Abstract

Prions are unconventional infectious agents responsible for transmissible spongiform encephalopathies. Compelling evidences indicate that prions are composed exclusively by a misfolded form of the prion protein (PrPSc) that replicates in the absence of nucleic acids. One of the most challenging problems for the prion hypothesis is the existence of different strains of the infectious agent. Prion strains have been characterized in most of the species. Biochemical characteristics of PrPSc used to identify each strain include glycosylation profile, electrophoretic mobility, protease resistance, and sedimentation. In vivo, prion strains can be differentiated by the clinical signs, incubation period after inoculation and the vacuolation lesion profiles in the brain of affected animals. Sources of prion strain diversity are the inherent conformational flexibility of the prion protein, the presence of PrP polymorphisms and inter-species transmissibility. The existence of the strain phenomenon is not only a scientific challenge, but it also represents a serious risk for public health. The dynamic nature and inter-relations between strains and the potential for the generation of a very large number of new prion strains is the perfect recipe for the emergence of extremely dangerous new infectious agents.

I. Introduction

Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathies (TSEs), also known as prion disorders, are infectious and fatal neurodegenerative diseases affecting humans and other mammals. In humans, TSEs include Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), fatal familial insomnia (FFI), Gertsmann-Straussler-Scheinker Syndrome (GSS) and Kuru [1,2]. In other mammals, bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) is found in cattle, scrapie in sheep and goats and chronic wasting disease (CWD) in elk and deer [1,2]. Although the clinical symptoms vary in distinct diseases, they usually include dementia and/or ataxia with progressive loss of brain function, irreversibly resulting in death [3]. The hallmark of prion diseases is the misfolding of the prion protein observed in the brain of affected individuals [1]. Misfolded proteins have the intrinsic tendency to form large aggregates and fibrillar structures, that may form amyloid deposits in a similar fashion as observed in Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s diseases and many other protein misfolding disorders [4]. Although of rare occurrence, prion diseases have drawn considerable attention from the public and led to severe economic and political consequences in Europe and in the United States. The two main reasons of this impact include the unique nature of the infectious agent and the appearance of a new human disease (vCJD) linked to consumption of cattle meat infected by BSE. At present, it is impossible to estimate accurately the number of upcoming cases of vCJD due to the very long incubation time of the disease in humans [5–7]. Prion research has been plagued with the discovery of new and heretic scientific findings that have confronted the most solid paradigms in modern biology. The current evidence suggest that an abnormal form of the prion protein (termed PrPSc) is the main, and possibly the only, constituent of prion infectious agent [1]. This so called protein-only hypothesis [1,8] proposes that amplification of PrPSc occurs at expenses of the normal host’s version of the prion protein (termed PrPC). The new generated PrPSc have new biochemical characteristics compared to PrPC, for example its insolubility, resistance to denaturation, and its partial resistance to protease degradation [9]. PrPSc treatment with proteases reveal the protease resistant core of the infectious agent (termed PrP27–30 according to its molecular weight) [10].

II. Molecular basis of Prion strains

Among the unique features that have contributed to place the prion field in the spotlight, one of the most interesting is the prion strain phenomenon. It has been observed that animals affected by prion diseases may develop different pathologies and the clinical and biochemical outcomes could be maintained through several passages in rodents models of prion diseases. In analogy to other infectious agents, these variants have been termed strains. A classical definition of strain makes mention to a genetic variant or subtype of the infectious agent responsible for the disease, but this concept, valid in virology, can not be extended to prions. In early days, the strain phenomenon was claimed as one of the strongest evidences against the protein-only hypothesis [11,12]. It was assumed that the different phenotypes found in animals were due to differences in the genetic information contained within the TSE causing agent. However, currently it is widely accepted that the main differences between prion strains arise from alternative conformations of PrPSc that can be stably and faithfully propagated [13,14].

The first evidence about the existence of prion strains was described in goats affected by scrapie by Pattison and Millson in 1961 [15]. In this report, goats infected by the same batch of infectious scrapie agent developed two different clinical phenotypes, termed by the authors “scratching” and “nervous”, according to disease’s manifestation. The differences between these infectious agents were alleged to be the consequence of differences in the genetic background of the host. The current evidence supports this hypothesis. Clinical signs could be very useful to differentiate between prion strains [15–17]. Each prion strain has the capability to affect specific brain areas producing differences in clinical signs. In the case of scrapie in sheep and goats, after identification and isolation of the prion protein gene (prnp) several polymorphic differences were recognized when numerous sheep flocks were compared [18].

Prion strains can be classified by different parameters. Incubation periods, profile of histological damage and clinical signs are the main in vivo characteristics which can be used to differentiate between prion strains [16,19,20]. The most commonly used is incubation period which correspond to the time elapsed between experimental inoculation of the infectious agent and clinical onset of the disease. Intra-species inoculation of prions is usually very reproducible [19]. Inoculation of different prion strains preparations usually results in different and reproducible incubation times [19,21]. Histological studies have also shown substantial differences when animals were inoculated with distinct strains. The differences are mainly on the distribution and characteristics of PrPSc deposition and the degree of vacuolation in specific brain regions [22–25]. In order to quantify this aspect, a well standardized procedure for vacuolization scoring (lesion profile) in mice [25] has been described; nine gray matter and three white matter brain areas are analyzed and scored according to the magnitude of the damage. Using this approach, prion strains having similar incubation times were recognized, such as ME7 and 79A [25]. In a similar way, PrPSc accumulation profile has been useful to track the origin of the infectious material, such as in the case of the transmission of BSE into humans, originating vCJD, since both strains produce similar neuropathological signatures [26,27]. The clinical signs are also a characteristic that can be very useful to differentiate strains. For example, in human prion diseases, motor incoordination, dementia, ataxia, depression, and insomnia are just few from a much larger list of clinical symptoms that can appear depending on the strain of the agent [3]. In other animals, such as the case of hamsters, the clinical features can be diametrically opposed. That is the case of the Drowsy (DY) and Hyper (HY) prion strains [16]. Unfortunately, clinical signs can not always be applied to differentiate and classify prion strains. In mouse for example, several prion strains have the same rough signs, which include ataxia, rough coat, and hunch [28,29]. However, recent publications using more detailed tests have identified dissimilar behavioral deficits when different prion strains are administrated to mice [30]. Since different brain lesion patterns appear to be responsible for the variation in clinical signs, behavioral studies could give us more specific information about the type of brain damage produced by different prion isolates [30,31].

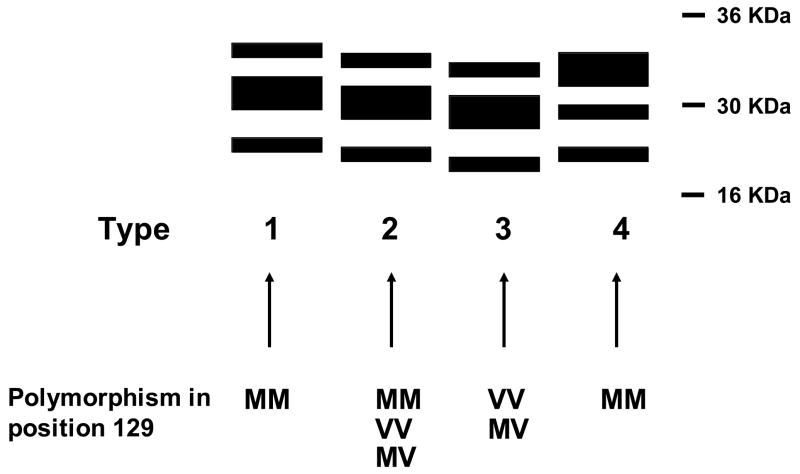

In addition to the in vivo differences, each prion strain has a particular group of biochemical characteristics in the infectious protein that could be specifically associated to them. Among them the most important are electrophoretical mobility after PK digestion [32–34], glycosylation pattern [33–35], extent of PK resistance [32], sedimentation [32] and resistance to denaturation by chaotropic agents [32,36]. Recently, differences in the binding affinity for copper among strains have been described [37]. As illustrated in figure 1, the biochemical features of PrPSc in various forms of CJD are different. The western blot profile of different sources of human PrPSc shows diversity in terms of glycosylation pattern and electrophoretical mobility after proteinase K (PK) digestion [32–34]. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) studies involving different prion strains [36,38,39], conformation dependent immunoassays [36,40] and atomic force microscopy of synthetic prion protein polymers [41] confirm the hypothesis that differences between prion strains lies in the diversity of structures that PrPSc can acquire. However, the definitive proof for the structural nature of the differences between prion strains is still missing.

Figure 1. PrPSc western blot profiles associated to different strains of human prions.

Schematic representation of human PrPSc types after PK digestion. Particular polymorphic groups in position 129 are associated with specific PrPSc patterns. Types 1 and 2 are associated with sCJD, type 3 is mostly associated with iCJD and type 4 is found exclusively in vCJD.

III. Species barrier and generation of new prion strains

The principal source of strain diversity arise from interspecies infection [23,42–45]. One of the characteristics of the agent responsible for prion diseases is its ability to infect some species and not others. This phenomenon is known as “species barrier” and is manifested as the prolongation in the incubation periods when prions from one species are used to infect a different one [46,47]. Differences in the sequence of prion protein could lead to different conformations, explaining both, species barrier and diversity of PrPSc conformations [41,48–50]. In some species, PrPC conformation does not permit conversion by prions coming from other species. A clear example of this is found in rabbit, an animal that has been unable to be infected by various sources of prions. In these cases, it is considered that the species barrier is absolute.

Interspecies prion transmission from cattle to human is probably the most relevant problem in terms of public health [51–53]. It is widely accepted that consumption of BSE infected material is the cause of vCJD in humans [27,54]. Strikingly, vCJD is a very different strain of prions than the previously known human strains, arisen sporadically. Differences between vCJD and sCJD include the clinical manifestation of the disease, the profile of brain damage and the biochemical features of PrPSc [55]. The BSE epidemic in the United Kingdom demonstrated how dangerous prions could be. So far, BSE is the only non-human prion described to be transmissible to humans. Despite the fact that people have consumed for centuries sheep potentially affected by scrapie, no correlation has been found between patients suffering by CJD and sheep consumption. Scrapie transmissibility experiments using transgenic animal models expressing chimeric human/mouse PrP support this assumption [56].

BSE has not only been transmitted to humans. The extensive use of cow-derived material for feeding other animals led to the generation of new diseases in exotic felines such as tiger and cheetah, non human primates, and domestic cats [52,57–60]. As it was mentioned before, the transmission of BSE into these different species could create many new prion strains, each one of them with particular biological and biochemical characteristics and thus a potentially new hazard for human health. Successful transmission of BSE in pigs has been described [61,62] and also in transgenic mice expressing pig PrP (PoPrP) [63]. Porcine derivates are widely consumed and the hypothetic case of “mad pigs” could increase the events of zoonotic transmission of prions to humans. Fortunately, transmission of BSE to pigs is possible only in very drastic conditions, not likely to be occurring naturally [62,63]. More frightening is perhaps the possibility that BSE has been passed into sheep and goats. Studies have already shown that this transmission is possible and actually relatively easy and worrisomely produces a disease clinically similar to scrapie [64]. The cattle origin of this new scrapie makes possible that the new strain may be transmissible to humans. Transmission experiments of BSE infected sheep brain homogenate into human transgenic animal models are currently ongoing in several laboratories. It is very important to note that all materials generated by transmission of BSE in experimental and natural cases show similar biochemical behavior compared to the original inoculum [65], suggesting that all these new generated infectious agents could potentially be hazardous for humans. The origin of BSE is still a mystery. Abundant evidence supports the hypothesis that BSE was produced by cattle feeding with scrapie derivated material [66,67], indicating that bovine PrPSc might be a “conformational intermediary” between ovine PrPSc and human PrPC.

There is currently no mean to predict which will be the conformation of a newly generated strain and how this new PrPSc conformation could affect other species. One interesting new prion disease is CWD, a disease affecting farm and wild species of cervids [68,69]. The origin of CWD and its potential to transmit to humans are currently unknown. This is worrisome, considering that CWD has became endemic in some parts of USA and the number of cases continues to increase [69]. It is presumed that a large number of hunters in the US have been in contact or consumed CWD-infected meat [70]. CWD transmissibility studies have been performed in many species in order to predict how this disease could be spread by consumption of CWD meat [71–73]. In these studies, a special attention has been done to scavenging animals [74], which are presumed to be exposed to high concentration of cervid prions, resulting in the putative generation of many new forms of TSEs. Fortunately negative results were obtained in one experiment done in raccoons infected with CWD [74]. Transmission of CWD to humans cannot be ruled out at present and a similar infective episode to BSE involving CWD could result in catastrophic events, spreading the disease in a very dangerous way through the human population. No clinical evidence linking CWD exposed humans and CJD patients have been found [70], but experimental inoculation of CWD prions into squirrel monkeys propagated the disease [71]. It is important to mention that the species barrier between humans and cervids appears to be greater than with cattle, as judged by experiments with transgenic mice models [75]. Finally, it is important to be aware about CWD transmissibility to other species in which a “conformational intermediary” could be formed, facilitating human infection.

IV. Use of experimental animals to study prion strains

Probably the best way to study the strain phenomenon is to use experimental animals for the generation of diverse strains through inoculation with prion infectious material coming from different species. Among the experimental models, perhaps mouse is the most useful one, in which more than 20 phenotypically distinct strains have been isolated [19]. Many of these strains have their origin in the transmission of different sources of scrapie from goat and sheep, BSE derived material from cattle [23,24,76] and human sources as sCJD and GSS [44,77,78]. Serial passage of infectious prions in one species, with constant biological background is necessary to stabilize and define a prion strain.

PrPSc obtained from mouse adapted scrapie prion strains such as RML, ME7, 139A and 79A show similar electrophoretical characteristics after PK digestion. All PrPSc coming from these strains show an electrophoretical mobility of ~21 KDa for the unglycosylated band and a similar glycosylation pattern, with the monoglycosilated form as the most abundant [79–83]. Despite the lack of biochemical differences, these strains can be differentiated when inoculated in mice by measuring the incubation time or the profile of brain lesions [25,28,82,84]. Other mouse strains have been generated by inoculation of animals with BSE and sCJD prions, leading to strains termed 301C and Fukuoka, respectively [42,43,85]. The transmission of BSE into mice generated two different phenotypes: one presenting PK resistant isoform of PrPSc, and another lacking this characteristic [76]. This phenotype is maintained after two serial passages in mice, but finally only the PK resistance phenotype remains. The presence of a PK sensitive infectious material (termed sPrPSc) has been also described in some cases of human prion diseases [86,87]. At this time, the isolation of a protease sensitive form of infectious prions has not been successful.

The characteristics of mouse strains generated from scrapie or from BSE are quite different. For example, intracerebral inoculation of RML strain into mice present an onset of ~150 days post inoculation (dpi), while 301C preparations cause the disease at ~200 dpi [19,88]. Intraperitoneal inoculation of RML and 301C material in the same animals shows a larger difference in the incubation periods: 200 and 300 dpi, respectively [24,84]. There are also differences in the brain affected areas by both mouse adapted prions (Castilla J., Morales R., Saá P., and Soto C.; unpublished data). In addition, it is also possible to find biochemical differences between RML and 301C strains. As mentioned above, PK digestion pattern of RML shows an electrophoretical mobility of ~21 KDa for the unglycosylated band and is rich in the monoglycosilated isoform of prion protein. In contrast, 301C prion strain show a different electrophoretical pattern compared to RML. Unglycosilated isoform of BSE adapted mouse strain shows an electrophoretical mobility of ~19 KDa and its glycoform distribution favors the diglycosylated isoform [83].

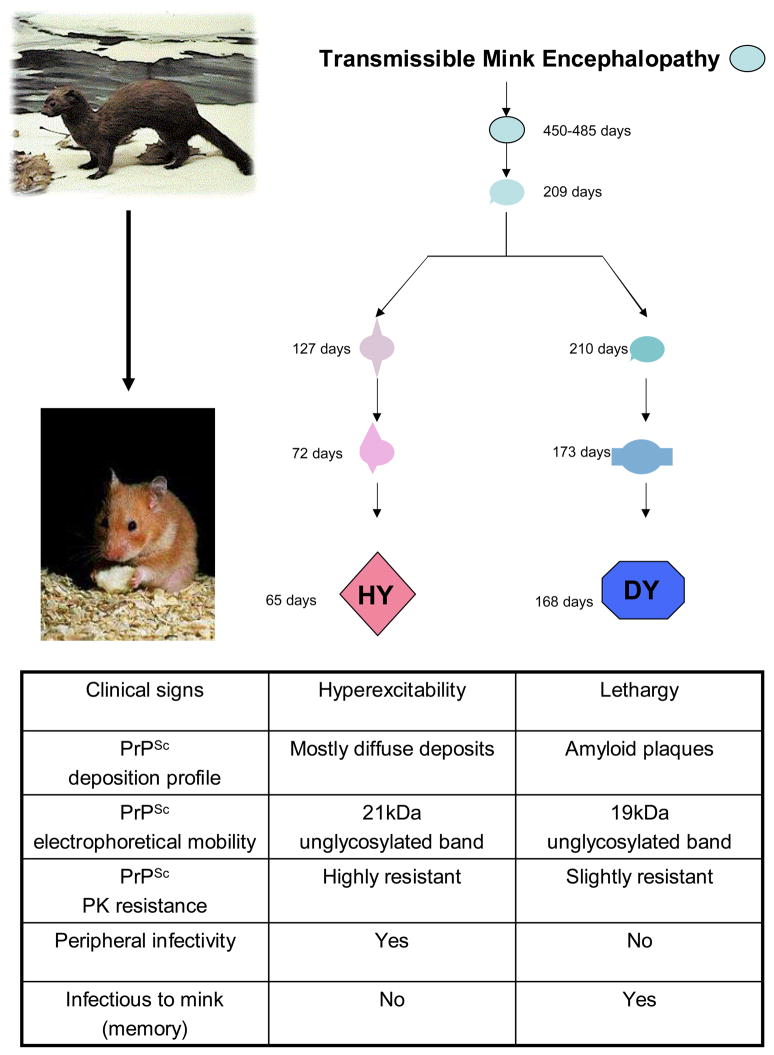

How different PrPSc conformations could induce stable conformational changes in the same host protein is still unknown. Even more interesting is the isolation of different prion strains into the same host after inoculation of PrPSc from a single species. Probably the most representative experience is the isolation of DY and HY strains after inoculation of the agent associated to transmissible mink encephalopathy (TME) in Syrian hamsters (Fig. 2) [13,16]. This interspecies transmission of prions presented the expected behavior of the species barrier phenomenon: a long incubation period in the first passage, but shorter incubation periods after inoculation of serial passages from the resulting infectious material into Syrian hamsters. Incubation periods became stable in two different groups with different clinical signs: the first one with an incubation period of ~150 dpi presented lethargy, while a shorter incubation period strain (~60 dpi) presented hyperactivity. These strains were called Drowsy (DY) and Hyper (HY) respectively according to their clinical signs [16]. Histhopathological analysis of animal groups infected with both TME hamster adapted agents show differences in the vacuolation distribution among different brain regions [16] and also in the PrPSc deposition areas [89] (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Origin and properties of the HY and DY prion strains in hamsters.

The Hyper (HY) and Drowsy (DY) scrapie strains were generated upon serial passage of transmissible mink encephalopathy (TME) infectious material in Syrian hamsters. The initial passage resulted in a very large incubation period that was upon successive passage stabilized in two different strains exhibiting strikingly different clinical, neuropathological, biochemical and infectious properties. The HY and DY hamster strains represent a prototype example of strain diversity without changes in amino acid sequence of the prion protein.

As 301C and RML in mouse, DY and HY present differences in their electrophoretical mobility after PK treatment. The unglycosylated band of DY has a molecular weight of 19 KDa, while HY show the same band at 21 KDa [32,90]. This is the most direct evidence that suggested conformational differences between both PrPSc species. Supporting this assumption, structural differences using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) between both Syrian hamster adapted TME strains were found [38]. Another biochemical difference found between DY and HY lies in their differential resistance to PK digestion, where DY is the most sensitive to digestion compared to HY [32] (Fig. 2). All these biological and biochemical characteristics make DY and HY one of the most intriguing examples of prion strain variation.

V. Polymorphisms and prion strains

Polymorphisms in the prion protein and their effects in the prion strain phenomenon were indirectly described a long time before the prion hypothesis was developed [15]. Differences in prion pathology were found and extensively described in sheep and mice [17–19,25]. The drowsy and scratchy phenotypes found in sheep were attributed to polymorphic differences in the infectious agent inoculated in experimental animals [17]. The identification of “scrapie incubation period gene” (sinc) and its polymorphic differences was a very big hit in the study of prion strains [91]. In mouse, two polymorphic animal groups were originally described: sincs7 and sincp7. Later, it was discovered that the sinc gene was indeed the gene encoding PrP and the polymorphisms resulted in differences in the prion protein at positions 108 and 189 [92]. The transmission of infectious agents from sheep, goats and cattle to both mice groups resulted in the emergence of a wide diversity of prion strains [19,28]. When incubation periods of mouse adapted prions were stabilized in each group, new generated infectious agent could be assayed in the other animal group. It was found that the presence of the polymorphism produced a prolongation in the incubation period in a similar way as observed in the species barrier phenomenon [19]. It was postulated that prion strains in mouse could be differentiated inoculating infectious material in both animals’ types and identifying the short and long incubation period animal cluster [19]. Interestingly, when a mouse prion strain is inoculated in sinc heterozygous animals, either intermediate or longer incubation periods are observed [28]. Inter-polymorphic transmissions can lead to the generation of new prion strains [19], which implies new vacuolation, infectivity and/or dominance characteristics, among others. All this information suggests that polymorphisms in the prion protein are able to favor strain diversity. Table 1 shows mice and prion strains corresponding to each polymorphic group.

Table 1. Polymorphisms associated to prion diversity in mouse.

The table shows different mouse strain and prion strains isolated in each polymorphic group.

| Mouse prnp genotype | Mouse strain | Prion strains | Associated polymorphisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| prnpa/sincs7 | C57

RIII Swiss NZW SJL |

RML - ME7 - 139A-301C- 22C - 79A - 87A- | Leu-108

Thr-189 |

| prnpb/sincp7 | VM

IM I/Ln |

301V-22A- S7V - 79V - | Phe-108

Val-189 |

| prnpc | Mai/Pas<C57. MAI-Prnp | Phe-108

Thr-189 |

After the prion hypothesis development and isolation of prion protein gene [93], it was described that sinc and prnp genes were congruent [94]. Analysis of long and short incubation period animal groups revealed the expected polymorphic differences in the prion protein gene [21]. These findings strongly supports the prion hypothesis, because as observed in the species barrier phenomenon, differences in the sequence of the prion protein affect extensively the transmission and strain characteristics of the infectious agent. According to a new nomenclature generated, sincs7 animals are re-baptized as prnpa, while sincp7 as prnpb [21]. Recently a new group of mice have been identified and named prnpc (Table 1) [88].

PrP polymorphisms are not unique of mouse. Indeed, polymorphisms in the prion protein have been described in most of the species. In sheep, several inter-bred crosses have been performed in order to optimize the quality and productivity of these animals, producing a wide range of polymorphic variants for prnp [18]. However, only five alleles of the PrP gene are significantly present giving a total of 15 possible PrP genotypes, each likely to favor or disfavor the selection of different scrapie strains [18]. These five common polymorphic alleles are ARQ, ARR, AHQ, ARH and VRQ. Polymorphic changes are present principally in codons 136, 154 and 171, but in order to simplify the nomenclature they are designated by the amino acid present in each position. In a recent revision by Baylis and Goldman [18] it is documented that VRQ/VRQ, ARH/VRQ and ARQ/VRQ alleles are most susceptible for sheep to develop scrapie, whereas the less vulnerable are animals having ARR/ARR, ARR/ARH and AHQ/ARH alleles. Therefore, it is generally agree that the VRQ allele promotes susceptibility to scrapie, whereas ARR diminishes the manifestation of the disease. Interestingly, other alleles such as ARH alone appear to favor the development of the disease while in combination with other alleles appear to confer resistance. In the same study, a correlation was established between incubation periods and the type of polymorphism. A linear relationship between age of death and five polymorphic groups was observed. Many prion strains have been described for scrapie. Each strain is associated to a particular allelic group, and allelic groups are associated to a particular breed of animals [42,95]. However, as previously described, prion protein diversity could exist with the same sequence in the prion protein and sheep is not the exception. CH1641, a prion strain with clear biochemical differences compared to other scrapie strains was isolated from a natural case of scrapie in Cheviot sheep [96]. Recently a new scrapie strain designated Nor98 has been described [95], mostly in animals having AHQ/AHQ and AHQ/ARQ genotypes (a variation relatively resistant to scrapie). In this case, “classically susceptible” alleles seem to be resistant for this class of prions [18,97]. All this information arise questions about how natural cases of scrapie are developed.

In humans there is a polymorphism at codon 129, where an ATG or GTG results in either a methionine (Met) or a valine (Val) at that position. A large body of evidence indicates that this polymorphism alone or in conjunction with mutations in the prion gene modulates disease susceptibility and phenotypic expression of human TSE [2,98,98–104]. Both Met and Val homozygous are over-represented, while heterozygous cases are under-represented in sCJD [98,99,105]. About 40% of the normal population is Met-homozygous, however 78%, 50% and 100% of patients affected by the sporadic, iatrogenic and variant forms of CJD are Met-homozygous, respectively [105–109]. These data suggest that the presence of Met at position 129 confers a higher susceptibility for the protein to be converted into the pathogenic isoform. The polymorphism has also been shown to alter the neuropathological pattern of lesions in sporadic CJD, the glycoform profile of protease-resistant PrPSc and the duration and severity of the disease [34,102,103,110–113]. A study involving 300 patients showed that Met-homozygous develop a more aggressive phenotype characterized by a short duration of disease (4.5 months), while heterozygous and Val-homozygous have a much longer disease duration (14.3 and 16.9 months, respectively) [103]. Val-homozygous seems to cause damage preferentially in the deep gray matter, while Met-homozygous seems to target mainly cortical structures [103]. Codon 129 polymorphism also influences the phenotypic expression of mutations elsewhere in the prion gene [104,114–119]. For example, people with a mutation at codon 178 resulting in a change of aspartic acid to asparagine develop either familial CJD or FFI depending on whether the amino acid at codon 129 is Val or Met, respectively [104].

Despite the clear importance of PrP polymorphism at position 129 in the disease propensity and pathogenesis, the molecular mechanism of this effect is unknown. Experimental and computational modeling studies of the tridimensional structure of PrP have been unable to identify any significant difference between the two isoforms [120]. In addition, no difference was reported on the in vitro thermodynamic stability of recombinant PrP bearing either Met or Val at position 129 [120,121]. Structural studies show evidence for hydrogen bonding between Asp178 and Tyr128, which might provide a structural basis for the influence of the polymorphism on the disease phenotype that segregates with the mutation Asp178Asn [121]. In addition, it has been reported that a slightly different conformation of recombinant Met- or Val-containing PrP isoforms was induced upon copper binding [122]. Using short model peptides, we found that M at position 129 increases the propensity of this region to aggregate into β-sheet rich fibrillar structures [123]. These findings were interpreted to suggest that Met induces a higher local propensity to extend the short β-sheet present in the normal protein into a larger sheet, which results in an increase in the rate of PrP conversion to the pathological isoform [123].

VI. Unique features of prion strains

The biological and infectious characteristics of prions are dramatically different to the conventional infectious agents. These differences are manifested in the prion strains phenomenon in unique and unprecedented features, such as for example strain adaptation and memory, the coexistence and competition of prion strains, among others. In this section, some of these interesting phenomena will be briefly described.

Adaptation of Prion strains

Interspecies transmission of prions could result in the emergence of more than one variety of infectious material. All new collected infectious agents could present particular strain characteristics. That is the case of DY and HY prion strains generation [13,16]. When interspecies transmission of prions occurs, serial passages in the new host are needed in order to stabilize the characteristics of new generated infectious material. In the case of TME transmission in hamsters, at least four serial passages in the new species were required for stabilization [13]. The first passage was characterized by long incubation periods and a dominance of a 19 KDa fragment when newly obtained PrPSc was analyzed after PK digestion. In the three first passages, clinical symptoms were not characteristic of the hamster-adapted HY or DY TME strains. This phenotype was attributed to the combination effects of both strains replicating simultaneously. Thereafter, each of the strains was stabilized in some of the animals and once they are adapted and stabilized, they can be serially propagated in vivo and the characteristics are maintained. It is accepted that both strains present differential conversion kinetics in vitro, with DY being the slowest and HY the fastest [124]. For this reason, in order to select efficiently this prion strain, limit dilutions must be performed [13]. In that way, the most abundant and less convertible DY is favored against the less abundant but fastest HY strain.

Co-existence of prion strains

Related to the above, it has been shown that two or more prion strains can co-exist in natural cases of TSE. Co-existence of prion strains has been found in sporadic cases of CJD [113,125]. Analyses of several sCJD tissue showed that different biochemical profiles of PrPSc could be found in different brain areas from the same patient [113]. Co-existence of prion strains was mainly observed in patient heterozygous for codon 129 [113]. As many as 50% of these patients present different types of PrPSc in their brains, whereas 9% of MM patients were positive for co-existence of strains. On the other hand, more than one PrPSc type was not observed in VV patients [113].

The biochemical and structural properties of the protein seem to be the major cause of this differential distribution. This observation may explain why sCJD is so heterogeneous in terms of clinical manifestation [34,126,127]. In a recent publication by Bishop et al. [107], vCJD infected transgenic mice expressing human PrPC, present changes in their PrPSc and vacuolation patterns in the brain according to their polymorphic classification for codon 129.

Competition of prion strains

In particular experimental conditions, some prion strains can extend their specific incubation period when co-infected with another strain. Long incubation period prions increase the incubation period of “faster” prions. This phenomenon of “competition of prion strains” has been observed in mice and hamster. In mice, competition between 22A and 22C strains was reported in 1975 by Dickinson et al. [128]. In this study, RIII mice (homozygous for sincs7 allele) were used. 22A and 22C showed long and short incubation period (550 and 230 days), respectively. When 22C strain was intraperitoneally inoculated 100, 200 and 300 days after intraperitoneal administration of the 22A agent, all three experimental groups resulted in incubation periods and lesion patterns matching 22A prions, suggesting that 22C prions were degraded or excreted, in animals previously infected by 22A. Similar results were obtained by Kimberlin and Walker in 1985 [129] using a different strain of sincs7 mice. These authors treated mice using 22A and 22C prion strain. Before inoculation, 22A was treated with different chemical and physical agents in order to see if the “competitor” or “blocking” characteristics of 22A were maintained. From all treatments, 12M urea was shown to almost abolish the blocking properties of 22A agent. This information suggests that infective properties of long incubation period agent are strictly necessary in order to increase the incubation period of faster prions.

In hamster, similar observations were reported using DY and HY [130]. DY prion strain was inoculated 30 and 60 days prior intraperitoneal inoculation of HY at three different doses. When incubation periods of HY inoculated control group were compared with the animals inoculated at 60 days with DY, significant differences in the incubation periods were found, especially when HY prions were administrated in a higher dose [130]. On the other hand no differences were observed in the case of intranerve inoculation, revealing that competition phenomenon occurs only when peripheral inoculation is performed. These results are surprising considering the fact that DY was reported not to be infectious when intraperitoneally inoculated in hamsters [130]. This data suggest that replication of DY is occurring in peripheral tissues but is not able to reach the central nervous system.

In general, the principal variables that need to be observed for a successful competition are the route of infection, the interval between injections and the particular strains and doses of agent used. Prolongation of incubation periods in TSE are therapeutically beneficial and several strategies are under development to reach this aim, including antibodies, beta-sheet breakers, and other chemical agents [131–133]. The experimental evidence described above suggests that prions could be potentially useful for this purpose. In order to prevent spread of prion disease in cattle or humans, prion strains with incubation periods longer than species’ lifespan could be used to slowdown the replication of BSE or vCJD prions.

VII. Concluding Remarks

The existence of different strains of an infectious agent composed exclusively of a protein has been one of the most puzzling issues in the prion field. If is already difficult to understand how a protein can adopt two stable and different folded structures and that one of them can transform the other one into itself, it is unthinkable that the misfolded form can in turn adopt multiple conformations with distinct properties. Yet, compelling scientific evidence support the idea that PrP can adopt numerous folding patterns that can faithfully replicate and produce different diseases. The existence of the strain phenomenon is not only a scientific challenge, but it also represents a serious risk for public health. The dynamic nature and inter-relations between strains and the potential for the generation of many new prion strains depending on the polymorphisms and the crossing of species barrier is the perfect recipe for the emergence of extremely dangerous new infectious agents. Although, substantial progress has been made in understanding the prion strains phenomenon, there are many open questions that need urgent answers, including: what are the structural basis of prion strains?; how are the phenomena of strain adaptation and memory enciphered in the conformation of the prion agent?; to what species can a given prion strain be transmissible?; what other cellular factors control the origin and properties of prion strains?.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by NIH grant NS049173.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Prusiner SB. Prions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:13363–13383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collinge J. Prion diseases of humans and animals: their causes and molecular basis. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:519–550. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Budka H, Aguzzi A, Brown P, Brucher JM, Bugiani O, Gullotta F, Haltia M, Hauw JJ, Ironside JW, Jellinger K. Neuropathological diagnostic criteria for Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) and other human spongiform encephalopathies (prion diseases) Brain Pathol. 1995;5:459–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1995.tb00625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soto C. Unfolding the role of protein misfolding in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:49–60. doi: 10.1038/nrn1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen CH, Valleron AJ. When did bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) start? Implications on the prediction of a new variant of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (nvCJD) epidemic. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28:526–531. doi: 10.1093/ije/28.3.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghani AC, Ferguson NM, Donnelly CA, Hagenaars TJ, Anderson RM. Estimation of the number of people incubating variant CJD. Lancet. 1998;352:1353–1354. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)60744-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Will R. Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Folia Neuropathol. 2004;42(Suppl A):77–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Griffith JS. Self-replication and scrapie. Nature. 1967;215:1043–1044. doi: 10.1038/2151043a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen FE, Prusiner SB. Pathologic conformations of prion proteins. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:793–819. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prusiner SB, Groth DF, Bolton DC, Kent SB, Hood LE. Purification and structural studies of a major scrapie prion protein. Cell. 1984;38:127–134. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90533-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chesebro B. BSE and prions: uncertainties about the agent. Science. 1998;279:42–43. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5347.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soto C, Castilla J. The controversial protein-only hypothesis of prion propagation. Nat Med. 2004;10:S63–S67. doi: 10.1038/nm1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bartz JC, Bessen RA, McKenzie D, Marsh RF, Aiken JM. Adaptation and selection of prion protein strain conformations following interspecies transmission of transmissible mink encephalopathy. J Virol. 2000;74:5542–5547. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.12.5542-5547.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peretz D, Scott MR, Groth D, Williamson RA, Burton DR, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB. Strain-specified relative conformational stability of the scrapie prion protein. Protein Sci. 2001;10:854–863. doi: 10.1110/ps.39201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pattison IH, Millson GC. Scrapie produced experimentally in goats with special reference to the clinical syndrome. J Comp Pathol. 1961;71:101–109. doi: 10.1016/s0368-1742(61)80013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bessen RA, Marsh RF. Identification of two biologically distinct strains of transmissible mink encephalopathy in hamsters. J Gen Virol. 1992;73(Pt 2):329–334. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-2-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dickinson AG. Scrapie in sheep and goats. Front Biol. 1976;44:209–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baylis M, Goldmann W. The genetics of scrapie in sheep and goats. Curr Mol Med. 2004;4:385–396. doi: 10.2174/1566524043360672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bruce ME. Scrapie strain variation and mutation. Br Med Bull. 1993;49:822–838. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a072649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fraser H. Diversity in the neuropathology of scrapie-like diseases in animals. Br Med Bull. 1993;49:792–809. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a072647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Westaway D, Goodman PA, Mirenda CA, McKinley MP, Carlson GA, Prusiner SB. Distinct prion proteins in short and long scrapie incubation period mice. Cell. 1987;51:651–662. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90134-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bruce ME, McBride PA, Farquhar CF. Precise targeting of the pathology of the sialoglycoprotein, PrP, and vacuolar degeneration in mouse scrapie. Neurosci Lett. 1989;102:1–6. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(89)90298-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bruce ME, Boyle A, Cousens S, McConnell I, Foster J, Goldmann W, Fraser H. Strain characterization of natural sheep scrapie and comparison with BSE. J Gen Virol. 2002;83:695–704. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-3-695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lasmezas CI, Deslys JP, Demaimay R, Adjou KT, Hauw JJ, Dormont D. Strain specific and common pathogenic events in murine models of scrapie and bovine spongiform encephalopathy. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:1601–1609. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-7-1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fraser H, Dickinson AG. Scrapie in mice. Agent-strain differences in the distribution and intensity of grey matter vacuolation. J Comp Pathol. 1973;83:29–40. doi: 10.1016/0021-9975(73)90024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scott MR, Will R, Ironside J, Nguyen HO, Tremblay P, DeArmond SJ, Prusiner SB. Compelling transgenetic evidence for transmission of bovine spongiform encephalopathy prions to humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:15137–15142. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bruce ME, Will RG, Ironside JW, McConnell I, Drummond D, Suttie A, McCardle L, Chree A, Hope J, Birkett C, Cousens S, Fraser H, Bostock CJ. Transmissions to mice indicate that ‘new variant’ CJD is caused by the BSE agent. Nature. 1997;389:498–501. doi: 10.1038/39057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bruce ME, McConnell I, Fraser H, Dickinson AG. The disease characteristics of different strains of scrapie in Sinc congenic mouse lines: implications for the nature of the agent and host control of pathogenesis. J Gen Virol. 1991;72:595–603. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-3-595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dickinson AG, Meikle VM, Fraser H. Identification of a gene which controls the incubation period of some strains of scrapie agent in mice. J Comp Pathol. 1968;78:293–299. doi: 10.1016/0021-9975(68)90005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dell’Omo G, Vannoni E, Vyssotski AL, Di Bari MA, Nonno R, Agrimi U, Lipp HP. Early behavioural changes in mice infected with BSE and scrapie: automated home cage monitoring reveals prion strain differences. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16:735–742. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cunningham C, Deacon RM, Chan K, Boche D, Rawlins JN, Perry VH. Neuropathologically distinct prion strains give rise to similar temporal profiles of behavioral deficits. Neurobiol Dis. 2005;18:258–269. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bessen RA, Marsh RF. Biochemical and physical properties of the prion protein from two strains of the transmissible mink encephalopathy agent. J Virol. 1992;66:2096–2101. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.4.2096-2101.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Collinge J, Sidle KC, Meads J, Ironside J, Hill AF. Molecular analysis of prion strain variation and the aetiology of ‘new variant’ CJD. Nature. 1996;383:685–690. doi: 10.1038/383685a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parchi P, Castellani R, Capellari S, Ghetti B, Young K, Chen SG, Farlow M, Dickson DW, Sima AA, Trojanowski JQ, Petersen RB, Gambetti P. Molecular basis of phenotypic variability in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Ann Neurol. 1996;39:767–778. doi: 10.1002/ana.410390613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khalili-Shirazi A, Summers L, Linehan J, Mallinson G, Anstee D, Hawke S, Jackson GS, Collinge J. PrP glycoforms are associated in a strain-specific ratio in native PrPSc. J Gen Virol. 2005;86:2635–2644. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80375-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Safar J, Wille H, Itri V, Groth D, Serban H, Torchia M, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB. Eight prion strains have PrP(Sc) molecules with different conformations. Nat Med. 1998;4:1157–1165. doi: 10.1038/2654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wadsworth JD, Hill AF, Joiner S, Jackson GS, Clarke AR, Collinge J. Strain-specific prion-protein conformation determined by metal ions. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:55–59. doi: 10.1038/9030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Caughey B, Raymond GJ, Bessen RA. Strain-dependent differences in beta-sheet conformations of abnormal prion protein. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:32230–32235. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.48.32230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aucouturier P, Kascsak RJ, Frangione B, Wisniewski T. Biochemical and conformational variability of human prion strains in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Neurosci Lett. 1999;274:33–36. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00659-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bellon A, Seyfert-Brandt W, Lang W, Baron H, Groner A, Vey M. Improved conformation-dependent immunoassay: suitability for human prion detection with enhanced sensitivity. J Gen Virol. 2003;84:1921–1925. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.18996-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jones EM, Surewicz WK. Fibril conformation as the basis of species- and strain-dependent seeding specificity of mammalian prion amyloids. Cell. 2005;121:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bruce M, Chree A, McConnell I, Foster J, Pearson G, Fraser H. Transmission of bovine spongiform encephalopathy and scrapie to mice: strain variation and the species barrier. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1994;343:405–411. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1994.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fraser H, Bruce ME, Chree A, McConnell I, Wells GA. Transmission of bovine spongiform encephalopathy and scrapie to mice. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:1891–1897. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-8-1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Muramoto T, Kitamoto T, Tateishi J, Goto I. Successful transmission of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease from human to mouse verified by prion protein accumulation in mouse brains. Brain Res. 1992;599:309–316. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90406-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hill AF, Collinge J. Prion strains and species barriers. Contrib Microbiol. 2004;11:33–49. doi: 10.1159/000077061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peretz D, Williamson RA, Legname G, Matsunaga Y, Vergara J, Burton DR, DeArmond SJ, Prusiner SB, Scott MR. A change in the conformation of prions accompanies the emergence of a new prion strain. Neuron. 2002;34:921–932. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00726-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moore RA, Vorberg I, Priola SA. Species barriers in prion diseases--brief review. Arch Virol. 2005;(Suppl):187–202. doi: 10.1007/3-211-29981-5_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vanik DL, Surewicz KA, Surewicz WK. Molecular basis of barriers for interspecies transmissibility of mammalian prions. Mol Cell. 2004;14:139–145. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00155-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Prusiner SB, Scott M, Foster D, Pan KM, Groth D, Mirenda C, Torchia M, Yang SL, Serban D, Carlson GA. Transgenetic studies implicate interactions between homologous PrP isoforms in scrapie prion replication. Cell. 1990;63:673–686. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90134-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen SG, Gambetti P. A journey through the species barrier. Neuron. 2002;34:854–856. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00736-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smith PG, Bradley R. Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) and its epidemiology. Br Med Bull. 2003;66:185–198. doi: 10.1093/bmb/66.1.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Collee JG, Bradley R. BSE: a decade on--Part I. Lancet. 1997;349:636–641. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)01310-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Collee JG, Bradley R. BSE: a decade on--Part 2. Lancet. 1997;349:715–721. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)08496-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hill AF, Desbruslais M, Joiner S, Sidle KC, Gowland I, Collinge J, Doey LJ, Lantos P. The same prion strain causes vCJD and BSE. Nature. 1997;389:448–50. 526. doi: 10.1038/38925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Collinge J. Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Lancet. 1999;354:317–323. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)05128-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gombojav A, Shimauchi I, Horiuchi M, Ishiguro N, Shinagawa M, Kitamoto T, Miyoshi I, Mohri S, Takata M. Susceptibility of transgenic mice expressing chimeric sheep, bovine and human PrP genes to sheep scrapie. J Vet Med Sci. 2003;65:341–347. doi: 10.1292/jvms.65.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kirkwood JK, Cunningham AA. Epidemiological observations on spongiform encephalopathies in captive wild animals in the British Isles. Vet Rec. 1994;135:296–303. doi: 10.1136/vr.135.13.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pearson GR, Wyatt JM, Gruffydd-Jones TJ, Hope J, Chong A, Higgins RJ, Scott AC, Wells GA. Feline spongiform encephalopathy: fibril and PrP studies. Vet Rec. 1992;131:307–310. doi: 10.1136/vr.131.14.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Taylor DM, Woodgate SL. Bovine spongiform encephalopathy: the causal role of ruminant-derived protein in cattle diets. Rev Sci Tech. 1997;16:187–198. doi: 10.20506/rst.16.1.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bons N, Mestre-Frances N, Belli P, Cathala F, Gajdusek DC, Brown P. Natural and experimental oral infection of nonhuman primates by bovine spongiform encephalopathy agents. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:4046–4051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.4046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ryder SJ, Hawkins SA, Dawson M, Wells GA. The neuropathology of experimental bovine spongiform encephalopathy in the pig. J Comp Pathol. 2000;122:131–143. doi: 10.1053/jcpa.1999.0349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wells GA, Hawkins SA, Austin AR, Ryder SJ, Done SH, Green RB, Dexter I, Dawson M, Kimberlin RH. Studies of the transmissibility of the agent of bovine spongiform encephalopathy to pigs. J Gen Virol. 2003;84:1021–1031. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.18788-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Castilla J, Gutierrez-Adan A, Brun A, Doyle D, Pintado B, Ramirez MA, Salguero FJ, Parra B, Diaz SS, Sanchez-Vizcaino JM, Rogers M, Torres JM. Subclinical bovine spongiform encephalopathy infection in transgenic mice expressing porcine prion protein. J Neurosci. 2004;24:5063–5069. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5400-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Foster JD, Hope J, Fraser H. Transmission of bovine spongiform encephalopathy to sheep and goats. Vet Rec. 1993;133:339–341. doi: 10.1136/vr.133.14.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stack MJ, Chaplin MJ, Clark J. Differentiation of prion protein glycoforms from naturally occurring sheep scrapie, sheep-passaged scrapie strains (CH1641 and SSBP1), bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) cases and Romney and Cheviot breed sheep experimentally inoculated with BSE using two monoclonal antibodies. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2002;104:279–286. doi: 10.1007/s00401-002-0556-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wilesmith JW, Wells GA, Cranwell MP, Ryan JB. Bovine spongiform encephalopathy: epidemiological studies. Vet Rec. 1988;123:638–644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wilesmith JW, Ryan JB, Atkinson MJ. Bovine spongiform encephalopathy: epidemiological studies on the origin. Vet Rec. 1991;128:199–203. doi: 10.1136/vr.128.9.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sigurdson CJ, Miller MW. Other animal prion diseases. Br Med Bull. 2003;66:199–212. doi: 10.1093/bmb/66.1.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Williams ES. Chronic wasting disease. Vet Pathol. 2005;42:530–549. doi: 10.1354/vp.42-5-530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Belay ED, Gambetti P, Schonberger LB, Parchi P, Lyon DR, Capellari S, McQuiston JH, Bradley K, Dowdle G, Crutcher JM, Nichols CR. Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in unusually young patients who consumed venison. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:1673–1678. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.10.1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Marsh RF, Kincaid AE, Bessen RA, Bartz JC. Interspecies Transmission of Chronic Wasting Disease Prions to Squirrel Monkeys (Saimiri sciureus) J Virol. 2005;79:13794–13796. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.21.13794-13796.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hamir AN, Cutlip RC, Miller JM, Williams ES, Stack MJ, Miller MW, O’Rourke KI, Chaplin MJ. Preliminary findings on the experimental transmission of chronic wasting disease agent of mule deer to cattle. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2001;13:91–96. doi: 10.1177/104063870101300121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hamir AN, Kunkle RA, Cutlip RC, Miller JM, O’Rourke KI, Williams ES, Miller MW, Stack MJ, Chaplin MJ, Richt JA. Experimental transmission of chronic wasting disease agent from mule deer to cattle by the intracerebral route. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2005;17:276–281. doi: 10.1177/104063870501700313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hamir AN, Miller JM, Cutlip RC, Stack MJ, Chaplin MJ, Jenny AL, Williams ES. Experimental inoculation of scrapie and chronic wasting disease agents in raccoons (Procyon lotor) Vet Rec. 2003;153:121–123. doi: 10.1136/vr.153.4.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kong Q, Huang S, Zou W, Vanegas D, Wang M, Wu D, Yuan J, Zheng M, Bai H, Deng H, Chen K, Jenny AL, O’Rourke K, Belay ED, Schonberger LB, Petersen RB, Sy MS, Chen SG, Gambetti P. Chronic wasting disease of elk: transmissibility to humans examined by transgenic mouse models. J Neurosci. 2005;25:7944–7949. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2467-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lasmezas CI, Deslys JP, Robain O, Jaegly A, Beringue V, Peyrin JM, Fournier JG, Hauw JJ, Rossier J, Dormont D. Transmission of the BSE agent to mice in the absence of detectable abnormal prion protein. Science. 1997;275:402–405. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5298.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Manuelidis EE, Gorgacz EJ, Manuelidis L. Transmission of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease with scrapie-like syndromes to mice. Nature. 1978;271:778–779. doi: 10.1038/271778a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tateishi J, Sato Y, Nagara H, Boellaard JW. Experimental transmission of human subacute spongiform encephalopathy to small rodents. IV. Positive transmission from a typical case of Gerstmann-Straussler-Scheinker’s disease. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1984;64:85–88. doi: 10.1007/BF00695613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kascsak RJ, Rubenstein R, Merz PA, Carp RI, Robakis NK, Wisniewski HM, Diringer H. Immunological comparison of scrapie-associated fibrils isolated from animals infected with four different scrapie strains. J Virol. 1986;59:676–683. doi: 10.1128/jvi.59.3.676-683.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rubenstein R, Merz PA, Kascsak RJ, Scalici CL, Papini MC, Carp RI, Kimberlin RH. Scrapie-infected spleens: analysis of infectivity, scrapie-associated fibrils, and protease-resistant proteins. J Infect Dis. 1991;164:29–35. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kascsak RJ, Rubenstein R, Merz PA, Carp RI, Wisniewski HM, Diringer H. Biochemical differences among scrapie-associated fibrils support the biological diversity of scrapie agents. J Gen Virol. 1985;66:1715–1722. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-66-8-1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Legname G, Nguyen HO, Baskakov IV, Cohen FE, DeArmond SJ, Prusiner SB. Strain-specified characteristics of mouse synthetic prions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409079102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Baron T, Crozet C, Biacabe AG, Philippe S, Verchere J, Bencsik A, Madec JY, Calavas D, Samarut J. Molecular analysis of the protease-resistant prion protein in scrapie and bovine spongiform encephalopathy transmitted to ovine transgenic and wild-type mice. J Virol. 2004;78:6243–6251. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.12.6243-6251.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Thackray AM, Klein MA, Bujdoso R. Subclinical prion disease induced by oral inoculation. J Virol. 2003;77:7991–7998. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.14.7991-7998.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tateishi J, Ohta M, Koga M, Sato Y, Kuroiwa Y. Transmission of chronic spongiform encephalopathy with kuru plaques from humans to small rodents. Ann Neurol. 1979;5:581–584. doi: 10.1002/ana.410050616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Collinge J, Owen F, Poulter M, Leach M, Crow TJ, Rossor MN, Hardy J, Mullan MJ, Janota I, Lantos PL. Prion dementia without characteristic pathology. Lancet. 1990;336:7–9. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)91518-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Medori R, Montagna P, Tritschler HJ, LeBlanc A, Cortelli P, Tinuper P, Lugaresi E, Gambetti P. Fatal familial insomnia: a second kindred with mutation of prion protein gene at codon 178. Neurology. 1992;42:669–670. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.3.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lloyd SE, Thompson SR, Beck JA, Linehan JM, Wadsworth JD, Brandner S, Collinge J, Fisher EM. Identification and characterization of a novel mouse prion gene allele. Mamm Genome. 2004;15:383–389. doi: 10.1007/s00335-004-3041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bessen RA, Marsh RF. Distinct PrP properties suggest the molecular basis of strain variation in transmissible mink encephalopathy. J Virol. 1994;68:7859–7868. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.7859-7868.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bessen RA, Kocisko DA, Raymond GJ, Nandan S, Lansbury PT, Caughey B. Non-genetic propagation of strain-specific properties of scrapie prion protein. Nature. 1995;375:698–700. doi: 10.1038/375698a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Dickinson AG, Meikle VM. Host-genotype and agent effects in scrapie incubation: change in allelic interaction with different strains of agent. Mol Gen Genet. 1971;112:73–79. doi: 10.1007/BF00266934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Carp RI, Moretz RC, Natelli M, Dickinson AG. Genetic control of scrapie: incubation period and plaque formation in I mice. J Gen Virol. 1987;68:401–407. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-68-2-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Carlson GA, Kingsbury DT, Goodman PA, Coleman S, Marshall ST, DeArmond S, Westaway D, Prusiner SB. Linkage of prion protein and scrapie incubation time genes. Cell. 1986;46:503–511. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90875-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hunter N, Dann JC, Bennett AD, Somerville RA, McConnell I, Hope J. Are Sinc and the PrP gene congruent? Evidence from PrP gene analysis in Sinc congenic mice. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:2751–2755. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-10-2751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Benestad SL, Sarradin P, Thu B, Schonheit J, Tranulis MA, Bratberg B. Cases of scrapie with unusual features in Norway and designation of a new type, Nor98. Vet Rec. 2003;153:202–208. doi: 10.1136/vr.153.7.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Foster JD, Parnham D, Chong A, Goldmann W, Hunter N. Clinical signs, histopathology and genetics of experimental transmission of BSE and natural scrapie to sheep and goats. Vet Rec. 2001;148:165–171. doi: 10.1136/vr.148.6.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Tranulis MA, Osland A, Bratberg B, Ulvund MJ. Prion protein gene polymorphisms in sheep with natural scrapie and healthy controls in Norway. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:1073–1077. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-4-1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Collinge J, Palmer MS, Dryden AJ. Genetic predisposition to iatrogenic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Lancet. 1991;337:1441–1442. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)93128-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Palmer MS, Dryden AJ, Hughes JT, Collinge J. Homozygous prion protein genotype predisposes to sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Nature. 1991;352:340–342. doi: 10.1038/352340a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lee HS, Brown P, Cervenakova L, Garruto RM, Alpers MP, Gajdusek DC, Goldfarb LG. Increased susceptibility to Kuru of carriers of the PRNP 129 methionine/methionine genotype. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:192–196. doi: 10.1086/317935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mead S, Stumpf MP, Whitfield J, Beck JA, Poulter M, Campbell T, Uphill JB, Goldstein D, Alpers M, Fisher EM, Collinge J. Balancing selection at the prion protein gene consistent with prehistoric kurulike epidemics. Science. 2003;300:640–643. doi: 10.1126/science.1083320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hauw JJ, Sazdovitch V, Laplanche JL, Peoc’h K, Kopp N, Kemeny J, Privat N, Delasnerie-Laupretre N, Brandel JP, Deslys JP, Dormont D, Alperovitch A. Neuropathologic variants of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and codon 129 of PrP gene. Neurology. 2000;54:1641–1646. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.8.1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Parchi P, Giese A, Capellari S, Brown P, Schulz-Schaeffer W, Windl O, Zerr I, Budka H, Kopp N, Piccardo P, Poser S, Rojiani A, Streichemberger N, Julien J, Vital C, Ghetti B, Gambetti P, Kretzschmar H. Classification of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease based on molecular and phenotypic analysis of 300 subjects. Ann Neurol. 1999;46:224–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Goldfarb LG, Petersen RB, Tabaton M, Brown P, LeBlanc AC, Montagna P, Cortelli P, Julien J, Vital C, Pendelbury WW. Fatal familial insomnia and familial Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: disease phenotype determined by a DNA polymorphism. Science. 1992;258:806–808. doi: 10.1126/science.1439789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hill AF, Joiner S, Wadsworth JD, Sidle KC, Bell JE, Budka H, Ironside JW, Collinge J. Molecular classification of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Brain. 2003;126:1333–1346. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Brandel JP, Preece M, Brown P, Croes E, Laplanche JL, Agid Y, Will R, Alperovitch A. Distribution of codon 129 genotype in human growth hormone-treated CJD patients in France and the UK. Lancet. 2003;362:128–130. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13867-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Bishop MT, Hart P, Aitchison L, Baybutt HN, Plinston C, Thomson V, Tuzi NL, Head MW, Ironside JW, Will RG, Manson JC. Predicting susceptibility and incubation time of human-to-human transmission of vCJD. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:393–398. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70413-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Aguzzi A. Prion diseases of humans and farm animals: epidemiology, genetics, and pathogenesis. J Neurochem. 2006;97:1726–1739. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Collinge J, Beck J, Campbell T, Estibeiro K, Will RG. Prion protein gene analysis in new variant cases of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Lancet. 1996;348:56. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)64378-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Glatzel M, Stoeck K, Seeger H, Luhrs T, Aguzzi A. Human prion diseases: molecular and clinical aspects. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:545–552. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.4.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Gambetti P, Kong Q, Zou W, Parchi P, Chen SG. Sporadic and familial CJD: classification and characterisation. Br Med Bull. 2003;66:213–239. doi: 10.1093/bmb/66.1.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Parchi P, Zou W, Wang W, Brown P, Capellari S, Ghetti B, Kopp N, Schulz-Schaeffer WJ, Kretzschmar HA, Head MW, Ironside JW, Gambetti P, Chen SG. Genetic influence on the structural variations of the abnormal prion protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:10168–10172. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.18.10168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Schoch G, Seeger H, Bogousslavsky J, Tolnay M, Janzer RC, Aguzzi A, Glatzel M. Analysis of Prion Strains by PrP(Sc) Profiling in Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease. PLoS Med. 2005;3:e14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Puoti G, Rossi G, Giaccone G, Awan T, Lievens PM, Defanti CA, Tagliavini F, Bugiani O. Polymorphism at codon 129 of PRNP affects the phenotypic expression of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease linked to E200K mutation. Ann Neurol. 2000;48:269–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Bianca M, Bianca S, Vecchio I, Raffaele R, Ingegnosi C, Nicoletti F. Gerstmann-Straussler-Scheinker disease with P102L-V129 mutation: a case with psychiatric manifestations at onset. Ann Genet. 2003;46:467–469. doi: 10.1016/s0003-3995(03)00017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Montagna P, Cortelli P, Avoni P, Tinuper P, Plazzi G, Gallassi R, Portaluppi F, Julien J, Vital C, Delisle MB, Gambetti P, Lugaresi E. Clinical features of fatal familial insomnia: phenotypic variability in relation to a polymorphism at codon 129 of the prion protein gene. Brain Pathol. 1998;8:515–520. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1998.tb00172.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Petersen RB, Goldfarb LG, Tabaton M, Brown P, Monari L, Cortelli P, Montagna P, Autilio-Gambetti L, Gajdusek DC, Lugaresi E. A novel mechanism of phenotypic heterogeneity demonstrated by the effect of a polymorphism on a pathogenic mutation in the PRNP (prion protein gene) Mol Neurobiol. 1994;8:99–103. doi: 10.1007/BF02780659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Cortelli P, Gambetti P, Montagna P, Lugaresi E. Fatal familial insomnia: clinical features and molecular genetics. J Sleep Res. 1999;8(Suppl 1):23–29. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.1999.00005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Hainfellner JA, Parchi P, Kitamoto T, Jarius C, Gambetti P, Budka H. A novel phenotype in familial Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: prion protein gene E200K mutation coupled with valine at codon 129 and type 2 protease-resistant prion protein. Ann Neurol. 1999;45:812–816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Liemann S, Glockshuber R. Influence of amino acid substitutions related to inherited human prion diseases on the thermodynamic stability of the cellular prion protein. Biochemistry. 1999;38:3258–3267. doi: 10.1021/bi982714g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Zahn R, Liu A, Luhrs T, Riek R, von Schroetter C, Lopez GF, Billeter M, Calzolai L, Wider G, Wuthrich K. NMR solution structure of the human prion protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:145–150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Wong BS, Clive C, Haswell SJ, Williamson RA, Burton DR, Gambetti P, Sy MS, Jones IM, Brown DR. Copper has differential effect on prion protein with polymorphism of position 129. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;269:726–731. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Petchanikow C, Saborio GP, Anderes L, Frossard MJ, Olmedo MI, Soto C. Biochemical and structural studies of the prion protein polymorphism. FEBS Lett. 2001;509:451–456. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Mulcahy ER, Bessen RA. Strain-specific Kinetics of Prion Protein Formation in Vitro and in Vivo. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:1643–1649. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307844200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Puoti G, Giaccone G, Rossi G, Canciani B, Bugiani O, Tagliavini F. Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: co-occurrence of different types of PrP(Sc) in the same brain. Neurology. 1999;53:2173–2176. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.9.2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Pocchiari M, Puopolo M, Croes EA, Budka H, Gelpi E, Collins S, Lewis V, Sutcliffe T, Guilivi A, Delasnerie-Laupretre N, Brandel JP, Alperovitch A, Zerr I, Poser S, Kretzschmar HA, Ladogana A, Rietvald I, Mitrova E, Martinez-Martin P, Pedro-Cuesta J, Glatzel M, Aguzzi A, Cooper S, Mackenzie J, van Duijn CM, Will RG. Predictors of survival in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and other human transmissible spongiform encephalopathies. Brain. 2004;127:2348–2359. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Brown P, Rodgers-Johnson P, Cathala F, Gibbs CJ, Jr, Gajdusek DC. Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease of long duration: clinicopathological characteristics, transmissibility, and differential diagnosis. Ann Neurol. 1984;16:295–304. doi: 10.1002/ana.410160305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Dickinson AG, Fraser H, Outram GW. Scrapie incubation time can exceed natural lifespan. Nature. 1975;256:732–733. doi: 10.1038/256732a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Kimberlin RH, Walker CA. Competition between strains of scrapie depends on the blocking agent being infectious. Intervirology. 1985;23:74–81. doi: 10.1159/000149588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Bartz JC, Aiken JM, Bessen RA. Delay in onset of prion disease for the HY strain of transmissible mink encephalopathy as a result of prior peripheral inoculation with the replication-deficient DY strain. J Gen Virol. 2004;85:265–273. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19394-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Weissmann C, Aguzzi A. Approaches to therapy of prion diseases. Annu Rev Med. 2005;56:321–344. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.56.062404.172936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Soto C, Kascsak RJ, Saborio GP, Aucouturier P, Wisniewski T, Prelli F, Kascsak R, Mendez E, Harris DA, Ironside J, Tagliavini F, Carp RI, Frangione B. Reversion of prion protein conformational changes by synthetic beta-sheet breaker peptides. Lancet. 2000;355:192–197. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)11419-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Peretz D, Williamson RA, Kaneko K, Vergara J, Leclerc E, Schmitt-Ulms G, Mehlhorn IR, Legname G, Wormald MR, Rudd PM, Dwek RA, Burton DR, Prusiner SB. Antibodies inhibit prion propagation and clear cell cultures of prion infectivity. Nature. 2001;412:739–743. doi: 10.1038/35089090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]