Germany: tobacco industry still dictates policy

All articles written by David Simpson unless otherwise attributed. Ideas and items for News Analysis should be sent to: d.simpson@iath.org

The majority of the German public (over 60% in independent surveys) who support comprehensive smoke‐free legislation will have been disappointed by the recent, farcical turn of events in Germany. For the tobacco industry, used to dictating tobacco control policy in Germany, December was surely business as usual.

Triggered by the success of smoke‐free legislation in other European countries and recent estimates that over 3300 deaths per year can be attributed to secondhand smoke in Germany, last September, two groups of parliamentarians made independent proposals for comprehensive national smoke‐free legislation. Both gained large support in parliament, and the grand coalition government established a working group to craft a comprehensive law. While smoking restrictions in schools, public buildings and hospitals were largely accepted, those in restaurants, pubs and bars were highly controversial, stimulating a media circus and strong opposition from the Verband der Cigarettenindustrie (VdC), the tobacco industry's trade organisation in Germany.

VdC representatives engaged in a high‐profile lobbying campaign, contacting politicians directly and appearing on numerous TV talk shows to promote the usual tobacco industry arguments about freedom and choice. Moreover, according to media reports, the tobacco industry influenced the working group's draft legislation to such an extent that the grand coalition government (whose federal ministries of health and consumer protection were both represented on the group) was labelled an industry “puppet”. Not only was the text severely weakened, with pubs and bars totally excluded and restaurants partially exempted but, text citing verbatim a VdC position paper reportedly found its way into the draft.

After heated negotiations, on 1 December, the working group presented plans for national smoke‐free legislation. Although the proposed ban would hardly have been effective—smoking would still be allowed in bars and pubs and in enclosed smoking rooms in restaurants, and enforcement was weak—the fact that national tobacco control legislation was being contemplated was itself exceptional for Germany, which has long favoured industry self‐regulation.

The surprise was perhaps even greater given that one such ineffective voluntary agreement had only recently been reached between the government and the German hotel and restaurant association (DEHOGA). Furthermore, Philip Morris, with impeccable timing, had just co‐sponsored the annual convention of the Christian Democratic Union, the political party of the Chancellor, Angela Merkel (as it does for most other political parties).

Just a few days later, however, government leaders expressed concern that national legislation to protect the public from secondhand smoke was unconstitutional. The federal health ministry fought strongly for national legislation, arguing that constitutional law allows the federal government to take measures against public health risks. But the federal ministries of justice and internal affairs countered that the law required such health risks to represent an immediate danger to the public and thus did not cover involuntary smoking. On this subject, the media repeatedly quoted one prominent opponent of the legislation: Rupert Scholz, university professor of law, former minister of defence and a member of parliament.

What was not mentioned, however, was the apparent longstanding link between Scholz and the German tobacco industry. According to internal tobacco documents released through litigations in the USA, in the early 1990s, Scholz was the vice‐chairman of VERUM, a foundation that funds research (its name is a shortened form of its long title in German, meaning a foundation for behaviour and the environment). VERUM was established and financed by the tobacco industry and Scholz still serves on its board. Moreover, in 2002, the German news magazine Stern reported that Scholz received 50 000 Deutsche Marks (US$33 000) in 1994 from the VdC for consultancy services. It is interesting to speculate about the extent to which Scholz used his influence with the federal ministries of justice and internal affairs, and whether he declared any conflict of interest in his dealings with them.

These events demonstrate that the tobacco industry continues to enjoy a staggering amount of influence in Germany. In contrast with other high income countries, the tobacco industry remains a credible partner and continues to enjoy close links to German politicians. Furthermore, the failed effort shows a recurring intragovernmental conflict between the health ministry and other federal ministries when it comes to tobacco control. In Germany, with health seen as low on the political agenda, the health ministry always loses.

Thilo Grüning

Anna Gilmore

London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, London, UK; t@gzzz.freeserve.co.uk; anna.gilmore@lshtm.ac.uk

Australia: British American Tobacco “addresses” youth smoking

British American Tobacco Australia (BATA), whose website states with anodyne irony that it “is helping to build effective programmes to address youth smoking”, has given us a further clue about what it might mean by “address”. The company has launched a range of twin‐compartment Dunhill Distinct “wallet” packs.

Once out of the cellophane, the pack (see figure) folds apart. Separated by a thoughtfully perforated edge, it is ready to tear into two iPod‐sized packs, one with 13 cigarettes and another with 7. Public health groups branded them “kiddie packs”, designed to appeal to price‐sensitive children who can split the cost with their school lunch money and then split the pack as they step out of the shop.

Australia: BAT's Dunhill pack split into its two sections.

Packs in Australia must contain a minimum of 20 cigarettes to deter children's purchasing. It must never have crossed BATA's mind that their nifty new tear‐in‐half packs might be a great way to beat the price barrier and provide two easily concealable packs for intrepid young smokers.

But someone in the company might have a lot of egg on their visage. Once the twin pack is torn in half, the larger section is without the mandatory pictorial warning (such as a fetching picture of a gangrenous foot) arguably breaching the Trade Practices Act. Complaints from health groups to Australia's regulator, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC), in November saw the Federal Court of Australia uphold an injunction sought by the ACCC that BATA should stop selling the packs. With the packs having to be removed from shops, BATA will be back in court in February 2007, potentially facing a maximum fine of over A$1 million, equivalent to US$789 000, and a criminal record. Should this happen, such a record will not be lost as an extra descriptor for Australia's largest tobacco company.

Although BATA's website drips with public relations saccharine about the company's youth smoking prevention programmes, in 2002–3, the value of tobacco sales to the Australian youth market was A$124.7 million (US$98.4 million), with A$18.7 million (US$77.6 million) going to manufacturers such as BAT. The companies keep the lot.

An internal BATA training DVD leaked to me a few years back showed senior executives jawing about how the international parent company saw its Australian operation as a global training ground for developing “a different skill set” in how to operate in the “darkest markets” on earth (Australia and Canada being named as the very darkest), where all tobacco advertising is banned. Strategically labelled “limited edition”, the Dunhill Distinct venture looks in every way like a limits‐testing exercise to see whether the ACCC and the courts would bite. If criminal prosecutions follow, they may get more than they bargained for.

Simon Chapman

sc@med.usyd.edu.au

Hong Kong, China: bad atmosphere for public health

After deliberations lasting no less than 6 years, the government of the special administrative region of Hong Kong finally announced new tobacco control measures last October. After such a long wait and in view of Hong Kong's previous record as a public health leader in the region, there was bound to be disappointment at anything less than a model package. Unfortunately, several strange clauses found their way into the final law, and as the fifth annual conference of the International Society for the Prevention of Tobacco Induced Disease (ISPTID‐http://www.hku.hk/ptid/) convened in Hong Kong a month later, the new measures came in for intense discussion by experts from around the world.

As previously reported in these pages, individuals with tobacco industry links are to be found embedded in many important institutions in Hong Kong, and it often seems that business interests dominate even when life and death issues are debated by local politicians (Tobacco Control 2005;14:151–2; and 2003;12:10–11). Some major loopholes in what could and should have been an industry‐proof policy for Hong Kong, and a model for the region, have done nothing to dispel this impression.

First, brand‐stretching promotions are to continue, allowing the sort of advertisements that greet international visitors as soon as they arrive at Hong Kong airport. Having fought their way from Hong Kong being an adventure playground for young tobacco advertisers in the 1980s, to a near promotion‐free zone, health experts were bitterly disappointed by this omission. They spent years explaining to politicians that tobacco companies do not spend vast sums of their shareholders' money advertising non‐tobacco products with cigarette brand names unless it benefits cigarette sales. Yet, in this business‐dominated region, even business‐related arguments such as this failed to be heard against the constant black noise of tobacco industry propaganda.

Hong Kong: how outdoor advertising used to be—public health workers fear the return of massive iconic advertisements now that the government has decided to allow continued cigarette brand‐stretching promotions.

Second, and probably generating even more adverse comment in the media, was the exception whereby bars and certain other leisure venues, such as massage establishments and mah jong parlours, could register to continue allowing smoking until 1 July 2009. Apart from seeing this as a licence to poison hospitality industry workers for another 2½ years, creating a messy legal quagmire on a now unequal playing field, public health workers feel certain that the tobacco industry will use the exemption period to lobby for it to be made permanent. Ominously, as if pointing to the door on which the industry should push, the government said it will study the feasibility of smoking rooms in restaurants and entertainment venues. It is hardly as if this has not been studied around the world for years, always with the same conclusion, provided that the studies were not funded by tobacco interests.

Interestingly, another related public health story dominated local media throughout the ISPTID conference: mounting concern about air quality. Thousands of factories across the border in China belch out toxic fumes, with much of the pollution drifting over Hong Kong. The government has continually tried to reassure the public, while medical researchers publish data showing increasing respiratory problems in children and other adverse health consequences.

It remains to be seen how receptive to health arguments about air quality the Minister for Environment, Transport and Works, Sarah Liao Sau‐tung, turns out to be. In 1990, she obtained substantial funding to study air quality in Hong Kong; but the funding was from Philip Morris, via the largely tobacco‐funded Centre for Indoor Air Research. However, even if business interests and arguments impress her more than health statistics, there is little hope of an early solution. Observers say that the government's inaction is not so much a fear of upsetting the mainland, as the fact that so many of the culprit factories burning low‐grade fuels are owned by Hong Kong businesses.

Hong Kong: a Marlboro clothing advertisement greets passengers arriving at Hong Kong's Chek Lap Kok international airport.

So perhaps the solution to environmental problems lies with other sectors of the business community. As press coverage about air pollution continued to grow, the international financial management and advice company Merrill Lynch recommended investors to sell Hong Kong property and buy Singaporean instead because of Hong Kong's poor air quality. Those who thought that this might be treated more seriously than health arguments were again disappointed. It was rubbished by the government, which stated that life expectancy in Hong Kong was one of the world's highest, and claimed it was the most environmentally friendly place for executives. There was no mention, though, of the health of the executives' workers, or the workers' families. So while many fathers in the hospitality industry will continue to work in smoke‐filled bars, their children will continue to breathe heavily polluted air, while being brainwashed into associating cigarette brand names with the good things in life.

USA: alcohol control movement follows FCTC lead

The American Public Health Association (APHA), at its November annual meeting in Boston, adopted a strong policy statement calling for an international alcohol treaty modelled on the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC). Founded in 1872, the APHA is the oldest, largest and most diverse organisation of public health professionals in the world.

Drawing heavily on the experience of the tobacco control movement, the APHA is urging the World Health Organization to adopt a Framework Convention on Alcohol Control (FCAC), akin to the FCTC adopted in 2003. APHA believes that an FCAC could help thwart the expansion of alcohol markets, strengthen national and local regulation of alcohol, and help reduce the harmful consumption of alcoholic beverages.

Dr Georges C Benjamin, executive director of APHA, says that the global burden of disease for alcohol is approaching that of tobacco, and the current international climate favours such a treaty. However, the alcohol control movement is keenly aware of the challenges confronting the FCTC, the need for strong enforcement, the continuing attempts of corporate involvement in national and local policy development, and the threats presented by global trade agreements. By learning from the tobacco movement, a framework convention on alcohol would help strengthen the hand of countries in setting policies that protect human health. It may take years of strong advocacy before an alcohol convention becomes a reality, but calls for it by the World Medical Association and now the APHA are important steps.

Don Zeigler

American Medical Association; donald.zeigler@ama‐assn.org

UK: pulling the polonium ad

As news that Russian former secret agent Alexander Litvinenko had been poisoned with polonium 210 swept round the world in November, many great minds in public health thought alike. Why not build on publicity about this dangerous element to tell smokers that polonium 210 is one of the many and various poisons they inhale with every puff of their cigarettes?

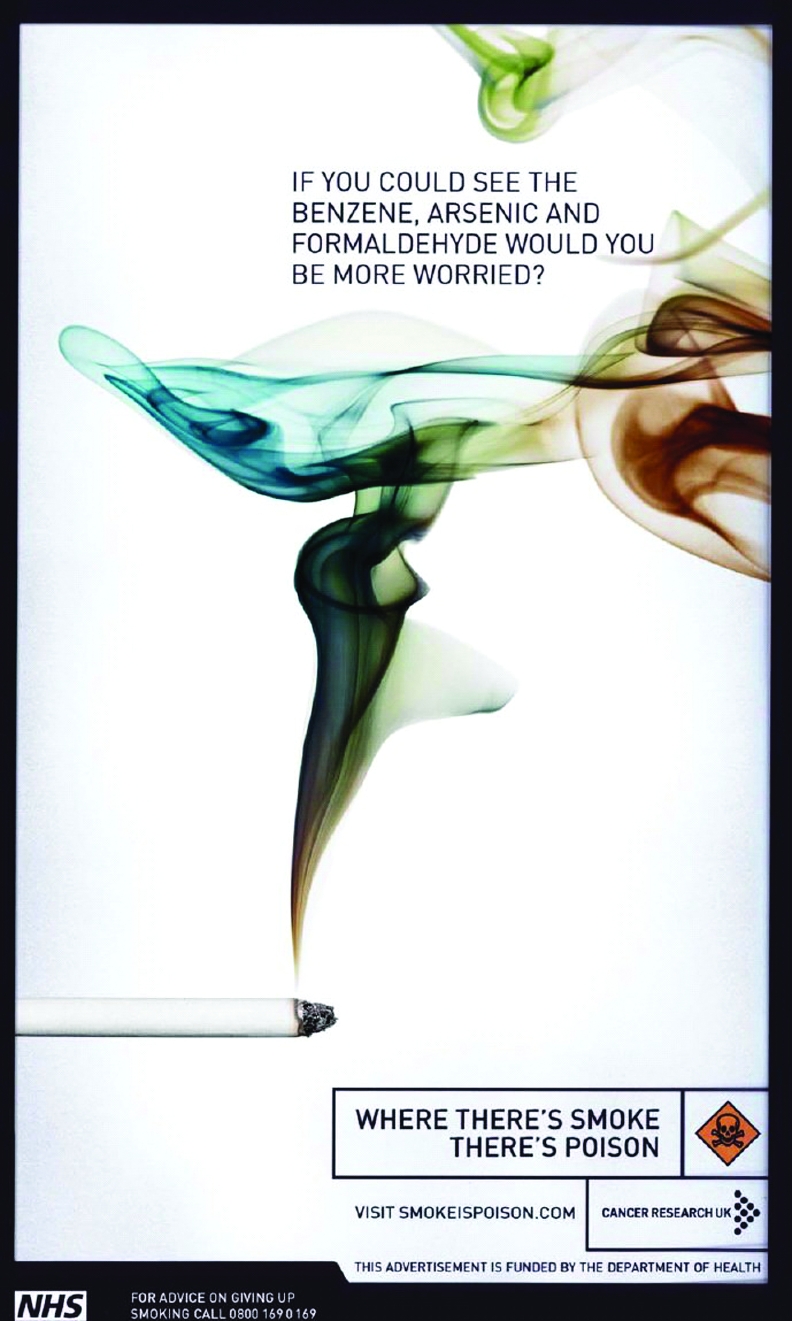

As it happened, Cancer Research UK, as part of a health promotion partnership with the British government, had just been working on a mass media campaign about tobacco featuring six chemicals that most smokers have heard of, and would rate as poisons, but may not know to be present in tobacco smoke. The idea of the radio and television advertisements, and small but high visibility posters, was to trigger a move towards giving up smoking, or at least help smokers to the first stage of the cessation loop. One of the poisons was polonium 210, with smokers being informed, for example, that a study had found that someone smoking one and half packs a day receives the equivalent amount of radiation as someone having 300 chest x rays a year. The other poisons featured in the series were arsenic, benzene, cadmium, formaldehyde and hydrogen cyanide.

UK: one of the new advertisements about chemicals in tobacco, run by Cancer Research UK.

Just as the advertisements were coming up for launch, the Department of Health decided to pull the one on polonium, at least temporarily, to spare the feelings of the murdered man's family. Some health agencies criticised the move as a sign of weakness, while others supported it by warning that its immediate airing would have led to panic‐stricken smokers jamming cessation telephone lines, an argument necessarily based on conjecture rather than on comparable experience elsewhere.

Whatever would have been the outcome, all sides seem to think that the polonium link should and probably will in some form be used later. If so, it remains to be seen whether smokers' residual awareness of polonium 210 well after the peak of the Litvinenko story will be sufficient to result in a greater effect in leading them towards cessation than publicity about the other chemicals, and then only if it is properly evaluated. Whether the delay in airing the polonium film has wasted what could have been a significantly greater prompting effect while the story was hot will never be known.

Brazil: tin cigarette cases as a marketing strategy

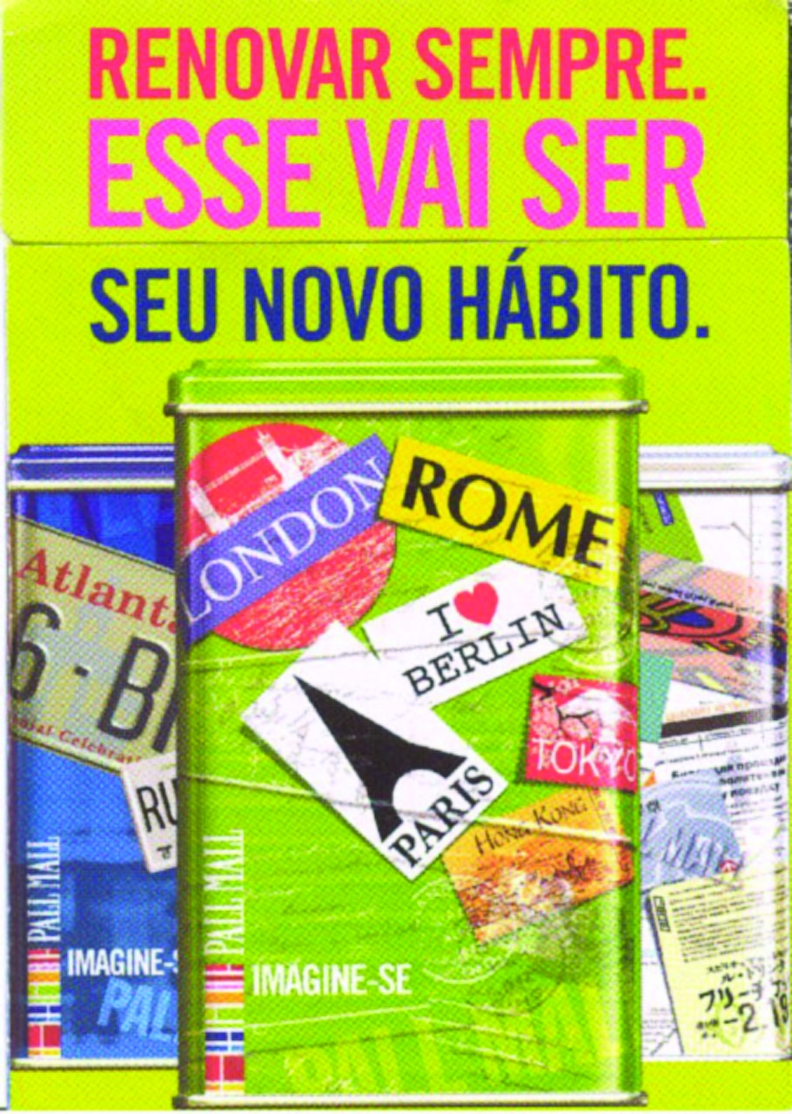

Brazilian legislation limits tobacco marketing to the point of sale. Nevertheless, tobacco companies are constantly devising new marketing strategies to maintain and increase market share and sales. One of the latest of such strategies by Philip Morris took place recently after in Brazil in Rio de Janeiro. To stimulate sales of its Pall Mall Blue brand (the one with the highest machine measured tar content), the company issued a “Collector's” cigarette pack carrier in the form of a metal box. While a pack of Pall Mall sells for R$2.25 (approximately US$1.05), for an additional R$2.25, the consumer could buy the can. The outside was printed with car license plates from cities around the world, together with the words, “Imagine yourself Pall Mall.”

Brazil: special Pall Mall “collector” pack tins proved highly popular with fashion‐conscious young smokers.

The cans carried all the mandatory health warnings. Inside, there was a triple‐section folded brochure. The front page states, “Renew Always. This will be your new habit.” In the middle, the title stated, “Renew Always. This is PallM Pac's commitment”, with text explaining that the new pack was more than just a pack, it was “a new way to reach you”. The back of the pamphlet asked, “How do you want to try the Pall Mall quality? Just choose”, with an accompanying photo of the three Pall Mall types: Blue, Orange and Silver.

The tin cans became hard to find in all retail outlets, mostly convenience stores in fuel filling stations, where large numbers of young people congregate, and at news stands. The design clearly appealed to a young crowd, and fitted within tobacco companies' continued attempts to target young people, especially those who want to emulate young adults' lifestyle choices.

LetÍcia Casado

National Cancer Institute, Ministry of Health, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; leticiac@inca.gov.br

UK: Scotland the brave

Among the success stories of recent years are the total public smoking bans adopted in Europe. And one of the most gratifying aspects has been the speed with which both the workforce newly protected by the ban and the general population in the countries concerned have embraced the benefits of being able to live and work in totally smoke‐free environments.

In Scotland, which went smoke‐free at the end of last March, more than nine out of 10 bar staff said that their workplaces were healthier in an opinion poll commissioned by Cancer Research UK just 6 months after the ban, with almost eight out of 10 of believing that the legislation would benefit their health in the long term. Even smoking bar workers were overwhelmingly positive about the health effects of the new law, with 89% reporting that their work environment was healthier because of it, and 69% believing that it would benefit their health in the long term. Interestingly, more young people than older people thought that the ban was benefiting their health.

UK: a stubbed‐out cigarette in the shape of Scotland celebrates the successful Scottish workplace‐smoking ban.

Public health workers in Scotland believe that the success of the Scottish ban could lead to further progress in other areas. It was led from the top, following decisions taken by the still relatively new, devolved Scottish parliament. The fact that they did it well ahead of England, which follows suit in July, has not been lost on Scottish politicians. Nor has the fact that it was the result of clear, health‐led political leadership. By contrast, the English ban resulted from what is now a real political rarity, a free vote allowed to members of parliament, uninfluenced by political party managers, to end a fiasco of indecision, U‐turns and everything except leadership from the cabinet in London. Buoyed up by success, Scottish politicians may now feel bullish about winning more public health victories ahead of the “ancient enemy” south of the border.

USA: smoke‐free behind bars

In many countries, prisons are almost a by‐word for smoking. It is embedded in prison systems, part of their subcultures and special vocabularies. In Britain, for example, tobacco is “snout” and those who illicitly trade in it are “barons”. The thought of being able to stub out smoking in prisons has normally been regarded as little more than a pipedream.

All credit, then, to the prison authorities in California, the largest and most diverse US state, which now allows no tobacco at all on state property. No employee, visitor or inmate is exempted. With 33 prisons and 170 000 prisoners, seven out of 10 of whom are smokers, this is an extraordinary achievement, especially in light of its description as the country's most overcrowded and gang‐ridden prison system. However, the effect of living and working under the ban will eventually have substantial health benefits, for the 95% of inmates who will eventually leave prison, and also for the 40 000 staff who look after them.

Despite state legislation covering indoor smoking since 1998, covert smoking had continued, and both staff and inmates complained and filed lawsuits based on harm from secondhand smoking. Spurred on by this, and by the health, fire and maintenance costs arguments that apply to any workplace, new state regulations were passed in July 2005 with bipartisan support, including that of California's Republican governor.

It cannot be said that inmates had a choice about stopping smoking, nor that nicotine replacement therapy was there to help them—it is contraindicated for prisoners in California—but in a telephone evaluation survey covering prisons in 58 counties, virtually no problems were reported. On the contrary, a number of recurring, positive comments were relayed by prison health staff. Many prisoners expressed gratitude for the opportunity to stop smoking for good, and some even felt that their success in beating tobacco might empower them to take other, positive steps in their lives. A key factor in many success stories appeared to be the total absence of tobacco: prisoners said that neither seeing nor smelling it, far less handling the stuff, apparently made quitting easier. This is something most would‐be exsmokers in the general community do not have on their side, and it reinforces the oft‐repeated advice to temporarily avoid old haunts and the company of smokers for a while after stopping smoking.

As with many such success stories, showing that one tough nut can be cracked encourages public health officials to reach for another. Legislation to make all California's state mental hospitals similarly tobacco‐free is currently being pursued. (Further information: Stephen L Hansen, hansens2@pacbell.net)

UK: unusual methods make hospital smoke‐free

From a general hospital in the midlands of England comes a curious tale of direct action to enforce health service smoke‐free regulations. The problem was as instructive as the solution. National and local medical and health organisations have been pressing for totally smoke‐free health service premises for more than a quarter of a century. So, with a deadline of December, 2006 for all National Health Service premises to finally be smoke free, many would say it was long overdue.

Nevertheless, it was often a long, messy struggle to agree to and implement a ban. At the hospital in question, those resisting the move invoked the spectre of patients, some possibly elderly, lonely and in the last few months of life, whose only comfort and pleasure was smoking. Mostly, the resisters were smoking members of staff, and the price eventually paid for their agreement to the ban was the establishment of a small, former nurses' sitting‐room as a smoking area. If it was supposed to be for the benefit of the most tobacco‐dependent patients, doctors soon noticed that in reality, it was only ever used by a hard core of hospital employees.

All sorts of strategies were considered to end the exemption, but the prospect of re‐entering a painfully slow cycle of talks with staff representatives was just too much for one doctor. He simply visited a local hardware shop and bought a padlock and the necessary steel fittings. One night, having brought the necessary tools from home, and checked that no one was inside, he fitted the hardware to the smoking room door, clicked the padlock shut and crept away to await developments. The outcome was both remarkable and unexceptional. It was as if the room had never existed: no one said a word. The problem was solved, finally and for good.

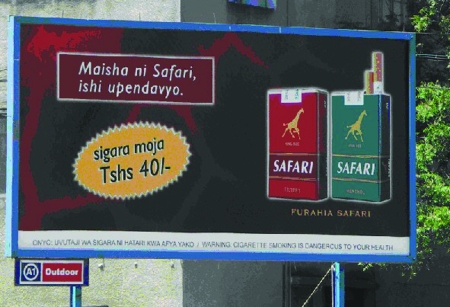

Tanzania: selling single cigarettes The marketing of single cigarettes is a well‐recognised strategy to increase sales among poor people and children, who may find it difficult to obtain the sums necessary to purchase a pack of 20 cigarettes. Yet it is a widely used practice, with Action on Smoking and Health, UK recently drawing attention to its use by BAT in Kenya. As the figure of an advertisement pictured last August shows, the practice is also being employed in Tanzania. Individual cigarettes (sigara mojo) are being advertised by the Tanzania Cigarette Company, a joint venture between RJ Reynolds, a subsidiary of Japan Tobacco International, and the Tanzanian government. The price of a single cigarette is only 40 Tanzanian shillings, equivalent to less than a third of one US cent. [Photo: Martin McKee]

UK: Smoke free bus In July, a total ban on smoking in all workplaces, like the bans already in place in Scotland, Ireland and Italy, will come into force throughout England. For the past year, this bus has been travelling all over the Yorkshire and Humber region in the northeast of England, promoting its “Liberate the workplace” campaign, and now the upcoming workplace legislation.