Abstract

Background

Broken chromosomes must acquire new telomeric “caps” to be structurally stable. Chromosome healing can be mediated either by telomerase through neo‐telomere synthesis or by telomere capture.

Aim

To unravel the mechanism(s) generating complex chromosomal mosaicisms and healing broken chromosomes.

Methods

G banding, array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH), fluorescence in‐situ hybridisation (FISH) and short tandem repeat analysis (STR) was performed on a girl presenting with mental retardation, facial dysmorphism, urogenital malformations and limb anomalies carrying a complex chromosomal mosaicism.

Results & discussion

The karyotype showed a de novo chromosome rearrangement with two cell lines: one cell line with a deletion 9pter and one cell line carrying an inverted duplication 9p and a non‐reciprocal translocation 5pter fragment. aCGH, FISH and STR analysis enabled the deduction of the most likely sequence of events generating this complex mosaic. During embryogenesis, a double‐strand break occurred on the paternal chromosome 9. Following mitotic separation of both broken sister chromatids, one acquired a telomere vianeo‐telomere formation, while the other generated a dicentric chromosome which underwent breakage during anaphase, giving rise to the del inv dup(9) that was subsequently healed by chromosome 5 telomere capture.

Conclusion

Broken chromosomes can coincidently be rescued by both telomere capture and neo‐telomere synthesis.

Telomeres are specialised nucleoproteic complexes localised at the physical ends of linear eukaryotic chromosomes that maintain their stability and integrity.1 Telomere loss causes chromosome instability (through breakage or improper telomere maintenance) resulting in several types of chromosome rearrangements, including terminal deletions, inverted duplications, DNA amplification, duplicative and non‐reciprocal translocations and dicentric chromosomes, all of which have been associated with human diseases, cell senescence, and/or apoptotic cell death. Such chromosome aberrations can be prevented or terminated by the addition of telomeric repeats to the end of the broken chromosome.2 Telomerase, a specialised reverse transcriptase‐like enzyme, can stabilise chromosomal broken ends by the addition of telomeric sequences directly on to non‐telomeric DNA. Telomerase is activated in cancer cells and in germline cells and is still active in early stages of embryogenesis.3 Broken chromomsomes can acquire new telomeres by “telomere capture”, a process first described by Meltzer et al4 in cancer cells, transformed fibroblasts and lymphoblastoid cell lines. This process involves the addition of telomeres from normal chromosomes at the site of double‐strand breaks (DSBs) to stabilise broken chromosomes by non‐reciprocal translocation.4 Schematically, the broken end of a chromosome invades a region of homology and initiates replication, thereby duplicating the end of that chromosome.5 Particular chromosomal anomalies, such as mosaicism, can help to elucidate some aspects of chromosome healing and further increase our understanding of the mechanism of genomic disorders. Constitutional chromosomal mosaicism with two cell lines carrying two different rearranged sets of chromosomes is an extremely rare condition that is generally the result of a postfertilisation mitotic error.6,7 Polymorphic markers analysis has shown that, in addition, such mosaics may originate during parental meiosis.7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14

In this paper we describe a girl with a mosaic del(9)/der(9)t(5;9)inv dup(9) initially diagnosed by conventional high‐resolution G‐banded chromosomes and characterised by array comparative genomic hybridisation (aCGH) and fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH). The most straightforward explanation for our findings would be an early post‐zygotic error followed by independent chromosome healing of both sister chromatids by neo‐telomere formation and telomere capture.

Patient and methods

Clinical report

The patient (fig 1) was a newborn Spanish girl born of the first pregnancy of healthy and non‐consanguineous parents. Her father and mother were 19 and 16 years old, respectively. The pregnancy was complicated by oligohydramnios. The delivery was at term and eutocic. The birth weight was 2700 g and the clinical examination showed trigonocephaly and bilateral club feet.

Figure 1 (A, B) Clinical pictures of the patient. Parental informed consent was obtained for publication of this figure.

When she was 8 months old, clinical examination showed other dysmorphic features with upslanting palpebral fissures, depressed and broad nasal root, asymmetric implantation of the ears, bifid uvula, normal palate, plagiocephaly and prominent metopic suture. Cardiac examination revealed a heart murmur but no structural cardiac anomalies. Labia majora were hypoplastic. Cranial x ray was normal. Abdominal ultrasound showed a hypoplastic and ectopic right kidney and retrograde urography revealed a grade III vesiculoureteral reflux on the left kidney and a grade I vesiculoureteral reflux on the right. These refluxes had disappeared at the age of 3 years.The girl was able to sit unsupported at 9 months of age and walked alone at 18 months.

Physical examination at 6 years showed mild synophrys, hypoplastic alae nasi, long and smooth philtrum, thin upper lip, small and dysmorphic ears, pectus excavatum and campodactyly of the fifth fingers. She had a moderate psychomotor delay.

At 10 years she was not able to read. She had dental caries and an angioma appeared on the internal side of the left lower limb. Menarche was at normal age (13 years). At present, she is 14 years old with a height of 146 cm (P3–P10), weight of 55 kg (P75) and occipital‐frontal circumference of 52.5 cm (P3–P10).

Cytogenetic analysis

High‐resolution G‐banded chromosomes were prepared from peripheral blood lymphocytes according to standard procedures.

aCGH analysis

DNA of the parents and the child was extracted from peripheral leucocytes according to standard procedures. aCGH was performed as previously described.15,16 Briefly, for total genome coverage aCGH, arrays were constructed using a 1 Mb clone set that contained 3587 BAC and PAC clones spotted in double. Test and reference genomic DNAs were labelled by a random prime‐labelling system (Bioprime array CGH, Invitrogen, California, USA) using Cy3‐ and Cy5‐labelled dCTPs (Amersham Biosciences, New Jersey, USA). The results presented are a combination of two hybridisations in which the patient and a parent (mother and father's DNA labelling) were dye swapped in a loop design.

A chromosome 9 full tiling‐path array chip was constructed using 560 BAC and PAC clones from the 32K BAC clone library (CHORI BACPAC Resources, http://bacpac.chori.org/genomicRearrays.php) and 595 BAC clones from the 1 Mb clone set mapped to various human chromosomes as internal controls. Experiments were conducted and data analysed as for the 1 Mb aCGH.

FISH analysis

FISH was performed on metaphase and nuclei spreads according to standard procedures with probes labelled either by biotine‐16‐dUTP (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany)14 or by DOP‐PCR direct labelling with SpectrumOrange‐dUTP (Vysis, Abbott Molecular, Illinois, USA).15 For chromosome 5, the commercial probes Cytocell Aquarius LPU008 specific for the Cri‐du‐Chat chromosome region (CDCCR) and Cri‐du‐Chat Syndrome LSI D5S23, D5S71 SpectrumGreen (Vysis, Abbott Molecular) were used according to the respective manufacturers' protocols. The FITC‐(C3TA2)3 peptide nucleic acid telomeric probe was used for FISH experiments to detect telomeric repeats in cell spreads using the regular FISH protocol.

DNA polymorphism analysis

A set of microsatellite polymorphic marker (CA)n repeats spaced along chromosomes 5 and 9 was selected and amplified by PCR in 35 cycles using fluorescently labelled primers (a 6‐FAM 5′ label on the forward primers). Primer sequences and loci information are available from the Genome Database (http://www.gdb.org/gdb/) and the NCBI database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db = unists). The amplicons were sized by capillary electrophoresis on an ABI PRISM 3100 Genetic Analyzer. The size of the alleles and area of the peaks were calculated with GeneScan 3.1 and Genotyper 3.7 softwares. To assess whether duplication had occurred at any given locus, a quantitative analysis was performed. The area of each allelic peak (a measure of the amount of amplified material) and the ratio between the areas of the shorter and longer allele were calculated.

Bioinformatic breakpoint sequence analysis

Pairwise basic local alignment search tool (BLAST) searches using the genomic sequences (based on NCBI build 36.1) of regions spanning breakpoints on 5p13.3, 9p22.1 and 9p13.3 were performed using NCBI Blast 2 Sequences online platform (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/bl2seq/wblast2.cgi).17 To identify large stretches (>1 kb) of high sequence identity (>90%), such as that found in low‐copy repeats (LCRs), for each pairwise BLAST analysis the search parameters were adjusted as follows: the expect threshold was lowered to 5 to increase the stringency of the search; the word size was increased to 100 to search for longer stretches of homology; and the Filter option was selected to mask out low‐complexity and repetitive DNA sequences. Sequence homologies and searches for LCRs were performed on the above‐mentioned sequences using PipMaker online software (http://pipmaker.bx.psu.edu/cgi‐bin/pipmaker?basic). Possible homology regions detected by PipMaker were checked simultaneously by BLAT platform using the University of California Santacruz Human BLAT Search tool (http://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi‐bin/hgBlat) and BLAST using the NCBI BLAST software (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/).

Results

Cytogenetic analysis

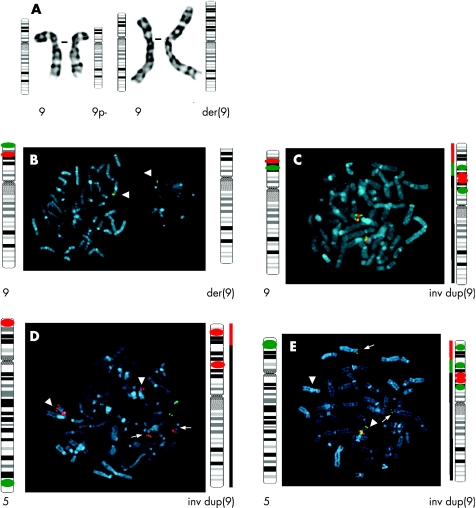

High‐resolution G banding showed the presence of two cell lines in the peripheral blood lymphocytes: 46,XX,del(9)(p22.1)[21]/46,XX,der(9)t(5;9)(p13.3;p22.1)[18] indicating the presence of monosomy 9p22.1 in all blood cells and trisomy 5p13.3 in half the blood cells (fig 2A). The chromosomes of the parents were normal.

Figure 2 Cytogenetic data. (A) Partial high‐resolution G‐banded karyotype showing the normal chromosome 9 and the del(9) on the left and a normal chromosome 9 and the der(9) on the right. Ideograms of the normal and derivative chromosomes 9 are shown. (B–E) Fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH) data with a schematic representation of the probe loci on the ideograms, as expected. (B) A del(9p) cell. The picture shows the probes tested for the 9p terminal deletion, with only one signal for both the probes on a metaphase and a nucleus (white arrow). (C) FISH showing the inv dup(9p). (D–E) FISH analysis displaying the organisation of the rearranged chromosomes in the der(9p) cell line with a schematic representation of the loci of the probes on ideograms of chromosomes 5 and der(9). The black line represents the region of the chromosome that belongs to 9, the red line the one belonging to chromosome 5p and the green line the inv dup segment of chromosome 9. The thick arrowheads indicate chromosome 9 and the thin ones indicate chromosome 5. (D) This plate shows the non‐reciprocal translocation of 5p on chromosome 9. (E) FISH using Cri‐du‐Chat Syndrome LSI D5S23, D5S71 SpectrumGreen showing that the dup(5p) is situated telomeric to the der(9p). The ideogram of the normal chromosome 9 with probes assigned on it, is the same as the one on the left of (C).

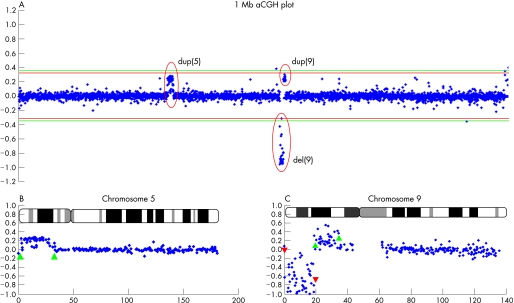

aCGH analysis

To characterise the rearranged regions, aCGH was performed on DNA from the patient and her parents (fig 3A–C). The hybridisation efficiency of the experiment was 94.68% with a standard deviation (SD) of 0.088. The 1 Mb resolution genome wide aCGH showed an approximately 18.5 Mb terminal deletion of chromosome 9p with interstitial duplication of chromosome 9p of approximately 16.5 Mb and a terminal duplication of chromosome 5p of about 28.8 Mb, extending to the region between the clones RP11‐46C20 and RP11‐37M16 (fig 3B). The chromosome 9 tiling‐path array enabled finemapping of the breakpoints on chromosome 9 (fig 3C). The deleted region was shown to span in between BACs RP11‐269B5 and RP11‐296P7. This also represents the distal breakpoint (the telomeric one) for the interstitial duplicated region, whereas the proximal one was flanked by BAC RP11‐284F1 and BAC RP11‐182L18. The average log2 of the intensity ratio values of the abnormal clones duplicated on chromosomes 5p and 9p were, respectively, 0.23 and 0.25. As the theoretical intensity ratio of a duplication is log2(3/2) = 0.58 (3 copies in odds 2 copies in a normal situation), the estimated degree of mosaicism would be 0.23/0.58 to 0.25/0.58 or 40–43%. These abnormalities were shown to be de novo, since arrays of the parents were normal (data not shown).

Figure 3 Array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) data. (A) Result of 1 Mb aCGH analysis of the patient. The y axis represents the log2 of the intensity ratios of the combined dye swap experiments of the patient/parental DNA in the loop design. In the x axis clones are ordered from the short‐arm telomere to the long‐arm telomere and chromosomes are ordered from 1 to 22. The green lines indicate the thresholds (4×SD) for clone deletion (−0.36) and duplication (+0.36). The aberrant clones are encircled in red. (B) Partial 1 Mb aCGH data from chromosome 5 of the child displaying log2 ratio plot with the mosaic duplicated region of 5p delineated by the green upward arrowheads. In the x axis the relative distance of the bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clones from the 5p telomere is indicated in Mb with the ideogram. (C) A full tiling path 32k aCGH of chromosome 9 of the patient displaying deletion (red downward arrowheads) and mosaic duplication (green upward arrowheads) and enabling the finemapping of breakpoints.

FISH analysis: organisation of rearranged chromosomes in both cell lines

To confirm the aCGH results and to determine how the deletion and duplications were organised in both cell lines, a series of BAC probes was hybridised on metaphase spreads of the patient's lymphocytes and investigated by FISH (fig 2B–E). In 96 of 100 nuclei and in 16 metaphases analysed, probes RP11‐48M17 and RP11‐503K16 spanning the deleted region on the 1 Mb array each showed only one signal—that is, all the cells had the del(9p) chromosome (fig 2B). As expected, probes RP11‐513M16 (SpectrumOrange labelled) and RP11‐48L13 (biotine labelled) localised at the duplicated region showed three signals in half of the studied nuclei (45 out of 100) (which is in accordance with array findings). On metaphases a green–red–green order of the probes was seen, suggesting an inverted duplication as shown in fig 2C. Besides, all the inv dup(9p) had the terminal deletion. To study the mosaicism for the duplicated 5p, metaphase spreads from the patient were hybridised with BAC RP11‐513M16 together with the commercial probe for the Cri‐du‐Chat Syndrome (CDCCR) LSI D5S23, D5S71 SpectrumGreen (fig 2D). Both chromosomes 5 were hybridised in all analysed metaphases whereas, in half of them, a red signal corresponding to the CDCCR‐specific probe hybridised on 9p, telomeric to the BAC RP11‐513M16, showing a non‐reciprocal translocation of the 5p on top of the 9p in half of the analysed cells (as calculated with the mean of the array intensity ratios). To characterise the cell line affected by this non‐reciprocal translocation, we carried out a FISH analysis with the commercial probe Cytocell Aquarius LPU008 (specific for the CDCCR in 5p) and both BACs RP11‐513M16 (SpectrumOrange labelled) and RP11‐48L13 (biotin labelled, fig 2E). As expected, we showed that the duplicated 5p was located telomeric to all the simultaneously del dup(9p) chromosome. FISH confirmed that the mosaic duplicated region of chromosome 5p extended to the BAC clone RP11‐53L13 on 5p13.3 (data not shown). In addition, peptide nucleic acid telomeric probe was hybridised to all chromosome ends (data not shown), showing the presence of telomeric sequences capping the ends of the broken chromosomes.

DNA polymorphism analysis: origin of rearrangements

To investigate the origin of the mosaicism and confirm the FISH analysis, polymorphic marker analysis was performed on DNA extracted from peripheral blood lymphocytes of the patient and her parents (table 1).

Table 1 Results of polymorphic marker analysis.

| Marker | Position (ISCN 2005) | Location (Mb, NCBI) | Genotypes/allele values | Parental origin | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Father | Proband | Mother | ||||

| D5S1981 | 5p15.33 | 1.2 | 257 | 257/263 | 263 | pat dup |

| D5S406 | 5p15.32 | 5 | 173 | 173 | 165/173 | NI |

| D5S630 | 5p15.31 | 9.6 | 238 | 238/244 | 244 | pat dup |

| D5S1991 | 5p15.2 | 15 | 223/229 | 223/225 | 225/229 | pat dup |

| D5S618 | 5q14.3 | 89 | 168/178 | 168/172 | 172 | |

| D5S671 | 5q34 | 163 | 201 | 201 | 201 | NI |

| D5S2073 | 5q35 | 195 | 240 | 240 | 240 | NI |

| D9S129 | 9p24.3 | 1.85 | 131 | 129 | 129 | pat del |

| D9S178 | 9p24.2 | 4 | 89 | 89 | 89 | NI |

| D9S269 | 9p23 | 11 | 168/174 | 168 | 168 | NI |

| D9S285 | 9p22.3 | 15 | 118/120 | 122 | 120/122 | pat del |

| D9S1846 | 9p21.3 | 21.6 | 182/188 | 182/186 | 186 | pat dup |

| D9S974 | 9p21.3 | 21.9 | 208/210 | 204/210 | 204 | pat dup |

| D9S942 | 9p21.3 | 21.9 | 112/118 | 102/112 | 102 | pat dup |

| D9S1748 | 9p21.3 | 21.9 | 106/116 | 110/116 | 110/112 | pat dup |

| D9S171 | 9p21.3 | 24.5 | 163/169 | 155/169 | 155/163 | pat dup |

| D9S165 | 9p13.3 | 33 | 210/212 | 212/216 | 210/216 | pat dup |

| D9S970 | 9p13.1 | 39 | 137/141 | 137/141 | 137 | pat dup |

| D9S197 | 9q22 | 66 | 200 | 200 | 200 | NI |

| D9S127 | 9q31 | 77 | 152/154 | 154/156 | 154/156 | |

| D9S1199 | 9q34 | 134.8 | 89/93 | 93/99 | 93/99 | |

| D9S1793 | 9q34 | 135.4 | 175/185 | 177/185 | 169/177 | |

| D9S66 | 9q34 | 135.7 | 119/129 | 119/129 | 119/129 | NI |

| D9S1818 | 9q34 | 136.3 | 154 | 148/154 | 148 | NI |

| D9S312 | 9q34 | 137.1 | 121 | 117/121 | 117 | NI |

| D9S1826 | 9q34 | 137.6 | 129/133 | 131/133 | 131 | |

| D9S158 | 9q34 | 138.3 | 216/218 | 216/218 | 214/216 | |

| D9S1838 | 9q34 | 139.8 | 167 | 161/167 | 161 | NI |

ISCN, International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature; NCBI, National Center for Biotechnology Information; pat dup, paternal duplication (interpretation based on the dosage analysis); pat del, paternal deletion; NI, non informative.

Seven polymorphic markers along chromosome 5 and 20 along chromosome 9 were analysed. Three markers along chromosome 5 and 10 along chromosome 9 were outside the rearranged region. A single paternal and maternal allele could be seen and confirmed that one chromosome is derived from the father and the other from the mother in both cell lines (fig 4, D5S618 and D9S1793).

Figure 4 Polymorphism analyses of D5S1981, D5S618, D9S129, D9S285, D9S1846 and D9S1793 on DNA extracted from blood of the patient (P), the mother (M) and the father (F). The size of the allele can be estimated from the scale generated by the Genotyper software.

Markers D9S129 and D9S285 show that only a single maternal allele was detected in 9pter (fig 4). The del(9p) is thus of paternal origin.

Markers derived from the duplicated regions on chromosomes 5 and 9 showed a single allele from the mother and a single one from the father. However, the peak areas were not in a 1:1 ratio but in a 1.62 (standard error 0.17):1 ratio for father's allele to mother's allele (fig 4, D5S1981 and D9S1846). This dosage analysis indicates the presence of two paternal copies in half of the blood leucocytes and is consistent with a single chromosome from the mother and a duplication in the chromosome derived from the father (where the ratio would be 3/2 to 1). The duplication would be an intrachromosomal duplication as only a single allele from the father could be detected.

This confirms the conventional and molecular cytogenetic findings that BACs containing these polymorphic markers are duplicated on the inv dup(9p) and on the dup(5p) and present in a single copy on the del(9p).

The final karyotype could be written as follows:

46,XX,del(9)(p22.1).arr cgh 9pterp22.1(GS1‐77L23→RP11‐269B5)x1.ish del(9)(p22.1) (48M17‐,503K6‐,513M16+)dn[55]/46,XX,der(9)t(5;9)(p13.3;p22.1) .arr cgh 5pterp13.3(RP11‐415K6→RP11‐53L13)x3, 9pterp22.1(GS1‐77L23→RP11‐269B5)x1, 9p22.1p13.3(RP11‐296P7→RP11‐284F1)x3 .ish der(9)t(5;9)(p13.3;p22.1)del(9)(p22.1)dup(9)(p13.3→p22.1::p22.1→qter) (53L13++,15G6+;48M17‐,503K6‐,513M16++,48L13++)dn[45].

Bioinformatic breakpoint sequence analysis

Sequence analysis with PipMaker did unravel the presence of a high level of homology (>95%) sequences of nearly 6 kb in the breakpoint regions on chromosomes 5p13.3, 9p22.1 and 9p13.3. This was confirmed in silico by pairwise blast using BLAST2 search (data not shown). The sequences were identified in Ensembl database V.38 (http://www.ensembl.org/Homo_sapiens/) to LINE repeats known as L1PA3 with its homologous L1PA2 on chromosome 5 and L1PA7 on chromosome 9.

Discussion

Mechanism

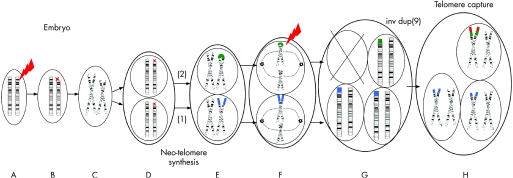

Broken chromosomes can be healed by two general pathways: either by telomerase through neo‐telomere synthesis or by telomere capture. Here we provide evidence for an independent involvement of neo‐telomere synthesis and telomere capture in the chromosome rescue process in a patient with a mosaic del(9)/der(9)t(5;9)inv dup(9). Figure 5 depicts the simplest model to describe the sequence of events generating this mosaicism. We assume that, in this patient, a DSB in the paternal chromosome 9p initiated the genomic disorder early during embryogenesis. The deletion breakpoint in the del(9) and the start of the duplication in the inv dup(9) coincide. Hence, the del(9) is not the reciprocal product of the inv dup(9). Therefore, we hypothesise that during S phase the broken chromatid replicated and the cell underwent mitosis. In one daughter cell, telomerase catalysed the addition of telomeric sequences onto the broken del(9). This mechanism is known as neo‐telomere formation. In the other daughter cell, fusion of the two sister chromatids leads to a dicentric chromosome 9. During anaphase of the next mitosis, both chromatids of that dicentric chromosome 9 would be pulled to the opposite poles of the cell, leading to their disruption in p13.3 resulting in an inv dup(9p) in one daughter cell and del(9p) in the other. A telomere capture by non‐reciprocal translocation of the chromosome 5p stabilised the inv dup(9). The chromosome 5 subtelomere capture might have occurred by a breakage‐induced recombination event, thus leaving the original chromosome 5 intact or generating another cell line with a del(5) which we did not detect in our patient.5,18,19 Another possibility is that, after the generation and stabilisation of the inv dup(9), this chromosome was broken at the same locus as the initial breakage event. However, it seems unlikely that a breakage would occur independently twice at the same 100 kb interval.

Figure 5 Schematic representation of the proposed mechanism of origin of the rearrangements during early embryonic development (refer to text for detailed description). Only chromosomes 9 are shown. Dotted lines in F indicate spindles attaching to the centromeres. The flashing red arrow shows the double‐stranded break sites. The blue dots indicate the new telomeres. The green dots indicate the inv dup(9p) fragment. The chromosome 5pter derived fragment is shown in red. (A–B) Double‐stranded breaks event in the embryo; (C) metaphase; (D) telophase; (E) metaphase, 1 neo‐telomere synthesis, 2 fusion of the broken sister chromatids; (F) anaphase‐second breakage; (G) telophase, generation of two cell lines; (H) telomere capture.

Although this sequel may appear to be a unique chain of events, two similar cases have recently been described. Kulikowski et al10 reported a girl with an equal ratio mosaic of two cell lines presenting a monosomy 9p23 in all cells and a trisomy 1q41 in half of the cells. No further investigations were performed to elucidate the mechanisms causing the abnormal chromosomes in the two cell lines. Reddy and Yang20 describe the cytogenetic analysis of a patient with a mosaic del(1)/der(1)t(1p;9p). They also invoked independent telomere stabilisation by telomerase and telomere capture of the sister chromatids. In this case, no inverted duplication was detected. The presence of such a duplication might have been overlooked or the 9p telomere capture occurred without the formation of a dicentric chromosome.

A post‐zygotic mosaic

In a recent review, Pramparo et al11 suggested that constitutional chromosomal mosaicism with two cell lines carrying two different rearranged chromosomes might arise after a meiotic error. In this case, both sister chromatids have separated either during the second meiotic cell division (MII) or during post‐zygotic mitosis. If the breakage occurred during MII, it can be expected that during MI bivalent 9 would have undergone canonic recombination involving the q arms. As a consequence, we would expect two paternal alleles on 9q, one in each of the two cell lines. Telomeric polymorphic markers on chromosome 9q have shown only one paternal and one maternal allele. Therefore, in this patient, the mosaicism originated probably during embryogenesis.

LINEs mediating the rearrangement?

Breakpoint clustering in LCRs is usually responsible for rearrangements by the mechanism of non‐allelic homologous recombination, whereas in rearrangements with scattered breakpoints, other mechanisms such as non‐homologous end joining (NHEJ) have been observed.21 Rearrangements of chromosome 9 do not show site‐specific breakpoints.22,23,24,25,26 Therefore, NHEJ seems to be the most likely mechanism for rearrangements of chromosome 9p.27 In silico sequence analysis of chromosomes 5 and 9 showed the existence in the breakpoint region 5p13.3 of L1PA2, a LINE sequence with homology with L1PA3 in the breakpoint regions in 9p13.3 and in 9p22.1 and with L1PA7 in 9p22.1. L1PA3 with its homologous L1PA2 are duplicated in four copies in 5p13.3. This LINE‐1 element could mediate the NHEJ generating the non‐reciprocal translocation of chromosome 5p healing the inv dup(9p).

Clinical considerations

This patient shows the major clinical manifestations described in the 9p deletion syndrome that comprises mental retardation, hypotonia, trigonocephaly, upslanting palpebral fissures, flat nasal bridge with anteverted nares, long filtrum and small malformed ears. Christ et al22 performed karyotype–phenotype correlations in patients with 9p mapping its critical region to a 4–6 Mb in 9p22–23.

However, our patient has a mosaic partial duplication of 5p and 9p, which may modulate the chromosome 9p partial deletion clinical presentation. Partial dup(9p) in tandem seems to give a different clinical presentation from inv dup(9p). Fryns et al28 described a girl with tandem dup(9)(p13;p22) and trisomy 9p phenotype presenting with mild mental retardation, downslanting palpebral fissures, hypertelorism without a prominent metopic ridge, whereas in a 20‐month‐old girl with inv dup(9)(p22;p13), Teebi et al25 found a psychomotor and developmental delay with hypotonia, a prominent metopic ridge and upslanting palpebral fissures.

Partial trisomy 5p is a rare event, first described in 1964 by Lejeune. Most partial trisomies 5p are the consequence of an unbalanced translocation with another autosome.27 Partial trisomies involving 5p14‐pter do not show a particular dysmorphism, whereas those including 5p13 or the complete short arm have more severe multiple congenital anomalies, mental retardation and growth failure.27 Liberfarb et al29 reported at least four members of a large translocation carrier family having 5p+/9p− with features of dup(5)(pter→p13) and del(9)(pter→p22). All died in early childhood between 4 and 27 months of age due to recurrent infections. At least two had a prominent forehead, flat nasal bridge, arachnodactyly, bilateral clubfeet, diaphragmatic and umbilical hernias, intestinal and kidney malformations. One of them had marked psychomotor retardation and brain malformations. The severe presentation could be because of the association between 5p+ and 9p−. Our patient has the same chromosomal abnormalities, but she has a milder phenotype. This could be explained by the mosaic 5p+ and/or the mosaic 9p+ which may balance the defect on chromosome 9.

In conclusion, by using molecular techniques, we provided evidence for the involvement of both neo‐telomere formation and telomere capture in chromosome healing of constitutional chromosome rearrangements.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patient and her parents for their collaboration. We wish to thank the MicroArray Facility, Flanders Interuniversity Institute for Biotechnology (VIB) for their help in spotting the arrays and the Mapping Core and Map Finishing groups of the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute for the initial clone supply and verification.

Abbreviations

aCGH - array comparative genomic hybridisation

BLAST - basic local alignment search tool

DSB - double‐strand break

FISH - fluorescence in situ hybridization

LCRs - low‐copy repeats

Footnotes

Funding: This work was made possible by grants G.0200.03 from the FWO, OT/O2/40, GOA/2006/12 and Centre of Excellence SymBioSys (Research Council K.U.Leuven EF/05/007), Catholic University of Leuven, and grant (PI020028) from the Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias (FIS), Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo, Spain. Elyes Chabchoub was supported by the Ministry of Higher Education from Tunisia (Scholarship 2005‐032/001).

Competing interests: None.

Parental informed consent was obtained for publication of figure 1.

References

- 1.Zakian V A. Telomeres: beginning to understand the end. Science 19952701601–1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bolzan A D, Bianchi M S. Telomeres, interstitial telomeric repeat sequences, and chromosomal aberrations. Mutat Res 2006612189–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright W E, Piatyszek M A, Rainey W E.et al Telomerase activity in human germline and embryonic tissues and cells. Dev Genet 199618173–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meltzer P S, Guan X Y, Trent J M. Telomere capture stabilizes chromosome breakage. Nat Genet 19934252–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bosco G, Haber J E. Chromosome break‐induced DNA replication leads to nonreciprocal translocations and telomere capture. Genetics 19981501037–1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ausems M G, Bhola S L, Post‐Blok C A.et al 18q− and 18q+ mosaicism in a mentally retarded boy. Am J Med Genet 199453296–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stephen G S, Couzin D A, Watt J L.et al Prenatal diagnosis of a case of 46,XY,18p−/46,XY,18p+ mosaicism. Prenat Diagn 1989957–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonaglia M C, Giorda R, Poggi G.et al Inverted duplications are recurrent rearrangements always associated with a distal deletion: description of a new case involving 2q. Eur J Hum Genet 20008597–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Floridia G, Piantanida M, Minelli A.et al The same molecular mechanism at the maternal meiosis I produces mono‐ and dicentric 8p duplications. Am J Hum Genet 199658785–796. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kulikowski L D, Christ L A, Nogueira S I.et al Breakpoint mapping in a case of mosaicism with partial monosomy 9p23 ‐‐> pter and partial trisomy 1q41 ‐‐> qter suggests neo‐telomere formation in stabilizing the deleted chromosome. Am J Med Genet A 200614082–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pramparo T, Giglio S, Gregato G.et al Inverted duplications: how many of them are mosaic? Eur J Hum Genet 200412713–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soler A, Sanchez A, Carrio A.et al Fetoplacental discrepancy involving structural abnormalities of chromosome 8 detected by prenatal diagnosis. Prenat Diagn 200323319–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Balkom I D, Hagendoorn J, De Pater J M.et al Partial monosomy 8p and partial trisomy 8p with moderate mental retardation. Genet Couns 1992383–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vermeesch J R, Thoelen R, Salden I.et al Mosaicism del(8p)/inv dup(8p) in a dysmorphic female infant: a mosaic formed by a meiotic error at the 8p OR gene and an independent terminal deletion event. J Med Genet 200340e93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Menten B, Maas N, Thienpont B.et al Emerging patterns of cryptic chromosomal imbalances in patients with idiopathic mental retardation and multiple congenital anomalies: a new series of 140 patients and review of the literature. J Med Genet 200643625–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vermeesch J R, Melotte C, Froyen G.et al Molecular karyotyping: array CGH quality criteria for constitutional genetic diagnosis. J Histochem Cytochem 200553413–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tatusova T A, Madden T L. BLAST 2 Sequences, a new tool for comparing protein and nucleotide sequences. FEMS Microbiol Lett 1999174247–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Slijepcevic P, Bryant P E. Chromosome healing, telomere capture and mechanisms of radiation‐induced chromosome breakage. Int J Radiat Biol 1998731–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ballif B C, Wakui K, Gajecka M, Shaffer L G. Translocation breakpoint mapping and sequence analysis in three monosomy 1p36 subjects with der(1)t(1;1)(p36;q44) suggest mechanisms for telomere capture in stabilizing de novo terminal rearrangements. Hum Genet 2004114198–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reddy K S, Yang X. Submicroscopic terminal deletion of 1p36. 3 and Xp23 hidden in complex chromosome rearrangements: independent mechanism of telomere restitution on the two chromatids, Am J Med Genet A 2003117261–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shaw C J, Lupski J R. Implications of human genome architecture for rearrangement‐based disorders: the genomic basis of disease. Hum Mol Genet 200413R57–R64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Christ L A, Crowe C A, Micale M A.et al Chromosome breakage hotspots and delineation of the critical region for the 9p‐deletion syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 1999651387–1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lukusa T, Devriendt K, Holvoet M.et al Dicentric chromosome 9 due to tandem duplication of the 9p11–q13 region: unusual chromosome 9 variant. Am J Med Genet 200091192–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanlaville D, Baumann C, Lapierre J M.et al De novo inverted duplication 9p21pter involving telomeric repeated sequences. Am J Med Genet 199983125–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teebi A S, Gibson L, McGrath J.et al Molecular and cytogenetic characterization of 9p‐ abnormalities. Am J Med Genet 199346288–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsezou A, Kitsiou S, Galla A.et al Molecular cytogenetic characterization and origin of two de novo duplication 9p cases. Am J Med Genet 200091102–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perfumo C, Cerruti Mainardi P, Cali A.et al The first three mosaic cri du chat syndrome patients with two rearranged cell lines. J Med Genet 200037967–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fryns J P, Casaer P, Van den Berghe H. Partial duplication of the short arm of chromosome 9 (p13 leads to p22) in a child with typical 9p trisomy phenotype. Hum Genet 197946231–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liberfarb R M, Atkins L, Holmes L B. A clinical syndrome associated with 5p duplication and 9p deletion. Ann Genet 19802326–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]