Abstract

Thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1) treatment of dermal microvascular endothelial cells (MvEC) has been shown to upregulate Fas ligand (FasL) and to induce apoptosis by a mechanism that requires caspase-8 activity. We have examined the potential anti-angiogenic effects of TSP-1 on primary human brain MvEC. The addition of TSP-1 to primary human brain MvEC cultured as monolayers on type 1 collagen, induced cell death and apoptosis (evidenced by caspase-3 cleavage) in a dose- (5–30 nM) and time- (maximal at 17 h) dependent manner. TSP-1 treatment for 17 h induced caspase-3 cleavage that required caspase-8 activity and the tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 (TNF-R1). We did not find a requirement for Fas, or the tumor necrosis-related apoptosis-inducing ligand receptors (TRAIL-R) 1 and 2. We confirmed the findings using caspase inhibitors, blocking antibodies and small interfering RNA (siRNA). Further analysis indicated that the TSP-1 induction of caspase-3 cleavage of primary human brain MvEC adherent to collagen required the synthesis of new message and protein, and that TSP-1 induced the expression of TNFα mRNA and protein. Consistent with these findings, when the primary human brain MvEC were propagated on collagen gels mAb anti-TNF-R1 reversed the inhibitory effect, in part, of TSP-1 on tube formation and branching. These data identify a novel mechanism whereby TSP-1 can inhibit angiogenesis-through induction of apoptosis in a process mediated by TNF-R1.

Keywords: Thrombospondin-1, TSP-1, Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cells, Apoptosis, Tumor Necrosis Factor, TNF-R, TNFα

Introduction

It is well established that angiogenesis is essential for tumor growth and that inhibition of angiogenesis can be an effective strategy for the treatment of solid tumors when combined with other therapy (Folkman, 2007). Thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1) can act as an anti-angiogenic agent as demonstrated using isolated non-brain microvascular endothelial cells (MvEC) and in animals bearing tumors (Dawson et al., 1997; Reiher et al., 2002). TSP-1-mediated inhibition of angiogenesis involving dermal MvEC requires the transmembrane receptor, CD36 (Dawson et al., 1997; Pearce et al., 1995; Jimenez et al., 2000; Simantov and Silverstein, 2003), and this has been confirmed in a CD36-null mouse model (Febbraio et al., 2002). CD36, which is expressed on endothelial and other cells, interacts with the CSVTCG and GVITRIR peptides found in the type 1 repeat domain of TSP-1 (Dawson et al., 1997; Pearce et al., 1995). Type 1 TSP-1 peptides that correspond to the CD36 binding site can inhibit angiogenesis (Dawson et al., 1999; Iruela-Arispe et al., 1999; Tolsma et al., 1993) and the circulating histidine-rich glycoprotein (HRGP), which contains a CD36-like TSP binding domain, has been shown to promote angiogenesis by blocking the TSP-1-CD36 interaction (Simantov et al., 2001; Silverstein and Febbraio, 2007).

It is thought that several different anti-angiogenic agents, including TSP-1, act by inducing apoptosis of MvECs (Jimenez et al., 2000; LaVallee et al., 2003; Panka and Mier, 2003; Volpert et al., 2002). Notably, TSP-1-induced apoptosis of MvECs associated with malignant melanoma cells has been shown in vivo in a subcutaneous xenograft model (Jimenez et al., 2000). Several studies have demonstrated that anti-angiogenic agents induce apoptosis of MvECs by upregulating the levels of a death receptor or its ligand and that the Fas death receptor system is a common target (LaVallee et al., 2003; Panka and Mier, 2003; Volpert et al., 2002). TSP-1-induced apoptosis of dermal MvECs propagated as monolayers on gelatin, which requires caspase-8 activity, is associated with upregulation of Fas ligand (FasL) (Volpert et al., 2002) and the inhibitory effect of TSP-1 in a corneal neovascularization assay requires FasL and Fas (Volpert et al., 2002). In addition, it has been shown that pigment epithelial-derived factor induces the expression of FasL on the cell surface of dermal MvEC (Volpert et al., 2002) and canstatin induces FasL expression in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (Panka and Mier, 2003). The involvement of death receptors other than Fas in apoptosis induced by anti-angiogenic agents has been reported, however. For example, 2-methoxyestradiol upregulates TRAIL-R2 (also known as DR5) in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (LaVallee et al., 2003), interleukin-18 stimulation of liver endothelial cells upregulates TNF-R1 expression, thereby promoting TNFα-induced apoptosis (Marino and Cardier, 2003), and the inhibition of angiogenesis observed on endostatin treatment in the corneal neovascularization assay occurs independently of Fas or FasL (Volpert et al., 2002).

Although the anti-angiogenic effects of TSP-1 currently are thought to be mediated by apoptosis, other mechanisms have been implicated. For example, it has been reported that the anti-angiogenic effect of TSP-1 on dermal MvECs propagated as a monolayer on gelatin is mediated by caspase-independent inhibition of cell cycle progression (Armstrong et al., 2002); however, neither the requirement for CD36 nor the identity of the receptor mediating this effect has been described. TSP-1 also may promote an anti-angiogenic effect by affecting the levels of its binding partner, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2 (Armstrong and Bornstein, 2003; Yang Z et al., 2001; Bein and Simons, 2000; Rodriguez-Manzaneque et al., 2001). In the case of TSP-2, we have shown that its anti-invasive effect on mouse brain MvEC is due to low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1)-mediated internalization of a complex of MMP-2 and TSP-2 (Fears et al., 2005).

To date, the mechanisms by which TSP-1 exerts its anti-angiogenesis effects have been studied using MvECs derived from sources other than the brain. We therefore examined the effects of TSP-1 on primary human brain MvEC grown as monolayer cultures on type 1 collagen. These studies confirmed that TSP-1 induces apoptosis of these cells in a CD36-dependent manner; however, in contrast to the reports of studies using dermal MvECs (Jimenez et al., 2000; Volpert et al., 2002; Nor et al., 2000), we found that the TSP-1-induced apoptosis required expression of TNF-R1 and that TSP-1 induced the expression of TNFα. Analysis of tube formation and branching of bFGF-stimulated human brain MvEC propagated on collagen gels confirmed that TSP-1 has an anti-angiogenic effect against these cells which could be reversed, in part, by pretreatment with an inhibitory mAb directed toward TNF-R1. These analyses of human brain MvEC reveal a novel mechanism in which the pro-apoptotic/anti-angiogenic effect of TSP-1 are mediated by TNF-R1.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Primary human brain MvECs were purchased from Cell Systems (Kirkland, WA) and used at passages 2 through 8 at which time the cells were confirmed as endothelial cells by western blot analysis of the expression of CD31/PECAM-1 (BD Pharmingen). The cells were propagated on type 1 collagen-coated flasks in the recommended CSC media (Cell Systems) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin, and 2 µg/ml amphotericin. Prior to treatment, the cells were harvested, replated on type 1 collagen-coated wells in CSC media with 10% FBS or M199 media with 10% FBS for 24 h, and then the media replaced with serum-starving media (M199 with 2% FBS). FBS with low endotoxin levels was utilized in all experiments. The TSP-1 used in the experiments was purified from human platelets as described elsewhere (Crombie and Silverstein, 1998).

Apoptosis assays

Apoptosis-associated DNA fragmentation was assessed using the TUNEL assay kit (TdT FRAG-EL from Oncogene, Boston, MA) as described previously (Ding et al., 2005). The percent of substrate-labeled nuclei was determined after counting the cells in 10 fields per replica at 20X magnification. Staurosporine was purchased from Sigma Chemical Co., (St. Louis, MO) and z-VAD-fmk from BD Pharmingen (San Diego,CA).

FACS analyses

Non-permeabilized cells (300,000) were reacted with the primary and secondary antibodies at 4°C as described (Pijuan-Thompson and Gladson, 1997) and then analyzed using a FACScan (Beckman Coulter) with WinMDI software (J. Trotter).

SDS-PAGE and western blot

Cell lysates were prepared, electrophoresed, and blotted as described previously (Ding et al., 2005) except that 10 µM trans-epoxysuccinyl-L-leucylamido-(4-guanidino) butane (e-64) (a cysteine protease inhibitor) was added to the lysate buffer in addition to the other protease inhibitors. Typically 130 µg of lysate was subjected to electrophoresis. Band intensities on autoradiographs were analyzed by densitometry, and the densitometric readings normalized to actin or GAPDH. The antibodies used for analysis of western blots were as follows: cleaved caspase-3 (1:5000 dilution), cleaved caspase-8 (1:1000 dilution), and cleaved PARP (1:5000 dilution) (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA); cleaved caspase-7 and cleaved caspase-3 (both at 1:5000 dilution) (Calbiochem Co., Gibbstown, NJ); actin (1 µg/ml) Sigma Chemical Co.); GAPDH (1 µg/ml) (Fitzgerald Industries, Concord, MA); CD36 (0.7 µg/ml) (Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz), Fas (1 µg/ml) (Biosource International, San Diego, CA), and TNF-R1 (1 µg/ml) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). The cleaved caspase-8 antibody required a long exposure (1 h) to detect the antigen. z-IETD was purchased from Enzyme Systems (Aurora, OH). Cydoheximide and actinomycin-D were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. Blocking monoclonal antibodies to the following antigens were purchased and incubated with the cell monolayer for 30 min prior to the addition of TSP-1: DR4 and DR5 (Alexis Biochemicals, San Diego, CA); TNF-R1 (R&D Systems); Fas (U.S. Biologicals, Swampsott, MA); and CD36 (clone FA6-152) (Immunotech, Marselle, France) as were recombinant (rec)-human Fas decoy receptor (Fas DcR), rec-human TNFα, rec-human FasL, and rec-human TRAIL (R&D Systems).

Downregulation of gene expression with siRNA

siTNF-R1 was a smart pool of duplex siRNA purchased from Dharmacon Inc. (#M-005197-00) (Boulder, CO), and siFas was a target specific duplex siRNA purchased from Santa Cruz Biochechnology (#SC-29311). siCD36 was a smart pool of duplex siRNA (anti-sense sequences-51-PUUUACCUUUAUAUGUGUCGUU, 51-PGAAAUGUACACAGGUCUCCUU, 51-PUAUCCUAAGUAUGUCCUAUGUU, and 51-PUAACGUCGGAUUCAAAUACUU; #M-010206-01) and a pool of mutated duplex siCD36 RNA with two base pair mutations in each duplex was synthesized as a control (anti-sense sequences – UUUACCUUUCUAAGUGUCGUU, AAAUGUACUCGGGUCUCCUU, UAUCCAAGUACGUACUAUGUU, and UAACGUCGGUUUCAAAUACUU) (Dharmacon, Inc.). Cells were transfected with the siRNA using Hyperfect (Qiagen).

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated from brain MvEC using Qiagen’s RNeasy purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and quantified using RiboGreen (Molecular Probes (now Invitrogen), Carlsbad, CA). RT-PCR was performed as described elsewhere (Isayeva et al., 2007). Real time PCR was performed in an i-Cycler Optical Module version 3.021 real-time PCR system (BioRad, Hercules, CA) using SYBER green reagent supermix (Bio-Rad). Double-stranded DNA was used to create standard curves for β-actin, TNFα, FasL and TRAIL from a positive control that were then used in the real-time RT-PCR analysis. Values obtained for amplification of TNFα, FasL and TRAIL from each sample were normalized to the copy number for β-actin gene amplification from the same sample to derive the relative mRNA level for TNFα, FasL, and TRAIL in each condition and at each time point.

ELISA

The high sensitivity TNFα ELISA kit for conditioned media (detects 0.2–100 pg/ml) and the FasL and TRAIL ELISA kits for conditioned media (detect 15–1000 pg/ml) were purchased from R & D Systems and used as recommended. Conditioned media was removed from the cells, the media concentrated 20-fold for the TNFα ELISA and 40-fold for the FasL and TRAIL ELISAs using Micron 10 Microconcentrators at 4°C (Millipore, Burlington, MA). The cellular TNFα ELISA kit (detects 0.5 – 32 pg/ml) was purchased from Biosource (Camarillo, CA) and used as recommended.

Capillary tube formation assays

Harvested primary human brain MvEC were plated on the prepared collagen gel as described (Haskell et al., 2003). After incubation for 48 h (37° C, 5% CO2), tube length and branched tube formation were imaged with a Nikon microscope using the X20 objective (four images/well). Tube length and branching were then measured in each image and analyzed for each condition as the mean ± S.E.M.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was determined using an unpaired Student’s t-test. P values of ≤ 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

TSP-1 induces apoptosis of primary human brain MvEC through a mechanism that is dependent on CD36 and cell surface death receptors

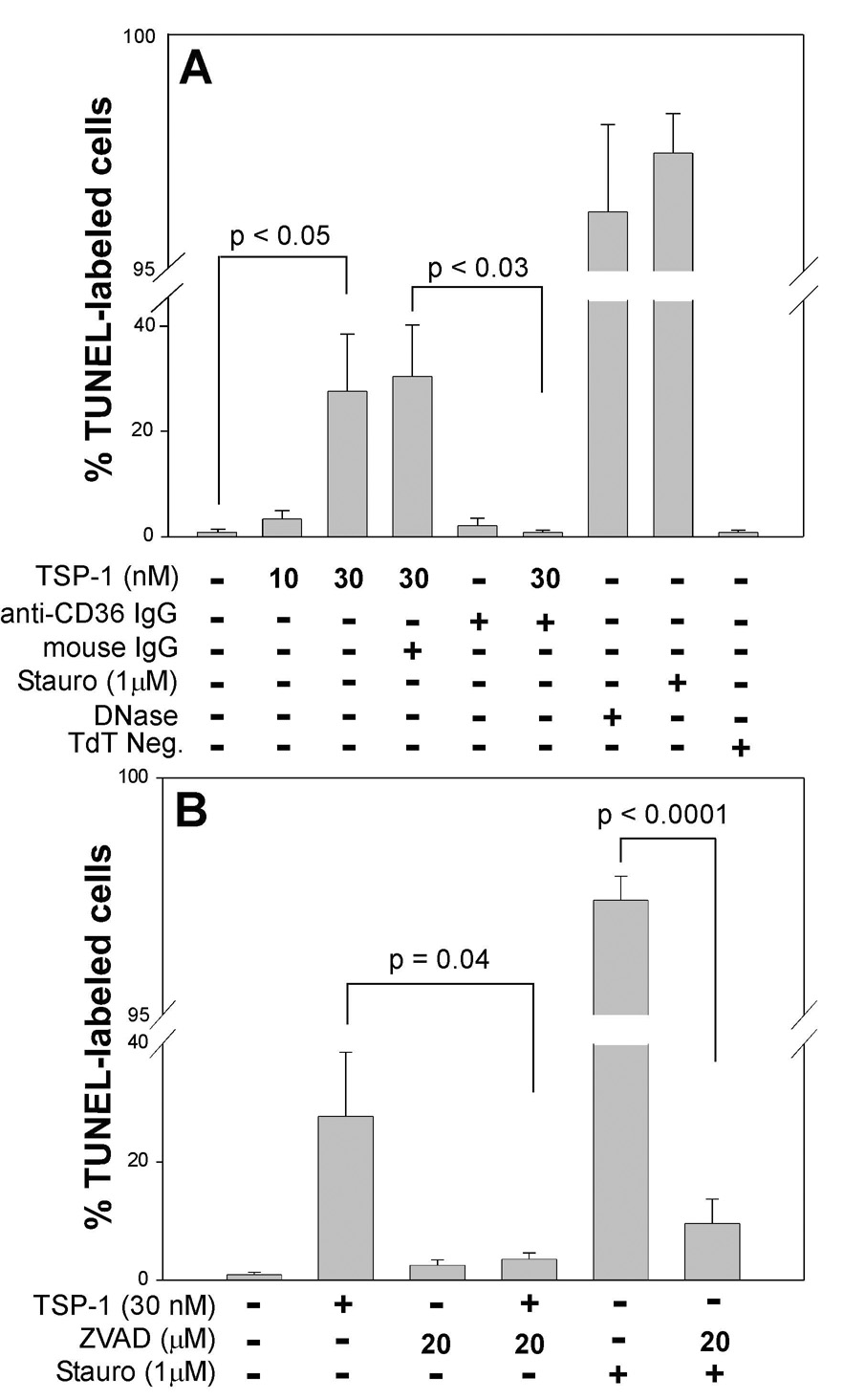

On examination of the effects of TSP-1 on human brain MvECs propagated as monolayers on type 1 collagen, we found that TSP-1 induced apoptosis, as assessed by TUNEL staining, of 20 to 40% of the primary human brain MvEC (Fig. 1A) in a dose-dependent manner over a range of 5 to 50 nM (data not shown; effects of 10 and 30 nM shown in Fig. 1A). Treatment of the cells with TSP-1 (30 nM) in the presence of 20 µM z-VAD-fmk, a broad spectrum caspase inhibitor, reduced the numbers of TUNEL-positive cells to baseline (Fig. 1B). Apoptosis was confirmed by western blot analysis of caspase-3 cleavage (Green, 2005; Thornburn, 2004), which indicated that treatment of human brain MvEC with TSP-1 (10 nM) resulted in the time-dependent appearance of cleaved caspase-3 that peaked at 17 h post-treatment. At this time-point, the generation of cleaved caspase-3 was dose-dependent over a range of 5–30 nM of TSP-1, with maximal cleavage being achieved on treatment with 30 nM TSP-1 (data not shown). Thus, a concentration of 30 nM TSP-1 and a time point of 17 h were used in all subsequent analyses of caspase-3 cleavage.

Figure 1. Induction of cell death of primary human brain MvEC by TSP-1.

TUNEL labeling of primary human brain MvEC plated onto type 1 collagen-coated wells in serum-starving media (M199 with 2% FBS) indicates (Panel A) that the cells are susceptible to apoptosis induced by treatment with the non-specific inducers, staurosporine and DNase. Treatment with TSP-1 induces apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner that is inhibited by addition of monoclonal anti-CD36 IgG, but not irrelevant mouse IgG, and is inhibited (Panel B) by the broad-spectrum caspase inhibitor ZVAD. Conditions were assayed in replicas of three and the experiment was repeated twice. The data are presented as the mean ± S.E.M.

The requirement for CD36 in the TSP-1-induced apoptosis of the human brain MvEC plated on collagen was determined using an anti-CD36 antibody that has been shown to block the prodeath signal observed on TSP-1 treatment of dermal MvEC (Jimenez et al., 2000). Addition of this blocking antibody during TSP-1 treatment of brain MvEC with TSP-1 had an inhibitory effect on TUNEL staining (Fig. 1A) and reduced the level of caspase-3 cleavage by ≈ 60% (based on densitometric readings) (Fig. 2A&B, lanes 3&4).

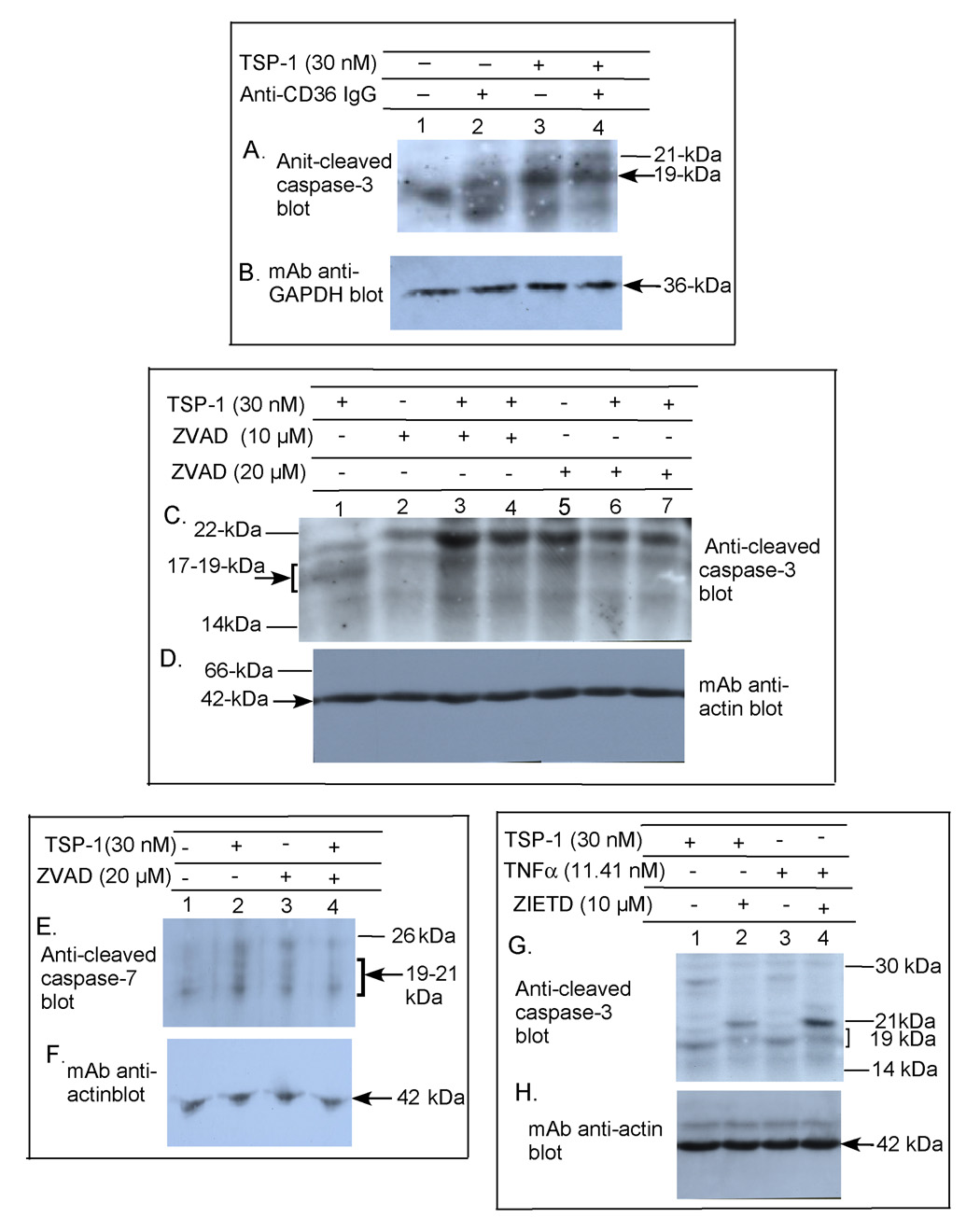

Figure 2. Induction of caspase-3, caspase-7, and caspase-8 cleavage in primary human brain MvEC.

Immunoblot analysis of primary human brain MvEC grown as monolayers on collagen in serum-starving media (A–H) shows that TSP-1 induced apoptosis requires CD36 (A&B), that it is inhibited by a broad spectrum caspase inhibitor zVAD (C–F), and that it occurs through an extrinsic pathway as determined by a specific inhibitor of caspase-8 cleavage zIETD (G&H). As a positive control for activation of the extrinsic pathway of apoptosis, cells were treated with TNFα and caspase-3 cleavage was blocked by z-IETD (G&H). The experiment was repeated 2X and highly similar results were obtained.

To determine whether activation of a death receptor pathway was required for the TSP-1 induced cleavage of caspase-3, we first tested the effects of the broad spectrum caspase inhibitor zVAD. This inhibited, in part, the TSP-1 induced cleavage of caspase-3 and of caspase-7, another effector caspase (Fig. 2C&D, lanes 1, 6&7 and Fig. 2E&F, lanes 2&4, respectively). As the death receptor, or extrinsic, apoptosis pathways can be differentiated from the intrinsic pathways on the basis of their activation of caspase-8, we then tested the effects of the caspase 8-specific inhibitor, z-IETD. We found that TSP-1-induced cleavage of caspase-3 was inhibited (Fig. 2G&H, lanes 1&2) as was TNFα-induced cleavage of caspase-3 (Fig. 2G&H, lanes 3&4). Thus, TSP-1 can induce apoptosis of human brain MvECs and the generation of a competent apoptotic signal requires the participation of CD36 and cell surface death receptors.

TSP-1 induction of caspase-3 cleavage is mediated by TNF-R1

Brain MvEC express the death receptors Fas, TNF-R1, TRAIL-R1 (also known as DR4) and DR5 (Marino and Cardier, 2003; Janin et al., 2002; Secchiero et al., 2003; Choi and Benveniste, 2004). We confirmed the expression of all four of these receptors on > 90% of the primary human brain MvEC grown as monolayers by FACS analysis (data not shown). To identify which of these death receptors mediates the TSP-1-induced apoptotic signal in the primary human brain MvEC grown as monolayers, we added monoclonal antibodies that have been shown to inhibit the binding of the soluble ligand to the cell surface death receptor (Varghese et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2003; Sprick et al., 2002). We initially optimized the concentration of the blocking death receptor monoclonal antibodies to inhibit caspase-3 cleavage induced by addition of soluble TNFα, FasL, or TRAIL to the cell monolayer. Addition of anti-TNF-R1 monoclonal antibody (Varghese et al., 2002) significantly inhibited TSP-1-induced caspase-3 cleavage (Fig. 3A&B, lanes 2 and 4–6). Surprisingly, however, the anti-Fas monoclonal antibody (Zhang et al., 2003) failed to inhibit TSP-1- induced cleavage of caspase-3 (Fig. 3E&F, lanes 1, 3, & 4) although it did inhibit caspase-3 cleavage induced by rec-FasL (data not shown). Addition of (rec) human Fas decoy receptor (DcR) (Fig. 3C&D, lanes 2–5) or anti-DR4 and anti-DR5 monoclonal antibodies (Sprick et al., 2002) also failed to inhibit TSP-1-induced caspase-3 cleavage (Fig. 3G&H, lanes 2–4 and data not shown).

Figure 3. Requirement for TNF-R1 in TSP-1-induced apoptosis of primary human brain MvEC.

Immunoblot analysis of primary human brain MvEC grown as monolayers on collagen in serum-starving media (A–H) shows that addition of TSP-1 or rec-TNFα induces cleavage of caspase-3 and caspase-3 cleavage is inhibited by addition of 6 µg/ml anti-TNF-RI monoclonal antibody (A&B; all lanes from the same gel). Addition of 3 µg/ml Fas DcR (C&D) or of 5 µg/ml anti-Fas monoclonal antibody failed to inhibit TSP-1 induced caspase-3 cleavage (E&F, all lanes from the same gel). Addition of 20 µg/ml anti-DR4 monoclonal antibody, also failed to inhibit the TSP-1 induced capase-3 cleavage (G&H).

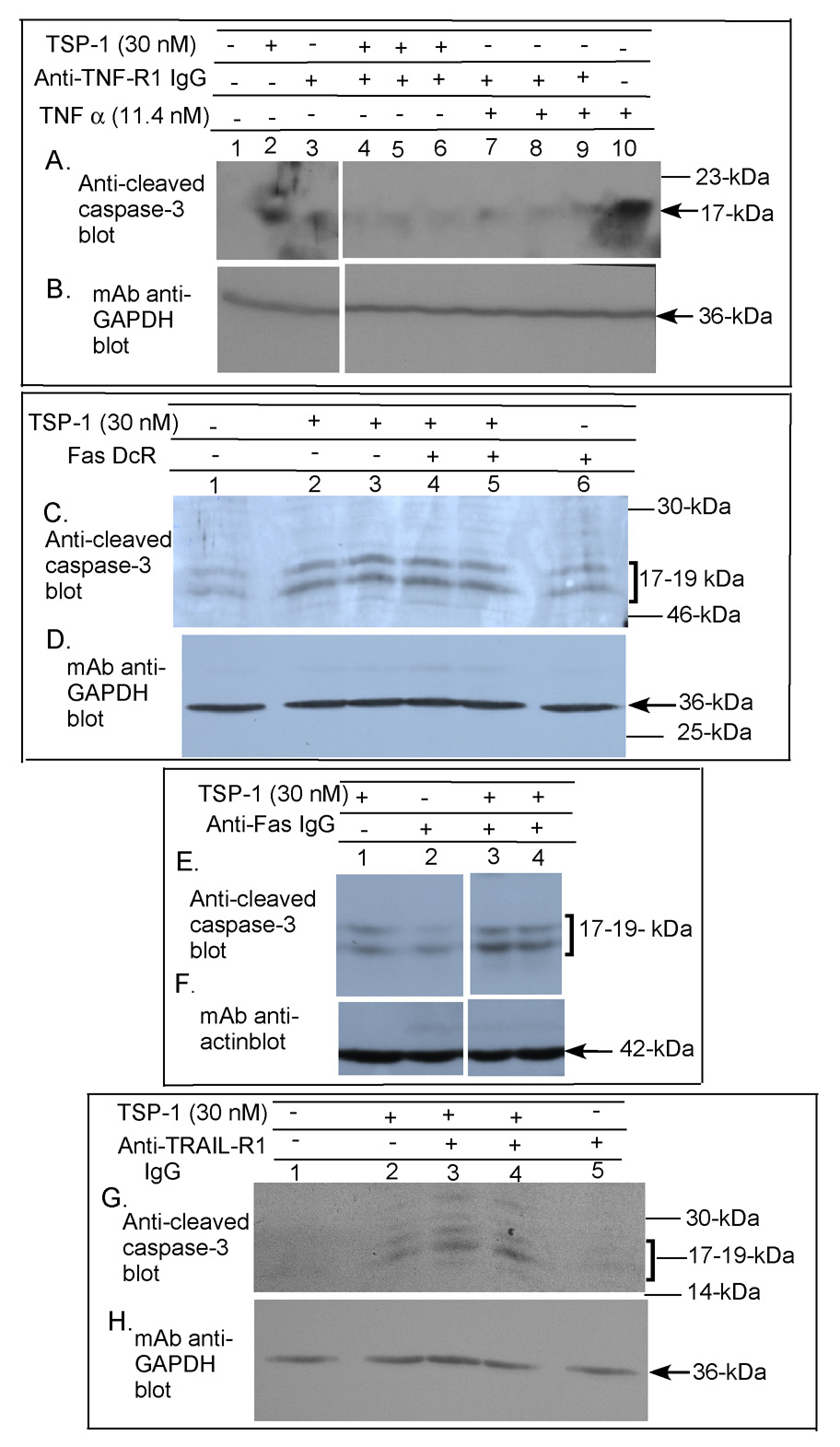

To further differentiate the requirements for TNF-R1 and Fas in TSP-1-induced apoptosis we downregulated the receptors using siRNA. The downregulation of TNF-R1 with siTNF-R1 blocked the ability of TSP-1 to induce caspase-3 cleavage at 17 h (Fig. 4D&E, lanes 2&4). In contrast, downregulation of Fas with siFas in the same experiment did not block the ability of TSP-1 to induce caspase-3 cleavage at 17 h (Fig. 4F&G). TUNEL assays confirmed that downregulation of TNF-R1 with siRNA significantly blocked TSP-1 induced cell death whereas downregulation of Fas with siRNA did not (data not shown).

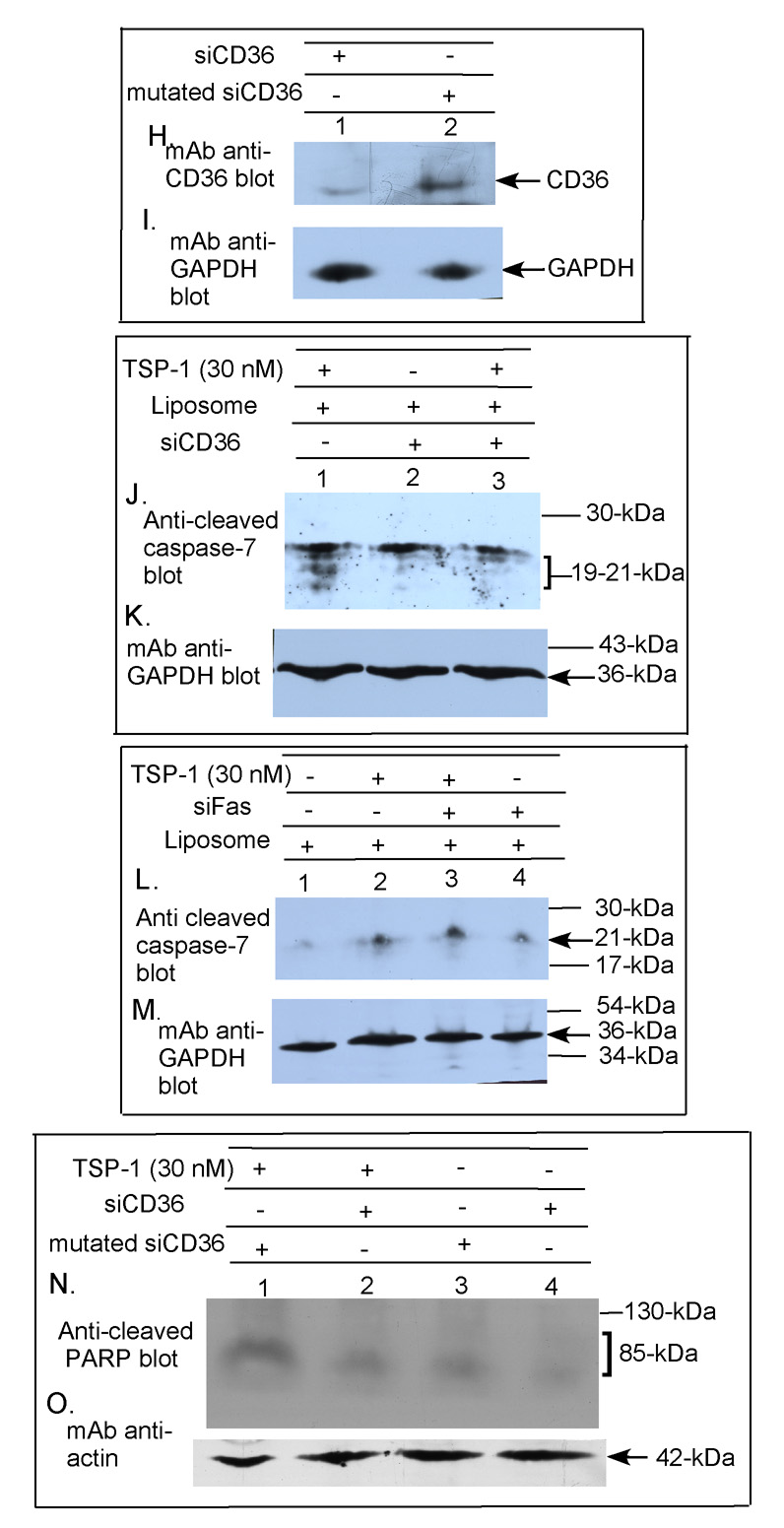

Figure 4. Effect of siRNA downregulation of TNF-R1, Fas or CD36 on caspase-3, -7 or PARP cleavage in primary human brain MvEC.

Immunoblot analysis indicates the effectiveness of siTNF-R1, siFas and siCD36 on downregulation of the TNF-RI, Fas and CD36, respectively, in the primary human brain MvEC plated as monolayers on type-1 collagen (A–C, all lanes from the same gel; and H&I). Under the conditions employed, neither siTNF-R1, siFas, siCD36 nor mutated siCD36 altered the cell morphology or viability over the time course of the assay (data not shown). Immunoblot analysis of primary human brain MvEC treated with siTNF-R1 (D&E), siFAS (F&G and L&M), or siCD36 (J&K and N&O) for 48 h, followed by treatment with TSP-1 in serum-starving media for 17 h shows that siTNF-R1 and siCD36 inhibit the cleavage of caspase-3, -7 or PARP induced by TSP-1 whereas siFas does not (all lanes in each panel from the same gel).

To confirm the requirement for CD36 in the TSP-1-induced apoptosis, we also downregulated CD36 with siRNA. Downregulation of CD36 with siCD36 blocked the ability of TSP-1 to induce cleavage of caspase-7 at 17 h (Fig. 4J&K, lanes 1&3), whereas in the same experiment the downregulation of Fas did not block TSP-1 induced caspase-7 cleavage (Fig. 4L&M, lanes 2&3). The downregulation of CD36 with siCD36 also blocked TSP-1-induced poly (ADP-ribose) polymerose (PARP) cleavage, whereas treatment of the cells with the mutated (control) CD36 siRNA did not (Fig. 4N&O, lanes 1&2).

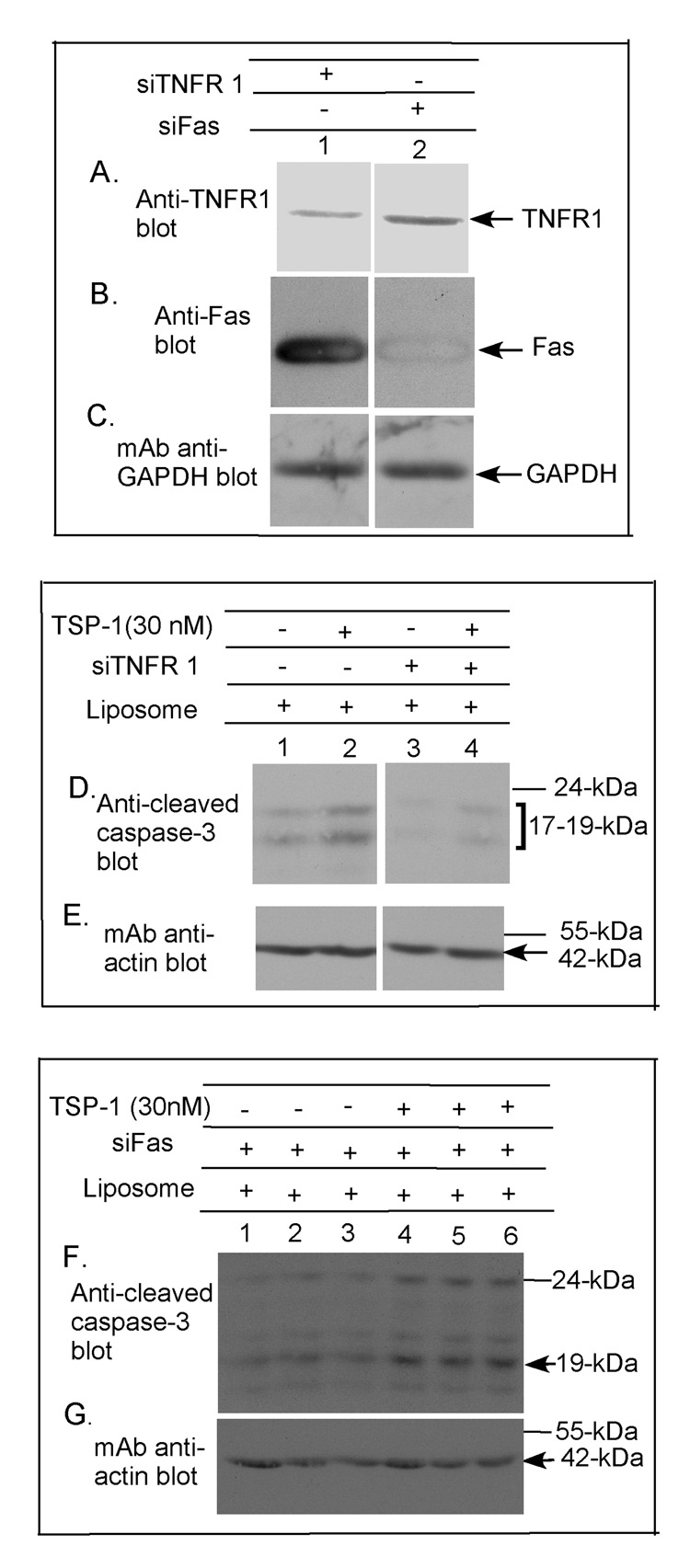

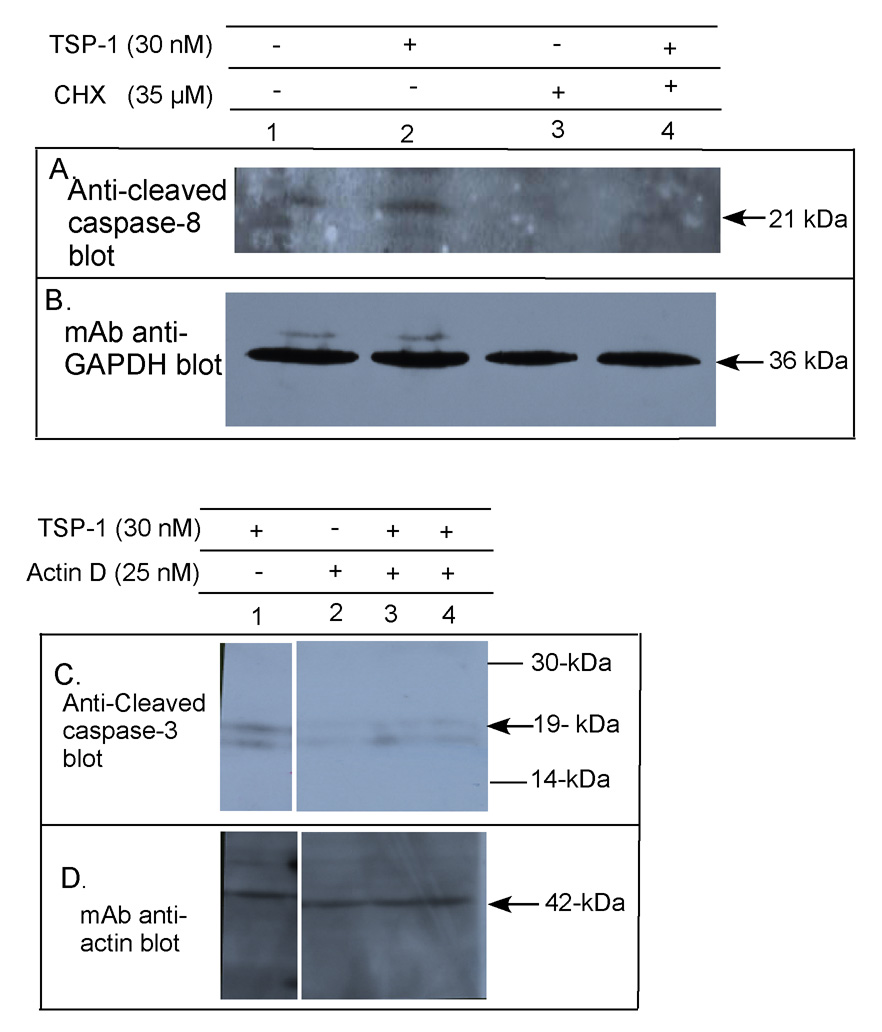

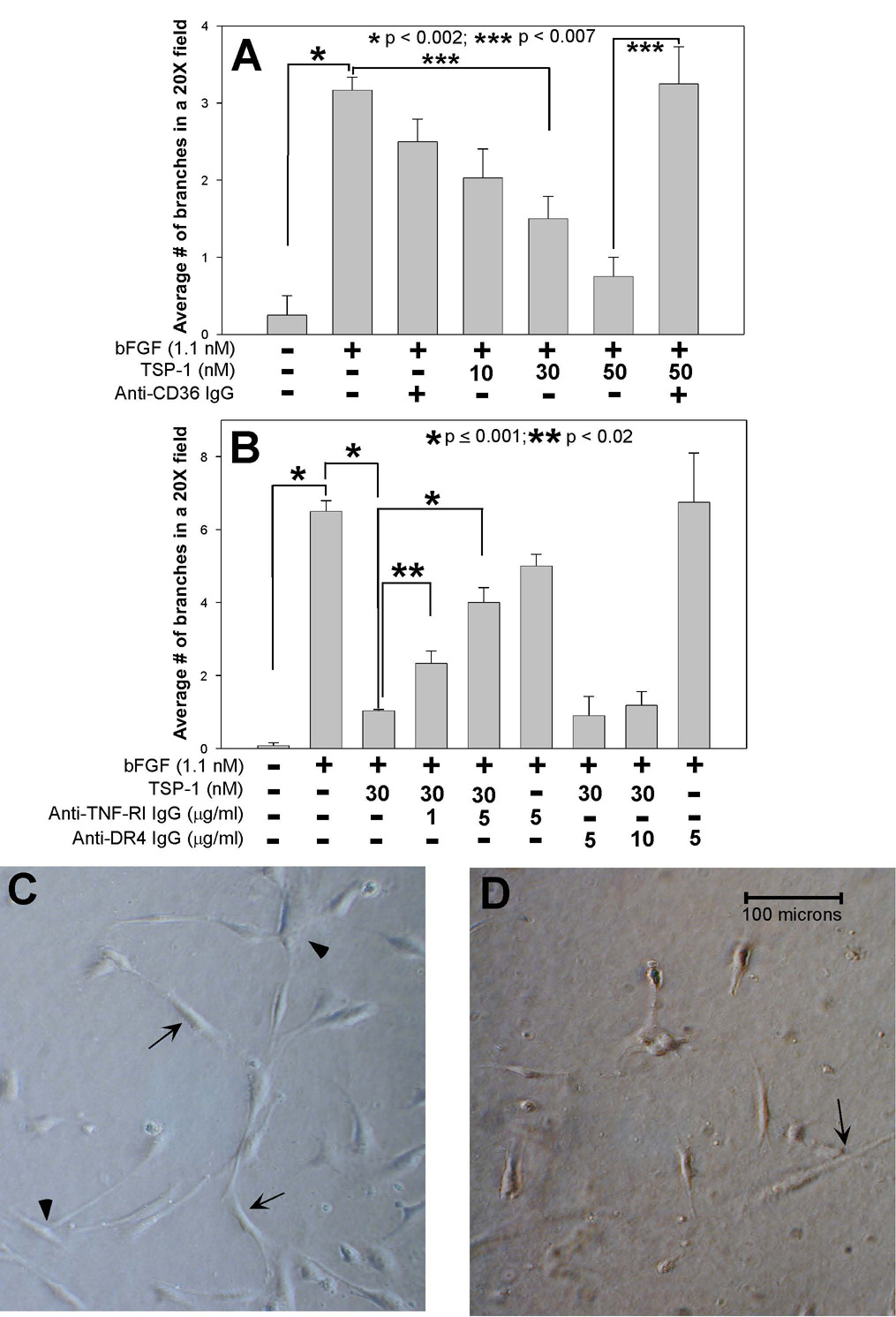

TSP-1 induces expression of TNFα in primary human brain MvEC

New protein translation has been shown to be necessary for TSP-1-induced cell death of dermal MvEC (Volpert et al., 2002). We found that TSP-1 treatment of primary human brain MvEC in the presence of either cycloheximide (Fig. 5A&B, lanes 2&4) or actinomycin D (Fig. 5C&D, lanes 1, 3, & 4) reduced caspase-3 cleavage to baseline levels, suggesting that both new mRNA transcription and protein translation are necessary for the pro-apoptotic effect of TSP-1 on primary human brain MvEC.

Figure 5. Requirement for new protein translation and new mRNA transcription in TSP-1 induced caspase-3 cleavage, and the effect of TSP-1 on expression of TNFα in primary human brain MvEC.

Primary human brain MvEC were plated as a monolayer on type I collagen and treated with TSP-1 in serum-starving conditions. The optimal concentrations of actinomycin D (25 nM) and cycloheximide (35 µM) under the conditions of this assay were determined and the effects of these inhibitors on caspase-3 cleavage assessed. The apoptotic signal requires new protein translation as indicated by inhibition on treatment with cycloheximide (A&B), and new mRNA transcription as indicated by inhibition on treatment with actinomycin D (C&D, all lanes from the same gel). Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of primary human brain MvEC treated with TSP-1 indicates (E) a significant 3-fold enhancement of the levels of TNFα mRNA at 6 h, and an 8-fold enhancement at 10 h that dropped to a 2-fold enhancement at 14 h; (F) upregulation of the level of secreted TNFα protein in the media; and (G) upregulation of the level of cellular TNFα protein. A significant enhancement in the level of (H) FasL mRNA and (I) TRAIL mRNA was observed with TSP-1 stimulation at 6 and 14 h or 6 and 10 h, respectively; however, no increase in (J) secreted FasL or TRAIL protein was detectable. Levels of TNFα, FasL, and TRAIL mRNA were normalized to the level of β actin mRNA. Conditions were assayed in replicas of 3 or 4. These experiments were repeated and similar results obtained.

Analysis of the potential upregulation of the death receptor ligand, TNFα, using quantitative RT-PCR analysis indicated that, as compared to the levels of TNFα in cells that were not treated with TSP-1, TSP-1 treatment of primary human brain MvEC resulted in a 3-fold higher level of TNFα mRNA at 6 h and an 8-fold higher level at 10 h, dropping to 2-fold higher levels at 14 h (Fig. 5E). Treatment with 30 nM TSP-1 also raised the level of soluble TNFα protein in the conditioned media at 4 h (1.7-fold) and this remained higher over 17 h (Fig. 5F). Consistent with the higher levels of TNFα mRNA and soluble protein on TSP-1 treatment, we found nearly 2-fold higher levels of cellular TNFα at 8 h with significantly higher levels also being observed at 10 h post-TSP-1 treatment (Fig 5G). Similar evaluation of the levels of FasL and TRAIL mRNA by quantitative RT-PCR analysis indicated an increase in the relative levels of FasL mRNA at 6 and 14 h and of TRAIL mRNA at 6 and 10 h (Fig. 5H&I, respectively). The levels of TRAIL and FasL mRNAs were lower than that of TNFα, as it required a 4-fold greater amount of cDNA (reverse transcribed from RNA) to detect FasL or TRAIL on quantitative RT-PCR analysis. Even though the conditioned media were concentrated 40-fold, as compared to the 20-fold concentration used for the analysis of TNFα in the ELISA assay, we were unable to detect FasL or TRAIL in the conditioned media over the same four time points (2, 4, 8 and 17 h) whether or not the cells were treated with TSP-1 (Fig. 5J). The upregulation of TNFα mRNA and protein on treatment with TSP-1, and the timing of this upregulation, further suggest that TSP-1 induces apoptosis through the TNF-R1 in primary human brain MvEC cultured as monolayers adherent to type 1 collagen.

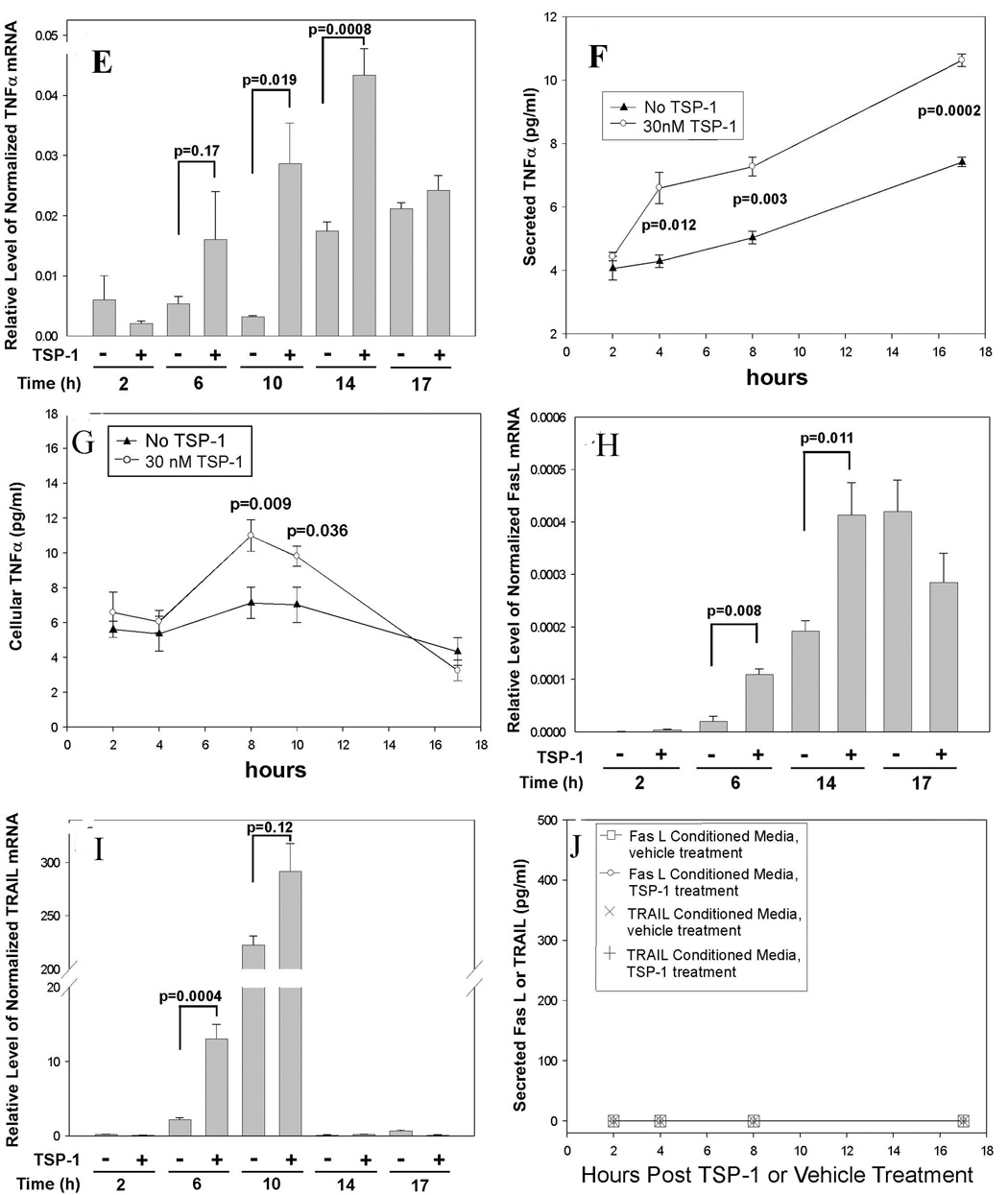

TSP-1 inhibits tubular morphogenesis of primary human brain MvEC grown on collagen gels in a manner that is CD36-dependent and reversible, in part, by blocking of TNF-R1

To establish directly whether TSP-1 exerts an anti-angiogenic effect on human brain MvEC and whether TNF-R1 is involved in this anti-angiogenic effect, we extended our studies to an in vitro model in which primary human brain MvEC are propagated in collagen gels in the presence of 5 ng/ml of bFGF rather than as a monolayer. Under these conditions, the human brain MvEC are stimulated to undergo angiogenesis as indicated by tube formation and branching.

Pretreatment with TSP-1 inhibited both tube length and branching in a dose-dependent manner over a range of 5 to 50 nM (Fig. 6A, and data not shown). The effect of pretreatment with 30 nM TSP-1 on bFGF stimulated branching is illustrated in Fig. 6D as compared to Fig. 6C. Similar results were found on culture of the human brain MvEC on fibrin gels in the presence of vascular endothelial cell growth factor (VEGF) (data not shown). The inhibitory effect of TSP-1 on angiogenesis in the corneal neovascularization assay has been shown to involve the engagement of CD36 (Jimenez et al., 2000). Addition of a blocking anti-CD36 antibody to the human brain MvEC cultures did not in itself inhibit angiogenesis but did result in a significant reversal of the inhibition of tube formation and branching induced by treatment with 50 nM TSP-1 (Fig. 6A and data not shown). In this assay, the tube length and branching in the presence of bFGF and TSP-1 plus anti-CD36 antibody were compared to the tube length and branching in the presence of bFGF and TSP-1. Taken together, these data suggest that TSP-1 can mediate an anti-angiogenic effect on brain MvEC, and that this effect is largely CD36-dependent.

Figure 6. TSP-1 inhibits branching of primary human brain MvEC in a dose-, CD36- and TNFR1-dependent manner.

(A&B) Primary human brain MvEC (12,000) were plated on collagen gels in M199 media with 10% FBS, and the addition of the indicated treatment for 48 h (37°C, 5% CO2), followed by photography and analysis for branching, as described in the Materials and Methods. (C&D) Example of typical tube formation and branching observed with (C) bFGF stimulation, and (D) the inhibition of bFGF stimulated tube formation and branching observed with 30 nM TSP-1 addition. The conditions were assayed in replicas of two, the experiment repeated 2X and the results combined and presented as the mean ± S.E.M.

Finally, we examined the requirement for TNF-R1 in tubular morphogenesis through the use of blocking antibodies. The addition of the blocking anti-TNF-R1 monoclonal antibody (Varghese et al., 2002) alone had no effect on the assay of tubular morphogenesis of bFGF-treated brain MvEC in the absence of TSP-1 but resulted in a partial, but significant, reversal of TSP-1 inhibition of tube formation and branching of bFGF-treated brain MvEC (Fig. 6B and data not shown). The maximal reversal that could be achieved under the conditions of this assay was 50%. A concentration of 5 µg/ml anti-TNF-R1 monoclonal antibody was able to achieve this effect with higher concentrations (10 and 25 µg/ml) being no more effective (data not shown). The addition of a monoclonal antibody specific for DR4 (Sprick et al., 2002) failed to reverse the inhibitory effect of TSP-1 on tube branching and formation at 5 and 10 µg/ml (Fig. 6B and data not shown), indicating that the effects of the anti-TNF-R1 monoclonal antibody were specific.

Discussion

Our findings indicate that TSP-1 can induce apoptosis and inhibit tubular morphogenesis of human brain MvEC adherent as a monolayer to type 1 collagen in a dose- and time-dependent manner. As has been described in other systems (Dawson et al., 1997; Jimenez et al., 2000), the TSP-1-mediated apoptosis is dependent on CD36. Studies of TSP-1-induced apoptosis using other types of human MvEC have implicated Fas rather than TNF-R1. We found, however, that the apoptosis of the primary human brain MvEC in monolayer culture appears to be mediated through the TNF-R1 death receptor as it requires expression of this receptor. Moreover, the mechanism appears to involve induction of the expression of TNFα by TSP-1. Although TNF-R1 has been implicated previously in interleukin-18-enhanced stimulation of liver endothelial cell apoptosis (Marino and Cardier, 2003), it has not been implicated previously in TSP-1-mediated inhibition of angiogenesis.

Our data indicate the involvement of a caspase-8-mediated extrinsic pathway of apoptosis in TSP-1-mediated apoptosis of primary human brain MvEC, which implicates an initiating signal involving death receptors containing death domains that can recruit caspase-8 into the death inducing signaling complex. Such complexes include Fas, DR4 and DR5, as well as TNF-R1 (reviewed in (Thornburn, 2004; Mocellin et al., 2005)), all of which are expressed on human brain MvEC (Marino and Cardier, 2003; Janin et al., 2002; Secchiero et al., 2003; Choi and Benveniste, 2004). Although Fas has been implicated in TSP-1-induced apoptosis of MvEC obtained from skin and in the corneal neovascularization assay (Jimenez et al., 2000), we were unable to inhibit TSP-1-induced caspase-3 cleavage through the addition of a Fas blocking antibody, a recombinant Fas decoy receptor, or the use of Fas siRNA in our system. These findings underscore the complexity of anti-angiogenic mechanisms and the factors that determine which mechanism is utilized. The possibility that the Fas receptor expressed on the human brain MvECs is not functional was ruled out as we were able to induce apoptosis by addition of exogenous FasL and the work of others indicates that mouse brain MvEC are sensitive to Fas-mediated apoptosis in vivo (Janin et al., 2002).

The TSP-1 induction of caspase-3 cleavage in the brain MvEC exhibited latency as has been described for TSP-1-induced death-receptor-mediated apoptosis in dermal MvEC (Jimenez et al., 2000; Volpert et al., 2002). The time lapse that occurred prior to the observation of maximal apoptosis (17 h) post-TSP-1 treatment of the human brain MvEC in type 1 collagen-adherent monolayers was somewhat longer than that reported for TSP-1 treated dermal MvEC (4 h) (Volpert et al., 2002). It is therefore possible that the pretreatment of the dermal MvEC cells with either a cytokine or a growth factor that was used to upregulate Fas expression may have potentiated the Fas-mediated apoptotic response. We found that the latency is associated with a requirement for new mRNA transcription, which has not been reported previously, as well as confirming a requirement for new protein translation (Jimenez et al., 2000). Moreover, analysis of the expression of the death receptor ligands revealed enhanced expression of TNFα mRNA as well as soluble and cellular TNFα protein. Although TSP-1 treatment resulted in elevated expression of FasL and TRAIL mRNAs in the brain MvEC, soluble FasL and TRAIL were not detectable in the conditioned media. The levels of TNF-R1 and Fas protein in cell lysates, as determined by immunoblotting, were unaffected by TSP-1 treatment (T.A. Rege and C.L. Gladson, unpublished data). This ability of TSP-1 to upregulate TNFα suggests a mechanism by which TSP-1 can promote its apoptotic effect in the human brain MvEC. Interestingly, it has been reported that TNFα can induce hemorrhagic necrosis of vascular tumors in some tumor models. This appears to occur through a direct, dose-dependent effect of TNFα on the tumor endothelial cells as there is a requirement for expression of TNF-R1 on the endothelial cells ((Stoelcker et al., 2000); reviewed in (Mocellin et al., 2005)). The apparent selectivity of the TNFα-induced cytotoxicity for the tumor vasculature as compared to its effects on the normal tissue vasculature in the above studies is of interest in terms of the development of therapeutic strategies, but the mechanisms that contribute to this selectivity remain unclear. As we found that TSP-1 induced apoptosis requires CD36, the future elucidation of the mechanism that links CD36 engagement to the upregulation of TNFα is therefore of great interest.

Other investigators recently reported that a set of anti-angiogenic genes is induced on treatment of dermal MvEC with a single anti-angiogenesis agent, endostatin (Abdollahi et al., 2004). It is therefore possible that TSP-1 induces a set of pro-death genes, including TNFα, FasL and TRAIL as we observed, but that the environmental and cellular context dictates the translation of protein. Thus, the association of Fas with the TSP-1-induced apoptosis of the dermal MvEC (Volpert et al., 2002) may have been due to the promotion of FasL and Fas expression by cytokine pre-stimulation of the dermal MvEC prior to TSP-1 stimulation, which would have resulted in preferential priming of the cells such that the Fas death receptor pathway is activated. As organ-specific endothelial cell heterogeneity has been reported, it also is possible that the origin of the endothelial cells and their microenvironment may affect the generation of competent signals (St.Croix et al., 2000). The body of evidence that indicates that the Fas receptor is not silenced on the primary human brain MvEC suggests that any differences in the responses of the brain MvEC and dermal MvEC to TSP-1 would have to lie in the signaling pathway(s) from CD36 to the death receptor. TSP-1 is a homotrimeric protein with a multi-domain structure (reviewed in (Carlson et al., 2008)) that can interact with several proteins that are known to play critical roles in the interactions of the cell with the extracellular matrix and the regulation of cell growth and migration, as well as proteins that can regulate the interactions of TSP-1 with these proteins. Thus, the function of TSP-1 and its mechanisms of action are most likely highly susceptible to the extracellular environment of the cell and the specific type of cell. Indeed, we have shown recently that low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP1) mediates the anti-invasive effect of TSP-2 in mouse brain MvEC adherent to Matrigel-coated filters through internalization of a TSP-2-MMP-2 complex (Fears et al., 2005).

Our studies do not rule out the possibility that the anti-angiogenic effects of TSP-1 may be mediated, at least in part, by pathways other than death receptor-mediated apoptosis. For example, TSP-1 may induce cross-talk between the extrinsic and intrinsic pathways. Although mechanisms other than apoptosis have been proposed (Armstrong et al., 2002), we found that TSP-1 treatment did not significantly alter DNA synthesis, as estimated by tritiated-thymidine incorporation, or cell cycle progression, as assessed by FACS analysis of propidium iodine staining of primary human brain MvEC grown as monolayers, although a cocktail of growth factors clearly induced cell cycle progression (T.A. Rege and C.L. Gladson, unpublished data).

The involvement of TNF-R1 in the anti-angiogenic effects of TSP-1 on brain MvEC was confirmed on treatment of bFGF-stimulated MvEC in collagen gels in which an anti-TNF-R1 monoclonal antibody was capable of reversing significantly TSP-1 inhibition of tube formation and branching. We also confirmed that the engagement of CD36 was necessary for TSP-1 inhibition of tubular morphogenesis in this model. Thus, our results suggest a novel mechanism whereby TNF-R1 mediates the pro-apoptotic/anti-angiogenic effect of TSP-1 in primary human brain MvEC.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mrs. Rhonda Carr for preparing the manuscript and Dr. Deane F. Mosher (University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI) for kindly providing the rec-TSP-2.

This work was supported by predoctoral fellowship #NS49674 from the NIH-NINDS to T.A.R., and grants #CA97110 and #CA109748 from the NIH-NCI to C.L.G. and the grant #P50 CA97247 (projects 2 and 5) from NIH-NCI to E.N.B. and C.L.G.

Abbreviations

- bFGF

basic fibroblast growth factor

- FasL

Fas ligand

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- GAPDH

glycraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- HRGP

histidine-rich glycoprotein

- MvEC

microvascular endothelial cells

- LRP1

low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein1

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- rec

recombinant

- Fas DcR

rec-Fas decoy receptor

- RT-PCR

reverse transcriptase PCR

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor α

- TNF-R1

TNF receptor 1

- TRAIL

tumor necrosis-related apoptosis-inducing ligand

- TRAIL-R

TRAIL receptor

- DR4

TRAIL-R1

- DR5

TRAIL-R2

- TSP-1 and -2

thrombospondin-1 and -2

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- TUNEL

terminal deoxynucleotidyl end-labeling

Literature Cited

- Abdollahi A, Hahnfeldt P, Maercker C, Grone HJ, Debus J, Ansorge W, Folkman J, Hlatky L, Huber PE. Endostatin's anti-angiogenic signaling network. Mol Cell. 2004;13(5):649–663. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00102-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong LC, Bjorkblom B, Hankenson KD, Siadak AW, Stiles CE, Bornstein P. Thrombospondin 2 inhibits microvascular endothelial cell proliferation by a caspaseindependent mechanism. Mol.Biol.Cell. 2002;13:1893–1905. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E01-09-0066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong LC, Bornstein P. Thrombospondin 1 and 2 function as inhibitors of angiogenesis. Matrix Biol. 2003;22:63–71. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(03)00005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bein K, Simons M. Thrombospondin type 1 repeats interact with matrix metlloproteinase 2. Regulation of metalloproteinase activity. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:32167–32173. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003834200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson CB, Lawler J, Mosher DF. Structures of thrombospondins. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:672–686. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7484-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi C, Benveniste EN. Fas ligand/Fas system in the brain; regulation of immune and apoptotic responses. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2004;44(1):65–81. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crombie R, Silverstein RL. Lysosomal intregral membrain protein II binds thrombospondin-1. Structure-function homology with the cell adhesion molecule CD36 defines a conserved recognition motif. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(9):4855–4863. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.9.4855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DW, Pearce SF, Zhong R, Silverstein RL, Frazier WA, Bouck NP. CD36 mediates the in vitro inhibitory effects of thrombospondin-1 on endothelial cells. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:707–717. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.3.707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DW, Volpert OV, Gillis P, Crawford SE, Xu H, Benedict W, Bouck NP. Three distinct D-amino acid substitutions confer potent anti-angiogenic activity on an inactive peptide derived from a thrombospondin-1 type 1 repeat. Mol Pharmocol. 1999;55:332–338. doi: 10.1124/mol.55.2.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Q, Grammer JR, Nelson MA, Guan JL, Stewart JE, Jr, Gladson CL. p27Kip1 and cyclin D1 are necessary for focal adhesion kinase regulation of cell cycle progression in glioblastoma cells propagated in vitro and in vivo in the scid mouse brain. J.Biol.Chem. 2005;280:6802–6815. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409180200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fears CY, Grammer JR, Stewart JE, Jr, Annis DS, Mosher DF, Bornstein P, Gladson CL. Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein contributes to the antiangiogenic activity of thrombospondin-2 in a murine glioma model. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9338–9346. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Febbraio M, Guy E, Coburn C, Knapp FF, Jr, Beets AL, Abumrad NA, Silverstein RL. The impact of overexpression and deficiency of fatty acid translocase (FAT)/CD36. Mol Cell Biochem. 2002;239(1–2):193–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman J. Angiogenesis: an organizing principle for drug discovery? Nat.Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:273–286. doi: 10.1038/nrd2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DR. Apoptotic pathways: ten minutes to dead. Cell. 2005;121:671–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haskell H, Natarajan M, Hecker TP, Ding Q, Stewart J, Jr, Grammer JR, Gladson CL. Focal adhesion kinase is expressed in the angiogenic blood vessels of malignant astrocytic tumors in vivo and promotes capillary tube formation of brain microvascular endothelial cells. Clin.Cancer Res. 2003;9:2157–2165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iruela-Arispe ML, Lombardo M, Krutzsch HC, Lawler J, Roberts DD. Inhibition of angiogenesis by thrombospondin-1 is mediated by 2 independent regions within the type 1 repeats. Circulation. 1999;100:1423–1431. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.13.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isayeva T, Ren C, Ponnazhagan S. Intraperitoneal gene therapy by rAAV provides long-term survival against epithelial ovarian cancer independently of survivin pathway. Gene Ther. 2007;14:138–146. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janin A, Deschaumes C, Daneshpouy M, Estaquire J, Micic-Polianski J, Rajagopalan-Levasseur P, Akarid K, Mounier N, Gluckman E, Socie G, Ameisen JC. CD95 engagement induces disseminated endothelial cell apoptosis in vivo: immunopathologic implications. Blood. 2002;99(8):2940–2947. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.8.2940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez B, Volpert OV, Crawford SE, Febbraio M, Silverstein RL, Bouck NP. Signals leading to apoptosis-dependent inhibition of neovascularization by thrombospondin-1. Nat Med. 2000;6:41–48. doi: 10.1038/71517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaVallee TM, Zhan XH, Johnson MS, Herbstritt CJ, Swartz G, Williams MS, Hembrough WA, Green SJ, Pribluda VS. 2-methoxyestradiol up-regulates death receptor 5 and induces apoptosis through activation of the extrinsic pathway. Cancer Res. 2003;63(2):468–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino E, Cardier JE. Differential effect of IL-18 on endothelial cell apoptosis mediated by TNF-alpha and Fas (CD95) Cytokine. 2003;22:142–148. doi: 10.1016/s1043-4666(03)00150-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mocellin S, Rossi CR, Pilati P, Nitti D. Tumor necrosis factor, cancer and anti-cancer therapy. Cytokine Growth Factor. 2005;16:35–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nor JE, Mitra RS, Sutorik MM, Mooney DJ, Castle VP, Polverini PH. Thrombospondin-1 induces endothelial cell apoptosis and inhibits angiogenesis by activating the caspase death pathway. J Vasc Res. 2000;37:209–218. doi: 10.1159/000025733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panka DJ, Mier JW. Canstatin inhibits Akt activation and induces Fas-dependent apoptosis in endothelial cells. J.Biol.Chem. 2003;278:37632–37636. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307339200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce FSA, Wu J, Silverstein RL. Recombinant GST/CD36 fusion proteins define a thrombospondin binding domain. Evidence for a single calcium-dependent binding site on CD36. J.Biol.Chem. 1995;270:2981–2986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.7.2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pijuan-Thompson V, Gladson CL. Ligation of integrin alpha5beta1 is required for internalization of vitronectin by integrin alphavbeta3. J.Biol.Chem. 1997;272:2736–2743. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.5.2736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiher FK, Volpert OV, Jimenez B, Crawford SE, Dinney CP, Henkin J, Haviv F, Bouck NP, Campbell SE. Inhibition of tumor growth by systemic treatment with thrombospondin-1 peptide mimectics. Int J Cancer. 2002;98(5):682–689. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Manzaneque JC, Lane TF, Ortega MA, Hynes RO, Lawler J, Iruela-Arispe ML. Thrombospondin-1 suppresses spontaneous tumor growth and inhibist activation of matrix metalloprotease-9 and mobilization of vascular endothelial growth factor. Proc Natl Acad Sc USA. 2001;98:12485–12490. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171460498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Secchiero P, Gonelli A, Carnevale E, Milani D, Pandolfi A, Zella D, Zauli G. TRAIL promotes the suvival and proliferation of primary human vascular endothelial cells by activating the Akt and ERK pathways. Circulation. 2003;107(17):2250–2256. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000062702.60708.C4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein RL, Febbraio M. CD36-TSP-HRGP interactions in the regulation of angiogenesis. Curr.Pharm.Des. 2007;13:3559–3567. doi: 10.2174/138161207782794185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simantov R, Febbraio M, Crombie R, Asch AS, Nachman RL, Silverstein RL. Histidine-rich glycoprotein inhibits the anti-angiogenic effect of thrombospondin-1. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:45–52. doi: 10.1172/JCI9061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simantov R, Silverstein RL. CD36: a critical anti-angiogenic receptor. Front Biosci. 2003;8:s874–s882. doi: 10.2741/1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprick MR, Rieser E, Stahl H, Grosse-Wilde A, Weigand MA, Walczak H. Caspase-10 is recruited to and activated at the native TRAIL and CD95 death-inducing signalling complexes in a FADD-dependent manner but can not functionally substitute caspase-8. EMBO J. 2002;21:4520–4530. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St.Croix B, Rago C, Velculescu V, Traverso G, Romans KE, Montgomery E, Lal A, Riggins GJ, Lengauer C, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Genes expressed in human tumor endothelium. Science. 2000;289:1197–1202. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5482.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoelcker B, Ruhland B, Hehlgans T, Bluethmann H, Luther T, Männel DN. Tumor necrosis factor induces tumor necrosis via tumor necrosis factor receptor type 1-expressing endothelial cells of the tumor vasculature. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:1171–1176. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64986-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornburn A. Death receptor-induced cell killing. Cell Signal. 2004;16:139–144. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolsma SS, Volpert OV, Good DJ, Frazier WA, Polverini PJ, Bouck NP. Peptides derived from two separate domains of the matrix protein thrombospondin-1 have anti-angiogenic activity. J Cell Biol. 1993;122:497–511. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.2.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varghese J, Sade H, Vandenabeele P, Sarin A. Head involution defective (Hid)-triggered apoptosis requires caspase-8 but not FADD (Fas-associated death domain) and is regulated by Erk in mammalian cells. J.Biol.Chem. 2002;277:35097–35104. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206445200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpert OV, Zaichuk T, Zhou W, Reiher F, Ferguson TA, Stuart PM, Amin M, Bouck NP. Inducer-stimulated Fas targets activated endothelium for destruction by antiangiogenic thrombospondin-1 and pigment epithelium-derived factor. Nat.Med. 2002;8:349–357. doi: 10.1038/nm0402-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Strickland DK, Bornstein P. Extracellular matrix metalloproteinase 2 levels are regulated by the low density lipoprotein-related scavenger receptor and thrombospondin 2. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:8403–8408. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008925200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Hirahashi J, Cullere X, Mayadas TN. Elucidation of molecular events leading to neutrophil apoptosis following phagocytosis: cross-talk between caspase 8, reactive oxygen species, and MAPK/ERK activation. J.Biol.Chem. 2003;278:28443–28454. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210727200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]