Abstract

Background

The dystrophic forms of epidermolysis bullosa (DEB), a group of heritable blistering disorders, show considerable phenotypic variability, and both autosomal dominant and autosomal recessive inheritance can be recognised. DEB is derived from mutations in the type VII collagen gene (COL7A1), encoding a large collagenous protein that is the predominant, if not exclusive, component of the anchoring fibrils at the dermal–epidermal junction.

Methods

The Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa Research Association Molecular Diagnostics Laboratory (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA), established in 1996, has analysed more than 1000 families with different forms of epidermolysis bullosa, among them 332 families with DEB. DNA specimens were subjected to mutation analysis by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of all 118 exons and flanking intronic sequences of COL7A1, followed either by heteroduplex scanning and sequencing of the PCR products demonstrating heteroduplexes or by direct nucleotide sequencing.

Results

355 mutant alleles out of the anticipated 438 (81.1%) were disclosed. Among these mutations, a total of 242 mutations were distinct and 138 were novel, previously unreported mutations. No evidence of mutations in any other gene was obtained.

Discussion

Examination of the mutation database suggested phenotype–genotype correlations, contributing to the improved subclassification of DEB with prognostic implications. The mutation information also forms the basis for accurate genetic counselling and prenatal diagnosis in families at risk for recurrence.

Epidermolysis bullosa, a group of heritable blistering diseases with considerable clinical and genetic heterogeneity, has been divided into distinct subtypes depending on the level of tissue separation in the dermal–epidermal basement membrane zone.1 Currently, 10 distinct genes are known to harbour mutations in the different subtypes of epidermolysis bullosa.2 The dystrophic forms of epidermolysis bullosa (DEB) are characterised by tense blisters and erosions that heal with extensive, either atrophic or hypertrophic, scarring (table 1).

Table 1 Clinically recognised subtypes of the dystrophic forms of epidermolysis bullosa and allelic blistering disorders with mutations in the type VII collagen gene.

| Variant | Clinical features | Electron microscopy findings/immunofluorescence | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dominant DEB | |||

| Pasini | Relatively severe, more generalised distribution of lesions, although mostly on acral skin areas, albopapuloid lesions on trunk, oral blisters, nail dystrophy, scarring or milia in regular and symmetric patterns over the joints | Sublamina densa blisters, hypoplastic AF in normal and affected areas of skin; positive, yet attenuated type VII collagen staining | |

| Cockayne‐Touraine | Relatively mild, lesions localised to extremities, atrophic scarring, nail dystrophy | Sublamina densa blisters, reduced hypoplastic AF in affected areas of skin, normal AF in unaffected areas; normal type VII collagen staining | |

| Recessive DEB | |||

| Hallopeau‐Siemens | Generalised skin involvement with blisters more frequent on acral skin regions, mutilations, synechias, flexion contractures of joints due to extensive scarring, milia, congenital skin defects, oral blisters, oesophageal stenosis, eye involvement, anaemia, growth and developmental retardation, high risk of skin cancer | Sublamina densa blisters, absent AF; negative immunostaining for type VII collagen | |

| Non‐Hallopeau‐Siemens (including mitis, localised and inverse) | Broad range of severity, although relatively mild compared with Hallopeau‐Siemens subtype, blisters on trunk and extremities, oral blisters, oesophageal stenosis | Sublamina densa blisters, degree of AF reduction or hypoplasia correlates with degree of clinical severity; reduced immunostaining for type VII collagen | |

| Related conditions | |||

| Pretibial | Pretibial skin and dorsal feet involvement, nail dystrophy | Sublamina densa blisters, abnormal AF in affected skin only; reduced immunostaining for type VII collagen | |

| Pruriginosa | Highly pruritic, violaceous, cutaneous nodules mostly on the limbs, nail dystrophy, scarring especially of ankles, variable age of onset as late as 10 years | Sublamina densa blisters, reduced number of normal‐appearing AF or with subtle changes in morphology; normal or near‐normal expression of type VII collagen | |

| Bart's syndrome | Sharply demarcated, depressed, eroded areas on acral body sites, congenital localised absence of skin, blisters common on extremities, nail dystrophy | ||

| Transient bullous dermolysis of the newborn | Generalised blisters at birth, course usually limited to 1–2 years of life with no further skin fragility or blistering | Sub‐lamina densa blisters, reduced number of hypoplastic AF, intracellular accumulation of type VII collagen with gradual recovery in type VII collagen secretion, and subsequent improvement or correction of AF morphology | |

| EBS superficialis | Atrophic scarring, milia, nail dystrophy, oral blisters | Intraepidermal cleavage reported in one family; normal type VII collagen staining | |

AF, anchoring fibrils; DEB, dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa; EBS, epidermolysis bullosa simplex.

Modified from Anton‐Lamprecht et al.3

The scarring tendency reflects the fact that blister formation in DEB occurs below the lamina densa of the cutaneous basement membrane, eliciting a mesenchymal wound‐healing response in the dermis. In addition to cutaneous blisters and erosions, the gastrointestinal tract, particularly the oesophagus, is affected by blistering and scarring. Furthermore, patients with DEB can have corneal erosions, dystrophy and loss of nails, and scarring alopecia.4 In the most severe forms of DEB, scarring can result in joint contractures and pseudosyndactyly, with a major effect on the quality of life of the affected people. The extensive scarring on the hands and feet is often associated with the development of aggressive, rapidly metastasising squamous‐cell carcinomas, which can lead to early death.4 The spectrum of clinical severity in DEB is, however, highly variable, with milder forms of the disease showing a limited tendency to blistering or nail involvement. The fact that DEB can be inherited either in an autosomal dominant (DDEB) or autosomal recessive (RDEB) pattern adds to its clinical heterogeneity.

Early genetic linkage analysis mapped DEB to the short arm of chromosome 3, region 3p21.1, and subsequently, several mutations in the type VII collagen gene, COL7A1, have been identified.2,5 COL7A1 is an unusually complex gene, consisting of 118 exons in approximately 32 kb of the human genome.6 The corresponding mRNA, approximately 9 kb in size, encodes a 350‐kDa proα1(VII) polypeptide with a distinct structural domain organisation.7 The central portion of the molecule consists of a collagenous segment with a Gly–X–Y repeat sequence that folds into the characteristic collagenous triple helical conformation. In contrast with the classic interstitial collagens, such as collagen types I–III, the triple helix in type VII collagen is interrupted by small deletions or insertions, including a 39‐amino acid non‐collagenous insertion in the middle of the collagenous domain. The central collagenous domain is flanked by a large, approximately 145‐kDa, non‐collagenous amino‐terminal globular domain (NC1), and a smaller, approximately 20‐kDa, carboxy‐terminal globular domain (NC2). NC1 consists of submodules with homology to known adhesive proteins, including cartilage matrix protein, nine consecutive fibronectin type III‐like domains and a segment with homology to the von Willebrand factor A domain.8 NC2 has a segment with homology to the Kunitz protease inhibitor, but its functionality has not been established.7

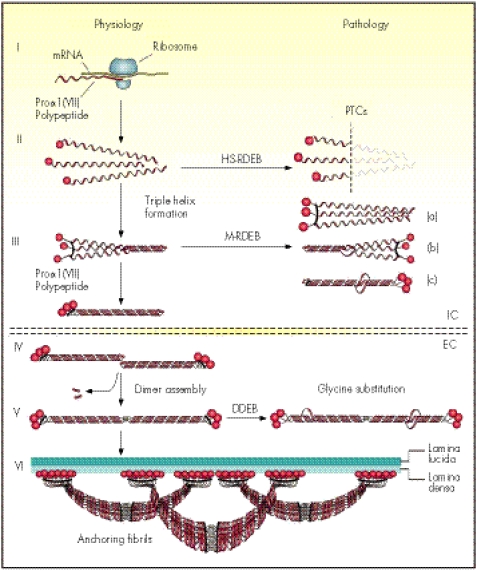

Type VII collagen is synthesised primarily by epidermal keratinocytes, which are probably the major source of this protein in human skin in vivo, although dermal fibroblasts are also capable of expressing the gene.9 During the intracellular processing of the protein, three proα1(VII) chains associate and fold into a homotrimeric type VII collagen monomer. After secretion, type VII collagen molecules form antiparallel dimers with overlapping carboxy‐terminal ends, and this association is stabilised by intermolecular disulphide bonds (fig 1). During this process, part of NC2 is proteolytically removed. Subsequently, several type VII collagen dimer molecules laterally assemble into anchoring fibrils, which extend from the lower part of the dermo–epidermal basement membrane to the upper papillary dermis, thus providing critical integrity to the association of the epidermis with the underlying dermis. It has been postulated that the NC1 of type VII collagen at both ends of the anchoring fibrils bind to the basement membrane zone macromolecules, such as laminin 5 and type IV collagen, within the lamina densa and entrap the interstitial collagen fibres consisting primarily of type I, III and V collagens.10,11,12 Thus, the anchoring fibrils secure the association of the epidermal basement membrane with the underlying papillary dermis.

Figure 1 Synthesis of proα1(VII) collagen polypeptides and their assembly into anchoring fibrils under physiological conditions (left side of the figure) and perturbations in these processes leading to dystrophic forms of epidermolysis bullosa (right side). Within the intracellular (IC) space of keratinocytes and fibroblasts, proα1(VII) polypeptides are synthesised on ribosomes (I). Three polypeptides associate through their carboxy‐terminal ends and their collagenous domains wind into a characteristic triple helical conformation (II and III). After secretion into the extracellular (EC) space, triple helical type VII collagen molecules form antiparallel dimers (IV), and after proteolytic removal of a part of the carboxy‐terminal end, the dimer assembly is stabilised by intermolecular disulphide bonds (V). Subsequently, several dimer molecules laterally assemble in register to form cross‐striated, centro‐symmetric anchoring fibrils (VI). The amino‐terminal non‐collagenous terminal globular domains (NC1), consisting of non‐collagenous modules with homology to known adhesive proteins, attach to the extracellular macromolecules in the lamina densa, stabilising the association of the lamina densa with the underlying dermis. Mutations in the COL7A1 gene can result in premature termination codons (PTCs), manifesting with severe Hallopeau Siemens (HS)‐type recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (RDEB) when present in both alleles. Recessive missense mutations can interfere with chain association (a), triple helix formation (b) or stability of the triple helix (c), resulting in milder (mitis, M) non‐HS‐RDEB. Glycine substitutions in the collagenous domain destabilise the triple helix and can result through dominant‐negative interference, in dominantly inherited DEB (DDEB).

The Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa Research Association of America (DebRA) Molecular Diagnostics Laboratory was established in 1996 in the Department of Dermatology and Cutaneous Biology, Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA, with partial support from the patient advocacy organisation, DebRA. So far, the laboratory has analysed over 1000 families with different forms of epidermolysis bullosa for mutations in the candidate genes. We have previously reported our findings on the junctional and hemidesmosomal forms of epidermolysis bullosa.13 The cohort reported in this study includes 332 families with DEB, and we summarise our results of mutation analysis on COL7A1 in these patients, with phenotype–genotype correlations and implications for prognostication, genetic counselling and prenatal diagnosis in families at risk for recurrence.

Patients and methods

Patients

DNA samples from patients with DEB and their unaffected relatives were submitted to the DebRA Molecular Diagnostics Laboratory, after diagnosis and preliminary determination of the epidermolysis bullosa subtype by a clinical assessment and skin biopsy using transmission electron microscopy or immunoepitope mapping when available. Informed consent was obtained at outside referral centres, who then submitted blood or DNA samples of the people to be analysed. The experiments were approved by the Institutional Review Board at Thomas Jefferson University (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA), and they adhere to the Helsinki Guidelines.

Mutation detection

DNA was extracted from blood samples as described previously.14,15 Conditions and primers for generating polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products spanning all exons of the coding regions and flanking intronic sequences of COL7A1 have also been described previously.16 PCR products were earlier screened by conformation‐sensitive gel electrophoresis17,18 or, more recently, by denaturing high‐performance liquid chromatography (WAVE, Transgenomic, Gaithersburg, Maryland, USA). PCR products showing pattern shifts were sequenced in both directions in most cases using an ABI Prism 377 or ABI 3100 automated sequencer (Perkin‐Elmer‐Cetus, Foster City, California, USA). Putative mutations were confirmed by restriction enzyme digestion, followed by agarose gel electrophoresis. In cases where a restriction site was not altered by the mutation, a mismatch primer was used, which, in combination with the mutation, altered a restriction site. In some cases, allele‐specific oligonucleotide hybridisation analysis with mutation‐specific and wild‐type oligonucleotide probes was performed, as described previously.19 For most non‐glycine missense mutations, 100 control alleles were studied to rule out the possibility that the putative mutation might be a frequent polymorphism.

PCR was performed using Qiagen Taq polymerase and Q buffer (Qiagen, Valencia, California, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The PCRs contained 200 ng DNA as template and 100 ng of each primer in a final volume of 50 μl. Cycling conditions for all primer pairs were 94°C for 5 min, followed by 41 cycles of 94°C for 1 min; annealing temperature for a particular primer pair (range 55–60°C) for 1 min; 72°C for 1 min; and finally 72°C for 5 min.

The GenBank reference sequence for the COL7A1 gene used in this study is NM006846.1. The numbering of the mutant and wild‐type sequences follows this reference sequence. In cases where a base pair was deleted in a repeating sequence of a particular nucleotide (such as CCCC), the numbering of the mutation was chosen such that the base pair deleted corresponded to the position of the last nucleotide in the repeating sequence.

Analysis of the splice‐junction mutations

Mutations affecting the sequences at the intron–exon borders were analysed using Splice‐Site Prediction by Neural Network (http://www.fruitfly.org/seq_tools/splice.html).20 Genetic lesions were considered splice junction mutations if they were located either in the exon within 3 bp of the wild‐type splice site (donor −3 or acceptor +3) or in the intron within the region 2 bp upstream (acceptor −2) and 5 bp downstream (donor +5) of the wild‐type splice site. The wild‐type and mutant sequences were analysed through the splice‐site predictor, and a splice‐site score was generated for each sequence. The estimated accuracy of prediction was set to allow a false‐positive rate of 5.2% (93.2% of sites recognised) for 5′ splice sites and 4.8% (90.2% of sites recognised) for 3′ splice sites, for all splice junction mutations except two (table 2). The output from the splice‐site predictor indicated the consequence of the mutant sequence as follows: (a) no change in splice‐site score, (b) decrease in splice‐site score or (c) loss of splice site. This computational tool also analysed the intronic sequence surrounding the putative splice junction mutation and indicated whether a new cryptic splice site was formed by the mutant sequence and the score associated with this new splice site.

Table 2 Splice‐site mutations discovered in this study and their consequences, as predicted by the splice‐site predictor.

| Location | cDNA position | Splice‐site score | Theoretical predictions at mRNA protein level | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Mutant | ||||

| Putative splice‐site mutations found in patients with dominant inheritance pattern | |||||

| Intron 35 | 4120−1 G→C | 0.94 | LAS | Skip ex 36→IF | |

| Exon 48 (acceptor+1) | 4669G→C (G1557R) | 0.88 | 0.45 | a. NC | |

| b. Skip ex 48→IF | |||||

| Intron 69 | 5772+1 G→T | 0.96 | LDS | Skip ex 69→IF | |

| Exon 83 (acceptor+1) | 6619G→C (G2207R) | 0.95 | 0.69 | a. NC | |

| b. Skip ex 83→IF | |||||

| Intron 87 | 6900+1 G→T | 0.13* | LDS | Skip ex 87→IF | |

| Intron 87 | 6900+4 A→G | 0.13* | LDS | Skip ex 87→IF | |

| Exon 108 (donor−2) | 8045A→G (K2682R) | 0.91 | LDS | Skip ex 108→IF | |

| Putative splice‐site mutations found in patients with recessive inheritance pattern | |||||

| Exon 3 (donor−2) | 425A→G (K142R) | 0.84 | LDS | Skip ex 3→OF, PTC in ex 4 | |

| Intron 3 | 427−3 C→G | 0.83 | LAS | Skip ex 4→OF, PTC in ex 5 | |

| Intron 4 | 521−2 A→C | 0.52 | LAS | Skip ex 5→IF | |

| Intron 5 | 682+1 G→C | 0.90 | LDS | Skip ex 5→IF | |

| Intron 6 | 847−1 G→C | 0.34 | LAS | Skip ex 7→OF, PTC in ex 8 | |

| Intron 11 | 1507+1 G→C | 0.96 | LDS | Skip ex 11→IF | |

| Intron 12 | 1637−1 G→A | 0.97 | LAS | Novel CAS (0.90) 1 bp DS→OF, PTC in ex 14 | |

| Intron 20 | 2710+2 T→C | 0.62 | LDS | Skip ex 20→IF | |

| Intron 21 | 2858−1 G→A | 0.97 | LAS | a. Activation of CAS (score 0.97) 40 bp US→PTC in int 21 | |

| b. Novel CAS (score 0.69) 2 bp DS→OF, PTC in ex 22 | |||||

| c. Skip ex 22→IF | |||||

| Exon 31 (acceptor+1) | 3832del2 | 0.98 | 0.98 | PTC in ex 35 | |

| Exon 33 (donor−1) | 4011G→A | 0.99 | 0.58 | a. NC | |

| b. Skip ex 33→IF | |||||

| Intron 34 | 4048−1 G→A | 0.98 | LAS | a. Novel CAS (score 0.25) 101 bp US→OF, PTC in int 34 | |

| b. Novel CAS (score 0.20) 1 bp DS→OF, PTC in ex 36 | |||||

| c. Skip ex 35→IF | |||||

| Intron 35 | 4119+1 G→C | 1.00 | LDS | a. Novel CDS (score 0.92) 11 bp DS→OF, PTC in ex 36 | |

| b. Skip ex 36→IF | |||||

| Intron 42 | 4482+1 G→A | 1.00 | LDS | Skip ex 42→IF | |

| Intron 51 | 4899+1 G→T | 0.91 | LDS | a. Novel CDS (score 0.97) 32 bp DS→OF, PTC in ex 57 | |

| b. Skip ex 51→IF | |||||

| Exon 54 (donor−1) | 5052insGAAA | 0.99 | 0.95 | PTC in ex 55 | |

| Exon 69 (donor−2) | 5771A→C (Q1924P) | 0.96 | 0.78 | a. NC | |

| b. Skip ex 69→IF | |||||

| Exon 70 (donor−2) | 5819delC | 0.92 | 0.79 | PTC in ex 73 | |

| Exon 70 (donor−2) | 5819C→T (P1940L) | 0.92 | 0.80 | a. NC | |

| b. Skip ex 70→IF | |||||

| Intron 74 | 6216+5 G→T | 0.83 | LDS | Skip ex 74→IF | |

| Exon 79 (donor−1) | 6501G→A | 0.99 | 0.91 | a. Activation of CDS (score 0.96) 245 bp DS in int 79→PTC in int 79 | |

| b. NC | |||||

| c. Skip ex 79→IF | |||||

| Intron 79 | 6501+1G→C | 0.99 | LDS | Skip ex 79→IF | |

| Intron 81 | 6573+1 G→C | 0.99 | LDS | a. Activation of CDS (score 0.94) 25 bp DS→OF, PTC in ex 87 | |

| b. Skip ex 81→IF | |||||

| Intron 82 | 6619−2 A→T | 0.95 | LAS | Skip ex 83→IF | |

| Exon 84 (acceptor+3) | 6654C→G | 0.98 | 0.98 | NC | |

| Intron 85 | 6751−2 A→G | 0.99 | LAS | Skip ex 86→IF | |

| Exon 86 (acceptor+1) | 6751del2 | 0.99 | 0.97 | PTC in ex 87 | |

| Exon 86 (acceptor+2) | 6752G→C (G2251A) | 0.99 | 0.99 | NC | |

| Exon 92 (acceptor+1) | 7069G→A (G2357S) | 0.96 | 0.93 | a. NC | |

| b. Skip ex 92→IF | |||||

| Intron 92 | 7104+5 G→A | 1.00 | 0.75 | a. NC | |

| b. Skip ex 92→IF | |||||

| Exon 95 (donor−1) | 7344G→A | 0.98 | LDS | a. Novel CDS (score 0.76) 7 bp US→OF, PTC in ex 97 | |

| b. Skip ex 95→IF | |||||

| Intron 98 | 7485+2 T→G | 0.90 | LAS | Skip ex 98→IF | |

| Intron 105 | 7875+1 G→C | 0.96 | LDS | Skip ex 105→IF | |

| Intron 106 | 7929+5 A→C | 0.91 | 0.87 | a. NC | |

| b. Skip ex 106→IF | |||||

| Intron 106 | 7929+11del16 | 0.91 | 0.91 | a. Novel CDS (score 0.96) 10 bp DS→OF, PTC in ex 108 | |

| b. Skip ex 106→IF | |||||

| Intron 106 | 7930−1 G→A | 0.44 | LAS | Skip ex 107→IF | |

| Intron 110 | 8227−1 G→C | 0.73 | LAS | Skip ex 111→IF | |

| Intron 113 | 8407+5 G→C | 0.96 | LDS | Skip ex 113→OF, PTC in ex 117 | |

| Intron 117 | 8819−1 G→C | 0.87 | LAS | Skip ex 118 | |

bp, base pair; CAS, cryptic acceptor splice site; CDS, cryptic donor splice site; DS, downstream; ex, exon; IF, in‐frame translation; int, intron; LAS, loss of acceptor splice site; LDS, loss of donor splice site; NC, no change to splice site; OF, out‐of‐frame translation; PTC, premature termination codon; US, upstream.

Consequences of these mutations have not been analysed at the mRNA level.

*Estimated accuracy of prediction was adjusted due to failure to recognise wild‐type splice site by the splice‐site predictor. Minimum score was changed to 0.05, allowing for 98.3% of sites to be recognised with an 11.1% false‐positive rate.

Data obtained from using the splice‐site predictor were used to predict potential consequences at the protein level. If a mutant sequence was predicted to result in loss of the wild‐type splice site, it was postulated that the downstream exon would be skipped, and the downstream sequence was analysed to determine whether translation would continue in frame or out of frame in each case. If the prediction resulted in a decreased splice‐site score, the surrounding intronic sequence was analysed for activated alternative splice sites or new cryptic splice sites.

Results

Identification of COL7A1 mutations in patients with DEB

The DebRA Molecular Diagnostics Laboratory has ascertained more than 1000 patients with different forms of epidermolysis bullosa. Data from 332 families in this group were submitted with the referral diagnosis of DEB, on the basis of clinical observations, evidence for sublamina densa blistering, negative or attenuated immunofluorescence for type VII collagen or ultrastructural abnormalities in the anchoring fibrils. After an initial review of the diagnostic information and available material, DNA of 310 patients was subjected to COL7A1 analysis using genomic DNA as a template for PCR. The mutation detection strategy consisted of amplification of all 118 exons and flanking intronic sequences, followed by heteroduplex scanning or direct automated sequencing of the amplicons. Among DNA of the 310 patients subjected to mutation analysis, mutations were found in one or both alleles in 243 (78.4%) patients. Despite extensive analysis, including complete sequencing of the coding regions and splice‐site junctions in selected patients, no COL7A1 mutation was found in 59 (19%) patients. Among these patients in whom no COL7A1 mutation was detected, the diagnosis of DEB was confirmed in 44 (74.6%) patients by characteristic transmission electron microscopy or immunofluorescence findings, whereas in 15 (25.4%) patients, the diagnosis was based only on clinical criteria. In these cases, the mutations could reside outside the coding regions within the regulatory elements of COL7A1, such as the promoter region which was not analysed in this study. In 8 (2.6%) families, no attempts were made to identify specific mutations in COL7A1, and DNA was used only for genetic linkage analysis. As DEB can be inherited either in an autosomal dominant or autosomal recessive fashion, mutations were anticipated either in one or two alleles, respectively. Collectively, COL7A1 mutations were found in 355 mutant alleles among the anticipated 438 (81.1%) mutant alleles. In all, 242 mutations were distinct, and among them, 138 were novel, previously unreported mutations; these novel mutations are described online at http://jmg.bmj.com/supplemental.

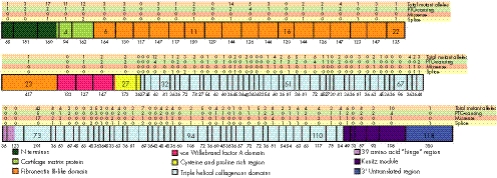

Figure 2 shows the distribution of the distinct mutations found along the type VII collagen gene with reference to the corresponding exons. Premature termination codon (PTC)‐causing and putative splice‐site mutations seem to be fairly evenly distributed among all the exons. By contrast, there was a definite concentration of missense mutations in the region of exons 73–75. This situation presents a potential mutation detection strategy in which these exons are analysed first in the case of families with DDEB.

Figure 2 Distribution of mutations along the type VII collagen gene (COL7A1). Schematic representation of COL7A1 with modular organisation (colour coded) and delineation of the corresponding exons drawn to scale. The sizes of the exons (bp) are shown under each exon and selected exons are numbered. The total number of mutant alleles in each exon is seen on the top line, and the numbers of distinct premature termination codon (PTC)‐causing, missense, and splice‐site mutations within each exon are shown above the type VII collagen structure. The clustering of mutations in exons 73–75 is evident.

Subclassification of patients with DEB by phenotype

As indicated above, the dystrophic forms of epidermolysis bullosa can be inherited either in an autosomal dominant or autosomal recessive fashion. Among the 310 families with DEB who were subjected to mutation analysis in this study, 48 (15.5%) were considered to be autosomal dominant on the basis of family constellation, detection of a previously published mutation associated with dominant families, or identification of a de novo mutation in one allele and confirmed by the absence of the mutant allele in both parents. The remaining 262 families were considered to be autosomal recessive on the basis of the absence of features considered characteristic for the autosomal dominant form. The patients with RDEB were subclassified on the basis of clinical features as follows.

Patients with Hallopeau Siemens recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (HS‐RDEB) were characterised by severe mutilating phenotype with extensive erosions and blistering since birth, pseudosyndactyly and joint contractures. This classification was supported by negative immunofluorescence for type VII collagen or absence of anchoring fibrils as determined by diagnostic transmission electron microscopy.

Patients with non‐HS‐RDEB were characterised by milder and more localised involvement and lack of mutilating pseudosyndactyly, with immunofluorescence for type VII collagen found to be often positive yet attenuated.

Patients were categorised as having unclassified RDEB when insufficient clinical information was available to make the distinction between HS‐RDEB and non‐HS‐RDEB.

In the cohort of 310 families, seven patients had phenotypic, genetic or mutational features of both dominant and recessive forms of DEB.

Mutations in the dominantly inherited forms of DEB

Among the 48 families classified as autosomal dominant DEB, mutations in one COL7A1 allele were found in all patients, and 43 of them (89.6%) were missense mutations, all but two being glycine substitution mutations in the Gly–X–Y repeat sequence in the collagenous domain of type VII collagen (table 3).

Table 3 Types of mutations identified in the type VII collagen gene in the subtypes of patients with dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa.

| DEB subtype | Patients, n (%) | Mutant alleles detected | Detection rate* | Types of mutations, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTC causing | Missense | Splice junction | |||||

| Glycine | Non‐glycine | ||||||

| HS‐RDEB | 74 (30.5) | 117 | 0.79 | 85 (72.6) | 6 (5.1) | 5 (4.3) | 21 (17.9) |

| Non‐HS‐RDEB | 92 (37.9) | 139 | 0.76 | 78 (56.1) | 28 (20.1) | 8 (5.8) | 25 (18.0) |

| Unclassified RDEB† | 22 (9.1) | 35 | 0.80 | 18 (51.4) | 9 (25.7) | 1 (2.9) | 7 (20.0) |

| Dominant DEB‡ | 48 (19.8) | 48 | 1.0 | 1 (2.1) | 41 (85.4) | 2 (4.2) | 4 (8.3) |

| Patients with dominant and recessive features§ | 7 (2.9) | 16 | 1.1 | 3 (18.8) | 6 (37.5) | 4 (25.0) | 3 (18.8) |

DEB, dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa; HS‐RDEB, Hallopeau‐Siemens recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa; PTC, premature termination codon.

*Detection rate is based on the expected two mutant alleles detected in recessive patients and one mutant allele in dominant ones. The value obtained in the subtype “Patients with dominant and recessive features” reflects the presence of three allelic mutations in some patients.

†Unclassified RDEB refers to patients in whom insufficient clinical information was available for accurate subclassification.

‡Patients with dominant DEB were presumed to be dominant on the basis of the family constellation and clinical presentation, presence of a mutation previously shown to be dominant or a de novo mutation confirmed by the absence of a mutant allele in both parents.

§These patients clinically exhibit features of both dominant and recessive subtypes. In each patient, at least two mutations were detected, with a total of three mutations detected in two patients.

One of the non‐glycine substitution missense mutations discovered consisted of replacement of a lysine by an arginine (K2682R); this mutation is in the last codon of exon 108 and potentially interferes with the splicing events around the corresponding exon–intron border. The other non‐glycine substitution replaces a valine with a methionine (V760M). In addition to missense mutations, one of the patients harboured a deletion mutation, 6864del16; this mutation has been described previously using alternate numbering (6862del16; GenBank accession number L02870) and has been analysed at the mRNA level.7,21 Four families harboured splice‐junction mutations; however, their consequences at the mRNA level have not been determined experimentally. Among the 48 families, nine mutations in COL7A1 arose de novo, apparently reflecting germline mosaicism in one of the parents. These de novo mutations were all glycine substitution mutations, eight of which resulted from a G→A transition.

Examination of the distribution of distinct mutations in the dominant DEB families showed definite clustering corresponding to exons 73–75 (fig 2). In particular, this area harboured 34 of the 41 (82.9%) dominant glycine substitution mutant alleles detected, attesting the critical role of glycine residues in every third position of collagen polypeptides to provide conformational stability to the collagen triple helix.

Mutations in patients with recessive DEB

Among the 243 families with DEB in whom mutations were found in COL7A1, 188 were classified as having RDEB; 74 of them had the Hallopeau‐Siemens (HS)‐RDEB type and 92 had the non‐Hallopeau‐Siemens (non‐HS‐RDEB) variant. In 22 patients, the available clinical information was not sufficient to make this distinction (unclassified RDEB). Mutation analysis of all patients with RDEB yielded 290 mutant alleles, which represents an overall detection rate of 74.4% (table 3). Among the HS‐RDEB mutations, 72.6% were PTC‐causing ones—that is, nonsense mutations or out‐of‐frame insertions or deletions. Eleven mutant alleles contained a missense mutation, either glycine (6 mutations; 5.1%) or non‐glycine (5 mutations; 4.3%) substitution mutations. In families with non‐HS‐RDEB, 78 (56.1%) mutations were PTC‐causing ones, 28 (20.1%) alleles were glycine substitution mutations and 8 (5.8%) alleles harboured a non‐glycine substitution mutation. In all three categories of RDEB, about 20% of the mutations affected a splice junction.

Among the 42 patients with HS‐RDEB who had mutations detected in both alleles, 27 (64.3%) patients harboured PTCs in both alleles. Of the 42 patients, 4 (9.5%) had a combination of a PTC and a missense mutation, whereas only 1 (2.4%) was a compound heterozygote for missense mutations. Of the 42 patients with HS‐RDEB, 12 patients in whom mutations were found in both alleles were homozygotes for the same mutation, reflecting either consanguinity in the family or the presence of a recurrent mutation.

In contrast with HS‐RDEB, 15 of 44 (34.1%) patients with non‐HS‐RDEB in whom mutations were found in both alleles showed PTC mutations in both alleles. Only 1 (2.3%) patient was homozygous for a missense mutation, and 12 (27.3%) patients were compound heterozygotes for a PTC and a missense mutation.

Patients with both dominant and recessive mutations

An interesting subset of seven patients harbouring COL7A1 mutations on both alleles was identified on the basis of unusual intrafamilial phenotypic heterogeneity explained by the presence of both dominant and recessive mutations in the same patient. Two of these families had a history of mild blistering, in addition to a child who presented with unexpectedly severe blistering.

The first patient was from a family in which the father was mildly affected, but the child had more generalised skin blistering, deafness, milia, scarring, pigment changes, abnormal nails, oral blisters, pseudosyndactyly and webbing. Skin biopsy was inconclusive, suggesting changes consistent with epidermolysis bullosa simplex (EBS) and DEB. A glycine substitution was found first, G2028R, which was present in paternal DNA and had not been described previously at the time of study. Subsequently, a recessive PTC‐causing mutation on the second allele, 1661del57, was found in the child and the unaffected mother, thus explaining the relatively severe disease presentation in the child.

A similar patient was from a highly consanguineous family with a pedigree suggestive of autosomal dominant inheritance; however, the child referred for mutation analysis showed severe manifestations of the disease, including more generalised skin involvement, milia, scars, skin atrophy, albopapuloid lesions, abnormal nails, oral erosions and blisters, caries, anaemia, growth retardation and webbing of the toes. Skin biopsy in this patient showed splitting of the sublamina densa and reduced anchoring fibrils. Exons 83 and 113 were flagged on heteroduplex scanning, and two mutations were discovered, R2791W (which had previously been reported in the literature as an autosomal dominant mutation22) and G2210V, a recessively inherited glycine substitution.

Other patients showed initial symptoms suggestive of an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern; however, on heteroduplex scanning, a combination of one known dominant mutation and a second recessively inherited mutation was discovered. The first affected person had severe, mutilating disease with a severe congenital skin defect resulting in scarring and decreased growth of the big toe. Examination by electron microscopy of the skin biopsy specimen showed reduced and hypoplastic anchoring fibrils, and immunofluorescence showed reduced COL7A1 labelling. On mutation analysis of the affected child, two mutations, G2351R (seen in another patient with an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern) and 5103delCCinsG, were detected, and further inquiry showed that the mother, who was a heterozygous carrier of the G2351R mutation, had symptoms as well, confirming an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern by pedigree.

Another patient was assumed to have recessive inheritance at the time of referral; the patient had blisters on the hands, knees, elbows and feet, as well as anal and oral blisters at birth. At the time of mutation analysis, symptoms had progressed and blistering continued on hands, feet, knees and elbows, with skin atrophy and nail dystrophy. Two exons, 105 and 113, were flagged on heteroduplex scanning, and subsequent analysis identified two mutations, 7875+1 G→C and R2791W (a known dominant mutation described previously in the literature).22

A third patient presented with what was thought to be recessively inherited disease, and two mutations were found: G2028W and 8697del11. Subsequent inquiry disclosed a history of blistering in family members on the maternal side of the family; as the G2028W mutation was found in the mother, it was presumed that this mutation was the dominantly inherited glycine substitution responsible for the disease manifestations in this family.

Two other families were initially thought to have dominant inheritance by pedigree, but were later found to harbour more than one mutation on heteroduplex scanning. Interestingly, three mutations were found in each family. One family had the known R2791W dominant mutation on one allele; the other allele contained two splice‐junction mutations, 6900+4 A→G and 7929+5 A→G. The other family had the G2028R mutation, which had been shown in another patient in this study to exhibit dominant inheritance on the paternal allele; the maternal allele contained two recessive missense mutations, G1580L and P2438L.

Recurrent mutations in COL7A1

Examination of the mutation database developed in this study disclosed a total of 11 distinct mutations that were present in at least four mutant alleles (>1%), each present in at least four unrelated people (table 4).23,24,25,26,27,28

Table 4 Recurrent mutations detected in the COL7A1 gene in this study.

| Mutation | Exon | Allelic frequency, n (%) | Reference, first author* |

|---|---|---|---|

| 425A→G | 3 | 14/355 (3.9) | Gardella23 |

| 497insA | 4 | 10/355 (2.8) | Christiano24 |

| 682+1 G→A | 5/6 | 5/355 (1.4) | Christiano25 |

| R578X | 13 | 12/355 (3.4) | Dunnill26 |

| 3840delC | 31 | 7/355 (2.0) | This study |

| 4919delG | 52 | 4/355 (1.1) | This study |

| G1907D | 68 | 4/355 (1.1) | This study |

| G2043R | 73 | 13/355 (3.7) | Christiano27 |

| G2575R | 103 | 4/355 (1.1) | Shimizu28 |

| R2814X | 115 | 6/355 (1.7) | Christiano25 |

| 8697del11 | 117 | 4/355 (1.1) | This study |

*Selected references of the first report or comprehensive review of this mutation.

Four of these mutations were previously undescribed, whereas the rest have been reported in the literature. These recurrent mutations in our cohort were not restricted to any particular ethnic background, although the mutation 425A→G was seen mainly in patients of European ancestry.

Several recurrent mutations, some specific to particular ethnic groups, have been reported in the literature. The splice‐site mutation, 425A→G, has been reported recurrently in Italian and central European populations and was also noted in our study.23,29,30 The glycine substitution, G2043R, has been reported recurrently in multiple ethnic groups of patients with DDEB.27,31

Other recurrent mutations have been reported to be exclusive to individual ethnic groups. In the British population, three recurrent PTC‐causing mutations have been described: R578X, 7786delG and R2814X.25,26,32,33,34 R578X and R2814X were also seen in our study, mainly in patients of European ancestry, although one Hispanic patient exhibited the R2814X mutation. Three mutations, 5818delC, 6573+1 G→C and E2857X, have been detected only in Japanese patients with RDEB; all were seen in our patients as well, with 5818delC and 6573+1 G→C detected in Japanese patients and E2857X found in one Korean family.28,35,36,37 Six mutations have been repeatedly detected in Italian patients; these include 7344G→A, 425A→G, 8441−14del21, 4783−1 G→A, 497insA and G1664A, the last three of which have been found only in Italian patients.22,23,24,29,32,38 In our study 7344G→A was found in one Italian and one Caucasian patient, 497insA was seen in patients of Italian and other European ancestry and 425A→G was seen frequently. In Mexican patients with DEB, the mutation 2470insG has been noted recurrently, with >50% of patients harbouring this mutation in a study of 36 people from 21 families; this finding was confirmed in our study by the discovery of the 2470insG mutation in two families of Mexican descent.39,40,41

Analysis of the splice‐junction mutations

A relatively large number, almost 17%, of all DEB mutations affected the sequences at the intron–exon borders; these mutations were spread across the COL7A1 gene, from exon 3 to intron 117 (fig 2). To examine the consequences of these mutations, 46 mutations, in which the genetic lesion was in the proximity of the intron–exon border, were analysed by a computational tool developed to predict cryptic splicing.20 Specifically, the programme was able to calculate a “splice‐site score” predicting the likelihood of the sequence to serve as a donor or acceptor site, in comparison with the wild‐type sequence. This information, together with the size of the individual exons, enabled us to predict whether the mutation potentially resulted in a downstream PTC.

Examination of the splice‐site mutations by this method showed that in 30 of 46 (65.2%) mutations, there was complete loss of either a donor or an acceptor splice site at the exon–intron border (table 2).

In five of these patients, the postulated skipping of the exon resulted in an out‐of‐frame deletion as the sole consequence, predicting a downstream PTC, whereas in 18 patients the putative exon skip was in frame. In 12 patients, the splice‐site score was reduced, suggesting either no consequence of the mutation in terms of splice‐site function or partial skipping of the exon. In several of these patients, the splice‐site predictor also identified cryptic splice sites down stream within the adjacent intron, suggesting that more complex splicing abnormalities may ensue as a result of these mutations. The consequences of these mutations at the mRNA or protein level were, however, not tested experimentally. Finally, in four cases (exons 31, 84, 86 and 106), there was no change in the splice‐site score as a result of the mutation. Thus, the consequences of these mutations in terms of splicing are not clear. One of these mutations resulted in an amino acid substitution (G2251A), which was probably responsible for the phenotype.

Discussion

The spectrum of COL7A1 mutations and genotype–phenotype correlations in DEB

DEB shows considerable phenotypic variability, and adding to the complexity of this disease is the fact that both autosomal dominant and autosomal recessive inheritance can be noted in different families. However, all mutations identified thus far in patients with DEB have been in COL7A1, with no evidence for mutations in other genes. It is conceivable, therefore, that the clinical and genetic heterogeneity can be explained, at least partly, by the types of mutations in COL7A1. Particularly, the consequences of the mutations at the mRNA and protein levels, when superimposed on the individual's genetic background and combined with environmental factors, will lead to the phenotypic spectrum noted in families with DEB.

The predominant mutation in the autosomal dominant variants of DEB is a missense mutation resulting in a glycine substitution within the triple helical domain of type VII collagen. Most of these mutations tend to cluster within exons 73–75 (fig 2), suggesting that the location of a glycine in every third position in this segment of type VII collagen is critical for the stability of the triple helix. As the proα1(VII) polypeptides harbouring these glycine substitution mutations are full length and contain NC2, these polypeptides are able to assemble into trimeric molecules with wild‐type polypeptides. Furthermore, these type VII collagen trimers can form antiparallel dimers with molecules consisting exclusively of wild‐type sequences. These dimer molecules then laterally assemble into anchoring fibrils, but as part of the molecule is abnormal, the entire anchoring fibril complex has compromised integrity as a consequence of dominant negative interference, and fragility of the skin ensues. However, as some anchoring fibrils, statistically estimated at 1.6% of all fibrils, contain only wild‐type sequences, and even those containing the missense mutations may be able to form morphologically altered anchoring fibrils visible by transmission electron microscropy, the phenotypic severity of DDEB is relatively mild.42 Notably, the mutation profile is similar within the two major subtypes of DDEB, the Pasini and Weber–Cockayne variants. As there is considerable clinical overlap within these two subtypes and they are allelic with similar types of mutations in COL7A1, the basis for distinguishing these variants as two separate entities is not clear.42

Glycine substitution mutations have been reported previously in clinically distinct subtypes of epidermolysis bullosa, including the pretibial variant, the pruriginosa type, Bart's syndrome, transient bullous dermolysis of the newborn (TBDN) and EBS superficialis.27,43,44,45,46,47,48,49 The reasons for the characteristic clinical presentations of these subtypes are not clear. Glycine substitution mutations in patients with Bart's syndrome and EBS superficialis are found in exon 73 of COL7A1, and the unusual phenotype of these variants cannot be explained by the position of the glycine substitution. By contrast, glycine substitution mutations in patients with DDEB pruriginosa have been reported in exons 61, 73, 85, 92, 93 and 110, whereas the one reported glycine substitution mutation in the pretibial variant is found in exon 105. It is not clear whether the positions of the glycine substitutions or the types of resulting amino acids (glutamic acid, serine, arginine, valine and cysteine) contribute to the clinical phenotype in these patients. It should be noted that, in addition to a glycine substitution, one proline substitution in exon 55 and two splice‐site mutations, at the intron 2–exon 3 and exon 115–intron 115 borders, have been detected in patients with the pretibial variant of DEB.29,50

Glycine substitutions at the same position but resulting in a different amino acid residue can also result in variable phenotypic expression.51 A glycine substitution at the amino acid position 2028 has been implicated in patients with both classic DDEB and DDEB pruriginosa. Specifically, G2028R has been detected in a Japanese family with DDEB pruriginosa and an American Caucasian family with toenail dystrophy without skin fragility. Conversely, the glycine substitution G2028A has been implicated in a family with classic DDEB, including blistering, milia, scarring plaques and nail dystrophy.51,52

A family with a history of autosomal dominant inheritance in three generations of dystrophic nails, without skin fragility or trauma‐induced blisters, and therefore initially without a firm diagnosis of epidermolysis bullosa, has been described; in the fourth generation, an infant manifested acral blistering and milia, in addition to nail changes. Mutation analysis revealed a glycine substitution mutation, G1776A, in exon 61 in the DNA of all affected family members, and no other pathogenic mutations were found despite screening of the rest of the COL7A1 gene. This confirms the association of the glycine substitution mutation with autosomal DDEB with variable manifestations.53 In this context, it should also be noted that some glycine substitution mutations are clearly recessive, in that the heterozygotic carriers do not have skin manifestations and the affected people have another allelic mutation, either homozygotic or compound heterozygotic in trans.

The characteristic mutation in the autosomal RDEB is a PTC, as a result of either a nonsense mutation or an insertion or deletion mutation leading to a frame shift of translation and a downstream PTC. These mutations are spread across the entire length of the coding sequence of COL7A1 (fig 2). Often, the PTCs are either homozygotic or compound heterozygotic with another PTC, essentially resulting in COL7A1 null alleles. However, PTCs can also be accompanied by a missense mutation in trans and, sometimes, patients can be compound heterozygotes for two missense mutations. The presence of a PTC in both alleles of COL7A1 manifests at the protein level by complete absence of anchoring fibrils, as visualised by transmission electron microscopy and by entirely negative immunofluorescence for type VII collagen epitopes. These findings are accompanied by extreme fragility of the skin, resulting in extensive scarring, joint contractures and severe mucous membrane involvement, as well as malnutrition, growth retardation and anaemia. These patients with HS‐RDEB also have the propensity for development of aggressively metastasising squamous‐cell carcinomas that can lead to patients' death as early as in their early 30s.54,55

A missense mutation in one or both alleles of COL7A1 usually signifies a milder phenotypic presentation, and in some patients the clinical presentation of RDEB is indistinguishable from that of DDEB. In fact, in such cases, examination by electron microscopy can reveal the presence of anchoring fibrils that may be morphologically altered or reduced in number, and the immunofluorescence can be positive, yet often attenuated. This constellation poses a diagnostic dilemma in situations where there is no family history of epidermolysis bullosa, and the patient has a relatively mild clinical presentation of DEB. Is it a de novo dominantly inherited DEB or a mild mitis, non‐HS‐RDEB?56 The answer to this dilemma is provided by DNA diagnostics; if only one glycine substitution mutation can be found in the affected person's DNA and neither parent is a carrier of the same mutation, the patient apparently has a de novo DDEB. By contrast, if two COL7A1 missense mutations are identified in the proband's DNA, the parents being heterozygotic carriers of the corresponding mutations, the mode of inheritance is presumably autosomal recessive. The distinction between the autosomal dominant and autosomal recessive mode of inheritance clearly has implications for accurate genetic counselling regarding the risk of an affected child to the same parents or to affected people in subsequent generations.

Consequences of splice‐junction mutations

An interesting finding in this study was the presence of a considerably large number (16.9%) of splice‐junction mutations in COL7A1, which were analysed by a predictive programme for the consequences of the mutations. The programme predicted, in most cases, a loss of acceptor or donor splice site, suggesting deletion of the corresponding exon or, in some cases, activation of a cryptic splice site. It should be noted that activation of cryptic splice sites (which are not necessarily intronic) can also occur when the mutated splice site is predicted to be lost. Conversely, a decreased splice‐site score could also lead to exon skipping. Nevertheless, in some cases the splice‐site score was unaltered, and the consequences of the mutations at the exon–intron junction are not clear.

In most cases, the consequences of the putative splicing mutations in our cohort were not analysed; however, a review of the literature showed that several splice‐site mutations, which were also found in this study, have been analysed by other laboratories. One example is a common recurrent mutation found at the exon 3–intron 3 border, 425A→G, which was expected to result in loss of the donor splice site at this location according to our analysis using the splice‐site predictor programme (table 2). This mutation was found to cause aberrant splicing and two abnormal mRNA transcripts were noted: one included intron 3 and the other excluded both exon 3 and intron 3. Both aberrant transcripts resulted in a PTC in exon 4, which confirms the outcome suggested by the splice‐site predictor in this case.57

Another mutation located at the exon 51–intron 51 border, 4899+1 G→T, was predicted to result in loss of donor splice site with two potential aberrant splicing outcomes: (a) activation of a novel strong cryptic donor splice site 32 bp down stream, resulting in out‐of‐frame transcription and PTC in exon 57; and (b) skipping of exon 51 and continued in‐frame transcription. Two different mRNA populations were discovered on analysis: (a) four of nine clones sequenced showed the use of a cryptic splice site 32 bp down stream from the mutation, leading to elongation of exon 51, which was then spliced to exon 52; and (b) five of the nine clones used the same cryptic splice site, but this time resulting in skipping of exon 52, with splicing of exon 51 to exon 53. Both outcomes resulted in out‐of‐frame translation and PTC in exon 57.58 These results show that, although the splice‐site predictor may correctly predict loss of splice site at a particular location, the ensuing consequences at the protein level can be complex and only analysis at the mRNA and/or protein level can fully elucidate the specific outcome.

A recurrent splice‐site mutation in the Japanese population, 6573+1 G→C at the exon 81–intron 81 border, was also detected in our study. The expected consequence, on the basis of the splice‐site prediction of loss of the normal donor splice site, was activation of a cryptic donor splice site 25 bp down stream of the original donor site, leading to out‐of‐frame translation and PTC in exon 87. Another postulated consequence of this mutation would result in in‐frame skipping of exon 81, as a result of loss of the original donor splice site. Analysis at the mRNA level in the literature shows an aberrant transcript that uses the downstream cryptic splice site.59 We postulated that the explanation for the preferred use of the cryptic donor splice site as opposed to the native donor splice site of exon 82 is due to the greater affinity associated with the cryptic splice site. However, the splice‐site score of 0.94 associated with the cryptic site does not differ markedly from the native donor splice‐site score of 0.93 for exon 82, suggesting that other factors, such as the surrounding nucleotide sequence motifs, contribute to the splicing pattern at the mRNA level.

Although splice junction mutations have been associated with both dominantly and recessively inherited forms of DEB, the subtype described as TBDN is particularly interesting. Characteristics of this variant of DEB include blistering, which manifests at birth or soon after, usually with marked improvement or even resolution in the first few months to years of life. A characteristic immunohistochemical finding is the intracellular accumulation of type VII collagen in the basal keratinocytes. Two reports have identified glycine substitutions as the causative mutations in patients with TBDN. One patient was compound heterozygotic for one recessive and one dominant glycine substitution; the recessive mutation, G1519D in exon 44, was silent in the heterozygotic state, whereas the dominant mutation, G2251E in exon 86, presented with nail dystrophy when present alone.47 The second report describes a family in whom TBDN was noted in three generations; all affected family members harboured a heterozygotic glycine substitution mutation, G1522E, in exon 45.48 A third report describes a splice‐site mutation in the last nucleotide of intron 35 (4120−1 G→C) as the causative dominantly inherited mutation in three generations of the same family; however, the consequences of this mutation at the mRNA level have not been elucidated.60 It has been postulated that some glycine substitution mutations interfere with the formation of the stable triple helix of type VII collagen, preventing their secretion into the extracellular space, and thus leading to the intracellular accumulation of type VII collagen.61

Surprising phenotypes

As indicated above, certain general genotype–phenotype correlations can be identified by examination of the mutation database, but in some occasions the phenotype can be surprising. As an example, there are reports of families with PTCs in both COL7A1 alleles, predicting a severe HS‐RDEB phenotype, yet the patients had relatively mild disease. In one of these cases, careful analysis of the consequences of these mutations at the mRNA level showed that the exons harbouring the PTCs were removed by alternative splicing.62 As many of the exons in COL7A1 are in frame, such splicing results in the synthesis of a slightly shortened polypeptide that contains intact NC1 and NC2. The presence of the latter sequences both in the amino and carboxy‐terminal ends of the polypeptides allows formation of somewhat shortened, yet partially functional, type VII collagen molecules, which are able to form antiparallel dimers and assemble into anchoring fibrils at the dermal–epidermal junction. At this point, it is not clear as to how large such a deletion can be while still allowing the formation of functional anchoring fibrils, but it is clear from our observations that small deletions can be tolerated.

In general, the severity of the blistering tendency and the extracutaneous findings tend to be similar among the affected members in multiplex families. Surprisingly, however, in seven instances, a person with an unusually severe phenotype compared with other affected family members with relatively mild DDEB was found. In these cases, the more severely affected person was often seen to have a second recessive mutation that apparently modified the phenotype and, together with the dominant missense mutation identified in the family, resulted in severe clinical presentation. One similar case reported in the literature describes mutation analysis undertaken in twins with severe DEB. Two mutations were found, a paternal deletion/insertion (5103delCCinsG) and a maternal glycine substitution (G2351R). Further history disclosed that the mother and maternal grandfather had history of toenail dystrophy and infrequent erosions that did not heal well, suggesting autosomal DDEB.63 Thus, the maternal glycine substitution mutation apparently causes DDEB with a mild phenotype. However, when combined with a paternal null allele, the glycine substitution will be reduced to hemizygosity, resulting in a much more severe phenotype. These observations could be interpreted to suggest that dominant glycine substitution mutations in the homozygotic state would result in a more severe clinical presentation than that caused by a dominant‐negative glycine substitution in only one allele. In our cohort, we encountered two homozygotic glycine substitution mutations (G2671V and G2695S), but these cases lacked clinical information and were considered unclassified RDEB. A recent publication has reported two additional cases with homozygotic mutations, G1616R and G1719R, both with the non‐HS‐RDEB phenotype.64

Unusual genetics

At least two unusual genetic situations can affect molecular diagnostics and genetic counselling of patients with DEB. First, several cases have been determined to be de novo DDEB. In these cases, the proband shows the presence of only one COL7A1 mutation, while the parents do not carry the corresponding mutation in their peripheral blood leucocytes. This situation can be explained by germline mosaicism in one of the parents; the risk for recurrence of pregnancy for another affected individual involving the same parents is dependent on the percentage of mutant versus wild‐type allele‐containing cells in the germline of the parent contributing the mutation. For genetic counselling, this risk has been estimated to be anywhere between 2% and 5%, on the basis of clinical experience in patients with DEB and general observations in other heritable diseases.65 Although the risk for recurrence is considered to be relatively small, a patient with recurrent DDEB in a family with germline mosaicism has been reported.66

A second unusual genetic situation is presented by uniparental isodisomy in a patient with RDEB. Specifically, a recent report described a patient with HS‐RDEB who was homozygotic for a novel frameshift mutation, 345insG, in exon 3 of COL7A1.67 However, sequencing of parental DNA showed that although the patient's mother was a heterozygotic carrier of this mutation, the father's DNA contained only the wild‐type sequence. Microsatellite analysis confirmed paternity, and genotyping of the entire chromosome 3 by microsatellite markers showed that the affected child was homozygotic for every marker tested, which originated from a single maternal allele in chromosome 3. Thus, the HS‐RDEB in this patient is possibly due to complete maternal isodisomy of chromosome 3, resulting in reduction to homozygosity of the mutant COL7A1 gene locus. The severity of the HS‐RDEB in this patient was similar to that in other affected patients, and no other phenotypic abnormalities were observed, suggesting the absence of maternally imprinted genes on chromosome 3. Uniparental isodisomy has been previously shown in three patients with junctional epidermolysis bullosa, affecting LAMB3 and LAMC2 loci, both on chromosome 1.68,69,70

Clinical implications of mutation analysis in DEB

The information derived from mutation analysis in DEB has translational implications in terms of subclassification of DEB, accurate genetic counselling and determination of the risk of recurrence of the disease in some families. Identification of specific mutations in DEB also facilitates DNA‐based prenatal testing and preimplantation genetic diagnosis.71,25 These issues are discussed in detail in a subsequent article in this series on the molecular genetics of epidermolysis bullosa.

Electronic database information

OMIM numbers of diseases discussed in this study are as follows. Dominant dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa: 131750, 131800; recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa: 226600; pretibial epidermolysis bullosa: 131850; epidermolysis bullosa pruriginosa: 604129; Bart's syndrome: 132000; transient bullous dermolysis of the newborn: 131705; epidermolysis bullosa simplex superficialis: 607600.

Acknowledgements

Carol Kelly and Nanita Barchi assisted in manuscript preparation. We thank the following people who contributed to the studies on DEB: A Christiano, J McGrath, L Pulkkinen, A Hovnanian, D Woodley, R Knowlton, D Greenspan, ML Chu, R Burgeson, M Ryynänen, J Ryynänen, J‐C Lapiére, S Sollberg, A Fertala, R Eady, H Shimizu, D Sawamura, K Tamai, J Mellerio, B Bart, E Epstein, L Bruckner‐Tuderman, I Anton‐Lamprecht and S Amano. Advice from Drs Eugene Bauer, Jo‐David Fine and Alan Moshell has been most helpful.

Abbreviations

COL7A1 - type VII collagen gene

DEB - dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa

DDEB - dominant dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa

DebRA - Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa Research Association

EBS - epidermolysis bullosa simplex

HS‐RDEB - Hallopeau Siemens recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa

NC1 - non‐collagenous amino‐terminal globular domain

NC2 - carboxy‐terminal globular domain

non‐HS‐RDEB - non‐Hallopeau Siemens recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa

PCR - polymerase chain reaction

PTC - premature termination codon

RDEB - recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa

TBDN - transient bullous dermolysis of the newborn

Footnotes

Funding: This study was financially supported by the DebRA of America and by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, National Institutes of Health Grant P01 AR38923.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Fine J ‐ D, Eady R A J, Bauer E A, Briggaman R A, Bruckner‐Tuderman L, Christiano A, Heagerty A, Hintner H, Jonkman M F, McGrath J, McGuire J, Moshell A, Shimizu H, Tadini G, Uitto J. Revised classification system for inherited epidermolysis bullosa: report of the second international consensus meeting on diagnosis and classification of epidermolysis bullosa. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000421051–1066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uitto J, Richard G. Progress in epidermolysis bullosa: from eponyms to molecular genetic classification. Clin Dermatol 20052333–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anton‐Lamprecht I, Gedde‐Dahl T. Epidermolysis bullosa. In: Rimoin DL, Connor JM, Pyeritz RE, Korf BR, eds. Principles and practice of medical genetics. 4th edn. London: Churchill Livingstone, 20023810–3897.

- 4.Fine J ‐ D, Bauer E A, McGuire J, Moshell A.Epidermolysis bullosa: clinical, epidemiologic, and laboratory advances and the findings of the National Epidermolysis Bullosa Registry. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

- 5.Hovnanian A, Rochat A, Bodemer C, Petit E, Rivers CA, Prost C, Fraitag S, Christiano AM, Uitto J, Lathrop M, Barrandon Y, de Prost Y Characterization of 18 new mutations in COL7A1 in recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa provides evidence for distinct molecular mechanisms underlying defective anchoring fibril formation. Am J Hum Genet 199761599–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christiano A M, Hoffman G G, Chung‐Honet L C, Lee S, Cheng W, Uitto J, Greenspan DS Structural organization of the human type VII collagen gene (COL7A1), comprised of more exons than any previously characterized gene. Genomics 199421169–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christiano A M, Greenspan D S, Lee S, Uitto J. Cloning of human type VII collagen: complete primary sequence of the α1(VII) chain and identification of intragenic polymorphisms. J Biol Chem 199426920256–20262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christiano A M, Rosenbaum L M, Chung‐Honet L C, Parente M G, Woodley D T, Pan T C, Zhang R Z, Chu M L, Burgeson R E, Uitto J. The large non‐collagenous domain (NC‐1) of type VII collagen is amino‐terminal and chimeric: homology to cartilage matrix protein, the type III domains of fibronectin and the A domains of von Willebrand factor. Hum Mol Genet 19921475–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ryynanen J, Sollberg S, Olsen D R, Uitto J. Transforming growth factor‐β up‐regulates type VII collagen gene expression in normal and transformed epidermal keratinocytes in culture. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1991180673–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brittingham R, Uitto J, Fertala A. High‐affinity binding of the NC1 domain of collagen VII to laminin 5 and collagen IV. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 20063433692–3699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen M, Marinkovich M P, Veis A, Cai X, Rao C N, O'Toole E A, Woodley D T. Interactions of the amino‐terminal noncollagenous (NC1) domain of type VII collagen with extracellular matrix components. A potential role in epidermal‐dermal adherence in human skin. J Biol Chem 199727214516–14522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shimizu H, Ishiko A, Masunaga T, Kurihara Y, Sata M, Bruckner‐Tuderman L, Nishikawa T. Most anchoring fibrils in human skin originate and terminate in the lamina densa. Lab Invest 199776753–763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Varki R, Sadowski S, Pfendner E, Uitto J. Epidermolysis bullosa. I. Molecular genetics of the junctional and hemidesmosomal variants. J Med Genet 200643641–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakano A, Pfendner E, Hashimoto I, Uitto J. Herlitz junctional epidermolysis bullosa: novel and recurrent mutations in the LAMB3 gene and the population carrier frequency. J Invest Dermatol 2000115493–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T.Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 19899.16–9.19.

- 16.Christiano A M, Hoffman G G, Zhang X, Xu Y, Tamai Y, Greenspan D S, Uitto J. Strategy for the identification of sequence variants in COL7A1, and novel 2 bp deletion mutation in recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Hum Mut 199710408–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ganguly A, Rock M J, Prockop D J. Conformation ‐sensitive gel electrophoresis for rapid detection of single‐base differences in double‐stranded PCR products and DNA fragments: evidence for solvent‐induced bends in DNA heteroduplexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 19939010325–10329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Körkkö J, Annunen S, Pihlajamaa T, Prockop D J, Ala‐Kokko L. Conformation sensitive gel electrophoresis for simple and accurate detection of mutations: comparison with denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis and nucleotide sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998171681–1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Christiano A M, Amano S, Eichenfield L F, Burgeson R E, Uitto J. Premature termination codon mutations in the type VII collagen gene in recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa result in nonsense‐mediated mRNA decay and absence of functional protein. J Invest Dermatol 1997109390–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wessagowit V, Kim S C, Oh S W, McGrath J A. Genotype‐phenotype correlation in recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa: when missense doesn't make sense. J Invest Dermatol 2005124863–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cserhalmi‐Friedman P B, McGrath J A, Mellerio J E, Romero R, Salas‐Alanis J C, Paller A S, Dietz H C, Christiano A M. Restoration of open reading frame resulting from skipping of an exon with an internal deletion in the COL7A1 gene. Lab Invest 1998781483–1492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whittock N V, Ashton G H S, Mohammedi R, Mellerio J E, Mathew C G, Abbs S J, Eady R A J, McGrath J. Comparative mutation detection screening of the type VII collagen gene (COL7A1) using the protein truncation fluorescent chemical cleavage of mismatch, and conformation sensitive gel electrophoresis. J Invest Dermatol 1999113673–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gardella R, Belletti L, Zoppi N, Marini D, Barlati S, Colombi M. Identification of two splicing mutations in the collagen type VII gene (COL7A1) of a patient affected by the localized variant of recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Am J Hum Genet 199659292–300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Christiano A M, D'Alessio M, Paradisi M, Angelo C, Mazzanti C, Puddu P, Uitto J A common insertion mutation in COL7A1 in two Italian families with recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. J Invest Dermatol 1996106679–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Christiano A M, LaForgia S, Paller A S, McGuire J, Shimizu H, Uitto J. Prenatal diagnosis for recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa in ten families by mutation and haplotype analysis in the type VII collagen gene (COL7A1). Mol Med 1996259–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dunnill M G S, Richards A J, Milana G, Mollica F, Eady R A J, Pope F M. A novel homozygous point mutation in the collagen VII gene (COL7A1) in two cousins with recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Hum Mol Genet 199431693–1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Christiano A M, Lee J Y ‐ Y, Chen W J, LaForgia S, Uitto J. Pretibial epidermolysis bullosa: genetic linkage to COL7A1 and identification of a glycine‐to‐cysteine substitution in the triple‐helical domain of type VII collagen. Hum Mol Genet 199541579–1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shimizu H, McGrath J A, Christiano A M, Nishikawa T, Uitto J. Molecular basis of recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa: genotype/phenotype correlation in a case of moderate clinical severity. J Invest Dermatol 1996106119–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gardella R, Castiglia D, Posteraro P, Bernardini S, Zoppi N, Paradisi M, Tadini G, Barlati S, McGrath J A, Zambruno G, Colombi M. Genotype‐phenotype correlation in Italian patients with dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. J Invest Dermatol 20021191456–1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Csikós M, Szöcs H I, Lászik A, Mecklenbeck S, Horváth A, Kárpáti S, Bruckner‐Tuderman L. High frequency of the 425 A→G splice‐site mutation and novel mutations of the COL7A1 gene in central Europe: significance for future mutation detection strategies in dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Br J Dermatol 2005152879–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mellerio J E, Salas‐Alanis J C, Talamantes M L, Horn H, Tidman M J, Ashton G H S, Eady R A J, McGrath J A. A recurrent glycine substitution mutation, G2043R, in the type VII collagen gene (COL 7A1) in dominant dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Br J Dermatol 1998139730–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dunnill M G S, McGrath J A, Richards A J, Christiano A M, Uitto J, Pope F M, Eady R A. Clinicopathological correlations of compound heterozygous COL7A1 mutations in recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. J Invest Dermatol 1996107171–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mellerio J E, Dunnill M G, Allison W, Ashton G H, Christiano A M, Uitto J, Eady R A, McGrath J A. Recurrent mutations in the type VII collagen gene (COL7A1) in patients with recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. J Invest Dermatol 1997109246–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mohammedi R, Mellerio J E, Ashton G H, Eady R A J, McGrath J A. A recurrent COL7A1 mutation, R2814X, in British patients with recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Clin Exp Dermatol 19992437–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Christiano A M, Suga Y, Greenspan D S, Ogawa H, Uitto J. Premature termination codons on both alleles of the type VII collagen gene (COL7A1) in three brothers with recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. J Clin Invest 1995951328–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tamai K, Ishida‐Yamamoto A, Matsuo S, Iizuka H, Hashimoto I, Christiano AM, Uitto J, McGrath JA Compound heterozygosity for a nonsense mutation and a splice site mutation in the type VII collagen gene (COL7A1) in recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Lab Invest 199776209–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tamai K, Murai T, Mayama M, Kon A, Nomura K, Sawamura D, Hanada K, Hashimoto I, Shimizu H, Masunaga T, Nishikawa T, Mitsuhashi Y, Ishida‐Yamamoto A, Ikeda S, Ogawa H, McGrath J A, Pulkkinen L, Uitto J. Recurrent COL7A1 mutations in Japanese patients with dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa: positional effects of premature termination codon mutations on clinical severity. J Invest Dermatol 1999112991–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ashton G H S, Mellerio J E, Dunnill M G S, Milana G, Mayou B J, Carrea J, McGrath J, Eady R AJ. Recurrent molecular abnormalities in type VII collagen in southern Italian patients with recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Clin Exp Dermatol 199924232–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Christiano A M, Anton‐Lamprecht I, Amano S, Ebschner U, Burgeson R E, Uitto J. Compound heterozygosity for COL7A1 mutations in twins with dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa: a recessive paternal deletion/insertion mutation and a dominant negative maternal glycine substitution result in a severe phenotype. Am J Hum Genet 199658682–693. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mellerio J E, Salas‐Alanis J C, Amaya‐Guerra M, Tamez E, Ashton G H S, Mohammedi R, Eady R A J, McGrath J A. A recurrent frameshift mutation in exon 19 of the type VII collagen gene (COL7A1) in Mexican patients with recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Exp Dermatol 1999822–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Salas‐Alanis J C, Amaya‐Guerra M, McGrath J A. The molecular basis of dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa in Mexico. Int J Dermatol 200039436–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kon A, Nomura K, Pulkkinen L, Sawamura D, Hashimoto I, Uitto J. Novel glycine substitution mutations in COL7A1 reveal that the Pasini and Cockayne‐Touraine variants of dominant dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa are allelic. J Invest Dermatol 1997109684–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee J Y Y, Pulkkinen L, Liu H S, Chen Y F, Uitto J. A glycine‐to‐arginine substitution in the triple‐helical domain of type VII collagen in a family with dominant dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa pruriginosa. J Invest Dermatol 1997108947–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chuang G S, Martinez‐Mir A, Yu H S, Sung F Y, Chuang R Y, Cserhalmi‐Friedman P B, Christiano A M. A novel missense mutation in the COL7A1 gene underlies epidermolysis bullosa pruriginosa. Clin Exp Dermatol 200429304–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mellerio J E, Ashton G H S, Mohammedi R, Lyon C C, Kirby B, Harman K E, Salas‐Alanis J C, Atherton D J, Harrison P V, Griffiths W A D, Black M M, Eady R A J, McGrath J A. Allelic heterogeneity of dominant and recessive COL7A1 mutations underlying epidermolysis bullosa pruriginosa. J Invest Dermatol 1999112984–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Christiano A M, Bart B J, Epstein E H, Uitto J. Genetic basis of Bart's syndrome: a glycine substitution in the type VII collagen gene. J Invest Dermatol 1996106778–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hammami‐Hauasli N, Raghunath M, Kuster W, Bruckner‐Tuderman L. Transient bullous dermolysis of the newborn associated with compound heterozygosity for recessive and dominant COL7A1 mutations. J Invest Dermatol 19981111214–1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fassihi H, Diba V C, Wessagowit V, Dopping‐Hepenstal P J, Jones C A, Burrows N P, McGrath J A. Transient bullous dermolysis of the newborn in three generations. Br J Dermatol 20051531058–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Martinez‐Mir A, Liu J, Gordon D, Weiner MS, Ahmad W, Fine J D, Ott J, Gilliam T C, Christiano A M. EB simplex superficialis resulting from a mutation in the type VII collagen gene. J Invest Dermatol 2002118547–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Betts C M, Posteraro P, Costa A M, Varotti C, Schubert M, Bruckner‐Tuderman L, Castiglia D. Pretibial dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa: a recessively inherited COL7A1 splice site mutation affecting procollagen VII processing. Br J Dermatol 1999141833–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Murata T, Masunaga T. Shimizu H, Takizawa Y, Ishiko A, Hatta N, Nishikawa T. Glycine substitution mutations by different amino acids in the same codon of COL7A1 to heterogeneous clinical phenotypes of dominant dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Arch Dermatol Res 2000292477–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nakamura H, Sawamura D, Goto M, Sato‐Matsumura K C, LaDuca J, Lee J Y Y, Masunaga T, Shimizu H. The G2028R glycine substitution mutation in COL7A1 leads to marked inter‐familiar clinical heterogeneity in dominant dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. J Dermatol Sci 200434195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dharma B, Moss C, McGrath J A, Mellerio J E, Ilchyshyn A. Dominant dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa presenting as familial nail dystrophy. Clin Exp Dermatol 20012693–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McGrath J A, Schofield O M, Mayou B J, McKee P H, Eady R A. Epidermolysis bullosa complicated by squamous cell carcinoma: report of 10 cases. J Cutan Pathol 199219116–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Christiano A M, Crollick J, Pincus S, Uitto J. Squamous cell carcinoma in a family with dominant dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa: a molecular genetic study. Exp Dermatol 19998146–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]