) | (402) | (351) | (581) | (582) | ||

| 12. Father Residence | .34*** | .35*** | .30*** | .37*** | .37*** | .31*** | −.16** | −.05 | −.05 | .35*** | .28*** | 1 |

| (469) | (419) | (416) | (434) | (409) | (364) | (380) | (396) | (347) | (573) | (574) | (574) | |

| 13. Grandmother Residence | −.26*** | −.28*** | −.22*** | −.28*** | −.30*** | −.29*** | .11* | .01 | .01 | −.40*** | −.26*** | −.35*** |

| (475) | (385) | (381) | (374) | (351) | (308) | (348) | (342) | (292) | (476) | (476) | (469) |

p <.001

p <.01

p <.05

p < .10

Growth Curve Models

Unconditional growth models

First, an unconditional growth model of paternal support was examined. Visual inspection of the raw data suggested that there were individual differences in intercepts and patterns of change over time. After observing the raw data, an unconditional model of paternal support was evaluated that specified quadratic growth over time. In this model, the latent intercept, linear slope, and quadratic trend were indicated by paternal support at 4, 6, 8, 12, 18, and 24 months. The factor loadings for the intercept factor were all set to 1. The loadings for the linear slope factor were fixed at 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 3.5, and 5.0 whereas the loadings for the quadratic trend factor were set to 0, 0.25, 1, 4, 12.25, and 25. Error variances were not allowed to correlate. No covariates or predictors were included in this unconditional model. This model (Model 1) displayed adequate fit, χ2 (12, N = 582) = 25.77, p < .05; RMSEA = .04; CFI = .99. There was a significant negative linear slope and a significant positive quadratic trend. When interpreting these growth parameters, it is important to note that the linear tread in a model that includes a quadratic trend is interpreted as the instantaneous rate of change. This means that for different snapshots of time, the rate of change may be different. As such, in order to determine how support was changing across time, we additionally examined the values for the linear slope when time was centered at 12 and 24 months, respectively. At 12 months, the linear trend was negative and at 24 months the linear trend was non-significant. Taken together, these findings suggest that, on average, support was decreasing at 4 and 12 months, but by 24 months there was no significant change. In other words, support was declining during the first year after the birth of the baby, but stabilized by the child's second birthday. There was also significant variability around the mean intercept, mean linear slope, and mean quadratic trend, suggesting that there were individual differences in initial levels of support and patterns of support over time.

Next, an unconditional model of maternal depression over time was examined. Visual examination of the data likewise indicated individual differences in initial level and patterns of change in depression over time. Since maternal depression was only measured at three time points (6, 12, and 24 months), it was only possible to test for a linear trend. In the unconditional growth model of maternal depression, the latent intercept and slope were indicated by depression at 6, 12, and 24 months. The factor loadings for the intercept factor were set to 1 and the loading for the linear slope were fixed at 0, 1, and 3. Error variances were not allowed to correlate and there were no covariates or predictors included in this model. The model (Model 2) displayed adequate fit, χ2 (1, N = 536) = 3.94, p < .05; RMSEA = .07; CFI = .99. The presence of significant parameter estimates for the slope indicated that, on average, mothers were decreasing in their depressive symptomatology over time. There was also significant variability around the mean intercept and mean slope, suggesting that there were individual differences in initial depression levels and change in depression over time.

Multivariate LGC models

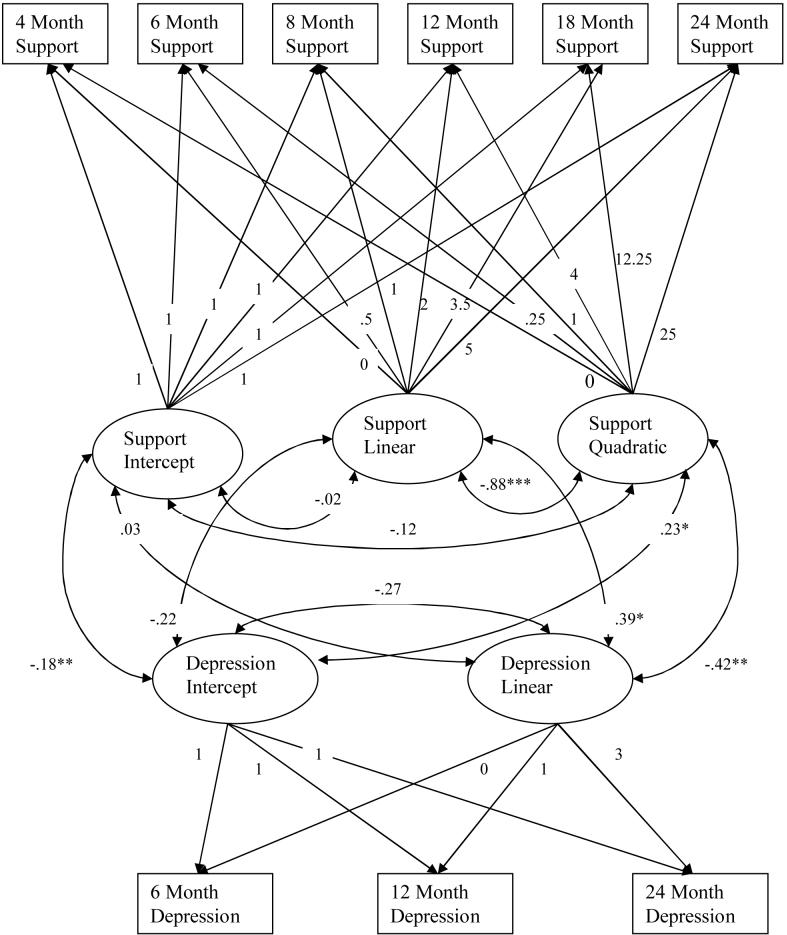

After examining the unconditional growth curve models for paternal support and maternal depression separately, the two processes were evaluated simultaneously in a multivariate LGC model wherein the intercepts and slopes of support and depression were allowed to freely correlate. In this model the factor loadings for paternal support remained the same as in Model 1 (intercept set at 4 months) and the loadings for maternal depression remained the same as in Model 2. As in previous models, error variances were not allowed to correlate. This model (Model 3) displayed acceptable fit, χ2 (25, N = 582) = 69.47, p < .05; RMSEA = .06; CFI = .98. As seen in Figure 1, there were several significant correlations among factors. The intercepts for paternal support and maternal depression were negatively correlated, β= −.18, p<.01, suggesting that higher levels of paternal support at 4 months were associated with lower levels of maternal depression at 6 months. The intercept of maternal depression was also positively correlated with the quadratic trend for paternal support, β= .23, p<.05, suggesting that mothers with low initial levels of depression tended to have rates of change in support that changed less than those with higher initial levels of depression. In other words, mothers with few depressive symptoms at 4 months experienced less rapid changes in support during the first 2 years after giving birth.

Figure 1.

Multivariate LGC model of paternal support with 4 month intercept and maternal depressive symptoms with 6 month intercept.

Note. Standardized coefficients

There were also significant relationships among the growth factors. The slope for maternal depression was positively correlated with the linear slope for paternal support, β= .39, p<.05, and negatively correlated with the quadratic trend for paternal support, β= −.42, p<.01. However, since the inclusion of the quadratic term in the model for father support alters the interpretation of the linear trend to reflect instantaneous rate of change, the rate of change in father support may differ depending on the centering of time. In order to better elucidate the relationships between change in support and change in depression across time, we also calculated two additional multivariate LGC models in which the father support intercepts were centered at 12 and 24 months, respectively. As expected, looking at different snapshots of time revealed different relationships among the growth factors. Specifically, when the father support intercept was set at 12 months, the relationship between the slope for maternal depression and the linear slope for paternal support was not significant. In contrast, when the intercept for paternal support was set to 24 months, the relationship between the slope of depression and the linear slope of support was negative, β= −.37, p<.01.

In sum, when examining the results of the models with different intercepts together (reflecting snapshots of time at 4, 12, and 24 months), the association between the linear trend of depression and the linear trend of support changed from a positive relationship at 4 months to a negative relationship at 24 months, with no significant association at 12 months. This implies that at 4 months, mothers with the fastest declines in depression tended to be those with the fastest declines in support, whereas at 24 months, mothers with the fastest declines in depression tended to be those with the slowest declines in support. More specifically, rapid improvements in depression were associated with rapid reductions in support shortly after birth (4 months) but by the toddler period the fastest improvements in depression were associated with the fastest increases in support. Because the quadratic term remained constant over time, the relationship between the slope for depression and the quadratic term for support remained negative in all models (intercepts centered at 4, 12, and 24 months), reflecting that mothers with the most rapid declines in depression from 6 to 24 months tended to be those with the most curvature in paternal support, that is faster rates of change. There were, however, still significant amounts of unexplained variance for all latent factors, suggesting that adding covariates to the model might help to explain these individual differences.

Finally, maternal age, education level, father residence (living apart from child's father vs. married/cohabiting with child's father), and grandmother residence (living apart from child's grandmother vs. living with child's grandmother) were added as covariates to the previous multivariate LGC model of paternal support and maternal depression (Model 3); specifically, all covariates were entered as predictors of all latent factors. Maternal age and education level were continuous variables. Father residence was coded 0 for living apart and 1 for married/cohabiting with child's father, and grandmother residence was coded 0 for not living with child's grandmother and 1 for living with child's grandmother. Although this model (Model 4) displayed adequate fit, χ2 (41, N = 582) = 99.76, p < .05; RMSEA = .05; CFI = .98, only two covariates, father residence and grandmother residence, were significant predictors of the latent factors. As such, a final, more parsimonious model was tested wherein only father residence and grandmother residence were included as covariates. This model (Model 5) likewise displayed adequate fit, χ2 (33, N = 582) = 79.68, p < .05; RMSEA = .05; CFI = .98.

There were significant relationships between father residence, grandmother residence, and the latent factors. Specifically, living apart from the child's father was associated with lower initial levels of paternal support, β=.27, p<.001, and higher initial levels of depressive symptomatology, β= −.15, p<.05. Additionally, grandmother residence was associated with paternal support, such that mothers who lived with their own mothers at 4 months received lower initial levels of paternal support, β= −.18, p<.01. Grandmother residence was not significantly related to depressive symptoms at 4 months. Neither father residence nor grandmother residence was related to the patterns of change over time for paternal support or depressive symptoms.

Consistent with the findings from the model without covariates (Model 3), in Model 5 the maternal depression intercept was negatively correlated with the paternal support intercept (set at 4 months), β = −.13, p<.05. The maternal depression intercept also was positively correlated with the quadratic trend of paternal support, although after including father and grandmother residence as covariates, this association was not significant at the .05 level, β = .21, p<.10. Also similar to the previous model, the maternal depression slope was positively correlated with the linear slope for paternal support, β = .36, p<.05, and negatively correlated with the quadratic trend for paternal support, β = −.41, p<.01. Thus, the patterns of association - and resulting interpretations - between intercepts and growth factors for the model including father and grandmother residence as covariates (Model 5) were the same as those found in the models without covariates.

Discussion

The present study utilized LGC modeling to examine trajectories of paternal support and maternal depressive symptoms across the first two years following the birth of a child. The current study built on previous research by examining the interrelations of support from fathers and maternal well-being using longitudinal methodology instead of cross-sectional data or data from two time points. The sophisticated design of the study allowed for an examination of the bidirectional interplay between support and depression as the processes changed over time. Also, the present study examined support and depressive symptomatology using a diverse sample of first-time mothers from a variety of family structures.

Changes in Paternal Support

Consistent with our hypothesis, the present study found that paternal support declines early after the birth of the child, but then the change levels off by 24 months. This early drop in father involvement has been reported in other studies as well (cf. Shannon, Tamis-LeMonda, London, & Cabrera, 2002). It is important to note that although support declined from 4 to 24 months, the overall level of instrumental support provided by fathers remained relatively high. For instance, at 24 months 45% of fathers still provided at least 5 forms of support in areas such as providing diapers, childcare, and financial assistance. High rates of continued father involvement have also been shown in the Early Head Start Father studies in which at 24 months, 80% of non-resident fathers still saw their children multiple times each week (Cabrera et al., 2004).

In keeping with previous research on father involvement, being married to or living with the child's father was associated with higher levels of initial instrumental support (Flouri & Buchanan, 2003), whereas living with the child's grandmother was associated with lower levels of support (Kalil et al., 2005). Although a young mother who lives with her own mother receives less instrumental support from her child's father than women who do not live with their mothers, she is likely to receive many of these supports from her mother or other family members (Oberlander, Black, & Starr, 2007). Even so, these mothers tend to be more disadvantaged than their counterparts who marry their child's father (McLanahan & Sandefur, 1994). However, it is important to highlight that although these factors were related to the initial level of support from fathers, they did not influence the pattern of change in support over time. It may be that the way in which paternal support changes as children age is more influenced by family process variables such as the quality of the relationship with the child's mother rather than by broader demographic factors such as marital status, educational attainment, or living arrangements.

Changes in Maternal Depression

The present study found that levels of maternal depression also declined from 6 to 24 months post-partum. This finding was both consistent with our hypothesis as well as with the extant literature. Particularly among mothers who do not have a previous history of mental illness, mild depressive symptoms after the birth of a child are fairly normative and tend to decline over time (Fatoye et al., 2006).

We also found that not living with the child's father was associated with a higher level of depressive symptoms at four months, but that father residence was unrelated to change in depressive symptomatology over time. This is consistent with other studies which have demonstrated concurrent links between marital status and psychological well-being (Talati et al., 2007). None of the other control variables (maternal age, educational attainment, or grandmother residence), however, were related to either initial depression levels or change in depression over time. It was particularly notable that changes in depressive symptoms were not influenced by age or education, as certain demographic characteristics such as low-SES tend to be associated with a heightened risk for depressive symptoms (Malik et al., 2007). Given that many mothers in this unique sample shared the same risk characteristics (predominately young, low-income mothers), it may be that, similar to other studies of high-risk samples, demographic variables are not as predictive as process variables (Farris, Smith, & Weed, 2007). Future work should consider more nuanced mechanisms related to patterns of change in depression as well as social support.

Links between Paternal Support and Maternal Depression

The results of the multivariate LGC models revealed that the intercepts for paternal support and maternal depressive symptoms were inversely related such that when levels of support where high at 4 months, levels of depression where low at 6 months. This pattern of higher levels of support being associated with fewer depressive symptoms was also found for the concurrent relationships at 6, 12, and 24 months. This is in line with previous research which has demonstrated that paternal support is positively related to maternal well-being after the birth of a child (Malik et al., 2007).

The present study also investigated how change in support was related to change in depressive symptoms. When examining correlations between the trajectories for support and depression at 4 months, decreases in support were associated with decreases in depression, but by 24 months, decreases in support were related to increases in depression. Given that higher levels of support are associated with lower levels of depressive symptoms (Beach, 2000; Jackson, 1999; Malik et al., 2007), we would expect that mothers who perceive support to be increasing over time would also be experiencing improvements in well-being. This was the pattern demonstrated when children were 24 months of age. However, at 4 months post-partum, decreases in support were related to decreases in depression. This finding is surprising and suggests that there is something unique about the relationship between change in support and change in depression directly following the birth of a child. Since the transition to parenting involves a reorganization of the family system and this process of adaptation to new roles unfolds over time (Cox & Paley, 1997), it may be that typically protective processes (i.e. increased support from fathers) do not function in expected ways during this period of high change. As a mother navigates the new challenges connected with caring for an infant, the perception of increasing involvement from the father of her child may actually induce more stress, resulting in increases in negative affect. In contrast, by the time the child is 2 years of age, many mothers potentially have successfully adapted to this new parenting role (Cox & Paley, 1997) and additional support from fathers may be more welcomed.

The importance of examining processes using longitudinal methods is particularly salient in this context. If we had only looked at one or two time points, we would have missed the finding that changes in support and depression operate differently depending on the amount of time since the birth of the child. This is why it is critical to have more than a single “snapshot” of family relations. The amount of support needed by mothers, as well as the fathers' propensity to provide support, may vary based on relationship factors or on the developmental needs of the child. Future work will need to examine these complex relationships between mothers and fathers as they adapt to their new parenting roles using closely spaced intervals over the first few months post-partum.

Limitations

The study was limited by the fact that only maternal reports were included. However, given that the impact of social support is largely dependent on the way that it is perceived (Reinhardt, Boerner, & Horowitz, 2006), using maternal reports in this context does not necessarily yield biased information. In fact, it may be perceived support that drives the relationship between paternal support and maternal depressive symptomatology. Sayil, Gure, and Ukanok (2006) found that lower maternal satisfaction with paternal physical support was associated with higher maternal depressive symptoms at 6-8 months post-partum. However, including paternal reports will be an important avenue for future research in order to more accurately assess the nature of the bidirectional relationships between parents, and particularly the ways that mothers influence paternal behaviors. Another limitation was the lack of a measure of mother-father relationship quality. Other studies have shown that the quality of the parent's relationship is related to both maternal well-being and co-parenting (Kolak & Volling, 2007). Thus, it may be that relationship quality is a mediating mechanism in the bidirectional relationship between paternal support and maternal depressive symptoms. As such, future studies should consider the changing nature of relationship quality, as well as related factors such paternal residential status, as it relates to changes in maternal well-being.

Finally, since the relationships between trajectories of maternal support and paternal involvement were examined using correlations, conclusions about causality are not warranted. It could be the case that fathers' provision of support provides relief from parenting stressors such that mothers experience improvements in their mental health. Conversely, a mother with low levels of depression may also have interpersonal skills that would be more likely to elicit support from her child's father than a mother who was suffering from depression. Most likely, the answer is not one or the other, but a complex combination of both. Additional research is needed to establish the extent to which fathers influence maternal behavior, mothers influence paternal behavior, as well as the way that they interact with and influence one another.

Implications and Conclusions

In light of these findings, several implications for practice are warranted. First, perceptions of instrumental support from the father seems to be intricately tied to maternal well-being, regardless of whether she lives with the father, her mother, or independently. Across family structures, there may be benefits associated with encouraging support from fathers. Given that this measure of support includes financial support, the findings suggest that both formal and informal child support payments from fathers may positively impact maternal mental health, which has been shown to be related to child well-being (Talati et al., 2007). Second, the fact that relationships between support and depression vary over time suggest the importance of long-term supports in place for families. In particular, we found that increases in support were associated with decreases in depression at 24 months, but not necessarily earlier. Thus, interventions within the first year after the birth of a child may not impact all processes that will likely develop in the following years. More specifically, our results suggest that family interventions should focus first on maternal well-being and later emphasize the importance of paternal involvement and support. Finally, considering the nature of relationships between maternal and paternal characteristics as bidirectional and changing over time is an important reminder that family processes are complex and development may best be supported using complex and varied strategies that are tailored to individual families and situations.

Acknowledgments

Support for preparation of this manuscript was provided by grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01 HD39456, T32 HD07489, and F32 HD054037). Senior members of the Centers for the Prevention of Child Neglect include John Borkowski, Judy Carta, Bette Keltner, Lorraine Klerman, Susan Landry, Craig Ramey, Sharon Ramey, and Steve Warren.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at http://www.apa.org/journals/fam/

Contributor Information

Leann E. Smith, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Kimberly S. Howard, Teachers' College, Columbia University

References

- Amato PR, Gilbreth JG. Nonresident fathers and children's well-being: A meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999;61:557–573. [Google Scholar]

- Beach SRH, editor. Marital and family processes in depression: A scientific foundation for clinical practice. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA. Internal consistencies of the original and revised Beck Depression Inventory. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1984;40:1365–1367. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198411)40:6<1365::aid-jclp2270400615>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory. 2nd ed. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Fit indexes, Lagrange multipliers, constraint changes and incomplete data in structural models. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1990;25:163–172. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2502_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA, Curran PJ. Latent curve models: A structural equation perspective. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; Hoboken, NJ: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera NJ, Ryan RR, Shannon JD, Brooks-Gunn J, Vogel C, Raikes H, et al. Low-income fathers' involvement in their toddler's lives: Biological fathers from the Early Head Start research and evaluation study. Fathering. 2004;2:5–30. [Google Scholar]

- Cox MJ, Paley B. Families as systems. Annual Review of Psychology. 1997;48:243–267. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT. Maternal depression and child development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1994;35:73–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb01133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downer JT, Mendez JL. African American father involvement and preschool children's social readiness. Early Education and Development. 2005;16:317–340. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan TE, Duncan SC, Strycker LA, Li F, Aplert A. An introduction to latent variable growth curve modeling. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; Mahwah, NJ: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Elsenbruch S, Benson S, Rücke M, Rose M, Dudenhausen J, Pincus-Knackstedt MK, et al. Social support during pregnancy: Effects on maternal depressive symptoms, smoking and pregnancy outcome. Human Reproduction. 2007;22:869–877. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farris JR, Smith LE, Weed K. Resilience and vulnerability in the context of multiple risks. In: Borkowski JG, Whitman TL, Farris J, Carothers SS, Keogh D, Weed K, editors. Risk and resilience: Adolescent mothers and their children grow up. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fatoye FO, Oladimeji BY, Adeyemi AB. Difficult delivery and some selected factors as predictors of early postpartum psychological symptoms among Nigerian women. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2006;60:299–301. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flouri E, Buchanan A. What predicts fathers' involvement with their children? A prospective study of intact families. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2003;21:81–98. [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg F. Fathering in the inner city: Paternal participation and public policy. In: Marsiglio W, editor. Fatherhood: Contemporary theory, research, and social policy. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1995. pp. 119–147. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Ventura SJ. National Vital Statistics Reports. vol 55. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2006. Births: Preliminary data for 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen WB, Tobler NS, Graham JW. Attrition in substance abuse prevention research: A meta-analysis of 85 longitudinally followed cohorts. Evaluation Review. 1990;14:677–685. [Google Scholar]

- Hofferth SL. Race/ethnic differences in father involvement in two-parent families: Culture, context, or economy? Journal of Family Issues. 2003;24:185–216. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson AP. The effects of nonresident father involvement on single black mothers and their children. Social Work. 1999;44:156–167. doi: 10.1093/sw/44.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman R, Sorensen E. Father involvement with their non-marital children: Patterns, determinants, and effects on their earnings. Marriage and Family Review. 2000;29:137–158. [Google Scholar]

- Kalil A, Ziol-Guest KM, Coley RL. Perceptions of father involvement patterns in teenage-mother families: Predictors of links to mothers' psychological adjustment. Family Relations: Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies. 2005;54:197–211. [Google Scholar]

- Kiernan K, Pickett KE. Marital status disparities in maternal smoking during pregnancy, breastfeeding and maternal depression. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;63:335–346. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Acierno R, Resnick HS, Saunders BE, Best CL. A 2-year longitudinal analysis of the relationship between violent assault and substance use in women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:834–847. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.5.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolak AM, Volling BL. Parental expressiveness as a moderator of coparenting and marital relationship quality. Family Relations. 2007;56:467–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2007.00474.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroelinger CD, Oths KS. Partner support and pregnancy wantedness. Birth. 2000;27:112–119. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536x.2000.00112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb ME. The father's role: Cross-cultural perspectives. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum RC, Browne MW, Sugawara HM. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods. 1996;1:130–149. [Google Scholar]

- Malik NM, Boris NW, Heller SS, Harden BJ, Squires J, Chazan-Cohen R, et al. Risk for maternal depression and child aggression in Early Head Start families: A test of ecological models. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2007;28:171–191. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglio W, Day RD, Lamb ME. Exploring fatherhood diversity: Implications for conceptualizing father involvement. Marriage and Family Review. 2000;29:269–293. [Google Scholar]

- Mezulis AH, Hyde JS, Clark R. Father involvement moderates the effect of maternal depression during a child's infancy on child behavior problems in kindergarten. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:575–88. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.4.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride BA, Schoppe-Sullivan SJ, Ho M. The mediating role of fathers' school involvement on student achievement. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2005;26:201–216. [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan SS, Sandefur G. Growing up in a single parent family: What hurts, what helps. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus user's guide. 2nd ed. Muthen & Muthen; Los Angeles: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Oberlander SE, Black MM, Starr RH. African American adolescent mothers and grandmothers: A multigenerational approach to parenting. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2007;39:37–46. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9087-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhardt JP, Boerner K, Horowitz A. Good to have but not to use: Differential impact of perceived and received support on well-being. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2006;23:117–129. [Google Scholar]

- Rangarajan A, Gleason P. Young unwed fathers of AFDC children: Do they provide support? Demography. 1998;35:175–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmela-Aro K, Aunola K, Saisto T, Halmesmaki E, Nurmi J. Couples share similar changes in depressive symptoms and marital satisfaction anticipating the birth of a child. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2006;23:781–803. [Google Scholar]

- Sayil M, Gure A, Ucanok Z. First time mothers' anxiety and depressive symptoms across the transition to motherhood: Associations with maternal and environmental characteristics. Women and Health. 2006;44:61–77. doi: 10.1300/J013v44n03_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer JA. Relationships between fathers and children who live apart: The father's role after separation. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1991;53:79–101. [Google Scholar]

- Scanzoni J, Polonko K, Teachman J, Thompson L. The sexual bond: Rethinking families and close relationships. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon JD, Tamis-LeMonda CS, London K, Cabrera N. Beyond rough and tumble: Low-income fathers' interactions and children's cognitive development at 24 months. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2002;2:77–104. [Google Scholar]

- Talati A, Wickramaratne PJ, Pilowski DJ, Alpert JE, Cerda G, Garber J, et al. Remission of maternal depression and child symptoms among single mothers. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2007;42:962–971. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0262-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura SJ, Bachrach CA. National vital statistics reports. vol 48. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, Maryland: 2000. Nonmarital childbearing in the United States, 1940-1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willet JB, Sayer AG. Using covariance structure analysis to detect correlates and predictors of individual change over time. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;116:363–381. [Google Scholar]

- Wisner KL, Parry BL, Piontek CM. Postpartum depression. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;347:194–199. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp011542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]