Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the effect of different types of adjunctive support to stop smoking for individuals contacting telephone “quitlines,” including call‐back counselling, different counselling techniques and provision of self help materials.

Data sources

This review includes quitline studies identified as part of Cochrane reviews of telephone counselling and self help materials for smoking cessation. We updated the searches for this review.

Study selection

We included studies that were randomised or quasi‐randomised controlled trials of any quitline or related service with follow‐up of at least six months.

Data extraction

Data were extracted by one author and checked by a second. The cessation outcome was numbers quit at longest follow‐up taking the strictest definition of abstinence available, and assuming participants lost to follow‐up continued to smoke.

Data synthesis

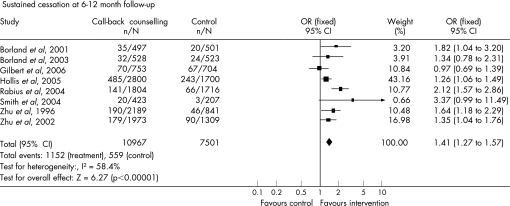

We identified 14 relevant studies. Eight studies (18 500 participants) comparing multiple call‐backs to a single contact increased quitting in the intervention group (Mantel‐Haenszel fixed effect odds ratio 1.41, 95% confidence interval 1.27 to 1.57). Two unpublished studies without sufficient data to include in the meta‐analysis also reported positive effects. Three call‐back trials compared two schedules of multiple calls. Two found a significant dose‐response effect and one did not detect a difference. We did not find consistent differences in comparisons between counselling approaches (two trials) or between different types of self help materials supplied following quitline contact (three trials).

Conclusions

Multiple call‐back counselling improves long term cessation for smokers who contact quitline services. Offering more calls may improve success rates. We failed to detect an effect of the type of counselling or the type of self help materials supplied as adjuncts to quitline counselling.

Keywords: smoking cessation, quitlines, call‐back counselling, tailoring, self help

Telephone quitlines are an established means of providing support for smoking cessation.1 We aim here to evaluate the effect of different interventions for smokers who call quitlines seeking help to quit smoking. The support offered by quitlines may include mailed materials, recorded messages, counselling at the time of the call, call‐back from a counsellor, access to pharmacotherapy and combinations of these elements. In this review we principally consider the effect of providing call‐back counselling after an initial call. We also consider the evidence that there is a difference by method of counselling and examine the effect of adjunctive self help materials (excluding evaluations of the effect of personally tailored materials).

Methods

Data sources

This paper draws on the results of a recently updated Cochrane review analysing 48 trials of telephone counselling used in a variety of settings including quitlines.2 In January 2006 we searched the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group Specialised Register using the free text terms “telephone*”, “quitline*” or “helpline*” or the keywords “telephone counselling” or “Hotlines” or “Telephone”. The register incorporates the results of systematic searches for trials on tobacco addiction in Medline, EMBASE, PsycINFO and Science Citation Index electronic databases and includes trials reported in conference abstracts including Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco meetings. We updated the search in November 2006 and identified one new study that recruited quitline callers.3 We excluded this because it only compared different types of individually tailored materials. We contacted the principal investigators of previously identified unpublished trials to see if further data were available. Some studies identified by this search strategy compare the effect of different types of self help materials for callers to quitlines. These are covered by the Cochrane review of self help materials so the data are drawn from this source.4

Study selection

We included randomised or quasi‐randomised controlled trials that enrolled smokers or recent quitters who called a telephone service that offered quitting support. The intervention was one or more sessions of call‐back cessation counselling (also called proactive or counsellor initiated counselling); or comparison of a different counselling protocol or of different forms of self help materials at the initial call. Control conditions included mailed self help materials; advice, counselling or recorded messages during the initial call. We excluded trials or arms of trials that only evaluated the use of individually tailored self help materials. The outcome was smoking status at least six months after the initial contact.

Data extraction

For both the Cochrane reviews one author (LS) identified potentially relevant studies and extracted data. A second author checked inclusion criteria and data.

Data synthesis

The primary outcome was the proportion of quitters at the longest follow up, using the strictest measure of abstinence reported. We preferred sustained and biochemically validated abstinence to point prevalence and/or self reported quitting. We used as the denominator the number randomised, assuming participants lost to follow up continued to smoke.

We grouped studies to address three central questions:

Call‐back counselling: does multiple contact intervention increase the proportion of quitters compared to a single telephone contact control?

Counselling method: is there a difference in proportion of quitters between different counselling protocols at a single contact?

Self help materials: is there a difference in proportion of quitters with different types including population targeted materials.

We summarise the main characteristics and results of the studies in each of these three groups. For the first group, we assessed heterogeneity using the I2 statistic5 and estimated a pooled effect size for quitting at the longest follow‐up, using a Mantel‐Haenszel fixed effect method to derive an odds ratio with 95% confidence intervals.6 The other two groups included a smaller number of trials and we therefore did not calculate a pooled estimate.

Results

The review includes 14 trials that recruited callers to quitlines. Ten trials evaluated call‐back counselling.7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16 Two trials evaluated the counselling method at the initial call.17,18 Three trials compared adjunctive self help materials at the initial call,13,19,20 one of which13 also contributed to the first group. Two of the included studies in the call‐back group12,16 were identified for the Cochrane review2 from conference reports but not formally included because results were not available in enough detail to extract data for meta‐analysis. For the same reason they do not contribute to the meta‐analysis in this paper but we describe their results separately. Full results of the first of these are published in this supplement.21

Call‐back counselling

Ten studies evaluated counsellor initiated calls in the following days or weeks after the initial contact. Two studies by Borland and colleagues used the quitline services in Victoria.7,8 Three were conducted by Zhu and colleagues in the setting of the California Smokers' Helpline,14,15,16 and two were conducted by the American Cancer Society (ACS).11,12 The remaining studies involved quitlines in the United Kingdom ,9 Canada13 and Oregon, United States.10

The number of calls constituting the intervention varied, and four trials had multiple intervention arms comparing different schedules of calls.10,12,13,14 In one California study15 the control group could call back for counselling—which 32% received, while only 73% of the intervention group received their intended intervention. The main characteristics of the intervention and control conditions of all call‐back trials are shown in table 1.

Table 1 Trials of call‐back counselling interventions.

| Study/country | Population (follow‐up rate) | Intervention(s) | Control | Criteria for cessation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Borland et al, 20017 Australia | 998 callers to Victorian quitline (66%) | Additional calls, 2 or more according to need, average 2.8 | Motivational counselling at initial call, self help materials | Quit at 12 months (sustained for 9 months) | ||||

| Borland et al, 20038 Australia | 1051* callers to Victorian quitline (76%) | Additional calls usually over 2–3 weeks, average 4.8 | Quit pack and 3 mailings of tailored letters, possibility of brief counselling at initial call | Quit at 12 months (sustained for 9 months) | ||||

| Gilbert et al, 20069 United Kingdom | 1457 UK quitline callers (63%) | Up to 5 calls over 4 weeks. 26% received none, 42% received ⩾4 | Counselling at initial call, self help materials | Quit at 12 months (sustained for 6 months) | ||||

| Hollis et al, 200510 United States | 4614 Oregon quitline users (69%) | Factorial trial of free NRT and 3 levels of counselling(1) Moderate counselling; 30–40 minutes motivational interview, brief 2nd call, tailored self help.(2) As (1) plus offer of 4 further calls | Brief 15‐minute telephone counselling, self help materials and referral information, +/− NRT | Quit at 12 months (for >30 days) | ||||

| Rabius et al, 200411 United States | 3522 quitline callers (∼66% at 3 months) | 5 calls over 2 weeks (Stanford model) | Self help materials | Quit at 6 months (for 3 months) | ||||

| Smith et al, 200413 Canada | 632 quitline callers (73% print only, 62% counselling at 12 months) | (1) 50‐minute initial call then 2 5–10‐minute calls at 2 and 7 days | Self help materials | Quit at 12 months (sustained) | ||||

| (2) As (1) plus 4 further calls at 14, 21, 35 and 49 days (factorial with self help variants) | ||||||||

| Zhu et al, 199614 United States | 3030 California quitline callers (86%) | (1) single 50‐minute call pre‐quit date | Self help materials | Quit at 13 months (for 12 months) | ||||

| (2) As (1) plus up to 5 further calls over 1 month | ||||||||

| Zhu et al, 200215 United States | 3282 California quitline callers seeking counselling (71%) | Up to 7 calls over 3 months, First session pre‐quit (72% received at least 1 call average 3 sessions | Self help materials. Telephone counselling also provided if requested (32% received) | Quit at 13 months (for 12 months) | ||||

| Rabius et al, 2006†12,21 | 6322 American Cancer Society quitline callers (52%) | 3×2 factorial trial of session length and use of boosters | Self help materials only | Quit at 6 months | ||||

| Zhu et al 2004†16 | 1101 pregnant women calling California smokers' helpline | Up to 7 counselling calls (1 pre‐quit, up to 6 follow‐up). | Quit kit including American Cancer Society booklet for pregnant smokers | Quit for ⩾30 days at 3rd trimester evaluation |

NRT, nicotine replacement therapy.

*In relevant arms.

†Not included in meta‐analysis.

The control group quit rates varied across trials, reflecting differences that are likely to include the motivation and other characteristics of the callers, the amount of support provided at the initial call, the length of follow‐up, loss to follow‐up and definition of abstinence. As an indication of this range the quit rates in the control arms ranged from 1% sustained at 12 months (2% if losses to follow‐up excluded) for a pamphlet alone in Canada13 to 12% for 30 day abstinence at 12 months, or 17% when combined with an offer of free nicotine patch, in Oregon.10 This trial also reported the highest quit rates in an intervention arm; 21% for intensive counselling and the offer of NRT.

The pooled data from 18 500 participants in the eight trials with sufficient data to pool7,8,9,10,11,13,14,15 show a benefit from the call‐back counselling compared to the control condition (OR 1.41, 95% CI 1.27 to 1.57) (fig 1). The odds ratios for individual trials ranged from 1.09 to 3.4.13 There was some evidence of heterogeneity (I2 58.4%5) but using a random effects analysis did not materially change the size or significance of the estimate. Five of the individual trials reported significant positive effects. Limiting the intervention condition to the less intensive arm in the three studies testing multiple interventions10,13,14 marginally reduced the estimate (OR 1.39, 95% CI 1.24 to 1.56). Of the two trials with small and non‐significant odds ratios, the poor outcome in one was suggested to be because of concomitant use of tailored materials that could give conflicting advice.8 In the other trial, within the UK quitline,9 all participants received counselling during their initial call as well as the offer of a quitting pack. Six‐month sustained abstinence rates at 12 months were around 9% in both groups. The lack of additional effect was attributed to the absence of an extended pre‐quit session, and the unstructured nature of the follow‐up sessions. The authors commented that “non‐structured counselling, led by the client, can result in being overly empathetic regarding the difficulty of changing, with insufficient emphasis on reducing ambivalence and preparation for change.”

Figure 1 Pooled results of eight trials of call‐back counselling.

Effect of number of intended calls

Three of the call‐back trials in the meta‐analysis10,13,14 also compared different schedules and numbers of call‐backs allowing a test of a dose‐response effect. In the Canadian study no difference was reported between two and six additional calls following an initial 50 minute session.13 In one California study14 six calls increased rates by a further 2 percentage points over a single pre‐quit call‐back, a marginally significant effect, (OR 1.36, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.83). In the Oregon study,10 an initial extended counselling call with the offer of four further calls increased quit rates by about 1 percentage point over an extended counselling call and a brief reminder call, which again was just significant (OR 1.22, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.49). The average number of contacts increased from under two to fewer than three but this was reported to increase satisfaction with the service and the number of calls.

Call‐back counselling trials not in the meta‐analysis

Two studies were not included in the meta‐analysis. One was unpublished and had insufficient data.16 The other was only published in full in this special issue.21 It evaluated different numbers and durations of counselling sessions. There was a significant overall effect comparing all counselled groups to mailed self help materials only (11% vs 8% “intent to treat” quit; p<0.005). Differences in quit rates between counselling formats were relatively small but the number of sessions seemed more important than the total time. Quit rates ranged from 8.5% for three standard length sessions without booster to 14.1% for five brief sessions plus two boosters.

In the other unpublished call‐back study not in the meta‐analysis,16 a seven call protocol significantly increased quit rates over self help materials alone for pregnant smokers calling the California smokers' helpline. At the third trimester evaluation, 21.4% of the counselling group versus 12.4% of the self help group quit for 30 days (p = <0.001). This contrasts with a recently published study of proactive multisession counselling compared to brief counselling for pregnant smokers referred for telephone counselling by providers.22 That study failed to detect an overall benefit, although there was some evidence of efficacy among subgroups. Differences between help‐seeking pregnant smokers and those recruited through the healthcare system may contribute to the different findings.

Comparison of counselling methods

Two studies compared different counselling interventions provided during the initial call (see table 2). Neither of these detected a difference between the approaches, with overall quit rates of about 19%18 and 10%17 at 6 months. In the second trial17 an opportunistic 12 month follow‐up of a subgroup of participants found a higher quit rate in the population targeted condition.

Table 2 Trials of different counselling interventions at time of first contact.

| Study/country | Population (follow‐up rate) | Intervention(s) | Control | Criteria for cessation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thompson et al, 199318 United States | 382 smokers/recent quitters (83%) | Immediate counselling based on stage, script tailored to blue collar workers using focus groups | Immediate counselling based on standard fact sheets. Self help materials | 6 months (PP) | ||||

| Orleans et al, 199817 United States | 1422 African Americans calling Cancer Information Service (CIS) (63%) | Immediate counselling tailored to African Americans and tailored self help “Pathways to Freedom” | Immediate standard CIS telephone counselling and standard guide “Clearing the Air” | 6 months (PP) (12 months for 445 participants) |

PP, point prevalence.

Comparison of different forms of adjunctive self help materials

For quitlines that do not routinely offer call‐back counselling, support might be enhanced by providing self help materials. Standard self help materials have some effect in a range of settings although the effect size is small.4 Three trials have compared self help materials in quitline settings (see table 3).

Table 3 Trials of different standard or population targeted self help materials for quitline callers.

| Study/country | Population (follow‐up rate) | Intervention(s) | Control | Criteria for cessation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cummings et al, 198819 United States | 1534* callers to hotline in New York | One of 4 booklets varied by format and instructions | Control booklet, no specific quitting advice | Quit at 6 months (sustained for 5 months) | ||||

| Davis et al, 199220 United States | 630* women with young children calling Cancer Information Service | (1) “Quitting Times” tailored for target population.(2) “Freedom from Smoking for You and Your Family” | Clearing the Air (National Cancer Institute Guide) | Quit at 6 months (for at least 1 week) | ||||

| Smith et al, 200413 Canada | 632 callers to a Canadian quitline (73% print only, 62% call‐backs at 12 months) | Intensive self help—44 page booklet “One Step at a Time” versions for men and women (factorial design with call‐back conditions) | Minimal self help single page pamphlet | Quit at 12 months (sustained) |

*Excludes randomised participants lost to follow‐up.

Cummings and colleagues19 compared four self help booklets using either a day by day plan for quitting or a less structured menu format, and a “cold turkey” sudden quit versus gradual reduction approach. All booklets covered preparation for quitting, making a commitment, coping with urges and maintenance. A shorter control booklet only covered the hazards of smoking and did not give instructions for quitting. No significant differences in quit rates were detected between any of the experimental booklets or the control. About 6% reported at least 5 months' abstinence at the 6 month follow‐up and 16%–19% had been quit for at least a week. Although reported use of the books was high, undertaking specific recommended activities was not a predictor of success. The best predictor was participants' initial assessment of their likelihood of success. Another trial20 compared three sets of materials for women smokers with young children who called the US Cancer Information Service hotline. Again there was no significant difference between the guides, with 12.5% of those followed up reporting at least a week of abstinence at 6‐month follow‐up. One trial evaluating call‐back counselling included a factorial test of different written materials.13 It detected no difference between a 44 page booklet, tailored for either men or women, compared to a single page pamphlet among a population receiving at least three counselling calls. Overall, this evidence suggests that in the population of smokers seeking help from quitlines the choice between different standard self help materials is not of critical importance.

Discussion

In controlled trials in quitline settings call‐back counselling improved quit rates over mailed materials or brief counselling at the first contact. These were pragmatic trials with potential sources of bias. Only one study attempted biochemical validation in a convenience sample and found a high refusal rate.14 It is claimed that the rate of misreport is low in population based studies, and unlikely to differentially affect intervention and control groups.23 While using self reported outcomes may overestimate quit rates, treating all non‐responders as failures probably leads to an underestimate,24 as does inclusion of people who did not receive the intervention. We conducted a sensitivity analysis for the meta‐analysis: excluding participants lost to follow‐up from the denominators did not greatly affect the relative effect because most studies had similar dropout rates across intervention and control groups. The choice of cessation outcome might also affect the meta‐analysis results. We used a sustained measure of quitting in all studies, but point prevalence rates where reported were substantially higher. In most cases the relative treatment effect was similar if a more lenient measure of quitting was chosen but in one case delayed quitting activity among controls reversed the relative difference.13

Intervention implementation was often incomplete. In some trials participants refused call back counselling; some participants could not be contacted and people often did not receive all intended calls. Trial reports typically noted a dose response with higher quit rates as the number of completed calls increased. Higher quit rates in those receiving more support are not necessarily evidence of efficacy since these people may be more motivated and thus more successful, but if they are seeking more help they may be having more difficulty quitting: where number of calls was not restricted; receiving a very high number of calls tended to predict failure.7 Borland noted that in two trials7,8 quit rates in those not receiving any calls were similar to the control group, suggesting that they did not differ in their capacity to quit, and that therefore the real effect of counselling was underestimated by including participants who did not receive any intervention.

Identifying the optimum number of calls and the number of attempts to complete calls for a cost effective service remains a challenge. Responding to client need is likely to be important, but proactive calls may help people who would not initiate further contact. Zhu and colleagues elegantly demonstrated that it was possible to enhance quit rates through proactive calls to smokers who had been invited to make further contact but had not done so.15 The counselling protocols showing clearest effects include at least one pre‐counselling session, and further calls scheduled close to the quit date, but with flexible schedules. Although the California protocol showed a single call to have a measurable benefit, additional calls further increased rates. The meta‐analysis in the Cochrane review suggested that a minimum of three calls was needed for an effect but this included studies in a range of settings where some counselling calls were to unmotivated smokers, or to smokers who had already been supported by face to face intervention and pharmacotherapy. There is almost no evidence about the best type of counselling when contact time and frequency are controlled. The California single call protocol focuses on promoting motivation to change, and preparing for combating urges to smoke.14 The number of calls may be more important than their length.12

Some studies tried to assess whether the intervention affected the number of quit attempts or their likelihood of success. We did not formally evaluate these intermediate outcomes. Even in these populations of help‐seeking smokers, on average only a half to two thirds recorded quit attempts, and the effect of the intervention on this intermediate outcome may not be large. Zhu and colleagues noted an increase in quit attempts from 59% with self help to 67% with a single call, but no additional effect from multiple contacts.14 There was a clearer dose‐response effect on maintenance; among those who quit, sustained abstinence increased from 15% to 20% with a single session and 27% with multiple sessions. In one study, where no effect on abstinence was detected, the number of quit attempts was lower in the intervention group.9 Another outcome reported in a few studies was the median length of abstinence. While sustained cessation has to be the ultimate goal, an extended quit attempt gives some indication of an intervention effect and may increase the likelihood of future success. Zhu14 reported an increase in the median length of abstinence in those quitting for any period from 5 days with self help to 11 days with a single counselling session and 63 days with multiple sessions. Longer duration of previous abstinence increases the probability of future success in quitting.25 Based on these findings a reasonable hypothesis would be that counselling helps maintain cessation in the early stages of a quit attempt.

Quitlines have become integral parts of national and statewide anti‐tobacco media campaigns.15 A survey of 62 North American state and province quitlines in 2005 found that all but one could provide proactive multisession counselling.26 Quitlines also have a potential impact on public health beyond that of the services they provide to individuals. Their promotion reinforces the importance of quitting and the availability of help should smokers choose to use them. This review does not directly address how much quitline services increase quitting compared to an “unassisted” attempt. It is no longer regarded as appropriate to deny support to smokers seeking this form of help and therefore no recent trials have had a no treatment control group. The multicounty trial by Ossip‐Klein and colleagues provides the best evidence for the overall effect of quitline type services. In the trial a hotline which included taped messages and access to counselling increased quit rates over a manual alone.27 The quit rates among control group participants in trials considered in this review, who received the basic quitline service, compare favourably with the success rates that might be expected for motivated but unassisted quitters. Callers to a quitline are likely to be relatively highly motivated to quit and are actively seeking help, but may also have lower self efficacy.7

Increasingly, telephone based services provide access to free or low cost pharmacotherapy where this is not available through national health services. The North American quitline survey26 found that more than half the services provided free or low cost pharmacotherapy to callers meeting eligibility criteria. In the Oregon trial, randomisation to the offer of free nicotine patches increased success rates in all three counselling intensity conditions.10 Evaluations of such initiatives have been reported from New York State,28,29 Maine,30 Minnesota31 and South Dakota.32 These also report higher quit rates for smokers provided with NRT, although the non‐randomised nature of these comparisons means that they should be interpreted cautiously. The campaigns supporting these initiatives typically combine encouragement for cessation and publicity for quitline services and the incentive of free or subsidised medication. The increase in the number of calls to services during these campaigns indicates that they increase the level of quitting activity in the populations served.

The “4As” model of counselling advocated by the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCOPR) practice guidelines recommends that healthcare providers Ask their patients about smoking, Advise them to quit, Assist them in quitting and Arrange follow‐up.33 Studies suggest that the assist and arrange components are poorly delivered.34,35 Referring motivated smokers to quitline proactive counselling may increase delivery of these components, and it is important that the quitline intervention be as effective as possible. This review shows that call‐back counselling increases efficacy, but based on a limited number of trials failed to show that any particular method of counselling or adjunctive self help materials leads to higher success rates.

What this paper adds

Systematic reviews of randomised trials have shown that telephone counselling is an effective intervention for assisting smokers to quit, while self help materials also offer a small benefit.

This review singles out the evidence supporting the benefit of call‐back counselling to help smokers who are seeking support via quitlines, showing that such counselling improves quit rates.

The paper also considers the effect of different types of counselling method and adjunctive self help materials, but failed to detect a difference between the different interventions studied.

Acknowledgements

The Cochrane Tobacco Addiction group receives core funding from the UK NHS R&D programme.

Abbreviations

ACS - American Cancer Society

NRT - nicotine replacement therapy

References

- 1.Ossip‐Klein D J, McIntosh S. Quitlines in North America: evidence base and applications. Am J Med Sci 2003326201–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stead L F, Lancaster T, Perera R. Telephone counselling for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;CD002850 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Strecher V J, Marcus A, Bishop K.et al A randomized controlled trial of multiple tailored messages for smoking cessation among callers to the cancer information service. J Health Commun 200510(Suppl 1)105–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lancaster T, Stead L F. Self‐help interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;CD001118 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Higgins J P, Thompson S G, Deeks J J.et al Measuring inconsistency in meta‐analyses. BMJ 2003327557–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenland S, Robins J. Estimation of a common effect parameter from sparse follow‐up data. Biometrics 19854155–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borland R, Segan C J, Livingston P M.et al The effectiveness of callback counselling for smoking cessation: a randomized trial. Addiction 200196881–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borland R, Balmford J, Segan C.et al The effectiveness of personalized smoking cessation strategies for callers to a quitline service. Addiction 200398837–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilbert H, Sutton S. Evaluating the effectiveness of proactive telephone counselling for smoking cessation in a randomized controlled trial. Addiction 2006101590–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hollis J, McAfee T, Stark M.et al One‐year outcomes for six Oregon tobacco quitline interventions. Ann Behav Med 200529(Suppl)S056 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rabius V, McAlister A L, Geiger A.et al Telephone counseling increases cessation rates among young adult smokers. Health Psychol 200423539–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rabius V, Pike J, Hunter J.et alOptimizing telephone counseling for smoking cessation: six‐month effects of varying the number and duration of counseling sessions. Boston, MA: American Association for Cancer Research, Frontiers in Cancer Prevention Research, 12–15 Nov 2006

- 13.Smith P M, Cameron R, McDonald P W.et al Telephone counseling for population‐based smoking cessation. Am J Health Behav 200428231–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu S H, Stretch V, Balabanis M.et al Telephone counseling for smoking cessation—effects of single‐session and multiple‐session interventions. J Consult Clin Psychol 199664202–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu S H, Anderson C M, Tedeschi G J.et al Evidence of real‐world effectiveness of a telephone quitline for smokers. N Engl J Med 20023471087–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu S H, Cummins S, Anderson C.et al Telephone intervention for pregnant smokers: a randomized trial (POS1‐110). Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco 10th Annual Meeting 18–21 February, Phoenix, Arizona 2004

- 17.Orleans C T, Boyd N R, Bingler R.et al A self‐help intervention for African American smokers: tailoring cancer information service counseling for a special population. Prev Med 199827S61–S70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson B, Kinne S, Lewis F M.et al Randomized telephone smoking‐intervention trial initially directed at blue‐collar workers. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 199314105–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cummings K M, Emont S L, Jaen C.et al Format and quitting instructions as factors influencing the impact of a self‐administered quit smoking program. Health Educ Q 198815199–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis S W, Cummings K M, Rimer B K.et al The impact of tailored self‐help smoking cessation guides on young mothers. Health Educ Q 199219495–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rabius V, Pike K J, Hunter J.et al Effects of frequency and duration in telephone counselling for smoking cessation. Tob Control 200716(Suppl I)i71–i74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rigotti N A, Park E R, Regan S.et al Efficacy of telephone counseling for pregnant smokers: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 200610883–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patrick D L, Cheadle A, Thompson D C.et al The validity of self‐reported smoking: a review and meta‐analysis. Am J Public Health 1994841086–1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tomson T, Bjornstrom C, Gilljam H.et al Are non‐responders in a quitline evaluation more likely to be smokers? BMC Public Health 2005552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abrams D B, Herzog T A, Emmons K M.et al Stages of change versus addiction: a replication and extension. Nicotine Tob Res 20002223–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cummins S E, Bailey L, Campbell S.et al Tobacco cessation quitlines in North America: a descriptive study. Tob Control 200716(Suppl I)i9–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ossip Klein D J, Giovino G A, Megahed N.et al Effects of a smoker's hotline: results of a 10‐county self‐help trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 199159325–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cummings K M, Hyland A, Fix B.et al Free nicotine patch giveaway program 12‐month follow‐up of participants. Am J Prev Med 200631181–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller N, Frieden T R, Liu S Y.et al Effectiveness of a large‐scale distribution programme of free nicotine patches: a prospective evaluation. Lancet 20053651849–1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swartz S H, Cowan T M, Klayman J E.et al Use and effectiveness of tobacco telephone counseling and nicotine therapy in Maine. Am J Prev Med 200529288–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.An L C, Schillo B A, Kavanaugh A M.et al Increased reach and effectiveness of a statewide tobacco quitline after the addition of access to free nicotine replacement therapy. Tob Control 200615286–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rabius V, Villars P, Pike J.et al Participation in telephone counselling: effects of subsidizing medication: Year 2. National Conference on Tobacco or Health May 4–6, Chicago, IL 2005

- 33.Fiore M C, Bailey W C, Cohen S J.Treating tobacco use and dependence. A clinical practice guideline. AHRQ publication No. 00‐0032. Rockville, MD: US Dept of Health and Human Services, 2000

- 34.DePue J D, Goldstein M G, Schilling A.et al Dissemination of the AHCPR clinical practice guideline in community health centres. Tob Control 200211329–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.An L C, Bernhardt T S, Bluhm J.et al Treatment of tobacco use as a chronic medical condition: primary care physicians' self‐reported practice patterns. Prev Med 200438574–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]