Short abstract

The goal of a safer vaginal environment could be reached by identifying harmful vaginal practices and an effective microbicide, thereby increasing options for HIV prevention

The global burden of HIV, its increasing feminisation, and chronic difficulties with development of options for HIV prevention all argue for an intensified re‐examination of factors influencing the efficiency of heterosexual HIV transmission. This includes vaginal practices and products used by large numbers of women worldwide to tighten, dry, warm and clean their vagina. Women's efforts to change their genital environment can undermine each component of innate defences against pathogens.1 In particular, vaginal practices have been linked with loss of lactobacilli and disruption of the vaginal epithelium.2,3,4 These practices may therefore be an important mediator in acquisition of STI, including HIV, or worsen pre‐existing infections. Despite this, surprisingly little is known about the effects of specific vaginal practices on HIV transmission dynamics.

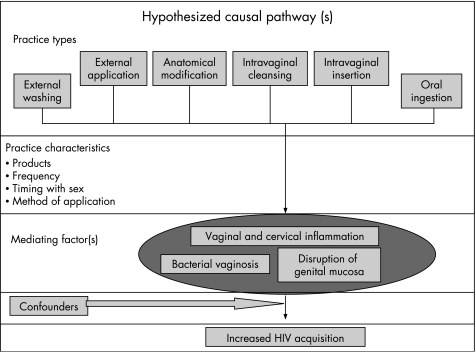

In past decades, both cross‐sectional and longitudinal studies have found an association between intravaginal cleansing and adverse reproductive outcomes, including pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancy and bacterial vaginosis (BV).1,5,6 BV could be an intermediary factor between vaginal practices and HIV infection (fig 1). Though much uncertainty remains about the pathophysiology of BV, its accompanying inflammatory milieu, characterised by pro‐inflammatory cytokines and immune cell changes, is likely to enhance HIV transmission.7 Also, immunological changes with BV can stimulate HIV expression, raising HIV levels in the genital tract virus and likely the infectivity of women.7 Acquisition of HSV‐2 may also be higher among women with BV.8

Figure 1 Hypothesised causal pathway of vaginal practices and HIV. Results of the GSVP study indicated that practice types vary and are mitigated by practice characteristics, some of which have been detailed above. Intravaginal cleansing and insertion of substances are hypothesised as being the most potentially harmful and thus the most likely to be associated with increased risk of HIV acquisition.

Evidence on whether intravaginal cleansing or insertion of substances increases risk for HIV acquisition is conflicting.1 From the nonoxynol‐9 trials, it is clear that some substances inserted into the vagina can cause epithelial disruption and are likely to facilitate HIV acquisition.4 It is possible that many commercial and traditional products have similar effects. Largely, these products remain to be identified. Limited prospective evidence is inconsistent, with two studies finding increased risk for HIV infection with the practice of using fingers to clean inside the vagina9,10 while a study in Zimbabwe and Uganda did not.11 The latter study found an increased risk for HIV acquisition in women who inserted substances to dry and tighten the vagina in preparation for sex. The authors hypothesised that these practices deserved greater research attention as they are potentially more abrasive and harmful.11 Conversely, a few studies have suggested that some intravaginal cleansing practices may have beneficial health effects.12,13

Given the above biological rationale and limitations of available evidence, further prospective evaluation of the effects of vaginal practices is needed. With cross‐sectional studies, it is difficult to distinguish the temporality of associations between HIV and specific practices. HIV infection itself can lead to increased prevalence of bacterial vaginosis or exacerbate other reproductive‐tract infections, resulting in increased vaginal discharge, which in turn motivates vaginal practices. Reverse causation may thus be a reasonable explanation for cross‐sectional associations.10

Standardised and more detailed measures of vaginal practices would also improve the quality of this research. In studies of this topic to date, categorisation of practices varies considerably, hindering cross‐study comparison and assessment of effects of individual practices. Recently, however, a vaginal practices classification and measurement framework has been developed in the WHO Multi‐Country Study on Gender, Sexuality and Vaginal Practices (GSVP). Six categories of vaginal practices have been defined (table 1). This framework emanated from extensive qualitative investigation and subsequent testing in a GSVP household survey of vaginal practices in four countries.14 In addition to using a standardised classification system, the ability of future studies to detect effects of these practices would be improved by collecting detailed data on products used, frequency of practices, timing of practices with coitus and whether these practices vary with nature of relationship and condom use. Social norms about lubrication during sex and corresponding vaginal practices have important implications for acceptability of microbicides that alter vaginal lubrication. In microbicide trials, it is important that the candidate and placebo product have similar effects on vaginal lubrication. This would avoid eliciting differential vaginal practices in each group, some of which potentially increase susceptibility to HIV. Also, women who remove vaginal lubrication or cleanse the vagina around the time of sex may unintentionally remove or dilute the microbicide product. Of perhaps greater concern, substances inserted in the vagina may chemically interact with the microbicide, with potentially harmful by‐products of such reactions. With the multitude of products used in vaginal practices, a myriad of chemical reactions between such products and microbicides is possible. As an investigator at a microbicides trial site in South Africa noted: “Cultural rituals pose challenges to microbicides clinical trials as women combine the gel with other hoped for barriers to HIV including Dettol (a disinfectant), herbs, snuff, and lemon juice”.15

Table 1 Classification of vaginal practices in the WHO Gender, Sexuality and Vaginal Practices Study.

| Practice | Definition |

|---|---|

| 1. External washing | Cleaning of the external area around the vagina and genitalia using a product or substance with or without water normally using your hand. Products used vary from soap and water, to traditional and chemical detergent‐like substances. |

| 2. External application | Placing or rubbing various substances or products to the external genitalia—that is the labia, clitoris, vulva. Included is the “steaming” or “smoking” of the vagina, by sitting above a source of heat (fire, coals, hot rocks) on which water, herbs or oils are placed to create steam or smoke. |

| 3. Anatomical modification (“cutting” and “pulling”) | Surgical procedures used for modifying the vagina, or restoration of the hymen; includes female genital circumcision, incision with insertion of substance into the lesion (scarification process, tattoos of the vulva or labia); excludes episiotomies or operations to repair a protruding uterus. In some countries, elongation or pulling of the labia minora is practised from early childhood. Sometimes, special creams or powders are applied during the pulling process. |

| 4. Intravaginal cleansing (“washing”) | Internal cleansing or washing inside the vagina includes wiping the internal genitalia with fingers and other substances (eg, cotton, cloths, paper,) for the purpose of removing fluids. It also includes douching, which is the pressurised shooting or pumping of water or solution (including douching gel) into the vagina. |

| 5. Intravaginal insertion | Pushing or placing something inside the vagina (including powders, creams, herbs, tablets, sticks, stones, leaves, cotton, paper, tampons, tissue, etc) regardless of the duration it is left inside. |

| 6. Oral ingestion | Ingesting (drinking, swallowing) of substances perceived to affect the vagina and uterus. This includes the ingestion of substances/medicines to dry or lubricate the vagina. Substances may be dissolved in water or other liquids. |

The WHO GSVP Study Group conducted extensive qualitative and prevalence research on vaginal practices in Asia and Africa. The GSVP Classifications summarised above are a result of this work. The consolidated classifications cover all practices that have been documented in the scientific literature to date on vaginal and genital practices and can be used for future studies.

An approach needs to be developed to investigating potential reactions between microbicides and products women insert vaginally, analogous to the need for investigating potential interactions between ingested or intravenous drugs. Detailed, repeated documentation of vaginal practices in microbicide trials would facilitate investigation of such effects. In sum, potential effects of vaginal practices on microbicide acceptability, efficacy and safety warrant further consideration.

Most clearly, vaginal practices and their motivations reveal much about the gendered nature of the HIV epidemic, and its underlying drivers. Particularly in resource‐constrained settings, sex may be a primary means of achieving economic security, either directly through sex work or through maintaining economically essential relations with sexual partners or husbands. Optimising sexual pleasure for men by, for example, responding to societal norms about vaginal lubrication or tightness increases a woman's ability to leverage such economic sustenance. A large variety of products are used in each vaginal practice, the sale of which often supports a sizeable informal and formal industry. Women may spend a considerable portion of their limited resources on such products, hoping to obtain a return from their investment by achieving the vaginal state men desire. In settings with unequal gender power and economic disparities, women will continue to have limited ability to negotiate protected sex and few alternatives to adopting practices which explicitly aim to satisfy men's sexual desires. Other reasons have also been reported for engaging in vaginal practices, and these vary widely in different settings, including genital hygiene, pregnancy prevention, and prevention or self‐treatment of vaginal infections.14,16 It is important to note that some evidence suggests women's vaginal practices are modifiable. Though studies have reported women are reluctant to alter their practices, in a randomised trial, women who received a counselling intervention were 1.6 times more likely to stop douching compared with women in the control group.17

Conceptually, in recent years the role of the cervix in HIV infection has gained prominence, with a diminished emphasis on the vagina as an entry site. Investigation of cervical barriers is consistent with these trends, and supported by animal studies and biological plausibility.18 However, recent data showing poor efficacy of the diaphragm in preventing HIV acquisition19 suggest the cervical‐centric approach to HIV prevention among women is now being questioned, and that vaginal health is also paramount. Documenting why women engage in vaginal practices, the mechanisms by which such practices might increase HIV acquisition and how modifiable these practices are, will be essential for the development of interventions to improve vaginal health. While efforts continue to reduce women's underlying gendered vulnerability to HIV, the goal of a safer vaginal environment could be reached by identifying harmful vaginal practices and an effective microbicide, thereby increasing options for HIV prevention.

Abbreviations

BV - bacterial vaginosis

GSVP - Gender, Sexuality and Vaginal Practices

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Myer L, Kuhn L, Stein Z A.et al Intravaginal practices, bacterial vaginosis, and women's susceptibility to HIV infection: epidemiological evidence and biological mechanisms. Lancet Infect Dis 20055786–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kilmarx P H, Limpakarnjanarat K, Supawitkul S.et al Mucosal disruption due to use of a widely‐distributed commercial vaginal product: potential to facilitate HIV transmission. AIDS 199812767–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McClelland R S, Ndinya‐Achola J O, Baeten J M. Is vaginal washing associated with increased risk of HIV‐1 acquisition? AIDS 2006201347–1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilkinson D, Ramjee G, Tholandi M.et al Nonoxynol‐9 for preventing vaginal acquisition of HIV infection by women from men. In: Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002CD003936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Hassan W M, Lavreys L, Chohan V.et al Associations between intravaginal practices and bacterial vaginosis in Kenyan female sex workers without symptoms of vaginal infections. Sex Transm Dis 200734384–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simpson T, Merchant J, Grimley D M.et al Vaginal douching among adolescent and young women: more challenges than progress. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 200417249–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.St John E, Mares D, Spear G T. Bacterial vaginosis and host immunity. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2007422–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cherpes T L, Meyn L A, Krohn M A.et al Association between acquisition of herpes simplex virus type 2 in women and bacterial vaginosis. Clin Infect Dis 200337319–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McClelland R S, Ndinya‐Achola J O, Baeten J M. Re: distinguishing the temporal association between women's intravaginal practices and risk of human immunodeficiency virus infection: a prospective study of South African women. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:474–5; author reply 475–6 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Myer L, Denny L, de Souza M.et al Distinguishing the temporal association between women's intravaginal practices and risk of human immunodeficiency virus infection: a prospective study of South African women. Am J Epidemiol 2006163552–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van de Wijgert J, Morrison C, Cornelisse P.et al Bacterial vaginosis and vaginal yeast, but not vaginal cleansing, increase HIV‐1 acquisition in African women. JAIDS. In press [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Gresenguet G, Kreiss J K, Chapko M K.et al HIV infection and vaginal douching in central Africa. AIDS 199711101–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.La Ruche G, Messou N, Ali‐Napo L.et al Vaginal douching: association with lower genital tract infections in African pregnant women. Sex Transm Dis 199926191–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.WHO Multi‐country study on gender, sexuality and vaginal pracitces. 2007. Available from: http://www.who.int/reproductive‐health/fgm/harmfulpractices.htm (accessed 24 Oct 2007)

- 15.Smith C. The closures of trials: perspectives from the ground. The Microbicide Quarterly 2007514–19 http://www.microbicide.org/microbicideinfo/reference/TMQ.Jan‐Mar2007.FINAL.pdf (accessed 30 Sep 2007). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Braunstein S, van de Wijgert J. Preferences and practices related to vaginal lubrication: implications for microbicide acceptability and clinical testing. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 200514424–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grimley D M, Oh M K, Desmond R A.et al An intervention to reduce vaginal douching among adolescent and young adult women: a randomized, controlled trial. Sex Transm Dis 200532752–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moench T R, Chipato T, Padian N S. Preventing disease by protecting the cervix: the unexplored promise of internal vaginal barrier devices. AIDS 2001151595–1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Padian N S, van der Straten A, Ramjee G.et al Diaphragm and lubricant gel for prevention of HIV acquisition in southern African women: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2007370251–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]