Abstract

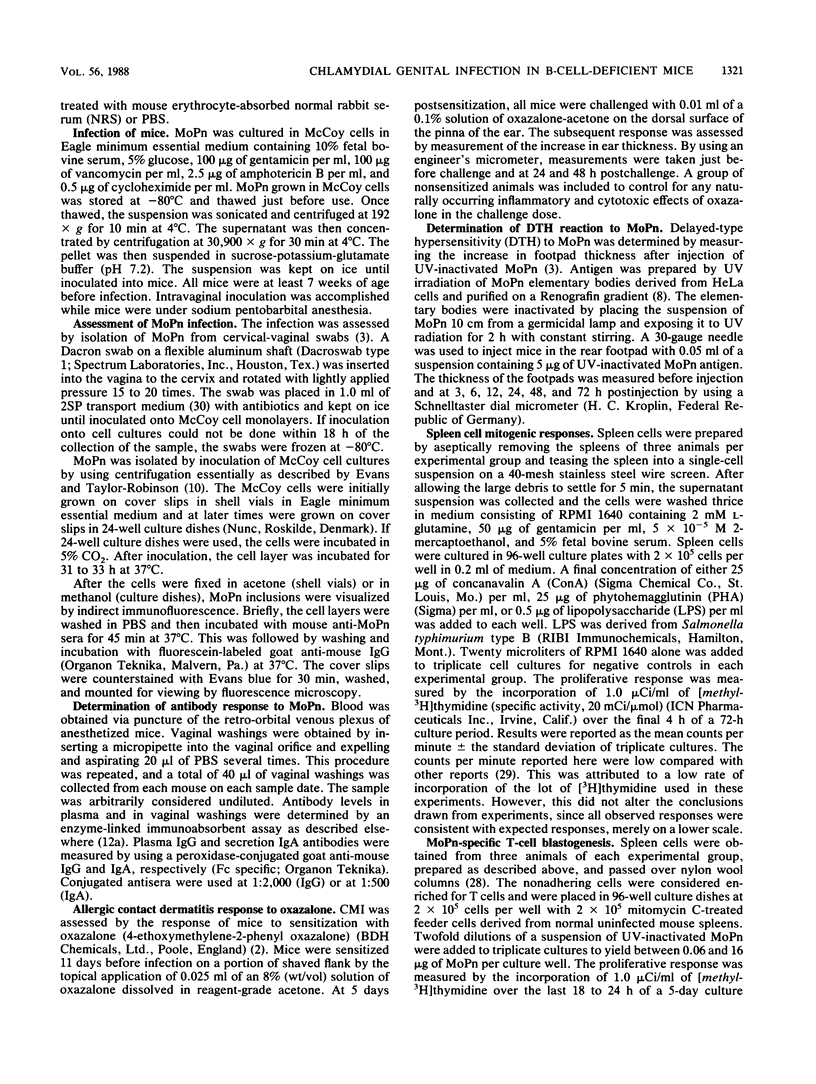

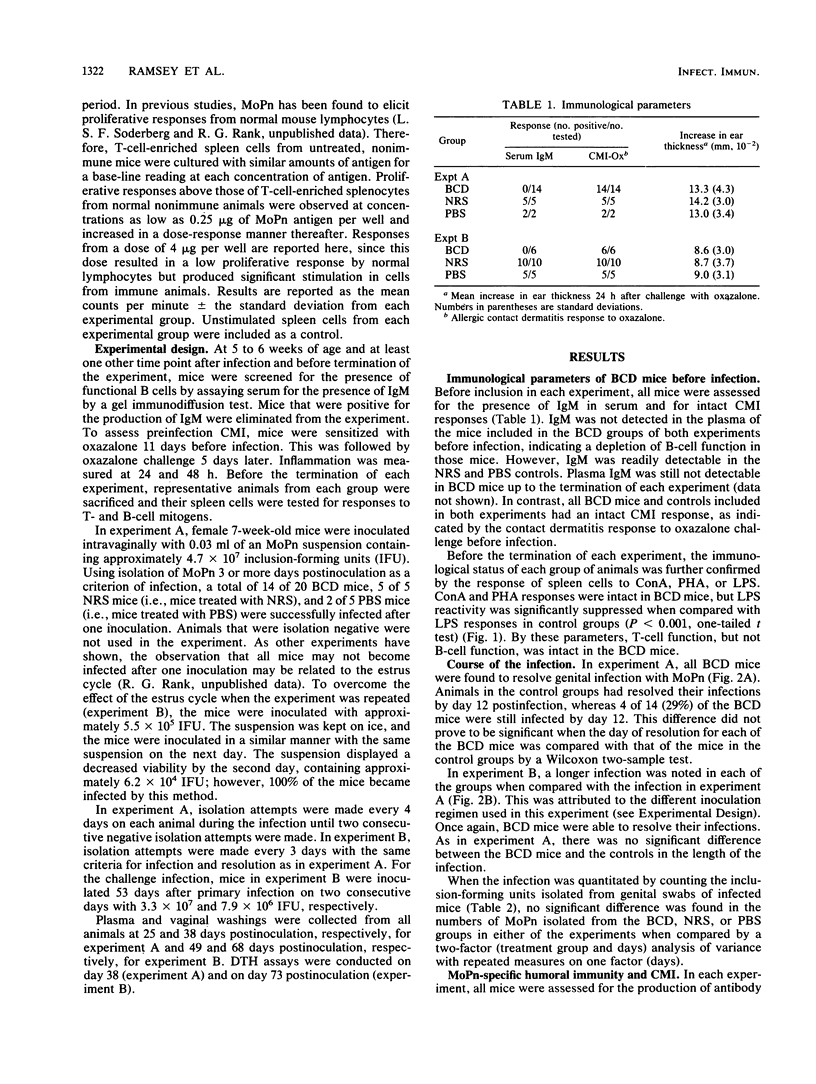

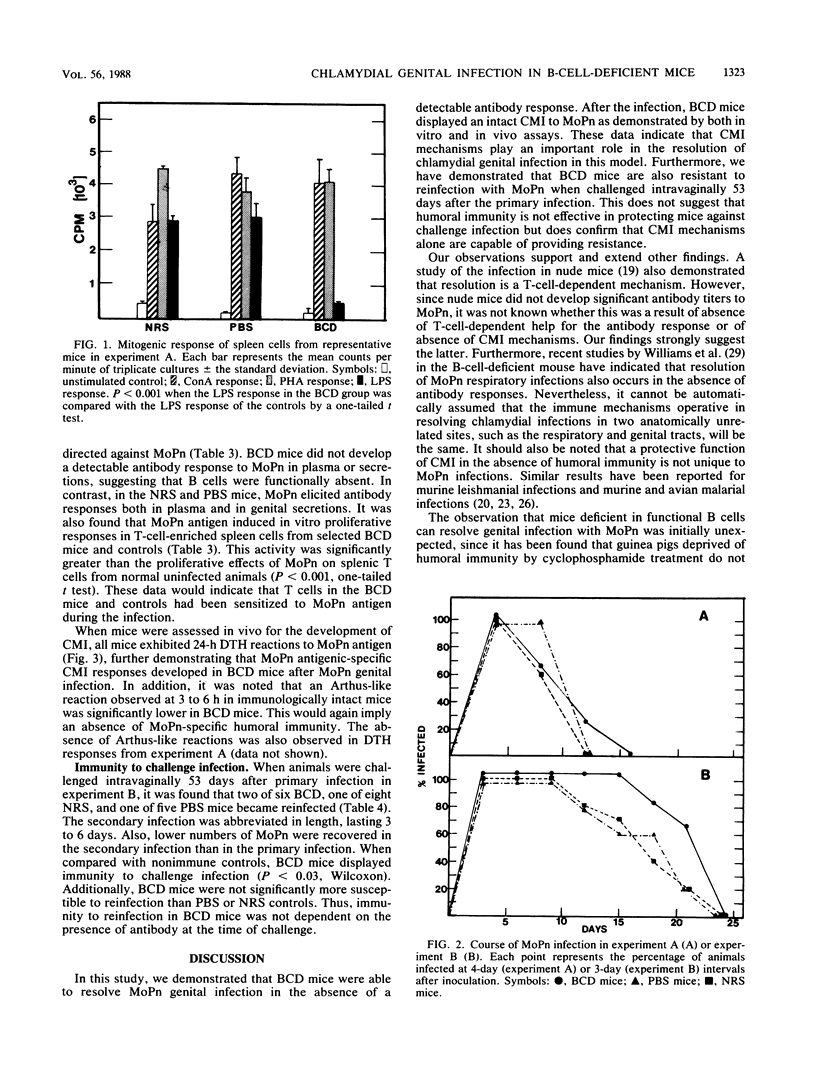

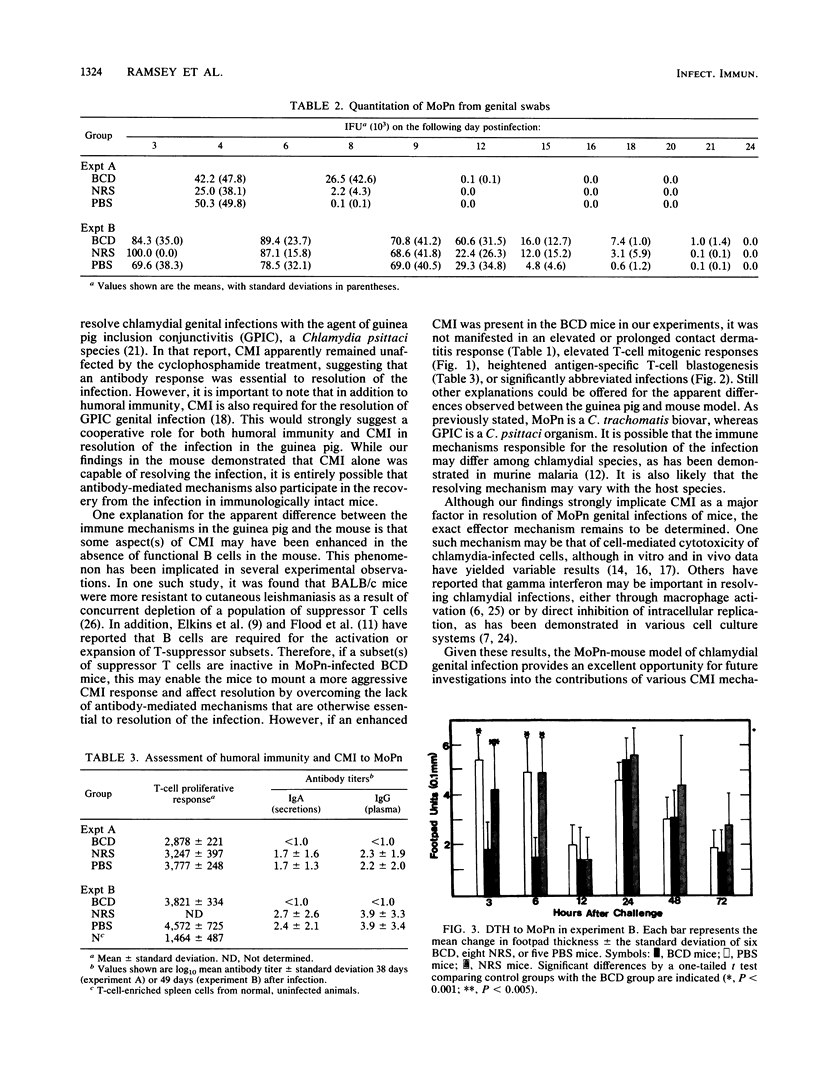

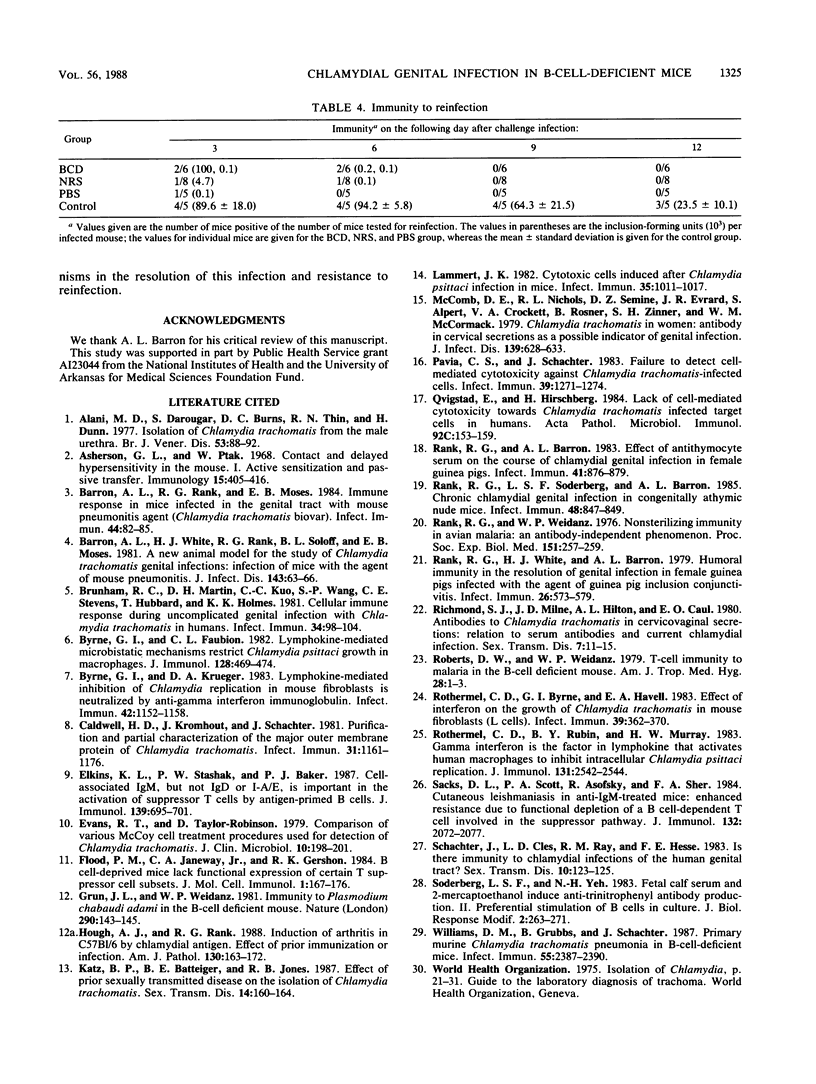

The purpose of this investigation was to determine the relative roles of the humoral and cell-mediated immune responses in the resolution of chlamydial genital infection of mice and resistance to reinfection. To this end, female BALB/c mice were rendered B cell deficient by treatment with heterologous anti-immunoglobulin M (IgM) serum from birth. Controls were similarly treated with either normal serum or phosphate-buffered saline. Before inclusion in each experiment, anti-IgM-treated mice were screened for the absence of IgM in serum and for the presence of cell-mediated immune responses. In addition, spleen cells from anti-IgM-treated mice responded to concanavalin A and phytohemagglutinin but not to lipopolysaccharide. By these criteria, mice were designated B cell deficient. B-cell-deficient mice and controls were inoculated intravaginally with a suspension of mouse pneumonitis agent (MoPn), a Chlamydia trachomatis biovar. All B-cell-deficient mice resolved the infection. Additionally, no significant difference was seen in the course of the infection in B-cell-deficient mice when compared with controls. In contrast to control mice, B-cell-deficient mice displayed no detectable antibody responses to MoPn in serum or in genital secretions. However, both B-cell-deficient mice and controls developed delayed-type hypersensitivity and T-cell proliferative responses to MoPn. When challenged 53 days after primary infection, no significant difference was seen in the resistance of B-cell-deficient mice to reinfection when compared with that of the controls. These data indicate that cell-mediated immune mechanisms play an important role in the resolution of and resistance to chlamydial genital infection in this model.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Alani M. D., Darougar S., Burns D. C., Thin R. N., Dunn H. Isolation of Chlamydia trachomatis from the male urethra. Br J Vener Dis. 1977 Apr;53(2):88–92. doi: 10.1136/sti.53.2.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asherson G. L., Ptak W. Contact and delayed hypersensitivity in the mouse. I. Active sensitization and passive transfer. Immunology. 1968 Sep;15(3):405–416. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barron A. L., Rank R. G., Moses E. B. Immune response in mice infected in the genital tract with mouse pneumonitis agent (Chlamydia trachomatis biovar). Infect Immun. 1984 Apr;44(1):82–85. doi: 10.1128/iai.44.1.82-85.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barron A. L., White H. J., Rank R. G., Soloff B. L., Moses E. B. A new animal model for the study of Chlamydia trachomatis genital infections: infection of mice with the agent of mouse pneumonitis. J Infect Dis. 1981 Jan;143(1):63–66. doi: 10.1093/infdis/143.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunham R. C., Martin D. H., Kuo C. C., Wang S. P., Stevens C. E., Hubbard T., Holmes K. K. Cellular immune response during uncomplicated genital infection with Chlamydia trachomatis in humans. Infect Immun. 1981 Oct;34(1):98–104. doi: 10.1128/iai.34.1.98-104.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne G. I., Faubion C. L. Lymphokine-mediated microbistatic mechanisms restrict Chlamydia psittaci growth in macrophages. J Immunol. 1982 Jan;128(1):469–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne G. I., Krueger D. A. Lymphokine-mediated inhibition of Chlamydia replication in mouse fibroblasts is neutralized by anti-gamma interferon immunoglobulin. Infect Immun. 1983 Dec;42(3):1152–1158. doi: 10.1128/iai.42.3.1152-1158.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell H. D., Kromhout J., Schachter J. Purification and partial characterization of the major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect Immun. 1981 Mar;31(3):1161–1176. doi: 10.1128/iai.31.3.1161-1176.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkins K. L., Stashak P. W., Baker P. J. Cell-associated IgM, but not IgD or I-A/E, is important in the activation of suppressor T cells by antigen-primed B cells. J Immunol. 1987 Aug 1;139(3):695–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans R. T., Taylor-Robinson D. Comparison of various McCoy cell treatment procedures used for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis. J Clin Microbiol. 1979 Aug;10(2):198–201. doi: 10.1128/jcm.10.2.198-201.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flood P. M., Janeway C. A., Jr, Gershon R. K. B cell-deprived mice lack functional expression of certain T suppressor cell subsets. J Mol Cell Immunol. 1984;1(3):167–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grun J. L., Weidanz W. P. Immunity to Plasmodium chabaudi adami in the B-cell-deficient mouse. Nature. 1981 Mar 12;290(5802):143–145. doi: 10.1038/290143a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hough A. J., Jr, Rank R. G. Induction of arthritis in C57B1/6 mice by chlamydial antigen. Effect of prior immunization or infection. Am J Pathol. 1988 Jan;130(1):163–172. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz B. P., Batteiger B. E., Jones R. B. Effect of prior sexually transmitted disease on the isolation of Chlamydia trachomatis. Sex Transm Dis. 1987 Jul-Sep;14(3):160–164. doi: 10.1097/00007435-198707000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammert J. K. Cytotoxic cells induced after Chlamydia psittaci infection in mice. Infect Immun. 1982 Mar;35(3):1011–1017. doi: 10.1128/iai.35.3.1011-1017.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McComb D. E., Nichols R. L., Semine D. Z., Evrard J. R., Alpert S., Crockett V. A., Rosner B., Zinner S. H., McCormack W. M. Chlamydia trachomatis in women: antibody in cervical secretions as a possible indicator of genital infection. J Infect Dis. 1979 Jun;139(6):628–633. doi: 10.1093/infdis/139.6.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavia C. S., Schachter J. Failure to detect cell-mediated cytotoxicity against Chlamydia trachomatis-infected cells. Infect Immun. 1983 Mar;39(3):1271–1274. doi: 10.1128/iai.39.3.1271-1274.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qvigstad E., Hirschberg H. Lack of cell-mediated cytotoxicity towards Chlamydia trachomatis infected target cells in humans. Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand C. 1984 Jun;92(3):153–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1984.tb00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rank R. G., Barron A. L. Effect of antithymocyte serum on the course of chlamydial genital infection in female guinea pigs. Infect Immun. 1983 Aug;41(2):876–879. doi: 10.1128/iai.41.2.876-879.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rank R. G., Soderberg L. S., Barron A. L. Chronic chlamydial genital infection in congenitally athymic nude mice. Infect Immun. 1985 Jun;48(3):847–849. doi: 10.1128/iai.48.3.847-849.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rank R. G., Weidanz W. P., Bondi A. Nonsterilizing immunity in avian malaria: an antibody-independent phenomenon. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1976 Feb;151(2):257–259. doi: 10.3181/00379727-151-39186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rank R. G., White H. J., Barron A. L. Humoral immunity in the resolution of genital infection in female guinea pigs infected with the agent of guinea pig inclusion conjunctivitis. Infect Immun. 1979 Nov;26(2):573–579. doi: 10.1128/iai.26.2.573-579.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond S. J., Milne J. D., Hilton A. L., Caul E. O. Antibodies to Chlamydia trachomatis in cervicovaginal secretions: relation to serum antibodies and current chlamydial infection. Sex Transm Dis. 1980 Jan-Mar;7(1):11–15. doi: 10.1097/00007435-198001000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts D. W., Weidanz W. P. T-cell immunity to malaria in the B-cell deficient mouse. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1979 Jan;28(1):1–3. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1979.28.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothermel C. D., Byrne G. I., Havell E. A. Effect of interferon on the growth of Chlamydia trachomatis in mouse fibroblasts (L cells). Infect Immun. 1983 Jan;39(1):362–370. doi: 10.1128/iai.39.1.362-370.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothermel C. D., Rubin B. Y., Murray H. W. Gamma-interferon is the factor in lymphokine that activates human macrophages to inhibit intracellular Chlamydia psittaci replication. J Immunol. 1983 Nov;131(5):2542–2544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacks D. L., Scott P. A., Asofsky R., Sher F. A. Cutaneous leishmaniasis in anti-IgM-treated mice: enhanced resistance due to functional depletion of a B cell-dependent T cell involved in the suppressor pathway. J Immunol. 1984 Apr;132(4):2072–2077. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schachter J., Cles L. D., Ray R. M., Hesse F. E. Is there immunity to chlamydial infections of the human genital tract? Sex Transm Dis. 1983 Jul-Sep;10(3):123–125. doi: 10.1097/00007435-198307000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderberg L. S., Yeh N. H. Fetal calf serum and 2-mercaptoethanol induce anti-trinitrophenyl antibody production: II. Preferential stimulation of B cells in culture. J Biol Response Mod. 1983;2(3):263–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. M., Grubbs B., Schachter J. Primary murine Chlamydia trachomatis pneumonia in B-cell-deficient mice. Infect Immun. 1987 Oct;55(10):2387–2390. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.10.2387-2390.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]