Abstract

Contiguous gene syndromes cause disorders via haploinsufficiency for adjacent genes. Some contiguous gene syndromes (CGS) have stereotypical breakpoints, but others have variable breakpoints. In CGS that have variable breakpoints, the extent of the deletions may be correlated with severity. The Greig cephalopolysyndactyly contiguous gene syndrome (GCPS‐CGS) is a multiple malformation syndrome caused by haploinsufficiency of GLI3 and adjacent genes. In addition, non‐CGS GCPS can be caused by deletions or duplications in GLI3. Although fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH) can identify large deletion mutations in patients with GCPS or GCPS‐CGS, it is not practical for identification of small intragenic deletions or insertions, and it is difficult to accurately characterise the extent of the large deletions using this technique. We have designed a custom comparative genomic hybridisation (CGH) array that allows identification of deletions and duplications at kilobase resolution in the vicinity of GLI3. The array averages one probe every 730 bp for a total of about 14 000 probes over 10 Mb. We have analysed 16 individuals with known or suspected deletions or duplications. In 15 of 16 individuals (14 deletions and 1 duplication), the array confirmed the prior results. In the remaining patient, the normal CGH array result was correct, and the prior assessment was a false positive quantitative polymerase chain reaction result. We conclude that high‐density CGH array analysis is more sensitive than FISH analysis for detecting deletions and provides clinically useful results on the extent of the deletion. We suggest that high‐density CGH array analysis should replace FISH analysis for assessment of deletions and duplications in patients with contiguous gene syndromes caused by variable deletions.

Keywords: GLI3 , oligonucleotide array, comparative genomic hybridization

Genetic disorders can be caused by an enormously broad range of genomic aberrations. These range from single‐nucleotide point mutations to duplications and deletions of millions of basepairs of DNA, up to entire chromosomes, as in Down's syndrome. An ongoing challenge for genetic diagnostics is to develop methods to sensitively and specifically diagnose this entire range of mutations. Although current methods reliably detect the largest and smallest mutations (microscopic cytogenetics and sequencing, respectively), the middle range of mutations is difficult to detect. We dealt with this challenge by applying the evolving technology of array‐based comparative genomic hybridisation (CGH) to a disorder that is caused by a wide range of mutations, including mutations in this intermediate range.

Haploinsufficiency of the transcription factor gene GLI3, on chromosome 7p14.1, causes Greig cephalopolysyndactyly syndrome (GCPS).1 Many mutations have been identified, including translocations and large genomic deletions, as well as small intragenic deletions or duplications2 and point mutations.2,3 This wide range of mutations complicates molecular diagnostics, requiring numerous tests to detect all possible mutations. In addition, when a deletion is detected by fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH; which does not delineate the extent of the deletion), customised reflex testing is indicated because the deletion size corresponds to prognosis in GCPS.4 By contrast, patients with typical GCPS (without the contiguous gene syndrome) can have duplications and deletions of segments of GLI3 that are too small to be readily detected by FISH and too large to be detected by sequencing or other standard mutation scanning procedures. New approaches are needed to allow detection of these intermediate aberrations.

Array CGH offers some of the advantages of FISH and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) in a single experiment. Array CGH determines the relative genomic content of two DNA specimens by competitive hybridisation. Array CGH can be performed with either large probes (bacterial artificial chromosomes, typically about 100 000 bp) or small probes (oligonucleotides). We have adapted an oligonucleotide CGH array with an extremely high‐density probe set, including approximately 14 000 probes, averaging one probe per 730 bp over a 10 Mb region centred on GLI3. The strategy was to customise an existing, validated platform of oligonucleotide CGH array that offers the potential to interrogate thousands of probes in a focused region of the genome. We hypothesised that the extremely high density of small target probes would allow us to accurately characterise a wide range of duplications and deletions. To test this system, we interrogated the GLI3 region with this custom CGH array and compared the results with prior data to determine the utility and validity of the assay.

Methods

Patients

Sixteen patients with GCPS were included in this study on the basis of having known or suspected GLI3 deletions or duplications. Patients were evaluated as described previously.2 These patients were those whom we previously concluded were hemizygotic for the locus by one or more FISH experiments, by analysis of aberrant inheritance of polymorphic markers in family studies, by qPCR dosage analysis, or by other methods.2,4 The research study was reviewed and approved by the National Human Genome Research Institute Institutional Review Board.

FISH analysis

All patients were analysed by FISH for deletions of the GLI3 locus as clinically indicated.4

DNA isolation

DNA was isolated from whole blood by the salting out method (Gentra, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA) using the manufacturer's instructions.

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

qPCR analysis of the GLI3 coding exons was performed as described previously.2

Array design

We designed a custom 44K oligonucleotide array (Agilent, Santa Clara, California, USA) maximising the probe density over a 10 Mb region centred on GLI3, with an average probe spacing of 730 bp, in this region with a total of 13 794 probes. All potential probes in the 10 Mb region that were identified as being potentially suitable for CGH were placed on the array. The rest of the genome was interrogated with 28 762 probes, for an average density of one probe every 100 kb. We retained some probes outside the GLI3 region to potentially allow detection of other cryptic aberrations.

Array hybridisation

Owing to limited amounts of DNA for some patients, initial studies were performed using whole‐genome amplification in 15 patients. These studies were followed up in 2 patients (a duplicate from the initial 15 (G17) and an additional patient (G07) not included in the original sample set) using direct labelling of genomic DNA. Owing to high background in the original array experiment for patient G17, results from the direct labelling experiment were used for this patient.

For whole‐genome amplification, 40 ng of genomic DNA from patient samples and controls (control human genomic DNA, Promega, Madison, Wisconsin, USA) were amplified using the Genomiphi Amplification Kit (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) according to the manufacturer's directions. The samples were ethanol precipitated, resuspended in 10 mM TRIS, pH 7.5, and quantitated using PicoGreen fluorescence analysis (Quant‐iT, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California, USA). Amplified DNA (5–10 μg) was labelled by random priming according to the manufacturer's directions (Bioprime, Invitrogen) with the following nucleotide concentrations: 120 μM dATP, dCTP, dGTP and 60 μM dTTP, along with 60 μM Cy3 or Cy5‐labelled dUTP. After labelling, the DNA was column purified with QIAquick PCR purification columns (Qiagen, Valencia, California, USA). Changes in the standard directions include adding 10 μl of 3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.2) to the probe before purification, and an initial wash step of 500 μl 35% guanidine HCl. The labelled DNA was eluted from the column with EB buffer prewarmed to 50°C.

Hybridisation was achieved in hybridisation chambers (Agilent). Labelled DNA of patients and control DNA of the opposite sex were combined with 50 μl CoT 1 DNA (1 μg/μl), 20 μl yeast transfer RNA (5 μg/μl) and 50 μl 10× control targets (Agilent). A volume of 250 μl 2× hybridisation buffer (Agilent) was added and the DNA was denatured at 95°C for 5 min. The DNA was incubated at 37°C for 30 min and applied to the microarray. Hybridisation was carried out with rotation for 16 h at 65°C.

Alternatively, genomic DNA was directly labelled. For these samples, 3 μg of genomic DNA was digested with Alu I and Rsa I overnight at 37°C. The restriction enzymes were inactivated at 65°C for 10 min and the DNA was purified using QIAprep Spin Miniprep Columns (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's directions for DNA purification. The DNA was eluted into 50 μl buffer EB and concentrated to 21 μl under vacuum. The DNA was labelled using the BioPrime Array CGH Genomic Labeling System (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's directions. Excess label was removed from the labelled DNA using Vivaspin Concentrators (VivaScience, Gloucestershire, UK) and resuspended to a volume of 100 μl.

Hybridisation was achieved as described earlier, with two changes. The yeast tRNA was replaced with 50 μl 10× Blocking Reagent (Agilent) and hybridisation was carried out with rotation for 40 h at 65°C.

All slides were washed, with agitation, at room temperature for 5 min in 0.5× SSC, 0.005X Triton 102, followed by a 5 min wash at 37°C in 0.1× SSC, 0.005X Triton 102. Slides were scanned on a laser‐based microarray scanner (Agilent) using standard scanning parameters.

Array analysis

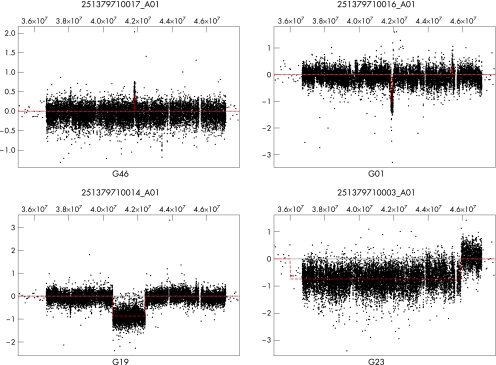

Log 2 ratios of sample DNA compared with control DNA, as calculated by the image analysis software, were used for analysis. Arrays were normalised to have a median log 2 ratio of zero for data from all chromosomes excluding 7, X and Y. The interval analysis algorithm described in Lipson et al5 was used, with a threshold of 6 to identify putative regions of gain or loss. Figure 1 shows plots of the raw data and the resulting segmentation for the region surrounding GLI3 for four representative arrays. Table 1 gives the breakpoints for the regions of gain or loss affecting GLI3 for all patients.

Figure 1 Interval analyses for four representative arrays. Base pair position on chromosome 7 is shown at the top of each panel.

Table 1 End points predicted from interval analysis for regions of gain/loss affecting GLI3.

| Patient | Array number | Telomeric breakpoint (bp)* | Centromeric breakpoint (bp)* | Gain/loss size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G46 | 251379710017 | 41 788 869 (± 183) | 41 848 330 (± 279) | 58 999 |

| G01 | 251379710016 | 41 837 786 (± 213) | 41 962 061 (± 166) | 124 109 |

| G03 | 251379710020 | 41 856 991 (± 282) | 42 008 481 (± 272) | 150 937 |

| G63 | 251379710018 | 41 875 297 (± 178) | 42 030 082 (± 355) | 154 252 |

| G36 | 251379710015 | 41 440 968 (± 192) | 42 169 544 (± 1163) | 727 222 |

| G88 | 251379710011 | 41 121 775 (± 248) | 42 127 173 (± 241) | 1 005 157 |

| G19 | 251379710014 | 40 551 830 (± 3254) | 42 436 208 (± 226) | 1 880 898 |

| G07 | 251379710008 | 40 734 205 (± 227) | 43 955 681 (± 879) | 3 220 370 |

| G76 | 251379710006 | 38 299 268 (± 3641) | 42 425 442 (± 576) | 4 121 958 |

| G29 | 251379710005 | 40 582 288 (± 522) | 45 838 055 (± 1245) | 5 254 000 |

| G17 | 251379710009 | 39 155 525 (± 257) | 45 107 964 (± 288) | 5 951 894 |

| G24 | 251379710004 | 36 615 001 (± 52 195) | 43 051 526 (± 241) | 6 384 089 |

| G21 | 251379710002 | 38 959 820 (± 518) | 47 450 897 (± 57 256) | 8 433 304 |

| G23 | 251379710003 | 36 000 459 (± 17 774) | 45 907 234 (± 4739) | 9 884 263 |

| G83 | 251379710007 | 34 710 805 (± 70 866) | 45 099 861 (± 196) | 10 388 860 |

*Positions are given for the midpoint between probes that flank the predicted breakpoints at each end of the deletion or duplication. The estimated precision of each breakpoint determination is given in parentheses, which is half the distance between the flanking probes for each deletion or duplication breakpoint.

Junction fragment analysis

PCR primers were designed using sequence information from array probes that flanked the deletion at 43 Mb on chromosome 7 in patients G17 and G46. AccuPrime Taq (Invitrogen) was used according to the manufacturer's directions to amplify across the junction. Sequence analysis was performed by direct sequencing of the junction fragment using BigDye Terminator V.3.1 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California, USA) according to the manufacturer's directions. Reactions were analysed on an ABI 3100. Nested primers were designed from sequence information to amplify a 1.3 kb junction fragment for analysis in 168 Caucasian control chromosomes.

Results

Patient analysis

Clinical manifestations for 13 of the 16 patients have been described previously.2,4 The remaining three patients, G76, G83 and G88, all fit our relaxed GCPS eligibility criteria of preaxial polydactyly and the presence of at least one additional feature (syndactyly, macrocephaly, hypertelorism, postaxial polydactyly). Patient G76 was evaluated at 15 years of age and had bilateral preaxial polydactyly of the feet, broad thumbs, macrocephaly and mental retardation. Patient G83 was evaluated at 15 months of age and had preaxial polysyndactyly of both feet, telecanthus, prominent ventricles on cranial computed tomography, bilateral inguinal hernias, coarctation of the aorta, a unilateral congenital cataract and developmental delay. Patient G88 was seen at 10 years of age and had preaxial polydactyly of the left foot, bilateral cutaneous syndactyly of the feet, an undescended testicle, strabismus and learning disabilities with poor speech articulation.

Array analysis

A total of 16 individuals with known or suspected genomic changes in GLI3 were analysed using oligonucleotide CGH array. Breakpoint analyses in four individuals had been performed previously.4 Of the other 12 individuals, 7 had deletions detected by FISH, 1 had a deletion detected by familial short tandem repeat polymorphic marker studies and 4 had changes detected by qPCR. In all, 15 of the 16 individuals had regions of gain or loss affecting GLI3 identified through interval analysis (table 1).

In addition, several recurrent intervals of gain or loss were identified on chromosome 7 that may represent copy number polymorphisms or artefacts resulting from whole‐genome amplification, with the most common occurring at 45 Mb (five patients). We repeated the array on patient G17 owing to high background using direct labelling of genomic DNA, and at least in this patient, the recurrent gain at approximately 45 Mb disappeared using direct labelling. This suggests that this recurrent gain, and possibly recurrent losses seen at 38, 39 and 41 Mb may be artefacts from DNA amplification. The recurrent loss seen in patients G17 and G46 at 43 Mb did not resolve with direct labelling. Junction fragment analysis showed this deletion to be present in the unaffected mother of G17 and absent from the affected sibling of G46. In addition, we tested 84 controls for presence of the unique junction fragment formed by this deletion and found it in 11 individuals (13.1%; data not shown). The presence of this deletion in 13.1% of the controls supports the theory that it is a copy number polymorphism.

In three patients, G03, G17 and G36, deletion breakpoints had previously been cloned and sequenced. With the exception of the centromeric breakpoint in patient G03, which was shifted by one probe, breakpoints identified using interval analysis agreed with those previously identified through sequence analysis. Patient G21 had previously been analysed using monoallelic somatic cell hybrids; however, the breakpoints in this patient were not cloned owing to gaps in the genome sequence assembly available at that time. The size of the deletion in patient G21 was predicted to be 10.6 Mb in length based on sequence‐tagged site analysis of hybrid DNA from this patient. Array analysis agreed with the telomeric end point but predicted a different placement of the centromeric end point, with a resulting deletion size of 8.5 Mb (May 2004 Browser). Although the result from the hybrid DNA was based on three independent PCR experiments (absence of product used as proof of deletion), the breakpoint determined from the interval analysis is based on signals from 15 independent array probes covering 1.2 Mb.

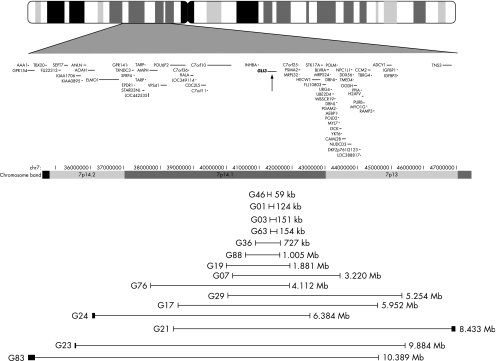

Of the 10 patients without previously analysed breakpoints, 3 (G24, G23 and G83) had a single breakpoint that fell outside the 10 Mb region. All these patients had large deletions, >5 Mb in length (encompassing the GLI3 gene and at least half of the 10 Mb region). Figure 2 shows the extent of the deletions or duplications for all patients.

Figure 2 Diagram of deletions or duplications on chromosome 7 (chr7) identified by the arrays. Vertical lines depict end points for the deletions, with the thickness approximating the distance between probes defining the end point. An ideogram of chromosome 7 is shown at the top of the diagram. Base pair position on chromosome 7 and genes in the region, as reported in RefSeq (May 2004 Browser), are shown below the ideogram. The location of GLI3 is marked with an arrow.

One patient, G67, did not have a detectable change. This patient previously had abnormal results (deleted) for exon 2 on qPCR analysis.2 Further analysis of the primer‐binding sites used in the qPCR reaction showed the presence of a previously unrecognised sequence polymorphism underlying the qPCR primer site. As this polymorphism corresponded with the 3′ end of the primer, it is predicted to amplify only one allele, accounting for the determination that this amplicon was deleted in the patient (data not shown). We conclude that the qPCR result in that case was a false positive.

Discussion

Molecular diagnostics for disorders with a wide range of mutation types is challenging. In a clinical setting, the number of tests required to identify a single mutation, the cost of those tests and the sensitivity of those tests are all important factors. In addition, it is sometimes necessary to perform additional reflex tests to further characterise a mutation if the original assay does not completely delineate the mutation (eg, sequencing is necessary to confirm results from conformational scanning by SSPE or denaturing high‐performance liquid chromatography). In the case of GCPS, there is a wide range of mutation types that require several tests to identify all possible mutations. This is complicated by the fact that a large fraction of patients who are referred for testing will not have an identifiable mutation.2 For these patients, it may be necessary to perform many or all of the possible tests to attempt to find a mutation. In light of this, streamlining the diagnostic procedure without reducing sensitivity is important.

The critical problem with GCPS is that it can be caused by many mutations in GLI3. A substantial fraction of patients with GCPS have deletions or duplications. Many of these are too small to be identified by a 550 band karyotype and too large to be identified by PCR‐based sequencing or conformation scanning. To further complicate the situation, all patients identified to date as having deletions and duplications have unique breakpoints and a wide range of segmental aneusomy. Finally, the extent of the aneusomy is correlated with prognosis.4 Although GCPS has a low overall rate of mental retardation and other central nervous system abnormalities, nearly all of the patients at risk for these complications are those with large deletions (>2 Mb). Therefore, this is a technically challenging problem, with high clinical relevance and utility.

The problem with FISH and large‐clone array CGH analyses is that they only detect a limited size range of deletions. For example, bacterial artificial chromosome‐based FISH or CGH has substantially reduced sensitivity for deletions or duplications that are considerably smaller than about half the average size of the clone (on average, about 100 000 bp). Although smaller FISH probes can be used to increase sensitivity, the size of the region would mandate numerous probes be used to cover the entire gene (300 kb). Even cosmid probes (typically 40 kb) cannot reliably detect deletions or duplications <20 kb. Further, these assays cannot accurately determine the extent of the deletions or duplications without follow‐up assays. Our goal was to design an assay that would be sensitive and specific for a wide range of duplications and deletions to give the clinician a precise assessment of the extent of the change. In this context, it is important to distinguish GCPS from disorders that have stereotypical deletion breakpoints, such as Williams or DiGeorge syndromes. In these syndromes, the determination of an abnormal FISH signal is associated with a predictable set of breakpoints in >90–95% of patients.6,7 In addition, the phenotype of patients with these disorders does not predictably correlate with the extent of the atypical deletion breakpoints. As GCPS does not have these attributes, new approaches were needed.

We have designed a custom oligonucleotide CGH array that detects deletions ranging from the kilobase range through multi‐megabase‐sized deletions. Further, this array can allow deletion breakpoints to be identified (in a 10 Mb region centred on GLI3) to the kilobase range. Outside this region, probe density drops and deletion end points can be localised on average to 100 kb. This test was designed with lower resolution far from GLI3 because there is no known correlation of deletion size beyond 5 Mb with the severity of the phenotype, as it seems to be uniformly poor, and higher resolution in these regions is unnecessary for clinical purposes. In addition, deletions that encompass >3 Mb may be identified by a 550 band karyotype, which is essential for the identification of balanced translocations.

On the basis of these results, we propose the following diagnostic steps for patients who present with GCPS: standard 550 band resolution G‐banded karyotype, high‐resolution array CGH and sequencing. We recommend that all patients with a clinical diagnosis of GCPS should first have a standard G‐banding with trypsin Giemsa (GTG)‐banded karyotype to identify balanced translocations. This test may also identify large deletions (3 Mb), which could be further analysed by FISH analysis or array CGH to verify that GLI3 is deleted. In patients without cytogenetic findings, the second test can be either zoom‐in CGH array analysis or sequencing analysis. In situations where the clinical picture suggests a contiguous gene disorder, the second test should be zoom‐in CGH. In all other situations, the choice of the second assay may depend on laboratory preferences, taking into consideration the time each test takes to run, the likelihood of finding a mutation and the cost.

The results reported here for patients with GCPS with known or suspected genomic changes suggest that array CGH is useful in both identifying and precisely delineating genomic deletions and duplications of GLI3. The primary advantage of this assay is that it both detects and characterises the extent of the deletion in a single assay. We conclude that high‐resolution oligonucleotide CGH is superior to FISH or large‐clone array CGH for the characterisation of GLI3 deletions because of their variable extent and the correlation of these aberrations with the clinical outcome of the patients.

Key points

Greig cephalopolysyndactyly (GCPS) can be caused by GLI3 deletions or duplications of widely varying sizes. When the deletion is large and includes other genes, it is termed Greig cephalopolysyndactyly‐contiguous gene syndrome (GCPS‐CGS). In patients with GCPS‐CGS, deletion size correlates with disease severity.

Unlike many other microdeletion syndromes such as Williams or DiGeorge syndrome, to date, all patients with GCPS‐CGS have unique breakpoints.

Owing to the size of the gene (300 kb) and the variable deletion breakpoints (59 kb–10.4 Mb), fluorescence in situ hybridisation analysis is an inefficient method to screen for GLI3 deletions.

Zoom‐in array comparative genomic hybridisation allows for a large range of deletions or duplications to be identified and the extent of these deletions or duplications to be defined in a single experiment.

Acknowledgements

We thank Julia Fekecs for graphics support.

Abbreviations

CGH - comparative genomic hybridisation

CGS - contiguous gene syndrome

FISH - fluorescence in situ hybridisation

GCPS - Greig cephalopolysyndactyly

qPCR - quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Vortkamp A, Gessler M, Grzeschik K H.GLI3 zinc‐finger gene interrupted by translocations in Greig syndrome families. Nature 1991352539–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnston J J, Olivos‐Glander I, Killoran C, Elson E, Turner J T, Peters K F, Abbott M H, Aughton D J, Aylsworth A S, Bamshad M J, Booth C, Curry C J, David A, Dinulos M B, Flannery D B, Fox M A, Graham J M, Grange D K, Guttmacher A E, Hannibal M C, Henn W, Hennekam R C, Holmes L B, Hoyme H E, Leppig K A, Lin A E, Macleod P, Manchester D K, Marcelis C, Mazzanti L, McCann E, McDonald M T, Mendelsohn N J, Moeschler J B, Moghaddam B, Neri G, Newbury‐Ecob R, Pagon R A, Phillips J A, Sadler L S, Stoler J M, Tilstra D, Walsh Vockley C M, Zackai E H, Zadeh T M, Brueton L, Black G C, Biesecker L G. Molecular and clinical analyses of Greig cephalopolysyndactyly and Pallister‐Hall syndromes: robust phenotype prediction from the type and position of GLI3 mutations. Am J Hum Genet 200576609–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalff‐Suske M, Wild A, Topp J, Wessling M, Jacobsen E M, Bornholdt D, Engel H, Heuer H, Aalfs C M, Ausems M G, Barone R, Herzog A, Heutink P, Homfray T, Gillessen‐Kaesbach G, Konig R, Kunze J, Meinecke P, Muller D, Rizzo R, Strenge S, Superti‐Furga A, Grzeschik K H. Point mutations throughout the GLI3 gene cause Greig cephalopolysyndactyly syndrome. Hum Mol Genet 199981769–1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnston J J, Olivos‐Glander I, Turner J, Aleck K, Bird L M, Mehta L, Schimke R N, Heilstedt H, Spence J E, Blancato J, Biesecker L G. Clinical and molecular delineation of the Greig cephalopolysyndactyly contiguous gene deletion syndrome and its distinction from acrocallosal syndrome. Am J Med Genet 2003123A236–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lipson D, Aumann Y, Ben‐Dor A, Linial N, Yakhini Z. Efficient calculation of interval scores for DNA copy number data analysis. Proceeding of the RECOMB. 2005. Heidelberg: Spinger‐Velag, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Edelmann L, Pandita R K, Spiteri E, Funke B, Goldberg R, Palanisamy N, Chaganti R S, Magenis E, Shprintzen R J, Morrow B E. A common molecular basis for rearrangement disorders on chromosome 22q11. Hum Mol Genet 199981157–1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bayes M, Magano L F, Rivera N, Flores R, Perez Jurado L A. Mutational mechanisms of Williams‐Beuren syndrome deletions. Am J Hum Genet 200373131–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]