Abstract

On 5 August 1968, publication of the Harvard Committee's report on the subject of “irreversible coma” established a standard for diagnosing death on neurological grounds. On the same day, the 22nd World Medical Assembly met in Sydney, Australia, and announced the Declaration of Sydney, a pronouncement on death, which is less often quoted because it was overshadowed by the impact of the Harvard Report. To put those events into present-day perspective, the authors reviewed all papers published on this subject and the World Medical Association web page and documents, and corresponded with Dr A G Romualdez, the son of Dr A Z Romualdez. There was vast neurological expertise among some of the Harvard Committee members, leading to a comprehensible and practical clinical description of the brain death syndrome and the way to diagnose it. This landmark account had a global medical and social impact on the issue of human death, which simultaneously lessened reception of the Declaration of Sydney. Nonetheless, the Declaration of Sydney faced the main conceptual and philosophical issues on human death in a bold and forthright manner. This statement differentiated the meaning of death at the cellular and tissue levels from the death of the person. This was a pioneering view on the discussion of human death, published as early as in 1968, that should be recognised by current and future generations.

The year 1968 was a crucial time for defining human death on neurological grounds. On 5 August, the Ad Hoc Committee of the Harvard Medical School to Examine the Definition of Brain Death published its report, “A definition of irreversible coma”, in the Journal of the American Medical Association1—a milestone event. On the same day, the 22nd World Medical Assembly, meeting in Sydney, Australia, announced the Declaration of Sydney,2,3 a pronouncement on death that is less often quoted because it was overshadowed by the impact of the Harvard Report.1,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17 The review here is advanced to preserve for current and future generations the pioneering contribution of the Declaration of Sydney.

To put those events into present-day perspective, we have reviewed all papers published on this subject and the World Medical Association (WMA) web page and documents,18 and have corresponded with Dr A G Romualdez (the son of Dr A Z Romualdez).

The 22nd World Medical Assembly

The WMA is an international organisation representing physicians. It was founded on 17 September 1947, when physicians from 27 different countries met at the First General Assembly of the WMA in Paris. According the WMA, “the organization was created to ensure the independence of physicians, and to work for the highest possible standards of ethical behavior and care by physicians, at all times.”2,3,18,19,20,21,22 In 1968, from 5 to 9 August, delegates from 26 countries of 64 WMA member nations met in Sydney, Australia, to hold the WMA's 22nd World Medical Assembly.2,3,22

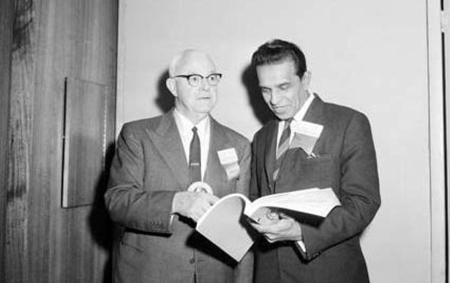

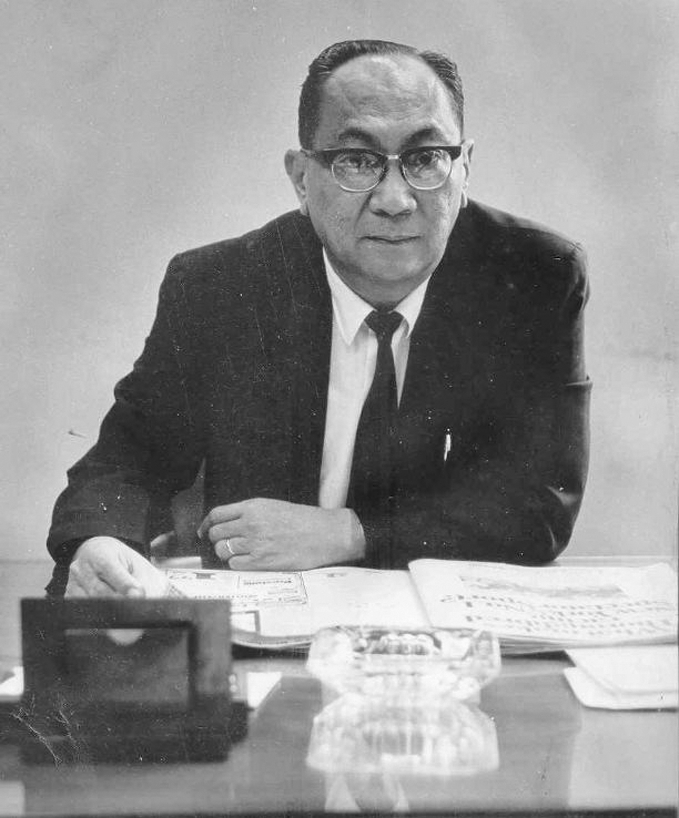

Distant nations from the Caribbean, Africa, the former Soviet Union, and the USA were among the participants. Sir Leonard Mallen (Australia) was the Chairman of the meeting (fig 1), and Dr A Z Romualdez (Philippines) was the WMA Secretary General (fig 2). The Assembly issued an interim statement, known as the Declaration of Sydney. Stanley S B Gilder, the executive editor of the WMA's journal from 1959 to 1973,2,3,19,20,21,22,23 published a résumé of the 22nd World Medical Assembly, with special emphasis on the Declaration of Sydney on human death (box 1).3

Figure 1 Sir Leonard Mallen, Australia (left), and Dr A P Mittra, India (right), at the 22nd World Medical Assembly, Sydney, 1968. Courtesy of the National Archives of Australia.

Figure 2 Dr A Z Romualdez (Philippines), Secretary General of the World Medical Association in 1968. Courtesy of Dr A G Romualdez, Dr Romualdez's son.

The declaration of Sydney

The WMA had been concerned about a new definition of death in an epoch of advances in resuscitation, and the increasing need to find organs for transplantation. Moreover, there was public uneasiness about removing organs from living patients. Hence, the WMA Committee on Ethics and its Council had organised a study two years earlier, to formulate an account of death under the new circumstances.2,3

The Declaration of Sydney touched on key conceptual issues on human death.24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34 It affirmed that in most situations physicians could diagnose death by the classical cardiorespiratory criteria. Nonetheless, “two modern practices in medicine” led them to revise the “time of death”2,3,22:

1) The ability to maintain by artificial means the circulation …

2) The use of cadaver organs such as heart or kidneys for transplantation.

The essential public statement was that “Death is a gradual process at the cellular level with tissues varying in their ability to withstand deprivation of oxygen”, but this document went further, stating that, clinically, death, “lies not in the preservation of isolated cells but in the fate of a person”.3

Declaration of Sydney on Human Death. Adopted by the 22nd World Medical Assembly, Sydney, Australia, 5–9 August 1968

The determination of the time of death is in most countries the legal responsibility of the physician and should remain so. Usually the physician will be able without special assistance to decide that a person is dead, employing the classical criteria known to all physicians.

Two modern practices in medicine, however, have made it necessary to study the question of the time of death further:

1—the ability to maintain by artificial means the circulation of oxygenated blood through tissues of the body which may have been irreversibly injured and

2—the use of cadaver organs such as heart or kidneys for transplantation.

A complication is that death is a gradual process at the cellular level with tissues varying in their ability to withstand deprivation of oxygen. But clinical interest lies not in the state of preservation of isolated cells but in the fate of a person. Here the point of death of the different cells and organs is not so important as the certainty that the process has become irreversible by whatever techniques of resuscitation that may be employed.

This determination will be based on clinical judgment supplemented if necessary by a number of diagnostic aids, of which the electroencephalograph is currently the most helpful. However, no single technological criterion is entirely satisfactory in the present state of medicine nor can any one technological procedure be substituted for the overall judgment of the physician. If transplantation of an organ is involved, the decision that death exists should be made by two or more physicians and the physicians determining the moment of death should in no way be immediately concerned with performance of transplantation.

Determination of the point of death of the person makes it ethically permissible to cease attempts at resuscitation and in countries where the law permits, to remove organs from the cadaver provided that prevailing legal requirements of consent have been fulfilled.

The Sydney declaration stated that the determination of death “will be based on clinical judgment, supplemented if necessary by a number of diagnostic aids”, emphasising the EEG. Nonetheless, it asserted that “the overall judgment of the physician” could not be replaced by any ancillary test. The statement also recommended that two or more physicians should make the diagnosis of death when organs were removed for transplantation.2,3

Table 1 compares the recommendations of the Sydney declaration2,3 and the Harvard Committee.1 The two expressed similar reasons for creating a new definition of death: the development of resuscitation, life support techniques and transplantation. The Sydney declaration went further, proposing a more philosophical explanation about the relationship of death and “the fate of a person”. The Harvard Committee did not provide a clear concept of death. The Sydney declaration did not use the term “brain death”, and the Harvard Committee, although mentioning that term, finally chose “irreversible coma”. The Harvard Committee provided a detailed set of clinical criteria, while the Sydney declaration only mentioned clinical judgment. Both the Sydney declaration and the Harvard Committee proposed the use of EEG. For the diagnosis of death and transplantation, the Sydney declaration proposed that the diagnosis of death should be made by two or more physicians not involved in transplantation, while the Harvard Committee stated that the declaration of death should be done first, and then physicians not involved in the transplantation procedure should be the ones to turn off the respirator. Both committees warranted a legal regulation of this issue.

Table 1 Comparison of the Declaration of Sydney and Harvard Committee's report on human death.

| Issues to compare | Declaration of Sydney | Harvard Committee report | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reasons for a new definition of death | a) “The ability to maintain by artificial means the circulation …” | a) Improvement in resuscitative and supportive measures … the result is an individual whose heart continues to beat but whose brain is irreversibly damaged | ||

| b) “The use of cadaver organs such as heart or kidneys for transplantation” | b) Obsolete criteria for the definition of death can lead to controversy in obtaining organs for transplantation | |||

| Concept of death | Although it does not provide a definition of brain death, it goes further, stating that death lies not in the state of preservation of isolated cells but in the fate of a person | The Committee mentioned that their primary purpose was to define irreversible coma as a new criterion for death; a clear concept of death was not provided | ||

| Use of the term brain death | Not used | Although the term brain death was discussed, the Committee recommended “irreversible coma” | ||

| Clinical criteria | Defended clinical judgment, but did not provide clinical criteria | Clinical criteria provided for diagnosis of brain death | ||

| Ancillary tests | Proposed use of EEG | Proposed use of EEG. One year later stated that EEG was not essential for diagnosis of brain death | ||

| Termination of resuscitation and respirator | Determination of death of the person makes it ethically permissible to cease attempts to resuscitate | Stated that declaration of death should be made first, followed by decision to turn off the respirator | ||

| Diagnosis of death and transplantation | Diagnosis of death should be made by two or more physicians not involved in transplantation | The declaration of death should be made by physicians not involved in transplantation procedures | ||

| Legal issues | In countries where the law permits it, removal of organs from the cadaver was allowed | Emphasised that the USA legal system was very much in need of following the kind of analysis and recommendations for medical procedures in cases of irreversible brain damage as suggested by the Harvard Committee |

The 35th World Medical Assembly, Venice, Italy, October 1983

The Declaration of Sydney on death2,3 was amended during the 35th World Medical Assembly, by the addition of a key point on the diagnosis of brain death. This meeting was chaired by A G N Sinha (India). André Wynen from Belgium was the WMA Secretary General.35,36 A noteworthy comment was pronounced:

It is essential to determine the irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brain stem.

In this amended version of the Sydney declaration, the EEG was not mentioned. No other issues were modified.

Discussion

Before 1968, two sets of events occurred that have a bearing on the development of the Harvard Committee report and the Sydney declaration.37,38,39 In 1957, a group of anesthesiologists pointed out the problem of maintaining the body “alive” in the absence total brain function. This quandary was presented to Pope Pius XII and resulted in publication of a papal allocution, The Prolongation of Life.40 Significant statements included that the pronouncement of death was not the province of the church—“It remains for the doctor ... to give a clear and precise definition of “death” and the moment of “death”.” Another major point was that “... where the situation was “hopeless” ... death should not be opposed by “extraordinary means”. Although, precise definitions of hopeless and extraordinary were not stated, it was clear that in such cases resuscitation could be discontinued and death be unopposed.

This papal allocution lead to research, as exemplified by three groups of French neurologists and neurophysiologists during 1959, who independently studied comatose and apnoeic patients, described by the terms “death of the nervous system”38,41 and “coma dépassé”, translated as beyond coma or ultra coma and subsequently by others as irreversible coma.37,39 These patients were respirator dependent, in unresponsive coma and areflexive. EEG and deep intracranial electrical activity (from the cortex, thalamus and deep cerebral structures) were entirely absent. The investigators' conclusion was that the brains of these patients were irreversibly dysfunctional.

The WMA ethical committee and its council began discussions on the subject of death,3,18,35 2 years before the first heart transplant by Christian Barnard in 1967.42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52 Wijdicks recently wrote that the first idea for the creation of the Harvard Committee was recorded in a letter from Henry Beecher to Robert H Ebert in September 1967. The Harvard Committee worked from April to June 1968.12 Hence, the Sydney and Harvard committees worked in parallel for several months, without either being aware of the other's work.

The Sydney declaration faced up to the fundamental philosophical issues on human death in a bold and straightforward manner. A distinction was now being made between death at the cellular and tissue levels and death of the person.2,3,22 Later, Korein went further, commenting that with the advent of multicellular organisms, the life of the organism as a whole could no longer be defined in terms of cellular function alone. The definition of life of individual unicellular examples comprises the basic functions of the metabolic and reproductive features of the specific organism, allowing it to expand in a direction of decreased entropy production (eg, bacteria, amoeba or zygote).53,54,55 He stressed that “in a multicellular organism a large mass of cells might be alive but this did not indicate that the organism as a whole was alive.”53,56,57,58 Machado has recently defended the idea that a definition of human death should include the function that provides the key human attributes and the highest level of control in the hierarchy of integrating functions within the human organism.31,33,59,60 Hence, when the Sydney declaration referred to the “fate of a person”,2,3 it was clearly trying to provide an essential conceptual explanation of human death.

Any full account of death should include three distinct elements: the definition of death, the criteria (anatomical substratum) of brain death and the tests to prove that the criteria have been satisfied. To define death is mainly a philosophical task, while the criteria and tests are medical tasks. Specific criteria and tests must harmonise with a given definition. The definition must recognise the “quality that is so essentially significant to a living entity that its loss is termed death”.61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70

Hence, in comparing the documents, the Sydney declaration went further in conceptual and philosophical arguments about human death,2,3,22 while the Harvard Committee emphasised a clinical explanation of brain death, describing in detail the anatomical substratum and tests.1 The differences were surely related to the composition of committees. Wijdicks noted the importance of neurologists Robert Schwab and Raymond Adams at Harvard, emphasising the thorough description of a “permanently nonfunctioning brain” and proposing clinical criteria.12 The WMA committee members' expertise was related more to an ethical and public health background.18,19,35 For example, Gilder also made note of a symposium on biology and ethics, held in London in September 1968, a month after the Sydney declaration, and the issues discussed were (1) the new ethical issues raised by advance in biology—cadaver organ transplantation, contraception, therapeutic abortion, biological warfare and so on, and (2) the role of biology in either supporting or founding general ethical systems.22 It is clear that ethicists in the late 1960s were facing up to those new challenges relating to advances in resuscitation techniques and transplants, as Henry K Beecher, chairman of the Harvard Committee, noted.71,72,73

Both committees defended the development of organ transplants.2,3 Nonetheless, Wijdicks, who chronicled in detail the Harvard Committee work, stated, “I am uncertain after reading the documents whether an alleged agenda of facilitating transplantation through a new construct of death existed.”12

It is easy to understand why, during the 35th World Medical Assembly, in 1983, the Sydney declaration was amended under the influence of Report of the President's Commission. In July 1981, the President's Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Behavioral Research presented a report (Defining Death) to the President, Congress and the relevant US government departments.74,75,76,77 It affirmed:

An individual who has sustained either (1) irreversible cessation of circulatory and respiratory functions, or (2) irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brain stem, is dead. A determination of death must be made in accordance with accepted medical standards.

The report of the President's Commission permitted consolidation of the whole-brain criterion of death. Bernat and others proposed that a non-functioning entire brain provokes the permanent cessation of the functioning of the organism as a whole.61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90 After the President's Commission report, this view of death had worldwide social acceptance,24,91,92,93,94,95 which explains its undoubted influence on the Declaration of Sydney's amendment that emerged in 1983 from the 35th World Medical Assembly.35

Conclusion

The Harvard Report was a breakthrough, establishing a paradigm for diagnosing death by neurological criteria. The report was an enormous step forward in the discussion of human death on neurological grounds.1,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13 There was vast neurological expertise among some of the Harvard Committee members, leading to a comprehensible and practical clinical description of the brain death syndrome and how to diagnose it.12 This landmark account had a global medical and social impact on the issue of human death, which simultaneously lessened reception of the Sydney declaration.

Nonetheless, the Sydney declaration faced the main conceptual and philosophical issues on human death in a bold and forthright manner. This statement differentiated the meaning of death at the cellular and tissue levels from death of the person.2,3 This was a pioneering view on the discussion of human death, published as early as in 1968, which should be recognised.

Abbreviations

WMA - World Medical Association

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.A definition of irreversible coma Report of the Ad Hoc Committee of the Harvard Medical School to Examine the Definition of Brain Death. JAMA 1968205337–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilder S. [WMA makes out a declaration about the definition of death]. (In Swedish). Lakartidningen 1968653576–3580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilder S S B. Twenty-second World Medical Assembly. Br Med J 19683493–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zamperetti N, Bellomo R, Defanti C A.et al Irreversible apnoeic coma 35 years later. Towards a more rigorous definition of brain death? Intensive Care Med 2004301715–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wuermeling H B. Brain-death as an anthropological or as a biological concept. Forensic Sci Int 199469247–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joynt R J. Landmark perspective: A new look at death. JAMA 1984252680–682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Till-d'Aulnis de Bourouill H A. Diagnosis of death in comatose patients under resuscitation treatment: a critical review of the Harvard report. Am J Law Med 197621–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ashwal S. Clinical diagnosis and confirmatory testing of brain death in children. In: Wijdicks EFM, ed. Brain death. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 200191–114.

- 9.Wijdicks E F. Determining brain death in adults. Neurology 1995451003–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wijdicks E F. The diagnosis of brain death. N Engl J Med 20013441215–1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wijdicks E F. Brain death worldwide: accepted fact but no global consensus in diagnostic criteria. Neurology 20025820–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wijdicks E F. The neurologist and Harvard criteria for brain death. Neurology 200361970–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wijdicks E F M.Brain death. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001

- 14.Alderete J F, Jeri F R, Richardson E P., Jret al Irreversible coma: a clinical, electroencephalographic and neuropathological study. Trans Am Neurol Assoc 19689316–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beecher H K. After the “definition of irreversible coma”. N Engl J Med 19692811070–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beecher H K. Definitions of “life” and “death” for medical science and practice. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1970169471–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beecher H K, Dorr H I. The new definition of death. Some opposing views. Int Z Klin Pharmakol Ther Toxikol 19715120–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Medical Association http://www.wma.net/e/ (accessed 30 October 2007)

- 19.Gilder S. The World Medical Association. Med J Aust 196249741–746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilder S S. World Medical Association: nineteenth general assembly. Br Med J 19652810–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gilder S. World's doctors meet to discuss medical care problems. Med J Aust 196621200–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilder S S. Biology and ethics. Can Med Assoc J 1968991013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gilder S S. World Medical Association Assembly in New Delhi. Br Med J 196221459–1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pallis C. Brainstem death. In: Braakman R, ed. Handbook of clinical neurology: head injury, vol 13. Amsterdam: Elsevier 1990441–496.

- 25.Pallis C. Defining death. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1985291666–667. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pallis C. Brain stem death—the evolution of a concept. Med Leg J 19875584–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pallis C. Further thoughts on brainstem death. Anaesth Intensive Care 19952320–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Machado-Curbelo C. [A new formulation of death: definition, criteria and diagnostic tests]. (In Spanish). Rev Neurol 1998261040–1047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Machado-Curbelo C. [Do we defend a brain oriented view of death?]. Rev Neurol 200235387–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Machado C, García-Tigera J, García O.et al Muerte encefálica. Criterios diagnósticos. Rev Cubana Med 199130181–206. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Machado C. ed. Brain death: a reappraisal.. New York: Springer Science 2007

- 32.Machado C. Una nueva definición de la de muerte según criterios neurológicos. In: Esteban A, Escalante A, eds. Muerte encefálica y donación de órganos. Madrid: Comunidad Autónoma de Madrid, 199527–51.

- 33.Machado C, Sherman D L.Brain death and disorders of consciousness, vol 50. New York: Kluwer Academics/Plenum 2004

- 34.Machado C. A new definition of death based on the basic mechanisms of consciousness generation in human beings. In: Machado C, ed. Brain death (proceedings of the Second International Symposium on Brain Death). Amsterdam: Elsevier Science, 199557–66.

- 35.World Medical Association World Medical Association/History. http://www.wma.net/e/history/index.htm (accessed 30 October 2007)

- 36.World Medical Association Statements on terminal illness and boxing adopted by the 35th World Medical Assembly, Venice, Italy—October, 1983. Med J Aust 1984140431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mollaret P, Goulon M. Coma dépassé (preliminary memoir). Rev Neurol (Paris) 19591013–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wertheimer P, Jouvet M, Descotes J. [Diagnosis of death of the nervous system in comas with respiratory arrest treated by artificial respiration]. (In French). Presse Med 19596787–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fischgold H, Mathis P. Obnubilations, comas et stupeurs. Electroencephogr Clin Neurophysiol 1959(Suppl 11)1–124.

- 40.Pius X I I. The prolongation of life [an address of Pius XII to an International Congress of Anesthesiologists, Nov. 24, 1957]. The Pope speaks. Vatican City, 1958;393–8

- 41.Jouvet M. Diagnostic électro-sous-cortico-graphique de la mort du système nerveux central au cours de certains comas. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 195911805–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beck W, Barnard C N, Schrire V. Heart rate after cardiac transplantation. Circulation 196940437–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barnard C N, Cooper D K. Clinical transplantation of the heart: a review of 13 years' personal experience. J Roy Soc Med 198174670–674. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barnard C N. The present status of heart transplantation. S Afr Med J 197549213–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barnard C N, Harlem O K. We interview: Christian N. Barnard, M. D. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 1970901106–1109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barnard C N. Experience at Cape Town with human to human heart transplantation. Laval Med 197041119–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barnard C N. [Heart transplantation in man]. (In Russian). Eksp Khir Anesteziol 19691446–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barnard C N. Human heart transplantation. Can Med Assoc J 196910091–104. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barnard C N. Human cardiac transplantation. An evaluation of the first two operations performed at the Groote Schuur Hospital, Cape Town. Am J Cardiol 196822584–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barnard C N. What we have learned about heart transplants. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 196856457–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barnard C N. The operation. A human cardiac transplant: an interim report of a successful operation performed at Groote Schuur Hospital, Cape Town. S Afr Med J 1967411271–1274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Barnard C. Reflections on the first heart transplant. S Afr Med J. 1987;72:XIX–XX [PubMed]

- 53.Korein J. Brain death. In: Cotrell JE, Tundorf H, eds. Anaesthesia and neurosurgery. St Louis: C V Mosby, 1980282–432.

- 54.Korein J. The problem of brain death: development and history. Ann N Y Acad Sci 197831519–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Korein J. Ontogenesis of the fetal nervous system: the onset of brain life. Transplant Proc 199022982–983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Braunstein P, Korein J, Kricheff I. Bedside assessment of cerebral circulation. Lancet 197211291–1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Korein J. The diagnosis of brain death. Semin Neurol 1984452–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Korein J, Machado C. Brain death: updating a valid concept for 2004. Adv Exp Med Biol 20045501–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Machado C. Death on neurological grounds. J Neurosurg Sci 199438209–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Machado C. Consciousness as a definition of death: its appeal and complexity. Clin Electroencephalogr 199930156–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bernat J L. Ethical issues in neurology. Philadelphia: Lippincott 1991

- 62.Bernat J L, Culver C M, Gert B. On the definition and criterion of death. Arch Intern Med 198194389–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bernat J L, Culver C M, Gert B. Definition of death. Ann Intern Med 198195652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bernat J L, Culver C M, Gert B. Defining death in theory and practice. Hastings Cent Rep 1982125–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bernat J L. The definition, criterion, and statute of death. Semin Neurol 1984445–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bernat J L, Culver C M, Gert B. Definition of death. Ann Intern Med 1984100456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bernat J L. Brain death. Occurs only with destruction of the cerebral hemispheres and the brain stem. Arch Neurol 199249569–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bernat J L. How much of the brain must die in brain death? J Clin Ethics 1992321–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bernat J L. A defense of the whole-brain concept of death. Hastings Cent Rep 19982814–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bernat J L. The concept and practice of brain death. Prog Brain Res 2005150369–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Beecher H K. Ethics and clinical research. N Engl J Med 19662741354–1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Beecher H K. Ethical problems created by the hopelessly unconscious patient. N Engl J Med 19682781425–1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Beecher H K. Ethics and clinical research. 1966. Bull World Health Organ 200179367–372. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.President's Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Behavioural Research: defining death Medical legal and ethical issues in the determination of death. Washington DC: US Government Printing Office 1981

- 75.Guidelines for the determination of death Report of the medical consultants on the diagnosis of death to the President's Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research. Conn Med 198246207–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Guidelines for the determination of death Report of the medical consultants on the diagnosis of death to the President's Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research. Crit Care Med 19821062–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Guidelines for the determination of death Report of the medical consultants on the diagnosis of death to the President's Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research. JAMA 19812462184–2186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Capron A M, Lynn J, Bernat J L.et al Defining death: which way? Hastings Cent Rep 19821243–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bernat J L. Philosophical and ethical aspects of brain death. In: Wijdicks EFM, ed. Brain death. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001171–188.

- 80.Bernat J L. The biophilosophical basis of whole-brain death. Soc Philos Policy 200219324–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bernat J L. On irreversibility as a prerequisite for brain death determination. Adv Exp Med Biol 2004550161–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Young G B, Lee D. A critique of ancillary tests for brain death. Neurocrit Care 20041499–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Young G B, Shemie S D, Doig C J.et al Brief review: the role of ancillary tests in the neurological determination of death. Can J Anaesth 200653620–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Browne A. Whole-brain death reconsidered. J Med Ethics 1983928–31, 44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ingvar D H. Brain death—total brain infarction. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand Suppl 197145129–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shewmon D A. “Brain death”: a valid theme with invalid variations, blurred by semantic ambiguity. In: Angstwurm H, Carrasco de Paula I, eds. Working Group on The Determination of Brain Death and its Relationship to Human Death. Vatican City: Pontificia Academia Scientiarum, 199223–51.

- 87.Shewmon D A. “Brainstem death,” “brain death” and death: a critical re-evaluation of the purported equivalence. Issues Law Med 199814125–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Shewmon D A, Shewmon E S. The semiotics of death and its medical implications. Adv Exp Med Biol 200455089–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Potts M. A requiem for whole brain death: a response to D. Alan Shewmon's ‘the brain and somatic integration'. J Med Philos 200126479–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Walton D N. Neocortical versus whole-brain conceptions of personal death. Omega (Westport) 198112339–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pallis C. ABC of brain stem death. Reappraising death. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 19822851409–1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pallis C. ABC of brain stem death. From brain death to brain stem death. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 19822851487–1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Pallis C. Whole-brain death reconsidered-physiological facts and philosophy. J Med Ethics 1983932–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Pallis C. ABC of brain stem death. The arguments about the EEG. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1983286284–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Machado C. The first organ transplant from a brain-dead donor. Neurology 2005641938–1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]