Abstract

Objective

To investigate the association of the California Comprehensive Tobacco Control Program with self‐reported population trends of cigarette consumption during 1992–2002.

Setting and Participants

Participants were non‐Hispanic white daily smokers (aged 20–64 years, n = 24 317) from the Tobacco Use Supplements to the Current Population Survey (1992–2002). We compared age‐specific trends in consumption among daily smokers in three groups of states with differing tobacco control initiatives: California (CA; high cigarette price/comprehensive programme), New York and New Jersey (high cigarette price/no comprehensive programme), and tobacco‐growing states (TGS; low cigarette price/no comprehensive programme).

Results

There was a general decline in cigarette consumption across all age groups in each category of states between 1992 and 2002, except the oldest age group in the TGS . The largest annual decline in the average number of cigarettes per day was observed among daily smokers in CA who were aged ⩾35 years (−0.41 cigarettes/day/year (95% CI −0.52 to −0.3)). This rate was significantly higher than the −0.22 cigarettes/day/year (95% CI −0.3 to −0.16; p<0.02) observed in same‐age daily smokers from New York and New Jersey, and significantly higher than the rate in same‐age daily smokers from the TGS (−0.15 cigarettes/day/year (95% CI −0.22 to −0.08; p<0.002)). There were no significant differences across state groups in the decline observed in daily smokers aged 20–34 years. In 2002, only 12% of daily smokers in CA smoked more than a pack per day, which was significantly lower than the 17% in New York and New Jersey, which again was significantly lower than the 25% in the TGS.

Conclusions

The California Tobacco Control Program was associated with significant declines in cigarette consumption among daily smokers aged ⩾35 years of age, which in turn should lead to declines in tobacco‐related health effects. The decline in consumption among young adult smokers was a national trend.

Established statistical models from cohort studies have consistently demonstrated that smoking‐related diseases, especially lung cancer, vary exponentially with consumption level and smoking duration.1,2,3,4 A significant reduction in the cigarette consumption level is therefore expected to reduce future risk of lung cancer in the population, which is demonstrated by several studies.5,6,7 In recent years, there has been a call for harm‐reduction strategies to influence smoking levels in continuing smokers8; however, there are few studies of population trends and influences on cigarette consumption.9,10

Individual consumption levels differ considerably with age in the US. Typically, consumption levels increase in young adults, remaining relatively stable in middle‐aged adults, and decline in seniors.9,11,12 Although public health strategies to reduce tobacco‐related disease have focused on promoting quitting and discouraging initiation,13 there is evidence that these strategies may also reduce cigarette consumption levels in the population. In this analysis, we assess the association of the California Tobacco Control Program with declines in cigarette consumption, in comparison with states having only high cigarette prices or with no tobacco control programme. Numerous studies have identified that increases in tobacco‐taxes lead to increases in cigarette prices and result in significant reductions in tobacco smoking behaviour.14 The decrease in cigarette consumption due to price increase has been shown to be a major contributor to the overall reduction in tobacco‐smoking behaviour,15 and many smokers reduce cigarette consumption before making an attempt to quit.16

The California Comprehensive Tobacco Control Program that was introduced in 1989 was the first large state‐specific programme in the USA.17 This programme used funding from a dedicated increase in the tobacco excise tax to support a mass‐media counter‐advertising campaign, “grassroots” activism, particularly aimed at protecting non‐smokers from exposure to second‐hand smoke, school and community initiatives against smoking, and smoking cessation services. This programme introduced the first statewide ban on smoking in the workplace in 1994, which has been associated with reduced consumption levels among continuing smokers.18,19,20,21,22 From the start of the programme in 1989 to 2002, annual per capita cigarette sales in California (CA) declined by 60%, compared with 40% for the rest of the USA.23

In this report, we investigate the effect of the California Tobacco Control Program on daily consumption levels of daily smokers of differing age groups. We compare population trends for non‐Hispanic white daily smokers from CA with those in two comparison groups of states that have similar large combined populations and different tobacco control initiatives. One group is the top TGS with >90% of US tobacco production during the study period,24 that had low excise taxes25 and no comprehensive programme throughout the 1990s; this group includes Kentucky, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia and Georgia. The other group is New York and New Jersey, two neighbouring states that have a combined population size similar to CA and the TGS with tobacco excise taxes similar to CA during the 1990s25 but no comprehensive tobacco control programme.

For our analyses, we used state‐specific estimates of cigarette consumption among smokers from surveys of tobacco use in the US conducted by the Bureau of the Census between 1992 and 2002 in the Tobacco Use Supplements to the Current Population Survey (TUS‐CPS).

Methods

We used the TUS‐CPS from 1992 to 2002 for this analysis. Details regarding the TUS‐CPS are presented elsewhere.26,27 Briefly, the CPS is a continuing monthly labour force household survey conducted by the US Census Bureau in a rotating panel design with independent samples drawn every 4 months. It collects information on the occupations, employment activities and economic status of a nationally representative sample in the US, and covers persons aged ⩾15 years. The CPS also collects information on demographic characteristics such as age, sex, race, marital status, educational attainment and family relationships. Households are initially visited to administer the main survey, and proxy information is allowed. Starting in 1992, the National Cancer Institute coordinated additional monies for the conduct of Tobacco Use Supplements that maximised self‐reported smoking data. Response rates to the TUS were in the range of 81–83% for proxy and self‐report individuals, and in the range of 61–66% for self‐reports only.28

We combined data from three monthly TUS‐CPS in the 1992–3, 1995–6, 1998–9 (September, January and May) and 2001–2 (June, November and February) CPS, using self‐respondents between the ages of 20–64 years. Respondents were identified as never‐smokers if they answered “no” to the question, “Have you ever smoked 100 cigarettes?” Those answering “yes” were further asked if they smoked every day, on some days or not at all. Those who answered that they smoked every day were further asked, “On average about how many cigarettes do you now smoke each day?”. We categorised those who smoked >20 cigarettes (a pack) per day as heavy smokers.

As there are major consumption differences across race/ethnicity groups, we limited our analyses to only non‐Hispanic whites (n = 24 317).

Statistical analyses

Average number of cigarettes smoked per day was the outcome of primary interest, and we used least‐squares regression to estimate the linear trend in cigarette consumption over time during the study period, separately for each age group. All estimates were weighted by TUS‐CPS weights, which account for selection probabilities from the sampling design and adjust for survey non‐response.26,27 To account for the discrete distribution of the response variable, robust CIs and p values were computed through the Jackknife using the published replicate weights with Fay's balanced repeated replication.27,28 This also accounts for the complex survey design, and any additional variance due to weighting. All models controlled for gender, education (not a high school graduate, high school graduate, some college, college degree), household income in 2001 constant dollars and a binary variable for household income above twice the Census Bureau poverty threshold (by size of family and number of children)29 using standard demographics collected on the CPS. Indicators for the state groups (CA, NY and NJ and the TGS) were the independent variables of interest, and to assess trends over time we included a time × state group interaction. Trends in the proportion of daily smokers who were heavy smokers (reported consumption >1 pack/day) were similarly assessed using logistic regression, for the combined age groups by adjusting for age (20–34, 35–49, 50–64 years) and the above‐mentioned covariates. Estimates were computed in SAS‐callable SUDAAN V.9.0.1, using PROC REGRESS for least‐squares regression and PROC CROSSTABS for weighted proportions. Estimates are presented with 95% CIs and statistical significance is assessed at the 5% level.

We categorised respondents into three age groups for the purpose of our analyses: 20–34, 35–49 and 50–64 years. We based this categorisation on a 15‐year period that would provide three fairly different populations with different smoking behaviours. We excluded those aged >64 years, because they would be more prone to illness and death from smoking, and we excluded those aged <20 years, who are probably still engaged in the uptake process. The younger age group category of 20–34 years may still be in the process of solidifying their smoking behaviour and still be less addicted than the older groups. The middle‐age group of 35–49 years would presumably be well beyond the final stages of the uptake process and more likely to have similar attributes to the older age group in terms of smoking behaviour.

Results

Between 1992 and 2002, the average number of cigarettes consumed by non‐Hispanic white daily smokers each year decreased across all age groups and states, except for the oldest smokers in the TGS (table 1). However, the rate of decline in consumption differed between the groups of states and within the three age groups.

Table 1 Annual decline in the average number of daily cigarettes smoked by daily smokers in California, New York and New Jersey, and the tobacco‐growing states, according to age group*.

| Annual decline in number of cigarettes smoked per day by daily smokers (95% CI) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | |||||||||

| 20–34 years | 35–49 years | 50–64 years | |||||||

| n | Estimate (95% CI)† | p Value‡ | n | Estimate | p Value‡ | n | Estimate | p Value‡ | |

| CA | 1333 | −0.19 (−0.34 to −0.05) | Reference | 1789 | −0.41 (−0.55 to −0.27) | Reference | 1081 | −0.42 (−0.59 to −0.24) | Reference |

| NY/NJ | 4202 | −0.25 (−0.34 to −0.16) | 0.53 | 5100 | −0.22 (−0.30 to −0.14) | 0.032 | 2923 | −0.23 (−0.35 to −0.11) | 0.073 |

| TGS | 2485 | −0.32 (−0.41 to −0.22) | 0.18 | 3345 | −0.19 (−0.27 to −0.10) | 0.011 | 1957 | −0.09 (−0.21 to 0.02) | 0.005 |

CA, California; NJ, New Jersey; NY, New York; TGS; tobacco‐growing states.

*Models adjusted for gender, education level, income and poverty status.

†95% CIs for the rate of decline in cigarettes/day/year. The rate of decline is statistically significant for all state‐age groups because they do not include the null value, except for smokers 50–64 years of age in TGS.

‡p Value is indicative of whether the rate of decline is significantly different than for CA (as the reference state).

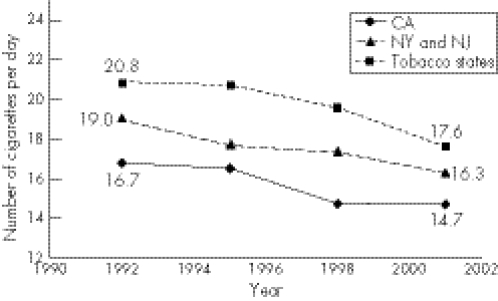

Trends among smokers 20–34 years old

Between 1992 and 2002, there were significant declines in smoking consumption levels among daily smokers aged 20–34 years in all three states (p<0.01; fig 1). In 1992–3, CA daily smokers smoked an average of 16.7 cigarettes/day, which was less than their counterparts in NY and NJ (19.0 cigarettes/day) or TGS (20.8 cigarettes/day) (p<0.01; fig 1). The decline in the average consumption levels for this age group over the study period was between 0.2 and 0.3 cigarettes/day/year and there were no significant difference in the rate of decline across the states (table 1).

Figure 1 Cigarette consumption for daily non‐Hispanic white smokers aged 20–34 years in California (CA), New York and New Jersey (NY and NJ) and tobacco‐growing states, from the Tobacco Use Supplements to the Current Population Surveys of 1992–3, 1995–6, 1998–9 and 2001–2.

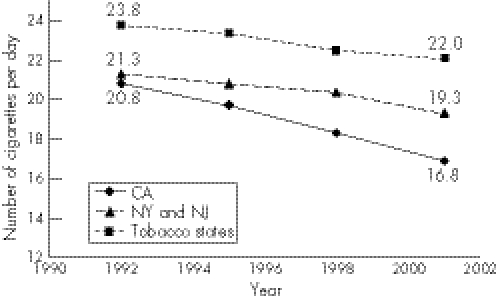

Trends among smokers 35–49 years old

At the start of the study period in 1992–3, 35–49 year‐old daily smokers in CA smoked an average of 20.8 cigarettes/day, which was similar to the smoking level in NY/NJ daily smokers of this age (21.3 cigarettes/day) (fig 1). Both these levels were significantly lower than the average 23.8 cigarettes/day of daily smokers of this age in TGS (p<0.01; fig 2). Although daily smoking consumption declined for all three groups of states, cigarette consumption for CA smokers (−0.41 cigarettes/day/year) decreased at twice the rate seen in either NY and NJ (−0.22 cigarettes/day/year) or the TGS (−0.19 cigarettes/day/year); these differences were statistically significant (table 1).

Figure 2 Cigarette consumption for daily non‐Hispanic white smokers aged 35–49 years in California (CA), New York and New Jersey (NY and NJ) and tobacco‐growing states from the Tobacco Use Supplements to the Current Population Surveys of 1992–3, 1995–6, 1998–9 and 2001–2.

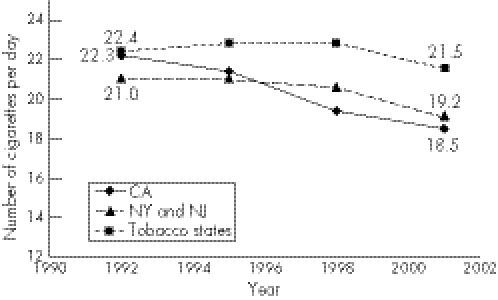

Trends among smokers 50–64 years old

In 1992–3, smokers aged 50–64 years in all three groups of states had comparable consumption levels: 22 cigarettes/day for both CA and the TGS and 21 cigarettes/day for NY and NJ (fig 3). Over the study period, the consumption rates declined by −0.42 cigarettes/day/year for CA daily smokers, by −0.23 cigarettes/day/year for NY and NJ daily smokers and by −0.09 cigarettes/day/year for daily smokers from the TGS. Although the declines in CA and NY/NJ were very similar to those for daily smokers aged 35–49 years, smaller sample sizes meant that the difference in rates between smokers 50–64 years old from these state groups reached borderline statistical significance (p = 0.073). However, the difference in the rates between CA and the TGS was clearly significant (p = 0.005; table 1), whereas the difference in rates between NY/NJ and the TGS was not significant (p = 0.14).

Figure 3 Cigarette consumption for daily non‐Hispanic white smokers aged 50–64 years in California (CA), New York and New Jersey (NY and NJ) and the tobacco‐growing states (TGS), from the Tobacco Use Supplements to the Current Population Surveys of 1992–3, 1995–6, 1998–9 and 2001–2.

To assess the difference in the rate of decline in consumption among those aged ⩾35 years who are unlikely to be still solidifying their smoking behaviour, we combined the data across the two older age groups for further analyses. Over the decade 1992–2002, the decline in cigarette consumption levels among daily smokers aged 35–64 years was −0.41 (95% CI −0.52 to −0.3) cigarettes/day/year in CA, −0.23 (95% CI −0.3 to −0.16) cigarettes/day/year in NY and NJ, and −0.15 (95% CI −0.22 to −0.08) cigarettes/day/year in TGS. The decline in cigarette consumption for this age group was highest among CA smokers, followed by NY and NJ, and TGS.

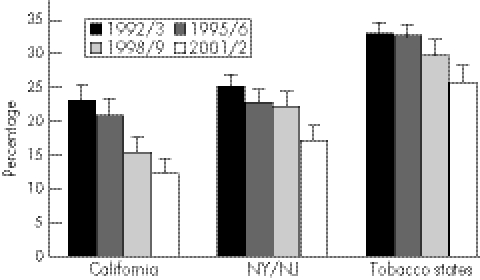

Differences in proportion of those who smoke more than a pack a day between 1992 and 2002

In 1992–3, almost one third of daily smokers from the TGS reported smoking more than a pack of cigarettes each day, compared with just under one quarter of smokers from NY and NJ or CA (fig 4). For the TGS, this proportion declined by 22% over the decade to just over one quarter of smokers (25.8 (1.29)). In NY and NJ, this proportion declined by 31% so that just over one‐sixth of smokers (17.3 (2.2)) still smoked more than a pack a day in 2002. In CA, this proportion declined by 47% during the same period, so that in 2002, only one out of eight smokers (12.2 (2.4)) consumed more than a pack of cigarettes per day. In a multivariate logistic regression model, the decline in CA was significantly greater than that in either NY and NJ (p<0.02) or TGS (p<0.002).

Figure 4 Percentage of heavy smokers (>20 cigarettes/day) among daily white non‐Hispanic white smokers in California (CA), New York and New Jersey (NY and NJ) and the tobacco‐growing states, from the Tobacco Use Supplements to the Current Population Surveys of 1992–3, 1995–6, 1998–9 and 2001–2.

Discussion

Our results suggest that the Comprehensive Tobacco Control Program in CA had the most consistent effect on decreasing the rate of cigarette consumption among those aged ⩾35 years. Daily smokers in this group had significantly lower rates of decline if they were in the comparison states of NY and NJ and the TGS that did not have Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs.

These population data show that cigarette consumption among non‐Hispanic white daily smokers declined substantially in three very different groups of states in the US in the years 1992–2002. In this paper, we noted that the California Tobacco Control Program was associated with a reduction in cigarette consumption among daily smokers who are aged⩾35 years. This complements other analyses that have demonstrated that the programme was significantly associated with increased successful cessation among the young adults as well as markedly reduced initiation rates among youth.30,31 Existing models of lung cancer suggest that each of these changes will be associated with marked reductions in tobacco‐related disease.1,2,3,4

Only one age–state group did not show a significant rate of decreased consumption during the study period: this was the 50–64‐year‐old daily smokers in TGS. The slower spread of social norms against tobacco among the more established smokers in TGS might partly explain the lack of a significant decline in this older age group. The younger age groups (aged 20–34 years) in TGS, on the other hand, were declining their consumption levels at a rate not different from the other groups of states and this needs further exploration.

When comparing our results on consumption with the results reported for successful quitting, the California Program seemed to significantly increase quitting among the younger age group of smokers but not among those who are ⩾35 years. Yet the latter group of smokers in California, who are mostly the heavier smokers,15 significantly declined their cigarette consumption during the period of the Comprehensive Tobacco Control Program. These results suggest that all age groups of smokers were responsive to the CA campaign by increasing their rate of successful quitting or reducing their consumption levels.

Studies using short‐term biomarkers32,33 with smokers who were forced to reduce cigarette consumption as part of a controlled study have reported that smokers can still compensate for lower consumption by extracting more nicotine from each cigarette through deep inhalation and delayed exhalation leading to similar adverse health effects. However, studies of longer‐term biomarkers (eg, hair nicotine concentrations) in smokers who reported that they had reduced their cigarette consumption noted decreased levels of the biomarker concentration.34 Compensation may be less of an issue in data from cross‐sectional population studies compared with controlled study populations who are forced to decrease the number of cigarettes they smoked over a relatively short time period. A strength of this study is that it uses repeated cross‐sectional estimates of population behaviour from supplements to the CPS, the large ongoing monthly survey conducted by the Bureau of the Census to address labour‐force issues. While these studies do not have biomarker validation, the changes in smoker reports of their own consumption are consistent with the increasing decline in cigarette sales35,36 suggesting that these are real changes in smoking behaviour.

The marked decline in continuing smokers consuming more than a pack of cigarettes per day was also larger among Californians compared with heavy smokers in NY and NJ and TGS. The percentage of heavy smokers in TGS in 2002 (25%) was similar to the nationwide percentage of heavy smokers in 1974.35 A decline of close to 50% in the percentage of heavy smokers in CA indicates that the changes are occurring in the very group who are most at risk for health consequences from their smoking behaviour. Analyses from the 50‐year follow‐up of the British doctors cohort study noted a dose–response relationship between the level of daily consumption and death37 that was consistent with the multistage model of lung cancer.3

What this paper adds

Comprehensive tobacco control programmes have been proposed as the best tobacco control approach because they incorporate a range of initiatives including smoke cessation programmes, media campaigns, community‐based advocacy, and increased cigarette excise tax.

However, there are no studies that, compare the effectiveness of such an approach to other tobacco control approaches, or to the absence of any tobacco control initiatives, on smoking behaviour in a population setting.

Our analyses present new evidence that compared with states with no tobacco control initiatives (in this case tobacco‐growing states in the US), or states with an increased cigarette price as a tobacco control measure (in this case New York and New Jersey), the comprehensive tobacco control programmes (as demonstrated by the California Tobacco Control Program) are more effective in terms of decreasing cigarette consumption among regular smokers aged ⩾35 years.

Our finding has important health policy implications to support such tobacco control programmes that are likely to translate into a decline in the prevalence of adverse health consequences of smoking.

In conclusion, our study provides further evidence that there is a major secular trend for reduced smoking in the US and that our analyses suggest that this is being led by the statewide tobacco control programmes. These programmes are reducing initiation in the young and promoting successful quitting in young adults, and are also associated with a decline in consumption in older continuing smokers. Taken as a whole, the benefits from the declines in smoking behaviour will lead to a corresponding continued decline in the prevalence of adverse health consequences of smoking through the next 50 years.

Abbreviations

CA - California

TGS - tobacco‐growing states

TUS‐CPS - Tobacco Use Supplements to the Current Population Survey

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by Tobacco‐Related Disease Research Program grants (12KT‐0158, 12RT‐0082 and 15RT‐0238) from the University of California, California, USA.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.US Department of Health and Human Services The health consequences of smoking: a report of the surgeon general. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2004

- 2.Knoke J D, Shanks T G, Vaughn J W.et al Lung cancer mortality is related to age in addition to duration and intensity of cigarette smoking: an analysis of CPS‐I data. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 200413949–957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doll R, Peto R. Cigarette smoking and bronchial carcinoma: dose and time relationships among regular smokers and lifelong non‐smokers. J Epidemiol Community Health 197832303–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flanders W D, Lally C A, Zhu B P.et al Lung cancer mortality in relation to age, duration of smoking, and daily cigarette consumption: results from Cancer Prevention Study II. Cancer Res 2003636556–6562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lubin J H, Blot W J, Berrino F.et al Modifying risk of developing lung cancer by changing habits of cigarette smoking. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 19842881953–1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benhamou E, Benhamou S, Auquier A.et al Changes in patterns of cigarette smoking and lung cancer risk: results of a case‐control study. Br J Cancer 198960601–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Godtfredsen N S, Prescott E, Osler M. Effect of smoking reduction on lung cancer risk. J Am Med Assoc 20052941505–1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stratton K, Shetty P, Wallace R.et al, eds. Clearing the smoke. assessing the science base for tobacco harm reduction In: Committee to assess the science base for tobacco harm reduction, Board on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention. Institute of Medicine. Washington, DC: National Academy Press 2001

- 9.US Department of Health and Human Services Reducing the health consequences of smoking: 25 years of progress. a report of the surgeon general. U. S. Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control, Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health. DHHS publication No. (CDC) 89–8411 1989

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2005541122–1127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haenzel W, Shimkin M B, Miller H P.Tobacco smoking patterns in the United States. Public Health Service Publication No 463. Library of Congress Catalog 56–60079 1956 [PubMed]

- 12.Burns D M, Major J M, Anderson C M.et al Changes in cross‐sectional measures of cessation, number of cigarettes smoked per day and time to first cigarette—California and national data. Those Who Continue to Smoke. Is Achieving Abstinence Harder and Do We Need to Change Our Interventions? Smoking and Tobacco Control Monograph No. 15 Bethesda, MD: U, S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, NIH Publication No. 92‐3316 2003

- 13.Starr G, Rogers T, Schooley M.et alKey outcome indicators for evaluating Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs, Atlanta GA: CDC 2005

- 14.US Department of Health and Human Services Reducing tobacco use: a report of the surgeon general. U. S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health 2000

- 15.Sheu M L, Hu T W, Keeler T E.et al The effect of a major cigarette price change on smoking behavior in California: a zero‐inflated negative binomial model. Health Econ 200413781–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farkas A J, Gilpin E A, Distefan J M.et al The effects of household and workplace smoking restrictions on quitting behaviors. Tob Control 19998261–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bal D G, Kizer K W, Felten P G.et al Reducing tobacco consumption in California. Development of a statewide anti‐tobacco use campaign. J Am Med Assoc 19902641570–1574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eriksen M P, Gottlieb N H. A review of the health impact of smoking control at the workplace. Am J Health Promot 19981383–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chapman S, Borland R, Scollo M.et al The impact of smoke‐free workplaces on declining cigarette consumption in Australia and the United States. Am J Pub Health 1999891018–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hopkins D P, Brise P A, Husten C J, Reviews of evidence regarding interventions to reduce tobacco use exposure to environmental tobacco smoke et alAm J Prev Med 200120(Suppl)16–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gilpin E A, White M M, Farkas A J.et al Home smoking restrictions: which smokers have them and how they are associated with smoking behavior. Nic Tob Res 19991153–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilpin E A, Pierce J P. The California Tobacco Control Program and potential harm reduction through reduced cigarette consumption in continuing smokers. Nic Tob Res 20024157–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gilpin E A, White M M, White V M.et alTobacco control successes in California: a focus on young people, results from the California Tobacco Surveys, 1990–2002. La Jolla, CA: University of California, 2004

- 24.US Department of Agriculture Trends in US tobacco farming. Outlook Report November 2004 (TBS‐257‐02)

- 25.Orzechowski W, Walker R C.The tax burden on tobacco. Historical compilation. Volume 39. Arlington, VA: Orzechowski & Walker, 2004

- 26.US Department of Commerce, Census Bureau National Cancer Institute and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Co‐sponsored Tobacco Use Supplement to the Current Population Survey (2001–2002): Current Population Survey, June 2001, November 2001, and February 2002, Tobacco Use Supplement file technical documentation: Appendix 17. ( http://www.census.gov/apsd/techdoc/cps/cpsJun01Nov01Feb02.pdf ) (accessed 7 Feb 2007)

- 27.US Bureau of Labor Statistics and US Census Bureau Current Population Survey. Design and methodology. Technical Paper 63RV. ( http://www.census.gov/prod/2002pubs/tp63rv.pdf )(accessed 7 Feb 2007)

- 28.Judkins J R. Fay's method for variance estimation. J Official Stat 19906223–239. [Google Scholar]

- 29.US Census Bureau, Housing and Household Economic Statistics Division ( http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/poverty/threshld.html ) (accessed 7 Feb 2007)

- 30.Messer K, Pierce J P, Zhu S H.et al The California Tobacco Control Program's effect on adult smokers: (1) Smoking cessation. Tobacco Control 20071685–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pierce J P, White M M, Gilpin E A. Adolescent smoking decline during California's Tobacco Control Program. Tob Control 200514207–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benowitz N L, Jacob P, 3rd, Kozlowski L T.et al Influence of smoking fewer cigarettes on exposure to tar, nicotine, and carbon monoxide. N Engl J Med 19863151310–1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scherer G. Smoking behaviour and compensation: a review of the literature. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 19991451–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uematsu T. Utilization of hair analysis for therapeutic drug monitoring with a special reference to ofloxacin and to nicotine. Forensic Sci Int 199363261–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.US Department of Health and Human Services Reducing the health consequences of smoking: 25 years of progress. A report of the surgeon general. US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control, Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health. DHHS Publication No. (CDC) 89‐8411 1989

- 36.Gilpen E A, Messer K, White M M.et al What contributed to the major decline in per capita cigarette consumption during California's comprehensive tobacco control program? Tobacco Control 200615308–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J.et al Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years' observations on male British doctors. BMJ 20043281519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]