Abstract

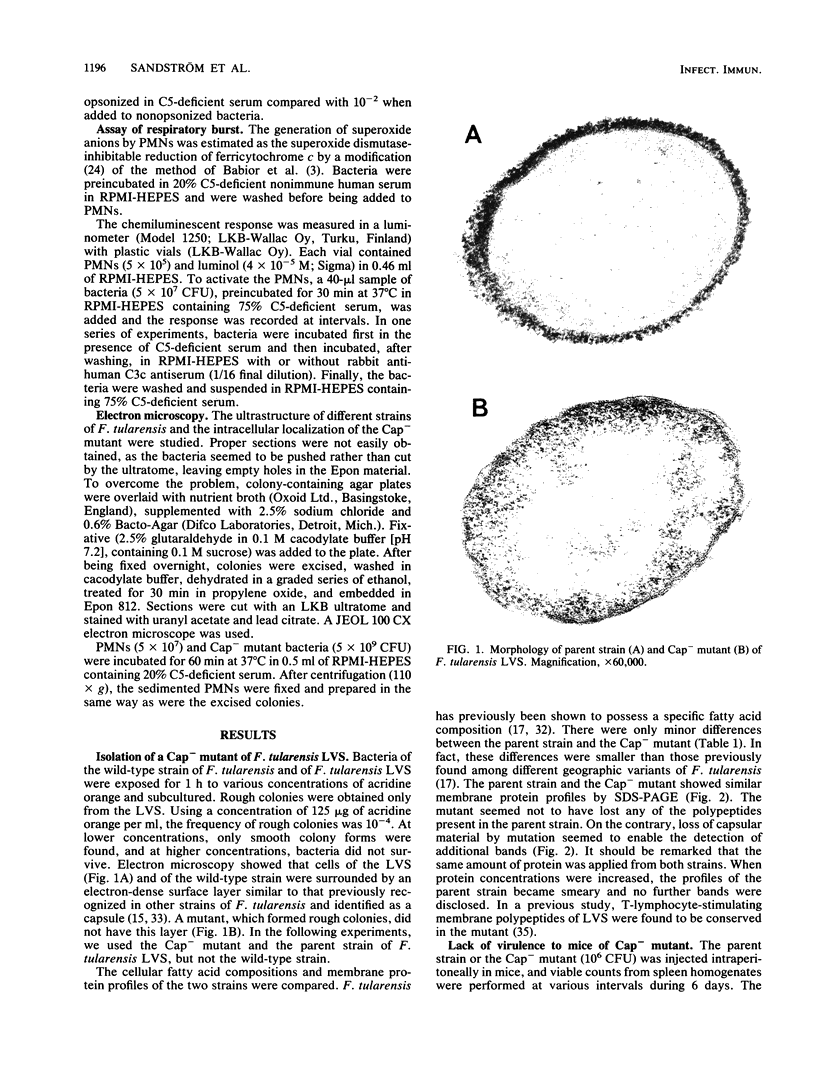

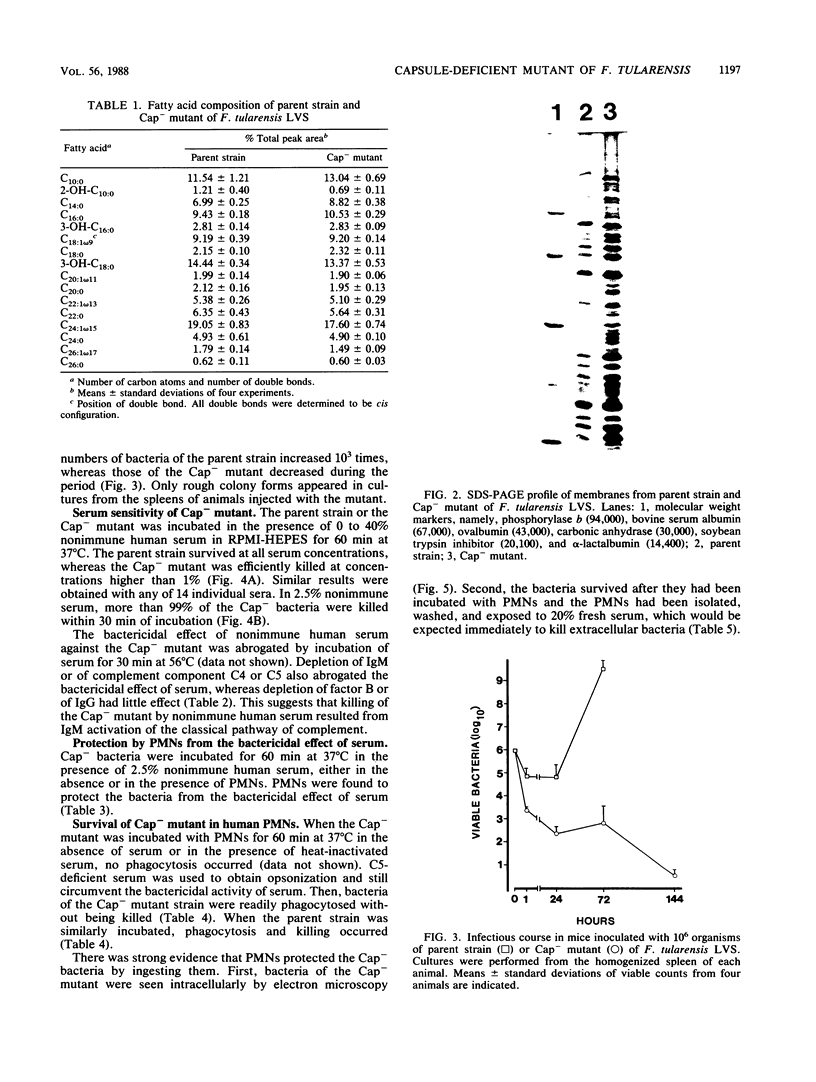

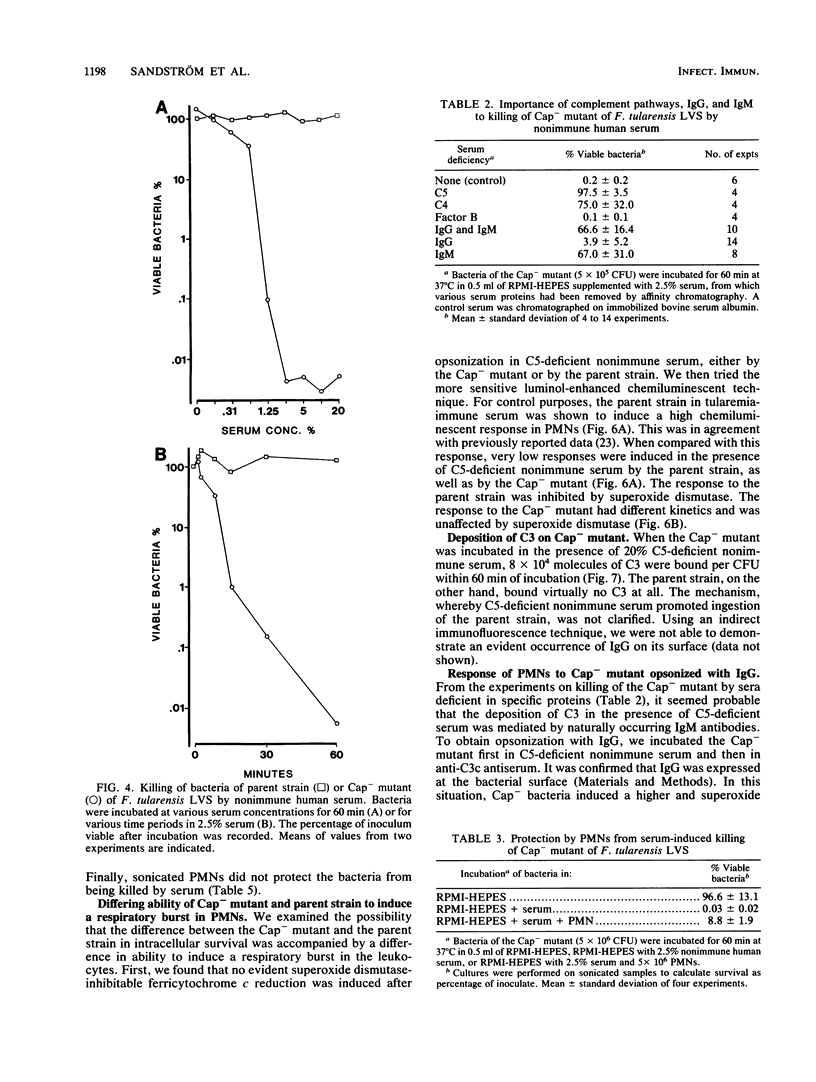

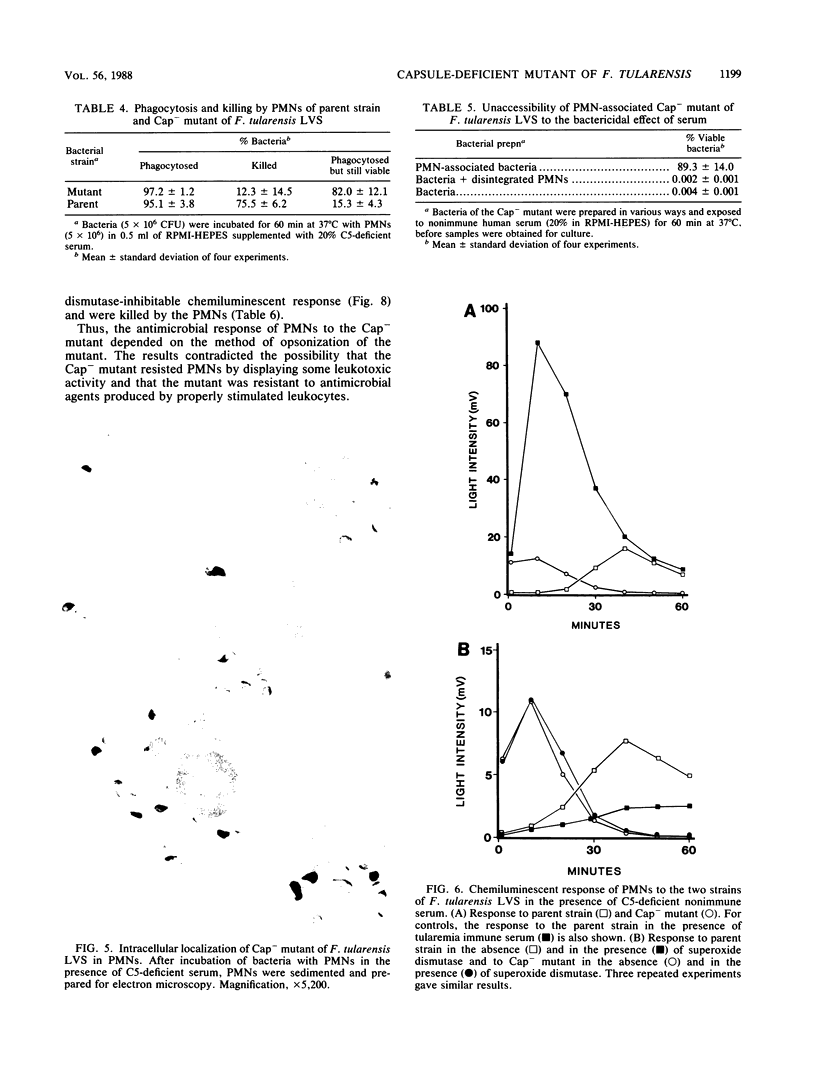

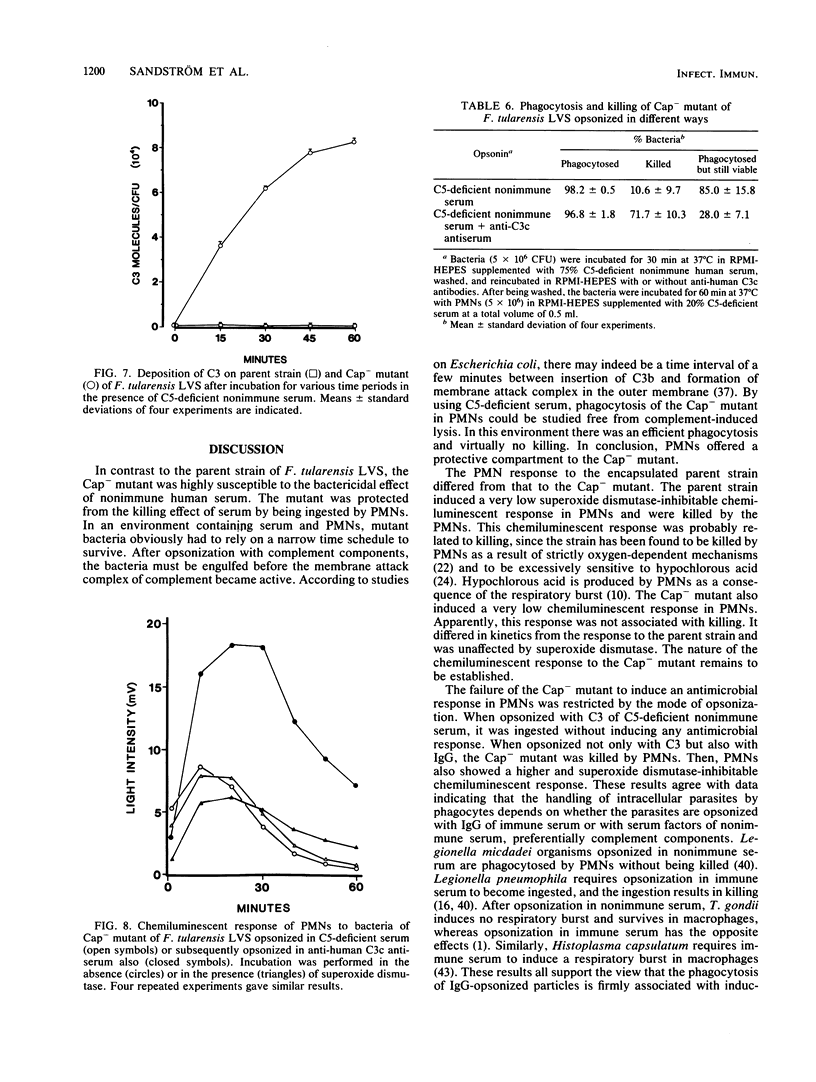

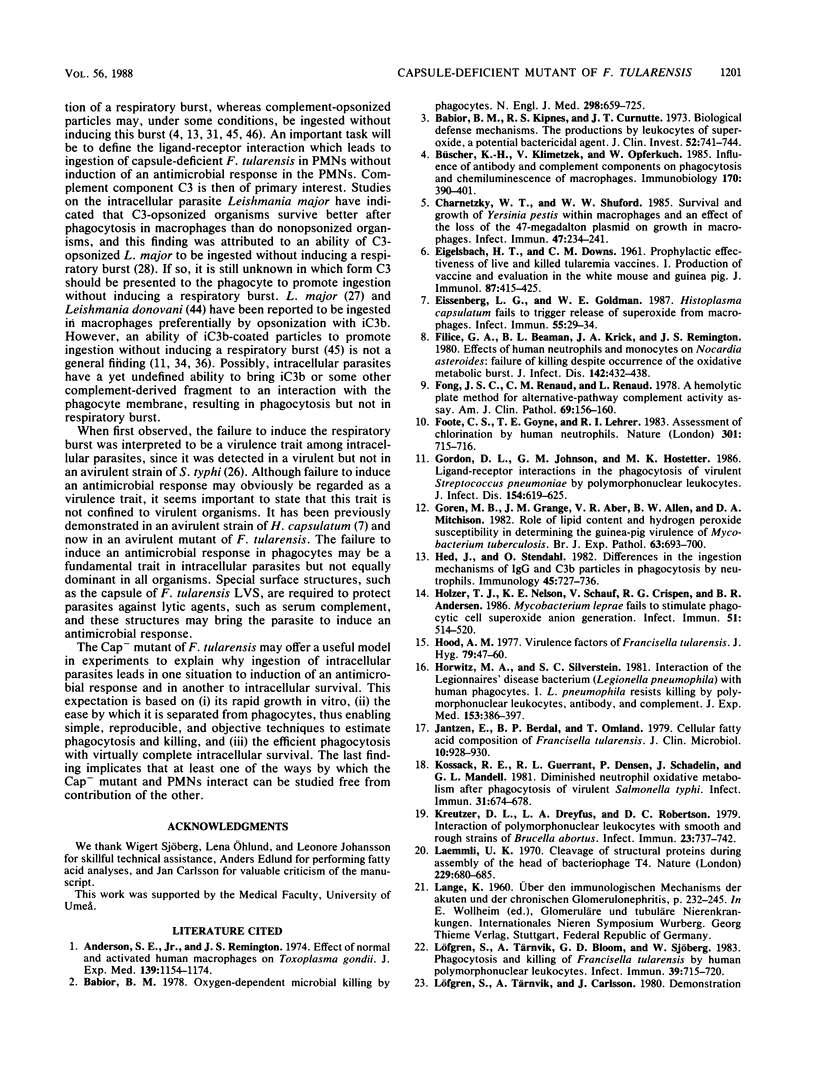

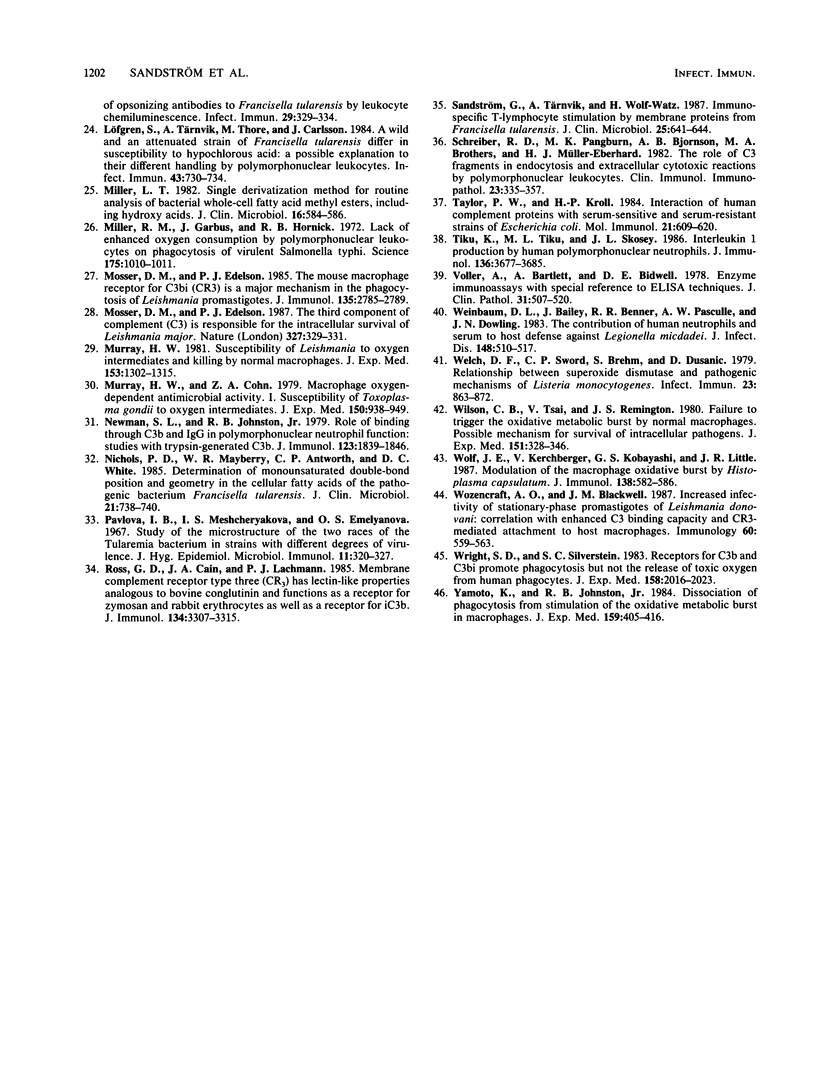

The live vaccine strain (LVS) of Francisella tularensis is killed by human polymorphonuclear leukocytes as a result of strictly oxygen-dependent mechanisms (S. Löfgren, A. Tärnvik, M. Thore, and J. Carlsson, Infect. Immun. 43:730-734, 1984). We now report that a capsule-deficient (Cap-) mutant of LVS survives in the leukocytes. In contrast to the encapsulated parent strain, the Cap- mutant was avirulent in mice and was susceptible to the bactericidal effect of nonimmune human serum. The mutant was killed by serum as a result of activation of the classical pathway of complement by naturally occurring immunoglobulin M. This killing by serum was mitigated by the presence of human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. After opsonization in complement component C5-deficient nonimmune serum, the Cap- mutant was ingested and survived in the leukocytes. Under these conditions, the parent strain was killed. The leukocytes responded to both the parent and the Cap- strain with a very low chemiluminescent response. Only the response to the parent strain was inhibited by superoxide dismutase. When the Cap- mutant was opsonized with immunoglobulin G, it induced a higher and superoxide dismutase-inhibitable chemiluminescent response and was killed by the leukocytes. In conclusion, the capsule of F. tularensis LVS seemed to protect this organism against the bactericidal effect of serum. When deprived of the capsule, the organism failed to induce an antimicrobial response in polymorphonuclear leukocytes and survived in the leukocytes. Survival in phagocytes is a key characteristic of intracellular parasites. The Cap- mutant of F. tularensis may become a useful tool in experiments to explain the differences between pathways of ingestion of intracellular parasites, evidenced by the death or survival of the parasite.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Anderson S. E., Jr, Remington J. S. Effect of normal and activated human macrophages on Toxoplasma gondii. J Exp Med. 1974 May 1;139(5):1154–1174. doi: 10.1084/jem.139.5.1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babior B. M., Kipnes R. S., Curnutte J. T. Biological defense mechanisms. The production by leukocytes of superoxide, a potential bactericidal agent. J Clin Invest. 1973 Mar;52(3):741–744. doi: 10.1172/JCI107236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babior B. M. Oxygen-dependent microbial killing by phagocytes (second of two parts). N Engl J Med. 1978 Mar 30;298(13):721–725. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197803302981305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büscher K. H., Klimetzek V., Opferkuch W. Influence of antibody and complement components on phagocytosis and chemiluminescence of macrophages. Immunobiology. 1985 Dec;170(5):390–401. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(85)80063-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charnetzky W. T., Shuford W. W. Survival and growth of Yersinia pestis within macrophages and an effect of the loss of the 47-megadalton plasmid on growth in macrophages. Infect Immun. 1985 Jan;47(1):234–241. doi: 10.1128/iai.47.1.234-241.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EIGELSBACH H. T., DOWNS C. M. Prophylactic effectiveness of live and killed tularemia vaccines. I. Production of vaccine and evaluation in the white mouse and guinea pig. J Immunol. 1961 Oct;87:415–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eissenberg L. G., Goldman W. E. Histoplasma capsulatum fails to trigger release of superoxide from macrophages. Infect Immun. 1987 Jan;55(1):29–34. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.1.29-34.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filice G. A., Beaman B. L., Krick J. A., Remington J. S. Effects of human neutrophils and monocytes on Nocardia asteroides: failure of killing despite occurrence of the oxidative metabolic burst. J Infect Dis. 1980 Sep;142(3):432–438. doi: 10.1093/infdis/142.3.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong J. S., Renaud L. A hemolytic plate method for alternative-pathway complement activity assay. Am J Clin Pathol. 1978 Feb;69(2):156–160. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/69.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foote C. S., Goyne T. E., Lehrer R. I. Assessment of chlorination by human neutrophils. Nature. 1983 Feb 24;301(5902):715–716. doi: 10.1038/301715a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon D. L., Johnson G. M., Hostetter M. K. Ligand-receptor interactions in the phagocytosis of virulent Streptococcus pneumoniae by polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J Infect Dis. 1986 Oct;154(4):619–626. doi: 10.1093/infdis/154.4.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goren M. B., Grange J. M., Aber V. R., Allen B. W., Mitchison D. A. Role of lipid content and hydrogen peroxide susceptibility in determining the guinea-pig virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Br J Exp Pathol. 1982 Dec;63(6):693–700. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hed J., Stendahl O. Differences in the ingestion mechanisms of IgG and C3b particles in phagocytosis by neutrophils. Immunology. 1982 Apr;45(4):727–736. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzer T. J., Nelson K. E., Crispen R. G., Andersen B. R. Mycobacterium leprae fails to stimulate phagocytic cell superoxide anion generation. Infect Immun. 1986 Feb;51(2):514–520. doi: 10.1128/iai.51.2.514-520.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood A. M. Virulence factors of Francisella tularensis. J Hyg (Lond) 1977 Aug;79(1):47–60. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400052840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz M. A., Silverstein S. C. Interaction of the Legionnaires' disease bacterium (Legionella pneumophila) with human phagocytes. I. L. pneumophila resists killing by polymorphonuclear leukocytes, antibody, and complement. J Exp Med. 1981 Feb 1;153(2):386–397. doi: 10.1084/jem.153.2.386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jantzen E., Berdal B. P., Omland T. Cellular fatty acid composition of Francisella tularensis. J Clin Microbiol. 1979 Dec;10(6):928–930. doi: 10.1128/jcm.10.6.928-930.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kossack R. E., Guerrant R. L., Densen P., Schadelin J., Mandell G. L. Diminished neutrophil oxidative metabolism after phagocytosis of virulent Salmonella typhi. Infect Immun. 1981 Feb;31(2):674–678. doi: 10.1128/iai.31.2.674-678.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreutzer D. L., Dreyfus L. A., Robertson D. C. Interaction of polymorphonuclear leukocytes with smooth and rough strains of Brucella abortus. Infect Immun. 1979 Mar;23(3):737–742. doi: 10.1128/iai.23.3.737-742.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli U. K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970 Aug 15;227(5259):680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löfgren S., Tärnvik A., Bloom G. D., Sjöberg W. Phagocytosis and killing of Francisella tularensis by human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Infect Immun. 1983 Feb;39(2):715–720. doi: 10.1128/iai.39.2.715-720.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löfgren S., Tärnvik A., Thore M., Carlsson J. A wild and an attenuated strain of Francisella tularensis differ in susceptibility to hypochlorous acid: a possible explanation of their different handling by polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Infect Immun. 1984 Feb;43(2):730–734. doi: 10.1128/iai.43.2.730-734.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller L. T. Single derivatization method for routine analysis of bacterial whole-cell fatty acid methyl esters, including hydroxy acids. J Clin Microbiol. 1982 Sep;16(3):584–586. doi: 10.1128/jcm.16.3.584-586.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller R. M., Garbus J., Hornick R. B. Lack of enhanced oxygen consumption by polymorphonuclear leukocytes on phagocytosis of virulent Salmonella typhi. Science. 1972 Mar 3;175(4025):1010–1011. doi: 10.1126/science.175.4025.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosser D. M., Edelson P. J. The mouse macrophage receptor for C3bi (CR3) is a major mechanism in the phagocytosis of Leishmania promastigotes. J Immunol. 1985 Oct;135(4):2785–2789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosser D. M., Edelson P. J. The third component of complement (C3) is responsible for the intracellular survival of Leishmania major. 1987 May 28-Jun 3Nature. 327(6120):329–331. doi: 10.1038/327329b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray H. W., Cohn Z. A. Macrophage oxygen-dependent antimicrobial activity. I. Susceptibility of Toxoplasma gondii to oxygen intermediates. J Exp Med. 1979 Oct 1;150(4):938–949. doi: 10.1084/jem.150.4.938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray H. W. Susceptibility of Leishmania to oxygen intermediates and killing by normal macrophages. J Exp Med. 1981 May 1;153(5):1302–1315. doi: 10.1084/jem.153.5.1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman S. L., Johnston R. B., Jr Role of binding through C3b and IgG in polymorphonuclear neutrophil function: studies with trypsin-generated C3b. J Immunol. 1979 Oct;123(4):1839–1846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols P. D., Mayberry W. R., Antworth C. P., White D. C. Determination of monounsaturated double-bond position and geometry in the cellular fatty acids of the pathogenic bacterium Francisella tularensis. J Clin Microbiol. 1985 May;21(5):738–740. doi: 10.1128/jcm.21.5.738-740.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlova I. B., Meshchekyakova I. S., Emelyanova O. S. Study of the microstructure of the two geographic races of the tularaemia bacterium in strains with different degrees of virulence. J Hyg Epidemiol Microbiol Immunol. 1967;11(3):320–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross G. D., Cain J. A., Lachmann P. J. Membrane complement receptor type three (CR3) has lectin-like properties analogous to bovine conglutinin as functions as a receptor for zymosan and rabbit erythrocytes as well as a receptor for iC3b. J Immunol. 1985 May;134(5):3307–3315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandström G., Tärnvik A., Wolf-Watz H. Immunospecific T-lymphocyte stimulation by membrane proteins from Francisella tularensis. J Clin Microbiol. 1987 Apr;25(4):641–644. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.4.641-644.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber R. D., Pangburn M. K., Bjornson A. B., Brothers M. A., Müller-Eberhard H. J. The role of C3 fragments in endocytosis and extracellular cytotoxic reactions by polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1982 May;23(2):335–357. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(82)90119-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor P. W., Kroll H. P. Interaction of human complement proteins with serum-sensitive and serum-resistant strains of Escherichia coli. Mol Immunol. 1984 Jul;21(7):609–620. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(84)90046-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiku K., Tiku M. L., Skosey J. L. Interleukin 1 production by human polymorphonuclear neutrophils. J Immunol. 1986 May 15;136(10):3677–3685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voller A., Bartlett A., Bidwell D. E. Enzyme immunoassays with special reference to ELISA techniques. J Clin Pathol. 1978 Jun;31(6):507–520. doi: 10.1136/jcp.31.6.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinbaum D. L., Bailey J., Benner R. R., Pasculle A. W., Dowling J. N. The contribution of human neutrophils and serum to host defense against Legionella micdadei. J Infect Dis. 1983 Sep;148(3):510–517. doi: 10.1093/infdis/148.3.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch D. F., Sword C. P., Brehm S., Dusanic D. Relationship between superoxide dismutase and pathogenic mechanisms of Listeria monocytogenes. Infect Immun. 1979 Mar;23(3):863–872. doi: 10.1128/iai.23.3.863-872.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson C. B., Tsai V., Remington J. S. Failure to trigger the oxidative metabolic burst by normal macrophages: possible mechanism for survival of intracellular pathogens. J Exp Med. 1980 Feb 1;151(2):328–346. doi: 10.1084/jem.151.2.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf J. E., Kerchberger V., Kobayashi G. S., Little J. R. Modulation of the macrophage oxidative burst by Histoplasma capsulatum. J Immunol. 1987 Jan 15;138(2):582–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wozencraft A. O., Blackwell J. M. Increased infectivity of stationary-phase promastigotes of Leishmania donovani: correlation with enhanced C3 binding capacity and CR3-mediated attachment to host macrophages. Immunology. 1987 Apr;60(4):559–563. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright S. D., Silverstein S. C. Receptors for C3b and C3bi promote phagocytosis but not the release of toxic oxygen from human phagocytes. J Exp Med. 1983 Dec 1;158(6):2016–2023. doi: 10.1084/jem.158.6.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto K., Johnston R. B., Jr Dissociation of phagocytosis from stimulation of the oxidative metabolic burst in macrophages. J Exp Med. 1984 Feb 1;159(2):405–416. doi: 10.1084/jem.159.2.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]