Abstract

Objective

To evaluate whether children's agricultural work practices were associated with agricultural injury and to identify injury and work practice predictors.

Design

Analyses were based on nested case–control data collected by the Regional Rural Injury Study‐II (RRIS‐II) surveillance study in 1999 and 2001 by computer‐assisted telephone interviews.

Subjects

Cases (n = 425) and controls (n = 1886) were persons younger than 20 years of age from Midwestern agricultural households. Those reporting agricultural injuries became cases; controls (no injury) were selected using incidence density sampling.

Main outcome measures

Multivariate logistic regression was used to estimate the risks of injury associated with agricultural work, performing chores earlier than developmentally appropriate, hours worked per week, and number of chores performed.

Results

Increased risks of injury were observed for children who performed chores 2–3 years younger than recommended, compared to being “age‐appropriate” (odds ratio (OR) = 2.6, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.4–4.5); performed any agricultural work (3.9 (2.6–5.6)); performed seven to ten chores per month compared to one chore (2.2 (1.3–3.5)); and worked 11–30 or 31–40 h per week compared to 1–10 h (1.6 (1.2–2.1) and 2.2 (1.3–3.7), respectively). Decreased risks of injury were observed for non‐working children compared to children performing what are commonly considered safe levels of agricultural work.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated elevated risks of agricultural injury among children who perform developmentally inappropriate chores. Results suggest that the efficacy of age restrictions for preventing the occurrence of childhood agricultural injuries warrants further evaluation.

Agricultural families are exposed to machinery, livestock, chemicals, and other agricultural‐related hazards that potentially put them at a higher risk of injuries.1 In 2004, in the United States (US), the fatal and disabling injury rates per 100 000 agricultural workers were 29.2 and 5000, 8.35 and 1.67 times greater, respectively, than the rates for all occupations combined.2 Between 1995 and 2000, children younger than 20 years of age averaged 116 agricultural fatalities per year (annualized rate: 9.3 per 100 000 youth).3 In 2001, youth visiting, living on, or hired to work on US agricultural operations incurred an estimated 22 648 injuries; 16 851 of which (15.7 injuries/1000 household youth) were incurred by youth living on farms.4

Children are commonly expected to participate in agricultural‐related work; however, family operations are exempt from federal labor and safety standards. Parents regulate their children's occupational exposures in the agricultural environment, often assigning children tasks beyond their developmental ability.5,6,7,8 To help parents assess the developmental readiness of children aged 7–16 years to perform agricultural work, the North America Guidelines for Children's Agricultural Tasks (NAGCAT) were developed to provide voluntary age guidelines for 62 common tasks.9

Agricultural work practice decisions are often “framed within an economic model where the costs of possible injury outcomes are not weighted heavily”,10 thus contributing to the perception that economic and developmental benefits of childhood agricultural work outweigh its risks.5,11,12 This framework also justifies the exemptions of family operations from the Fair Labor Standards Act13 and of operations employing fewer than 11 workers from the Occupational Safety and Health Act.14 To better understand the risk of work practice decisions and to inform injury prevention efforts, we evaluated the associations between children's work practices and childhood agricultural injury.

Methods

Study design and subjects

This study was based on nested case–control data collected in the Regional Rural Injury Study‐II (RRIS‐II) surveillance studies in 1999 and 2001. The RRIS II, Phase 1 and 2 studies were designed to identify the incidence and consequences of and risk factors for children's agricultural injuries and are described elsewhere.15,16 RRIS‐II materials are available at http://enhs.umn.edu/riprc/riprc.html. Approval was obtained from the University of Minnesota, Institutional Review Board, Human Subjects Committee.

A random sample of 16 000 agricultural operations (3200 from each participating state: Minnesota, Wisconsin, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Nebraska) was generated from the U.S. Department of Agriculture's National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) Master ListFrame of Agricultural Operations for each data collection year. Households were eligible if, as of 1 January 1999 or 1 January 2001, they actively farmed or ranched, included children younger than 20 years of age in residence, and had produced at least $1000 of agricultural goods in the prior year or participated in a Conservation Reserve Program (CRP).

Cases (n = 425) and controls (n = 1886) were children younger than 20 years of age identified from the RRIS‐II database. Children with agricultural injuries reported in the ascertainment period were selected as cases. Children with no reported agricultural injuries were selected as controls using an incidence density sampling scheme based on the months contributing person‐time at risk. Respondents were asked about both fatal and non‐fatal agricultural injuries; two fatal injuries were reported. Agricultural injuries were defined as events incurred as a result of performing, or being associated with, an activity related to the agricultural operation that resulted in one or more of the following: restriction from normal activities for 4 or more hours; loss of consciousness or awareness, or amnesia for any length of time; or use of professional health care.

Data collection

Computer‐assisted telephone interviews were conducted by NASS interviewers for each 6‐month period of each study year to ascertain injury incidence and relevant consequences. Case exposures were ascertained for the month prior to injury occurrence; control exposures were ascertained for a random 1‐month period within the study period, based on an algorithm of expected injury occurrence.16,17

Measures

Four work practice exposures were evaluated.

Performing work

A dichotomous variable (yes/no) based on parents' responses to the question, “During the {prior month} did {your child} work in any type of activity or do chores related to your operation?”

Number of chores

The summed number of the different types of agricultural chores each child performed in the previous month, out of a possible 18 chore types. Possible chore types included all chores performed by 10% or more of the children in the study: working with beef and dairy cattle (calving, feeding, cleaning, herding), swine, horses, and poultry; operating vehicles (tractor, car, truck, motor cycle, ATV, snowmobile, other large equipment); using hand and/or power tools; and working in storage structures or with agricultural chemicals.

Average hours worked per week

The hours per week children worked on their agricultural operations reflected weekly employment patterns: <11 h, 11–30 h, 31–40 h, 41–60 h, and more than 60 h.

Working early

Children performing tasks when younger than recommended were designated as working “early”. The NAGCAT age recommendations for task performance with intermittent supervision9 were used as the standard for developmentally appropriate work for most tasks. The minimum age for calving, working with bulls, small power tools, and handling chemicals was set at 16 years, based on their inclusion in the Hazardous Occupations Order for Agriculture (HOOA).13 The minimum age for operating motor vehicles was 15 years, based on state motor vehicle licensing requirements.

Differences between the age recommended for task performance and children's actual age were calculated as measures of the developmental gap between each task and children's physical, cognitive, and behavioral maturity. Task‐specific risk scores were summed for each child and divided by the number of chores performed. The averaged scores were grouped into seven categories: not working; performing age appropriate work; and working an average of 2 years, >2 to ⩽3 years, >3 to ⩽4 years, >4 to ⩽6 years, or >6 years younger than recommended.

Parent‐related covariates included averaged ages, mother's highest level of education, number of children in household, and hours per week worked on their agricultural operation. Child‐related covariates included age, gender, and self‐control and size for age.

Self‐control

Because existing instruments were too long to include as embedded scales, the self‐control items were based on items from widely used child behavior assessment instruments (the Parent Observation of Child Adaptation (POCA),18 Child Behavior Checklist,19 BASC Monitor for ADHD,20 and multidimensional personality scales21). The behavioral characteristics in children older than 5 years were summed. Parents responded to four‐point Likert scales, with options of (1) almost never through (4) almost always to rate whether a child: “paid attention”, “had good concentration”, “was cautious”, “worked hard”, “was easily distracted”, “broke rules”, “was impulsive”, and “acted without thinking” (the last four items were reverse scored). Chronbach's alpha = 0.78 was calculated for the self‐control scale, indicating high internal reliability based on the inter‐item correlation.

Size for age

Percentile values for height for age and body mass index (BMI) were generated, comparing each child against national measurements of children of the same age and gender.22 The height percentiles were grouped into “short” (⩽5th) and “not short” (>5th to 100); BMI percentiles were grouped into “underweight” (⩽5th), “normal” (>5th to 85th), “at risk of overweight” (>85th to 95th), and overweight (>95th to 100).23

Prior injuries indicated prior agricultural injuries experienced by the child or by household members, other than the child.

Data analysis

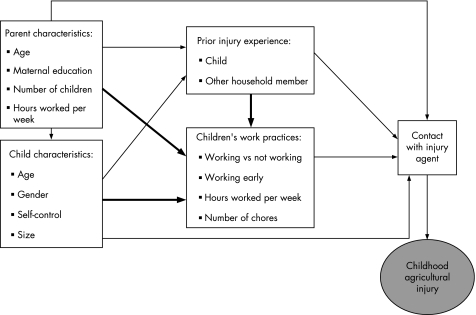

A causal model based on hypothesized associations between agricultural work practices, relevant covariates, and childhood agricultural injury served as the basis for data analysis (fig 1). Selection of covariates for statistical models were guided with directed acyclic graphs.24 Because work practice frequencies differed by year of participation, a year of participation indicator was included in all multivariate analyses to minimize variance and to adjust for factors represented by declines, between 1998 and 2001, in the rate of agricultural injuries to males aged 0–19 years and in the number of injuries to all youths living on US operations.4

Figure 1 Conceptual model: children's work practices and childhood agricultural injury. Bold line = effect of variable at arrow head is modified by the variable at the arrow tail. Note: year of participation (1999/2001) is included in all statistical models, but is not shown here.

The relationship of each exposure variable to the logit of the outcome was assessed for linearity. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), estimating the risk of agricultural injury and “performing agricultural work” were calculated for each exposure using multivariate logistic regression. Interaction terms were constructed for each work practice–covariate pair and tested for significance. Because this study is among the first to evaluate factors associated with children's work practices and injury, the results of both the statistical models estimating the main exposure effects and those estimating the effects of the interaction terms are presented. Multivariate linear regression was used to evaluate the association between injury work practices and child and parent characteristics.

Overall, 16 940 (53%) of the 32 000 agricultural operations sampled in the data collection years were identified as ineligible, based on the study's participation criteria. Of the 8810 (28%) operations identified as eligible, 7420 (84%) participated in the full study. Non‐response bias was controlled by inversely weighting responses by estimated probabilities of response,25 estimated as a function of household characteristics (state, type of operation, annual revenue by quintiles) from the U.S. Department of Agriculture's National Agricultural Statistics Service database. The unknown eligibility among non‐respondents was controlled by down‐weighting each sample member by the estimated probability of ineligibility among the respondents with the same characteristics.26

To examine the potential efficacy for reducing the risk of childhood agricultural injuries by raising the minimum age recommendations from 16 to 18 years, the minimum age of task performance was re‐set to 18 years, legal adulthood, for the chores included in the early measure, and the data were re‐analyzed to assess sensitivity to the original assumptions.27

Results

Participant and parent characteristics, based on case–control status, are available at http://enhs.umn.edu/riprc/riprc.html. As shown in Table 1, children performing chores 2–3 years younger than recommended were at increased risk of injury; 93% of these children were aged 12–13 years. When the minimum age for task performance was re‐set to 18 years, 12–13‐year‐olds still experienced the highest risk of injury (OR = 2.7, 95% CI = 1.3–5.4). However, an increase in injury risk was also found for 14–15‐year‐olds (1.7 (0.9–3.2)) and for 16–17‐year‐olds (1.5 (0.9–2.7)) who performed chores early. Before re‐setting the minimum age, the developmental ability of 16–17‐year‐olds had been equated to an adult's; thus, the potential risks incurred by those performing chores for which they were not developmentally ready could not be examined.

Table 1 Children's agricultural work practices: distribution and association with childhood agricultural injury (n = 2311).

| Child work practices | No. (%) of respondents | Odds ratio* (95% confidence interval) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case events (n = 425) | Controls (n = 1886) | ||

| Performed agricultural work | |||

| Did not work | 48 (11.8) | 745 (40.7) | Reference |

| Worked | 359 (88.2) | 1087 (59.3) | 3.9 (2.6 to 5.6) |

| Interaction term: performing work × children's age | Wald χ2 = 4.3, 1 d.f., p‐value = 0.04 | ||

| Work performed “early”† | |||

| Did not work | 48 (11.8) | 744 (40.7) | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.4) |

| Did not work early | 107 (26.3) | 407 (22.3) | Reference |

| Worked: 1 to ⩽2 years early | 66 (16.2) | 189 (10.3) | 1.1 (0.7 to 1.8) |

| Worked: >2 to ⩽3 years early | 51 (12.5) | 67 (3.7) | 2.6 (1.4 to 4.5) |

| Worked: >3 to ⩽4 years early | 33 (8.1) | 72 (3.9) | 1.4 (0.7 to 2.6) |

| Worked: >4 to ⩽6 years early | 46 (11.3) | 137 (7.5) | 0.9 (0.5 to 1.6) |

| Worked: >6 years early | 56 (13.8) | 213 (11.6) | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.4) |

| Interaction term: working early × household agricultural injuries | Wald χ2 = 16.5, 7 d.f., p‐value = 0.02 | ||

| Hours children worked on own operation | |||

| Did not work | 48 (11.8) | 745 (40.8) | 0.3 (0.2 to 0.4) |

| 1 to 10 | 163 (40.1) | 641 (35.1) | Reference |

| 11 to 30 | 140 (34.5) | 323 (17.7) | 1.6 (1.2 to 2.1) |

| 31 to 40 | 31 (7.6) | 49 (2.7) | 2.2 (1.3 to 3.7) |

| 41 to 60 | 15 (3.7) | 48 (2.6) | 1.0 (0.5 to 2.0) |

| 60+ | 9 (2.2) | 21 (1.1) | 1.4 (0.5 to 3.6) |

| Interaction term: hours children worked × number of siblings | Wald χ2 = 13.2, 6 d.f., p‐value = 0.04 | ||

| Number of types of chore | |||

| Did not work | 49 (12.0) | 775 (42.3) | 0.3 (0.2 to 0.4) |

| 1 chore | 45 (11.1) | 165 (9.0) | Reference |

| 2 chores | 30 (7.4) | 168 (9.2) | 0.6 (0.4 to 1.1) |

| 3 chores | 43 (10.6) | 129 (7.0) | 1.2 (0.7 to 2.0) |

| >4 to ⩽6 chores | 105 (25.8) | 359 (19.6) | 1.1 (0.7 to 1.7) |

| >7 to ⩽10 chores | 123 (30.2) | 200 (10.9) | 2.2 (1.3 to 3.5) |

| >10 chores | 12 (2.9) | 36 (2.0) | 1.0 (0.4 to 2.2) |

| Interaction term: number children's chores × hours parent's worked | Wald χ2 = 15.2, 7 d.f., p‐value = 0.03 | ||

*Separate multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed for each exposure and interaction product. The statistical models adjusted for: missing values, non‐response, year participated, age, gender, BMI, being short, self‐control, prior child injuries, prior injuries to household members, parents' ages, maternal education, children in household, hours per week parents worked.

†The difference between the child's actual age and the age recommended for task performance.

Children had an increased risk of injury if they performed agricultural work at all, worked 11–30 or 31–40 h per week, or performed seven to ten types of chore per month (Table 1). Significant interactions were observed for working early and experiencing prior agricultural injuries; number of hours children worked and number of siblings; number of chores children performed and hours parents worked; and performing agricultural work and children's age. The highest injury risks were seen for children: working 2–3 years “early” from households incurring one or six or more prior injuries; working 11–40 h per week from households with three or more siblings (OR11–30 h = 1.9, 95% CI = 1.01–3.4 and OR31–40 h = 5.3, 95% CI = 1.9–14.4); and performing three or more chores when parents worked 60 h or more per week (OR3–6 chores = 3.6, 95% CI = 0.97–12.9 and OR7+chores = 5.1, 95% CI = 1.2–22.3).

Boys, compared with girls, and 12–13‐year‐olds, compared with 16–19‐year‐olds, were at increased risk of injury (Table 2), even after adjusting for hours worked; additional linear regression results are located at http://enhs.umn.edu/riprc/riprc.html. Children aged 12–13 years compared to those aged 16–19 years, were more likely work at all and work early, but worked fewer hours, and performed fewer chores. Children who “almost never” or “sometimes” displayed self‐control worked less than children who “almost always” displayed self‐control; but those with the least self‐control were at higher risk of injury. Children's stature was not associated with injury but, compared to children of normal stature, shorter and underweight children worked less and worked fewer hours while children at risk of obesity worked more and performed more chores.

Table 2 Characteristics associated with childhood agricultural injury and agricultural work (results of multivariable logistic regression, n = 2311).

| Childhood agricultural injury** | Perform farm work (yes/no)** | |

|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Data collection year | ||

| 1999 respondents | Reference | Reference |

| 2001 respondents | 0.8 (0.6 to 0.9) | 0.8 (0.7 to 1.02) |

| Child characteristics | ||

| Gender | ||

| Female | Reference | Reference |

| Male | 1.9 (1.5 to 2.3) | 2.5 (2.0 to 3.0) |

| Age groups* | ||

| 0–5 | 0.5 (0.3 to 0.7) | 0.1 (0.6 to 0.1) |

| 6–9 | 0.6 (0.4 to 0.9) | 0.7 (0.5 to .99) |

| 10–11 | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.1) | 1.3 (0.9 to 1.9) |

| 12–13 | 1.8 (1.3 to 2.5) | 1.5 (1.1 to 2.2) |

| 14–15 | 1.2 (0.8 to 1.7) | 1.7 (1.2 to 2.5) |

| 16–19 | Reference | Reference |

| Self‐control† | ||

| Almost never | 1.7 (0.99 to 3.1) | 0.5 (0.3 to 0.8) |

| Sometimes | 0.5 (0.2 to 0.9) | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.3) |

| Often | 1.3 (0.9 to 1.7) | 1.1 (0.8 to 1.5) |

| Almost always | Reference | Reference |

| Height for age (percentile groups)‡ | ||

| Short (<5) | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.2) | 0.6 (0.4 to 0.8) |

| Not short (5–100) | Reference | Reference |

| Body mass index for age (percentile groups)§ | ||

| Underweight (0 to <5) | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.2) | 0.6 (0.4 to 0.9) |

| Normal (5 to <85) | Reference | Reference |

| Overweight risk (85 to <95) | 1.3 (0.9 to 1.7) | 1.3 (0.95 to 1.7) |

| Overweight (95 to 100) | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.2) | 0.8 (0.6 to 1.04) |

| Prior child injuries | ||

| No prior injury | Reference | Reference |

| 1 | 1.7 (1.2 to 2.4) | 2.8 (1.8 to 4.5) |

| 2 | 7.2 (3.7 to 13.9) | 5.0 (1.1 to 21.8) |

| 3 to 4 | 4.7 (2.0 to 11.5) | 1.8 (0.4 to 7.0) |

| >5 | 3.3 (1.1 to 10.2) | 2.1 (0.2 to 20.1) |

| Parents' characteristics | ||

| Parents' average ages (5‐year increments)* | 0.9 (0.8 to 0.98) | 1.1 (1.01 to 1.2) |

| Maternal educational status¶ | ||

| Not high school graduate | 0.8 (0.3 to 2.0) | 0.5 (0.2 to 1.1) |

| High school graduate | Reference | Reference |

| Technical school | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.4) | 1.04 (0.8 to 1.4) |

| College | 1.2 (0.9 to 1.5) | 0.7 (0.6 to 0.9) |

| Number of children in household* | 1.4 (1.2 to 1.5) | 1.1 (1.01 to 1.2) |

| Hours per week parents worked on own operation* | ||

| 0 | – | 0.1 (0.02 to 0.6) |

| 1 to 10 | 0.3 (0.2 to 0.6) | 0.3 (0.2 to 0.4) |

| 11 to 30 | 0.6 (0.5 to 0.8) | 0.7 (0.5 to 0.9) |

| 31 to 40 | 0.8 (0.6 to 1.1) | 0.5 (0.4 to 0.7) |

| 41 to 60 | Reference | Reference |

| 60+ | 1.6 (1.1 to 2.3) | 1.5 (0.96 to 2.2) |

| Prior injuries to members of the household | ||

| No prior injury | Reference | Reference |

| 1 | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.4) | 1.4 (1.06 to 1.9) |

| 2 | 1.4 (0.9 to 2.0) | 1.3 (0.9 to 1.8) |

| 3 to 5 | 2.7 (1.9 to 3.7) | 1.9 (1.4 to 2.7) |

| >6 | 3.5 (2.4 to 4.9) | 1.6 (1.1 to 2.3) |

*Less than 5% of the data were missing.

†Data on self‐control were missing for 12.5% of the cases and 19.1% of the controls.

‡Data on size for age were missing for 4.5% of the cases and 8.5% of the controls.

§Data on body mass index for age were missing for 3.8% of the cases and 8.3% of the controls.

¶Data on maternal educational were missing for 3.8% of the cases and 6.5% of the controls.

**Separate multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed for each dependent variable; the statistical models are specified as follows:

Year of data collection – adjusted for: missing values, non‐response, age, gender.

Gender – adjusted for: missing values, non‐response, year participated, age, parents' ages, maternal education, children in household, hours per week parents worked.

Child's age – adjusted for: missing values, non‐response, year participated, gender, parents' ages, maternal education, children in household, hours per week parents worked.

Self‐control – adjusted for: missing values, non‐response, year participated, gender, age, parents' ages, maternal education, children in household, hours per week parents worked.

Short‐for‐age – adjusted for: missing values, non‐response, year participated, gender, age, parents' ages, maternal education, children in household, hours per week parents worked.

Body‐mass index (BMI) for age – adjusted for: missing values, non‐response, year participated, gender, age, parents' ages, maternal education, children in household, hours per week, parents worked.

Prior child injuries – adjusted for: missing values, non‐response, year participated, gender, age, BMI, short, self‐control, parents' age, maternal education, children in household, hours per week parents worked, prior injuries to household members.

Parents' ages – adjusted for: non‐response, year participated.

Maternal education – adjusted for: missing values, non‐response, year participated, parents' ages, hours per week parents worked, children in household.

Children in household – adjusted for: missing values, non‐response, year participated, parents' ages, maternal education, hours per week parents worked.

Hours per week head of householdworked – adjusted for: missing values, non‐response, year participated, parents' ages, maternal education, children in household.

Prior injuries to householdmembers – adjusted for: missing values, non‐response, year participated, age, gender, BMI, short, self‐control, prior child injuries, parents' ages, maternal education, children in household, hours per week parents worked.

Having prior agricultural injuries, compared to having had no injuries, increased the risk of injury and the likelihood of performing farm work. Each additional sibling increased the risk of injury and the likelihood of working early or at all. Compared with children whose parents worked full‐time (40–60 h per week), children whose parents worked 60 or more hours per week were at higher risk of injury; children whose parents worked less than full‐time worked less and were at lower risk of injury. As parents' average age increased, children were at decreased risk of injury and less likely to work early but more likely to work at all, work more hours, and perform more chores.

Discussion

We observed an increased risk for injury among children performing agricultural tasks at ages younger than recommended. These findings were consistent with the reduced risk found for NAGCAT dissemination on preventable injuries in a randomized controlled trial28 and with descriptive analyses suggesting that age guideline adherence was potentially preventive for injuries.29,30,31

Our results support the assumption that performing age‐appropriate tasks prevents injury. However, an increased risk of injury was found for 16–17‐year‐olds (compared to 18–19‐year‐olds) when performing tasks that were developmentally appropriate for an adult. Additionally, RRIS‐II respondents of all ages performed many tasks prohibited in the Hazardous Occupations Order for Agriculture (HOOA),13 (eg. calving, handling chemicals, working with bulls and small power tools). Taken together, these findings justify further examination of whether current age guidelines are sufficiently conservative and complete.

Associations between child and parent characteristics and injury and work practices were assessed to generate future research hypotheses and to identify potential targets for intervention. Boys, compared with girls, and 12–13‐year‐olds, compared with 16–19‐year‐olds, were at higher risk of injury regardless of hours worked. The association between gender and agricultural injury is well established in the literature,32,33,34,35 although it may be partially explained by differential hours worked15 or the nature of the assigned tasks. Potential age‐related mechanisms include the absence of supportive parenting during periods of vulnerability,36 parental overestimation of children's abilities, or the inclination of young adolescents to take risks.

Behavior and stature may influence adult perceptions about children's competence and readiness to work. Children who almost never exhibited self‐control had a higher risk of injury and a lower risk of working, suggesting a potential behavioral pathway related to injury (via poor self‐control) and a possibility that parents respond to child behaviors by assigning less work. Being shorter and underweight reduced the likelihood of performing work and being injured. Parents potentially estimated the developmental readiness of smaller children more conservatively, thus, assigning them less risky tasks or supervising them more.

Children of older parents had a lower risk of injury and working early, but were more likely to work at all, work more hours, and perform more chores. That being an older parent is potentially associated with protective parenting practices, such as assigning developmentally appropriate work, warrants further examination. The risk of injury for the number of chores children performed varied by how much parents worked on the operation. For children with parents working more than 60 h per week, performing three or more chores was associated with higher injury risk, possibly due to decreased supervision or increased hazardousness of chores assigned. That parents' less‐than‐full‐time work was associated with decreased injury risk is potentially explained by children's exposure to agricultural hazards being influenced by off‐farm child care options37 or reduced exposure to agricultural hazards.

Although children with additional siblings were at higher risk of injury, the risk was highest for children who worked 11–40 h per week with three or more siblings. This may be partially explained by the association between parents' and children's work hours. Children who work more may need more supervision, while parents who work more may be more distracted or may assign siblings to monitor younger children. Previous associations between larger families and exposure to hazardous agricultural tasks6 and injury38 were linked to inadequate supervision.

The risk of injury for working early varied by the number of prior injuries among household members other than the child. The highest risks were seen for children working 2–3 years “early” in households that experienced six or more prior injuries. This is potentially explained by shared economic pressures or hazardous environments, intra‐familial risk‐taking behaviors, or children assuming hazardous tasks when family members are injured.

Limitations of this analysis include using self‐reported injury and exposure data collected during the same interview. Recall bias was minimized by limiting recall of injury events to the previous 6 months15,39 and recall of exposures to a 1‐month period within the previous year.40 The results were also subject to the following assumptions. The “early” measure represented the “averaged” match between a child's development and the developmental requirements of the tasks they performed. The measure's limitations include that it was based on age, a crude indicator of children's “developmental readiness” and assumed supervision equivalent to being checked every 10–30 min. Lastly, the measure averaged potentially important task‐specific risks; although the small numbers of task‐specific cases precluded stratified analyses, this would be an important focus of future research.

Conclusions

This study is the first to use population‐based data to evaluate the risk of childhood agricultural injury associated with performing developmentally inappropriate chores. Although positive associations between injury and work practices were expected, our study found an increased risk of injury for levels of work typically considered “safe“. Results underscore the importance of a developmental approach for understanding mechanisms of childhood agricultural injury and suggest that the efficacy of age restrictions for preventing the occurrence of childhood agricultural injuries warrants further evaluation.

Implications for prevention

This study found increased risks of agricultural injury for levels of agricultural work typically considered “safe” for children. Of note, an increased risk of injury from performing developmentally inappropriate agricultural chores was observed for 12–13‐year‐olds; this age group may be an appropriate target for injury prevention programs. Although prohibited in the Hazardous Occupations Order for Agriculture (HOOA), children performed many tasks such as calving, handling chemicals, working with bulls, and using small power tools. These activities should be evaluated for future inclusion in voluntary agricultural work guidelines.

Key points

This study is the first to use population‐based data to evaluate the risk of childhood agricultural injury associated with performing developmentally inappropriate chores.

Increased risks of agricultural injury were found for levels of agricultural work typically considered “safe” for children.

An increased risk of injury from performing developmentally inappropriate agricultural chores was observed for 12–13‐year‐olds.

Although prohibited in the Hazardous Occupations Order for Agriculture (HOOA), children performed many tasks such as calving, handling chemicals, working with bulls, and using small power tools.

Results underscore the importance of a developmental approach for understanding mechanisms of childhood agricultural injury and suggest that the classifications of age restrictions for preventing the occurrence of childhood agricultural injuries warrant further evaluation.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr Kathleen Carlson for her thoughtful comments. Most importantly, without the interest of, and commitments made by, the households selected in the five‐state region, this study would have not been possible. The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or other associated entities.

Footnotes

Support for this study and for the Regional Rural Injury Study‐II was provided, in part, by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Department of Health and Human Services (RO1 CCR514375; R01 OHO4270); the National Occupational Research Agenda Program (NIOSH T42/CCT510‐422), Midwest Center for Occupational Health and Safety, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA; and the Regional Injury Prevention Research Center, Division of Environmental Health Sciences, School of Public Health, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA. Collaborating organizations included the U.S. Department of Agriculture's National Agricultural Statistics Service offices in the five participating states of Minnesota, Wisconsin, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Nebraska, and the respective Agricultural Extension Services and state representatives.

Competing interests: None

References

- 1.Perry M J. Children's agricultural health: Traumatic injuries and hazardous inorganic exposures. J Rural Health 200319269–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Safety Council (NSC) Injury Facts ® 2005–2006. Chicago: NSC, 2006

- 3.Goldcamp M, Hendricks K J, Myers J R. Farm fatalities to youth 1995–2000: a comparison by age groups. J Safety Res 200435151–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hendricks K J, Layne L A, Goldcamp E M.et al A comparison of injuries among youth living on farms in the U.S., 1998–2001 Presented at the National Institute for Farm Safety (NIFS) 2004 Annual Conference, Keystone, CO, 20–24 June 2004J Agromed 20051019–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elkind P D. Correspondence between knowledge, attitudes, and behavior in farm health and safety practices. J Safety Res 199324171–179. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee B, Jenkins L S, Westaby J D. Factors influencing exposure of children to major hazards on family farms. J Rural Health 199713206–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marlenga B, Pickett W, Berg R L. Assignment of work involving farm tractors to children on North American farms. Am J Ind Med 20014015–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marlenga B, Pickett W, Berg R L. Agricultural work activities reported for children and youth on 498 North American farms. J Agric Safety Health 20017241–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee B, Marlenga B. eds. Professional resource manual: North American guidelines for children's agricultural tasks. Marshfield, WI: Marshfield Clinic 1999

- 10.Kidd P, Scharf T, Veazie M. Linking stress and injury in the farming environment: a secondary analysis of qualitative data. Health Educ Q 199623224–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pickett W, Marlenga B, Berg R L. Parental knowledge of child development and the assignment of tractor work to children. Pediatrics 200311211–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zentner J, Berg R L, Pickett W.et al Do parent's perceptions of risks protect children engaged in farm work? Prev Med 200540860–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.U S. Department of Labor (USDOL). Child labor requirements in agriculture under the Fair Labor Standards Act. Child Labor Bulletin No. 102. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor, Employment Standards Administration, Wage and Hour Division. WH Publication 1295. U.S. Government Printing Office: 1989‐241‐406/06551 1984

- 14.Kelsey T W. The agrarian myth and policy responses to farm safety. Am J Public Health 1994841171–1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerberich S G, Alexander B H, Church T R.et alRegional rural injury study – II, Phase 2: Agricultural injury surveillance. Technical report RO1/OHO4270, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Minneapolis: Regional Injury Prevention Center, University of Minnesota, 2004

- 16.Gerberich S G, Gibson R W, French L R.et alEtiology and consequences of injuries among children in farm households: A regional rural injury study. Technical report RO1 CCR514375, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Minneapolis: Regional Injury Prevention Center, University of Minnesota, 2003

- 17.Gerberich S G, Gibson R W, French L R.et alThe regional rural injury study‐I (RRIS‐I): A population‐based effort A Report to the Centers for Disease Control, NTIS# PB94‐134848. Minneapolis: Regional Injury Prevention Research Center, University of Minnesota 1993

- 18.Kellam S, Branch J, Agrawal K.et alMental health and going to school: The Woodlawn program of assessment, early intervention, and evaluation Chicago: University of Chicago Press 1975

- 19.Achenbach T M, Edelbroch C S.Manual for the child behavior checklist and revised child behavior profile. Burlington, VT: University Associates in Psychiatry, 1991

- 20.Kamphaus R W, Reynolds C R.BASC monitor for ADHD. Circle Pines, MN: AGS Publishing, 1998

- 21.Tellegen A.Brief manual for the differential personality questionnaire. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, 1982

- 22.National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) 2000 CDC growth charts: United States. www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/major/nhanes/growthcharts/ (accessed 20 May 2005)

- 23.Centers for Disease Control (CDCP) BMI – body mass index: BMI for children and teens. 2005. www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpa/bmi/bmi‐for‐age.htm (accessed 28 June 2005)

- 24.Greenland S, Pearl J, Robins J M. Causal diagrams for epidemiologic research. Epidemiology 19991037–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horvitz D G, Thompson D J. A generalization of sampling without replacement from a finite universe. J Am Stat Assoc 195247663–685. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mongin S J.Adjustments for nonresponse in the presence of unknown eligibility. Health Studies Research Report. Division of Environmental and Occupational Health, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis 2001. www1. umn. edu/eoh (accessed 1 March 2003)

- 27.Rothman K J, Greenland S.Modern epidemiology. 2nd edn. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1998

- 28.Gadomski A, Ackerman S, Burdick P.et al Efficacy of the North American Guidelines for Children's Agricultural Tasks in reducing childhood agricultural injuries. Am J Public Health. [Epub 28 February 2006. doi 10.2105/AJPH.2003.035428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Marlenga B, Brison J R, Berg R L.et al Evaluation of the North American Guidelines for Children's Agricultural Tasks using a case series of injuries. Inj Prev 200410350–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mason C, Earle‐Richardson G. New York state child agricultural injuries: how often is maturity a potential contributing factor? Am J Ind Med Suppl 2002236–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marlenga B, Berg R L, Linnemann J G.et al Changing the child labor laws for agriculture: impact on injury. AJPH 200797276–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bancej C, Arbuckle T. Injuries in Ontario farm children: a population‐based study. Inj Prev 20006135–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dimich‐Ward H, Guernsey J R, Pickett W.et al Gender differences in the occurrence of farm related injuries. Occup Environ Med 20046152–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hard D, Myers J, Snyder K.et al Youth workers at risk when working in agricultural production. Am J Ind Med Suppl 1999131–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) 1998 Childhood agricultural injuries. Agricultural Statistics Board, U. S. Department of Agriculture 1999810–99. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Masten A S. Competence, resilience and development in adolescence: Clues for prevention science. In: Romer D, Walker E, eds. Adolescent psychopathology and the developing brain: integrating brain and prevention science. New York: Oxford University Press, 200731–52.

- 37.Pryor S K, Caruth A K, McCoy C A. Children's injuries in agriculture related events: The effect of supervision on the injury experience. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs 200225189–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwartz S, Eidelman A I, Zeidan A.et al Childhood accidents: the relationship of family size to incidence, supervision, and rapidity of seeking medical care. Isr Med Assoc J 20057558–563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Braun B L, Gerberich S G, Sidney S. Injury reports: utility of self report in retrospective identification in the U.S.A. J Epidemiol Community Health 199449604–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee S S, Gerberich S G, Waller L A.et al A case–control study of work‐related assault injuries among nurses. Epidemiology 199910685–691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]