Abstract

Familial non‐Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) is rare and in most cases, no underlying cause is identifiable. We report homozygous truncating mutations in the mismatch repair gene MSH2 (226C→T; Q76X) in three siblings who each developed T‐cell NHL in early childhood. All three children had hyperpigmented and hypopigmented skin lesions.

Constitutional biallelic MSH2 mutations have previously been reported in five individuals, all of whom developed malignancy in childhood. Familial lymphoma has not been reported in this context or in association with biallelic mutations in the other mismatch repair genes MLH1, MSH6 or PMS2. In addition, hypopigmented skin lesions have not previously been reported in biallelic MSH2 carriers. Our findings therefore expand the spectrum of phenotypes associated with biallelic MSH2 mutations and identify a new cause of familial lymphoma. Moreover, the diagnosis has important management implications as it allows the avoidance of chemotherapeutic agents likely to be ineffective and mutagenic in the proband, and the provision of cascade genetic testing and tumour screening for relatives.

Keywords: DNA mismatch repair, MSH2, non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma, hereditary non‐polyposis colorectal cancer

Familial non‐Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) is rare, particularly with onset in childhood. Families with multiple cases of NHL due to genetic conditions such as ataxia telangiectasia and primary immunodeficiency disorders have rarely been reported.1 However, in most familial clusters of lymphoma, no cause is identifiable. Constitutional biallelic (recessive) mutations in the mismatch repair (MMR) gene MSH2 have previously been reported in only five individuals from three families who presented with a range of malignancies, including one with NHL (table 1).2,3,4 Familial lymphoma has not previously been described in this context or in association with biallelic mutations in the related MMR genes MLH1, MSH6 and PMS2. The phenotypes associated with mutations in these four genes overlap considerably and can usefully be considered under the collective term mismatch repair deficiency (MMR‐D) syndrome. Heterozygous (monoallelic) mutations in these genes have been recognised for >10 years as causing hereditary non‐polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC), an autosomal dominant cancer syndrome associated with an increased risk of colorectal tumours in adulthood.5 Individuals with HNPCC are also at increased risk of several other malignancies including endometrial carcinoma, gastric carcinoma and transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary tract. The association of biallelic mutations in MMR genes with childhood cancer has only been appreciated relatively recently, and the diagnosis is frequently delayed or mistaken for other conditions such as neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1). Early diagnosis of children with constitutional MMR deficiency is necessary for optimum management of the child and the wider family, and it is therefore important that there is improved recognition of the phenotypes associated with biallelic MMR gene mutations.

Table 1 Details of cases reported with biallelic MSH2 mutations.

| Family | Paternal mutation | Maternal mutation | Case | Malignancy | Age at diagnosis of malignancy (years) | Hyper‐ pigmented skin lesions | Other features | Reference | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleotide change | Effect | Nucleotide change | Effect | |||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 1662‐1G→A | Splice defect | 1662‐1G→A | Splice defect | T‐ALL | 2 | Yes | IgA deficiency | 2 | |||||||||||

| 2 | Exon 1‐6 del | Deletion of exons 1‐6 | 454delA | M152fs | IV.1 | Mediastinal T‐NHL | 1.25 | Not stated | 3 | |||||||||||

| IV.2 | Glioblastoma | 3 | Not stated | |||||||||||||||||

| 3 | 2006‐5T→A | Probable splice defect | 2006‐5T→A | Probable splice defect | 1 | CRC | 12 | Yes | Colonic and duodenal polyps | 4 | ||||||||||

| 2 | CRC | 11 | Yes | Colonic and duodenal polyps | ||||||||||||||||

| 4 | 226C→T | Q76X | 226C→T | Q76X | IV.1 | Mediastinal T‐NHL | 0.4 | Yes | Hypopigmented skin lesions | This study | ||||||||||

| IV.2 | Mediastinal T‐NHL | 2.5 | Yes | Hypopigmented skin lesions, colonic adenomas | ||||||||||||||||

| IV.3 | Mediastinal T‐NHL | 2.5 | Yes | Hypopigmented skin lesions, cystic pulmonary mass | ||||||||||||||||

CRC, colorectal carcinoma; T‐ALL, T‐cell acute lymphocytic leukaemia; T‐NHL, T‐cell non‐Hodgkin lymphoma.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Family FACT24

The proband, a 2.5‐year‐old boy, from a family referred to as FACT24, presented to his paediatrician in Kuwait with multiple chest infections and increasing shortness of breath. A CT scan showed an anterior mediastinal mass, and a histological diagnosis of T‐cell lymphoblastic NHL was made. The child was noted to have widespread hyperpigmented and hypopigmented skin lesions. Examination was otherwise normal.

The child was the second born to consanguineous parents (first cousins) of Middle‐Eastern ancestry. His older brother, who had similar skin lesions, had developed T‐NHL aged 5 months and died of the disease aged 15 months. Family history was otherwise unremarkable, identifying only that the paternal grandmother had developed colorectal carcinoma at the age of 65 years. Given the presence of hyperpigmented skin lesions, NF1 was considered to be the most likely underlying diagnosis, despite the lack of other features of NF1 in the children or other family members. The proband was treated according to the BFM NHL 95 protocol.6 Following the patient's transfer to our institution for further care, his treatment was continued according to Regimen B of the MRC ALL 97/99 protocol and he continued to show a good radiological response.7 However, a CT scan performed 2 weeks after completion of maintenance treatment revealed recurrence of a mediastinal mass. Reinduction was undertaken according to the MRC ALL R3 protocol, omitting cyclophosphomide.8 The patient received a matched allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplant from his mother following conditioning with etoposide and total body irradiation. Engraftment was successful.

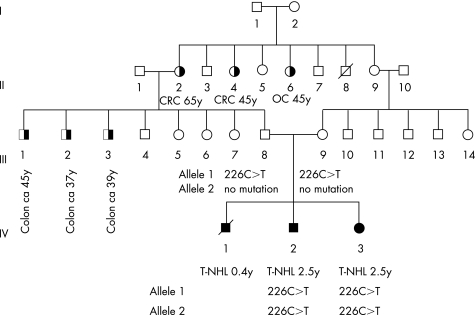

On reviewing the family, we considered that the occurrence of disease in siblings born to consanguineous and unaffected parents favoured an autosomal recessive condition. Pigmentary skin abnormalities and predisposition to lymphoma have been reported in individuals with (recessively inherited) chromosome breakage disorders, including Nijmegen breakage syndrome.9 These disorders are typically associated with growth retardation/microcephaly and variable additional dysmorphic features. The proband's height and head circumference were >50th centile for his age, and no dysmorphic features were identified, arguing against a chromosome breakage disorder. Skin hyperpigmentation and predisposition to lymphoma has also been described in association with biallelic mutations in MMR genes.3 The phenotype observed with such mutations does not include growth retardation or dysmorphism. However, cancers typical of HNPCC would be expected in relatives, particularly in individuals with MMR‐D caused by MSH2 or MLH1 deficiency, both of which are associated with high risks of cancer in heterozygote mutation carriers. We therefore undertook a more detailed family history, which revealed that three of the proband's paternal uncles had recently developed colorectal carcinoma and that there were further adults with colorectal and other tumours (fig 1), consistent with heterozygosity for an MMR gene mutation in relatives.

Figure 1 Pedigree of family FACT24. Filled symbols indicate individuals with a history of malignancy in childhood; half‐filled symbols indicate individuals with a history of malignancy in adulthood. Details of the malignancy and age of diagnosis in years are given beneath. Where known, details of MSH2 mutations are also given. CRC, colonic carcinoma; OC, ovarian carcinoma; T‐NHL, T‐cell non‐Hodgkin lymphoma.

At the age of 6 years, after the underlying mutations had been identified, the proband developed rectal bleeding. Colonoscopy identified more than 20 colonic adenomas, which were predominantly left‐sided but present from sigmoid colon to caecum. The polyps were removed endoscopically, revealing mild to moderate dysplasia but no evidence of carcinoma.

During the course the proband's treatment, a younger sister was born. Antenatal ultrasound scans had identified a cystic pulmonary mass. At birth, she was noted to have widespread hyperpigmented and hypopigmented skin lesions similar to those found in her brothers (fig 2). Recently, at the age of 2.5 years, she was diagnosed with T‐cell lymphoblastic lymphoma. She is currently undergoing induction therapy consisting of systemic vincristine, daunorubicin, cytarabine, cyclophosphamide and mercaptopurine and intrathecal methotrexate.

Figure 2 Photograph of hyperpigmented and hypopigmented skin lesions in the proband's affected sister. Informed consent was obtained for publication of this figure.

Molecular analyses

We undertook direct sequencing of the complete coding sequences and intron–exon boundaries of MSH2 and MLH1 on genomic DNA from the proband. Mutational analyses of these genes were prioritised above analyses of PMS2 and MSH6 because of the presence of a relatively strong family history of colorectal cancer. Sequencing of exon 2 of MSH2 was performed on genomic DNA from the proband's sister and parents.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

A homozygous truncating mutation in exon 2 of MSH2 (226C→T; Q76X) was identified in the proband and his sister. Both parents are heterozygous for this mutation. Constitutional biallelic mutations in MSH2 have previously been reported in five individuals from three families, all of whom developed malignancy at a young age (table 1).2,3,4 Mediastinal T‐cell lymphoma was diagnosed in one individual3 and acute T‐cell leukaemia in another.2 Colonic carcinoma and glioblastoma have also been reported. Constitutional biallelic mutations in the related MMR genes MLH1, MSH6 and PMS2 are associated with similar phenotypes and can be collectively considered under the title of MMR‐D syndrome. There is a greatly increased risk of a variety of malignancies in MMR‐D syndrome. Most of the almost 50 cases now reported have developed malignancy in childhood.10,11,12,13,14 Haematological malignancies are often described (21 individuals including family FACT24), with lymphomas being the most common malignancy (12 individuals). Eight of the 12 lymphomas described were NHL. Malignant brain tumours, usually gliomas, and colorectal carcinomas are also common. Although the nature of the cystic pulmonary lesion in the sister of the proband remains unclear, no similar pathology has been described in MMR‐D syndrome.

FACT24 is the first MMR‐D syndrome pedigree to be reported with familial lymphoma. The reasons for the particular propensity of the siblings reported here to develop lymphoma, and in particular mediastinal T‐NHL, remain unclear. It is notable that five of the eight published individuals with biallelic MSH2 mutations have developed T‐cell malignancy (table 1). In addition, familial lymphoma has been reported in pedigrees with features suggestive of MMR‐D syndrome but without a molecular diagnosis.15 Mice nullizygous for MSH2 and other MMR genes are predisposed to haematological malignancy.16

Hyperpigmented skin lesions or café‐au‐lait patches were described in three of the five individuals previously reported with biallelic MSH2 mutations and are common in those with biallelic mutations in the other MMR genes.10,11,14 As a result, an initial diagnosis of NF1 is often made, even in the absence of other features of NF1, delaying the identification of the underlying MMR deficiency. However, the hyperpigmented skin lesions in MMR‐D syndrome are not typical of the café‐au‐lait patches seen in NF1, varying in their degree of pigmentation and often having irregular borders.17 Hypopigmented skin lesions have not been described previously in biallelic MSH2 carriers (fig 2). This report and our recent description of similar lesions in a patient harbouring biallelic MSH6 mutations indicate that hypopigmentation may not be an infrequent finding in MMR‐D syndrome.14 Careful examination and the use of Wood's light may be required in order to ensure that such lesions are not overlooked. Hypopigmentation is not a feature of NF1 and, when present, is a useful means of differentiating MMR‐D syndrome from NF1.

Constitutional monoallelic (heterozygous) mutations in MSH2 and the other MMR genes, MLH1, MSH6 and PMS2, cause HNPCC. Given the young age at which children with MMR‐D syndrome develop tumours, they will often present before their parents, aunts and uncles who carry single mutations. Hence, as in the family described, there may not be a family history suggestive of HNPCC when the child first presents. A high index of suspicion and extensive documentation of family history will often therefore be required to make the diagnosis. The identification of MMR gene mutations in a child allows cascade genetic testing and tumour screening for relatives carrying a single mutation.18

The MMR system plays an important role in the cytotoxicity of several chemotherapeutic agents, including O6 methylators such as temozolomide.19,20 MMR‐deficient cells are profoundly resistant to the cytotoxicity of O6 methylators, and demonstrate a point‐mutator phenotype following exposure to these agents.19,21 This suggests that O6 methylators are likely to be highly mutagenic as well as ineffective in individuals with MMR‐D syndrome, and their use may increase the risk of tumour relapse and/or the development of second primary tumours.21 Early diagnosis of the underlying genetic syndrome is therefore important, as it offers the opportunity to carefully consider the optimum chemotherapeutic regimen.

In summary, this report identifies a new cause of familial lymphoma and expands the range of phenotypes associated with constitutional biallelic MSH2 mutations to include familial lymphoma and hypopigmented skin lesions. MMR‐D syndrome should be considered in any individual presenting with pigmentary skin abnormalities and childhood malignancy, even in the absence of a strong family history of tumours. Early diagnosis of MMR‐D syndrome is important as it allows the selection of an appropriate chemotherapeutic regimen for the proband, as well as cascade genetic testing and screening of relatives who harbour a single MMR gene mutation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Informed consent for the research and publication of this report including photographs was obtained from the patients' parents. This work is part of the Factors Associated with Childhood Tumours (FACT) study, which is a Children's Cancer and Leukaemia Group (CCLG) study. The study has been approved by the London Multicentre Research Ethics Committee (05/MRE02/17).

Abbreviations

HNPCC - hereditary non‐polyposis colorectal cancer

MMR - mismatch repair

MMR‐D - mismatch repair deficiency

NF1 - neurofibromatosis type 1

NHL - non‐Hodgkin lymphoma

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Institute of Cancer Research (UK). RS is supported by a grant that forms part of the Michael and Betty Kadoorie Cancer Genetics Research Programme.

Competing interests: None declared.

Informed consent was obtained for publication of figure 2.

References

- 1.Linet M S, Pottern L M. Familial aggregation of hematopoietic malignancies and risk of non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma. Cancer Res 1992525468–73s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whiteside D, McLeod R, Graham G, Steckley J L, Booth K, Somerville M J, Andrew S E. A homozygous germ‐line mutation in the human MSH2 gene predisposes to hematological malignancy and multiple cafe‐au‐lait spots. Cancer Res 200262359–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bougeard G, Charbonnier F, Moerman A, Martin C, Ruchoux M M, Drouot N, Frebourg T. Early onset brain tumour and lymphoma in MSH2‐deficient children. Am J Hum Genet 200372213–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muller A, Schackert H K, Lange B, Ruschoff J, Fuzesi L, Willert J, Burfeind P, Shah P, Becker H, Epplen J T, Stemmler S. A novel MSH2 germline mutation in homozygous state in two brothers with colorectal cancers diagnosed at the age of 11 and 12 years. Am J Med Genet A 2006140195–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lynch H T, de la Chappelle A. Hereditary colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2003348919–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woessmann W, Seidemann K, Mann G, Zimmermann M, Burkhardt B, Oschlies I, Ludwig W D, Klingebiel T, Graf N, Gruhn B, Juergens H, Niggli F, Parwaresch R, Gadner H, Riehm H, Schrappe M, Reiter A, BFM Group The impact of methotrexate administration schedule and dose in the therapy of children and adolescents with B‐cell neoplasms: A report of the BFM study NHL‐BFM 95. Blood 2005105948–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roy A, Bradburn M, Moorman A V, Burrett J, Love S, Kinsey S E, Mitchell C, Vora A, Eden T, Lilleyman J S, Hann I, Saha V. Medical Research Council Childhood Leukaemia Working Party. Early response to induction is predictive of survival in childhood Philadelphia chromosome positive acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: results of the Medical Research Council ALL 97 trial, Br J Haematol 200512935–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lawson S E, Harrison G, Richards S, Oakhill A, Stevens R, Eden O B, Darbyshire P J. The UK experience in treating relapsed childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: a report on the medical research council UKALLR1 study. Br J Haematol 2000108531–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van der Burgt I, Chrzanowska K H, Smeets D, Weemaes C. Nijmegen breakage syndrome. J Med Genet 199633153–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ostergaard J R, Sunde L, Okkels H. Neurofibromatosis von Recklinghausen type I phenotype and early onset of cancers in siblings compound heterozygous for mutations in MSH6. Am J Med Genet A 200513996–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Plaschke J, Linnebacher M, Kloor M, Gebert J, Cremer F W, Tinschert S, Aust D E, von Knebel Doeberitz M, Schackert H K. Compound heterozygosity for two MSH6 mutations in a patient with early onset of HNPCC‐associated cancers, but without hematological malignancy and brain tumour. Eur J Hum Genet 200614561–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gallinger S, Aronson M, Shayan K, Ratcliffe E M, Gerstle J T, Parkin P C, Rothenmund H, Croitoru M, Baumann E, Durie P R, Weksberg R, Pollett A, Riddell R H, Ngan B Y, Cutz E, Lagarde A E, Chan H S. Gastrointestinal cancers and neurofibromatosis type 1 features in children with a germline homozygous MLH1 mutation. Gastroenterology 2004126576–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raevaara T E, Gerdes A M, Lonnqvist K E, Tybjaerg‐Hansen A, Abdel‐Rahman W M, Kariola R, Peltomaki P, Nystrom‐Lahti M. HNPCC mutation MLH1 P648S makes the functional protein unstable, and homozygosity predisposes to mild neurofibromatosis type 1. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 200440261–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scott R H, Mansour S, Pritchard‐Jones K, Kumar D, MacSweeney F, Rahman N. Medulloblastoma, acute myelocytic leukemia and colonic carcinomas in a child with biallelic MSH6 mutations. Nat Clin Pract Oncol 20074130–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaplan J, Cushing B, Chang C H, Poland R, Roscamp J, Perrin E, Bhaya N. Familial T‐cell lymphoblastic lymphoma: association with Von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis and Gardner syndrome. Am J Hematol 198212247–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wei K, Kucherlapati R, Edelmann W. Mouse models for human DNA mismatch‐repair gene defects. Trends Mol Med 20028346–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Vos M, Hayward B E, Charlton R, Taylor G R, Glaser A W, Picton S, Cole T R, Maher E R, McKeown C M, Mann J R, Yates J R, Baralle D, Rankin J, Bonthron D T, Sheridan E. PMS2 mutations in childhood cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 200698358–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Comprehensive Cancer Network: Colorectal cancer screening: clinical practice guidelines in oncology J Nat Comp Cancer Net. 2003;1:72–93. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2003.0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fedier A, Fink D. Mutations in DNA mismatch repair genes: implications for DNA damage signaling and drug sensitivity (review). Int J Oncol 2004241039–1047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allan J M, Travis L B. Mechanisms of therapy‐related carcinogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer 20055943–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hunter C, Smith R, Cahill D P, Stephens P, Stevens C, Teague J, Greenman C, Edkins S, Bignell G, Davies H, O'Meara S, Parker A, Avis T, Barthorpe S, Brackenbury L, Buck G, Butler A, Clements J, Cole J, Dicks E, Forbes S, Gorton M, Gray K, Halliday K, Harrison R, Hills K, Hinton J, Jenkinson A, Jones D, Kosmidou V, Laman R, Lugg R, Menzies A, Perry J, Petty R, Raine K, Richardson D, Shepherd R, Small A, Solomon H, Tofts C, Varian J, West S, Widaa S, Yates A, Easton D F, Riggins G, Roy J E, Levine K K, Mueller W, Batchelor T T, Louis D N, Stratton M R, Futreal P A, Wooster R. A hypermutation phenotype and somatic MSH6 mutations in recurrent human malignant gliomas after alkylator chemotherapy. Cancer Res 2006663987–3991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]